Human

Traicking

Corridors

in Canada

A

B

C

Introduction

5 | Guiding Research

Questions

7 | Terms and Denitions

8 | Types of Human

Tracking in Canada

Summarized Methodology

11 | Research Limitations

How Human Tracking

Corridors Operate

14 | The Economics of Human

Tracking Corridors

14 | Maximizing Prot within

a Competitive Commercial

Sex Market

15

| Minimizing Risks

17

| Types of Sex Tracking

18

| Characteristics of Victims

and Survivors of Sex

Tracking

23

| Characteristics of

Trackers

24

| Who are the Trackers?

25 | How Boyfriend Trackers

Control and Coerce Their

Victims

28 | The Geography of Human

Tracking Corridors and

Circuits

9

13

Exiting Human Tracking

37 | Barriers to Exiting

40 | The “Cycle of Change”

37

Services Needs and Systems

of Intervention

44 | Trauma-informed Programs

45 | Service Provision Challenges

42

Conclusion and

Recommendations

49 | Protection

50 | Prosecution

50 | Partnership

50 | Empowerment

48

Appendices & Endnotes

51 | Appendix A: Glossary of Terms

53 | Appendix B: Full methodology

53 | Literature Review

54 | Media Review

56 | Qualitative Research: Interviews

59 | Endnotes

51

4

Contents

A

In This Section:

4

Introduction

9

Summarized Methodology

Introduction

Introduction

I

n 2005, Canada introduced legislation prohibiting

human tracking, yet trackers continue to reap large

prots by exploiting people for their own gain across Canada.

Between 2009 and 2018, police services across Canada

reported 1,708 incidents of human tracking; however,

these numbers only represent situations of tracking

which received police intervention.

1

Testimonies from

individuals with lived experience and social service providers

suggest that the actual number of victims and survivors is

signicantly higher.

2

Human tracking violates the human rights of victims and survivors, and

one of the ways that trackers operate is by controlling the movements of the

person they are exploiting. This report focuses on the element of movement

and transportation in human tracking by investigating human tracking

corridors in Canada.

Anecdotal evidence from law enforcement, frontline service delivery agencies

and the media have pointed to the existence of human tracking corridors

through which individuals are routinely moved for the purpose of exploitation.

However, it is important to note that human tracking does not necessarily

involve the transportation and movement of persons. Many people in Canada

continue to confuse human tracking with international border smuggling.

In reality, human smuggling and human tracking are very dierent crimes,

and a person may be forced or manipulated into an exploitative situation

without ever leaving their home community.

Movement along human tracking corridors can be a signicant aspect of the

exploitation experienced by survivors. It may impact intervention opportunities

from service providers, law enforcement and members of the public, and the

needs and experiences of survivors when they escape or exit the tracking

situation. Although transportation can be a core aspect of survivors'

exploitation, this is the rst research in Canada that investigates how

tracking corridors operate.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

4

Introduction

Guiding Research Questions

Given that control of movement and transportation are core components

of exploitation for many victims and survivors of human tracking in Canada,

the Canadian Centre to End Human Tracking (The Centre) conducted this

research project to investigate the role of corridors in human tracking, and

the distribution of corridors around the country.

For the purposes of this research, we dened human tracking corridors as

strips of land or transportation routes that include two or more major cities,

that are used by trackers to move individuals between sites of commercial

exploitation. In the context of sex tracking, victims are transported between

commercial sex markets.

3

In addition to connecting multiple population centres,

human tracking corridors may extend across large geographic areas.

Given the lack of pre-existing evidence on this topic, the scope of the research

was exploratory in nature and aimed to establish a baseline of knowledge on

human tracking corridors, as well as opportunities for future research and

advocacy. The primary questions that guided this research were:

What types of public and/or private

spaces are being used throughout

the corridor? (E.g., motels, hotels,

truck stops, schools, social services,

main streets, parks).

Where are human tracking

corridors located in Canada?

What jurisdictions do they

intersect with? (E.g., municipal,

provincial, Indigenous territories,

U.S. and/or other countries).

What types of tracking are

taking place? (E.g., labour or

sex tracking, specic types of

sex and/or labour tracking).

What are some of the key

characteristics of trackers

and those being tracked?

What transportation methods

are being used? (E.g., personal

vehicle, bus, train, plane, hitch-

hiking, rideshare services).

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

5

Introduction

The Canadian Centre to End Human Tracking

The Centre is a national charity dedicated to ending all types of human

tracking in Canada. Our organization focuses on four priority areas:

public education and awareness, research and data collection, convening

and knowledge transfer, and policy development and advocacy. We work

with like-minded stakeholders and organizations, including non-prots,

corporations, governments and survivors/victims of human tracking, to

advance best practices, eliminate duplicate eorts across Canada, and

enable cross-sectoral coordination by providing access to networks and

specialized skills.

We operate the Canadian Human Tracking Hotline, a 24/7, multilingual

access to a safe and condential space to ask for help, connect to

services, and report tips to law enforcement. While The Hotline provides

localized and immediate supports to victims and survivors, it also enables

the compiling of data to help disrupt tracking networks.

Over time, The Hotline’s data will provide an evidence base of human

tracking incidents, geographical locations and types of tracking across

Canada. This data will be critical in the ght to end tracking. At the time

of writing this report, The Hotline had not collected enough data to be

able to present ndings on human tracking corridors.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

6

Introduction

Terms and Denitions

Throughout this report, when referring to individuals who have experienced

human tracking, we use the terms “victim” and “survivor.” The term victim

is used when the act of tracking in persons is ongoing, whereas survivor

describes a person who has escaped or exited the tracking situation, and may

have started a healing process.

4

We recognize that victimization and survivorship

are not mutually exclusive terms or experiences, and that individuals who have

experienced exploitation may prefer one term over another in order to describe

their experiences.

Use of a common denition of human tracking is critical to increasing our

knowledge of how this crime occurs in Canada. To promote consistent data

gathering and analysis, both in this report and in our other initiatives, we rely

on the Canadian Criminal Code which denes human tracking as recruiting,

transporting, transferring, receiving, holding, concealing or harbouring a person,

or exercising control, direction or inuence over the movements of a person,

to facilitate their exploitation.

5

For the purposes of this legislation, a person exploits another person if they

cause them to provide, or oer to provide, a labour or service by engaging in

conduct that could be expected to cause the other person to believe that their

safety, or the safety of a person known to them, would be threatened if they

failed to provide the labour or service.

6

When determining whether exploitation is taking place, Canadian courts

consider whether the accused used or threatened to use force or another

form of coercion, used deception, abused a position of trust, power or

authority, or concealed or withheld travel or identity documents in order

to exploit another person.

The Canadian Criminal Code denition of human tracking is sometimes

referred to as the Action-Relationship-Purpose (ARP) Model. This model

breaks human tracking down into three main components, including action

components such as recruiting or concealing a victim of tracking, relational

components such as exercising control over a victim, and a purpose

of exploitation, which refers to compelling a person to provide a labour

or service. These three components work together to dene the crime

of human tracking in Canada.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

7

Introduction

Action Relationship Purpose Indicators

Key Reporting

Details

Recruits

or

Transports

or

Transfers

or

Receives

or

Holds

or

Conceals

or

Habours.

Control

or

Direction

or

Inuence on the

movements

of a person.

Purpose of

causing them to

provide labour or

service.

Their safety

would be

threatened if they

failed to provide,

the labour or

service.

Use of force,

threats touse

force.

Coercion,

deception, abuse

of a position of

trust, power or

authority.

Withholding travel

documents.

Details of

the victim.

Details of

the location.

Nature of the

business/

suspicious activity.

Details of the

tracking

situation.

Details of who

are involved.

OR

Action-Relationship-Purpose (ARP) Model of Human Tracking

Types of Human Tracking in Canada

Research conducted to date reveals two overarching types of human

tracking in Canada: sex tracking and labour tracking.

7

Drawing on research

conducted in Canada and the United States,

8

the various sectors, business

models, tactics, methods and characteristics involved for each type can be

broken down as follows:

Human tracking typology

Sex tracking

Escort services Domestic work Restaurants &

food services

Illicit massage

Residential

sex tracking

Personal sexual

servitude (includes

survival sex)

Outdoor solicitation Agriculture Health and beauty

services

Pornography Construction Hotels & hospitality

Remote interactive

sexual acts

Landscaping Commercial

cleaning services

Labour tracking

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

8

Introduction

Summarized

Methodology

I

n undertaking this research, we conducted three lines

of inquiry to better understand how human tracking

corridors operate in Canada: a literature review, a media

review, and qualitative research (interviews with service

providers and law enforcement).

See Appendix B for

full methodology.

We reviewed more than 85 articles and reports from academic institutions,

government, and community-based agencies to explore themes related

to human tracking in Canada and North America. We then conducted a

systematic scan of human tracking media coverage in Canada, analyzing

more than 1,800 search results, including 267 unique news articles, to better

understand the following:

To what extent are human tracking corridors understood and reported

on in the mainstream media?

Where have human tracking corridors been identied already?

While research on human tracking in Canada is increasing, the literature

review and media scan did not produce enough meaningful data to come to any

rm conclusions in response to our research questions. To develop a robust

understanding of how and where human tracking corridors operate, we held

69 semi-structured key informant telephone interviews with frontline service

delivery sta and law enforcement ocers, from nine provinces, with direct

experience working with victims and/or survivors of human tracking.

We ensured that a consistent denition of human tracking was used

throughout the interviews (see Terms and Denitions), and in the case of

sex tracking, interview respondents were able to dierentiate between

human tracking and legal sex work.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

9

Introduction

Past research has shown that sex tracking and commercial sex are

interconnected;

9

however, the proportion of human tracking within Canada’s

commercial sex markets is unknown. We took precautions throughout this

research not to conate all aspects of the commercial sex market with sex

tracking by using clear denitions distinguishing between tracking and legal

activity within the sex industry in which the person providing sexual services

is free from coercion and fear.

We conducted semi-structured interviews using an interview guide that

was developed using best practices in similar research projects identied

through the literature review. We provided interviewees with an overview of

the research project, and each participant provided consent at the beginning

of the interview. We continued to conduct interviews until we reached a level

of saturation, meaning that additional interviews no longer yielded new

information. We conducted a thematic analysis of the data to identify trends

among interview responses.

Law enforcement respondents

We interviewed 20 law enforcement respondents spanning 20 jurisdictions.

The vast majority (70%) of law enforcement interviewees were from municipal

services followed by RCMP (25%) and provincial agencies (5%).

Ocers interviewed came from a range of units responsible for human

tracking les including Vice, Guns and Gangs, Special Victims and

Counter-exploitation:

30% of respondents worked specically in human tracking units

70% of units were responsible for investigation of crimes not specic

to human tracking

95% of respondents conrmed that they had worked directly with at least

one victim/survivor of human tracking

Law enforcement respondents tended to work with fewer victims/survivors

of human tracking than those at frontline agencies. This is likely due to

two factors:

Victims/survivors may fear or distrust law enforcement

Identication and assessment of victims may vary between

law enforcement and frontline service providers.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

10

Introduction

Service provider respondents

We interviewed 49 service providers spanning 38 jurisdictions. The vast

majority (88%) of service provider participants were from frontline agencies

that work directly with victims/survivors of human tracking (82%). The

majority (61%) were program managers or coordinators who reviewed case les,

oversaw frontline sta or worked directly with survivors of human tracking as

part of their roles. Other respondents included Executive Directors (35%) and

Caseworkers (4%).

Of the agencies interviewed, 43% provide human tracking-specic programs

or services. The remainder of interviewees were either government department

representatives (7%) tasked with overseeing human tracking strategies, or

umbrella organizations/associations (6%) that did not provide direct services

to clients. While these organizations were limited in their ability to speak to the

individual needs and circumstances of human tracking victims and survivors,

they were credible sources of information on trends and broader issues faced

by victims and survivors and frontline delivery agencies.

Research Limitations

The Centre’s work encompasses both sex and labour tracking. However,

this report focuses on the types of sex tracking that apply to human tracking

corridors because our research was not able to conclude that the corridors are

being systematically used to propagate labour tracking in Canada. The Centre

looks forward to undertaking future research that will shed light on experiences

and trends in labour tracking, as well as other typologies of human tracking.

By its very nature, human tracking is a covert activity. Because sex tracking

is often hidden, dicult to detect, and frequently stigmatized, many victims and

survivors may never disclose their experiences to a frontline service provider or

law enforcement. As a result, the insights and perspectives shared by frontline

service providers in this research may not reect all forms of human tracking

occurring along corridors.

In the future, as data collection on human tracking grows across Canada,

it may be possible to more accurately identify the frequency with which

exploited individuals are transported along specic corridors. Since such

data does not currently exist, we have relied on the insights and perspectives

provided by interviewees to understand how human tracking corridors

operate within Canada.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

11

B

13

How Human Tracking

Corridors Operate

14

The Economics of Human

Tracking Corridors

17

Types of Sex Tracking

19

Characteristics of Victims and

Survivors of Sex Tracking

23

Characteristics of Trackers

In This Section:

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

How Human Tracking

Corridors Operate

H

uman tracking corridors are a distinctive component

of how human tracking operates in Canada; however,

they are only one piece of the puzzle. Not everyone who has

experienced human tracking has been moved through these

corridors and, for those who have, it may only be one part of

their experience.

Trackers use corridors

for three main reasons:

To obtain as much prot as possible

To lower risks since movement across

municipal and provincial jurisdictions

makes it harder for law enforcement to

detect, investigate and pursue human

tracking cases

To maintain control over the individuals

they are exploiting by reinforcing their

social and physical isolation and keeping

them confused and dependent.

1

2

3

The corridors identied in this report do not exist for the sole purpose of human

tracking. In fact, these primary transportation routes across Canada are used

for many purposes including transporting people and goods to various markets.

Along these corridors, trackers often use smaller circuits: regular tours around

an assigned district or territory.

10

They move victims along these circuits to

access markets where they can maximize prots according to market demand;

saturation (i.e., the number of “sellers” relative to “buyers); and the overhead

costs of operation for each population centre (e.g., hotel, motel or short term

stay, travel costs).

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

13

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

The Economics of Human Tracking Corridors

A key component of human tracking in Canada, and specically along

transportation routes, is the economic drive that underpins human tracking.

While many social and economic factors enable the existence of sex tracking

in Canada, the primary driver is money. Unlike other forms of sexual, physical and

psychological abuse, human tracking operates under a clear business model.

It functions within an economic market where the primary motivation of

trackers is to generate as much prot as possible. Our research indicates

that trackers utilize human tracking corridors to strategically maximize

prots and mitigate the risks associated with operations.

Maximizing Prot within a Competitive

Commerical Sex Market

On an economic level, human trackers operate under the same logic as any

other for-prot business in Canada. Their goal is to generate as much revenue

as possible while keeping their operational costs low so as to maximize prot

margins. Human tracking is fundamentally about prot seeking but, in contrast

to legal businesses, it circumvents the law and robs individuals of their human

rights. Trackers are known to hold and control the money received through

victims’ interactions with the commercial sex industry. They force and coerce

individuals into the sex industry and keep all of the revenue, which is the key

driver of their prot.

Revenue

($ received through the

sale of goods/services)

Operational costs

($ spent on enabling the

commercial transaction)

Prot

(Minus)

Persons tracked along human tracking corridors are largely advertised

through online escort ads, notably Leolist.cc. While determining the average cost

of commercial sex services was outside the scope of this research, a preliminary

scan of Leolist.cc shows that trackers can reasonably obtain $200-$400/hour

from each commercial sex exchange.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

14

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

The one hour price for “full service” will go from

$160-180 per hour in Montreal, but in Edmonton, they can

get $200-$300 for the same service. Trackers picked

up on this, and are sending them out for a week or so.

– Law enforcement respondent on human tracking corridors

Quotas are often imposed on sex tracking victims, and anecdotal evidence

suggests that they range between $500 and $1,000 per day. While overhead

expenses such as food, accommodation, clothing/makeup and travel do factor

into a tracker’s expenses, they are easily absorbed due to high net prot

margins resulting from the withholding of all revenues from the individual(s)

they are exploiting.

Interview respondents explained that trackers stay in a given city as long as

it is protable (anywhere from one night to several weeks) and they are not

detected by law enforcement. Entry into online commercial sex markets is

relatively cheap and easy. Trackers often post ads on behalf of the individuals

they are exploiting and manage every aspect of the exchange including location,

what sexual services will be provided and for what price, and the number of

buyers a victim must see.

Minimizing Risks

Human tracking, like other businesses, requires mitigating risks to ensure

stable and continuous operations. Because human tracking is an illegal activity,

the risks associated with business operations are signicant. In Canada, anyone

who is found guilty of human tracking is liable to “a) imprisonment for life and

to a minimum punishment of imprisonment for a term of ve years if they kidnap,

commit an aggravated assault or aggravated sexual assault against, or cause

death to, the victim during the commission of the oence; or b) imprisonment for

a term of not more than 14 years and to a minimum punishment of imprisonment

for a term of four years in any other case.”

11

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

15

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

To avoid being caught and potentially imprisoned, trackers have adopted

ways of operating that reduce risk by circumventing and evading the law

altogether. Consistently moving from place to place — between hotels,

houses, cities or provinces — helps avoid detection from law enforcement

and compliance with laws that would ultimately lower their prot and/or

jeopardize their ‘business’ altogether.

To reduce the risk that victims and survivors will leave them or report them to

law enforcement, trackers consistently move between cities and provinces

in an eort to maintain psychological control. Travel can keep people confused,

isolated and dependent on their trackers. Several interview respondents

provided accounts of victims and survivors who were unable to tell what cities

they had been tracked in because their trackers withheld information and

intentionally kept them confused about their geographic locations.

Moreover, trackers maintain strong psychological control over the individuals

they are exploiting, which can also reduce the need to use physical violence,

which in turn helps maintain high revenues and larger prot margins. “High-

end” commercial sex generates far higher revenue and rates than other forms

of commercial sex work, such as street-based sex work. Buyers are willing to

pay more because the ”seller” passes as being there willingly and conforms to

mainstream ideas of beauty and sexual attractiveness. Avoiding physical injury

or abuse is a central strategy used by trackers to maintain their business and

obtain the highest possible revenue per service.

The shorter amount of time spent in each city, the more

benecial it is for the trackers. It takes time for police

to set up an investigation. If they are only in town for a

couple of days, it’s harder to track.

– Law enforcement respondent on human tracking corridors

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

16

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Types of Sex Tracking

We asked interview respondents about types of tracking, including incidents

of sex and labour tracking, of which they had received rst-hand accounts

from victims and survivors. Interviewees mentioned the following types of known

sex tracking:

12

Escort services: These commercial sex acts primarily occur at temporary

indoor locations, such as hotels/motels, and are often arranged through

internet ads. Escort services were by far the most frequently mentioned type

of sex tracking by interviewees.

Illicit massage: The primary business of sex tracking and commercial sex

exchange is concealed under the façade of legitimate spa services.

Outdoor solicitation: Individuals are forced to nd commercial sex

customers in outdoor locations.

Residential sex tracking: Individuals are forced or coerced into

commercial sex acts at a non-commercial residential location, such as

a private/family home, or a drug distribution home (e.g., a “trap house”).

Pornography: Individuals are forced or coerced to participate in

pre-recorded sexually explicit videos and images.

Personal sexual servitude: Individuals are forced or coerced into providing

sexual acts/services in exchange for something of value. In these cases, the

tracker and the “buyer” are usually the same person. Examples include

survival sex, the permanent selling of a victim through a single transaction,

or within a forced marriage.

Remote interactive sexual acts: Individuals are forced or coerced to

participate in live streamed, interactive simulated sex acts or “shows”,

such as webcams, text-based chats or phone chat lines.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

17

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

When interviewees were asked about the sectors or types of tracking engaged

with specically along human tracking corridors, over half of service providers

and 90% of law enforcement ocers interviewed reported the widespread

use of escort services. Although other tracking typologies emerged from the

interviews, they were not identied as using human tracking corridors. This is

likely because other forms of sex tracking, such as illicit massage, pornography

and personal sexual servitude, may rely on the tracker having a stable location

for exploitation to occur.

Law enforcement responses

Types of sex tracking identied by service provider

and law enforment interview respondents

Service providers responses

Escort services Illicit massge Strip clubs Sex work

(details not specied)

Outdoor soliciation Residential sex tracking Pornography Personal sex servitude

Remote interactive

sexual acts

Mining camps Other

90%

55%

15%

12%

0%

2%

0%

2%

0%

2%

0%

4%

0%

14%

30%

31%

30%

29%

50%

24%

0%

4%

Figure 1: Interview responses to the following question: "What specic sectors are the survivors/

victims working in? Prompt for exotic dancers, sex workers, body rubbers, etc. or in the case of labour

tracking, hospitality, cleaning, domestic work etc." Responses do not add up to 100% because they

are not mutually exclusive.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

18

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Characteristics of Victims and Survivors of Sex Tracking

Women and girls of Canadian nationality make up the vast majority of sex

tracking victims and survivors identied by frontline service agencies and law

enforcement. Only a small proportion of law enforcement (10%) and service

provider respondents (16%) reported having previously worked with male or

trans-identied survivors.

Other socio-demographic characteristics are diverse among victims and

survivors. Interview respondents said that most of the victims and survivors

that they had worked with were under the age of 35, but the overall age range

was between 12 and 50. Victims and survivors aged 18-24 were the most

common age group reported by interviewees. Approximately half of interviewees

indicated that they had worked with a victim or survivor under the age of 18.

16%

89%

100%

16%

5%

47%

55%

57%

60%

37%

30%

16%

10%

84%

85%

2%

0%

20%

20%

10%

Law enforcement responses

Demographic characteristics of human tracking caseloads

among interview respondents

Service providers responses

Male Female

Gender Age Nationality

Other Under 18 18-24 25-34 35+ Canadian American Other

Figure 2: Interview responses

to the following question:

“Can you tell me about

some of the demographic

characteristics of people being

tracked?” Prompts included

for gender, age and country of

origin. Responses do not add

up to 100 because responses

were not mutually exclusive.

Interviewees who had worked with non-Canadian victims and survivors

identied the following regions of origin: Asia (China, Korea); Russia; Africa

(Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, Congo); South Asia; Central America (Colombia);

Philippines; Middle East; and Europe (Hungary).

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

19

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

The vast majority

of individuals

tracked in the

commercial sex

industry are

Canadian women

and girls

Respondents identied the following key characteristics of survivors:

prior or current involvement with the child welfare system

living in, or prior experience living in poverty

experiencing homelessness and/or precarious housing

history of substance abuse/addictions issues

history of trauma, abuse and/or domestic or sexual violence.

Individuals who are exploited within commercial sex markets, and who are

tracked along transportation routes, originate from communities across the

country. About a quarter of respondents (25% of law enforcement, 27% of

service providers) indicated that they had worked with survivors who were

local to the community in which they were exploited. In contrast, 40% of law

enforcement and 45% of service provider respondents worked with survivors

from another city within the same province.

Where are victims/survivors coming from?

Migration patterns of victims and survivors of human tracking

Coming from another province

Coming from another country

Coming from another city

within the province

Victims are local but

still being tracked

Survivors are local having

been tracked elsewhere

and have returned home

Coming from reserve

Don’t know/no response

Other

Law enforcement responses

20%

0%

0%

0%

10%

45%

40%

25%

Service providers responses

18%

14%

4%

4%

20%

45%

27%

2%

Figure 3: Interview responses

to the following question:

“Have you noticed any

trends in terms of where

victims are coming from?"

Prompt for whether they are

from the area, from another

city, province or country."

Responses do not add up to

100% because responses

were not mutually exclusive.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

20

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Among respondents, 45% of law enforcement and 21% of service providers

reported working with survivors who originated from another province.

Ontario and Quebec were the most commonly reported provinces of origin.

Law enforcement responses

Where are victims/survivors coming from?

Province of origin of victim and survivors of human tracking

Service providers responses

ON

NS

QC

AB

BC

MB

NB

55%

27%

2%

4%

5%

SK

Ontario

Manitoba

50%

20%

Quebec

20%

14%

British Columbia

5%

8%

Nova Scotia

New Brunswick

8%

10%

8%

Alberta

Saskatchewan

Figure 4: Interview responses to the following question: “Have you noticed any trends in terms of

where victims are coming from? Prompt for whether they are from the area, from another city, province

or country." Responses do not add up to 100% because responses were not mutually exclusive.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

21

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Although identifying human tracking is challenging, law enforcement

respondents mentioned several indicators used to assess whether someone

may be a potential victim:

a lack of identication since trackers often withhold the victim’s

identication as a way to control them

confusion, disorientation or a lack of knowledge about where they are

signs of fear or intimidation by the potential tracker, e.g., unwilling to make

eye contact, not allowed to speak for themselves.

A Note on Indigenous Women and Girls

Previous research in Canada has indicated that Indigenous women and girls

are more likely to experience commercial sexual exploitation compared to other

demographic groups.

13,14

In the current research, 53% of service providers

and 40% of law enforcement respondents indicated that they had worked

with survivors identifying as Indigenous. When asked to provide estimated

breakdowns of their overall caseloads, however, the vast majority stressed that

Indigenous victims and survivors did not represent a signicant proportion of

their cases.

When we asked our participants about the experiences of Indigenous

victims and survivors, we heard that they were not tracked through escort

services or transported through human tracking corridors to the same

extent as other demographic groups. Rather, Indigenous women and girls

are more likely to experience tracking after travelling to urban centres from

rural communities for reasons unrelated to exploitation, such as for medical

appointments, to begin school, or seek employment opportunities. Once in an

unfamiliar urban area, Indigenous women and girls may be preyed upon by

trackers, or they may engage in survival sex to meet their basic needs,

such as access to food and shelter.

Although our research did not corroborate previous ndings that show a higher

incidence of sex tracking among Indigenous women and girls, we cannot

conclude that this group is not over-represented among all human tracking

victims and survivors in Canada. Further research is required to understand

how human tracking impacts Indigenous women and girls.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

22

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Characteristics of Trackers

Dierent types of trackers operate within each type of tracking in Canada.

Tracker types can be understood according to the methods they use to

track people, and the business models under which they operate.

Respondents mentioned the following types of trackers:

Drug dealer

6%

10%

14%

10%

Family member

24%

5%

Forced

marriage

4%

2%

Bottom

6%

15%

Peer/friend

Body rub/

illicit massage

parlour owner/

operator

Law enforcement responses

Types of trackers identied

Service providers responses

49%

50%

Organized crime/

gang member

Boyfriend tracker/

“Romeo Pimp”

55%

45%

Figure 5: Interview responses to the following question: “Can you tell me about some of the

demographic characteristics of the trackers? How are the victims/survivors being recruited?”

Prompts included for gender, age and gang or group aliation. Responses do not add up to 100

because responses were not mutually exclusive.

Respondents most commonly associated movement along human tracking

corridors and circuits with boyfriend trackers/Romeo pimps and gang-aliated

trackers. Romeo pimps/boyfriend trackers tend to introduce psychological

and physical abuse over time, making the victim believe they are consenting

to their own exploitation and abuse (see How boyfriend trackers control and

coerce their victims).

15

Romeo pimps position themselves as boyfriends and

enter what look like consensual intimate partnerships with individuals before

convincing or coercing them into the industry.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

23

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Respondents also identied a strong interplay between gang-related trackers

and Romeo-style pimps. Many found it dicult to determine whether gang

members use Romeo pimp techniques to maintain a strong psychological hold

on victims to track them as part of the gang’s criminal activities, or if Romeo

pimps are also actually gang-aliated, but not necessarily tracking on behalf

of their gang.

Many respondents noted that while victims and survivors may mention gang

aliation as part of their experience, they rarely disclose details about which

gangs are most aliated with human tracking.

Who are the Trackers?

We asked interviewees to comment on any trends pertaining to the identities of

the trackers. While service providers may hear about trackers’ characteristics

from survivors, they rarely engage with trackers directly. Law enforcement

respondents often gain a better understanding of who trackers are through

their investigations; however, they can struggle to earn the same level of trust

and discretion that service providers can build with their clients.

The vast majority of respondents described trackers as male (84% of service

providers, 90% of law enforcement). However, 40% of law enforcement and 39%

of service provider respondents said they had worked with victims and survivors

tracked by other women.

No single age range or ethnic group is commonly associated with tracking.

Responses to this question varied greatly across interviews, and were broadly

reective of demographics in Canada and the geographic locations of

respondents.

The most common characteristic of trackers is that they are able to assess and

manipulate vulnerability to their own benet; that ability transcends class, ethnic

and gender boundaries.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

24

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

1. Targeting

and Luring

2. Grooming

and gaming

3. Coercion and

manipulation

4. Exploitation

and control

How Boyfriend Trackers Control and Coerce Their Victims

Our research indicates that “boyfriend” trackers often utilize transportation

routes to prot from victims, as well as, keep them disoriented and dependent.

Moving victims through human tracking corridors and circuits, however, is just

one tactic that boyfriend trackers use to control and exploit individuals. These

trackers control their victims in four stages:

Targeting and luring

In this stage, trackers seek and identify potential victims who are

vulnerable to control and manipulation. They look for people with low

self-esteem, who may have problems at home, be in the child welfare

system, or have emotional, developmental or substance abuse issues.

Trackers target individuals by surveilling social media for young

people showing signs of low self-esteem, loneliness and lack of

support, or spaces where vulnerable youth tend to frequent including

homeless shelters, youth drop-in programs, malls, group homes and

foster care homes.

16

1

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

25

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Grooming and gaming

Trackers use deceit and fraudulent role play to create a sense of

dependency, trust and intimacy with people.

17

They may romance

someone by buying gifts and spending money, or by taking the time

to ask them about their dreams, aspirations and goals.

18

Trackers

specically target individuals who have never experienced this type

of positive emotional armation before. This helps them gain trust

while incrementally isolating individuals from family and friends.

A tracker will oer potential victims anything to make them feel

loved, appreciated, safe and accepted, and then use that to put a

wedge between them and their support network. Another tactic that

trackers may use during this stage is substance dependence, by

encouraging substance use, or providing an ample supply of drugs

and/or alcohol.

Coercion and manipulation

In this stage, trackers start to send mixed messages to victims.

They begin withholding things they previously gave to make them feel

loved, appreciated and cared for, such as emotional intimacy, physical

aection, alcohol or drugs, and money or gifts. They also use the

information they have gained about the potential victim to manipulate

them to act in a certain way.

Boyfriend trackers often desensitize individuals to sexual acts they

may otherwise be uncomfortable doing. They may tell victims that

they owe the tracker for everything given during the grooming

and gaming stage. They may also say that commercial sex work is a

viable, easy way for victims to make quick money to pay their debts.

Trackers may also manipulate the goals and aspirations of the

individual they are seeking to exploit, and mislead them into believing

that commercial sex work is a short-term sacrice needed to build a

better life – that selling sex for a short time will be their ticket out.

2

3

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

26

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

This stage may also include normalizing or glamorizing the

commercial sex industry. In some cases, trackers may use peers

to introduce victims to the industry. Individuals may initially consent

to engaging in commercial sexual activities because they feel it is

within their control and that they are doing so voluntarily. Trackers

may also start isolating a potential victim from family and friends,

and use psychological or emotional manipulation to foster a distrust

of authorities.

Exploitation and control

In the exploitation and control phase, a tracker will likely have

complete control over identity documents, cellphones, movements

and money of the individual(s) they are exploiting. Individuals may

be fully reliant on the tracker to provide all of their basic needs,

such as housing, food, clothing and drugs and alcohol. Withholding

drugs and alcohol is a powerful tactic among victims who

experience addiction or dependence on a substance.

During this stage, trackers threaten individuals to perform

commercial sexual acts on their behalf. The tracker may extort

victims by threatening to share intimate pictures, as a way to

leverage and coerce them into the commercial sex industry. Victims

and survivors are often afraid of speaking out against their tracker

because of the risk of violence to themselves or others, deportation

or signicant interpersonal risks.

Once a tracker enters the exploitation and control stage, victims

may start to realize that they are not actually in a loving, supportive

or safe relationship. By keeping victims isolated from friends, family

and support networks, trackers make them doubt themselves

and prevent them from getting positive reinforcement and support.

Trackers may also use psychological tools such as gaslighting

to make an individual feel they are the cause of their own

unhappiness, or that they have no reasonable claim to be unhappy

in the rst place.

19

4

* Gaslighting is a subtle and covert type of emotional and psychological abuse that involves

a variety of manipulative techniques to make a target undermine their own sense of reality

and mental stability.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

27

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

The Geography of Human Tracking Corridors and Circuits

Human tracking corridors exist in nearly every province/territory in Canada,

with the notable exception of Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut. While

both human tracking and demand for commercial sex services do exist in

Northern regions, the limited transportation infrastructure means that trackers

cannot move victims quickly and eciently between population centres and

commercial sex markets. The conditions required to enable human tracking

corridors simply do not exist in these smaller markets with comparatively less

demand but higher overhead costs associated with travel.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

ON

NS

QC

AB

BC

NB

SK

MB

Hudson Bay

Manitoba

SaskatchewanAlberta

British

Columbia

Ontario

Quebec

New Brunswick

Nova Scotia

Labrador Sea

United States

Land corridors DestinationsAir corridors

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

28

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Intra-provincial Corridors

Our research indicates that intra-provincial corridors connect cities and

commercial sex markets in a single province. These geographically short circuits

are easy to travel by car. They may also connect to much smaller commercial sex

markets on the way to larger markets, staying a day or two in even the smallest

towns if they can arrange enough commercial sexual exchanges to make it

protable for trackers.

Ontario’s Hwy 401 Corridor

Ontario’s 401 Highway connects Montreal, QC and Windsor, ON.

Between these two end points, there are several populous urban

centres. Trackers may operate along the entire 401 corridor, or

capitalize on movement through a densely populated region,

such as the Greater Toronto Area.

Sarnia

Windsor

Chatham-Kent

London

Kitchener

Guelph

Hamilton

Mississauga

Toronto

Peterborough

Belleville

Kingston

Ottawa

Cornwall

Montreal

Oshawa

Barrie

Owen Sound

Lake Ontario

Lake Erie

Lake Huron

United States

Ontario

Quebec

401 Highway corridor Commercial sex marketsMajor roads

Example

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

29

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Calgary – Edmonton – Fort McMurray/Grande Prairie

Alberta’s human tracking corridors connect the province’s largest

online commercial sex markets, while also accessing markets aliated

with extraction work camps in Fort McMurray and Grande Prairie.

Interview respondents commented that this corridor is used by

both trackers local to Alberta and those from outside the province,

notably from Ontario and Quebec. A growing trend in this corridor is

the number of victims and survivors from Quebec who speak little to

no English. Not only do language barriers serve as another method of

control, but it is also believed that sex buyers see women from

Quebec as exotic and novel.

Grande Prairie

Edmonton

Lloydminster

Calgary

Ban

National Park

Of Canada

Jasper

National Park

Of Canada

Peace River

Athabasca

St. Paul

Drumheller

RedDeer

Canmore

Bonnyville

Cold Lake

Fort McMurray

Alberta

Saskatchewan

British Columbia

Corridors Major roads

Destinations

Example

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

30

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Inter-provincial corridors

Our research indicates that inter-provincial corridors occur when trackers

transport victims across provinces to access various commercial sex markets.

They are largely organized around accessing the most competitive and highest

paying markets. Because of the additional operational costs associated with

ying or driving long distances, inter-provincial corridors tend to run between

large urban centres with large markets.

Once a tracker and victims arrive in a new province, they may stay and

capitalize on the major urban commercial sex market in the city of arrival,

or they may access other intra-provincial corridors within that province.

Canada’s West Coast Circuit

The Quebec – Alberta corridor was one of the most commonly identied

by interviewees, with a noticeable trend in the tracking of young women

from Quebec in central and western Canada, most notably Alberta.

Law enforcement respondents specically noted the tracking of victims

from Montreal to Calgary by airplane. Victims either travel with their

trackers, or may travel alone and are met by trackers or an associate

upon arrival in Alberta. Trackers and victims may stay in Calgary and

arrange for commercial sex interactions in hotels near the airport or

downtown, or trackers may move victims along the intra-provincial

corridor between Calgary and Fort McMurray.

Example

Manitoba

Saskatchewan

Alberta

British

Columbia

Ontario

Quebec

United States

Edmonton

Calgary

Fort McMurray

Saskatoon

Regina

Vancouver

Grande

Prairie

Winnipeg

Toronto

Ottawa

Montreal

Quebec

City

Land corridors DestinationsMajor roads

Air corridors

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

31

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

The Trans-Canada Highway

Our research ndings conrm previous anecdotes about the scope

and scale of sex tracking in Canada. Tracking occurs where there

is a highway and access to the internet. The Trans-Canada highway

in particular functions as a corridor that connects to commercial sex

markets within all provinces, and across the country.

Highways 11 & 17 Northern Ontario – Winnipeg, Manitoba

Trackers use Highways 11 & 17 to move victims from Sudbury and

Thunder Bay through Northern Ontario and to connect to the online

commercial sex market in Winnipeg. While the “payo” may not be as

large as in other parts of Canada due to the long distance between

smaller online commercial sex markets, trackers view the low

population density and relative remoteness of these highways

as a benet in eorts to avoid detection by law enforcement.

Manitoba

Ontario

United States

Winnipeg

Thunder Bay

Sudbury

Sault Ste.

Marie

Lake Superior

Land corridors

Destinations

Major roads

Manitoba

Saskatchewan

Alberta

British

Columbia

Ontario

Calgary

Vancouver

Regina

Saskatoon

Red Deer

Brandon

Winnipeg

United States

Land corridors DestinationsMajor roads

Examples

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

32

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Halifax, Nova Scotia – Moncton, New Brunswick

Within Atlantic Canada, the stretch of the Trans-Canada

Highway between Halifax and Moncton was the most frequently

mentioned by interviewees, and well-known human tracking

corridor. Trackers go to Moncton not only to connect to the

online commercial sex market, but also to access the commercial

markets in strip clubs. Strip clubs operate in New Brunswick

but are not legally permitted in Nova Scotia.

Land corridorsMajor roads Destinations

Moncton

Halifax

Amherst

Saint John

Bay of Fundy

Truro

Dartmouth

New Glasgow

Port

Hawkesbury

Cape Breton

Island

New

Brunswick

Novascotia

Prince

Edward

Island

Example

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

33

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

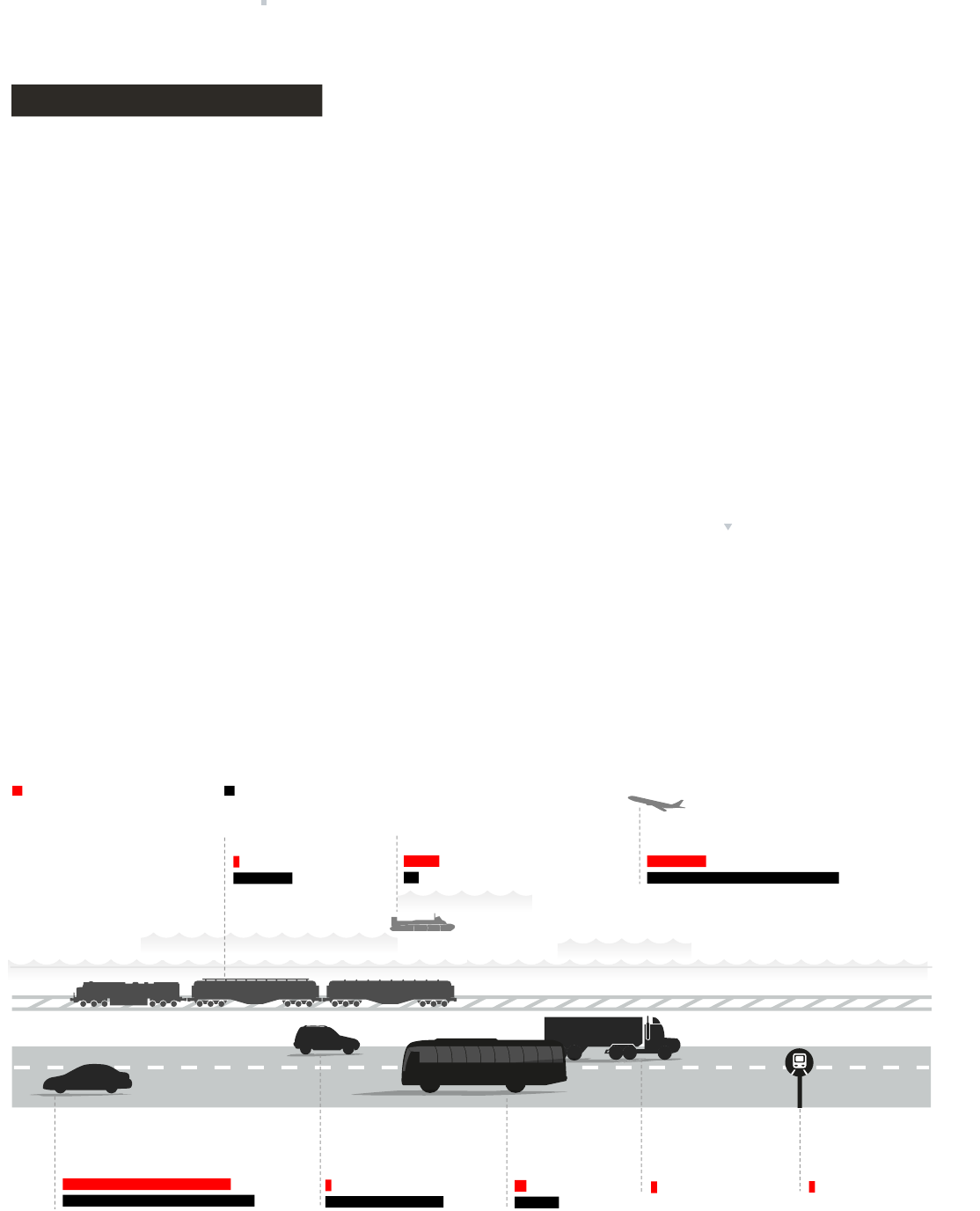

Methods of Transportation

Cars are by far the most frequently used method of travel in human tracking

corridors, especially along circuits. The overhead costs associated with driving

are lower than for air travel, and trackers can be nimble and adjust travel routes

according to demand for commercial sexual services.

Law enforcement respondents stressed how rental cars are used to avoid

detection and evade law enforcement. Trackers often rent multiple cars at

various stages of a corridor to make identication more dicult. Renting vehicles

with fake identication makes it even more challenging for law enforcement to

track the movements and actions of trackers. Using the names of victims and

survivors when renting cars helps control and coerce victims into commercial

sex. For example, trackers may threaten to damage or withhold the rental

car, resulting in potential charges against the victim, unless the victim does

as they are told.

Airplanes are also used to transport victims along human tracking

corridors, primarily when a signicant distance exists between markets/cities

along the corridor, and there are limited market stops between the rst and

nal destination. Flights are used when car travel is either impossible or

very inconvenient.

Law enforcement responses

Methods of transportation used along human tracking corridors

Service providers reponses

Car

(owned by tracker

or not specied)

Rental Car Bus Truck

Public Transit

Plane

57%

65%

2%

40%

20%

65%

4%

15%

2% 2%

Train

2%

20%

Boat

12%

5%

Figure 6: Interview responses

to the following question:

“What mode of travel is used

when they are travelling?

Prompt for personal car, bus,

train, plane, hitch-hiking,

ride shares, taxis etc.”

Responses do not add up to

100% because responses

were not mutually exclusive.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

34

How Human Tracking Corridors Operate

Sites of Exploitation

Most respondents indicated that tracking along corridors took place

through escort services in hotels, motels, short term stays, and private

residences/condos. Despite overhead costs associated with travel, the total

amount of revenue generated by one day of tracking greatly outweighs

the costs of operation.

Law enforcement respondents pointed to a noticeable increase in trackers’

use of short term stays, which can pose challenges to investigations. For hotels

and motels, more opportunities exist to train sta in detecting and reporting

human tracking. Relationships can also be forged with hotel management and

cleaning sta to report to management or call the Canadian Human Tracking

Hotline if they suspect human tracking is taking place.

Short term stays oer fewer opportunities to equip sta with knowledge about

human tracking. The owners and operators may never actually meet the renter,

and trackers may fully remove any signs of human tracking before they leave

the short term stay or the owner returns.

Trackers may also be hard to identify if they are not directly supervising the

individuals they are exploiting. Law enforcement respondents stated that

trackers might be in a separate room from the victim in a hotel, motel or short

term stay, or in the nearby vicinity to arrange calls, schedule purchasers and

collect money.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

35

C

In This Section:

37

Exiting Human Tracking

42

Service Needs and

Systems of intervention

48

Conclusion and

Recommendations

51

Appendices and Endnotes

Exiting Human Tracking

Exiting Human Tracking

W

hy do victims of human tracking not just leave if they are

not being physically restrained, conned or controlled?

Escaping trackers can be psychologically and emotionally

challenging for victims as well as physically dangerous. Trackers

forge strong trauma bonds with the individual(s) they are exploiting

to create a sense of dependency and isolation. Controlling and/or

detaining victims is necessary to continue exploiting them.

20

Control is achieved through emotional, physical and sexual

violence, as well as economic abuse.

21

Constant monitoring and

surveillance, and forging divisions between victims and their

previous support networks (e.g., friends, family, community

members), can make victims feel escape is impossible and

they have nowhere to turn.

22

Barriers to Exiting

Survivors face four mutually reinforcing types of barriers when they attempt

to leave their tracker:

23

Individual: The negative psychosocial impacts of tracking can damage

the sense of self-ecacy that victims require to leave their controller. These

impacts include experiencing trauma, shame, internalized stigma, substance

abuse and mental illness, health issues and a lack of awareness of available

external resources.

Relational: Trackers often intentionally create cleavages between

individuals they are exploiting and their social and support networks.

Strained or limited relationships with family and friends can reinforce

dependence on trackers.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

37

Exiting Human Tracking

Structural: Exiting a human tracking situation requires transitioning

to a dierent kind of life, which ideally is non-exploitative and enables

survivors to actualize their potential. Structural factors aect a victim’s

ability to leave, including barriers to employment, prior criminal records,

educational attainment, ability to maintain housing, staying out of poverty

and achieving economic self-suciency.

Societal: Sex tracking survivors and consensual sex workers face

tremendous stigma as a result of their experiences in the commercial sex

industry. Negative attitudes can result in discrimination against survivors

or further social isolation or stigmatization.

24,25,26

Service providers identied the following barriers that victims and survivors

face in accessing services: stigma, challenges navigating the service system,

addictions, lack of appropriate housing/shelter, lack of emergency services,

lack of trust in the system, fear and safety concerns, lack of trauma-informed

services, and lack of exible services aligned to meet their needs.

Barriers to accessing services, service provider responses

4%

Income support is insucient

39%

Stigma

16%

Addictions

22%

Don’t trust system/hard to build trust

16%

Lack of trauma-informed services

16%

Lack of appropriate housing/shelter

Don’t identify as tracked victim/survivor

8%

10%

Other

16%

Feel/safety concerns

4%

Mental health issues

2%

Trauma bond with tracker

2%

Prior criminal record

Figure 7: Service provider responses to the following question: “What barriers or obstacles do

survivors or victims face when accessing services?" Responses do not add up to 100% because

responses were not mutually exclusive.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

38

Exiting Human Tracking

Law enforcement respondents had a slightly dierent perspective with limited

nancial options/insucient income support (30%) cited most frequently, along

with stigma and addictions. Social assistance rates and provincial minimum

wages provide subsistence income at best and are far less than what victims

would “earn” on any given day. Even though victims are often forced to hand

over their earnings to trackers, the idea of working a minimum wage job or

relying on social assistance presents signicant barriers to exiting.

Figure 8: Law enforcement responses to the following question: “What barriers or obstacles do

survivors or victims face when accessing services?" Responses do not add up to 100% because

responses were not mutually exclusive.

Barriers to accessing services, law enforcement responses

Income support is insucient

Stigma

Addictions

Don’t trust system/hard to build trust

Lack of trauma-informed services

Lack of appropriate housing/shelter

Don’t identify as tracked victim/survivor

15%

15%

15%

15%

15%

20%

20%

30%

Other

Feel/safety concerns

10%

10%

10%

10%

Mental health issues

Trauma bond with tracker

Prior criminal record

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

39

Exiting Human Tracking

The “Cycle of Change”

Research has identied a ve-stage model of change to describe the process

of exiting human tracking relationships:

27

The

Cycle

of

Change

15

24

3

Precontemplation:

person is unaware

there is a problem

and has no intention

of making change.

Maintenance:

if change has persisted

for 6 months or longer,

individuals are in a

maintenance stage.

Here, the ultimate goal

is to avoid relapse.

Contemplation:

person is aware there

is a problem and is

considering change,

but hasn't made any

commitments to do so.

Action:

person makes visible

and overt behaviour

changes, such as

leaving a tracker.

Preparation:

person starts making small changes to their

behaviour with the intention they will make

additional, larger changes in the near future.

These stages are not linear. Victims and survivors may go back and forth

between stages multiple times before they exit or are able to graduate towards

a stage of maintenance.

Trackers use multiple methods to control the individuals they are exploiting and

prevent them from progressing through the stages of the cycle of change.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

40

Exiting Human Tracking

Trackers often leverage the stigma associated with commercial sex work to

prevent victims from reaching out for support or help. Psychological research

has demonstrated the impact of stigma on preventing someone from reaching

out for help.

28,29

Stigma can be understood as the attribution of inferior status

to a person, or group of people, that either have a visible trait that is perceived

to be discrediting (e.g., physical disability) or some perceived moral defect.

30

Individuals who have engaged in the commercial sex industry, either voluntarily

or by force, are among the most stigmatized groups in Western society.

31

While little research exists on the impact of stigma on help-seeking among

survivors of sex tracking, some research does show that individuals who

perceive stigma, or who have been previously discriminated against due to their

imposed stigma, fear rejection and are less likely to seek support directly from

service providers.

32

Instead, stigmatized people are more likely to nd indirect

ways of seeking support, such as dropping hints about a problem when asking

directly for other supports: ”For instance, instead of asking for emotional support

from a friend or a family member, individuals may choose to hint that a problem

exists or act sad without giving details or directly stating reasons for

the sadness.”

33

These factors can be further aggravated when victims are transported along

human tracking corridors and circuits. Moving victims to dierent parts of the

province and/or country makes safety and exit planning even more challenging.

Not knowing where they are, to whom they could go, or how they could safely

leave their tracker makes preparation and action even more dangerous for

victims looking to exit.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

41

Service Needs and Systems of Intervention

Service Needs and

Systems of Intervention

T

o better understand what services survivors require

when exiting tracking, we asked respondents about

survivors’ most urgent needs upon seeking help. Respondents

stressed that, in many cases, survivors often escape their

trackers with little more than the clothes on their backs.

They have multiple layers of trauma and abuse.

They need an entire wrap around model – dental,

tattoo cover up, treatment for addiction, medical care.

One wanted to change their hair colour to be less

recognizable. Domestic violence and sex assault victims

often don't have these needs.

– Service provider respondent on how the needs of

human tracking victims dier from other groups served

Services need to be available immediately once a victim decides to leave,

and access to support needs to have as few rules attached as possible.

Making access to support conditional on other actions, such as reporting

to law enforcement, can cause signicant barriers for victims and survivors.

The severe threat of violence coupled with the tremendous psychological

manipulation and control associated with tracking requires an immediate and

eective response embracing a harm-reduction approach. Service providers

need to meet all basic needs of survivors including housing/shelter, food, clothes,

medical care, emotional support and cell phones/communication tools.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

42

Service Needs and Systems of Intervention

Barriers to accessing services are not mutually exclusive: victims and survivors

may experience multiple barriers concurrently or separately. Service providers

also spoke to the complexity of care needs. Victims and survivors can present

with multiple immediate needs including housing, addictions, mental health,

basic needs (food, clothing, basic necessities) in addition to requiring a more

comprehensive array of transitional and long-term supports.

By far, the most dominant service needs are related to housing, specically safe

and appropriate housing. Respondents highlighted the heightened safety and

security risks that survivors face upon leaving their trackers, and that safe

emergency housing is critical to helping survivors exit. They dened safety in

terms of housing needs in several ways:

Emergency housing needs to keep survivors physically safe from their

trackers. Survivors need support for safety planning, and they need to be

located somewhere where their tracker cannot nd them. This includes

being protected and anonymous from the tracker’s associates, including

other women or victims of tracking who may nd or identify them in

emergency shelters.

Housing needs to provide an emotionally safe space. According to 40%

of service providers and 20% of law enforcement respondents, stigma and

shame are among the biggest barriers for victims and survivors to access

services; housing options must help clients overcome those barriers.

Survivors need access to trauma-informed, non-judgmental spaces in the

immediate and intermediate stages of leaving their tracker.

Housing needs to be low-barrier and take a harm-reduction approach to

supporting survivors. Rules often associated with non-human tracking

specic shelters, such as violence against women shelters and family

shelters, can be challenging for survivors due to potential addiction issues,

intense trauma and physical and medical needs immediately upon exiting.

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

43

Service Needs and Systems of Intervention

Trauma-informed programs

Close to three-quarters of all respondents highlighted that the service needs of

tracking survivors were dierent than those of other clients, including people

who have experienced other forms of violence, sexual assault and abuse. The

biggest dierence is that trauma-informed services are an absolute requirement

for tracking survivors who have signicantly higher and more complex levels of

trauma. Many become dependent on substances as a means of self-medication

and coping. Other services, often needed immediately, include addictions and/or

detox services and income support (i.e., help accessing social assistance).

Respondents also stressed that survivors often face more complex challenges

and more co-morbidities than other clients, meaning there are two or more

signicant physiological or psychological conditions or diagnoses.

Victims and survivors of human tracking are often placed on the far end

of the complexity continuum of trauma, which is associated with a signicant

amount of shame and heightened vulnerabilities including anxiety, panic

disorder, major depression, substance abuse, and eating disorders as well

as a combination of these.

Many service providers stressed that trauma-informed programs and services

should be central in victims’/survivors’ care plans.

Trauma and

Trauma-Informed

Services

What is trauma?

According to the Centre for Addiction

and Mental Health, “Trauma is the

lasting emotional response that often

results from living through a distressing

event. Experiencing a traumatic event

can harm a person’s sense of safety,

sense of self, and ability to regulate

emotions and navigate relationships.

Long after the traumatic event occurs,

people with trauma can often feel

shame, helplessness, powerlessness

and intense fear.”

34

What are trauma-informed services?

Trauma-informed systems of care are

intentionally designed to respond to, and

address, the trauma-related needs of

victims and survivors and are based on

the following set of core principles:

35

• Trauma is a dening life event that can

profoundly shape a victim’s sense of self

and their sense of others

• The victim’s behaviours and symptoms

are coping mechanisms

• The primary goals of services are

empowerment, symptom management

and recovery

• The service relationship is collaborative

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

44

Service Needs and Systems of Intervention

Service provision challenges

The combination of safety concerns, physical threats, psychological control,

dependence, trauma bonding and the constant surveillance by trackers means

that when survivors choose to exit, the response needs to be immediate. The

window of time for a victim to exit can be incredibly short. If missed, it could

end up causing more harm to victims and survivors due to potential retaliation

from trackers, reinforcing social isolation and stigma. Victims moved along

human tracking corridors could subsequently be moved to another part of the

province or country and may not be traceable again.

Challenges in providing services to victims and survivors of human tracking

vary slightly between service providers and law enforcement; however, the

largest common challenge is a lack of funding and resources to do the job well.

Close to half of all respondents said that lack of appropriate, sustainable and

adequate funding presents a real challenge to the ability to provide services and

supports to survivors. Service providers and law enforcement respondents both

stressed that there is simply not enough funding or programming to meet the

needs of victims and survivors. It can be incredibly dangerous when victims are

attempting to leave their tracker without the necessary supports and resources

in place to do it safely.

It can be really hard to get statements from victims. Asking

a woman to come in and disclose some of the worst things

that have ever happened to her, or that she’s done, to a

stranger is not ok. I can't expect them to have blind trust.

Having to retell their story constantly is a huge barrier,

especially when they can be treated like they are the guilty

ones. When the victim is treated like a liar, you end up with

delays and the need to re-tell their stories multiple times. It

can be very, very heavy on victims.

– Law enforcement respondent on building trust with victims and

survivors, and navigating the judicial system

Human Tracking Corridors in Canada

45

Service Needs and Systems of Intervention

Law enforcement respondents stressed that it was challenging to investigate

and pursue human tracking cases because of insucient full-time equivalent

sta to follow through on investigations, and inadequate resources due to other

caseload pressures. Only 30% of law enforcement interviewees worked in

dedicated human tracking units.

Of the frontline service delivery partners interviewed, 43% delivered

human tracking specic programs with dedicated funding, whereas

83% of all respondents regularly worked with victims and survivors of

human tracking directly.

The role of law enforcement in the continuum of support services for survivors

is much narrower than that of service providers. Service providers tend to

engage with survivors in more comprehensive and long-term ways. Police hold

the primary responsibility for enforcing the law, including ensuring the safety of

survivors and pressing charges against trackers. Service providers, however,

are more appropriately positioned to support survivors throughout the cycle of

change, regardless of whether charges are being pressed.

Figure 9: Interview responses to the following question: "Which obstacles do you encounter in