2O2O

RESEARCH TEAM

THE

This study is a product of the collaboration and vision of multiple people.

Led by researchers from the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce and Exploration Group:

Joanna McCall

Coordinator of Applied Research,

Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce

Barrett Smith

Coordinator of Applied Research,

Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce

Jacob Wunderlich

Director, Business Development and Applied Research,

Exploration Group

The Music Industry Report 2020 includes the work of talented student interns who went

through a competitive selection process to become a part of the research team:

Alexander Baynum

Belmont University

Kate Cosentino

Belmont University

Patrick Croke

University of Virginia

Shruthi Kumar

DePaul University

Isabel Smith

Elon University

In addition, Aaron Davis of Exploration Group and Rupa DeLoach of the Nashville Area

Chamber of Commerce contributed invaluable input and analysis. Cluster Analysis and

Economic Impact Analysis were conducted by Alexander Baynum and Rupa DeLoach.

2

3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Letter of Intent

Aaron Davis, Exploration Group

and Rupa DeLoach, The Research Center

Executive Summary

Introduction

How the Music Industry Works

Creator’s Side

Listener’s Side

Facets of the Music Industry Today

Traditional Small Business Models, Startups, Venture Capitalism

Software, Technology and New Media

Collective Management Organizations

Songwriters, Recording Artists, Music Publishers and Record Labels

Brick and Mortar Retail Storefronts

Digital Streaming Platforms

Non-interactive Digital Services, Radio

Touring, Booking, Venue Management, Music Festivals and Live Music Production

Merchandise

Music Education

Synchronization Licensing

The Impact of the Music Industry

Sector and Cluster Analysis

Economic Impact and Contribution Analysis

Large Musical Events

Independent Venues

Diversity and Inclusion

Evaluation of Trends by Genre in the Nashville Region

Alternative/Indie

Christian and Gospel

Classical

Country

EDM/Electronic

Folk/Americana

Hip-Hop and Rap

Jazz

Latin

Musical Theatre

Pop

Punk, Emo, Hardcore and Metal

Rock

Singer/Songwriter

Soul, R&B and Blues

All Genres

5 - 6

7 - 23

25 - 27

29 - 34

36 - 78

80 - 99

101 - 143

4

Music Industry Workforce Assessment

Workforce Category #1: Studio / Performing Musicians, Recording

Artists, Vocalists, Producers, DJs

Workforce Category #2: Songwriters, Composers, Lyricists, Arrangers,

Conductors, Bandleaders

Workforce Category #3: Live Music, Non-Technical Occupations:

Concert Promoter, Talent Buyer, Booking Agents, Tour Manager, Music Festival

Operations, Venue Manager, Venue Operations, Artist Hospitality

Workforce Category #4: Live Music, Technical Occupations: Sound

Engineering Technicians, Studio Maintenance, Live Sound,

Engineer, Instrument, Production, Audio, Equipment Technicians,

Lighting and Production Design, Rigging, Live Crew

Workforce Category #5: AM/FM Radio, Internet Radio, Satellite Radio

Workforce Category #6: Music Education, Music Therapy

Workforce Category #7: Public Relations, Journalism, Social Media, Creative Agency,

Artist Manager, Business Manager

Workforce Category #8: Financial Planning, Consulting, Accounting, Banking,

Entertainment Law

Workforce Category #9: Music Publishing Creative Operations (Sync Pitching,

Marketing, Talent Scouting, etc.), Sync Licensing, Music Supervision,

Advertising, Catalog Administration, Rights Management, Metadata

Organization, Performance or Mechanical Copyright Society Operations,

Record Label Operations (A&R, Marketing, Radio Promotion, Distribution,

Human Resources, etc.)

Workforce Category #10: Technology Development, Software Engineering,

Digital Service Platform Operations, Research Analytics,

Record Label Operations (A&R, Marketing, RadioPromotion, Distribution,

Human Resources, etc.)

Workforce Category #11: Brick and Mortar Music Retail Operations

The Finale

A Look Back

Conclusion

Final Thoughts from the Music Industry

Resources

Acknowledgements

Glossary

Endnotes

Other Works Cited

Appendices

144 - 214

216 - 223

225 - 226

227 - 231

232 - 235

236 - 239

240

240

5

LETTER OF INTENT

Aaron Davis, Co-founder and CEO of Exploration Group, and Rupa DeLoach, Vice President of

Research at the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce:

Wendell Berry writes: “It may be that when we no longer know what to do we have come to our real

work and that when we no longer know which way to go we have come to our real journey. The mind that

is not baffled is not employed. The impeded stream is the one that sings.” In our inaugural publishing of

the Music Industry Report, we hold to this sentiment.

Exploration has teamed up with the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce and several leading trade

associations and educational institutions to study the state of the Music Industry, its individual sectors,

and its functioning as a collective body. In our research we’ve analyzed how folks worked in the past and

how their efforts have been affected by COVID-19.

Chip and Dan Heath in their bestselling book, Switch, inform us: “data are just summaries of thousands

of stories—tell a few of those stories to help make the data meaningful.” That is just what the research

team has done in the compelling narrative within this study.

The Music Industry Report 2020 was conducted in three main parts: 1) in depth interviews with

individuals to learn how their businesses and organizations have been personally affected 2) detailed

surveys of large groups of members of our community to garner a broader perspective 3) economic

impact data, demographic statistics and cluster analysis of the Nashville, Tenn. region with other music-

centric areas. This method gave us a comprehensive understanding of some of the opportunities and

challenges the music industry faces.

So as you read, we ask you to witness the dynamic and innovative nature of the music industry and the

opportunities it presents to both creatives and entrepreneurs in addition to the economic power of the

music industry here in the Nashville Region (in terms of jobs, monetary impacts and what it means to the

regional and national landscape). We believe this report will demystify how the music industry works and

offer insights on how recession and pandemics can be navigated by those most critical to the industry

yet most vulnerable.

Thank you to the contributors and project leads who helped produce this study and all of the folks who

made it possible. To properly analyze such a large and complex industry was no easy task; the results

stand as a testament to the merit, grit, and perseverance of everyone in this industry.

6

In addition to anticipated findings from this report, we took into consideration a few overarching

principles. It has been important for us to embody them in order to put our best foot forward and in

order for our work to stand in full integrity. We are committed to truthful reporting on the findings

of this research. Transparency of data means making all findings available in addition to a complete

methodology. We are also committed to a spirit of collaboration and mutual benefit. This project would

not be possible without the collective effort of the countless individuals and organizations who comprise

this industry.

The high-level findings of the study illuminate that Nashville is not only where the world comes to

record and listen to music, but where music comes to do business. Data suggests that our resolve must

be strengthened to address the sustainable viability of independent venues in addition to issues of

compensation and inequity that were further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic—deficits in social

programs available for musicians and staff, in gender and racial bias and in a balanced revenue share

for creators. We also learned there is much work to do in educating all participants in the music supply

chain regarding the value and importance of metadata.

Finally, we all agree (whether its among those in the music industry or the wider public) that music is

worth fighting for, that it enriches our daily lives and keeps our souls intact. Now, more than ever, we can

meet the challenges and opportunities uncovered by this research in Nashville and around the world.

We are optimists. We believe the best is yet to come. We view the great challenges of our times as

opportunities to work together, utilizing our collective intellect in order to derive creative and adaptive

solutions to more effectively reach our common goals. We are grateful and have high regard for the

many individuals who share this belief and have contributed so much in helping us produce the Music

Industry Report 2020.

We’ll see you down the road. This is how the music business works.

Aaron Davis

Co-Founder and CEO

Exploration Group

Rupa R DeLoach

Vice President of Research

Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce

7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Industry follows art. Creation is the nucleus of human experience and music is the communication of

human experience over sound waves from one mind to another. It is the lullabies you sang from birth,

the way you learned the alphabet, the mosh pit you joined when you were thirteen, the rst CD you ever

bought, the guitarist who shook your hand, the long rides home listening to your favorite radio station,

the symphony orchestra, the gospel choir, the bass drop at Coachella.

A music industry is what happens when “the roadies take the stage, pack it up and tear it down,” to

quote Jackson Browne. It is the money changing hands before the crowd rolls in. It is the royalties and

commissions and licensing fees and salaries of over 1.9 million people who exist to facilitate an ex-

change of value between music creators and listeners.

The Music Industry Report 2020 establishes market research exploring innovation and change driving

growth in the music industry with an emphasis on the impacts of COVID-19.

METHODOLOGY

Our premise is to encourage the music industry to represent itself.

More than one hundred music

industry experts shared their time

and insights over video conference

interviews between March and

September of 2020. Their words

informed two largescale online

surveys to 2,589 combined

recipients: a 98-question survey

to the Music Industry investigating

workforce dynamics (with a 95%

condence level and +/-2.19%

margin of error), and a 50-question

survey to Music Consumers (with

a 95% condence level at 4.08%

margin of error). Survey to the Music

Industry skews by 1.0% toward males,

Consumers’ Survey by 10.0% toward

females; Music Industry survey by

13.7% toward whites, Consumers’

survey by +6.7% toward whites.

8

Eighty-seven percent of respondents to the Survey to the Music Industry indicate they live in the United States;

55.3% are from the Nashville Metropolitan Statistical Area. 77.2% of respondents to the Consumers’ Survey indi-

cate they live in the United States; 48.1% are from the Nashville Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Three focus groups of 6-12 people each helped to rene topics of considerable importance and address demo-

graphic limitations from the surveys:

LIVE MUSIC

PROFESSIONALS

ARTISTS

SONGWRITERS

MUSICIANS

PRODUCERS

Data sets from federal, state and private sector resources garnered an in-depth picture of direct, music-related

employment specic to the Nashville region then to the broader USA.

The regional and national employment gures were used to calculate the economic impact of the music industry

through input-output modeling using the IMPLAN economic impact software. IMPLAN is an economic impact

modeling software that can take direct inputs of a given sector and calculate the total economic impact of that

sector on the entire economy in terms of direct effect (direct trade ows within the industry or industries involved),

indirect effect (capturing the impact of the supply chain or value chain) and the induced effect (the impact of

income and wages on spending). Employment was used as the baseline input variable to calculate the economic

contribution and impact analysis for this report.

The 2013 Music Study from the Nashville Chamber of Commerce incorporated employment and economic data

that included both Music and Entertainment Industries. Data tools at the time limited the ability to pull out a purely

music industry dataset. In 2020 data tools allow researchers to rene the data so that a purely music industry data

set could be delineated. This updated study includes both an assessment of the economic impact of the Music

and Entertainment Industry in 2019 for comparison with the impact as measured in 2013’s study as well as an up-

dated evaluation of the data examining the economic impact of the Music Industry exclusively.

Outside of primary data collected by the research team, occupational data used in the Workforce Assessment and

elsewhere throughout the report is also collected from both Economic Modeling Specialists Inc. (EMSI, a labor

market analytics rm) and Chmura Economics and Analytics (an applied economic consulting rm delivering ad-

vanced economic analysis). These rms utilize data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics directly to create analytics.

This report uses this data to examine over fty occupations identied as having all, or some, employment concen-

tration in the music industry. These occupations are broken up into eleven workforce categories based on similar

music industry activity.

DIVERSITY AND

INCLUSION

IN THE

NASHVILLE MUSIC

INDUSTRY

9

Key Music Industry-Centric Regions

Nashville MSA

EMSI data provides measurements in terms of retirement risk, racial and gender diversity per workforce group.

Chmura data provides information regarding historical employment growth, current employment, relative

concentration of employment, occupational unemployment, as well as median, entry level and experienced level

wages. Chmura data is also used to provide occupational employment projections based on two scenarios: one

where employment levels are taken at the most recently published quarter and historical patterns are applied to

this starting point without consideration of COVID-19; and another where the immediate effects of COVID-19 are

taken into account, oftentimes resulting in a sharp dip in employment. There is also an assumption of a vaccine that

is widely-spread by mid-to-late 2021. Accounting for all occupations and metrics provided for nine metro regions in

addition to the United States, the Music Industry Report 2020 includes over 12,500 data points.

Finally, to ensure a robust

understanding of current and recent

research and trends within the

industry, the research team conducted

a literature review and dove into

secondary qualitative research at the

onset of this report. This review and

examination of recent publications

centers on the music industry and

its component parts allowing the

research team to explore comparative

benchmarks, as well as gain insight

into what the industry looked like prior

to COVID-19 and how others project

it to evolve. Examples of this research

and selected literature is cited

throughout the study.

The Nashville MSA, given its high

concentration of music industry

activity, provides a logical starting

point from which to investigate the

global dynamics of the music industry.

Davidson

Wilson

Smith

Trousdale

Dickson

Robertson

Sumner

Macon

Rutherford

Cannon

Williamson

Cheatham

Maury

POPULATION

13,000,000 - 19,000,000

9,000,000 - 13,000,000

3,000,000 - 9,000,000

1,500,000 - 3,000,000

1,000,000 - 1,500,000

10

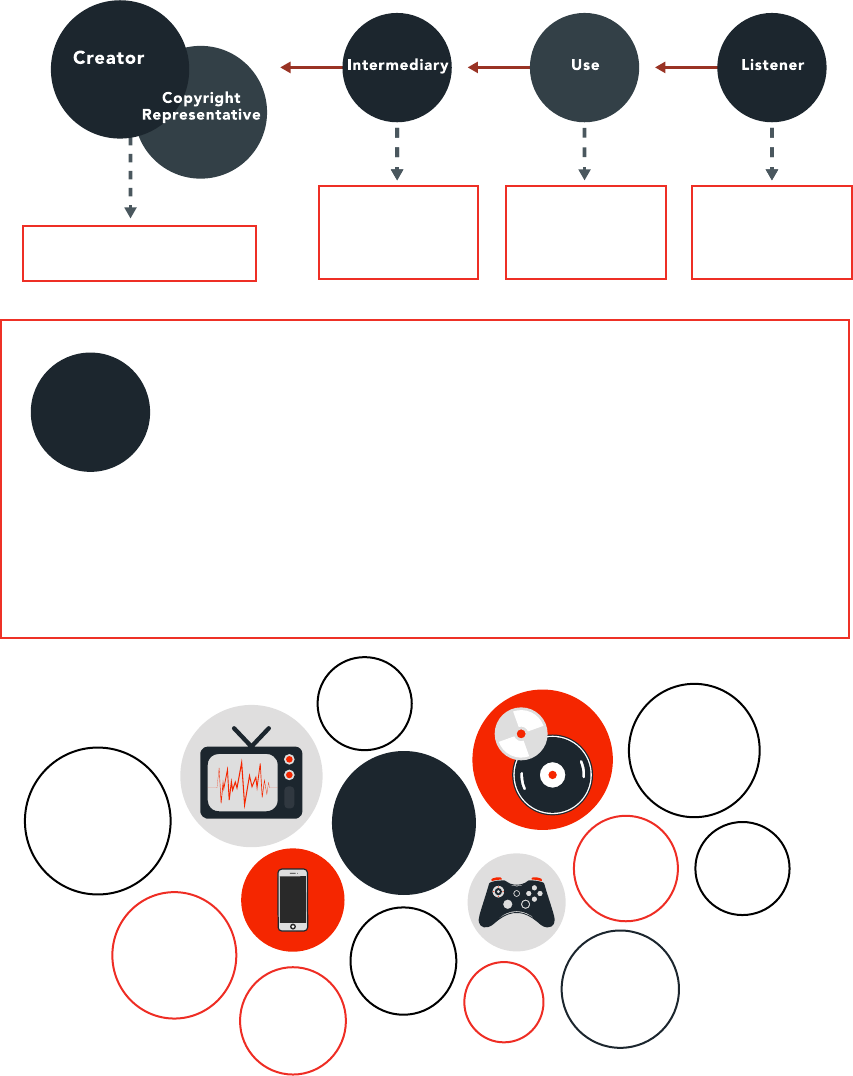

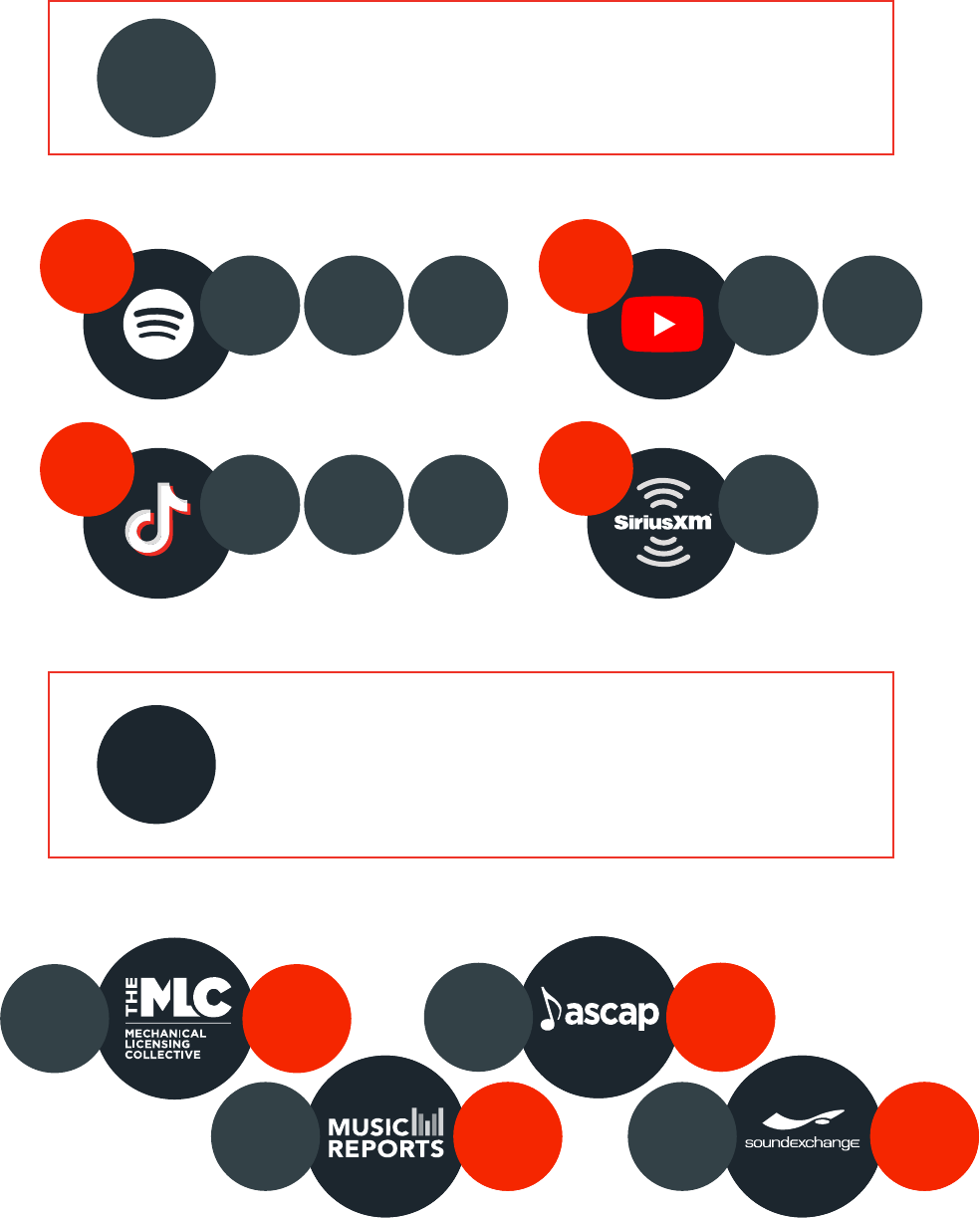

HOW THE MUSIC INDUSTRY WORKS

United States copyright law governs what you can and what others cannot do with creative expression xed in a

tangible medium. Any use of intellectual property by someone other than the copyright owner requires them to

obtain a license and pay royalties.

Two primary functions of the music industry:

1. Provide musical experiences to the Listener.

2. Return value to the music Creator.

From the Creator side, this value exchange operates as a function of the music creator’s rights and the authorization

of licenses for another party to use them. Copyright representatives help music creators better manage and exploit

their compositions and sound recordings. Intermediaries help license musical content to users, but can be bypassed

in some circumstances. Uses provide circumstances in which people can listen to music and create a royalty payment

owed to the music creator or copyright owner.

From the Listener side, music listeners create value with their time, attention and money. Uses monetize this

listener value and pay for the exploitation of a music creator’s rights in the form of a royalty. Intermediaries help

get this royalty from a music use back to the original creator or copyright owner. Outside of ticket revenue from live

performances, this is how creators generate income from their work.

Receives value in exchange

for exploitation of rights

Collects and

distrubutes

royalties generated

from uses

Monetizes value

from listener

and exploits

copyrights

Contributes value

in exchange

for access

to music

Creates

Musical

Content

Provides Copyright

Administration

and Management

Licenses

musical content

for use

Provides listener

access to

musical

experiences

Enjoys

musical

experiences

11

This full diagram below provides a basic picture of this combined exchange of value:

The music industry is constantly adapting to new developments in the ways people both listen to and create music,

but the essential relationship remains the same.

FACETS OF THE MUSIC INDUSTRY TODAY

Nashville is not only where the world comes to listen to music; it is also where music comes to do business.

Industry dynamics in the region exemplify and often inspire global trends.

Eleven facets detail the music industry’s current status. 1. Traditional Small Business Models, Startups and Venture

Capital; 2. Software, Technology and New Media; 3. Collective Management Organizations; 4. Songwriters,

Recording Artists, Music Publishers and Record Labels; 5. Brick and Mortar Retail Storefronts; 6. Digital Streaming

Platforms; 7. Non-Interactive Digital Services, Radio; 8. Touring, Booking, Venue Management, Music Festivals and

Live Music Production; 9. Merchandise; 10. Music Education and Therapy; and 11. Synchronization Licensing.

SMALL BUSINESS OWNERSHIP

43.3% applied for the Paycheck Protection Program; 84.2% were accepted.

Half of small business owners anticipate their companies bouncing back in 1 to 2 years.

78.7% of small business owners lost revenue since the onset of COVID-19.

REMOTE WORK

67.2% transitioned to remote work; of those just 36.4% say it decreased their prociency.

54.7% agree the music industry adapts well to new technology.

LIVESTREAMING

50.2% of consumers say a livestream is nowhere near the real experience.

82.8% of music creators performed a live stream between March and April of 2020.

Livestreaming was ranked #1 among prospective sources of non-live revenue.

RADIO

36% listen to AM/FM radio, second among listening options only to Spotify.

33.3% discover new music from AM/FM radio.

The following statistics are most noteworthy.

12

COPYRIGHT

MERCHANDISE

Consumers rank physical merch second among non-live actions that pay artists the most

money.

LIVE MUSIC

93% rank the music industry’s dependence on live music above seven on a scale of 1-10.

50.4% of recording artists have performed zero times since March 2020.

Bookings for live performances in 2021 are lower for 86.9% of respondents.

LISTENING OPTIONS

39.7% of consumers report listening to more music since the onset of COVID.

Most consumers listen to music at home (52.3%), in a car (31.5%) or at work (11.5%).

DIGITAL STREAMING

Spotify is the most popular listening option for all age groups surveyed.

74.9% of consumers subscribe to a music streaming platform.

An extensive music library is most valued in a digital streaming service by consumers.

EDUCATION

Only 21.6% rank the value of their degree above six on a scale of 1-10.

62.1% of music industry pros have at least a bachelor’s degree.

MUSIC CREATORS

73.5% of music creators surveyed are making less music because of COVID-19.

82.3% have lost scheduled gigs, studio work or residency; 40.5% have cancelled or postponed tours.

54.6% disagree that commercial charts are an effective metric for distributing royalties.

76.9% feel unprepared for The Mechanical Licensing Collective.

59% of respondents rank the importance of metadata between 1 and 8 on 1-10 scale.

95% of music creators surveyed own all or some of their music copyrights.

13

ECONOMIC & CLUSTER ANALYSIS

Industry clusters are groups of related businesses that function together creating a competitive hub sharing

common markets, occupational skills and technologies within a region. The music industry is a strong

traded cluster with global reach that imports and exports products, talent and services from throughout the

Nashville region to the rest of the world. Please note that cluster and economic impact analysis relies on

historical data. As such, this section does not contain reference to COVID-19; however, those impacts are

addressed in very real terms in the following section on independent music venues.

The Music Industry cluster, excluding its linkages in the Nashville Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA),

represents 16,298 jobs (2019) with average annual earnings of $81,521 or $66,358 (when averaging

without artist/performer wages). Direct music industry employment has increased by 29% in the region

since 2012 to 21,878 total jobs in 2019.

Nashville is third in the nation in terms of jobs in the music industry behind Los Angeles and New York.

The region has the highest location quotient of employment in the music industry of any MSA in the United

States. A location quotient (LQ) tells the amount of a region’s share of employment in a specic industry as

a percent of total national employment for that industry. Accordingly, the highest concentration of workers

with the skills specialized for the music industry are located in the Nashville Region.

Looking at the top ten MSAs in the U.S. for music industry jobs and job growth, over the ten-year period

from 2009 to 2019, the Nashville MSA ranks rst for net job growth and growth rate. Even in terms of

net job growth, the Nashville MSA had ve times the net job growth of Los Angeles and 200 times the

job growth of New York.

REGIONAL MUSIC AND ENTERTAINMENT ECONOMIC IMPACT ANALYSIS – 2013 VS. 2020

Economic impact analysis for the Nashville MSA determined that the Music and Entertainment Industry is

responsible for 80,757 jobs within the Nashville area offering employee compensation of $6.3 billion and

adding $9.9 billion to the local Gross Domestic Product (GDP) with a total economic impact of $15.6 billion.

Location Quotient Chart (2019 LQ & 10 Year LQ Growth)

NASHVILLE MUSIC INDUSTRY ECONOMIC IMPACT ANALYSIS – 2013 VS. 2020

Researchers utilized a stafng pattern matrix to determine music-related employment from all related industry

sectors that was further rened to calculate net music-related jobs by industry. In 2013, the music industry directly

contributed $2.1 billion to regional GDP with another $1.5 billion added through indirect and induced effect for

a total of $3.6 billion. This grew by $1.7 billion to $5.3 billion (an increase of 47%) in 2020.

Overall economic impact of the music industry in the Nashville MSA in 2020 is

$8.6 billion which represents an increase of $2.6 billion (43%) since 2013’s $6.1B.

USA MUSIC INDUSTRY ECONOMIC IMPACT ANALYSIS – 2013 VS. 2020

Total employment in the United States accounts for 2.8M jobs in 2020 growing by 137,000 jobs (an increase of 5.2%).

Overall economic impact of the music industry in the United States in 2020

is $514B which represents an increase of $43B (9.2%) since 2013’s $471B.

NOTE: While the studies have been published in 2013 and 2020 respectively, the values above represent 2012 and 2019 data.

1 - Direct

2 - Indirect

3 - Induced

Total

21,878

10,336

11,735

43,948

$1,618,928,267

$618,297,135

$653,351,180

$2,890,576,582

$3,199,613,641

$997,357,889

$1,084,013,965

$5,280,985,496

$5,018,186,861

$1,773,683,204

$1,848,075,502

$8,639,945,567

1 - Direct

2 - Indirect

3 - Induced

Total

17,008

8,050

9,149

34,206

Employment

Type Impact

$1,124,803,911

$440,562,035

$453,628,945

$2,018,994,891

Labor Income

$2,134,218,695

$722,116,710

$744,810,291

$3,601,145,697

Value Added

$3,470,329,912

$1,302,725,584

$1,277,102,742

$6,050,158,238

Output

2020

2013

1 - Direct

2 - Indirect

3 - Induced

Total

1,317,858

744,542

707,646

2,770,046

$88,521,039,359

$46,603,402,636

$39,399,976,293

$174,524,418,288

$138,795,206,869

$74,065,133,894

$65,373,681,654

$278,234,022,417

$265,132,048,545

$137,452,111,059

$111,452,143,903

$514,036,303,507

1 - Direct

2 - Indirect

3 - Induced

Total

1,193,864

760,405

678,851

2,633,120

Employment

Type Impact

$72,734,642,791

$42,845,166,299

$33,660,960,314

$149,240,769,403

Labor Income

$120,346,812,923

$69,361,232,400

$55,274,598,152

$244,982,643,475

Value Added

$245,617,257,298

$130,244,185,069

$94,779,115,567

$470,640,557,933

Output

2020

2013

14

INDEPENDENT MUSIC VENUES

Overall, independent music venues, represented by Nashville group the Music Venue Alliance, in Metro Nashville lost 72%

of their overall revenue and 73.5% of their employment. In 2019 independent music venues had a total economic impact

of $49.6 million in Davidson County. Because of COVID-19, the total economic effect to date is a loss of $35.7 million

dollars which represents a loss of $22.6 million in revenue to these independent music businesses. The impact on regional

employment is a net loss of 275 full time equivalent jobs which equates to $17.1 million in lost wages and a loss of $24.8

million to Davidson County’s Gross Domestic Product.

In the words of Chris Cobb, Nashville independent music venue

owner, this scenario created by COVID-19 is “Extinction Level!”

1 - Direct

2 - Indirect

3 - Induced

Total

74

11

16

102

$4,778,987

$878,929

$1,164,453

$6,822,368

$6,589,022

$1,472,797

$1,790,924

$9,852,744

$8,829,253

$2,257,887

$2,833,003

$13,920,143

1 - Direct

2 - Indirect

3 - Induced

Total

279

42

56

377

Employment

Type Impact

$16,689,824

$3,209,802

$4,042,515

$23,942,142

Labor Income

$23,036,243

$5,411,504

$6,217,820

$34,665,567

Value Added

$31,430,744

$8,353,173

$9,835,737

$49,619,654

Output

2020

2019

15

DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION

According to Economic Modeling Specialists, Inc. (EMSI), only 9% of music industry professionals in the

United States are Black or African American. This compares to 8% in the Nashville region. In the United States

approximately 13% of the population is Black or African American. This compares to approximately 16% in the

Nashville region.

#TheShowMustBePaused is a movement founded on social media by Brianna Agyemang, Atlantic Records, and

Jamila Thomas, Platoon, after the killing of George Floyd in Spring of 2020 to push for greater representation in

the music industry for Black people.

The research team conducted a focus group to examine the impacts of this event and ongoing diversity and

inclusion efforts in the city of Nashville.

Hiring and Job Creation: Diversity has to be a commitment at all levels, especially in management, in order for

the music industry to improve. It has to be built into the infrastructure of the music industry for it to last.

Intentionality: #BlackoutTuesday was key to opening the door regarding conversations about diversity in many

spaces. Yet, representation is still an issue.

Ownership: To ensure a more equitable industry, it is crucial for Black professionals to have access to ownership

of record labels, venues for Black creatives and places like the National Museum of African American Music.

Sustainable Opportunities: Creating sustainable and repeatable business opportunities and infrastructure for

creators is necessary for representation and inclusivity to endure.

Key Takeaways

Overall, there is momentum around diversity and inclusion in this moment. Therefore, there is a great need for

Nashville to decide what they want to do with the brand “Music City” and make a commitment to diversity. That

starts with creating spaces, having conversations and asking questions, funding individuals and groups, valuing

diversity and remembering music is best when everyone has a seat at the table.

16

EVALUATION OF TRENDS BY GENRE

IN THE NASHVILLE REGION

The Nashville region is well-known for country music. However, other burgeoning music scenes are

equally important to the cultural and economic landscape. The following information comes from both

the Music Consumer Survey and the Survey to the Music Industry.

Alternative / Indie

Christian & Gospel

Classical

Country

EDM/Electronic

Folk / Americana

Hip-Hop & Rap

Jazz

Latin

Pop

Punk / Emo / Hardcore & Metal

Reggae

Rock

Singer / Songwriter

Soul, R&B & Blues

38

8

16

35

9

28

21

22

8

35

20

9

46

39

43

50

13

21

42

11

40

34

23

9

48

25

12

51

42

58

26

15

12

55

5

32

15

19

5

43

8

3

35

44

39

The primary genre for

music creators (%)

Genre

Evaluation of Trends by Genre in the Nashville Region

A favorite genre to

listen to (%)

A favorite genre to

experience live (%)

17

Terminated an agreement

with an entity representing

me or my music.

Entered into an agreement

with an entity to represent me

or my music.

Had to take on an additional

job unrelated to music.

Had to take on an additional

job related to music.

Purchased new gear, audio

equipment and/or musical

instruments.

Devoted resources toward

building a home studio.

Cancelled or postponed

my tour.

AS A RESULT OF COVID-19, I HAVE...

18

200

100

0

IMPACTS OF COVID-19 PER GENRE

AS A RESULT OF COVID-19, I HAVE...

Loss of scheduled

gigs, studio work, or

residency.

Loss of revenue,

employment, or

benets.

Had to sell gear,

equipment,

or personal

belongings.

Participated in a

livestream concert for

no compensation.

Participated in a

livestream concert

for compensation.

Promoted my music

on Tik Tok.

Started a social

media campaign or

crowd-funding to raise

money.

Delayed a music

release.

19

300

200

100

0

20

MUSIC INDUSTRY

WORKFORCE ASSESSMENT

Many of the people who contribute to the music industry both directly and indirectly fall outside of

traditional, measurable categories. The following list accounts for a music industry workforce assessment

developed to harmonize data from this report’s Survey to the Music Industry with related occupational

groups from the Bureau of Labor Statistics classications.

STUDIO & PERFORMING MUSICIANS, RECORDING ARTISTS, VOCALISTS,

PRODUCERS AND DISC JOCKEYS

Total employment growth is down 5.1%. Nashville’s LQ is higher than any other comparable MSA.

53% of musicians surveyed hold multiple jobs.

79.4% of musicians surveyed have experienced unemployment since March; 96% due to COVID.

67.5% project their 2020 annual income will be at or below $36,000— a $10,000 drop from 2019’s average.

SONGWRITERS, COMPOSERS, LYRICISTS, ARRANGERS, CONDUCTORS, BANDLEADERS

Nashville has the third highest historical 10-year growth rate among comparable MSAs.

Wages in the Nashville MSA are lower than in all other comparable MSAs.

Nashville’s MSA is lowest of all music cities when it comes to gender diversity.

67.5% say COVID-19 has negatively impacted their mental health.

LIVE MUSIC, NON-TECHNICAL OCCUPATIONS: BOOKING, TOURING,

VENUE MANAGEMENT, ETC.

Nashville MSA’s LQ of agents and managers is the second highest behind L.A.

52.3% say their current work does not provide a comfortable living standard; 54.7% say it did in 2019.

96% surveyed are seeing less work; 43% have not been able to transition to remote work.

Nashville has the least racial diversity of all peer music cities in this workforce category.

LIVE MUSIC, TECHNICAL AND OPERATIONS OCCUPATIONS

By 2025, the Nashville region will have only ~40 more lighting technicians than it has today.

44.3% of those in lightning, audio and live production have been working in the industry for 21+ years.

22.3% surveyed do not have health insurance.

COVID-19 will decrease 2020 annual income for 93% of survey respondents.

RADIO

Nashville is the only MSA with positive 10-year employment growth.

Broadcast technicians make the 3rd highest annual median wage among comparable MSAs.

Radio employees surveyed are experiencing unemployment 14.7% below average.

54.6% maintained or increased their prociency with remote work.

21

MUSIC EDUCATION AND THERAPY

All MSAs show positive 10-year total employment growth for postsecondary music teachers.

Nashville has lost 57.2% of its recreational therapists over the past 10 years.

67.0%

of music educators and therapists surveyed have more than one job.

44% of music educators say their current occupations will not offer a comfortable living standard this year.

PUBLIC RELATIONS, JOURNALISM, SOCIAL MEDIA, CREATIVE AGENCY, ARTIST

AND BUSINESS MANAGERS

46.1% of survey respondents are between the ages 20-34.

19.5% surveyed are considering permanent relocation from their large urban center.

Survey responses project the amount of people making $0 - $12,760 will increase by 23% in 2020.

Unemployment is 19.6% lower than the 53.8% survey average.

FINANCIAL PLANNING, CONSULTING, BANKING, ACCOUNTING AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW

Most are salary-based employees or company owners, not freelancers.

Only 20% surveyed have experienced unemployment since March 2020, well below average.

86.4% were able to transition to remote work.

62.5% are seeing less work due to COVID-19.

MUSIC PUBLISHING AND RECORD LABEL OPERATIONS, SYNC LICENSING, CATALOG ADMIN,

COPYRIGHT MANAGEMENT

98.7% have at least some college education.

27.2% are newcomers to this occupation and have zero to ve years of experience.

Only 8% could not transition to remote work.

Unemployment is 25.6% below the survey average.

TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT, SOFTWARE ENGINEERING, DIGITAL SERVICE PLATFORMS,

RESEARCH ANALYTICS

74.4% of people have maintained or increased their prociency with remote work.

Negative mental health effects and unemployment due to COVID-19 are both lower than survey average.

37.3% are new entrants to this occupation with zero to ve years of experience.

45.8% believe COVID-19 will not affect their annual income for 2020.

BRICK AND MORTAR RETAIL OPERATIONS

58.6% are self-employed or work with one to ve others.

All music retailers surveyed are seeing less work since the onset of COVID-19.

40% have not been able to transition to remote work.

84.6% surveyed received a stimulus check for $1,200 under the CARES Act.

22

THE FINALE

A VALUE GAP?

Survey to the Music Industry respondents rank “the inability for artists to make a living wage from their music” as

number one among issues they consider most important for the music industry to address within the next ve years.

Industry professionals overwhelmingly agree that songwriters (79.6%), recording artists (65.4%) and backing musicians

/ vocalists (61.5%) are not compensated fairly for their work. Consumers similarly agree for songwriters (61.6%) and

recording artists (48.7%).

And nally, when presented with the statement, “A disparity exists between the value listeners get from music and the

revenue that creators get for the use of their music,” 81.9% agree.

COVID-19 highlighted areas of considerable pre-existing weakness in the music industry. If the music industry is to

continue to exist, capital must return to those directly responsible for it: creators.

MUSIC INDUSTRY DENSITY

With a LQ of 6.1 for the music industry, the Nashville MSA has an employment concentration

triple that of the Los Angeles area (LQ 2.2) and nearly ve times that of New York City’s MSA

(LQ 1.4). To further illustrate this point, long term job specialization growth (2012 – 2019) in the

music industry is highest in the Nashville MSA with the Los Angeles area coming in second

followed by New York.

Music Publishers

Record Production and Distribution

Other Sound Recording Industries

Musical Intrument Manufacturing

Sound Recording Studios

Musical Groups and Artists

Software; Other Prerecorded

Radio Networks

Radio Stations

Total

39.70

24.75

7.58

7.45

6.18

6.18

3.32

2.69

1.34

6.11

5.09

4.70

1.87

1.72

4.09

2.85

1.59

1.71

0.77

2.16

1.82

3.89

1.25

1.72

1.70

1.38

0.57

1.76

0.87

1.37

1.22

0.79

1.64

1.30

2.42

1.30

2.25

0.45

0.75

1.13

0.51

1.38

0.76

0.83

0.81

0.95

2.08

0.57

0.61

0.84

0.10

0.19

0.68

0.12

1.01

1.00

2.44

1.43

1.06

1.00

1.14

1.62

1.43

0.08

1.70

0.94

1.18

0.59

1.11

1.00

1.20

0.88

1.03

0.41

0.93

1.10

2.48

0.14

1.27

1.07

1.50

1.03

0.18

0.03

1.03

1.83

0.03

1.13

0.62

1.09

Nashville

Los

Angeles

New

York

Austin Chicago Denver Miami Memphis

New

Orleans

Industry Description

Location Quotient Table (2019)

LIMBO FOR TECHNICAL OPERATIONS

The majority of live music technical operations workers have not been able to go remote. They face a choice

either to wait until live music comes back, re-skill and/or leave the industry.

DIRECT ARTIST SUPPORT

Forty-seven percent of music consumers stated they had participated in crowdfunding or donated to

another source of supplementary income for artists during COVID-19.

NOSTALGIA-DRIVEN TRENDS

Vinyl record sales are outperforming CDs for the rst time since the 1980s. Community radio is thriving

via regular fundraisers according to interviewees. Legacy catalogs are experiencing resurgence among

synchronization licensors. Catalog acquisitions are on the rise.

DIGITAL CONSUMPTION VS. LICENSING RIGHTS

Although social media and digital streaming platforms account for the most popular music discovery and

listening formats among consumers, many licensing structures and royalty payouts to copyright owners

remain ambiguous. The Mechanical Licensing Collective is poised to help.

THE STATE OF LIVE MUSIC

Livestreaming provides a means for performers to continue to work, but data suggests it does not replace

the in-person experience. Live music is suffering right now but will return.

Most consumers surveyed believe live music will go back to the way it was before the pandemic in nine to

eighteen months. Nearly forty-six percent of respondents would not feel comfortable attending a live

concert until there is a vaccine for COVID-19.

GENRE DIVERSITY

In Nashville, support for music genres outside of country creates a richer music ecosystem and more industry

growth for all. Neglecting to foster all genres is a missed opportunity.

The Music Industry Report 2020 provides one with a comprehensive data set from which

they can make informed decisions. Full results are delineated in the following pages.

23

25

INTRODUCTION

Creative industries are unique. Fitting artistic and cultural expression into the framework of current economic

systems can be a difcult task for those working in these industries and for those attempting to understand them.

At a time when the world is experiencing uncertainty in the midst of a global pandemic, many people are turning

to art for comfort. Yet, creative industries are among the most negatively impacted economically. In light of this,

we want to thank the people who make art and music. This report is produced as an act of support for creatives

and the business infrastructures built around them. A goal of this research is to provide a resource for individuals

who work in the music industry. Through a deeper understanding of the music industry’s structure, its relation to

other industries and its present challenges, there is an opportunity to strengthen it.

Creatives not only work tirelessly to provide music, art and culture for the world to enjoy, but often face uncertain

compensation and conditions for their work. This dynamic exists beyond the COVID-19 pandemic and has only

been exacerbated by it. Many jobs are created related to music business activity. This activity forms a group, or

cluster, of businesses that often exist in geographic proximity to each other and function in a symbiotic way, a

phenomenon well-demonstrated by the Nashville music industry and its history.

After Queen Victoria told the Fisk University Jubilee Singers in 1873 that they “must come from a music city,”

Nashville’s tragectory was launched. Almost one hundred years later, the city was ofcially dubbed “Music City,

USA” in the 1950s by WSM announcer David Cobb. The music business has evolved to become an integral part

of the region’s economy today.

In 1892, what is now known as the Ryman Auditorium began drawing crowds. It quickly became known for its

atmosphere and then-central location in the United States. The Ryman would host the Grand Ole Opry (1943-

1974) and then The Johnny Cash Show (1969-1971). Meanwhile, Jefferson Street, not far from historically Black

Fisk University, was quickly establishing itself as a hub for the nascent entertainment scene. Legendary artists

such as Jimi Hendrix, Otis Redding, Etta James and Little Richard would eventually perform there.

In the early 1950’s, Owen and Harold Bradley began to lay the roots for Music Row. To capitalize not only on this

growing industry, the reasonable real estate prices and the proximity to the hub of industry, many more music

businesses would follow the Bradley pair. John Dotson, founder of the Music Row Neighborhood Association,

notes, “It was a purposeful design to facilitate collaboration…it was a beehive of one on one and group activity.”

Music Row can certainly be credited with the commercial reach and popularization of country music. In the

coming years, as country music and the Nashville music business scene grew, venues began to sprout up all

around Nashville.

26

Nashville MSA

The late 80’s and early 90’s witnessed Lower Broadway teem with life and country music become synonymous

with Nashville, culminating into a Music City that continues to symbolize country music and serve as a destination

for musicians and songwriters in the genre.

Off Music Row and the busy streets of Broadway, a growing number of live venues, record stores and recording

studios now provide space for musicians and independent music businesses giving rise to genres outside of

country music and new schools of thought in how music business should occur.

The Music Industry Report 2020 focuses on the Nashville region music industry and contextualizes it by

examining other metro-areas with strong music industries as well as national and global trends. The maps below

show both the Nashville Metropolitan Statistical Area as well as the other metro areas this study will examine

comparatively. Throughout the report, “MSA” and “region,” or “metro region,” are used interchangeably:

Davidson

Wilson

Smith

Trousdale

Dickson

Robertson

Sumner

Macon

Rutherford

Cannon

Williamson

Cheatham

Maury

Nashville

27

Key Music Industry-Centric Regions

In the spring of 2020, cities across the United States began to shut down non-essential parts of their

economies to slow the spread of COVID-19. Shutdowns in Tennessee and Davidson County began in March.

Due to a better understanding of how to mitigate spread—and to strategic alterations of certain kinds of

events, gatherings and business activity—most areas in the United States have opened back up to some

degree. Safety is still the number one priority. At time of writing, many areas in the United States including

the Nashville MSA and rural Tennessee are experiencing rises in case counts. The future, in terms of an end

of the pandemic, remains uncertain. Within this dynamic, the heart of the music industry, live music, has come

to a grinding halt around the world. Most of the industry, if not employed directly in this subsector, is directly

or indirectly affected by its halt, a circumstance which adds urgency to this work.

While COVID-19 has taken the industry by storm and exposed pre-existing systemic weaknesses, it has also

revealed solidarity, resilience and opportunity for a few. Relief funding has been directed toward people

in the music industry. Subsectors have banded together to create safety nets for those out of work. Online

social networks have been used to foster community and stay connected. And, many are looking to recovery

as an opportunity for restructuring parts of the industry that were not efcient or equitable.

This is an important time to deepen understanding of the music industry. The research team approaches this

task humbly and Exploration and the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce are excited to present the Music

Industry Report 2020.

Los Angeles

Denver

Chicago

Nashville

Memphis

Atlanta

New Orleans

Austin

POPULATION

13,000,000 - 19,000,000

9,000,000 - 13,000,000

3,000,000 - 9,000,000

1,500,000 - 3,000,000

1,000,000 - 1,500,000

New York

29

MUSIC INDUSTRY

The music industry is based upon a relationship between the listener and the music creator.

At this fundamental level, it performs two essential tasks:

WORKS

1. Provide musical experiences to the listener.

2. Return value to the music creator.

Here we can observe a simple exchange

in utility. However, in today’s music

environment, the space between the two

ends of this exchange is quite complex.

Within the space between the creator and listener is a workforce of some 1.9

million people (RIAA, 2018) who strive to support the listener-creator relationship.

These people, businesses and organizations are what we call the music industry.

We can categorize the music industry into two channels of exchange—one dedicated to the

distribution of the creator’s musical experiences, the other to the distribution of listener value.

Creates

musical

content

Provides copyright

administration

and management

Licenses

musical content

for use

Provides listener

access to

musical

experiences

Enjoys

musical

experiences

Receives value in exchange

for exploitation of rights

Collects and

distrubutes

royalties generated

from uses

Monetizes value

from listener

and exploits

copyrights

Contributes value

in exchange

for access

to music

HOW THE

30

Creates

musical

content

Provides copyright

administration

and management

Licenses

musical content

for use

Provides listener

access to

musical

experiences

Enjoys

musical

experiences

CREATOR’S SIDE

The creator’s side of the exchange operates as a function of the creator’s rights and the

authorization of licenses. One can observe this process through the following four steps:

As someone who brings a creative work to life, a creator contributes to some aspect of

a song in its xed and nal form. Under United States Copyright Law, this makes them a

copyright owner. Copyright ownership endows an individual with six exclusive rights.

When it comes to their musical work, only they may authorize the following:

However, when listening to a song, you

are often appreciating the talent and

contributions of several creators. This

primarily includes songwriters (the people

writing the song) and recording artists

(the people performing the song to be

recorded). Notwithstanding, background

musicians, audio engineers and producers

are other essential contributors.

To balance the rights of the two primary contributors, copyright law associates two different types of

rights with a single song.

• A composition copyright for the songwriter

• A sound recording copyright for the recording artist

Therefore, for someone who is not the copyright owner to use music in any way, the rights

holder must license either the composition, the sound recording or both.

31

Creators often outsource the management and administration of their

copyrights to music publishers and record labels. These companies can

also serve the role of Copyright Representative. Among other tasks,

representatives help to issue licenses, administer royalties and establish

relationships with intermediaries. A representative’s primary goal is

to generally exploit composition and sound recording copyrights on

behalf of their clients.

Creator

Copyright

Representative

Intermediary

Intermediary organizations specialize in the widespread licensing of musical

works for use. These organizations also serve as royalty collection agencies

when returning value to the creator. Due to the variety of licenses and

royalties, different intermediaries specialize in different licensing activities.

Examples of royalty collection agencies in the United States include ASCAP,

BMI, Music Reports, the Harry Fox Agency, The MLC and SESAC.

Use

A use is a transaction that exploits one or more of the creator’s exclusive

rights. The creator or the copyright administrator authorizes this use through

a license. Companies who use the creative works in one of the six ways

mentioned above obtain this license which allows them to provide musical

experiences to listeners.

Listener

The listener receives emotional and artistic utility from musical experiences.

These songs will shape their day-to-day lives, inuence their perspective and

embellish their experiences. In exchange, listeners contribute value back to

creators as detailed on the next page.

32

Receives value in exchange

for exploitation of rights

Collects and

distrubutes

royalties generated

from uses

Monetizes value

from listener

and exploits

copyrights

Contributes value

in exchange

for access

to music

LISTENER’S SIDE

The alternative function of the music industry is to return value to the creator. This is a

function of collecting value and distributing royalties. On a broad scale, we can observe this

process through four steps.

Listener

Listeners contribute both monetary and nonmonetary value to creators in

exchange for access to musical experiences. This can be money out of the

listener’s pocket or simply their time and attention. The listener accesses

musical experiences in a variety of ways, many of which you likely encounter

daily. Whether you know it or not, you contribute value when accessing musical

experience—by paying for a subscription to a streaming platform, viewing an

ad before a YouTube video or listening to a catchy song in a car commercial. Ad

revenue, stream counts and radio spins create value which is then measured,

collected and monetized by companies or organizations who directly facilitate a

musical experience.

Musical

Experiences

Streaming

Songs

Watching

Online

Videos

Hearing

Background

Music

In

Public

Watching

Live

Music

Music

In Ads

Downloading

Digital

Music

Listening

to the

Radio

Film/TV

Music in

Video

Games

Sheet

Music,

Tabs, Lyrics

33

Use

A use is a transaction that grants the listener access to a musical experience.

Non-copyright owners are liable in the form of royalty payment for any use

of music that exploits one of the six exclusive rights mentioned above.

Below are just a few examples of some familiar uses and their respective royalties in the United States.

Intermediary

Every use of a musical work is associated with some form of royalty. Due

to the sheer volume of these royalties, intermediary organizations often

specialize in royalty collection. Because there are a diverse set of uses and

royalties to account for, different intermediaries specialize in different rights

management activities.

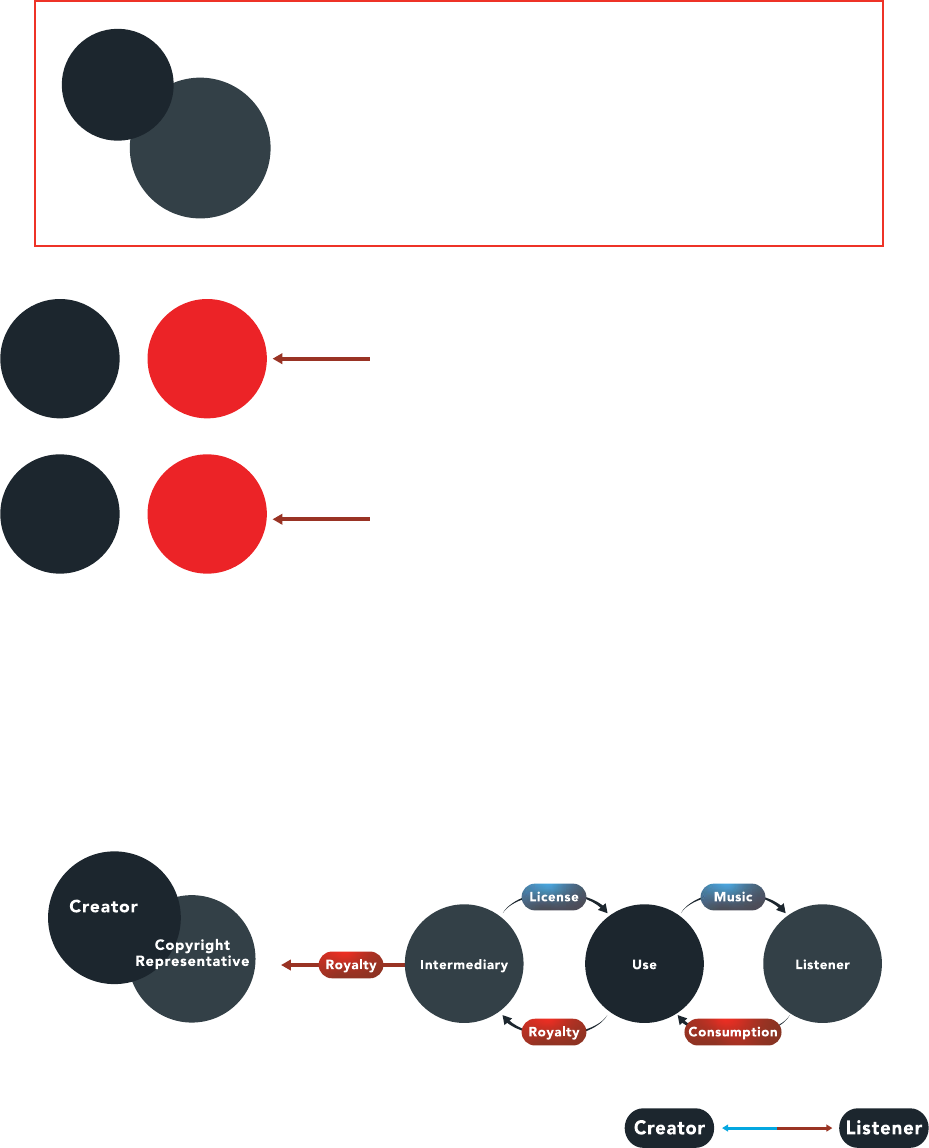

Below are just a few examples of some familiar Intermediary Organizations and their respective royalties in the US .

Streaming

TikTok

Youtube

Satellite

Radio

Performance

Royalty

Mechanical

Royalty

(Interactive)

Master-Use

Royalty

Mechanical

Royalty

Sync

Royalty

Performance

Royalty

Sync

Royalty

Performance

Royalty

Performance

Royalty

Mechanical

Royalty

Mechanical

Royalty

Collection

Agency

Performing

Rights

Organization

Composition

Performance

Royalty

Mechanical

Royalty

Mechanical

Royalty

Collection

Agency

Sound

Recording

Performance

Royalty

Sound

Recording

Performing

Rights

Organization

Music publishers typically serve the role of Copyright Representative

for songwriters while record labels serve this role for recording artists.

Music publishers and record labels collect the royalties for their

respective creators and pay them accordingly. Contracts between

creators and representatives typically specify a length of time, how

creator’s exclusive rights are transferred and the administrator’s

compensation.

Creator

Copyright

Representative

Industry workers appear to recognize a

discrepancy between compensation for

creators and the value they provide. Most

respondents to the Survey to the Music

Industry asserted that both songwriters and

recording artists are not compensated fairly for

their work. Sixty-ve percent of respondents

do not believe songwriters are compensated

fairly for their work and 52.3% do not believe

recording artists are compensated fairly for

their work. This compensation structure has

powerful inuence over the creator’s livelihood

and facilitates the nal step in the exchange of

value.

This exchange supports the listener – creator relationship and effectively the entire industry.

Through these two channels of exchange, from the Creator’s Side and the Listener’s Side, money and music

certainly appear to be thrown in every direction, exchanged by multiple parties. It may come across as quite the

juggling act. But all else aside, the basic goal is to facilitate the experience of a listener and the livelihood of a

music creator. A rich ecosystem of businesses, organizations and people make this exchange possible.

Not only are there many caveats to this process, it is also subject to

constant change. The industry adapts to new developments in the way

people both listen to and create music.

At the end of the day, the entire act is dedicated to the two most important contributors and their essential

relationship: the listener and the creator.

Songwriter Publisher

Recording

Artist

Record

Label

Composition

Royalties

Sound

Recording

Royalties

34

FACETS OF THE

MUSIC INDUSTRY TODAY

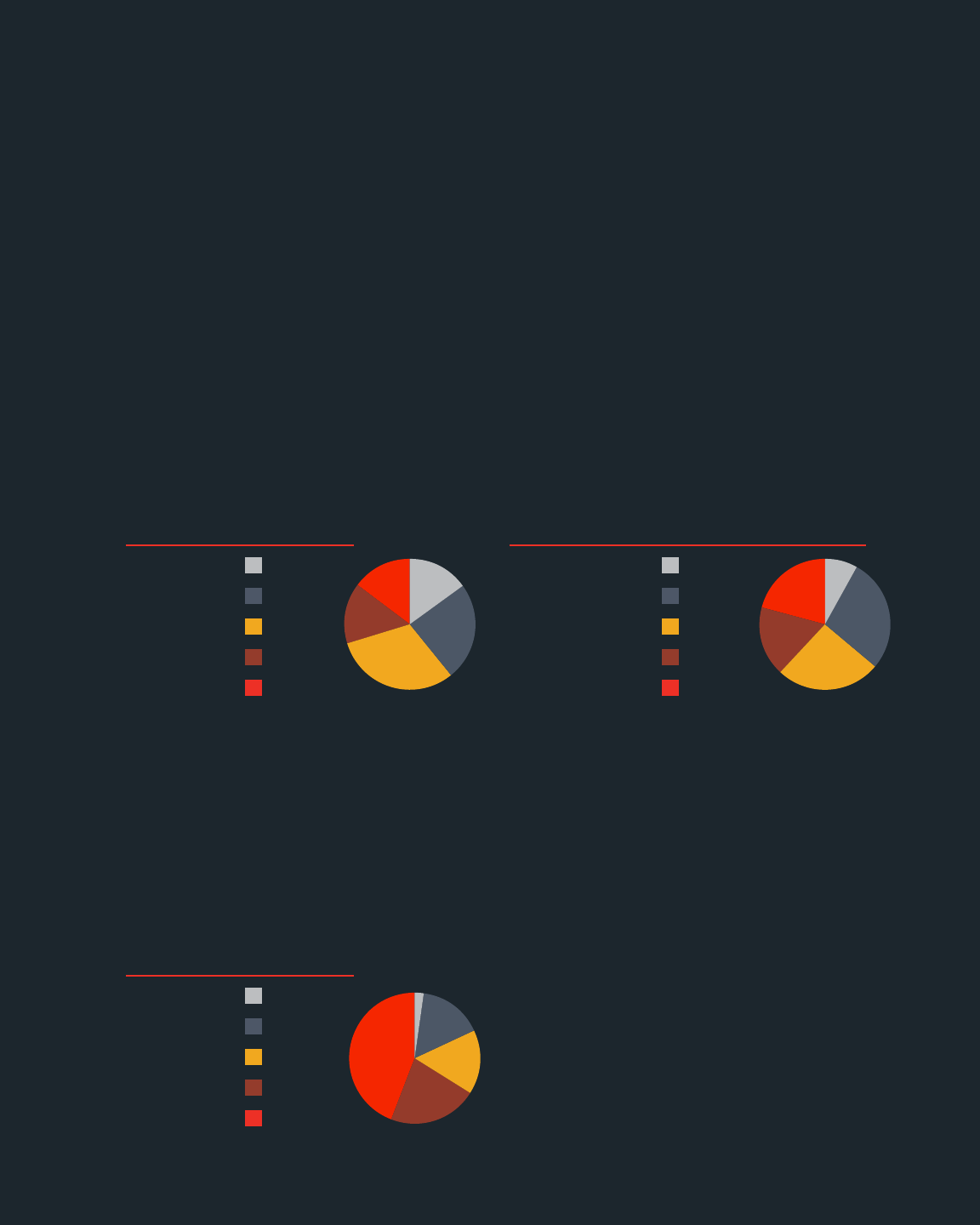

The music industry is worth over $50 billion. Two categories, live music and recorded music, account

for $20.2 billion and $25.6 billion of this total, respectively, leaving approximately $10 billion for

music publishing, $3.5 billion for music merchandise licensing and $6 billion for musical instrument

retail, among other sources of revenue.

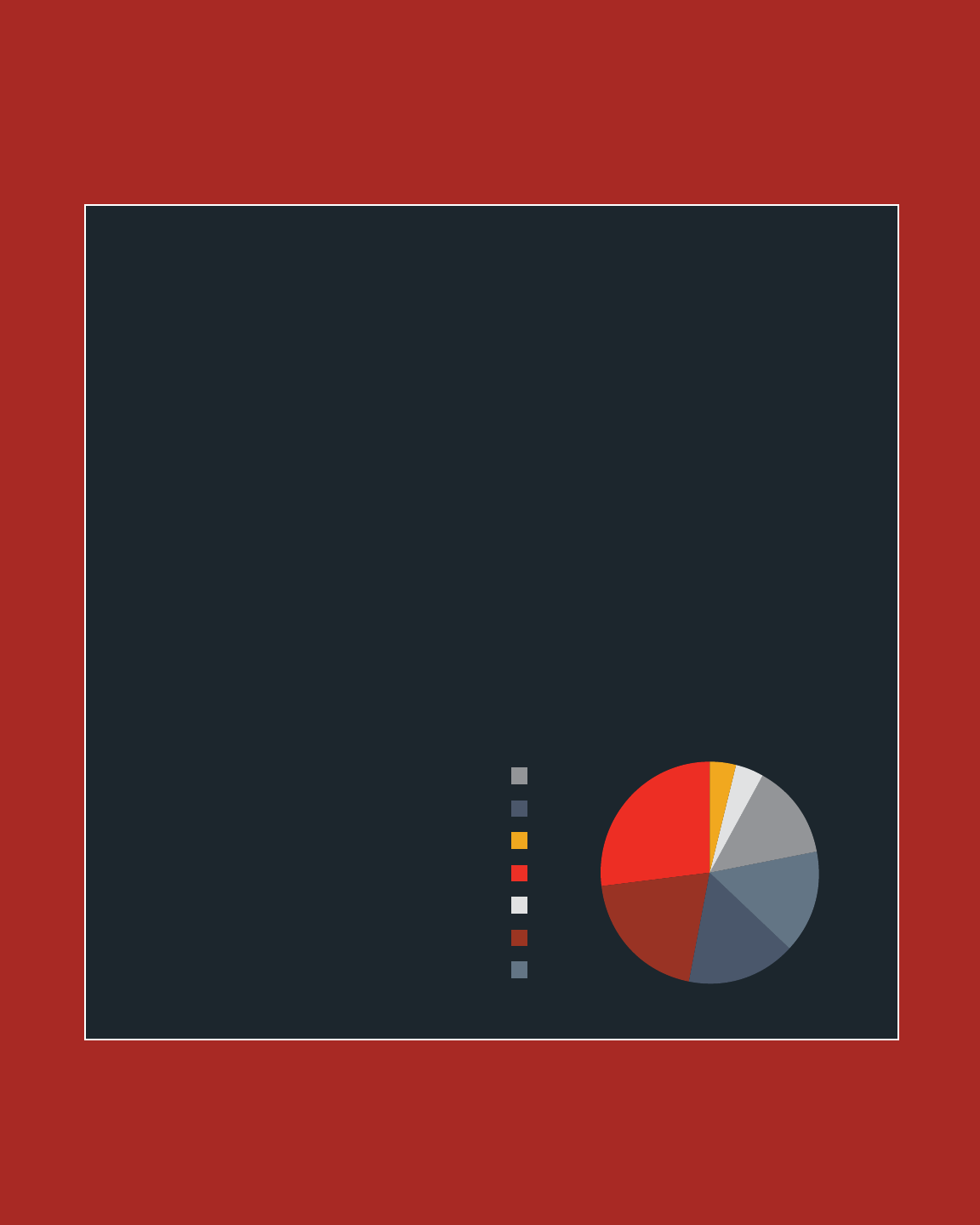

Recorded Music 30.6%

15.2%

38.9%

9.1%

5.3%

1%

Percentage

Source of

Music Industry Revenue

(2019 Global)

20.2

10

25.6

6

3.5

0.7

66.0

Count

(By Billions)

Music Publishing

Live Music

Merchandise

Instrument and Equipment Retail

Other

Total

Each of these revenue sources account for a network of business operations explored in following details.

TRADITIONAL SMALL BUSINESS MODELS,

STARTUPS AND VENTURE CAPITALISM

A few large corporations—Sony Music Entertainment, Warner Music Group and Universal Music Group—

traditionally dominate market share in the recorded music industry. According to research rm MIDiA, 2018 saw

the “Big 3” comprising 70% of $18.9B in total revenue.

Small businesses, on the other hand, provide a unique glimpse into the health of an industry. Newer companies

act as hotbeds for innovation through technological development and operational efciency. Corporations often

enlist the services of startups in the world of music publishing and recorded music. And to the watchful eye,

venture capital represents a signpost for the most successful music businesses of tomorrow.

Though the small business and startup environment may be tumultuous, opportunities and emerging markets

continue to develop in the face of adversity.

36

1 2 3

4 5

6

WHO RUNS THE SHOW?

Small businesses and startups represent a smaller and more concentrated eld compared to the size and

inuence of larger corporations that make up the music industry. This report’s Survey to the Music Industry

tracked a population of 271 company owners ltered only to those who own companies employing less than

one hundred people (263).

CURRENT STATUS BY THE NUMBERS

Nearly seventy-nine percent of small business owners report losing revenue since the onset of COVID-19.

For those facing lost revenue and mounting expenses, lay-offs, furloughs and other reductions in staff

inevitably come under consideration. Most small business owners have delayed hiring, laid-off or furloughed

employees since the onset of COVID-19. Twenty-nine percent report having laid off or furloughed at least one

employee. Only 5.9% have hired on.

As for benets and other forms of relief offered to employees, 88% have not offered additional monetary

or other relief since the onset of COVID-19. Many companies who were able to provide employees with

additional relief cite the Paycheck Protection Program.

Insurance plans have largely remained unchanged for small business owners, though 48.2% of respondents

say their companies do not offer health insurance.

More than half of respondents anticipate their companies bouncing back to similar levels of revenue in one

to two years, about one fth expect to return to similar levels of revenue in seven to twelve months and still

fewer predict recovery for their company in three to four years. Signed clients are decreasing in value for nearly

60% of respondents.

Many small businesses have been able to remain alive during the COVID-19 pandemic thanks to government

aid from the U.S. Small Business Administration through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and Economic

Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL). Out of 114 survey respondents who applied for PPP, 84.2% were accepted. Out of

74 survey respondents who applied for EIDL, 77% of small business owners were accepted.

Seventeen percent of respondents have altered their standard agreements with clients in a material way.

Examples include pandemic clauses, lowering rates, exible cancellation and shorter terms.

37

SUCCESS METRICS AND OUTLOOK

Uncertainty almost never bodes well for an economy in the short term. Investors tend to hold off and mitigate

risk during periods of unrest and widespread change. Even small businesses and startups—traditionally the

inheritors of relatively signicant levels of risk—naturally contract under losses in revenue by hiring fewer

people and investing less in growth.

COVID-19, in addition to being an international health crisis, may spell the end for many small businesses in

the music industry. Nonetheless, a few will inevitably rise to the top.

Heather McBee of the Nashville Entrepreneur Center (NEC) and music industry veteran shares her perspective

on the music business’ impact on the music-minded entrepreneur culture in Nashville. The NEC runs a startup

accelerator called Project Music which brings together business leaders and tech entrepreneurs in the music

industry.

“The music industry works together to tackle its collective challenges. You can see that in an

organization like Leadership Music which brings together industry leaders from all sectors

to learn and collaborate. In the NEC’s Project Music program, we emulate the industry’s

collaborat[ive] nature by bringing together the entrepreneurs who are taking risks that drive

industry innovation. As they build their businesses and immerse in the music business, they

too work together to thrive.”

38

CURRENT STATUS BY THE NUMBERS

Nearly forty-eight percent of respondents from the Survey to the Music Industry somewhat or completely

disagree that the music industry adapts well to new technology. 4.8% don’t know.

Many were able to make the transition to remote work in 2020 and utilize video streaming technology to

maintain operational efciency. Only 16% of company owners reported remote work was not an option for

their business. Seventeen percent of those surveyed were not able to make the transition to remote work

during COVID-19. Only 19.8% of those who were able to make the transition claim remote work decreased

their working efciency day-to-day.

Some companies interviewed for this report, including Bandzoogle and Exploration, have always been remote-

rst and therefore did not require transition.

The Mechanical Licensing Collective (The MLC), discussed further later in this report, is an excellent example

of a large organization developing in the face of adversity. Currently operating with a staff of roughly 40

employees, it has never experienced in-person operations. Nearly all of its activities have occurred remotely

over 2020.

“Due to COVID, we have had to build [The MLC] as a fully remote and fully distributed

company,” says Kris Ahrend, “and we’ve been able to lean in and leverage a variety of

technology platforms that support remote working to ensure our team can continue to

function effectively during the pandemic.”

The Mechanical Licensing Collective

SOFTWARE, TECHNOLOGY

AND NEW MEDIA

Digital music is the most dominant form of music consumption in the world today. With the proliferation of

accessible technology and the renement of user experience, music consumers continue a steady advance in

their dependence on new media and technology. According to Mary Meeker’s BOND “Internet Trends 2019,”

total digital media usage is accelerating by 5% year-over-year based on daily hours spent with digital media per

adult user.

The adage “necessity is the mother of invention” proves accurate as it applies to the music industry’s

technological response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Newer forms of communication help maintain business

operations; newer entertainment media help sell advertisements; and newer catalog management tools help

intellectual property holders control their metadata.

39

7

40

“My reality of what my expectations are has had to kind of reset and my communication

with people has gotten a lot tighter. I’ve been scheduling a lot more calls. I’m less reliant

on email. I guess I’ve been trying to hone my relationships better. It’s actually given me

time to reach out to people and speak to them for longer than 10 minutes which I’ve

never really done before—it’s always been email, slack, [and] direct messages.”

Joel T. Jordan, Founder & President, Synchtank

“Conducting business in person is very different than conducting it on a Zoom call. I think

people have adjusted in the sense that they’re more productive…at the same time, on any

given day a signicant amount of members used to come by our ofce or we would go visit,

go out with after work, see at shows—that kind of spontaneous business isn’t happening.”

Richard James Burgess, President & CEO,

American Association of Independent Music

“I’m content to be where we are right now. The biggest downside for me in being

remote is the impact on our culture; its maintenance and development. Our productivity

seems to be as robust as ever. It’s just very hard to enfranchise or to bring on new people

to our workforce from a cultural perspective. That’s a very important aspect for me. For

us. Culture drives everything.”

Randy Goodman, CEO, Sony Music Nashville

“Given the way the music industry landscape began changing several years ago, our

company proactively built itself around everyone working remotely. It was part of our

strategy to save overhead and foster growth. We’ve stayed remote for six years now.”

Rene Merideth, Co-Founder/COO, Exploratiotion Group

Video conference meetings and working from home were frequent topics of conversation during

interviews with music industry stakeholders for this research.

“There is an opportunity to connect with new people who are based in L.A. or New York

who you might normally not have gotten a chance to work with but now because of COVID

they might be more willing to take a chance working with an upcoming artist.”

Anonymous A&R Consultant & Artist Manager

41

SUCCESS METRICS AND OUTLOOK

Livestreaming is a promising new media emerging during COVID-19 for performing artists. It is unclear, however,

whether this will result in any signicant revenues for the music industry.

While 83.9% of music creators surveyed did not perform any livestream concerts between March and April of

2019, 82.8% of music creators performed at least one live stream concert between March and April of 2020. One

respondent performed over one hundred livestreams.

“Right around March when I stopped playing on Broadway—which is what I do when I’m

home. That shut down so I had to adapt and gure it out.

So, I set up this crazy room I’m sitting in now. I do livestreams four nights a week and

that feeds my family and keeps all the bills paid. It’s interesting that I worked my whole

life to get to where I am right now and then all of this got shut down.”

Tyson Leslie, Rock Artist

“No artist can sustain [live]streaming for free forever. Until recently, the platforms that

many artists were ocking to for livestreams—namely the ones that were most familiar

to them, like Facebook and Instagram—could not be monetized at all. You could do a

charity stream, but it was impossible to get tips from fans directly to your own account

on the platform. Essentially, in exchange for artists losing all their revenues from touring,

they had to go online and do the same thing for free. It was a huge value gap.”

Data from the Consumer Survey sends some mixed messages when it comes to the “success” of livestreaming.

58.5% of respondents attended a livestream between March and April of 2020. This is an improvement from

March through April of 2019 during which only 26% of people reported attending a single livestream concert.

Most people surveyed watch over half of a livestream but not all of it. 71.3% of respondents said they did not

pay for any of the livestream concerts they attended. Thirty-nine percent said they were unsure if they would

ever pay to attend a livestream concert. Most (89%) concur that the cost of a ticket to a virtual concert should be

less than the cost of an in-person concert.

Comparing a live concert experience to a digitally streamed concert, 50% said it is nowhere near the real

experience. 31% of people said it is “pretty good but not the same.”

The research team spoke with Cherie Hu, Founder of Water & Music, for her perspective.

42

Regarding how artists can make livestreaming sustainable:

“There are a couple different approaches that I’ve seen work. One is high frequency,

or livestreaming often, at the pace of once a week or even once a day, to help build

a regular schedule and habit of engagement with fans. Another is high intimacy and

interactivity — namely, showing the fans the totality of the artist as a person during the

stream and/or giving people the opportunity to contribute to and inuence the outcome

of the stream. The third category would be high production value, on the level of a

Netix lm or concert documentary or even an in-game concert, that pushes the needle

on what a livestream musical experience really is. This is also a question of what [fans]

would be willing to pay for. I think for a super high-production, interactive, immersive

viewing experience, you can put a price tag on that and fans will be willing to pay. I

would say 99% of fans have never paid for a livestream before, but that’s also because

they never had the opportunity to.”

COLLECTIVE MANAGEMENT

ORGANIZATIONS

Among all sources of revenue within the music industry, recorded music generates the most, second only

to live music revenue. Licensing the use of this music is no simple task; it accounts for massive volumes of

musical works requiring the help of collective management organizations (CMOs). When a licensee pays for

a mechanical license, they pay for the right to reproduce a composition through the process of recording,

manufacturing and distributing the work. Money generated from plays on an interactive streaming service,

for example, result in a mechanical royalty for rights owners. Performance royalties are generated from public

performance of the song—live, on a streaming platform or any place where people gather.

The primarily digital nature of mechanical and performance licensing helps to uphold these organizations’

operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the National Independent Venues Alliance has revealed

that 90% of its members will be closed in October of 2020 which means venues have not been open to host

events that would garner performance royalties. Businesses and companies typically open to the public seem

to have maintained their membership with CMOs. However, uncertainty remains with growing concerns about

continued pandemic restrictions and a hyper-focus on correct metadata.

WHO RUNS THE SHOW?

ASCAP, BMI, SESAC and GMR are the performing rights organizations (PROs) for the United States. The

Harry Fox Agency, Music Reports, Inc. and now The Mechanical Licensing Collective are the mechanical

rights organizations for the United States. SoundExchange is a rights organization hand-picked by the U.S.

Government to handle master performance royalties in the United States. The Mechanical Licensing Collective

and SESAC are headquartered in Nashville, SESAC on 35 Music Square East; ASCAP, BMI and the Harry Fox

Agency are headquartered in New York City and host afliate branches in Nashville.

Cherie Hu, Founder of Water & Music

8

43

Notable CMOs around the world include PRS in the U.K., GEMA of Germany, FILSCAP of the Philippines,

SACM of Mexico, SOCAN in Canada, SACEM in France and SGAE in Spain. Most collective management

organizations around the world account for both performance and mechanical royalties; the United States

separates each license type.

Administrators can play a key role in managing a CMO’s metadata to increase royalty payments from users of

music to copyright owners. ICE, BMAT, and Exploration Group are notable examples.

CURRENT STATUS BY THE NUMBERS

Numbers from this report’s Survey to the Music Industry yield compelling insights. Regarding PROs,

future venue blanket license renewal appears to be shrouded in uncertainty. Of respondents involved

directly in venue operations, 35.4% were unsure as to whether they would renew their blanket licenses

with their country’s respective PRO.

The Mechanical Licensing Collective (The MLC) is currently preparing to manage all Section 115 Digital

Licensing in the United States which will fundamentally change how both rightsholders and digital service

platforms operate. Strategically located in Nashville, this initiative was contracted under the 2018 Music

Modernization Act and is scheduled to begin operations in January of 2021. As Kris Ahrend, CEO of The

MLC, explains:

“The MLC will be receiving sound recording data from the U.S. digital audio services that

secure the new statutory blanket license and then matching it with the musical works