THE REPLACEMENTS a

SEPTEMBER 2020

WHY AND HOW “ACTING” OFFICIALS ARE MAKING SENATE CONFIRMATION OBSOLETE

THE REPLACEMENTS

The Partnership for Public Service is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that works to revitalize the federal

government by inspiring a new generation to serve and by transforming the way government works. The Partnership

teams up with federal agencies and other stakeholders to make our government more eective and ecient. We pursue

this goal by:

• Providing assistance to federal agencies to improve their management and operations, and to strengthen their

leadership capacity.

• Conducting outreach to college campuses and job seekers to promote public service.

• Identifying and celebrating government’s successes so they can be replicated across government.

• Advocating for needed legislative and regulatory reforms to strengthen the civil service.

• Generating research on, and eective responses to, the workforce challenges facing our federal government.

• Enhancing public understanding of the valuable work civil servants perform.

Case Studies in

Congressional Oversight

This report is part of the Partnership for Public Service’s ongoing work to promote and inform regular oversight that ensures our

government is eectively serving the public. Oversight is the means by which Congress, the media and outside stakeholders can

identify what is working in our government, surface problems, find solutions and hold agencies and their leaders accountable. When

done well, oversight fulfills an important and legitimate role in American democracy.

For more information, visit ourpublicservice.org/congressional-oversight

THE REPLACEMENTS 1

The report includes specific recommendations to

address the prevalence of temporary ocials, fix broken

processes and improve accountability:

• The Senate must reassert its constitutional authority

to provide advice and consent on executive branch

nominations.

• Congress should require more transparency around

vacant positions subject to advice and consent.

• The Senate should reduce the number of presiden-

tial appointments subject to Senate confirmation

and should revisit the “privileged nominations”

process.

• The executive and legislative branches should invest

the time, resources and processes necessary to

support the nomination and confirmation of well-

qualified nominees.

The extensive use of acting ocials and the ease with

which a president can sidestep the confirmation process

should serve as a wake-up call to senators of both parties.

For the government to be fully accountable to the people

it serves, the laws and processes that guide the use and

disclosure of temporary and acting ocials need to be

reconsidered.

The Constitution vests responsibility for filling federal

leadership positions in both the president and the Senate

— the president nominates ocials for key posts, and the

Senate provides “advice and consent.” But in recent years,

presidents have found it increasingly easy to sidestep this

process altogether and to install temporary, “acting” of-

ficials in place of Senate-confirmed leaders.

All presidents have used acting ocials on a tem-

porary basis to fill some of the more than 1200 posi-

tions subject to Senate confirmation, but the executive’s

use of acting ocials has increased in recent years. The

Trump administration has utilized more acting ocials

than other recent presidents and found numerous ways

around the Federal Vacancies Reform Act and other laws

intended to constrain the use of temporary appointees.

Ambiguities in the laws governing the use of acting o-

cials, processes based on norms rather than rules, lack of

transparency into personnel decisions and political pit-

falls risk making the Senate irrelevant in filling positions

across government.

This report examines the prevalence of vacancies

and temporary ocials in Senate-confirmed positions,

the use of acting ocials and the reasons the nomination

and confirmation process has broken down. Through five

case studies of positions that have recently been without

Senate-confirmed ocials, the report oers key insights:

• There is little downside or consequence for an

administration to sidestep the Senate with a tempo-

rary appointment.

• The laws governing the use of temporary ocials are

ambiguous and hard to enforce.

• Some vacancies are intended to reflect an adminis-

tration’s policies.

• The Senate often contributes to, or even causes,

vacancies in key positions in order to achieve politi-

cal objectives.

• Some agencies operate eectively with career leaders

in lieu of political appointees.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

2 PARTNERSHIP FOR PUBLIC SERVICE

INTRODUCTION

the law and competing statutes enable presidents to find

alternative and sometimes creative methods.

Even identifying who is acting in the role of a Sen-

ate-confirmed appointee can be dicult. While some

people are given the ocial title of “acting,” others are

declared to be “performing the duties of” or given some

other moniker. The reasons for the various titles are not

always clear, but a change in terminology often signals an

individual is continuing to perform an acting role after

the time limits of the vacancies act have expired, thereby

circumventing specific provisions in the law that define

who may serve as an acting leader and for how long. (For

the purposes of this report, all temporary ocials are re-

ferred to as acting ocials even when some of them have

varying titles.)

A recent finding by the Government Accountability

Oce has challenged the Trump administration’s applica-

tion of current law in designating acting leaders and con-

cluded that the appointments of Chad Wolf, acting sec-

retary of the Department of Homeland Security, and Ken

Cuccinelli, his acting deputy, did not follow the process as

defined in the Homeland Security Act of 2002, which es-

tablishes the DHS line of succession.

5

Although the impact

of GAO’s finding on the current and future administrations

is unclear, it may have caught the attention of the presi-

dent. On Aug. 25, 2020, Trump announced via Twitter that

he would nominate Wolf to be the secretary of DHS.

While many acting and unconfirmed leaders are ex-

perienced and capable, their temporary nature can limit

long-term planning and erode employee morale. For

some agencies, the lack of a Senate-confirmed person in

a leadership role may have little negative impact on the

day-to-day operations. Yet extended management by

those who are not Senate-confirmed can decrease trans-

parency in how decisions are made.

Some critics charge that presidents also use tempo-

rary ocials to circumvent the Senate’s advice-and-con-

sent role and appoint individuals who might not other-

wise be confirmed.

5 Randolph Walerius and Tanvi Misra, “GAO says Wolf, Cuccinelli

appointments at HS invalid,” Roll Call, Aug. 14, 2020. Retrieved from

https://bit.ly/3kSI1u5

One of the most important tasks for any president is to fill

more than 1,200 politically appointed government posi-

tions needing Senate confirmation. Presidents use tem-

porary ocials — often referred to as “acting” ocials

— on an interim basis pending the selection, nomination

and confirmation of a Senate-confirmed appointee. This

reliance on acting ocials has become more prevalent in

recent years, and in some positions, an acting ocial is

now the norm rather than the exception.

President Donald Trump has expressed a pref-

erence for temporary appointees because of the per-

ceived flexibility to move or reassign them, a perspec-

tive not expressed by his predecessors.

1

Even Trump’s

third White House chief of sta, Mick Mulvaney —

though not in a Senate-confirmed position — carried

the “acting” qualifier for his entire 15-month tenure.

Presidential preference, however, is far from the only

reason many key federal positions remain vacant or are

filled by a temporary ocial. The Senate’s confirmation

process is challenging and takes twice as long today as

it did during President Ronald Reagan’s administration.

2

Increased partisanship and a dicult vetting process are

also contributing factors. Some positions are left vacant

for policy reasons while others have been a challenge to

fill for multiple presidents.

So how do presidents fill positions in the absence of

Senate-confirmed appointees?

Since the first term of President George Washington,

Congress has given the president limited authority to

appoint acting ocials to perform the duties temporar-

ily — without Senate approval — of a vacant oce that is

required to be filled with the advice and consent of the

Senate.

3

The most recent iteration of the law, the Federal

Vacancies Reform Act of 1998,

4

spells out the procedures

used to appoint acting ocials, although ambiguities in

1 Amanda Becker, “Trump says acting Cabinet members give him ‘more

flexibility,’” Reuters, Jan. 6, 2019. Retrieved from https://reut.rs/2VyaoAY

2 Partnership for Public Service, “Senate Confirmation Process Slows

to a Crawl,” January 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3b2vEFS

3 For a history of laws governing vacancies, see the Supreme Court’s

decision in NLRB v. SW General, Inc., 137 S. Ct. 929, 2017.

4 Pub. L. No. 105 -277, Div. C, tit. 1, §151, 112 Stat. 2681-611-16, codified

at 5 U.S.C.§3345-3349d.

THE REPLACEMENTS 3

WHY VACANCIES

MATTER

Acting ocials — even if they are seasoned and

highly regarded individuals — often lack the

perceived authority that accompanies Senate

confirmation.

Many acting ocials do not feel like it is their place

to make long-term policy or operational and manage-

ment decisions that will bind their successors.

Thad Allen, former commandant of the Coast Guard,

said, “People who are in an acting capacity feel they do

not have the power to make long-term changes and do

what they need to do.”

7

In some ways, acting ocials are like substitute

teachers — they may be skilled professionals who have

much to oer the students, but they are not perceived

by those around them as having the full authority of the

teacher, and they do not view themselves as having the

right to make decisions with long-term impact.

“To eectively lead an agency, you need as much

authority and gravitas as you can muster,” Robert Bon-

ner told The Wall Street Journal.

8

Bonner, who was con-

firmed by the Senate to lead both the Drug Enforcement

Administration and the U.S. Customs and Border Protec-

tion agency, added, “If you’re not a confirmed head of an

agency … you’re not going to be able to command as much

respect and attention from your own people and from

other agencies whose cooperation is important.”

Observers have posited the Trump administration,

frustrated by historic and unremitting delays in the Sen-

ate’s consideration of its nominees, has pursued a strat-

egy of relying on acting ocials. Ken Cuccinelli, who has

served in multiple senior positions under Trump, told Fox

News, “The Trump administration has been somewhat

frustrated with how long it takes to get people through

the Senate … So they’ve had to use … these alternatives

that are legal, they’re just less preferential to getting a full

Senate appointment.”

9

7 Partnership for Public Service, “Government Disservice: Over-

coming Washington Dysfunction to Improve Congressional Stew-

ardship of the Executive Branch,” September 2015. Retrieved from

https://bit.ly/2ypo1vS

8 Byron Tau, “Half of 10 Biggest Federal Law Agencies Lack Perma-

nent Chiefs,” The Wall Street Journal, May 16, 2019. Retrieved from

https://on.wsj.com/2Wwzkua

9 “Ken Cuccinelli reacts to judge ruling he was unlawfully appointed

In June 2020, for example, Trump nominated re-

tired general ocer Anthony Tata to serve as the under-

secretary of defense for policy. Tata was a controversial

nominee due in part to findings of misconduct while in

uniform and for controversial public comments he made

after his service. When it was clear by August that Tata’s

nomination would not be approved by the Senate Armed

Services Committee due to concerns on both sides of the

aisle, the White House withdrew his nomination and

designated him as “the ocial performing the duties of

the deputy undersecretary of defense for policy.” That

role eectively made him the first assistant to Acting Un-

dersecretary of Defense for Policy James Anderson and

thus eligible to replace Anderson if the administration so

chooses. The move drew furious criticism from Senate

Democrats, including the senior Democrat on the Armed

Services Committee, Sen. Jack Reed, D-R.I., who called

it, “a flagrant end run around the confirmation process.”

6

This report oers insights into the use of temporary

ocials, the consequences and the need for reform. In

addition to quantifying the extent of their use, the report

includes five case studies that illustrate unique and com-

plex circumstances that surround specific positions. The

report concludes by oering recommendations to clarify

the rules governing acting ocials, reduce the frequency

of temporary leaders and promote a government that is

well-served by committed appointees working on behalf

of the American people.

6 Aaron Mehta, “Controversial nominee Tata appointed to a top de-

fense job, bypassing Congress,” Defense News, Aug. 2, 2020. Retrieved

from https://bit.ly/32wG6mq

4 PARTNERSHIP FOR PUBLIC SERVICE

Members of Congress from both parties have de-

cried the lack of Senate-confirmed appointees and re-

sulting reliance on temporary ocials. “It’s a lot. It’s way

too many,” said Sen. James Lankford, R-Okla., about the

number of acting ocials in Cabinet agencies in 2019.

10

“You want to have confirmed individuals there because

they have a lot more authority to be able to make deci-

sions and implement policy when you have a confirmed

person in that spot.” Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn.,

speaking on the Senate floor, said, “The American people

deserve qualified nominees, and it is our job to ensure we

take the time and care necessary to confirm people who

will serve their country with distinction.”

11

“Make no mistake — the ongoing vacancies and lack

of steady leadership have consequences, especially at a

time like this,” stated Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss.,

this past March.

12

“For example, since 9/11, the federal

government has invested heavily in developing doctrine

to define roles and responsibilities for incident response.

But no one in the administration seems to be familiar

with them. As Americans face a potential coronavirus

pandemic, the administration appears to be caught flat-

footed, scrambling to figure out who is in charge.”

But the political parties diverge on the reason for the

slow pace of confirmations. Lankford successfully cham-

pioned a change to reduce the hours of debate required

for most nominations, limiting the ability of senators

to slow the confirmation of nominees.

13

Klobuchar and

other Senate Democrats opposed the change; Klobuchar

said it would “remove important checks and balances” at

a time when “we also know that we are getting a slew of

unqualified nominees.”

14

Nominations continue to be a

partisan flashpoint, leaving acting ocials in charge for

extended periods despite the changes intended to ad-

vance nominees through the process more quickly.

to lead U.S. immigration agency,” Fox News, March 2, 2020. Retrieved

from https://bit.ly/3d5Q6Xa

10 Juliet Eilperin, Josh Dawsey and Seung Min Kim, “‘It’s way too

many’: As vacancies pile up in Trump administration, senators grow

concerned,” The Washington Post, Feb. 4, 2019. Retrieved from https://

wapo.st/2Ztytgu

11 Sen. Amy Klobuchar, “On the Senate Floor, Klobuchar Fights to En-

sure Nominees to Federal Bench and Executive Branch Are Fully Vet-

ted,” April 2, 2019. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3g8s2p4

12 “Statement of Rep. Bennie Thompson.” Hearing on “A Review of

the Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Request for the Department of Homeland

Security,” House Committee on Homeland Security, March 3, 2020. Re-

trieved from https://bit.ly/3gzyqFV

13 Sen. James Lankford, “Senator Lankford Discusses His Nomina-

tions Rules Change Proposal on Senate Floor,” April 2, 2019. Retrieved

from https://bit.ly/3g4lzvj

14 Sen. Amy Klobuchar, “On the Senate Floor, Klobuchar Fights to En-

sure Nominees to Federal Bench and Executive Branch Are Fully Vet-

ted,” April 2, 2019. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3g8s2p4

Many acting ocials are asked to perform multiple

jobs at the same time, dividing their attention and

increasing their responsibilities.

Leadership positions are demanding jobs that require a

great amount of time and attention. Yet when a person

is given the responsibilities of multiple positions, it be-

comes more dicult to eectively perform the full duties

of each role. This “dual-hatting” has occurred numerous

times in recent years. For example, in June 2019, Gail En-

nis was appointed to serve temporarily as the inspector

general for the Department of the Interior while serving

simultaneously as the inspector general for the Social

Security Administration.

15

This meant that for about two

months, Ennis was the inspector general for two agen-

cies at the same time. Margaret Weichert, already the

deputy director for management at the Oce of Manage-

ment and Budget, was simultaneously dual-hatted as the

acting director of the Oce of Personnel Management, a

role she filled from October 2018 until September 2019.

16

In a few instances, ocials have performed three

jobs simultaneously. William Todd was named acting un-

dersecretary for management at the Department of State

in February 2018. For about a year, Todd also served as

acting director general of the foreign service/director of

human resources in addition to maintaining his ocial

position of deputy undersecretary for management.

17

The use of temporary ocials can complicate and

even invite legal challenges to government action.

When a person or group sues the federal government, the

fact that an acting ocial was involved in the decision

can be used as a legal objection. For example, in Novem-

ber 2018, the state of Maryland questioned the method

by which Matthew Whitaker was appointed acting attor-

ney general.

18

A month later, the issue was raised again

as Whitaker contemplated a rule change to ban the use

of bump stocks in semiautomatic rifles. Senior Justice

Department lawyers advised Whitaker against signing

such a change because a legal challenge to how he was

appointed might be used in court.

19

In fact, at least five

federal lawsuits were filed and a central argument to

15 Miranda Green, “Trump appoints Social Security Administration

watchdog to also oversee Interior,” The Hill, June 10, 2019. Retrieved

from https://bit.ly/32kSrf7

16 Tajha Chappellet-Lanier, “Dale Cabaniss confirmed as OPM direc-

tor,” fedscoop, Sept. 11, 2019. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/30OUzJD

17 U.S. Department of State, “William E. Todd.” Retrieved June 25,

2020, from https://bit.ly/3dpI4sF

18 Ann E. Marimow, “Maryland challenges legality of Whitaker’s ap-

pointment as acting U.S. attorney general,” The Washington Post, Nov.

13, 2018. Retrieved from https://wapo.st/3acUofr

19 Devlin Barrett, “Senior Justice Dept. ocials told Whitaker sign-

ing gun regulation might prompt successful challenge to his ap-

pointment,” The Washington Post, Dec. 21, 2018. Retrieved from

https://wapo.st/2E4XhDn

THE REPLACEMENTS 5

several cases involved objections to Whitaker’s status.

20

Although the legal challenges were eventually dismissed,

the fact that such a rule change was made by an ocial

who was not confirmed by the Senate provided addi-

tional obstacles for the government to defend its actions.

In another instance of legal uncertainty, the Oce of

Personnel Management’s inspector general found in 2016

Beth Cobert could no longer serve as OPM acting direc-

tor after she was formally nominated for the same posi-

tion, and thus her decisions since the date of her nomi-

nation were void. The inspector general disagreed with

the Justice Department’s view that her acting status was

permissible under the vacancies act.

21

Similarly, the Government Accountability Oce de-

cision in August 2020 that the Trump administration im-

properly appointed two top ocials at the Department

of Homeland Security might contribute to future legal

challenges. Immigrant advocacy groups have challenged

the White House’s policies by arguing the ocials who

20 Nick Penzenstadler, “Judge says ban on rapid-fire ‘bump stocks’ can

go forward, rejects challenge to new rules,” USA Today, Feb. 26, 2019.

Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2ZKsGmL

21 Eric Yoder and Joe Davidson, “OPM director nominee can’t serve as

acting agency head, inspector general says,” The Washington Post, Feb.

17, 2016. Retrieved from https://wapo.st/2DD8Pxd

implemented such initiatives lacked proper legal author-

ity to do so.

22

The GAO ruling will likely lead to more liti-

gation on the subject.

The use of temporary ocials in ways that are not

clearly explained in the vacancies law can create a set

of legal complications and complicate the government’s

defense against lawsuits. “The Senate confirmation pro-

cess puts that issue to rest,” said Bob Rizzi, a lawyer who

has guided political appointees through the confirmation

process. Having a permanent ocial “blesses the legiti-

macy of the person in that oce.”

22 Erica Werner and Nick Miro, “Top DHS ocials Wolf and Cucci-

nelli are not legally eligible to serve in their current roles, GAO finds,” The

Washington Post, Aug. 14, 2020. Retrieved from https://wapo.st/314etBZ

LAWS GOVERNING THE USE OF ACTING OFFICIALS: THE FEDERAL VACANCIES REFORM ACT

The Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998 updated the law specifying how a government employee may temporarily perform the du-

ties of a vacant position in an executive agency that is subject to Senate confirmation.

23

While the legislative history acknowledges that

some positions are subject to separate statutes regarding succession, the act is intended to provide the general framework for the vast

majority of Senate-confirmed positions and creates a time limit for service of acting ocials.

24

The cap is generally 210 days, although

it increases to 300 days for vacancies at the beginning of a president’s first term. The time limits are paused while a nomination for the

position is pending in the Senate. The legislation was intended to encourage administrations to nominate qualified people in a timely

manner without undermining the Senate’s advice-and-consent role.

The law provides for three classes of people who may carry out the duties of the oce without Senate confirmation: the first assistant

to the vacant position, an ocial in any other Senate-confirmed position or a senior ocer within that agency.

Once the time limit for a temporary ocial is reached, the law states the position is vacated and the duties vested in that position are

delegated to the head of the agency. However, the law is not specific on who performs the duties of the agency head when that position

is vacant and the act’s time limit on an acting ocial is reached.

The law is intended to give presidents considerable flexibility in filling vacant positions. Yet, the gray areas of the law and diculties

enforcing time limits have given presidents considerable latitude in filling positions.

23 Partnership for Public Service, “The Vacancies Act: Frequently Asked Questions,” Nov. 1, 2017. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3bJyocY

24 “Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998,” 5 U.S.C. § 3345 et seq.

6 PARTNERSHIP FOR PUBLIC SERVICE

THE PREVALENCE OF VACANCIES IN

SENATE-CONFIRMED POSITIONS AND

THE APPROACHES TO FILLING THEM

of Senate-confirmed appointees. Filling open positions,

particularly those requiring congressional approval, is a

multistep process that has been governed by norms, re-

quirements and laws.

The prevalence of temporary ocials in the Trump

administration goes beyond the Cabinet and exists

throughout the executive branch. As of Aug. 17, 2020,

only 70% of 757 key Senate-confirmed positions tracked

by the Partnership for Public Service and The Washing-

ton Post were filled with confirmed ocials. The remain-

ing 30% were either vacant or filled by an acting ocial.

27

Vacancies have been evident throughout many key

departments. As of Aug. 17, eight of the 15 Cabinet-level

agencies were without Senate-confirmed appointees for

27 Current data is available at the database maintained by the Part-

nership for Public Service and The Washington Post located at

https://wapo.st/3fygtr6

From the earliest days of the republic, presidents have

used acting ocials to fill important federal positions and

vacancies. In the two terms of the most recent presidents,

Barack Obama had 14 acting ocials serve as Cabinet sec-

retaries while George W. Bush had 13 and Bill Clinton 11.

25

Trump has used many more acting ocials. In his

Cabinet, Trump had more acting ocials in his first three

years (27) than each of the previous five presidents had

during their entire presidencies.

26

The preceding five ad-

ministrations used an average of about seven acting Cabi-

net ocials per four-year term.

Like previous administrations, Trump has used many

dierent methods to fill vacancies and even challenged

well-established assumptions around the importance

25 This number excludes acting ocials who served fewer than 10

days; Anne Joseph O’Connell, “Actings,” Columbia Law Review 120(3),

April 2020, 613–728. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2YEMw2L

26 Ibid.

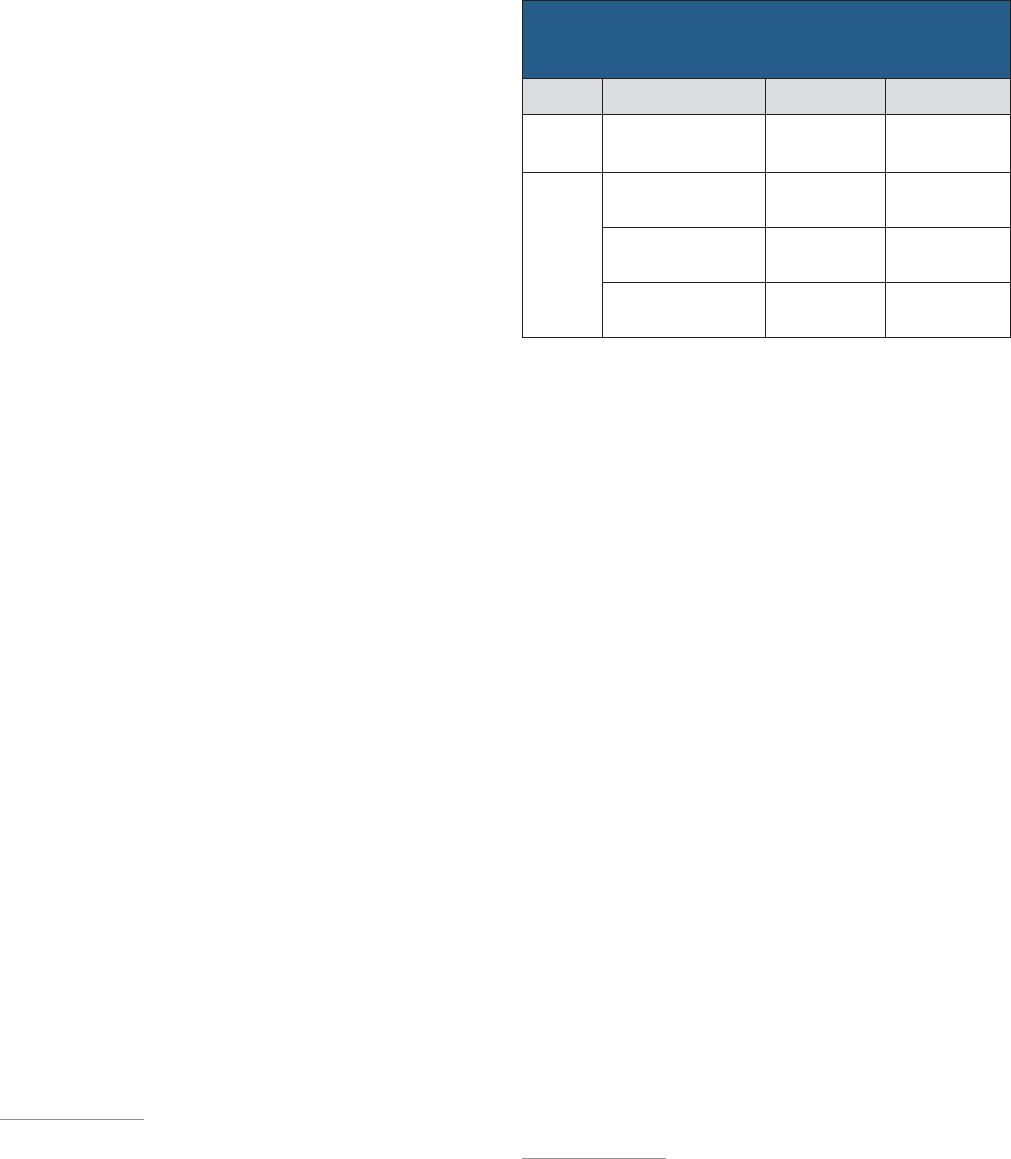

Number of Senate-confirmed positions without a confirmed appointee in

Cabinet-level departments as of Aug. 17, 2020

Number of

Senate-confirmed

positions

Currently vacant

positions

Continuously vacant

positions under

Trump

No. % No. %

Agriculture 13 4 31% 1 8%

Commerce 21 9 43 1 5

Defense 59 21 36 0 N/A

Education 16 7 44 2 13

Energy 23 3 13 0 N/A

Health and Human Services 18 3 17 3 17

Homeland Security 17 11 65 2 12

Housing and Urban Development 13 2 15 1 8

Interior 18 5 28 2 11

Justice* 29 16 55 9 31

Labor 14 4 29 2 14

State** 59 24 41 7 12

Transportation 22 10 45 3 14

Treasury 26 9 35 5 19

Veterans Aairs 12 3 25 1 8

*Does not include United States attorneys and United States marshals **Does not include ambassadors

Note: Data includes full-time, civilian positions that are Senate-confirmed.

Source: The Partnership for Public Service and The Washington Post

THE REPLACEMENTS 7

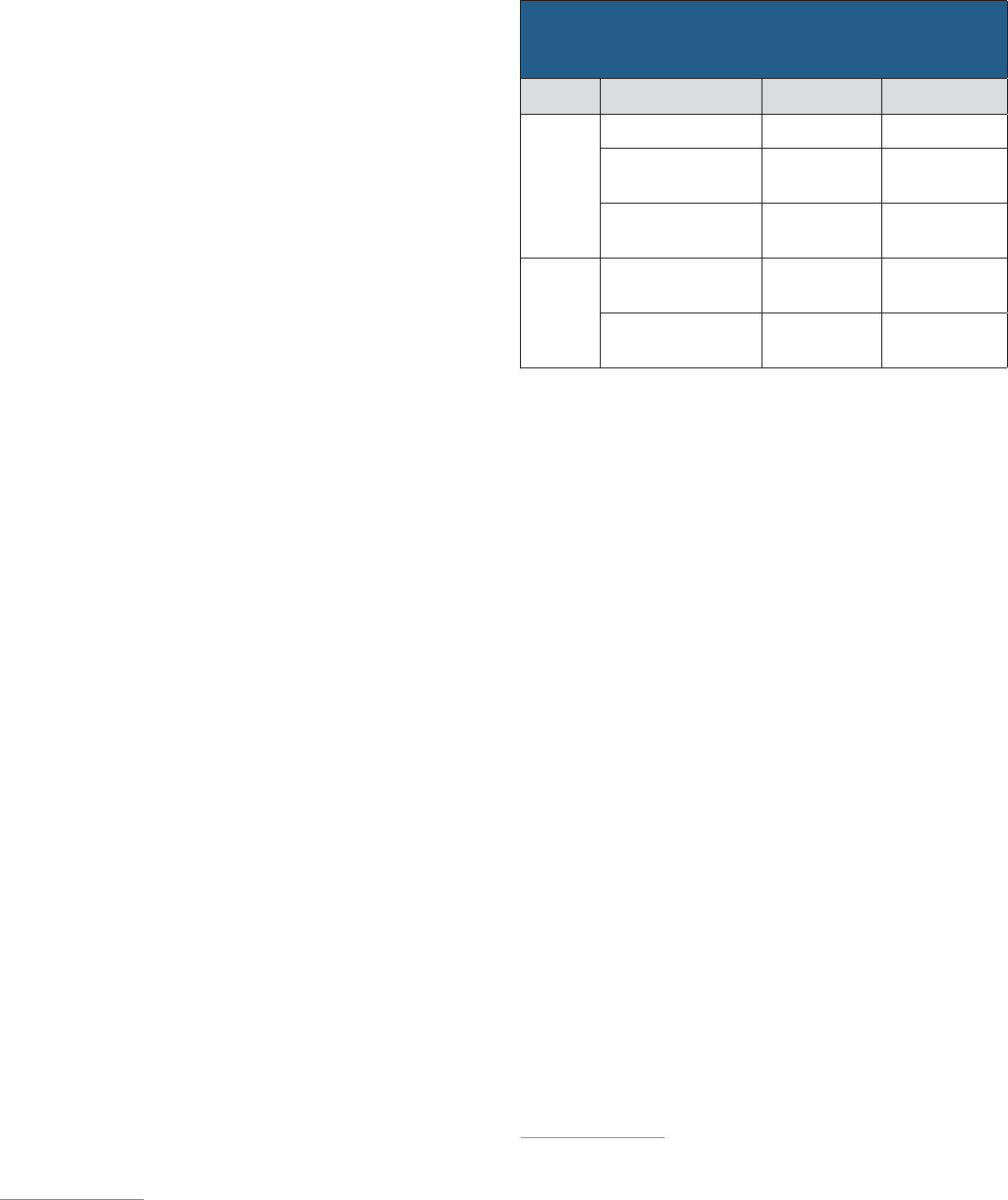

Positions without a Senate-confirmed appointee since the beginning of the Trump administration

in the Departments of Justice, Interior and State

Jan. 20, 2017–Aug. 17, 2020

Vacant Position

Name of Ocial Performing

Duties

Title Given

Department of Justice

Assistant Attorney General for the Justice Programs

Division

Katharine Sullivan

Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney

General of the Oce of Justice Programs

Assistant Attorney General for the Tax Division Richard E. Zuckerman Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General

Administrator, Drug Enforcement Administration* Timothy Shea Acting Administrator

Deputy Administrator, Drug Enforcement

Administration

Preston L. Grubbs Principal Deputy Administrator

Chairman, Foreign Claims Settlement Commission Vacant

Chairman, U.S. Parole Commission Patricia K. Cushwa Vice Chairman and Acting Chairman

Special Counsel for Immigration-Related Unfair

Employment Practices*

Vacant

Director, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and

Explosives

Regina Lombardo Acting Deputy Director

Director, Community Relations Service Gerri Ratli Deputy Director

Director, Oce on Violence Against Women Laura L. Rogers

Acting Director of the U.S. Department of

Justice’s Oce on Violence Against Women

Department of the Interior

Director, Bureau of Land Management William Perry Pendley

Deputy Director, Policy and Programs,

Bureau of Land Management, Exercising

Authority of the Director

Director, National Park Service David Vela**

Deputy Director, Exercising the Authority

of Director for the National Park Service

Special Trustee for American Indians Jerold Gidner

Acting Special Trustee and Principal

Deputy Special Trustee

Department of State

Chief Financial Ocer Vacant

Undersecretary for Civilian Security, Democracy

and Human Rights

Nathan A. Sales

Acting Undersecretary for Civilian

Security, Democracy and Human Rights

Assistant Secretary for Oceans and International,

Environmental and Scientific Aairs

Jonathan Moore Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary

Assistant Secretary for Population, Refugees and

Migration

Carol Thompson O’Connell Acting Assistant Secretary

Assistant Secretary for South Asian Aairs Dean Thompson Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary

Coordinator for Threat Reduction Programs Ryan Taugher Acting Oce Director

Representative of the United States to the

Association of Southeast Asian Nations

Melissa A. Brown Chargé d’Aaires ad interim

Representative of the United States to the

Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development

Andrew Haviland

Chargé d’Aaires ad interim and Acting

Permanent Representative

Special Envoy for North Korea Human Rights Issues Vacant

Alternate Representative of the United States of

America for Special Political Aairs in the United

Nations, with the Rank of Ambassador

Vacant

* Position is exempted from the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998. ** Vela announced he will retire in September 2020. He will be replaced by

Margaret Everson, principal deputy director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

28

Note: Several of the vacant positions have nominations pending in the Senate as of August 2020.

28 Benjamin J. Hulac, “Park Service head retires; successor quickly named,” Roll Call, Aug. 7, 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2DNUjmn

Source: Partnership for Public Service

Source: Partnership for Public Service

8 PARTNERSHIP FOR PUBLIC SERVICE

more than a third of their top positions. Almost two-

thirds (65%) of the key positions in the Department of

Homeland Security were either vacant or filled with an

acting ocial, as were slightly more than half of the top

29 positions at the Department of Justice, 44% at the

Department of Education and 45% at the Department of

Transportation.

When a Senate-confirmed position is vacant, who

fills in? The answer is that there is no single method for

how these leadership positions are filled. Instead, the ad-

ministration has used a complex array of temporary titles

and assumed authority with limited opportunity for pub-

lic scrutiny.

To demonstrate the various methods used to fill posi-

tions, the table above shows examples of the wide array

of titles from three of the largest agencies — departments

of Interior, State and Justice. The table includes positions

that have not had a confirmed ocial for more than three

and a half years — from Trump’s inauguration, Jan. 20,

2017, through Aug. 17, 2020.

For some of these positions, simply identifying the

individuals performing the duties is a challenge. Agency

websites show a collection of acting ocials, principal

deputies, acting assistant secretaries and those “exercis-

ing authority of the director.” In short, there is no uniform

set of titles either within or across the three departments.

In some instances, the Trump administration has

temporarily filled a position by clearly labeling an individ-

ual as the acting ocial. For example, at the Department

of Justice, Regina Lombardo, a longtime law enforcement

ocial at the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and

Explosives, has been serving as acting director since Oc-

tober 2019, while the administration has nominated an-

other person to become the permanent director.

29

By contrast, no one has been appointed to be the act-

ing director of the Community Relations Service within

DOJ. The top ocial there is Gerri Ratli, the deputy di-

rector since January 2017.

30

The agency website refers to

Ratli as the deputy director and does not have an easily

identifiable page associated with the director position.

The oce has become a subject of controversy during the

current focus on civil rights and community policing. The

Trump administration proposed eliminating the agency

and shifting its responsibilities to the Civil Rights Divi-

sion in each of its budget requests to Congress.

31

Support-

ers claim the CRS is meant to address the very conflicts

29 Alex Leary, “Trump to Name President of National Police Ocers

Group to Lead ATF,” The Wall Street Journal, May 24, 2019. Retrieved

from https://on.wsj.com/2Oo3njU

30 The United States Department of Justice, “Meet the Deputy Direc-

tor.” Retrieved Aug. 28, 2020, from https://bit.ly/2Wx5tBR

31 Gabriel T. Rubin, “Democrats Push to Block Trump-Requested

Cuts to Community Policing Programs,” The Wall Street Journal, June

5, 2020. Retrieved from https://on.wsj.com/3eu5zBQ

and issues of racism aecting communities around the

country.

32

At the Department of the Interior, the responsibili-

ties of the director of the Bureau of Land Management

have been fulfilled since July 2019 by William Perry

Pendley, the deputy director of policy and programs. But

Pendley does not have the ocial title of acting director.

Instead, the bureau’s website lists Pendley as the deputy

director “exercising the authority of the director.”

33

Press

reports sometimes incorrectly refer to Pendley as the act-

ing director even though that is not his ocial title.

34

At the Department of State, some top ocials are

listed with yet other titles. For instance, there is no con-

firmed appointee for the assistant secretary for South

Asian aairs. The Department of State’s website does not

include a clear reference to that position, but instead lists

Dean Thompson as the top ocial with the title of princi-

pal deputy assistant secretary.

35

As for ambassadorial va-

cancies abroad, the vacancies law does not apply, accord-

ing to former Undersecretary of State for Management

Patrick Kennedy. Someone does not become the “acting

ambassador”; one becomes the “chargé d’aaires” in ac-

cordance with international diplomatic practice.

The multitude of approaches makes it dicult for

Congress, citizens and other interested parties to hold

temporary leaders accountable, let alone contact them for

critical information or assistance. In order to dig deeper

into how the Trump administration has filled high-level

vacancies in the absence of Senate-confirmed leaders,

the following section provides five examples, highlights

the particular circumstances that have contributed to

each situation and shows how the vacancy law has been

applied or in some cases circumvented.

32 A.C. Thompson and Robert Faturechi, “How a Key Federal Civil

Rights Agency Was Sidelined as Historic Protests Erupted,” ProPublica,

July 9, 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2Wmdo5r

33 Bureau of Land Management, “Leadership.” Retrieved May 27,

2020, from https://on.doi.gov/2AhmvMU

34 Associated Press, “Bureau of Land Management director to contin-

ue through April,” April 6, 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3cb8wFo

35 U.S. Department of State, “Bureau of South and Central Asian Af-

fairs.” Retrieved Aug. 26, 2020, from https://bit.ly/3ek6zb7

THE REPLACEMENTS 9

INSIGHTS AND CASE STUDIES

Background

The job of director had been held by Jonathan Jarvis for

seven years until the end of Obama’s term. Michael T.

Reynolds, a 34-year veteran of the park service,

37

exer-

cised the authority of the position for the first year of the

Trump administration, followed by Daniel Smith, who

was named acting director in January 2018. Smith came

out of retirement to accept the role after serving as super-

intendent of Colonial National Historical Park in Virginia

for a decade.

38

While Smith was serving as acting director, the

Trump administration formally nominated veteran park

service employee Vela to become the full-time director.

39

Vela spent 30 years with the agency and four years as

the superintendent of Grand Teton National Park.

40

The

Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources

held a hearing for Vela two months after his September

2018 nomination and reported him favorably to the full

37 National Park Service, “Mike Reynolds Named NPS Regional Direc-

tor of Department of the Interior Lower Colorado Basin, Upper Colora-

do Basin, and Arkansas-Rio Grande-Texas-Gulf Regions,” Oct. 23, 2019.

Retrieved from https://bit.ly/39WohAz

38 Miranda Green, “Acting National Park Service director gets new

role overseeing 2026 Independence Day celebration,” The Hill, Sept.

30, 2019. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3k9qYUg

39 Congress.gov, “PN2477 — Raymond David Vela — Department of

the Interior.” Retrieved Aug. 28, 2020, from https://bit.ly/3fptsvg

40 Jenni Gritters, “Vela to Serve as Acting Director of the NPS, Ef-

fective Immediately,” REI Co-op Journal, Oct. 1, 2019. Retrieved from

https://bit.ly/3dnZJRC

Most recent ocials

National Park Service

Director

Pres. Name Start End

Obama Jonathan Jarvis Oct. 2009 Jan. 2017

Trump Michael T.

Reynolds (acting)

Jan. 2017 Jan. 2018

Daniel Smith

(acting)

Jan. 2018 Sept. 2019

Raymond David

Vela (acting)

Oct. 2019 Sept. 2020

Margaret Everson

(acting)

Sept. 2020

Insight 1: There is little downside for an

administration to designate a temporary

leader in order to sidestep the complicated

Senate confirmation process.

Case study: Director, National Park Service

Why does this position lack a Senate-confirmed

appointee?

The National Park Service has been without a Senate-

confirmed director since the beginning of the Trump

presidency. Instead, the administration has given the du-

ties of the job to multiple people on a temporary basis.

One recent appointee, Raymond David Vela, had been ex-

ercising the authority of the director from October 2019

to September 2020 — much longer than the time allotted

for acting ocials to serve according to the vacancies law.

Vela was nominated in 2018 to become the permanent di-

rector and would have been the first Hispanic American

to hold the position. But Vela never received a vote from

the full Senate. His pending nomination was returned to

the president at the end of the 115th Congress, per Senate

rules. Instead of renominating him, the administration

gave Vela the temporary title and the responsibilities of

the job.

The reasons this position has been filled with tem-

porary ocials appear to be a combination of timing and

priority — not necessarily because of significant opposi-

tion or controversy regarding Vela or other nominees. It

appears to have been easier for the Trump administration

to designate Vela to serve in an acting capacity than to go

through the eort to renominate him — and there is rela-

tively little pressure to alter that situation.

Who was filling this position in the absence of a

Senate-confirmed leader and what was their title?

Following Vela’s retirement in September, Margaret

Everson, the principal deputy director of the U.S. Fish

and Wildlife Service, was given the authority of the di-

rector position.

36

36 Benjamin J. Hulac, “Park Service head retires; successor quickly

named,” Roll Call, Aug. 7, 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2DNUjmn

10 PARTNERSHIP FOR PUBLIC SERVICE

Senate with little opposition.

41

However, Vela’s nomina-

tion never received a Senate vote and was returned to the

president on Jan. 3, 2019 at the end of the 115th Congress.

No public reason was given for why Vela did not receive

a vote, although Senate sta suggested Senate Majority

Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., could not get bipartisan

agreement to include Vela in a package of nominees at the

end of the year.

Vela’s nomination was not resubmitted to the Senate

at the beginning of the new Congress. Although the com-

mittee would likely have moved his nomination forward

again, Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt issued

an order to have Vela exercise the authority of director

to replace Smith on Oct. 1, 2019.

42

Vela was not given

the ocial title of “acting” director even though he was

given the authority of that position. Bernhardt’s order

stated Vela would serve until at least Jan. 3, 2020. Subse-

quent orders extended Vela’s role through at least June

5, 2020.

43

Since then, Vela and other temporary leaders

in the Interior Department had their authority extended

through a series of (legally questionable) reappointments

and succession orders that have been the subject of a law-

suit filed by two environmental groups.

44

Why the lack of a Senate-confirmed ocial matters

Vela stated he believed his title had little impact on his

eectiveness. “For the most part, and as it pertained to

the daily operations of the NPS, I felt I did have the au-

thority to do the job,” he said. However, Vela added that

the agency and its workforce would have benefitted from

a Senate-confirmed ocial at the top. “For the first time

in its history, the Park Service didn’t have a permanent

director … The NPS workforce as well as our partners

and park visitors need to know and have confidence in

the direction the agency will follow in a second century

of service.”

Some advocacy organizations expressed additional

dissatisfaction with the lack of a confirmed director.

Most of those concerns reflected unhappiness with the

process and the disregard for the formal confirmation

41 Rob Hotakainen, “Smith out, Vela in as NPS acting director,” E&E

News, Sept. 27, 2019. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3ceHmhV

42 National Park Service, “Secretary Bernhardt Announces New National

Park Leadership,” Sept. 30, 2019. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2YV72vV

43 The Secretary of the Interior, “Order No. 3345 Amendment No. 30,”

Jan. 2, 2020. Retrieved from https://on.doi.gov/3cbnHiI; The Secretary

of the Interior, “Order No. 3345 Amendment No. 32,” May 5, 2020. Re-

trieved from https://on.doi.gov/3fAgYRA

44 Kelsey Tamborrino and Anthony Adragna, “Trump’s ‘unforced er-

ror’ puts Western Senate Republicans in an election jam,” Politico, July

17, 2020. Retrieved from https://politi.co/2PueKav; Public Employees

for Environmental Responsibility, “Press Release: Lawsuit Seeks Oust-

er of Park Service and BLM Leaders,” May 11, 2020. Retrieved from

https://bit.ly/3kgEEg5

role of the Senate, and not opposition to the individual

serving in the position.

For example, Theresa Pierno, president and CEO

for National Parks Conservation Association, noted her

organization supported Vela’s nomination, but objected

to how he was placed into that role without being renom-

inated. Pierno wrote, “Despite the Trump administration

having every opportunity to formally advance a National

Park Service director nomination, thousands of National

Park Service employees have gone more than two and a

half years without an empowered leader. Park superin-

tendents aren’t getting support to fulfill their steward-

ship responsibilities and the public is shut out of one de-

cision after another.”

45

45 National Parks Conservation Association, “Press Release: Trump

Administration Continues to Ignore Park Service Director Nomina-

tion,” Oct. 1, 2019. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2yBiX7y

THE REPLACEMENTS 11

Insight 2: Statutes governing vacancies are

dicult to enforce.

Case Study: Administrator, Drug Enforcement

Administration

Why does this position lack a Senate-confirmed

appointee?

While the administrator of the Drug Enforcement Admin-

istration requires Senate confirmation, the position has

been filled by an acting ocial for eight of the last 12 years.

In the legislative history of the Federal Vacancies Re-

form Act, the Senate noted that ocials in this position

were subject to other authority.

46

Both the Obama and

Trump administrations agreed, finding that an executive

order by President Richard Nixon creating the agency

superseded the vacancies law.

47

Under Nixon’s order, a

top vacancy can be filled by a Justice Department ocial

chosen by the attorney general for longer than the time

period allowed by the vacancies law. The alternative ap-

pointment scheme, like the vacancies law, gives the Sen-

ate little recourse in forcing a nomination.

Who is filling this position in the absence of a Senate-

confirmed leader, and what is the title?

Timothy Shea was named acting administrator in May

2020.

48

He is the fourth-consecutive acting ocial in that

role and replaced Uttam Dhillon, who was the acting ad-

ministrator for more than two years.

Background

The DEA is part of the Department of Justice and has a $2

billion budget and 5,000 special agents in 68 countries.

49

The agency’s primary role is to enforce laws regarding con-

trolled substances and combat the country’s opioid crisis.

Over the past five years, neither Presidents Obama

nor Trump formally nominated anyone to this posi-

tion. In 2015, Obama replaced confirmed appointee Mi-

chele Marie Leonhart with former U.S. Attorney Charles

46 “Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998,” S. Rep. 105-250, accompa-

nying S. 2176, 105th Congress, 2d Session, 1998.

47 Michael C. Bender, “Trump’s DEA Chief Vetted Candidates and

Then Took the Job Himself, Riling Police Groups,” The Wall Street

Journal, Oct. 25, 2018. Retrieved from https://on.wsj.com/2zgOFXF

48 The Drug Enforcement Administration, “Attorney General Barr an-

nounces Timothy J. Shea as new Acting Administrator of Drug Enforce-

ment Administration,” May 19, 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/37B3lhA

49 The Drug Enforcement Administration, “Stang and Budget.” Re-

trieved May 7, 2020, from https://bit.ly/3du4NnD; The Drug Enforce-

ment Administration, “Foreign Oce Locations.” Retrieved May 7,

2020, from https://bit.ly/2SMI8uR

Rosenberg in an acting capacity. Rosenberg held that po-

sition until resigning in October 2017.

50

Robert Patterson was the department’s principal

deputy administrator and replaced Rosenberg as the act-

ing administrator for nine months beginning in 2017.

51

Patterson served until June 2018 when the Trump admin-

istration named Dhillon as acting administrator. Dhillon

had played a role in vetting other candidates for the job

before accepting the position himself.

52

Shea was named

the acting administrator in May 2020 to replace Dhillon.

Why the lack of a Senate-confirmed ocial matters

The lack of a Senate-confirmed administrator since 2015

has hindered crisis management and long-term plan-

ning for the agency. In a January 2018 letter, 10 Demo-

cratic senators wrote to the president to urge him to fill

positions at DEA, the Oce of National Drug Control

Policy and other agencies essential to combating opioid

abuse.

53

The senators declared, “We appreciate the work

of the civil servants who are serving as the acting heads

of ONDCP and DEA, but acting leaders cannot enact the

50 Devlin Barrett and Matt Zapotosky, “DEA administrator plans

to step down,” The Washington Post, Sept. 26, 2017. Retrieved from

https://wapo.st/2A2JhYt

51 Devlin Barrett, “DEA chief steps down, citing increasing challenges

of temporary role,” The Washington Post, June 18, 2018. Retrieved from

https://wapo.st/2WEtHKx

52 Michael C. Bender, “Trump’s DEA Chief Vetted Candidates and

Then Took the Job Himself, Riling Police Groups,” The Wall Street

Journal, Oct. 25, 2018. Retrieved from https://on.wsj.com/2zgOFXF

53 Sen. Margaret Wood Hassan et al., United States Senate, Jan. 17,

2018. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3g62Ijc

Most recent ocials

Drug Enforcement Administration

Administrator

Pres. Name Start End

Bush/

Obama

Michele Marie

Leonhart (acting)

Nov. 2007 Dec. 2010

Michele Marie

Leonhart

Dec. 2010 May 2015

Obama/

Trump

Chuck Rosenberg

(acting)

May 2015 Oct. 2017

Trump Robert W. Patterson

(acting)

Oct. 2017 June 2018

Uttam Dhillon

(acting)

July 2018 May 2020

Timothy Shea

(acting)

May 2020 Current

12 PARTNERSHIP FOR PUBLIC SERVICE

kind of robust response to the ongoing fentanyl, heroin

and opioid epidemic that the crisis demands.”

Assistant Attorney General for Administration Lee

Lofthus said individuals serving in an acting capacity

“need to keep the trains running, but sometimes are lim-

ited in the ability to make major changes on their own

— not because of any rule precluding them from doing

so, but because they may not have sucient support. A

confirmed appointee usually gives more certainty to the

workforce, and to external contacts such as Congress.”

In a farewell email to sta, Patterson wrote, “The ad-

ministrator of the DEA needs to decide and address pri-

orities for years into the future — something which has

become increasingly challenging in an acting capacity.”

54

54 Devlin Barrett, “DEA chief steps down, citing increasing challenges

of temporary role,” The Washington Post, June 18, 2018. Retrieved from

https://wapo.st/3ceEyBp

THE REPLACEMENTS 13

Insight 3: Administrations choose to leave

some positions unfilled as a reflection of

their policies.

Case study: Special Envoy for North Korean Human

Rights, Department of State

Why does this position lack a Senate-confirmed

appointee?

The special envoy for North Korean human rights posi-

tion has been without a nominee since the beginning of

the Trump administration as a matter of policy.

Who is filling this position in the absence of a Senate-

confirmed leader and what is their title?

This position has not been filled since President Trump

took oce in January 2017, although the responsibilities

were assumed by the undersecretary for civilian security,

democracy and human rights — a position currently filled

in an acting capacity by Nathan A. Sales. Sales also serves

in the Senate-confirmed role of coordinator for counter-

terrorism.

55

Background

In 2004, Congress approved the North Korean Human

Rights Act and established a special envoy position that

would “coordinate and promote eorts to improve re-

spect for the fundamental human rights of the people of

North Korea.”

56

The job was filled almost continuously

until early 2017.

Since then, the post has remained vacant as the cur-

rent administration, the Senate and the State Department

have debated priorities and approach regarding North

Korea.

When the 2004 law expired in mid-2017, Secretary of

State Rex Tillerson proposed a restructuring plan that in-

cluded the removal or reorganization of dozens of special

envoys.

57

Tillerson added the duties of the North Korean

human rights envoy to those of the undersecretary of

state for civilian security, democracy and human rights.

55 U.S. Department of State, “Nathan A. Sales.” Retrieved July 16, 2020,

from https://bit.ly/32uvLri; U.S. Department of State, “Under Secretary

for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights.” Retrieved July 16,

2020, from https://bit.ly/30k7kLV

56 Congress.gov, “H.R.4011 — North Korean Human Rights Act of

2004.” Retrieved Aug. 28, 2020, from https://bit.ly/2SJNZku

57 Josh Rogin, “Tillerson scraps full-time North Korean human

rights envoy,” The Washington Post, Aug. 31, 2017. Retrieved from

https://wapo.st/2SKOPNV

In August 2018, the Trump administration created a

separate new position that does not need Senate confir-

mation called the special representative to North Korea

and appointed Stephen Biegun to the role. In December

2019, Biegun was confirmed to be deputy secretary of

state and continued to be involved with North Korean

issues along with the other duties associated with that

position.

Senators on both sides of the aisle have objected to

the reorganization that left the North Korea envoy po-

sition vacant. Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., told The Wash-

ington Post, “We need a dedicated special envoy focused

specifically on the North Korean government’s system-

atic and horrific human rights abuses against its own

people.”

58

Sen. Ben Cardin, D-Md., said, “We need to em-

power the State Department to expose and seek account-

ability for North Korea’s abusive human rights practices,

and I am concerned this proposal [for reorganization of

the envoy’s responsibilities] would fall far short of that

goal.”

59

Shortly thereafter, Congress and the president re-

authorized the North Korean Human Rights Act, which

required that a special envoy would be confirmed in time

to submit a report to Congress in January 2019.

60

Never-

theless, as of August 2020, the administration had yet to

nominate a special envoy for North Korean human rights

or appoint an acting special envoy.

Why the lack of a Senate-confirmed ocial matters

The impact of not having a Senate-confirmed special en-

voy for North Korean human rights is in the eye of the be-

holder. The Trump administration appears to have made

a policy decision not to fill the position out of concern

such a move might derail diplomatic eorts. However,

58 Ibid.

59 Ibid.

60 Congress.gov, “H.R.2061 — North Korean Human Rights Reauthori-

zation Act of 2017.” Retrieved Aug. 28, 2020, from https://bit.ly/3fDmy

Most recent ocials

Department of State

Special envoy for North Korean human rights

Pres. Name Start End

Obama Robert R. King Nov. 2009 Jan. 2017

Trump Vacant* Jan. 2017 Current

* The responsibilities of the position have been assumed by the

undersecretary of state for civilian security, democracy, and human

rights — a position filled by Nathan A. Sales since Sept. 2017.

14 PARTNERSHIP FOR PUBLIC SERVICE

some experts have called on Trump to appoint an envoy

and place more focus on North Korean human rights vio-

lations.

“[The special envoy on North Korean human rights]

is the central figure for policy and would have direct ac-

cess to the president in carrying out his or her job to ad-

dress the atrocious human rights abuses in North Korea,”

wrote Victor Cha of the George W. Bush Institute.

61

“The

Trump administration should nominate a candidate.”

61 Victor Cha, “Policy Recommendations: North Korean Human

Rights Critical to Denuclearization,” George W. Bush Presidential Cen-

ter, Nov. 26, 2018. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3fx3gip

THE REPLACEMENTS 15

Insight 4: The Senate will tolerate, and

even cause, extended vacancies in

leadership roles to accomplish political

objectives.

Case Study: Undersecretary of State for Management

The undersecretary of state for management plays a key

role in the operations of the State Department. The job

has been filled with a Senate-confirmed ocial since May

2019, but was without one for the previous 28 months.

One of the primary reasons for the lengthy vacancy was

because the nomination of the current undersecretary,

Brian Bulatao, became a bargaining chip in negotiations

between Senate Democrats and the secretary of state re-

garding a separate issue.

Other reasons contributed to the vacancy. The exit

of senior administrative ocials at the State Department

soon after President Trump’s inauguration created a gap

that rarely occurred in previous transitions.

62

In addition,

a failed nominee preceded Bulatao at a time when the job

was vacant, and this added to the length of time without

a Senate-confirmed appointee.

Who was filling this position in the absence of a

Senate-confirmed leader?

Prior to Bulatao’s confirmation in May 2019, the position

did not have a Senate-confirmed ocial for the first two

years of the Trump administration. From January to June

2017, the position was vacant with no one designated to

fill the role. From June 2017 through May 2019, William

E. Todd served as the acting undersecretary.

Background

In 2017, the National Academy of Public Administration

cited the State Department position as one of the tough-

est management jobs to fill.

63

“Department expertise in

security, management, administrative and consular posi-

tions in particular are very dicult to replicate and par-

ticularly dicult to find in the private sector,” noted Da-

vid Wade, the chief of sta to former Secretary of State

John Kerry.

64

62 Barbara Plett Usher, “Top U.S. diplomats leave State Department,”

BBC News, Jan. 27, 2017. Retrieved from https://bbc.in/39W8kdU

63 National Academy of Public Administration, “Prune Book 2017: The

40 Toughest Management Positions in Government.” Retrieved from

https://bit.ly/35I2rP3

64 Josh Rogin, “The State Department’s entire senior administrative

team just resigned,” The Washington Post, Jan. 26, 2017. Retrieved from

https://wapo.st/3ccqVm1

For the first five months of the Trump administra-

tion, no one was assigned the duties of the oce. At that

point, Todd was named the acting undersecretary and

served for almost two years, far surpassing the vacancy

law’s 210-day limitation.

65

Not only was Todd serving

as undersecretary, but for about half of that time he was

filling two additional positions concurrently: acting di-

rector general of the foreign service/director of human

resources, and his ocial position of deputy undersecre-

tary for management.

The process for getting a confirmed ocial took sev-

eral tries. About six months into his presidency, Trump

nominated Eric Ueland for the job. Though he was voted

on favorably by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee,

Ueland never received a full Senate vote and Trump of-

ficially withdrew his nomination in June 2018.

66

Following Ueland’s withdrawal, the administration

nominated Bulatao, the former chief operating ocer

and third ranking ocial at the CIA. Though Bulatao

was well-received by the Senate Foreign Relations Com-

mittee, he faced a nearly yearlong wait due to a power

struggle between senators and the administration. Sen.

Robert Menendez, D-N.J., the ranking member on the

committee, held up dozens of State Department nomi-

nations due to a host of issues, including the administra-

tion’s perceived lack of responsiveness to questions about

interactions with foreign leaders and potential political

retribution against career State employees.

67

After sev-

eral months, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo agreed to

produce documents and Menendez lifted his hold on the

65 U.S. Department of State, “William E. Todd.” Retrieved June 11,

2020, from https://bit.ly/3dpI4sF

66 Congress.gov, “PN1387 — Eric M. Ueland — Department of State.”

Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://bit.ly/2YJaJ8c

67 Rachel Oswald, “Menendez, Pompeo Feud Over Diplomatic Nomi-

nees,” Roll Call, Oct. 16, 2018. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/39uVrXY

Most recent ocials

Department of State

Undersecretary of state for management

Pres. Name Start End

Bush/

Obama

Patrick Kennedy Nov. 2007 Jan. 2017

Trump Vacant Jan. 2017 June 2017

William E. Todd

(acting)

June 2017 May 2019

Brian Bulatao May 2019 Current

16 PARTNERSHIP FOR PUBLIC SERVICE

nomination in May 2019.

68

Bulatao was confirmed shortly

thereafter with a 92-5 senate vote.

69

Why the lack of a Senate-confirmed ocial matters

Former Undersecretary of State Patrick Kennedy, who

held the position under Presidents George W. Bush and

Obama, said the long-term vacancy had a “significant

negative impact across the entire management spec-

trum.” He suspects that a permanent undersecretary

would have kept leadership from maintaining a long

hiring freeze, which he said damaged the department.

A confirmed ocial also would have been able to point

out the eects — like lowered morale and increased wait

times for getting passports — to the secretary, Kennedy

said.

Kennedy added that the undersecretary’s role is es-

pecially crucial now because of constant security threats

to embassies around the world. The undersecretary plays

a central role in consular services for Americans abroad,

such as when American medical volunteers had to be

evacuated during the Ebola crisis in Western Africa and

more recently during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Retired ambassador Ronald Neumann, who currently

heads the American Academy of Diplomacy, considered

the undersecretary of state for management vacancy the

most important of the many State Department vacancies

during the Trump administration.

70

Since taking oce as a Senate-confirmed undersec-

retary, Bulatao initiated a reform strategy focused on tal-

ent management, security infrastructure, technology and

other key work streams. He is also overseeing eorts to

improve employee diversity and equity and inclusion, a

long-standing challenge for the workforce.

68 Nick Wadhams and Daniel Flatley, “Menendez Drops Hold on

Pompeo Friend for State Department Post,” Bloomberg, May 2, 2019.

Retrieved from https://bloom.bg/3cguTKG

69 Congress.gov, “PN111 — Brian J. Bulatao — Department of State.”

Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://bit.ly/3du6D81

70 Charles S. Clark, “State Department Under Pompeo Still Coping

with Vacancies,” Government Executive, Dec. 17, 2018. Retrieved from

https://bit.ly/35ExkUJ

THE REPLACEMENTS 17

Insight 5: Some agencies and bureaus may

operate eectively with a seasoned career

ocial in charge.

Case Study: Assistant Attorney General, Tax Division,

U.S. Department of Justice

Why does this position lack a Senate-confirmed

appointee?

It is unclear why the Justice Department’s assistant at-

torney general in charge of the Tax Division has not had a

Senate-confirmed appointee for nine of the last 11 years.

Former DOJ ocials and outside observers cited a variety

of reasons apart from the rigor of the confirmation pro-

cess, including the diculty of finding qualified lawyers

with tax law expertise, post-employment restrictions and

the eect on one’s career path. Others suggested the Tax

Division does not have a high profile and many of the

most important tax-related investigations are carried out

by other parts of the federal government or local prose-

cutors. Consequently, placing a Senate-confirmed leader

atop the Tax Division may not be a top priority.

Who is filling this position in the absence of a Senate-

confirmed leader, and what is their title?

No one is in the role of assistant attorney general. The Tax

Division website lists Richard Zuckerman, the principal

deputy assistant attorney general, as the top ocial.

71

Background

The Tax Division and its roughly 370 attorneys are

charged with enforcing the nation’s tax laws by support-

ing IRS investigations and representing the U.S. in tax

litigation. In a single year, they process almost 6,700 civil

cases and approximately 625 appeals, and authorize be-

tween 1,300 and 1,800 criminal tax investigations.

72

The top position at the Tax Division is the assistant

attorney general. A temporary ocial in this role is not

a new phenomenon. The position has been filled by an

acting or temporary ocial for nine of the last 11 years

spanning two administrations, including six of Obama’s

eight years.

President Trump did not nominate anyone for the

job during his first three years. On Feb. 12, 2020, Trump

formally nominated Zuckerman, who was the principal

deputy assistant attorney general for the division. Ac-

cording to the Justice Department website, Zuckerman

71 United States Department of Justice, “Tax Division.” Retrieved Aug.

4, 2020, from https://bit.ly/2XtNrlf

72 Tax Division, United States Department of Justice, “FY 2019 Con-

gressional Budget.” Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2SHT64w

is serving as the “head of the Tax Division.”

73

Essentially,

Zuckerman has been formally nominated to do the job he

is currently doing in a temporary capacity. His nomina-

tion was pending as of August 2020

.74

Why the lack of a Senate-confirmed ocial matters

The impact of this vacancy may be limited. Former ocials

suggested that an acting leader of the Tax Division — along

with the career ocials — can accomplish the agency’s

goals even without a Senate confirmation. In fact, surveys

of government employees show that job satisfaction and

engagement for the division have been consistently higher

in recent years than scores for the Justice Department as

a whole and the entire government.

75

Since the division

tends to prosecute mostly low-profile cases, there is little

pressure to nominate a permanent ocial.

Former Deputy Assistant Attorney General of Pol-

icy and Planning of the Tax Division Caroline Ciraolo,

73 The United States Department of Justice, “Deputy Assistant Attor-

ney General.” Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://bit.ly/35JhJmL

74 Congress.gov, “PN1512 — Richard E. Zuckerman — Department of

Justice.” Retrieved Aug. 5, 2020, from https://bit.ly/3icspiY

75 Partnership for Public Service and Boston Consulting Group, “Best

Places to Work in the Federal Government: Tax Division,” 2019. Re-

trieved from https://bit.ly/3gd9aEF

Most recent ocials

U.S. Department of Justice

Assistant attorney general, Tax Division

Pres. Name Start End

Obama Kathryn Keneally April 2012 June 2014

Tamara W. Ashford

(acting)

June 2014 Dec. 2014

Caroline D.

Ciraolo* (acting)

Jan. 2015 Jan. 2017

Trump David Hubbert

(acting)

Jan. 2017 Nov. 2017

Richard Zuckerman

(acting)**

Dec. 2017 Current

*Principal deputy Caroline Ciraolo filled the role in an acting capacity

from Feb. 2015 through July 2016 when her role expired under the

Federal Vacancies Reform Act. From that point, she headed the Tax

Division as principal deputy assistant attorney general.

**Zuckerman has been the head of the Tax Division even though he is

listed on the website as the principal deputy assistant attorney general.

Zuckerman was formally nominated for the assistant attorney general

position in Feb. 2020.

Note: Periods of two months or less when there was no clear

temporary ocial are not listed.

18 PARTNERSHIP FOR PUBLIC SERVICE

who served in an acting capacity under Obama, said that

when she was the acting assistant attorney general, she

was not limited. “Serving in an acting capacity doesn’t

mean you can’t get a tremendous amount of work done,”

Ciraolo told Bloomberg Law.

76

“To the extent there was

any hesitation in the acting role, it was out of respect for

the pending nominee … This did not impede our ability to

operate the division. It was simply in recognition of my

role as acting assistant AG.”

Not everyone agrees. Matt Axelrod, an ocial in the

Obama Justice Department, discussed the broad issue of

acting DOJ ocials with The Washington Post. While

those in acting roles often perform admirably, he said,

“Everyone knows they’re temporary, and that means that

they don’t have the same heft internally or externally as

the Senate-confirmed heads will.”

77

76 Jacob Rund, “Justice’s No. 3 Slot Is Soon to Be Vacant — Once Again,”

Bloomberg Law, May 2, 2019. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3ccxSDT

77 Matt Zapotosky, “The Justice Department lacks key leaders, and a

Republican senator is threatening to keep it that way,” The Washington

Post, Jan. 6, 2018. Retrieved from https://wapo.st/2LxoLBO

THE REPLACEMENTS 19

FACTORS THAT EXPLAIN THE

PREVALENCE OF ACTING OFFICIALS

AND VACANCIES

the nomination of Raymond David Vela to be the director

of the National Park Service, nominations are returned

to the president with no clear reason other than they

did not make the list of top Senate priorities as a session

comes to an end.

In recent months, Senate activity has been further

challenged by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some of the Sen-

ate’s business has been conducted remotely and only a

few hearing rooms — large enough to accommodate so-

cial distancing — are available for committee business

meetings. The Senate is known for being a deliberative

body, but the new issues raised by current health con-

cerns will add to the diculties in managing the Senate

calendar for the foreseeable future.

Even nominees who are uncontroversial, well-qual-

ified and widely supported may endure a long road to

confirmation. Because rules and procedures govern how

and when the Senate considers nominations, the major-

ity leader spends the chamber’s limited time on the po-

sitions that matter most, while nominees for other po-

sitions wait. Coupled with the rigorous, expensive and

time-consuming process of resolving financial conflicts

of interest, submitting to a background investigation and

answering hundreds of policy questions, some talented

people decide that the price of public service is too high.

2. Senate polarization

Political polarization, characterized by ongoing stale-

mates on a wide range of issues, is by many measures the

highest it has been in decades. The average Senate confir-

mation process for presidential appointments took more

than twice as long during Trump’s first three years (115

days) as it did during President Reagan’s time in oce

(56.4 days).

79

One of the major reasons the average confirmation

time has grown is the increased use of Senate filibus-

ters to delay nominations. Cloture votes, the Senate’s

procedural motion used to limit debate and overcome

filibusters, have increased dramatically as a result of the

increased use or threatened use of the filibuster. During

79 Partnership for Public Service, “Senate Confirmation Process Slows

to a Crawl,” January 2020. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/3b2vEFS

It is often dicult to pinpoint specific causes for indi-

vidual positions, but there are several contributing fac-

tors. President Trump’s choices and processes are major

causes, for example, but they are far from the only rea-

sons that so many vacancies and temporary ocials in

politically appointed jobs persist across the government.

The following major factors have contributed to va-

cancies during the Trump administration and, in some

instances, prior administrations.

1. Senate rules

The Senate bears partial responsibility for the large num-

ber of unfilled positions. While the Senate can move

quickly with unanimous consent, the complexity of Sen-

ate rules and procedures can allow even one senator to

slow the pace of nominations even if a nominee faces

minimal opposition. With the COVID-19 pandemic, the

Senate faces further obstacles that have slowed down the

process.

The delay for many nominees is complicated by the

Senate requirement that nominations not confirmed or

rejected at the end of a session, or when the Senate ad-

journs or recesses for more than 30 days, are automati-

cally returned to the president.

78

The president must

resubmit those individuals for nominees to get another

chance for Senate confirmation.

Because of the limited Senate schedule and other

priorities, many nominations are returned to the presi-

dent accordingly, especially at the end of the calendar

year and always at the end of a Congress. At the end of the

115th Congress in January 2019, about 300 civilian nomi-

nations were returned to Trump while about 85 were

returned in January 2020. In some instances, the same

people are renominated the following year. But others are

not resubmitted and lose their chance at confirmation.

In practice, Senate leaders usually agree on certain

priority confirmations as the end of the year approaches.

Yet the Senate does not necessarily have the time or in-

terest to vote on all nominees. In some instances, such as

78 Congressional Research Service, “Senate Consideration of Presi-

dential Nominations: Committee and Floor Procedure,” RL31980, April

11, 2017. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2Q8bxye

20 PARTNERSHIP FOR PUBLIC SERVICE

the first terms of Presidents Clinton, George W. Bush and

Obama combined, there were only about 30 cloture votes