March 2019

The findings and conclusions of this Working Paper reflect the views of the author(s) and have not been

subject to a detailed review by the staff of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Contact the Lincoln Institute

with questions or requests for permission to reprint this paper. help@lincolninst.edu

© 2019 Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

Designing Land Value Capture Tools in the

Context of Complex Tenurial and Deficient Land

Use Regulatory Regimes in Accra, Ghana

Working Paper WP19SB1

Samuel Banleman Biitir

University for Development Studies

Abstract

Rapid urbanization has increased the demand for urban infrastructure services. Municipalities

have attempted to finance infrastructure services with value capture instruments. The paper

highlights how value capture instruments are designed and implemented in Ghana. The study

used the case study strategy of inquiry and multiple case study design to locate the research

within the contexts of fiscal decentralization policies, urban planning and land tenure

frameworks. The paper concludes that the tax or fee-based land value capture instruments have

more chances of success if teething implementation challenges are addressed. The current

passive approach to urban development and the inability of metropolitan, municipal and District

Assemblies to enforce land use regulation does not promote the implementation of the

development-based land value capture instruments. Besides, the concept of land value capture is

not clearly understood in general among key stakeholders. The paper proposes a mutual gains

approach to resolving the teething implementation challenges for tax or fee-based tools.

Highlights of Findings

• Development charges and in-kind contribution have more potential for implementation in

GAMA

• There is a lack of awareness and initiative to implement tax or fee-based value capture

tools.

• Passive governance approach to urban land development promotes project-related value

capture through land and property sales by land developers.

• Complex land tenure system is affecting land use planning and enforcement of land use

regulations

• Parastatal and private land developers’ activities provide critical urban management and

development lessons for MMDAs for the implementation of land value capture

instruments in general.

Keywords: Land value capture, land-based financing, urban infrastructure, urban planning, land

tenure, land development approach, legal and institutional frameworks.

About the Author

Samuel Banleman Biitir is a lecturer in the Department of Real Estate and Land Management,

University for Development Studies. He is a professional member of the Ghana Institution of

Surveyors, Estate Surveying and Valuation Division. His research focuses on land governance,

housing and urban infrastructure finance.

PO Box UPW 57

UDS, Wa Campus

sbbiitir@gmail.com

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy – David C. Lincoln Fellowship in Land

Value Taxation Program for supporting this research. I thank Oliver Tannor, Ali Hashim, and

James Parimah for assisting me with the interviews. I also thank Joseph Ayitio and Dr. Samson

Aziabah for their detailed reviews and insightful comments on the final draft. I thank the

Municipal Engineers, Physical Planners and Budget Officers of the Ga East, La Dade Kotopon

and Kpone Katamanso Municipal Assemblies for the invaluable time they spent with my

colleagues and me sharing their views. I also thank the various experts from Tema Development

Company, Ghana Airport Company and Oak Villa Estate for their time. Finally, I thank the

various participants from the public and private sectors that participated in the research

dissemination workshop.

Table of Contents

Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1

Overview of Land Value Capture Instruments and Typologies .......................................... 2

Types of Land Value Capture Instruments ............................................................................ 3

Critical Success Factors for Implementation ......................................................................... 4

Pre-Requisite Conditions for the Implementation of Development-Based LVC ................... 6

Urban Development Context of Ghana .................................................................................. 7

Decentralization in Ghana .................................................................................................... 10

Urban Planning System ........................................................................................................ 10

Land Tenure and Administration System ............................................................................. 14

Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 15

Profile of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA) ................................................... 17

The Legal and Institutional Arrangements for Land-Based Revenue Generation ......... 21

Land-Based Revenues Generated at the National Level ...................................................... 21

Gift Tax............................................................................................................................. 21

Estate Duty and Inheritance Tax ...................................................................................... 21

Stamp Duty ....................................................................................................................... 21

Capital Gains Tax ............................................................................................................. 22

Rent Tax ........................................................................................................................... 22

Fiscal Decentralization and Land-Based Revenues ............................................................. 23

Stool Land Revenues ........................................................................................................ 23

Development Charge ........................................................................................................ 24

Development or Building Permit Fees ............................................................................. 25

Betterment Levies ............................................................................................................. 26

Property Rates................................................................................................................... 27

In-Kind Contribution ........................................................................................................ 28

The Contribution of Land-Based Revenues to Total IGF .................................................... 28

Implementation Challenges of Land Value Capture Instruments ........................................ 29

Technical and Administrative Challenges for Assessment and Collection ...................... 29

Knowledge Gap and Lack of Awareness ......................................................................... 30

Lack of Initiative and Social Entrepreneurial Mind-Set ................................................... 32

Inadequate Staff and Expertise ......................................................................................... 32

Inadequate Collaboration Among Inter-Governmental Agencies .................................... 33

Inability to Enforce Land Use Regulations ...................................................................... 35

Tema Development Company (TDC), Community 24 Case Study ................................... 37

Overview .............................................................................................................................. 37

Land Value Capture Via Project-Related Land Sales .......................................................... 39

Land Ownership and Local Land Use Planning ............................................................... 39

Funding Arrangement ....................................................................................................... 40

Collaboration and Partnership with Public Sector Institutions ......................................... 42

Evidence of Land Value Uplift ......................................................................................... 43

Strategy for Recovering Infrastructure Cost ..................................................................... 43

Administrative Arrangement and Support Services ......................................................... 43

Human Resources and Technical Expertise ..................................................................... 44

Target Beneficiaries .......................................................................................................... 44

Ghana Airport Company’s Airport City I Project Case Study ......................................... 44

Overview .............................................................................................................................. 44

Land Value Capture Via Project-Related Land Sales .......................................................... 46

Land Ownership and Local Land Use Planning ............................................................... 46

Financing Arrangement .................................................................................................... 48

Strategy for Recovering Infrastructure Cost ..................................................................... 48

Collaboration and Partnership with Public Sector Institutions ......................................... 49

Evidence of Land Value Uplift ......................................................................................... 49

Administrative Arrangement and Support Services ......................................................... 49

Human Resources and Technical Expertise ..................................................................... 50

Target Beneficiaries .......................................................................................................... 50

Oak Villa Estate Case Study ................................................................................................. 51

Overview .............................................................................................................................. 51

Land Value Capture Via Project-Related Land Sales .......................................................... 52

Land Ownership and Local Land Use Planning ............................................................... 52

Funding Arrangement ....................................................................................................... 54

Strategy for Recovering Infrastructure Cost ..................................................................... 54

Collaboration and Partnership with Public Sector Institutions ......................................... 54

Evidence of Land Value Uplift ......................................................................................... 54

Administrative Arrangement and Support Services ......................................................... 55

Human Resource and Technical Expertise ....................................................................... 55

Target Beneficiaries .......................................................................................................... 55

Observations on the Case Studies ......................................................................................... 56

Lessons from the Case Studies: Key Themes and Issues.................................................... 58

Land Value Capture Through Project Related Land Sales .................................................. 58

Local Land Use Planning and Enforcement of Planning Instruments ................................. 59

Urban Management and Development Outcomes ............................................................... 60

Funding Strategies for Urban Infrastructure ........................................................................ 61

Security of Land Tenure ....................................................................................................... 63

Collaboration and Partnerships with Key Stakeholders ....................................................... 63

Revenue Streams for Municipalities .................................................................................... 64

High-Quality Human Resource and Technical Expertise .................................................... 65

Strategies for Designing and Implementing Value Capture Instruments ........................ 65

Strategies for the Implementation of Tax or Fee-Based Instruments ................................... 65

Build the Requisite Technical Information and Requirements for Each Capture Tool .... 66

Identify, Assess, and Understand Stakeholders Issues and Interests ................................ 67

Design a Process of Collaboration with Key Stakeholders .............................................. 68

Design the Process of Deliberation for Building Trust Among Key Stakeholders .......... 69

Design the Process of Building Long Lasting Partnerships ............................................. 70

Strategies for the Design and Implementation of Project Related Land Sales ..................... 71

Strategies to Ensure Effective Municipal Level Land Use Planning and Enforcement ... 71

Develop Strategic Partnerships with Land Developers to Implement Project Related Land

Sales .................................................................................................................................. 72

Conclusion .............................................................................................................................. 74

References ............................................................................................................................... 77

List of Figures

Figure 1: Urban Population Growth (Pop. Millions) ................................................................. 8

Figure 2: Sustained Economic and Urbanization Growth Rates Since 1984 ............................. 8

Figure 3: Ghana, Sub-Saharan Africa and World GDP Growth Rates ...................................... 9

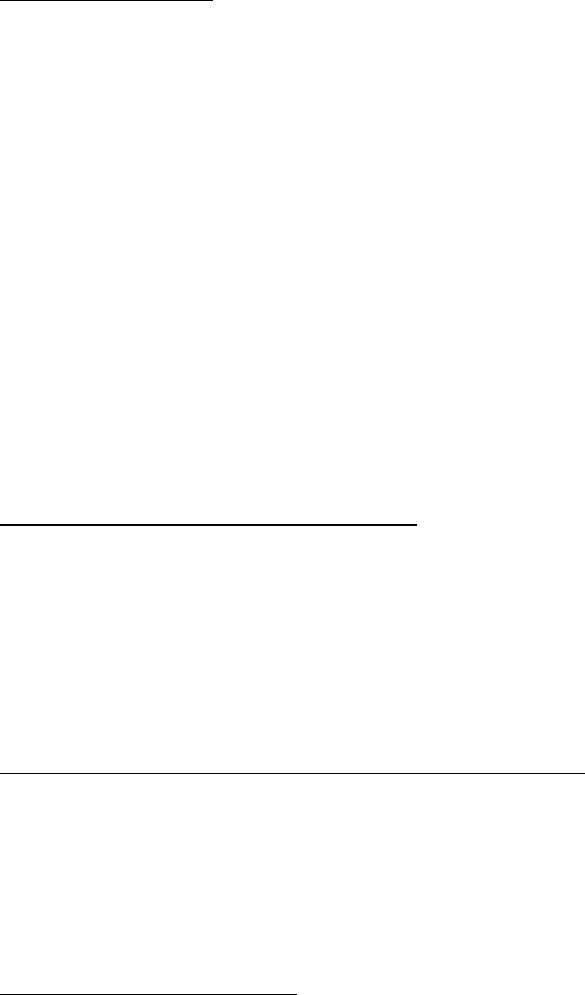

Figure 4: Governance Structure and Institutional Framework Under Act 480 ........................ 12

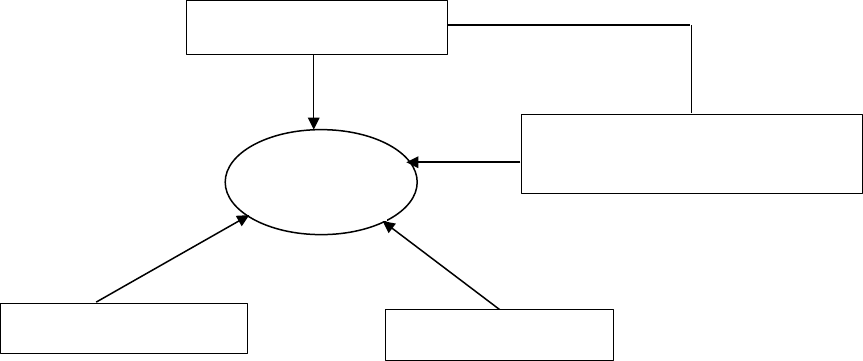

Figure 5: Three-Tier Spatial Planning Framework And Planning Instruments ....................... 13

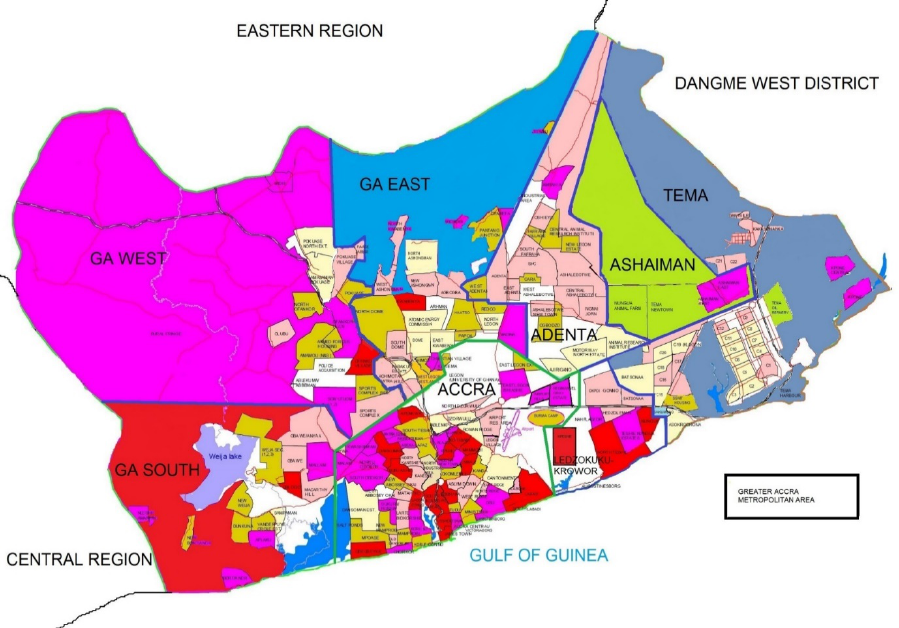

Figure 6: The Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA) ...................................................... 19

Figure 7: Tema Acquisition Area ............................................................................................ 38

Figure 8: Community 24 Land Use Scheme ............................................................................ 40

Figure 9: Sections of the Road Network .................................................................................. 42

Figure 10: Sections of Buildings Under Construction ............................................................. 42

Figure 11: Airport City I Land Use Plan ................................................................................. 46

Figure 12: Commercial Development of Airport City I .......................................................... 48

Figure 13: Typical Housing Development at Oak villa Estate ................................................ 53

Figure 14: Revenue Streams from Land Developers ............................................................... 64

List of Tables

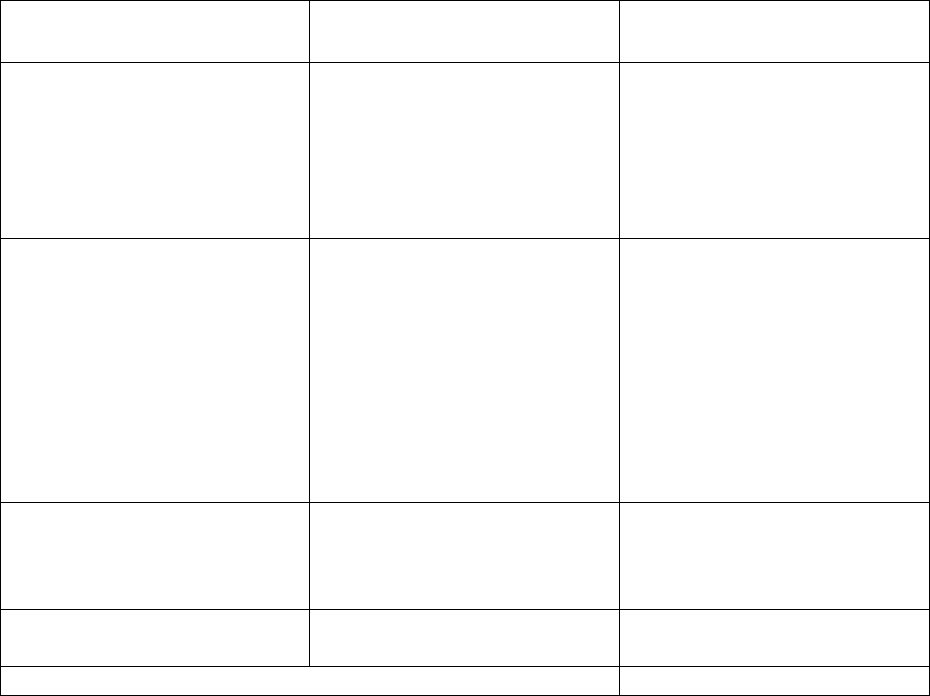

Table 1: Proliferation of Local Governments .......................................................................... 10

Table 2: Case Study Organizations and Local Government Administrative Areas................. 16

Table 3: Land Base Revenue to Total IGF .............................................................................. 29

Table 4: Construction and Property Registration Performance ............................................... 37

Table 5: Estimated Coverage Areas and Approximated Cost of Infrastructure ...................... 41

1

Designing Land Value Capture Tools in the Context of Complex Tenurial and Deficient

Land Use Regulatory Regimes in Accra, Ghana

Introduction

Ghana has experienced rapid population growth, urbanization and economic development over

the past three decades. These developments have influenced the development of Ghanaian cities

and affected land uses, land values and urban forms. The combined effect of these factors has led

to unplanned and uncoordinated spatial expansion leading to increased demand for urban

infrastructure. Yet, the necessary financial resources and competencies for local infrastructure

expansion simply do not exist to meet this challenge (Paulais 2012; World Bank 2015b). The

financing gap for urban infrastructure and services in most cities is widening. The World Bank

(2015) reports that Ghana’s urban infrastructure and services are expensive and the current level

of existing revenues are woefully inadequate. Already, there has been chronic underinvestment

in general infrastructure including transportation, water and power grids in countries around the

world over the years resulting in huge deficits especially in urban areas (Mckinsey Global

Institute 2013). Urban infrastructure is usually funded from traditional sources like central or

local government grants, donations, loans or taxes. This revenue base is already overstretched

(McIntosh 2014).

Nonetheless, land value capture tools have been used by local governments in most developed

and some developing countries as a revenue source to fund urban infrastructure (Ingram and

Hong 2012; Paulais 2012; Smolka 2013; Suzuki et al. 2015). Scholars and practitioners (Paulais

2012; Peterson 2009; Smolka 2013; Suzuki et al. 2015) have advanced arguments that land value

capture tools could be used to fund urban infrastructure through opportunities created by

urbanization. Smolka (2013) argues that urbanization paves the way for active urban land

markets and increased public investments in urban areas. Increased public investment in urban

infrastructure and services lead to high densities of urban areas, which creates significant land

value increases. Paulais (2012) echoed that urban extension generates increases in land value.

Thus, land with easy accessibility by road, utilities, or even public transportation service has a

greater increase in value.

Besides, Peterson (2009) asserts that land is a significant source of revenue for infrastructure

finance as the magnitude of revenue raised from land sales and other land-based financing

instrument is substantial. He posits that land-based financing thrives well where there is rapid

urban growth since land prices tend to rise rapidly in response to this growth. He echoes that this

creates an opportunity to generate sufficient revenue to finance the increasing infrastructure

needs that go with rapid urban growth.

Thus, land value capture instruments are increasingly perceived as a complementary source of

financing urban infrastructure financing gaps of rapidly urban cities in developing countries.

This perception is rooted in the argument that urban infrastructure provision impacts positively

on land values to a greater extent. Therefore, it is only fair to capture the monetized land values

to complement the financing of urban infrastructure. Given that most cities in sub-Saharan Africa

2

are characterized by complex land tenure regimes, deficient land use regulatory systems and

urban informality (Napier et al. 2013), the challenge of implementing LVC as a form of

financing urban investments is significant.

In this paper, I provide a contextual analysis of how land value capture instruments are

conceived and implemented by local governments in Accra, Ghana. I used multiple case studies

of three urban sites of intermediate scale located in three municipal assemblies within Greater

Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA) to explore the use of land value capture instruments in the

context of complex land tenure, and deficient land uses regulatory regimes. I focused on three

land development projects cases involving changing land uses in three local government areas

within GAMA. I used two propositions to guide the study. These are: (1) sound land use

regulatory framework enhances the process of land value capture; and (2) partnerships with land

development agencies create opportunities for land value capture.

The following section is divided into seven sections: (1) Overview of land value capture

instruments and typologies; (2) Urban development context of Ghana; (3) Methodology; (4)

Legal and institutional framework for land-based financing; (5) Overview of case studies and

findings, followed by a section on lessons learnt from land development cases on the

implementation of LVC; and finally, (6) Strategies for design and effective implementation of

land value capture tools in Accra.

Overview of Land Value Capture Instruments and Typologies

Land value capture is defined by Smolka (2013) as the recovery by the public of the land value

uplift (unearned income) generated by actions other than the landowner’s own investment. A

more elaborated definition is provided by Suzuki et al. (2015). They define land value capture as:

A public financing method by which governments (a) trigger an increase in land values

via regulatory decisions (e.g., change in land use or FAR) and/or infrastructure

investments (e.g., transit); (b) institute a process to share this land value increment by

capturing part or all of the change; and (c) use LVC proceeds to finance infrastructure

investments (e.g., investments in transit and TOD), any other improvements required to

offset impacts related to the changes (e.g., densification), and/or implement public

policies to promote equity (e.g., provision of affordable housing to alleviate shortages

and offset potential gentrification). (Suzuki et al. 2015, xxii)

However, land value capture (LVC) has been contrasted with land-based financing in that the

latter is a broader term that is used to describe how land revenues are used to finance

infrastructure projects. According to the African Centre of Cities (2015), land-based financing is

more encompassing than LVC in four different ways: (1) arrangements that result in

infrastructure being provided or financed by a developer; (2) special assessments that reflect the

cost of improvement that serves a property, regardless of whether these results in real increments

in the property's value, such as development charges ; (3) land and property taxes or rates; and

(4) transfer taxes imposed when land is bought and sold.

3

In this paper, I adopt both land value capture and land-based financing definitions because of the

crosscutting issues that have to do with not only recovery of the unearned income from

landowners but also the objective of using the captured values for funding urban infrastructure

by local governments. Besides, because of the implicit intention of some deliberate action by the

capturing authority to promote equity and inclusion as the case may be in LVC instruments, I

examined LVC in the context of Ghana to ascertain the relevance of this implicit intention. Also,

these definitions become relevant because of the increasing awareness of the potential of land

value capture finance created by the combination of factors that needed to be contextualized

within geographical peculiarities of cities and regions. For example, Smolka (2013) notes that

the concept of land value capture is gaining popularity in developing countries. According to

Smolka (2013), the growing popularity of the concept is conditioned by economic stabilization

and fiscal decentralization; improvement in urban planning and management; improvement in

political democratization, increasing social and civic awareness with regard to demands for

equity in public policy responses to growing societal needs; mutable assertiveness to

privatization and public-private partnerships in urban services delivery; the influence of

multilateral agencies like the UN-Habitat Global Land Tool Network (GLTN); and growing

freedom of local government to mobilize internally generated funds for local development. The

trends of urban development and the factors highlighted by Smolka (2013) put Ghana in this

perspective, and it is important to bring the discussion of land value capture finance in the

context of recent developments in the country.

Types of Land Value Capture Instruments

Various instruments have been used to capture unearned land and property value increment.

According to Suzuki et al. (2015), these instruments can be classified broadly into two categories

- Tax or Fee-based and Development-Based. Tax or Fee-Based Instruments include; property

and land tax, betterment charges/levies, and tax increment financing (TIF). The Development-

Based Instruments, on the other hand, include land sales or leasing, joint development,

development rights or air rights sale, land readjustment, impact fees or development exaction and

urban redevelopment schemes, amongst others. Smolka (2013) on the other hand, classifies these

instruments as either direct or indirect. Smolka’s classification clearly differs from Suzuki et al.

(2015) in terms of their constituents. The direct instruments according to Smolka are: betterment

contribution, land readjustment, public land leasing, land value tax, land value increment tax,

impact and development charges among others. The indirect instruments include: property tax,

special districts (BIDs), expropriation, exactions, land banking, tax increment financing (TIF)

among others.

The extent of use of these instruments depends largely on the progressive evolution of cities in

terms of the nature of land markets, type of infrastructure (basic or advanced), logistics and

technical capacities, and the level of financial sophistication (Africa Centre for Cities 2015;

Feinstein 2012; Mathur and Smith 2012; Roberts 2011; Rybeck 2004).

Among these myriad of tools for land value capture, Paulais (2012) is of the view that only three

of these are likely to have potential application in African cities. These include: a) direct land

transfers; b) direct contribution from owners or developers; and c) land added – value taxation.

According to Paulais (2012), direct land transfers are possible when the public owns the land

4

where it sells or leases the land to finance public infrastructure in and around major

infrastructure projects like airports and seaports. Direct contribution in-kind is where developers

or landowners give part of their lands for public use in return for the capital investment. The land

added value taxation comes in the form of betterment contribution where property owners that

gain or will gain from public works are made to contribute to the financing of the public works.

This betterment levy is largely successful in Columbia where the calculation is based on three

parameters: a) the cost to build the project; b) the value added to the property attributed to the

project; and c) the affordability of the project ( Coleman and Grimes 2010; Paulais 2012; Smolka

and Amborski 2001; Smolka 2013)

According to the African Centre of Cities (2015), development charges are seen as having likely

potential application and success in African cities. Thus, the tools that have been utilized in the

advanced countries cannot be of universal application in the context of developing countries with

context-specific peculiarities. What is apparent in the views of pundits on the type of land value

capture tools workable in Sub-Saharan Africa is that the development-based tool has a high

degree of success because of the current political economy of land development in these

countries.

Critical Success Factors for Implementation

In reviewing case studies of cities that have implemented the Development-based LVC, Suzuki

et al. (2015), come to a conclusion that certain critical factors deserve careful attention for

successful implementation. One such factor is inclusive value creation. Suzuki et al. (2015) share

the view that land value creation is multifaceted and involves multiple stakeholders. Therefore,

capturing the value created by multiple stakeholders’ decisions requires extensive consultation,

inclusion, and participation. Unlike the Tax-based instruments where the government can take a

unilateral decision on imposing taxes, Development-based LVC requires consultation and

negotiations with multiple stakeholders. Thus, incentives and motivation of multiple stakeholders

in the urban land development process facilitate the design and implementation of the

Development-based LVC. These stakeholders should agree on the land value uplift upfront based

on market trends and decide on how the land value uplift is captured and shared among the

various principal stakeholders. The sharing of value increment entails negotiations among

stakeholders based on their relative contribution to the process of the land value uplift (Suzuki et

al. 2015)

Besides, the development-based LVC is a value creation tool and not a simple sale of public land

and leasing of land use rights (Suzuki et al. 2015). It requires strategic public land use planning

and orientation, especially in cities where the state owns the land, and a strategic choice on

whether to separate raw land production from land development and servicing (Paulais 2012).

The choice of separating raw land production from development and servicing is an

implementation model where the local government can decide to create land values by

transforming rural land to urban land use either through a land operator or land developer. The

raw land production process involves land readjustment strategies that seek to organize peri-

urban or rural land and plan it adequately for urban uses. Therefore, the extent to which local

government has a proprietary interest in public land determines the viability of the option to

implement the development-based LVC. However, Suzuki et al. (2015) add that public

5

ownership of land, though important, is not a necessary precondition. Where the state does not

own land, local government can expropriate private land through various innovative ways such

as land readjustment and land banking. However, what is important is that there must be a

strategic public land use aimed at ring-fencing the proceeds of public land sales and leasing for

funding some urban infrastructure.

Furthermore, sound operation systems that engage land development agents and act as a liaison

between local governments and private landowners facilitates the implementation success of

development-based LVC. Paulais (2012) analyzed the experiences of other continents and

concluded that there are two operation options in the implementation of the development-based

LVC. These operation options require a land operator, who acts as an intermediary between local

government and land developers and investors. It can sometimes take the place of local

government to negotiate with private landowners for land development and servicing (Paulais

2012). Thus, the choice of an operation option will depend on the role the land developer is

required to play. It also depends on whether local governments separate raw land production

from land development and servicing so that the two functions are played by different entities in

the land value creation process.

According to Paulais (2012), the aim of the land operator is twofold. First, make urban land

available by transforming raw, rural land or restructuring existing parcels and manage the entire

process. Second, create reserves of land for the local government. In addition, there are certain

advantages that inure to local government when they cooperate with the land developer in the

implementation of development-based LVC. First, the local government is able to outsource the

cost of project implementation to the developer. Second, it will have the benefit of working with

professionals of specialized land operations to ensure the effective implementation of the project

(Paulais 2012). Therefore, the role of the land developer is paramount in the implementation of

the development-based LVC.

In addition, the land operator functions as both an operator and a land developer. According to

Paulais (2012), as an operator, it holds and manages acquired assets before it retrocedes them to

the local government or land developers. Its source of revenue is through commission and fees

from transferred land to local government or developers. When the operator functions as a land

developer, it services and develops land for sales. Its source of revenue is through sales of

serviced and developed lands. Paulais (2012), highlights the need to separate these functions.

This separation is important concerning the issues of who finances the operator and how the

operator is paid in the implementation of the development-based LVC. The separation of the

functions of the land operator is justified by the nature of activity and expertise they possess.

Thus, the nature of the function of the land operator depends on country-specific conditions and

varies by configuration and by the scope of the intervention (Paulais 2012). Country-specific

conditions may include the legal and institutional frameworks of land ownership and land use

management. Based on these, land operators and developers may develop as offshoots of the

central government or local government. They may be a public or parastatal organization or even

private organizations depending on the local laws of the country. In addition, depending on the

scope of the intervention, the land operator and land developer functions may be combined in

one entity such as land development corporations (Paulais 2012).

6

Pre-Requisite Conditions for the Implementation of Development-Based LVC

Scholars have demonstrated that land-based financing in general has great potential in

developing countries where there are active land and property markets and good urban

governance (Palmer and Berrisford 2015; Paulais 2012; Peterson 2009; Roberts 2011). Suzuki et

al (2015) work on financing transit-oriented development with land values highlights the

potential application of the development-based LVC in developing countries. Drawing on

experiences and lessons from case studies of some developed countries, Suzuki et al. (2015)

echoed that the development-based LVC is suitable for developing countries. They argue that

adapting and implementing the development-based LVC requires certain enabling factors. These

include sound demographic and macroeconomic fundamentals, visionary master plans and sound

and flexible planning, intergovernmental collaboration, entrepreneurship, and clear, transparent

regulatory and institutional factors. These factors are encapsulated into “active land and property

markets and good urban governance.”

Sound demographic and macroeconomic fundamentals entail rapid urbanization and strong

economic growth that creates high demand for land and property. It creates a spatial

configuration that requires significant investment in urban infrastructure. In addition, it leads to

the emergence of middle-class households with effective demand for urban housing. This propels

large-scale land development activities with the necessary housing infrastructure (Suzuki et al.

2015). The activities emanating from this demographic and strong macroeconomic growth lead

to increases in land values in urban areas. In Sub-Saharan Africa, these conditions are becoming

more favorable in recent years and hence the advocacy for development-based LVC (Berrisford,

Cirolia, and Palmer 2018; Paulais 2012).

Visionary master plans and sound, flexible land use planning also facilitate the implementation

of the development-based LVC. According to Suzuki et al. (2015), long-term strategic vision of

the country incorporated in a master plan guides both economic and spatial development, and

channels resources into more focused development oriented interventions. Suzuki et al. (2015)

posit that global good practice cities implementing decades of master plans have identified major

transit investments as backbones to urban development. Therefore, Sub-Saharan Africa cities

with visionary master plans that identify major infrastructure corridors’ investments can draw on

the synergies between the impacts of these investments and land values. This will facilitate the

implementation of land use planning instruments that incorporate raising additional funds from

development-based LVC.

Furthermore, effective intergovernmental collaboration enhances the chances for successful

implementation of development-based LVC. Land value creation results from multiple actors,

actions and strategies most often facilitated by more than one governmental agency. Therefore,

the strategies to capture land values requires effective collaborative relationships and actions

(Suzuki et al. 2015). Cities, where there is a history of effective intergovernmental collaboration

in projects design and implementation enhances the opportunities for them to deliver innovative

projects, especially in large-scale land development projects. Thus, the design and

implementation of development-based LVC needs expertise and effective intergovernmental

collaboration that is able to manage the conflicting of interests of project actors.

7

Intergovernmental collaboration ensures that there are effective stakeholder engagements,

consultation and consensus-building around urban infrastructure investment and implementation.

Again, the ability of city governments to imbue creative and innovative entrepreneurial mindset

in the midst of limited local government revenues is critical to the success of the development-

based LVC (Paulais 2012; Roberts 2011; Suzuki et al. 2015). According to Suzuki et al. (2015),

the development-based LVC originated from an entrepreneurial undertaking by city governments

in the United Kingdom and the United States of America in the mid-19

th

century. Thus, local

government authorities in developing countries need to become entrepreneurial in the

implementation of development-based LVC. They should develop long-term strategies and

models for generating additional revenues from land value increments.

Urban Development Context of Ghana

Ghana has experienced rapid urban population growth over the last three decades. The total

population of the country more than doubled between 1984 and 2013 (World Bank 2015).

According to the World Bank (2015), the urban population more than tripled, rising from 4

million to 14 million people over the same period (Figure 1). The urban population growth has

been phenomenal in the total number of growing urban areas since 2000. The total number of

urban areas with a population between 50,000 and 100,000 increased from nine towns in 2000 to

36 in 2010. This urban growth has been concentrated in smaller cities rather than in the larger

ones (World Bank 2015). Thus, the rate of urbanization rose from 31% to 51% between 1984

and 2013 making the country more urban compared with West Africa and the global averages

(World Bank, 2015). According to the CAHF (2018), Ghana’s urban population is projected to

grow by 3.4% a year due to both natural growth and internal migration. Fortunately, this rapid

population growth and urbanization have coincided with stable economic growth in Ghana. Over

a period of three decades, the country has witnessed steady growth in the Gross Domestic

Product (GDP). For instance, the average GDP growth rate between 1984 and 2005 was 5.7%

annually; between 2005 to 2013 GDP averaged 7.8%, and between 2013 to 2017 it averaged

5.0% (Ghana Statistical Service 2018; World Bank 2015). Thus, according to the World Bank

(2015), the GDP growth rate has never fallen below 3.3% since 1984 (Figure 2).

8

Figure 1: Urban Population Growth (Pop.

Millions)

Figure 2: Sustained Economic and

Urbanization Growth Rates Since 1984

Source: World Bank (2015) Source: World Bank (2015)

Besides, Ghana was ranked as the fastest growing economy in Sub-Saharan Africa and one of the

fastest in the world in 2011 when it recorded a GDP growth rate of 14.4%. However, since then

the economy plummeted due to world economic shocks and falling commodity prices. In 2014,

GDP was 4% and rose marginally to 4.1% in 2015, but even then, it was higher than the Sub-

Saharan Africa average GDP growth rate of 3.8% (Figure 3).

This impressive performance of the economy in the midst of volatility in the global economy has

precipitated the current spatial patterns of development in the country. For example, the Ghana

Investment Promotion Centre estimates that about 85,000 transactions are recorded per year in

luxury residential real estate with an estimated value of US$1.7 billion ( CAHF 2018b; Mega

Africa Capital 2013). The residential real estate market segment is the largest, and it is estimated

to be the fastest growing sector within Ghana’s real estate market (Mega Africa Capital, 2013).

This market segment is made up of high-end, middle-income, and low-income brackets. There is

an increasing local demand for residential estate as urban population increases. These dynamics

in the real estate sector have influenced the current pace of urban expansion in many cities in

Ghana (CAHF, 2018).

The services sector is the largest contributor to GDP. It accounted for 54.6% of GDP in 2015,

56.8% in 2016 and 55.9% in 2017. Industry and Agriculture contributed 25.6% and 18.9%

respectively to GDP in 2017 (GHL 2016; GoG 2018). Real estate, which comprises land,

residential, commercial, industrial, and hospitality, contributed approximately 5% of GDP in

2013 and is the 4

th

largest contributor to the services sector (Mega Africa Capital 2013).

However, the real estate subsector growth performance also plummeted in 2015 from 7.7% to

3.8% in 2016 and rose marginally to 4.2% in 2017 (GoG 2018).

9

Figure 3: Ghana, Sub-Saharan Africa and World GDP Growth Rates

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook 2016.

In addition, the relatively stable economic growth and urbanization rates over the years have also

created urban economic opportunities that have influenced rural-urban migration, thereby

making these urban areas attractive to migrants. These opportunities led to an influx of migrants

to Ghana’s urban areas. This influx did not necessary create unemployment in these areas (World

Bank 2015). It is worth noting that urban unemployment rather fell by 1.5% between 2000 and

2010. The World Bank indicates that the major cities in Ghana witnessed a decline in urban

unemployment rates despite increased migration. Besides, urban migration has also changed the

structure of Ghana’s economy from its dependence on subsistence agriculture for employment to

industrial and services sectors. Thus, employment in industry and services sector increased from

38% to 59% between 1992 and 2010 (World Bank 2015).

Furthermore, improved economic growth and urbanization have decreased urban poverty levels

and increased access to basic infrastructure services. According to the World Bank (2015), the

total poverty incidence dropped below 25% in 2013 and below 11% for urban areas. Access to

basic urban services including electricity, water, and waste management services improved from

30% in 2000 to 70% in 2010 for electricity connectivity for small towns. Peri-urban Accra has

witnessed increased access to electricity from 60-75% in 2000 to 86-92% in 2010. These

improvements resulted from rapid economic growth and urbanization, which led to job creation,

especially non-farm enterprises in urban areas.

However, rapid urbanization in Ghana has also resulted in many challenges. The GoG/MLGRD

(2012) list a myriad of challenges confronting urbanization and management of urban centers in

Ghana. These challenges are encapsulated into three main themes consisting of productivity,

inclusion and institutions (World Bank 2015). The first theme, productivity, includes

overconcentration of growth and development in a few cities, weak urban economy, land use

disorders and unplanned urban expansion, weak rural-urban linkages, inadequate urban

investment and financing, and weak urban transportation planning and traffic management. The

second, urban inclusion relates to increasing urban insecurity, urban poverty, slums and squatter

settlements, increasing environment deterioration, and inadequate urban infrastructure and

services. The third theme is institutions related. This consists of weak urban governance and

institutional coordination, weak information, education and communication strategy, limited data

10

and information on urban centers, delimitation of urban areas of jurisdiction, and lack of

integrated planning across jurisdictional boundaries.

Decentralization in Ghana

As a response to the emerging socio-economic development of the country, the Government of

Ghana has been pursuing decentralization policies in line with democratic governance principles

since 1988. The aim of these policies is to enhance political participation and improve social and

infrastructure services at the local levels. Decentralization has been pursued from three levels:

(1) political; (2) administrative; and (3) fiscal. However, over the years, government attempts to

meet the needs of the growing population and rapid urbanization, have led to the proliferation

and fragmentation of Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) (Owusu

2015). For example, the last decade has witnessed considerable increases in the number of

MMDAs. The number of MMDAs more than doubled from 110 in 1988 to 254 in 2018 (Table

1).

Table 1: Proliferation of Local Governments

Year

Number of Local Governments

Total

Increase

Metropolitan

Municipal

District

1988

3

-

107

110

-

2004

4

10

124

138

+28

2008

6

40

124

170

+32

2012

6

49

161

216

+46

2018

6

81

167

254

+38

Source: updated from Owusu (2015).

The significance of this proliferation and fragmentation is that it weakens the financial resource

base, especially internally generated funds (IGF), of MMDAs. This has negatively impacted

urban infrastructure service delivery as many of the newly created MMDAs lack an adequate

IGF revenue based for service provision (Cities Alliances 2017). The proliferation has also led to

the over dependence of these MMDAs on central government transfers. The central government

transfers have been fluctuating in recent times, further affecting the infrastructure development

of newly created MMDAs. The Greater Accra Metropolitan Area has witnessed continuous

fragmentation and proliferation of MMDAs out of the already existing ones in a bid to ensure

that basic service delivery reaches the population and local governance at the grassroots level.

Urban Planning System

The urban planning system in Ghana is rooted in colonial legacies, typified by the old British

model of town planning. The initial focus of urban planning was more of development planning

where the concentration was on natural resource exploitation. Plans focused on the development

of infrastructure and social services were clearly targeted at the development of hydroelectricity

projects, delivery of public services, and town improvement through housing development

schemes (Acheampong 2019). Planning was concentrated in the resource-rich southern sector of

Ghana where geographic areas were mapped for major infrastructure projects in order to achieve

11

specific development objectives (Acheampong 2019; Fuseini 2016). However, because these

plans were focused on physical infrastructure development, which had an expression in spatial

terms, Acheampong (2019) describes it as the beginning of spatial planning or urban planning in

Ghana.

Formal urban planning was introduced in Ghana by the promulgation of the Town and Country

Planning Act (CAP 84), 1945. This Act introduced the urban planning instruments that sought to

guide the orderly and progressive development of land, towns and other areas with the aim of

preserving and improving neighborhood amenities and related matters. The Act established the

symbiotic relationship between physical developments in relation to land. The Act used planning

schemes or layout plans and development permitting to regulate physical developments. In

addition, Cap 84 established the institutional framework for spatial planning by establishing the

Town and Country Planning Department (TCPD) as the spatial planning unit in the country. The

1945 Act and its subsequent amendments further introduced procedures for urban planning. One

of such procedures was that an area had to be declared a ‘Designated Planning Area’ before a

land use plan could be prepared for that area.

The Minister in charge of town planning was given the power to consult with local authorities

and declare the local authority jurisdiction as a planning area by executive instrument. This gave

the Minister responsible for town planning discretionary powers to decide which town, village,

or neighborhood had to benefit from land use planning (Acheampong 2019). This situation had a

profound impact on the physical development of town and cities in Ghana in the sense that areas

that did not receive the minister’s attention and approval continued with physical developments

without a land use plan. This situation persists in in most parts of Ghana today. It marked the

beginning of deficient urban planning in Ghana, where many physical developments precede

urban planning.

The 1945 Act introduced a highly centralized planning system where decisions regarding

planning at any local government authority had to be approved by the minister responsible for

town planning. Though this type of system favored strategic infrastructure development

throughout the country (Fuseini 2016; Fuseini and Kemp 2015), in the case of residential

neighborhood development, it created bureaucracies and denied many the benefits of land use

planning. Moreover, Cap 84 introduced a piecemeal urban planning approach as the practice of

declaring planning areas meant not all areas that qualified for land use planning had access to it

(Acheampong 2019).

Having practiced centralized urban planning for decades, the dispensation of decentralization in

the African continent and in Ghana, in particular, paved the way for decentralized planning. In

1988, the decentralization program was initiated to introduce reforms in local governance

structure and to encourage and increase local-level participation in the development process. The

local government law (PNDC Law 107) which was subsequently replaced by the Local

Government Act (Act 462), 1993 granted administrative powers to local authorities and

mandated them to take charge of local development overall, including planning. In 1994, the

National Development Planning System Act, Act 480 was enacted to provide the legal basis for

planning at all levels of government. According to Acheampong (2019), these two laws set up

12

the new institutional framework for planning (Figure 4) and defined the nature and scope of

planning in Ghana.

The National Development Planning Commission (NDPC) was established in 1994 to perform

the functions of socio-economic, environmental and physical planning as a single task. However,

the NDPC concentrated on addressing economic planning at the national and regional levels with

little attention given to spatial planning. According to Acheampong (2019) the introduction of

development planning by Act 480 led to the neglect of spatial planning at the national and

regional levels of political administration.

Source: Adapted from Acheampong (2019, 46).

Thus, Act 480 and 462 introduced two types of planning systems in the country. The first is

development planning that emphasized economic planning at the national level and monitored

the activities of Regional Coordinating Councils. Second, is land use planning at the district

levels with a narrow focus on the preparation of planning schemes or layout for neighborhoods

in town and cities and development controls (Acheampong and Ibrahim 2016). This created a

situation where there were no coordinated efforts to synchronize crosscutting issues between

development planning and spatial planning. Therefore, the preparation of land use plans at the

local levels was reduced to assisting landowners to sell their lands as plans virtually had no

bearing on the socio-economic realities of MMDAs (Acheampong 2019). These lapses and other

factors led to the promulgation of the Land Use and Spatial Planning and Local Governance Acts

in 2016.

The deficiencies identified with the spatial planning system in the country led to several reform

processes. The Land Administration Project (LAP), which started in 2003, incorporated a

component on Land Use Planning and Management Project (LUPMP). This led to the

promulgation of the Land Use and Spatial Planning Act, Act 925 in 2016. The act addresses most

of the deficiencies in the earlier planning instruments. This new planning law has declared the

entire country as a potential planning area in contrast with Cap 84. The law further embraced the

Figure 4: Governance Structure and Institutional Framework Under

Act 480

National

Regional

District

National Development Planning

Commission and sector ministries

Regional Coordinating Councils

(RCCs)

District Planning Authority

District Planning Units (DPUs)

Political Administrative

Levels

NDP (system)

Act 480 (1994)

13

use of land use and spatial planning to inculcate in its scope a new tradition of integrated and

multi-scale planning (Acheampong 2019). The law has also introduced an institutional

framework to recognize spatial planning at the various levels of political administration while

maintaining the three-tier institutional set-up under Act 480.

The new planning law has also broadened the scope of the three-tier institutional framework to

include national, regional and district spatial development frameworks (figure 5). The effect of

this law is that, a three-tier hierarchical system of spatial planning instruments has been

introduced.

Source: Acheampong (2019, 52)

This three-tier spatial planning framework synchronizes district level plans with national

development objectives. Thus, the new spatial planning law has provided the legal requirements

for the preparation of spatial planning frameworks at all levels of political administration and

prescribed the required standards for each framework as well as the synergies between the

different levels of planning. What is important to note is that structure, and local plans are the

main planning instruments recognized and emphasized in the new law. Each MMDA is expected

to develop a District Spatial Development Framework in line with the national and regional

Spatial Development Frameworks. MMDAs are required by law to review this framework every

five years.

Joint or Multi-districts Spatial

Development Framework

National Spatial

Development Framework

(NSDF)

Regional Spatial

Development Framework

(RSDF)

District Spatial

Development Framework

(DSDF)

Joint or Multi-regional Spatial

Development Framework

Structure Plans

Local Plans

Figure 5: Three-Tier Spatial Planning Framework and Planning

Instruments

14

From the District Spatial Development Framework, the MMDA will then develop structure and

local plans. The main tool employed in the structure plan is zoning. The Ministry of

Environment, Science and Technology (MEST) and the Town and Country Planning Department

(TCPD) have created the Zoning and Planning Standards Guidelines to ensure that both Structure

and Local Plans conform to these standards. These standards prescribe acceptable and

permissible use and form in which development may occur in a planned area. The zoning and

planning standards by the TCPD has identified 25 land use development zones and has also

introduced a color coding system for various land use zones (MEST/TCPD 2011).

Land Tenure and Administration System

Land tenure and land administration in Ghana is peculiar and complex. The land tenure system

reflects the unique traditional political institutions and socio-cultural differences of tribes, clans

and families that acquired various interests in land through wars, conquest and assimilation and

first settlements (Ministry of Lands and Forestry 2003). Within the traditional context, land

ownership is inter-generational and transcends the living to include the dead and those yet

unborn. It has spiritual and religious connotations and therefore, dealings in land must reflect

these peculiarities. These peculiarities also informed the various land tenure systems in the

country. Thus, there are different types of land tenure systems and land holdings, acquisition, use

and disposal, which vary from one geographical area to another (Ministry of Lands and Forestry,

2003). These translate into different interests in land that are either derived from Ghanaian

customs or assimilated from English common law and equity.

The prevailing land tenure system in Ghana can be divided into two broad categories based on

land ownership, control and management. These are public land and customary land. Within the

public land tenure system, there are two variants. The first is state land, where the ownership,

control and management are vested in the President and held in trust for the people of Ghana.

The mechanism through which land becomes public under this variant is the State exercises its

constitutional or statutory power of eminent domain to acquire lands compulsorily from

customary landowners for the general public interest. The constitutional and statutory laws

governing the compulsory acquisition of land are article 20 of the 1992 Republican Constitution

of Ghana, State Lands Act, 1962, Act 125, and the Land Statutory Wayleaves Act, 1963, Act

186. The Public and Vested Land Management Division (PVLMD) of the Lands Commission

manages this type of public lands on behalf of the President. It is estimated that this type of

public land constitutes 18% of the total land in the country. The second variant of public land is

vested land. In this type, the landowner retains the customary ownership, but the State takes

control over the management of the land under special statutory intervention. The management

responsibilities of the state on this type of land include legal, financial and physical planning.

The mechanism by which land become vested in the state is by statutory law, the Lands

Administration Act, 1962, Act 123. It is estimated that this type of lands constitutes 2% of the

total land mass. The PVLMD manages this on behalf of the customary landowners. Thus, both

state and vested lands constitute about 20% of the total land mass of Ghana (Kasanga and Kotey

2001; Kasanga et al. 1996; Kasanga 2002).

Customary land constitutes about 80% of the total landholdings in the country. It comprises of

stool, skin, clan, family and individual lands. The stool and skin symbolize traditional political

15

institutions headships and socio-cultural orientations. It has the trait of communal ownership

with tenets of inter-generational ownership, and the allodial

1

title or freehold resides in the

community, clan or family. This allodial title is non-transferable (Ministry of Lands and Forestry

2003) and the community, clan or family head holds the land in trust for the entire community,

clan or family. Thus, land ownership, control and management in Ghana are in the hands of

stools, skin, clan or family heads who hold the land in trust and therefore manage it as a fiduciary

duty. This trusteeship role is recognized by the state through a constitutional provision. Article

38(8) of the 1992 Republican Constitution of Ghana states:

The state shall recognize that ownership and possession of land carry a social obligation

to serve the larger community and, in particular, the state shall recognize that the

managers of public, stool, skin and family lands are fiduciaries charged with the

obligation to discharge their functions for the benefit respectively of the people of Ghana

of the stool, skin or family concerned, and are accountable as fiduciaries in this regard.

(Republic of Ghana 1992, 33)

Stool and skin lands have been subjected to constitutional and legal restrictions in attempt to

limit trustees’ control especially over the disposition of land and revenues accruing thereof.

Article 267 of the Constitution stipulates that any grant of stool or skin land to non-member must

receive the concurrence of the Lands Commission. Also, concerning revenues accruing on such

lands, the constitutions mandates the Office of the Administrator of Stool Lands (OASL) to

collect all revenues, royalties, dues, fees for and on behalf of the stool or skin. However, there

are no restrictions on family, and individual lands as these lands are implicitly referred to in the

constitution as private properties. Family and individual lands constitute about 35% of the

customary land holdings (Ministry of Lands and Forestry 2003).

In conclusion, land administration and management are governed by customary practices and

enacted legislation in Ghana. Thus, the state, indigenous land governance institutions,

communities, families and individuals all have vested interest in land (Acheampong 2019; Biitir

and Nara 2016). The customary land sector is made of complex layers of ownership rights vested

in different stakeholders. In most instances, these complex layers are found in one geographical

location making it difficult to identify the rightful owners to deal in land transactions.

Methodology

The research sought to examine how land value capture instruments could be designed to raise

additional financial resources for MMDAs to augment the financing of public infrastructure

within GAMA. It examined the legal and institutional infrastructure for land value capture. It

further assessed the impact of urban infrastructure provision on land values in three purposely

selected urban sites in three municipalities. Lastly, the study analyzed how land value capture

1

Allodial title is the highest proprietary interest known to Ghanaian customary law, beyond which there is no

superior title. It is sometimes referred to as the paramount or absolute title. It can be likened to the freehold interest

in English common law system. Other lesser titles to or interest in or right over land are derived from the allodial

interest (Ministry of Lands and Forestry, 2003)

16

tools can be tailored to the context specificities of GAMA to raise additional financial resources

for MMDAs.

The study adopted the qualitative epistemological paradigm that recognizes the importance of

locating the research within a particular context. This context could include national, socio-

economic and historical. In Ghana, political, fiscal and administrative decentralization, urban

planning and land markets have occurred within the historical, national and socio-economic

contexts. The case study strategy of inquiry was used, and the multiple case study design was

employed. The case studies were selected based on a blend of projects that are implemented with

both intended and unintended objectives of capturing land value increment, in different sites

comprising different tenurial regimes (customary & statutory) and under different local

government administrative areas within the GAMA.

The study adopted a three-stage process in selecting and analyzing land value capture practices.

The first stage involved the selecting of local government authorities within GAMA. This stage

involved the contextual analysis of the current legal and institutional frameworks of local

governance and land use management, land development and infrastructure provision. This

formed the baseline analysis of the current situation. Data from secondary sources on trends of

spatial development, availability of peri-urban land, inner-city redevelopment opportunities in

GAMA, and the presence of real estate developers or land developers undertaking various

housing development activities were analyzed. The information led to the selection of suitable

local government authority. Besides, based on the baseline analysis, the land developers

functioned as land developers or real estate developers (Paulais 2012) and therefore, for the

purpose of this paper land developers or real estate developers are used instead.

The second stage involved the selection of land developers. Both public and private developers

were purposely selected based on: (1) history and scale of operation; (2) the context of land

developer establishment; and (3) location of land developer operations. Thus, one estate

developer was selected in each municipality (Table 2).

Table 2: Case Study Organizations and Local Government Administrative Areas

Land Development Agency

Nature of

Organization

Name of Urban

Site

Local

Government

Area

1.

Tema Development Company

Parastatal

Community 25

Kpone-Katamanso

Municipal

Assembly

2.

Ghana Airport Company

Parastatal

Airport City

Redevelopment

La Dade-Kotopon

Municipal

Assembly

3.

Oak Villa Estate Company

Private

Developer

Abokobi

Ga East Municipal

Assembly

Moreover, land developers implementing the selected land development projects were profiled.

This entailed describing the project schemes, land values before and after the completion of the

17

projects, type and cost of urban infrastructure provided, and financing arrangements. It further

described in detail the implementation of land use scheme, its impact on land values and how the

estate developers capture potential or actual increases in land values, the availability and

ownership structure of the land, partnership models between land developers with original

landowners and the municipal government that has the official mandate for land use planning

were described.

The third stage involved the interpretative analysis of the first and second stages. This stage

entailed two levels of analysis. The first was the expert interpretation of the output of the

contextual and profile analyses of land developers. The practice of value capturing was analyzed

from two levels. The first level of analysis examined how local government in a selected

development scheme generally captures the land value increment. It examined the types of land-

based revenues currently available to local governments, the assessment and collection of these

revenues, and the capacities of the local government to assess and collect these revenues. It

analyzed the tools that local governments use to capture potential or actual land value increments

resulting from urban infrastructure provision. The second level of analysis within the expert

interpretative analysis was on how the land developers access land and finance land development

projects, what their strategies are for capturing land value uplift, and the lessons that can be

learnt from these land developers.

In addition, there was stakeholder interpretation of the findings. This involved a presentation of

the findings to the key stakeholders in a stakeholder dissemination workshop held at the Institute

of Local Government Studies, Accra on 8

th

November 2018. In all, 20 participants from the three

selected Municipalities and the three estate developers, representatives from Lands Commission,

Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development (MLGRD) and land development

projects beneficiaries attended the stakeholder dissemination workshop.

The stakeholders’ dissemination workshop was used to triangulate the findings. The workshop

had two sections. The first section included a presentation of the findings of the expert

interpretation. The second section included guided focus group discussion.

Profile of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA)

The Greater Accra Metropolitan Area refers to a broad administrative region, which originally

consisted of three MMDAs—Ga, Accra and Tema Districts (Grant 2009). However, due to the

proliferation of MMDAs, this area was fragmented from these three MMDAs in 2003 to 12 in

2012 (Cities Alliance 2017) and further to 22 in 2018 (Figure 6). GAMA in recent years has

undergone significant urban and economic transformation processes. This economic

transformation resulted from the globalization processes as well as deliberate efforts by City

authorities to reposition the city as a global city, or at least as a “world-class city-region” (Grant

2009; Otiso & Owusu 2008; World Bank 2015). The city authorities designed and implemented

the GAMA Strategic Plan. The design and implementation of the strategic plan was ambitious,

yet tangible outcomes are beginning to come to fruition. This is evidenced by improvements in

infrastructure, and significant investments in commercial, industrial, and residential real estate in

mainly the city center (Town and Country Planning Department 2017).

18

Over the years, the city has expanded in physical size. For instance, GAMA population grew

from 1,307,783 in 1991 to 2,513, 025 in 2000 and 4,429,649 in 2014 respectively (Angel et al.

2016). According to Angel et al. (2016), the corresponding growth in urban built-up area was

9,052 hectares in 1991, 29,165 hectares in 2000 and 52,847 hectares in 2014. Thus, during the

period between 1991 and 2000, the built-up area grew by more than three times and almost

double between 2000 and 2014. Therefore, the percentage annual change of total built-up area in

hectares was 4.6% between 2000 and 2014 (Angel et al. 2016). Meanwhile, the Town and

Country Planning Department estimates that the urban area increased approximately by 590km

2

from 447km

2

in 1991 to 1,036km

2

in 2017 representing a 132% increase (Town and Country

Planning Department 2017). The bulk of this increase comes from residential areas and

residential support services.

However, the management of the GAMA has not been coordinated and urban sprawl continues

unabated without limits being set to the physical size of the area. This has resulted in poor urban

connectivity and poorly planned transport infrastructure. According to the Town and Country

Planning Department (2017), an assessment of the implementation of the 1991 GAMA strategic

land use proposal indicates among other things the green belt system and open space areas in

many instances have been overtaken by urban development. The few green belts and open spaces

that are left are threaten by the continuing sprawl of the city. Besides, the Town and Country

Planning Department (2017) also notes that road development proposals contained in the

strategic plan were not implemented.

19

Figure 6: The Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA)

Source: Ghanadistricts.com

The inability of the city authority to implement land use proposals and effectively carry out road

development proposals within the GAMA region have resulted in poor local linkages. The result

of this is that, traffic volumes exceed the capacity and design standards of roads. Moreover,

regional connectors within the area lose their functionality in the urban core as local traffic spills

onto the regional connectors. The net effect is that there is bad land use and transport integration

in GAMA. Therefore, the positive relationship mostly associated with transportation

infrastructure and land values uplift cannot be realized in the midst of poor functionality of

current GAMA.

Land use and transport integration theories suggest that, to increase the functionality of the city

in general, individual elements of the city must support each other (Suzuki et al. 2013). Further,

the theories suggest that, on the one hand, land use development must respond to transportation

systems. The transportation system includes road infrastructure, access and visibility. On the

other hand, the transportation system must respond to changing land uses by increasing the

capacity of the system to meet land use requirements. These two must operate in equilibrium to

ensure good functionality of the city. However, current land use developments in GAMA have

outpaced the provision of effective transport systems and infrastructure. In addition, the

monocentric urban structure of GAMA has also contributed to the worsening traffic situation.

This has created a dysfunctional metropolitan area where there is an imbalance between land use

20

and transportation because the road infrastructure has not kept pace with land use changes

resulting in heavy vehicular and human traffic. The combined effects are that it is difficult, if not

impossible to assess the effects of transport infrastructure or the transport system on land values,

as travel time is affected by heavy traffic, which also affects the entire economy.

The government of Ghana attempted to address urban transport system and infrastructure

challenges. In 2007, the government initiated the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) project under the

Ghana Urban Transport Project (GUTP). This project was jointly funded by the World Bank, the

Agence Francaise de Development (AFD), the government of Ghana and the Global

Environment Facility Trust Fund at the cost of $95 million (Appiah 2015). The Ministry of Local

Government and Rural Development, Ministry of Roads and Highways and the Department of

Urban Roads (DUR) are implementing the project. The project originally had five components to

address the objectives—first, the development and operation of a pilot BRT system. Second,

regulation of passenger transport in the participating MMDAs. Third, traffic engineering,

management and safety including the development of an Area-Wide Traffic Signal Control

Systems in Accra and Kumasi. Fourth, institutional development through support to all the

stakeholders in the project, and fifth, integration of urban development and transport planning

(Ghanaian Times 2018). The sixth component was later added on monitory and evaluation and

emergency works (Teko 2017).

However, the BRT infrastructure could not be completed due to the escalation of cost, which

surpassed the initial budget. Thus, the dedicated bus lanes have not been constructed, and