BASIN MANAGEMENT ACTION PLAN

for the Implementation of Total Maximum Daily Loads for Fecal

Coliform Adopted by the Florida Department of Environmental

Protection

in

Bayou Chico

(Pensacola Basin)

Developed in consultation with

Bayou Chico BMAP Technical and Local Stakeholders

and the

Florida Department of Environmental Protection

Division of Environmental Assessment and Restoration

Bureau of Watershed Restoration

Tallahassee, FL 32399

August 2011

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The Bayou Chico Watershed Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) was

prepared as part of a statewide watershed management approach to restore and protect

Florida’s water quality. It was developed by local stakeholders, with participation from

affected local, regional, state, and federal governmental and private interests, and in

cooperation with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. FDEP especially

recognizes and appreciates the efforts of all of our participants and local stakeholder groups,

and particularly wish to recognize the following contributors to the Bayou Chico BMAP:

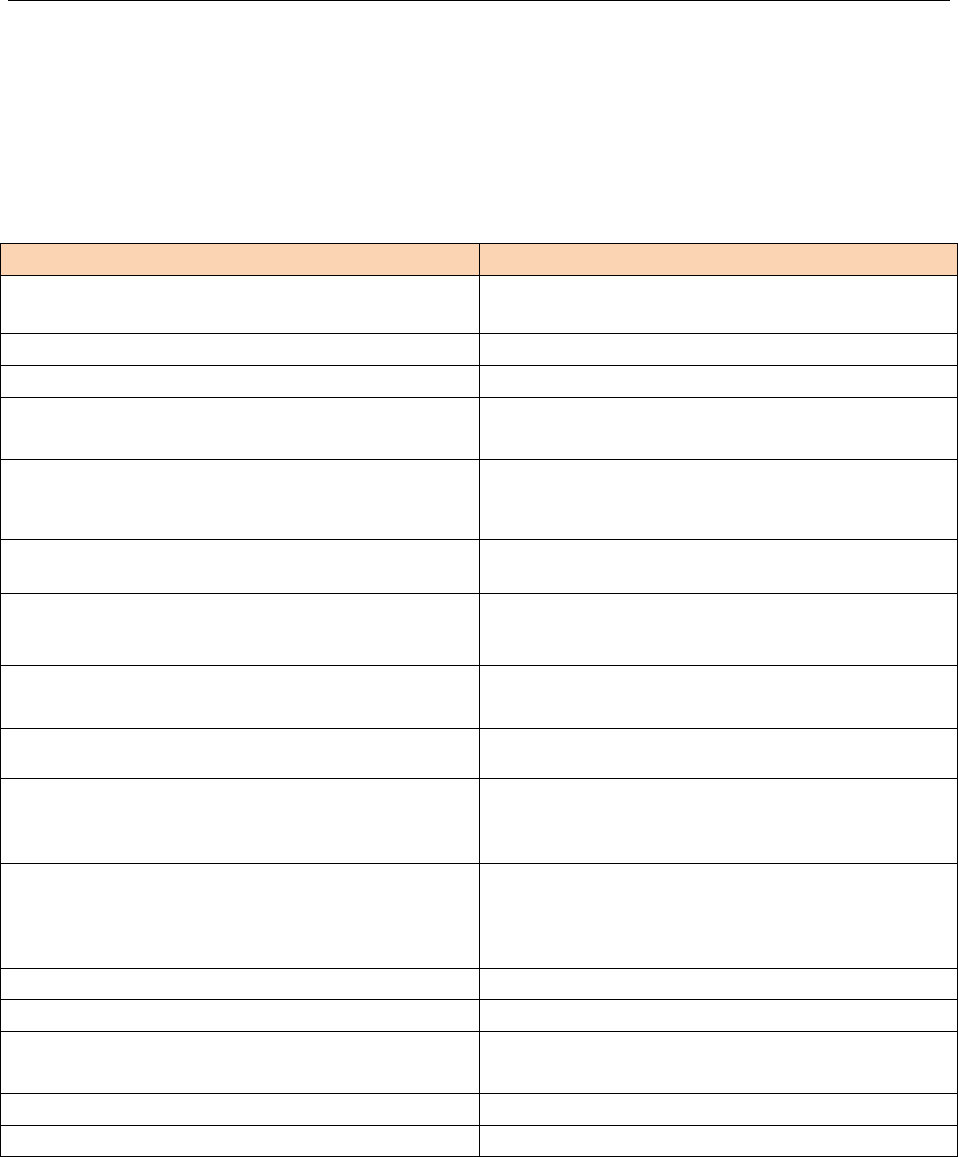

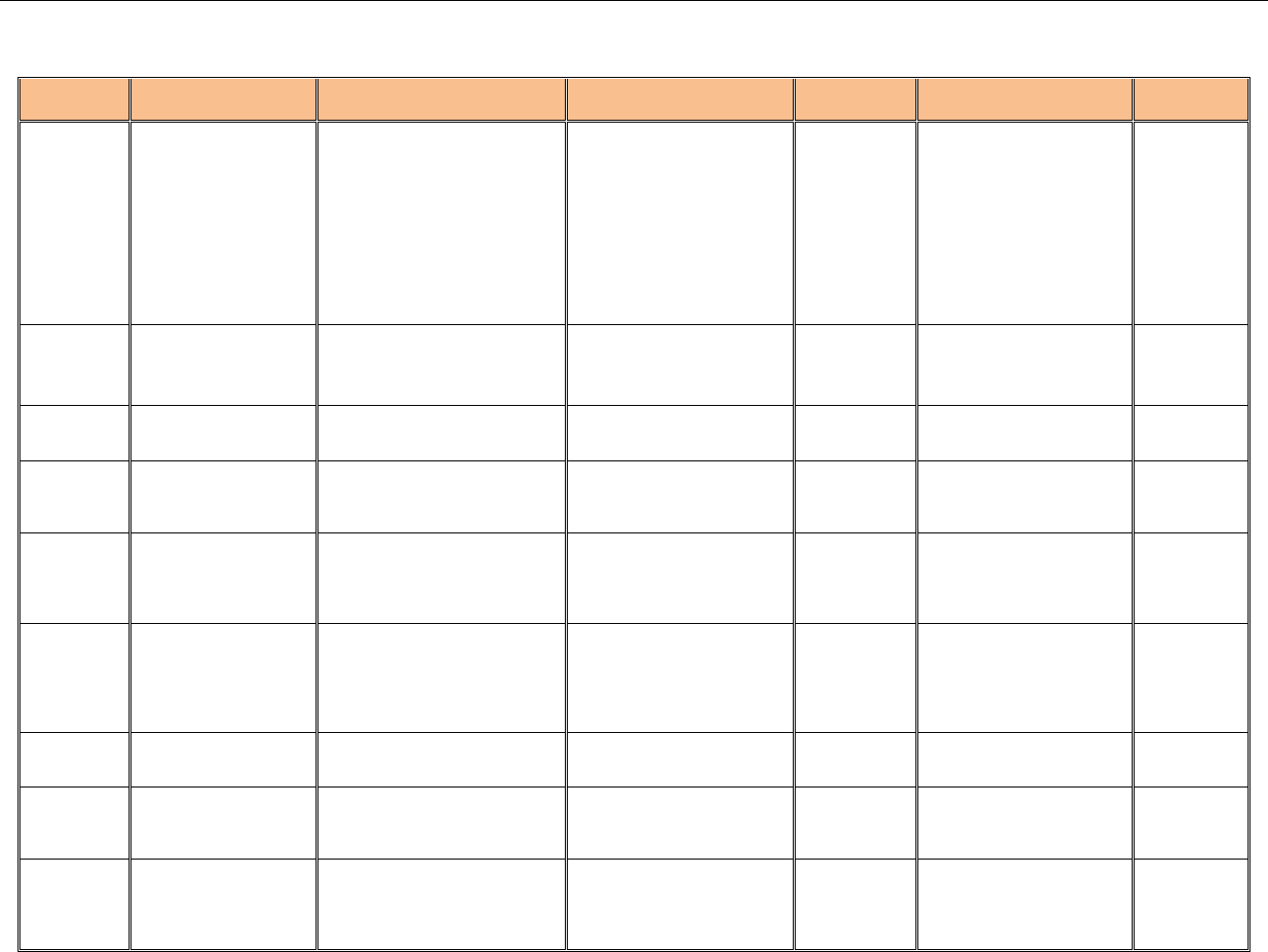

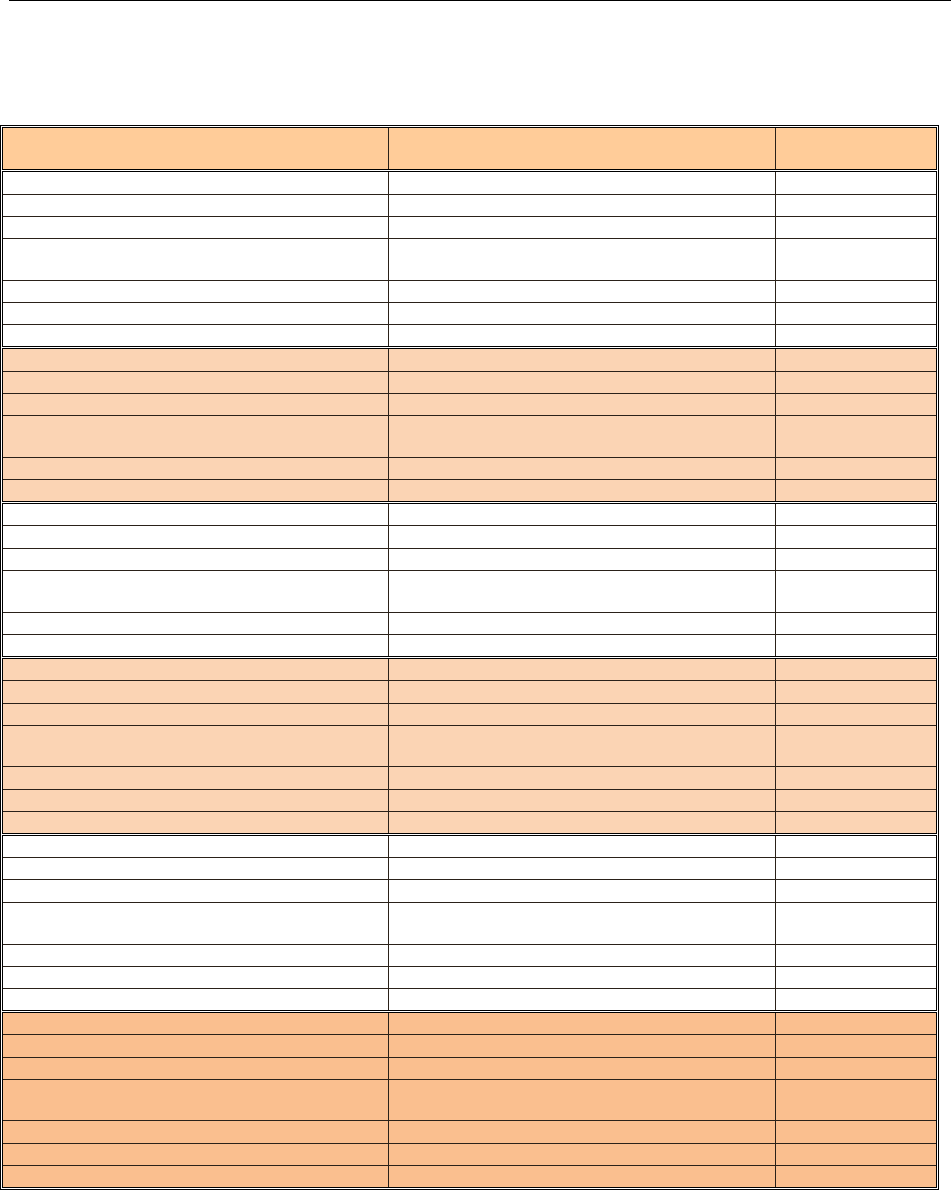

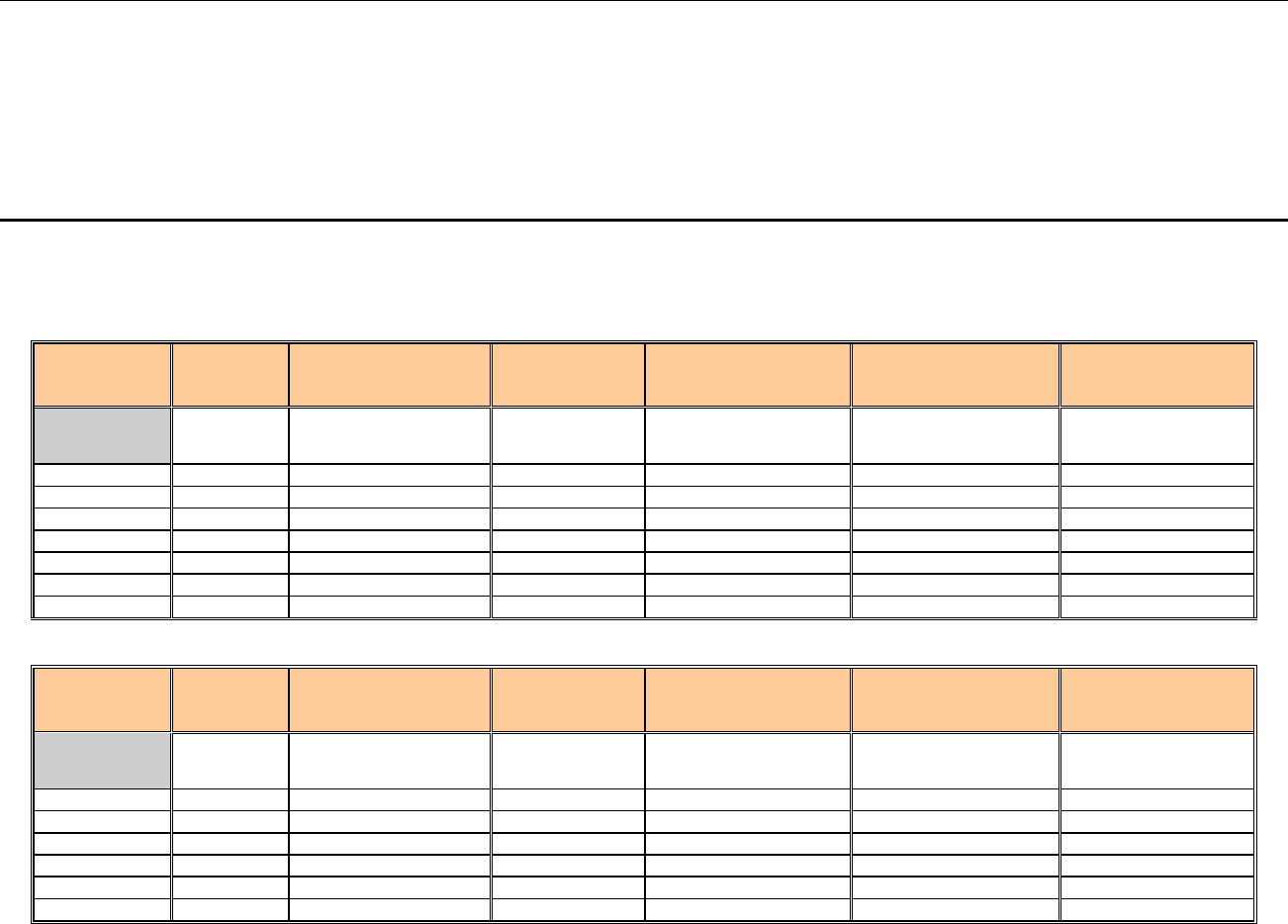

ENTITY/STAKEHOLDER PARTICIP ANT(S)

Bay Area Resource Council, in conjunction with the West

Florida Regional Planning Council

Mary Gutierrez

Bayou Chico Association John Naybor

City of Pensacola Al Garza and L. Derrik Owens

Emerald Coast Utility Authority

Tim Haag, John M. Seymour, Stephen P. Holcomb,

and Wade Wilson

Escambia County

Taylor Kirschenfeld, Brent Wipf, Sava Varazo,

Joy Blackmon, T. Lloyd Kerr, Robert Turpin, Jeri Folse,

and Erin Percifull

Escambia County Health Department –

Florida Department of Health

Robert Merritt, Philip Davies, and Louviminda Donado

Florida Department of Environmental Protection –

Northwest District

Shawn Hamilton (Director), Dick Fancher,

Bradley Hartshorn, Mike King, Cheryl Bunch,

Jennifer Claypool, Jonathon Colmer, and Dan Stripling

Florida Department of Environmental Protection –

Tallahassee

John Abendroth, Bonita Gorham, Linda Lord, Kimberly

Jackson, and Yesenia Escribano

Florida Department of Transportation, District 3

James “Jim” Kapinos, Joy Giddens, and

Lonnie “DJ” Barber

Facilitators and Technical Support:

Science Application International Corporation (SAIC)

Wildwood Consulting, Inc.

Kathleen Harrigan and Robert Kelly

Marcy Policastro

Other key local interest groups and private citizens and

consultants

Larry Buxton, Alexander Maestre, Barbara Albrecht,

Eleanor Godwin, Ken Davis, William DeBusk,

Chris Knight (Florida Department of Agriculture and

Consumer Services), Janet Hearn, Ann Shortell,

Steve Freeman, Amy Tracy, Erin Cox, and Rick Higdon

Northwest Florida Water Management District Ron Bartel

Pensacola Yacht Club Sam Foreman, Alan McMillan, and Vicki Fletcher

University of West Florida, Center for Environmental

Diagnostics and Bioremediation

Dr. Richard Snyder and Dr. Carl Mohrherr

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Michael Lewis and Franklin Baker

U.S. Navy (Naval Air Station) Mark Gibson

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

iii

For additional information on the Basin Management Action Plan in the Bayou Chico

watershed, contact:

Bonita Gorham, Basin Coordinator

Florida Department of Environmental Protection

Bureau of Watershed Restoration, Watershed Planning and Coordination Section

2600 Blair Stone Road, Mail Station 3565

Tallahassee, FL 32399-2400

Email:

Bonita.Gorham@dep.state.fl.us

Phone: (850) 245–8513

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

iv

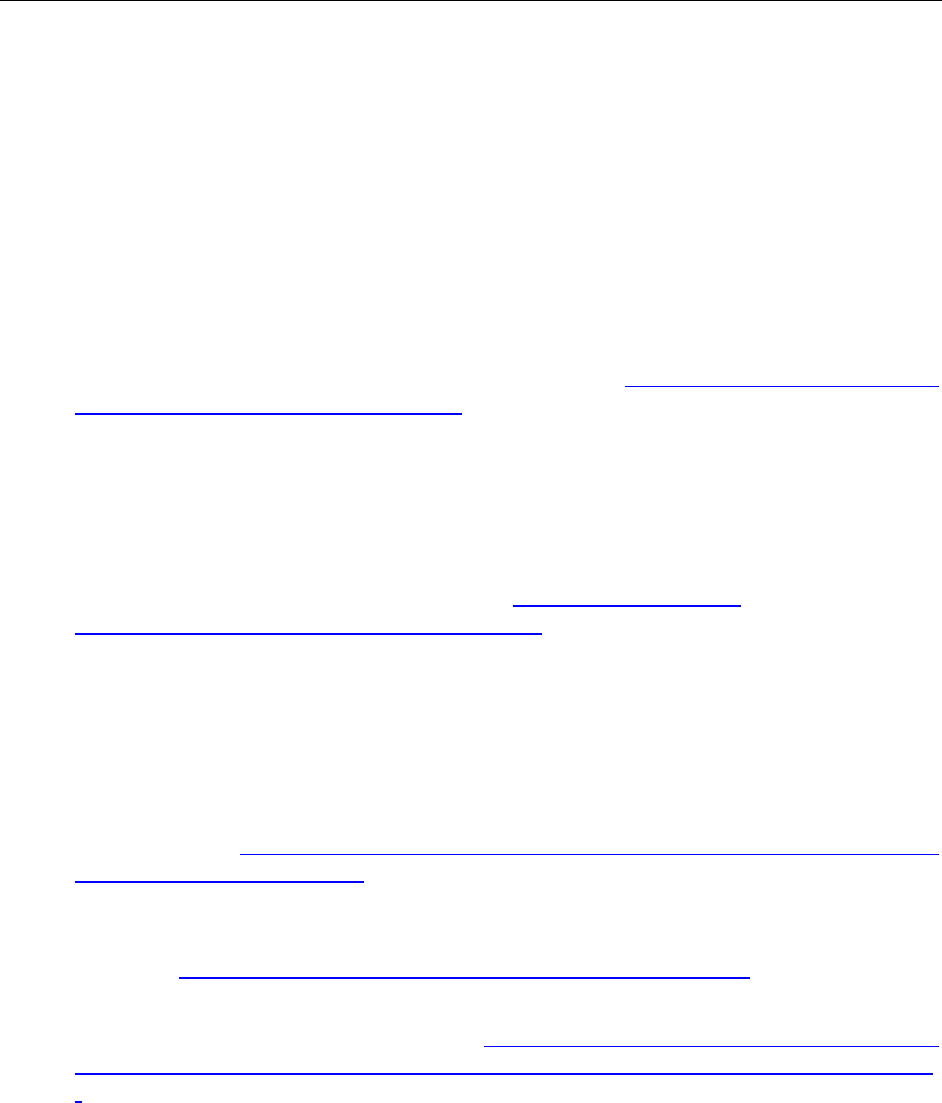

TABLE OF CONTENTS

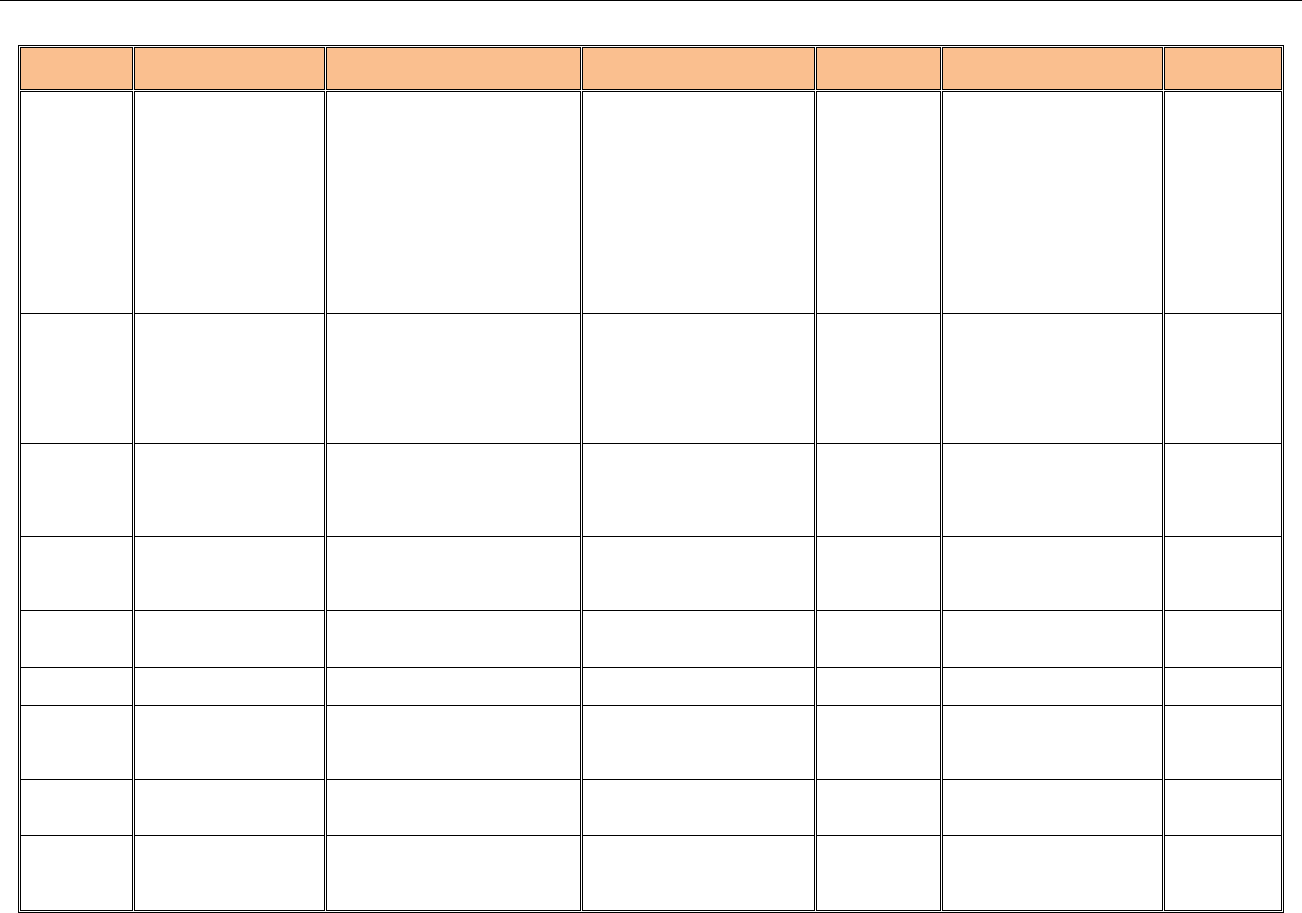

LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS............................................................. VII

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... X

SECTION 1: CONTEXT, PURPOSE, AND SCOPE OF THE PLAN ............................... 1

1.1 Water Quality Standards and Total Maximum Daily Loads .......................... 1

1.2 TMDL Implementation ........................................................................................... 4

1.3 The Bayou Chico BMAP ......................................................................................... 5

1.3.1 Stakeholder Involvement .................................................................................................... 5

1.3.2 Plan Purpose and Approach ................................................................................................ 6

1.3.3 Plan Scope .............................................................................................................................. 7

1.3.4 Sufficiency-of-Effort Determinations ............................................................................... 9

1.3.5 Pollutant Reduction and Discharge Allocations ........................................................... 12

1.3.5.1 Categories for Rule Allocations.................................................................. 12

1.3.5.2 Initial and Detailed Allocations ................................................................. 12

1.3.5.3 Bayou Chico Watershed Fecal Coliform TMDL ........................................ 13

1.3.5.4 Background and Pollutant Considerations in Bayou Chico ...................... 13

1.4 Assumptions and Considerations Regarding TMDL Implementation .......... 15

1.4.1 Assumptions ........................................................................................................................ 15

1.4.2 Considerations ..................................................................................................................... 16

1.5 Future Growth in the Watershed ......................................................................... 17

SECTION 2: POLLUTANT SOURCES AND ANTICIPATED OUTCOMES .............. 18

2.1 Fecal Coliform Pollutant Sources ....................................................................... 18

2.1.1 Sanitary Sewer Systems ..................................................................................................... 18

2.1.2 OSTDS .............................................................................................................................. 19

2.1.3 Stormwater ........................................................................................................................... 19

2.1.4 Marina Activities ................................................................................................................. 20

2.1.5 Wildlife .............................................................................................................................. 21

2.2 Water Quality Trends in the Watershed ............................................................ 21

2.3 Anticipated Outcomes .......................................................................................... 22

SECTION 3: SANITARY SEWER SYSTEMS ..................................................................... 24

3.1 Potential Sources ................................................................................................... 24

3.2 Projects To Reduce Fecal Coliform Loading ..................................................... 24

SECTION 4: ONSITE SEWAGE TREATMENT AND DISPOSAL SYSTEMS ........... 32

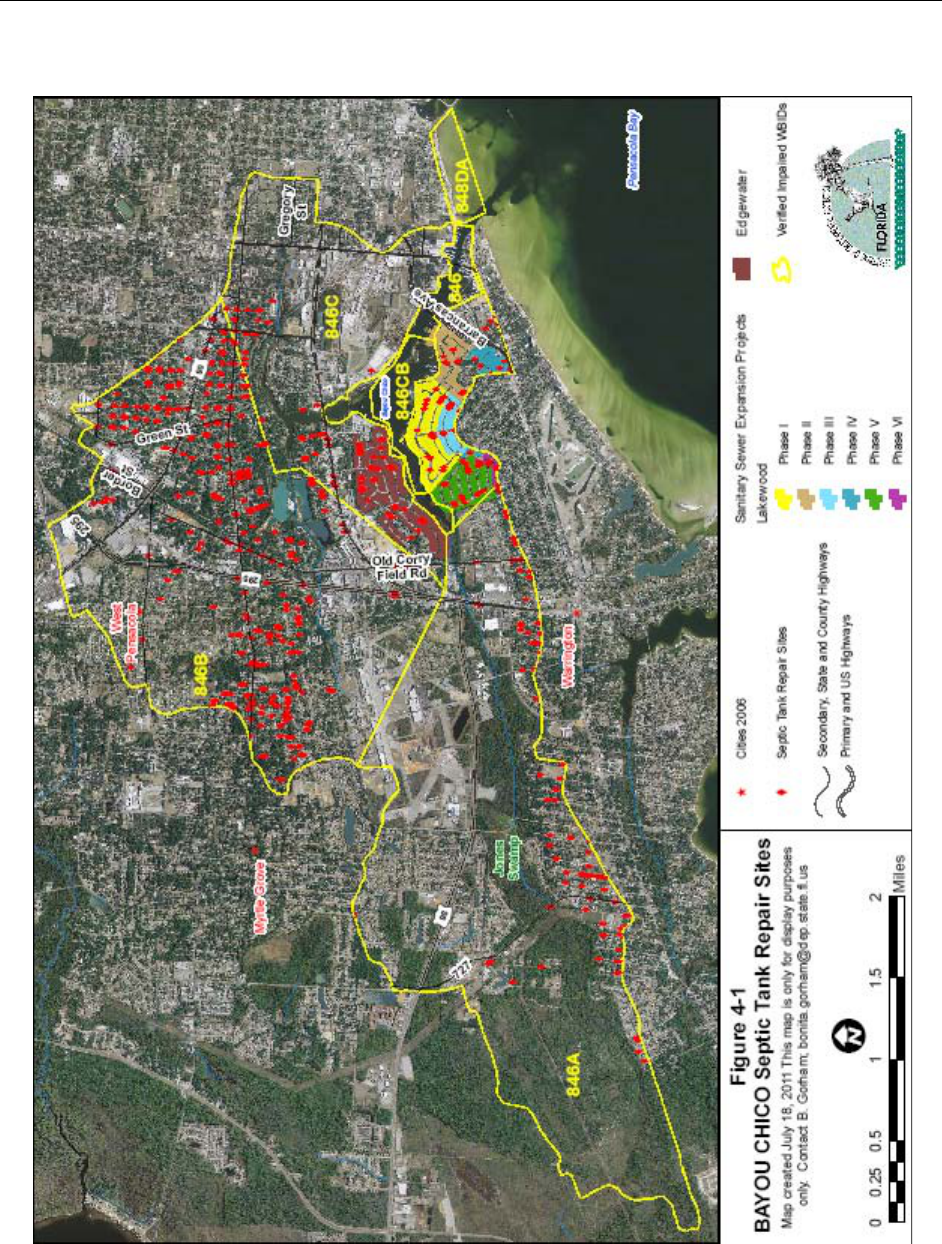

4.1 Potential Sources ................................................................................................... 32

4.2 Projects To Reduce Fecal Coliform Loading ..................................................... 34

SECTION 5: STORMWATER ............................................................................................... 40

5.1 Potential Sources ................................................................................................... 40

5.2 Projects To Reduce Fecal Coliform Loading ..................................................... 40

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

v

SECTION 6: MARINAS, BOATYARDS, AND MOORINGS ........................................ 49

6.1 Potential Sources ................................................................................................... 49

6.2 Projects To Reduce Fecal Coliform Loading ..................................................... 49

SECTION 7: SUMMARY OF RESTORATION ACTIVITIES AND

SUFFICIENCY OF EFFORT ........................................................................................ 53

SECTION 8: ASSESSING PROGRESS AND MAKING CHANGES ........................... 57

8.1 Tracking Implementation ..................................................................................... 57

8.2 Water Quality Monitoring ................................................................................... 58

8.2.1 Water Quality Monitoring Objectives ............................................................................ 58

8.2.2 Water Quality Indicators ................................................................................................... 58

8.2.3 Monitoring Network .......................................................................................................... 59

8.2.4 Quality Assurance/Quality Control ................................................................................. 60

8.2.5 Data Management and Assessment ................................................................................. 60

8.3 Adaptive Management Measures ........................................................................ 61

APPENDICES ............................................................................................................................ 62

Appendix A: TMDL Basin Rotation Schedule .......................................................... 63

Appendix B: Summary of Statutory Provisions Guiding BMAP

Development and Implementation .................................................................. 64

Appendix C: Summary of EPA-Recommended Elements of a

Comprehensive Watershed Plan ...................................................................... 67

Appendix D: Programs To Achieve the TMDL ......................................................... 71

Appendix E: BMAP Annual Reporting Form ............................................................ 81

Appendix F: Minutes from Technical Meetings with Stakeholders ...................... 83

Appendix G: Glossary of Terms .................................................................................. 84

Appendix H: Bibliography of Key References and Websites .................................. 89

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

vi

LIST OF FIGURES

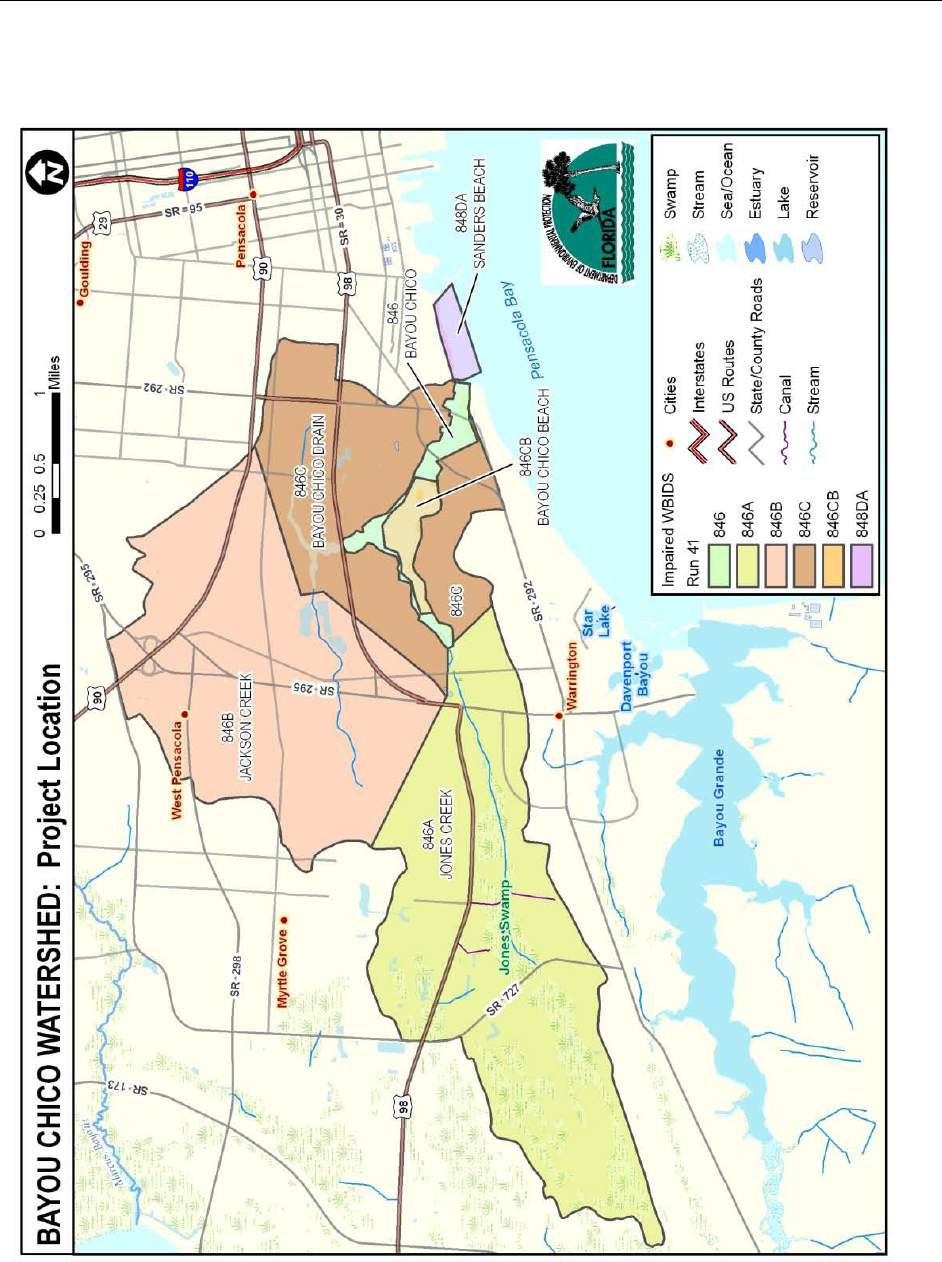

Figure 1-1: Bayou Chico Watershed Location Map ............................................................................. 3

Figure 2-1: Long-Term Monitoring Stations in the Bayou Chico Watershed ................................ 23

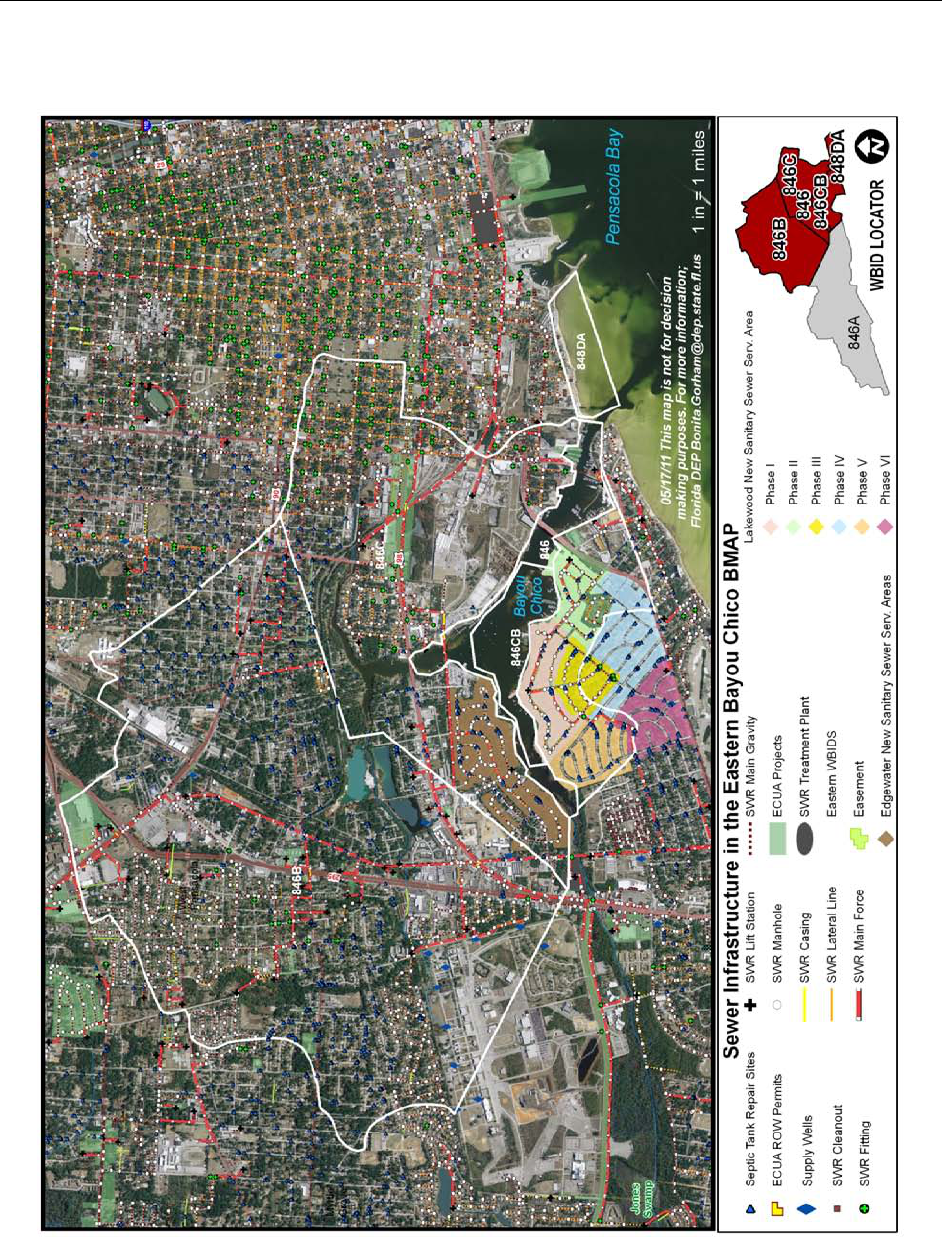

Figure 3-1: Sewer Infrastructure in the Eastern Bayou Chico Watershed ...................................... 25

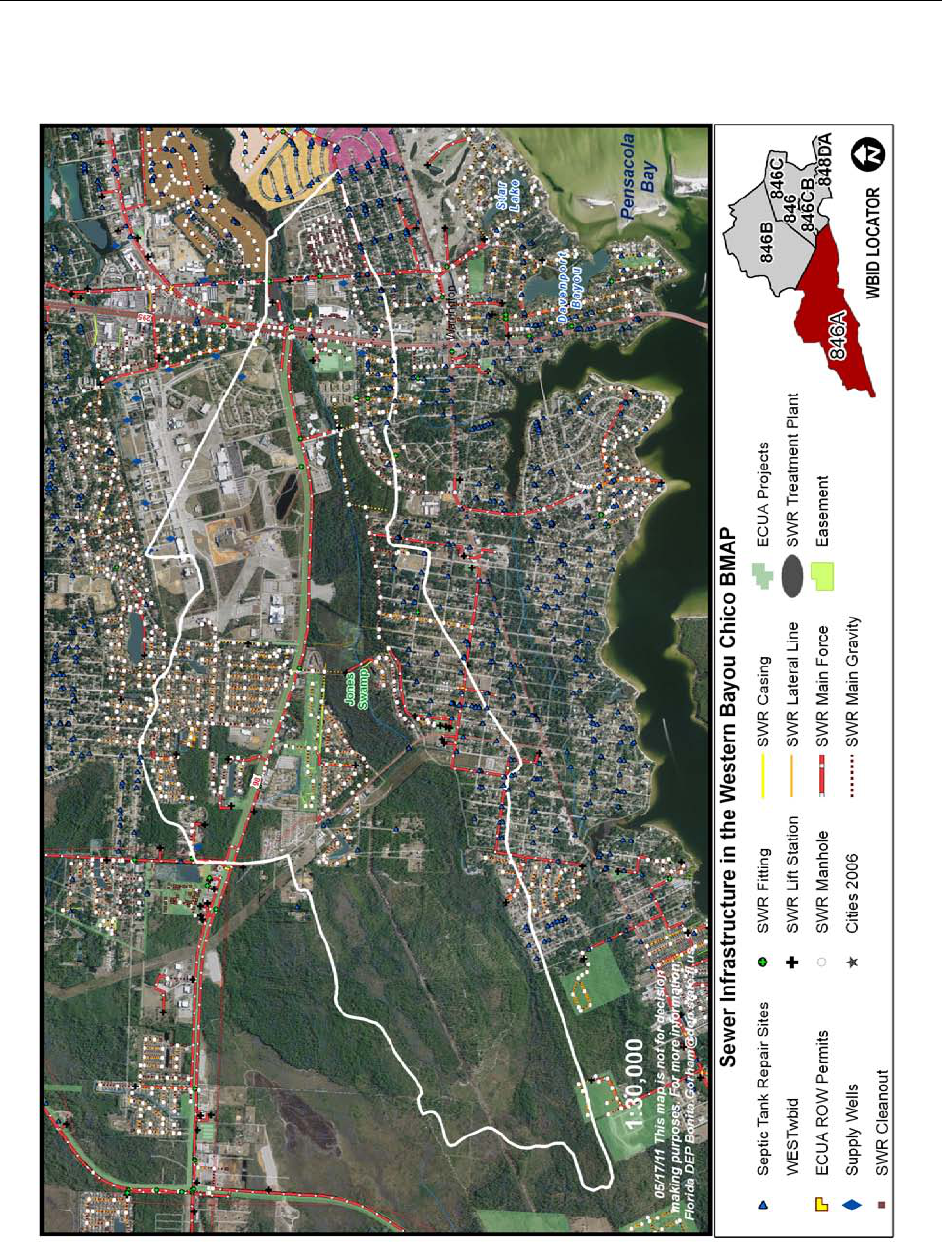

Figure 3-2: Sewer Infrastructure in the Western Bayou Chico Watershed ..................................... 26

Figure 4-1: Septic Tank Repairs in the Bayou Chico Watershed ..................................................... 33

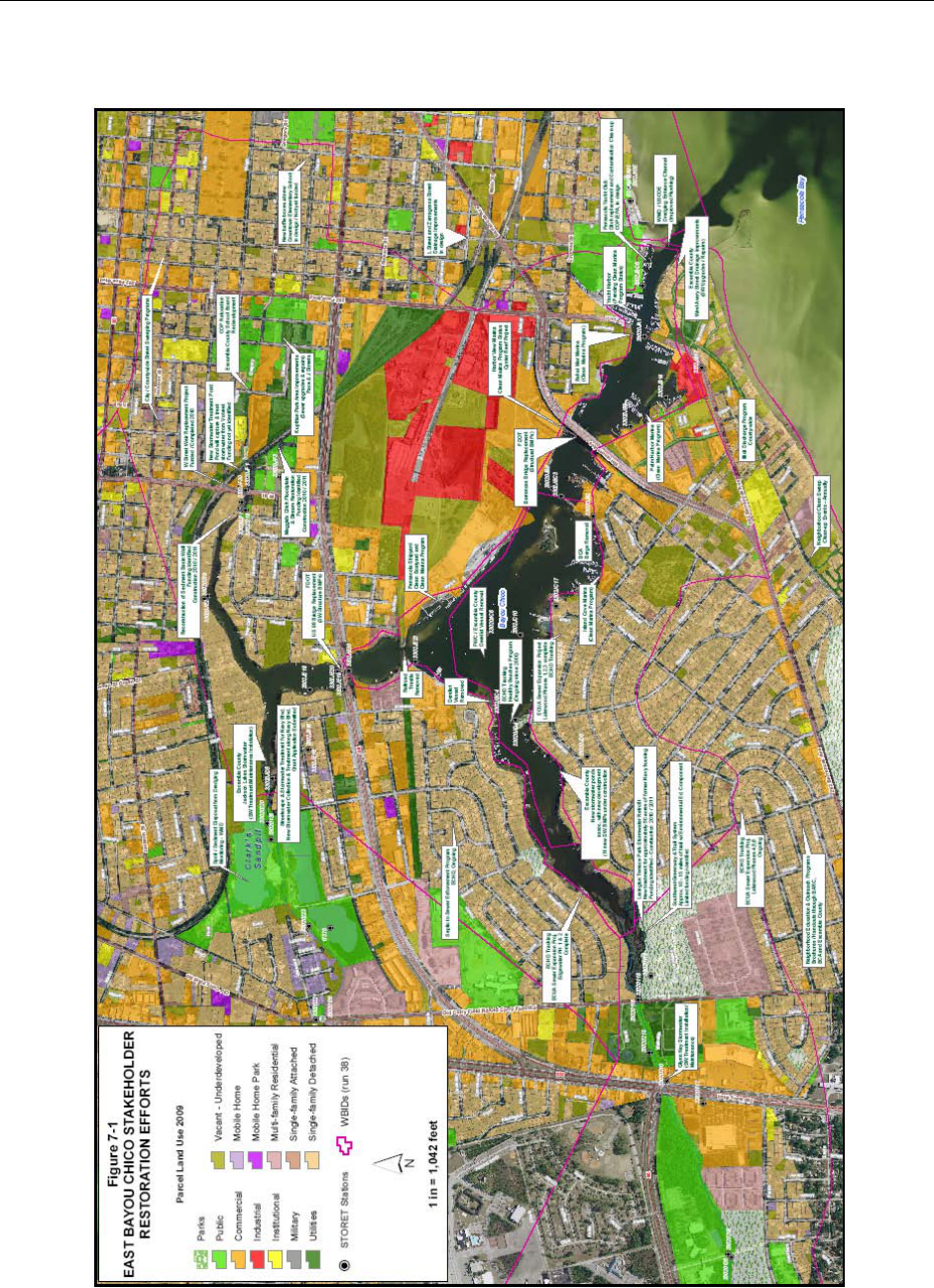

Figure 7-1: Stakeholder Restoration Efforts in the Eastern Bayou Chico Watershed ................... 55

Figure 7-2: Stakeholder Restoration Efforts in the Western Bayou Chico Watershed .................. 56

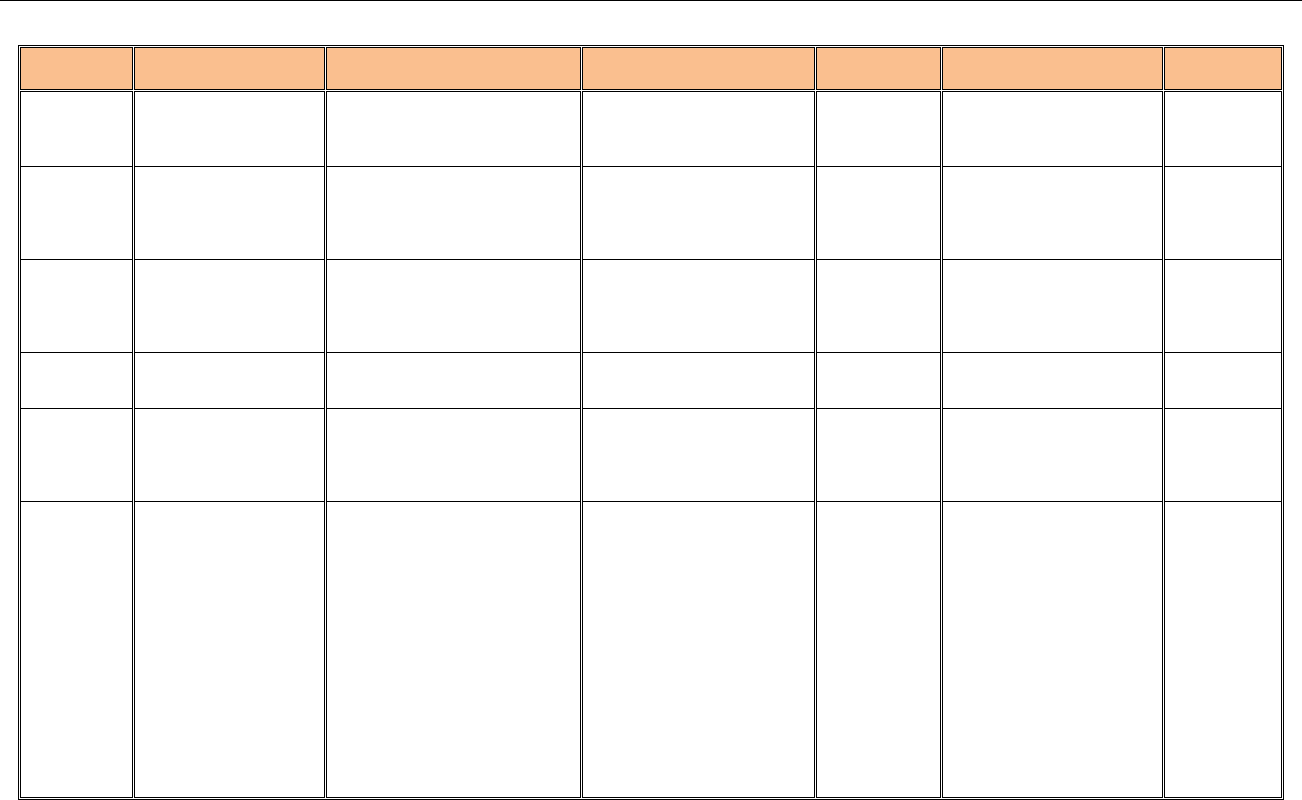

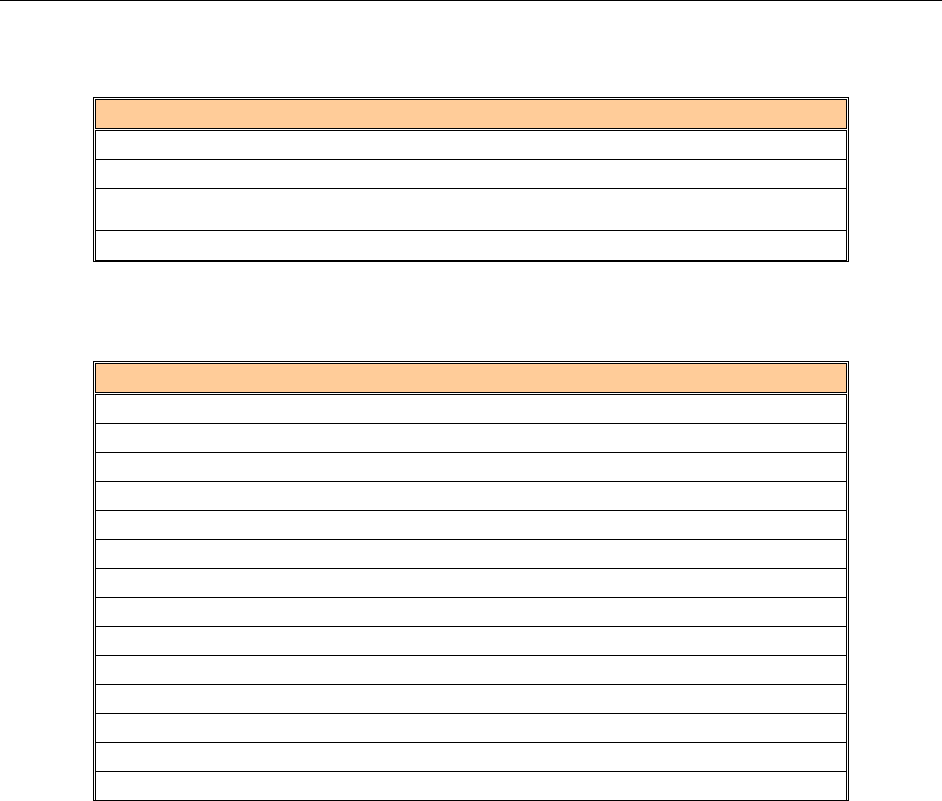

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1-1: Designated Use Attainment Categories for Florida Surface Waters .............................. 1

Table 1-2: Phases of the Watershed Management Cycle ..................................................................... 4

Table 1-3: Bayou Chico Fecal Coliform TMDL .................................................................................. 13

Table 3-1: Sewer Expansion Program Projects in the Bayou Chico Watershed ............................ 28

Table 3-2: Stakeholder Projects and Activities To Reduce Fecal Coliform Loadings from

Sanitary Sewer Sources ........................................................................................................ 31

Table 4-1: Stakeholder Projects and Activities To Reduce Fecal Coliform Loading from

OSTDS Sources ...................................................................................................................... 38

Table 5-1: Stakeholder Projects and Activities To Reduce Fecal Coliform Loading from

Stormwater Sources .............................................................................................................. 46

Table 6-1: Stakeholder Projects and Activities To Reduce Fecal Coliform Loading from

Marinas, Boatyards, and Moorings ................................................................................... 52

Table 7-1: Potential Source Control Categories in the Bayou Chico Watershed for

Addressing Load Reductions for Fecal Coliform and Other Bacteria .......................... 54

Table 8-1a: Water Quality Indicators ................................................................................................. 59

Table 8-1b: Field Parameters ................................................................................................................. 59

LIST OF TABLES: APPENDICES

Table A-1: Major Hydrologic Basins by Group and FDEP District Office .................................... 63

Table E-1: Proposed BMAP Annual Reporting Form ........................................................................ 81

Table G-1: Stormwater and Water Quality Protection Websites ................................................... 91

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

vii

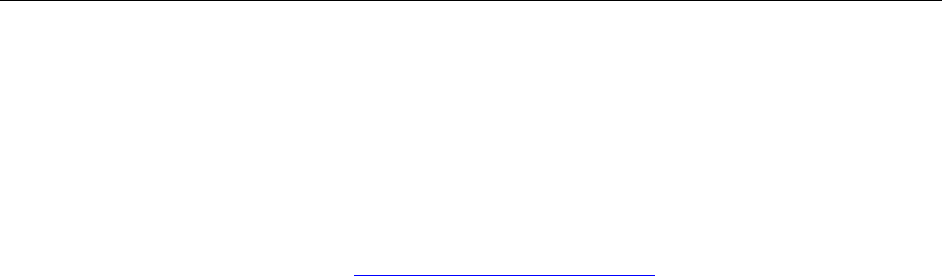

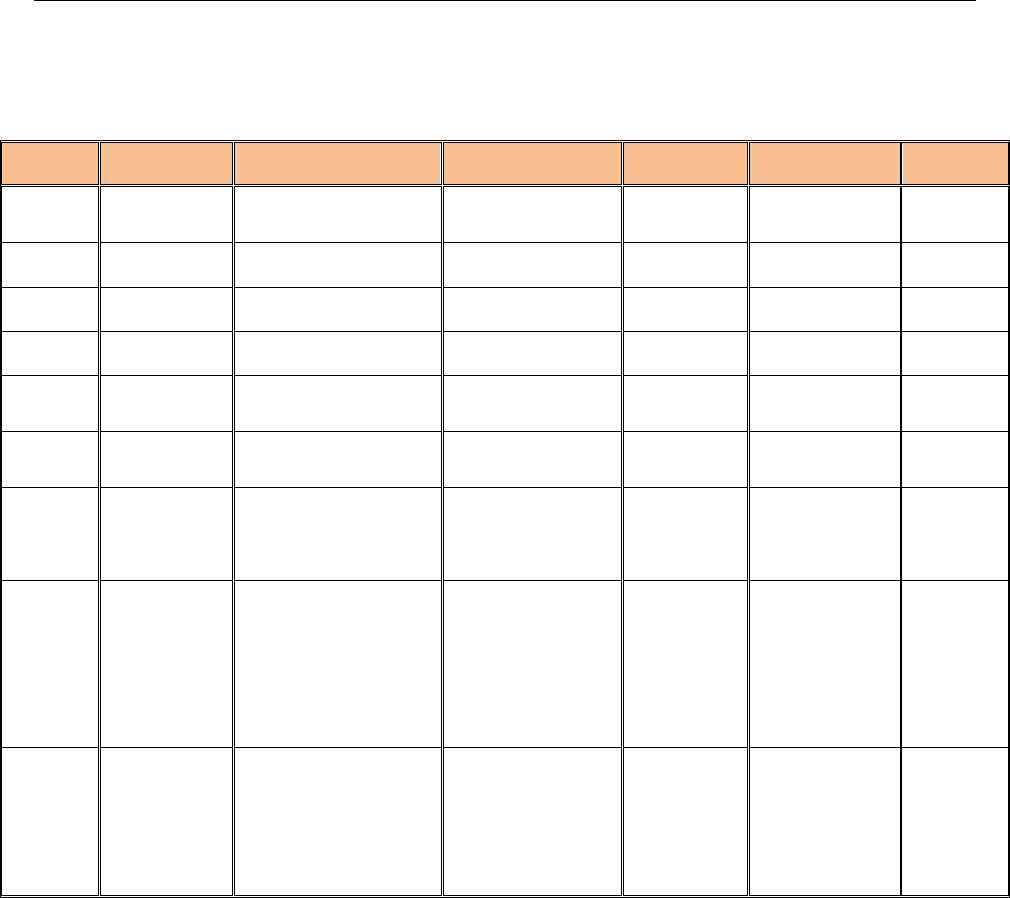

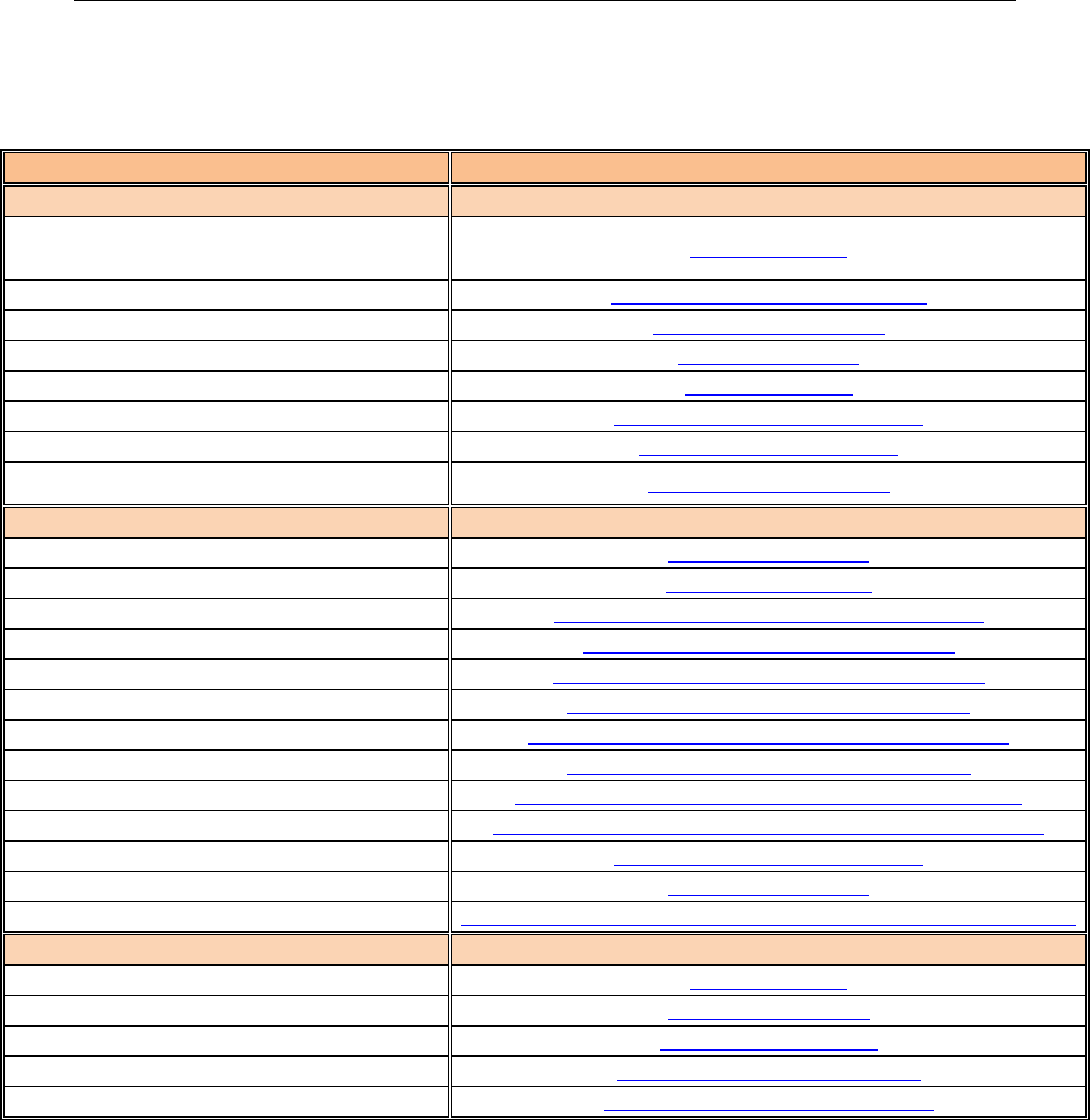

LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

A

CRONYM

/

A

BBREVIATION

E

XPLANATION

umhos/cm

Micromhos per Centimeter

ARV

Air Release Valve

ATAC

Allocation Technical Advisory Committee

AWT

Advanced Wastewater Treatment

BARC

Bay Area Resource Council

BAT

Best Available Technology

BCA

Bayou Chico Association

BMAP

Basin Management Action Plan

BMP

Best Management Practice

BOD

Biochemical Oxygen Demand

CAFOs

Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations

CDBG

Community Development Business Grant

CDS

Continuous Deflective Separation

CEDB

Center for Environmental Diagnostics and Bioremediation

CFU

Colony-Forming Units

CIP

Capital Improvement Program

CIPP

Cured in Place Pipe

CMOM

Capacity, Management, Operations, and Maintenance

COP

City of Pensacola

Counts/100mL

Counts per 100 Milliliters

CVA

Clean Vessel Act

CWA

Clean Water Act

CWRF

Central Water Reclamation Facility

DSR

Drainage System Repair

EAP

Environmental Analysis Program

ECHD

Escambia County Health Department

ECMR

Escambia County Marine Resources

ECUA

Emerald Coast Utility Authority

ECWQD

Escambia County Water Quality Division

EPA

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

F.A.C.

Florida Administrative Code

FCT

Florida Communities Trust

FDACS

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services

FDEP

Florida Department of Environmental Protection

FDOH

Florida Department of Health

FDOT

Florida Department of Transportation

FOG

Fats, Oils, and Grease (Program)

F.S.

Florida Statutes

FWC

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

FWRA

Florida Watershed Restoration Act

FY

Fiscal Year

GIS

Geographic Information System

HUD

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

viii

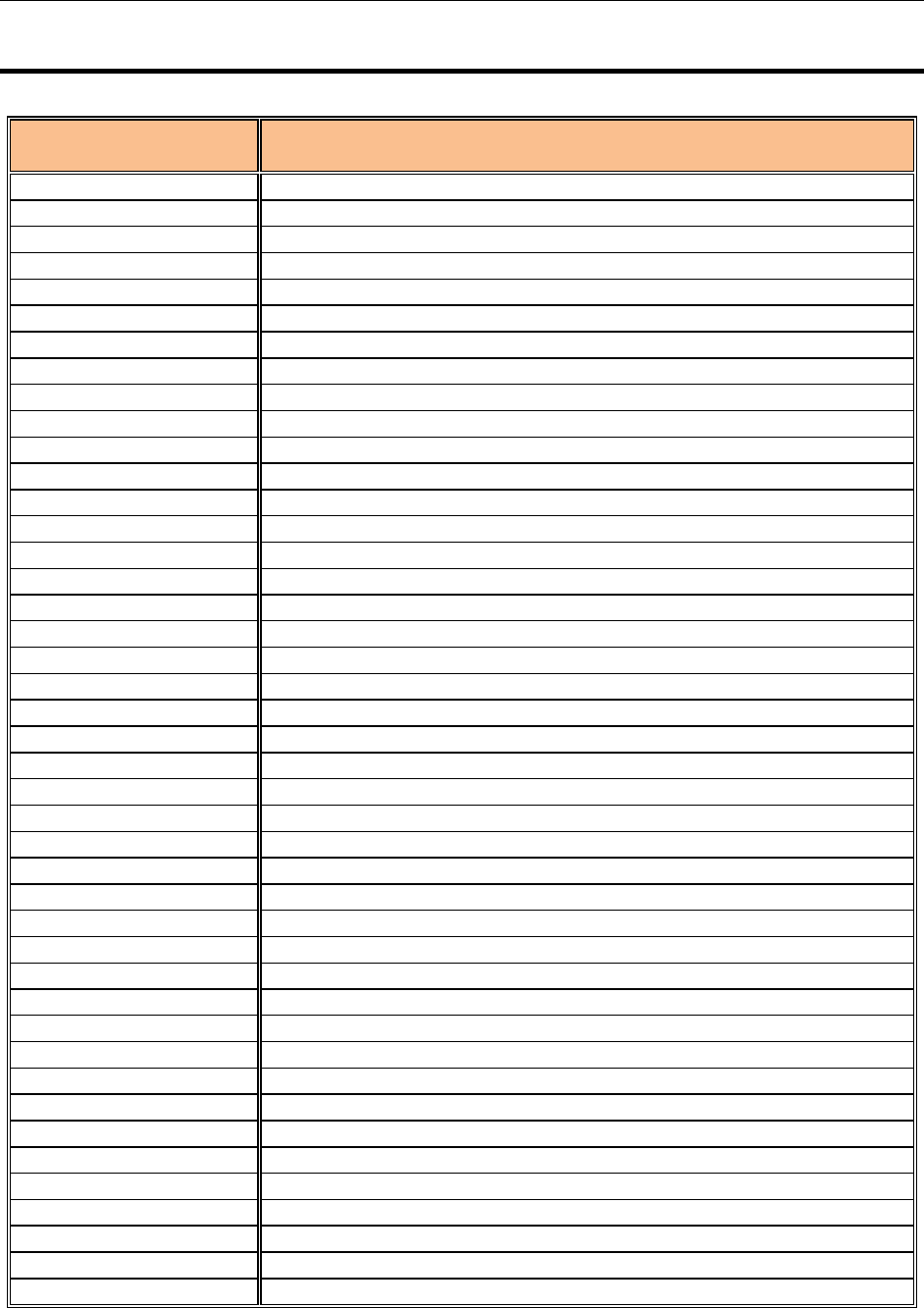

A

CRONYM

/

A

BBREVIATION

E

XPLANATION

I/E

Information and Education

I&I

Inflow and Infiltration

IWR

Impaired Surface Waters Rule

LA

Load Allocations

LF

Linear Feet

MF

Membrane Filter

MGD

Million Gallons per Day

mg/L

Milligrams per Liter

Mi

2

Square Miles

mL

Milliliter

MOS

Margin of Safety

MPN

Most Probable Number

MRP

Maintenance Rating Program

MS4

Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System

MSGP

Multi-Sector General Permit

MST

Microbial Source Tracking

MSWTTP

Main Street Wastewater Treatment Plant

NMWF

National Marine Waste Foundation

NOAA

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NOI

Notice of Intent

NPDES

National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System

NPS

Nonpoint Source Pollution

NRCS

Natural Resources Conservation Service

NTUs

Nephelometric Turbidity Units

NWFWMD

Northwest Florida Water Management District

OSTDS

Onsite Sewage Treatment and Disposal System

PAHs

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

PCBs

Polychlorinated Biphenyls

PCPs

Pentachlorophenols

PIC

Potential Illicit Connection

PLRGs

Pollutant Load Reduction Goals

ppt

Parts per Thousand

PSA

Public Service Announcement

PVC

Polyvinyl Chloride (pipe)

QA/QC

Quality Assurance/Quality Control

ROW

Right-of-Way

SCADA

Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition

SEP

Sewer Expansion Program

SIC

Standard Industrial Classification

SOP

Standard Operating Procedure

SSO

Sanitary Sewer Overflow

STORET

Storage and Retrieval (database)

SU

Standard Units

SWIM

Surface Water Improvement Program

SWPPP

Stormwater Pollution Prevention Plan

SWR

Sewer

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

ix

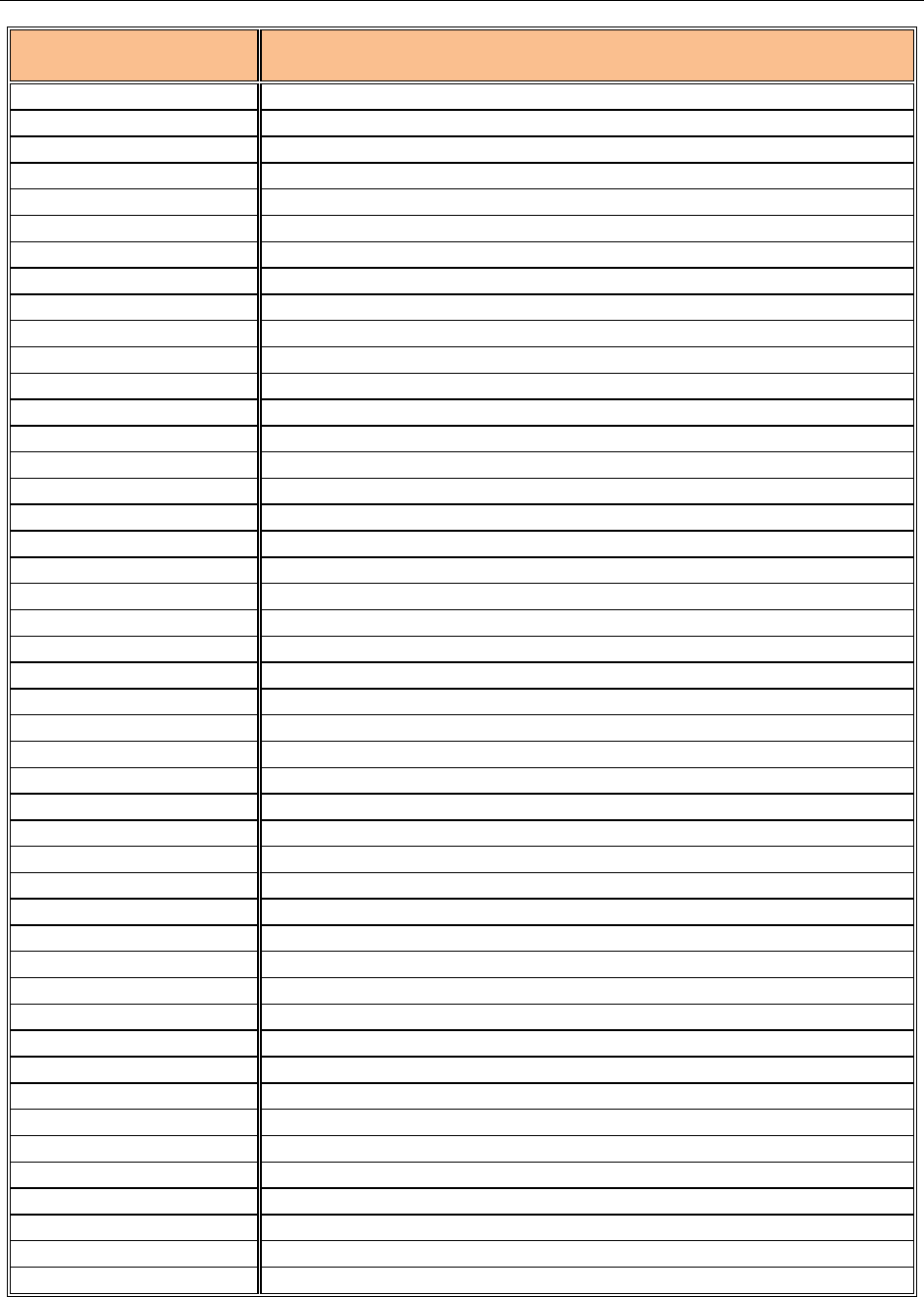

A

CRONYM

/

A

BBREVIATION

E

XPLANATION

TKN

Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen

TMDL

Total Maximum Daily Load

TN

Total Nitrogen

TP

Total Phosphorus

USACOE

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

USDA

U.S. Department of Agriculture

USGS

U.S. Geological Survey

UV

Ultraviolet (light)

UWF

University of West Florida

WBID

Waterbody Identification (number)

WLAs

Wasteload Allocations

WQSs

Water Quality Standards

WWTF

Wastewater Treatment Facility

WWTP

Wastewater Treatment Plant

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

x

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

BAYOU CHICO WATERSHED

The Bayou Chico watershed, located in the southern end of Escambia County, just east of Blue

Angel Parkway and north of Bayou Grande, has a 10.36-square-mile (mi

2

) drainage area and a

water surface area of approximately 0.39 mi

2

.

The waterbodies addressed by this Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) consist of Bayou

Chico, which discharges directly to Pensacola Bay, and the following six waterbody segments,

all of which flow into Bayou Chico and the bay: Jones Creek, Jackson Creek, Bayou Chico

Drain, Bayou Chico Beach (at Lakewood Park), Bayou Chico proper, and Sanders Beach.

The Bayou Chico watershed consists of two Class III fresh waterbodies (Jones Creek and

Jackson Creek) and four Class III marine waterbodies (Bayou Chico, Bayou Chico Drain, Bayou

Chico Beach, and Sanders Beach). Class III waterbodies have a designated use of recreation,

propagation, and the maintenance of a healthy, well-balanced population of fish and wildlife.

The water quality criterion applicable to the impairment addressed by the Bayou Chico Total

Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) is the Class III criterion for fecal coliform.

BAYOU CHICO TMDLS

TMDLs are water quality targets for specific pollutants (such as fecal coliform) that are

established for impaired waterbodies that do not meet their designated uses based on Florida’s

water quality standards. During Cycle 1 of the watershed management cycle in the Pensacola

Basin, as required by federal law, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP)

verified fecal coliform impairments in five of the six waterbodies in the Bayou Chico watershed.

In 2008, FDEP adopted TMDLs for the following waterbodies, which are included in the BMAP:

• Bayou Chico (Waterbody Identification [WBID] Number 846);

• Jones Creek (WBID 846A);

• Jackson Creek (WBID 846B);

• Bayou Chico Beach (WBID 846CB); and

• Sanders Beach (WBID 848DA).

In addition, a sixth segment, Bayou Chico Drain (WBID 846C), was verified impaired for fecal

coliform in Cycle 2 of the listing process. Also in Cycle 2, Bayou Chico (WBID 846) and Bayou

Chico Drain (WBID 846C) were verified impaired for nutrients (with total phosphorus [TP] as

the limiting nutrient), and this impairment will be further evaluated in subsequent BMAP

planning efforts for the Pensacola Basin.

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

xi

The Bayou Chico fecal coliform TMDL was calculated as the median of the percent reductions

needed over the data range where exceedances occurred, which in this case was over the entire

range of flow conditions. The source loadings (levels) for fecal coliform described in Section 2

would need to be reduced by 61% to achieve the required TMDL load reduction.

THE BAYOU CHICO BMAP

Stakeholder involvement is critical to the success of the TMDL Program, and varies with each

phase of implementation to achieve the same purpose—the attainment of water quality

standards for Bayou Chico. The BMAP development process is structured to achieve

cooperation and consensus among a broad range of interested parties.

Stakeholder involvement and meaningful public involvement are essential to develop, gain

support for, and secure commitments to implement a BMAP. They were a key component in

the development of the Bayou Chico BMAP. Beginning in February 2009, FDEP initiated the

BMAP development process for Bayou Chico and held a total of nine technical meetings. The

purpose of the meetings, all of which were open to the general public, was to consult with key

stakeholders to gather information on the impaired waterbody and its tributaries; identify

potential sources; conduct field reconnaissance; define programs, projects, and actions currently

under way; and develop the BMAP contents and actions that would result in improved water

quality, with the goal of achieving the TMDL target reductions.

This BMAP addresses the waterbodies in the Bayou Chico watershed that were verified

impaired for fecal coliform. Six segments that make up the entire watershed were impaired for

fecal coliform (as described earlier, five were identified in Cycle 1 of the watershed assessment

process and in the TMDL, and a sixth segment was listed for fecal coliform in Cycle 2).

The types of projects that stakeholders have been implementing over the last five years (2006–

11) that help to address these impairments include sanitary sewer expansion projects,

stormwater improvements, pet waste ordinance adoption, septic tank inspections and testing

(prior to property sales), neighborhood clean-sweep programs, barge and derelict vessel

removals, Clean Marina and Boatyard Program implementation, and Bayou Chico channel

dredging (improved flushing). This BMAP highlights these and other projects that will address

the known and suspected sources of fecal coliform and other pathogens, and demonstrate that

local stakeholders have taken a proactive stance in addressing future water quality concerns.

The projects and activities outlined in this BMAP have been determined to be “sufficient” to

address all of the identified sources and, with the full implementation of the BMAP, water

quality in the Bayou Chico watershed is expected to meet the TMDL requirements. Through

ongoing projects, studies, and monitoring efforts, the five-year BMAP milestone evaluation and

annual BMAP reviews should help stakeholders identify and address any additional sources

and any necessary actions that should be taken.

BMAP STAKEHOLDERS

FDEP worked with the following groups and organizations to prepare this BMAP:

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

xii

• Bay Area Resource Council (BARC), in conjunction with the West Florida

Regional Planning Council, comprises a cross-section of elected officials from

local governments representing the Pensacola Basin that have signed an interlocal

agreement. Through various activities, BARC works to share information

gathered for local planning purposes and to develop a restoration program for

Pensacola Bay;

• Bayou Chico Association (BCA) represents over 800 residents and commercial

and industrial interests in the Bayou Chico watershed. It facilitates efforts to help

the water quality, living, and working conditions on and around Bayou Chico;

• City of Pensacola;

• Emerald Coast Utility Authority (ECUA);

• Escambia County;

• Escambia County Health Department (ECHD), Florida Department of Health

(FDOH);

• Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP), Northwest District

Office;

• Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT);

• Pensacola Yacht Club;

• University of West Florida (UWF), Center for Environmental Diagnostics and

Bioremediation (CEDB) and Wetland Research Laboratory;

• U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Gulf Islands Marine Research

Laboratory; and,

• U.S. Naval Air Station

BMAP APPROACH

The 1999 Florida Watershed Restoration Act (FWRA) contains provisions that guide the

development of BMAPs and other TMDL implementation approaches. The Bayou Chico BMAP

provides for phased implementation under Paragraph 403.067(7)(a)1, Florida Statutes (F.S.). A

five-year milestone evaluation will be carried out to assess and verify that adequate progress is

being made towards achieving water quality standards and the load reductions identified in the

Bayou Chico TMDL. An adaptive management approach for TMDL implementation, as

described in the BMAP, will address reductions to fecal coliform bacteria, and the iterative

evaluation process will continue until reductions are attained.

This first five-year phase of the BMAP is designed to address the TMDL and work towards

achieving water quality standards in the watershed. It includes gathering additional

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

xiii

information or studies that can be used in the development of the subsequent phase(s) to

further support TMDL implementation, as well as more intensive monthly sampling to

determine the locations of particular hot spots that should be addressed. In addition, the

phased BMAP approach allows for the continued implementation of projects designed to

achieve reductions, while simultaneously implementing source assessment, carrying out

monitoring, and conducting studies to better understand fecal coliform variability and water

quality dynamics in each impaired waterbody.

SUFFICIENCY-OF-EFFORT EVALUATION

The Bayou Chico fecal coliform TMDL is expressed as a percent reduction based on in-stream

fecal coliform concentrations. This method of TMDL allocation precludes detailed allocations,

as it would be complicated, if not impossible, to equitably allocate to stakeholders based on a

percent reduction of in-stream concentrations. Fecal coliform are highly variable and easily

transported, making it difficult in most cases to identify the source of the bacteria.

Additionally, very few data are available that show the efficiency of stormwater best

management practices (BMPs) and management actions in removing or reducing fecal coliform.

FDEP evaluated fecal coliform reduction activities using a basinwide sufficiency-of-effort

approach by assessing identified potential sources and the specific activities over the entire

Bayou Chico watershed that will reduce or eliminate sources of fecal coliform loading. Thus,

this sufficiency-of-effort evaluation is not an evaluation of each entity’s individual activities;

rather, it focuses on whether these activities correspond to the potential sources identified in the

watershed and whether the total efforts are adequate to eliminate or reduce the known sources,

assess unknown sources, and prevent the development of new sources.

Based on source assessments and information gathered for this BMAP, a summary of

restoration activities (Section 7) was produced to identify the appropriate programs and

activities being implemented for the most likely sources in the Bayou Chico watershed. These

programs and activities are expected to either reduce or eliminate the known sources, or they

may be needed to further assess fecal coliform loadings. Both FDEP and key stakeholders have

deemed the full implementation of the management actions/projects identified in this BMAP as

sufficient to address the fecal coliform bacteria reductions needed to meet the target load

reductions defined in the TMDL for Bayou Chico.

KEY ELEMENTS OF THE BMAP

This BMAP addresses the key elements required by the FWRA, Chapter 403.067, F.S., including

the following:

• Document how the public and other stakeholders were encouraged to participate

or participated in developing the BMAP (Section 1.3.1);

• Equitably allocate pollutant reductions in the watershed (Sections 1.3.4 and

1.3.5);

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

xiv

• Identify the mechanisms by which potential future increases in pollutant loading

will be addressed (Section 1.5);

• Document management actions/projects to achieve the TMDL (Sections 3

through 7);

• Document the implementation schedule, funding, responsibilities, and milestones

(Sections 3 through 6); and

• Identify monitoring, evaluation, and a reporting strategy to evaluate reasonable

progress over time (Section 8).

ANTICIPATED OUTCOMES OF BMAP IMPLEMENTATION

Through the implementation of projects, activities, and additional source assessments as

documented in this BMAP, stakeholders expect the following outcomes:

• Improved water quality trends in the Bayou Chico watershed that will also help

improve water quality in other receiving waterbodies (e.g., Pensacola Bay);

• Decreased loading of the target pollutants (fecal coliform and other pathogens, i.e.,

Enterococcus sp.);

• Enhanced public awareness of fecal coliform sources and impacts on water quality;

• Enhanced effectiveness of corresponding corrective actions by stakeholders;

• Better understanding of the watershed’s hydrology, water quality, and pollutant

sources; and

• Improved ability to evaluate management actions, assess their benefits, and

identify additional pollutant sources.

BMAP COST

Costs were provided for 57% of the activities identified in the BMAP, with an estimated total

cost of more than $18,551,946 for capital projects and an estimated $1,000,000 to $1,500,000

(needed, or being funded) for ongoing programs, operation and maintenance, and restoration

proposals. In addition, some of the activities identified in the BMAP have no defined real or

actual costs (e.g., the Clean Marina and Boatyard Programs in Bayou Chico and state-funded,

e.g., ECHD programs). The funding sources for the ongoing improvements have typically come

from local contributions and homeowner associations, stormwater utility fees, and grants from

state and federal programs (such as Section 319 programs, National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration [NOAA] grants, and other programs). Technical stakeholders and local citizens

will continue to explore new opportunities for funding assistance to ensure that the activities

listed in this BMAP can be maintained at the necessary level of effort.

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

xv

BMAP FOLLOW-UP

As a part of BMAP follow-up, FDEP and stakeholders will track implementation efforts and

monitor water quality to determine additional sources and water quality trends. The sampling

locations in the monitoring plan were selected to identify potential sources of contamination

through source assessment monitoring at key locations throughout the watershed, and to track

trends in fecal coliform (and Enterococci) using existing monitoring stations with historical data.

In addition, more extensive monthly sampling is proposed at specific sampling locations where

fecal coliform counts have been historically high.

The source assessment monitoring will follow the established sampling protocol, in which any

observed fecal coliform counts of 5,000 colony-forming units per 100 milliliters (CFU/100mL) or

greater will be followed up with targeted sampling efforts (Tier 2) to determine and address the

source. FDEP, Escambia County, the city of Pensacola, BCA, and ECUA, in concert with FDEP’s

strategic monitoring network, will be responsible for the trend and source assessment sampling

(Tier 1) in the overall monitoring plan. These stakeholders have committed to assist or provide

services and/or monetary aid for a 3-year monitoring plan though the help of UWF and FDEP.

FDEP will add the analysis for Enterococcus as well as fecal coliform to its quarterly sampling.

Escambia County will provide assistance in monthly field sampling. Samples for Enterococcus

and fecal coliform will be processed by the Wetland Research Laboratory at UWF, while UWF’s

CEDB will help to compile and analyze the data, and will provide a three-year interim report on

water quality status and trends. In addition, ECHD will continue (biweekly) beach sampling

for fecal coliform and (weekly) Enterococcus bacteria counts at Bayou Chico (Lakewood Park)

and Sanders Beach, in conjunction with its Healthy Beaches Program. Furthermore, all data

collected for these follow-up BMAP efforts will be uploaded into FDEP’s STOrage and

RETrieval (STORET) database, where water quality data can be stored and readily retrieved by

WBID number(s) for watershed-wide assessments.

The Tier 2 analysis will specifically target the following areas: (1) probable or suspected loading

points previously identified, and (2) newly suspected spots, especially in the tributaries and

creeks that were not previously sampled. Samples will be taken both during dry and rainy

periods to isolate chronic and stormwater influences. Higher resolution sampling will be used

to resample identified loading areas for further confirmation and to assist in pinpointing

sources. Areas using septic tanks that were previously identified as hot spots and converted to

sanitary sewer service will be revisited to document any remediation of fecal loadings from that

activity.

The results of these efforts will be used to evaluate the effectiveness of the BMAP activities in

reducing fecal coliform loading in the Bayou Chico watershed. In addition, technical

stakeholders and local citizens will meet with FDEP at least every 12 months to discuss

implementation issues, consider new information, and determine what other management

strategies are needed, if monitoring indicates that additional measures are necessary to reduce

fecal coliform.

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

xvi

BENEFITS OF THE BMAP PROCESS

With the implementation of the activities outlined in this BMAP, in addition to the anticipated

outcomes noted above, the following benefits are expected:

• Increased coordination between state and local governments and within divisions

of local governments in problem solving for surface water quality restoration;

• Added security in obtaining additional state and local funding for water quality

restoration;

• Improved communication and cooperation among state and local agencies

responding to restoration needs; and

• The determination of effective projects through the stakeholder decision-making

and priority-setting processes.

COMMITMENT TO BMAP IMPLEMENTATION

Local technical stakeholders support the BMAP on behalf of the entities they represent and are

committed to ensuring that the plan to reduce fecal coliform in the Bayou Chico watershed is

implemented. In addition to this support, the BMAP was presented to BARC on April 27, 2011.

The BARC representatives comprise many of the watershed’s various stakeholders and include

many of the entities involved in developing this BMAP. These entities share their support of

the BMAP and activities in the watershed, and can ensure that as their staff and board members

change over time, BARC has a way to continue support for the BMAP and the efforts it

describes.

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

1

SECTION 1: CONTEXT, PURPOSE, AND SCOPE OF THE PLAN

1.1 WATER QUALITY STANDARDS AND TOTAL MAXIMUM DAILY

LOADS

Florida's water quality standards are designed to ensure that surface waters can be used for

their designated purposes, such as drinking water, recreation, and agriculture. Currently, most

surface waters in Florida, including those in the Bayou Chico watershed, are categorized as

Class III waters, which mean they must be suitable for recreation and must support the

propagation and maintenance of a healthy, well-balanced population of fish and wildlife. Table

1-1 shows all designated use categories.

Under Section 303(d) of the federal Clean Water Act, every two years each state must identify

its impaired waters, including estuaries, lakes, rivers, and streams that do not meet their

designated uses and that are not expected to improve within the subsequent two years. The

Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) is responsible for developing this

“303(d) list” of impaired waters.

TABLE 1-1: DESIGNATED USE ATTAINMENT CATEGORIES FOR FLORIDA SURFACE WATERS

* Class I and II waters include the uses of the classifications listed below them.

CATEGORY DESCRIPTION

Class I* Potable water supplies

Class II* Shellfish propagation or harvesting

Class III

Recreation, propagation and maintenance of a healthy, well-balanced population of

fish and wildlife

Class IV Agricultural water supplies

Class V Navigation, utility, and industrial use (no current Class V designations)

Florida's 303(d) list identifies hundreds of waterbody segments that fall short of water quality

standards. The three most common water quality concerns are fecal coliform, excess nutrients,

and oxygen-demanding substances from anthropogenic sources, resulting in impaired waters

that do not meet state standards. The listed waterbody segments are candidates for more

detailed assessments of water quality to determine whether they are impaired according to state

statutory and rule criteria. FDEP develops and adopts Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs)

for waterbody segments identified as impaired. A TMDL is the maximum amount of a specific

pollutant that a waterbody can assimilate while maintaining its designated uses.

The water quality evaluation and decision-making processes for listing impaired waters and

establishing TMDLs are authorized by Section 403.067, Florida Statutes (F.S.), also known as the

Florida Watershed Restoration Act (FWRA), and contained in Florida’s Identification of

Impaired Surface Waters Rule (IWR), Rule 62-303, Florida Administrative Code (F.A.C.). The

impaired waters in the Bayou Chico watershed addressed in this Basin Management Action

Plan (BMAP) are all Class III waters. The TMDLs established for the Bayou Chico watershed in

June 2008 identify the amount of fecal coliform and other pollutants that the watershed’s

waterbodies can receive and still maintain Class III designated uses.

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

2

The Bayou Chico watershed consists of two Class III fresh waterbodies (Jones Creek and

Jackson Creek) and four Class III marine waterbodies (Bayou Chico, Bayou Chico Drain, Bayou

Chico Beach, and Sanders Beach). Class III waterbodies have a designated use of recreation,

propagation, and the maintenance of a healthy, well-balanced population of fish and wildlife.

The water quality criterion applicable to the impairment addressed by the TMDL is the Class III

criterion for fecal coliform.

For assessment purposes, FDEP divided the Pensacola Basin into water assessment polygons

with a unique waterbody identification (WBID) number for each watershed or stream reach.

The Bayou Chico watershed was divided into six waterbody segments, and the TMDL

addressed potential sources of bacteria in five of these six segments: Bayou Chico (WBID 846),

Jones Creek (WBID 846A), Jackson Creek (WBID 846B), Bayou Chico Beach (WBID 846CB),

and Sanders Beach (WBID 848DA). The sixth segment, Bayou Chico Drain (WBID 846C), was

not listed as impaired prior to TMDL development. However, it was verified impaired for fecal

coliform in Cycle 2 of the watershed management cycle, and thus this BMAP includes site-

specific projects that may reduce or eliminate potential fecal coliform sources in WBID 846C.

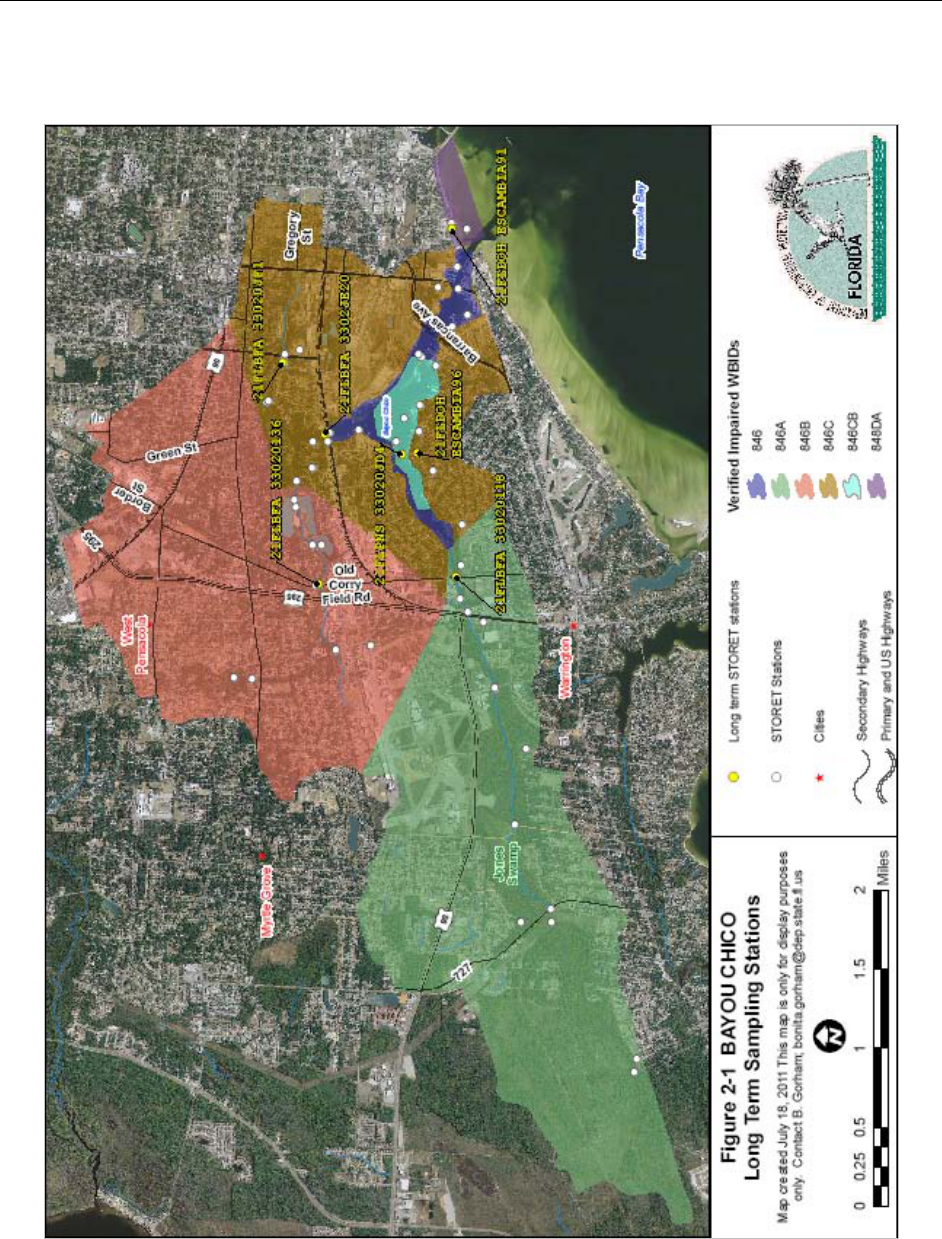

Figure 1-1 shows the verified impaired waterbodies discussed in this BMAP.

There are 25 sampling stations in the Bayou Chico watershed with historical coliform

observations. The primary data collector of historical data is the Bureau of Water within the

Florida Department of Health (FDOH), Florida Division of Environmental Health, which

maintains routine sampling sites at Bayou Chico and Sanders Beach (STORET IDs: 21FLDOH

ESCAMBIA96 and 21FLDOH ESCAMBIA91) (STORET refers to FDEP’s STOrage and RETrieval

database). These sites were sampled between 2 and 6 times per month from August 14, 2000,

through June 27, 2005. Additional sampling was conducted by FDEP up to 5 times per month,

and by the Bream Fisherman’s Association on a quarterly basis. Sample data also collected by

the Florida Division of Environmental Health were also used in the TMDL.

The verified period for the TMDL was January 1, 1998, through June 30, 2005. Of the 965 fecal

coliform samples collected within the verified period, 920 qualified samples could be used to

establish the Bayou Chico TMDL (since 45 sampling events occurred on days without

corresponding U.S. Geological Survey [USGS] flow measurements). The samples used in the

TMDL calculation ranged from 0 to 25,000 counts per 100 milliliters (counts/100mL).

Samples were collected in all months of the year, and exceedances occurred in each of the

months. At least 64 samples were collected during a given month, with the greatest number of

samples (105) collected in March and December. The number of exceedances ranges from a low

of 4 in January to a high of 35 in September. More than 50% of exceedances during the verified

period occurred in all months except January, February, and March.

Numeric criteria for bacterial quality are expressed in terms of fecal coliform bacteria

concentrations. The water quality criterion for the protection of Class III waters, as established

by Rule 62-302, F.A.C., states the following:

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

3

FIGURE 1-1: BAYOU CHICO WATERSHED LOCATION MAP

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

4

Fecal Coliform Bacteria:

The most probable number (MPN) or membrane filter (MF) counts per 100 mL of fecal coliform

bacteria shall not exceed a monthly average of 200, nor exceed 400 in 10% of the samples, nor

exceed 800 on any one day.

The criterion states that monthly averages shall be expressed as geometric means based on a

minimum of 10 samples taken over a 30-day period. However, during the development of load

curves for the impaired streams, there were insufficient data (fewer than 10 samples in a given

month) available to evaluate the geometric mean criterion for fecal coliform bacteria. Therefore,

the criterion selected for the TMDL was “not to exceed 400 in 10% of the samples.”

TMDLs are developed and implemented as part of a watershed management cycle that rotates

through Florida’s 52 river basins every 5 years (see Appendix A) to evaluate waters, determine

impairments, and develop and implement management strategies to restore impaired waters to

their designated uses. Table 1-2 summarizes the five phases of the watershed management

cycle.

TABLE 1-2: PHASES OF THE WATERSHED MANAGEMENT CYCLE

PHASE ACTIVITIES

Phase 1

Preliminary evaluation of water quality

Phase 2

Strategic monitoring and assessment to verify water quality impairments

Phase 3

Development and adoption of TMDLs for waters verified as impaired

Phase 4

Development of management strategies to achieve the TMDL(s)

Phase 5

Implementation of TMDL(s), including monitoring and assessment

1.2 TMDL IMPLEMENTATION

Rule-adopted TMDLs may be implemented through BMAPs, which contain strategies to reduce

and prevent pollutant discharges through various cost-effective means. During Phase 4 of the

TMDL process, FDEP and the affected stakeholders in the various basins jointly develop

BMAPs or other implementation approaches. The FWRA contains provisions that guide the

development of BMAPs and other TMDL implementation approaches. Appendix B

summarizes the statutory provisions related to BMAP development and implementation.

Stakeholder involvement is critical to the success of the watershed assessment (Phase 2), TMDL

development and adoption (Phase 3), and BMAP development (Phase 4), and varies with each

phase of implementation to achieve different purposes. The BMAP development process is

structured to achieve cooperation and consensus among a broad range of interested parties.

Under statute, FDEP invites stakeholders to participate in the BMAP development process and

encourages public participation to the greatest practicable extent. FDEP holds at least one

noticed public meeting in each basin to discuss and receive comments during the planning

process.

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

5

1.3 THE BAYOU CHICO BMAP

1.3.1 STAKEHOLDER INVOLVEMENT

Meaningful public involvement was a key component in the development of the Bayou

Chico BMAP. The BMAP process promotes the engagement of local stakeholders in a

coordinated and collaborative manner to address the reductions in fecal coliform

bacteria needed to achieve the Bayou Chico TMDL. It also builds on existing water

quality improvement programs and local participation to address water quality

problems.

The following organizations and entities are key stakeholders in the Bayou Chico

watershed:

• Bay Area Resource Council (BARC), in conjunction with the West Florida

Regional Planning Council, consists of a cross-section of elected officials from

local governments representing the Pensacola Basin (Escambia and Santa Rosa

Counties and the municipalities of Pensacola, Gulf Breeze, and Milton) and other

organizations that have signed an interlocal agreement. Its mission is “to develop

annual goals and identify projects for implementation by engaging in agreements

or contracts with public and private entities for assistance in planning, financing,

and managing the physical, chemical, biological, economic, and aesthetic aspects of

the Pensacola Bay System, to share information gathered for local planning

purposes, and to develop a restoration program for the Pensacola Bay System”

(EPA 2011);

• Bayou Chico Association (BCA) is a voluntary organization representing over

800 residents and commercial and industrial interests in the Bayou Chico

watershed. Organized for charity, education, and science, it facilitates efforts to

help the water quality, living, and working conditions on and around Bayou

Chico;

• City of Pensacola;

• Emerald Coast Utility Authority (ECUA);

• Escambia County;

• Escambia County Health Department (ECHD), Florida Department of Health

(FDOH);

• Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP), Northwest District

Office;

• Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT);

• Pensacola Yacht Club;

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

6

• University of West Florida (UWF), Center for Environmental Diagnostics and

Bioremediation (CEDB) and Wetland Research Laboratory;

• U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Gulf Islands Marine Research

Laboratory; and,

• U.S. Naval Air Station

In February 2009, FDEP initiated the BMAP development process and held a series of

technical meetings involving key stakeholders and the general public. The purpose of

these meetings was to consult with key stakeholders to gather information on the

impaired waterbody and its tributaries, in order to aid in the development of the BMAP

and identify specific management actions that would improve water quality. Beginning

in 2009, a total of nine technical meetings, all open to the public, were held for the

purposes of gathering information; identifying potential sources; conducting field

reconnaissance; defining programs, projects, and actions currently under way; and

developing the BMAP contents and actions that will result in improved water quality

with the goal of achieving the TMDL target reductions. Stakeholder involvement is

essential to develop, gain support for, and secure commitments to implement the

BMAP.

In addition to stakeholder input on the technical issues of BMAP development, FDEP

solicited further input from key stakeholder groups at the management level through a

presentation to BARC on April 27, 2011. BARC’s technical representatives constitute

many of the same stakeholders as in the Bayou Chico watershed and include many of

the entities directly involved in developing this BMAP. These entities share their

support of the BMAP and activities in the watershed, and can ensure that as their staff

and board members change over time, BARC has a way to continue support for the

BMAP and the efforts it describes.

This BMAP document reflects the input of the technical stakeholders, along with public

input from workshops and meetings held to discuss important aspects of the TMDL and

BMAP development. Appendix C provides further details about the stakeholder and

public involvement process in BMAP development.

1.3.2 PLAN PURPOSE AND APPROACH

The purpose of this BMAP is to implement the load reductions established in the fecal

coliform TMDL for the Bayou Chico watershed. The plan outlines specific actions to

achieve load reductions and a schedule for implementation. In addition, it details a

monitoring approach to identify additional sources of fecal coliform (and Enterococcus)

and to track trends in water quality. Following BMAP adoption, basin stakeholders will

meet at least annually to review the progress made toward achieving target load

reductions in the Bayou Chico watershed.

This BMAP addresses six impairments for fecal coliform in the watershed, all centered

on tributaries of the larger bayou. Specifically, it focuses on actions that reduce fecal

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

7

coliform levels, with a goal of meeting water quality standards and load reductions as

defined in the TMDL. Some water quality concerns in the bayou may benefit from these

BMAP actions, such as issues with excess nutrients and turbidity (as verified in Cycle 2

of the watershed management cycle), while other concerns, such as a history of elevated

levels of contaminants in sediments (polychlorinated biphenyls [PCBs] and

dioxins/furans), must be addressed through programs other than the TMDL and BMAP

process.

Therefore, it should be emphasized that this BMAP does not address all of the water

quality issues in the watershed; rather, it is specifically developed to address

anthropogenic sources and elevated levels of fecal coliform, Enterococcus, and other

human-borne bacteria. The Bayou Chico BMAP contains a comprehensive set of

strategies focused on the primary sources of bacteria, such as wastewater treatment

plants (WWTPs), sewage pumping stations, onsite sewage treatment and disposal

systems (OSTDS), marina activities (e.g., septic pump outs), and urban sources,

including stormwater, pet waste, and other potential bacterial sources in the bayou.

Though considerable effort has been taken to understand the dynamics of the TMDL

waterbodies, the relationship of fecal coliform water quality exceedances to pollutant

sources is not well understood. Where specific fecal coliform sources have been

identified, the stakeholders have proposed projects and activities to eliminate those

sources. There are also other nonhuman sources that can contribute to fecal coliform

impairments, such as wildlife, that are not addressed in this BMAP.

For the projects and programs in the BMAP, quantitative values for pollutant load

reduction activities cannot be calculated due to the lack of scientific information on

bacteria removal rates for best management practices (BMPs) or activities that reduce

fecal coliform levels. While certain BMPs are expected to prevent or eliminate fecal

coliform sources, it is not known exactly how much of a reduction will occur in the

waterbody. As a result, the expected date on which target load reductions of fecal

coliform addressed in the TMDL will be achieved is difficult to predict; however, the

stakeholders do expect that significant water quality improvements can be achieved by

the end of the first five-year BMAP cycle through ongoing and future activities, planned

projects, and county and citywide programs to eliminate sources, as outlined in this

BMAP. Coordinated efforts to monitor fecal coliform concentrations, in conjunction

with the implementation of projects basinwide, will also enhance the capability to

quantify positive effects in the future.

Furthermore, key stakeholders are committed to continue future assessments of

potential sources and source controls through the implementation of projects, programs,

and public education campaigns to eliminate potential sources, as well as to monitor the

water quality impairment(s) to achieve the reductions established in the fecal coliform

TMDL for Bayou Chico.

1.3.3 PLAN SCOPE

In an effort to address the known impairments, FDEP consulted with key stakeholders

to describe potential sources and available water quality, spatial, and geographic data

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

8

that would be useful in the BMAP. The available data and local knowledge in the

watershed pointed to the most probable sources of fecal coliform. These fall into five

main categories (not in order of magnitude), as follows: (1) OSTDS; (2) sewer

infrastructure; (3) urban stormwater and nonpoint pollution sources; (4) marinas located

in the bayou, as well as other recreational boaters who enter (and sometimes moor in)

the bayou; and (5) natural background such as wildlife (including wildlife parks,

sanctuaries, and rookeries).

FDEP used existing reports and the local knowledge of technical stakeholders to

establish a baseline to assist in identifying projects and activities that would address

potential sources and specific monitoring needs and plans, all of which are included in

this BMAP.

A “weight-of-evidence” approach was used to help identify likely sources of fecal

coliform and guide follow-up reconnaissance and investigations into corrective action.

This approach uses the best information available at the time to summarize impairments

and identify potential sources, and then focuses on watershed management efforts and

classifies priority areas or hot spots to support decisions related to fecal coliform

reduction efforts. This weight-of-evidence method, in conjunction with best professional

judgment and local knowledge of the bayou and of likely sources, was used to aid in

source identification to the maximum extent possible. In addition, the identification of

specific projects in the Bayou Chico watershed, their proximity to potential hot spots,

and the expected positive outcome in achieving fecal coliform reductions were taken

into consideration in evaluating a weight-of-evidence approach.

At this time, water quality modeling has not been used to assess the temporal

relationship between the source of fecal coliform and the associated impact on the

impaired waterbodies. Due to the intrinsic variability of fecal coliform and the diffuse

nature of nonpoint sources, modeling is not a viable consideration; therefore, the

weight-of-evidence approach seems the best way to assess information on the most

likely sources and a particular project’s associated benefit(s).

BMAPs do provide for phased implementation approaches under Paragraph

403.067(7)(a)1, F.S. The adaptive management approach for TMDL implementation

described in this BMAP will address fecal coliform bacteria reductions, and the iterative

evaluation process will continue until the target load reductions defined in the TMDL

are met. A phased BMAP approach also allows for the implementation of projects

designed to achieve reductions while simultaneously executing source assessments,

monitoring, and studies to better understand fecal coliform variability and water quality

dynamics in each impaired waterbody.

This first five-year phase of the BMAP is designed to address the TMDL and the

achievement of water quality standards in the watershed. This phase may include

gathering additional information or carrying out studies that can be used in the

development of the subsequent phase(s), which further support TMDL implementation.

The adaptive management process will continue until the TMDL pollutant load

reduction requirements are met.

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

9

A five-year milestone evaluation in this BMAP will be carried out to verify that adequate

progress is being made toward achieving the TMDL. During the fifth year following

BMAP adoption (anticipated to be 2015), water quality data will again be evaluated for

in-stream reductions of fecal coliform levels within each WBID, or identified hot spots.

If significant reductions are not achieved by the end of this five-year implementation

phase, additional efforts may be necessary and will be reassessed. In addition, this five-

year milestone provides opportunities to further improve source assessment and

management measures going forward. Future projects that may be identified can open

opportunities for continued reductions and move into the next phase of implementation,

with the objective being to improve water quality trends, with the goal of reaching the

target TMDL reduction over the entire watershed.

In addition to stakeholder management actions, BMAP monitoring efforts will continue

in the watershed on a long-term basis. With many management actions already in place,

water quality data collected after 2008 began showing some reductions in fecal coliform

levels. The majority of the planned management actions will be implemented by the

end of 2012. In addition, a number of well-established long -term monitoring stations in

the watershed will continue to be monitored weekly or biweekly for both fecal coliform

counts and for Enterococcus bacteria by ECHD (Sanders and Bayou Chico Beach). Other

monitoring stations in the watershed are regularly monitored by Escambia County and

the Bream Fisherman’s Association. UWF also established a number of monitoring

points for its 2001–03 study of urban watersheds that included Bayou Chico (Snyder

2003). That study provided additional baseline data and information relating to

particular hot spots where fecal coliform and Enterococcus bacteria counts were

measured.

This BMAP details a monitoring approach to identify additional sources of fecal

coliform and to track trends in water quality. FDEP will meet with stakeholders at least

annually to review progress made towards achieving the TMDLs.

In summary, the implementation of key projects and actions identified in the Bayou

Chico BMAP, along with the implementation of the strategic monitoring plans described

in the BMAP, should achieve water quality improvements, and management actions

may be adjusted as needed to show continued progress.

1.3.4 SUFFICIENCY-OF-EFFORT DETERMINATIONS

Fecal coliform can be highly variable and easily transported, making it difficult in many

cases to identify the source of the bacteria. Based on the potential sources in each WBID,

the stakeholders were asked to identify completed activities carried out to reduce or

remove bacteria sources since 1995 (the start of the TMDL verified period), as well as

additional efforts that are currently under way or planned in the next five years.

Escambia County, ECUA, city of Pensacola, ECHD, FDOT District 3, West Florida

Regional Planning Council (in association with BARC), U.S. Naval Air Station, and BCA

all submitted project sheets and program descriptions for the prevention, reduction, and

source removal activities they conduct in the BMAP planning area and/or on a

countywide or citywide basis. FDEP then used a sufficiency-of-effort approach to

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

10

conduct a basinwide assessment of potential sources and cumulative projects and

activities that address or eliminate fecal coliform loading.

This sufficiency-of-effort evaluation was not an assessment of each agency’s individual

activities; rather, it focused on whether the activities submitted by all entities

corresponded to potential sources or hot spots previously identified and whether the

total efforts were adequate to eliminate the known sources, assess unknown sources,

and/or prevent the development of new sources.

During a sufficiency-of-effort evaluation, FDEP reviews the following information about

each WBID:

• Documentation of the most likely sources;

• A geographic information system (GIS) database to determine the spatial and

temporal distribution of the sources based on existing land use and activities;

• Permit and water quality information;

• Relevant field information and published data; and

• The completed corrective actions.

As the evaluation was conducted, the agencies’ programs and activities for each type of

source were recorded in a table summarizing restoration activities (Table 7-1). Because

the controllable sources (sewer infrastructure, septic tanks, and stormwater

conveyances) vary considerably among the individual WBIDs, the actions and

responsibilities of the stakeholders also vary considerably in the Bayou Chico

watershed.

The criteria for sufficiency for OSTDS-related efforts included the following:

designation as a septic tank failure or nuisance area in accordance with ECHD

requirements (as described in Section 4) that prioritizes these areas for transition to

sewer service; the status of phase outs to sewer in critical OSTDS failure areas; the

number of complaint investigations and any resulting enforcement actions; the number

of septic tank repair permits; and the proximity of repair sites to surface waters or

stormwater inlets. In addition, program implementation was evaluated for efforts such

as inspections, training programs, plan reviews, and site visits, as well as the regulation

of annual operating permits. Local ordinances were also evaluated for their ability to

proactively address potential OSTDS failures.

The criteria for sufficiency for sewer infrastructure included the assessment of recent

sewer line upgrades within the watershed, as well as evaluation of sanitary sewer

overflow (SSO) history to determine if previous problems were addressed through

repairs and upgrades. Rehabilitated manholes can prevent overflows from occurring at

the manhole and potentially reaching surface waters or the stormwater system;

therefore, manhole rehabilitation and targeted monitoring efforts were also evaluated.

Sanitary sewer programs that are carried out system wide or countywide, such as sewer

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

11

line inspections and rehabilitation, SSO investigations, and infiltration and inflow (I&I)

programs were also evaluated as measures to prevent and control sewer infrastructure

as a potential fecal coliform source.

The stormwater sufficiency evaluations included a review of flood control projects

(which reduce fecal coliform loading by preventing water from inundating septic

systems) and stormwater BMPs, such as wet/dry retention and baffle boxes (which

reduce sediment buildup that can provide a breeding ground for fecal coliform).

Consideration was also given to the maintenance of stormwater ditches, ponds, and

closed conveyances to prevent debris, vegetation, dense tree canopy, and sediment from

potentially providing conditions that would allow the growth of new sources of fecal

coliform bacteria.

Another important activity that was evaluated was the detection and removal of

potential illicit connections (PICs) to stormwater conveyances to eliminate illegal

discharges that can contribute fecal coliform and other pollutants into surface waters.

Stormwater-related program implementation also included public education campaigns,

the Adopt-A-Highway Program, street sweeping, drainage connection permits, and

countywide and citywide inspection programs, all of which may reduce the

contaminants entering stormwater conveyance systems.

Additionally, stakeholders (through BARC and BCA) are developing and implementing

pet waste programs, Clean Marina and Clean Vessel Programs, and other public

education campaigns using public service announcements, website content, conferences,

and printed handouts to raise awareness through public outreach and education. ECHD

also shares brochures and information related to leaking septic tanks, permit

requirements, and other important handouts on OSTDS with the public and through its

website. In addition, Escambia County ordinances are in place for OSTDS inspections

prior to property sales, and for pet waste management.

In efforts specific to each source, the entities also participate in special source assessment

activities. These include the strategic sampling of several public access points to Bayou

Chico (Lakewood Park and Sanders Beach) and follow-up sampling at locations where

high counts occur, in an effort to identify potential sources or suspected hot spots.

Based on source assessments and information gathered for this BMAP, a summary of

restoration activities (Section 7) was produced to ensure that appropriate programs and

activities were being implemented that would either decrease or eliminate the known

sources, or that might be needed to further assess fecal coliform loadings. The full

implementation of the management actions/projects identified in this BMAP was

deemed sufficient to address the fecal coliform bacteria reductions needed to achieve the

fecal coliform reductions described in the TMDL.

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

12

1.3.5 POLLUTANT REDUCTION AND DISCHARGE ALLOCATIONS

1.3.5.1 CATEGORIES FOR RULE ALLOCATIONS

The rules adopting TMDLs must establish reasonable and equitable allocations that will

alone, or in conjunction with other management and restoration activities, attain the

target reductions defined in the TMDL. Allocations may be to individual sources,

source categories, or drainage areas that discharge to the impaired waterbody. The

allocations identify either in terms of how much pollutant discharge (which for fecal

coliform is expressed in CFUs per day) that each source designation may continue to

contribute (discharge allocation), or in terms of the percentage loading that the source

designation must reduce (percent reduction allocation). Currently, the TMDL allocation

categories are as follows:

• Wasteload Allocation – The allocation to point sources permitted under the

National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Program includes

the following:

o Wastewater Allocation is the allocation to industrial and domestic

wastewater facilities; and

o NPDES Stormwater Allocation is the allocation to NPDES stormwater

permittees that operate municipal separate storm sewer systems

(MS4s). These permittees are treated as point sources under the TMDL

Program.

• Load Allocation - The allocation to nonpoint sources, including agricultural

runoff and stormwater from areas that are not covered by an MS4.

This approach is consistent with federal regulations (40 CFR § 130.2[I]), which state that

TMDLs can be expressed in terms of mass per time (e.g., pounds per day), toxicity, or

other appropriate measure. The TMDL for the Bayou Chico watershed was expressed in

terms of percent reduction, and represents the maximum annual fecal coliform load the

watershed can assimilate and maintain the fecal coliform criterion.

1.3.5.2 INITIAL AND DETAILED ALLOCATIONS

Under the FWRA, the TMDL allocation may be an “initial” allocation among point and

nonpoint sources. In such cases, the “detailed” allocation to specific point sources and

specific categories of nonpoint sources must be established in the BMAP. The FWRA

further states that the BMAP may make detailed allocations to individual “basins” (i.e.,

sub-basins) or to all basins as a whole, as appropriate. Both initial and detailed

allocations must be determined based on a number of factors listed in the FWRA,

including cost-benefit, technical and environmental feasibility, implementation time

frames, and others (see Appendix B).

Due to the nature of fecal coliform impairments, this BMAP does not specify detailed

allocations. It is difficult to attribute the fecal coliform loads to specific sources because

bacteria are highly variable and can be easily transported. In addition, research and

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

13

information are not available to quantify the expected fecal coliform reduction from

project implementation. Instead of assigning detailed allocations, a sufficiency-of-effort

evaluation (as described above) was conducted to assess whether the management

actions carried out by the entities in the watershed were sufficient to address potential

sources of fecal coliform, or to address known or suspected areas of high exceedances of

the water quality criterion.

1.3.5.3 BAYOU CHICO WATERSHED FECAL COLIFORM TMDL

The water quality criterion for fecal coliform bacteria is detailed in Subsection

62-302.530(6), F.A.C. The requirements for exceeding maximum fecal coliform

concentrations in a Class III waterbody are stated as follows:

The most probable number (MPN) or membrane filter (MF) counts per 100 milliliters (mL) of

fecal coliform bacteria shall not exceed a monthly average of 200, nor exceed 400 in 10% of

samples, nor exceed 800 on any one day.

FDEP has verified six WBIDs in the Bayou Chico watershed as impaired for fecal

coliform bacteria and adopted a TMDL to address these impairments in June 2008.

Table 1-3 lists the TMDL and pollutant load allocations adopted by rule for the

watershed.

TABLE 1-3: BAYOU CHICO FECAL COLIFORM TMDL

* The percent reduction is based on the 10

th

to 90

th

percentile of recurrence intervals minus the wasteload allocation.

WBID

TMDL

(%

REDUCTION

)

WASTELOAD

ALLOCATION FOR

WASTEWATER

(CFU

S

/100

M

L)

W

ASTELOAD

ALLOCATION FOR

NPDES

STORMWATER

(%)

LOAD ALLOCATION*

(%)

Bayou Chico watershed

(WBIDS 846, 846A, 846B,

846C, 846CB, and 848DA)

61%

Point sources must

meet permit limits

61% 61%

1.3.5.4 BACKGROUND AND POLLUTANT CONSIDERATIONS IN BAYOU CHICO

Pensacola Bay is a saline bay with about a one-half mile channel to the Gulf of Mexico.

The bay is the receiving body of water for Escambia and East Bays and Bayous Texar,

Chico, and Grande. The flushing of the bay is adequate, though it has water quality

problems due to nonpoint and point sources and urbanization. Bayou Chico has had a

long history of human activities and associated problems, including polluted

stormwater runoff, wastewater inputs, nutrient enrichment, and contaminated

sediments from urban runoff and industrial pollution. Prior to 1971, at least eight

industrial and domestic wastewater facilities discharged into Bayou Chico.

Both the Northwest Florida Water Management District (NWFWMD) and the University

of West Florida (UWF) have published studies that indicated the presence of polycyclic

aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), pentachlorophenols (PCPs), and trace metals in both the

sediments and water in Bayou Chico (Debusk et al. 2002; Liebens et al. 2007). The bayou

Draft Bayou Chico Basin Management Action Plan – October 2011

14

is adjacent to the abandoned American Creosote Works site, a National Priority List

hazardous waste site that may still be affecting the bayou.

A review of the scientific literature shows that the quality of the water and sediments in

Bayou Chico has been, and is still, affected by a variety of pollutants. Liebens et al.

(2006) state, “In the 1970s, organic pollutants were found to be many times higher than

typical values for coastal sediments.” Studies have shown elevated levels of

polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dioxins/furans in seafood from the bayou

(Snyder and Karouna-Renier 2009). Trace metals are also elevated in the main part of

the bayou and between two topographic constrictions in the northern half of the bayou.

Organisms affected by the pollution of Bayou Chico have diminished in density and

diversity. Two other nearby industrial sites also have documented environmental

problems, though their impact on the bayou is not well known.

The lower portion of Bayou Chico was dredged between March and August 2008. The

NWFWMD partnered with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACOE) on the project.

Dredged spoil was placed in the northwest pond of the Clark Sand Pit. The NWFWMD

carried out monitoring during and following the deposition to determine the quality of

water discharging into Jackson Branch Creek and to track saltwater movement into the

lower water zone and into nearby wells. A potential issue whose impacts are still

unknown is the behavior of the contaminants in the spoil after disposal. Even though

these pollutants may not pose a direct threat to humans, who have limited direct contact

with the sediments of Bayou Chico, they do have the potential to indirectly affect human

health.