Acknowledgements

Written by Dan DeSena, LMSW, DMA

Editors:

Pam Schweitzer, APRN, BC

Laura Lokers, LCSW

Ricks Warren, PhD

Based in part on the knowledge and expertise of:

James Abelson, MD, PhD

Joseph Himle, PhD

Laura Lokers, LCSW

Pam Schweitzer, APRN, BC

Ricks Warren, PhD

i.

Anxiety Program

Depression Program

CBT

Exposure

Group for

Anxiety

CBT

Cognitive

Skills Group

for Anxiety

Mindfulness

for Anxiety

Group

CBT Basic Group for

Anxiety

(2 sections)

CBT

Cognitive

Skills Group

for

Depression

CBT

Behavioral

Activation

Group for

Depression

CBT Basic Group for

Depression

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy

for depression relapse prevention

ii.

Weekly Group topics:

Anxiety Vulnerability Management (week 1)

Do you ever think you have more anxiety than

other people? Find out why and learn how to use

CBT skills to fight your anxiety over the long term.

Relaxation (week 2)

Just relax! What to do and when to try relaxation

strategies to help make you feel less stress and

tension in your daily life.

Exposure and Desensitization (week 3)

“Avoid avoidance:” how our behaviors can make

anxiety worse, and the surprising way to get it to

leave us alone!

Cognitive Therapy Skills (week 4)

Our thoughts matter! Learn ways our thoughts can

change how we feel and influence what we do.

Turn thoughts into your ally, instead of your enemy.

What is this group all about?

-Our group is an introduction to the basic concepts and

skills of CBT.

-There are four sessions, each with a different topic.

-These are offered weekly, the first four Mondays and

Tuesdays of every month. Each Monday and Tuesday is

the same topic, so you can come to whichever fits your

schedule best.

-You can attend these in any order you like.

-Each session we will cover just some of these CBT

skills. If you have questions during the group, please ask!

It is also possible any confusion you have at the

beginning will clear up as you continue to attend

the sessions.

-This group is not meant to fix your anxiety completely.

We want to give you a chance to try out some of these

techniques and understand your anxiety better. When you

get done with this group you may want to continue with

group or individual CBT treatment here at U of M.

We want to be sure that our treatment is

effective!

Evidence-based means that there is scientific

evidence to show that something works.

CBT is an evidence-based treatment that has been

studied and shown to be effective in hundreds of

scientific experiments.

While there is no 100% guarantee that CBT will

work for you, it is likely that with practice and hard

work you will receive benefit from these

techniques.

What is Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy?

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a short-term,

evidence-based treatment for many problems, including

anxiety. It is based on the idea that thoughts (cognitions)

and behaviors affect the way we feel.

Feelings (emotions)

Thoughts (cognitions) Behaviors (actions)

How to use this manual

This manual includes a lot of information on anxiety and CBT– more than we have time to cover in the group sessions, and perhaps more than you

will have time to review on your own! You will get the most out of this group if you take notes during the group and then review the manual

between sessions. Remember that different people get benefit from different CBT skills, so we expect that you will use the skills that work and let

go of the rest. We hope that you will try each skill out to determine if it suits you. Refer to “Appendix IV: This is so much information! Where

do I start?” to make your reading more efficient by starting with the information most pertinent to your particular problem. Finally, be sure to

bring the manual back next week!

iii.

There is a great deal of scientific research on

psychotherapy, and we know a lot about what

can be helpful for people. We continue to

learn more and more about how to use

psychotherapy to help as many people as

possible.

However, because everyone is different, and

our brains and lives are very complex, right

now it is often hard to know exactly what it is

that will help a particular person feel better.

On the next page, follow the

path from the bottom of the

page upward for some tips to

make your “path through

psychotherapy” more helpful

and rewarding.

iv.

See this as just one piece of the puzzle in your process of better understanding

yourself and moving toward what you want in your life. Get all you can out of it

and then make efforts to find out what other types of work could be helpful. For

example, maybe you did a great deal of work on managing your depression with

cognitive and behavioral skills. Now you believe that you want to improve your

relationships to achieve more in that area of your life.

Manage barriers to showing up regularly to treatment and practicing skills: improvement

depends primarily on follow-through and the amount of work you put into your therapy.

Address depression from different angles. There is no one “silver bullet” that will

change depression all by itself. Usually a combination treatment, or mixed

approach is what works best to make depression better. This also means putting in

some effort to understand the different ways to manage your depression.

Practice skills over, and over, and over. It usually takes time for changes in our

behavior and thinking to lead to feeling better. Like learning an instrument, we

are practicing new ways of doing things that will feel “clunky” at first, and

become more comfortable over time.

Take small steps toward change each day. Try not to wait for “light bulb

moments,” “epiphanies,” or for something to take it all away instantly.

Expect ups and downs during the process. Think of it as “2 steps

forward, 1 step back.” Try not to get too discouraged or give up

when things seem to move backward or stagnate.

Make it about you: engage in your treatment because you want to improve your life,

take responsibility for achieving you aims, and feeling better, not because others are

telling you to do so. Remember that even if you are being pushed to engage in therapy

by someone else, that relationship must be important enough for you to consider this

option!

Maintain an open mind about the possibility of change, while being realistic about

how fast this change can happen.

Especially at first, gauge success according to how you change your responses to stress,

uncomfortable emotions, and body sensations, not whether or not these things exist or

continue to occur. Focus on valued action, even more than just “feeling better.”

“Credibility:” Make sure the treatment in which you are engaging makes sense to

you and seems to be addressing your problem. There are different paths to the

same goal. If this type of therapy is not working for you, you are confused about

what you are doing, or you have any other concerns, talk to your clinician right

away. Clinicians are trained to have these discussions with their patients!

Make sure your definition of the “problem” is the same as the clinicians with

whom you are working. Maybe they think it is “depression” and you think it is

something else. Try to clarify this with your clinicians.

v.

Section One: Anxiety 101……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………………………………………..1.1

Anxiety Is……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1.2

Why does my body do this? …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1.3

Anxiety “Triggers” …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………..……………1.4

Anxiety “Fuel” …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………...…………1.6

Anxiety 101 Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………1.9

Section Two: Exposure and Desensitization ……………………………………….…………………………………………………………………..………………2.1

What is exposure? …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………2.2

Should I do exposure? ……………………………………………………………………….…………………………………………………………...………2.3

Desensitization……………………………………………………………………………………………..................................................................................................2.4

Exposure: Getting Started……………………………………………………………….........................................................................................................2.6

The Exposure Formula……………………………………………………………………………………………………….………….………….……………2.8

Exposure Tips………………………………………………………………………………………………...………………………………..……………….……………2.9

Exposure: Tracking Your Progress5………………………………………………...………………………………..………………....…………2.10

Exposure examples: “External Cue Exposure” ………………………...……………………………..………………....…………2.11

Exposure Examples: “Internal Cue Exposure” for Panic Disorder……………..……………….…………2.12

Questions about Exposure…………………………………………………………………………………………..……………….…....……….…………2.14

Exposure for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder…………………………………………..…………..…….…....……….…………2.15

Barriers in Exposure Treatment……………………………………………………………………………..……………….…....….…….…………2.16

The Freedom of Choice: Exposure in Daily Life……………………………………..……………….…....….…….…………..2.17

Exposure and Desensitization Summary………………………………………………………..………..…………….…....….…….……2.18

Fear Hierarchy Homework Form (blank) ………………………………….…………………..………..……………...….…....….……2.19

Exposure Tracking Form (blank) ………………………………………………………………………..……………….…….......……….……….2.20

Exposure Tracking Form for Hourly Exposure (blank) …………………......………………….……...........…….…….2.21

Section Three: Cognitive Therapy Skills……………………………………………………………………..…………………………..…….…….......….…….………3.1

What are Cognitive Therapy Skills? ………………………………………..…………………...……………..…….…….......….…….………3.2

Negative Automatic Thoughts………………………………………..…………………………………………...…..…….…….......….…….………3.4

Identifying Negative Automatic Thoughts………………………………………..…………………………..…….…..….…….………3.6

Thought Cascade Worksheet……………………………………….………………………..…………………………..…….…….......….…….………3.7

Daily Thought Record Worksheet………………………………………..………………………………………..…….…….......….…….………3.8

Cognitive Distortions………………………………………..…………………………..…….…….......….…….………………………………………………..3.9

Examples of Cognitive Distortions………………………………………..……………………………………..…….…….......….…….………3.10

Examining the Evidence………………………………………..…………………………..……………………………………….…….......….…….………3.12

The Gambler: Predicting Ourselves Anxious………………………………………..………...……..…….…….......….…….………3.13

Catastrophizing: “That Would Be Horrible” ……………………………..…………………………..…….…….......….…….………3.14

Examining Thoughts, Written Method………………………………………..……...………………..……..…….…….......….…….………3.16

Examining Thoughts Worksheet…………………………………………………..……..…………………………..…….…….......….…….………3.17

“The Only Thing We Have to Fear is Fear Itself:” How to work on

negative thoughts about anxiety and panic attacks……..…….……..........….…….………3.18

“Don’t worry…”

Cognitive Skills for Daily Worry and Generalized Anxiety.......….……….……3.24

Common Thoughts about Anxiety and its Treatment……………………………..……..….……3.30

Cognitive Therapy Skills Summary…………………………..…………………………………………..……..….….…….......….…….………3.31

Table of Contents, con

This part of the group is meant to explore important information about the anxiety itself. The

first step to managing anxiety is understanding it as well as we can– to “know thine enemy,”

so to speak.

“We experience moments absolutely free from worry. These brief respites are called panic.”

~Cullen Hightower

On the pages entitled “Anxiety is…” and “Why does my body do

this?” we’ll talk about:

-What the anxiety “alarm” really is: the “fight or flight”

response— and what its common symptoms are

-The difference between normal anxiety and “phobic”

anxiety

-What causes anxiety

-Why our bodies do what they do when we are anxious

-Why we can’t just “get rid of” the anxiety

In the section “Anxiety Triggers,” we’ll go over the different

things that can trigger anxiety and how the brain comes to believe

these triggers are dangerous.

In our final section, “Anxiety Fuel,” we learn about common ways

that anxiety can get worse, and how our own thoughts and behaviors

play a role in this process.

1.1

Anxiety Is…

The most pure form of the “fight or flight” response is a panic attack, which involves a rush of anxiety symptoms, many of which are

listed below, usually peaking in about 10 minutes. In these cases, the body is trying to tell us “something dangerous is happening right

now!” Other forms of anxiety that are less acute but often just as debilitating, such as chronic worry, involve symptoms similar to the

“fight or flight” symptoms of panic attacks. However, in these cases, it is as if the body is saying “something dangerous is going to

happen sometime in the future… so watch out!” The differences between the two are the intensity of the response and the context in

which it is triggered. In this manual we will refer to all anxiety symptoms as being related to the “fight or flight” response. The most

common anxiety symptoms are listed below. Try circling the ones that apply to you.

What causes anxiety?

We know from scientific research that anxiety is caused by a combination of factors related to both “nature” (genetics) and

“nurture” (experience). Check out page 82 for a more detailed explanation of the factors that can lead to anxiety.

Why can’t I just get rid

of my anxiety?

Anxiety is as vital to our

survival as hunger and thirst.

Without our “fight or flight”

response we would not be as

aware of possible threats to our

safety. We also might not take

care of ourselves or prepare

adequately for the future. And

we probably wouldn’t enjoy a

scary movie or a roller coaster!

Anxiety is necessary to protect

us and can even be fun at times.

It isn’t in our best interests to

get rid of it completely!

When “fight or flight” goes too far: “Phobic” anxiety

Everyone experiences anxiety from time-to-time. We often get the question: “How do I

know if I have an anxiety disorder?” An anxiety disorder is diagnosed when someone

experiences anxiety symptoms and these symptoms:

-Interfere with a person’s life aims

-Happen too often or with too much intensity, given the actual

danger of a situation

-Are not explained by other factors, such as a medical problem or

substance abuse

Some people experience significant anxiety and choose simply to live with it. It is up to

you to decide if you can handle the anxiety on your own, or if treatment is necessary.

Physical Symptoms

-Rapid heartbeat

-Sweating

-Trouble breathing

-Tightness in the chest, chest pain

-Dizziness

-Feeling: “Things aren’t real”

-Feeling: “I don’t feel like myself.”

-Tingling and numbness in fingers, toes,

and other extremities

-Nausea, vomiting

-Muscle tension

-Low energy, exhaustion

-Changes in body temperature

-Shaking, jitters

-Urgency to urinate or defecate

-Changes in vision and other senses

Take home point:

The symptoms of anxiety are the “fight or flight” response, and are normal, functional, and

necessary for survival. They become a problem when they are too severe or happen too often, given

the real amount of danger present, or if it interferes with the activities of life.

Remember: Anxiety is uncomfortable, not dangerous!

Cognitive (thinking) Symptoms

-Worries

-Negative thoughts about one’s ability to

tolerate emotions or future stress

-Negative predictions about future

events

-Other common thoughts:

“I am going crazy!”

“I am going to have a heart attack!”

“I am going to faint.”

-Trouble concentrating or keeping

attention

-Magical ideas, phrases or images such

as “If I do not wash my hands I will

die or someone will be harmed.”

-Preoccupation with body sensations or

functions

Behavioral Symptoms

-Avoidance of anything that provokes

anxiety, including people, places,

situations, objects, animals,

thoughts, memories, body

feelings, etc.

-Protective, “safety” behaviors

-Aggression, verbal abuse, lashing out

-Alcohol and/or drug use

-Compulsive behaviors, such as

excessive checking or other

unreasonable or harmful rituals or

routines

Anxiety is a part of our bodies’ natural alarm system, the “fight or flight” response, which exists to protect us

from danger. These natural body responses are not harmful— but they are really uncomfortable!

1.2

Anxiety Symptom

1. Rapid heartbeat_______

2. Sweating_______

3. Flushing in face_______

4. Tightness in the chest, chest pain_______

5. Feeling: “Things aren’t real”_______

6. Feeling: “I’m not myself”_______

7. Tingling or numbness in

fingers and toes_______

8. Nausea, vomiting_______

9. Muscle tension, stiffness_______

10. Low energy, exhaustion______

11. Changes in body temperature_______

12. Shaking, jitteriness______

13. Urgency to urinate or defecate_______

14. Hyperventilation or trouble breathing_____

15. Dizziness, lightheadedness_____

16. Worries_______

17. Negative predictions about future events_______

18. Trouble concentrating or keeping attention______

19. Avoiding_______

20. Fight or be aggressive_______

21. Changes in vision, hearing, smell, taste_______

22. Dry mouth______

There is a reason!

We have evolved over millions of years to better protect ourselves. Our brains have learned to automatically signal danger when it is

present or we perceive that we may be harmed in some way. Each symptom of anxiety has a specific evolutionary purpose, to help us

“fight” or “flee.”

Try to figure out how each symptom of anxiety is used by our bodies to protect us when we are in danger, by matching the

evolutionary purpose with the anxiety symptoms. Some in the right-hand column may be used twice, and there may be multiple

answers for some symptoms. Once you are done, you can see if you were right— the answers are at the bottom of the page. Also, a

more detailed diagram of the biology of the “fight or flight” response is in Appendix I, “The Biology of Fight or Flight.”

Purpose

A. Muscles contract and tighten to help us fight or flee

B. Push blood around the body faster to supply cells with

oxygen in case we need to use energy to flee or protect

ourselves

C. Lots of energy is spent for body to protect us

D. Body increases speed and depth of breathing

E. Thoughts tend to be negative and protective; it is dangerous

to have “good” thoughts if we are in danger!

F. Must stay alive, even if it means using force

G. Try to think of ways to protect ourselves in case bad things

happen in future

H. Brain is constantly scanning for danger, from one thing to

next

I. Body stops digestion and attempts to rid itself of excessive

harmful substances

J. If something is dangerous, remember it and get away from it!

K. Cools us off when we are running or fighting and makes it

harder for a predator to grab us

L. Blood is redirected away from head, skin, fingers, and toes; if

we are cut, we will not bleed to death as easily

M. Decrease in salivation

Did you know… when our body’s “fight or flight” alarm is triggered, a domino effect of chemical changes and messages are sent to

various parts of the brain and body, producing these symptoms. This process is programmed to last only about 10 minutes, unless it is

triggered again.

Answers: 1. B 2. K 3. B 4. A,D 5. L 6. L 7. L 8. I 9. A 10. C 11. L 12. A 13. I 14. D 15. L 16. E 17. G 18. H 19. J 20. F 21. L 22. M

1.3

Types of anxiety triggers and the Anxiety Disorder “Diagnosis”

Nearly anything can be trained to trigger the “fight or flight” response. Psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, and clinical

psychiatric social workers have tried to find ways to tell the difference between different types of anxiety triggers. Anxiety disorder

diagnoses come out of this attempt. While a diagnosis is not a perfect way of describing a person’s experiences, it can help us to

know what types of treatments may be effective. Different groups of triggers and the diagnoses most frequently associated with them

are listed below. Some of these categories overlap, and it is possible for one person to have more than one diagnosis.

“One thing leads to another:” how a trigger becomes connected with our “fight or flight” response

When we perceive danger, whatever it is that could be dangerous (in this case, a spider) is remembered by the amygdala. The next

time something reminds us of the spider, or we actually come into contact with one, our anxiety “alarm” goes off.

Our brains are designed to keep us safe. The anxiety

part of the brain, the amygdala, is like a radar that is

trained to spot dangerous objects and situations.

When this “radar” spots something that could be

dangerous, it tells the brain to begin the “fight or

flight” response, producing the uncomfortable

feelings we get when we are anxious.

+ “danger” or something bad happening =

(for example, getting bitten by the spider)

+

!!!

Now and in

future

Diagnosis

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia)

Panic Disorder

Agoraphobia

Specific Phobias

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Trigger

Worries, predictions, and negative thoughts about the future

Social situations and people, such as social events and performances, along

with fear of criticism from others

Fear of having a panic attack and fear of body feelings that remind one of

panic attacks

Places a panic attack has happened before or could happen

Places, situations, animals, objects, blood or injury, etc.

Disturbing intrusive thoughts, contamination, doubt and urge to check things,

etc.

Memories and things associated with a traumatic event

1.4

To identify what makes you anxious, ask yourself the following questions:

“When I feel scared or nervous, what is going on around me or what am I thinking about?”

“Am I worried about having more anxiety in the future?”

“Am I afraid of body sensations that remind me of intense anxiety attacks?”

“Do I ever try to do more than I can handle or create unrealistic expectations for myself or others?”

“Am I worried that I will not be able to cope if bad things happen in the future?”

Exercise

My anxiety triggers are:

List here the objects, situations, events, or places that tend to trigger your anxiety. Use

the questions above if you are having trouble figuring out what makes you anxious.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Anxiety “Triggers” take home points:

The brain can learn to be afraid of

almost anything, and some anxiety

“triggers” are more common than

others. These triggers help define

anxiety disorder diagnoses, which we

use to better understand the anxiety

and develop treatments.

Anxiety can be caused by scary events,

and anxiety can also make one more

likely to experience an event as scary.

It is important to understand your

anxiety “triggers.” In most cases it is

possible to figure them out yourself.

Sometimes it is necessary to have the

help of a mental health professional to

do so.

“Which came first, the chicken or the egg?”

Anxiety “Triggers,” continued

Scary event?? Anxiety??

We know from scientific research on anxiety that both are true. Events and stress in our lives can

create more anxiety. For example, a passenger on a flight that barely escapes an serious accident

may feel anxiety the next time they take a flight, especially if this was one of their first flying

experiences. Flying may then become a new anxiety trigger. Conversely, someone that is already

vulnerable to having anxiety (see page 82 for more on this) may experience normal turbulence on a

flight as scary and then feel afraid to fly in the future.

Some people wonder if scary events caused their anxiety, or if their anxiety itself is what causes them to more readily see things as

scary.

What if I don’t know what triggers my anxiety?

For the sake of treatment, it is important to learn to identify what it is that makes you anxious. For some people it is very clear; for

others, anxiety seems to come from “out of nowhere.”

1.5

Each time he avoids the spider, his amygdala gets more feedback that the spider is dangerous. Next time he sees the spider, his

anxiety “alarm” will be louder, or it may go off more quickly than before. The process by which the brain learns that something

is more dangerous over time is called sensitization. It is also called reinforcement of the anxiety because the anxiety response

gets stronger and stronger. Reinforcement can happen both in the short term (when the danger seems to be present) or in the

long term, as we discuss below.

Short-term reinforcement: the anxiety “snowball effect”

Have you ever worried about speaking in front of a group of people? Worries about performing well can lead to jitteriness,

cracking voice, difficulty concentrating, and other “fight or flight” symptoms. Often the physical anxiety symptoms will then

create more worry about the performance; this creates a “snowball effect,” in which anxiety gets worse and worse, even to the

point of panic.

When we feel anxious, we typically want to do something to make ourselves feel better. Most of these

behaviors feel natural because our bodies also want to keep us safe. However, some of these behaviors

can make things worse; we add “fuel” to the anxiety “fire.” We can add fuel gradually over time or

dump lots on all at once. In all cases the anxiety “fire” gets bigger.

What behaviors are in danger of causing the anxiety to get worse? Anything that teaches the amygdala (the anxiety center of

the brain) that something is dangerous. Remember our spider example? Let’s say that every time this man sees a spider he tries

to avoid it by getting away. What does this teach him? That the spider is dangerous, of course!

“Danger!!”

=

Worry about speech

“Fight or flight” symptoms during speech

“People may see that I am nervous!”

(more worry)

1.6

Long-term reinforcement: “Safety Behaviors” and negative thoughts/beliefs

As mentioned earlier, anxiety “fuel” is anything that teaches the anxiety center of the brain, the amygdala, that

something is dangerous. Over the long term, the most common ways to do this involve negative thoughts and beliefs

as well as protective actions called safety behaviors. While these behaviors seem to help the anxiety right now, they

usually make it worse in the long run. Examples are listed below.

Thoughts

Negative thoughts about:

-the future

-yourself

-other people

-the world

Examples:

“I am going to lose my job and end up

homeless.”

“I must have control…”

“That person thinks I am an idiot.”

“If I drive on the highway I will get into an

accident.”

“If I keep having this thought it must be

true.”

Anxiety “Fuel,” continued

Behaviors

Safety behaviors are often justified using “as long as” statements:

Avoidance: “As long as I avoid that, I will be safe.”

Attacking others, acting on anger, etc.: “As long as I use verbal

or physical force to protect myself, I will have control.”

Protective behaviors: “As long as I have my water bottle with

me, I am safe and will not have another panic attack.”

Rituals (usually part of OCD, characterized by excessive,

repetitive checking, washing, counting, asking for reassurance,

etc.): “As long as I knock four times when I have a scary thought,

nothing bad will happen to my daughter.”

Substance use (trying to “numb” the anxiety): “As long as I can

have some alcohol, I will feel better.”

Fearful thoughts

Anxiety symptoms (“fight or flight” response)

Safety behaviors

Whether in the short run or over time, anxiety feelings, fearful thoughts, and protective, “safety” behaviors work

together to keep our anxiety “fire” burning. Each feeds off the others, and any one of these can act as the “match” to

get the fire started. In CBT, our goal is to work on these thoughts and behaviors to help extinguish the fire as

much as possible.

1.7

Exercise

Anxiety “Fuel”

Below, list some of the ways you may accidentally make your anxiety worse, based on the material discussed above.

Anxiety “Fuel” take home points:

Some of our thoughts and behaviors, while they seem to help us, actually make anxiety worse. Safety behaviors, such as

avoidance and protective behaviors, as well as negative thoughts, serve to reinforce anxiety in both the short- and long-term.

It is important to understand what, if any, safety behaviors we are using, so that we can work to reverse this through treatment.

Anxiety “Fuel,” continued

Avoidance

Do I avoid anything because it seems scary

or makes me feel anxious? This may

include avoiding thinking about something

or avoiding certain types of situations or

people.

Things I avoid:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Anger and Irritability

Do I become angry or irritable and

attack others verbally or physically?

Times I become angry:

1.

2.

3.

4.

What I do when I am angry:

1.

2.

3.

4.

Protective “Safety” Behaviors

Do I try to protect myself in certain

situations in order to feel more safe?

How I try to protect myself:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Substance Use

Do I ever use drugs or alcohol in order to “numb” the

anxiety?

Types of drugs or alcohol:

When I tend to drink or use drugs:

Thoughts

Do I have thoughts that come up continually and make me feel

anxious?

Thoughts that make me feel anxious:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

1.8

A common question: What if it really is dangerous?

Of course, we are not trying to ignore anxiety or feel calm if something really is dangerous. One of our goals in CBT is to

learn what is dangerous and what is not, what we can control and what we can’t, and how to balance taking risks

with keeping ourselves safe.

If you are here, it is likely that the cost of trying to keep yourself safe is outweighing the advantages. We’ll be exploring

this more in some of our other modules.

Anxiety Is…

We learned that the symptoms of anxiety are the

“fight or flight” response, and are normal,

functional, and necessary for survival. They

become a problem when they are too severe or

happen too much given the real amount of

danger present, or if it interferes with the

activities of life. While having chronic anxiety

over long periods of time puts stress on the

body, it can be helpful to remember that anxiety

itself is not dangerous; but it sure can be

uncomfortable.

Anxiety Triggers

Here we learned that the brain can learn to be afraid

of almost anything, and some anxiety “triggers” are

more common than others. Anxiety disorder

diagnoses are organized based on what triggers the

anxiety.

We know that anxiety can be caused by scary events,

and anxiety can also make one more likely to

experience an event as scary.

It is important to identify your anxiety “triggers.” In

most cases it is possible to figure them out yourself.

Sometimes it is necessary to have the help of a

mental health professional to do this. A few tips are

on page 10.

Why does my body do this?

In this section we covered the ways that each

“fight or flight” symptom functions to protect

us in case we are in real danger.

We also learned that when our body’s “fight or

flight” alarm is triggered, a domino effect of

chemical changes and messages are sent to

various parts of the brain and body, producing

these symptoms. This process is programmed

to last only about 10 minutes, unless it is

triggered again.

Anxiety Fuel

Some of our thoughts and behaviors, while they

seem to help us, actually make anxiety worse.

Safety behaviors, such as avoidance and

protective behaviors, as well as negative

thoughts, serve to reinforce anxiety in both the

short- and long-term.

It is important to understand how we make our

anxiety worse, so that we can work to reverse this

through treatment.

1.9

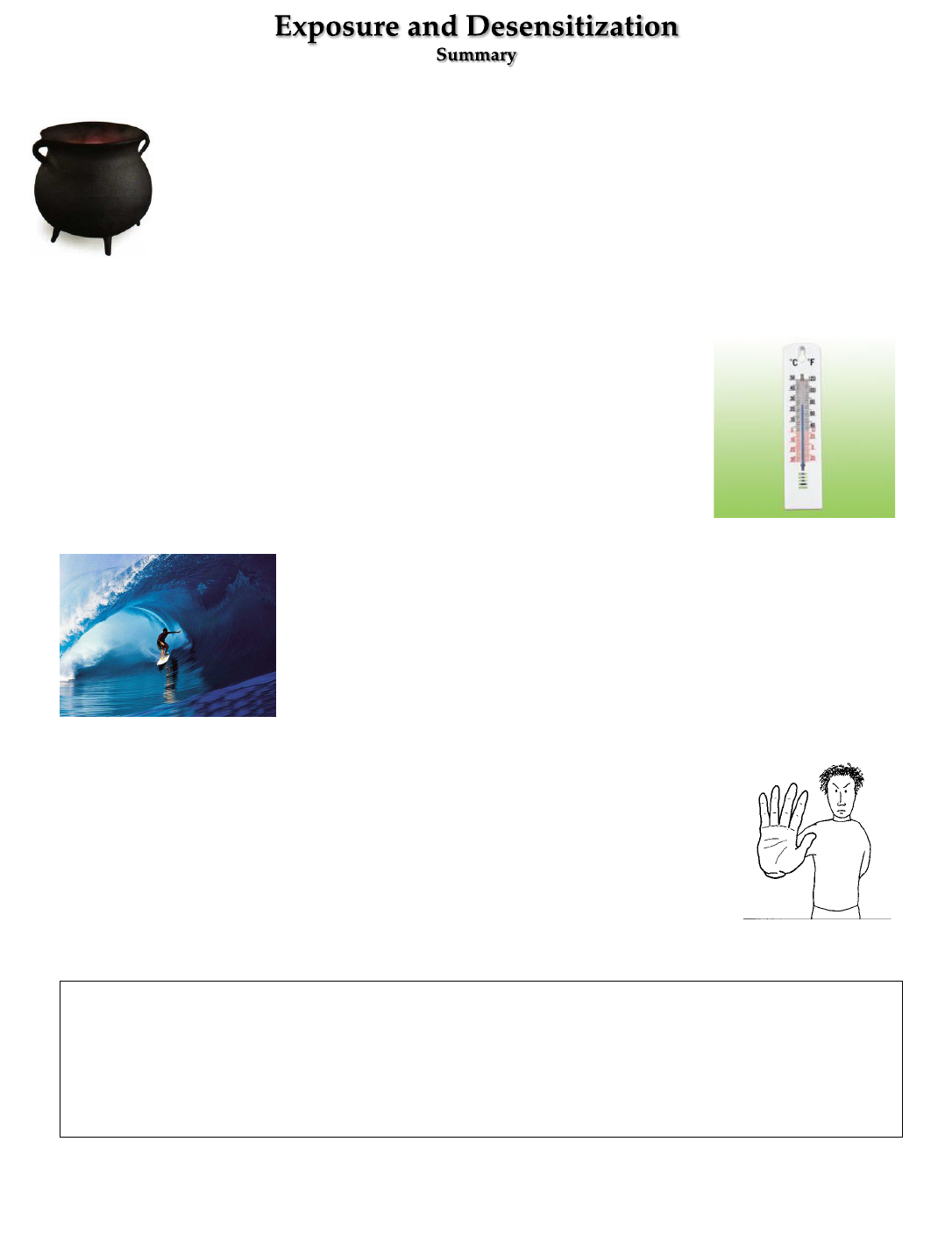

In this part of the group manual we will learn about exposure, one of the most

powerful weapons to battle anxiety and a big part of CBT treatment.

We spoke about sensitization in the section “Anxiety Fuel.” Now we’ll talk about

desensitization, which means we work to make our anxiety alarm less sensitive, so it

doesn’t go off as often or as loudly.

In this section we will learn what exposure is, when and how to use it, and some

important rules to follow to be sure we get the most out of treatment. We’ll also try to

give you lots of examples so it makes sense to you; we want you to know what to do,

but also how and why it works. In other words, we want you to be sold on exposure!

“Do one thing every day that scares you.”

~Eleanor Roosevelt

2.1

Have you ever been afraid of something and found that your fear became less intense over

time, the more you experienced something?

For example, some people can be afraid of flying and find that the more they fly, the easier it

gets.

This is how exposure works. Very simply, the more that we do something we are afraid of

doing, or are exposed to something that we are afraid of, the less afraid we tend to be.

Take home point:

Exposure and desensitization is just one set of skills used in CBT. It works best when we know what triggers our anxiety, and are

aware of avoidance and safety behaviors that we use when anxiety presents itself. The goal of exposure is to gradually expose

ourselves to whatever it is that we are avoiding, which helps us reduce the anxiety and make progress toward our life aims.

Exposure is one set of skills used in CBT. With exposure, we gradually begin doing some of the things we tend to avoid,

especially if these are things we need to do to reach our goals. The good news is that not only are we more likely to reach our goals

if we don’t avoid, but by doing the exposure exercises the anxiety can actually become less, so we feel better. When we feel better,

it is because the anxiety center of the brain, the amygdala, is getting less sensitive to a certain trigger. This is called

desensitization. We’ll talk more about how this works later.

When can I use exposure?

Exposure doesn’t work for all types of anxiety, and there are things we want to know before starting to use it. We hope that by the

end of this part of the group you’ll have an idea of when exposure can be helpful and how to use it.

To get a sense of when exposure may be helpful, ask yourself the following questions:

• Do I know exactly what is triggering my anxiety?

• Is there something important to me that I am avoiding because of the anxiety?

• Are there times when I try to stay safe or protect myself, which may affect my ability to live life the way I want to?

Be sure to review “Anxiety Triggers” if you have trouble determining what your triggers are. Sometimes it is helpful to get the

help of an experienced mental health professional to learn more about your triggers.

In the section of the group entitled “Anxiety Fuel” we learned about the ways that avoidance and safety behaviors can make the

anxiety worse. It may be helpful to review this section before beginning exposure exercises. As a rule of thumb, these behaviors

interfere with the improvement we might experience using exposure techniques. Later in this section we’ll be talking more about

how safety behaviors can get in the way of our progress with exposure.

Here are some examples of situations in which exposure principles can work:

A taxi driver has a fear of traveling over bridges. He avoids bridges at all costs and will even pull over

to the side of the road with a passenger in the car, pretending to have engine trouble. This fear of

bridges severely limits his ability to do his job. With the help of a therapist, he learns gradually to beat

his fear of bridges, starting by going over low bridges with a friend in the passenger seat. Eventually he

works up to driving over larger bridges on his own.

Bill, a college student, has a fear of public speaking. He tries to avoid taking classes that involve oral

presentations and when he does have one of these classes, he tries to avoid giving presentations by missing

class. He often fails to complete his work, and generally performs more poorly in these classes than he does

in classes that do not involve presentations. Bill seeks out treatment to address this and gradually learns to

speak in front of a few people, then small groups, and then ultimately larger audiences. With practice, he

becomes more comfortable speaking in front of others.

2.2

How avoiding public speaking impacts my

life:!

1. I worry about the next speech.!

2. I have to try to take classes that

don’t involve oral presentations.!

3. When I do speak in public, I feel

more anxious.!

4. I sometimes fail classes that involve

public speaking.!

5. I may limit the types of careers that

are possible for me.!

6. I may not be able to move up in my

profession if I avoid public

speaking.!

It is common to question whether or not to do exposure to reduce

anxiety and stop avoiding important things in our lives. Why?

Because facing our fears can be scary and takes hard work.

Before and during exposure we may need to remind ourselves of

why we are seeking treatment in the first place.

It can be helpful to consider how avoiding inconveniences us—

how it may keep us from achieving our goals. For example, Bill,

our friend with public speaking anxiety, could list the ways

avoidance impacts his life.

Writing down the ways avoidance impacts our lives can help us

understand how important it is to stop avoiding. We use

exposure to work on the avoiding itself.

Homework exercise: How can I use exposure?

Go back to the section “Anxiety Triggers” and list the triggers

you wrote under “My anxiety triggers are” here:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Now use the following questions to determine for what triggers

exposure might work:

• Am I avoiding any of these triggers because of

anxiety?

• Are there times when I am exposed to these

triggers and I try to stay safe or protect

myself, which may affect my ability to live my

life the way I want to?

Now list some of the triggers for which the answers to these

questions are “yes:”

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Homework exercise: Should I use

exposure?

Use Bill’s example above to write down the ways that

avoidance of some of these triggers either incon-

veniences you or keeps you from achieving your

goals.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

2.3

“This must not be

that dangerous…”

Give it time!

One trick about desensitization is that it usually takes time to retrain the amygdala to think

something is not dangerous, especially if it’s been trained over the years to think it is. As we will

discuss more later, one important thing about desensitization is staying in the anxiety

provoking situation long enough to learn it is not dangerous. Since our amygdala wants to

protect us, it needs a lot of convincing to be willing to turn down that anxiety alarm.

Take home point:

Through experience and over time we can make our brain less sensitive to certain anxiety triggers. This

is called desensitization.

You may remember from the “Anxiety Fuel” section of the manual that we can think and do things that make

the anxiety worse, like thinking over and over what might happen when we have to make that speech, or

avoiding speeches altogether.

Anxiety can also get worse when bad things really happen, or we perceive that some event is dangerous.

As we mentioned earlier, these events, safety behaviors and negative thoughts can make our anxiety alarm

more sensitive to certain triggers. This is called sensitization.

Desensitization is the opposite; our amygdala learns that something is not dangerous, through experience.

Take our spider example: if this guy continues to approach the spider, it teaches the amygdala that the spider is

not as dangerous as he once thought. If he is approaching that spider, it must not be that dangerous…

=

This is also called habituation, which means that we get used to something so that it no longer seems

as scary to us. We will even get bored, if we stay with it long enough. This is OK, because it is better

to be bored, than anxious!

The next time we are around the trigger, we may still feel some anxiety, but it is likely to be less. If we

do this over and over, the alarm gets weaker and weaker. Our anxiety “radar” may detect the trigger,

but our amygdala will not react to it like it did before.

=

less “anxiety alarm”

2.4

Desensitization, continued

Beware of Dog!

Elaine grew up around dogs all her life. Her family had many dogs, so she learned

through experience that dogs tend not to be dangerous. When she’d see something on the

news about a dog attacking a person, she’d think, “Wow, that seems odd,” because in her

experience dogs were not dangerous. This attack seemed like an isolated event and it did

not change her opinion of how dangerous dogs are.

Jessica did not have dogs in her home growing up. When she was six she saw a news clip

in which someone was attacked by a dog. She got the impression that dogs were

dangerous—each time she was around a dog, she remembered that news clip and began

to worry that the dog might attack her. She also felt scared and anxious when she saw a

dog in real life.

Jessica’s friend Rachel got a dog the next year. Jessica gradually learned through

experience that dogs weren’t always dangerous, and she began to feel less afraid.

“Oh, say can you see…”

Imagine that you were asked to sing the Star-Spangled Banner on opening day at

Comerica Park. Would you be nervous?

Now imagine you were asked to do this for every Tigers game– that’s about 80 home

games in a season. Would you be just as nervous after one month? At mid-season? At

the end of the season?

Wait just one second!

You may be thinking “I’ve exposed myself to this trigger over and over for a long time, and it

hasn’t gotten any better; in fact, it is worse! Why would exposure make this any better?”

There are some important rules about doing exposure that are necessary in order for it to work.

We’ll talk about these rules in the section entitled “The Exposure Formula.”

Exercise:

Try to think of some things to which you’ve become desensitized in your life. Examples are driving, scary movies, roller

coasters, air travel, etc. Think of things you’ve gotten good at with practice, and also maybe some fears you’ve overcome by

being exposed to them over and over and over. Then write them down here.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

2.5

Now that we know how desensitization works, we can get started. If you are still

questioning whether or not exposure will work for you, review the page “Should I do

exposure?” Remember that if there are currently avoidance or safety behaviors related

to a trigger, it is likely that exposure could be used to help bring the anxiety down.

Exposure exercise (different ways to trigger the anxiety)

-Speaking in front of a large group of professionals who are experts on the

topic on which I am speaking, using a prepared speech!

-Speaking in front of a large group of professionals who are experts on the

topic on which I am speaking, using a more impromptu style and few note cards!

-Speaking about myself in front of a few friends!

-Speaking for a few people who I don’t know and who don’t know my topic well!

-Speaking for about 10 people who are also students and don’t know my topic

well!

-Practicing a planned presentation on my own!

-Performing the speech for my girlfriend!

Anxiety Rating

9!

10!

6!

7!

8!

3!

5!

After listing the different

variations on the left, Bill rates

his anxiety on a scale of 0-10

using the “Subjective Units of

Distress Scale” (SUDS) for

each one. We discuss the SUDS

scale on the next page.

How do I know where to start?

If different anxiety triggers interfere with your life and you are not sure where to start with exposure, ask yourself the

following questions:

1. Which trigger interferes with my life the most?

2. With which one would I predict that my life would improve the most if the anxiety were less?

3. Does one stand out as being more “doable” than others? Would one be easier to start on, so I can start to get my life

back on track?

Based on the questions above, try to pick the most pertinent exposure target. Once you’ve chosen a trigger to start on, list

ways that you might be able to get your anxiety alarm going. For example, Bill might write down different types of situations

that would trigger his public speaking anxiety. We call this a Fear Hierarchy or a Stimuli Map.

When trying to come up with ways to vary the exposure, think about things that can change

how challenging the exposure is. Bill might list:

-Length of speech!

-How well I know the audience!

-How well they know the topic!

-How well practiced I am!

-Speech is more planned out versus more !

impromptu!

It is good to come up with a nice long list at first, so try to think of as many variations as

possible!

2.6

Exposure: Getting Started, continued

Exercise: “My Fear Hierarchy”

Pick a trigger and try designing some exposure exercises by listing possible ways to bring on the anxiety.

Exposure exercise (different ways to trigger the anxiety Anxiety Rating (0-10)

1. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________

4. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________

5. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________

6. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________

7. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________

8. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________

9. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________

10. __________________________________________________________________________________________________

11. __________________________________________________________________________________________________

12. __________________________________________________________________________________________________

The SUDS Scale

Exposure therapists often use a scale of 0-10 or 0-100 to rate the amount of anxiety someone has during exposure exercises. It

is like a thermometer, measuring how “hot” our anxiety gets.

This is called the Subjective Units of Distress Scale or “SUDS.”

0= no anxiety at all; completely calm

3= some anxiety, but manageable

5= getting tough; wouldn’t want to have it all the time

7-8= severe anxiety that interferes with daily life

10 = worst anxiety you’ve ever felt

Why do I have to rate my anxiety?

There are a few good reasons we ask folks to rate their anxiety before and during exposure treatment:

1. It helps us decide where to start and how to move from one exposure exercise to the next.

2. It keeps track of progress and helps us know if you are improving, staying the same, or getting worse.

3. It helps us start to step back from our anxiety when it happens and see that anxiety is not always the same

severity.

We will be talking about the SUDS scale often in this manual and you will be using it a lot during exposure therapy.

2.7

Take home points:

The first step in exposure practice is setting up a “Fear

Hierarchy” and rating the amount of anxiety you would feel for

each exercise.

Exposure practice requires repetitive, prolonged exposures to the

anxiety itself, with no “safety behaviors.”

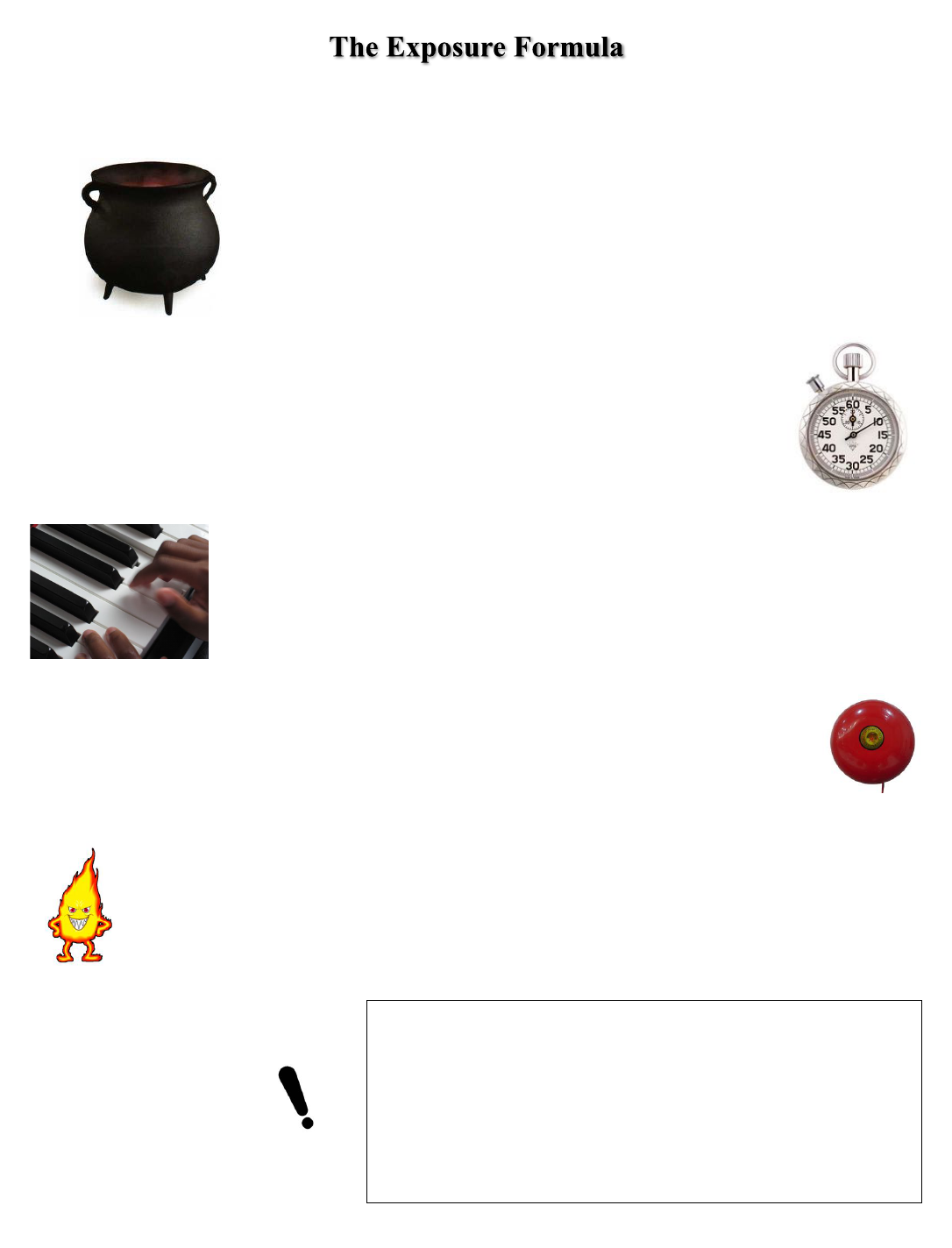

There are four main ingredients in the “exposure formula:”

1. It is prolonged

2. It is repetitive

3. We focus on the anxiety

4. We add no safety behaviors

Exposure practice is like a formula; there are certain ingredients that are necessary to get the results we want. We need to

understand these before starting the exposure practice, because if we don’t follow these rules, we aren’t likely to make much

progress. In fact, we could make the anxiety worse! We’ll be talking more about this in the next section.

Ingredient #1: Prolonged

As we discussed earlier, it is important to stay in the anxiety producing situation until the anxiety comes

down. Sometimes people ask if it is possible to do a shorter exposure practice in order to make it easier to

complete. Usually we advise people to adjust the difficulty of the exposure, not the duration, because

staying the situation long enough is necessary for the anxiety to come down. In fact, one important element

of feeling better is staying in the situation long enough and doing it often enough that we eventually get

bored with the trigger. This is important, because being bored it is a surefire way to know that we are not

anxious!

Ingredient #2: Repetitive

Have you ever played a musical instrument or a sport? Your music teacher or coach probably told

you to “practice, practice, practice!” Repetition is important for our brain to learn anything, and

anxiety is no exception. Some people notice that their anxiety goes down quickly after starting

exposure, but most people find that it takes consistent, daily practice to adequately retrain the brain

and feel better.

Ingredient #3: Focus on the anxiety

This is the part that can be difficult; we are going to ask that you try to focus on the feelings (the anxiety “alarm”)

that come up when you are in the anxiety provoking situation. Why? Because we are trying to convince the

amygdala that this trigger is not really dangerous. If we avoid these unpleasant feelings, we send the message that

the trigger is dangerous, and our time spent practicing exposure is wasted.

Ingredient #4: No “Safety Behaviors”

The same could be true if we spend our exposure practice trying to stay safe or protect ourselves from the trigger,

or the anxiety itself. You may remember that safety behaviors are a great way to “fuel” our anxiety and make it

stronger; they also really sabotage our exposure practice! We discussed some examples of safety behaviors in the

section “Anxiety Fuel.” You may want to review this before starting exposure; it is another very important part of

doing exposure correctly.

Important!

The #1 factor in seeing

improvement with exposure

is whether or not you do

the exposure and use all of

the ingredients listed

above.

2.8

Exposure seems simple; just expose yourself to something you are afraid of, and the anxiety comes down

over time. While this is true, going through an exposure program sometimes seems anything but simple.

We should be ready to troubleshoot when things get tough– and sometimes it can be confusing! Below are

some tips to help you through the exposure and improve your results.

Tip #2: Follow the rules of exposure

As we emphasized on the last page, it is very important that all

of the “ingredients” of the exposure formula be included in

order to get good results. It is especially important that the

person doing the exposure stay in anxiety provoking situation

long enough for the anxiety to decrease. Review these

concepts on the previous page.

As we mentioned before, the #1 factor determining whether or

not someone does well with exposure is whether or not they

practiced exposure consistently and followed the rules.

Tip #3: Unify your cognitive and behavioral “forces”

Imagine an army going into battle tentatively, with only half

the number of soldiers, worried that there may be some

casualties. How do you think they would fair against the

enemy? Probably not so well.

Sending the message to the amygdala that the trigger is not

dangerous works best when our thoughts and behaviors

are aligned, a “unified front” against our enemy, the

anxiety.

If we have doubts about whether or not the anxiety

provoking trigger is really dangerous and then try to do

exposure, it’s like going into battle without all of our forces.

The anxiety is likely to win the battle, because our negative

thoughts continue to send the message that the trigger is

dangerous.

For example, when Bill goes to do exposure for his public

speaking anxiety, he reminds himself of the evidence he has

that making a mistake would not be the end of the world. We

discuss the methods to do this in the Cognitive Therapy

Skills module of this group manual.

Tip #1: Choose wisely!

Throughout exposure, try to pick exercises you are

confident you will complete. Often people become

frustrated with exposure because it is “too hard,” and they

may even leave the exposure practice early.

When first starting exposure, it is best to take something

from your Fear Hierarchy in the “5” or “6” range on the

SUDS and then very gradually increase the difficulty of the

exposures. If you are having trouble with an exercise, try

making it a bit easier and commit to becoming comfortable

with that particular trigger.

When designing exposure exercises, it is helpful to try to

make them convenient; in other words, make it hard to

forget to practice, and schedule it into the day so it does not

take a lot of extra work to get going. Give yourself every

chance you can to follow through with the exposure.

Tip #4: Be prepared for some discomfort

and stay aggressive!

Exposure can be difficult at times; after all, if we are going into

battle, we should expect the enemy resist us with everything it

has!

The main defense the anxiety has is discomfort, and we can

expect to feel some during the exposure. Usually the

discomfort is most severe early in the exposure, and some

people even find that the anxiety gets worse before it gets

better. This is our body trying to get us to give in and play

defense; but we know our best bet is to stay aggressive and not

listen to what the anxiety is telling us.

We are going to try to “ride” the anxiety wave, always

remembering that anxiety is uncomfortable, not dangerous!

2.9

Once we begin practicing exposure, it is important and helpful to track our progress. Remember

our Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS)? We’ll use this to rate how much anxiety

comes up when we do an exercise. We rate our anxiety at the beginning, middle, and end of

each exercise. Let’s take our friend Bill’s public speaking exposure as an example.

Exposure task: Performing my presentation for friends !

Length of time SUDS (0-10)

Day/Date Start Stop Beginning Middle End Comments

4/15 10:15 am 11:15 am 2 8 4!

4/16 2:00 pm 3:00 pm 2 8 3!

4/17 5:30 pm 6:30 pm 1 9 4 Lost train of thought!

4/18 5:30 pm 6:30 pm 1 5 2!

4/19 10:00 am 11:00 am 0 4 1!

4/20 6:00 pm 7:00 pm 0 3 1!

4/21 10:15 am 11:15 am 0 2 .5!

This is the type of progress we would expect to see for someone that consistently practices this one exposure

exercise. You may notice that the “middle” levels are often highest, because it takes some time for the anxiety to

come down.

We can also do multiple “mini” exposures to things that are harder to do for a full hour straight. For example, Jane,

who has Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and fear of contamination, is practicing exposing herself to a rag that has

been in contact with a door handle one time every hour, all day long.

Exposure task: Touching rag that had contact with door handle !

SUDS (0-10)

Day/Date: 4/15 4/16 4/17 4/18 4/19 4/20 4/21!

8:00 am 8 8 7 5 3 4 3!

9:00 am 8 6 5 4 2 3 2 !

10:00 am 8 5 4 4 3 3 .5!

11:00 am 7 5 4 4 1 2 0!

12:00 pm 7 5 3 3 . 5 2 0!

1:00 pm 6 4 4 3 1 1 0!

2:00 pm 4 5 3 4 1 1 0!

3:00 pm 4 3 2 2 .5 2 0!

4:00 pm 4 3 1 1 0 .5 0!

5:00 pm 5 4 1 1 0 0 1!

6:00 pm 3 7 1 1 2 0 0!

7:00 pm 3 6 2 .5 0 0 0!

8:00 pm 3 5 1 1 0 0 0!

9:00 pm 4 5 1 1 0 0 0!

10:00 pm 4 5 1 2 1 1 0!

You may notice in both of these examples that there are times when the anxiety will come down, and then go up again.

At other times the anxiety starts high and comes consistently down. When we record our SUDS scores this way, we

can see that over time the numbers tend to come down, with some fluctuations in the middle.

2.10

Step Six: Ending exposure

Bill continues to practice the exposure for about 12

weeks, changing the exposure exercise about each

week as he moves up the hierarchy. After this, he

decides to continue to practice public speaking, but

less formally, to maintain his gains and refine his

skills.

External cue exposure is a fancy way to describe exposure to situations, places, objects, animals, or people

in our environment that make us feel anxious. This is also called in vivo exposure, which means exposure

“in real life.” Let’s take a look at Bill’s in vivo exposure for public speaking anxiety, one step at a time.

Step One: Pick a trigger

Bill has decided he really wants to beat this fear of

public speaking. He decides to focus on this target and

commits to designing an exposure plan to reach his

goal.

Step Four: Starting exposure

Bill picks an item from the list in the “5-6” range on the SUDS. He begins by speaking in front of his friends one hour each day

for one week. He tracks his progress using the SUDS (see Exposure: Tracking Your Progress). He also follows the rules of

exposure outlined in the section “The Exposure Formula.”

Step Three: Rate the hierarchy

Bill rates each item on his list using the SUDS scale (see

“Exposure: Getting Started” for more in-formation on the

SUDS).

Step Two: Create a fear hierarchy

Bill lists ways that he could purposely trigger the anxiety.

He thinks about different ways to make public speaking

situations more or less difficult.

Step Five: Middle sessions of exposure

Once Bill’s anxiety comes down to about a “3” or less

on the SUDS consistently for 3-4 days, he moves on to

the next highest item on his hierarchy. He goes to a

Toastmasters group where he practices in front of

people with whom he feels less comfortable. When he

again habituates to this exercise, he moves on to the

next.

Bill moves through his hierarchy until he feels

comfortable speaking in front of superiors who are

knowledgeable about his topic. Since it was hard to

find superiors to help him practice exposure, he had to

revise his hierarchy to create this fear as realistically

as possible. For instance, he practiced speaking about

current events at Toastmasters, because most people

could be considered “experts” on these topics.

For more information about Toastmasters, visit

www.toastmasters.org.

Exposure exercise (different ways to trigger the anxiety)

-Speaking in front of a large group of professionals who are

experts on the topic on which I am speaking, using a prepared

speech!

-Speaking in front of a large group of professionals who are

experts on the topic on which I am speaking, using a more

impromptu style and few notecards!

-Speaking about myself in front of a few friends!

-Speaking for a few people who I don’t know and who don’t know

my topic well!

-Speaking for about 10 people who are also students and don’t know

my topic well!

-Practicing a planned presentation on my own!

-Performing the speech for my girlfriend!

Exposure exercise

-Speaking in front of a large group of

professionals who are experts on the topic on

which I am speaking, using a prepared speech!

-Speaking in front of a large group of

professionals who are experts on the topic on

which I am speaking, using a more impromptu

style and few notecards!

-Speaking about myself in front of a few friends!

-Speaking for a few people who I don’t know

and who don’t know my topic well!

-Speaking for about 10 people who are also

students and don’t know my topic well!

-Practicing a planned presentation on my own!

-Performing the speech for my girlfriend!

Anxiety Rating

9!

10!

6!

7!

8!

3!

5!

2.11

Internal cue exposure means that the trigger for our anxiety is internal, or inside our bodies. This type of exposure

is used most often for people that struggle with Panic Disorder. Anyone who has had a panic attack knows how

uncomfortable it is; this is the “fight or flight” response at its worst! Often the “trigger” for panic attacks is body

symptoms and feelings. Remember what we discussed in the “Anxiety Fuel” section? Uncomfortable body feelings

can lead to worries about further anxiety symptoms, which then triggers more symptoms, which leads to more

worries, and before we know it we are in the middle of a full-fledged panic attack.

Because the trigger for panic attacks within the context of Panic Disorder is the body, the exposure exercises center

on the anxiety symptoms themselves. If we can become comfortable with the idea of having the anxiety symptoms,

we train the brain that the anxiety is not really dangerous, and the anxiety “alarm” doesn’t need to be sounded as

loudly or as often. These are also called interoceptive exposure exercises, which is a fancy way to say exposure to

feelings of anxiety and panic in the body.

Take a look at these interoceptive exposure exercises that can be used to toughen up against the possibility of having a panic

attack. The person would pick a symptom that they experience when they have panic and practice one exercise daily. Each person

may not respond to each exercise, so it is important try a number of them and find one that will trigger some anxiety.

Symptom: Rapid heartbeat

-Run on the spot or up and down stairs for 1 minute,

then 1 minute break. Do this sequence 8 times.

Symptom: Dizziness or lightheadedness

-Spin slowly in a swivel chair for 1 minute, then 1 minute

break. Do this sequence 8 times.

-Shake head from side-to-side for 30 seconds, then

30 second break. Do this 15 times.

-While sitting, bend over and place head between

legs for 30 seconds, then sit up quickly. Do this 15

times.

-Hyperventilate (shallow breathing at a rate of 100-

120 breaths per minute) for 1 minute, then normal

breathing for 1 minute. Do this 8 times.

Symptom: Breathlessness or smothering feelings

-Hold breath for 30 seconds, then breathe normally

for 30 seconds. Do this 15 times.

-Breathe through a narrow, small straw (plug nose if

necessary) for 2 minutes, then 1 minute breathe

normally. Do this 5 times.

-Sit with head covered by a heavy coat or blanket.

Symptom: Choking feelings, gag reflex

-Place a tongue depressor on the back of the tongue

(a few seconds or until inducing a gag reflex). Do

this repetitively for 15 minutes.

Symptom: Tightness in throat

-Wear a tie, turtleneck shirt, or scarf tightly around

the neck for 5 minutes, then take a one minute

break. Do this three times.

Symptom: Trembling or shaking

-Tense all the muscles in the body or hold a push-up

position for as long as possible for 60 seconds, then

rest 60 seconds. Repeat 8 times.

Symptom: Sweating

-Sit in a hot, stuffy room (or sauna, hot car, small room

with a space heater)

-Drink a hot drink

Symptom: Derealization (feeling that things are not

real)

-Stare at a light on the ceiling for 1 minute, then try

to read for 1 minute. Repeat 8 times.

-Stare at self in a mirror for three minutes, then one

minute break. Repeat three times.

-Stare at a small dot (the size of a dime) posted on

the wall for three minutes.

-Stare at an optical illusion (rotating spiral,

“psychedelic” rotating screen saver, etc.) for two

minutes, then break for one minute. Repeat five

times.

2.12

Exposure Examples: “Internal Cue Exposure,” continued

Step Six: Ending exposure

Janet continues to practice the exposure for about 10

weeks, changing the exposure exercise about each

week as she moves up the hierarchy. This, with a

combination of external cue exposure and cognitive

skills, improves her panic symptoms and makes her

feel confident that she can manage a panic attack in

the future.

Step One: Pick a trigger

Janet decides to start with the “dizziness” trigger,

because it most often triggers panicky thoughts that

fuel the anxiety and make it worse.

Step Four: Starting exposure

Janet picks an item from the list in the “5-6” range on the

SUDS. She begins by practicing hyperventilating for one

minute, then one minute rest, alternating 8 times, which

takes her about 15 minutes. She tracks her progress using

the SUDS by rating her level of anxiety before, during and

after the exposure. She follows the rules of exposure

outlined in the section “The Exposure Formula,” and

repeats this daily for one week.

Step Three: Rate the hierarchy

Janet rates each potential exercise using the SUDS scale (see

“Exposure, Getting Started,” for more information on the

SUDS).

Step Two: Create a fear hierarchy

Janet lists the different interoceptive exercises she can use

to trigger some anxiety, using a list she got from her

therapist.

Step Five: Middle sessions of exposure

Once Janet feels like her level of anxiety for the

hyperventilation exercise has come down to around a

“3” during the exercise, she moves on to the next

harder exercise on the hierarchy. She continues to

practice these exposure exercises daily.

She continues to move up on the hierarchy until she

becomes more used to the feeling of being lightheaded

and dizzy, as well as more at peace with the possibility

that she will have a panic attack when she feels dizzy.

Since she also becomes worried when she experiences

feelings of tightness in her throat, she decided to do

some of these interoceptive exercises, as well.

Along with her interoceptive exposure exercises, she

added external cue exposure exercises (see previous

page) to places that she avoided because she was

worried about having a panic attack.

Along with her exposure practice, Janet and her

therapist worked on some of the thoughts that tend to

“fuel” the anxiety once it is triggered. We will talk

more about these thoughts in the Cognitive Therapy

Skills module of the manual, in a section entitled “The

Only Thing We Have to Fear Is…”

Exposure exercise (different ways to trigger the anxiety)

-Spin in a swivel chair for 1 minute, then 1 minute !

break. Do this sequence 8 times.!

-Shake head from side to side for 30 seconds, then !

30 second break. Do this 15 times.!

-While sitting, bend over and place head between !

legs for 30 seconds, then sit up quickly. Do this 15 !

times.!

-Hyperventilate (shallow breathing at a rate of 100-!

120 breaths per minute) for 1 minute, then normal !

breathing for 1 minute. Do this 8 times.!

Exposure exercise

-Spin in a swivel chair for 1 minute, !

then 1 minute break. Do this sequence 8 !

times.!

-Shake head from side to side for 30 !

seconds, then 30 second break. Do this !

15 times.!

-While sitting, bend over and place head !

between legs for 30 seconds, then sit !

up quickly. Do this 15 times.!

-Hyperventilate (shallow breathing at a !

rate of 100-120 breaths per minute) for !

1 minute, then normal breathing for 1 !

minute. Do this 8 times.!

Anxiety Rating

7!

9!

7!

5!

Let’s see what a course of interoceptive exposure for panic would look like. Janet is a 24 year-old woman with Panic Disorder. She

has panic attacks that seem to come from “out of nowhere” and she often worries about having another panic attack. Sometimes

she feels a little anxious and she begins to feel dizzy, which then makes her worry the panic will get worse; in fact, it usually does.

2.13

How long do I need to keep doing exposure?

During each practice, do the exposure until the anxiety comes down by about half from where it

started. Remember to use the SUDS scale to help you rate your anxiety.

Stay in the exposure situation for the full amount that you planned. We usually start with one hour

as a rule of thumb. If it is boring, good! Stay with it– it is better to be bored than anxious!

What if it really is dangerous?

If something really is dangerous, we will never ask you to do it. Exposure only works when we are avoiding or protecting ourselves

around something that is not dangerous, or not so dangerous it is worth avoiding.

Sometimes we are not sure if something is really dangerous, and it can be helpful to find out. Social situations are an example. We may

think that trying to talk to people at a party is dangerous, because people may be critical of us. If we like the idea of going to the party

but are afraid, perhaps it is best to get a sense of really how dangerous it is. We can do this using two different techniques:

1. Cognitive skills: looking at evidence to give us a sense of how dangerous it is.

We’ll be talking about this more in the next section of the manual.

2. Behavioral experiments: let’s try it out and get evidence first hand about whether or not it

is dangerous. Ask yourself what the real consequences are of having something bad happen.

How do I know when to move on to the next exercise?

When your anxiety is consistently below about a “3” on the SUDS for a few days, it is a good time to move to the next item on your

hierarchy.

1. If you are still avoiding things related to the trigger in your daily life, it is best to continue to do the exposure.

2. It is best to really dominate the trigger you are working on before deciding to stop exposure. This means that you may even

ramp up the exposure to ridiculous proportions. For example, if you are afraid of dogs, you might spend a weekend dog

sitting for a friend; you could pet, rub, and play with the dog. A social phobic might volunteer to be the MC for a company

event. Once someone becomes comfortable with something that difficult, it is easier to feel OK being exposure to the things

we normally see in our daily lives. Structured, daily exposure practice often takes weeks or months to complete,

depending on the type of problem. It is best to work with a mental health professional or exposure therapy workbook to

determine how long to continue to do exposure therapy.

3. There will always be times when we feel challenged by anxiety and may have the urge to avoid. In this sense, we are never

“done” with exposure; it becomes a way to address anxiety over the long term in our daily lives.

How do I know if I am done with exposure?

Each person must decide when they want to stop doing exposure and move to using exposure principles in the course of daily life (see

“The Freedom of Choice”). However, there are some points that may help you make this decision.

My exposure questions

Write down questions you have about exposure here and be sure to ask the group leader before you finish all the group sessions.

1. ________________________________________________________________________________________________?

2. ________________________________________________________________________________________________?

3. ________________________________________________________________________________________________?

2.14

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a chronic and often debilitating condition that affects

thousands of people in the United States each year. OCD is characterized by obsessions (anxiety

provoking, often intrusive thoughts) and compulsions (behaviors that aim to neutralize anxiety).

These compulsions are also called rituals; they are “safety behaviors” that make the person feel less

anxiety in the moment but serve to strengthen the anxiety in the long run.

When most people think about OCD they think about anxiety around contamination that may make

someone want to wash their hands over and over. OCD has many forms, however; unfortunately we

can’t go into them in detail here.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for OCD is called Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP). You now know

all about exposure; the “response prevention” part involves resisting the compulsions— we “prevent” or “block”

our impulse to give in and do the ritual. In this way, we really stand up to the OCD and don’t do what it tells us

to do.

For example, Jeremy tends to check things— irons, locks, stoves, the garage door– because

he feels anxious about the possibility that he has left something unlocked, plugged in,

turned on, etc. He will check locks over and over, and never feels reassured that the locks

are bolted, regardless of how many times he checks. He doubts himself constantly.

ERP for Jeremy involves purposely creating doubt that he locked something (exposure)

and resisting the urge to check (response prevention). He works to see the OCD as

something separate from himself: “It’s not me, it’s the OCD telling me to do that.” He

practices ERP for 60 minutes a day and works to eliminate all OCD rituals in his daily life.

ERP looks a lot like other types of exposure, in that we purposefully expose ourselves to the anxiety-provoking