© 2014 Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Washington. All rights reserved. 1

Benzodiazepine and Z-Drug Safety Guideline

Major Changes January 2022 .................................................................................................................. 2

Expectations for KFHPWA Providers ....................................................................................................... 2

Background .............................................................................................................................................. 2

Prescribing ............................................................................................................................................... 4

Management of Patients on Chronic Benzodiazepines or Z-Drugs ......................................................... 7

Tapering and Discontinuation ................................................................................................................ 10

Treatment of Withdrawal Symptoms ...................................................................................................... 13

Referral Criteria ...................................................................................................................................... 14

Evidence Summary ................................................................................................................................ 15

References ............................................................................................................................................. 22

Guideline Development Process and Team .......................................................................................... 26

Appendix 1

Table A. Long-acting benzodiazepine comparison ......................................................................... 27

Table B. Intermediate-acting benzodiazepine comparison ............................................................. 28

Table C. Short-acting benzodiazepine comparison ......................................................................... 29

Last guideline approval: January 2022

Guidelines are systematically developed statements to assist patients and providers in choosing appropriate health

care for specific clinical conditions. While guidelines are useful aids to assist providers in determining appropriate

practices for many patients with specific clinical problems or prevention issues, guidelines are not meant to replace

the clinical judgment of the individual provider or establish a standard of care. The recommendations contained in the

guidelines may not be appropriate for use in all circumstances. The inclusion of a recommendation in a guideline

does not imply coverage. A decision to adopt any particular recommendation must be made by the provider in light of

the circumstances presented by the individual patient.

2

Major Changes as of January 2022

• Tapering recommendations for benzodiazepine and Z-drug tapering have been updated.

• Benzodiazepine dose equivalencies to diazepam have been updated.

• New prescribing quantity limits for benzodiazepines and Z-drugs have been added.

• This FDA boxed warning about benzodiazepines has been added: “As of September 2020, the

FDA requires that all benzodiazepine prescriptions include a boxed warning that addresses the

serious risks of abuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions of

benzodiazepine medicines.”

Expectations for Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of

Washington Providers

Using protocols and standard documentation, Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Washington aims to

minimize practice variation in the management of patients on chronic benzodiazepine therapy to improve

patient safety and increase both patient and provider satisfaction.

Patients should not be prescribed benzodiazepines if currently taking any opioid.

See “Tapering and Discontinuation,” p. 10.

Benzodiazepines should not be combined with another benzodiazepine, Z-drug, or

muscle relaxant.

Patients treated with chronic benzodiazepines are risk-stratified to the highest

appropriate category by the prescribing clinician and the risk level is documented on the

Epic dashboard.

Patients prescribed chronic benzodiazepines shall have regular monitoring visits that:

• Occur at a frequency based on the patient’s risk stratification, and

• Include standard components. See “Required components,” p. 8.

Patients on chronic benzodiazepines shall receive all benzodiazepine prescriptions

from one physician and one pharmacy whenever possible. Clinicians treating a

patient on chronic benzodiazepines are expected to clarify and document—both among

themselves and with the patient—which clinician holds primary prescribing responsibility.

Background

Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (i.e., newer GABA receptor agonists, like zolpidem [Ambien]) are

overprescribed, and many prescription treatment plans are not supported by scientific evidence or

published guidelines. Despite warnings about the risks of long-term use of benzodiazepines, millions of

prescriptions are still issued for benzodiazepines and Z-drugs each year. As a result, clinicians may

encounter patients who have been prescribed benzodiazepines or Z-drugs on a long-term basis and are

averse to discontinuing these treatments.

The purpose of this guideline is fivefold:

• To reduce inappropriate prescribing of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs,

• To clarify when short-term prescribing of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs may be indicated,

• To confirm that long-term use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs is rarely, if ever, indicated,

• To aid primary care and mental health providers in identifying and managing patients on long-

term benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, and

• To provide appropriate advice to providers for discontinuing benzodiazepine and Z-drug use.

This guideline is in alignment with the National Permanente Medical Group 2021 Practice

Recommendations for Benzodiazepines & Non-Benzodiazepine Sedative-Hypnotics/Z drugs.

3

Target population

The recommendations in this guideline apply to patients who are:

• Already on prescribed long-term benzodiazepine or Z-drug therapy, or

• Being considered for initiation of short-term therapy with either drug class.

Exclusions

This guideline does not apply to:

• Patients who are using benzodiazepines illicitly. These patients may require treatment by an

addiction specialist or chemical dependency treatment provider and should be referred to Mental

Health and Wellness.

• Patients who are using benzodiazepines for treatment of alcohol withdrawal. See the

KPWA

Unhealthy Drinking in Adults Guideline.

• Patients who are using benzodiazepines for treatment of seizure disorder.

• Patients receiving palliative, hospice, or other end-of-life care.

• Other situations for which benzodiazepines may be appropriate:

o Urgent treatment of acute psychosis with agitation or acute mania

o Single-dose treatment of phobias, such as flying phobia

o Sedation for procedures

o Spasticity treatment

About benzodiazepines and Z-drugs

Benzodiazepines are gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor agonists that have hypnotic, anxiolytic,

muscle relaxant, and anticonvulsant properties. Benzodiazepines are commonly divided into three groups

according to how quickly they are eliminated from the body:

• Short-acting (half-life less than 12 hours), such as midazolam and triazolam.

• Intermediate-acting (half-life between 12 and 24 hours), such as alprazolam, lorazepam, and

temazepam.

• Long-acting (half-life greater than 24 hours), such as diazepam, clonazepam, clorazepate,

chlordiazepoxide, and flurazepam.

Z-drugs (e.g., zaleplon, zolpidem, and eszopiclone) were developed as alternatives to benzodiazepines.

• Like benzodiazepines, they are GABA receptor agonists, but because they have a different

structure they produce fewer anxiolytic and anticonvulsant effects.

• Z-drugs are not “safer” than benzodiazepines, and patients on benzodiazepines should not be

switched to Z-drugs to try to improve safety. (See drug alerts on next-day sedation with zolpidem

and eszopiclone.)

Both benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are considered a “high-risk medication in the elderly” and are listed on

the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria list

.

Chronic benzodiazepine use is daily or near-daily use of benzodiazepines for at least 90 days

and often indefinitely, and is defined as a minimum 70-day supply of benzodiazepines dispensed in

the previous 3 calendar months.

Chronic Z-drug use is daily or near-daily use of Z-drugs for at least 90 days and often indefinitely,

and is defined as a minimum 70-day supply of Z-drugs dispensed in the previous 3 calendar

months.

4

Prescribing

Except where noted, statements about benzodiazepines in this guideline also apply to Z-drugs.

Prescribing quantity limits (See huddle card)

• The default in KP HealthConnect for acute benzodiazepine (or Z-drug) prescribing limit is

7 tabs/caps.

• For benzodiazepine-naïve patients (≤ 7-day supply within last 180 days), the maximum

supply is 15 tabs/caps or 14-day supply (whichever is the lesser amount). There is currently

no equivalent limit for Z-drugs.

• Benzodiazepine and Z-drug prescriptions are limited to a 30-day supply.

In addition to prescribing quantity limits, the following Best Practice Alerts fire in HealthConnect to

alert providers when:

• A benzodiazepine (or Z-drug) is prescribed to a patient 65 years or older

• A second benzodiazepine prescription (or Z-drug) is ordered within 60 days (transition to chronic)

• A benzodiazepine (or Z-drug) is ordered when the patient is already taking an opioid

• A second benzodiazepine (or benzo + Z-drug) is ordered for a patient who is already taking a

benzodiazepine

Prescribing considerations

Before initiating a course of benzodiazepine treatment, the following should be considered:

• Do not prescribe benzodiazepines to patients already taking opioids, as this is associated

with increased risk of fatal overdose.

• Concurrent use of marijuana and benzodiazepines is not recommended.

• Explicitly advise the patient regarding the duration of treatment. Use of benzodiazepines beyond

2 weeks is not recommended.

• Use the lowest dose for the shortest time.

• Review with the patient the risks and side effects, including the risk of dependence. Keep in mind

that some patients will have difficulty discontinuing the medication at the end of acute treatment.

• Discuss exit strategies, such as tapering and/or transition to alternative treatments.

• Discuss alternative treatments, which may include:

o Antidepressant medications (e.g., SSRIs, SNRIs, tricyclic antidepressants)

o Psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy)

o Serotonergic agents for anxiety (e.g., buspirone)

o Anticonvulsant medications for restless leg syndrome (e.g., pramipexole, ropinirole,

gabapentin)

• The patient and health care provider should agree on one provider to be the benzodiazepine

prescriber for that patient. This designated prescriber should also be responsible for prescribing

other medications with abuse potential, specifically central nervous system (CNS) stimulants and

narcotics; otherwise the prescriber of benzodiazepines should closely coordinate care with those

who are prescribing other controlled substance medications.

• For patients who are prescribed chronic benzodiazepines for anxiety at a dose exceeding the

maximum dose listed in Appendix 1, consultation with a psychiatrist is recommended.

5

Note for patients aged 65 years and over

• If prescribing for patients who are frail or aged ≥ 65 years, consider initiating the medication at half

the adult dose.

• Individuals aged ≥ 65 years are especially vulnerable to the adverse effects of hypnotic drugs, as

metabolic capacities and rates decline with age. Patients in this age group are:

o More susceptible to CNS depression and cognitive impairment, and may develop confusion

states and ataxia, leading to falls and hip fractures.

o At risk of drug interaction with other medications.

o At risk of permanent cognitive impairment when using high doses of benzodiazepines (e.g.,

diazepam 30 mg or equivalent) on a regular basis.

Short-term use

In rare circumstances of acute, severe, and debilitating insomnia that is not responsive to behavioral

treatment, a one-time supply of ≤ 15 pills zolpidem 5 mg at bedtime for a brief period while the patient’s

evidence-based behavioral insomnia treatment is being adjusted, with no refills, is recommended. Ensure

recommendations in the KPWA Insomnia Guideline have been followed prior to consideration of higher-

risk treatments.

• Physical dependence rapidly occurs within 2 weeks of continuous daily use.

• Avoid in patients taking opioids and other sedative-hypnotics or substances with sedative effects

such as alcohol, due to an increased risk of respiratory depression.

• Avoid in patients aged 65 years and over, due to increased adverse effects including fall risks and

cognitive impacts.

Long-term use

Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are not recommended for long-term use (longer than 2 weeks), except in

exceptional circumstances (e.g., for terminally ill patients). There is no evidence to support the long-term

use of these drugs for insomnia or any mental health indication. There are concerns regarding their

safety.

• Insomnia: The treatment period should not exceed 2 weeks, as sleep studies have shown that

sleep patterns return to pre-treatment levels after only a few weeks of regular use.

• Anxiety: Continuing beyond 2 weeks will result in loss of effectiveness, development of tolerance

or dependence, potential for withdrawal symptoms, persistent adverse effects, and interference

with the effectiveness of definitive medications and counseling.

Contraindications

• Concurrent use of another benzodiazepine, Z-drug, muscle relaxant, or opioid

• Active or history of substance use disorder

• Pregnancy or risk of pregnancy

• Treatment with opioids for chronic pain or agonist therapy for opioid use disorder

• Medical and mental health problems that may be aggravated with benzodiazepines, such as

fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, somatization disorders, depression, bipolar disorders

(except for urgent sedation in acute mania), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, kleptomania,

and other impulse disorders

• Cardiopulmonary disorders such as asthma, sleep apnea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,

and congestive heart failure, as benzodiazepines may worsen hypoxia and hypoventilation

Adverse effects of benzodiazepines

• There is an association between benzodiazepine use and dementia, increased rate of falls, and

increased risk of hip fracture.

• Tolerance to anxiolytic effects, which may develop after a few weeks of use. (This does not apply

to Z-drugs because they are not anxiolytic.)

6

Adverse effects of both benzodiazepines and Z-drugs

• Dependence: Potent benzodiazepines with short or intermediate half-lives (e.g., alprazolam,

lorazepam) appear to carry the highest risk of causing problems with dependence. Psychological

or physical dependence can develop over a few weeks or months and is more likely to develop

with long-term use or high doses, and in patients with a history of anxiety problems.

• Tolerance to the hypnotic effects, which may develop after only a few days of regular use

• Daytime somnolence

• Dizziness

• Impaired driving performance leading to an increased risk of traffic accidents

• Depression and increased anxiety

• Slowness of mental processes and body movements

• Particularly high risk of overdose when combined with sedative drugs, such as opioids or alcohol

• Increased risk of mortality

• Increased risk of cognitive impairment and delirium

• Increased risk of falls and fractures, especially among older adults

As of September 2020, the FDA requires that all benzodiazepine prescriptions include a boxed warning

that addresses the serious risks of abuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions of

benzodiazepine medicines. See

https://www.fda.gov/media/142368/download for more information.

7

Management of Patients on Chronic Benzodiazepines

and Z-Drugs

All patients should be encouraged to discontinue chronic use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. Providers

should create a treatment care plan to help patients with tapering and discontinuation.

• For most people in primary care settings even a minimal intervention, such as a letter with self-

help information from the treating physician or a single brief consultation, can be effective in

reducing or stopping benzodiazepine use.

• For patients who do not want to stop the drugs, discuss the benefits of stopping. Set the

expectation of revisiting the topic at least annually, and more frequently when there are changes

in the patient’s care plan.

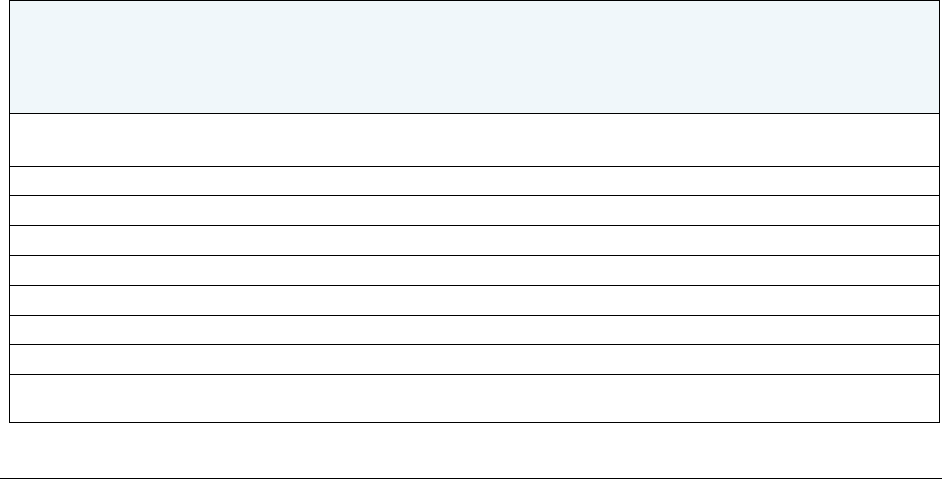

Risk stratification and intensity of monitoring

Table 1. Risk-based monitoring for CHRONIC benzodiazepine or Z-drug use

1

Risk level

Criteria

Content of follow-up

Minimum follow-up

interval

2

HIGH

• Age ≥ 65 (HRME)

• Age < 25 (increased risk of

substance use disorder)

• More than 1 benzo (overdose

risk)

• Benzo + Z-drug (overdose risk)

• Benzo + opioid (overdose risk)

• History of substance use

disorder

• Use of alcohol or cannabis

• Use of gabapentin/pregabalin

• COPD, severe or uncontrolled

respiratory disease, or at risk of

respiratory depression

• History of overdose

• PTSD

• Fall risk

• Problems following benzo care

plan

• Evaluation for side effects

(e.g. falls)

•

PDMP Summary check at

every follow-up

•

Use .BENZOVISIT to

document note

•

Use .BENZOCAREPLAN

•

Use .BENZOPROBLIST

and/or GHC 30

•

Insomnia Severity Index if

for insomnia

•

MH Monitoring Tool and

GAD7 if for anxiety

• Office/Video

Provider visit

every 6 months,

including at least

one face-to-face

office visit per year;

others can be

virtual

• UDS required

annually

STANDARD

None of the above

Same follow-up as above

• Provider visit

annually; must be

face-to-face office

visit

• UDS optional

1

Monitoring visits are required for chronic benzodiazepine or Z-drug use only. The above

recommendations do not apply to short-term use of these medications.

2

Patients taking opioids with benzodiazepines must have a follow-up visit every 3 months at a

minimum. See the KPWA COT Safety Guideline.

For detailed pharmacological information including maximum dosing, monitoring recommendations, and

metabolites that may be present in urine drug screen results, see Appendix 1.

8

Required components of a chronic benzodiazepine or Z-drug visit

1. Screening, history, and physical exam

When initiating or monitoring chronic benzodiazepine or Z-drug therapy, perform and document the

following:

• Use the SmartPhrase .BENZOVISIT to include all the recommended elements of the visit.

• Medical screening for issues that affect sedative risk (e.g., COPD, CHF, renal or hepatic

compromise, obstructive sleep apnea, pregnancy risk)

• Patient history and physical exam

• Insomnia assessment using ISI if drugs are being used for insomnia.

• Depression, anxiety, alcohol and drug use screening with MH monitoring tool.

Note: Annual screening for mental health issues is part of adult standard care.

2. Prescription monitoring

Check the patient’s record in the Washington State Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP)

Summary to determine whether the patient is receiving benzodiazepine dosages or dangerous

combinations that put them at high risk. The PDMP is a central database that keeps track of schedule II–

V medications that patients receive at any pharmacy in the state of Washington. Clinicians are required to

check this database every time controlled substances are prescribed for a patient. Data for all controlled

substances can be found in the WA PDMP Summary activity in HealthConnect.

3. Urine drug screening

Urine drug screening (UDS) provides objective data regarding patients on chronic benzodiazepines and

can be used to directly improve patient safety. For their safety, it is important that patients take

benzodiazepines as prescribed, and this test helps assess whether they are doing so. UDS should also

be ordered when seeing patients already on benzodiazepines who are new to the health plan and have

no record of recent UDS.

UDS is for medical purposes only. KPWA does not collect samples for use in a court of law or for

workplace testing.

Clinicians should have a discussion with the patient before the UDS that includes:

• The purpose of testing

• What will be screened for

• What results the patient expects to see

• Prescriptions or any other drugs the patient has taken

• Actions that may be taken based on the results of the screen

• Possibility of cost to the patient

Patients should be notified that the results will become part of their permanent medical record. For more

detailed information on urine drug screening, see Drug Screen Ordering & Interpretation.

9

For patients taking benzodiazepines, use UDS for pain management, and choose either the benzos

only, opioids only, or opioids and benzos option, for screening and confirmation. This UDS does not

include alcohol, fentanyl, methylphenidate, tramadol, or Z-drugs (eszopiclone, zaleplon and zolpidem). If

a patient is prescribed any of these excluded drugs, a separate lab test will need to be ordered for each

specific drug that the patient is taking.

Order serum drug screen for patients who are taking diuretics or cannot produce urine.

4. Documentation and coding

Include GHC.30 (chronic benzodiazepine care plan) on the problem list and use the SmartPhrases

.BENZOPROBLIST and .BENZOVISIT.

5. Care plan

The SmartPhrase .BENZOCAREPLAN includes all the elements of the treatment plan and must be used

in the After Visit Summary for the visit to satisfy requirements for the care plan update.

10

Tapering and Discontinuation

Tapering considerations

Taper planning must be individualized based on the patient's clinical needs, indication for taper, and

ability to comply with the care team's tapering instructions, and on the provider’s clinical judgment.

• Determine initial step of taper and document rationale in medical record using the SmartPhrase

.BENZOTAPER (synonym: .ZDRUGTAPER).

• Do not reverse a taper. A temporary pause in tapering may be indicated to mitigate side effects.

• Assess the patient’s response to the initial dose reduction in the first 1 to 4 weeks.

• Assess the patient’s underlying condition for which the drugs were originally prescribed; discuss

alternative treatments as needed.

• Assess the patient for readiness/suitability to taper off benzodiazepines. Patients are considered

suitable if they:

o Are willing and committed, with adequate social support,

o Have no previous history of complicated drug withdrawal, and

o Do not have an indication for rapid discontinuation (see Table 3).

If a taper is needed but the patient does not meet the criteria above, or if you have specific

questions about tapering, consult Mind Phone or Pharmacy.

• Cognitive behavioral therapy is recommended to help the patient cope with rebound anxiety and

to assist with the withdrawal process.

• Consider referral to a specialist for patients who:

o Have a history of alcohol use disorder or other substance use disorders,

o Have a concurrent severe medical or psychiatric disorder,

o Are on a high dose,

o Are taking stimulants or opioids concurrently, or

o Have a history of drug withdrawal seizures.

• Reassess taper weekly to monthly based on patient’s response, and prior to each subsequent

dose reduction.

Z-drug recommendations

Considering the frequency at which the patient takes the medication, choose one of these options:

• Stop the Z-drug and start an alternative medication (such as melatonin, trazodone, doxepin,

or mirtazapine).

• Taper the Z-drug by decreasing the number of days per week the patient takes the medication

(for example: take 6 nights per week x 2 weeks, then 5 nights per week x 2 weeks, and so on).

• For chronic, long-term Z-drug use (Bélanger 2009):

Table 2. Methods for tapering of chronic Z-drug therapy

Z-drug

Taper method

Zolpidem

• Reduce by ~25% of original dose each week or every other week

• If dose > 10 mg/day IR or 12.5 mg/day CR: slower rate of tapering in

conjunction with CBT-I

Eszopiclone

• Reduce by ~25% of original dose (up to 1 mg) each week or every other week

• If dose > 3 mg/day: slower rate of tapering in conjunction with CBT-I

Zaleplon

• Reduce by ~25% of original dose each week or every other week

• If dose > 20 mg/day: slower rate of tapering in conjunction with CBT-I

11

Benzodiazepine tapering recommendations

The most effective strategy to manage benzodiazepine discontinuation and prevent adverse outcomes

associated with severe withdrawal—such as severe seizures—is a gradual taper of benzodiazepines.

• If the patient is established on a long- or intermediate-acting benzodiazepine, taper the

medication per Table 3 or see “Switching to a longer-acting benzodiazepine,” p. 12.

• If the patient is established on a short-acting benzodiazepine or one that doesn’t easily allow

for small dose reductions, switch to diazepam (patients 64 or younger) or lorazepam (patients

65 and older) and gradually taper per Table 3 or “Switching to a longer-acting benzodiazepine,”

p. 12.

• Use the SmartPhrase .AVSBENZOTAPER to educate patients about the tapering process.

Table 3. Clinical indications and methods for tapering of chronic benzodiazepine therapy

Indication

Taper method

•

Function is not improved

• Tolerance has developed with long-term prescription

SLOW

10% every 2–4 weeks

•

Medication adverse effects indicate risks are greater than

benefit

• Comorbidities increase risk of complication

MODERATE

10% every week

•

Urine drug screen is consistent with substance abuse

concerns,

• Significant risk of respiratory depression due to unstable

clinical condition or recent overdose, or

• Patient’s behavior suggests possible misuse or diversion of

medication. Such behaviors might include:

o Selling prescription drugs

o Forging prescriptions

o Stealing or borrowing drugs

o Frequently losing prescriptions

o Aggressive demand for benzodiazepines

o Injecting oral/topical benzodiazepines

o Unsanctioned use of benzodiazepines

o Unsanctioned dose escalation

o Concurrent use of illicit drugs, including opioids

o Getting benzodiazepines from multiple prescribers

o Recurring emergency department visits

o Concurrent use of alcohol

RAPID

25% per week

and/or

Refer patient for chemical

dependency or addiction

counseling. (See Referral

Criteria, p. 14.)

• A subset of patients will experience clinically significant withdrawal symptoms even with 10%

dose reductions and/or gradual tapering. Consider switching these patients to a longer-acting

benzodiazepine; see “Switching to a longer-acting benzodiazepine,” p. 12.

• Tapering should be guided by individual choice and severity of withdrawal symptoms. Drug

discontinuation may take 3 months to a year or longer. Some people may be able to discontinue

the drug in less time.

• Review the patient’s progress frequently to detect and manage problems early and to provide

advice and encouragement during and after tapering. Development of withdrawal symptoms can

be quite variable and insidious during a taper. A high index of suspicion for withdrawal-related

etiology should be held if new symptoms arise during a taper. (See “Treatment of Withdrawal” p.

13 for more information about withdrawal symptoms.)

• If the first attempt is unsuccessful, consider switching to long-acting benzodiazepines in second

attempt (see “Switching to a longer-acting benzodiazepine,” p. 12).

• If patient compliance is an issue, consider dispensing medication in 7- or 14-day increments.

12

Switching to a longer-acting benzodiazepine for tapering

Diazepam (patients aged 64 and under)

There is a lack of good-quality evidence on switching to diazepam, but it can be considered for some

people because diazepam has a long half-life (20–80 hours) and thus has fewer fluctuations in plasma

levels. It is also available in a variety of strengths and formulations, which facilitates step-wise dose

substitutions from other benzodiazepines or Z-drugs and allows for small incremental reductions in

dosage. Switching is best carried out gradually, usually in a step-wise fashion.

Switching to diazepam should be considered for individuals who are:

• Using short- to intermediate-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., alprazolam and lorazepam)

• Using preparations that do not easily allow for small reductions in dose (e.g., alprazolam or flurazepam)

• Experiencing difficulty or likely to experience difficulty withdrawing directly from temazepam or Z-

drugs due to a high degree of dependency (associated with long duration of treatment, high

doses, or history of anxiety problems)

Alprazolam (Xanax) note: Care should be taken not to taper alprazolam too rapidly or to switch to another

benzodiazepine too abruptly, as withdrawal seizures are more prone to occur with alprazolam than with

other benzodiazepines. If difficulty tapering the last 1–2 mg of alprazolam: taper more gradually

(0.25 mg/week) or substitute diazepam gradually over 1 week and taper as usual.

Lorazepam (patients aged 65 and over)

Switching to diazepam in patients aged 65 and over is not recommended, as case reports suggest that it

may be associated with delirium. For older adults, lorazepam, oxazepam, and temazepam are the safest

options because they don’t have metabolites that can accumulate. Of these, lorazepam is the best in

terms of dosing options—available as 0.5, 1, and 2 mg tabs, and as 2 mg/mL oral solution.

How to make the switch

• Substitute diazepam or lorazepam for one dose of the current benzodiazepine at a time, usually

starting with the evening or nighttime dose to avoid daytime sedation. Replace the other doses,

one by one, at intervals of a few days or a week until the total approximate equivalent dose

(Table 4) is reached before starting the reduction.

•

For patients on diazepam, the long half-life can enable them to take a single dose at night or a

twice-daily dose.

•

For patients on lorazepam, twice-daily dosing is recommended.

Table 4. Approximate dose equivalent to 5 mg diazepam

Note: Data shown are approximate equal potencies relative to diazepam as there is considerable variation in dose

equivalents depending on the source of information. The sources used in this table are Lexicomp and UpToDate.

Patients should be monitored closely during the tapering process to prevent over- or under-dosing. These dosing

conversions are intended to be used only in the tapering process, not for initiation of therapy.

Trade name

Half-life (hours)

Dose equivalent to

5 mg diazepam

Alprazolam

Xanax

12–15

0.5 mg

Chlordiazepoxide

Librium

5–30

10 mg

Clonazepam

Klonopin

18–50

0.25–0.5 mg

Diazepam

1

Valium

20–80

5 mg

Lorazepam

Ativan

10–20

1 mg

Temazepam

Restoril

3.5–18.5

30 mg

Triazolam

Halcion

1.5–5.5

0.25 mg

1

Prescribe 5 mg or 2 mg diazepam tablets only. Starting dose should not exceed 40 mg. Consult with Mental

Health and Wellness if considering a higher dose.

13

Treatment of Withdrawal Symptoms

Acute signs and symptoms of withdrawal

Anxiety-related withdrawal symptoms are common, and include restlessness, agitation, tremors,

dizziness, panic attacks, palpitations, shortness of breath, sweating, flushing, shakiness, difficulty

swallowing, poor sleep, sensation of choking, and chest pain. There is a wide range of other, less

common acute withdrawal symptoms, such as seizures, bowel/bladder problems, changes in appetite,

tiredness, faintness, poor concentration, tinnitus and delirium.

Long-term signs and symptoms of withdrawal

Some withdrawal symptoms can persist and may take months or years to resolve, including anxiety,

fatigue, depression, poor memory and cognition, motor symptoms (pain, weakness, muscle twitches,

jerks, seizures), depersonalization, psychosis,

paranoid delusions, rebound insomnia, and abnormal

perception of movement.

Prevention and treatment of withdrawal symptoms

Table 5. Medications used to prevent or treat withdrawal symptoms during gradual taper from

chronic benzodiazepines or Z-drugs

Symptom

Medication

Dosing

Seizure prevention

Carbamazepine

1

Start 200 mg twice daily, adjust dose weekly up to

400 mg twice daily. Continue for 2–

4 weeks after stopping

benzodiazepines and then taper anticonvulsant.

Valproic acid

1, 2

or

Divalproex sodium EC

1, 2

Start 500 mg twice daily, adjust dose weekly up to

2,000 mg daily. Continue for 2–4 weeks after stopping

benzodiazepines and then taper anticonvulsant.

Tachycardia, hypertension,

tremors, sweats, anxiety,

restlessness

Propranolol

10 mg three times daily as needed for 3 days

Hypertension, tremors,

sweats, anxiety,

restlessness

Clonidine

0.1 mg three times daily as needed for 3 days

Anxiety, restlessness

Gabapentin

100–300 mg every 6 hours as needed

Hydroxyzine

3

or

Diphenhydramine

3

25 mg every 6 hours as needed

Insomnia

4

Gabapentin

100–300 mg daily before bed as needed

Hydroxyzine

3

or

Diphenhydramine

3

25–50 mg daily before bed as needed

Nausea

Promethazine

3

25 mg every 6 hours as needed

Metoclopramide

10 mg every 6 hours as needed

Dyspepsia

Calcium carbonate

500 mg 1–2 tabs every 8 hours as needed

Mylanta, Milk of Magnesia

Follow package instructions.

Pain, fever

Acetaminophen

500 mg every 4 hours as needed, not to exceed 3,000 mg

in 24 hours

Ibuprofen

600 mg every 6 hours as needed

1

In patients with liver impairment, consider topiramate, gabapentin or levetiracetam. Check CBC and liver function

tests at baseline.

2

Check CBC and liver function tests at baseline and every 3 months during treatment.

3

These are high-risk medications for the elderly. Please consider alternatives for patients aged 65 and older.

4

Patients with chronic insomnia or worsening anxiety during the taper often do better with cognitive behavioral

therapy to address these symptoms during the taper. Refer these patients to Mental Health Access for this

specific therapy.

14

Referral Criteria

Consider consultation with Mental Health and Wellness for patients who have any of the following:

• A history of alcohol use disorder or other drug use disorders

• A concurrent severe psychiatric disorder

• Concurrent use of stimulants or opioids

• A history of drug withdrawal seizures

• Suicidal thoughts

15

Evidence Summary

The Benzodiazepine and Z-drug Safety Guideline was developed using an evidence-based process,

including systematic literature search, critical appraisal, and evidence synthesis.

As part of our improvement process, the Kaiser Permanente Washington guideline team is working

towards developing new clinical guidelines and updating the current guidelines every 2–3 years. To

achieve this goal, we are adapting evidence-based recommendations from high-quality national and

international external guidelines, if available and appropriate. The external guidelines should meet several

quality standards to be considered for adaptation. They must: be developed by a multidisciplinary team

with no or minimal conflicts of interest; be evidence-based; address a population that is reasonably similar

to our population; and be transparent about the frequency of updates and the date the current version

was completed.

In addition to identifying the recently published guidelines that meet the above standards, a literature

search was conducted to identify studies relevant to the key questions that are not addressed by the

external guidelines.

External guidelines meeting KPWA criteria for adaptation/adoption

2021 National Permanente Medical Group Practice Recommendations for Benzodiazepines & Non-

Benzodiazepine Sedative-Hypnotics/Z Drugs (for Adults 18 and Over). Last edited March 17,

2021.

2020 Canadian Guidelines on Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonist Use Disorder Among Older

Adults (Conn 2020)

2019 Practice Guidelines: Deprescribing Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists for Insomnia in Adults

(Croke 2019)

2018 Deprescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline.

(Pottie 2018)

Key questions addressed in the KPWA evidence review

Comparative effectiveness of benzodiazepines (BZDs) and cognitive behavioral therapy

(CBT) used for management of anxiety disorders in adults

• Most guidelines on the treatment of anxiety disorders published by different organizations and

countries recommend psychotherapy (including CBT) mainly as a first-line treatment for anxiety

disorders. The majority of the guidelines recommend that use of BZD anxiolytics may only be

used for a short term (3–6 months). However, both the United Kingdom’s NICE (2014) and the

German guidelines (Bandelow 2021) do not recommend the use of BZD anxiolytics in the

treatment of anxiety disorders, even for short-term use, except for in critical or exceptional

situations.

• There is a lack of recent studies or meta-analyses on the comparative effectiveness of

benzodiazepines and cognitive behavioral therapy in adults.

o A meta-analysis conducted by Bandelow and colleagues (2015) evaluated the pre-post

effect sizes for different pharmacological, psychological, and combined treatments used

for the three main anxiety disorders (panic disorder with or without agoraphobia,

generalized anxiety disorder, and social anxiety disorder). Its results suggest that the

average pre-post effects of each of the benzodiazepine, selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitor (SSRIs), and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRIs) classes of

medications were higher compared to CBT used alone, but not when CBT was used in

combination with drug therapy.

o An earlier London and Toronto study (Marks 1993) showed that panic attacks ceased

with placebo, CBT, or drug therapy (alprazolam), and that relapse was common after

alprazolam was stopped, but the gains persisted to 6-month follow-up after the CBT was

stopped.

16

Comparative effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of benzodiazepines or the analogous

Z-drugs versus other pharmacological therapies prescribed for managing anxiety

disorder in adults (sertraline, venlafaxine, escitalopram, citalopram, fluoxetine,

duloxetine, Buspar, mirtazapine)

There is insufficient published evidence from valid head-to-head trials to determine the comparative

efficacy, tolerability, and safety of benzodiazepines versus SSRIs or SNRIs used for the treatment of

anxiety disorders. The published trials mainly compared the pharmacological therapies (antidepressants

in general, serotonergic antidepressants, and benzodiazepines) used for the treatment of anxiety

disorders versus placebo.

The trials on benzodiazepines for the treatment of anxiety disorders were smaller studies that compared

one BZD compound versus another BZD or versus placebo; were published more than three decades

earlier under different requirements (e.g., as indicated in Gomez 2018); and companies sponsoring drug

trials were not required to make negative/null findings publicly available. The investigators also indicated

that, “most of the BZD trials used compounds with medium-long half-lives (e.g., lorazepam, diazepam),

which have different anxiolytic and side-effect profiles than shorter-acting compounds (e.g., alprazolam).

The slower-acting BZDs are associated with less risk of dependence relative to alprazolam but may be

potentially associated with future development of cognitive decline.”

• Du 2021 network meta-analysis that assessed the efficacy and acceptability of different types of

antidepressants and benzodiazepines for the treatment of panic disorder in adult patients

suggested that escitalopram, venlafaxine, and benzodiazepines had greater efficacy and

acceptability than the placebo. Paroxetine, sertraline, fluoxetine, citalopram, and clomipramine

were also more efficacious than placebo, but paroxetine and sertraline were statistically

significantly less tolerated than benzodiazepines (based on indirect comparisons).

• Gomez 2018 meta-analysis that also indirectly compared the efficacy of benzodiazepines and

serotonergic anti-depressants for adults with generalized anxiety disorder showed that the overall

effect of SSRIs, SNRIs, and BZDs combined was mild to moderate compared placebo, and that

BZDs had a significantly larger effect compared to SSRIs and SNRIs.

• Shinfuku 2019 meta-analysis examined the effectiveness and safety of long-term benzodiazepine

use in anxiety disorders. The indirect comparison between BZDs and antidepressants showed no

significant difference in effect size between the two classes, and that BZDs had a lower risk of

discontinuation.

• Quagliato 2019 meta-analysis that compared the adverse events associated with BZDs versus

SSRIs in acute panic disorder treatment suggest that BZDs may be more tolerable than SSRIs in

the course of short-term treatment of panic disorder.

• Serious side effects, such as falls, fractures, and cognitive impairment, were not reported.

The results of the published meta-analyses have to be interpreted cautiously due to the limitations of

indirect analysis and the methodological quality of the included trials.

Association between benzodiazepines or Z-drugs for treatment of anxiety disorders or

other health conditions and the risk of cognitive decline and dementia in older adults

The results of the published studies and meta-analyses on the association between the use of BZDs and

related drugs and cognitive decline and dementia are mixed. While some systematic reviews and meta-

analyses suggest an association (Baek 2020, Lucchetta 2018, Penninkilampi 2018), others show no

association (Hafdi 2020, Nafti 2020).

All published studies are observational prospective or case-control, with variations in: population size and

characteristics; data source; setting; degree and definition of cognitive decline; diagnostic criteria for

cognitive decline; definition and duration of BZD use; duration of follow-up; adjustment for potential

confounders; outcome measures; and other areas.

The majority of the published studies obtained their data from claims and prescription databases; the

information on BZD exposure was measured at baseline but not during or at the end of the studies, which

17

may overestimate the long-term use of the drugs. Moreover, data on medication dosage was not

collected in the majority of studies, which does not allow for examining the effect of the exposure by

dosage.

In terms of evidence regarding any association of Z-drugs specifically with dementia, the majority of

studies combined BZDs with Z-drugs in the analysis, and the few that performed sub-analysis suggested

that risk of dementia with Z-drugs was similar to that seen with benzodiazepines.

Due to the design of the published studies, it is difficult to determine whether the association found by

some is due to causality or reverse causation (protopathic bias), as insomnia, anxiety, and depression

were found to be prodromal symptoms of dementia and can occur several years before a clinical

diagnosis of the disease (i.e., there is uncertainty about whether the BZD use was responsible for causing

dementia or if it was used to treat its early symptoms).

There is also a potential indication bias, which occurs when the risk of an adverse event is related to the

indication for medication use but not the use of the medication itself.

Only RCTs can determine a cause-and-effect association but are not likely to be performed for ethical

reasons.

Association between the prescribing pattern (dose, type, and duration of use) of

benzodiazepines or Z-drugs for the treatment of anxiety disorders or other health

conditions and increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia in older adults

There is insufficient published evidence to determine the association between the pattern of using

benzodiazepines and Z-drugs (dose, type, and duration of use) and the risk of cognitive decline and

dementia in older adults. The published studies consisted of observational cohort studies, nested case

control studies, and post hoc analyses of a large RCT, the majority of which were conducted overseas.

The results of the studies were inconsistent in regard to the differences between long-acting and short-

acting benzodiazepines, and between various exposure loads (duration and dose).

• Penninkilampi systematic review and meta-analysis (2018) suggested that short-acting but not

long-acting benzodiazepines were significantly associated with an increased risk of dementia.

• A post hoc analysis of a large prospective study (Hafdi 2020) showed no association between the

consistent use of BZD for 2 years and the risk of dementia in the cohort studied.

• A cohort study conducted by Osler (2020) showed that the number of prescriptions and the

cumulative dose of benzodiazepines or Z-drugs at baseline were not associated with dementia;

however, the analysis of the nested case-control study conducted by the same group of

investigators showed slightly higher odds of developing dementia among patients with the lowest

rate of benzodiazepine or Z-drug use compared with patients with no lifetime use. Patients with

the highest rate of use appeared to have the lowest odds of developing dementia.

• Tapiainen 2018 nested case-control study showed that

o Any use of BZD and related drugs (Z-drugs) (BZDR) was associated with an increased risk

of Alzheimer’s disease (OR 1.19, 95% CI, 1.17 to 1.21) compared with no use.

o Similar associations were observed with the use of BZD or Z-drug alone, and with

short/medium- and long-acting BZDRs.

o A dose-response relationship between BZDR use and Alzheimer’s disease was observed,

but adjustment for other psychotropics removed this relationship, suggesting that the

association was at least partially explained by more frequent use of antidepressants.

Analysis based on duration of use showed that the risks in all drug categories were the

highest in the two groups with longest duration of use (1–5 years and > 5 years) and

slightly lowered in groups with shorter use compared to nonusers of each drug. In the fully

adjusted model, no risks were observed in the shortest use (1 day to 1 month) and

increased until the second longest (1–5 years) duration of use group.

Larger studies with enough statistical power and follow-up duration are needed to determine whether

there are differences between long-acting and short-acting benzodiazepines, and between various

exposure loads (duration and dose).

18

Association between benzodiazepines and Z-drugs and increased risk of accidents, falls,

and hip fractures in older adults

• The recent published literature on the association between the use of benzodiazepines and Z-

drugs and the increased risk of falls, fractures, and injuries consists of meta-analyses of

observational studies (Treves 2018, Poly 2020).

• The results of the reviewed meta-analyses suggest that

o Benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are associated with an increased risk of hip fractures and

falls. The risk observed was more pronounced with fractures, as data on falls is more often

based on self-report, which may not be always accurate.

o The risk of hip fracture associated with BZD and Z-drug use is significant among new

users, current users, and previous users.

o Subgroup analysis of Poly 2020 meta-analysis suggests that both the short- or long-acting

BZDs are associated with hip fracture.

o Z-drugs are not safer than BZDs, and short-acting benzodiazepines are not safer than the

long-acting drugs.

• Large prospective studies with minimal bias and controlling for confounding factors are needed to

provide more accurate evidence on the risk of different benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, as well as

their dose, type, and duration of use on the risk of fracture.

Association between benzodiazepine use and risk of death among adults using the drugs

for the treatment of insomnia and/or anxiety

Published studies (Xu 2020, Parsaik 2016, Patorno 2017) suggest an association between the use of

benzodiazepines and the risk of all-cause mortality. There is insufficient evidence, however, to determine

whether the observed association is a causal relationship.

Association between use of benzodiazepines or Z-drugs in adults and risk of suicide

Evaluating the relationship between benzodiazepines and suicide is challenging due to the potential of

indication bias. Benzodiazepines are mainly prescribed for patients with sleep disorders or anxiety. Sleep

disorders have been identified as a risk factor for suicide ideation, nonfatal suicide attempts, and suicide

(Drapeau 2017), and anxiety has been found to increase the risk of suicide ideation and attempts

(Bentley 2016).

The literature search did not identify any valid long-term prospective studies that evaluated the causal

association of benzodiazepines with the risk of suicide. Only case-control studies or retrospective studies

with data from registers were found.

• The published literature suggests that there may be an association between the use of BZD and

the risk of suicide, and that the risk of suicide appears to increase with the increasing duration of

BZD use.

• Cato and colleagues’ (2019) case-control study examined whether benzodiazepines are

associated with an increased risk of suicide, by comparing psychopharmacological interventions

between psychiatric patients who committed suicide and matched controls. The analysis showed

that BZD prescriptions were more common among cases than controls, with an odds ratio of 1.89

(95% CI, 1.17 to 3.03), and that the association remained significant after adjustment for previous

suicide attempts and somatic hospitalizations. No statistically significant differences were seen

between the groups in the use of any other subtype of psychopharmaceutical agent. However,

this study is limited by the potential for indication bias.

• Boggs (2020) retrospective case control study that evaluated the association between suicide

death and concordance with benzodiazepine guidelines showed a significant association between

the duration of BZD use and suicide death starting with just 1–2 dispensings. The authors

explained that this may be due to higher disease severity associated with benzodiazepine

prescribing and/or increased risk for benzodiazepine overdose. The analysis also showed that

antidepressants and/or psychotherapy treatments lessened the odds for suicide death among

those with 3–8 benzodiazepine dispensings compared to those who used benzodiazepines as

monotherapy.

• There is insufficient evidence to determine the association between patterns of BZD and Z-drug

dose and type with the risk of suicide.

19

• There is no evidence to date to determine that the association observed is a cause-and-effect

relationship and that it is not due to confounding by indication or other factors.

Incidence of long-term use of benzodiazepines or Z-drugs in adults who start new

treatment with these agents, and factors associated with development of long-term use

in these new starts

• Low- to moderate-quality evidence from published studies conducted in the US (Gerlach 2018)

and overseas (Taipale 2020) suggests that the incidence of long-term use of BZDRs ranged from

20% to around 40% depending on the definition of long-term use (which varied from ≥ 6 to ≥ 12

months), country, population studied, the indication for prescribing a BZDR, index BZD used, and

day supply of index prescription.

• The factors associated with long-term use of BZDR in general include older age, receipt of social

benefits, psychiatric comorbidities, poor sleep quality, substance abuse, and use of opioids

and/or antidepressants, index BZDR used, and the amount supplied in the initial prescription.

• Takano 2019 study showed that compared to BZDs with short half-life, those with medium half-

life and not long half-life in the initial prescription were associated with the risk of long-term use.

• Wright and colleagues’ (2021) cohort study that examined the frequency of use and persistent

use of benzodiazepines among patients undergoing major and minor surgical procedures showed

that one-fifth of benzodiazepine-naïve patients prescribed a perioperative benzodiazepine

continued its use for the duration of follow-up (90–180 days). Factors associated with persistent

use of benzodiazepines were Medicaid recipients, age ≥ 70 years, female gender, presence of

medical comorbidities, and/or a diagnosis of anxiety, depression, insomnia, or substance use

disorder.

Benefits and harms of deprescribing or tapering benzodiazepines or Z-drugs compared

to their continued use in adult patients prescribed these drugs daily for longer than 2

weeks, and for 90 days, for anxiety disorders or insomnia

Based on a systematic review of the literature by the Canadian Clinical Practice Guideline development

team (GDT) (Pottie 2018) to investigate the benefits and harms of deprescribing of benzodiazepine

receptor agonist (BZRA) use for patients with insomnia, the GDT concluded that the findings suggest that

tapering improves cessation rates compared to usual care without an increase in severity of withdrawal

symptoms or worsening of sleep.

• Tapering of BZRAs improved cessation rates (low-quality evidence) at 3 months follow-up (RR

3.45, 95% CI, 1.49 to 7.99) when compared to usual care (not receiving any help with

benzodiazepine reduction).

• Tapering did not result in increased withdrawal symptoms compared to usual care or

continuation, as measured by overall withdrawal symptom scores (such as the benzodiazepine

withdrawal symptom questionnaire).

• At 12 months, there was no significant difference in problems sleeping between those who

discontinued BZRAs and those who continued using (MD 1.2, 95% CI, -0.48 to 2.88).

• In one study, the tapering group had significantly more problems sleeping at 3 months compared

to those continuing BZRAs. However, sleep did not worsen in the tapering group from baseline.

Due to the lack of evidence of substantial harm of deprescribing, and the evidence of potential harm

associated with continuing a benzodiazepine receptor agonist (particularly in the elderly), the guideline

group rated the recommendation to deprescribe BZRAs in older patients as strong. The recommendation

to deprescribe a BZRA in the younger population was rated as weak due to lower risk of adverse effects

associated with continuing BZRA use.

Deprescribing strategies/interventions for tapering down and withdrawal in adults who

are long-term users of benzodiazepines and/or Z-drugs

• The interventions evaluated in the systematic reviews with meta-analyses and studies (Gould

2014, Tannenbaum 2014, Darker 2015, Reeve 2017, Baandrup 2018, Duo 2018, Evrard 2020,

Lynch 2020, Ashworth 2021, Ribeiro 2021, Takeshima 2021) included the following:

o Brief interventions consisting mainly of written letters signed by prescribers (physician or

clinical pharmacist); short consultations by health care professionals recommending

20

education/discontinuation of the medications; telephone calls; and written educational

resources (e.g., information sheets, self-help booklets)

o Psychological interventions: structured CBT performed by trained staff including face-to-

face, telephone, computer, and virtual reality interventions; motivational interviewing;

letters to patients advising them to reduce or quit BZD use; relaxation studies; counseling

delivered electronically; and advice provided by a general practitioner

o Pharmacological interventions to assist in BZD withdrawal, including valproate,

pregabalin, captodiame, paroxetine, flumazenil, carbamazepine, pregabalin, paroxetine,

alpidem, and magnesium aspartate

o Patient education interventions to raise awareness of harms of chronic BZD use

o Interventions targeting the prescribing physician

o Multicomponent interventions

• All interventions advocated gradual BZD/BZDR dose reduction but had different specific

instructions and used different tapering schedules.

• The treatment in the control groups was not always detailed and was reported in many studies

and systematic reviews as usual treatment.

• The lack of blinding makes it difficult to determine the placebo effect associated with the

intervention.

• Many of the studies and reviews did not specify whether they included Z-drugs when referring to

benzodiazepine use. Few would include them (BZRA or BZDR).

The overall results of the published studies and meta-analysis on deprescribing BZDs show the following:

• BZD withdrawal is feasible and safe in the older population. The reported success rates for

deprescribing BZDs in older people ranged between studies and systematic reviews from 27% to

80%. The wide variation of the successful deprescribing rates may be attributed to the

heterogeneity between the studies in their methodology; participant inclusion/exclusion criteria;

definitions of elderly and chronic BZD use; dose, type, and duration of BZD used; population

characteristics, including age group, living in the community or nursing homes, comorbidities,

others; interventions used; outcomes measures, scales used for clinical outcomes, and whether

outcomes were objective, collected from records, physician-reported, or self-reported.

• Moderate-strength evidence shows that psychotherapy (mainly cognitive behavioral therapy

[CBT]) is an effective approach for benzodiazepine discontinuation.

o An earlier meta-analysis of RCTs in older patients (Gould 2014) found that supervised

withdrawal with psychotherapy was more effective than other withdrawal interventions in

older people (mean ≥ 60 years) for 12 months follow-up.

o There is evidence on the benefits of standardized counseling and psychotherapy

(compared to usual care) in deprescribing BZD. However, the duration of the

effectiveness of CBT on discontinuation of BZD varied between studies and meta-

analyses:

Takeshima (2021) meta-analysis showed that CBT is effective in discontinuing

BZD anxiolytics for patients with anxiety disorders up to 12 months of follow-up.

An earlier Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis (Darker 2015) found

that CBT plus taper is effective for 3-month time period in reducing BZD use, but

is not sustained at or beyond 6 months.

• Moderate-strength evidence shows benefit of patient education in deprescribing BZDs. Direct

consumer education of older adults and the discussions with their physician and/or pharmacist on

the harms of benzodiazepine use were effective in improving the benzodiazepine discontinuation

(NNT=4 in the EMPOWER study [Tannenbaum 2014]).

• A recent meta-analysis (Lynch 2020) showed that the rate of discontinuation of BZRA use was

significantly higher at 6 and 12 months among patients who received a brief intervention delivered

in primary care compared to those receiving usual care.

• There is insufficient evidence to support the use of motivational interviewing in reducing BZD use.

• The evidence on the benefits and harms of using pharmacological therapy to assist deprescribing

of BZDs is very low, contradictory, and insufficient to make any conclusion. While certain drugs

such as valproate and tricyclic antidepressants showed some benefit, others were found to be

harmful (e.g., Flumazenil may be associated with a high risk of precipitating a severe withdrawal

21

syndrome; Alpidem may worsen both the probability of discontinuing benzodiazepines and the

intensity of withdrawal symptoms [Baandrup 2018)]).

• There is insufficient published evidence on the effectiveness of targeting primary care physicians

on deprescribing BZDs. The BENZORED cluster RCT (Vicens 2019) is underway and may

provide evidence on the effect of an intervention targeting primary care providers to reduce BZD

prescription and evaluate the implementation process.

Factors predicting the success or failure of tapering and/or discontinuing the use of

benzodiazepines or Z-drugs in adults on long-term use (i.e., enablers and barriers for

deprescribing BZD/BZDR)

The overall barriers and enablers reported in the literature (systematic review [Rasmussen 2021],

commentary [Ogbonna 2017], and multivariable analysis in the study arm of COME-ON study [Evrard

2020, Anrys 2016]) may be related to patients and/or providers and can be summarized as follows:

1. Patient-related barriers and enablers for deprescribing BZD

Barriers

• Dependence on BZD to cope with everyday life and/or for a physical or psychological

underlying condition

• Psychological factors and existing personality traits

• Comorbid dementia or Parkinson’s disease and a history of hospitalization in the past 3 months

• Fear of a return of the insomnia or anxiety

• History of alcohol or drug use

• Lack of family or social support

• Older age

• Lack or inadequate awareness of harms and side effects of BZRA treatment, and lack of

knowledge of other treatment options

• Generalized frustration towards the medical profession and disappointment about their

treatment, mainly due to limited consultation in decision-making. Some patients described their

prescriber as adopting “a one size fits all approach.”

• Perceived issues with prescribers’ tendency to overprescribe and their lack of sufficient

knowledge about BZDs

• Unsympathetic primary care physicians providing insufficient support

• Inability to talk openly about their BZDs and feeling stigmatized by their prescribers, who show

little effort to understand them. Some interpreted the prescriber attitude as being dismissive or

even punitive.

Enablers

• The patient’s willingness to stop BZRA treatment and return to natural sleep

• Knowing the harms associated with long-term use and experiencing impairing side effects

• Recognizing the need to change their beliefs and attitude towards their medication

• Knowledge about other effective strategies to address underlying issues

• Voicing their opinion and being actively involving in decision-making

• Receiving the prescription from their personal primary care provider versus another provider or

prescriber

• Patient’s trust of the provider. The most significant influences on trust were the prescriber

having a genuine desire to understand the patient, being knowledgeable about BZDs, open

communication, shared decision-making, and, to a lesser degree, duration of the relationship.

2. Physician- and/or prescriber-related barriers and enablers for deprescribing BZD

Barriers

• Lack of knowledge about BZDs and lack of monitoring

• Expected patient resistance towards deprescribing of BZRA

• Reluctance to deprescribe treatment from functioning patients

• Conception that BZRA does not harm

• Concern about withdrawal symptoms

22

• General attitude that BZRA should not be avoided, and continued use is necessary

• Unequal balance of power between nurses and physicians

Enablers

• Engaging patients in motivational interviewing before beginning the deprescribing process and

giving them time to consider the benefits

• The physician’s knowledge of and willingness to follow the guidelines’ instructions that BZRA

use is only for the short term

• Physician empathy, demonstrated compassion, and encouragement during tapering

• Satisfactory knowledge about BZDs, diligence in monitoring their use, and providing regular

suggestions and encouragement

• Actively involving the patient in shared decision-making

• Flexibility, collaboration with other healthcare providers, and involving nurses in the patients´

medications and evaluation.

Predictors of continued abstinence after a successful tapering and withdrawal

intervention in adults who are long-term users of benzodiazepines or Z-drugs

There is insufficient published evidence to determine the predictors of long-term success of deprescribing

BZDR.

Low-strength evidence from one earlier small RCT conducted in the Netherlands (Voshaar 2006)

suggests that only one-third of low-dosage benzodiazepine users in the population achieved long-term

abstinence with the aid of a supervised gradual withdrawal program.

The analyses of the study suggest five independent predictors associated with a successful long-term

continued abstinence. These include:

• Low benzodiazepine dosage before the start of tapering off

• Less severe benzodiazepine dependence

• No use of alcohol

• Active treatment versus no intervention

• Dosage reduction of more than 50% after the minimal intervention

References

Anrys P, Strauven G, Boland B, et al. Collaborative approach to Optimise MEdication use for Older people in Nursing

homes (COME-ON): study protocol of a cluster controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2016;11:35. Published 2016 Mar 11.

doi:10.1186/s13012-016-0394-6

Ashworth N, Kain N, Wiebe D, Hernandez-Ceron N, Jess E, Mazurek K. Reducing prescribing of benzodiazepines in

older adults: a comparison of four physician-focused interventions by a medical regulatory authority. BMC Fam Pract.

2021;22(1):68. Published 2021 Apr 8. doi:10.1186/s12875-021-01415-x

Baandrup L, Ebdrup BH, Rasmussen JØ, Lindschou J, Gluud C, Glenthøj BY. Pharmacological interventions for

benzodiazepine discontinuation in chronic benzodiazepine users. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2018;3(3):CD011481. Published 2018 Mar 15. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011481.pub2

Baek YH, Lee H, Kim WJ, et al. Uncertain Association Between Benzodiazepine Use and the Risk of Dementia: A

Cohort Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(2):201-211.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.017

Bandelow B, Reitt M, Röver C, Michaelis S, Görlich Y, Wedekind D. Efficacy of treatments for anxiety disorders: a

meta-analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30(4):183-192. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000078

Bandelow B, Werner AM, Kopp I, Rudolf S, Wiltink J, Beutel ME. The German Guidelines for the treatment of anxiety

disorders: first revision [published online ahead of print, 2021 Oct 5]. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;1-12.

doi:10.1007/s00406-021-01324-1

23

Bentley KH, Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Kleiman EM, Fox KR, Nock MK. Anxiety and its disorders as risk factors for

suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:30-46.

doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.008

Boggs JM, Lindrooth RC, Battaglia C, et al. Association between suicide death and concordance with benzodiazepine

treatment guidelines for anxiety and sleep disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;62:21-27.

doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.11.005

Cato V, Holländare F, Nordenskjöld A, Sellin T. Association between benzodiazepines and suicide risk: a matched

case-control study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):317. Published 2019 Oct 26. doi:10.1186/s12888-019-2312-3

Conn DK, Hogan DB, Amdam L, et al. Canadian Guidelines on Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonist Use Disorder

Among Older Adults. Can Geriatr J. 2020;23(1):116-122. Published 2020 Mar 30. doi:10.5770/cgj.23.419

Croke L. Deprescribing Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists for Insomnia in Adults. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(1):57-

58.

Darker CD, Sweeney BP, Barry JM, Farrell MF, Donnelly-Swift E. Psychosocial interventions for benzodiazepine

harmful use, abuse or dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(5):CD009652.

doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009652.pub2

Drapeau CW, Nadorff MR. Suicidality in sleep disorders: prevalence, impact, and management strategies. Nat Sci

Sleep. 2017;9:213-226. Published 2017 Sep 14. doi:10.2147/NSS.S125597

Du Y, Du B, Diao Y, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants and benzodiazepines for the

treatment of panic disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;60:102664.

doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102664

Evrard P, Henrard S, Foulon V, Spinewine A. Benzodiazepine Use and Deprescribing in Belgian Nursing Homes:

Results from the COME-ON Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(12):2768-2777. doi:10.1111/jgs.16751

Gerlach LB, Maust DT, Leong SH, Mavandadi S, Oslin DW. Factors Associated With Long-term Benzodiazepine Use

Among Older Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1560-1562. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2413

Gomez AF, Barthel AL, Hofmann SG. Comparing the efficacy of benzodiazepines and serotonergic anti-depressants

for adults with generalized anxiety disorder: a meta-analytic review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19(8):883-894.

doi:10.1080/14656566.2018.1472767

Gould RL, Coulson MC, Patel N, Highton-Williamson E, Howard RJ. Interventions for reducing benzodiazepine use in

older people: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [published correction appears in Br J Psychiatry. 2014

Oct;205(4):330]. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(2):98-107.

Hafdi M, Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Beishuizen CRL, Moll van Charante EP, Richard E, van Gool WA. Association of

Benzodiazepine and Anticholinergic Drug Usage With Incident Dementia: A Prospective Cohort Study of Community-

Dwelling Older Adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(2):188-193.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2019.05.010

Lucchetta RC, da Mata BPM, Mastroianni PC. Association between Development of Dementia and Use of

Benzodiazepines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38(10):1010-1020.

doi:10.1002/phar.2170

Lynch T, Ryan C, Hughes CM, et al. Brief interventions targeting long-term benzodiazepine and Z-drug use in primary

care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2020;115(9):1618-1639. doi:10.1111/add.14981

Marks IM, Swinson RP, Başoğlu M, et al. Alprazolam and exposure alone and combined in panic disorder with

agoraphobia. A controlled study in London and Toronto. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:776-787.

doi:10.1192/bjp.162.6.776

Nafti M, Sirois C, Kröger E, Carmichael PH, Laurin D. Is Benzodiazepine Use Associated With the Risk of Dementia

and Cognitive Impairment-Not Dementia in Older Persons? The Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Ann

Pharmacother. 2020;54(3):219-225. doi:10.1177/1060028019882037

NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Anxiety Disorders. Quality standard (QS53). Published 6

February 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs53/chapter/quality-statement-3-pharmacological-treatment.

Ogbonna CI, Lembke A. Tapering Patients Off of Benzodiazepines. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(9):606-610.

24

Osler M, Jørgensen MB. Associations of Benzodiazepines, Z-Drugs, and Other Anxiolytics With Subsequent

Dementia in Patients With Affective Disorders: A Nationwide Cohort and Nested Case-Control Study. Am J

Psychiatry. 2020;177(6):497-505. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19030315

Parsaik AK, Mascarenhas SS, Khosh-Chashm D, et al. Mortality associated with anxiolytic and hypnotic drugs-A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(6):520-533. doi:10.1177/0004867415616695

Patorno E, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Lee MP, Huybrechts KF. Benzodiazepines and risk of all cause mortality in adults:

cohort study. BMJ. 2017;358:j2941. Published 2017 Jul 6. doi:10.1136/bmj.j2941

Penninkilampi R, Eslick GD. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Risk of Dementia Associated with

Benzodiazepine Use, After Controlling for Protopathic Bias. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(6):485-497. doi:10.1007/s40263-

018-0535-3

Poly TN, Islam MM, Yang HC, Li YJ. Association between benzodiazepines use and risk of hip fracture in the elderly

people: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Joint Bone Spine. 2020;87(3):241-249.

doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2019.11.003

Pottie K, Thompson W, Davies S, et al. Deprescribing benzodiazepine receptor agonists: Evidence-based clinical

practice guideline. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(5):339-351.

Quagliato LA, Cosci F, Shader RI, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and benzodiazepines in panic

disorder: A meta-analysis of common side effects in acute treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(11):1340-1351.

doi:10.1177/0269881119859372

Rasmussen AF, Poulsen SS, Oldenburg LIK, Vermehren C. The Barriers and Facilitators of Different Stakeholders

When Deprescribing Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists in Older Patients-A Systematic Review. Metabolites.

2021;11(4):254. Published 2021 Apr 20. doi:10.3390/metabo11040254

Reeve E, Ong M, Wu A, Jansen J, Petrovic M, Gnjidic D. A systematic review of interventions to deprescribe

benzodiazepines and other hypnotics among older people. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(8):927-935.

doi:10.1007/s00228-017-2257-8

Ribeiro PRS, Schlindwein AD. Benzodiazepine deprescription strategies in chronic users: a systematic review. Fam

Pract. 2021;38(5):684-693. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmab017

Shinfuku M, Kishimoto T, Uchida H, Suzuki T, Mimura M, Kikuchi T. Effectiveness and safety of long-term

benzodiazepine use in anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol.

2019;34(5):211-221. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000276

Taipale H, Särkilä H, Tanskanen A, et al. Incidence of and Characteristics Associated With Long-term

Benzodiazepine Use in Finland. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2019029. Published 2020 Oct 1.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19029

Takano A, Ono S, Yamana H, et al. Factors associated with long-term prescription of benzodiazepine: a retrospective

cohort study using a health insurance database in Japan. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e029641. Published 2019 Jul 26.

doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029641

Takeshima M, Otsubo T, Funada D, et al. Does cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders assist the

discontinuation of benzodiazepines among patients with anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta-

analysis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;75(4):119-127. doi:10.1111/pcn.13195