Article

Integration of Primary and Resale Platforms

Tianxin Zou and Baojun Jiang

Abstract

Consumers can buy concert tickets from primary platforms (e.g., Ticketmaster) or from consumer-to-consumer resale platforms

(e.g., StubHub). Recently, Ticketmaster has entered and been trying to control the resale market by prohibiting consumers from

reselling on competing resale platforms. Several states in the United States have passed or are discussing laws requiring tickets to

be transferrable on any resale sites, worrying that platform integration—Ticketmaster controlling both the primary and the resale

platforms—will increase ticket service fees and harm musicians and consumers. This article establishes a game-theoretic

framework and shows that the opposite can happen: platform integration can lower the service fees in both markets, alleviat-

ing double marginalization in the primary market and benefiting the musician and consumers. Moreover, with platform integration,

the presence of a small number of scalpers can counterintuitively reduce the ticket price and benefit the musicians and consumers.

In addition, platform competition in the resale market may harm consumers. This article further shows that these insights apply in

other markets (e.g. used goods, peer-to-peer product-sharing markets) and provides suggestive empirical support for the the-

oretical results.

Keywords

antitrust, channel coordination, consumer welfare, event ticket, platform, regulation, resale, secondary market

Online supplement: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243720917352

In 2017, the U.S. concert-ticket industry reached over $3 bil-

lion in revenue, with more than 20 million consumers having

attended at least one concert.

1

Ticketmaster, with over 80% of

the U.S. market share, is the dominant primary platform for

concert ticke ts (Rob erts 2013). T icketmaster mainly profits

from the service fees paid by ticket buyers. For example, it

charged a $17.85 service fee for a $61 ticket of Justin Timber-

lake’s The Man of the Woods Tour at Madison Square Garden.

The peer-to-peer ticket resale market is also growing rapidly.

StubHub, with over 50% share of the U.S. ticket-resale market,

has seen a 30% growth rate in revenue in 2015 (Thomas 2016).

Over the past few years, Ticketmaster has expanded its

business from the primary market to the resale market. In

2008, it acquired TicketsNow, an online ticket resale platform,

for $265 million (Smith 2008). In 2013, Ticketmaster intro-

duced its own “Fan-to-Fan” resale system, Ticketmaster Resale

(formerly TMþ). Musicians can enroll in Ticketmaster Resale

to allow consumers to resell their tickets to other consumers on

Ticketmaster. For concerts with Ticketmaster Resale, the pri-

mary and resale ticket availabilities are shown on the same seat

map (for an example, see Figure 1). In 2014, Ticketmaster

received $900 million from ticket r esales (Ingham 2015).

Moreover, Ticketmaster has been trying to extend its de facto

monopoly in the primary market to the resale market by block-

ing other resale platforms. For example, after signing on as the

exclusive resale partner of the Golden State Warriors (GSW) in

2012, Ticketmas ter w arne d GSW season-ticket owners th at

their tickets would be revoked if resold outside Ticketmaster.

Consequently, StubHub saw an 80% decrease in resale trans-

actions of GSW season tickets (Dinzeo 20 15). Ticketmaster

also introduced the “Paperless Ticket” system (also known as

“Credit Card Entry”) for some events, which requires consu-

mers to show the credit card used to buy the ticket and a photo

ID to enter the concerts, making reselling through other resale

platforms very difficult for consumers.

2

Consumers can still

resell their paperless tickets through Ticketmaster because it

can change the ticketholder’s information in its own database.

Tianxin Zou is Assistant Professor of Marketing, Warrington College of

Baojun Jiang is Associate Professor of Marketing, Olin Business School,

1

See https://www.statista.com/outlook/264/109/event-tickets/united-

states#market-users.

2

See https://www.ticketmaster.com/mileycyrus/faq.html.

Journal of Marketing Research

2020, Vol. 57(4) 659-676

ª American Marketing Association 2020

Article reuse guidelines:

sagepub.com/journals-permissions

DOI: 10.1177/0022243720917352

journals.sagepub.com/home/mrj

The public reacted negatively to Ticketmaster’s anticompe-

titive practices. StubHub emailed its customers warning that

“companies ‘like Ticketmaster’ are moving to restrictive

paperless systems, which could kill the secondary market for

tickets” (Indiviglio 2011). StubHub also sued Ticketmaster and

GSW in 2015 for creating illegal market conditions, although

the lawsuit was later dismissed (Rovell 2015). The Paperless

Ticket system has also led to drastic disputes. For example, a

spokesman for Consumer Action, a consumer advocacy group,

argued that “[it] is wrong to deprive consumers of the right to

fairly sell, trade or give away the ticket” (Pender 2017). An

article in The Atlantic also blamed Ticketmaster for

“extend[ing] its near monopoly of ticketing to the secondary

market” (Indiviglio 2011). As of 2019, five U.S. states, includ-

ing Colorado ( Colorado Consumer Protection Act 2017), Con-

necticut (An Act Concerning the Sale of Entertainment Event

Tickets on the Secondary Market 2017), New York (NY Arts &

Cult Aff L §25.30 2015), Virginia (Ticket Resale Rights Act

2017), and Utah (Ticket Transferability Act 2019), have passed

legislations requiring ticket issuers to offer tickets that can be

resold on any resale sites. Ten other states, including Arizona

(AZ HB2560 2019), Florida (FL SB392 2012), Indiana (IN

HB1331 2020), Massachusetts (MA H1893 2011), Minnesota

(MN SF425 2011), Missouri (MO HB255 2017), New Jersey

(NJ S1728 2018), North Carolina (NC H308 2011), Rhode

Island (RI H5362 2019), and Texas (TX HB3041 2013), have

previously discussed or are currently considering similar bills.

The Virginia legislation was sponsored by state delegate David

B. Albo, who lost $400 because he was unable to resell his two

paperless tickets for Iron Maiden to his friends. Albo said that

the legislation “would help consumers, given Ticketmaster’s

near-monopoly over big-venue ticket sales nationwide” (Voz-

zella 2017). It is widely believed that Ticketmaster’s control of

the resale business will create a ticket-intermediary monolith

that will increase the primary-ticket price and harm the welfare

of musicians and consumers.

This article, using the concert-ticket market as an example,

builds an analytical model to examine how the integration of

the primary and the resale platforms (vs. two independent plat-

forms) will affect the primary platform, the resale platform, the

consumers, and the upstream suppliers (e.g., musicians). Our

main analysis considers two scenarios. In the independent-

platforms case, the primary platform and the resale platform

are owned by independent parties. This scenario reflects the

situation in which Ticketmaster did not enter the resale market.

In the integrated-platform case, an integrated platform mono-

polizes both the primary and the resale markets. This setting

captures the situation in which Ticketmaster enters the resale

market and uses Paperless Ticket to prevent consumers from

reselling tickets on other resale platforms. We also examine a

model extension to study the scenario in which the integrated

platform competes with an independent resale platform in the

resale market (i.e., the integrated platform does not preclude

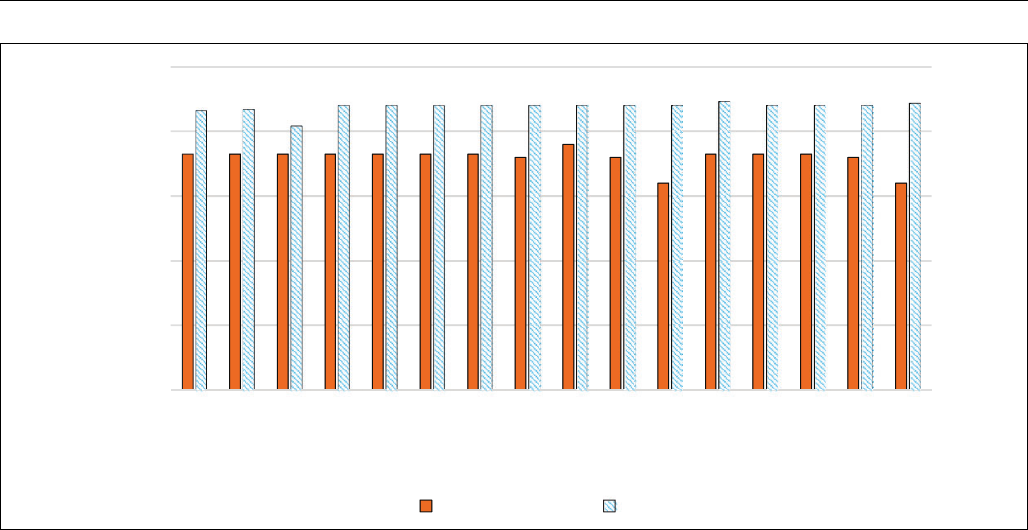

other resale platforms). Figure 2 illustrates these three cases.

In our model, some consumers a re uncertain in the first

period about whether they can a ttend the concert, and that

uncertainty is resolved in the second period. Consumers are

heterogeneous in their probabilities of being able to attend the

concert and their valuations of the concert. If a consumer buys

a ticket in the first p eriod, she can resel l it to other consumers

on the resale platform in the second period. Consumers can

buy tickets from either the primary or the resale plat form, but

if the demand exceeds the supply on a platform, consumers

may not be able to get a ticket from that platform with some

probability. The musician chooses the ticket’s face price and

the venue size (the number of tickets). In the independent-

platforms case, the primary and the resale platforms set their

service fees independently. I n the integrated-pla tform c ase,

Figure 1. Seat map of a concert enrolled in Ticketmaster resale.

660 Journal of Marketing Research 57(4)

the integrated platform decides the service fees for both mar-

kets. The fin al primary-tic ket price paid by c onsu me rs is the

sum of the face price and the service fee of the primary

platform. In essence, the musician and the primary platform

constitute a distribution channel in the primary market. The

equilibrium resale price is jointly determined by the demand

and the supply in the resale market. Consumers have rational

expectations about the future prices and the probabilities

of bein g able t o get a ticket from either t he primary or the

resale mar ket.

The conventional wisdom held by many legislators, news

media, and consumer advocacy groups in the previous exam-

ples would predict that because primary tickets and resale tick-

ets are perfect substitutes to consumers, an integrated platform,

which decides the service fees for both the primary and the

resale markets, will tend to charge higher fees in both markets

than those that two independent platforms will charge. Thus,

platform integration—a monopoly’s control of both the pri-

mary and the resale platforms—will make the consumers and

the musician worse off. However, we show that the opposite

can happen—platform integration can increase the welfare of

both the consumers and the musician. The intuition hinges on

the spillover effect from the primary market to the resale mar-

ket. A lower primary-ticket price will convince more consu-

mers with relatively low likelihood of attending the concert to

buy tickets in the first period. These consumers are more likely

to resell tickets later, which increases the supply in the resale

market and generates more resale transactions. In other words,

lowering the price in the primary market has a positive spil-

lover effect on th e resale market, potentially increasing the

resale profit. In the integrated-platform case, because the inte-

grated platform receives profits from both markets, it will have

an incentive to internalize the spillover effect by lowering the

primary-ticket service fee (and thus the final price) to increase

its resale profit. By contrast, in the independent-platforms case,

the primary platform does not have such an incentive because it

will not receive any resale fees. Thus, platform integration can

potentially benefit consumers because of the lowered price in

the primary market. Furthermore, the integrated platform’s

extra incentive to reduce the primary-ticket price will alleviate

double marginalization in the primary-market channel, which

will tend to increase the musician’s optimal venue size, leading

to more consumers being served. As a result, the musician, the

platform, and consumers can all be better off.

We also find that the musician and consumers can become

better off when t he integrate d platform has no competition

from any third-party resale platform than when it has resale

competition, even when the resale service fee is higher in the

absen ce of resale platform competition . This is because the

lower the integrated platform’s market share of the resale mar-

ket, the weaker the platform’s incentive to reduce its primary-

ticket service fee. Thus, the double-marginalization problem in

the primary-market channel can be exacerbated. Furthermore,

we show that an integrated platform can also have an incentive

to lower the resale fee to boost primary sales, because consu-

mers become more inclined to buy tickets from the primary

market anticipating a lower fee for their potential ticket resales,

consequently making consumers better off. In other words,

there is also a spillover effect from the resale market to the

primary market. Using data from Ticketmaster.com and Stub-

Hub.com, we provide some correlational empirical support for

our predictions.

In another extension, we discuss how the presence of scal-

pers, who buy t ickets with the sole intention of reselling them

at higher prices, affects the market outcome . We find that, in

the integrated-platform case, the existence of a small number

of scalpers can l ead to a lower ticket price, a higher profit for

the musician, and higher consumer surplus. This is because

scalpers are more likely to resell tickets than ordinary con-

sumers, so the integrated platform can earn more resale profit

if more scal pers buy from the primary market. Therefore, the

integrated platform has an i ncentive to keep the primary-

ticket price low enough to attract the scalpers, which can

further a lleviate the double-marginalization p roblem and ben-

efit the musician and consumers.

We want to emphasize that, although our main analysis

focuses on the concert-ticket market, the main insights of this

article can be generalized to broader market settings. Essen-

tially, if the supply in one market positively depends on the size

of another market, then letting an integrated entity control both

markets can lower the final price and allevia te the double-

marginalization problem (if any) in the latter market, which

can benefit all channel members in that market as well as con-

sumers. For example, when more consumers buy new books,

Musician

Primary

Platform

Resale

Platform

Consumers

Independent Platforms

Resale

Platform

Primary

Platform

Consumers

Integrated Platform

Resale

Platform

Primary

Platform

MusicianMusician

Consumers

Competing Resale Platforms

Independent

Resale Platform

Figure 2. Three types of market structures.

Zou and Jiang 661

more will resell their used books; when more consumers buy

new cars, more will share their cars on peer-to-peer car-sharing

platforms. Note that these market settings are very different

from the markets for complementary products, where it is the

product demand (rather than supply) in one market that posi-

tively depends on the size of another market (Cournot 1838). In

fact, in the aforementioned e xamples, from the consumer’s

perspective, the products (fi rsthand tickets and secondhand

tickets, new books and used books, driving a purchased car and

driving a rented car) are substitutes rather than complements.

The conventional belief—stronger competition between firms

selling substitutes will lead to lower prices, alleviate double

marginalization in distribution channels, and benefit consu-

mers—may no longer hold in markets with spillover effects.

We also illustrate these points with a general model.

Literature Review

This research contributes to the economics and marketing lit-

erature on secondary markets for event tickets. Most previous

studies have focused on whether allowing consumers or scal-

pers to resell tickets is beneficial to event organizers and con-

sumers. C ourty (2003b) shows that when consumers are

uncertain about their valuations at the time of purchase, allow-

ing resales cannot increase the event organizer’ s profit. Geng,

Wu, and Winston (2007) examine a similar setting and show

that allowing resales only before the announ cement of the

second-period price can strictly increase the event organizer’s

profit. Courty (2003a) shows that the existence of scalpers will

limit the event o rganizer’s ability of intertemporal price dis-

crimination and hurt its profit. Karp and Pe rloff (2005) find

that the event organizer can benefit from the entry of scalpers if

they can perf ect ly pr ice-di scrimina te consumers. Su (2010)

shows that the presence of scalpers will increase an event

organizer’s profit because the event organizer can sell tickets

to scalpers early and transfer the inventory risk to them. Cui,

Duenyas, and O

¨

zge (2014) find that an event organizer can

benefit from lower resale transaction costs and from selling

consumers an option for buying tickets later. Liao (2019) finds

that partiall y allowing ticket scalping can induce consumers to

buy tickets early, thus benefiting the event organizer. Several

studies have empirically examined how the existence of resale

markets can affect the primary market. Cusumano, Kahl, and

Suare z (2008) show that Craig slist’s entry into the concert-

ticket resale market raises the primary-ticket prices for popular

musicians but lowers those for the less popular ones. Leslie and

Sorensen (2014) find that the existence of resale markets can

increase the allocation efficiency by 5% for major rock con-

certs, but a third of the increase is offset by the ticket brokers’

costly efforts of getting tickets early and the resale transaction

costs. Lewis, Wang, and Wu (2019) show that the presence of a

secondary market for season tickets of a Major League Base-

ball team increases the demand for season tickets in the pri-

mary market. By contrast, secondary-market regulations, such

as minimum-list-price policies, will reduce the demand for

season tickets.

Our article differs from the aforementioned literature in two

fundamental aspects. First, that literature all considers a direct-

selling setting. This work is the first to study how the resale

market can influence the strategic interaction between different

channel members in the primary market (i.e. the [upstream]

musician and the [downstream] ticket platform). Second, the

extant literature focuses on whether the musician or the social

planner should allow consumers or scalpers to resell tickets. By

contrast, our research examines how the musician and consu-

mers are affected by whether the primary platform and the

resale platform are owned and operated by an integrated entity

or independent entities. We find that platform integration can

reduce equilibrium service fees on both platforms, alleviate

double marginalization in the primary-market channel, and

benefit all parties (i.e., the musician, the primary platform, and

consumers) at the same time.

Our article also relates to the literature on retail competition.

The general conclusion of this li terature is that integrations

between downstream retailers will reduce competition and

raise the final retail prices, intensifying double marginalization

and making both the upstream manufacturers and the consu-

mers worse off (Harutyunyan and Jiang 2019; Li 2002; Pad-

manabhan and Png 1998; Tirole 1988; Zhang 2002). This is the

rationale for the antitrust regulations against many horizontal

mergers (Hovenkamp and Shapiro 2017). In contrast, our arti-

cle shows that platform integration can lower the final ticket

price in the primary market and increase the welfare of the

musician and c onsumers. The difference in findings arises

because of the positive spillover effects between primary and

resale platforms, which are absent in markets with competing

retailers in general.

This article also contributes to the literature on secondary

markets for used goods. Swan (1970, 1972, 1975) shows that

the existence of the used-goods resale market will not limit a

monopoly seller’s profits. Rust (1986) shows that if consumers

endogenously decide when to resell their durable goods, the

monopolist firm may purposely reduce the durability of its

product. Anderson and Ginsburgh (1994) find that when con-

sumers hav e heterogene ou s p ref ere nces over n ew and u sed

goods, a used-goods market can benefit a monopoly seller by

allowing it to price-discriminate consumers. Purohit and Stae-

lin (1994) consider a car manufacturer selling to end consumers

and rental companies, both of which resell their used cars on

the resale market. They show that a higher substitutability

between used rental cars and new cars will harm the manufac-

turer but benefit the dealers. Desai and Purohit (1998) consider

a car manufacturer’s leasing and selling policies in a market

with consumers’ reselling of their used cars; they find that the

manufacturer may choose leasing, selling, or both, depending

on the depreciation rates of sold versus leased cars. Hendel and

Lizzeri (1999) find that a monopolist can benefit f rom the

secondary market even though the used-go ods market will

compete with the new-goods market. Shulman and Coughlan

(2007) study a monopoly manufacturer’s optimal pricing deci-

sion when the retailer can buy back and resell used products.

They find that under certain conditions, the manufacturer may

662 Journal of Marketing Research 57(4)

find it optimal not to sell any new goods in the second period.

The aforementioned literature mainly considers the situation in

whi ch consumers use a durable product for a period of time

before they resell it. By contrast, in our model, concert tickets

can be used only once but can be purchased at different times, and

consumers are ex ante uncertain whether they can attend the

concert. Our research question—how the integration of the pri-

mary and the resale platfor ms will affect the musician,

the platform, and the consumers—is also novel and practically

relevant.

Model

Consider a musician (denoted by M) who plans to organize a

future concert in a city. He sells the tickets via a primary ticket

platform (d enoted by P).

3

The musician decides the size of

performance venue to rent. His cost for renting a venue is

c N, where N is the venue size (the total number of available

seats) and c>0isaconstant.Let

N denote the size of the

largest venue in the city, so N

N. As is typically the case

for Ticketmaster, the musician will choose the face price f for

the tickets, and then the primary platform will set a service fee

for consumers.

4

Let p denote the final price that a consumer

pays for a ticket. Equivalently, the primary platform’s per-

ticket service fee is p f.

5

Without loss of generality, we assume that there is a unit

mass of consumers (indexed by i) in the market. Consumers are

heterogeneous in their valuations for the concert. A fraction a

of consumers are “avid fans,” denoted by A, whose valuation

for the concert is V

A

if they can attend it. The rest of the

consumers ( a fraction 1 a) are “casual fans,” denoted by

C, whose valuation for the concert, conditional on attending,

is V

C

< V

A

. Consumers ex ante are uncertain about whether

they will hav e future time conflicts with the concert, e.g. a

friend’s party. Because avid fans value the concert more than

casual fans, they are more likely to choose the concert over the

conflicting event than casual fans do. Let r

i

be the probability

that consumer i can attend the concert. For tractability, we

assume r

i

¼ 1 for avid fans and r

i

*uniform 0; 1ðÞacross the

population of casual fans. In the Web Appendix, we relax this

assumption by numerically analyzing a model in which both

avid and casual fans have the same probability of attending the

concert, to show that all the main results remain qualitatively

unchanged. Each consumer ex ante knows her own r

i

, but the

platforms cannot identify each consumer’s type. If a consumer

does not attend the concert, her utility from the concert is

normalized to zero. Therefore, a type- i consumer has probabil-

ity r

i

of having v

i

¼ V

i

and probability 1 r

i

of having

v

i

¼ 0. Each consumer buys at most one ticket. The tie-

breaking rule is that consumers will buy tickets if they are

indifferent between buying a ticket and not buying.

Consumers can buy their tickets in two periods. In the first

period, casual fans are uncertain about whether they can attend

the concert, but in the second period the uncertainty is resolved.

Consumers who bought tickets in the first period can choose to

resell their tickets on the resale platform (denoted by R) in the

second period, even if they can attend the concert themselves.

Let r denote the resale price. To acquire a ticket, consumers

can buy it from the primary platform at p or from the resale

platform at r. In practice, resale platforms (e.g., StubHub,

Ticketmaster) usually charge a percentage fee for resale trans-

actions. Let k 2 0; 1½denote the resale platform’s percentage

resale service fee, so a consumer will receive 1 kðÞrfor

reselling her ticket. The main analysis considers the case of

exogenous service fee k and discusses the main insights. We

also study an extension in which the platforms can endogen-

ously choose k.

Next, we describe how the equilibrium resale price r

is

determined in our model. A natural candidate for r

is the

market-clearing resale price at which the number of consumers

willing to resell their tickets (the resale supply) is equal to the

number of consumers willing to buy resale tickets (the resale

demand). However, such a market-clearing resale price may not

exist in our setting. This is because in the second period, con-

sumers’ ex-post valuations of attending the concert, v

i

,canonly

be V

A

,V

C

, or zero, so both the resale demand and the resale

supply are non-continuous functions. To identify a unique equi-

librium resale price r

,weassume r

to be the maximum resale

price that clears the supply in the resale market with all resale

tickets sold at r

. This definition is conceptually similar to the

marketing-clearing price.

6

Note that r

will be V

A

,V

C

,orzero

in equilibrium. Table 1 exhibits several examples of the equili-

brium resale price in different resale-supply scenarios in which

the resale demand comes from 10 fans with willingness-to-pay

of $10 and 20 fans with willingness-to-pay of $5.

One can show that, when

N a (i.e., the largest venue in the

city cannot hold all avid fans), the musician will set the ticket’s

face price f ¼ V

A

, and the primary platform and the resale

platform will receive zero surplus. We focus on the more inter-

esting case of

N> a for the remainder of the article. To obtain

3

For ease of exposition, we refer to a platform as “it,” the musician as “he,”

and the consumer as “she.”

4

In practice, typically, musicians set the ticket’s face prices and Ticketmaster

makes all tickets available for sale at the same time. Ticketmaster merely sells

the tickets on behalf of the musicians. (For details, see https://help.

ticketmaster.com/s/article/Purchase-Policy.) Note also that Ticketmaster sets

the service fees for tickets on a concert-by-concert basis. For evidence of

Ticketmaster setting different service fees for different concerts with the

same or similar ticket face prices, see the Web Appendix.

5

It is equivalent to assume that the primary platform charges a percentage fee

of p fðÞ= f. In practice, Ticketmaster charges percentage fees only in the

resale market but not in the primary market. For details, see Figure D1 in the

Web Appendix. Moreover, the main analysis assumes that the platform does

not dynamically adjust its price. In the Web Appendix, we prove that all results

remain qualitatively the same when the platform can dynamically adjust its

price.

6

The definition implies that for any resale price r> r

, the resale demand will

be smaller than the resale supply, and that for any r r

, the resale demand

will be greater than or equal to the resale supply.

Zou and Jiang 663

closed-form solutions, we assume that N 2 a= 1 þ aðÞ.

7

These conditions are equivalent to N= 2 N

a < N.

The timeline of the game is as follows. First, the musician

decides the venue size N 2 0;

N

and the ticket’s face price f.

The primary platform subsequently sets the final ticket price p

(in effect charging a service fee p f per ticket). In the first

selling period, consumers will decide whether to buy tickets

from the primary market. In the second period, consumers learn

whether they can attend the concert. Those who successfully

bought tickets in the first period can opt to resell their tickets in

the resale market. Those without a ticket can choose to buy a

ticket from either the primary platform (if tickets have not sold

out) or from the resale market, and if they want to buy a ticket,

they will try to buy from the cheaper platform first if ticket

prices are different on the two platforms. If the demand exceeds

the supply on a platform, tickets will sell out on that platform

and consumers who fail to get a ticket from that platform can

then decide whether to buy from the other platform. Whenever

demand exceeds supply, consumers are assumed to have equal

chances of getting a ticket. Figure 3 illustrates the event

sequence, and the derivation of consumers’ utility functions

are relegated to the Web Appendix.

Our main analysis considers two scenarios regarding

whether the primary and the resale platforms are operated by

the same entity. In the case of independent platforms (denoted

by IDP), the primary and the resale platforms are operated by

independent entities that maximize their respective profits.

This case reflects the situation in which Ticketmaster (the pri-

mary platform) has not entered the resale market. In the case of

integrated platform (denoted by INT), the two platforms are

owned by the same entity that maximizes the joint profit of the

two platforms. This case reflects the situation in which Ticket-

master enters the resale market and uses its Paperless Ticket

system to prevent consumers from reselling tickets on other

platforms. Comparing these two cases helps us examine how

Ticketmaster’s control of the resale market will affect the musi-

cian and consumers. In a later extension, we will examine a

scenario in which an int egrated platform competes with the

independent resale platform in the resale market. Table 2 pro-

vides a summary of the major notations.

Analysis

We solve for rational-expectation subgame-perfect equilibria.

In such equilibria, the musician, the primary platform, the

resale platform, and consumers have rational expectations

about the resale price and the consumers’ probability of getting

a ticket from a platform. Given the final price p, the resale

percentage fee k, and the venue size N, there may exist mul-

tiple equilibria with different consumer beliefs on how many

consumers will buy tickets in the first period. If the belief is that

many consumers will buy tickets in the first period, consumers

may also want to buy tickets early because they believe that

there will be few tickets left in the second period. However, if

the belief is that few consumers will buy tickets in the first

period, consumers may also postpone buying the ticket until

they know whether they can attend the concert. To pin down a

unique equilibrium, we introduce the concept of the “buying-

spree equilibrium.” We define the buying-spree equilibrium as

the rational-expectation subgame-perfect equilibrium that,

among all possible rational-expectation subgame-perfect equi-

libria, has the highest number of consumers trying to buy tick-

ets in the first period.

8

In the Web Appendix, we prove that the

buying-spree equilibrium is unique in our setting. For concise-

ness, we use “equilibrium” to refer to the unique buying-spree

equilibrium in the rest of the article.

Note that when k<1 ðV

C

= V

A

Þ, or equivalently when

1 kðÞV

A

> V

C

, a casual fan will resell her ticket if the resale

price is r ¼ V

A

regardless of whether her realization of v

i

is V

C

or zero. By contrast, when k 1 ðV

C

= V

A

Þ,orequivalently

1 kðÞV

A

V

C

, a casual fan will not resell her ticket if she has

v

i

¼ V

C

. We divide our analysis into two cases depending on

whether k 1 ðV

C

= V

A

Þ or k<1ðV

C

= V

A

Þ.

The Case of High Resale Percentage Fee

k 1 V

C

=V

A

½ðÞ

This subsection considers the case with k 1 ðV

C

= V

A

Þ.In

this case, the casual fans will not resell their tickets when their

realized valuation is v

i

¼ V

C

. We solve the game by back-

ward induction. First, we examine the consumers’ buying and

reselling decisions given N, f, and p. Clearly, choosing

N < a is a strictly s uboptimal strategy for t he musician,

because he can earn a strictly higher profit by setting N ¼ a and

Table 1. Examples of Equilibrium Resale Prices r

:

Supply of Resale Tickets Equilibrium r

5 fans want to resell tickets $10

25 fans want to resell tickets $5

35 fans want to resell tickets $0

Notes: Fans reselling tickets are assumed to have zero valuations here (i.e., not

being able to attend the concert).

7

This assumption is to ensure closed-form solutions for the full equilibrium

outcome. Our main results will qualitatively hold as long as

N is not too large.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out that our result applies to

situations in which the musician cannot serve all consumers in the market. In

practice, the venue size is usually limited (e.g., due to physical constraints) and

the potential demand often exceeds the capacity limit, especially for popular

artists. Ginsburgh and Throsby (2013) show that 43% of the concerts are sold

out in their sample, and the sell-out rates are higher than 85% for artists such as

Madonna, Billy Joel, Elton John, and Garth Brooks. Moreover, as we will

demonstrate in the “Discussion and a General Model” section, our main

insight does not actually require these modeling details of the concert-ticket

industry.

8

This is a reasonable assumption especially for more pop ular concerts. In

reality, consumers often rush to buy tickets as soon as tickets are released,

and many concerts sell out in the first few hours. For example, The Rolling

Stones sold out 75,000 tickets in 51 minutes for their “14 on Fire” tour in Paris

in 2014 (RFI 2014).

664 Journal of Marketing Research 57(4)

f ¼ V

A

. Moreover, in the Web Appendix, we also show that the

primary platform (in the independent-platforms case) and the

integrated platform (in the integrated-p latform case) will set

p 2 1 kðÞV

A

; V

C

y V

C

1 kðÞV

A

½½[V

C

; V

A

fg

,

where y 1

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1aðÞaa1þ2NðÞa

2

2N

2

½

p

1aðÞN

2 0; 1ðÞ. Thus, in the

rest of this subsection, we present the analysis only for the vari-

able region with a N

Nand p2 1 kðÞV

A

;½

V

C

y V

C

1 kðÞV

A

½[V

C

; V

A

fg

. Lemma 1 sum-

marizes how the final price p affects the equilibrium market

outcome.

Lemma 1: Suppose p 2 1 kðÞV

A

; V

C

y V

C

1ð½½

kÞV

A

[ V

C

; V

A

fgand N 2 a; N

. In equilibrium,

(a) if p ¼ V

A

, all avid fans will buy tickets from the pri-

mary market in the first period, casual fans will not buy

any tickets, no resale transactions happen, and the pri-

mary platform’s profit is p

P

¼ V

A

fðÞa.

(b) if p ¼ V

C

, all avid fans will buy tickets from the pri-

mary market in the first period, all casual fans with

realized valuation v

i

¼ V

C

will try to buy tickets from

the primary market in the second period, no resale

Decisions of musicians

and plaorms

Decisions of musicians

and plaorms

B 1 Bu

Musician decides N

and f

Plaorm decides p

Buy now?

Can

aend?

Have ckets

No

Don’t have

ckets

Yes

Successfully

get ckets?

Yes

No

Can

aend?

Don’t have

ckets

Resell ckets

Resell?

Aend

Concert

Yes

No

Yes

No

No

Buy from

primary or resale

mkt?

Yes

Successful?

Yes

Not buy

Primary or Resale

No, choose

another choice

Figure 3. Sequence of events.

Table 2. Table of Notations.

N,

N

Actual venue size and maximum venue size

v

i

A consumer’s valuation of the concert

r

i

A consumer’s probability of being able to attend a concert

V

A

,V

C

Valuations of avid fans and of casual fans, respectively

c Marginal cost for the musician

f Ticket face price

p Ticket final price in the primary market

r Resale price

k Resale percentage fee

a Population of avid fans

b Population of scalpers

p

M

; p

I

, p

P

,

p

R

Profits of the musician, the integrated platform, the

primary platform, and the resale platform,

respectively

INT The subscript denoting the “integrated-platform case”

IDP The subscript denoting the “independent-platforms case”

Zou and Jiang 665

transactions happen, and the primary platform’s profit is

p

P

¼ V

C

fðÞN.

(c) if 1 kðÞV

A

p V

C

y V

C

1 kðÞV

A

½,

casual fans with r

i

> r

¼

p 1kðÞV

A

V

C

1kðÞV

A

and all avid fans

will try to buy tickets in the first period and can success-

fully get a ticket with probability N= D

1

,where

D

1

¼ a þ 1 aðÞ1 r

ðÞN is the first-period

primary-market demand. In the second period, the equi-

librium resale pric e is r

¼ V

A

, the resa le supply is

S

R

¼ N= D

1

ðÞD

1

aðÞ1 r

ðÞ=2½,andtheresale

demand is D

R

¼ 1 N= D

1

ðÞ½a S

R

. Th e pr ofits

of the primary plat form a nd the resa le platform are

p

P

¼ p fðÞN and p

R

¼ kV

A

S

R

, respectively.

When p V

C

, no casual fans will buy from the primary mar-

ket in the first period, so there will be no consumers reselling

tickets in the second period. By contrast, when

1 kðÞV

A

p V

C

y V

C

1 kðÞV

A

½, tickets will

sell out, and some casual fans will try to buy tickets in the first

period and later resell their tickets if they cannot attend the

concert. An important observation is that, when p decreases

in this parameter region, more casual fans with lower r

i

will

try to buy and can successfully get tickets from the primary

market in the first period (technically, 1 r

increases when

p decreases), and these consumers are more likely to resell

their tickets. Therefore, a lower primary-ticket price ( p) will

increase the resale supply, S

R

(i.e., dS

R

= dp<0). We call this

effect the spillover effect from the primary market to the resale

market. Moreover, in our case, a decrease in p will also

increase the resale demand, D

R

(i.e., dD

R

= dp<0Þ. The intui-

tion is that when p decreases, more casual consumers will try to

buy tickets in the first period, reducing the avid fans’ probabil-

ity of successfully getting tickets from the primary market, so

more avid fans need to buy tickets from the resale market. As a

consequence, the lower the final ticket price in the primary

market ; the more resale transactions and the higher profit for

the resale platform.

Decisions of the platform and the musician. Next, we compare the

decisions of the platform and the musician in the independent-

platforms case and in the integrated-platform case. We start by

analyzing the platform’s decisions conditional on the musi-

cian’s choice of f and a N

N.

First, consider the case of independent platforms. The pri-

mary platform maximizes its own profit p

P

, which is

p

P

pðÞ¼

V

A

fðÞa; if p ¼ V

A

;

V

C

fðÞN; if p ¼ V

C

;

p fðÞN; if 1 kðÞV

A

p V

C

y V

C

1 kðÞV

A

½:

8

>

>

>

>

<

>

>

>

>

:

ð1Þ

The primary platform will never choose p< V

C

, because it can

already sell all tickets at p ¼ V

C

. In equilibrium, the primary

platform will set p to either V

C

or V

A

, both precluding any

resale transaction in the second period.

9

The primary platform

will set p ¼ V

A

when the population of avid fans is suffi-

ciently large ( a> NV

C

fðÞ= V

A

fðÞ); otherwise, the pri-

mary platform will set p ¼ V

C

.

Next, we consider the integrated-platform case. In this case,

the integrated platform maximizes the joint profit of the pri-

mary and the resale platforms, p

I

¼ p

P

þ p

R

, which is

p

I

pðÞ¼p

P

pðÞþp

R

pðÞ

¼

V

A

fðÞa; if p ¼ V

A

;

V

C

fðÞN; if p ¼ V

C

;

p fðÞN þ kV

A

S

R

; if 1 kðÞV

A

p V

C

y V

C

1 kðÞV

A

½:

8

>

>

>

>

>

<

>

>

>

>

>

:

ð2Þ

In contrast to the independen t-platforms case, even when

p < V

C

, further reducing p can increas e t he integrated

platform’s profit if the spillover effect is sufficiently strong.

Specifically, if reducing p can significantly expand the

resale supply such that dS

R

= dp < N= kV

A

, then reducing

p will increase the integrated p latform’s profit when

p 2 1 kðÞV

A

; V

C

y V

C

1 kðÞV

A

½

fg

. Proposition

1 establishes one of the key results of our research: compared

with the independent-platforms case, an integrated p latform

has extra incentives to lower its price in the primary market

to facilitate resale transactions.

Proposition 1: (Platform i ntegration can reduce the

primary-ticket price.) In the integrated-pla tform case, if

a min

2kðÞV

A

2V

C

kV

A

;

V

A

2kðÞ2f

V

A

2þNkðÞ2f

N

no

, the integrated plat-

form will set p ¼ 1 kðÞV

A

< V

C

, which is lower than its

level in the independent-platforms case. The equilibrium

resale price is r

¼ V

A

. The profits from the primary mar-

ket and the resale market are p

P

¼ 1 kðÞV

A

Nand p

R

¼

kV

A

N1aðÞ

2

, respectively. The integrated platform’s total

profit is p

I

¼ NV

A

1

k1þaðÞ

2

f

hi

.

In contrast to the case of independent platforms where

p V

C

, the integrated platform will choose some p < V

C

if the population of avid fans ( a) is low enough. In this case,

although the integrated platform generates less profit from the

primary market than when setting p ¼ V

C

, the platform will

gain more profit from the resale market. The intuition that a

must be low is as follows. When the population of avid fans is

low, many primary tickets will be bought by the casual fans and

thus there will be many resale transactions. In other words, the

spillover effect is stronger when a is lower. Note that, in our

setting, the integrated platform is willing to reduce p only if the

resulting equilibrium resale price is high ( r

¼ V

A

). This is

9

This “no resale” result relies on our assumption that avid fans with tickets

will always attend the concert. One should interpret the “no resale” result as

that in the independent-platforms case the primary platform will have less

incentive to encourage first-period purchases from casual fans.

666 Journal of Marketing Research 57(4)

because a high r

implies a high resale profit margin, which

incentivizes the platform to boost resale transactions.

One might expect that the integrated platform will have stron-

ger incentives to set p< V

C

to encourage casual fans to buy

tickets in the first period when the resale percentage fee ( k) is

higher, because each resale transaction can generate a higher

transaction fee for the platform. However, Proposition 1 indi-

cates the opposite: The condition a min

n

2kðÞV

A

2V

C

kV

A

;

V

A

2kðÞ2f

V

A

2þNkðÞ2f

N

o

is more likely to be true when k is lower. When

k is lower, casual fans will be more willing to buy tickets in the

first period, because they will pay a lower resale service fee if

they cannot attend the concert. As a result, the integrated plat-

form can induce casual fans to buy tickets in the first period

by only slightly reducing p, which will not significantly

reduce its primary-market profit. Therefore, the integrated

platform is more likel y to set p< V

C

to facili tate resale trans-

actions. In addition, the condition a min

n

2kðÞV

A

2V

C

kV

A

;

V

A

2kðÞ2f

V

A

2þNkðÞ2f

N

o

is more likely to be t rue when the venue size

( N) is larger, because there will be more casual fans being

able to get tickets in the first period and reselling in the second

period. In other words, the spillover effect is stronger when N

is larger, or mathematically, dS

R

= dp is proportional to N.

Next, we investigate the musician’s optimal decisions for

the face price f and the venue size N. We start with the

independent-platforms case. Lemma 2 characterizes the musi-

cian’s equilibrium choices of the venue size ( N

IDP

) and the

face price ( f

IDP

) in the independent-platforms case.

Lemma 2: Let a

IDP

N1

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

V

A

V

C

V

A

c

q

.Inthe

independent-platforms (IDP) case:

(a) If a a

IDP

, the musician will choose N

IDP

¼ N and

f

IDP

¼

NV

C

aV

A

Na

, the primary platform will set

p

IDP

¼ V

C

, all avid fans will buy tickets in the first period,

and casual fans with realized v

i

¼ V

C

will try to buy

tickets from the primary platform in the second period.

The corresponding consumer surplus is a V

A

V

C

ðÞ.

(b) If a > a

IDP

, the musician will choose N

IDP

¼ a and

f

IDP

¼ V

A

, the primary platform will set p

IDP

¼

f

IDP

¼ V

A

, avid consumers will buy tickets from the

primary platform, and casual fans will not buy tickets in

either period. The corresponding consumer surplus is

zero.

When the population of a vid fans is sufficient ly large

(a > a

IDP

), the primary platform will have a strong incentive

to set p ¼ V

A

and serve only the avid fans, unless the ticket’s

face price f is so low as to a lso make serving casual fans

profitable. Because setting such a low f will severely reduce

the musician’s profit margin, he will rather choose a small

venue size (N ¼ a) and a high face price (f ¼ V

A

) to serve

only the avid fans and extract all their surplus himself. By

contrast, if a a

IDP

, the musician will choose a large venue

size (N ¼

N) and a low face price (f ¼

NV

C

aV

A

Na

), and the

prima ry platform will set p ¼ V

C

in equilibrium, in which

case both the avid fans and the casual fans are served. As we

have shown, no resale transaction will occur in either case.

We now investigate the integrated-platform case. Lemma 3

characterizes themusician’s equilibrium choices of the venue size

(N

INT

)andthefaceprice(f

INT

) in the integrated-platform case.

Lemma 3: Let a

INT

min

2kðÞV

A

2V

C

kV

A

;

n

N1

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

V

A

kV

A

k N

2

þ81þN

ðÞ

V

A

cðÞ

q

V

A

k N

4V

A

cðÞ

2

4

3

5

g

.Inthe

integrated-platform (INT) case:

(a) If a a

INT

, the musician will choose N

INT

¼ N and

f

INT

¼ 1

Nk 1þaðÞ

2

Na

ðÞ

V

A

, the integrated platform will

set p

INT

¼ 1 kðÞV

A

, and all consumers will try to

buy tickets in the first period. The equilibrium resale

price is r

¼ V

A

, and the equilibrium volume of resale

transactions is

N1aðÞ

2

. Consumer surplus is

N aV

A

k þ

1aðÞV

C

1kðÞV

A

½

2

hi

.

(b) If

2kðÞV

A

2V

C

kV

A

< a a

IDP

, the musician will choose

N

INT

¼ N and f

INT

¼

NV

C

aV

A

Na

, the integrated plat-

form will set p

INT

¼ V

C

, all avid fans will buy tickets

in the first period, and casual fans with realized v

i

¼ V

C

will try to buy tickets in the primary market in the second

period. Consumer surplus is a V

A

V

C

ðÞ.

(c) If a is not in the regions in (a) or (b), the musician will

choose N

IDP

¼ a and f

IDP

¼ V

A

, the integrated plat-

form will set p

IDP

¼ f

IDP

¼ V

A

. Avid consumers will

buy tickets in the primary market, and casual fans will not

buy tickets in either periods. Consumer surplus is zero.

10

Part (a) of Lemma 3 i s the interesting case: When

a a

INT

, in equilibrium the integrated platform will charge

p< V

C

to boost resale transactions. Proposition 1 shows that

when a is low and N is large, an integrated platform will have

a strong incentive to reduce p to serve more casual fans even if

the musician charges a relatively high face price, f . Thus, the

musician will be more inclined to choose a larger N to serve

both the avid and the casual fans.

Comparison of the independent-platforms case and the integrated-

platform case. Having characterized the equilibrium outcomes

in the independent-platforms ca se and in the integr ated-

platform case in Lemmas 2 and 3, Proposition 2 proceeds

to compare the equilibrium outcomes of those two cases to

determine how platform integration will affect the market

outcome.

10

The parameter regions of a in (a) or (b) may be empty.

Zou and Jiang 667

Proposition 2: (Platf orm integration can alleviate double

marginalization.) Suppose a

IDP

<a a

INT

. Compared with the

independent-platforms case (IDP), in the integrated-platform

case (INT):

(a) The musician will choose a strictly lower ticket face

price and a strictly larger venue size, resulting in a

strictly lower final price (i.e., f

INT

< f

IDP

,N

INT

>

N

IDP

, and p

INT

< p

IDP

).

(b) The musician’s profit is strictly higher and the plat-

form’s profits in both markets are strictly higher (i.e.,

p

M; INT

> p

M; IDP

, p

P; INT

> p

P; IDP

and p

R; INT

> p

R; IDP

).

Consumer surplus is also strictly higher.

Proposition 2 shows that when a is in an intermediate range,

platform integration can actually lead to a lower final ticket

price, higher profits for the musician and the platforms, more

consumers attending the concert, and higher consumer surplus

at the same time. Platform integration will give the platform a

stronger incentive to lower the final price p (conditional on the

musician’s choice of f) to serve both the avid and the casual

fans, which will alleviate double marginalization i n the

primary-market distribution channel. This implies that plat-

form integration can allow more of the reduction in face price

to be passed through to consumers, so the musician is more

likely to choose a larger venue size N and charge a lower face

price f to s erve more c onsumers. Specific ally, when

a

IDP

< a a

INT

, the musician will choose a smaller venue

(N

IDP

¼ a) if the platforms are independent but will choose

a larger venue ( N

INT

¼ N) if the platforms are integrated. In

such a case, platform integration can lead to an all-win outcome

for the musician, the platforms, and the consumers.

In summary, platform integration can benefit consumers, the

musician, and the primary and the resale platforms in two ways.

First, Proposition 1 implies that platform integration will incenti-

vize the platform to lower the final price in the primary market to

internalize the spillover effect, which can benefit consumers.

Second, Proposition 2 suggests that platform integration can alle-

viate double margi nalization in the prima ry-market channel,

which can benefit consumers, the musician, and the platforms.

We want to point out how our setting relates to the setting of

markets for complementary products (e.g., game consoles and

video games). In a complementary product setting, lowering

the price in one market will also lead to more transactions in

another market, so a monopoly controlling both markets can

result in lower prices and higher consumer surplus compared

with having two independent firms control the two markets

(Cournot 1838). This finding is similar to ours. However, the

underlying mechanism is very different. In the setting of com-

plementary products, a lower price in one market will increase

the demand in another market (for the complementary prod-

uct). By contrast, in the setting of concert tickets, a lower ticket

price in the primary market will increase the su pply in the

resale market. We show that, even though primary tickets and

the resale tickets are (perfect) substitutes, letting an integrated

entity controlling both markets can still benefit consumers

because of the aforementioned spillover effect.

As a side note, besides alleviating double marginalization,

platform integration can enhance the musician’s incentive to

induce resales to extract more surplus from the resale transactions.

As we explain next, the integrated platform can more efficiently

extract consumer surplus by facilitating resales, thus the musician

may also charge an appropriate face price to extract some of the

profit gain for himself. This effect will harm consumers but can

benefit musicians. To see this effect, let us consider the case with

N ¼

N. If p ¼ V

A

, the platform can extract all avid fans’ sur-

plusbut cannot serve any casual fan. If p ¼ V

C

, then all avid fans

can successfully get tickets from the primary market in the first

period. There will be no resale in this case, and all avid fans have a

surplus of V

A

V

C

although the surplus of some casual fans

can be extracted. By contrast, if p ¼ 1 kðÞV

A

< V

C

, all con-

sumers will try to buy tickets in the first period, so some avid fans

cannot get tickets from the primary market and have to pay a

higher price V

A

to buy from the resale market. Thus, more con-

sumer surplus can be extracted if p is lowered to 1 kðÞV

A

to

facilitate resales, because at the lowered p, all surplus of avid fans

who purchase from the resale market is extracted (relative to when

p ¼ V

C

) whilesome casual fans are also served (relative to when

p ¼ V

A

). In the integrated-platform case, the musician can cap-

ture part of the integrated platform’s profit gain from the resale

transactions by raising his face price. By contrast, in the

independent-platforms case, the musician cannot do so because

the primary platform does not receive any profit gain from resale

transactions. To summarize, platform integration can incentivize

the musician to induce resales to indirectly extract some profit

gain from the resale market.

Platform integration’s effect on the musician’s incentive to

induce resales is manifested in our results. As shown in Lemma

2 and 3, if a< min a

IND

; a

IDP

fg

, in both the independent-

platforms and the integrated-platform cases, the musician will

choose N ¼

N, so platform integration does not affect the equi-

librium market coverage through alleviation of double margin-

alization. However, in this parameter region, platform integration

will have an effect on the musician’s incentives to induce resales

to extract more consumer surplus. Compared with the

independent-platforms case, consumer surplus is lower, the equi-

librium face price and the musician’s profit are higher in the

integrated-platform case. We also find that, in this parameter

region, platform integration will reduce the social welfare. This

is because, though all

N tickets are consumed, in the independent-

platforms case, all avid fans will obtain tickets in equilibrium

whereas, in the integrated-platform case, some avid fans will not

be able to get tickets from either the primary or the resale market.

The Case of Low Resale Percentage Fee

ðk<1 ½V

C

=V

A

Þ

If k<1 ðV

C

= V

A

Þ, all casual fans will be willing to resell

their tickets when r ¼ V

A

even when their realized valuation

668 Journal of Marketing Research 57(4)

is v

i

¼ V

C

. However, if r V

C

, casual fans will not resell

their tickets if v

i

¼ V

C

.

Lemma 4: If k<1 ðV

C

= V

A

Þ and N> a, then r

V

C

as long as some consumers will resell their tickets in

equilibrium.

Note that, in our setting, the equilibrium resale price r

can

only be V

A

,V

C

, or zero. Lemma 4 shows that the resale price

cannot be high ( V

A

) if k is relatively low. This is because if

r

¼ V

A

, the low k will encourage all casual consumers to

buy tickets in the first period and resell them later regardless of

their realized v

i

, which will increase the resale supply so much

that r

can no longer be su stained at V

A

—a contradiction.

Because the resale platform’s profit per resale transaction is

k r

,if k<1 ðV

C

= V

A

Þ and r

V

C

, the integrated

platform will have limited incentive to reduce p to boost resale

transactions. It turns out that in equilibrium the integrated plat-

form will never cho ose p< V

C

, so there will be no resale

transactions. Thus, if k<1 ðV

C

= V

A

Þ, platform integration

will not affect the equilibrium outcome.

Extensions and Empirical Support

In this section, we consider several model extensions. First,

we examine how t he presence of scalpers will aff ect the mar-

ket outco me. Second, we s tudy the optimal resale percentage-

fee decisions in both the independent-platforms case and the

integrated-platform case. Third, we consider the scenario that

the i ntegrated platform competes with an independent resale

platform in the resale market. Finally, we provide some cor-

relational, suggestive empirical support for our theoretical

results.

The Impact of Scalpers

Oftentimes, many scalpers buy tickets from the primary market

and resell them at higher prices. According to Scott Cutler, chief

executive officer of StubHub, nearly half of ticket resales on

StubHub come from “professional” traders (Sullivan 2017). It

is generally believed that scalpers make profits by raising the

effective prices paid by consumers and thus harm the welfare of

consumers and the musicians. The official Twitter account of the

rock band LCD Soundsystem derogated scalpers as “parasites”

(Horowitz 2017). Scalpers usually use computer bots to buy

hundreds of tickets within minutes after tickets start selling.

To combat scalpers, former U.S. President Bara ck Obama

signed the Better Online Ticket Sales Act in 2016, which

restricts the use of software bots to obtain and resell event tick-

ets. Many U.S. states have also passed legislations banning or

restricting scalping behaviors. Ticketmaster has also introduced

the Verified Fan system, which can block 90% of buying

attempts from ticket scalpers (Brooks 2017). In this extension,

we investigate how the existence of scalpers affects ticket prices,

profits of the musician and platforms, and the consumers under

different market structures (i.e., whether the primary and the

resale platforms are independent or integrated).

In this extension, we assume that besides the unit mass of

regular consumers (avid and casual fans), there are b number

of scalpers who can also buy tickets from the primary platform

and resell them on the resale platform. Scalpers have zero

valuation for attending the concert, but they move earlier than

regular consumers in the first period when buying tickets from

the primary platform. The main model in the previous section is

the special case of b ¼ 0. For closed-form analytical solutions,

we focus on the parameter region of b 2 a 1 þ aðÞ

N

=

1 aðÞ(i.e., there are only a small number of scalpers). To

illustrate the most interesting result, in this extension, we ana-

lyze the case with k 1 V

C

= V

A

ðÞand a N

2 a= 1 þ aðÞ. We show that, even when scalpers have the abil-

ity to buy tickets earlier than regular consumers, the scalpers’

presence can still result in lower ticket prices and higher con-

sumer surplus and make both the musician and the integrated

platform better off.

11

This contrasts the independent-platforms

case, in which one can show that, in the same assumed para-

meter region, the presence of scalpers has no effect on the

market outcome, because the primary platform will find it

optimal to set a sufficiently high final ticket price ( p) so that

no scalpers will buy tickets in equilibrium.

First, we analyze the integrated-platform case. We begin by

examining the subgame in which the integrated platform will

choose its optimal final price p, conditional on the musician’s

choices of N and f. Similar to the previous section, it is not

optimal for the musician to choose a venue size N< a,sowe

need only consider the c ase of

N N a. Note that the

scalpers will buy tickets from the primary market only if p is

low enough (i.e., p 1 kðÞ

c

r

) so that they will make a

positive profit from reselling.

12

Lemma 5 shows that it may

be optimal for the integrated platform to choose p low enough

such that scalpers will buy tickets in the primary market.

Lemma 5: Given the musician’s choices of N and f , the

integrated platform will choose p ¼ 1 kðÞV

A

if and only if

a<

2N V

A

V

C

ðÞ

NbðÞkV

A

1and f< V

A

1

k1þaðÞNbðÞ

2NaðÞ

hi

,inwhich

case all scalpers and regular consumers will try to buy tickets

in the first period, the equilibrium resale price is r

¼ V

A

, and

the integrated platform’s total profit is p

I

¼

1þa

2

bkV

A

þ

NV

A

1

k1þaðÞ

2

f

hi

.

It is worth mentioning that when the conditions in Lemma 5

are satisfied, the integrated platform’s profit, p

I

, increases with

the number of scalpers ( b). Letting scalpers buy tickets in the

first period tends to increase transactions in the resale market

because scalpers are more likely (with probability one) to resell

the tickets than regular consumers. Consequently, the presence

of the scalpers can strengthen the spillover effect. Relatedly,

11

Our results are qualitatively the same if scalpers and regular consumers have

equal probability of getting tickets.

12

We use “^” over variables to indicate a consumer’s rational prediction of

those variables.

Zou and Jiang 669

letting scalpers buy tickets in the first period can reduce the

avid fans’ probability of getting tickets from the primary mar-

ket, so more avid fans will need to buy from the resale market

at the high resale price r

¼ V

A

, and thus the integrated plat-

form can better extract avid fans’ surplus. Therefore, the inte-

grated platform has an incentive to let scalpers buy tickets from

the primary market to create transactions in the resale market.

To attract scalpers, the integrated platform n eeds to keep

p 1 kðÞ

c

r

so scalpers can make a profit. In other words,

the integrated platform will have an extra incentive to lower the

final price on the primary platform.

Define

a

SCP

min N1

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

1b=

N

p

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

V

A

kV

A

k

N

NbðÞþ81þ

NðÞV

A

cðÞ½

p

V

A

k

NbðÞ

4V

A

cðÞ

hi

;

n

2

NV

A

V

C

ðÞ

NbðÞV

A

k

1

g

. We characterize the impact of scalpers on the

market outcome in Proposition 3.

Proposition 3: (Platform integration can make the presence

of scalpers be neficial to regular consumers.) Suppose

V

A

> 2= 2 kðÞ½V

C

, a

INT

< a a

SCP

and b< 2 a½

1 þ aðÞ

N= 1 aðÞ. In the integrated-platform case, the pres-

ence of scalp ers will in equi librium strictly reduce the final

ticket price p

. Moreover, if a> a

IDP

is also satisfied, then

the presence of scalpers will strictly increase the musician’s

profit, the integrated platform’s profit and the consumer surplus

(excluding scalpers).

Contrary to the conventional belief that scalpers will raise

the effective ticket prices paid by consumers and thus reduce

consumer surplus, Proposition 3 shows that, with an integrated

platform, the presence of a small number of scalpers can ben-

efit the platform, t he musician, and the consumers. This is

because the presence of scalpers can induce the integrated plat-

form to strategically reduce the primary-market price to

encourage resale transactions ; which can alleviate double mar-

ginalization in the primary market.

Note that Proposition 3 does n ot suggest that scalpers

will always benefit consumers and the musician. Indeed,

there are several boundary conditions for the presence of

scalpers to be beneficial. For example, if the population of

avid fans is small such that a a

INT

, the platform will find

it optimal to s et p ¼ 1 kðÞV

A

to serve both casua l fans

andavidfansevenwhentherearenoscalpers.Underthis

condition, scalpers will strictly reduce the consume r surplus.

Moreover, the segment size of scalpers bðÞcannot be too

high. If there are too many scalpers, consumers a re worse

off because fewer tickets will be available for regular con-

sumers in the primary market, forcing too many avid fans to

buy res ale tickets at higher pr ices. It is also important to

point out that scalpers can benefit the consumers only when

the primary and the resale platforms are integrated. In the

independent- pla tforms case, the prima ry platform does not

receive any resale profit, so it has n o incentive to reduce the

final ticket price to attract scalpers. Thus, with an indepen-

dent resale plat form, the pre sence of scalpers will not facil-

itate channel coordinationintheprimarymarket.

Endogenous Resale Percentage Fee k

Our main model has assumed the resale percentage fee k to be

exogenous. In this model extension, we a naly ze the optimal

choice of k for the resale platform. In the independent-

platforms case, afte r the musici an has chosen the venue siz e

N and the face pric e f, the prima ry pl atform will set the fina l

price p and the resale platform will set the resale percentage

fee k simultaneously. In the integrated-platform case, the

integrated platform jointly chooses p and k to maximize its

profit. Under the original assumpt ion that avid fans are always

able to attend the concert, in the independent-platforms case,

the primary plat form wi ll al ways find it optimal to choose

p V

C

such that no casual fans will buy in t he f irst period.

Thus, the resale pla tform wil l rece ive z ero profit regardless of

its choice of k. Therefore, to allow for a more meaningful

comparison of how platform integration affects the equili-

brium resale percentage fee k

,weneedbothavidfansand

casual fans to have so me probab ility of not being a ble to

attend the concert. To this end, we introduce another random

interruption that can prevent a consumer from attending the

concert (in addition to the random factor in the main model).

Suppose that the new interruptive events (e.g., mandatory out-

of-town travels or personal emergencies) have a probability d

of occurrence, in which case a consumer (both avid and

casual) will be unable to attend the conce rt. Thus, one can

show that overall, avid fans can attend the concert with prob-

ability r

A

¼ 1 d, a nd the casual fans can atten d with prob-

ability r

C

* uniform 0; 1 dðÞ. Under this assumpt ion, even

if only avid fans buy tickets in the first period, there will still

be resale transactions because avid fans resell the ir tickets in

the second period with probability d. To concisely present the

results, we consider the case of d ! 0

þ

. The qualitative

results will still hold true as long as d is not too large. Pro-

position 4 reveals how platform integration will change the

resale percentage fee.

Proposition 4: (Platform integration can reduce

the resale percentage fee.) When a <

N1½

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

V

A

V

C

ðÞV

A

V

C

ðÞ

N

2

þ81þ

NðÞV

A

cðÞ

½

p

V

A

V

C

ðÞ

N

4V

A

cðÞ

,aninte-

grated platform will choose a strictly lower resale percent-

age fee ( k) than that chosen by an independent resale

platform (i.e., k

INT

< k

IDP

).

Proposition 4 reveals that when t he population of avid fans

is low, the integrated platform’s optimal resale percentage fee

k

INT

will be lower than an independent resale platform’s

choice, k

IDP

. The intuition is as follows. A lower resale per-

centage fee can incentivize consumers to buy tickets in the

primary market, because their future potential reselling cost is

lower. In other words, lo we ring k will hav e a positive spil-

lover effect from the resale market to the prima ry ma rket. An

integrated platform can internalize the spillover effect and

tends to reduce k.

670 Journal of Marketing Research 57(4)

Competition in the Resale Market

This model extension examines the scenario in which the inte-

grated platform competes with an independent resale platform

in the resale market. This represents the situation in which

Ticketmaster competes with StubHub in the resale market. The