ACGME Program Requirements for

Graduate Medical Education

in Internal Medicine

Definitions

For more information, see the ACGME Glossary of Terms.

Core Requirements: Statements that define structure, resource, or process elements

essential to every graduate medical educational program.

Detail Requirements: Statements that describe a specific structure, resource, or

process, for achieving compliance with a Core Requirement. Programs and

sponsoring institutions in substantial compliance with the Outcome Requirements may

utilize alternative or innovative approaches to meet Core Requirements.

Outcome Requirements: Statements that specify expected measurable or observable

attributes (knowledge, abilities, skills, or attitudes) of residents or fellows at key stages

of their graduate medical education.

Osteopathic Recognition

For programs with or applying for Osteopathic Recognition, the Osteopathic Recognition

Requirements also apply (www.acgme.org/OsteopathicRecognition).

Revision Information

ACGME-approved Focused Revision: February 7, 2022; effective July 1, 2022

Updated to include revised Common Program Requirements, effective July 1, 2023

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 2 of 64

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3

Int.A. Definition of Graduate Medical Education ............................................................................ 3

Int.B. Definition of Specialty ........................................................................................................... 3

Int.C. Length of Educational Program ............................................................................................ 4

I. Oversight .............................................................................................................................. 5

I.A. Sponsoring Institution ............................................................................................................ 5

I.B. Participating Sites ................................................................................................................... 5

I.C. Workforce Recruitment and Retention ................................................................................. 6

I.D. Resources ................................................................................................................................ 6

I.E. Other Learners and Health Care Personnel ......................................................................... 8

II. Personnel ............................................................................................................................. 9

II.A. Program Director ..................................................................................................................... 9

II.B. Faculty .................................................................................................................................... 15

II.C. Program Coordinator ............................................................................................................ 22

II.D. Other Program Personnel .................................................................................................... 25

III. Resident Appointments .................................................................................................... 25

III.A. Eligibility Requirements ....................................................................................................... 25

III.B. Resident Complement .......................................................................................................... 26

III.C. Resident Transfers ................................................................................................................ 26

IV. Educational Program ......................................................................................................... 26

IV.A. Educational Components ..................................................................................................... 27

IV.B. ACGME Competencies ......................................................................................................... 28

IV.C. Curriculum Organization and Resident Experiences ........................................................ 34

IV.D. Scholarship ............................................................................................................................ 40

V. Evaluation ........................................................................................................................... 42

V.A. Resident Evaluation .............................................................................................................. 42

V.B. Faculty Evaluation ................................................................................................................ 45

V.C. Program Evaluation and Improvement ............................................................................... 46

VI. The Learning and Working Environment ........................................................................ 49

VI.A. Patient Safety, Quality Improvement, Supervision, and Accountability ......................... 50

VI.B. Professionalism..................................................................................................................... 53

VI.C. Well-Being .............................................................................................................................. 55

VI.D. Fatigue Mitigation ................................................................................................................. 57

VI.E. Clinical Responsibilities, Teamwork, and Transitions of Care ........................................ 58

VI.F. Clinical Experience and Education ..................................................................................... 59

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 3 of 64

ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education

in Internal Medicine

Common Program Requirements (Residency) are in BOLD

Where applicable, text in italics describes the underlying philosophy of the requirements in that

section. These philosophic statements are not program requirements and are therefore not

citable.

Introduction

Int.A. Definition of Graduate Medical Education

Graduate medical education is the crucial step of professional

development between medical school and autonomous clinical practice. It

is in this vital phase of the continuum of medical education that residents

learn to provide optimal patient care under the supervision of faculty

members who not only instruct, but serve as role models of excellence,

compassion, cultural sensitivity, professionalism, and scholarship.

Graduate medical education transforms medical students into physician

scholars who care for the patient, patient’s family, and a diverse

community; create and integrate new knowledge into practice; and educate

future generations of physicians to serve the public. Practice patterns

established during graduate medical education persist many years later.

Graduate medical education has as a core tenet the graded authority and

responsibility for patient care. The care of patients is undertaken with

appropriate faculty supervision and conditional independence, allowing

residents to attain the knowledge, skills, attitudes, judgment, and empathy

required for autonomous practice. Graduate medical education develops

physicians who focus on excellence in delivery of safe, equitable,

affordable, quality care; and the health of the populations they serve.

Graduate medical education values the strength that a diverse group of

physicians brings to medical care, and the importance of inclusive and

psychologically safe learning environments.

Graduate medical education occurs in clinical settings that establish the

foundation for practice-based and lifelong learning. The professional

development of the physician, begun in medical school, continues through

faculty modeling of the effacement of self-interest in a humanistic

environment that emphasizes joy in curiosity, problem-solving, academic

rigor, and discovery. This transformation is often physically, emotionally,

and intellectually demanding and occurs in a variety of clinical learning

environments committed to graduate medical education and the well-being

of patients, residents, fellows, faculty members, students, and all members

of the health care team.

Int.B. Definition of Specialty

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 4 of 64

Internists are specialists who care for adult patients through comprehensive,

clinical problem solving. They integrate the history, physical examination, and all

available data to deliver, direct, and coordinate care across varied clinical

settings, both in person and remotely through telemedicine. Internists are

diagnosticians who manage the care of patients who present with

undifferentiated, complex illnesses, and comorbidities; promote health and health

equity in communities; collaborate with colleagues; and lead, mentor, and serve

multidisciplinary teams. Internists integrate care across organ systems and

disease processes throughout the adult lifespan. They are expert

communicators, creative and adaptable to the changing needs of patients and

the health care environment. They advocate for their patients within the health

care system to achieve the patient’s and family’s care goals. Internists embrace

lifelong learning and the privilege and responsibility of educating patients,

populations, and other health professionals. The discipline is characterized by a

compassionate, cognitive, scholarly, relationship-oriented approach to

comprehensive patient care.

The successful, fulfilled internist maintains this core function and these core

values. Internists find meaning and purpose in caring for individual patients with

increased efficiency through well-functioning teams, and are equipped and

trained to manage change effectively and lead those teams. They understand

and manage the business of medicine to optimize cost-conscious care for their

patients. They apply data management science to population and patient

applications and help solve the clinical problems of their patients and their

community. Internists communicate fluently and are able to educate and clearly

explain complex data and concepts to all audiences, especially patients. They

collaborate with patients to implement health care ethics in all aspects of their

care. Internists display emotional intelligence in their relationships with

colleagues, team members, and patients, maximizing both their own and their

teams’ well-being. They are dedicated professionals who have the knowledge,

skills, and attitudes to effectively use all available resources, and bring

intellectual curiosity and human warmth to their patients and community.

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: The Review Committee developed this definition

to clearly articulate the core functions and values of internal medicine and describe what is

needed to move the specialty forward through program requirements. They express what

the Review Committee aspires to see in the graduates of internal medicine residency

programs, faculty members, and the broader internal medicine community.

Int.C. Length of Educational Program

An accredited residency program in internal medicine must provide 36 months of

supervised graduate medical education.

(Core)

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: While internal medicine residency must be

completed within a 36-month supervised educational framework (barring remediation and

extended leaves), the requirements were written to be flexible and allow program directors

the opportunity to create more individualized educational experiences for residents who have

achieved, or are on a trajectory to achieve, competence in the foundational areas of internal

medicine. This was a guiding principle for the revision process. The requirements for the

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 5 of 64

foundational areas of internal medicine and individualized educational experiences are

located in Section IV.C.: Curriculum Organization and Resident Experiences.

I. Oversight

I.A. Sponsoring Institution

The Sponsoring Institution is the organization or entity that assumes the

ultimate financial and academic responsibility for a program of graduate

medical education, consistent with the ACGME Institutional Requirements.

When the Sponsoring Institution is not a rotation site for the program, the

most commonly utilized site of clinical activity for the program is the

primary clinical site.

Background and Intent: Participating sites will reflect the health care needs of the

community and the educational needs of the residents. A wide variety of organizations

may provide a robust educational experience and, thus, Sponsoring Institutions and

participating sites may encompass inpatient and outpatient settings including, but not

limited to a university, a medical school, a teaching hospital, a nursing home, a school

of public health, a health department, a public health agency, an organized health care

delivery system, a medical examiner’s office, an educational consortium, a teaching

health center, a physician group practice, federally qualified health center, or an

educational foundation.

I.A.1. The program must be sponsored by one ACGME-accredited

Sponsoring Institution.

(Core)

I.B. Participating Sites

A participating site is an organization providing educational experiences or

educational assignments/rotations for residents.

I.B.1. The program, with approval of its Sponsoring Institution, must

designate a primary clinical site.

(Core)

I.B.1.a) The program, in partnership with its Sponsoring Institution, must

ensure that there is a reporting relationship between the internal

medicine subspecialty programs and the residency program

director.

(Core)

I.B.2. There must be a program letter of agreement (PLA) between the

program and each participating site that governs the relationship

between the program and the participating site providing a required

assignment.

(Core)

I.B.2.a) The PLA must:

I.B.2.a).(1) be renewed at least every 10 years; and,

(Core)

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 6 of 64

I.B.2.a).(2) be approved by the designated institutional official

(DIO).

(Core)

I.B.3. The program must monitor the clinical learning and working

environment at all participating sites.

(Core)

I.B.3.a) At each participating site there must be one faculty member,

designated by the program director as the site director, who

is accountable for resident education at that site, in

collaboration with the program director.

(Core)

Background and Intent: While all residency programs must be sponsored by a single

ACGME-accredited Sponsoring Institution, many programs will utilize other clinical

settings to provide required or elective training experiences. At times it is appropriate

to utilize community sites that are not owned by or affiliated with the Sponsoring

Institution. Some of these sites may be remote for geographic, transportation, or

communication issues. When utilizing such sites, the program must ensure the quality

of the educational experience.

Suggested elements to be considered in PLAs will be found in the Guide to the

Common Program Requirements. These include:

• Identifying the faculty members who will assume educational and supervisory

responsibility for residents

• Specifying the responsibilities for teaching, supervision, and formal evaluation

of residents

• Specifying the duration and content of the educational experience

• Stating the policies and procedures that will govern resident education during

the assignment

I.B.4. The program director must submit any additions or deletions of

participating sites routinely providing an educational experience,

required for all residents, of one month full time equivalent (FTE) or

more through the ACGME’s Accreditation Data System (ADS).

(Core)

I.C. Workforce Recruitment and Retention

The program, in partnership with its Sponsoring Institution, must engage in

practices that focus on mission-driven, ongoing, systematic recruitment

and retention of a diverse and inclusive workforce of residents, fellows (if

present), faculty members, senior administrative GME staff members, and

other relevant members of its academic community.

(Core)

Background and Intent: It is expected that the Sponsoring Institution has, and

programs implement, policies and procedures related to recruitment and retention of

individuals underrepresented in medicine and medical leadership in accordance with

the Sponsoring Institution’s mission and aims.

I.D. Resources

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 7 of 64

I.D.1. The program, in partnership with its Sponsoring Institution, must

ensure the availability of adequate resources for resident education.

(Core)

I.D.1.a) The program, in partnership with its Sponsoring institution, must:

I.D.1.a).(1) provide the broad range of facilities and clinical support

services necessary to provide comprehensive and timely

care of adult patients;

(Core)

I.D.1.a).(2) ensure that the program has adequate space available,

including meeting rooms, classrooms, examination rooms,

computers, visual and other educational aids, and office

space;

(Core)

I.D.1.a).(3) ensure that appropriate in-person or remote/virtual

consultations, including those done using

telecommunication technology, are available in settings in

which residents work;

(Core)

I.D.1.a).(4) provide access to an electronic health record; and,

(Core)

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: An electronic health record (EHR) can include

electronic notes, orders, and lab reporting. Such a system also facilitates data reporting

regarding the care provided to a patient or a panel of patients. It may also include systems for

enhancing the quality and safety of patient care. An EHR does not have to be present at all

participating sites and does not have to include every element of patient care information.

However, a system that simply reports laboratory or imaging results does not meet the

definition of an EHR.

I.D.1.a).(5) provide residents with access to training using simulation

to support resident education and patient safety.

(Core)

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: The Review Committee does not expect each

program to own a simulator or to have a simulation center. “Simulation” is used broadly to

mean learning about patient care in settings that do not include actual patients. This could

include objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs), standardized patients, patient

simulators, or electronic simulation of resuscitation, procedures, and other clinical scenarios.

I.D.1.b) The program must provide residents with a patient population

representative of both the broad spectrum of clinical disorders and

medical conditions managed by internists, and of the community

being served.

(Core)

I.D.2. The program, in partnership with its Sponsoring Institution, must

ensure healthy and safe learning and working environments that

promote resident well-being and provide for:

I.D.2.a) access to food while on duty;

(Core)

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 8 of 64

I.D.2.b) safe, quiet, clean, and private sleep/rest facilities available

and accessible for residents with proximity appropriate for

safe patient care;

(Core)

Background and Intent: Care of patients within a hospital or health system occurs

continually through the day and night. Such care requires that residents function at

their peak abilities, which requires the work environment to provide them with the

ability to meet their basic needs within proximity of their clinical responsibilities.

Access to food and rest are examples of these basic needs, which must be met while

residents are working. Residents should have access to refrigeration where food may

be stored. Food should be available when residents are required to be in the hospital

overnight. Rest facilities are necessary, even when overnight call is not required, to

accommodate the fatigued resident.

I.D.2.c) clean and private facilities for lactation that have refrigeration

capabilities, with proximity appropriate for safe patient care;

(Core)

Background and Intent: Sites must provide private and clean locations where residents

may lactate and store the milk within a refrigerator. These locations should be in close

proximity to clinical responsibilities. It would be helpful to have additional support

within these locations that may assist the resident with the continued care of patients,

such as a computer and a phone. While space is important, the time required for

lactation is also critical for the well-being of the resident and the resident's family, as

outlined in VI.C.1.c).(1).

I.D.2.d) security and safety measures appropriate to the participating

site; and,

(Core)

I.D.2.e)

accommodations for residents with disabilities consistent

with the Sponsoring Institution’s policy.

(Core)

I.D.3. Residents must have ready access to specialty-specific and other

appropriate reference material in print or electronic format. This

must include access to electronic medical literature databases with

full text capabilities.

(Core)

I.E. Other Learners and Health Care Personnel

The presence of other learners and other health care personnel, including

but not limited to residents from other programs, subspecialty fellows, and

advanced practice providers, must not negatively impact the appointed

residents’ education.

(Core)

Background and Intent: The clinical learning environment has become increasingly

complex and often includes care providers, students, and post-graduate residents and

fellows from multiple disciplines. The presence of these practitioners and their

learners enriches the learning environment. Programs have a responsibility to monitor

the learning environment to ensure that residents’ education is not compromised by

the presence of other providers and learners.

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 9 of 64

II. Personnel

II.A. Program Director

II.A.1. There must be one faculty member appointed as program director

with authority and accountability for the overall program, including

compliance with all applicable program requirements.

(Core)

II.A.1.a) The Sponsoring Institution’s GMEC must approve a change in

program director and must verify the program director’s

licensure and clinical appointment.

(Core)

Background and Intent: While the ACGME recognizes the value of input from

numerous individuals in the management of a residency, a single individual must be

designated as program director and have overall responsibility for the program. The

program director’s nomination is reviewed and approved by the GMEC.

II.A.1.b) The program must demonstrate retention of the program

director for a length of time adequate to maintain continuity

of leadership and program stability.

(Core)

Background and Intent: The success of residency programs is generally enhanced by

continuity in the program director position. The professional activities required of a

program director are unique and complex and take time to master. All programs are

encouraged to undertake succession planning to facilitate program stability when

there is necessary turnover in the program director position.

II.A.2. The program director and, as applicable, the program’s leadership

team, must be provided with support adequate for administration of

the program based upon its size and configuration.

(Core)

II.A.2.a) At a minimum, the program director must be provided with the

dedicated time and support specified below for administration of

the program:

(Core)

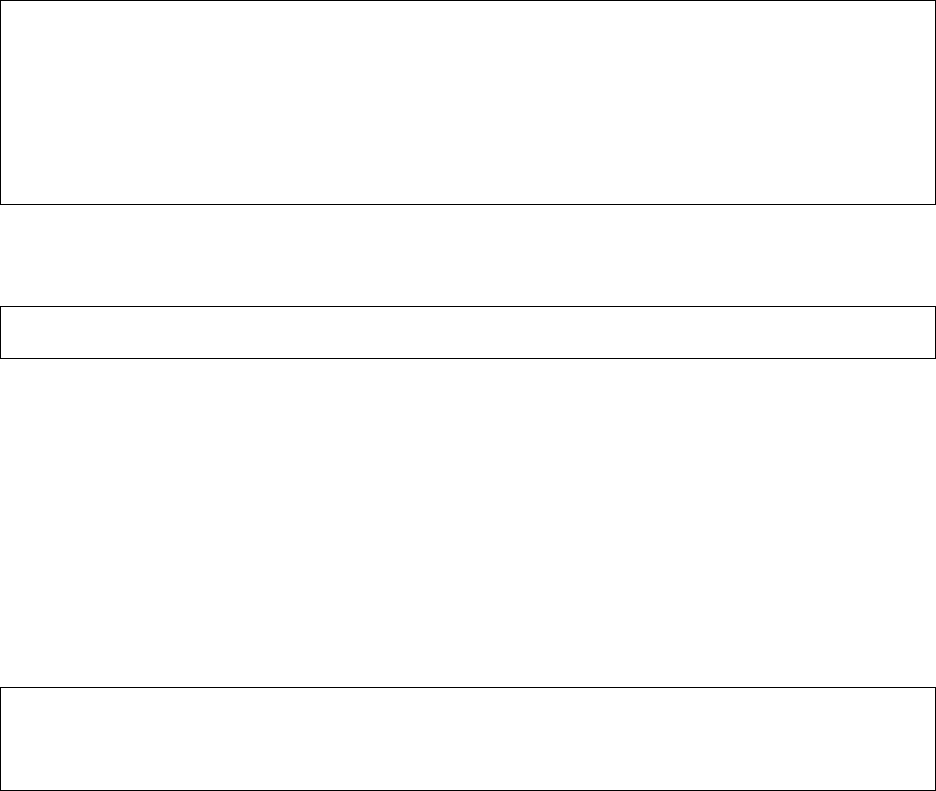

Number of Approved

Resident Positions

Minimum Support

Required (FTE)

<7

0.2

7-10

0.4

>10

0.5

II.A.2.b) Programs with more than 15 residents must appoint an associate

program director(s). The associate program director(s) must be

provided with support equal to a dedicated minimum time for

administration of the program as follows:

(Core)

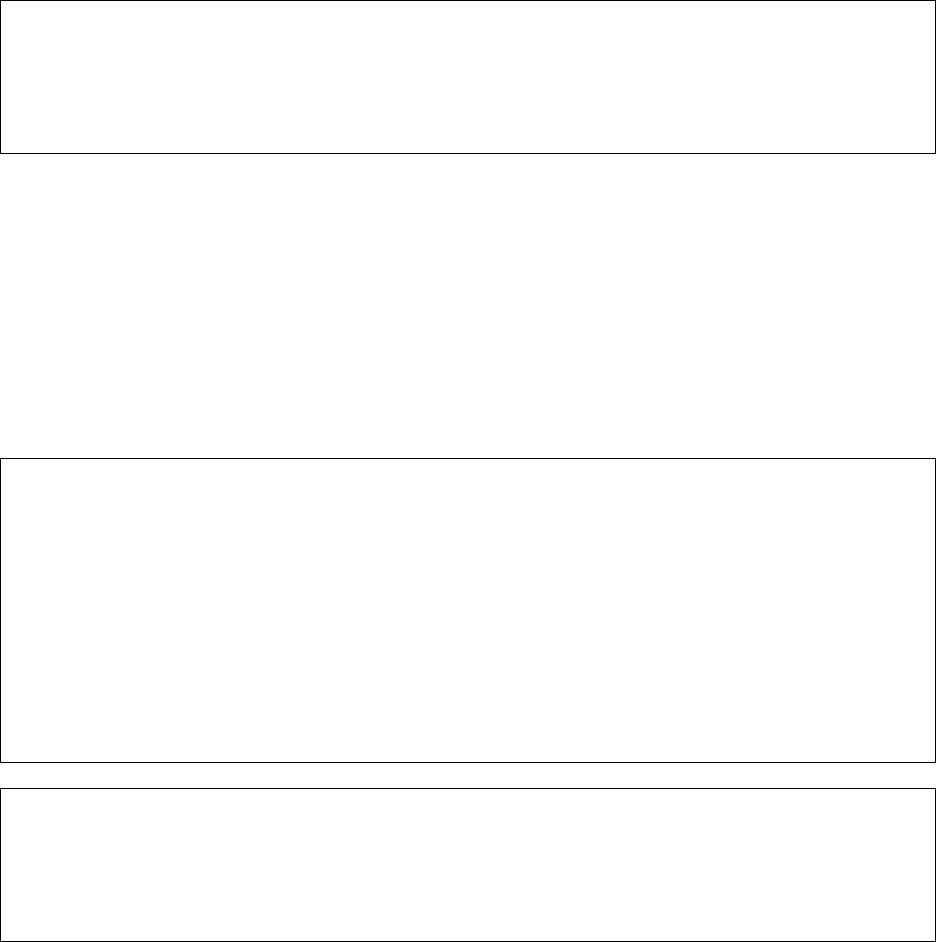

Number of Approved

Resident Positions

Minimum Support

Required (FTE)

<15

0

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 10 of 64

Number of Approved

Resident Positions

Minimum Support

Required (FTE)

16-20

0.1

21-25

0.2

26-30

0.3

31-35

0.4

36-40

0.5

41-45

0.6

46-50

0.7

51-55

0.8

56-60

0.9

61-65

1.0

66-70

1.1

71-75

1.2

76-80

1.3

81-85

1.4

86-90

1.5

91-95

1.6

96-100

1.7

101-105

1.8

106-110

1.9

111-115

2.0

116-120

2.1

121-125

2.2

126-130

2.3

131-135

2.4

136-140

2.5

141-145

2.6

146-150

2.7

151-155

2.8

156-160

2.9

161-165

3.0

166-170

3.1

171-175

3.2

176-180

3.3

181-185

3.4

186-190

3.5

191-195

3.6

196-200

3.7

201-205

3.8

206-210

3.9

211-215

4.0

216-220

4.1

221-225

4.2

226-230

4.3

Background and Intent: To achieve successful graduate medical education, individuals

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 11 of 64

serving as education and administrative leaders of residency programs, as well as

those significantly engaged in the education, supervision, evaluation, and mentoring of

residents, must have sufficient dedicated professional time to perform the vital

activities required to sustain an accredited program.

The ultimate outcome of graduate medical education is excellence in resident

education and patient care.

The program director and, as applicable, the program leadership team, devote a

portion of their professional effort to the oversight and management of the residency

program, as defined in II.A.4.-II.A.4.a).(12). Both provision of support for the time

required for the leadership effort and flexibility regarding how this support is provided

are important. Programs, in partnership with their Sponsoring Institutions, may provide

support for this time in a variety of ways. Examples of support may include, but are not

limited to, salary support, supplemental compensation, educational value units, or

relief of time from other professional duties.

Program directors and, as applicable, members of the program leadership team, who

are new to the role may need to devote additional time to program oversight and

management initially as they learn and become proficient in administering the

program. It is suggested that during this initial period the support described above be

increased as needed.

In addition, it is important to remember that the dedicated time and support

requirement for ACGME activities is a minimum, recognizing that, depending on the

unique needs of the program, additional support may be warranted. The need to

ensure adequate resources, including adequate support and dedicated time for the

program director, is also addressed in Institutional Requirement II.B.1. The amount of

support and dedicated time needed for individual programs will vary based on a

number of factors and may exceed the minimum specified in the applicable

specialty/subspecialty-specific Program Requirements. It is expected that the

Sponsoring Institution, in partnership with its accredited programs, will ensure support

for program directors to fulfill their program responsibilities effectively.

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: For instance, a program with an approved

complement of 36 residents is required to have 50% FTE support for the program director

and 50 percent FTE support for the associate program director(s). The Review Committee

decided not to specify how the support should be distributed among associate program

directors to allow programs, in partnership with their sponsoring institution, to allocate the

support as they see fit. Further, the program could redistribute the FTE back to the program

director; for example, in this instance, the associate program director(s) could receive 25

percent FTE support and the program director could receive 75 percent FTE support (50

percent plus the remaining 25 percent from the associate program director FTE support).

II.A.3. Qualifications of the program director:

II.A.3.a) must include specialty expertise and at least three years of

documented educational and/or administrative experience, or

qualifications acceptable to the Review Committee;

(Core)

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 12 of 64

Background and Intent: Leading a program requires knowledge and skills that are

established during residency and subsequently further developed. The time period

from completion of residency until assuming the role of program director allows the

individual to cultivate leadership abilities while becoming professionally established.

The three-year period is intended for the individual's professional maturation.

The broad allowance for educational and/or administrative experience recognizes that

strong leaders arise through diverse pathways. These areas of expertise are important

when identifying and appointing a program director. The choice of a program director

should be informed by the mission of the program and the needs of the community.

In certain circumstances, the program and Sponsoring Institution may propose and the

Review Committee may accept a candidate for program director who fulfills these

goals but does not meet the three-year minimum.

II.A.3.b) must include current certification in the specialty for which

they are the program director by the American Board of

Internal Medicine (ABIM) or by the American Osteopathic

Board of Internal Medicine (AOBIM), or specialty qualifications

that are acceptable to the Review Committee;

(Core)

II.A.3.b).(1) The Review Committee only accepts current certification in

internal medicine from the ABIM or AOBIM.

(Core)

II.A.3.c) must include ongoing clinical activity.

(Core)

Background and Intent: A program director is a role model for faculty members and

residents. The program director must participate in clinical activity consistent with the

specialty. This activity will allow the program director to role model the Core

Competencies for the faculty members and residents.

II.A.3.d) must have experience working as part of an interdisciplinary, inter-

professional team to create an educational environment that

promotes high-quality care, patient safety, and resident well-being.

(Core)

II.A.4. Program Director Responsibilities

The program director must have responsibility, authority, and

accountability for: administration and operations; teaching and

scholarly activity; resident recruitment and selection, evaluation,

and promotion of residents, and disciplinary action; supervision of

residents; and resident education in the context of patient care.

(Core)

II.A.4.a) The program director must:

II.A.4.a).(1) be a role model of professionalism;

(Core)

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 13 of 64

Background and Intent: The program director, as the leader of the program, must serve

as a role model to residents in addition to fulfilling the technical aspects of the role. As

residents are expected to demonstrate compassion, integrity, and respect for others,

they must be able to look to the program director as an exemplar. It is of utmost

importance, therefore, that the program director model outstanding professionalism,

high quality patient care, educational excellence, and a scholarly approach to work.

The program director creates an environment where respectful discussion is welcome,

with the goal of continued improvement of the educational experience.

II.A.4.a).(2) design and conduct the program in a fashion

consistent with the needs of the community, the

mission(s) of the Sponsoring Institution, and the

mission(s) of the program;

(Core)

Background and Intent: The mission of institutions participating in graduate medical

education is to improve the health of the public. Each community has health needs that

vary based upon location and demographics. Programs must understand the structural

and social determinants of health of the populations they serve and incorporate them

in the design and implementation of the program curriculum, with the ultimate goal of

addressing these needs and eliminating health disparities.

II.A.4.a).(3) administer and maintain a learning environment

conducive to educating the residents in each of the

ACGME Competency domains;

(Core)

Background and Intent: The program director may establish a leadership team to

assist in the accomplishment of program goals. Residency programs can be highly

complex. In a complex organization, the leader typically has the ability to delegate

authority to others, yet remains accountable. The leadership team may include

physician and non-physician personnel with varying levels of education, training, and

experience.

II.A.4.a).(4) have the authority to approve or remove physicians

and non-physicians as faculty members at all

participating sites, including the designation of core

faculty members, and must develop and oversee a

process to evaluate candidates prior to approval;

(Core)

Background and Intent: The provision of optimal and safe patient care requires a team

approach. The education of residents by non-physician educators may enable the

resident to better manage patient care and provides valuable advancement of the

residents’ knowledge. Furthermore, other individuals contribute to the education of

residents in the basic science of the specialty or in research methodology. If the

program director determines that the contribution of a non-physician individual is

significant to the education of the residents, the program director may designate the

individual as a program faculty member or a program core faculty member.

II.A.4.a).(5) have the authority to remove residents from

supervising interactions and/or learning environments

that do not meet the standards of the program;

(Core)

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 14 of 64

Background and Intent: The program director has the responsibility to ensure that all

who educate residents effectively role model the Core Competencies. Working with a

resident is a privilege that is earned through effective teaching and professional role

modeling. This privilege may be removed by the program director when the standards

of the clinical learning environment are not met.

There may be faculty in a department who are not part of the educational program, and

the program director controls who is teaching the residents.

II.A.4.a).(6) submit accurate and complete information required

and requested by the DIO, GMEC, and ACGME;

(Core)

Background and Intent: This includes providing information in the form and format

requested by the ACGME and obtaining requisite sign-off by the DIO.

II.A.4.a).(7) provide a learning and working environment in which

residents have the opportunity to raise concerns,

report mistreatment, and provide feedback in a

confidential manner as appropriate, without fear of

intimidation or retaliation;

(Core)

II.A.4.a).(8) ensure the program’s compliance with the Sponsoring

Institution’s policies and procedures related to

grievances and due process, including when action is

taken to suspend or dismiss, or not to promote or

renew the appointment of a resident;

(Core)

Background and Intent: A program does not operate independently of its Sponsoring

Institution. It is expected that the program director will be aware of the Sponsoring

Institution’s policies and procedures, and will ensure they are followed by the

program’s leadership, faculty members, support personnel, and residents.

II.A.4.a).(9) ensure the program’s compliance with the Sponsoring

Institution’s policies and procedures on employment

and non-discrimination;

(Core)

II.A.4.a).(9).(a) Residents must not be required to sign a non-

competition guarantee or restrictive covenant.

(Core)

II.A.4.a).(10) document verification of education for all residents

within 30 days of completion of or departure from the

program;

(Core)

II.A.4.a).(11) provide verification of an individual resident’s

education upon the resident’s request, within 30 days;

and,

(Core)

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 15 of 64

Background and Intent: Primary verification of graduate medical education is

important to credentialing of physicians for further training and practice. Such

verification must be accurate and timely. Sponsoring Institution and program policies

for record retention are important to facilitate timely documentation of residents who

have previously completed the program. Residents who leave the program prior to

completion also require timely documentation of their summative evaluation.

II.A.4.a).(12) provide applicants who are offered an interview with

information related to their eligibility for the relevant

specialty board examination(s).

(Core)

II.B. Faculty

Faculty members are a foundational element of graduate medical education

– faculty members teach residents how to care for patients. Faculty

members provide an important bridge allowing residents to grow and

become practice-ready, ensuring that patients receive the highest quality of

care. They are role models for future generations of physicians by

demonstrating compassion, commitment to excellence in teaching and

patient care, professionalism, and a dedication to lifelong learning. Faculty

members experience the pride and joy of fostering the growth and

development of future colleagues. The care they provide is enhanced by

the opportunity to teach and model exemplary behavior. By employing a

scholarly approach to patient care, faculty members, through the graduate

medical education system, improve the health of the individual and the

population.

Faculty members ensure that patients receive the level of care expected

from a specialist in the field. They recognize and respond to the needs of

the patients, residents, community, and institution. Faculty members

provide appropriate levels of supervision to promote patient safety. Faculty

members create an effective learning environment by acting in a

professional manner and attending to the well-being of the residents and

themselves.

Background and Intent: “Faculty” refers to the entire teaching force responsible for

educating residents. The term “faculty,” including “core faculty,” does not imply or

require an academic appointment.

II.B.1. There must be a sufficient number of faculty members with

competence to instruct and supervise all residents.

(Core)

II.B.1.a) Faculty members with credentials appropriate to the care setting

must supervise all clinical experiences.

(Core)

II.B.1.a).(1) There must be physicians with certification in internal

medicine by the ABIM or AOBIM to teach and supervise

internal medicine residents while they are on internal

medicine inpatient and outpatient rotations.

(Core)

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 16 of 64

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: The Review Committee believes the best role

models for internal medicine residents are internal medicine physicians with certification in

internal medicine from the ABIM or AOBIM. Providing such faculty members ensures

specialty-specific educators with significant experience managing and providing

comprehensive patient care to complex patients. However, the Review Committee recognizes

there are circumstances and clinical settings in which a non-internist who has been approved

by the program director would be an appropriate supervisor. Examples include but are not

limited to the following:

• On inpatient medicine ward rotations, it is appropriate for an ABFM- or AOBFP- certified

physician with extensive experience in caring for inpatient adults to teach and supervise

internal medicine residents, provided they are approved by the site director and the

program director. Working as an adult hospitalist for at least three years would be one

way to demonstrate such extensive experience.

• On inpatient medicine rotations in the critical care setting, it would be appropriate for a

non-internist who has been approved by the program director and the medical intensive

care unit director to teach and supervise internal medicine residents. For example, it

would be appropriate for emergency medicine physicians with certification in internal

medicine-critical care medicine to supervise internal medicine residents on critical care

medicine rotations. It is also appropriate for physicians with certification in critical care

from other disciplines to teach and supervise in limited circumstances, such as evening or

weekend cross-coverage.

• On outpatient medicine rotations/experiences, it is appropriate for a non-internist with

documented expertise (e.g., a family medicine physician with extensive

outpatient/ambulatory experience or procedural proficiency) to teach and supervise

internal medicine residents provided the non-internist is approved by the site director and

the program director.

II.B.1.a).(2) Physicians certified by the ABIM or the AOBIM in the

relevant subspecialty must be available to teach and

supervise internal medicine residents while they are on

internal medicine subspecialty rotations.

(Core)

II.B.1.a).(3) Physicians certified by an ABMS or AOA board in the

relevant subspecialty should be available to teach and

supervise internal medicine residents while they are on

multidisciplinary subspecialty rotations.

(Core)

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: For example, it would be appropriate for a faculty

member certified in geriatric medicine by the ABIM, AOBIM, American Board of Family

Medicine, or American Osteopathic Board of Family Medicine to teach and supervise internal

medicine residents on geriatric medicine rotations.

II.B.1.a).(4) Physicians certified by an ABMS or AOA board in the

relevant specialty should be available to teach and

supervise internal medicine residents while they are having

non-internal medicine experiences.

(Core)

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: For example, it would be appropriate for a faculty

member certified in neurology by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology or the

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 17 of 64

American Osteopathic Board of Neurology and Psychiatry to teach and supervise internal

medicine residents on neurology rotations.

II.B.2. Faculty members must:

II.B.2.a) be role models of professionalism;

(Core)

II.B.2.b) demonstrate commitment to the delivery of safe, equitable,

high-quality, cost-effective, patient-centered care;

(Core)

Background and Intent: Patients have the right to expect quality, cost-effective care

with patient safety at its core. The foundation for meeting this expectation is formed

during residency and fellowship. Faculty members model these goals and continually

strive for improvement in care and cost, embracing a commitment to the patient and

the community they serve.

II.B.2.c) demonstrate a strong interest in the education of residents,

including devoting sufficient time to the educational program

to fulfill their supervisory and teaching responsibilities;

(Core)

II.B.2.d) administer and maintain an educational environment

conducive to educating residents;

(Core)

II.B.2.e) regularly participate in organized clinical discussions,

rounds, journal clubs, and conferences; and,

(Core)

II.B.2.f) pursue faculty development designed to enhance their skills

at least annually:

(Core)

Background and Intent: Faculty development is intended to describe structured

programming developed for the purpose of enhancing transference of knowledge, skill,

and behavior from the educator to the learner. Faculty development may occur in a

variety of configurations (lecture, workshop, etc.) using internal and/or external

resources. Programming is typically needs-based (individual or group) and may be

specific to the institution or the program. Faculty development programming is to be

reported for the residency program faculty in the aggregate.

II.B.2.f).(1) as educators and evaluators;

(Detail)

II.B.2.f).(2) in quality improvement, eliminating health inequities,

and patient safety;

(Detail)

II.B.2.f).(3) in fostering their own and their residents’ well-being;

and,

(Detail)

II.B.2.f).(4) in patient care based on their practice-based learning

and improvement efforts.

(Detail)

Background and Intent: Practice-based learning serves as the foundation for the

practice of medicine. Through a systematic analysis of one’s practice and review of the

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 18 of 64

literature, one is able to make adjustments that improve patient outcomes and care.

Thoughtful consideration to practice-based analysis improves quality of care, as well

as patient safety. This allows faculty members to serve as role models for residents in

practice-based learning.

II.B.2.g) There must be a subspecialty education coordinator (SEC) in

each of the subspecialties of internal medicine and in the

multidisciplinary subspecialty of geriatric medicine.

(Core)

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: An SEC is necessary in each of the following

subspecialties of internal medicine: cardiovascular disease; critical care medicine;

endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism; gastroenterology; hematology; infectious disease;

nephrology; medical oncology; pulmonary disease; and rheumatology.

II.B.2.g).(1) Each SEC must be accountable to the program director for

coordination of all educational experiences in the

subspecialty area.

(Core)

II.B.2.g).(2) Each SEC must be certified in the relevant subspecialty by

the ABIM or the AOBIM, except that the geriatric medicine

SEC must be certified in the subspecialty by the relevant

ABMS member board or AOA certifying board.

(Core)

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: SECs are responsible for developing the

educational content and curriculum for the subspecialty area. An associate program director

or core faculty member can also function as an SEC with adequate additional administrative

resources. Double-boarded SECs can act as education coordinators for two specialties (e.g.,

hematology-medical oncology and pulmonary disease-critical care medicine). The SEC for

geriatric medicine can be certified by the ABIM, the AOBIM, the American Board of Family

Medicine, or the American Osteopathic Board of Family Medicine. The Review Committee

encourages programs that cannot identify an SEC for a particular subspecialty area to

consider the option of sharing one with a program that does have one. The SEC can be

remotely located and associated with multiple residency programs.

II.B.2.h) There must be faculty members with expertise in the analysis and

interpretation of practice data, data management science and

clinical decision support systems, and managing emerging health

issues.

(Core)

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: Advances in technology are likely to significantly

impact and redefine patient care, and this requirement is intended to ensure that residents

are provided with access to faculty members with knowledge, skills, or experience in the

analysis and interpretation of practice data, and who are able to analyze and evaluate the

validity of decisions from advanced data management and clinical decision support systems.

Faculty members with expertise in this area can be physicians or non-physicians, core or

non-core faculty members. Institutions may already have such experts assisting programs in

meeting the Common Program Requirement to systematically analyze practice data to

improve patient care [IV.B.1.d).(1).(d)]. The Review Committee encourages programs that

cannot identify an existing internal candidate with expertise in this area to consider the option

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 19 of 64

of sharing one with a program that does. The faculty member can be remotely located and

associated with multiple residency programs.

II.B.2.i) Faculty members must have experience working in

interdisciplinary, interprofessional team-based health care delivery

models.

(Core)

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: The Review Committee believes that

interdisciplinary, interprofessional, team-based care is the foundation of care delivery.

Individuals working within such teams are essential to resident education.

II.B.3. Faculty Qualifications

II.B.3.a) Faculty members must have appropriate qualifications in

their field and hold appropriate institutional appointments.

(Core)

II.B.3.b) Physician faculty members must:

II.B.3.b).(1) have current certification in the specialty by the

American Board of Internal Medicine or the American

Osteopathic Board of Internal Medicine, or possess

qualifications judged acceptable to the Review

Committee.

(Core)

II.B.4. Core Faculty

Core faculty members must have a significant role in the education

and supervision of residents and must devote a significant portion

of their entire effort to resident education and/or administration, and

must, as a component of their activities, teach, evaluate, and

provide formative feedback to residents.

(Core)

Background and Intent: Core faculty members are critical to the success of resident

education. They support the program leadership in developing, implementing, and

assessing curriculum, mentoring residents, and assessing residents’ progress toward

achievement of competence in and the autonomous practice of the specialty. Core

faculty members should be selected for their broad knowledge of and involvement in

the program, permitting them to effectively evaluate the program. Core faculty

members may also be selected for their specific expertise and unique contribution to

the program. Core faculty members are engaged in a broad range of activities, which

may vary across programs and specialties. Core faculty members provide clinical

teaching and supervision of residents, and also participate in non-clinical activities

related to resident education and program administration. Examples of these non-

clinical activities include, but are not limited to, interviewing and selecting resident

applicants, providing didactic instruction, mentoring residents, simulation exercises,

completing the annual ACGME Faculty Survey, and participating on the program’s

Clinical Competency Committee, Program Evaluation Committee, and other GME

committees.

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 20 of 64

II.B.4.a) Core faculty members must complete the annual ACGME

Faculty Survey.

(Core)

II.B.4.b) In addition to the program director and associate program

director(s), programs must have the minimum number of ABIM- or

AOBIM-certified core faculty members based on the number of

approved resident positions, as follows.

(Core)

II.B.4.c) At a minimum, the required core faculty members, in aggregate

and excluding program leadership, must be provided with support

equal to an average dedicated minimum of 0.1 FTE for

educational and administrative responsibilities that do not involve

direct patient care.

(Core)

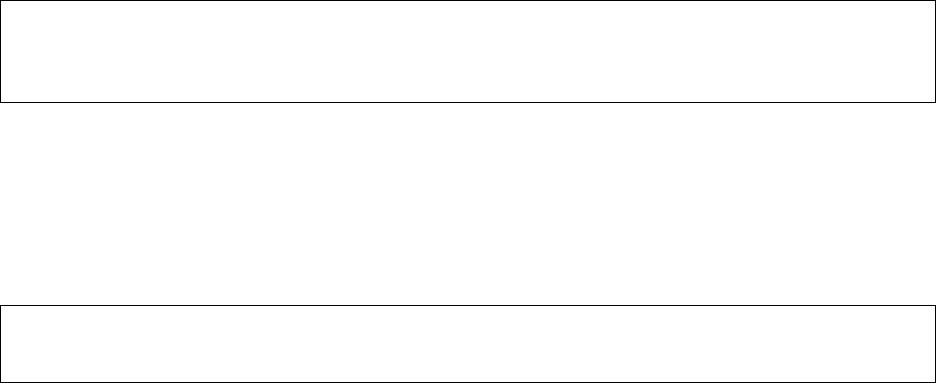

Number of Approved

Resident Positions

Minimum Number of

ABIM- or AOBIM-

certified Core Faculty

Members

<30

3

30-39

4

40-49

5

50-59

6

60-69

7

70-79

8

80-89

9

90-99

10

100-109

11

110-119

12

120-129

13

130-139

14

140-149

15

150-159

16

160-169

17

170-179

18

180-189

19

190-199

20

200-209

21

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: The Review Committee specified the minimum

required number of ABIM- or AOBIM-certified internal medicine core faculty, but did not

specify how the aggregate FTE support should be distributed to allow programs, in

partnership with their sponsoring institution, to allocate the support as they see fit. For

instance, a program with an approved complement of 36 residents is required to have a

minimum of four ABIM- or AOBIM-certified core faculty members and a minimum aggregate

FTE of 40 percent. The program could choose to operationalize this as four ABIM- or AOBIM-

certified faculty members each with 10 percent FTE support, but it could also have eight

members each with five percent FTE support, or one member with twenty percent FTE and

four members with five percent each.

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 21 of 64

The duties of the program director, associate program director(s), and internal medicine core

faculty members are separate and distinct. As such, the minimum required internal medicine

core faculty members are in addition to the program director and the associate program

director(s). One individual cannot “count” as both an associate program director and internal

medicine core faculty member.

The requirement related to support for core internal medicine faculty members is intended to

ensure these faculty members have sufficient protected time to meet the following

educational responsibilities:

• Membership on the Clinical Competency Committee

• Participation in the annual program review as Chair or member of the Program

Evaluation Committee

• Implementation and analysis of the outcome of action plans developed by the

Program Evaluation Committee

• Significant participation in recruitment and selection, including efforts related to the

program’s commitment to diversity

• Advising, mentoring, and coaching residents (co-creating, implementing, and

monitoring individualized learning plans)

• Designing and overseeing remediation plans

• Supporting/overseeing residents in the development/assessment of quality

improvement/patient safety projects

• Supporting/overseeing residents in the conduct of their scholarly work, including the

dissemination of such work through presentations, posters/abstracts, and peer-

reviewed publications

• Significant participation in educational activities (didactics, lab, or simulation)

• Overseeing faculty development for the program’s faculty members

• Designing and implementing simulation and/or standardized patients for teaching and

assessment

• Developing, implementing, and assessing one or more of the major components of the

curriculum, such as patient safety, quality, health disparities, or core didactics

• Designing and implementing the program’s assessment strategies, making certain

there are robust methods used to assess each competency, and ensuring they

provide meaningful information by which the Clinical Competency Committee can

judge resident performance on the Milestones

• Leading the program’s efforts related to resident and faculty member well-being

Each core faculty member does not need to participate in every listed educational

responsibility.

Background and Intent: Provision of support for the time required for the core faculty

members’ responsibilities related to resident education and/or administration of the

program, as well as flexibility regarding how this support is provided, are important.

Programs, in partnership with their Sponsoring Institutions, may provide support for

this time in a variety of ways. Examples of support may include, but are not limited to,

salary support, supplemental compensation, educational value units, or relief of time

from other professional duties.

It is important to remember that the dedicated time and support requirement is a

minimum, recognizing that, depending on the unique needs of the program, additional

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 22 of 64

support may be warranted. The need to ensure adequate resources, including

adequate support and dedicated time for the core faculty members, is also addressed

in Institutional Requirement II.B.2. The amount of support and dedicated time needed

for individual programs will vary based on a number of factors and may exceed the

minimum specified in the applicable specialty-/ subspecialty-specific Program

Requirements.

II.B.5. Associate Program Directors

Associate program directors assist the program director in the

administrative and clinical oversight of the educational program.

II.B.5.a) Associate program directors must:

II.B.5.a).(1) have current certification from the ABIM or AOBIM in either

internal medicine or a subspecialty of internal medicine;

(Core)

II.B.5.a).(2) report directly to the program director;

(Core)

II.B.5.a).(3) participate in academic societies and in educational

programs designed to enhance their educational and

administrative skills; and,

(Core)

II.B.5.a).(4) take an active role in curriculum development, resident

teaching and evaluation, continuous program

improvement, and faculty development.

(Core)

II.C. Program Coordinator

II.C.1. There must be a program coordinator.

(Core)

II.C.2. The program coordinator must be provided with dedicated time and

support adequate for administration of the program based upon its

size and configuration.

(Core)

II.C.2.a) At a minimum, the program coordinator must be provided with the

dedicated time and support specified below for administration of

the program. Additional administrative support must be provided

based on the program size as follows:

(Core

)

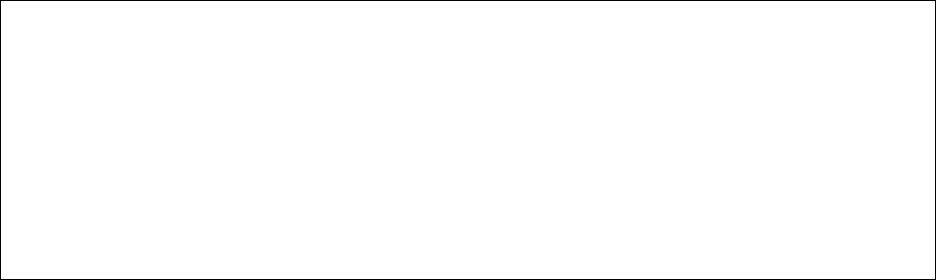

Number of Approved

Resident Positions

Minimum FTE Required

for Coordinator Support

Additional Aggregate FTE

Required for Administration

of the Program

<7

0.5

0

7-10

0.5

0.2

10-15

0.5

0.3

16-20

0.5

0.4

21-25

0.5

0.5

26-30

0.5

0.6

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 23 of 64

Number of Approved

Resident Positions

Minimum FTE Required

for Coordinator Support

Additional Aggregate FTE

Required for Administration

of the Program

31-35

0.5

0.7

36-40

0.5

0.8

41-45

0.5

0.9

46-50

0.5

1.0

51-55

0.5

1.1

56-60

0.5

1.2

61-65

0.5

1.3

66-70

0.5

1.4

71-75

0.5

1.5

76-80

0.5

1.6

81-85

0.5

1.7

86-90

0.5

1.8

91-95

0.5

1.9

96-100

0.5

2.0

101-105

0.5

2.1

106-110

0.5

2.2

111-115

0.5

2.3

116-120

0.5

2.4

121-125

0.5

2.5

126-130

0.5

2.6

131-135

0.5

2.7

136-140

0.5

2.8

141-145

0.5

2.9

146-150

0.5

3.0

151-155

0.5

3.1

156-160

0.5

3.2

161-165

0.5

3.3

166-170

0.5

3.4

171-175

0.5

3.5

176-180

0.5

3.6

181-185

0.5

3.7

186-190

0.5

3.8

191-195

0.5

3.9

196-200

0.5

4.0

201-205

0.5

4.1

206-210

0.5

4.2

211-215

0.5

4.3

216-220

0.5

4.4

221-225

0.5

4.5

226-230

0.5

4.6

Background and Intent: The requirement does not address the source of funding

required to provide the specified salary support.

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 24 of 64

Each program requires a lead administrative person, frequently referred to as a

program coordinator, administrator, or as otherwise titled by the institution. This

person will frequently manage the day-to-day operations of the program and serve as

an important liaison and facilitator between the learners, faculty and other staff

members, and the ACGME. Individuals serving in this role are recognized as program

coordinators by the ACGME.

The program coordinator is a key member of the leadership team and is critical to the

success of the program. As such, the program coordinator must possess skills in

leadership and personnel management appropriate to the complexity of the program.

Program coordinators are expected to develop in-depth knowledge of the ACGME and

Program Requirements, including policies and procedures. Program coordinators

assist the program director in meeting accreditation requirements, educational

programming, and support of residents.

Programs, in partnership with their Sponsoring Institutions, should encourage the

professional development of their program coordinators and avail them of

opportunities for both professional and personal growth. Programs with fewer

residents may not require a full-time coordinator; one coordinator may support more

than one program.

The minimum required dedicated time and support specified in II.C.2.a) is inclusive of

activities directly related to administration of the accredited program. It is understood

that coordinators often have additional responsibilities, beyond those directly related

to program administration, including, but not limited to, departmental administrative

responsibilities, medical school clerkships, planning lectures that are not solely

intended for the accredited program, and mandatory reporting for entities other than

the ACGME. Assignment of these other responsibilities will necessitate consideration

of allocation of additional support so as not to preclude the coordinator from devoting

the time specified above solely to administrative activities that support the accredited

program.

In addition, it is important to remember that the dedicated time and support

requirement for ACGME activities is a minimum, recognizing that, depending on the

unique needs of the program, additional support may be warranted. The need to

ensure adequate resources, including adequate support and dedicated time for the

program coordinator, is also addressed in Institutional Requirement II.B.4. The amount

of support and dedicated time needed for individual programs will vary based on a

number of factors and may exceed the minimum specified in the applicable

specialty/subspecialty-specific Program Requirements. It is expected that the

Sponsoring Institution, in partnership with its accredited programs, will ensure support

for program coordinators to fulfill their program responsibilities effectively.

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: For instance, a program with an approved

complement of 36 residents is required to have 130 percent FTE for coordinator support. The

Review Committee decided not to specify how the support should be distributed to allow

programs, in partnership with their Sponsoring Institution, to allocate the support as they see

fit.

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 25 of 64

II.D. Other Program Personnel

The program, in partnership with its Sponsoring Institution, must jointly

ensure the availability of necessary personnel for the effective

administration of the program.

(Core)

Background and Intent: Multiple personnel may be required to effectively administer a

program. These may include staff members with clerical skills, project managers,

education experts, and staff members to maintain electronic communication for the

program. These personnel may support more than one program in more than one

discipline.

III. Resident Appointments

III.A. Eligibility Requirements

III.A.1. An applicant must meet one of the following qualifications to be

eligible for appointment to an ACGME-accredited program:

(Core)

III.A.1.a) graduation from a medical school in the United States or

Canada, accredited by the Liaison Committee on Medical

Education (LCME) or graduation from a college of

osteopathic medicine in the United States, accredited by the

American Osteopathic Association Commission on

Osteopathic College Accreditation (AOACOCA); or,

(Core)

III.A.1.b) graduation from a medical school outside of the United

States or Canada, and meeting one of the following additional

qualifications:

(Core)

III.A.1.b).(1) holding a currently valid certificate from the

Educational Commission for Foreign Medical

Graduates (ECFMG) prior to appointment; or,

(Core)

III.A.1.b).(2) holding a full and unrestricted license to practice

medicine in the United States licensing jurisdiction in

which the ACGME-accredited program is located.

(Core)

III.A.2. All prerequisite post-graduate clinical education required for initial

entry or transfer into ACGME-accredited residency programs must

be completed in ACGME-accredited residency programs, AOA-

approved residency programs, Royal College of Physicians and

Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC)-accredited or College of Family

Physicians of Canada (CFPC)-accredited residency programs

located in Canada, or in residency programs with ACGME

International (ACGME-I) Advanced Specialty Accreditation.

(Core)

III.A.2.a) Residency programs must receive verification of each

resident’s level of competency in the required clinical field

using ACGME, CanMEDS, or ACGME-I Milestones evaluations

from the prior training program upon matriculation.

(Core)

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 26 of 64

Background and Intent: Programs with ACGME-I Foundational Accreditation or from

institutions with ACGME-I accreditation do not qualify unless the program has also

achieved ACGME-I Advanced Specialty Accreditation. To ensure entrants into ACGME-

accredited programs from ACGME-I programs have attained the prerequisite

milestones for this training, they must be from programs that have ACGME-I Advanced

Specialty Accreditation.

III.B. Resident Complement

The program director must not appoint more residents than approved by

the Review Committee.

(Core)

III.B.1.a) There must be a sufficient number of residents to allow peer-to-

peer interaction and learning.

(Core)

III.B.1.a).(1) The program should offer a minimum of nine positions.

(Detail)

Specialty-Specific Background and Intent: The Review Committee believes that peer-to-peer

interactions and learning are extremely important components of residency education and

has set the minimum number of residents to nine. While three residents per educational year

is suggested, it is not required as long as there is relative balance per level. To ensure that

resident education is not compromised by having too few residents, the number of residents

in a program will be monitored at each review, particularly for those programs with significant

decreases in complement. However, this requirement is categorized as a “detail” as there

may be programs that have specific circumstances that allow them to function with a smaller

resident complement. This categorization allows the establishment of residency education

programs in rural and medically underserved areas and populations when the Review

Committee determines that the program has sufficient resources to ensure substantial

compliance with accreditation requirements.

Background and Intent: Programs are required to request approval of all complement

changes, whether temporary or permanent, by the Review Committee through ADS.

Permanent increases require prior approval from the Review Committee and temporary

increases may also require approval. Specialty-specific instructions for requesting a

complement increase are found in the “Documents and Resources” page of the

applicable specialty section of the ACGME website.

III.C. Resident Transfers

The program must obtain verification of previous educational experiences

and a summative competency-based performance evaluation prior to

acceptance of a transferring resident, and Milestones evaluations upon

matriculation.

(Core)

IV. Educational Program

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 27 of 64

The ACGME accreditation system is designed to encourage excellence and

innovation in graduate medical education regardless of the organizational

affiliation, size, or location of the program.

The educational program must support the development of knowledgeable, skillful

physicians who provide compassionate care.

It is recognized that programs may place different emphasis on research,

leadership, public health, etc. It is expected that the program aims will reflect the

nuanced program-specific goals for it and its graduates; for example, it is

expected that a program aiming to prepare physician-scientists will have a

different curriculum from one focusing on community health.

IV.A. Educational Components

The curriculum must contain the following educational components:

IV.A.1. a set of program aims consistent with the Sponsoring Institution’s

mission, the needs of the community it serves, and the desired

distinctive capabilities of its graduates, which must be made

available to program applicants, residents, and faculty members;

(Core)

IV.A.2. competency-based goals and objectives for each educational

experience designed to promote progress on a trajectory to

autonomous practice. These must be distributed, reviewed, and

available to residents and faculty members;

(Core)

Background and Intent: The trajectory to autonomous practice is documented by

Milestones evaluations. Milestones are considered formative and should be used to

identify learning needs. Milestones data may lead to focused or general curricular

revision in any given program or to individualized learning plans for any specific

resident.

IV.A.3. delineation of resident responsibilities for patient care, progressive

responsibility for patient management, and graded supervision;

(Core)

Background and Intent: These responsibilities may generally be described by PGY

level and specifically by Milestones progress as determined by the Clinical

Competency Committee. This approach encourages the transition to competency-

based education. An advanced learner may be granted more responsibility

independent of PGY level and a learner needing more time to accomplish a certain task

may do so in a focused rather than global manner.

IV.A.4. a broad range of structured didactic activities; and,

(Core)

IV.A.4.a) Residents must be provided with protected time to participate

in core didactic activities.

(Core)

Internal Medicine

©2023 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Page 28 of 64

Background and Intent: It is intended that residents will participate in structured

didactic activities. It is recognized that there may be circumstances in which this is not

possible. Programs should define core didactic activities for which time is protected

and the circumstances in which residents may be excused from these didactic

activities. Didactic activities may include, but are not limited to, lectures, conferences,

courses, labs, asynchronous learning, simulations, drills, case discussions, grand

rounds, didactic teaching, and education in critical appraisal of medical evidence.

IV.A.5. formal educational activities that promote patient safety-related

goals, tools, and techniques.

(Core)

IV.B. ACGME Competencies

Background and Intent: The Competencies provide a conceptual framework describing

the required domains for a trusted physician to enter autonomous practice. These

Competencies are core to the practice of all physicians, although the specifics are

further defined by each specialty. The developmental trajectories in each of the

Competencies are articulated through the Milestones for each specialty.

IV.B.1. The program must integrate the following ACGME Competencies

into the curriculum:

IV.B.1.a) Professionalism

Residents must demonstrate a commitment to

professionalism and an adherence to ethical principles.

(Core)

IV.B.1.a).(1) Residents must demonstrate competence in: