Fordham International Law Journal

Volume 40, Issue 2 Article 3

The Legitimacy of Informal Constitutional

Amendment and the “Reinterpretation” of

Japan’s War Powers

Craig Martin

∗

∗

Copyright

c

by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berkeley

Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj

The Legitimacy of Informal Constitutional

Amendment and the “Reinterpretation” of

Japan’s War Powers

Craig Martin

Abstract

The government of Japan has purported to reinterpret the famous war-renouncing provision of

the Constitution in a controversial process that deliberately circumvented the formal amendment

procedure. This article argues that these developments should be of great interest to constitutional

law scholars in America because they bring into sharp focus issues that remain underdeveloped

and unresolved in the debate over informal amendment. Theories on informal amendment suggest

that there are some constitutional changes that exceed the reasonable range of normal interpretive

development, but which are not implemented through formal amendment procedures. The exis-

tence, scope, and legitimacy of such informal amendments remains hotly contested.

This article focuses on the key issue of legitimacy. It uses the Japanese reinterpretation as the con-

text in which to explore the relationship among three suggested factors affecting the legitimacy of

informal amendment, namely: the public ratification of the change; the intent of the agents of the

change; and the passage of time. It also suggests a new way of conceptualizing the relationship

among authority, legitimacy, and time in thinking about informal amendments, in that the level of

constitutional authority and degree of legitimacy that may be enjoyed by contested changes will

begin to diverge with the passage of time.

The article argues that deliberate attempts to effect significant constitutional change in a manner

calculated to circumvent the formal amendment process—such as the Abe government’s reinter-

pretation effort in Japan—are prima facie unauthorized and illegitimate at the time they occur.

Moreover, only the most explicit and deliberate expressions of popular sovereignty can serve to

legitimate such changes. But while such deliberate informal change will always remain unau-

thorized, it may be legitimated with the passage of time. I argue that this legitimation may, and

should, take longer than for less contested forms of change.

KEYWORDS: Informal Amendment, Japanese Constitutional Reinterpretation

427

ARTICLE

THE LEGITIMACY OF INFORMAL

CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT

AND THE “REINTERPRETATION” OF

JAPAN’S WAR POWERS

Craig Martin

*

ABSTRACT

The government of Japan has purported to reinterpret the

famous war-renouncing provision of the Constitution in a

controversial process that deliberately circumvented the formal

amendment procedure. This article argues that these developments

should be of great interest to constitutional law scholars in America

because they bring into sharp focus issues that remain

underdeveloped and unresolved in the debate over informal

amendment. Theories on informal amendment suggest that there are

some constitutional changes that exceed the reasonable range of

* Professor of Law, Washburn School of Law, B.A. (R.M.C.), J.D. (Univ. of Toronto),

LL.M. (Osaka Univ.), S.J.D. (Univ. of Pennsylvania). This project was presented, at various

stages of its development, at conferences convened by the Law and Society Association in

Seattle, the Asian Law and Society Association in Tokyo, the American Association of Law

Schools in New York City, the Asser Institute in The Hague, Ritsumeikan University in

Kyoto, and the University of New South Wales, Sydney—I am grateful to the organizers of the

conferences and the specific panels for the opportunities to present, and I am thankful for the

many helpful suggestions and comments from many other people that I received both at the

conferences and on various drafts and in discussions about the argument at various stages

along the way. In particular I would like to thank Bruce Ackerman, Koji Aikyo, Richard

Albert, Juliano Benvindo, Carlos Bernal, Lois Chiang, Benson Cowan, Mahesh Daas, Rosalind

Dixon, Eric Feldman, Tom Ginsburg, Yasuo Hasebe, John Haley, John Head, Virginia Harper

Ho, Ali Khan, Akihiko Kimijima, Junko Kotani, Rob Leflar, Mark Levin, Sanford Levinson,

Setsuo Miyazawa, Hitoshi Nasu, Luke Nottage, Susannah Pollvogt, Larry Repeta, Bill Rich,

David Rubenstein, Eiji Sasada, Takeshi Shirōzu, Freddy Sourgens, Bryce Wakefield, and

Hajime Yamamoto. I am also grateful for research assistance from Zacharia Zallo. I of course

remain responsible for any errors. (On a point of transliteration, Romanized Japanese names

throughout the article are rendered surname last, rather than the Japanese custom of surnames

first).

428 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

normal interpretive development, but which are not implemented

through formal amendment procedures. The existence, scope, and

legitimacy of such informal amendments remains hotly contested.

This article focuses on the key issue of legitimacy. It uses the

Japanese reinterpretation as the context in which to explore the

relationship among three suggested factors affecting the legitimacy of

informal amendment, namely: the public ratification of the change;

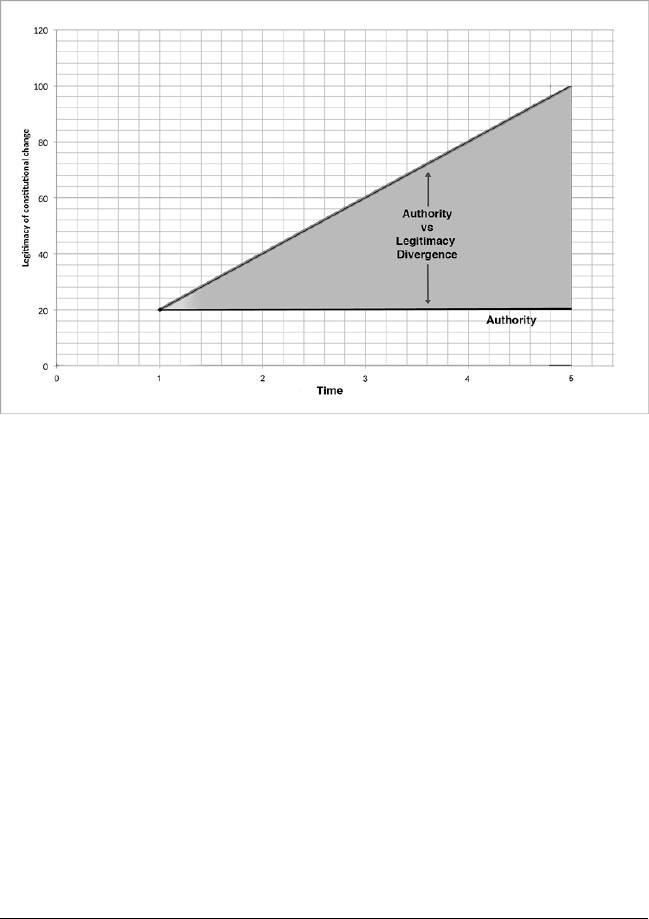

the intent of the agents of the change; and the passage of time. It also

suggests a new way of conceptualizing the relationship among

authority, legitimacy, and time in thinking about informal

amendments, in that the level of constitutional authority and degree of

legitimacy that may be enjoyed by contested changes will begin to

diverge with the passage of time.

The article argues that deliberate attempts to effect significant

constitutional change in a manner calculated to circumvent the

formal amendment process—such as the Abe government’s

reinterpretation effort in Japan—are prima facie unauthorized and

illegitimate at the time they occur. Moreover, only the most explicit

and deliberate expressions of popular sovereignty can serve to

legitimate such changes. But while such deliberate informal change

will always remain unauthorized, it may be legitimated with the

passage of time. I argue that this legitimation may, and should, take

longer than for less contested forms of change.

ABSTRACT ....................................................................................... 427

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 429

I. INFORMAL AMENDMENT ........................................................ 437

A. Preliminaries - Assumptions and Premises ........................ 437

B. Theories of Informal Amendment and the Issue of

Legitimacy ......................................................................... 443

C. Critics and the Contours of Legitimacy .............................. 458

II. THE JAPANESE CONSTITUTIONAL

REINTERPRETATION .......................................................... 462

A. The Constitution of Japan and Article 9 ............................. 462

B. The Government Interpretation and Operation of

Article 9 ............................................................................. 467

C. The Process of Reinterpretation .......................................... 475

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 429

III. THE REINTERPRETATION, INFORMAL AMENDMENT,

AND LEGITIMACY............................................................... 489

A. The Reinterpretation as Normal Interpretive Move ............ 490

B. The Reinterpretation as Informal Amendment ................... 502

C. Clarifying the Contours of Legitimacy ............................... 506

CONCLUSION .................................................................................. 520

INTRODUCTION

There is a vibrant debate in American constitutional law

scholarship regarding the existence, nature, and legitimacy of so-

called informal amendments.

1

The definition of the concept of

“informal amendment” is itself an important subject in the debate, but

we may start with the idea that the term refers to a form of significant

change to the understanding and operation of a constitutional

provision that is neither a formal amendment nor a normal

1. See, e.g., BRUCE ACKERMAN, WE THE PEOPLE, VOL. 2: TRANSFORMATIONS (1998);

Sanford Levinson, How Many Times Has the United States Constitution Been Amended? (A) >

26; (B) 26; (C) 27; (D) > 27: Accounting for Constitutional Change [hereinafter Levinson,

How Many Times Has the United States Constitutions Been Amended?], in R

ESPONDING TO

IMPERFECTION: THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT 13 (Sanford

Levinson ed., 1995) [hereinafter R

ESPONDING TO IMPERFECTION]; Akhil Reed Amar, Popular

Sovereignty and Constitutional Amendment, in R

ESPONDING TO IMPERFECTION 89; Stephen

Griffin, Constitutionalism in the United States: From Theory to Politics, in R

ESPONDING TO

IMPERFECTION 37; Donald S. Lutz, Toward a Theory of Constitutional Amendment, in

R

ESPONDING TO IMPERFECTION 237 [hereinafter Lutz, Toward a Theory - Responding to

Imperfection]; David R. Dow, The Plain Meaning of Article V, in R

ESPONDING TO

IMPERFECTION 117; Stephen Holmes & Cass R. Sunstein, The Politics of Constitutional

Revision in Eastern Europe, in R

ESPONDING TO IMPERFECTION 275; Jack M. Balkin &

Sanford Levinson, Understanding the Constitutional Revolution, 87 V

A. L. REV. 1045 (2001);

Z

ACHARY ELKINS, TOM GINSBURG & JAMES MELTON, THE ENDURANCE OF NATIONAL

CONSTITUTIONS (2009); Aziz Z. Huq, The Function of Article V, 162 U. PA. L. REV. 1165

(2014); Ernest A. Young, The Constitution Outside the Constitution, 117 Y

ALE L. J. 408

(2007); Brannon P. Denning, Means to Amend: Theories of Constitutional Change, 65 T

ENN.

L. REV. 155 (1997); Brannon P. Denning & John R. Vile, The Relevance of Constitutional

Amendments: A Response to Strauss, 77 Tul. L. Rev. 247 (2002); Rosalind Dixon, Updating

Constitutional Rules, 8 S

UP. CT. REV. 319 (2009); David A. Strauss, The Irrelevance of

Constitutional Amendments, 114 H

ARV. L. REV. 1457 (2001); WILLIAM N. ESKRIDGE JR. &

JOHN FEREJOHN, A REPUBLIC OF STATUTES: THE NEW AMERICAN CONSTITUTION (2010);

Randy E. Barnett, We the People: Each and Every One, 123 Y

ALE L. J. 2576 (2014); Richard

Albert, Constitutional Disuse or Desuetude: The Case of Article V, 94 B.U.

L. REV. 1029,

1062 (2014); Heather K. Gerken, The Hydraulics of Constitutional Reform: A Skeptical

Response to Our Democratic Constitution, 55 D

RAKE L. REV. 925 (2007).

430 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

interpretive development. Formal amendments are, of course, those

changes to the constitution initiated and approved in accordance with

the established constitutional amendment procedure. Interpretive

developments are the incremental changes in meaning that are

typically the result of judicial decision-making. Informal amendment

refers to changes in meaning or understanding that are arguably so

dramatic and relatively sudden that they are impossible to reconcile

with the text, purpose, and historical operation of the provision in

question (according to most accepted theories of constitutional

interpretation), and therefore will not be accepted by most jurists as a

“normal” interpretive move.

2

Thus, the argument goes, such a change

is better characterized as being a form of amendment to the

constitutional system rather than an interpretive development, even

though it is not a formal amendment and it creates no change to the

underlying constitutional text.

3

This standard formulation of informal amendment obviously

implicates much broader debates in constitutional law. These include,

particularly, the competing theories of valid constitutional

interpretation and related arguments over the question of whether,

how, or to what extent the constitution can be said to legitimately

change through interpretation by the judiciary or by other branches of

government.

4

There are thus differences among the theories of

informal amendment which mirror differences among theories of

constitutional interpretation. But the theories on informal amendment

largely arise in response to the felt need to explain, and for some

theorists to legitimate, the relatively dramatic changes to the

American constitutional system that were not promulgated by way of

a formal amendment in accordance with the Article V process, and

which cannot be reconciled with most scholars’ notions of legitimate

interpretive change.

5

While the different theories of informal

amendment share this common purpose, supporters of each differ in

their explanations for the modalities and process of change. They

differ both descriptively in terms of what changes qualify as an

2. Levinson, How Many Times Has the United States Constitution Been Amended?,

supra note 1, at 14-15.

3. Id.

4. See infra Section I.A.

5. Sanford Levinson, Imperfection and Amendability, in R

ESPONDING TO

IMPERFECTION, supra note 1, at 7.

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 431

informal amendment and how they are said to come about, and

normatively in terms of whether or how such change might be

considered beneficial or legitimate.

6

And of course, there are critics

who reject the very notion of informal amendments on both

descriptive and normative grounds.

7

Even if we take these theories of informal amendment seriously

and on their own terms, however, we are nonetheless left with

profoundly difficult questions, some of which remain somewhat

under-theorized and unresolved. These questions are both descriptive

and normative in form, and while some of them may be impossible to

resolve without first resolving the broader debates about

interpretation,

8

some of them may be less intractable. In particular,

one question that seems insufficiently explored is whether such

informal amendments are legitimate, and more importantly, how we

are to determine if any given change is indeed legitimate.

This article explores the question of the legitimacy of informal

amendments. It does so by examining the recent efforts to

“reinterpret” the famous war-renouncing provision of the Japanese

constitution. This attempt to significantly change the meaning of the

provision was undertaken by the Japanese cabinet in a very deliberate

and calculated manner to circumvent the formal amendment

procedure, and even to minimize legislative involvement and public

participation in the process. The legitimacy of the attempted

reinterpretation is the subject of considerable controversy within

Japan, though the change may be in the process of becoming a fait

accompli. In exploring this reinterpretation effort through the lens of

informal amendment theory, the article identifies and analyzes three

features of informal amendment as important factors for determining

the legitimacy of any given change. In doing so, the article re-

conceptualizes the contours of informal constitutional change,

exploring not only the relationship among these three factors of

6. See infra Section I.B.

7. See infra Section I.B.

8. The exact criteria for identifying informal amendments, for instance, will obviously

depend in large measure upon what theory of constitutional interpretation one embraces, and

so it would be difficult to answer questions about the exact border between interpretive change

and informal amendment with any degree of certainty or precision, until debates over

interpretation are settled. That is not likely to happen any time soon, and yet these remain

important questions if we are to consider theories about informal amendment as useful in

identifying different forms of constitutional change.

432 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

legitimacy, but also the distinction and relationship between the

concepts of legitimacy and authority in the context of constitutional

change.

The first of the three factors that determine legitimacy, is the

extent to which decision-makers within government are deliberately

trying to bring about the specific change, in an intentional

circumvention of the formal amendment procedure. The second is the

extent to which there are explicit expressions of public will in favor of

the change. And the third is the passage of time. With respect to the

first factor, what I will call “deliberate agency,” the question is

whether the claims to legitimacy of any particular informal

amendment are (or ought to be) affected by the extent to which it is

brought about by political actors who understand that the change

constitutes an amendment, but nonetheless deliberately circumvent

the formal amendment process in executing the change. This is in

contrast to changes that might arise more organically through the

complex dynamics of the law and policy making process among

agencies and between the political branches of government, and are

thus the product of the unintentional and unpredictable operations of a

system.

9

Put simply, does informal amendment theory accept as

legitimate the deliberate circumventions of the formal amendment

procedure? I will argue below that it should not.

The second factor is that of popular will. To the extent that

informal amendment theory has addressed the issue of legitimacy, the

debate has tended to focus on the role of popular sovereignty and

expressions of public will. Bruce Ackerman, one of the driving forces

of informal amendment theory,

10

as well as Akhil Amar,

11

make

explicit claims that informal amendments ratified or initiated by the

people are legitimate precisely because they reflect an expression of

popular sovereignty.

12

These claims are contested.

13

But I will explore

them here within the context of the Japanese developments, and

examine the relationship between popular sovereignty and the

9. On system effects in the constitutional context, see Adrian Vermeule, Forward:

System Effects and the Constitution, 123 H

ARV L. REV. 4 (2009).

10. See

ACKERMAN, supra note 1.

11. See Amar, supra note 1.

12. See infra notes 79-86 and 108, and accompanying text.

13. See, e.g., Dow, supra note 1. For details see infra notes 99-101 and accompanying

text.

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 433

separate factors of deliberate agency and time as a basis for

legitimacy. I will argue that while Ackerman’s theory cannot be

applied to legitimate the Japanese experience, the reinterpretation in

Japan reveals insights about the value of Ackerman’s theory that have

been missed or under-appreciated in some of the critiques of his

model. Specifically, while the critics may be correct that explicit

expression of popular consent may not be a sufficient condition for

the legitimation of deliberate informal amendment, they perhaps miss

the point that such expressions of popular will ought to be a necessary

condition.

14

The third factor is time. By the passage of time, I mean to focus

on the fact that deeply contested constitutional changes, including

informal amendments widely considered to be entirely unauthorized

and illegitimate at the time they are undertaken, will gradually

become legitimate over time, so long as the change can be sustained

and entrenched.

15

Thus, for instance, if some of the moves during the

New Deal were illegitimate at the time (about which there is of course

continued and vigorous debate), most of us will agree that with the

passage of time they became legitimate in practical terms.

16

This is

due to the layers of law, policy, and precedent that are constructed

upon the foundation of these changes. But there remains the question

of whether such ex post recognition or acceptance could ever ground

an argument for legitimizing ex ante the kinds of political or

institutional developments that we are here calling informal

amendment. In other words, can one look to examples such as the

New Deal changes as precedents for purposes of legitimizing

informal constitutional changes before or at the time they are

effected? I will argue that such time-legitimated changes cannot serve

as precedents for the ex-ante legitimation of informal amendments,

particularly when such changes are the result of deliberate

circumvention of the amendment process rather than the unconscious

14. See infra Section III.C.

15. Walter Murphy has turned his attention to the issue of time in the context of

informal amendment, but does not focus on this particular aspect. See Walter F. Murphy,

Merlin’s Memory: The Past and Future Imperfect of the Once and Future Polity, in

R

ESPONDING TO IMPERFECTION, supra note 1, at 163

16. Levinson points out that even Justice Bork implicitly conceded this point even as he

argued against the validity of informal amendments. See Levinson, How Many Times Has the

United States Constitution Been Amended?, supra note 1, at 35 (citing R

OBERT BORK, THE

TEMPTING OF AMERICA: THE POLITICAL SEDUCTION OF THE LAW 215 (1990)).

434 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

product of dynamic systems. Be that as it may, however, the

recognition of the effects of time should also serve to galvanize into

action those who believe a change is illegitimate, for time will be of

the essence.

17

What is more, in thinking about the relationship between time

and legitimacy, we begin to understand that the passage of time is one

factor that separates authority and legitimacy. That is to say, the

legitimacy of any change is derived from and is almost synonymous

with the constitutional authority for such change, at the time it is

undertaken. But over time an unauthorized change may gain de facto

legitimacy, while its lack of theoretical authority remains constant.

18

This leads to a possible reformulation of the relationship among

authority, legitimacy, and time, which in turn leads to insights into the

role that deliberate agency and popular will might play in determining

legitimacy. I will suggest that the three factors—deliberate agency,

popular will, and time—need to be understood separately as distinct

criteria for legitimacy, but also collectively, in terms of how they

relate to one another in the determination of legitimacy. And in

particular, I will argue that this insight into the relationship between

time and legitimacy grounds both a descriptive hypothesis and a

normative argument that deliberate informal amendments such as that

undertaken in Japan, in the absence of any ratification by explicit

popular consent, will and ought to take longer to be legitimated than

other forms of change.

19

The developments in Japan may be viewed as a case study of

informal amendment that is unfolding in real-time. In order to

properly use this case study, the article takes some time to explain the

Japanese events in some detail.

20

The salient points, however, are that

the Japanese government under Prime Minister Shinzō Abe has been

engaging in an effort to relax the constitutional constraints on the use

of military force.

21

Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution famously

renounces war as a sovereign right of the nation and prohibits the

17. See infra Section III.C.

18. It has been pointed out that one could reverse this relationship, depending on how

one conceives of legitimacy and authority—that is to say that a change may become

authoritative in practical terms over time, while we might continue to insist that it lacked, and

continues to lack, formal legitimacy. Thanks to my colleague Freddy Sourgens for this point.

19. See infra Section III.C.

20. See infra Part II.

21. See infra Section II.C.

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 435

threat or use of force.

22

The government quite deliberately sought to

implement what it acknowledged to be a significant change to the

understanding of Article 9, in a manner that was calculated to

circumvent the formal amendment procedure.

23

The government

implemented the reinterpretation through the issuance of a Cabinet

Decision,

24

based in part on the recommendations of an ad hoc extra-

constitutional body of so-called experts, and with little public input or

legislative debate. It then committed the nation to the reinterpretation

through international agreements with the United States. Only after all

of this did the government submit legislation to the Diet (the

legislature) that would revise national security laws in conformity

with the reinterpretation—but even this did not require a debate on

the substance of the reinterpretation itself.

Meanwhile, the government interfered with the independence of

government agencies that might oppose the reinterpretation, and tried

to suppress media criticism of the moves.

25

The entire effort gave rise

to ferocious debate and protest within Japan, with tens of thousands of

people protesting in the streets of Tokyo and other major cities. The

majority of scholarly and professional opinion held the

reinterpretation, and the subsequently revised national security laws,

to be illegitimate and unconstitutional.

26

Yet, despite all of this, the

governing party was nonetheless hugely successful in elections for the

Upper Chamber of the Diet in July of 2016. The inevitable

constitutional challenges to the national security legislation have not

yet resulted in any judicial decisions—but they will surely reach the

Supreme Court in due course. It is unclear how the Court, which has

been traditionally timid and deferential on constitutional issues, will

deal with the challenges. The government’s effort is thus still very

much a work in process and the jury is still out on whether the

22. NIHONKOKU KENPŌ [KENPŌ] [CONSTITUTION], art. 9, para. 1 (Japan). For the full

text of the provision, see infra note 127 and accompanying text.

23. See infra Section II.C.

24. C

ABINET DECISION ON DEVELOPMENT OF SEAMLESS SECURITY LEGISLATION TO

ENSURE JAPAN’S SURVIVAL AND PROTECT ITS PEOPLE (provisional English translation) (July

1, 2014), available at http://www.cas.go.jp/jp/gaiyou/jimu/pdf/anpohosei_eng.pdf (last visited

Aug., 2016) [hereinafter C

ABINET DECISION]. The original Japanese language version is

available at: http://www.cas.go.jp/jp/gaiyou/jimu/pdf/anpohosei.pdf.

25. See infra Section II.C.

26. See infra notes 209-14 and accompanying text.

436 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

reinterpretation will end up being entrenched, becoming a

legitimatized change to the Constitution with the passage of time.

These developments provide the constitutional law academy

with a striking and potentially important example of deliberate efforts

to engage in constitutional change in circumvention of the formal

amendment procedure. When examined through the lens of informal

amendment theory, the over-arching question presented by the

Japanese reinterpretation effort is whether it can be classified, either

now or in the future, as nothing more than a legitimate interpretive

development, as an informal amendment, or as something else again.

I argue below that the reinterpretation of Article 9 cannot be accepted

as a normal and legitimate interpretive move—that it was arrived at

through an invalid process, and is in any event substantively outside

of the reasonable range of possible meanings of the provision when

interpreted in accordance with most widely accepted theories of

constitutional interpretation.

Moving from this premise I examine the reinterpretation from

the perspective of informal amendment theory. Specifically, I focus

on the role of deliberate agency, popular will, and passage of time as

determinants of legitimacy. The reinterpretation is one of the clearest

examples of a government trying to implement significant

constitutional change through methods that reflect a deliberate and

self-conscious effort to circumvent the formal amendment procedure,

and so brings the issue of deliberate agency into stark relief. Japan

also provides us with an excellent example of the ambiguity and

complexity involved in trying to attribute constitutional meaning to

election results following putative informal amendments. It provides

support for some of the theoretical criticism of popular sovereignty

arguments for legitimacy, but also reveals some of the overlooked

value in Ackerman’s theories about the relationship between popular

sovereignty and the legitimacy of informal amendment.

27

In sum, I

conclude that the reinterpretation is not legitimate, and that it helps

illustrates how and why deliberate agency and public will should be

considered in assessing the legitimacy of informal amendments, and

why time is of the essence in opposing them.

The article proceeds in three parts. Part I provides an

examination of informal amendment theories, focusing on how they

27. See infra Section III.C.

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 437

treat the question of legitimacy, and in particular how or to what

extent the different theories consider deliberate agency, popular will,

and the passage of time as factors contributing to legitimacy. Part II

provides an explanation of Article 9 of the Constitution of Japan and

the efforts of the Japanese government to reinterpret the provision.

Part III examines first whether the reinterpretation can be

characterized as a normal interpretive development, and then analyzes

the reinterpretation as an informal amendment, assessing what it tells

us about the factors of deliberate agency, popular will, and time as

determinants of legitimacy. In addition to evaluating the legitimacy of

the reinterpretation, it examines how we might re-conceptualize the

contours of informal amendment and our understanding of the

determinants of legitimacy. The article has two audiences in mind: the

first being American constitutional law scholars, for whom it seeks to

clarify certain aspects of informal amendment theory, and explain the

significance of the Japanese example; and the second being Japanese

constitutional law scholars, for whom it seeks to provide insights and

warnings regarding what American informal amendment theory may

say about the legitimacy of the reinterpretation of Article 9.

I. INFORMAL AMENDMENT

This Part explores some of the defining features of informal

amendment theory, and in particular those differences among the

various explanations of informal amendment that are most salient to

the issues of deliberate agency, popular will, and time as factors of

legitimacy. But before launching into that examination, it may be

prudent to clarify some of the underlying assumptions and premises

of this study. As mentioned earlier, because the debate over informal

amendment implicates much broader and more fundamental

disagreements in constitutional law, it is important to be quite clear, if

necessarily brief, about some of the principles and theoretical

positions that form part of the foundation for my analysis.

A. Preliminaries - Assumptions and Premises

First, a constitution, as the legal framework that defines the

distribution of power and authority within the State, has the dual

purpose of both facilitating and making the exercise of political power

438 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

possible, and constraining government power in meaningful ways.

28

This idea that constitutions constrain the exercise of government

power of course reflects the basic democratic rule of law principle

that the law applies equally to all, including all branches and agencies

of government, and is also a necessary condition for the concept of

constitutionally protected individual rights.

29

But the idea is also the

foundation of the notion that constitutions, or at least some

constitutional provisions, serve as pre-commitment devices—that is,

mechanisms designed by the drafters to bind future generations of

government to specified values, principles, and conduct, particularly

in circumstances of crisis or passion in which future governments

might be expected to depart from the original vision of the

constitution.

30

This all may seem rather obvious, yet it bears repeating

here, because Prime Minister Shinzō Abe famously remarked in the

context of the reinterpretation debate that the idea that constitutions

are designed to limit state power was an anachronistic view.

31

Finally,

it should be noted that while binding on future generations of

government, liberal democratic constitutions derive some of their

legitimacy from the very fact that they can be changed—that they, in

effect, delegate some of the drafting authority to future generations

through the mechanism of an amending formula.

32

At the same time,

the amendment procedure is typically difficult, and must be more

difficult than the mere passage of laws if the constitution is to fulfill

its entrenchment function in any meaningful way.

33

28. Jack M. Balkin, Constitutional Interpretation and Change in the United States: The

Official and the Unofficial, 14 J

US POLITICUM 1, 2 (2015) (constitutions are “frameworks for

making politics possible”).

29. We will return to this relationship between constraints and rights, but on this see,

e.g., Dow, supra note 1, at 136-37.

30. On constitutions as pre-commitment devices generally, see J

ON ELSTER, ULYSSES

AND THE

SIRENS: STUDIES IN RATIONALITY AND IRRATIONALITY (1979); see also CASS

SUNSTEIN, DESIGNING DEMOCRACY: WHAT CONSTITUTIONS DO 96-101 (2001); Stephen

Holmes, Precommitment and the Paradox of Democracy, in C

ONSTITUTIONALISM AND

DEMOCRACY 195 (Jon Elster & Rune Slagstad eds., 1988).

31. Lawyer Group Charges Abe with Constitutional Ignorance, J

APAN TIMES (Feb. 14,

2014), http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/02/14/national/lawyer-group-charges-abe-with-

constitutional-ignorance/ (“the idea that the Constitution is intended to limit the power of the

state is an old-fashioned view held at the time when a monarch was governing the country with

absolute power.”).

32. Holmes & Sunstein, supra note 1, at 275-76.

33. Dow, supra note 1, at 136-37.

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 439

The concept of “constitution” here is more than the mere text or

documents comprising the written constitution. In the United States

(and many other constitutional systems) the actual document looms

large in our thinking about the Constitution, and there are times when

a focus on the text is necessary;

34

however, it is important to

recognize that the Constitution in broader terms is best thought of as a

system. That is to say, that in addition to any document that comprises

the text of a constitution, there is a broader system of principles,

jurisprudence, conventions, understandings, and quasi-constitutional

statutes that together operate to form what may be called the

“constitution-in-practice.”

35

And like most systems, it is assumed here

that most democratic constitutional systems are dynamic and

constantly changing. To say that they are always changing is to

recognize the widely accepted idea that there is legitimate incremental

change in constitutional meaning through judicial interpretation

(recognizing, of course, that this is not accepted by certain strands of

originalist theory).

36

This is so in part because many constitutional

provisions are cast in general language, stipulating standards and

principles rather than clear rules, and thus require judgment in

interpretation, construction, and the development of doctrine and tests

for their future application.

37

While there are differing theories of precisely how constitutional

provisions ought to be interpreted, most accept that there is some

reasonable range of possible meaning for any given provision, and the

range of possible meaning under each of those theories overlap to a

considerable degree.

38

With the passage of time, shifting ideas, and

34. See, e.g., GINSBURG ET AL., supra note 1, at 6 (emphasizing that for their study “we

do indeed mean the text, specifically the written constitutional charter of independent

countries.”).

35. Balkin, supra note 28, at 3; Griffin, supra note 1, at 38, 44; see also D

AVID A.

STRAUSS, THE LIVING CONSTITUTION (2010); Jack M. Balkin, The Roots of the Living

Constitution, 92 B.U.

L. REV. 1129 (2012).

36. For an overview of originalist theories, see, e.g., T

HE CHALLENGE OF

ORIGINALISM: THEORIES OF CONSTITUTIONAL INTERPRETATION (GRANT HUSCROFT &

BRADLEY W. MILLER EDS., 2011). Not all strands of originalist theory would disagree. See,

e.g., Balkin, supra note 28, at 3-4, 21-23.

37. Balkin, supra note 28, at 2, 6-7.

38. Levinson, How Many Times Has the United States Constitution Been Amended?,

supra note 1, at 17-18; Lutz, Toward a Theory - Responding to Imperfection, supra note 1, at

241. For a short overview of theories of constitutional interpretation, see J

OHN H. GARVEY ET

AL

., MODERN CONSTITUTIONAL THEORY: A READER 91-218 (5th ed. 2004); see also

Laurence H. Tribe, Contrasting Constitutional Visions: Of Real and Unreal Differences, 22

440 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

evolving political and social conditions, the interpretation of those

constitutional principles, standards, and constructed doctrines will

evolve incrementally in the jurisprudence of the judiciary. Moreover,

while the ultimate interpretive move is typically undertaken by the

judiciary (at least in those constitutional systems in which there is a

strong convention of constitutional judicial review), this process of

constitutional change is often driven by the other branches of

government, and indeed by political parties and civil society acting

through and on the political branches of government. In most

instances, however, the judiciary is called upon in the final stage to

either ratify or reject the resulting political action, policy, or law.

39

In

many ways the starting point for any discussion of informal

amendment is the idea that this form of interpretive development,

occurring within what most would accept as the range of reasonable

interpretation for any given provision, is valid and legitimate (with

the noted exception of certain strands of originalism).

It is widely accepted that constitutions legitimately change

through this process of interpretive development, but there is far less

agreement on where the outer limits are for the range of reasonable

and legitimate meanings of specific provisions in particular

circumstances. Similarly, there is less agreement over what it means

when any particular interpretation is widely perceived to have

exceeded the limits of legitimate interpretive moves. That some

change does exceed this limit is of course the very basis for the theory

of informal amendment. But it should be made clear that many

scholars and jurists do not accept the idea that putative interpretive

moves, or other forms of constitutional change that exceed the

legitimate bounds of this valid process of interpretive development,

can be properly characterized and normalized as so-called informal

amendments.

40

Many reject the informal amendment claims on descriptive

grounds, simply accepting as legitimate interpretation that which

HARV. C.R.-C.L. L. REV. 95 (1987) (arguing that the differences among theories of

constitutional interpretation are not as great as commonly thought).

39. Balkin, supra note 28, at 7-10. There are, of course, challenges to the idea that the

judiciary has the primary role in constitutional interpretation. See, e.g., M

ARK TUSHNET,

TAKING THE CONSTITUTION AWAY FROM THE COURTS (1999); Larry Alexander Frederick

Schauer, On Extrajudicial Constitutional Interpretation, 110 H

ARV. L. REV. 1359 (1997).

40. See, e.g., Dow, supra note 1; Barnett, supra note 1.

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 441

informal amendment proponents claim to be extraordinary change

requiring special explanation.

41

But more importantly, perhaps, many

also reject the claims on normative grounds, even as some of these

critics concede that as a descriptive matter significant and

unauthorized changes—changes that do exceed the reasonable limits

of interpretation—apparently do occur from time to time. I will

explore their ideas further below. For some in this camp, however, the

idea of informal amendment is bitterly acknowledged as being real,

but at the same time the source of a paradox that cripples the very

idea of rule of law constitutionalism.

42

For others it is a theory to be

denied, denounced, and rejected precisely because its acceptance

would constitute a threat to rule of law constitutionalism.

43

While I am sympathetic to several of the normative arguments of

the critics of informal amendment theory, in this article I assume that

the phenomenon it seeks to explain is real, and that moreover it is an

important issue that requires explanation. Certainly in the American

context (but not only in the American context) there are changes that

are difficult to account for by reference to “normal” interpretive

developments. Moreover, efforts to reconcile such changes with our

accepted theories of constitutional interpretation can end up

weakening the coherence and integrity of those theories, and

undermining the normative power of the Constitution. Thus, the

article takes the theory of informal amendment on its own terms, and

tries to explore the different approaches, explanations, and some

unresolved questions about the process, with a view to advancing our

understanding of the theory. At the same time, it is worth noting that

the informal amendment theories under discussion here, as different

as they are in their detail, all share the idea that a constitution itself, as

a body of law, provides the framework within which one must

consider the idea of constitutional change. This is in contrast to some

scholars who argue that one can validly and legitimately think about

bringing about constitutional change through the radical change to the

socio-political presuppositions from which a constitution initially

developed, in total disregard of what the constitutional system itself

41. See, e.g., Sunstein, supra note 1, at 279, n.9.

42. See, e.g., Griffin, supra note 1.

43. See, e.g., Dow, supra note 1.

442 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

provides regarding amendment.

44

I am not here engaging these more

radical political theories of constitutional change.

Finally, some preliminary words are perhaps necessary on the

question of whether it is proper or feasible to apply this American

theory of constitutional law to a Japanese situation; and, similarly,

whether it is possible to draw any meaningful lessons for the

American theory from a Japanese case study. It is of course widely

accepted that the comparative analysis of constitutional law is both

valid and fruitful, and there is a growing literature on the topic.

45

With

respect to theories of informal amendment more specifically, most

writing in the American academy has been focused on the American

constitutional experience. Indeed some aspects of American

explanations relate to attributes that are unique to the American

system and its history. But the phenomenon it explores is certainly not

limited to the United States. Questions as to how far the range of

reasonable and legitimate interpretive development extend, and what

branches of government can be involved, are not unique. The

principles involved are common to most liberal constitutional

democracies.

46

What is more, there are have been other comparative

44. Frederick Schauer, Amending the Presuppositions of a Constitution, in

R

ESPONDING TO IMPERFECTION, supra note 1, at 145.

45. See, e.g., C

OMPARATIVE CONSTITUTIONAL DESIGN: COMPARATIVE

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AND POLICY (Tom Ginsburg ed., 2014); MARK TUSHNET, ADVANCED

INTRODUCTION TO COMPARATIVE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW (2006); COMPARATIVE

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW (Tom Ginsburg & Rosalind Dixon eds., 2013); Mark Tushnet, The

Possibilities of Comparative Constitutional Law, 108 Y

ALE L.J. 1225 (1999).

46. There are analogous European theories of constitutional mutation that have much

in common with informal amendment theory. In particular see the theories of informal

constitutional change developed by Georg Jellinek, discussed in Carlos Bernal, Forward-

Informal Constitutional Change: A Critical Introduction and Appraisal, 62 A

M. J. COMP. L.

493, 505 n.40 (2014). Similarly, in several of the Commonwealth countries there are forms of

constitutional change that might fall within the range of what is here being called informal

amendment, such as the creation of “constitutional conventions,” some of which are

recognized as legitimate and for which criteria are clearly established. See S

IR W. IVOR

JENNINGS, THE LAW AND THE CONSTITUTION 136 (5th ed., 1959) (articulating the seminal test

for the establishment of a convention). See Ryan Patrick Alford, War With ISIL: Should

Parliament Decide? 20 R

EV. CONST. STUD. 118, 123-28 (2015) (reviewing the modern law on

conventions, and describing the establishment of a new convention on parliamentary approval

of the use of force in the United Kingdom, 2003-14). It might be argued that it is a misnomer

to classify such a convention an informal amendment, since the United Kingdom does not

have a written constitution, and so no formal constitutional amendment procedure, but the fact

that the concept has been adopted in commonwealth countries that do have written

constitutions, with formal amendment procedures, arguably makes the process relevant to

informal amendment theory. But see Richard Albert, Constitutional Amendment by Stealth, 60

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 443

studies that have examined putative examples of informal amendment

in other countries through the lens of American informal amendment

theory.

47

Thus, on both questions of whether the theory is applicable

in other contexts, and whether a Japanese case study can provide

insights, I would argue that the theory is entirely susceptible to

analysis from a comparative law perspective—and for reasons I will

explain in more detail below, American scholars and jurists can

indeed learn from the Japanese experience. Nor is it inappropriate or

inapt to suggest that the theory is relevant to Japan in particular,

notwithstanding that the country is governed by a civil law system

owing much of its legal tradition to Germany. The reality is that

Japanese scholars, lawyers, and jurists increasingly look to American

legal theory, jurisprudence, and scholarship in their own legal

discourse, even on constitutional law, and thus this form of

comparative analysis is not at all unusual in the Japanese context.

48

B. Theories of Informal Amendment and the Issue of Legitimacy

Considerable differences exist among theorists who argue that

there has been constitutional change through some form of informal

amendment in the United States. They differ in terms of their

descriptive explanations of the modalities of the process, the scope of

the phenomenon, and the means of identifying any given informal

amendment. They also differ in terms of their normative claims

regarding the legitimacy, putative benefits, or perceived dangers of

informal amendments. Indeed, some of those who explain alternative

means of constitutional change do not use the term “informal

amendment” at all, and may not situate themselves directly within

MCGILL L.J. 673, 678 (2015) (arguing that efforts to deliberately create such constitutional

conventions are a form of informal amendment, but are illegitimate).

47. See, e.g., Carlos Bernal, Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments in the Case

Study of Columbia: An Analysis of the Justification and Meaning of Constitutional

Replacement Doctrine, 11 I

NT’L J. CONST. L. 339 (2013); Sujit Choudhry, Ackerman’s Higher

Lawmaking in Comparative Constitutional Perspective: Constitutional Moments as

Constitutional Failures, 6 I

NT’L J. CONST. L. 193 (2008).

48. See, e.g., Hidenori Tomatsu, Judicial Review in Japan: An Overview of Efforts to

Introduce U.S. Theories, in F

IVE DECADES OF CONSTITUTIONALISM IN JAPANESE SOCIETY

251-77 (Yoichi Higuchi ed., 2001); see also NOBUYOSHI ASHIBE, KENPŌ [CONSTITUTIONAL

LAW] (3d ed. 2002) (this seminal constitutional text imports, for instance, American levels of

scrutiny for judicial review of equality claims); S

HINEGORI MATSUI, NIHON KOKU KENPŌ

[J

APANESE CONSTITUTIONAL LAW] (2d ed. 2002) (Matsui, a former student of John Hart Ely,

is the primary proponent of process theory in Japanese constitutional discourse).

444 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

that debate, though their theories certainly implicate any discussion of

informal amendment.

49

Still, it is fair to say that all of the scholars

involved share the common purpose of trying to explain constitutional

change in more realistic and functional terms. They are trying to

address the fact that the US Constitution, as a system, has changed

markedly over its history, quite separate and apart from the changes

wrought by the few formal amendments, and in ways that are at times

very difficult to reconcile with most notions of legitimate interpretive

development.

50

As will become apparent in this Part, these explanations and the

differences among them give rise to a number of unresolved

questions. I want to suggest, however, that one of the most

fundamental of these questions relates to the issue of legitimacy. At

root, all of these theories and explanations are in some form or

another groping for a means of determining whether any particular

form of constitutional change is or is not legitimate. Indeed, these

explanations are to some degree motivated by the perceived problem

that traditional perspectives, which apparently accept all of these

problematic constitutional changes as “normal” interpretive

developments, are simply ignoring and papering over the questions of

legitimacy raised by potentially unauthorized forms of constitutional

change. But while this may be the subtext, the explanations do not all

address legitimacy explicitly, and those that do, tend to do so in

various ways and to differing degrees.

Before comparing their theoretical explanations, however, it is

worth pausing to further clarify what is meant here by the legitimacy

of constitutional change. There is, of course, considerable literature

on the distinction between legality, authority, legitimacy, and power,

not only in legal discourse but in political science and political

philosophy.

51

I will argue in Part III that the passage of time operates

to open up a distinction between the authority and legitimacy of

informal amendments. But in the first instance, at the time that change

occurs, I conceive of legitimacy as flowing from the formal

49. See, e.g., Balkin & Levinson, supra note 1.

50. See, e.g., Sanford Levinson, Introduction: Imperfection and Amendability, in

R

ESPONDING TO IMPERFECTION, supra note 1, at 3-11.

51. See, e.g., Dan Priel, The Place of Legitimacy in Legal Theory, 57 M

CGILL L.J. 1

(2011) (comparing legitimacy to validity, content, and normativity, with particular reference to

Dworkin).

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 445

constitutional authority—like Murphy, who uses legitimacy as

referring “not to popular support but to grounding in the existing

system’s fundamental normative principles.”

52

In this sense,

legitimacy and authority are closely aligned at the time of the

constitutional change, at least to the extent that the source of authority

is itself then accepted and acknowledged as valid and legitimate. In

this understanding, the authority for constitutional change relates to

the formal source of that authority in either constitutional text or other

fundamental normative principle. But the concept of legitimacy of the

change has an additional aspect that is related to the perception and

acceptance of the authoritativeness and validity of the change by

those subject to the constitution. There is thus a psychological

component to legitimacy, derived in the first instance from

perceptions of the principled nature, virtue or validity of the

institutional decision-maker or agent of change. It has been noted that

the Supreme Court of the United States has itself referred to

legitimacy in this sense, as depending in part upon the perceptions of

the people.

53

But over time (as will be discussed below) legitimacy

for a change initially viewed as insufficiently authorized, may

develop from mere acceptance or acquiescence, due to the extent to

which the change has become entrenched and insinuated into the

broader legal system.

54

Returning to the discussion of how legitimacy is treated within

informal amendment theory, Sandy Levinson is one theorist who does

discuss the issue. He suggests that to accept a given constitutional

interpretation as such, is to “accord it a certain dignity” as a legitimate

understanding of the Constitution, while formal amendments are ipso

facto legitimated by the authority of the formal amendment

procedure. Thus, he suggests that to reject that a putative

interpretation is the result of a good faith exercise in legitimate

interpretation, or that it can be plausibly supported by accepted

canons of constitutional interpretation, is to suggest that the effort is

52. Murphy, supra note 15, at 173.

53. Tom R. Tyler & Gregory Mitchell, Legitimacy and the Empowerment of

Discretionary Legal Authority: The United States Supreme Court and Abortion Rights, 43

D

UKE L. J. 703, 709 (1994) (citing Casey v. Planned Parenthood, 505 U.S. 833, 2814-16

(1992)).

54. Owen M. Fiss, Objectivity and Interpretation, 34 S

TAN. L. REV. 739, 756 (1982)

(citing H

ANS KELSEN, GENERAL THEORY OF LAW AND STATE (1945)). For further discussion,

see infra note 287 and accompanying text.

446 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

to surreptitiously amend the Constitution under the pretext of

interpretation.

55

This is to acknowledge that informal amendments

have a legitimacy problem, and even points to the fact that intent and

good faith are factors in determining legitimacy. Yet he does not

return to directly deal with the issue of how the legitimacy of any

given informal amendment is to be determined. The critics, of course,

squarely deny that informal amendments can ever be legitimate at

all.

56

I would suggest that the question of legitimacy has not been

sufficiently addressed in the discourse on informal amendment. Most

of the proponents of informal amendment theory do not identify the

factors that are essential to the legitimacy of constitutional change in

general, and the criteria that might be applied to assess the legitimacy

of specific changes, either at the time such change is unfolding or at

some time after the fact.

57

In the rest of this Section I will explore

several of the prominent theoretical explanations of constitutional

change, paying particular attention to how they address the question

of legitimacy, and more specifically how, under any particular

explanation, these factors may impact the legitimacy of any given

process of constitutional change.

It is helpful to be clear that these more realist and functional

explanations of constitutional change are responding to a perceived

traditional view. To varying degrees and in somewhat different ways,

the proponents of informal amendment claim that there is a

mythological and romantic conception of the US Constitution, in

response to which they are offering what they suggest is a more

realistic understanding.

58

The traditional narrative, they argue, tends

to exaggerate the importance of the constitutional text, the meaning of

which is understood to be authoritatively interpreted and enforced by

the courts. This traditional view downplays or discounts the extent to

55. Levinson, How Many Times Has the United States Constitution Been Amended?,

supra note 1, at 7, 17.

56. See, e.g., Barnett, supra note 1; Dow, supra note 1.

57. This is not to say, of course, that there has been no consideration of the question of

legitimacy. As discussed below, Ackerman does make a specific normative argument for the

legitimacy of certain forms of informal amendment; Brannon Denning proposes a theory for

the legitimacy of “constitutional change”, while carefully arguing that such change should not

be characterized as an amendment. See Brannon P. Denning, Means To Amend: Theories of

Constitutional Change, 65 T

ENN. L. REV. 155 (1997).

58. See, e.g., A

CKERMAN, supra note 1, at 162, 211-12.

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 447

which the Constitution is best understood as a system of principles,

norms, conventions, and institutions. A system defined and governed,

it is true, by the framework laid out in the constitutional document,

but nonetheless far more complex in operation than can be discerned

or even inferred from the mere text of the document. Moreover, under

the mythological or romantic view, the Constitution is viewed as the

highest law of the land that trumps all other law, due to the authority

it enjoys as a result of the super-majoritarian process by which it was

ratified and subsequently amended, consistent with the fundamental

ideals of popular sovereignty.

59

Finally, according to the critics,

myths have developed to explain dramatic constitutional changes,

such as those that accompanied the New Deal, such that they can be

implausibly reconciled with this traditional narrative and its principles

of interpretative development.

60

The proponents of informal

amendment are seeking to pull aside this formalistic account and

provide not only a more realistic description, but also a more

sophisticated functional explanation. And some of them are trying to

provide a normative defense of these extra-textual non-formal

amendments.

While these realist theories share a purpose of trying to better

explain constitutional change, the explanations tend to differ in their

understanding of the mechanisms and modalities of the process of

change. I should also emphasize that some of these explanations of

constitutional change relate to legitimate interpretive development as

well as to what we are here calling informal amendment—they

advance a more realistic account for all constitutional change along a

spectrum, and do not always focus on defining the dividing line

between interpretive change and informal amendment. Levinson

breaks down the forms of constitutional change along this conceptual

spectrum in the following way: (i) regular interpretation, typically by

the judiciary; (ii) interpretive change in government powers effected

by permissible legislation, executive order, or other policy; (iii)

amendment, which represents a genuine change that is “not immanent

within the pre-existing materials or allowable simply by the use of

powers granted (or tolerated) by the [C]onstitution”; (iv) revision,

which is a more significant kind of amendment, that alters more

59. ESKRIDGE & FEREJOHN, supra note 1, at 34.

60. A

CKERMAN, supra note 1, at 199, 210-211.

448 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

fundamental aspects of the Constitution, but is nonetheless congruent

with the values of the Constitution, and effected through the formal

amendment procedure for such revision; and (v) revolutionary

change, being constitutional change of such a dimension that it is not

consistent with the immanent constitutional order, and which is

“legitimated, if at all, by some extra-constitutional set of events.”

61

The “amendment” in (iii) is, to the extent it is not done in accordance

with the amending formula, what we are calling informal amendment.

We need not concern ourselves here with the distinction between

“amendment” and “revision,” but are interested in the difference

between “amendment” and the two forms of “interpretive change” on

the one hand, or “revolution” on the other.

While differing in their emphasis, the most common

explanations tend to focus on changes arising from some combination

of the judgments of courts, the implementation of law and policy by

the political branches and the bureaucracy, and activities of various

actors within civil society. As Jack Balkin describes it, constitutional

change generally comes through a recursive process in which courts

develop and apply constitutional constructions, which are more than

mere interpretations of the text but rather are doctrines and tests

developed for use in the analysis and application of principles and

standards articulated in the Constitution.

62

But construction is also

developed by political branches of government and applied in the

form of new laws, policies, institutions, and practices, and then

pressed upon the judiciary to accept and endorse in the course of

constitutional litigation. What is more, the political branches

frequently develop such constructions under pressure or influence

from other actors in civil society. There is, therefore, a recursive

dialectical process among all these actors that leads to new

constitutional constructions.

63

Most of the results of this process of constitutional change would

be characterized by many or even most jurists as being within the

61. Levinson, How Many Times Has the United States Constitution Been Amended?,

supra note 1, at 21. It should be noted that different scholars use the term or concept of

“revision” somewhat differently, but here Levinson is drawing from certain State constitutions,

such as that of California, that explicitly contemplate a revision as being a more fundamental

and significant form of amendment. We can put this distinction to one side for the moment.

62. Balkin, supra note 28, at 6-7.

63. Id. at 8-10.

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 449

scope of legitimate interpretive development, and thus not within the

realm of informal amendment. But the implication here is that there

will be times when the dialectic process results in “state building

constructions,” by which Balkin means new constructions that both

constitute significant interpretive moves and result in the construction

of new state capacities.

64

Some of these state building constructions

will exceed the range of reasonable meaning supported by most

theories of constitutional interpretation, at which point we have what

some would call informal amendment.

Some (but by no means all) proponents of informal amendment

have drawn examples from the New Deal as reflecting this kind of

combined construction, with judicial ratification of government action

in the form of judgments that exceeded the limits of normal

interpretive development.

65

This would include several of the

innovative government programs, such as the National Labor

Relations Act

66

and the Social Security Act,

67

advanced by the

Roosevelt administration during the later stages of the New Deal.

These were then validated in a string of decisions by the Supreme

Court, which had begun to exhibit a clearly shifting understanding of

the relevant provisions of the Constitution.

68

The constitutional

changes wrought during the later stages of the New Deal quite

obviously reflect one of the primary practical examples of the

difficulty in determining the border between legitimate interpretive

development and informal amendment. Ackerman, Strauss, and

Levinson are just some of the more prominent scholars to suggest that

these changes exceeded the range of normal interpretive development,

while Stephen Holmes and Cass Sunstein, David Dow, and many

others involved in the debate clearly disagree.

69

64. Id. at 9. See also Heather Gerken, The Hydraulics of Constitutional Reform, supra

note 1, (arguing that informal amendment is the result of a dialogical process involving inter-

institutional debate and input from civil society).

65. A

CKERMAN, supra note 1, at 1-420; ESKRIDGE & FEREJOHN, supra note 1, at 46;

Strauss, supra note 1, at 1475-76; Balkin, supra note 28, at 11-12; Stephen Griffin, The

Problem of Constitutional Change, 70 T

UL. L. REV. 2121 (1996).

66. National Labor Relations Act of 1935, Pub. L. No. 74-198, 49 Stat. 449 (codified as

amended at 29 U.S.C. §§ 151-169 (2012)).

67. Social Security Act, Pub. L. No. 74-271, 49 Stat. 620 (codified as amended at 42

U.S.C. ch. 7 (2012)).

68. A

CKERMAN, supra note 1, at 141-50.

69. See, e.g., Dow, supra note 1, at 126-27; Sunstein, supra note 1, at 279, n.9.

450 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

What is less clear in the debate, however, is how the proponents

of informal amendment understand the legitimacy of these changes.

Ackerman, as we will see below, makes very explicit claims

regarding their legitimacy, but many of the others do not. If the

decisions of the Supreme Court that ratified or acquiesced in these

changes exceeded the range of reasonable interpretation, were they

thus illegitimate at the time? Did the fact that Roosevelt and his

Cabinet thought the programs were constitutional, and that the

Supreme Court of the early 1930s had been wrong in its

understanding of the relevant provisions of the Constitution, make a

difference to how legitimate the changes were at the time? To put it

another way, if there was evidence that Roosevelt thought that his

programs were inconsistent with the Constitution but he set out to

implement them anyway in order to force an informal change to

constitutional understanding, rather than pursue a formal Article V

amendment, would that (or should that) influence our assessment of

their legitimacy?

The proponents of informal amendment do not directly explore

these questions in any sort of comprehensive way. Ackerman, one of

the few who tackles legitimacy head on, focuses on the role of

expressions of popular will as legitimating these changes, rather than

on the intent of the agents of change.

70

What is clear, however, is that

none of the proponents of informal amendment argue that the changes

are now illegitimate. In other words, with the passage of time the

changes were entrenched and at some point accepted as legitimate

within the constitutional system.

Some observers, such as David Strauss (who goes so far as to

argue that informal amendments are far more significant mechanisms

of constitutional change than formal amendments),

71

go further back

in time to identify such cases as McCulloch v. Maryland

72

as being

illustrative of this process of combined government-judiciary

constructions. In McCulloch the Supreme Court adopted a very broad

interpretation of the Necessary and Proper Clause

73

to validate the

70. ACKERMAN, supra note 1, at 141-50.

71. Strauss, supra note 1, at 1459.

72. McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819).

73. U.S.

CONST. art. I, § 8, cl. 18 (which provides that: “The Congress shall have

Power. . . To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 451

Federal Government’s constitutional authority to establish the Second

Bank of the United States.

74

When Hamilton had earlier relied on

similar arguments to justify the establishment of the First Bank,

James Madison had responded that the Constitution would not likely

have been ratified had the clause been so understood at the time. Yet

some twenty five years later, as President Madison, he accepted that

this understanding was by then entrenched and so must be accepted.

75

While Strauss does not make explicit what his views are on the

legitimacy of the decision in McCulloch at the time it was made, the

implication is certainly that the Court’s judgment was outside of the

reasonable range of meanings supported by accepted theories of

constitutional interpretation. That would suggest that Strauss

considers it to have been illegitimate at the time. Yet he describes

how it became accepted—and thereby arguably legitimate—with the

passage of time; and in Madison’s eyes, the passage of a mere twenty

five years was sufficient.

While Strauss and others tend to emphasize the judicial role in

this process, others such as Eskridge and Ferejohn tend to focus on

the role of legislation, and of unelected officials within both the

legislature and the executive, in driving change.

76

Again, this

approach is more of a shift in emphasis than an entirely different

theory of change. It too is responding to the formalistic and traditional

view of constitutional law, an account which critics such as Eskridge

argue must be revised to acknowledge the role of “super-statutes” and

“administrative constitutionalism” in expanding and developing the

constitutional system.

77

Without getting into the details of their

explanations, they rely to a considerable extent on the deliberative

process by which these super-statutes are enacted. It is for this reason

that Eskridge and Ferejohn term the process “administrative

the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of

the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.”).

74. See Strauss, supra note 1; see also A

CKERMAN, supra note 1, at 126 (in which

Ackerman also identifies McCulloch v. Maryland, and the consequent expansion of the

Necessary and Proper clause, as an informal amendment).

75. Strauss, supra note 1, at 1473; see P

ETER SUBER, THE PARADOX OF SELF-

A

MENDMENT 197-206 (1990); JAMES BOYD WHITE, WHEN WORDS LOSE THEIR MEANING

263 (1984); see also Levinson, How Many Times Has the United States Constitution Been

Amended?, supra note 1, at 22.

76. E

SKRIDGE & FEREJOHN, supra note 1.

77. Id. at 26.

452 FORDHAM INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 40:2

constitutionalism,” in contrast to a “judicial constitutionalism” that

emphasizes the role of the judiciary in driving interpretive change.

78

This emphasis on the deliberative process and the extent to which the

statutes reflect the popular will might be seen as grounding some

claim to legitimacy. But suppose that the judicial decisions ratifying

these super statutes provide interpretations of the implicated

constitutional provisions that are outside the reasonable range of

legitimate interpretation—Eskridge and Ferejohn do not actually

focus directly on the issue of whether such changes may raise

questions of legitimacy.

The proponents of informal amendment who are clearest on the

issue of legitimacy are perhaps Ackerman and Amar, both of whom

ground their arguments in favor of informal amendment in notions of

popular sovereignty (though in strikingly different ways). Ackerman,

who is perhaps the most closely associated with theories of informal

amendment, also delves more deeply into the process by which such

amendments might unfold and the form they might take. In so doing

he provides some criteria for how to assess constitutional changes that

are candidates for classification as informal amendment.

79

He begins

with the notion that while most law is made by the government, there

is also (in the American context at least) a “higher law” that is created

by the people. From this he argues that informal amendment can be

characterized as an example of this form of higher law, which may be

made in violation of the formal amendment procedure, and yet still

fall within the framework of the Constitution and be consistent with

its underlying vision.

80

This creation of higher law by the people

occurs in “constitutional moments,” characterized by a response to

some form of constitutional crisis. Three examples of such

constitutional moments that lead to informal amendments, in

Ackerman’s view, are the original drafting and ratification process (as

a change to the Articles of Confederation), the Reconstruction

Amendments, and the New Deal programs discussed above. From

these examples he abstracts a five-stage model of the process by

which this form of constitutional change occurs.

81

78. Id. at 33.

79. A

CKERMAN, supra note 1, at 403-20.

80. Id. at 248, 296.

81. Id. at 402.

2017] REINTERPRETING JAPAN'S WAR POWERS 453

The first stage is characterized by a constitutional impasse, in

which there is increasing disagreement over not only specific

substantive policy being pursued by one of the political branches, but

also over the extent to which such policy is constitutionally

permissible. In the New Deal this impasse was over the President’s

efforts, through both executive orders and federal legislation, to

establish a foundation for more progressive social welfare, labor, and

financial regulatory regimes.

82

The second stage is electoral success