Tribal Renewable

Energy Development

Literature Review

June 2023

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

ii

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................... ii

Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................... v

List of Tables ............................................................................................................................. v

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 1

Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 2

Sources Consulted ................................................................................................................. 2

Part I: Tribal Renewable Energy Resources ............................................................................. 3

Types of Renewable Energy Resources ................................................................................. 3

Types of Projects .................................................................................................................... 5

Tribal Roles and Options ..................................................................................................... 6

Project Ownership ................................................................................................................. 8

Current Market Conditions .................................................................................................. 8

Key Market Opportunities ................................................................................................................. 8

State Laws and Regulations: Barriers and Opportunities ............................................................ 9

Transmission and Distribution System Expansion and Upgrades ........................................... 10

Part II: Federal Laws, Regulations, Policies and Guidance .................................................... 11

Type I: Federal Indian Laws and Regulations ..................................................................... 11

Long-Term Leasing Act of 1955 .................................................................................................... 11

Long-Term Leasing Act Amendments—HEARTH Act .............................................................. 13

Right-of-Way Acts ........................................................................................................................... 14

Contracts Act.................................................................................................................................... 14

Indian Mineral Development Act of 1982 ..................................................................................... 14

Indian Tribal Energy Self-Determination Act (Title V of the Energy Policy Act of 2005) ...... 15

Tribal Energy Resource Agreements ................................................................................................ 16

Certified Tribal Energy Development Organizations ....................................................................... 16

Type II: Federal Environmental Laws ................................................................................. 16

The National Environmental Policy Act ........................................................................................ 17

National Historic Preservation Act ................................................................................................ 18

Species Protection Acts ................................................................................................................. 19

Clean Air Act .................................................................................................................................... 20

Clean Water Act .............................................................................................................................. 20

Type III: Federal Energy Regulatory Laws .......................................................................... 20

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

iii

Type IV. Federal Tax Laws ................................................................................................... 21

Inflation Reduction Act .................................................................................................................... 21

Other Federal Tax Benefits ............................................................................................................ 23

Part III. Renewable Energy Project Development ................................................................. 24

Federal Renewable Energy Information ............................................................................ 24

Tribal Energy Planning ...................................................................................................................... 24

Solar, Wind, Biomass, Storage Project Development Cycle .............................................. 25

Phase I: Project Potential ................................................................................................................. 26

Phase II. Project Options: Siting, Ownership, Technology ....................................................... 26

Phase III. Project Refinement: Development Agreements, NEPA, Approvals,

Funding/Financing ........................................................................................................................... 27

Phase IV. Project Implementation ................................................................................................ 27

Phase V. Project Operations/Maintenance ................................................................................. 28

EPA Onsite Solar + Storage Development .......................................................................... 28

Geothermal Project Development ...................................................................................... 29

Part IV. Federal Financial and Technical Assistance ............................................................. 30

Major Technical Assistance ................................................................................................. 30

Bipartisan Infrastructure Law ............................................................................................ 30

Inflation Reduction Act ........................................................................................................ 31

Tribal Specific Programs ................................................................................................................ 31

Tax Credits and Rebates ............................................................................................................... 32

Environmental and Energy Programs .......................................................................................... 32

Standing Federal Programs ................................................................................................. 33

Part V. Putting it all Together ................................................................................................ 33

Key Challenges .................................................................................................................... 33

Internal Barriers ................................................................................................................................ 34

External Barriers ............................................................................................................................... 34

Tribal Case Studies .............................................................................................................. 34

Blue Lake Rancheria (CA) Microgrid ................................................................................................ 34

Picuris Pueblo (NM) community solar .............................................................................................. 35

Spokane Housing Authority (WA) rooftop ........................................................................................ 35

Moapa Band of Paiute Indians (NV) Utility Scale Solar .................................................................. 35

Campo Band of Kumeyaay (CA) Commercial Wind ......................................................................... 36

Navajo Tribal Utility Authority Solar Projects ................................................................................... 37

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

iv

Development and Deployment Key Takeaways ................................................................. 37

Bibliography ............................................................................................................................ 38

General Resources ............................................................................................................... 38

Tribal Renewable Energy Resource Assessments .............................................................. 38

Biomass ................................................................................................................................ 38

Geothermal .......................................................................................................................... 38

Hydrogen ............................................................................................................................. 39

Hydropower ......................................................................................................................... 39

Solar ..................................................................................................................................... 39

Wind ..................................................................................................................................... 39

Market/Industry .................................................................................................................. 39

State Laws/Policies .............................................................................................................. 40

Transmission ....................................................................................................................... 40

Microgrids ............................................................................................................................ 40

Energy Planning .................................................................................................................. 40

Project Development .......................................................................................................... 41

Laws, Regulations, Related Guidance/Handbooks ........................................................... 41

Federal Financial and Technical Assistance....................................................................... 42

Law Articles .......................................................................................................................... 43

Index of Acronyms .................................................................................................................. 44

Appendices .............................................................................................................................. 46

Appendix A. Example of DOE descriptions of major “fatal flaws” in utility scale renewable

energy development ............................................................................................................ 46

Appendix B: Solar Resource Crosswalk .............................................................................. 47

Appendix C: Wind Resource Crosswalk .............................................................................. 49

Appendix D: Biomass Resource Crosswalk ........................................................................ 51

Appendix E: Geothermal Resource Crosswalk ................................................................... 52

Appendix F: Hydroelectric Resource Crosswalk ................................................................ 53

Appendix G: Hydrogen Resources Crosswalk .................................................................... 54

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

v

Table of Figures

Figure 1. Example of a distributed energy system. .................................................................................... 6

Figure 2. NEPA and NHPA processes related to Section 106 ................................................................ 19

Figure 3. Project Development Cycle ....................................................................................................... 25

Figure 4. Phase I. Project Potential federal resources ........................................................................... 26

Figure 5. Phase II. Project Options federal resources ............................................................................ 27

Figure 6. Phase III. Project Refinement federal resources ..................................................................... 27

Figure 7. Phase IV. Project Implementation federal resources ............................................................. 28

Figure 8: Solar Project Development Pathway ........................................................................................ 28

Figure 9: Development and Approval Process ........................................................................................ 29

Figure 10. Blue Lake Rancheria microgrids. ........................................................................................... 35

Figure 11. Moapa Band of Paiute Indians utility scale solar project. .................................................... 36

Figure 12. Campo Band of Kumeyaay commercial wind project. .......................................................... 36

List of Tables

Table 1: Summary of Tribal Technical Potential by Capacity and Generation ......................................... 3

Table 2: Utility-Scale Technical Potential on Tribal Lands in Contiguous 48 States ............................... 4

Table 3: Tribal Roles and Options in Renewable Energy Development .................................................... 7

Table 4: Tribal Risks in Renewable Energy Development ......................................................................... 7

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

vi

This page intentionally left blank.

Kauffman and Associates, Inc., (KAI) prepared this document for Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

An American Indian-owned management firm, KAI is dedicated to enhancing the reach and

effectiveness of caring organizations.

At KAI, we do work that matters.

kauffmaninc.com

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

1

Executive Summary

The Tribal Renewable Energy Projects literature review is intended to provide a comprehensive, but

abbreviated, summary of the information and sources available to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)

Division of Energy and Mineral Development (DEMD) and Indian Energy Service Center (IESC), and to

Indian tribes related to renewable energy project development and deployment on Indian lands. The

sources reviewed include:

• federal laws, regulations, and guidebooks;

• federal agency websites, guidance, reports and other work products;

• industry information, reports and research;

• other state government information;

• academic information and

• law review articles.

This review covers major topic areas, including background information on tribal energy resources,

project options, market considerations, transmission and implications of state law and regulations.

Focus is placed on the complex federal legal scheme that influences, controls, and regulates

renewable energy projects on Indian lands. In addition, there is a more in-depth review of project

development phases and resources available to support project development. Further, the review

provides a summary of the major federal funding programs for financial assistance. Finally, the

document concludes with a discussion of challenges, success factors, examples of various tribal

projects, and an overall summary of the tribal renewable energy development process.

It is important to note that the renewable energy industry is a fast and ever moving industry in terms

of markets, incentives, tax benefits, and technologies. So, while this review attempts to capture a

summary of relevant information as of the date of this document, it is highly recommended that both

the BIA and Indian tribes continue to keep track of major developments in the industry.

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

2

Introduction

The Department of the Interior BIA contracted with Kauffman and Associates, Inc., for consulting

services for the Renewable Energy Accelerated Deployment for Indian Country (READI). One task of

the services includes the completion of a literature review that will establish a baseline of current

statutes, regulations, standard operating procedures and handbooks, as well as current conditions for

renewable and distributed energy development in Indian Country. The report is intended to inform

topics and priorities for tribal engagement.

As defined in the scope of work, this report includes:

a) Renewable and distributed energy resources and applications including, but not limited to,

solar, wind, hydroelectric, geothermal, biofuel, microgrids, energy storage, hydrogen, and

supporting infrastructure.

b) An understanding of the development activities, including, but not limited to, planning,

permitting, financing, development agreements, construction, operation and maintenance,

and reclamation in relation to renewable and distributed energy resources and applications.

Further, the report is intended to assist the BIA, in its tribal engagement, with understanding what

tribes need from the BIA to promote renewable energy development opportunities, and what the BIA

can do to provide assistance to tribes. Many additional Federal Agencies have a role with energy

development on Indian land. The primary focus of READI is to improve BIA programs and procedures,

however the roles of other federal agencies are also considered regarding related programs and

coordination.

Sources Consulted

To identify resources that are most relevant to tribal energy development and address the BIA's

objectives and inform answers to the BIA's goals, a search strategy was developed that focused on

manual searches of:

• relevant federal laws, statutes, regulations, and standard operating procedures;

• all data available through BIA, including available programs and incentives;

• federal agency websites for published reports and information;

• known reliable sources of market information, such as nonprofits, foundations, industry

associations, and governmental associations;

• scholarly papers related to renewable and distributed energy programs; and

• conference proceedings and unpublished literature, including independent research studies

and dissertations.

A full bibliography of all sources reviewed for this report is included starting on page 38.

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

3

Part I: Tribal Renewable Energy Resources

Part one of this document provides introductory information related to tribal renewable energy

resources. This includes types of renewable energy resources, types of projects, tribal roles and

options, project ownership and current market conditions. Altogether, this background information

provides a foundation for tribal renewable energy resource options offering definitions of key industry

terms, and an overview of tribal renewable energy development opportunities.

Types of Renewable Energy Resources

In 2013, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) published the first Geospatial Analysis of

Renewable Energy Technical Potential on Tribal Lands. In this analysis, NREL reported that "the

technical potential on tribal lands is about 6% of the total national technical generation potential. This

is disproportionately larger than the 2% tribal lands in the United States, indicating an increased

potential density for renewable energy development on tribal lands." Table 1 summarizes the

estimated technical potential across several renewable energy resources.

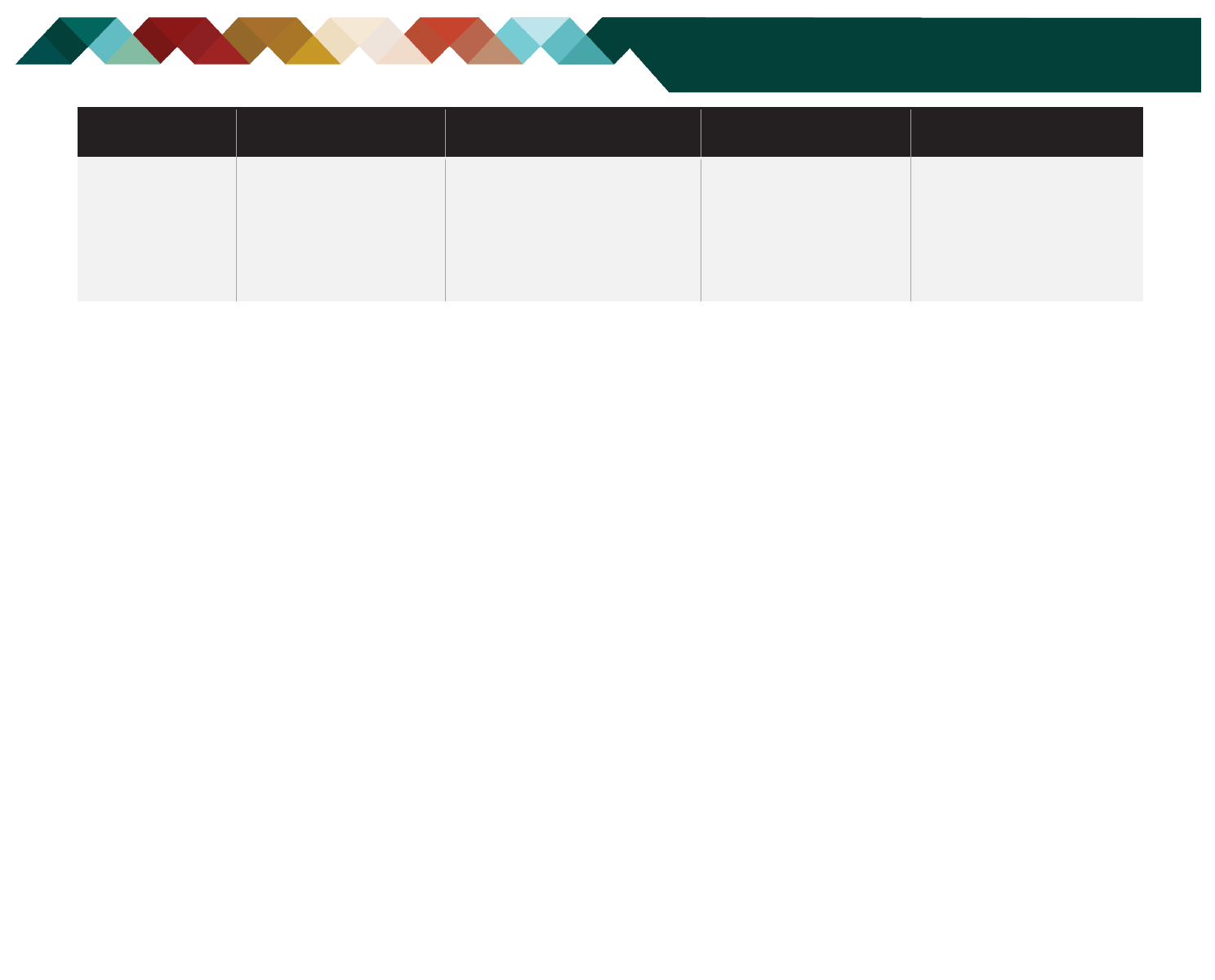

Table 1: Summary of Tribal Technical Potential by Capacity and Generation

Technology

1

Tribal

Capacity

Potential

2

(MW)

National

Capacity

Potential

3

(MW)

Tribal

Generation

Potential

(MWh)

National

Generation

Potential

(MWh)

% of National

Capacity

% of National

Generation

Solar PV (Utility-Scale

Rural)

6,888,33

9

152,973,

829

14,322,522

,713

280,613,216

,903

4.5% 5.1%

Solar PV (Utility-Scale

Urban)

8,199

1,217,69

9

17,578,618

2,231,693,7

46

0.7% 0.8%

Solar CSP

1,818,18

5

38,066,4

01

6,139,851,

743

116,146,244

,587

4.8% 5.3%

Wind (80 m height,

>=30% GCF)

347,505

10,954,7

59

1,146,044,

229

32,784,004,

656

3.4% 3.5%

Geothermal (EGS)

763,252

3,975,73

5

6,017,487,

000

31,344,696,

024

19.2% 19.2%

Geothermal

(Hydrothermal)

641 30,033 5,050,724 236,780,000 2.1% 2.1%

Biomass (Solid)

551

50,707

4,340,642

399,774,091

1.1%

1.1%

Biomass (Gaseous)

85

11,232

673,465

88,551,445

0.8%

0.8%

Hydropower

1,687

60,000

7,390,196

258,953,000

2.8%

2.9%

Total

4

9,855,44

4

207,340,

394

27,660,939

,330

464,103,914

,451

4.8% 6.0%

1

Each technology is evaluated separately; the same land area might be available for many technologies.

2

Lopez, A. et al. (2012). U.S. Renewable Energy Technical Potentials: A GIS-Based Analysis. NREL/TP-6A20-51946. Golden,

CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

3

Lopez, A. et al. (2012). U.S. Renewable Energy Technical Potentials: A GIS-Based Analysis. NREL/TP-6A20-51946. Golden,

CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

4

Technical potential calculated for each technology individually and does not account for overlap (i.e., the same land area

may be identified with potential for wind and solar and would be counted twice in the total). Some technologies may be

compatible with mutual development.

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

4

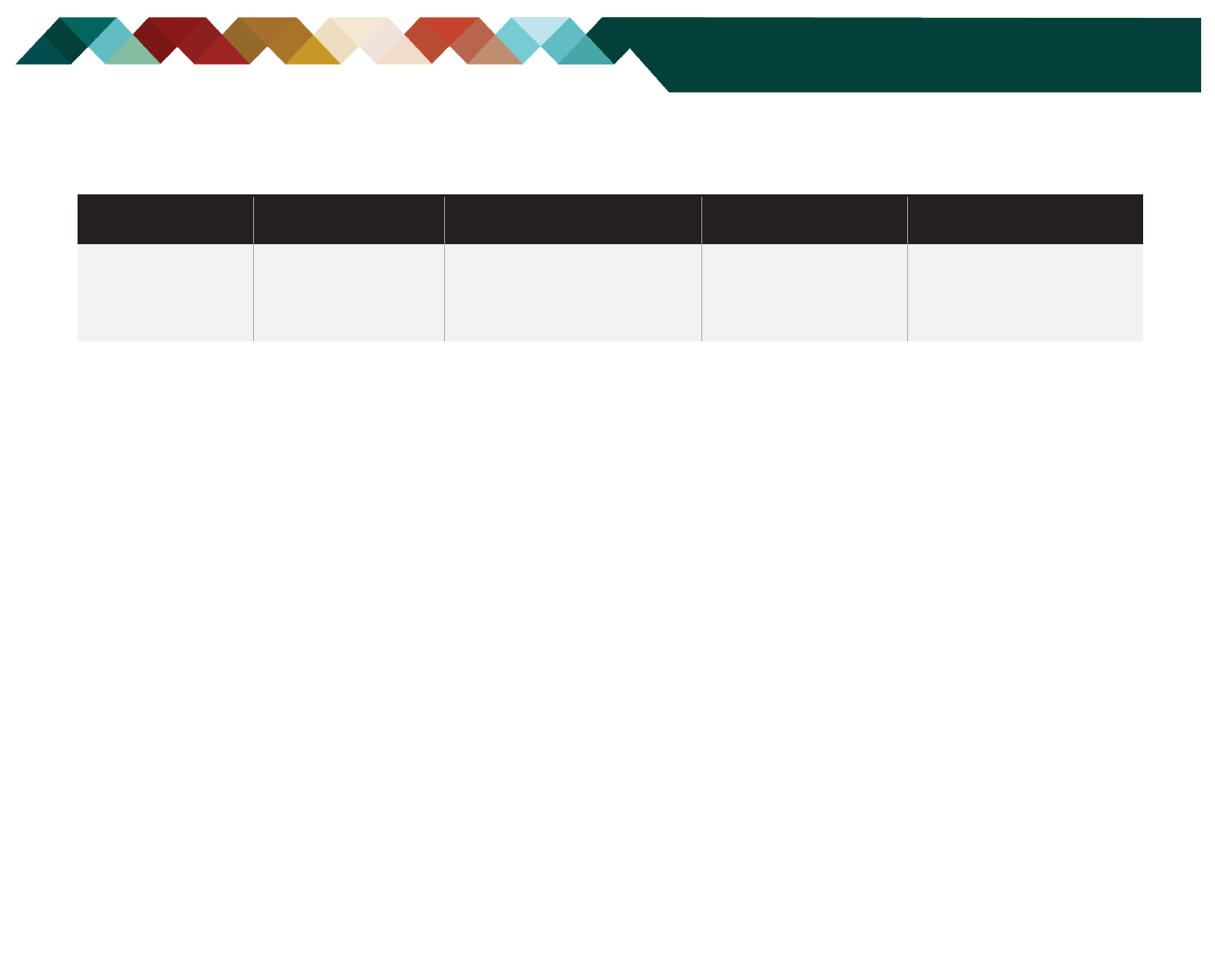

In 2018, NREL updated its analysis to focus on utility scale applications. Table 2 shows the technical

potential of tribal lands in the contiguous 48 states.

Table 2: Utility-Scale Technical Potential on Tribal Lands in Contiguous 48 States

Technology

Tribal

Capacity

Potential

(GW)

National

Capacity

Potential

(GW)

National

Capacity

(%)

Tribal

Generation

Potential

(TWh)

National

Generation

Potential

(TWh)

National

Generation

(%)

Utility-scale PV

6,035

118,918

5%

10,689

197,087

5.4%

CSP

2,114

26,318

8%

7,701

92,994

8.3%

Wind

891

10,119

8.8%

2,394

30,781

7.8%

Geothermal

(hydrothermal)

0.033 5.7 0.6% 2 156 1.6%

Biomass (wood)

21

62

34.4%

124

342

36.4%

Total

9,063

155,457

5.8%

20,912

321,401

6.5%

Using the Techno-Economic Renewable Energy Potential on Tribal Lands report, NREL created the

Tribal Energy Atlas. This atlas is an interactive tool that allows individual Indian tribes to evaluate and

estimate the renewable energy resources within the tribe's lands. The atlas also includes important

energy infrastructure information, such as transmission line locations, pipeline locations, other energy

generation, and certain market information.

In both the geospatial and techno-economic analyses, NREL has defined the following renewable

energy resources in terms of both how they are generated and how they can be used or applied:

Biopower: Types of biomass include wood from various sources (beetle kill, slash, lumber waste),

agricultural residues, animal and human waste (methane), and municipal solid waste and landfill gas.

Most biopower plants use direct-fired systems to generate electricity from biomass. They burn

bioenergy feedstocks directly to produce steam. This steam drives a turbine, which turns a generator

that converts the power into electricity. In some biomass industries, the spent steam from the power

plant is also used for manufacturing processes or to heat buildings. Such combined heat and power

systems greatly increase overall energy efficiency. Anerobic digestion and waste to energy systems are

also included in biopower/biomass resources.

Geothermal: Geothermal technologies use heat from the Earth. Geothermal is a highly efficient method

of providing electricity generation. High-temperature geothermal is ideal for power plant production

levels, but low-temperature heat pumps can provide heating and cooling energy in any part of the

United States. Lower-temperature resources are

best suited for heat applications. Geothermal

technologies exist commercially for either small-scale (distributed) or large-scale (central) electricity

generation.

Hydropower: Hydroelectricity refers to electricity generated using the gravitational force of falling or

flowing water, called hydropower. Both large and small-scale power producers can use hydropower

technologies to produce clean electricity.

Concentrating Solar Power: Concentrating solar power (CSP) technologies use mirrors to reflect and

concentrate sunlight onto receivers that collect solar energy and convert it to heat. This thermal energy

can then be used to produce electricity via a steam turbine or heat engine that drives a generator.

While CSP offers a utility-scale, firm, dispatchable renewable energy option that can help meet demand

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

5

for electricity, it is most economical in the southwestern United States. Factors that influence project

economics are the cost of the technology, the quality of the solar resource, and the cost of the energy

being displaced. CSP systems can be successfully installed on landfills, brownfields, and greenfields,

with minimal disturbance to native vegetation and wildlife. Types of CSP systems include linear

concentrator, dish/engine, power tower, and thermal storage.

Solar PV: Photovoltaic (PV) technologies produce electricity directly from the energy of the sun. Small

PV can provide electricity for homes, businesses, and remote power needs. Larger PV systems provide

more electricity for contribution to the electric power system. PV technologies work in all parts of the

United States, but economics are dependent on technology cost, quality of solar resource, and cost of

energy being displaced. Flat plate is the most common PV array design, which uses flat-plate PV

modules or panels that can be fixed in place or designed to track the movement of the sun. An off-

grid, flat-plate solar PV system would be useful for remote locations or for self-sufficiency in the event

of a power interruption. Concentrator PV systems use less solar cell material than other PV systems

because they make use of relatively inexpensive materials such as plastic lenses and metal housings

to capture the solar energy shining on a large area and focus that energy onto a smaller area—the

solar cell.

Wind: Wind energy technologies use kinetic energy in wind for practical purposes such as generating

electricity, charging batteries, pumping water, and grinding grain. Most wind energy technologies can

be used as stand-alone applications, connected to a utility power grid, or even combined with a PV

system. Wind energy today is cost competitive in many locations throughout the United States. Utility-

scale wind consists of many turbines that are usually installed close together to form a wind farm that

provides grid power. Several electricity providers use wind farms to supply power to their customers.

Stand-alone turbines are typically used for water pumping or communications. However, homeowners

and farmers in windy areas can also use small wind systems to generate electricity.

Types of Projects

The literature is replete with definitions of the scale, uses and applications for renewable energy

resource projects. The following definitions are the more commonly used:

Commercial or Utility Scale: Commercial or utility scale renewable energy projects are typically greater

than 10 megawatts (MW, installed capacity). These projects typically sell power to utilities or other off

takers, which require interconnection to either the bulk transmission system or the "middle" grid.

Distributed Energy: Distributed energy generation projects are typically located within the distribution

grid, and can include rooftop solar, small wind, community solar or wind, energy storage, diesel/natural

gas generators, and microgrids (multiple generation technologies). Installed capacity for a project is

typically less than 10 MW and is intended to be used directly by single or multiple buildings (or homes).

These projects can be interconnected to the distribution system either "in front of" or "behind" the

customer’s meter(s). The following types of projects are considered "distributed energy" projects:

Community-Scale: Typically, a ground-mount system that serves multiple buildings, homes, or facilities.

Interconnection is typically "in front of" the meter but can be considered behind the meter if the utility

allows virtual or aggregate net metering.

Community Solar/Wind: Community solar (or solar gardens) or wind— sometimes referred to as shared

renewables—allows residents, small businesses, organizations, municipalities and others to "buy-in"

to the renewable energy project and receive credit on their electricity bills for the power produced from

their portion of a solar array, offsetting their electricity costs. While typically connected in front of the

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

6

meter, virtual net metering or aggregate net metering are required to allow for the project to reduce

customers' electricity costs.

Microgrids: These systems are localized load and generation resources (such as solar, wind, storage,

fuel cell, diesel or natural gas gen set) which normally operate connected to and synchronous with the

traditional grid but can disconnect and function autonomously as an island within the grid.

Rooftop residential or commercial solar or wind: Unlike the previously discussed projects, these

projects are located on individual buildings, homes, and facilities (such as water treatment plans,

wastewater plants, cell towers, etc.). Projects can also be co-located, such as solar canopies or small

ground mount. Interconnection is through the customer's meter, and these are almost all behind the

meter projects to take advantage of net metering.

Figure 1 is an example of a distributed energy

system.

Figure 1. Example of a distributed energy system.

Tribal Roles and Options

In the DOE Office of Indian Energy training modules and workshops, there is considerable discussion

about the roles tribes can perform in renewable energy development. These roles include project

company, resource/landowner, sponsor/developer, EPC contractor, operator, feedstock supplier,

product off-taker, lender, and tribal host. Table 3 provides a description of each type of role.

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

7

Table 3: Tribal Roles and Options in Renewable Energy Development

Title

Role

Project Company

Legal entity that owns the project, also called special purpose entity.

Resource/Landowner

Legal and/or beneficial owner of land and natural resources.

Sponsor/Developer

Organizes all the other parties and typically controls project development and

makes an

equity investment in the company or other entity that owns the

project.

EPC Contractor

Construction contractors provide design, engineering, and conduction of the

project.

Operator

Provides the day-to-day O&M of the project.

Feedstock Supplier

Provides the supply of feedstock (i.e., energy, raw materials) to the project

(e.g., for the power plant, the feedstock supplier will supply fuel)

Product Off-taker

Generally, enters into a long-term agreement with the project company for the

purchase of all energy.

Lender

A single financial institution or a group of financial institutions that provides a

loan to the project company to develop and construct the project and that takes

a security interest in all the project assets.

Tribal Host

Primary sovereign of project site.

Each role comes with its own set of benefits and risks. As a tribe undertakes its energy planning efforts,

one of the elements of such plans should include an assessment of the best and most appropriate

role for the tribe, given its circumstances, goals and objectives. One aspect of this evaluation should

also include the specific risks associated with the role and the type of project. These risks are outlined

in Table 4.

Table 4: Tribal Risks in Renewable Energy Development

Development Area

Risks

Development

• Poor or no renewable energy resource assessment

• Not identifying all possible costs

• Unrealistic estimation of all costs

• Community push-bask and completing land use

Site

• Site access and right of way

• Not in my backyard (NIMBY)/build absolutely nothing anywhere

(BANANA)

• Transmission constraints/siting new transmission

Permitting

• Tribe-adopted codes and permitting requirements

• Utility interconnection requirements

• Interconnection may require new transmission, possible NEPA

Finance

• Capital availability

• Incentive available risk

• Credit-worthy purchaser of generated energy

Construction/Completion

• EPC difficulties

• Cost overruns

• Schedule

Operating

• Output shortfall from expected

• Technology O&M

• Maintaining transmission access and possible curtailment

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

8

Project Ownership

Another element of planning should include whether a tribe should own, co-own or have a third-party

own the renewable energy project. As identified in the DOE Renewable Energy Project Development

Basics, each option has its own set of benefits, risks, responsibilities, and legal considerations.

Tribal Ownership: Tribes, including tribal owned enterprises, utilities, and other instrumentalities, that

directly own renewable energy projects will enjoy the primary benefits generated by such projects, such

as revenue generation or cost savings. Furthermore, these projects will not be subject to state

jurisdiction, taxation, or regulation. Nor are these projects likely to invoke the federal regulatory

scheme for leases or right of ways, as there is no third-party involvement. With the passage of the

Inflation Reduction Act, there is new legal support for tribal ownership of renewable and clean energy

projects. Direct ownership, however, also entails taking on all the risk and responsibility of developing,

financing, constructing, operating, and maintaining such projects.

Partnerships: Tribes can mitigate some of the risk and responsibility through partnerships with

developers or other investors to develop and own projects. For example, tribes can negotiate co-

ownership (or co-development) agreements that allocate risk and responsibilities across parties.

Third-Party Ownership: Third-party ownership has been the norm for utility scale projects, as these

projects require, among other things, expertise in substantial development activities, capital and

financing, tax equity investment, utility, and off-taker negotiations, construction, and operations. Third-

party leases will be subject to BIA approval (unless the tribe has approved leasing regulations under

the Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Home Ownership Act (HEARTH Act), thereby

invoking NEPA and other related environmental review requirements. But, with third-party ownership,

there is little risk to the tribe.

A note about tribal participation via tribal enterprises. As the BIA Handbook on Tribal Structures points

out, tribes can establish different types of enterprise structures—Section 17 federally chartered

companies, tribally chartered companies, or state-chartered companies. Tribes can also establish

other types of enterprises, such as tribal utilities, or leverage tribal housing authorities, to participate,

develop, own and or operate renewable energy projects. There are many legal and business reasons

to establish a separate tribal enterprise, including segregating legal and business risk, separating

business from politics, and being able to respond to market conditions and demands in a business

approach.

Current Market Conditions

Another major set of inputs or factors into renewable energy project planning is understanding and

incorporating market and industry information, including market opportunities and barriers,

technology opportunities and barriers, and access to transmission. Further, tribes should seek to

understand the role states and utilities play in tribal energy development projects, whether on or off

tribal lands.

Key Market Opportunities

Corporate Offtake Market: According to the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), almost 19 GW

of solar has been installed through 2022 for corporate procurement of solar power. SEIA estimates

that over the next 3 years nearly 27 GW will be installed through off-site projects. The American Clean

Power Association reports that 326 companies have purchased a total of 77 GW of clean energy (solar,

wind and storage). These numbers are expected to rise with the Inflation Reduction Act and continuing

reduction in costs.

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

9

Local Government Offtake Market: Like many corporations, local governments are also getting into

direct procurement to achieve their carbon reduction and other sustainability goals. In March 2020,

the World Resources Institute reported that U.S. local governments had signed 335 deals to procure

over 8 GW of renewable energy.

Federal Government Offtake Market: The federal government is the largest user of power in the

country. In December 2022, President Biden issued Executive Order 14057 "Catalyzing Clean Energy

Industries and Jobs Through Federal Sustainability." Under this EO, the federal government strives to

achieve 100 percent carbon pollution-free electricity by 2030. Carbon pollution-free is defined as

marine energy, solar, wind, hydrokinetic, geothermal, hydroelectric, nuclear, green hydrogen, and net

zero carbon produced fossil fuel resources. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 includes a preference

provision for tribal energy resources. In 2012, the DOE adopted a policy to implement this preference

provision and is now working with General Services Administration, and the Department of Defense to

update the preference policy to comport with the new EO.

Electrification of Energy—transportation and building decarbonization: Between the Bipartisan

Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), tens of billions of federal dollars (and

billions of private dollars) will be invested in the electrification of buildings, housing, industry, and the

transportation sector through electric vehicle charging stations, electrification of cars, commercial

vehicles and buses. As these sectors become electrified, more electricity demand will result, and the

need for more renewable energy and clean energy projects will rise.

State Laws and Regulations: Barriers and Opportunities

As some law review articles included in this literature review have pointed out, state law and regulation

and utility policies and practices have a determinative impact on tribal renewable energy projects on

tribal lands. While states do not typically have jurisdictional or regulatory authority over energy

development on tribal lands, projects on Indian lands may be impacted by state and local policies,

laws, and regulations. States exercise legal and regulatory control over public utilities related to retail

sales of energy products, as expressed in the Federal Power Act.

This legal and regulatory control extends to:

• how energy rates are set;

• interconnection standards;

• net metering requirements (if any);

• renewable or clean energy portfolio requirements (if any);

• utility renewable energy procurement and resource planning;

• distributed energy programs (if any);

• tax incentives or imposition of certain taxes; and

• siting and permitting of energy projects and infrastructure, such as transmission.

For tribes served by state regulated utilities, these state laws, regulations and policies will apply to

energy projects that serve the utilities or ratepayer located on Indian lands. Further complicating this

issue for some tribes, some states do not regulate certain types of utilities—such as public power

agencies and rural electric cooperatives. These unregulated utilities are free to set their own

requirements for energy projects on tribal lands.

On the other hand, over the last decade, states, cities, and other local governments have made a

substantial and uncontroverted shift toward energy policies that promote renewable energy, energy

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

10

efficiency, climate change mitigation, and sustainable adaptation to climate change impacts.

According to the Interstate Renewable Energy Council, many states have adopted laws or regulatory

policies related to distributed energy projects, such as net metering policies, interconnection rules and

standards, and community solar programs. The National Conference of State Legislatures reports that

over 35 states have now adopted renewable energy, or clean energy standards or goals. About half

of these states have also actively developed, promoted, and implemented greenhouse gas emissions

reduction plans, with an emphasis on market-based solutions. More states are also revisiting their

efforts to bring clean energy, energy efficiency, and sustainability programs to low-income and

vulnerable communities.

Moreover, many states may have tax incentives to build renewable energy projects, and other taxes

on business activities and income. The extent to which these taxes are applicable to projects located

on tribal lands will depend, among other things, on the type of tax, the project owner, and the buyer of

the power.

Finally, more specific information about state incentives, renewable energy programs, and utility

programs is maintained by the NC Clean Energy Center at North Carolina State, through the Database

of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency database.

Transmission and Distribution System Expansion and Upgrades

In the Energy Policy Act of 2005, Congress recognized the need to study, plan, and financially support

the expansion of the current bulk transmission system as a crucial ingredient to large scale

deployment of renewable energy utility scale projects. DOE is currently conducting two studies—the

National Transmission Needs Study and the National Transmission Planning Study—that seek to

identify opportunities and needs for transmission line expansion or capacity upgrades. In addition,

DOE is responsible to designate "National Interest electricity Transmission Corridors" throughout the

country. DOE is currently developing its process for such a designation.

Notwithstanding these major efforts to understand the transmission issues and identify potential

solutions, the renewable energy industry is still concerned about several related issues, including

permitting timeframes (it currently takes between 7 and 10 years to fully permit a new transmission

line) and interconnection processes and costs. FERC is currently undergoing transmission

interconnection reform efforts.

Because the distribution grid is the responsibility of retail electric utilities, sometimes subject to state

regulatory oversight, it is difficult to characterize the status of efforts to upgrade the distribution grid.

However, as discussed in the next section, the BIL has several billions of dollars for states, tribes, and

utilities to address distribution grid upgrades and resiliency efforts.

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

11

Part II: Federal Laws, Regulations, Policies and Guidance

The review of relevant federal laws and regulations applicable to tribal renewable energy development,

and various law review articles, identify five types of federal laws:

I. Federal Indian Laws and Regulations—Title 25 of the U.S. Code

II. Federal Environmental Laws and Regulations

III. Federal Energy Policy and Regulatory Laws and Regulations

IV. Federal Tax Laws

V. Federal Energy Programs Laws

Types I through Type IV of federal laws and regulations are reviewed in this section.

Type I: Federal Indian Laws and Regulations

The federal government regulates energy development on Indian lands in many ways and under

several federal statutes. Indian energy development statutes, such as the Indian Mineral Leasing Act

(IMLA), the Indian Mineral Development Act (IMDA), and the Indian Tribal Energy Self-Determination

Act (ITESDA), in addition to land development statutes, such as the General Right-of-Way (ROW) Act

and the Long Term Leasing Act (LTLA), are the more commonly known and invoked legal requirements

for the federal government and tribes to regulate and control renewable energy development on Indian

lands. The Secretary of the Interior is required to approve geothermal leases under the IMLA or the

IMDA. Leases for surface-based renewable energy projects, such as wind, solar, or biomass, are

approved under the LTLA, but may also need to receive mineral leases for the use of subsurface

minerals in the construction and operation of the surface project. And to the extent that transmission

lines, pipelines and or access roads are developed with the project, the Secretary is required to

approve ROWs for those facilities. Hydroelectric projects and associated transmission lines are

licensed and approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), as discussed in the next

section. Hydrogen pipelines will likely also be regulated by FERC.

These federal regulatory laws related to tribal lands and energy resources are grounded in the

Nonintercourse Act, which requires federal approval to convey interests in Indian lands. Courts have

regularly held that agreements to convey interests in lands that are not approved by the federal

government are invalid under federal law.

Long-Term Leasing Act of 1955

Under the LTLA, the Secretary is authorized to approve leases on tribal and allotted lands for certain

purposes, including agriculture, business, residential, public, religious, and educational. It is limited to

surface leasing, and thus is the federal law that controls leasing for solar, wind, and biomass energy

projects on tribal lands. While the default term for a lease is 25 years, plus two additional 25-year

renewal terms, many tribes have been authorized to enter in to leases up to 99 years. The LTLA

requires the Secretary to consider the following factors in approving a lease: (1) whether “adequate

consideration has been given to the relationship between the use of the leased lands and the use of

neighboring lands;” (2) “the height, quality, and safety of any structures or other facilities to be

constructed on such lands;” (3) “the availability of police and fire protection and other services;” (4)

“the availability of judicial forums for all criminal and civil causes arising on the leased lands;” and (5)

“the effect on the environment of the uses to which the leased lands will be subject.”

The LTLA is implemented through the BIA's surface leasing regulations. The regulations make the LTLA

applicable to “Indian land and government land, including any tract in which an individual Indian or

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

12

Indian tribe owns an interest in trust or restricted status.” Unless controlled by other statutory

authority, a lease is required when a person or legal entity (including an independent legal entity owned

and operated by a tribe) that is not an owner of the Indian land wants to lease Indian lands. For

example, a “Section 17” corporate entity that manages or has the power to manage the tribal land

directly under its federal charter or under a tribal authorization is not required to obtain a lease

approval through the BIA. As explained further below, a certified tribal energy development

organization (TEDO) is also not required to receive BIA approval for leases with tribes. However, a lease

between a tribal-owned entity or a partnership will have to be approved by the BIA.

For energy development purposes, the LTLA regulations do not apply to, among other land rights,

ROWs (they have their own regulations); mineral leases, prospecting permits, or mineral development

agreements; leases of water rights associated with Indian land, except to the extent the use of water

rights is incorporated in a lease of the land itself; or permits. Further, while option agreements,

development agreements, or temporary use permits—common in energy development—are not

considered leases under the regulations, the BIA requests such agreements be submitted for their

records and evaluation of whether the agreement is subject to the regulations.

The LTLA regulations were amended in 2013 to clarify several important federal and tribal interests in

leases. The regulations now explain that tribal law applies to leases of Indian lands, and the BIA will

comply with tribal law (including environmental, land use, and cultural resource protection laws) unless

contrary to federal law. State law only applies to the extent the tribe consents or has adopted state

law, or the state has jurisdiction pursuant to federal law. Furthermore, the regulations now include

specific disclaimers of applicability of state taxation—both property taxes and transaction taxes.

According to the regulations, “permanent improvements on the leased land, without regard to

ownership of those improvements, are not subject to any fee, tax, assessment, levy, or other charge

imposed by any state or political subdivision of a state. Improvements may be subject to taxation by

the Indian tribe with jurisdiction.” Additionally, activities under a lease conducted on the leased

premises are not subject to any fee, tax, assessment, levy, or other charge (e.g., business use,

privilege, public utility, excise, gross revenue taxes) imposed by any state or political subdivision of a

state. Activities may be subject to taxation by the Indian tribe with jurisdiction.

A major innovation in the revised LTLA regulations was the inclusion of subpart E for wind and solar

leases. There are two types of leases covered by this subpart: (1) wind energy evaluation leases

(WEELs), and (2) wind and solar resource (WSR) leases. A WEEL is a short-term lease that authorizes

possession of Indian land for the purpose of installing, operating, and maintaining instrumentation,

and associated infrastructure, such as meteorological towers, to evaluate wind resources for electricity

generation. WSR leases are leases that authorize possession of Indian land for the purpose of

installing, operating, and maintaining instrumentation, facilities, and associated infrastructure, such

as wind turbines and solar panels, to harness wind and or solar energy to generate and supply

electricity for resale on a for-profit or non-profit basis to a utility grid serving the public generally; or to

users within the local community (e.g., on and adjacent to a reservation). However, if the tribe itself

will conduct wind and solar resource activities on its own tribal lands, then the tribe does not need a

WEEL or WSR lease. This subpart does not cover biomass or waste-to-energy projects as those projects

are subject to subpart D (business leases).

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

13

In addition to the general provisions in the LTLA regulations, subpart E contains several requirements

for a WSR lease, including that the lease itself must include:

1. the tract or parcel of land being leased;

2. the purpose of the lease and authorized uses of the leased premises;

3. the parties to the lease;

4. the term of the lease;

5. the ownership of permanent improvements and the responsibility for constructing, operating,

maintaining, and managing WSR equipment, roads, transmission lines, and related facilities;

6. who is responsible for evaluating the leased premises for suitability, negotiating power

purchase agreements, transmission, and purchasing, installing, operating, and maintaining

WSR equipment;

7. payment requirements and late payment charges, including interest;

8. due diligence requirements;

9. insurance requirements;

10. bonding requirements; and

11. indemnification of the United States and the tribe.

Additional requirements include commencement of construction within two years, or the lessee must

provide a reason for delay and continue to make progress; submission and approval of a resource

development plan; ownership of improvements upon lease termination; fair market value

compensation or waiver by the tribe; and dispute resolution and remedies.

Because approval of a surface lease is considered a major federal action under the National

Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), it is subject to the regulatory review process required under NEPA

and other environmental review laws, listed here. Thus, the BIA cannot decide on the lease until the

environmental review process is complete. Another innovation in the LTLA regulations is related to

these environmental review requirements: per the regulations, the BIA “will adopt environmental

assessments and environmental impact statements prepared by another federal agency, Indian tribe,

entity, or person under 43 CFR 46.320 and 42 CFR 1506.3, including those prepared under 25 U.S.C.

4115 and 25 CFR part 1000, but may require a supplement.”

Prior to submitting a renewable energy project surface lease to the BIA for regulatory review and

approval, tribes should review the BIA checklist for approving leases so they have a sound

understanding of the information and steps the BIA requires. While not necessary under the

regulations, a tribe might want to request a certified appraisal through the Appraisal and Valuation

Services Office (AVSO). This appraised value may be able to assist both the tribe and the BIA with

verifying the fair market value of the compensation proposed in the lease.

Long-Term Leasing Act Amendments—HEARTH Act

The HEARTH Act, passed in 2012, also allows tribes to take control of leasing tribal lands for energy

development. The HEARTH Act amended the LTLA to allow tribes to petition the Secretary to approve

tribal leasing regulations for surface leases on tribal trust lands. If approved, the tribe no longer needs

secretarial approval of leases entered under the tribe’s leasing regulations. As with Tribal Energy

Resource Agreements (TERAs), the tribe does not need to meet any NEPA requirements for leases, but

the tribe’s leasing regulations do have to include an environmental review process that complies with

the statute. Unfortunately, the HEARTH Act does not apply to allotted lands or subsurface leasing.

The Secretary is required to approve tribal leasing regulations if those regulations are consistent with

the Secretary’s leasing regulations and incorporate an environmental review process that includes

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

14

evaluation of significant environmental impact, notice and opportunity to comment, and response to

comments.

The BIA has not issued regulations for the implementation and administration of the HEARTH Act, but

it has published the requirements and process for approving HEARTH Act tribal regulations in its

department manual.

As of the date of this review, over 100 tribes have applied for and received

approval of their leasing regulations, including seven providing wind and solar leasing authority.

Right-of-Way Acts

The General Right-of-Way Act was enacted in 1948 to provide the Secretary with broad authority to

enter into ROWs on Indian lands for all purposes. Previously enacted in the early 1900s, specific

purpose ROW laws remained in place and there was no intent to repeal ROW authorities under the

Federal Power Act (FPA). The 1948 Act grants general authority to approve ROWs, subject to conditions

set by the Secretary and with consent and approval of the tribe. Just compensation is required. The

Secretary must also issue rules and regulations for the approval of ROWs.

The ROW regulations were updated in 2015 and seek to create uniform regulations to harmonize the

regulatory process for all the operative ROW laws. For energy development purposes, the ROW

regulations cover transmission and distribution lines, access roads, and pipelines. Like the LTLA

regulations, the ROW regulations contain provisions regarding the applicability of tribal law, tribal

jurisdiction, and tribal taxation, as well as the inapplicability of state jurisdiction and state taxation. As

with leasing approvals, tribes should review the BIA checklist for approving easements on Indian lands.

A tribe may request an appraisal from the AVSO to verify fair market value of the proposed

compensation for the easement.

Tribal consent is required before the Secretary can grant an ROW, and the common practice now is for

tribes to negotiate an easement agreement between the tribe and the grantee that contains provisions

related to compensation, tribal governing law, jurisdiction, taxation, dispute resolution, and other

terms and conditions related to the use of the easement area. These agreements also usually contain

a provision that the easement agreement will be incorporated into the ROW grant, thereby providing a

federal remedy and enforcement for the easement terms.

Contracts Act

A little known and often overlooked federal law that also requires the approval of certain agreements

related to Indian lands is the Contracts Act. Originally enacted in 1871, the Contracts Act was last

amended in 2000 to better clarify other types of agreements with Indian tribes that must be approved

by the Secretary. The Contracts Act requires that any agreement that encumbers Indian lands for a

term of more than seven years is subject to

the Secretary’s approval. The statute does not define the

term “encumber” or “encumbrance,” and the regulations define the types of

contracts terms by what

they are or are not. But in the context of energy projects, this law might apply when a mortgage or

security interest is placed on the energy leasehold interest.

Indian Mineral Development Act of 1982

For geothermal projects, the IMDA is the applicable federal law. The IMDA is intended to create

flexibility and give tribes more opportunity to participate directly in mineral mining and development

on tribal lands:

Any Indian tribe, subject to the approval of the Secretary and any limitation or provision

contained in its constitution or charter, may enter into any joint venture, operating, production

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

15

sharing, service, managerial, lease or other agreement, or any amendment, supplement or

other modification of such agreement (hereinafter referred to as a “Minerals Agreement”)

providing for the exploration for, or extraction, processing, or other development of, oil, gas,

uranium, coal, geothermal, or other energy or nonenergy mineral resources (hereinafter

referred to as “mineral resources”) in which such Indian tribe owns a beneficial or restricted

interest, or providing for the sale or other disposition of the production or products of such

mineral resources.

In addition to the statutory leasing authorities, the IMDA regulations govern the approval of mineral

agreements to ensure tribal or individual Indian mineral owners enter into mineral agreements

consistent with the purposes of the IMDA. Key regulatory provisions include but are not limited to:

• making sure all environmental studies are completed under NEPA, the National Historic

Preservation Act (NHPA), the Archaeological and Historic Preservation Act, and the American

Indian Religious Freedom Act;

• due diligence related to corporate qualification of the lessee; and

• the multi-bureau responsibilities for the BIA, Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Office of

Surface Mining, Reclamation, and Enforcement, and Minerals Management Service (now the

Office of Natural Resources Revenue).

Even though mineral agreements are the product of negotiation between the tribe and potential

developer/lessee, the IMDA regulations nonetheless create requirements for the form of contract and

required elements. Every agreement is required to include (1) identification of parties; (2) duration and

term; (3) indemnification; (4) obligations; (5) disposition of production; (6) payment and compensation;

(7) accounting and valuation; (8) limitations on assignments; (9) bonding and insurance; (10) audits;

(11) dispute resolution; (12) force majeure; (13) termination or suspension; (14) nature and schedule

of activities; (15) reporting production; (16) abandonment, reclamation, and restoration; (17)

unitization; (18) protection from drainage and unauthorized taking; and (19) recordkeeping.

For geothermal leases and projects subject to the IMDA and its implementing regulations, the BIA

follows the Fluid Minerals Handbook and the BIA and BLM have segregated their regulatory and

oversight responsibilities through the “Onshore Energy and Mineral Lease Management Interagency

Standard Operating Procedures,” adopted in 2013. Furthermore, Section 3102 of the Energy Act of

2020 established a program to improve federal permit coordination through the creation of a national

Renewable Energy Coordination Office (RECO). The RECO is intended to encourage collaboration

between federal, state, and tribal authorities, with the BLM serving as the

lead. It is unclear, though,

whether the RECOs will cover geothermal projects on Indian lands.

Indian Tribal Energy Self-Determination Act (Title V of the Energy

Policy Act of 2005)

Title V of the Energy Policy Act of 2005 created several new programs and authorities to support tribal

energy development, including DOE’s Office of Indian Energy Policy and Programs, Department of the

Interior programs, and the ability for tribes to enter into Tribal Energy Resource Agreements (TERAs)

with DOI. Additional provisions promote tribal energy development, including a provision that allows

federal agencies to give preference to tribes in the purchase of electricity, energy products, and energy

byproducts; a provision granting authority to WAPA to buy firm power from tribal projects; a new tribal

energy loan guarantee program; other financial and technical assistance programs to promote energy

development; and a provision in Title II that creates a double credit for the federal renewable energy

standards for the purchase of renewable energy power from projects located on tribal lands.

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

16

Tribal Energy Resource Agreements

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 was the first federal law to include true self-governance provisions over

tribal energy development. The Indian Tribal Energy Development and Self-Determination Act

authorized the formation of TERAs, defined as agreements between a tribe and the Secretary to

authorize the tribe or certified TEDO to enter into leases and business agreements for the exploration,

extraction, or processing of energy mineral resources; or the construction or operation of electricity

production, generation, transmission, or distribution facilities, or facilities to process or refine energy

resources. Congress intended to promote complete tribal control over leases, business agreements,

and ROWs for renewable energy and energy minerals, transmission and distribution lines, and

pipelines.

If a tribe enters into a TERA, then leases, business agreements, and ROWs that serve an energy project

on tribal lands will not require the Secretary’s approval as long as the lease, agreement, or ROW is for

less than 30 years. Because there is no federal approval of leases or ROWs, tribes also avoid NEPA

requirements, although tribes must have a substitute environmental review process compliant with

the statute’s requirements.

Notwithstanding this powerful tool for energy self-governance, no tribe has yet to negotiate and enter

into a TERA. This is in large part because prior to 2018, when the TERA provisions were amended, the

BIA’s regulations and process for applying for and receiving approval for a TERA were too onerous,

expensive, and lengthy. In addition, there were multiple unanswered—and unanswerable—questions

about the allowed scope of a TERA (whether it includes the BLM functions and the definition of

"inherent federal functions" that could not be delegated to tribes, for example), the cost to implement,

the tribal qualifications to administer the TERA, and the scope of the Secretary’s trust responsibility.

While some of these issues were resolved through the recent amendments, many important questions

still linger.

Certified Tribal Energy Development Organizations

The 2018 amendments did create a new provision, though, that would allow a “certified” TEDO to

obtain an energy resource lease or ROW from a tribe without a TERA or without the Secretary’s

approval. A “tribal energy development organization” is defined as “any … business organization that

is engaged in the development of energy resources and is wholly owned by an Indian tribe,” or “any

organization of two or more entities, at least one of which is an Indian tribe.” The BIA enacted new

regulations in 2019 to implement these new provisions. Under these regulations, a certified TEDO

meets certain requirements, including that the TEDO must be majority owned and controlled by one or

more tribes, is chartered under tribal law and subject to the tribe(s) jurisdiction, and the projects are

located on the lands of the tribe(s). Once certified by the BIA, the tribe and its TEDO can negotiate and

enter into energy resource agreements without BIA approval.

The TEDO designation is one of the few authorities that promote the partnership of tribes with each

other and with non-tribal energy companies. TEDO designation has multiple benefits, including, as

noted above, the ability to enter leases with a tribe (or tribes) without either BIA approval or the need

for TERA or HEARTH Act leasing regulations. Additional benefits include access to federal grant

programs and the tribal energy loan guarantee program. To date, one tribe has successfully been

approved for TEDO designation.

Type II: Federal Environmental Laws

Several other federal environmental statutes also apply to energy project development on Indian

lands. These laws range from overall environmental review to laws specific to air, water, waste, and

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

17

endangered or protected species. These environmental laws are applicable to Indian tribes and tribal

lands either because of the federal approval of action related to the renewable energy project or

because of the generally applicable nature of the law.

The National Environmental Policy Act

When tribes must obtain the Secretary’s approval for leases or ROWs, or when tribes receive financial

assistance such as loans or grants, these approval requirements trigger NEPA, as they are considered

a “major federal action” under the Council on Environmental Quality’s (CEQ) NEPA regulations. Other

federal actions, such as Clean Air Act (CAA) or Clean Water Act (CWA) permitting, BLM or U.S. Forest

Service permitting or approvals, or other federal agency actions that may be required for a particular

tribal renewable energy project, will also of course trigger NEPA. Of particular interest, though, is the

appropriate role of NEPA on tribal lands and the role tribes can, and should, play in the federal NEPA

process.

The EPA has summarized the NEPA review process as follows:

Categorical Exclusion (CATEX). A federal action may be "categorically excluded" from a detailed

environmental analysis when the federal action normally does not have a significant effect on

the human environment (40 CFR 1508.1(d)). The reason for the exclusion is generally detailed

in NEPA procedures adopted by each federal agency.

Environmental Assessment/Finding of No Significant Impact. A federal agency can determine

that a CATEX does not apply to a proposed action. The federal agency may then prepare an

Environmental Assessment (EA). The EA determines whether or not a federal action has the

potential to cause significant environmental effects. Each federal agency has adopted its own

NEPA procedures for the preparation of EAs. See NEPA procedures adopted by each federal

agency.

If the agency determines that the action will not have significant environmental impacts, the

agency will issue a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI). A FONSI presents the reasons why

the agency concluded that there are no significant environmental impacts projected to occur

upon implementation of the action. If the EA determines that the environmental impacts of a

proposed federal action will be significant, an Environmental Impact Statement is prepared.

Environmental Impact Statements (EIS). Federal agencies prepare an EIS if a proposed major

federal action is determined to significantly affect the quality of the human environment. The

regulatory requirements for an EIS are more detailed and rigorous than the requirements for

an EA.

The EIS process starts with the agency publishing a notice of intent in the Federal Register.

The notice of intent informs the public of the upcoming environmental analysis and describes

how the public can become involved in the EIS preparation. This notice starts the scoping

process, which is the period in which the federal agency and the public collaborate to define

the range of issues and potential alternatives to be addressed in the EIS.

A draft EIS is published for public review and comment for a minimum of 45 days. Upon closing

of the comment period, agencies consider all substantive comments and, if necessary,

conduct further analyses. A final EIS is then published, which provides responses to

substantive comments. Publication of the final EIS begins the minimum 30-day wait period, in

Tribal Renewable Energy Development

Literature Review

18

which agencies are generally required to wait 30 days before making a final decision on a

proposed action.

EPA publishes a notice of availability in the Federal Register, announcing the availability of

both draft and final EISs to the public.

The EIS process ends with the issuance of the Record of Decision (ROD). The ROD explains the

agency's decision, describes the alternatives the agency considered, and discusses the

agency's plans for mitigation and monitoring, if necessary.

As described next, there is no doubt tribes have the inherent authority to regulate and control

development on tribal lands. This control and regulation necessarily include the right, authority, and

presumably the obligation, to conduct a review of the potential impacts—environmental and

otherwise—of development occurring on tribal lands. In the context of a federal decision to approve

such development, and thus the federal requirement to comply with NEPA, federal agencies can, and

should, defer to tribes on environmental review and impacts analysis. This approach is almost certainly

necessary if the principles of respect for tribal sovereignty, not to mention expedited permitting and

improved efficiencies of federal approvals, are going to be accomplished.

Under current CEQ NEPA regulations, tribes can be designated as co-lead or cooperating agencies in

the NEPA process. To promote efficiencies, agencies are required to reduce excessive paperwork and

delay by eliminating duplication with state, tribal, and local procedures, by providing for joint

preparation of environmental documents where practicable per § 1506.2 of the CEQ NEPA

regulations. This language provides clear support for a federal agency to accept, adopt, or otherwise

use an environmental analysis prepared by a tribe as a co-lead or cooperating agency for a lease or

ROW that must be approved by the Secretary.

Consistent with the NEPA regulations, DOI’s own NEPA regulations also allow for the adoption of tribal

environmental review documentation. The regulations provide that “an existing environmental analysis

prepared pursuant to NEPA and [CEQ] regulations may be used in its entirety if the responsible official

determines, with appropriate supporting documentation, that it adequately assesses the

environmental effects of the proposed action and reasonable alternatives.”

For purposes of approving leases on tribal lands, the BIA has developed “other federal procedures”

for adopting tribal environmental documents. Under the Indian leasing regulations, the BIA will adopt

environmental assessments and environmental impact statements prepared by another federal

agency, Indian tribe, entity, or person under 43 CFR 46.320 and 42 CFR 1506.3, including those

prepared under 25 U.S.C. 4115 and 25 CFR part 1000, but may require a supplement.

National Historic Preservation Act

Every federal agency must consider the effect of any undertaking (a federally funded or assisted

project, such as lease or ROW approvals for projects on Indian lands) on historic properties. "Historic

property" is any district, building, structure, site, or object that is eligible for listing in the National

Register of Historic Places because the property is significant at the national, state, or local level in