PAYCHECK

PROTECTION

PROGRAM

Program Changes

Increased Lending to

the Smallest

Businesses and in

Underserved

Locations

Report to Congressional Addressees

September 2021

GAO-21-601

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-21-601, a report to

congressional

addressees

September 2021

PAYCHECK PROTECTION PROGRAM

Program Changes

Increased Lending to the Smallest

Businesses and in Underserved

Locations

What GAO Found

The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) supports small businesses through

forgivable loans for payroll and other eligible costs. Early lending favored larger

and rural businesses, according to GAO’s analysis of Small Business

Administration (SBA) data. Specifically, 42 percent of Phase 1 loans (approved

from April 3–16, 2020) went to larger businesses (10 to 499 employees),

although these businesses accounted for only 4 percent of all U.S. small

businesses. Similarly, businesses in rural areas received 19 percent of Phase 1

loans but represented 13 percent of all small businesses. Banks made a vast

majority of Phase 1 loans.

In response to concerns that some underserved businesses—in particular,

businesses owned by self-employed individuals, minorities, women, and

veterans—faced challenges obtaining loans, Congress and SBA made a series

of changes that increased lending to these businesses. For example,

• SBA admitted about 600 new lenders to start lending in Phase 2 (which ran

from April 27–August 8, 2020), including nonbanks (generally, lending

institutions that do not accept deposits).

• SBA developed guidance after Phase 1 helping self-employed individuals

participate in the program.

• SBA targeted funding to minority-owned businesses in part through

Community Development Financial Institutions in Phases 2–3. (Phase 3 ran

from January 12–June 30, 2021.)

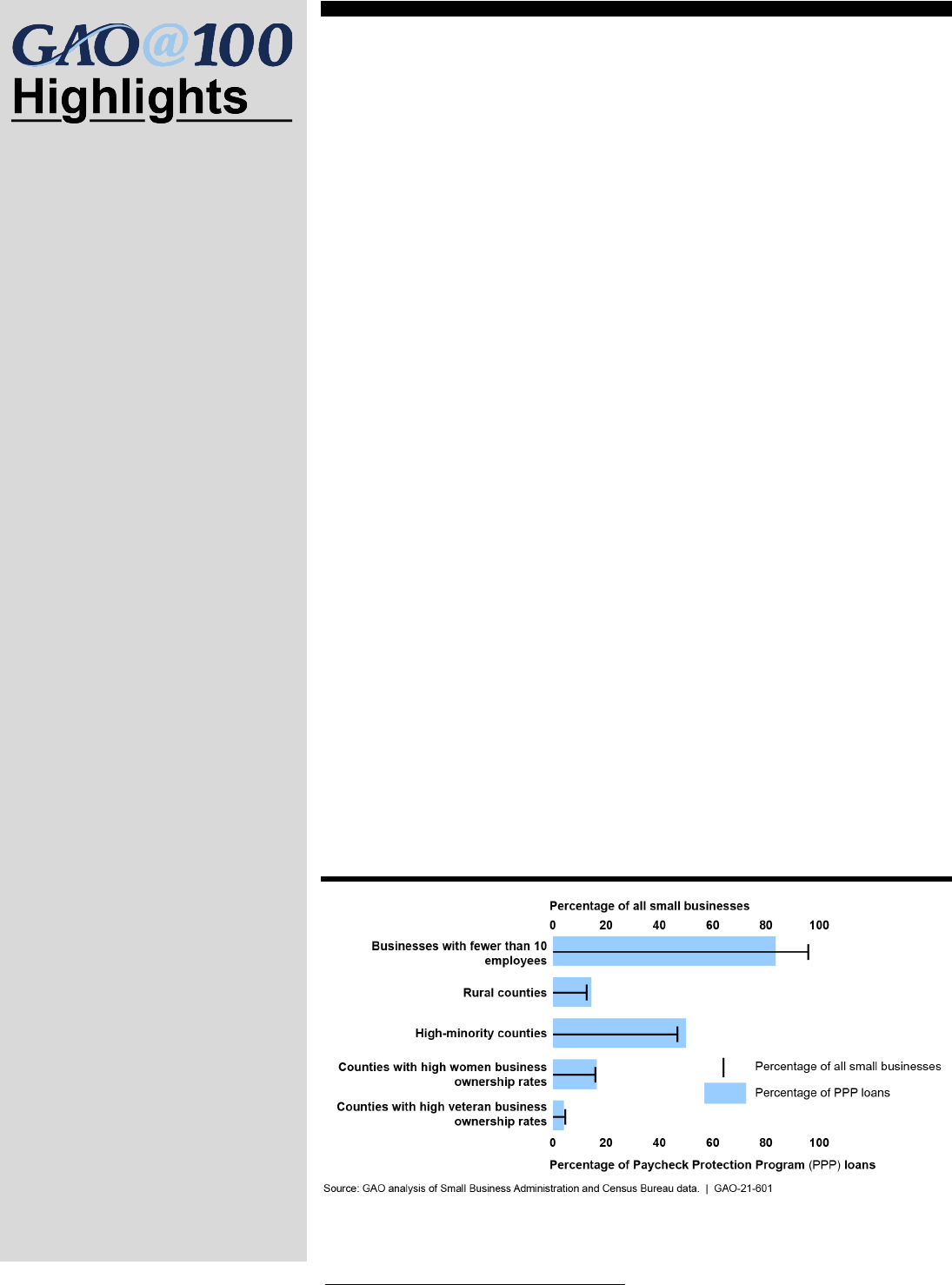

By the time PPP closed in June 2021, lending in traditionally underserved

counties was proportional to their representation in the overall small business

community (see figure). While lending to businesses with fewer than 10

employees remained disproportionately low, it increased significantly over the

course of the program.

Paycheck Protection Program Loans, by Type of Business or County

View GAO-21-601. For more information,

contact

John Pendleton at (202) 512-8678 or

.

Why GAO Did This Study

The COVID

-19 pandemic resulted in

significant turmoil in the U.S. economy,

leading to

temporary and permanent

business

closures and high

unemployment.

In response, in March

2020

, Congress established PPP

under the

CARES Act and ultimately

provided commitment authority of

approximately

$814 billion for the

program

over three phases. When

initial

program funding ran out in 14

days,

concerns quickly surfaced that

certain businesses were unable to

access the program

, prompting a

series of

changes by Congress and

SBA.

The CARES Act includes a provision

for GAO to moni

tor the federal

government’s efforts to respond to the

COVID

-19 pandemic. GAO has issued

a series of reports on this program,

and has made a number of

recommendations to improve program

performance and integrity.

This report

describes

trends in small business

and

lender

participation in PPP.

GAO

analyzed loan-level PPP data

from

SBA and county-level data from

four

U.S. Census Bureau products and

surveyed a

generalizable sample of

PPP lenders

, stratified by lender type

and size

. GAO also reviewed

legislation, interim final rules, agency

guidance, and relevant literature

, as

well as interviewed SBA officials

.

Page i GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Letter 1

Background 4

Program Changes Increased Lending to the Smallest Businesses

and in Underserved Locations 11

Agency Comments 34

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 40

Appendix II GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments 47

Tables

Table 1: Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Phases 5

Table 2: Key Paycheck Protection Program Changes, by Program

Phase 10

Table 3: Selected Paycheck Protection Program Changes 21

Figures

Figure 1: Paycheck Protection Program Lending Volume by

Approval Date, April 2020–June 2021 5

Figure 2: Overview of Paycheck Protection Program Lenders 7

Figure 3: Overview of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP)

Application Process 10

Figure 4: Percentage of First Draw Paycheck Protection Program

Loans to Larger Businesses Relative to Percentage of All

Small Businesses, by Program Phase 12

Figure 5: Paycheck Protection Program Loans per Small Business

in Phase 1, by County 14

Figure 6: Percentage of Paycheck Protection Program Recipients

Relative to the Percentage of All Small Businesses in the

Hardest-Hit Sectors 17

Figure 7: Number and Total Dollar Amount of Paycheck Protection

Program Loans Made in Phase 1, by Lender Type 18

Figure 8: Percentage of First Draw Paycheck Protection Program

Loans to Self-Employed Individuals, by Program Phase 22

Figure 9: Percentage of First Draw Paycheck Protection Program

Loans to Businesses in Counties with Large Shares of

Women-Owned Businesses, by Program Phase 24

Contents

Page ii GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Figure 10: Percentage of First Draw Paycheck Protection Program

Loans to Businesses in High-Minority Counties, by

Program Phase 26

Figure 11: Percentage of First Draw Paycheck Protection Program

Loans to Businesses in Metro Counties Relative to the

Percentage of All Small Businesses, by Program Phase

and Share of Minority Residents 28

Figure 12: Percentage of Paycheck Protection Program Loans, by

Lender Type and Program Phase 29

Figure 13: Percentage of Paycheck Protection Program Loans

Relative to the Share of Small Businesses, by Type of

Business or County 33

Abbreviations

CDFI Community Development Financial Institution

Census U.S. Census Bureau

COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019

MDI Minority Depository Institution

PPP Paycheck Protection Program

SBA Small Business Administration

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

September 21, 2021

Congressional Addressees

Congress passed the CARES Act in March 2020 in response to the

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

1

The CARES Act

provided more than $2 trillion in emergency assistance and health care

response for individuals, families, and businesses affected by COVID-19.

Stay-at-home orders, social distancing requirements, and reduced

consumer demand early in the pandemic caused both temporary and

permanent business closures, particularly among small businesses.

Congress included the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) in the

CARES Act, providing commitment authority of $349 billion to support

small businesses affected by the pandemic and to keep small business

workers employed.

2

Administered by the Small Business Administration (SBA) through a

network of participating lenders, PPP provided forgivable loans to small

businesses for payroll and certain other eligible costs. To provide relief

quickly, lenders began approving loans 7 days after the CARES Act was

enacted. When the program’s initial round of funding ran out in 14 days,

policy makers and small business organizations raised concerns that the

smallest businesses and those owned by minorities, women, and

veterans had difficulty accessing the program. In response, Congress

made program changes, renewed the program twice, and provided

approximately an additional $465 billion to meet continued demand.

1

Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020).

2

PPP was one of the programs Congress created, expanded, or funded under the CARES

Act to support workers and small businesses in the economic downturn. Congress also

eased borrowing requirements for the Economic Injury Disaster Loan program and

created and provided appropriations for Economic Injury Disaster Loan Advances. For

more information, see GAO, Economic Injury Disaster Loan Program: Additional Actions

Needed to Improve Communication with Applicants and Address Fraud Risk, GAO-21-589

(Washington, D.C.: July 30, 2021). In addition, the CARES Act created three federally

funded temporary unemployment insurance programs that expanded benefit eligibility and

enhanced benefits. This report does not assess the efficacy of PPP in addressing the

needs of small businesses during the pandemic, nor does it compare outcomes of

recipient businesses to nonrecipient businesses or businesses that utilized other small

business lending programs during the pandemic.

Letter

Page 2 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

The CARES Act includes a provision for us to monitor and oversee the

federal government’s efforts to prepare for, respond to, and recover from

COVID-19.

3

We have issued a series of reports on this program and

made a number of recommendations to improve program performance

and integrity. For example, in July 2021, we issued a report on the

safeguards SBA put in place during the PPP loan approval and

forgiveness processes and SBA’s oversight of PPP loans and lenders.

4

We also included emergency loans for small businesses—which include

PPP—as a new area on our High-Risk List in March 2021 because of the

potential for fraud, significant program integrity risks, and need for much

improved program management and oversight.

5

This report describes

how small business and lender participation in PPP evolved over time.

To describe how small business and lender participation in PPP evolved

over time, we analyzed loan-level PPP data from SBA for loans approved

from April 3, 2020, to June 30, 2021, and county-level data from four U.S.

Census Bureau (Census) products: the 2019 release of the American

Community Survey 5-year estimates; the 2018 Annual Business Survey;

the 2017 Nonemployer Statistics dataset; and the 2017 Statistics of U.S.

Businesses dataset. Specifically, we used PPP data to describe the size,

type, and sector of recipient businesses. Because SBA does not have

complete data on the race, gender, and veteran status of business

owners, we used Census data and estimates to describe the

demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of counties in which

recipient businesses were located.

6

To assess the reliability of the data

sources we used in our analyses, we primarily reviewed related

documentation. In some cases, we also interviewed agency officials and

3

We regularly issue government-wide reports on the federal response to COVID-19. For

the latest report, see GAO, COVID-19: Continued Attention Needed to Enhance Federal

Preparedness, Response, Service Delivery, and Program Integrity, GAO-21-551

(Washington, D.C.: July 19, 2021). Our next government-wide report will be issued in

October 2021 and will be available on GAO’s website at https://www.gao.gov/coronavirus.

4

See GAO, Paycheck Protection Program: SBA Added Program Safeguards, but

Additional Actions Are Needed, GAO-21-577 (Washington, D.C.: July 29, 2021).

5

See GAO, High Risk Series: Dedicated Leadership Needed to Address Limited Progress

in Most High-Risk Areas, GAO-21-119SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 2, 2021).

6

As we reported in July 2021, SBA did not require demographic information—for example,

the race, gender, and veteran status of the business owner—in the PPP borrower

application. However, SBA revised its PPP borrower application form in January 2021 to

allow for the optional disclosure of demographic information and included such a section

in all subsequent revisions and an optional demographic information form as part of the

PPP loan forgiveness application. See GAO-21-577.

Page 3 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

tested data for missing values and obvious errors. Because PPP

applicants self-certified the accuracy of the information they provided to

lenders and SBA, the reliability of the PPP data depends on the accuracy

of the information they provided. We determined the data sources we

used for our analyses were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of

describing small business and lender participation in PPP.

We did not assess PPP loans for fraud, and SBA officials told us they did

not flag fraudulent loans or remove them from the PPP dataset they

provided to us.

7

While the full extent of fraud in PPP is not yet known, as

of March 2021, the Department of Justice had announced charges in 134

cases involving 431 loans to borrowers who were charged with fraud

(such as bank fraud, wire fraud, or identity theft). Similarly, the SBA Office

of Inspector General found that, of the 5.2 million total loans made from

April 3 to August 9, 2020, lenders made more than one loan each to

4,260 borrowers and 57,473 loans to individuals on the Department of the

Treasury’s “Do Not Pay” list.

8

We also surveyed a generalizable sample of 1,383 PPP lenders, stratified

by lender type and size, to obtain their perspectives on the program.

9

We

administered the survey from February 2021 to April 2021 and received

781 responses. We obtained a weighted response rate of 57.3 percent.

10

Finally, we reviewed legislation, interim final rules, agency guidance, and

relevant literature, and we interviewed SBA officials. For more information

on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

7

SBA officials told us they track Department of Justice cases related to PPP and the

corresponding loans.

8

Small Business Administration, Office of Inspector General, Flash Report: Duplicate

Loans Made Under the Paycheck Protection Program, Report No. 21-09 (Washington,

D.C.: Mar. 15, 2021); and Management Alert: Paycheck Protection Program Loan

Recipients on the Department of Treasury’s Do Not Pay List, Report No. 21-06

(Washington, D.C.: Jan. 11, 2021).

9

We also used this survey to inform our July 2021 report on SBA’s implementation of PPP

(GAO-21-577). See app. I of that report for more details on the survey’s methodology and

app. II for the survey’s full results.

10

We used a weighted response rate because our survey sample incorporated strata with

different probabilities of selection. A weighted response rate may more accurately reflect

the level of participation. For example, large units that contribute relatively more to the

estimate of a total would have a larger “weight” on the response rate.

Page 4 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

We conducted this performance audit from July 2020 to September 2021

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

The CARES Act, signed into law by the President on March 27, 2020,

established PPP under section 7(a) of the Small Business Act to provide

forgivable loans to small businesses and nonprofit organizations, referred

to collectively as “small businesses.”

11

Under the law, qualifying

businesses (in general, these include businesses with 500 or fewer

employees or that meet SBA’s industry-based size standard) could obtain

loans equal to 2.5 months of average total monthly payments for payroll

costs up to $10 million, and were required to self-certify their need for the

loan.

12

When loan approvals ended in June 2021, Congress had provided

commitment authority of about $814 billion to PPP in three phases (see

table 1).

13

11

SBA administers the 7(a) guaranteed loan program, which provides small businesses

access to capital that they would not be able to access in the competitive market. In fiscal

year 2019, SBA approved $23 billion in loans through the 7(a) program.

12

As set forth in the CARES Act, borrowers had to certify in good faith that (1) current

economic uncertainty made the loan request necessary to support the applicant’s ongoing

operations and (2) funds would be used to retain workers and maintain payroll or make

payments for other covered expenses. Pub. L. No. 116-136, § 1102(a)(1)(B), 134 Stat.

281, 291 (2020) (codified at 15 U.S.C. § 636(a)(36)(G)(i)(I),(II)). To streamline the

process, SBA required minimal review from lenders—such as confirming receipt of

borrower certifications and supporting payroll documentation.

13

SBA’s loan-level PPP data included the date SBA approved the loan but not the date

the application was received. As a result, Phase 1 data include loans approved from April

3–16, 2020, Phase 2 data include loans approved from April 27–August 8, 2020, and

Phase 3 data include loans approved from January 12–June 30, 2021. The dataset

includes 10 loans with approval dates on April 20-22, 2020, which we categorized as

Phase 1, and one loan with an approval date of August 9, 2020, which we categorized as

Phase 2.

Background

PPP Commitment

Authority and Lending

Volume

Page 5 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Table 1: Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Phases

Phase

Legislation

Date enacted

Commitment authority

provided

Application period

1

CARES Act

March 27, 2020

$349 billion

April 3, 2020–April 16,

2020

2

Paycheck Protection Program and

Health Care Enhancement Act

April 24, 2020

$310 billion

April 27, 2020–August 8,

2020

3

Consolidated Appropriations Act,

2021

December 27, 2020

$147.45 billion

January 11, 2021–May

31, 2021

a

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021

March 11, 2021

$7.25 billion

Source: GAO analysis of relevant laws. | GAO-21-601

a

The PPP Extension Act of 2021 extended the application period for Phase 3 from March 31, 2021, to

May 31, 2021, and allowed the Small Business Administration until June 30, 2021, to process those

applications. On May 4, 2021, the PPP general fund was exhausted and closed to new applications,

except those processed by a community financial institution lender.

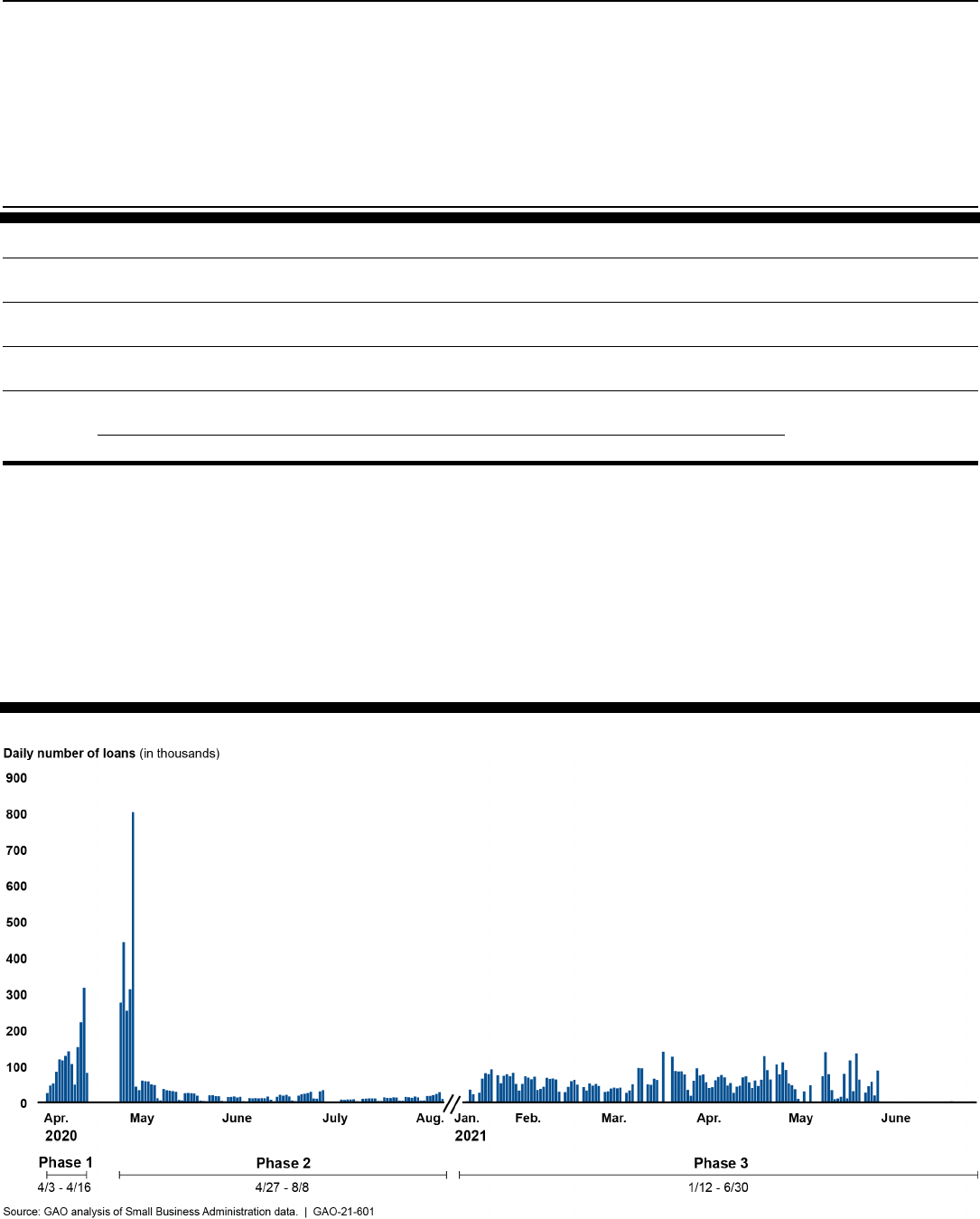

Early demand for PPP loans was high. Daily lending volume—that is, the

number of loans approved per day—was highest from April 3–May 1,

2020, when 31 percent of all PPP loans were approved (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Paycheck Protection Program Lending Volume by Approval Date, April 2020–June 2021

Page 6 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

The CARES Act authorized SBA to use lenders already approved to

participate in the 7(a) program and permitted SBA and Treasury to

approve new lenders to issue PPP loans, provided they met certain

requirements.

14

Participating lenders included depository institutions (for

example, banks and credit unions) and non-depository institutions (for

example, nonbanks) (see fig. 2).

15

For the purposes of this report, we

refer to depository institutions as “banks” and characterize them by size:

• large banks: total assets of $10 billion or more;

• medium banks: total assets from $1 billion to $10 billion; and

• small banks: total assets of less than $1 billion.

Further, some lenders are designated Community Development Financial

Institutions (CDFI) and Minority Depository Institutions (MDI). CFDIs and

MDIs target loans to businesses and individuals in traditionally

underserved areas with the goal of expanding economic opportunity.

CDFIs include both banks and nonbanks, while MDIs include only

banks.

16

14

Pub. L. No. 116-136, § 1102(a), 134 Stat. 281, 290 (2020) (codified at 15 U.S.C. §

636(a)(36)(F)(iii)). In an interim final rule published April 2, 2020, SBA announced that any

federally insured depository institution, credit union, or farm credit institution in good

standing with its regulator would automatically qualify to participate in PPP upon

submission of SBA’s PPP Lender Agreement. 85 Fed. Reg. 20,811, 20,815 (Apr. 15,

2020). SBA and the Department of the Treasury were jointly responsible for approving

lenders new to SBA to issue PPP loans. According to SBA officials, SBA approved new

federally regulated lenders, and only new non-federally regulated and insured lenders

required joint SBA and Treasury approval.

15

In general, nonbanks provide lending services but do not accept deposits. Nonbanks

include SBA Small Business Lending Companies, SBA Microlenders, SBA Certified

Development Companies, state-regulated financial companies, Business and Industrial

Development Corporations, and Farm Credit System lenders.

16

The Department of the Treasury administers the CDFI Fund, which certifies lenders as

CDFIs that share a common goal of expanding economic opportunity in low-income

communities by providing access to financial products and services for local residents and

businesses. MDIs are defined as depositories that (1) if a privately owned institution, 51

percent is owned by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals; (2) if publicly

owned, 51 percent of the stock is owned by socially and economically disadvantaged

individuals; and (3) in the case of a mutual institution where the majority of the board of

directors, account holders, and the community that the institution serves is predominantly

minority. The term “minority” means any Black American, Native American, Hispanic

American, or Asian American. 12 U.S.C. § 1463 note; 15 U.S.C. § 636(a)(36)(A)(xi)(II).

We assigned to the CDFI/MDI group all lenders SBA flagged as CDFIs, MDIs, or both,

and all remaining lenders to one of the other groups.

PPP Lenders

Page 7 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Figure 2: Overview of Paycheck Protection Program Lenders

Note: All lenders that the Small Business Administration (SBA) flagged as Minority Depository

Institutions, Community Development Financial Institutions, or both, were assigned to the Community

Development Financial Institutions/Minority Depository Institutions group, and all remaining lenders

were assigned to one of the other groups.

As PPP was initially implemented, small businesses or nonprofit

organizations were generally eligible for PPP loans if they had 500 or

PPP Borrowers

Page 8 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

fewer employees.

17

These businesses comprise approximately 99

percent of businesses of all sizes.

18

Businesses that may not have paid employees (sole proprietors,

independent contractors, self-employed individuals, qualified joint

ventures, and single-member limited liability companies) were eligible for

a PPP loan. For the purposes of this report, we refer to these business

types collectively as “self-employed individuals.” Based on the statutory

definition of payroll costs for self-employed individuals, the calculation of

loan amounts for these businesses differed from the calculations used by

other businesses, and the program requirements related to these

calculations changed over the course of the program.

19

We used information from the 2020 Bureau of Labor Statistics’s Business

Response Survey to identify six “hardest-hit sectors,” or sectors that were

most likely to experience adverse effects to business operations as a

result of the pandemic.

20

These six sectors are (1) accommodation and

food services; (2) arts, entertainment, and recreation; (3) educational

services; (4) health care; (5) manufacturing; and (6) retail trade.

21

Finally, the CARES Act included a Sense of the Senate statement noting

the Senate’s preference that SBA should issue guidance to lenders to

ensure that processing and disbursement of loans prioritizes businesses

in underserved and rural markets, including veterans and members of the

17

Under the CARES Act, eligible borrowers included: (1) businesses that are small under

SBA’s size standards (either the industry size standard or the alternative size standard);

(2) any business, 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, 501(c)(19) veterans organization, or

Tribal business concern with 500 or fewer employees or that meets the applicable SBA

industry size standard if more than 500; (3) any business in the accommodations and food

services sector that has more than one physical location and employs not more than 500

employees per physical location; and (4) sole proprietors, independent contractors, and

eligible self-employed individuals.

18

U.S. Census Bureau, Nonemployer Statistics, 2017; and Statistics of U.S. Businesses,

2017.

19

15 U.S.C. § 636(a)(36)(A)(viii)(I)(bb).

20

Adverse effects to business operations included a shortage of supplies or inputs,

decreased demand for products or services, difficulty moving or shipping goods, and

government-mandated closure of a business location.

21

Sector names refer to their classification codes within the North American Industry

Classification System, which is the standard used by federal statistical agencies in

classifying business establishments according to industry.

Page 9 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

military community, small business concerns owned and controlled by

socially and economically disadvantaged individuals, women, and

businesses in operation for less than 2 years.

22

For the purposes of this

report, we refer to “traditionally underserved businesses and counties”

more broadly as very small businesses; those owned by minorities,

women, or veterans; or those located in rural counties, counties with high

minority populations, or Tribal areas.

23

To apply for a PPP loan, potential borrowers first submitted applications

directly to a participating lender (see fig. 3). The lender then reviewed the

application documentation and submitted its loan approval decision to

SBA through SBA’s loan processing portal.

24

Once received, SBA issued

a loan number to the lender.

25

The lender then disbursed the loan amount

to the borrower.

22

Pub. L. No. 116-136, § 1102(a), 134 Stat. 281, 293 (2020) (codified at 15 U.S.C. §

636(a)(36)(P)(iv)).

23

In our analyses, we used businesses with fewer than 10 employees and those owned by

self-employed individuals to represent very small businesses. To represent minority-,

women-, and veteran-owned businesses, we used counties with high shares of minority

residents and high shares of women- and veteran-owned businesses. We include Tribal

areas when collectively referring to traditionally underserved counties.

24

SBA guidance stated that PPP was “first come, first served.” 85 Fed. Reg. 20,811,

20,813 (Apr. 15, 2020).

25

SBA issued a loan number when it agreed to guarantee the loan. Initially, SBA reviewed

loan and borrower information to look for duplicate applications before issuing a loan

number to the lender. For Phase 3, SBA began conducting upfront compliance checks

before issuing a loan number to the lender. For more information, see GAO-21-577.

Application and Lending

Processes

Page 10 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Figure 3: Overview of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Application Process

As the program continued, Congress and SBA made a series of changes

to PPP to increase lender participation and availability, target funding,

and modify loan calculations (see table 2). In addition, for Phase 3,

Congress allowed certain businesses that had already received a PPP

loan to receive a second loan, referred to throughout this report as

“second draw” loans.

Table 2: Key Paycheck Protection Program Changes, by Program Phase

Phase

Legislation or program

guidance and date

Description of change

1

Technical event (April 8, 2020)

The Small Business Administration (SBA) released the nonbank lender application form

allowing new nonbank lenders to participate in the Paycheck Protection Program

(PPP).

2

Interim final rule (April 20,

2020)

SBA provided instructions for self-employed individuals filing a Form 1040 Schedule C

to apply by calculating the loan amount based on the business’s net profit from 2019.

Guidance (April 23, 2020)

SBA issued clarifying guidance stating that public companies with access to capital

markets would be unlikely to have made a certification of need for a PPP loan in good

faith, and allowed companies 2 weeks to return loan funds if they applied for the loan

prior to the issuance of the guidance.

Interim final rule (April 30,

2020)

SBA adjusted portfolio requirements for Community Development Financial Institutions

(CDFI), majority minority-, women-, or veteran/military-owned financial institutions, and

certain other nonbank lenders, which allowed smaller lenders to participate in PPP.

Technical event (May 28,

2020)

SBA established a $10 billion set-aside for businesses that applied through CDFIs to

target lending to minority-owned businesses and underserved communities.

a

3

Consolidated Appropriations

Act, 2021 (December 27,

2020)

Congress allowed some businesses to receive a second loan and targeted eligibility for

second loans to businesses that met certain criteria, including having 300 or fewer

employees and documenting revenue losses in 2020.

Key Program Changes

Page 11 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Phase

Legislation or program

guidance and date

Description of change

Guidance (January 11, 2021)

SBA dedicated the first few days of Phase 3 to processing loans made through

community financial institutions, which include CDFIs, Minority Depository Institutions,

Certified Development Companies, and Microloan Intermediaries.

Guidance (February 22, 2021)

SBA established a 14-day loan application period exclusively for businesses or

nonprofits with fewer than 20 employees.

Interim final rule (March 4,

2021)

SBA revised the maximum loan amount calculation for self-employed individuals filing a

Form 1040 Schedule C based on either gross income or net profit, which allowed for

larger loans.

Source: GAO analysis of SBA guidance and relevant laws. | GAO-21-601.

Note: Phase 1 includes the application period from April 3–16, 2020, Phase 2 from April 27–August 8,

2020, and Phase 3 from January 11–May 31, 2021.

a

Congress established additional set-asides throughout the course of the program. These included a

total $60 billion set-aside for businesses that applied through community financial institutions, certain

small insured depository institutions, and certain small credit unions established under the Paycheck

Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act as well as $15 billion for lending by

community financial institutions and $35 billion to new first draw PPP borrowers established under the

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021.

PPP lending in Phase 1 of the program favored larger and rural

businesses, and banks made the vast majority of Phase 1 loans. Partly as

a result of program changes made by Congress and SBA, the share of

loans to most traditionally underserved businesses and counties we

analyzed substantially increased in Phases 2 and 3, and generally was

proportional to their representation in the overall small business

community when the program closed in June 2021.

Larger businesses. Larger businesses—small businesses with 10 to 499

employees—received a higher share of loans in Phase 1 relative to their

share of all small businesses. Specifically, 42 percent of loans in Phase 1

went to these larger businesses, despite accounting for only 4 percent of

all small businesses in the U.S. (see fig. 4). The share of first draw loans

to these businesses decreased over time, suggesting that much of their

demand for loans was met early in the program. Further, as we reported

in September 2020, during Phases 1–2, a larger share of loans over $2

Program Changes

Increased Lending to

the Smallest

Businesses and in

Underserved

Locations

Phase 1 Loans Flowed to

Larger Businesses and

Rural Areas Primarily

through Banks

Larger, Rural, and Certain

Hardest

-Hit Businesses

Received Early Loans

Page 12 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

million were canceled compared to smaller loans following reports that

publicly traded companies had received loans and SBA’s subsequent

guidance clarifying the economic necessity requirements. As a result, the

demand for larger loans may have diminished over time because of

increased scrutiny from the public, the Department of the Treasury, and

SBA.

26

Finally, because the loan amount for each recipient business was

based on average payroll, larger businesses generally received larger

loans, likely precipitating the exhaustion of Phase 1 funding after just 2

weeks.

27

Figure 4: Percentage of First Draw Paycheck Protection Program Loans to Larger

Businesses Relative to Percentage of All Small Businesses, by Program Phase

Note: Larger businesses are those with 10 to 499 employees. This analysis excludes loans that were

approved and subsequently canceled, and second draw loans. Generally, Phase 1 data include loans

approved from April 3–16, 2020, Phase 2 data include loans approved from April 27–August 8, 2020,

and Phase 3 data include loans approved from January 12–June 30, 2021.

26

GAO-20-701.

27

The average (median) loan size for recipient businesses with fewer than 10 employees

was $21,697 ($18,115), compared to $296,292 ($146,000) for recipient businesses with

10 to 499 employees.

Page 13 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Research on small business lending and PPP suggests businesses with

pre-existing relationships with banks were able to access PPP earlier

than businesses without such relationships. For example, one study on

PPP found that among businesses that applied for PPP loans from banks,

approval rates were generally higher for businesses with a pre-existing

relationship with a bank.

28

Also, larger businesses were more likely to

have these relationships than the smallest businesses.

29

Other research found that the smallest businesses were less aware of

PPP and less likely to apply early in the program.

30

If they did apply, the

smallest businesses applied later, faced longer processing times, and

were less likely to have their applications approved, which may also partly

explain why early lending skewed toward larger businesses during Phase

1.

Businesses in rural areas. Rural counties generally received a higher

number of loans per small business in Phase 1 than metro counties (see

fig. 5).

31

Additionally, while only 13 percent of small businesses are

28

Alexander W. Bartik et al., “The Targeting and Impact of Paycheck Protection Program

Loans to Small Businesses,” (working paper 27623, National Bureau of Economic

Research, July 2020). Additionally, as we found in GAO-21-577, because lenders were

required to apply relevant Bank Secrecy Act program requirements, they had to collect

additional information from PPP loan applicants with which they did not have a pre-

existing relationship. Because pre-existing clients required the lender to conduct less due

diligence, their applications could be processed more quickly. The Bank Secrecy Act

requires banks and other financial institutions to take precautions against money

laundering and other illicit financial activities by conducting due diligence activities and

informing the Department of the Treasury of suspicious activity by their customers.

29

According to the Federal Reserve Banks’ 2020 Small Business Credit Survey, larger

businesses (those with annual revenue greater than $1 million) were more likely to have

existing banking relationships. See Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta, Boston, Chicago,

Cleveland, Dallas, Kansas City, Minneapolis, New York, Philadelphia, Richmond, St.

Louis, and San Francisco, “Small Business Credit Survey: 2020 Report on Employer

Firms (New York, NY: 2020). The survey was conducted in the third and fourth quarters of

2019 and yielded 5,514 responses from small employer firms with one to 499 full or part-

time employees, in the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

30

Christopher Neilson, John Eric Humphries, and Gabriel Ulyssea. “Information Frictions

and Access to the Paycheck Protection Program,” (working paper 27624, National Bureau

of Economic Research, July 2020).

31

We used data from the Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service to

classify counties as “metro” if they have one or more high-density urban areas with 50,000

or more residents or are outlying counties that are economically tied to these central

counties, as measured by the share of workers commuting on a daily basis to the central

counties. Rural counties are outside the boundaries of metro areas and have no cities with

50,000 or more residents.

Page 14 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

located in rural counties, 19 percent of all Phase 1 loans went to

businesses in these counties.

Figure 5: Paycheck Protection Program Loans per Small Business in Phase 1, by County

Note: This analysis excludes loans that were approved and subsequently canceled. Generally, Phase

1 data include loans approved from April 3–16, 2020.

Page 15 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Businesses in rural counties also received loans earlier on average than

businesses in metro areas. Specifically, in the period from April 3–May 1,

2020, when loan volume was at its highest, loans were approved an

average of 3 days earlier for businesses in rural areas than loans for

businesses in metro areas.

Additionally, we found that businesses in rural counties collectively

received a higher share of loans in Phase 1 than the share of small

businesses in rural counties, even in high-minority rural counties and rural

counties with poorer socioeconomic outcomes.

32

More specifically,

businesses in rural counties received a high share of Phase 1 loans

potentially because many of their loans were approved by small banks,

which approved loans earlier than large banks. For example, of all loans

approved by small banks from April 3–May 1, 2020 (when daily approvals

were highest), 59 percent were approved before initial funding ran out on

April 16, 2020. Conversely, of all loans approved by large banks from

April 3–May 1, 2020, only 34 percent were approved before initial funding

ran out. In total, 44 percent of loans approved by small banks went to

businesses in rural areas compared to 6 percent of loans approved by

large banks.

Businesses in hardest-hit sectors. Collectively, businesses in the

hardest-hit sectors—accommodation and food services; arts,

entertainment, and recreation; educational services; health care;

manufacturing; and retail trade—received a higher share of loans early in

the program, as well as a high share of second draw loans in Phase 3,

than the share of small businesses in those sectors.

33

Specifically,

businesses in these sectors received 40 percent of loans in Phase 1, and

account for 27 percent of all small businesses nationwide. Moreover, like

32

For this analysis, we define minority counties as those in which the percentage of

minority residents was higher than the national share of 27.5 percent. To determine a

county’s socioeconomic status relative to the national estimate, we used five indicators:

median household income, unemployment rate, use of public assistance income, poverty

rate, and no internet access. Among all five indicators, small businesses in rural counties

with a county-level estimate worse than the national estimate still received a relatively high

share of loans compared to small businesses in those counties. Based on 2015–2019 5-

year estimates from Census’s American Community Survey data, median household

income was $62,843, the national unemployment rate was 5.3 percent, the national share

of households receiving public assistance income was 2.4 percent, the national poverty

rate was 12.9 percent, and the national share of households without internet access was

13.9 percent.

33

Based on our analysis of data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’s 2020 Business

Response Survey, businesses in these sectors were most likely to experience adverse

effects to their business operations as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Page 16 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

loans to larger businesses, the share of loans to businesses in hardest-hit

sectors declined over time, suggesting that demand for loans among

these businesses was met early in the program.

However, businesses in some of the hardest-hit sectors received a higher

share of loans than others. In particular, in Phase 1, businesses in the

retail trade, health care, accommodation and food services, and

manufacturing sectors received a higher share of loans relative to the

number of small businesses in those sectors (see fig. 6). Conversely,

businesses in the arts, entertainment, and recreation and educational

services sectors received a lower share of Phase 1 loans than the share

of small businesses in those sectors.

Businesses in the retail trade sector that received loans in Phase 1 were

more concentrated in rural areas, and businesses in the educational

services sector were less concentrated in rural areas than recipient

businesses overall. Because businesses in rural counties received a

higher share of Phase 1 loans than businesses in metro counties, location

may partly explain the higher share of early loans to businesses in the

retail trade sector and the lower share of early loans to businesses in the

educational services sector. Additionally, businesses in the

accommodation and food services, educational services, and

manufacturing sectors that received loans in Phase 1 were larger, on

average, than recipient businesses overall, which may further explain the

high share of loans to these sectors. Finally, researchers found that early

application rates were particularly high in the accommodation and retail

sectors, which likely resulted in higher rates of loans to businesses in

these sectors.

34

Businesses in the hardest-hit sectors also received a high share of

second draw loans (35 percent) in Phase 3 than the share of small

businesses in those sectors (27 percent), demonstrating their ongoing

demand for financial assistance as the pandemic continued. However, as

with early loans, businesses in certain hardest-hit sectors received a

higher share of second draw loans than others. Businesses in the health

care, accommodation and food services, and manufacturing sectors

received a relatively high share of second draw loans, while those in retail

34

Bartik et al., “The Targeting and Impact of Paycheck Protection Program Loans.”

Page 17 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

trade; arts, entertainment, and recreation; and educational services

sectors received a relatively low share.

35

Figure 6: Percentage of Paycheck Protection Program Recipients Relative to the

Percentage of All Small Businesses in the Hardest-Hit Sectors

Note: This analysis excludes loans that were approved and subsequently canceled. Generally, Phase

1 data include loans approved from April 3–16, 2020, and second draw applies to Phase 3 loans

(those approved from January 12–June 30, 2021).

35

Congress created two sector-specific SBA programs to target aid to venue operators

and food services businesses. The Shuttered Venue Operators Grant program,

established in 2020 by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, and amended by the

American Rescue Plan Act, includes over $16 billion in grants to shuttered venues. The

Restaurant Revitalization Fund, established in 2021 by the American Rescue Plan Act,

provides funding to restaurants and other food service establishments to compensate for

pandemic-related revenue losses. Businesses eligible for these programs generally fall

into the accommodation and food services and arts, entertainment, and recreation

sectors. Businesses that chose to receive both a PPP loan in Phase 3 and a Shuttered

Venue Operators Grant had the amount of their PPP loan deducted from their Shuttered

Venue Operators Grant award.

Page 18 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Banks collectively made more than 93 percent of all loans in Phase 1.

Large banks made 41 percent of loans (663,577 loans), medium banks

made 30 percent of loans (481,063 loans), and small banks made 23

percent of loans (366,030 loans) (see fig. 7). CDFIs and MDIs collectively

made 4 percent of loans (66,419 loans) and nonbank lenders made 3

percent of loans (42,112 loans).

36

When measuring lending activity by the

total dollar amount of loans made in Phase 1, the distribution among

large, medium, and small banks was similar.

Figure 7: Number and Total Dollar Amount of Paycheck Protection Program Loans

Made in Phase 1, by Lender Type

Note: For this analysis, all depository lenders are categorized as “banks,” including banks, credit

unions, and savings and loan associations. Large banks are as those with at least $10 billion in

36

As discussed later in this report, limited lending among CDFIs, MDIs, and nonbanks in

Phase 1 corresponded with low participation among certain traditionally underserved

businesses and counties during the same period.

Banks Made the Vast Majority

of Phase 1 Loans

Page 19 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

assets, medium banks are those with $1 to $10 billion, and small banks are those with less than $1

billion based on publicly available call reports. All nondepository lenders are categorized as

“nonbanks,” including SBA Small Business Lending Companies, SBA Certified Development

Companies, SBA Microlenders, Business and Industrial Development Corporations, Farm Credit

System lenders, and state-regulated financial companies. Generally, Phase 1 data include loans

approved from April 3–16, 2020.

Although large banks made more loans than all other lender types in

Phase 1, researchers found they underperformed compared to small

banks—with underperformance defined as having made a smaller share

of PPP loans relative to their share of non-PPP small business loans.

37

Further, bank performance affected whether PPP borrowers were able to

access loans before funding ran out at the end of Phase 1. Specifically,

only 25 percent of all PPP borrowers located in areas with

underperforming banks (regardless of size) obtained PPP approval prior

to the end of Phase 1. By contrast, approximately 42 percent of all PPP

borrowers in areas with banks that over-performed (or made more PPP

loans than their share of other small business loans) had access to funds

in Phase 1.

Small banks may have been more experienced with small business

lending, and therefore better equipped to process PPP applications than

other lenders, according to researchers and our analysis. For example,

research from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation found that

community banks (which are generally smaller banks) held a high share

of small business loans before the COVID-19 pandemic.

38

It also found

that community banks’ participation in PPP was proportionately larger

than their size in the banking industry, meaning that community banks

made a larger share of PPP loans than other types of loans. Further,

based on results from our survey of PPP lenders, small banks approved

the highest percentage of PPP applications on average (approximately 96

37

João Granja et al., “Did the Paycheck Protection Program Hit the Target?.” (working

paper 27095, National Bureau of Economic Research, November 2020).

38

Margaret Hanrahan and Angela Hilton, “The Importance of Community Banks in

Paycheck Protection Program Lending.” FDIC Quarterly, vol. 14, no. 4 (2020). For the

purposes of this research, community banks include banks with assets less than $1 billion,

banks that primarily engage in basic banking activities rather than specialty activities, and

banks that operate within a limited geographic scope.

Page 20 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

percent), compared to an estimated 93 percent for large and medium

banks, and an estimated 86 percent for CDFIs and MDIs.

39

Following concerns raised by small business associations that some

traditionally underserved businesses faced challenges accessing loans in

Phase 1, Congress and SBA modified PPP to increase participation

among certain businesses, such as self-employed individuals, women-

owned businesses, and businesses in minority counties.

40

These changes

included increasing the number of lenders in the program, targeting

funding and processing timeframes to certain businesses, and expanding

program eligibility (see table 3).

39

We surveyed a generalizable sample of 1,383 PPP lenders, stratified by lender type and

size, to obtain their perspectives on the program. The survey closed on April 15, 2021,

and we received 781 responses. We obtained a weighted response rate of 57.3 percent.

The 95 percent confidence intervals for these estimates are (95, 97) for small banks, (91,

94) for medium and large banks, and (84, 89) for CDFIs and MDIs.

40

Changes were also intended to target PPP lending to veteran-owned businesses. The

share of loans to businesses in counties with large shares of veteran-owned businesses

was generally consistent over time.

Program Changes,

Including Lender Pool

Expansion, Increased

Lending to Traditionally

Underserved Businesses

and Counties in Phases 2

and 3

Lending Increased to

Traditionally Underserved

Businesses and Counties

Page 21 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Table 3: Selected Paycheck Protection Program Changes

Type of change

Phase

Description of change

Lender participation

1

The Small Business Administration (SBA) released the nonbank lender application

form allowing new nonbank lenders to participate in the Paycheck Protection Program.

2

SBA adjusted portfolio requirements for Community Development Financial Institutions

(CDFI), majority minority-, women-, or veteran/military-owned financial institutions, and

certain other nonbank lenders, which allowed smaller lenders to participate in PPP.

Targeted funding and

processing timelines

2

SBA established a $10 billion set-aside for businesses that applied through CDFIs to

target lending to minority-owned businesses and traditionally underserved

communities.

a

3

SBA dedicated the first few days of Phase 3 to processing loans made through

community financial institutions, including CDFIs, Minority Depository Institutions,

Certified Development Companies, and Microloan Intermediaries. SBA also

established a 14-day loan application period exclusively for businesses or nonprofits

with fewer than 20 employees.

Expanded business eligibility

2

SBA issued a rule instructing self-employed individuals to apply by calculating the loan

amount based on the business’s net profit from 2019.

3

SBA revised the maximum loan amount calculation for self-employed individuals filing

a Form 1040 Schedule C based on either gross income or net profit, which allowed for

larger loans and enabled increased loan access for businesses with very little or

negative net profit.

Source: GAO analysis of SBA guidance. | GAO-21-601

Note: Phase 1 includes the application period from April 3–16, 2020, Phase 2 from April 27–August 8,

2020, and Phase 3 from January 11–May 31, 2021.

a

Congress established additional set-asides throughout the course of the program. These included a

$60 billion set-aside for businesses that applied through community financial institutions, certain small

depository institutions, and certain small credit unions established under the Paycheck Protection

Program and Health Care Enhancement Act as well as $15 billion for lending by community financial

institutions and $35 billion to new first draw PPP borrowers established under the Consolidated

Appropriations Act, 2021.

Self-employed individuals. While the share of loans to self-employed

individuals was low in Phase 1, program changes helped increase their

share substantially in later phases of the program. Specifically, loans to

self-employed individuals increased from 9 percent of all loans in Phase 1

to 86 percent in Phase 3 (see fig. 8).

41

This increase corresponded with

SBA issuing guidance for self-employed individuals to apply for loans and

increasing the number and types of lenders in the program at the end of

41

Census’s Statistics on U.S. Businesses includes data on the number of small

businesses based on characteristics including business size and industry sector, but it

does not include data on business ownership type that are comparable to SBA’s data on

PPP recipients. As a result, we were not able to provide information on the share of these

businesses relative to all small businesses in the U.S. The share of loans to businesses

with fewer than 10 employees also increased across all three phases.

Page 22 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Phase 1, and allowing for larger loan amounts for self-employed

individuals in Phase 3.

Figure 8: Percentage of First Draw Paycheck Protection Program Loans to Self-

Employed Individuals, by Program Phase

Note: Self-employed individuals include independent contractors, sole proprietorships qualified joint

ventures, and single-member limited liability companies. This analysis excludes loans that were

approved and subsequently canceled. Generally, Phase 1 data include loans approved from April 3–

16, 2020, Phase 2 data include loans approved from April 27–August 8, 2020, and Phase 3 data

include first draw loans approved from January 12–June 30, 2021. The U.S. Census Bureau’s

Statistics on U.S. Businesses does not include data on the share of these businesses relative to all

small businesses in the U.S.

Women-owned businesses. The share of loans to businesses in

counties with a large share of women-owned businesses also increased,

potentially because of Congress’s and SBA’s modifications related to

increasing lender participation and expanding business eligibility.

Because SBA does not have complete data on the gender of business

owners who obtained PPP loans, we used estimates from Census’s

Annual Business Survey to assess the extent to which businesses in

counties with large shares of women-owned businesses were able to

Page 23 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

access PPP.

42

For the purposes of this analysis, we examined lending in

counties with shares of women-owned businesses that were higher than

the national estimate.

43

We refer to these counties as having a “large

share” of women-owned businesses.

The share of loans to businesses in counties with large shares of women-

owned businesses doubled between Phase 1 and Phase 2, from 9

percent to 18 percent (see fig. 9).

44

This increase corresponded with the

increase in the number and types of lenders after Phase 1 and targeted

funding for traditionally underserved businesses and communities in

Phases 2 and 3. In addition, approximately 90 percent of women

business owners are self-employed individuals, according to Census

data.

45

As a result, program changes aimed at increasing participation

among self-employed individuals likely also contributed to the increase in

lending to counties with large shares of women-owned businesses.

42

As we reported in July 2021, SBA did not require demographic information—for

example, the race, gender, and veteran status of the business owner—in the PPP

borrower application. However, SBA revised its PPP borrower application form in January

2021 to allow for the optional disclosure of demographic information and included such a

section in all subsequent revisions and an optional demographic information form as part

of the PPP loan forgiveness application. See GAO-21-577. The Annual Business Survey

provides information on selected economic and demographic characteristics for employer

businesses (those with paid employees) and business owners by sex, ethnicity, race, and

veteran status. We used county-level data from 2017, the most recently available data at

the time of our review. While these data include employer businesses of all sizes, small

businesses comprise more than 99 percent of all businesses in the U.S., and therefore are

representative of small businesses.

43

For our analysis, we excluded counties whose estimated shares had a relative standard

error greater than 20 percent. We determined counties to be similar to the national

estimate if the 95 percent confidence interval surrounding their estimated share fell within

the 95 percent confidence interval surrounding the national share estimate. Based on data

from the 2017 Annual Business Survey, approximately 20 percent of all businesses were

women-owned.

44

Sixteen percent of all small businesses are located in counties with above-national

shares of women-owned businesses.

45

U.S. Census Bureau, Number of Women-Owned Employer Firms Increased 0.6% From

2017 to 2018 (Washington D.C.: Mar. 29, 2021).

Page 24 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Figure 9: Percentage of First Draw Paycheck Protection Program Loans to

Businesses in Counties with Large Shares of Women-Owned Businesses, by

Program Phase

Note: Counties with large shares of women-owned businesses include counties where the share of

women-owned businesses is higher than the national share at the 95 percent confidence level, based

on the U.S. Census Bureau’s Annual Business Survey data. This analysis excludes loans that were

approved and subsequently canceled and loans that could not be matched to data from the U.S.

Census Bureau. Generally, Phase 1 data include loans approved from April 3–16, 2020, Phase 2

data include loans approved from April 27–August 8, 2020, and Phase 3 data include first draw loans

approved from January 12–June 30, 2021. Sixteen percent of all small businesses are located in

counties with above-national shares of women-owned businesses.

Businesses in high-minority counties. Small businesses in counties

with a high share of minority residents (“high-minority counties”) received

a relatively low share of loans in Phase 1, but they experienced greater

access over time, potentially resulting from a number of program

changes.

46

Because SBA does not have complete data on the race of

business owners who obtained PPP loans, we used Census’s American

Community Survey to measure the percentage of loans in each phase

46

Forty-seven percent of all small businesses are located in high-minority counties.

Page 25 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

that went to businesses in high-minority counties, or counties with a share

of minority residents above the national share.

47

Based on our analysis, 36 percent of Phase 1 loans went to small

businesses located in high-minority counties, but this increased to 50

percent in Phase 2 (see fig. 10).

48

Similarly, researchers found that

businesses in high-minority counties received a lower share of Phase 1

loans than low-minority counties, but a higher share of Phase 2 loans.

49

This trend corresponds with a general increase in the number and types

of lenders in the program after Phase 1 and program changes to target

funds to lenders that lend in traditionally underserved counties in Phases

2 and 3. For example, in Phase 2, SBA established a $10 billion set-aside

for businesses that applied through CDFIs, seeking to target lending to

minority-owned businesses and traditionally underserved counties.

47

As we reported in July 2021, SBA did not require demographic information—for

example, the race, gender, and veteran status of the business owner—in the PPP

borrower application. However, SBA revised its PPP borrower application form in January

2021 to allow for the optional disclosure of demographic information and included such a

section in all subsequent revisions and an optional demographic information form as part

of the PPP loan forgiveness application. See GAO-21-577. The American Community

Survey is an ongoing survey of about 3.5 million U.S. households that uses a series of

monthly samples to produce annually updated estimates for census tracts across the U.S.

The survey collects data on the economic, social, housing, and demographic

characteristics of communities at various geographic levels, including metropolitan areas,

states, and counties. We used county-level 2015–2019 5-year estimates, the most

recently available data at the time of our review.

48

For this analysis, we define high-minority counties as counties where the percentage of

minority residents was higher than the national share of 27.5 percent.

49

This research used zip code-level data from Census’s County Business Patterns on

employer businesses to analyze PPP loans. R. Fairlie and F.M. Fossen, “Did the

Paycheck Protection Program and Economic Injury Disaster Loan Program get disbursed

to minority communities in the early stages of COVID-19?.” Small Business Economics

(2021).

Page 26 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Figure 10: Percentage of First Draw Paycheck Protection Program Loans to

Businesses in High-Minority Counties, by Program Phase

Note: High-minority counties were identified based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American

Community Survey and include counties with a share of minority residents greater than the national

share of 27.5 percent. This analysis excludes loans that were approved and subsequently canceled

and loans that could not be matched to the data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Generally, Phase 1

data include loans approved from April 3–16, 2020, Phase 2 data include loans approved from April

27–August 8, 2020, and Phase 3 data include first draw loans approved from January 12–June 30,

2021. Forty-seven percent of all small businesses are located in high-minority counties.

Loans to minority-owned businesses may also have been low in Phase 1

because these businesses lacked pre-existing relationships with banks,

particularly small banks. According to the Federal Reserve Banks’ 2019

Small Business Credit Survey, prior to the pandemic, Black and Hispanic

business owners were more likely to seek financing from large banks and

online lenders than from small banks.

50

The 2020 update to the survey

found this trend continued during Phases 1 and 2: regardless of where

businesses applied for PPP loans, those that had a relationship with a

50

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Small Business Credit Survey: 2019 Report on

Minority-Owned Firms (New York, NY: 2019). The 2018 survey was conducted in the third

and fourth quarters of 2018 and generated 6,614 responses from employer firms with

information on the race or ethnicity of a firm’s owner(s).

Page 27 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

bank were more likely to apply for PPP loans than those that did not.

51

The survey also demonstrated that minority-owned businesses were less

likely to have a relationship with a bank. Our survey of PPP lenders found

CDFIs and MDIs were more likely than other types of lenders to report

that they accepted applications from borrowers with whom they had no

prior relationship.

52

Additionally, when comparing high-minority counties by metro and rural

status, we found that businesses in high-minority metro counties were

underrepresented in Phase 1 relative to their share of total small

businesses, even in high-minority metro counties with better

socioeconomic outcomes. By contrast, businesses in low-minority metro

counties received a share of loans higher than their share of small

businesses in Phase 1 (see fig. 11). However, participation among

businesses in high-minority metro counties increased in Phases 2–3. This

suggests that program changes successfully targeted lending to

businesses in high-minority counties.

51

Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Kansas City,

Minneapolis, New York, Philadelphia, Richmond, St. Louis, and San Francisco, Small

Business Credit Survey: 2021 Report on Firms Owned by People of Color (New York, NY:

2021).

52

We surveyed a generalizable sample of 1,383 PPP lenders, stratified by lender type and

size, to obtain their perspectives on the program. The survey closed on April 15, 2021,

and we received 781 responses. We obtained a weighted response rate of 57.3 percent.

Ninety percent of CDFI/MDIs reported accepting PPP applications from businesses with

whom they had no prior relationship, compared to 73 percent of large banks. The 95

percent confidence interval for these estimates are (83, 95) for CDFI/MDIs and (67, 79) for

large banks.

Page 28 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

Figure 11: Percentage of First Draw Paycheck Protection Program Loans to

Businesses in Metro Counties Relative to the Percentage of All Small Businesses,

by Program Phase and Share of Minority Residents

Note: We used data from the Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service to classify

counties as “metro” if they have one or more high-density urban areas with 50,000 or more residents

or are outlying counties that are economically tied to these central counties, as measured by the

share of workers commuting on a daily basis to the central counties. Rural counties are outside the

boundaries of metro areas and have no cities with 50,000 or more residents. High-minority counties

were identified based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey and

include counties with a share of minority residents greater than the national share of 27.5 percent.

Forty-seven percent of all small businesses are located in high-minority counties. This analysis

excludes loans that were approved and subsequently canceled and loans that could not be matched

to the data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Generally, Phase 1 data include loans approved from April

3–16, 2020, Phase 2 data include loans approved from April 27–August 8, 2020, and Phase 3 data

include first draw loans approved from January 12–June 30, 2021.

To increase lending to traditionally underserved businesses and counties,

Congress and SBA modified PPP to include more lenders, particularly

Nonbanks, CDFIs, and MDIs

Substantially Increased

Lending in Later Phases

Page 29 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

those that lend to traditionally underserved businesses.

53

Nonbanks,

CDFIs, and MDIs each made a greater percentage of PPP loans in

Phases 2 and 3 (see fig. 12). Specifically, the percentage of loans made

by nonbanks increased significantly, from 3 percent of loans in Phase 1 to

23 percent of loans in Phase 3. In addition, the percentage of loans made

by CDFIs and MDIs rose from 4 percent of loans in Phase 1 to 24 percent

of loans in Phase 3. Further, beginning in Phase 2, SBA added 623 new

lenders to make PPP loans, increasing the total number of lenders from

4,837 to 5,460. CDFIs, MDIs, and nonbanks made 97 percent of the

nearly 1.5 million loans issued by new lenders in the last two phases of

the program.

Figure 12: Percentage of Paycheck Protection Program Loans, by Lender Type and

Program Phase

Note: For this analysis, all depository lenders are categorized as “banks,” including banks, credit

unions, and savings and loan associations. Large banks are as those with at least $10 billion in

assets, medium banks are those with $1 to $10 billion, and small banks are those with less than $1

billion based on publicly available call reports. All nondepository lenders are categorized as

“nonbanks,” including SBA Small Business Lending Companies, SBA Certified Development

Companies, SBA Microlenders, Business and Industrial Development Corporations, Farm Credit

53

SBA and the Department of the Treasury were jointly responsible for approving lenders

new to SBA to issue PPP loans. According to SBA officials, SBA approved new federally

regulated lenders, and only new non-federally regulated and insured lenders required joint

SBA and Treasury approval.

Page 30 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

System lenders, and state-regulated financial companies. This analysis excludes loans that were

approved and subsequently canceled. Generally, Phase 1 data include loans approved from April 3–

16, 2020, Phase 2 data include loans approved from April 27–August 8, 2020, and Phase 3 data

include first draw loans approved from January 12–June 30, 2021.

Nonbanks, CDFIs, and MDIs made a higher proportion of loans to

traditionally underserved businesses and counties than other types of

lenders, particularly small banks. Specifically, self-employed individuals

received 85 percent of nonbanks’ loans, but only 47 percent of loans

overall, which suggests that nonbank lenders’ increased participation over

time could have helped increase lending to these borrowers. In addition,

21 percent of loans made by CDFIs or MDIs and 23 percent of loans

made by nonbanks went to businesses in counties with large shares of

women-owned businesses, compared to 4 percent of loans made by

small banks.

54

Similarly, 64 percent of loans made by nonbanks and 69

percent of loans made by CDFIs and MDIs went to businesses in high-

minority counties, compared to 22 percent of loans made by small

banks.

55

These findings suggest the changes SBA and Congress made to

increase lending to traditionally underserved businesses through

nonbanks, CDFIs, and MDIs helped these businesses better access PPP.

By the end of Phase 3, PPP lending to businesses in traditionally

underserved counties was proportionate to their representation in the

overall small business community, in part because of the changes

Congress and SBA made to the program.

56

For example, while loans to

businesses in rural counties were high from the start of the program,

loans to businesses in high-minority counties and counties with large

shares of women-owned businesses reached proportionate levels by the

end of Phase 3. However, while lending to businesses with fewer than 10

54

By comparison, 19 percent of loans made by large banks and 10 percent of loans made

by medium banks went to businesses in counties with large shares of women-owned

businesses.

55

Fifty-four percent of loans made by large banks and 36 percent of loans made by

medium banks went to businesses in counties with high minority populations.

56

For the purposes of this report, we refer to “traditionally underserved businesses and

counties” more broadly as very small businesses; those owned by minorities, women, or

veterans; or those located in rural counties, counties with high minority populations, or

Tribal areas. In our analyses, we used businesses with fewer than 10 employees and

those owned by self-employed individuals to represent very small businesses. To

represent minority-, women-, and veteran-owned businesses, we used counties with high

shares of minority residents and high shares of women- and veteran-owned businesses.

We include Tribal areas when collectively referring to traditionally underserved counties.

By Program Close,

Lending in Traditionally

Underserved Counties

Was Comparable to Their

Share of Small

Businesses

Page 31 GAO-21-601 Paycheck Protection Program

employees increased significantly over time, it remained

disproportionately low by the end of Phase 3.

Specifically, the share of loans to businesses in rural counties exceeded

their share of all small businesses (see fig. 13). Overall, 15 percent of

loans went to small businesses in rural counties, while 13 percent of all

small businesses are located in these counties.

Despite initial access challenges, lending to high-minority counties

exceeded and lending to counties with large shares of women-owned

businesses reached their share of small businesses by the program’s

end. Businesses in high-minority counties received 50 percent of all loans

and account for 47 percent of all small businesses nationwide. Overall,

businesses in counties with large shares of women-owned businesses

accounted for 16 percent of loans and represent 16 percent of small

businesses. In addition, the share of loans to businesses in counties with

large shares of veteran-owned businesses was generally commensurate

with the share of small businesses in those counties. Overall, counties

with large shares of veteran-owned businesses accounted for 4 percent

of loans and 5 percent of small businesses.

Businesses across the hardest-hit sectors received 30 percent of all

program loans but account for 27 percent of small businesses.

However, the share of loans to businesses with fewer than 10 employees

remained below their share of small businesses overall, despite program