GAO

United States Government Accountabilit

y

Office

Report to Congressional Requesters

CONTRACTING

STRATEGIES

Data and Oversight

Problems Hamper

Opportunities to

Leverage Value of

Interagency and

Enterprisewide

Contracts

April 2010

GAO-10-367

What GAO Found

United States Government Accountability Office

Why GAO Did This Study

Highlights

Accountability Integrity Reliability

April 2010

CONTRACTING STRATEGIES

Data and Oversight Problems Hamper Opportunities

to Leverage Value of Interagency and Enterprisewide

Contracts

Highlights of GAO-10-367, a report to

congressional requesters

A

gencies can use several different

types of contracts to leverage the

government’s buying power for

goods and services. These include

interagency contracts—where one

agency uses another’s contract for

its own needs—such as the General

Services Administration (GSA) and

the Department of Veterans Affairs

multiple award schedule (MAS)

contracts, multiagency contracts

(MAC) for a wide range of goods

and services, and governmentwide

acquisition contracts (GWAC) for

information technology. Agencies

spent at least $60 billion in fiscal

year 2008 through these contracts

and similar single-agency

enterprisewide contracts. However,

concerns exist about duplication,

oversight, and a lack of information

on these contracts, and pricing and

management of the MAS program.

GAO was asked to assess the

reasons for establishing and the

policies to manage these contracts;

the effectiveness of GSA tools for

obtaining best MAS contract prices;

and GSA’s management of the MAS

program. To do this, GAO reviewed

statutes, regulations, policies,

contract documentation and data,

and interviewed officials from OMB

and six agencies.

What GAO Recommends

GAO makes recommendations: to

the Office of Management and

Budget (OMB) to strengthen policy,

improve data and better coordinate

agencies’ awards of MACs and

enterprisewide contracts; and to

GSA to improve MAS program

pricing and management. Both

agencies concurred with GAO’s

recommendations.

GWACs, MACs—two types of interagency contracts—and enterprisewide

contracts should provide an advantage to the government in buying billions

of dollars worth of goods and services. However, data are lacking and there is

limited governmentwide policy to effectively leverage, manage, and oversee

these contracts. The total number of MACs and enterprisewide contracts is

unknown, and existing data are not sufficiently reliable to identify them. In

addition, GWACs are the only interagency contracts requiring OMB approval.

Agencies GAO reviewed followed statutes, acquisition regulations, and

internal policies to establish and use MACs and enterprisewide contracts.

Avoiding fees associated with using other agencies’ contracts and more

control over procurements are some of the reasons agencies cited for

establishing MACs and enterprisewide contracts. However, many of the same

contractors provided similar products and services on multiple contracts—a

condition that increases costs to both the vendor and the government and

misses opportunities to leverage the government’s buying power. Recent

legislation and OMB’s Office of Federal Procurement Policy initiatives are

expected to strengthen management of MACs, but no such initiatives exist for

enterprisewide contracts.

GSA’s MAS program—the largest interagency contracting program—uses

several tools and controls to obtain best prices, but the limited application of

certain tools hinders its ability to determine whether it achieves this goal. GSA

has established two regulatory pricing controls for MAS contracts: seek the

best prices vendors provide to their most favored customers; and a price

reduction clause that provides the government a lower price if a vendor

lowers the price for similarly situated commercial customers. GSA uses other

pricing tools—e.g., pre-award contract audits by its Inspector General and

Procurement Management Reviews—on a limited basis. For example, the

Inspector General performs pre-award audits on a small sample of MAS

contracts annually, but has identified contract cost avoidance of almost $4

billion in recent years. In 2008, GSA established a MAS advisory panel that

recommended changes to the pricing controls noted above; concerns remain

that such changes could adversely affect GSA’s ability to negotiate best prices.

A lack of data, decentralized management, and limitations in assessment tools

create challenges for GSA in managing the MAS program. The agency lacks

data about customer agencies’ use of the program, limiting its ability to

determine how well the program meets customers’ needs. The MAS program

office lacks direct program oversight, as GSA has dispersed authority for

managing MAS among nine acquisition centers under three business

portfolios. Program stakeholders have identified concerns that this structure

has impaired consistent policy implementation. Shortcomings in assessment

tools also result in management challenges. For example, performance

measures are inconsistent, including inconsistent emphasis on pricing. GSA’s

customer satisfaction survey has such a low response rate that its utility for

evaluating program performance is limited.

View GAO-10-367 or key components.

For more information, contact John Needham

at (202) 512-4841 or needhamjk1@gao.gov.

Page i GAO-10-367

Contents

Letter 1

Results in Brief 5

Background 8

With Insufficient and Unreliable Data and Limited

Governmentwide Policy, Agencies’ Use of Interagency and

Enterprisewide Contracts May Result in Inefficient Contracting 18

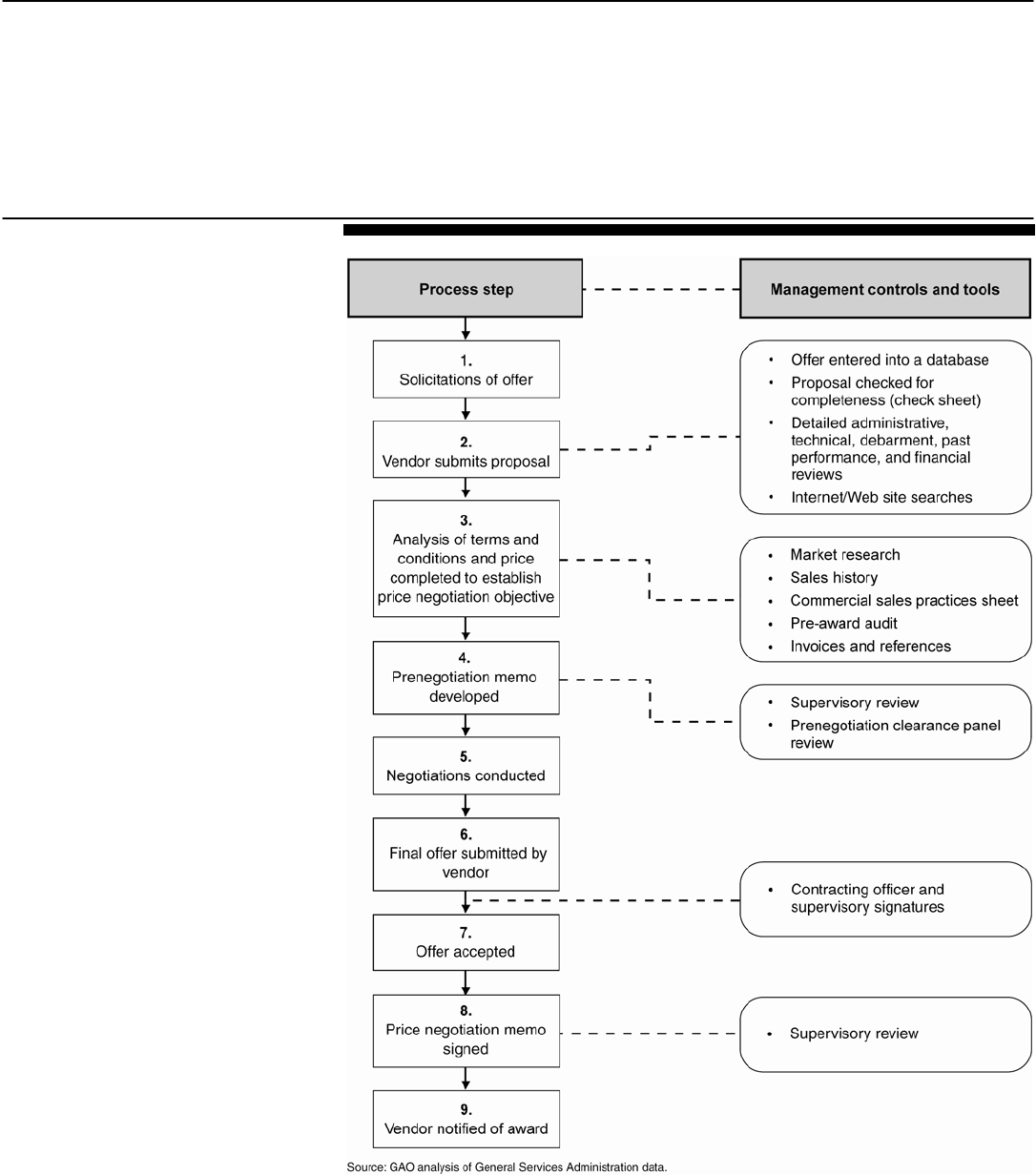

GSA’s Efforts to Determine Whether It Obtains the Best Prices on

MAS Contracts Is Hindered by the Limited Application of

Selected Pricing Tools 30

Effective MAS Program Management Is Hindered by a Lack of

Data, a Decentralized Management Structure, and Shortcomings

in Assessment Tools 39

Conclusions 46

Recommendations for Executive Action 47

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 49

Appendix I Scope and Methodology 52

Appendix II General Services Administration Multiple Award

Schedule Pricing Process and Tools 59

Appendix III Comments from the Department of Defense 60

Appendix IV Comments from the Department of Health and Human

Services 61

Appendix V Comments from the General Services Administration 63

Appendix VI GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 69

Contracting Strategies

Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Various Contract Vehicles Examined 10

Table 2: Governmentwide Acquisition Contracts as of September

30, 2008 12

Table 3: Selected Agencies’ and Military Departments’ Reasons for

Establishing MACs and Enterprisewide Contracts in Lieu

of Using the GSA MAS Program 23

Table 4: Selected Agencies’ and Military Departments’ Reasons for

Establishing MACs and Enterprisewide Contracts in Lieu

of Using GWACs and MACs Identified by Agencies 24

Table 5: Top 10 GWAC Vendors on GWACs, MACs, and

Enterprisewide Contracts 27

Table 6: Federal Agencies and Military Departments Included in

Our Review 52

Table 7: Vendors Included in Our Review 53

Table 8: List of Agencies, Military Departments, and Contracting

Programs Reviewed 55

Figures

Figure 1: MAS Program Sales, Fiscal Years 1996 through 2008 15

Figure 2: GSA MAS Pre-Award Audits, Fiscal Years 1998 through

2008 34

Figure 3: MAS Program Organizational Chart 43

Page ii GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

Abbreviations

DOD Department of Defense

DHS Department of Homeland Security

EAGLE Enterprise Acquisition Gateway for Leading-Edge Solutions

FAR Federal Acquisition Regulation

FAS Federal Acquisition Service

FPDS-NG Federal Procurement Data System-Next Generation

GAO Government Accountability Office

GSA General Services Administration

GWAC Governmentwide acquisition contract

MAC Multiagency contract

MAS Multiple Award Schedule

NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration

OFPP Office of Federal Procurement Policy

OMB Office of Management and Budget

PMR Procurement Management Review

VA Department of Veterans Affairs

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page iii GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

Page 1 GAO-10-367

United States Government Accountability Office

Washington, DC 20548

April 29, 2010

The Honorable Joseph I. Lieberman

Chairman

The Honorable Susan M. Collins

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Edolphus Towns

Chairman

The Honorable Darrell E. Issa

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Claire McCaskill

Chairman

Subcommittee on Contracting Oversight

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

Since 2002, spending on federal contracts has more than doubled, with

approximately $530 billion obligated

1

in fiscal year 2008. As this spending

has increased, there has been renewed focus on maximizing efficiencies in

the procurement process to achieve cost savings. One way to accomplish

this is by increasing the use of contracts designed to leverage the

government’s buying power when acquiring commercial goods and

services. These include the multiple award schedule (MAS) program

contracts (also known as the Federal Supply Schedule),

2

multiagency

1

In this report, we use procurement dollars reported by federal agencies which are

considered obligations and data from vendors which are reported in sales. Therefore, we

have used dollars obligated and sales data interchangeably.

2

MAS means contracts awarded by the General Services Administration or the Department

of Veterans Affairs for similar or comparable goods or services, established with more than

one supplier, at varying prices. Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) § 8.401.

Contracting Strategies

contracts (MAC), and governmentwide acquisition contracts (GWAC).

3

The General Services Administration (GSA) directs and manages the MAS

program. It has delegated authority to the Department of Veterans Affairs

(VA) to operate schedules for medical supplies.

4

Other agencies have

established and operate MACs and GWACs. MAS contracts, MACs, and

GWACs are all interagency contracts.

When managed properly, interagency contracting—a process by which

one agency either uses another agency’s contract directly or obtains

contracting support services from another agency—can leverage the

government’s aggregate buying power and provide a simplified and

expedited method for procuring commonly used goods and services.

Enterprisewide contracts, which, according to procurement officials,

appear to have become more popular in recent years, are internal

purchasing programs established within a federal department or agency to

acquire goods and services. They are similar to interagency contracts in

that they can leverage the purchasing power of the federal agency but

generally do not allow purchases from the contract by federal activities

other than the original acquiring activity. In fact, the Office of

Management of Budget (OMB) recently reported that 20 of the 24 largest

procuring activities are planning to achieve contracting savings by

implementing strategic sourcing initiatives

5

by using enterprisewide

contracting to leverage their buying power.

6

These initiatives are part of

OMB’s goal, announced in December 2009, of reducing contract cost by 7

percent by September 30, 2011.

3

MACs are task-order or delivery-order contracts established by an agency that can be used

for governmentwide use to obtain goods and services, consistent with the Economy Act.

FAR § 2.101. GWACs are considered multiagency contracts but, unlike other multiagency

contracts, are not subject to the same requirements and limitations, such as documenting

that the contract is in the best interest of the government, set forth under the Economy Act.

The Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996 authorized GWACs to be used to buy information

technology goods and services. 40 U.S.C. § 11314(a)(2). These contracts are operated by

an executive agent designated by the Office of Management and Budget. FAR § 2.101.

4

VA operates its portion of the schedules program under a delegation of authority from

GSA. Although GSA has delegated to VA the authority to contract for medical supplies

services under various MAS, GSA has not delegated to VA the authority to prescribe the

policies and procedures that govern the MAS program.

5

An approach to leverage buying power, reduce costs, better manage suppliers, and

improve the quality of goods and services acquired.

6

Office of Management and Budget, Acquisition and Contracting Improvement Plans and

Pilots: Saving Money and Improving Government (Washington D.C.: Dec. 2009).

Page 2 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

Though precise numbers are unavailable, in fiscal year 2008, government

buyers used the MAS program, MACs, and GWACs to acquire at least $60

billion of commercial goods and services, including billions spent through

enterprisewide contracts. Some in the procurement community have

raised concerns about a proliferation of some of these contracts, noting

that without coordinated governmentwide oversight of MACs and

enterprisewide contracts it is unclear whether the use of these contracts

helps government buyers leverage their buying power. The perceived

growth in the number of these contracts and duplication that has occurred

with their growth may also adversely affect the overall administrative

efficiencies and cost savings expected with their use. Furthermore, in

recent years, we and others have highlighted challenges with MAS

program pricing and compliance with the Federal Acquisition Regulation

(FAR) to obtain the best possible value. In this context, you requested

that we address management issues associated with the growth in use of

interagency contracting vehicles and enterprisewide contracts, and

especially the management of the GSA’s MAS program contracts.

Specifically, this report addresses:

1. the data that exist to describe MACs, GWACs, and enterprisewide

contracts use governmentwide; the extent to which policies and

guidance exist to establish and manage these contracts; and the

reasons agencies use these contracts;

2. the effectiveness of tools and controls GSA uses to obtain the best

possible prices for customers of its MAS program; and

3. the extent to which GSA has performance information and an

oversight structure in place to manage the MAS program.

We conducted this work at the Office of Federal Procurement Policy

(OFPP) within OMB, which has governmentwide procurement policy

responsibility. We also conducted work at six federal agencies including

GSA, the Department of Defense (DOD), including the three military

departments, Department of Health and Human Services, Department of

Homeland Security (DHS), VA, and the National Aeronautics and Space

Administration (NASA) because these agencies established and or used

the MAS, GWAC, MAC, or enterprisewide contract programs and were

responsible for almost 87 percent of total federal procurement obligations

in fiscal year 2008.

7

To assess the oversight of and benefits provided these

7

Franchise funds and interagency assisting entities that undertake some or all of the

contracting function for an agency, typically on a “fee-for-service” basis, are not part of this

review. See GAO, Interagency Contracting: Franchise Funds Provide Convenience, but

Value to DOD Is Not Demonstrated, GAO-05-456 (Washington, D.C.: July 29, 2005).

Page 3 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

programs, we reviewed policies, agency directives, relevant studies, audit

reports, the FAR, and other regulations relevant to our review objectives.

We interviewed OFPP representatives responsible for overseeing

interagency contracting, the Senior Procurement Executives or their

representatives for the agencies where we conducted work, and other

agency officials responsible for multiagency and enterprisewide contracts.

To determine the magnitude of multiagency and enterprisewide contracts,

we attempted to use the Federal Procurement Data System-Next

Generation (FPDS-NG) but found that the data were not sufficiently

reliable to determine the universe and use of MACs

8

or enterprisewide

contracts. Despite its critical role, we have consistently reported on

FPDS-NG data quality issues over a number of years.

9

This lack of

reliability made it impossible to determine the universe and use of these

types of contracts. Hence, we conducted literature searches and reviewed

agencies’ and government contractors’ Web pages to identify examples of

MACs and enterprisewide contracts. After identifying examples of these

contracts, we judgmentally selected for review 14 contracting programs

from 5 of the 6 agencies and 2 of the 3 military departments that had at

8

To determine if the data on interagency contracts were reliable we tried to verify some of

the data generated from FPDS-NG. For instance, FPDS-NG includes a data field that is

intended to identify GWACs but we found a number of instances where known GWACs

were coded incorrectly. We also searched the system by contract number for MACs that

we were aware of and found similar issues, with some contracts coded properly as MACs

and some not. In addition, to identify a contract as a MAC, we searched for indefinite

delivery contracts that were coded as being governed by the Economy Act—which most

MACs are—and determined if the contract was also used by any agency other than the one

that entered into the contract.

9

We have previously reported on data reliability issues with FPDS-NG. See, e.g., GAO,

Federal Contracting: Observations on the Government’s Contracting Data Systems,

GAO-09-1032T (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 29, 2009); Contract Management: Minimal

Compliance with New Safeguards for Time-and-Materials Contracts for Commercial

Services and Safeguards Have Not Been Applied to GSA Schedules Program, GAO-09-579

(Washington, D.C.: June 24, 2009); Interagency Contracting: Need for Improved

Information and Policy Implementation at the Department of State, GAO-08-578

(Washington, D.C.: May 8, 2008); Department of Homeland Security: Better Planning and

Assessment Needed to Improve Outcomes for Complex Service Acquisitions, GAO-08-263

(Washington, D.C.: April 22, 2008); Federal Acquisition: Oversight Plan Needed to Help

Implement Acquisition Advisory Panel Recommendations, GAO-08-160 (Washington,

D.C.: Dec. 20, 2007), Improvements Needed to the Federal Procurement Data System-Next

Generation, GAO-05-960R (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 27, 2005); Reliability of Federal

Procurement Data, GAO-04-295R (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 30, 2003); OMB and GSA: FPDS

Improvements, GAO/AIMD-94-178R (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 19, 1994); The Federal

Procurement Data System—Making It Work Better, GAO/PSAD-80-33 (Washington, D.C.:

Apr. 18, 1980); and The Federal Procurement Data System Could Be an Effective Tool for

Congressional Surveillance, GAO/PSAD-79-109 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 1, 1979).

Page 4 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

least one of the three contract types (MAC, GWAC, and enterprisewide

contracts), and met with agency officials and vendors to confirm our

identification of examples and to obtain their perspectives on the

proliferation of these vehicles. Because the MAS program represents the

single largest federal program providing multiagency contracts, we

concentrated our work on the MAS program. Furthermore, because GSA

rather than VA sets the policy for the MAS program, we focused on GSA’s

management of the program. We reviewed GSA’s management structure

for overseeing the program and the tools and controls GSA established for

obtaining fair and reasonable pricing for MAS contracts. We reviewed

GSA memorandums, regulations, manuals, and other relevant

documentation; interviewed agency officials; and analyzed GSA processes

and practices related to program oversight and contract negotiations. We

also conducted structured interviews with 16 vendors with high sales on

the GSA MAS program and had also been awarded GWACs, MACs, or

enterprisewide contracts. The 16 vendors represented both large and small

businesses. We also judgmentally selected 17 contracting officers from 4

of the 6 agencies selected for review and the 3 military departments who

had placed orders through one of the reviewed contract vehicles to obtain

their perspectives on the management and pricing of the MAS contracts,

MACs, GWACs and enterprisewide contracts. We also met with

representatives of several private sector organizations—the Coalition for

Government Procurement, Jefferson Solutions, LLC, the Professional

Services Council, and the Washington Management Group—that represent

vendors and contractors to obtain their views on issues related to our

review objectives.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2008 through April

2010 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing

standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to

obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for

our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives. A more detailed discussion of

our scope and methodology is in appendix I.

Interagency and enterprisewide contracts should provide an advantage to

the government in buying billions of dollars worth of goods and

services, yet OMB and agencies lack reliable, comprehensive data

to effectively leverage, manage, and oversee these contracts. The total

number of MACs and enterprisewide contracts currently in use by

agencies is unknown because the federal government’s official

Results in Brief

Page 5 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

procurement database, FPDS-NG, is not sufficiently reliable for identifying

these contracts. This has been a longstanding problem. Furthermore, we

found there is limited governmentwide policy for establishing and

overseeing MACs and enterprisewide contracts. The agencies we

reviewed followed statutes, FAR, and their own internal policies and

guidance to justify, establish, and operate MACs and enterprisewide

contracts. Currently, GWACs are the only contracts requiring approval

from and annual reporting to OMB. We also found that some agencies’

policies or guidance have encouraged the use of enterprisewide contracts

over the use of other contracts, including the GSA MAS program contracts.

We found that departments and agencies establish, justify, and use their

own MACs and enterprisewide contracts rather than other established

interagency contracts for a variety of reasons, which include avoiding fees

paid for the use of other agencies’ contracts, gaining more control over

procurements made by organizational components, and allowing for the

use of cost reimbursement contracts. Under these conditions, many of the

same vendors provided similar products and services on multiple

contracts, which increases costs to both the vendor and the government

and can result in missed opportunities to leverage the government’s

buying power. Recent legislation and OFPP initiatives are expected to

strengthen oversight and management of MACs, but no initiatives are

underway to strengthen oversight of enterprisewide contracts.

GSA’s MAS program—the largest interagency contracting program with

approximately 17,000 contracts—uses several tools and controls in the

contract award and administration process to obtain and maintain best

prices for its contracts, but applies some of the tools on a limited basis.

This hinders GSA’s ability to determine whether it achieves the MAS

program goal of obtaining best prices. GSA has established two key

regulatory controls to obtain and maintain best prices throughout the life

of all MAS contracts. The first is the provision that, prior to award, GSA

seeks to obtain the best price that a vendor provides to their most favored

customer,

10

and the second is the use of a price reduction clause in each

MAS contract that allows the government to receive a lower contract price

after award if the vendor lowers its price to similarly situated commercial

customers. However, GSA does not collect information to determine if the

price reduction clause is working as intended. GSA also uses other tools

10

Most favored customers are customers or categories of customers that receive the best

price from vendors (48 C.F.R. 538.270(a), 538.271, and 538.272). The pursuit of most

favored customer pricing is consistent with the objective of negotiating a fair and

reasonable price (Final rule, 62 Fed. Reg 44,518, 44,519 (Aug. 21, 1997)).

Page 6 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

to leverage the government’s buying power, evaluate compliance with

program pricing policies, and ensure the quality of contract negotiations

primarily for larger contracts. These include pre-award audits of MAS

contracts by the GSA Inspector General, clearance panel reviews of

contract negotiation objectives, and Procurement Management Reviews.

However, GSA applies these tools to a small number of MAS contracts.

For example, the GSA Inspector General performed pre-award audits of 69

contracts in fiscal year 2008, but does not target hundreds of other

contracts that are eligible for audit. Nevertheless, with an investment of a

few million dollars annually, the Inspector General recommended almost

$4 billion in cost avoidance through these audits from fiscal years 2004

through 2008—cost avoidance would result from lower prices paid by

government buyers. We also found several instances where required

clearance panel reviews were not held, and GSA officials said that they do

not check whether contracts that met the appropriate threshold received a

panel review as required, thus limiting the effectiveness of this tool. GSA

also conducts Procurement Management Reviews to assess contracts’

compliance with statutory requirements and internal policy and guidance.

However, GSA only selects a small number of contracts for review and at

the time of our fieldwork did not use a risk-based selection methodology,

which does not permit GSA to derive any trends based on the review

findings. In 2008, GSA established an advisory panel to review MAS

program pricing provisions, which has recommended changes to the

pricing provisions, among other things. These changes include elimination

of the price reduction clause and clarifying the price objective for MAS

contracts, which could potentially remove “most favored customer” as the

pricing goal for MAS contracts. However, concerns remain that

eliminating these provisions could adversely affect GSA’s ability to

negotiate best prices.

A lack of comprehensive data, a decentralized management structure, and

limitations in assessment tools create challenges for GSA to manage the

MAS program effectively and have a program wide perspective on its

operations. Our prior work has highlighted the importance of having

comprehensive data as part of a strategic approach to procurement, noting

that the use of procurement data to identify buyers and how much is being

spent for goods and services can identify opportunities to save money and

improve performance. However, GSA lacks data about the use of the MAS

program by customer agencies. Without this data, GSA is limited in its

ability to determine how well the MAS program meets its customers’ needs

and to help its customers obtain the best value through MAS contracts,

among other things. In addition, the decentralized management structure

for the MAS program hinders consistent implementation of the MAS

Page 7 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

program within GSA, as well as program oversight. GSA established a

MAS program office in 2008 to manage strategic and policy issues for the

program. However, it lacks direct oversight authority for the MAS

program—program oversight is not addressed in its charter. Rather, GSA

has dispersed responsibility for the management of individual contract

schedules among nine acquisition centers under three business lines.

Some MAS program officials and vendors we met with pointed out that as

a result of this structure, a lack of communication and consistency exists

among the acquisition centers, which has impaired the consistent

implementation of policies across the MAS program and the sharing of

best practices, and the GSA Inspector General has identified issues with

oversight of the MAS program. Finally, shortcomings in assessment tools

also result in management challenges. For example, performance

measures are inconsistent across the GSA organizations that manage MAS

contracts, including inconsistent emphasis on pricing. GSA’s MAS

customer satisfaction survey also has an extremely low response rate that

limits its utility as a means for evaluating program performance.

We make five recommendations to OMB to strengthen policy, improve

data and better coordinate agencies’ awards of MACs and enterprisewide

contracts. We also make eight recommendations to GSA to improve MAS

program pricing and management. Both OMB and GSA agreed with our

recommendations. DOD pointed out in its comments on the draft of this

report that it is the largest purchasing organization in the federal

government and the largest customer of GSA and looks forward to

working with the OMB’s Administrator for OFPP and with GSA on their

efforts to implement the recommendations. The Department of Health

and Human Services concurred with our findings and recommendations.

Likewise, NASA stated that our draft report was complete, concise, and

accurate and provided a balanced view of issues. DHS and VA elected not

to provide comments on a draft of the report.

Government buyers generally use three types of available interagency

contracts—MACs, GWACs, and MAS program contracts—all of which

leverage the government’s buying power when acquiring goods and

services. These interagency contracts can be established under several

statutory authorities, including: (1) the Economy Act,

11

which authorizes

agencies to place orders for goods and services with another government

Background

11

31 U.S.C. § 1535.

Page 8 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

agency; (2) the Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996,

12

which authorizes GWACs; and

(3) the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act of 1949, as

amended,

13

which provides authority for GSA’s MAS program.

The Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act of 1994,

14

also has a bearing on

interagency contracting, since its enactment, along with that of the

Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996, authorized fundamental changes in the

management of government acquisition programs. These statutes (1)

made it easier for federal agencies to purchase commercial items; (2)

streamlined the processes for making small purchases; (3) eliminated GSA

as the sole authority for all federal information technology acquisitions;

and (4) allowed for establishment of GWACs and other contracting

vehicles including enterprisewide contracts. Since then, some agencies

have established and operated MACs, GWACs, and enterprisewide

contracts, while GSA operates the MAS program. Agencies, including GSA

and VA for the MAS program, usually charge their customer agencies fees

for using their GWACs, MACs, and schedule contracts. These fees are

usually a percentage of the value of the procurement to cover the costs of

administering the contract. Table 1 describes the various contract types

we examined, including the number in existence and fees charged when

known, and their fiscal year 2008 sales.

12

40 U.S.C § 11314(a)(2).

13

41 U.S.C. § 251 et seq. and 40 U.S.C. § 501.

14

Pub. L. No. 103-355.

Page 9 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of Various Contract Vehicles Examined

Interagency contracts

Multiple award schedules

GSA VA

MACs GWACs

Enterprisewide

contracts

Authority Federal Property and

Administrative Services Act of 1949

as amended. GSA delegated

authority to VA

Economy Act Clinger-Cohen Act Various authorities to

include the Economy

Act and the Federal

Acquisition

Streamlining Act

Purpose To provide comparable commercial

goods and services at varying

prices and a streamlined process to

obtain these goods and services at

prices associated with volume

buying.

To obtain goods or

services by

interagency

acquisition which

cannot be obtained

as conveniently

or economically by

contracting directly

with a private

source

To provide a broad

range of information

technology goods and

services.

Provide authority for

placement of orders

between major

organizational units

within an agency and

establishing a general

preference for use of

multiple awards.

Number of

schedules/programs

49 schedules 9 schedules Unknown 16 programs Unknown

Sales in 2008

(in billions)

$37.6 $9.2 Unknown

a

$5.3 Unknown

b

Number of contracts Approximately

19,000

Unknown 1,031 Unknown

Fee Structure 0.75 % 0.50% Unknown 0.25 -1.75 % Not applicable

Source: GAO analysis of statutes, regulations and agency data. Dollars and numbers are from fiscal year 2008 data.

a

The four MAC programs reviewed had obligations totaling $2.5 billion in fiscal year 2008.

b

The three enterprisewide contract programs reviewed had obligations totaling $4.8 billion in fiscal

year 2008.

In fiscal year 2008, as shown in table 1, federal agencies used GWACs,

MACs, and the MAS program to buy at least $60 billion of goods and

services to support their operations including some agencies spending

billions using enterprisewide contracts. GWACs, MACs, the

enterprisewide contracts we examined, and contracts under the MAS

program are all indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (ID/IQ) contracts--

contracts that are established to buy goods and services when the exact

times and exact quantities of future deliveries are not known at the time of

Page 10 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

award.

15

Once known, an agency places individual delivery orders for

goods and task orders for services against these contracts.

MACs and GWACs

MACs and GWACs provide advantages to both agencies and vendors. For

agencies, they provide a means of procuring goods and services without

the time and expense of a full and open solicitation for each order. For

vendors, the FAR requires agencies to provide a fair opportunity to be

considered for orders exceeding $3,000.

16

The Economy Act, along with

other authorities, allows an agency to enter into a MAC and then make it

available for other government agencies to place task or delivery orders to

obtain a variety of goods and services.

17

The Economy Act is applicable to

orders placed under MACs, with the exception of MACs for information

technology that are established pursuant to the Clinger-Cohen Act. Per

the FAR guidance for the Economy Act, an agency planning to place an

order against another agency’s MAC must document that the servicing

agency has an appropriate pre-existing contract available for use or that it

has the capabilities or expertise to enter into a contract for the required

goods or services, which is not available within the requesting agency.

18

MACs are established within their respective agencies and no external

reporting on their use is required. As a result, governmentwide

comprehensive data on the number of MACs and dollars involved with

their use are not readily available.

15

Based on FPDS-NG data, in fiscal year 2008, $161 billion (over 30 percent of total federal

procurement) was obligated using ID/IQ contracts.

16

Fair opportunity requires a contracting officer to provide each awardee a fair opportunity

to be considered for each order exceeding $3,000 issued under multiple ID/IQ contracts

unless (1) the agency need for the goods or services is so urgent that providing a fair

opportunity would result in unacceptable delays, (2) only one awardee is capable of

providing the goods or services required at the level of quality required because they are

unique or highly specialized, (3) the order must be issued on a sole-source basis in the

interest of economy and efficiency because it is a logical follow-on to an order already

issued under the contract provided that all awardees were given fair consideration for the

original order, or (4) it is necessary to place an order to satisfy a minimum guarantee. FAR

§16.505(b).

17

The Economy Act, authorizes an agency to place orders for goods and services with

another government agency when the head of the requesting (i.e., ordering) agency

determines that it is in the best interest of the government and decides it cannot order

goods or services by contract with a commercial enterprise as conveniently or cheaply. 31

U.S.C. § 1535.

18

FAR §§ 17.503, 17.504.

Page 11 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

GWACs provide a broad range of information technology goods and

services and resources for agency activities.

19

Each GWAC is operated by

an executive agent designated by OMB.

20

The Economy Act does not

apply when placing orders under GWACs. As of March 30, 2010, four

agencies—GSA, NASA, the Department of Health and Human Service

and the Environmental Protection Agency—had OMB authorization to

operate GWACs. As shown in table 2 below, these agencies were

responsible from 1 to 11 GWAC programs having obligations in fiscal y

2008 totaling almost

s,

ear

$5.3 billion.

Table 2: Governmentwide Acquisition Contracts as of September 30, 2008

Executive agency

Number of GWAC

Programs

Total fiscal year 2008 sales

(billions)

General Services Administration 11 $2.93

National Aeronautics and Space

Administration 1 $1.32

Department of Health and Human

Services, National Institutes of

Health

3 $1.04

Environmental Protection Agency 1 $0.00

a

Source: GAO analysis of agency information.

a

Sales against the Environmental Protection Agency GWAC in fiscal year 2008 totaled less than

$63,000.

Obligations placed against GWACs have ranged from about $5 to $6 billion

annually, but have declined slightly in recent years from $5.8 billion in

fiscal year 2004 to $5.3 billion in fiscal year 2008.

Enterprisewide Contracts

Along with using interagency contracts to leverage their buying power, a

number of large departments—DOD and DHS in particular—are turning to

enterprisewide contracts as well to acquire goods and services.

Enterprisewide contracting programs are IDIQ contracts established

solely for the use of the establishing agency and can be used to reduce

contracting administrative overhead, provide information on agency

spending, meet various requirements across the agency, and avoid the fees

19

GWACs are considered MACs, but unlike other MACs, they are not subject to the

Economy Act. FAR § 2.101.

20

OFPP, within OMB, is responsible for the overall management of the GWAC program.

Page 12 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

charged for using interagency contracts, such as a GWAC. Creating

enterprisewide contracts can also be a method to support strategic

sourcing within the agency and a means of tailoring requirements for

agency-unique purposes. They can also be used to specify and enforce

specific contract terms and conditions and bring more consistency into

the agency contracting processes. Three significant enterprisewide

contracting programs are DHS’s Enterprise Acquisition Gateway for

Leading-Edge Solutions (EAGLE) and FirstSource programs and the

Department of the Navy’s SeaPort Enhanced program. EAGLE and

FirstSource provide contracts with 64 vendors for information technology

services and commodities, respectively, for the 16 components that make

up DHS and obligated over $1.2 billion in fiscal year 2008. The Department

of the Navy’s SeaPort Enhanced program provides contracts for procuring

engineering, technical, programmatic, and professional support services.

Currently the program has contracts with over 1,800 vendors and obligated

almost $3.6 billion in fiscal year 2008.

MAS Program

GSA has had a prominent role in providing goods and services to federal

agencies for decades as part of its responsibility for administering supplies

for federal agencies. Through its MAS program (also referred to in this

report as the schedules program), GSA provides federal agencies with a

simplified method for procuring various quantities of a wide range of

commercially available goods and services. As the largest interagency

contracting program, the MAS program provides advantages to both

federal agencies and vendors.

21

Agencies, using the simplified methods of

procurement of the schedules, avoid the time expenditures and

administrative costs of other methods. Vendors receive wider exposure

for their commercial products and expend less effort to selling these

products. Moreover, the MAS program is the primary governmentwide

buying program aimed at helping the federal government leverage its

significant buying power when buying commercial goods and services.

Together, GSA and VA operate 58 schedules. GSA operates 49 schedules,

which offer a wide range of goods and services such as office furniture

and supplies, personal computers, scientific equipment, library services,

network support, laboratory testing services, and management and

advisory services. GSA delegated to the VA the authority to solicit,

21

While GSA, in its regulations uses the term “offeror,” for purposes of this report we use

the term “vendor.”

Page 13 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

negotiate, award, and administer contracts for selected schedules. VA has

seven schedules for various categories of medical/surgical supplies and

equipment and pharmaceuticals, and two schedules for various health care

services including professional health care and staffing services and

laboratory testing and analysis services.

In August 1997, after passage of FASA and the Clinger-Cohen Act, GSA

revised its acquisition regulations to promote greater use of commercial

buying practices, and streamline the purchasing process for its

customers.

22

GSA expected these changes to lead to more participation by

both large and small businesses, and to increased competition, thereby

providing federal agencies a wider range of goods and services at

competitive prices. As of December 2009, there were almost 19,000

available contracts providing goods and services on the GSA and VA

schedules. While MAS sales by both GSA and VA have grown significantly

since 1998, sales have leveled off in recent years, as shown in figure 1.

22

62 Fed. Reg. 44,518 (Aug. 21, 1997).

Page 14 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

Figure 1: MAS Program Sales, Fiscal Years 1996 through 2008

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

2008200620042002200019981996

Dollars (in billions)

Fiscal year

VA multiple award schedule program

GSA multiple award schedule program

Source: GAO analysis of GSA and VA data.

Note: Sales are presented in fiscal year 2009 dollars.

Over the last several years, GSA initiated several changes within the MAS

program. In late 2006, the agency reorganized and created the Federal

Acquisition Service (FAS), which combined the duties of the Federal

Technology Service and the Federal Supply Service. As part of this

reorganization, GSA established three primary FAS business portfolios—

General Supplies and Services; Integrated Technology Services; and

Travel, Motor Vehicle, and Card Services—and gave them management

and operational control over the MAS schedules. Within these portfolios,

nine acquisition centers located throughout the United States award and

manage MAS contracts. GSA also established within FAS the Office of

Acquisition Management, which is responsible for ensuring that GSA

activities comply with federal laws, regulations, and policies, and that

operating practices are consistent across business lines and acquisition

centers. In July 2008, within the Office of Acquisition Management, GSA

created the MAS Program Office to develop and implement acquisition

policy and guidance, define systems requirements, and coordinate

program-wide improvements. VA manages its portion of the MAS program

from its National Acquisition Center, located in Hines, Illinois. The MAS

Page 15 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

Governance Council, established in 2008 as part of the creation of the MAS

Program Office, includes representatives from both GSA and VA, and is

responsible for addressing and coordinating MAS program issues that

affect both GSA and VA.

In 2008, GSA also established a MAS Advisory Panel to provide

independent advice and recommendations on MAS program pricing

policies and provisions in the context of commercial pricing practices.

The panel is made up of representatives from GSA and other federal

agencies as well as industry associations. The panel issued its report in

February 2010, and made numerous recommendations to GSA regarding

the MAS program pricing provisions, competition requirements, and data

collection, among other things.

23

Prior Reviews of

Interagency Contracts and

the MAS Program Raised

Concerns

Prior reviews and audits of interagency contracting and the MAS program

by GAO and inspectors general have highlighted several management

challenges and concerns. Between 1999 and 2009, we and agencies’

inspectors general issued 12 audit reports identifying a lack of competition

for task and delivery orders issued under ID/IQ contracts. These reports

addressed task and delivery orders awarded under the MAS program,

GWACs, MACs, and enterprisewide contracts and found that the orders

were either not competed, did not provide for fair opportunity, and/or

restricted competition. For example, in 2004, we found that contracting

officers waived competition requirements for nearly half—34 out of 74—of

MAS orders reviewed.

24

In early 2005, we reported that the use of interagency contracting vehicles

had grown rapidly and numerous issues had surfaced, including problems

with internal controls, inadequate competition, unclear definitions of roles

and responsibilities, and inadequate training of contracting personnel. As

a result, we designated the management of interagency contracting as high

risk in 2005.

25

We stated in our 2005 high risk report that the government

needed to bolster oversight and control over interagency contracting so

that it would be well-positioned to realize the benefits of these contracts.

23

Multiple Award Schedule Advisory Panel Final Report (Feb. 2010).

24

GAO, Contract Management: Guidance Needed to Promote Competition for Defense

Task Orders, GAO-04-874 (Washington D.C.: July 30, 2004).

25

GAO, High-Risk Series: An Update, GAO-05-207 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 2005).

Page 16 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

Even though interagency contracting remains on our list of high-risk areas,

there has been an improvement. In 2009, we reported that OMB and

federal agencies have made progress toward improving the use of

interagency contracting. For example, we reported that OMB issued

policy guidance designed to improve the use of interagency contracting

across the government.

26

In 2005, we also reported on GSA’s schedules program pointing out several

problems related to schedule contract pricing based on GSA’s review of

selected MAS contract files from fiscal year 2004.

27

Nearly 60 percent of

the contract files GSA reviewed lacked the documentation needed to

establish clearly that GSA had effectively negotiated schedule prices. GSA

was also not effectively using pricing tools such as pre-award audits, to

meet its pricing objectives. In response to a recommendation in our

report, GSA significantly increased the number of annual pre-award audits

resulting in a total of almost $4 billion in cost avoidances over a five year

period.

In 2007, the Acquisition Advisory Panel—often referred to as the SARA

panel—reported in fiscal year 2004, FPDS-NG data showed that total

obligations for interagency contracting reached $142 billion, or 40 percent

of the total obligated governmentwide on contracts that year.

28

The panel

concluded that pressures and incentives for agencies to establish and use

interagency contracting vehicles, coupled with little oversight or

transparency, had created an environment that allowed the uncoordinated

proliferation of interagency contracts, which in turn hampered the

government’s ability to maximize the effectiveness of these contracts

While the panel report provided an estimate of the total obligations for

interagency contracts in fiscal year 2004, it also stated that the FPDS-NG

26

GAO, High-Risk Series: An Update, GAO-09-271 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 2009).

27

GAO, Contract Management: Opportunities to Improve Pricing of GSA Multiple Award

Schedules Contracts, GAO-5-229 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 11, 2005).

28

The panel was established by Section 1423 of the Services Acquisition Reform Act of 2003,

which was enacted as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2004

(Pub. L. No. 108-136, (2003). The statute tasked the panel, among other things, to review

governmentwide policies regarding the use of governmentwide contracts. We did not

assess the reliability of the data reported by the panel.

Page 17 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

data used to make this estimate and analyze interagency contracts were

not reliable at the detailed level.

29

In 2009, the DOD’s Inspector General found problems with enterprisewide

contracting reporting that the Department of the Navy’s SeaPort Enhanced

internal controls were not adequate.

30

Furthermore, the Inspector General

found that the SeaPort Enhanced program office did not ensure that task

orders were open for bidding for the length of time specified and deviated

from FAR criteria by not performing adequate market research. In another

report issued in 2009, the DOD Inspector General reported that 72

percent—21 out of 29—of the task orders awarded under a GWAC valued

at $13.9 million had insufficient competition.

31

Interagency and enterprisewide contracts should provide an advantage to

the government in buying billions of dollars worth of goods and

services, yet OMB and agencies cannot be sure they are leveraging

this buying power because they lack the necessary comprehensive,

reliable data to effectively manage and oversee these contracts.

Additionally, the government's lack of an overarching governmentwide

policy to ensure that leveraging happens further exacerbates the problem

.

Absent governmentwide data and policy, agencies have created numerous

MACs and enterprisewide contracts using existing statutes, the FAR, and

agency-specific policies. The creation of these contracts is based on a

number of rationales and reasons including avoiding fees that would be

paid for using interagency contracts, allowing for cost-reimbursement

contracts, and getting more control over the procurement actions of their

sub-components. Under these conditions, however, duplication of similar

contracts and inefficiencies have occurred. Both government contracting

officials and representatives of vendors expressed concerns about this

condition. While some steps are being taken to improve this condition,

more can be done to improve the government's buying power.

With Insufficient and

Unreliable Data and

Limited

Governmentwide

Policy, Agencies’ Use

of Interagency and

Enterprisewide

Contracts May Result

in Inefficient

Contracting

29

Report of the Acquisition Advisory Panel to the Office of Federal Procurement Policy

and the United States Congress (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 2007). Chap. 3 and Chap. 7.

30

Inspector General, Department of Defense, SeaPort Enhanced Program, D-2009-082

(Arlington, Va.: May 6, 2009).

31

Inspector General, Department of Defense, FY 2007 DOD Purchases Made Through the

National Institutes of Health, D-2009-064 (Arlington, Va.: March 24, 2009).

Page 18 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

Prior attempts by the acquisition community to identify interagency and

enterprisewide contracts have not resulted in a reliable database useful for

identifying or providing governmentwide oversight on those contracts. In

2003, a FAR rule established an interagency contracting directory to

collect information on interagency contracting vehicles.

32

In 2006, OFPP

started the Interagency Contracting Data Collection Initiative to identify

and list the available GWACs, MACs, and enterprisewide contracts. OFPP

requested that all federal agencies with interagency contracts report the

number of contracts available with a description of what was available on

each contract, which agencies could use it, the reason for creating it, and

whether or not there was a completed business case analysis on the

contract. Twenty-two of the 24 major federal agencies responded to OMB.

The initiative was a one-time effort and thus has not been updated since.

The Identification and Use

of MACs and

Enterprisewide Contracts

Is Unknown

In conducting this review, we could not identify the universe of MACs and

enterprisewide contracts because the data available in the official

government contracting data system, FPDS-NG, were insufficient and

unreliable. Despite its critical role, we have consistently reported on

FPDS-NG data quality issues over a number of years and found problems.

33

In 2009, we testified that OMB has taken steps to address some of these

problems; however, the quality of some FPDS-NG data remains an issue.

34

The fiscal year 2009 National Defense Authorization Act requires that the

Director of OMB direct improvements to the FPDS-NG to collect more

complete and reliable data on interagency contracting actions.

35

These

requirements, however, do not call for capturing data on enterprisewide

32

68 Fed. Reg. 43,859 (July 24, 2003). This rule added new FAR subpart 5.6, Publicizing

Multiagency Use Contracts, which (1) provides the Internet address to access the database

(i.e., www.contractdirectory.gov); (2) requires contracting activities to enter information

into the database within 10 days of award of a procurement instrument intended for use by

multiple agencies; and (3) required contracting activities to enter information into the

database by October 31, 2003, on all contracts and other procurement instruments intended

for multiple agency use existing at the time of the FAR amendment.

33

We made a number of narrowly focused recommendations on FPDS-NG data quality in

2005. While these recommendations have been addressed, our subsequent work shows

that FPDS-NG data reliability remains an issue.

34

GAO, Federal Contracting: Observations on the Government’s Contracting Data

Systems, GAO-09-1032T (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 29, 2009).

35

The data to be collected is to contain information on interagency contracting actions at

the task or delivery order level and other transactions, including the initial contract and any

subsequent modifications awarded or orders issued. Pub. L. No. 110-417 § 874 (2008).

Page 19 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

contracts, which are now being used to achieve savings as part of the

governmentwide strategic sourcing initiative.

Most of the senior procurement executives, acquisition officials and

vendors we spoke with believed a publicly available source of information

on these contracts is necessary. Senior procurement executives from DHS

and DOD stressed the usefulness of a governmentwide clearinghouse of

information on existing contracts. Sixteen of the 17 contracting officers

we spoke with stated that having a publicly available listing of contracts,

for example, could reduce their market research time. For instance, one

official stated that it is a “hunt and search” effort to find contract vehicles

and that a central database would reduce market research time and allow

contract actions to be processed faster. An official from GSA told us there

is not enough information on currently available contracts, which requires

their contracting officers to rely on Internet searches and informal

discussions to locate contract vehicles. Furthermore, a number of vendors

we spoke with also stated they would favor a central source of

information on available contracts and believe this source would help

increase transparency.

Agency officials we spoke with said that if agencies could easily find an

existing contract they would avoid unnecessary administrative time to

enter into a new contract, which they said could be significant. One

official stated that if there were an awareness of what was available to use,

it would help to reduce their acquisition lead time. A Department of the

Navy procurement official told us that by awarding fewer larger contracts,

the Department of the Navy and DOD have created efficiencies resulting in

lower prices. The SARA panel report previously noted some of these

concerns, stating that too many choices without information related to the

performance and management of these contracts make the cost-benefit

analysis and market research needed to select an appropriate acquisition

vehicle impossible. This is particularly important given OMB’s June 2008

guidance on interagency contracting that requires agencies to make a

determination that using an interagency contracting vehicle is in their best

Page 20 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

interest; taking into account factors such as whether the vehicle is suitable

to meet their needs and provides the best value.

36

Governmentwide Policy on

MACs and Enterprisewide

Contracts Is Limited;

Agencies Use Various

Procedures to Establish

and Manage These

Contracts

Federal agencies operate with limited governmentwide policy that

addresses the establishment and use of MACs and enterprisewide

contracts. Federal regulations generally provide that an agency should

consider existing contracts to determine if they might meet its needs.

37

In

contrast, GWAC creation and management has governmentwide oversight.

OFPP, as part of OMB, exercises statutory approval authority regarding

establishment of a GWAC. Once established, agencies provide annual

reports to OFPP, as part of OMB, on GWACs. The senior procurement

executives we spoke with had mixed views on the proper role of OFPP in

providing clarification and oversight to agencies establishing their own

contract vehicles. For example, Army senior acquisition officials

representing the senior procurement official told us that the policy on

interagency contracting is not cohesive. In their view, OFPP should

provide policy and guidance that agencies would be required to follow.

They also think surveillance of interagency contracts is a major issue since

proper oversight is sometimes lacking. Similarly, officials from the Office

of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and

Logistics stated that OFPP is the right agency to take the leadership role

on strategic sourcing for services. They added, however, that OFPP might

not have sufficient staff to do so. In contrast, the Senior Procurement

Executive for the Department of the Navy pointed to agency-specific

circumstances or requirements that create uncertainty about the utility of

broad OFPP guidance.

The six federal agencies and the three military departments we reviewed,

responsible for almost 87 percent of total federal procurement obligations

in fiscal year 2008, have policies that require approval and review for

acquisition planning involving contracts for large dollar amounts which

would generally include the establishment of MACs and enterprisewide

contracts. The review process varies from agency to agency. For

36

OMB interagency contracting guidance issued in 2008 discusses how to use and manage

interagency contracts including how to place orders off of an existing contract. This

guidance provides that agencies shall ensure that decisions to use interagency acquisitions

are supported by best interest determinations before placing orders against other agencies

contracts. OMB Memorandum, Improving the Management and Use of Interagency

Acquisitions (June 6, 2008).

37

FAR § 7.105.

Page 21 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

example, an official from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for

Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics told us that any new DOD contract

estimated at over $100 million would be required to go through a review

process to ensure that no other contract exists that could fulfill the new

requirement. As another example, DHS requires that the senior

procurement executive approve the establishment of each enterprisewide

contract. The policy requires that each enterprisewide contract

coordinate requirements between operating entities and determine

administrative costs prior to approval.

Furthermore, agencies have issued guidance encouraging the use of

enterprisewide contracts rather than using interagency contracts. DOD

guidance on acquisition of services—accounting for over 50 percent of

DOD’s obligated contract dollars—advises that contracting officers

consider the use of internal DOD contract vehicles to satisfy requirements

for services prior to placing an order against another agency’s contract

vehicle. Similarly, DHS senior procurement executives told us that DHS

policy requires buyers to consider EAGLE and FirstSource—both DHS

enterprisewide contracts—before they go to other sources to fulfill

information technology requirements. In fact, OMB recently reported that

20 of the 24 largest procuring activities are planning on reducing

procurement spending by implementing strategic sourcing initiatives by

using enterprise contracting to leverage their buying power.

38

These

initiatives are part of the administration’s goal of reducing contract

spending by 7 percent over the next 2 years.

Departments and Agencies

Cite a Variety of Reasons

for Establishing MACs and

Enterprisewide Contracts

Instead of Using Existing

Contracts

Agencies we met with cited several reasons for establishing their own

MACs and enterprisewide contracts including cost avoidance through

lower prices, and fewer fees compared to other vehicles, mission specific

requirements, and better control over the management of contracts. As

shown in tables 3 and 4 below, when deciding to award a MAC or an

enterprisewide contract, agencies listed a number of reasons in the

acquisition plans for not using existing contracts.

38

Office of Management and Budget, Acquisition and Contracting Improvement Plans

and Pilots: Saving Money and Improving Government (Washington D.C.: Dec. 2009).

Page 22 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

Table 3: Selected Agencies’ and Military Departments’ Reasons for Establishing MACs and Enterprisewide Contracts in Lieu

of Using the GSA MAS Program

Multiagency contracts and

enterprisewide contracts

Purpose and Reason

GSA prices too high

Technology refresh delays due to

dependence on changes to MAS

contracts

Does not allow a range of

contract types, i.e., cost type

contracts or include required

contract terms and conditions.

Would require large number of

schedules

Cannot ensure products are in

compliance with DOD standards

Outside the continental United

States

Review and approval for the use

of non-DOD contract vehicles

MAC: Army Desktop and Mobile

Computing-2 (ADMC-2) (Approved

August 2005)

Provide commercial information

technology equipment to integrate,

modernize, and refresh the Army’s

existing architecture while providing

standardized interfaces.

X X X X X X

MAC: Army Information Technology

Enterprise Solutions-2 Hardware

(ITES-2H) (Approved June 2006)

Support the Army enterprise

infrastructure with a full range of state-

of-the-market information equipment

and incidental integration services.

Scope encompasses all requirements

for information technology.

X X X X X X

MAC: Army Information Technology

Enterprise Solutions-2 Services (ITES-

2S) (Approved September 2005)

Support the Army enterprise

infrastructure with a full range of

information technology services.

X

a

MAC: Defense Information Systems

Agency Encore II (Approved

December 2005)

Support the agency mission area

resulting in contracting solutions that

provide support of all functional

requirements including Command and

Control, Intelligence, and Mission

support areas, and to all elements of

the Global Information Grid.

X X

Enterprisewide contracts: Acquisition

of Services in support of the

Department of the Navy and Marine

Corps SeaPort Enhanced (SeaPort-e)

(Approved May 2005)

Facilitate the implementation of an

enterprisewide approach to the

acquisition of services to implement

cost-effective and integrated business

practices to better support the

Department of the Navy.

b

Enterprisewide contracts: Homeland

Security Enterprise Acquisition

Gateway for Leading-Edge Solutions

(EAGLE)(Approved August 2005)

Provide a comprehensive range of

information technology support services

for use throughout the agency through

a centrally managed program.

X

Enterprisewide contracts: Homeland

Security First Source (Approved

September 2005)

Provide access to a wide variety of

information technology products for use

throughout the agency through a

centrally managed program.

X

Source: GAO analysis of agencies’ acquisition plans.

Page 23 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

a

Can more effectively leverage industry to partner with the Army as opposed to utilizing GSA

schedules to conduct a large number of smaller acquisitions.

b

Analysis of alternatives was not discussed in the acquisition strategy.

Table 4: Selected Agencies’ and Military Departments’ Reasons for Establishing MACs and Enterprisewide Contracts in Lieu

of Using GWACs and MACs Identified by Agencies

Multiagency contracts and

enterprisewide contracts

Purpose and Reason

GWAC prices too high

Criticism regarding Agency

reliance governmentwide

acquisition contracts

Confusing for ordering

activities

Cannot ensure products are

in compliance with DOD

standards

Outside the continental

United States

Review and approval for the

use of non-DOD contract

vehicles

Create dependence on

external agencies

Vehicles do not include

required contract terms and

conditions

MAC: Army Desktop and Mobile

Computing-2 (ADMC-2) (Approved

August 2005)

Provide commercial information

technology equipment to integrate,

modernize, and refresh the Army’s

existing architecture while providing

standardized interfaces.

X X X X X

MAC: Army Information Technology

Enterprise Solutions-2 Hardware

(ITES-2H) (Approved June 2006)

Support the Army enterprise

infrastructure with a full range of

state-of-the-market information

equipment and incidental integration

services. Scope encompasses all

requirements for information

technology.

X X X X X

MAC: Army Information Technology

Enterprise Solutions-2 Services

(ITES-2S) (Approved September

2005)

Support the Army enterprise

infrastructure with a full range of

information technology services.

a

MAC: Defense Information Systems

Agency Encore II (Approved

December 2005)

Support the agency mission area

resulting in contracting solutions that

provide support of all functional

requirements including Command

and Control, Intelligence, and

Mission support areas, and to all

elements of the Global Information

Grid.

X

Enterprisewide contracts:

Acquisition of Services in support of

the Department of the Navy and

Marine Corps SeaPort Enhanced

(SeaPort-e) (Approved May 2005)

Facilitate the implementation of an

enterprisewide approach to the

acquisition of services to implement

cost-effective and integrated

business practices to better support

the Department of the Navy.

b

Page 24 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

Multiagency contracts and

enterprisewide contracts

Purpose and Reason

GWAC prices too high

Criticism regarding Agency

reliance governmentwide

acquisition contracts

Confusing for ordering

activities

Cannot ensure products are

in compliance with DOD

standards

Outside the continental

United States

Review and approval for the

use of non-DOD contract

vehicles

Create dependence on

external agencies

Vehicles do not include

required contract terms and

conditions

Enterprisewide contracts: Homeland

Security Enterprise Acquisition

Gateway for Leading-Edge

Solutions (EAGLE) (Approved

August 2005)

Provide a comprehensive range of

information technology support

services for use throughout the

agency through a centrally managed

program.

X X X

Enterprisewide contracts: Homeland

Security FirstSource (Approved

September 2005)

Provide access to a wide variety of

information technology products for

use throughout the agency through a

centrally managed program.

X X X

Source: GAO analysis of agencies’ acquisition plans.

a

The analysis of alternatives did not discuss GWACs or other MACs in the acquisition strategy.

b

Analysis of alternatives was not discussed in the acquisition strategy.

The following examples provide more detail about why agencies created

MACs and enterprisewide contracts shown in tables 3 and 4.

• The Army cited several reasons for establishing their ITES-2S and

ITES-2H contracts—MACs for information technology hardware and

services-in 2005 and 2006. The Army wanted to standardize its

information technology contracts so each contract would include the

required Army and DOD security parameters. According to the Army,

GSA contracts do not automatically include these security

requirements and using a GSA contract would require adding these

terms to every order. The Army also cited timeliness concerns with

GSA contracts and GSA fees as reasons for establishing their own

contracting vehicles.

• The Department of the Navy cited numerous reasons for setting up its

SeaPort Enhanced program, an enterprisewide contract, established in

April 2001. According to the Department of the Navy Senior

Procurement Executive, the Department of the Navy created this

program to reduce costs associated with buying services. Program

officials stated there were problems with interagency contracting and

wanted to make sure they had more control over their procurements.

They stated further that GSA’s fees made its schedules programs cost

prohibitive. The Department of the Navy officials also stated they

wanted more insight into their procurements, which they could not

Page 25 GAO-10-367 Contracting Strategies

gain when using the GSA schedules. Finally, the Department of the

Navy also wanted to be able to use cost-reimbursable contracts, which

are not allowed by the GSA’s MAS program. The Department of the

Navy felt this prohibition hindered their efforts to make their

acquisitions efficient.

• In 2005, DHS established EAGLE and FirstSource contracting programs

that both involve enterprisewide contracts used for information

technology products and services. Officials stated the main reason

these programs were established was to avoid the fees associated with

using other contract vehicles and save money through volume pricing.

In addition, the programs centralized procurements for a wide array of

mission needs among its many agencies. EAGLE was approved around

the time of Hurricane Katrina and DHS determined it would be easier

to coordinate assistance if the department had contractors together