Proximity

of Care

A New Approach to Designing

for Early Childhood

in Vulnerable Urban Contexts

2

1

This document is a product of the

collaboration between Arup and the

Bernard van Leer Foundation.

We are grateful for the input and advice

of a range of internal and external

contributors. Particular thanks are due to

Patrin Watanata and Ardan Kockelkoren

of the Bernard van Leer Foundation for

their guidance and support.

Contacts

Dr. Sara Candiracci

Associate Director

International Development, Arup

Cecilia Vaca Jones

cecilia.VacaJones@bvleerf.nl

Executive Director

Bernard van Leer Foundation

Proximity of Care

A New Approach to Designing for Early Childhood

in Vulnerable Urban Contexts

Arup is an independent muti-disciplinary rm with

more than 14,000 specialists working across every

aspect of today’s built environment. Our mission to

Shape a Better World is driven by our commitment to

make a real difference, stretch the boundaries of what

is possible, help our partners solve their most complex

challenges and achieve socially valuable outcomes.

The Arup International Development team

partners with organisations operating in the

humanitarian and development sector, to

contribute to safer, more resilient and inclusive

communities and urban settings in emerging

economies and fragile contexts around the globe.

The Bernard van Leer Foundation is an independent

foundation working worldwide to inspire and inform

large-scale action to improve the health and well-being

of babies, toddlers, and the people who care for them.

The Urban95 Initiative aims to improve, through

urban planning, policy, and design, the way babies,

toddlers, and the people who care for them live,

play, interact with and travel through cities.

The Urban95 Initiative asks a bold but simple question:

“If you could experience the city from 95cm - the

height of a 3-year-old - what would you change?

”

Lead Authors

William Isaac Newton

Dr. Sara Candiracci

Arup

Contributors

Jose Ahumada

Siddarth Nadkarny

Sachin Bhoite

Arup

Patrin Watanatada

Ardan Kockelkoren

Bernard van Leer Foundation

Dr. Nerea Amoros Elorduy

Creative Assemblages

CONTENTS

Introduction 4

Why Early Childhood Development Matters 6

Why an Early Childhood Focus in Vulnerable Urban Contexts 10

What we mean by 'Vulnerable Urban Contexts' 12

The Proximity of Care Approach 24

Beneciaries and their Needs 30

Recommendations: Household Level 44

Recommendations: Neighbourhood Level 46

Recommendations: City Level 48

What’s Next? 50

Denitions 52

Bibliography 54

End Notes 57

4

Introduction

Despite the importance of

early years to our personal

and social development, the

experience of 0-5 year olds

has been largely ignored

in the design of our cities.

If we design and plan

from their perspective -

95cm off the ground - the

environments we create

can include and bring

together people of all ages.

Jerome Frost

Global Cities Leader, Arup

This publication presents the

challenges and opportunities

confronting early childhood

development in vulnerable urban

contexts, derived from specialised

research by Arup and the Bernard

van Leer Foundation (BvLF).

The data is clear: vulnerable urban

areas such as refugee and informal

settlements house a growing

population in critical need, and the

number and size of these areas will

only increase in the coming decades.

While the specics of these

vulnerable areas vary, they

consistently pose major

challenges for children’s optimal

development.

1

Living in these

contexts has particularly

signicant negative impacts on

young children aged 0 to 5.

2

At present, governments,

development and humanitarian

organisations, and urban practitioners

devote little attention to the specic

needs of the 0-5 age group in projects

aimed at improving conditions in

informal and refugee settlements.

This age group’s needs are different

than those of older children but are

often ‘lumped in’ with them from a

planning and policy perspective, or

worse, go entirely unrecognised.

5

In addition, the complexity of

vulnerability in these contexts

makes it difcult to design

and implement effective early

childhood development solutions

that consider the inuence

of the built environment.

Arup and BvLF have partnered to

help bridge this gap. The Proximity

of Care approach was developed to

better understand the needs and

constraints faced by young children,

their caregivers, and pregnant women

in informal and refugee settlements;

and to ultimately help improve their

living conditions and well-being.

The Proximity of Care approach

is at the core of a Design Guide

that we are developing to help

decisionmakers and urban planners

mainstream in their projects, policy,

and processes the needs of young

children, caregivers, and pregnant

women living in vulnerable urban

contexts, and to prole their work

as child- and family-friendly.

To ensure the needs of the Design

Guide’s end users are properly

met, we are working closely with

urban practitioners operating in

informal and refugee settlements,

and with development and

humanitarian organisations.

In particular, we are partnering with

Civic, Catalytic Action, Konkuey

Design Initiative (KDI), and Violence

Prevention through Urban Upgrading

(VPUU), who are operating in

vulnerable urban contexts in various

sites across Jordan, Lebanon, Kenya,

and South Africa respectively.

We are also strengthening

relationships with government

authorities in the countries in

which we operate, as they are the

standard bearers for development.

The Design Guide will be released

in the fall of 2020, and is intended

to be a practical tool of rst resort

for urban planners, city authorities

and development actors working

in challenging urban contexts.

Arup and BvLF’s ultimate aim is to

support these professionals to design

and build inclusive, liveable, safe

and climate-resilient urban spaces

where young children can thrive.

6

Why Early

Childhood

Development

Matters

The early years of a child’s life are

crucial for healthy physical and

mental development.

3

Neuroscience

research demonstrates that a

child’s experiences with family,

caregivers and their environment

provides the foundation for

lifelong learning and behaviour.

4

Cognitive evolution from birth to

age ve is a ‘golden period’ during

which the stage is set for all future

development, including core skills

acquisition, establishment of healthy

attitudes and behaviours, and

ourishing of mature relationships.

5

80% of brain architecture develops

in the prenatal period, and 60% of

adult mental structures develop

in the rst three years of life.

6

80% of brain architecture

develops in the prenatal

period, and 60% of

adult mental structures

develop in the rst

three years of life.

Negative outcomes resulting from

compromised Early Childhood

Development are signicant.

7

Long-term studies of children from

birth show that developmental

inhibition in the rst two years

of life has harmful effects on

adult performance, including

lower educational attainment

and reduced earning.

12

The lifelong costs of early decits are

physical as well as cognitive: evidence

indicates that adult illnesses are both

more prevalent and more serious

among those who have experienced

adverse early life conditions. These

socioeconomic and health issues

can persist over generations.

13

Without effective intervention,

developmental decits can become

a cycle of lost human capital.

Improving early childhood

development, on the other hand,

acts as a social and economic engine

for communities and societies.

Cognitively healthier children are

more productive citizens, and

quality early childhood development

provides a competitive advantage

for national populations.

14

To develop to their full potential,

babies and toddlers require not

only the minimum basics of

good nutrition and healthcare,

clean air and water and a safe

environment; they also need

plenty of opportunities to explore,

to play, and to experience warm,

responsive human interactions.

10

To a large degree, the establishment

of healthy patterns in human

relationships depends upon the

physical environment children

inhabit in their very rst years.

11

The characteristics of physical

space impact learning and

memory formation;

8

chronic

noise exposure can result in

lower cognitive functioning and

unresponsive parenting;

9

crowding

can elevate physiological stress

in parents and cause aggressive

behaviour in young children.

For young children to make the

most of their surrounding built

environment, those places need to

cater to age-relevant developmental

needs, while providing affordances

and barrier-free access for caregivers.

Improving early childhood

development acts as

a social and economic

engine for communities

and societies.

8

Child-friendly urban planning

should engage children, parents/

caregivers and the wider community

in assessment and co-creation

activities early in the process.

Differences in age groups need

to be considered to fully address

beneciaries’ requirements

and engagement modes.

Early childhood development is the

key to ensuring that children grow

up into strong, resilient, thriving

adults. Ensuring that children reach

their developmental potential

requires support from families,

communities, and policy; this holistic

approach is particularly important

in vulnerable urban contexts.

While young children have very

different needs than those over

age 5, those needs often remain

invisible to government leaders or

are ‘lumped in’ with those of older

children from a planning perspective.

Young children need well-developed

and well-maintained child-friendly

infrastructure, a network of

places that allow them to develop

physically, mentally, and socially.

39

Age-appropriate design can mean

changes in scale,

40

as well as

inclusion of different types and

sources of stimulation to help

develop ne and gross motor skills,

engage language and cognition

abilities, and foster socialisation.

41

Young children also need clearly

communicated, well-understood

and consistently enforced plans and

policies that defend and support

their rights without distinction,

regardless of where they live.

The involvement of young

children, their caregivers, and

pregnant women in municipal and

community decision-making, policy

development and urban planning

is key to shaping child-friendly

urban environments that account

for very young children’s specic

needs, capacities, and interests.

42

While young children

have very different needs

than those over age 5,

those needs oen remain

invisible to government

leaders or are 'lumped

in' with those of

older children from a

planning perspective.

9

© Catalytic Action

10

Why an Early

Childhood Focus

in Vulnerable

Urban Contexts

With cities worldwide growing

exponentially and global population

displacement on the rise, the coming

decades will see increasing numbers

of children growing up in informal,

resource-restricted, and otherwise

fragile urban settings. In these areas,

the needs of the youngest and

most vulnerable often go unheard

in decisionmaking and planning.

By 2030, cities will contain 60% of

the global population.

18

More than

90% of urban growth through 2035 is

projected to occur in South Asia and

Sub-Saharan Africa. Over this period,

the urban population of both regions

is expected to more than double.

Currently, over 250 million children

in developing countries are at risk

of not attaining their developmental

potential.

19

As the speed of

growth inevitably outpaces that of

planning, the number of children

living in informal settlements

in these regions will increase

signicantly in the coming years.

20

Alongside unprecedented global

urban growth, refugee ows are

projected to increase in the next

decades. Between 2003 and 2018,

the worldwide population of people

forcibly displaced annually due to

persecution or conict rose from

11

3.4 million to 16.2 million. Nearly

half of the world’s 25.4 million

refugees reside in cities.

21

85% of

these displaced people are being

hosted in developing countries.

52% of the global refugee

population are children,

23

and 4.25

million of these refugee children

are under the age of ve.

24

While the typologies of vulnerable

urban contexts can vary, living in

these environments is consistently

demonstrated to have signicant

negative impacts on the optimal

development of very young children,

as well as their support networks.

25

26

These trends of urbanisation

and displacement are occurring

against a backdrop of increasingly

frequent and severe impacts of

climate change. Children will bear

the brunt of these effects, with

those age 0-5 at particular risk.

Investing in early childhood

development has been proven

to be the single most effective

method for poor and vulnerable

societies to break out of poverty

and vulnerability cycles.

27

Every USD$1 invested in high-

quality 0-to-5 early childhood

education for disadvantaged children

delivers a 13% annual return on

investment, signicantly higher

than the 7-10% return delivered by

preschool programmes alone.

Despite these clear benets, only

two percent of global humanitarian

funding is allocated to education;

early childhood development

programmes only account for a

tiny fraction of that amount.

28

Existing early childhood investments

focus mainly on formal educational

facilities, which, due to lack of

resources and a universalistic

approach, tend to underestimate

cultural and contextual differences

and largely disregard learning

opportunities outside the

classroom.

29

Learning occurs both

in and out of the classroom, and

to date little has been done to

capitalise on out-of-school time

and on the benets of the built

environment in child development.

For urban planners, development

actors, and government

authorities alike, there is no

greater chance to reap long-

term, society-wide benets than

by improving early childhood

development for the generations

being raised in vulnerable urban

contexts around the globe.

12

What we mean by

'Vulnerable Urban Contexts'

Vulnerable urban contexts are built

environments subject to ongoing

shocks and stresses which pose a

threat to residents’ lives, livelihoods,

and the maintenance of social,

physical, political and economic

systems.

84

We have identied

two classes of vulnerable urban

context that Arup and BvLF seek

to engage: informal settlements

and refugee settlements.

While each vulnerable urban

context is unique, it is helpful

to identify throughlines

common to these settings.

Settlements in these contexts

tend to be overcrowded, polluted,

and lacking health and safety

measures considered common

elsewhere. Infrastructure in

these areas is often incomplete

or unsafe; poor waste, sewage

and stormwater management

is common, as is a shortage or

absence of green space.

86

Vulnerable urban contexts tend

to have compromised access to

urban services, including WASH,

power and transit infrastructure.

87

The universal urban issues of car

and street safety, crime and violence

are endemic concerns in both

refugee and informal settlements.

In general, conditions in these areas

(corruption, poverty, hopelessness,

resource competition, and

lack of oversight) create fertile

environments for petty and violent

crime, drug trafcking and gang

activity. Type and intensity of

crime and violence depends on

local norms as well as levels of

unemployment and marginalisation.

Finally, vulnerable urban contexts

tend to be particularly exposed

to climate change impacts.

In general, the elements upon

which planners, policymakers

and practitioners from the global

northwest traditionally rely -

hierarchy, predictability, and

control - are often overwhelmed

by the tendency of vulnerable

urban contexts to magnify

and intensify complexity.

13

© Arup

14

In determining broad typologies

of vulnerable urban contexts,

we consider two variables

of a specic settlement:

location and duration.

TYPOLOGIES OF VULNERABLE

URBAN CONTEXTS

Integrated:

Settlements which are directly

enmeshed in the urban fabric. Can

exhibit improved (but not necessarily

high quality) access to urban systems.

Isolated:

Settlements onstructed on the

urban periphery or interstitial

spaces. Isolation generally impairs

access to urban systems.

Established:

In existence for ten years or

longer. Infrastructure and political

relationships in these settlements

have often assumed a settled order.

Recent:

Settlements less than a decade

old, often developed in response to

ongoing crises. Layout, materiality

and population are often in ux.

Location

Refers to the siting of a

settlement's physical footprint

in relation to the nearest urban

area, and can be either:

Duration

Refers to the length of time

a settlement has been in

existence, and can be either:

Mapping a settlement's

age against integration with

urban systems can provide

insight into the type of

vulnerabilities likely to occur.

15

LessVulnerable Integrated

Recent Established

Isolated

XAxis:Duration

YAxis:Location

MoreVulnerable

Diagrammatic layout of vulnerable urban context typology variables

(developed by Arup, 2019)

In general, settlements in

the Established / Integrated

quadrant tend to exhibit lower

vulnerability than those in the

Recent / Isolated category.

This is not a hard and fast

rule; some informal and

refugee settlements sited in

city centres exhibit complex

multi-source vulnerabilities.

Informal settlements are

residential areas of any scale

where residents lack legal tenure.

UN-Habitat describes an informal

settlement as a residential

area whose inhabitants face

three primary deprivations:

1. Inhabitants have no security

of tenure vis-à-vis the land or

dwellings they inhabit, with

modalities ranging from squatting

to informal rental housing.

2. Neighbourhoods usually

lack, or lack access to, basic

services and city infrastructure.

3. Housing may not comply

with planning and building

regulations, and is often

situated in geographically

and environmentally

hazardous areas.

88

This absence of legal tenure and

compromised access to urban

systems affects health and

safety, and exposes residents to

exploitation, eviction, and crime.

Despite these challenges,

migration to informal

settlements is largely due

to pull factor of economic

opportunity, often with

future generations in mind.

“Informal Settlements” vs “Slums”

16

These terms are not interchangeable.

Informal settlement refers to an

absence of legal land tenure, whereas

slum is a qualitative term indicating a

severe lack of basic urban services.

The UN denition of a slum household

89

describes “a group of individuals living

under the same roof lacking one or more

of the following ve conditions:”

INFORMAL

SETTLEMENTS

1. Access to improved water

2. Access to improved sanitation facilities

3. Sufcient living area, not overcrowded

4. Structural quality/durability of dwellings

5. Security of tenure

In many cultures and languages 'slum'

carries a pejorative connotation, and

any use of the term as an intensier

must be dened explicitly.

90

17

© Mihai Andritoiu

18

The settlement’s distance from

the metro centre remains a key

obstacle for residents. Caregivers

must spend hours on trains or in

taxis to reach city jobs; consequently

children are left on their own or

in unregulated daycare facilities

for large stretches of the day.

Safety is a key issue in Khayelitsha.

The settlement has the lowest

police-to-population ratio in the

country, and with few diversions

for young adults, gang activity,

drug trafcking and gun violence

are facts of everyday life.

Khayelitsha was created in the 1950s

as worker housing for Cape Town.

With the advent of free internal

movement in 1994, residents of the

rural Eastern Cape ocked to the

Cape Town area seeking economic

opportunity. Within a decade,

Khayelitsha had quintupled its

planned population and massively

expanded its footprint due to

construction of informal housing

Khayelitsha’s population was

301,000 at the last census in 2011;

since then the settlement may

have reached 700,000+ inhabitants.

© William Newton

ESTABLISHED / ISOLATED

Khayelitsha, South Africa

INFORMAL SETTLEMENT

Founded in the early 1950s in a forest

at the edge of Nairobi, Kibera has since

been entirely enveloped by the city.

Estimates of the current population

range from 300,000 to over 1 million;

the settlement has garnered media

attention due to the (inaccurate)

label of ‘the largest slum in Africa’.

Whatever the real gure of Kibera’s

population, national and regional

authorities do not acknowledge

the settlement’s legality, leaving

the entire population without

access to services or infrastructure

from the surrounding city.

A signcant majority of Kibera’s

population lives without electricty

or an in-home water supply. Due

to minimal sanitation services,

Kibera’s streets are heavily

contaminated with waste. The

severe topography of the area, poor

soil conditions, heavy seasonal

rainfall and proximity to the Nairobi

river combine to result in regular

ooding and structure collapse.

Kibera’s age and size have led to the

rise of robust informal economic

and educational systems.

92

19

© Vlad Karavaev

ESTABLISHED/ INTEGRATED

Kibera, Kenya

INFORMAL SETTLEMENT

Arup and BvLF’s work does not

encompass

planned refugee or internally

displaced persons camps

. Our work

is focused on

settlements

, e.g. urban

spaces where refugees have self-settled,

often after leaving planned camps.

Planned camps are intended as sites

of temporary refuge; management and

layout requirements related to this

intent can conict with those usual

in built environment interventions.

More signicantly, legal and regulatory

structures around planned camps are

delicate balances between humanitarian

organisations, funding bodies and

national governments; engaging

with these structures can indirectly

result in instability or conict.

Principles from our work generalise

well to camp environments, and

practitioners are encouraged to

adapt our ndings where possible.

REFUGEE

SETTLEMENTS

“Refugee Settlements” vs “Refugee Camps”

20

Refugee settlements are urban

areas where refugees self-settle in

unclaimed properties or join pre-

existing informal settlements.

93

These settlements generally arise

in response to armed conict,

political unrest, natural disasters,

resource shortages, or other crises.

Refugee settlements tend to accrete

near national borders, often just

inside countries nearest a given

crisis, or where an economically

vibrant nation with restrictive

immigration laws controls access

from a state with relatively less

economic opportunitiy but fewer

restrictions on movement.

By denition, refugees originate

elsewhere and have migrated under

duress. Whether from another region

or nation, weak ties to the host city

expose refugees to obstacles not

faced by indigenous residents

These obstacles may include

marginalisation, discrimination,

marginal social support

networks, vulnerability to crime,

violence, and exploitation, as

well as issues associated with

lack of documentation.

Migration to refugee settlements is

largely due to push factors of conict-

or climate-related dispossession.

21

© Catalytic Action

Photo courtesy Catalytic Action

©William Isaac Newton

22

© Melih Cevdet Teksen

Established in 2012 as a temporary

camp for refugees from the

Syrian conict, Zaatari is gradually

transitioning into a self-provisioning

urban conglomeration. As of 2019

the site hosts 78,000 refugees, 20%

of whom are under ve years old.

Since 2016, UNHCR has been moving

away from a top-down model of

service provision at the site and

instead providing refugees with

nancial assistance only, intending

that the settlement’s increasingly

robust internal economy and

organic social organisations will

sufce to address the material and

nutritional needs of residents.

Zaatari is a category-leading

example of this type of transition

from planned camp to urban

settlement, a phenomenon likely

to become increasingly widespread

over the next 20 years.

ESTABLISHED / ISOLATED

Zaatari, Jordan

REFUGEE SETTLEMENT

©Sara Candiracci

23

The Bekaa Valley town of Bar Elias

had a population of 50,000 prior

to the Syrian conict; refugee

inux has more than doubled that

number in just under ve years.

While the local guest culture

embraces the newcomers, the

city’s service provision and social

fabric have been overwhelmed

by the sheer number of refugees

seeking shelter and economic

opportunity in the municipality.

Materially, this inux results in

conicts over space: the town

is increasingly ringed by ad-hoc

landlls, and available grave sites

for deceased family have become

a hotly contested commodity.

Socially, this overcrowding results

in economic tension: the massive

labour market for low-end jobs has

signicantly disrupted the city's

established nancial order, leading

to resentment and violence.

ESTABLISHED/ INTEGRATED

Bar Elias, Lebanon

REFUGEE SETTLEMENT

© Catalytic Action

24

The Proximity of Care approach

is at the core of the Design

Guide that Arup and BvLF

are developing to support

government authorities, urban

practitioners, development and

humanitarian organisations

working in vulnerable urban

contexts, to mainstream in their

work the needs of young children,

their caregivers, and pregnant

women, and to prole their work

as child and family friendly.

The Proximity of Care Approach

was developed to better

understand and frame the

relationship between the

built environment and early

childhood development in

vulnerable urban contexts, whose

interdependencies are not always

fully appreciated and addressed.

Proximity of Care describes how

various urban systems relate to a

child’s developmental needs.

This approach provides a

structure to enable holistic

consideration of both hard and

soft assets - physical space

and infrastructure, human

interactions and relationships,

and policy and planning support

- at different urban scales.

The Proximity of

Care Approach

The resulting understanding

of the full spectrum of urban

interactions allows planners,

authorities and built environment

professionals to create a healthy,

stimulating, safe and supportive

environment that contributes

to young children’s optimal

development, and enhances

caregivers’ and pregnant women’s

living conditions and wellbeing.

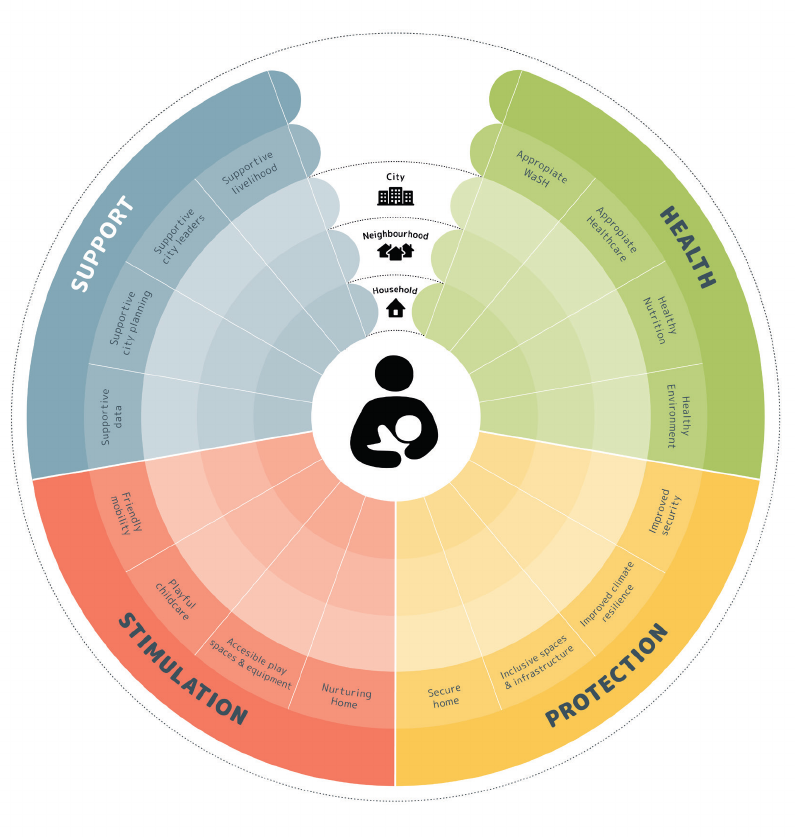

Proximity of Care assesses

four primary Dimensions

foundational to early childhood

development: Health, Protection,

Stimulation and Support.

Within each dimension,

the framework focuses on

beneciaries’ needs at three

primary scales of urban

interaction: the household,

neighbourhood and city levels.

25

© Adriana Mahdalova

26

Dimension: Support

This dimension considers elements

that contribute to a knowledgeable and

supportive environment for optimal

early childhood development, looking

at how to enhance knowledge, support

from city authorities and community

members, and include beneciaries’

voices in decision-making and planning.

Dimension: Health

This dimension considers elements

that contribute to a healthy and

enriching environment for optimal early

childhood development, examining

how to improve physical, mental, and

emotional health and support cognitive

development among young children,

their caregivers, and pregnant women.

Dimension: Stimulation

This dimension considers elements

that contribute to a nurturing and

stimulating environment for optimal

early childhood development,

addressing how to enhance the

quality of children’s interaction with

caregivers, peers, other adults, and

the physical space around them.

Dimension: Protection

This dimension considers elements

that contribute to a safe and secure

environment for optimal early childhood

development, determining how to

reduce risks, mitigate hazards and

increase safety for children, and improve

caregivers’ perception and experience of

safety and security.

PROXIMITY OF CARE:

DIMENSIONS

The Proximity of Care approach

assesses four primary Dimensions

foundational to optimal early

childhood development, focusing

on the Health, Protection,

Stimulation and Support

needs of young children, their

caregivers, and pregnant women

as they move through their

daily lives and routines in a

vulnerable urban context.

Each of these four dimensions

engages four key factor areas,

examining a range of indicators

against benchmarks of ‘what good

looks like’ at three distinct levels

of the urban fabric. This cross-

cutting assessment encourages

a nuanced understanding of

the specic areas most critical

to improving early childhood

development in a given context.

27

Visualisation of the Proximity of Care Approach

28

The Proximity of Care Approach

engages with three key scales

of urban interaction signicant

for children and caregivers

throughout early childhood

development: the Household,

Neighbourhood, and City levels.

These levels are highly context-

dependent. Particularly in

informal and refugee settlements,

denitions of ‘household’ and

‘neighbourhood’ may be mutable,

encompassing single dwellings,

compounds and shared spaces.

Similarly, the ‘city’ level may

depending on context include a

provincial or national dimension,

where policies that impact early

childhood development originate

beyond municipal authority.

To improve early childhood

development in vulnerable

urban contexts, it is necessary

to understand the spatial and

relational specics of each

level by assessing challenges

and opportunities, and to

engage with all three levels

simultaneously for greatest effect.

PROXIMITY OF CARE:

LEVELS

Spaces

Relationships

Description

29

Household

Neighbourhood

City

The Household is where the

child lives and spends the

most time. It is a personal,

intimate, and immediate

space, where a young child

feels condent, can move

freely and likely has the

most support from and

interactions with caregivers.

How children are treated

in the household will

inuence relationships

throughout their life.

The Neighbourhood is

where the child develops

many spatial and relational

skills, interacting with

the community alongside

a caregiver. It is a local,

communal, public space,

accessible from home,

where a child requires

guidance and protection

from adults. This level

includes links between home

and nursery, workplace, and

healthcare, and between

family and community.

The physical space of

the household level

describes the house, at,

shelter or compound, any

associated space such

as a garden or yard, and

immediate street frontage.

Interactions at the

household level are intimate

and ideally reciprocal,

nurturing, supportive

and stimulating for the

young child, involving

parents, siblings, and

extended family.

The physical space of the

neighbourhood includes

play areas, nurseries,

schools, stores, markets,

and places of worship; it

also includes streets, local

transit, and connections

between these spaces.

Interactions at the

neighbourhood level are

social, educational and

commercial, involving

neighbours, friends,

classmates, merchants,

clergy, and other

adults regularly known

to the caregiver.

The City is a distributed,

institutional and

administrative space,

distant from the home and

generally not accessible

by walking, encompassing

both neighbourhoods

and households. This

level includes regulatory

and governance policies

which impact early

childhood development.

Interactions at the city level

are functional, involving

transit and emergency staff,

administrators, politicians

and decision makers.

Young children’s visibility

and consideration as a

group to actors at this level

has key impacts on early

childhood development,

including budgeting.

The physical space of the

city includes local, provincial,

regional or national ofces,

regulatory bodies and

administrative facilities

which the caregiver and

child may visit infrequently,

but which have a key role

in dening the policy and

infrastructure environment

in which early childhood

development occurs.

30

Beneciaries

and their Needs

Children Age 0-3

The ‘rst 1000 days’ from conception

to 24 months is a critical window of

rapid brain development.

32

During this

time, children are extremely physically

and psychologically vulnerable, and

are entirely dependent on adults.

Children Age 3-5

A child’s growing independent

mobility at this age provides a broader

range of stimulating experiences,

but can place strain on caregivers

in terms of safety, supervision, and

transportation.

33

Health care, nutrition

and protection remain important at

this stage, as does the developmental

signicance of relationship-building.

4

The Proximity of Care Approach

considers four key groups living

in vulnerable urban contexts:

+ Children 0-3

+ Children 3-5

+ Caregivers

+ Pregnant Women

Pregnant Women

During the antenatal period, health,

nutrition and protection are essential

for both mother and unborn baby.

35

The physical and psychological health

of the mother, and the support

she receives from her community

are particularly important.

Caregivers

Caregivers are children’s direct

support networks: parents, siblings,

extended family and non-related

carers.

36

Parents, as natural primary

caregivers, are crucial initial

inuences, as they demonstrate

affection, introduce the child to

language, and make the child’s world

safe and interesting to explore.

37

These four beneciary groups

are particularly exposed to and

severely affected by inadequate

basic services, poor living

conditions, limited economic

and educational opportunity,

and lack of representation in

urban policy and planning.

31

31

© Karol Moraes

HOUSEHOLD

32

CHILDREN

AGE 0-3

THROUGH THE

PROXIMITY OF

CARE LENS

Optimal development at age

0-3 is characterized by variety

of stimulation, nurturing

relationships, attachment

to primary caregivers, and

provision of optimal nutrition.

Children at this age should

not, save in exceptional

circumstances, be

separated from their

mother or caregiver.

45

Nurturing, responsive

interactions with caregivers

forge emotional bonds and

are essential for optimal

cognitive development.

Loving, engaged, undistracted

and particularly nonviolent

caregiving helps ensure

positive developmental

outcomes. Absent or

unreliable caregivers

negatively affect

development; coping

strategies developed in

response to caregiver neglect

can severely compromise

children’s later relationships.

Health:

At age 0-3, healthy nutrition is

crucial. Ideally this begins with

exclusive breastfeeding, starting

within the rst hour of the child’s

life and continuing for the rst six

months.

47

After six months, optimal

nutrition (adequate calorie intake,

dietary diversity, and a variety

of macro- and micro-nutrients)

is key for brain development as

well as physical growth.

48

Protection:

Healthcare, including immunization,

disease treatment and prevention,

and regular check-ups, is critical.

Access to WASH facilities should

be considered a necessity.

49

Stimulation:

Rest is as important as stimulation:

infants from 0-3 months of age need

14-17 hours of good quality sleep

including naps; sleep requirements

decline to 12-16 hours from 4-11

months, and 11-14 hours at age 1-2.

50

Support:

Nurturing relationships are of primary

importance and centre around

‘serve-and-return’ interactions,

46

where caregivers engage with a

child’s noise, gesture or expression.

PROXIMITY OF CARE LENS

NEIGHBOURHOOD CITY

33

Health:

Healthcare provision should

be safely accessible from the

home, without physical, social

or nancial barriers to access.

Protection:

Optimally, infants should not be

restrained continuously for more

than an hour at a time. Access

to safe streets for travel with

caregivers is crucial for very young

children, as is regular access

to green space for exploratory

play and exposure to nature.

Stimulation:

At this stage children are totally

reliant on their parents for both

interaction and mobility. Infants

should be physically active

several times a day, particularly

through interactive oor-based

play, the more the better.

Support:

Creches and daycare facilities can ll

a critical gap for working caregivers;

these facilities should be hazard-

free, safely and easily accessible

from the home, and staffed by

trained, qualied, motivated

caregiving professionals. Certication

of both the facility structure and

individual staff members is desirable.

Health:

Programmes intended to improve

early childhood development should

recognise the interdependencies

between security, nutrition,

healthcare, and early learning,

especially for prenatal children

and 0- to 3-year-olds

.

52

Protection:

Births should be registered, either

by authorities, or by humanitarian

and development organisations.

Documentation is key to providing

children with access to the full

range of developmentally necessary

urban assets and services.

53

Stimulation:

Planning and programming of public

spaces and institutions should

recognise the specic physical

needs of caregivers visiting those

spaces with 0-3 year old children.

Support:

Authorities should champion

documentation, healthcare

provision, and daycare availability by

ensuring these services are funded,

regulated and certied, by including

education and awareness of the

necessity and availability of these

services in planning and policy,

and by modelling these offerings

through municipal institutions.

Health:

Proper nutrition remains important

at age 3-5. Through this age span

the developing child should ideally

broaden intake of a variety of fresh,

healthy foods with a wide diversity

of macro- and micr-nutrients.

Protection:

The increasing mobility of children

at this age presents opportunities

for a wider variety of stimulation

but requires that caregivers ensure

the child’s safety with regard to

navigating, handling and ingesting

objects in the home.Reduction

of caregivers’ physical and

environmental stress is of primary

importance; a household environment

that supports the caregivers’ physical

and mental well-being is critical.

Stimulation:

Rest requirements at this age are

10-13 hours of good quality sleep

including naps, with a regular

bedtime and wake-up time.

54

Support:

Well-balanced mental health allows

caregivers to recognize the child’s

needs and respond appropriately.

This includes empathizing with the

young child’s experiences, managing

their own emotions and calibrating

reactions to their child’s dependence.

HOUSEHOLD

34

CHILDREN

AGE 3-5

THROUGH THE

PROXIMITY OF

CARE LENS

Optimal development at this

age is characterized by an

expansion of the number

and complexity of a child’s

relationships with other

children and adults across

a variety of settings.

3

A child at age 3-5 requires

more varied and complex

sources of stimulation

and opportunities for

exploratory play.

Young children experience

the world at a much smaller

scale than other humans

and have far shorter, and

more assistance-dependent,

range of mobility than older

children and adults.

51

Increasing independent

mobility allows access to

new experiences, particularly

dynamic social interactions

with siblings, family and

visitors to the household,

but this greater freedom

of movement raises new

concerns around safety.

PROXIMITY OF CARE LENS

NEIGHBOURHOOD CITY

35

Health:

Children age 3-5 require advocacy

at the highest levels of urban

planning and decisionmaking.

Protection:

The best interests of young

children should lead the design

and implementation of tools and

policy.

62

This can be achieved through

data-driven decision-making that

includes perceptions and opinions

of beneciaries in data collection.

Stimulation:

The limitations of very young

children’s participation in planning

processes are self-evident, but

their inclusion in these processes

(with reasonable adjustments to

account for their age) can help

normalise both interaction with

municipal authorities and an

expectation of civic participation.

Support:

Cultivating an awareness and

enthusiasm for engagement with

civic and planning issues from

the youngest possible age sets

the stage for long-term political

and community awareness,

providing the building blocks for

residents of vulnerable urban

contexts to increase a sense of

ownership, agency and dignity.

Health:

At age 3-5, development focus

shifts to playing and exploring more

independently in neighbourhood

streets and expanding the range of

relationships with peers and adults.

55

Protection:

Mobility challenges are benecial, as

are complex interactions with other

adults and children.

56

Independent

mobility is important to development,

resulting in higher levels of physical

activity, increased sociability, and

improved mental wellbeing, freedom

and dignity,

57

which can also benet

their parents and caregivers.

Stimulation:

Physical exercise and a connection

to the natural world are associated

with a range of physical and mental

health benets, including lower rates

of obesity, depression, stress and

attention disorders.

58

Active forms

of mobility not only encourage

healthier routines, contributing to

reduced childhood obesity, but also

more frequent social interactions.

Support:

ECD programmes help foster

social competency as well as

continued cognitive, emotional and

language development, preparing

a child for success in school.

Health:

Diverse nutrition is a key contributor

to both maternal and foetal health,

as is a supportive, low-stress

environment with adequate exercise

and rest. Pollution and environmental

hazards are a key concern during

pregnancy: toxins can severely impact

foetal birth weight as well as long-

term development of the child.

Protection:

Supportive care during labour is

an oft-overlooked component of

antenatal care. The continuous

presence of a ‘companion of choice’

for emotional and practical support is

proven to shorten labour, reduce the

incidence of emergency C-sections

and lead to better labour outcomes.

75

This companion can be any person

chosen by the pregnant woman: her

spouse or partner, a friend or relative,

a community member or a doula.

76

Support:

Postpartum women should receive

family and social support; family

and friends should be educated

about the symptoms of postpartum

depression and monitor the new

mother’s emotional wellbeing

for three weeks after birth.

HOUSEHOLD

36

PREGNANT

WOMEN

THROUGH THE

PROXIMITY OF

CARE LENS

Early childhood development

can be properly understood

to begin well before

a child is born.

Healthcare is crucial for

pregnant women, who

need easy access to health

services and parental

coaching activities.

Supportive partners (or family

and friends if partners are

absent) are key to improved

pregnancy outcomes, as

are regular prenatal health

check-ups. Pregnant women

should obtain a copy of

their own medical record,

if possible, to improve

continuity and quality of care.

Counselling on birth spacing

and family planning can

have signicant positive

effects on improving

material and emotional

resource availability for both

children and caregivers.

PROXIMITY OF CARE LENS

Health:

Antenatal medical assessment

is a key part of improving

women’s pregnancy experience.

At least four antenatal check-

ups are recommended.

Medical assessments should include

blood testing for anaemia, urine

testing for asymptomatic bacteriuria,

and clinical inquiry into tobacco use,

substance abuse, and the possibility

of intimate partner violence.

79

Protection:

If possible, pregnant women

should have an ultrasound scan

before 24 weeks; this can detect

foetal anomalies and multiple

pregnancies and reduce post-term

pregnancy labour induction.

80

Support:

Counselling and medical visits

should ideally take place at a facility

near the woman’s home, without

physical, social or nancial barriers

to access. Transportation options

to and from assessment visits

should take into account pregnant

women’s pace, size and need for

rest while walking long distances

or standing for prolonged periods.

Health:

Pregnant women need healthy, safe

and supportive environments at

work, at home and access to health

services and parental support.

77

Adequate pre- and post-natal

care,

81

including parental coaching,

is crucial to positive outcomes

and should be included in city

health planning and budgets.

82

Protection:

There is a pressing need for better

health assistance for pregnant

women during delivery at hospitals.

Municipal policy should recognise

the developmental importance of

breastfeeding and support both

time and space for breastfeeding in

municipally-associated institutions

and the design of transit systems,

public buildings, and public spaces.

Support:

Governance tools should aim for a

holistic approach to early childhood

development issues and include

specic legislation, programmes,

budgets, regulatory frameworks and

training.

83

For instance, adequate

parental leave for both parents

should be guaranteed through both

government and employer’s policies.

NEIGHBOURHOOD CITY

37

CAREGIVERS

THROUGH THE

PROXIMITY OF

CARE LENS

All young children need

frequent, warm, responsive

interactions with loving

adults;

63

this requires that

caregivers have sufcient

time and energy to devote

to their charges.

Violence, abuse and neglect

produce high levels of

cortisol, a hormone that

contributes to stress,

limiting neural connectivity

in developing brains.

64

Positive and non-violent

caregiving, where caregivers

are sensitive to an infant’s

signals and respond

appropriately, builds

stable and responsive

relationships. This has long-

term effects on the child’s

cognitive and emotional

development,

65

especially

with regard to language

acquisition and behaviour

HOUSEHOLD

PROXIMITY OF CARE LENS

38

Health:

The relationship between child and

caregiver is a mutually reinforcing

cycle. Providing adequate support for

physical wellness, mental health and

reducing stress for caregivers results

in more affectionate, interactive,

and consistent care for the child.

Protection:

Use of positive discipline builds

quality of communication,

understanding, and trust between

caregiver and child, with positive long-

term impacts on brain development

and social interactions.

66

Caregivers should provide consistent,

engaged feedback to the child, and

absolutely never use physical violence

against a child in any situation.

Support:

City policy and neighbourhood

awareness are critical to providing

the economic, nutritional and

safety underpinnings of a secure

home life for children at the

upper end of this age bracket.

NEIGHBOURHOOD CITY

39

Health:

Parents and caregivers’ mental

wellbeing and condence in their

ability to support and provide for a

child measurably improves young

children’s development.

67

Ensuring

that caregivers’ daily routines run

smoothly, and that they have the

support of community networks,

has a signicant impact on mental

health and facilitates positive

interactions with children.

68

Protection:

Play and green public areas are key

for young children’s stimulation and

development. Properly implemented,

child-friendly spaces increase

caregivers’ perception of safety,

reducing stress and allowing more

outdoor play time for children,

and more socialisation between

neighbours.

71

Improving parents’

and caregivers’ perception of safety

can foster freer play and contribute

to reducing caregiver stress.

72

Support:

Places for children are also places

for adults, hence they should be

designed for young children, their

caregivers, and pregnant mothers.

Any place where children linger with

caregivers can be a place of learning,

from a supermarket to a bus stop.

73

Health:

Caregivers and pregnant women

should be involved in planning and

policy design through community

outreach, ethnographic research

and co-design initiatives.

Protection:

The developmental importance

of parental leave for both parents

(or caregivers if not biological

parents) should be understood

at the municipal level and

supported through policy, planning

and nancial incentives.

Municipal policy can incentivise

corporations operating in the city

to provide support and wellbeing

services to employees; city leadership

can take a championship role in this

by ensuring city institutions model

parental leave and support policy.

Support:

Optimal, holistic early childhood

development hinges on caregivers’

knowledge and awareness.

Communication campaigns and

public education to ensure that

parents and caregivers possess

a knowledge of the full range of

care practices (health, nutrition,

hygiene and stimulation) is critical.

HOUSEHOLD

40

General challenges

at the household level:

Pollutant exposure tends to be higher

in informal settlements. Cramped

living arrangements affect physical and

psychological wellbeing

.95

Overcrowding in the home can

cause withdrawal mechanisms in

young children, as their developing

brains attempt to cope with

noise and lack of privacy.

96

Informal housing is typied

by improvised structures,

exposed to weather and climate

impacts, often without waste

and water management.

94

Residents can be severely affected by

temperature extremes; coping with

heat or cold increases physiological

stress and can have critical health

impacts for young children

Many adult residents of informal

settlements can only access informal,

unstable and often illegal jobs. Parents

without stable employment often have

difculty providing sufcient healthy

food for young children, in addition to

experiencing increased caregiver stress.

INFORMAL

SETTLEMENTS

THROUGH THE

PROXIMITY OF

CARE LENS

Informal settlements present

a number of common

challenges to early childhood

development at each level of

the Proximity of Care scale.

PROXIMITY OF CARE LENS

NEIGHBOURHOOD CITY

41

General challenges

at the neighbourhood level:

Informal settlements tend to suffer

from minimal WASH provision,

substandard roads, poor electrical

availability, and an absence of

green, public and play areas.

Reduced opportunity, corrupt

or under-resourced policing,

and resource competition can

lead to crime and substance

abuse.

100

These activities cause

violence and insecurity, with

impacts on young children’s daily

freedom and physical safety.

The trauma of living in an area where

violence is prevalent can impede

proper neural development and

lead to coping behaviours such

as aggression or withdrawal.

Informal settlements are often

sited in environmentally hazardous

areas, exposed to impacts of climate

change, natural and manmade

disasters.

98

Droughts can mean long,

stressful journeys to secure daily

water needs; poor drainage provision

can mean severe ood risk and

exposure to waterborne pathogens

General challenges

at the city level:

Participation in interventions may

be seen as dangerous due to risk

of visibility to authority. Eviction

is a constant threat, particularly

in newer informal settlements

sited on developable land.

101

Data collection is a key issue in

informal settlements. The speed with

which informal spaces are adapted

and inhabited often outpaces ofcial

census or survey assessments;

uid physical boundaries and

constant population ux can further

complicate accurate recordkeeping.

Datasets must be collected in an

apolitical and agnostic manner;

accurate mapping and categorizing

of informal settlements’ structures

and populations is essential

for adequate, and adequately

apportioned, service delivery

Informal settlements tend to have

complex relationships with local

and even national authorities.

Ofcials may view informal

settlements as less deserving of

policing and service provision or

may simply refuse to acknowledge

a settlement’s existence.

HOUSEHOLD

42

General challenges

at the household level:

Regardless of material living

conditions, the stress of transition

for refugees is universally severe.

Prolonged displacement of

refugee children from their homes

introduces a variety of traumas,

any one of which would be

sufcient to cause toxic stress.

Refugee families will likely have

encountered military or ethnic

violence, some degree of privation

or malnutrition, and exposure to

natural hazards, crime and abuse

along their relocation journey

Displacement reduces caregivers’

individual agency and opportunity

to provide income, adding to stress

and contributing to destructive

coping behaviours among adults,

including domestic violence.

107

The combined strains of migration

impose an overhead on mental

bandwidth that measurably

reduces parenting capacity

and caregivers' emotional

engagement, intensifying cumulative

developmental risk for children.

REFUGEE

SETTLEMENTS

THROUGH THE

PROXIMITY OF

CARE LENS

Refugee settlements present

a number of common

challenges to early childhood

development at each level of

the Proximity of Care scale.

PROXIMITY OF CARE LENS

43

General challenges

at the neighbourhood level:

The neighbourhood level can

be a place of social tension

in refugee settlements.

Refugee populations can place

pressure on local services already

struggling to meet the needs of

the urban poor.

108

Refugees often

nd themselves in conict with

local communities over resources,

land, or religious differences.

These conicts cause insecurity

for both young children and

caregivers, compromising freedom

of movement and social integration.

The most vulnerable populations

(unaccompanied and separated

minors, single-parent families

and child-led households) are at

particular risk from the threats

of vulnerable urban contexts,

including theft, street violence,

and sexual and physical abuse.

110

Refugees face the additional threat

of detention and deportation,

especially when host country

policy excludes them from

the ofcial labour market.

111

General challenges

at the city level:

While city authorities may

welcome refugees, national host

government policies are generally

becoming more restrictive in

countries of rst asylum globally.

Host governments are crucially

important in providing early

childhood care. In many countries,

responsibilities for provision of this

care is delegated to local municipal

government, where budgets may

not be adequate to the task.

Refugees often devise organic

solutions to issues which in more

established contexts would be

handled by municipal authorities:

these include the development

of informal social protection

networks, self-funded revolving

loan groups, and community-

generated schools and clinics

Birth registration is a critical issue

for children born in urban refugee

settlements.

114

Complicated or

costly administrative registration

procedures, coupled with insufcient

awareness among expectant

mothers of the importance of

registration, leads to undocumented

children. Lack of birth registration

can have lifelong consequences.

NEIGHBOURHOOD CITY

44

Recommendations:

Household Level

Young children living in

vulnerable urban contexts

face a complex set of

challenges and cumulative

developmental risk.

116

For children, exposure to physical

and health threats, poor WASH

facilities, nutrition, service access,

and caregiver stress are among

the most signicant challenges.

A single stressor (overcrowded

dwellings, unsafe surroundings,

or chronic noise) has a xed

detrimental effect on early

childhood development, but

the additive effects of multiple

stressors (chronically noisy,

overcrowded dwellings in unsafe

surroundings) scale exponentially.

These compounding stressors, and

the resulting onset of toxic stress,

are what place young children in

vulnerable urban contexts at such an

extreme developmental disadvantage.

45

Every opportunity to reduce

caregiver stress is a chance

to indirectly improve early

childhood development.

Safety and security, economic

opportunity, and free time are all

constrained resources for caregivers

in vulnerable urban contexts.

Freeing up these resources leads

to more engaged caregiving;

more engaged caregiving

leads to thriving children.

Children’s spaces need

to be safe, peaceful,

healthy and stimulating.

Protection from violence,

particularly domestic abuse,

is an absolute need for early

childhood development. Young

children need proper nutrition and

sanitation as a bare minimum.

Reduction of chronic noise and

sensory disruption is as important

as health and hygiene. Beyond

these minimum standards, children

need street and playspace designs

that support stimulating play.

Nonviolent, nurturing

and engaged cognitive

and socio-emotional

caregiving is a critical

need, not a nice-to-have.

Telling stories to, playing with,

and singing to a young child, and

responding to ‘serve-and-return’

interactions are neither universally

instinctual nor superuous.

These interactions are as crucial to

thriving development as are safety,

nutrition and physical health. Ensuring

that these behaviours are treated

seriously by designers, planners

and city authorities as grounds

for both physical interventions

and caregiver education is a key

component of ECD support.

46

Local knowledge is

critically important for

successful early chldhood

development initiatives.

The complexity of vulnerable urban

contexts’ relationship with the

surrounding urban area often spurs

the development of local solutions to

issues that in other situations might

be dealt with by municipal authorities.

Understanding the evolution of these

workarounds and adapting them

to support external interventions

can help make the difference

between a merely well-intentioned

project and a successful one.

Absent ofcial engagement,

community structures and leadership

are key gatekeepers and allies in

developing interventions. Where

ofcial engagement can be relied

upon, community structures and

leadership are key facilitators and

can help ensure community buy-in.

Recommendations:

Neighbourhood Level

47

Lack of agency is corrosive

to people and communities;

dignity should be a core

value in any intervention.

Feelings of personal helplessness

are a signicant source of stress and

contribute to cycles of addiction and

abuse. If this feeling permeates a

community, it can dissolve the social

bonds upon which safe, healthy,

vibrant neighbourhoods depends

Restoring a sense of agency

and dignity to residents of

vulnerable urban contexts is

critical to delivering change.

Decision-making creates a

durable sense of ownership.

While any development project must

be approached from in both the top

down (permitting, buy-in, safety)

and bottom up (local knowledge

and perspective), pushing decision-

making as far down the chain of

authority as possible can empower

vulnerable communities, providing a

sense of ownership which can help

initiatives succeed over the long term.

Interventions in vulnerable

urban contexts should

benet the surrounding

community as well as

targeted populations, and

these benets should be

clearly communicated.

Singling out vulnerable areas, or

inhabitant groups specic to those

areas, for intervention projects can

generate ill-will from surrounding

urban communities and risks stoking

sectarian, tribal or political conict.

Ensuring that both the messaging

and implementation of interventions

highlight benets to the broader

urban community at large

can defuse resentment.

Each intervention should be

treated as an opportunity to

create dialogue and build rapport

between residents of vulnerable

urban areas and members of

surrounding communities.

48

Recommendations:

City Level

Understanding the history

and nature of an area’s

relationship to authority is

key to effective interventions.

Relationships between vulnerable

communities and authority are

often complex. Ofcial stances

towards informal settlements vary:

an area that in one city presents an

opportunity to burnish municipal

credentials via upgrading may in

another city be considered an

eyesore under threat of eviction.

Careful assessment of local

political relationships is key to

developing successful approaches.

Life-course economic

analysis can shi

stakeholder perceptions.

Children’s issues naturally encourage

adult decision-makers to take a

long-term view. Public expenditures

compounding over the lifetime of a

developmentally compromised child

can be substantial; the cumulative

social efciencies of improving early

childhood development should be

quantied for stakeholders.

49

Pregnant women’s needs are

a powerful case-building tool.

While children’s needs often fall

‘below the radar’ of municipal or

regional authorities, pregnant women

are generally afforded respect and

compassion across cultures and

societies; their position as adults with

agency allows their needs to be ‘taken

seriously’ by authority structures in

a way often unavailable to children.

Built environment affordances for

pregnant women -- including reduced

exposure to pollution, material

protection from environmental and

human hazards, and rest areas

incorporated into public spaces

and transit systems – generalize

well to the needs of young children.

Pregnant women can be thought

of as ‘needs ambassadors’ when

interacting with local, regional or

national ofcials with regard to

interventions in a vulnerable context.

Nuanced, accurate data

is critical for addressing

complex ECD challenges.

A lack of regularly updated, nuanced

datasets is common in vulnerable

urban contexts. Municipal or

national data collection is often

infrequent, incomplete or affected

by political considerations, down to

the level of basic demographics.

Where data is current, population

averages can blur subgroup inequities

that affect conditions in vulnerable

urban contexts. The number of

overlapping challenges to healthy

early childhood development in these

areas can be overwhelming; starting

with data-gathering and constantly

challenging assumptions can help

nd effective, efcient solutions.

50

The Proximity of Care Approach

will be eld-tested in collaboration

with project partners in four pilot

sites, each featuring a distinct

vulnerable urban context:

• The informal settlement of

Khayelitsha in Cape Town, South

Africa, in collaboration with

Violence Prevention through

Urban Upgrading (VPUU).

• The informal settlement of

Kibera in Nairobi, Kenya, in

collaboration with Konkuey

Design Initiative (KDI).

• The refugee neighbourhood

of El Mina in Tripoli,

Lebanon, in collaboration

with Catalytic Action.

• The refugee settlement of Azraq

in Mafraq Governate, Jordan,

in collaboration with Civic.

What’s Next?

Data gathered through our eld

research at these pilot sites will

support development of the

Proximity of Care Design Guide,

a modular toolkit for government

authorities, development and

humanitarian organisations, and

urban practitioners working in

vulnerable urban contexts.

The Design Guide will provide

robust, user-friendly, context-

sensitive design principles, tools,

and policy recommendations to help

design meaningful interventions

that overcome barriers and

address unmet needs of the target

beneciaries -- ultimately helping

to build inclusive, liveable, safe and

climate-resilient urban settlements

where young children can thrive.

The Design Guide will be

nalised in October 2020.

51

© Civic

52

Beneciaries

The intended beneciaries of the

Design Guide are children from 0-5

years old, their caregivers, and pregnant

women. While these groups form

the focus of our efforts, the Guide is

expected to deliver benets to the

wider community in vulnerable urban

settlements where interventions

described in this document take place.

Built Environment

The physical and functional

characteristics of an urban settlements,

including buildings, infrastructure ( blue,

green and grey ) and open spaces.

Context

The characteristics (physical,

environmental, cultural, socio-economic,

historical and governance) that constitute

the setting where the project takes

place. This project addresses vulnerable

urban contexts, such as informal

settlements and refugee areas

Early Childhood Development (ECD)

The physical, cognitive, linguistic, and

socio-emotional development of children

from the prenatal stage up to age ve, a

developmental period during which many

adult capabilities and characteristics are

shaped.

Denitions

Informal Selements

Residential areas that by at least one

criterion fall outside ofcial rules and

regulations. This document adopts

the UN-Habitat denition of informal

settlements

117

as residential areas

facing three primary deprivations:

1. Inhabitants have no security of tenure

vis-à-vis the land or dwellings they

inhabit, with modalities ranging from

squatting to informal rental housing

2. Neighbourhoods usually lack,

or lack access to basic services

and city infrastructure

3. Housing may not comply with current

planning and building regulations and

is often situated in geographically and

environmentally hazardous areas

Mental Bandwidth

A colloquial term for cognitive function

capacity, humans’ xed amount of

cognitive resources available for

processing complex tasks. The cognitive

overhead imposed by poverty, prolonged

stress or material vulnerability can

measurably and lastingly impair

decision-making performance, focus,

attention span, and uid intelligence.

Cognitive capacity can be reduced by

circumstance or environment even when

biological markers of stress are absent.

53

Refugee Selements

Urban areas where refugees self-settle,

either in unclaimed properties or in pre-

existing informal settlements.

118

Refugee

settlements generally arise in response to