What GAO Found

United States Government Accountability Office

Why GAO Did This Study

Highlights

Accountability Integrity Reliability

June 2006

HIGHWAY FINANCE

States’ Expanding Use of Tolling

Illustrates Diverse Challenges and

Strategies

Highlights of

GAO-06-554, a report to

congressional requesters

Congestion is increasing rapidly

across the nation and freight traffic

is expected to almost double in 20

years. In many places, decision

makers cannot simply build their

way out of congestion, and

traditional revenue sources may

not be sustainable. As the baby

boom generation retires and the

costs of federal entitlement

programs rise, sustained, large-

scale increases in federal highway

grants seem unlikely. To provide

the robust growth that many

transportation advocates believe is

required to meet the nation’s

mobility needs, state and local

decision makers in virtually all

states are seeking alternative

funding approaches. Tolling

(charging a fee for the use of a

highway facility) provides a set of

approaches that are increasingly

receiving closer attention and

consideration. This report

examines tolling from a number of

perspectives, namely: (1) the

promise of tolling to enhance

mobility and finance highway

transportation, (2) the extent to

which tolling is being used and the

reasons states are using or not

using this approach, (3) the

challenges states face in

implementing tolling, and (4)

strategies that can be used to help

states address tolling challenges.

GAO is not making any

recommendations. GAO provided

a draft of this report to U.S.

Department of Transportation

(DOT) officials for comment. DOT

officials generally agreed with the

information provided.

Tolling has promise as an approach to enhance mobility and finance

transportation. Tolling can potentially enhance mobility by reducing

congestion and the demand for roads when tolls vary according to

congestion to maintain a predetermined level of service. Such tolls can

create incentives for drivers to avoid driving alone in congested conditions

when making driving decisions. In response, drivers may choose to share

rides, use public transportation, travel at less congested times, or travel on

less congested routes, if available. Tolling also has the potential to provide

new revenues, promote more effective investment strategies, and better

target spending for new and expanded capacity. Tolling can also potentially

leverage existing revenue sources by increasing private-sector participation

and investment.

Over half of the states in the nation have or are planning toll roads to

respond to what officials describe as shortfalls in transportation funding, to

finance new highway capacity, and to manage road congestion. While the

number of states that are tolling or plan to toll has grown since the

completion of the Interstate Highway System, and many states currently

have major new capacity projects under way, many states report no current

plans to introduce tolling because the need for new capacity does not exist,

the approach would not generate sufficient revenues, or they have made

other choices.

According to state transportation officials who were interviewed as part of

GAO’s nationwide review, substantive challenges exist to implementing

tolling. For example, securing public and political support can prove

difficult when the public and political leaders argue that tolling is a form of

double taxation, is unreasonable because tolls do not usually cover the full

costs of projects, and is unfair to certain groups. Other challenges include

obtaining sufficient statutory authority to toll, adequately addressing the

traffic diversion that might result when motorists seek to avoid toll facilities,

and coordinating with other states or jurisdictions on tolling projects.

GAO’s review of how states implement tolling suggests three strategies that

can help facilitate tolling. First, some states have developed policies and

laws that facilitate tolling. For example, Texas enacted legislation that

enables transportation officials to expand tolling in the state and leverage

tax dollars by allowing state highway funds to be combined with other funds.

Second, states that have successfully advanced tolling projects have

provided strong leadership to advocate and build support for specific

projects. In Minnesota, a task force was convened to explore tolling and

ultimately supported and recommended a tolling project. Finally, tolling

approaches that provided tangible benefits appear to be more likely to be

accepted than projects that offer no new tangible benefits or choice to users.

For example, in California, toll prices on the Interstate 15 toll facility are set

to keep traffic flowing freely in the toll lanes.

www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?GAO-06-554.

To view the full product, including the scope

and methodology, click on the link above.

For more information, contact JayEtta Z.

Hecker at (202)512-2834 or

Page i GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

Contents

Letter 1

Results in Brief 2

Background 5

Tolling Has Promise as an Approach for Enhancing Mobility and for

Financing Transportation 11

States’ Use of Tolling to Address Funding Shortfalls, Finance New

Capacity, and Manage Congestion Is Expanding; but for Some

States, Tolling Is Not Viewed as Feasible 20

States That Are Considering and Implementing a Tolling Approach

Face Two Broad Types of Challenges 32

Three Broad Strategies Can Help State Transportation Officials

Address Challenges to Tolling 42

Concluding Observations 53

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 54

Appendixes

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 56

Appendix II: Correlation Analysis 59

Appendix III: Survey Questions 62

Appendix IV: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 65

Tables

Table 1: Tolling-Related Programs Authorized in Surface

Transportation Legislation 9

Table 2: Questions That Can Be Considered When Planning and

Designing Toll Projects 48

Table 3: Results of Correlation Analysis 61

Figures

Figure 1: State Highway Revenue Sources, Fiscal Year 2004 6

Figure 2: Annual Delay per Traveler in Selected Urban Areas, 1982,

1993, and 2003 12

Figure 3: Combined Federal and Average State Motor Fuel Tax

Rates 16

Figure 4: Existing Toll Road Facilities 21

Figure 5: Planned Toll Road Facilities 23

Figure 6: Conceptual Drawing of the Trans Texas Corridor 27

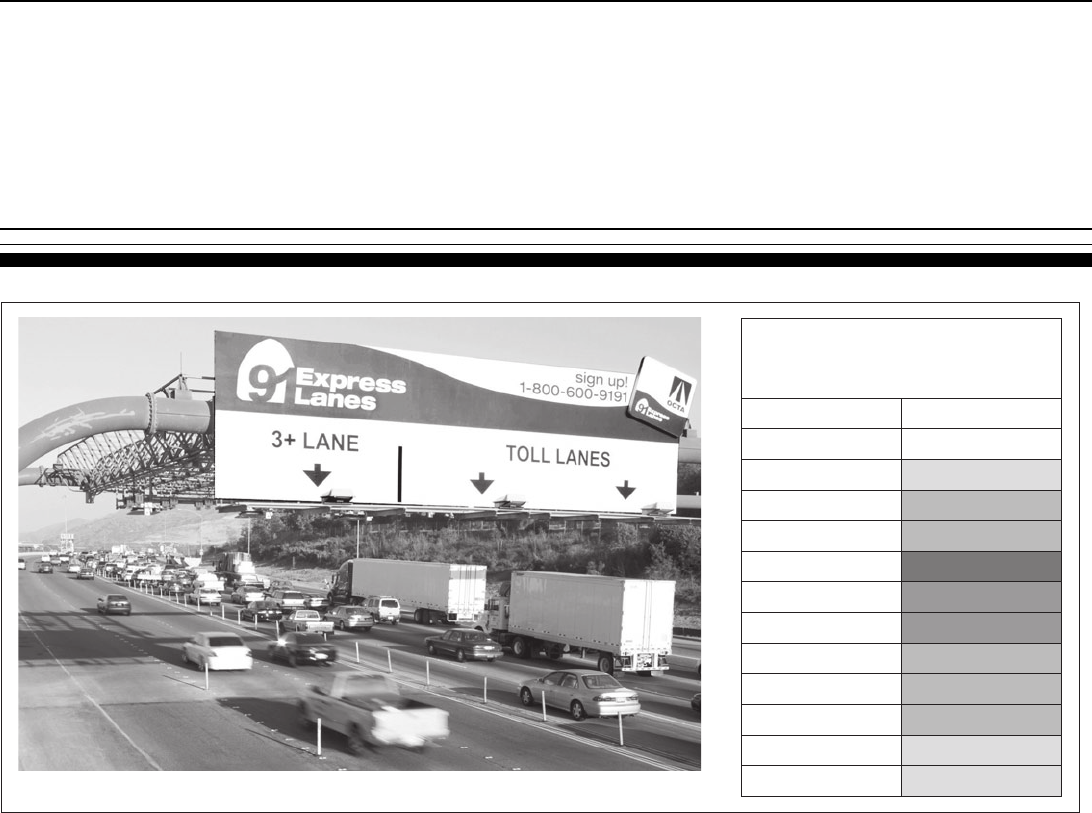

Figure 7: California State Route 91 Express Lanes and Toll

Rates 30

Figure 8: Challenges to Tolling 33

Contents

Page ii GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

Figure 9: Challenges to Tolling 34

Figure 10: Challenges to Tolling 39

Figure 11: Strategies to Address Challenges to Tolling 42

Figure 12: Strategies to Address Challenges to Tolling 43

Figure 13: Strategies to Address Challenges to Tolling 46

Figure 14: Strategies to Address Challenges to Tolling 51

Abbreviations

BEA Bureau of Economic Analysis

EIS environmental impact statement

FHWA Federal Highway Administration

GDP gross domestic product

HOT high occupancy toll

HOV high occupancy vehicle

ISTEA Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991

MPO metropolitan planning organization

PPP public-private partnership

PPTA Public-Private Transportation Act of 1995

ROD Record of Decision

SAFETEA-LU Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity

Act: A Legacy for Users

SEP-15 Special Experimental Projects 15

State DOT State Department of Transportation

TEA-21 1998 Transportation Equity Act for the 21

st

Century

TIFIA Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act of

1998

TOT truck-only toll

TTC Trans Texas Corridor

U.S. DOT U.S. Department of Transportation

VMT vehicle miles traveled

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. It may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further

permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or

other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to

reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

United States Government Accountability Office

Washington, D.C. 20548

Page 1 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

A

June 28, 2006 Letter

The Honorable James M. Inhofe

Chairman

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

The Honorable Christopher S. “Kit” Bond

Chairman

Subcommittee on Transportation and Infrastructure

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

The nation’s highways are critical to providing for and enhancing

mobility—the free flow of passengers and goods—and to sustaining

America’s economic growth. Mobility gives people access to goods,

services, recreation, and jobs; gives businesses access to materials,

markets, and people; and promotes the movement of personnel and

materiel to meet national defense needs. During the twentieth century,

motor fuel taxes were the mainstay of highway financing, and during the

latter part of that century the construction of the 47,000 mile Interstate

Highway System dominated the agendas and activities of state and federal

highway decision makers. In the twenty-first century, state and local

transportation officials are on the front lines of transportation decision

making and face a new and daunting set of challenges. Congestion is

increasing rapidly across the nation, particularly in urban areas, and freight

traffic is expected to almost double in 20 years. In many places, decision

makers cannot simply build their way out of congestion, and traditional

revenue sources may not be sustainable. As the baby boom generation

retires and the costs of federal entitlement programs rise, sustained, large-

scale increases in federal highway grants seem unlikely. To provide the

robust growth that many transportation advocates believe is required to

meet the nation’s mobility needs, state and local decision makers in

virtually all states are seeking alternative funding approaches. Tolling (i.e.,

charging a fee for the use of a highway) provides a set of approaches that

are increasingly receiving closer attention and consideration.

As requested, this report provides information on states’ experiences with

tolling and provides some insights on issues that state transportation

officials have encountered when considering or implementing a tolling

approach. Specifically, this report examines (1) the promise of tolling to

enhance mobility and finance highway transportation, (2) the extent to

Page 2 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

which tolling is being used in the United States and the reasons states are

using or not using this approach, (3) the challenges states face in

implementing tolling, and (4) strategies that can be used to help states

address the challenges to tolling.

To fulfill our objectives, we reviewed and analyzed research reports and

analytical studies; interviewed a wide range of stakeholders, including state

and local transportation officials, project sponsors, and private-sector

representatives; conducted a nationwide survey of state departments of

transportation; and conducted semistructured interviews with state

department of transportation officials. We also performed a correlation

analysis to identify the extent to which state financial and demographic

characteristics are associated with states’ use of tolling. In addition, we

interviewed transportation stakeholders in six states that were either

planning toll projects or constructing toll projects. In addition to our survey

and semistructured interviews, states planning toll roads were identified

through an analysis of states’ participation in Federal Highway

Administration (FHWA) tolling programs, including the Interstate System

Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Pilot Program and the Value Pricing

Pilot, and states constructing toll roads were identified through an analysis

of relevant reports and studies. During our review, we determined that a

number of states with toll bridges or tunnels do not have or are not

considering the tolling of roads. We, therefore, decided to exclude toll

bridges and tunnels from our definition of states tolling or planning to toll

to more accurately report on the challenges to tolling. Although we discuss

the federal role with regard to states’ experience with tolling, we did not

assess the effectiveness of federal toll programs or the potential effects of

federal grant programs on states’ experience with the approach. (See app. I

for our objectives, scope, and methodology.) We performed our work from

June 2005 through June 2006 in accordance with generally accepted

government auditing standards.

Results in Brief

Tolling has promise as an approach to enhance mobility and finance

transportation. A tolling approach can potentially help enhance mobility by

managing congestion. Congestion impedes both passenger and freight

mobility and is increasing as a result of rapid population growth and more

vehicles traveling farther on our roads. Applying tolls that vary with the

level of congestion—congestion pricing—can potentially reduce

congestion and the demand for roads because tolls that vary according to

the level of congestion can be used to maintain a predetermined level of

service. Such tolls create additional incentives for drivers to avoid driving

Page 3 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

alone in congested conditions when making driving decisions. In response,

drivers may choose to share rides, use public transportation, travel at less

congested (generally off-peak) times, or travel on less congested routes, if

available, to reduce their toll payments. For example, a study of the State

Route 91 Express Lanes in California found that when tolls increased 50

percent during peak hours, traffic during those hours dropped by about

one-third. As concerns about the sustainability of traditional financing

sources continue to grow, tolling also has promise to improve investments

and raise revenue. The per-gallon fuel tax, the mainstay of transportation

finance for 80 years, is declining in purchasing power because fuel tax rates

are not increasing, and more fuel-efficient vehicles and alternative-fueled

vehicles undermine the long-term viability of fuel taxes as the basis for

financing transportation. In this environment, tolling potentially has

promise to promote more effective infrastructure investment strategies by

better targeting spending for new and expanded capacity. For example,

among other factors, toll project construction is typically financed by

bonds, and projects must pass the test of market viability and meet goals

demanded by investors, although even with this test, there is no guarantee

that projects will always be viable. Tolling can also potentially enhance

private-sector participation and investment in major highway projects.

Tolling’s promise is particularly important in light of long-term pressures on

the federal budget.

According to our survey of state transportation officials, 31 of the 50 states

and the District of Columbia have or are planning toll roads, including 24

states that are operating toll roads and 7 states that are planning to toll.

Tolling grew in the 1940s and 1950s and, after a period of slower growth,

states’ tolling again began to expand in the 1990s. In total, 23 states are in

some phase of planning new toll roads. Officials in the 31 states that have

toll roads or are planning toll roads indicated that their primary reasons for

using or considering the use of a tolling approach was to address

transportation funding shortfalls, finance new capacity, and manage

congestion. For example, in Texas, tolling is being used to finance major

new capacity projects, such as the Trans Texas Corridor (TTC)—a

proposed multiuse, statewide network of transportation routes that will

incorporate existing and new highways—and to manage congestion in

Houston and other metropolitan areas. Transportation officials in some

states, however, have told us that tolling is not feasible because of limited

need for new capacity, insufficient tolling revenues, and public and political

opposition to tolling. For example, officials from nearly every state that is

not pursuing tolling mentioned some form of public or political opposition

to toll roads. In New Jersey, officials told us that opposition to new toll

Page 4 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

roads is strong because many state border crossings and major highways

are already tolled.

State transportation officials face two types of challenges that are broadly

related to securing support for and implementing a tolling approach to

finance transportation. The first type of challenge, according to

transportation officials, is the difficulty of obtaining public and political

support in the face of opposition from the public and political leaders in

states where tolling is being considered and applied. According to

transportation officials with whom we spoke, opposition is largely based

on arguments that (1) fuel taxes and other dedicated funding sources are

used to pay for roads and tolling is, therefore, a form of double taxation; (2)

a tolling approach is unreasonable because tolls often do not cover the

costs of a project; and (3) applying tolls can produce regional, income, and

other inequities. For example, a Wisconsin transportation official told us

that Wisconsin is not implementing a tolling approach because the public

generally believes that fuel taxes already pay for roads and tolls would

adversely affect the state’s tourist economy, while Kentucky and Arkansas

officials said that it would be difficult to undertake tolling unless toll roads

could be largely financially self-sufficient. In Florida, concerns about

regional inequity led local governments to pass a law that led to the state’s

taking action to ensure that spending on facilities in three counties was

commensurate with toll collections in those three counties. The second

type of challenge is the practical difficulty of implementing tolling,

including obtaining the statutory authority to toll, addressing the traffic

diversion that might result when motorists seek to avoid toll facilities, and

coordinating with other states or jurisdictions. For example, Minnesota had

legislation authorizing tolling, but conditions built into the legislation, most

importantly, local government veto authority that could be exercised

without recourse, prevented transportation officials from implementing a

specific project. As a result, when state decision makers identified a toll

project that would convert underused high occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes

to high occupancy toll (HOT) lanes that would allow non-HOV’s to use the

lanes for a fee—the Interstate 394 optional toll lane project—state decision

makers pursued specific legislation that exempted HOV to HOT lane

conversions from local veto, thus providing an opportunity to advance the

Interstate 394 optional toll lane project several years later.

Through our review of the ways states use tolling, we have identified three

broad strategies that have both short-term and long-term relevance for

state transportation officials who are considering tolling. The first strategy

that transportation officials can consider involves developing policies and

Page 5 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

laws that facilitate the use of tolling to finance transportation. In

developing such a framework, transportation officials can, first, build

support for the approach by establishing a rationale for its use and then

secure the legislative authority to use the approach. For example, to

expand the use of tolling and to leverage tax dollars by allowing state

highway funds to be combined with other funds, Texas enacted legislation

that enabled transportation officials to realize these goals. The second

strategy that transportation officials can consider involves providing

leadership to build support for individual projects and addressing the

challenges to tolling in project design. For example, in Minnesota, a task

force of state and local officials, citizens, and business leaders was

convened in 2001 to explore a range of road pricing options, including the

conversion of HOV lanes to HOT lanes, and make recommendations to

elected officials. Since tolling had been fairly controversial in the past,

decision makers believed that a task force would provide a more credible

and independent voice to the general public. Ultimately, the task force

supported the HOV to HOT conversions and, with the governor’s support

and the passage of legislation authorizing the conversion, the project was

implemented. The last strategy that transportation officials can consider

involves selecting a tolling approach and a project that provides tangible

benefits. Promoting a project that provides tangible benefits can potentially

help transportation officials justify both the costs of the project and the

fees that users will be required to pay for the service. Although tolling can

take different forms and decisions about its use are state specific, in

concept, a tolling structure that varies with the level of congestion—

congestion pricing—offers increased predictability and, as a result,

provides tangible benefits to users. While actual experience with

congestion pricing is still fairly limited in the United States, projects in

operation illustrate how transportation officials have advanced projects

seeking to achieve the potential benefits that may result from congestion

pricing. For example, toll prices on Interstate 15 in San Diego are set

dynamically, changing every 6 minutes, which has succeeded in keeping

traffic flowing freely.

The U.S. Department of Transportation reviewed a draft of this report.

Officials from the Department indicated that they generally agreed with the

information provided and provided technical clarifications, which we

incorporated as appropriate.

Background

The responsibility for building and maintaining highways in the United

States rests with state departments of transportation in each of the 50

Page 6 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. In addition, local

governments finance road construction through sources such as property

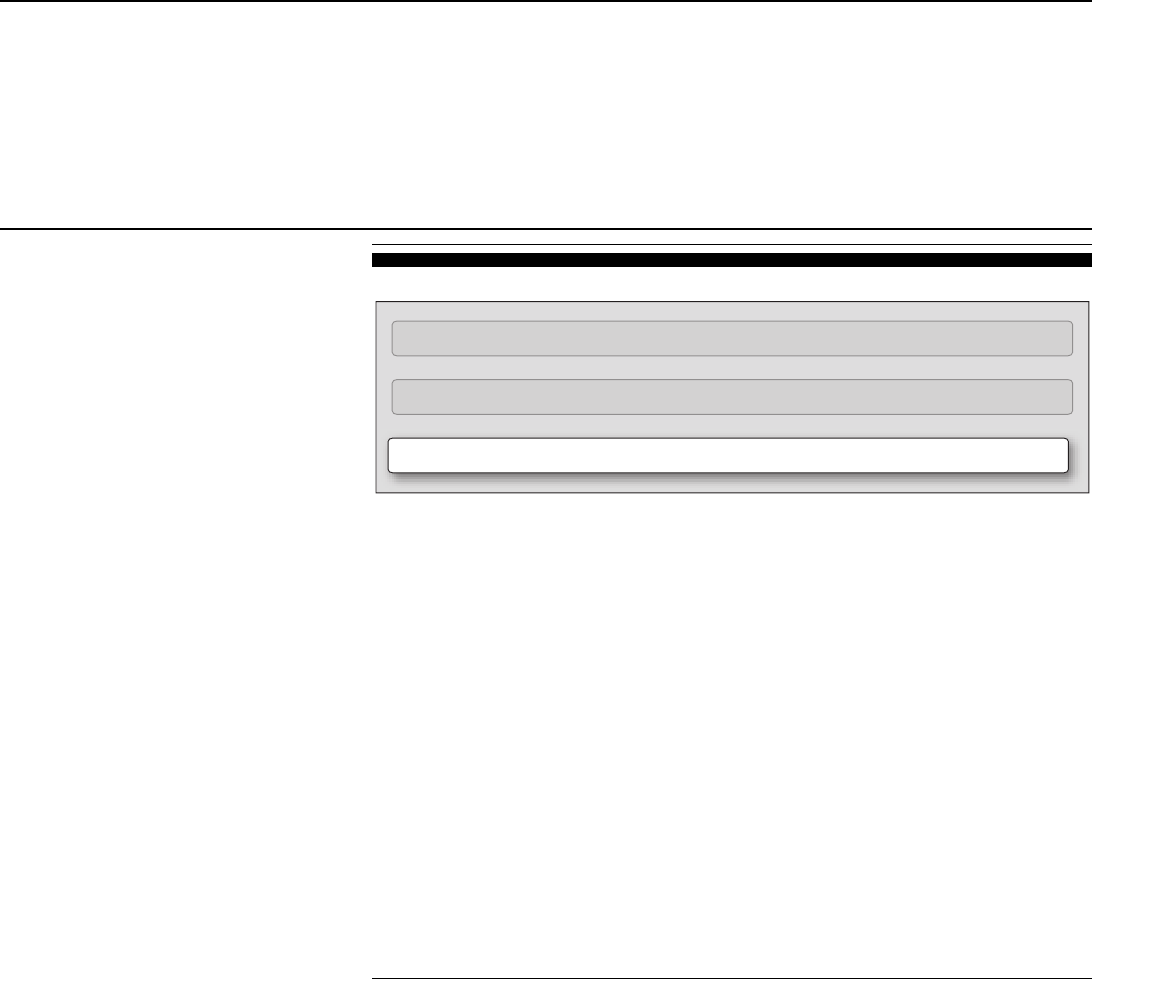

and sales taxes. In 2004, state governments took in about $104 billion from

various sources to finance their highway capital and maintenance

programs—44 percent of these revenues came from state fuel taxes and

other state user fees, and 28 percent came from federal grants. Sources of

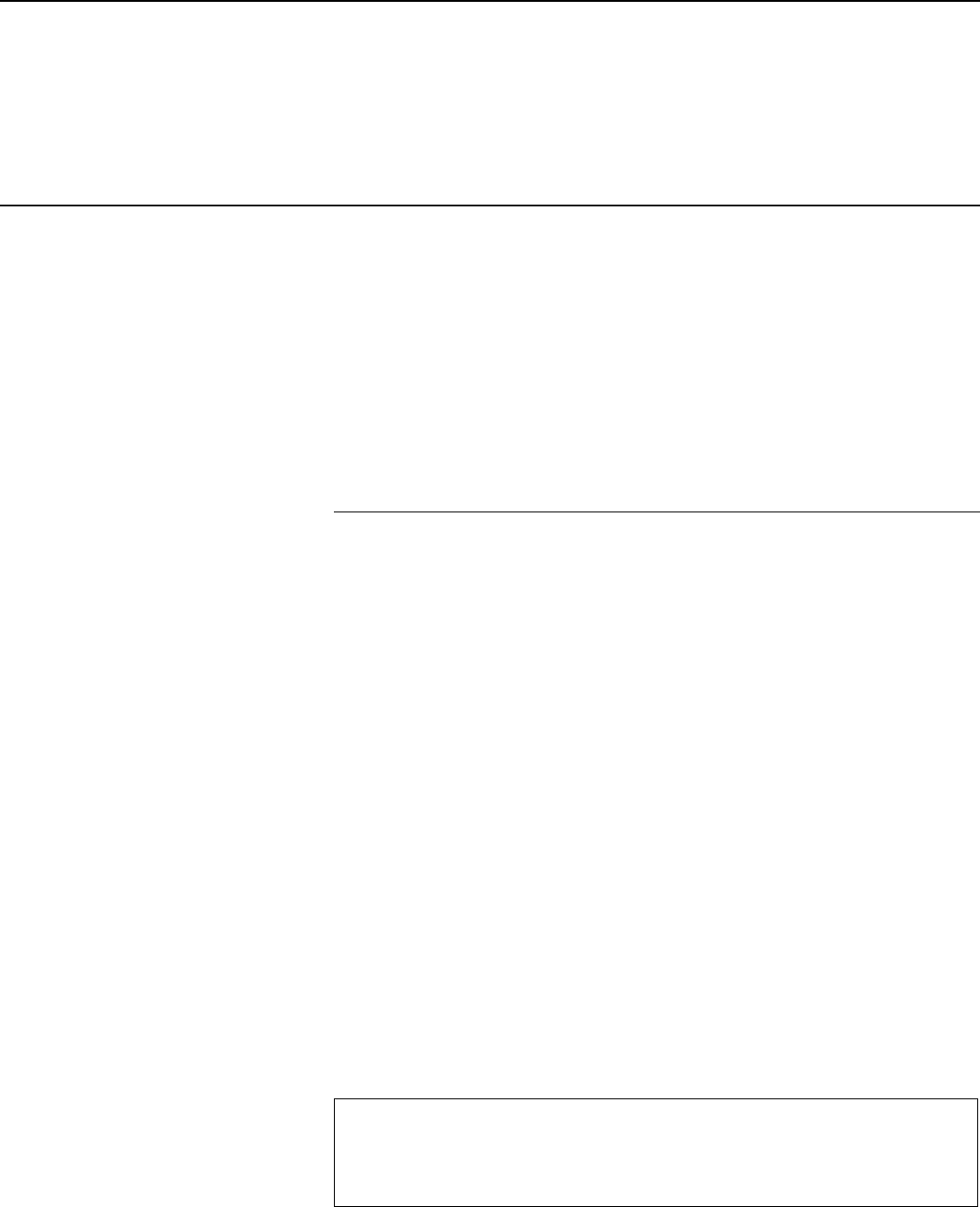

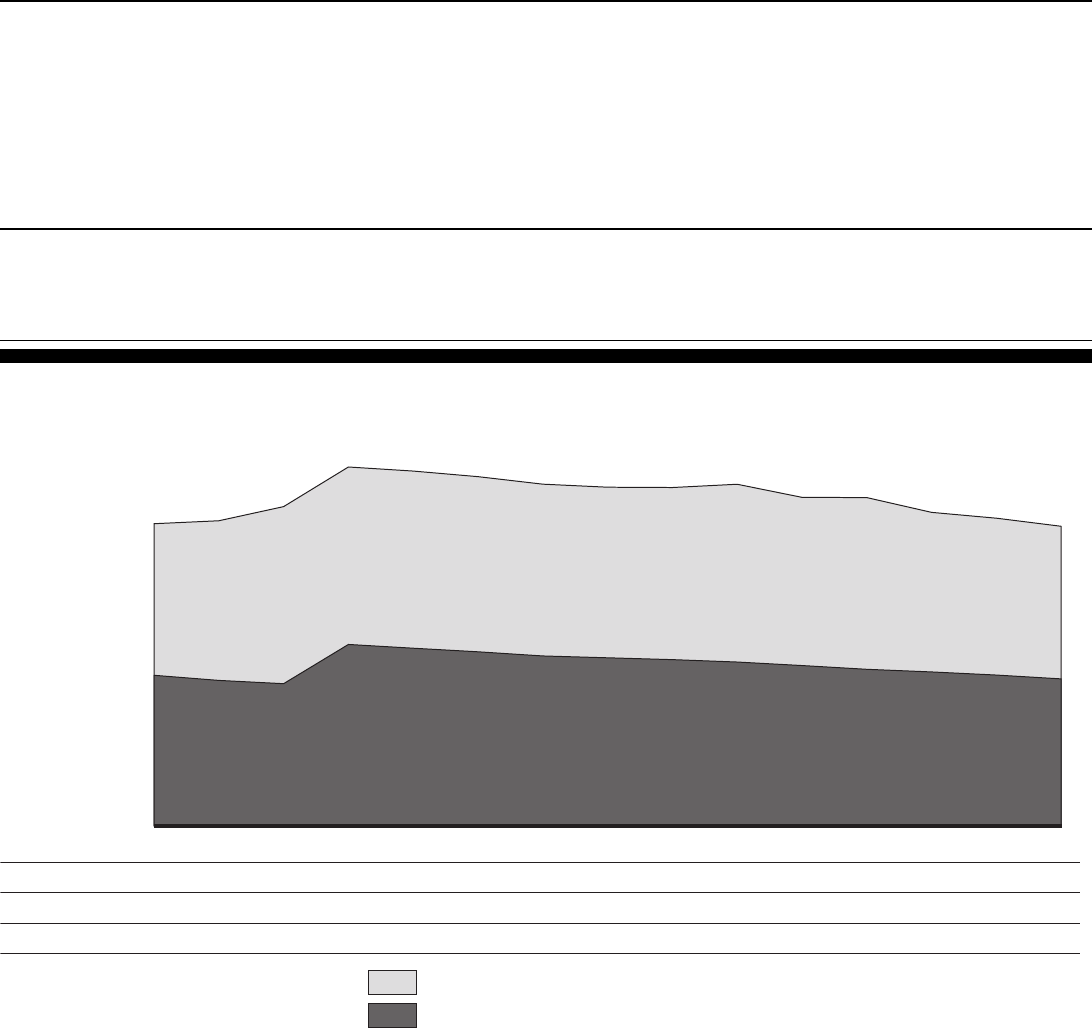

state highway revenues in 2004 are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: State Highway Revenue Sources, Fiscal Year 2004

FHWA administers federal grant funds through the federal-aid highway

program and distributes highway funds to the states through annual

apportionments established by statutory formulas. Once FHWA apportions

these funds, they are available to be obligated for the construction,

reconstruction, and improvement of highways and bridges on eligible

federal-aid highway routes and for other purposes authorized in law. Within

these parameters, responsibility for planning and selecting projects

generally rests with state departments of transportation (DOT) and with

metropolitan planning organizations, and these states and planning

organizations have considerable discretion in selecting specific highway

projects that will receive federal funds. For example, section 145 of title 23

5%

28%

15%

52%

Tol ls

State general

revenues

Other

(local contributions, bond proceeds,

and miscellaneous)

Federal grants

State fuel taxes

and user fees

State funds

8%

44%

Source: FHWA.

Page 7 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

of the United States Code describes the federal-aid highway program as a

federally assisted state program and provides that the federal authorization

of funds, as well as the availability of federal funds for expenditure, shall

not infringe on the states' sovereign right to determine the projects to be

federally financed.

About 5 percent of the highway revenues to the states in 2004 came from

tolls. In 2005, the United States had about 5,000 miles of toll facilities in

operation or under construction, including about 2,800 miles, or 6 percent,

of the Interstate Highway System, according to FHWA.

1

Tolling of roads

began in the late 1700s. From 1792 through 1845, an estimated 1,562

privately owned turnpike companies managed and charged tolls on about

15,000 miles of turnpikes throughout the country.

2

Between 1916 and 1921,

the number of automobiles in the United States almost tripled, from 3.5

million to 9 million, and as automobile use increased, pressure grew for

more government involvement in financing the construction and

maintenance of public roads.

3

In 1919, Oregon became the first state to

impose a motor fuel tax to finance roadway construction.

4

In 1916, the

Federal Aid Road Act provided states with federal funds to finance up to 50

percent of the cost of roads and bridges constructed to provide mail

service. This act and its successor, the 1922 Federal Highway Act,

prohibited tolling on roads financed with federal funds.

In the 1930s and 1940s, President Roosevelt led the thinking for developing

a series of interconnected systems of toll roads that crossed the United

States, which was the beginning of the idea of an interstate highway

system. Then, between 1940 and 1952, 5 states opened such highways,

1

Federal Highway Administration, Toll Facilities in the United States Interstate System

Toll Roads in the United States, Table T-1, Part 3 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 1, 2005) and

Federal Highway Administration, Toll Facilities in the United States Facts (Washington,

D.C.: Jan. 1, 2005).

2

Turnpike is a term used interchangeably with toll road, which is a highway that requires toll

collections from all drivers (usually with the exception of emergency vehicles). Typically,

the tolls are used to support operations and maintenance, as well as to pay debt service on

the bonds issued to finance the toll facility.

3

Tom Lewis, Divided Highways: Building the Interstate Highways, Transforming

American Life (New York: Penguin, 1997).

4

National Bureau of Economic Research, Political Processes and the Common Pool

Problem: The Federal Highway Trust Fund (Cambridge, MA.: June 2000).

Page 8 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

which they financed through tolls.

5

The first of these highways, the

Pennsylvania Turnpike, was completed in 1940. During this time, about 30

states considered building toll roads, given the success of Pennsylvania. In

1943, Congress passed an amendment to the Federal Highway Act,

directing the Commissioner of Public Roads to conduct a survey for an

express highway system and report the results to the President and

Congress. However, there was no determination as to how such a system

would be funded. President Eisenhower supported a toll system financed

with bonds to be paid back with toll revenues until the bonds were paid off,

at which time the tolls would be removed. A committee appointed by

President Eisenhower also recommended a highway program financed

with bonds, but proposed that federal fuel tax revenues, instead of tolls, be

used to pay back the bonds. Ultimately, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of

1956 authorized the creation of a Highway Trust Fund to collect federal fuel

tax revenues and finance the construction of the Interstate Highway

System on a pay-as-you-go basis. The act prohibited tolling on interstate

highways and all federally assisted highways; as a consequence, states built

few new toll roads while the Interstate Highway System was under

construction. However, many of the toll roads built before 1956 were

eventually incorporated into the Interstate Highway System, and tolling on

these roads was allowed to continue. Tolling was also allowed, on a case-

by-case basis under very specific conditions and with a limited federal

funding share, for interstate bridges and tunnels.

During the 1990s, as interstate construction wound down, states again

began considering and implementing tolling. At the same time, some of the

federal restrictions on the use of federal funds for tolling began to ease.

The Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA)

liberalized some of the long-standing federal restrictions on tolling by

permitting tolling for the construction, reconstruction, or rehabilitation of

federally assisted non-Interstate roadways and by raising the federal share

on interstate bridges and tunnels to equal the share provided for other

federal-aid highway projects. The 1998 Transportation Equity Act for the

21st Century (TEA-21) established a new pilot program to allow the

conversion of a free interstate highway, bridge, or tunnel to a toll facility if

needed reconstruction or rehabilitation was possible only with the

5

Lewis, Divided Highways.

Page 9 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

collection of tolls.

6

The Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient

Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU), enacted in

2005, continued all of the previously established toll programs and added

new programs. The federal tolling-related programs that have been

authorized in surface transportation legislation are shown in table 1.

Table 1: Tolling-Related Programs Authorized in Surface Transportation Legislation

Source: FHWA.

SAFETEA-LU also created a National Surface Transportation

Infrastructure Financing Commission to consider revenue sources

available to all levels of government, particularly Highway Trust Fund

revenues, and to consider new approaches to generating revenues for

financing highways. The commission’s objective is to develop a report

recommending policies to achieve revenues for the Highway Trust Fund

that will meet future needs. The commission is required to produce a final

report within 2 years of its first meeting.

In addition to SAFETEA-LU’s new tolling provisions and enhancements to

existing programs, FHWA offers an innovative credit assistance program,

6

Federal Highway Administration, Federal-Aid Highway Toll Facilities (Washington, D.C.:

June 16, 2005).

Program Purpose

Value Pricing Pilot Program Authorized in ISTEA in 1991, this program is a pilot program for local transportation

programs to determine the potential of different value pricing approaches to manage

congestion, including projects that would use tolls on highway facilities.

Interstate System Reconstruction and

Rehabilitation Toll Pilot Program

Authorized in TEA-21 in 1998, this program allows tolls on three pilot projects in

different states to reconstruct an existing interstate facility.

Express Lanes Demonstration Program Authorized in SAFETEA-LU in 2005, this program allows 15 demonstration projects to

use tolling on interstate highways to manage high congestion levels, reduce emissions

to meet specific Clean Air Act requirements, or finance additional Interstate lanes to

reduce congestion.

High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Facilities Authorized in SAFETEA-LU in 2005, this program permits states to charge tolls to

vehicles that do not meet occupancy requirements to use an HOV lane even if the lane

is on an interstate facility.

Interstate System Construction Toll Pilot

Program

Authorized in SAFETEA-LU in 2005, this program permits tolls on three pilot projects

by a state or compact of states to construct new interstate system highways.

Section 129 of title 23, United States Code Section 129 authorizes federal participation in specific toll activities that are otherwise

generally prohibited under Section 301, also from title 23.

Page 10 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

which can be used to develop toll roads, and an experimental program,

which can be used to test innovative toll road development procedures.

The Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act of 1998

(TIFIA) permits FHWA to offer three kinds of credit assistance for

nationally or regionally significant surface transportation projects: direct

loans, loan guarantees, and lines of credit. Because TIFIA provides credit

assistance rather than grants, states are likely to use it for infrastructure

projects that can generate their own revenues through user charges, such

as tolls or other dedicated funding sources. TIFIA credit assistance is

aimed at advancing the completion of large, capital intensive projects—

such as toll roads—that otherwise might be delayed or not built at all

because of their size and complexity and the financial market’s uncertainty

over the timing of revenues from a project. The main goal of TIFIA is to

leverage federal funds by attracting substantial private and other

nonfederal investment in projects. FHWA has also encouraged

experimental projects through the Special Experimental Projects 15 (SEP-

15) program, which is intended to encourage the formation of public-

private partnerships for projects by providing additional flexibility for

states interested in experimenting with innovative ways to develop

projects, according to FHWA officials. SEP-15 allows innovation and

flexibility in contracting, compliance with environmental requirements,

right-of-way acquisition, and project finance.

In addition, the Department of Transportation’s Office of Transportation

Policy is proposing a pilot program—the Open Roads Pilot Program—to

explore alternatives to the motor fuel tax. Under this pilot, the Office of

Transportation Policy is proposing to make funds available to up to five

states to demonstrate on a large scale the viability and effectiveness of

financing alternatives to the motor fuel tax. Goals of the program would be

to: (1) demonstrate whether or not there are viable alternatives to the

motor fuel tax that will provide necessary investment resources while

simultaneously improving system performance and reducing congestion,

(2) identify successful motor fuel tax substitutes that have widespread

applicability to other states, and (3) provide a possible framework for

future federal reauthorization proposals.

Page 11 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

Tolling Has Promise as

an Approach for

Enhancing Mobility

and for Financing

Transportation

As congestion increases and concerns about the sustainability of

traditional roadway financing sources grow, tolling has promise as an

approach to enhance mobility and to finance transportation. Tolls that are

set to vary with the level of congestion can potentially lead to a reduction in

congestion and demand for roads. Such tolls can create additional

incentives for drivers to avoid driving alone in congested conditions when

making their driving decisions. In response, drivers may choose to share

rides, use public transportation, travel at less congested (generally off-

peak) times, or travel on less congested routes, if available, to reduce their

toll payments. Tolling is also consistent with the important user pays

principle, can potentially better target spending for new and expanded

capacity, and can potentially enhance private-sector participation and

investment in major highway projects. Tolling’s promise is particularly

important in light of long-term fiscal challenges and pressures on the

federal budget.

In the Face of Increasing

Congestion, Tolling Holds

Promise as an Approach to

Enhance Mobility

Tolling can be used to potentially enhance mobility by managing

congestion, which is already substantial in many urban areas. Congestion

impedes both passenger and freight mobility and ultimately, the nation’s

economic vitality, which depends in large part on an efficient

transportation system. Highway congestion for passenger and commercial

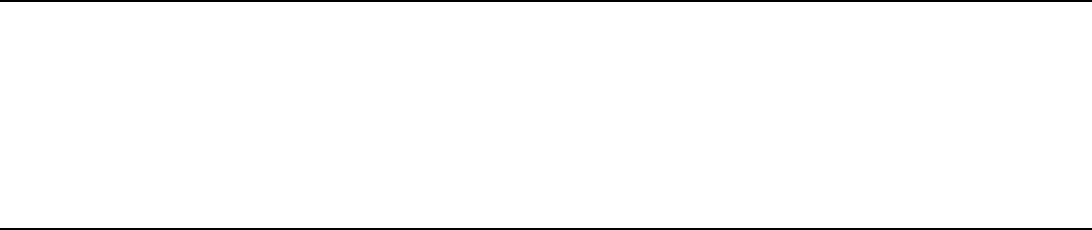

vehicles traveling during peak driving periods doubled from 1982 through

2000. According to the Texas Transportation Institute, drivers in 85 urban

areas experienced 3.7 billion hours of delay and wasted 2.3 billion gallons

of fuel in 2003 because of traffic congestion.

7

The Texas Transportation

Institute estimated that the cost of congestion was $63.1 billion (in 2003

dollars), a fivefold increase over two decades after adjusting for inflation.

On average, drivers in urban areas lost 47 hours on the road in 2003, nearly

triple the delay travelers experienced on average in 1982. During this same

period, congestion grew in urban areas of every size; however, very large

metropolitan areas with populations of more than 3 million were most

affected. (See fig. 2 for examples of congestion growth in selected urban

areas.) Freight traffic—which has doubled since 1980 and in some

locations constitutes 30 percent of interstate system traffic—added to this

congestion at a faster rate than passenger traffic, and FHWA projects

7

Texas Transportation Institute, 2005 Urban Mobility Report (College Station, TX: May

2005).

Page 12 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

continued growth, estimating that the volume of freight traffic on U.S.

roads will increase 70 percent by 2020.

Figure 2: Annual Delay per Traveler in Selected Urban Areas, 1982, 1993, and 2003

A number of factors, as follows, are converging to further exacerbate

highway congestion:

• Most population growth in the nation occurs in already congested

metropolitan areas. In 2000, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that 79

percent of 281 million U.S. residents lived in metropolitan areas.

Nationwide, the population is expected to increase by 54 million by

2020, and most of that growth is expected in metropolitan areas.

• Vehicle registrations are steadily increasing. In 2003, vehicle

registrations nationwide stood at 230 million, a 17 percent increase in

just 10 years.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Colorado Springs,

Colorado

Austin, TexasRiverside-San

Bernardino, California

Atlanta, Georgia

Hours of delay

Urban areas

Source: GAO analysis of Texas A&M University data.

1982

1993

2003

Page 13 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

• Road usage, as measured by vehicle miles traveled (VMT), grew at a

steady annual rate of 2.8 percent from 1980 through 2003. For the 10-

year period between 1994 and 2003, the total increase in VMT was 22

percent.

• Road construction has increased at a slower pace than population

growth, vehicle registrations, and road usage. For example, from 1980 to

2000, VMT increased by 80 percent while urban lane miles increased 37

percent.

In light of this increasing congestion, a tolling structure that includes

congestion pricing can potentially reduce congestion and the demand for

roads during peak hours. Through congestion pricing, tolls can be set to

vary during congested periods to maintain a predetermined level of service.

One potential effect of this pricing structure is that the price that a driver

pays for such a trip, including the toll, may be equal to or close to the total

cost of that trip, including the external costs that drivers impose on others,

such as increased travel time, pollution, and noise.

8

Such tolls create

financial incentives for drivers to consider these costs when making their

driving decisions. In response, drivers may choose to share rides, use

transit, travel at less congested (generally off-peak) times, or travel on less

congested routes to reduce their toll payments.

9

Such choices can

potentially reduce congestion and the demand for road space at peak

periods, thus potentially allowing the capacity of existing roadways to

accommodate demand with fewer delays.

Actual experience with congestion pricing is still fairly limited in the United

States, with only five states operating such facilities and six states planning

8

As we reported in 2003, economists generally believe that charging surcharges or tolls

during congested periods can enhance economic efficiency by making them take into

account the external costs they impose on others in deciding when, where, and how to

travel. In congested situations, external costs are substantial and include increased travel

time, pollution, and noise. The goal of efficient pricing on public roads, for example, would

be to set tolls for travel during congested periods that would make the price (including the

toll) that a driver pays for such a trip equal or close to the total cost of that trip, including

external costs. GAO, Reducing Congestion: Congestion Pricing Has Promise for

Improving Use of Transportation Infrastructure, GAO-03-735T (Washington, D.C.: May 6,

2003). For further discussion of the research on congestion pricing, see Transportation

Research Board, Curbing Gridlock: Peak-Period Fees to Relieve Traffic Congestion

(Washington, D.C.: January 1994).

9

GAO-03-735T.

Page 14 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

facilities.

10

Some results show that where variable tolls are implemented,

changes in toll prices affect demand and, therefore, levels of congestion.

For example, on State Route 91 in California, the willingness of people to

use the Express Lanes has been shown to be directly related to the price of

tolls. A study by Cal Poly State University for the California DOT estimated

that a 10 percent increase in tolls would reduce traffic by 7 percent to 7.5

percent, while a 100 percent increase in tolls would reduce traffic by about

55 percent.

11

By adjusting the price of tolls, the flow of traffic can be

maintained in the toll lanes so that congestion remains at manageable

levels. In the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, a Minnesota DOT study of a

proposed system of variable priced HOT lanes called MnPASS estimated

that, over time, average speeds and vehicle mileage would increase, while

vehicle hours traveled would decrease.

12

By 2010, with tolled express lanes

and free HOV lanes, the daily vehicle mileage on the entire system is

projected to be 3.6 million compared with 3.2 million if the highways are

not tolled. Average overall speed on the system is expected to be 47 mph

compared with 42.8 mph if the system is not implemented. Finally,

congestion pricing has been in use internationally as well.

Canada, Great

Britain, Norway, Singapore, and South Korea all have roadways that are

tolled to manage demand and reduce congestion. For example, in 1996,

South Korea implemented congestion tolls on two main tunnels. Traffic

volume decreased by 20 percent in the first 2 years of operation, and

average traffic speed increased by 10 kilometers per hour.

Although congestion pricing was dismissed by some decision makers in the

past partly because motorists queuing at toll booths to pay tolls created

congestion and delays, advances in automated toll collection have greatly

reduced the cost and inconvenience of toll collection. Today, nearly every

major toll facility provides for electronic toll collection, greatly reducing

the cost and inconvenience of toll collection. With electronic toll

collection, toll fee collection for using a facility can be done at near

highway cruising speed because cars do not have to stop at toll plazas.

However, as we reported, there are no widely accepted standards for

10

According to our survey of state DOTs, the five states currently operating facilities are

California, Minnesota, New York, Texas, and Virginia. States that are planning facilities

include California, Colorado, Maryland, Virginia, Texas, and Washington.

11

Cal Poly State University, Continuation Study to Evaluate the Impacts of the SR 91 Value-

Priced Express Lanes Final Report (San Luis Obispo, CA: December 2000).

12

Cambridge Systematics for Minnesota Department of Transportation, MnPASS System

Study, Final Report (Cambridge, MA: Apr. 7, 2005).

Page 15 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

electronic toll systems, which could become a barrier to promoting the

needed interoperability between toll systems.

13

Tolling Holds Promise as an

Approach to Finance

Transportation Projects

Tolling holds promise to improve investment decisions and raise revenues

in the face of growing concerns about the sustainability of traditional

financing sources for surface transportation. For many years, federal and

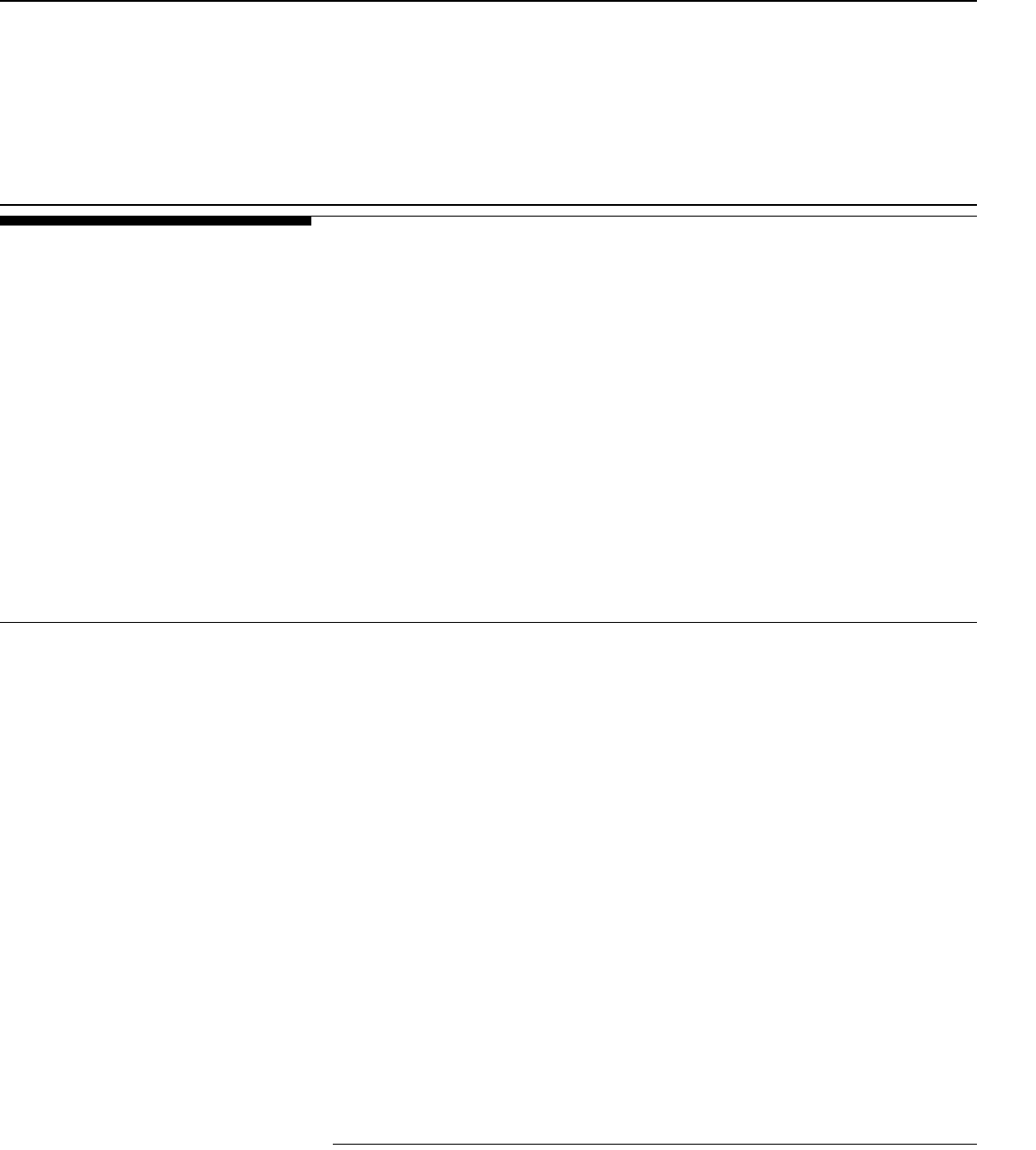

state motor fuel taxes have been the mainstay of state highway revenue. In

the last few years, however, federal and motor fuel tax rates have not kept

up with inflation. Between 1995 and 2004, total highway revenues for states

grew an average of 3.6 percent per year, with average annual increases of

4.9 percent for federal grants and 3 percent for revenues from state

sources, according to FHWA data. However, these increases were smaller

than increases in the cost of materials and labor for road construction and

are not sufficient to keep pace with the robust levels of growth in highway

spending many transportation advocates believe is needed.

14

The federal

motor fuel tax rate of 18.4 cents per gallon has not been increased since

1993, and thus the purchasing power of fuel tax revenues has been steadily

eroded by inflation. Although the Highway Trust Fund

15

was reauthorized

in 1998 and 2005, no serious consideration was given to raising fuel tax

rates. Most states faced a similar degradation of the value of their state

motor fuel tax revenues—although 28 states raised their motor fuel tax

rates between 1993 and 2003, only three states raised their rates enough to

keep pace with inflation. State gasoline tax rates range from 7.5 cents per

gallon in Georgia to 28.5 cents in Wisconsin. Seven states have motor fuel

tax rates that vary with the price of fuel or the inflation rate—including one

state that repealed the linkage of its fuel tax rate to the inflation rate

effective in 2007. Figure 3 shows the decline in the purchasing power in

13

GAO, Highway Congestion: Intelligent Transportation Systems' Promise for Managing

Congestion Falls Short, and DOT Could Better Facilitate Their Strategic Use, GAO-05-943

(Washington, D.C.: Sept. 14, 2005).

14

Brookings Institution, Improving Efficiency and Equity in Transportation Finance

(Washington, D.C.: April 2003); Eric Kelderman, Road Funding Takes a Toll on States

(Washington, D.C.: Feb. 17, 2006); and Transportation Research Board, “Special Report 285:

The Fuel Tax and Alternatives for Transportation Funding” (Washington, D.C.: 2005).

15

Highway user tax receipts, such as motor fuel taxes, are deposited into the Highway Trust

Fund and distributed to the states according to formulas based on vehicle miles traveled,

motor fuel used on highways, and other factors, which are specified in law. GAO, Surface

and Maritime Transportation: Developing Strategies for Enhancing Mobility: A National

Challenge, GAO-02-775 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 30, 2002).

Page 16 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

real terms of revenues generated by federal and state motor fuel tax rates

since 1990.

Figure 3: Combined Federal and Average State Motor Fuel Tax Rates

Note: Tax rates are in 2004 inflation-adjusted dollars. Totals for 1992, 1995, 1996, 2000, and 2003 are

rounded. State average gas tax rate is a “weighted average.”

Even if federal and state motor fuel tax rates were to keep pace with

inflation, the growing use of fuel-efficient vehicles and alternative-fueled

vehicles would, in the longer term, further diminish fuel tax revenues.

Although all highway motorists pay fuel taxes, those who drive hybrid-

powered or other alternative-fueled vehicles consume less fuel per mile

than those who drive gas-only vehicles. As a result, these motorists pay less

fuel tax per mile traveled. According to the U.S. Energy Information

Agency, hybrid vehicle sales grew twentyfold between 2000 and 2005 and

Sources: GAO analysis of DOT and FHWA data.

38.20

19.98

18.21

44.92

22.21

22.71

44.41

22.17

22.24

43.72

21.92

21.79

42.78

21.50

21.27

42.39

21.35

21.04

42.35

21.54

20.81

42.76

22.25

20.51

41.12

21.05

20.07

41.09

21.49

19.60

39.24

19.97

19.27

38.52

19.63

18.88

37.50

19.10

18.40

37.82

18.97

18.85

39.97

22.16

17.80

0

10

20

30

40

50

200420032002200120001999199819971996199519941993199219911990

Federal gas tax rate

State average

gas tax rate

Total gas tax rate

Cents per gallon

Federal motor fuels tax

Average state motor fuels tax

Page 17 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

will grow to 1.5 million vehicles annually by 2025. In the past five years,

hybrid vehicle sales grew in the United States twentyfold, from 9,400 in

2000 to over 200,000 in 2005. Moreover, the U.S. Energy Information

Agency projects that hybrid vehicle sales will grow to 1.5 million annually

by 2025.

Sales of alternative-fueled vehicles, such as alcohol-flexible-fueled

vehicles, are projected to increase to 1.3 million in 2030, with electric and

fuel cell technologies projected to increase by 2030 as well.

As concerns about the sustainability of traditional roadway financing

sources grow, tolling can potentially target investment decisions by

adhering to the user pays-principle. National roadway policy has long

incorporated the user pays concept, under which the costs of building and

maintaining roadways are paid by roadway users, generally in the form of

excise taxes on motor fuels and other taxes on inputs into driving, such as

taxes on tires or fees for registering vehicles or obtaining operator licenses.

This method of financing is consistent with one measure of equity that

economists use in assessing the financing of public goods and services, the

benefit principle, which measures equity according to the degree that

readily identifiable beneficiaries bear the cost. As a result, the user pays

concept is widely recognized as a critical anchor for transportation policy.

16

Increasingly, however, decision makers have looked to other revenue

sources—such as income, property, and sales tax revenues—to finance

roads. Using these taxes results in some sacrifice of the benefit principle

because there is a much weaker link to the benefits of roadway

expenditures for those taxes than there is for fuel taxes.

17

Tolling, however,

is more consistent with user pay principles because tolling a particular

road and using the toll revenues collected to build and maintain that road

more closely link the costs with the distribution of the benefits that users

derive from it. Motor vehicle fuel taxes can provide a rough link between

costs and benefits but do not take into account the wide variation in costs

required to provide different types of facilities (i.e., roads, bridges, tunnels,

interchanges) some of which can be very costly.

Tolling can also potentially lead to more targeted, rational, and efficient

investment by state and local governments. Roadway investment can be

16

Texas Transportation Institute, 2005 Urban Mobility Report (College Station, TX: May

2005).

17

Brookings Institution, Improving Efficiency and Equity in Transportation Finance

(Washington, D.C.: April 2003).

Page 18 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

more efficient when it is financed by tolls because the users who benefit

will likely support additional investment to build new capacity or enhance

existing capacity only when they believe the benefits exceed the costs.

When costs are borne by nonusers, the beneficiaries may demand that

resources be invested beyond the economically justifiable level. Tolling can

also provide the potential for more rational investment because, in contrast

to most grant-financed projects, toll project construction is typically

financed by bonds sold and backed by future toll revenues, and projects

must pass the test of market viability and meet goals demanded by

investors. However, even with this test there is no guarantee that projects

will always be viable.

18

A tolling structure that includes congestion pricing can also help guide

capital investment decisions for new facilities. As congestion increases,

tolls also increase and such increases (sometimes referred to as

“congestion surcharges”) signal increased demand for physical capacity,

indicating where capital investments to increase capacity would be most

valuable. At the same time, congestion surcharges would provide a ready

source of revenue for local, state, and federal governments, as well as for

transportation facility operators in order to help fund these investments in

new capacity that, in turn, can reduce delays. Over time, this form of

pricing can potentially influence land-use plans and the prevalence of

telecommuting and flexible workplaces, particularly in heavily congested

corridors where external costs are substantial and congestion surcharges

would be relatively high.

Tolling can also be used as a tool for leveraging increased private-sector

participation and investment. In March 2004, we reported that three

states—California, Virginia, and South Carolina—had pursued private-

sector investment and participation in major highway projects. Since that

time, Virginia has pursued additional projects, and Texas has contracted

with a private entity to participate and invest in a major highway project.

19

Tolling can be used to enhance private participation because it provides a

mechanism for the private sector to earn the return on investment it

18

As we reported in 2004, three of the four toll road projects that were built with private

participation and investment and were open to traffic at that time were not financially

successful. See GAO, Highway and Transit: Private Sector Sponsorship of and Investment

in Major Projects Has Been Limited, GAO-04-419 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 25, 2004).

19

In addition, the City of Chicago and the State of Indiana have contracted with private

entities to operate existing facilities.

Page 19 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

requires to participate. Involving the private sector allows state and local

governments to build projects sooner, conserve public funding from

highway capital improvement programs for other projects, and limit their

exposure to the risks associated with acquiring debt.

20

In the Long Term, Tolling

Holds Promise for

Addressing the

Transportation Challenges

Ahead

Federal and state policymakers have begun looking toward future options

for long-term highway financing. For example, SAFETEA-LU established

the National Surface Transportation Infrastructure Financing Commission

to study prospective Highway Trust Fund revenues and assess alternative

approaches to generating revenues for the Fund. SAFETEA-LU also

authorized a study, to be performed by the Public Policy Center of the

University of Iowa, to test an approach to assessing highway use fees based

on actual mileage driven. This approach would use an onboard computer to

measure the miles driven by a specific vehicle on specific types of

highways. A few states have also begun looking toward the long-term

financing options. Oregon, the first state to enact a motor fuel tax, is

sponsoring a study on the technical feasibility of replacing the gas tax with

a per-mile fee. During 2006, volunteers will have onboard mileage-counting

equipment added to their vehicles and will, for one year, pay a road user fee

equal to 1.2 cents a mile instead of paying the state’s motor fuel tax.

But beyond the questions of financing and financing sources, broader

issues and challenges exist. As the baby boom generation ages, mandatory

federal commitments to health and retirement programs will consume an

ever-increasing share of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) and

federal budgetary resources, placing severe pressures on all discretionary

programs, including those that fund defense, education, and transportation.

Our simulations show that by 2040, revenues to the federal government

might barely cover interest on the debt—leaving no money for either

mandatory or discretionary programs—and that balancing the budget

could require cutting federal spending by as much as 60 percent, raising

taxes by up to 2 ½ times their current level, or some combination of the

two. As we have reported, this pending fiscal crisis requires a fundamental

reexamination of all federal programs, including those for highways. This

reexamination should raise questions such as whether a federal role is still

needed, whether program funding can be better linked to performance, and

whether program constructs are ultimately sustainable. It is in this context

20

GAO-04-419.

Page 20 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

that tolling has promise for addressing the challenges ahead. In particular,

we have suggested that a reexamination of the federal role in highways

should include asking whether the federal government should even

continue to provide financing through grants or whether, instead, it should

develop and expand alternative mechanisms that would better promote

efficient investments in, and use of, infrastructure and better capture

revenue from users.

States’ Use of Tolling to

Address Funding

Shortfalls, Finance

New Capacity, and

Manage Congestion Is

Expanding; but for

Some States, Tolling Is

Not Viewed as Feasible

According to our survey of state transportation officials, there are toll road

facilities in 24 states and plans to build toll road facilities in 7 other states.

Tolling grew in the 1940s and 1950s, but after a period of slower growth,

states’ tolling began to expand again in the 1990s. The 5 states that began

tolling after 1990 are currently planning additional toll roads. Officials in

states that have toll roads or are planning toll roads indicated that their

primary reasons for using or considering the use of a tolling approach were

to address transportation shortfalls, finance new capacity, and manage

congestion. Transportation officials in some states, however, told us that

tolling is not now seen as feasible because there is little need for new tolled

capacity, tolling revenues would be insufficient, and they would face public

and political opposition to tolling.

Nearly Half of the States

Have Operating Toll Roads,

and More States Are

Planning Toll Roads

Currently, there are toll road facilities in 24 states throughout the United

States, and there are plans to build toll road facilities in 7 additional states.

Figure 4 shows the states that have at least one existing toll road, according

to our survey of transportation officials from all 50 states and the District of

Columbia and our review of FHWA toll-related programs. (See app. III for

the survey questions.)

Page 21 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

Figure 4: Existing Toll Road Facilities

Tolling grew in the 1950s, slowed for several decades, and again began to

expand rapidly in the 1990s. Five states—California, Colorado, Minnesota,

South Carolina, and Utah—opened their first toll roads from 1990 to 2006

and, according to our survey of state transportation officials, all five are

currently planning, or in some stage of building, at least one new toll road.

Large states that have recently built toll roads, such as California, Florida,

and Texas, are also moving ahead with plans to build and expand systems

of tolls. In Texas, for example, the DOT’s Turnpike Authority Division is

developing a proposed multiuse, statewide network of transportation

Source: GAO.

Existing toll road facilities

Not surveyed

No existing toll road facilities

Pa.

Ore.

Nev.

Idaho

Mont.

Wyo.

Utah

Ariz.

N.Mex.

Colo.

N.Dak.

S.Dak.

Nebr.

Tex.

Kans.

Okla.

Minn.

Iowa

Mo.

Ark.

La.

Ill.

Miss.

Ind.

Ky.

Tenn.

Ala.

Fla.

Ga.

S.C.

N.C.

Va.

Ohio

N.H.

Mass.

R.I. ( )

Mich.

Calif.

Wash.

Wis.

N.Y.

Maine

Vt.

W.Va.

Alaska

Hawaii

Conn. ( )

N.J. ( )

Del. ( )

Md. ( )

D.C. ( )

Page 22 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

routes that will incorporate existing and new highways called the TTC,

21

while three other regional toll authorities

22

in Austin, Dallas, and Houston

are also planning toll roads. In California, a state legislative initiative in

1989 led to the development of toll roads in Orange County, including the

State Route 91 Express Lanes and State Route 125 in San Diego. And in

Florida, the DOT-run Florida Turnpike Enterprise operates nine tolled

facilities that include almost 500 miles of toll roads and is studying the

feasibility of implementing tolling to manage congestion on other facilities,

including Interstate 95 in Miami-Dade County.

According to our survey of state transportation officials and our review of

state applications to FHWA tolling pilot programs, a total of 23 states have

plans to build toll road facilities.

23

(Fig. 5 summarizes the status of states’

plans for highway tolling.) Eleven of these states have received the

required environmental clearances and have projects that are under design

or in construction. The remaining 12 states do not have projects that have

proceeded this far, but do have plans to build toll road facilities, according

to their respective state transportation officials. Of these 23 states,

• 16 have existing toll roads and are planning additional toll roads,

24

and

21

Plans for TTC include TTC 35, which is projected to parallel Interstate 35 and Interstate 69.

22

The Central Texas Regional Mobility Authority in the Austin area, the Harris County Toll

Road Authority in the Houston area, and the North Texas Tollway Authority in the Dallas

area.

23

In our count, we included affirmative responses to our survey questions regarding (1)

planned toll road facilities that were in design/right-of-way or construction and (2) plans for

toll road facilities that were not yet in design or construction but for which an

environmental review and Record of Decision had been completed. We compared the

responses to these questions with information obtained from our interviews with state DOT

officials and from state applications to FHWA’s tolling programs, including the Interstate

System Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Pilot Program and the Value Pricing Pilot. In four

instances, data from these sources were inconsistent. We contacted DOT officials in these

states to resolve these inconsistencies and adjusted the survey results accordingly.

24

The 16 states include California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana,

Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and West

Virginia.

Page 23 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

• 7 are planning their first toll roads.

25

Figure 5: Planned Toll Road Facilities

25

The 7 states include Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oregon,

and Washington.

Source: GAO.

Pa.

Ore.

Nev.

Idaho

Mont.

Wyo.

Utah

Ariz.

N.Mex.

Colo.

N.Dak.

S.Dak.

Nebr.

Tex.

Kans.

Okla.

Minn.

Iowa

Mo.

Ark.

Ill.

Miss.

Ind.

Ky.

Tenn.

Ala.

Fla.

Ga.

S.C.

N.C.

Va.

Ohio

N.H.

Mass.

Mich.

Calif.

Wash.

Wis.

N.Y.

Maine

Vt.

W.Va.

Alaska

Hawaii

Toll roads in design or under construction

Planned toll roads

No planned toll roads

R.I. ( )

Conn. ( )

N.J. ( )

Del. ( )

Md. ( )

D.C. ( )

Not surveyed

La.

Page 24 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

Some States Use Tolling to

Address Funding Shortfalls,

Finance New Capacity, and

Manage Congestion; Other

States Find Tolling Not

Feasible or Have Made

Other Choices

Officials in most states planning toll roads indicated that the primary

reasons for considering a tolling approach were to address what state

officials characterized as transportation funding shortfalls, to finance and

build new capacity, and to manage congestion. States that are not planning

to build toll roads have found that tolling is not feasible or have made other

choices.

States Use Tolling to Address

Transportation Funding

Shortfalls

Transportation officials indicated that one of the primary reasons for using

or considering a tolling approach was to respond to what the officials

described as shortfalls in transportation funding. In Georgia, for example,

an official told us that tolling has become a strategy because there is a

significant gap in transportation funding, and the motor fuel tax rate is the

lowest in the country, 7.5 cents per gallon. In North Carolina, where the

North Carolina Turnpike Authority was established in 2002, an official told

us that traditional funding is not adequate to address transportation needs.

North Carolina has estimated that, over the next 25 years, it will need $85

billion in new transportation projects to accommodate the state’s growth.

With a projected shortfall of $30 billion and what the official described as a

lack of political will to increase motor fuel tax rates, the state has adopted

tolling as one strategy to address transportation needs. In Utah, state

transportation officials have estimated a $16.5 billion shortfall through

2030 in funding for highway projects and are considering tolling, along with

other funding alternatives. Finally, an official told us that, in spite of a

motor fuel tax rate increase in 2003 and a $200 million bonding program,

Indiana has a 10-year, $2.8 billion shortfall in highway funding and is

viewing tolling as one financing tool to close the gap. The Indiana DOT has

operated the Interstate 80/Interstate 90 Indiana Toll Road for 50 years and

would like to apply that experience in operating toll roads to new roads.

In other states, transportation officials conducted financial assessments on

specific highway projects and determined that, to complete the projects,

tolling would be required as a source of revenue. For example, in Missouri,

a funding analysis performed by the Missouri DOT found that the estimated

construction costs for the Interstate 70 reconstruction exceed the available

federal, state, and local funding sources, and the project cannot be

advanced without tolling or other revenue increases. Missouri DOT

estimates that the Interstate 70 reconstruction project will cost between

$2.7 and $3.2 billion and that, with a current funding shortfall of $1 billion

Page 25 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

to $2 billion annually, tolling is being actively considered to close that gap.

26

Likewise, studies by the Texas DOT determined that tolling would be

required on particular highway projects. For example, reconstructing a

23-mile portion of Interstate 10 near Houston was estimated to cost $1.99

billion. Available federal, state, and local funds amounted to $1.75 billion, a

shortfall of $305.2 million. The Harris County Toll Road Authority invested

$238 million for the right to operate tolled lanes within the facility. In

addition, the Texas Transportation Commission, which oversees the state

DOT, ordered that all new controlled-access highways should be

considered as potential toll projects that will undergo toll feasibility

studies. The commission views tolling as a tool that can help stretch limited

state highway dollars further so that transportation needs can be met.

Moreover, states are looking for whatever financial relief tolling can

provide. In some states, tolling is being considered, even though toll

revenues are expected to only partially cover the costs of particular

projects. In Mississippi, for example, the state DOT indicated that tolling

may be advanced if toll revenues cover 25 percent to 50 percent of a

facility’s cost. In Arkansas, tolling is being considered if toll revenues fund

as little as 20 percent of the initial construction costs, provided tolls pay for

operations and maintenance.

To identify state characteristics that are linked with state decisions to toll,

we performed a correlation analysis to examine the relationship between

those decisions and various state demographic and financial

characteristics. Although certain characteristics in a state’s finances and

tax policies might be related to financial need, our correlation analysis

found only limited relationships between various state financial and

demographic measures and states’ decisions to toll or not to toll. For

example, although we found a slight inverse relationship between a state’s

decision to toll and the level of its motor fuel taxes, this relationship is not

strong enough to conclude that states planning toll roads are more likely to

be the ones with lower motor fuel tax rates than other states. However, we

found that both the size of the state, whether measured by population or by

VMT, and whether it is growing rapidly, again measured by population or

VMT growth, are directly related to states’ decisions to toll. (For more

information on the results of our correlation analysis, see app. II.)

26

The Interstate 70 reconstruction project has been approved as one of the slots in the

Interstate System Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Pilot Program. Federal approval is

necessary for states to toll interstate highways.

Page 26 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

States Use Tolling to Finance

New Capacity

According to transportation officials, states are using or considering a

tolling approach to finance new capacity that cannot otherwise be funded

under current and projected transportation funding scenarios. Such new

capacity may be in the form of new highways or new lanes on existing

highways. For example, in Colorado, the state DOT is studying the

investment of $3 billion in increased highway capacity, with 10 percent, or

$300 million of the investment, coming from federal, state, and local

governments and the remainder coming from tolls. With a $48 billion

shortfall projected through 2030 and the percentage of congested lane-

miles projected to increase by 161 percent, tolling is being considered.

Projections by the state DOT in Colorado suggest that revenues are

sufficient to allow for only spot improvements on a few transportation

corridors over the next 25 years and, without tolling, none can undergo a

major upgrade, and new capacity cannot be added.

Some states are using tolling to supplement their traditional motor fuel tax

transportation funding through private-sector involvement and investment.

Tolling is being used as a means to gain access to private equity and to shift

the investment risk, in part, to the private sector. Currently, 18 states have

some form of public-private partnership (PPP) legislation, allowing for

innovative contracting with the private sector. Many of the 18 states have

PPP programs that were established to allow for toll concession

agreements to finance highway projects. For example, Oregon and Texas

are specifically looking to attract private investment as a new source of

financing. The TTC, as shown in figure 6,

27

is being financed, in part,

through a series of PPPs. The Texas DOT has contracted with Cintra-

Zachry to develop a long-term development plan for the corridor, which

includes the potential to construct and operate the first 316-mile portion of

TTC 35, from Dallas to San Antonio. Cintra-Zachry has pledged an

investment of $6 billion and a payment of $1.2 billion for the right to build,

operate, and collect tolls for up to 50 years on the initial segment of TTC 35.

In Oregon, the Office of Innovative Partnerships and Alternative Funding—

an Oregon DOT office empowered to pursue alternative funding, including

27

This is a conceptual illustration that shows a complete build out. TTC will be phased in as

transportation demand warrants and private sector funding makes it feasible. Since it will

be developed based on transportation demand, it is conceivable that not all elements will be

developed concurrently and may not be located adjacent to each other as shown in the

illustration. Depending on environmental and engineering factors, transportation modes

may diverge. Input from the ongoing public meetings will help determine plans for the TTC.

Two projects are being pursued by Texas DOT, TTC 35 and TTC 69. Both are under

environmental review, and neither right-of-way acquisition nor construction has been

federally approved.

Page 27 GAO-06-554 Highway Finance

private investment through tolling—has received proposals from the

Oregon Transportation Improvement Group, a consortium led by the

Macquarie Infrastructure Group, to complete two tolled facilities in the

Portland area. In both Texas and Oregon, the projects were approved under

SEP-15, which enabled the two states to waive certain federal requirements

and to negotiate with the project developers before awarding contracts.