DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

01-0304 (10/01)

Copyright Information

Permission has been obtained from the

copyright holders to reproduce certain

quoted material in this report. Further

reproduction of this material is

prohibited without specific permission

of the copyright holder. All other

material contained in this report is in the

public domain and may be used and

reprinted without special permission;

citation as to source, however, is

appreciated.

Suggested Citation

National Center for Health Statistics.

Healthy People 2000 Final Review.

Hyattsville, Maryland: Public Health

Service. 2001.

Library of Congress Catalog Card

Number 76–641496

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Health Statistics

Hyattsville, Maryland

October 2001

DHHS Publication No. 01-0256

Department of Health and Human Services

Tommy G. Thompson

Secretary

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Jeffrey P. Koplan, M.D., M.P.H.

Director

National Center for Health Statistics

Edward J. Sondik, Ph.D.

Director

Preface

The Healthy People 2000 Final

Review is the seventh and last in a

series of profiles tracking the year 2000

objectives. This report was compiled by

the National Center for Health Statistics,

Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC), with considerable

input from the Department of Health

and Human Service’s lead agencies for

the year 2000 objectives, the Office of

Disease Prevention and Health

Promotion and the Office on Minority

Health. The Healthy People 2000

Steering Committee and the National

Committee on Vital and Health Statistics

served in a review capacity.

The Healthy People 2000 Review,

which replaced the Prevention Profiles

that monitored the 1990 national health

objectives, continued the series of

profiles of the Nation’s health objectives

as an integral part of the Department’s

disease prevention and health promotion

initiative for the year 2000. This

initiative was unveiled in September

1990 by the Secretary of the Department

of Health and Human Services with the

release of Healthy People 2000:

National Health Promotion and Disease

Prevention Objectives. This publication,

which incorporates the 1995 midcourse

review modifications to the objectives,

provides the latest available tracking

data for objectives and subobjectives in

all priority areas throughout the decade.

iii

Foreword

Since 1990, Healthy People 2000

has provided the national health

promotion agenda that guided

Americans toward living longer and

healthier lives. Healthy People 2000 not

only identified objectives to improve the

Nation’s health, but also set measurable

targets to monitor progress toward its

goals. The ability to quantify and assess

progress on health objectives is at the

heart of the Healthy People initiative.

This Healthy People 2000 Final Review

completes the series of Healthy People

2000 Reviews published to monitor and

evaluate the Nation’s progress toward

the year 2000 targets. As such, it

presents the final assessments of our

progress in the decade.

Healthy People 2000 was an

ambitious effort and invaluable in

setting 319 specific objectives for the

Nation. In fact, progress was achieved

on over 60 percent of the objectives.

Some of the major accomplishments

include surpassing the target for

reducing deaths from coronary heart

disease and cancer. The Nation also met

its targets for AIDS incidence, primary

and secondary syphilis cases,

mammography exams, and violent

(homicide, suicide, and firearm-related)

deaths. The tobacco-related mortality

targets were also met. Both infant

mortality and the number of children

with elevated blood lead levels nearly

met their targets as well. The Nation

also made progress toward the goal of

reducing health disparities for more than

one-half of the special population

objectives identified to be at increased

risk by Healthy People 2000. We can all

take pride in the fact that the past

decade saw substantial improvements in

the quality of life for many Americans.

Underlying and contributing to the

progress in preventing disease and

improving health are the advances in

health information. Healthy People 2000

was a catalyst at all levels of

government for the creation and

dissemination of quality, comparable

health data.

This final edition of the Healthy

People 2000 Review contains several

new data assessments that should prove

valuable for many of our constituents.

The first is an assessment of the

progress toward the second goal of

Healthy People 2000, reducing health

disparities. The assessment is based on

data collected for nine special

populations that are at increased health

risk: four race/ethnicity groups, women,

two age groupings, disability, and

socioeconomic status. Another is the

presentation of data for the 47 ‘‘sentinel

objectives’’ developed to represent the

scope and magnitude of Healthy People

2000. This includes data for each

sentinel objective at the national level

and State data for those objectives

where sources were available. Finally, in

addition to data that update the trends

shown in previous reports for the 18

Health Status Indicators, this report

shows data for the first time for the 16

Priority Data Needs developed at the

same time as the Health Status

Indicators but which lacked data for

assessment below the national level.

Although many gains in health

promotion and disease prevention have

been made, much remains to be done.

For 15 percent of the Healthy People

2000 objectives, the movement was

actually away from the targets. In

January 2000, Healthy People 2010 was

released, ushering the Healthy People

initiative into the new millennium. The

monitoring and assessment goals of

Healthy People 2010 are even more

ambitious than those that have directed

our efforts over the past decade. For

example, the Healthy People 2000 goal

to reduce health disparities has been

strengthened in Healthy People 2010 to

focus on eliminating health disparities.

Another important development for

the next decade is the publication

Tracking Healthy People 2010.Asa

guidebook on the statistics used for

Healthy People, it will assist programs

at the local, State, and national levels in

producing and using the requisite data

and, thereby, measurably advance the

information base available to enhance

the public’s health. Thanks to the solid

foundation laid by the accomplishments

of Healthy People 2000, Healthy People

2010 will be even stronger, as it builds

on the experiences of the last decade,

identifies our current health

opportunities and challenges, and

furthers the development of partnerships

among public and private organizations

to improve the health of the American

people.

Edward J. Sondik, Ph.D. Director,

National Center for Health Statistics

iv

Acknowledgments

Overall responsibility for planning

and coordinating the content of the

Healthy People 2000 Final Review

rested with the Division of Health

Promotion Statistics (DHPS), Office of

Analysis, Epidemiology, and Health

Promotion (OAEHP), National Center

for Health Statistics (NCHS), under the

general direction of Diane K. Wagener

and Richard J. Klein.

Production coordination was shared

among DHPS analysts: John

Aberle-Grasse, Elizabeth W. Jackson,

Colleen M. Ryan, and Kathleen M.

Turczyn.

Production was accomplished by

several DHPS working teams, which

included John Aberle-Grasse, Manon

Boudreault, Lillie Featherstone, Tracy

Fenwick, Elizabeth W. Jackson, Kenneth

Keppel, Insun Kim, Richard J. Klein,

Michael Molla, Jeffrey N. Pearcy,

Suzanne E. Proctor, Cheryl V. Willis,

Colleen M. Ryan, Thomas C. Socey,

Kathleen M. Turczyn, Diane K.

Wagener, and Jean F. Williams.

The sections discussing the Healthy

People 2000 goals were developed with

substantial input by the Office of

Minority Health (OMH)—particularly

Olivia D. Carter-Pokras and Tuei

Doong, the Office of Disease Prevention

and Health Promotion (ODPHP)—

particularly Omar Passons, the Agency

for Healthcare Research and Quality

(AHRQ), and the Health Resources and

Services Administration (HRSA)—

particularly David Atkins, Melissa

Clarke, Paul Nannis, Kathryn Rickard,

and Lyman Van Nostrand.

The priority area chapters were

coordinated by DHPS analysts and

written by working teams as follows:

Priority Area 1: Carol Macera

(CDC) and Christine Spain (OPHS)

Priority Area 2: Carter Blakely

(ODPHP), Nancy T. Crane (FDA), and

Pamela E Starke-Reed (NIH)

Priority Area 3: Karil Bialostosky

(CDC)

Priority Area 4: James Colliver

(NIH), Wendy Davis (SAMHSA), Susan

Farrell (NIH), Ann Mahony (SAMSHA),

Beatrice Rouse (SAMSHA), and Dorita

Sewell (SAMHSA)

Priority Area 5: Evelyn Kappeler

(OPHS)

Priority Area 6: Michele Edwards

(SAMHSA), Doreen Koretz (NIMH),

Ann Maney (NIMH), and Dorita Sewell

(SAMHSA)

Priority Area 7: Mark Anderson

(CDC), Lee Annest (CDC), Alex Crosby

(CDC), Martha Highsmith (CDC), Tom

Simon (CDC), and Tim Thornton (CDC)

Priority Area 8: Melissa Clarke

(HRSA), Catherine Hutsell (CDC), and

Brick Lancaster (CDC)

Priority Area 9: Tim Groza (CDC)

Priority Area 10: Bob Castellan

(CDC), Dawn Castillo (CDC), Regina

Pana-Cryan (CDC), Bill Eschenbacher

(CDC), John Franks (CDC), Joe Hurrell

(CDC), Lynn Jenkins (CDC), Jay Jones

(CDC), Boris Lushniak (CDC), Mark

Mendell (CDC), Bob Roscoe (CDC),

Lee Sanderson (CDC), John Sestito

(CDC), and Rosie Sokas (CDC)

Priority Area 11: David Evans

(ATSDR), Paul Garbe (CDC), and John

Schelp (NIH)

Priority Area 12: Linda S. Brophy

(FDA) and Elisa Elliot (FDA)

Priority Area 13: Alice M. Horowitz

(NIH), Candace M. Jones (HRSA), and

Stuart Lockwood (CDC)

Priority Area 14: Charlotte

Dickinson (CDC), Renee Schwalberg

(CDC), Myra Tucker (CDC), and Stella

M. Yu (HRSA)

Priority Area 15: Matilde Alvarado

(NIH), James Cleeman (NIH), Janet B.

Croft (CDC), Karen Donato (NIH),

Robinson Fulwood (NIH), Wayne H.

Giles (CDC), Kurt Greenlund (CDC),

Jeanette Guyton-Krishnan (NIH), Mary

M. Hand (NIH), Greg Heath (CDC),

Keith Hewitt (NIH), Darwin Labarthe

(CDC), Terry Long (NIH), George A.

Mensah (CDC), Greg Morosco (NIH),

Linda Redman (CDC), Edward J.

Roccella (NIH), Nancy Watkins (CDC),

and Zhi-Jie Zheng (CDC)

Priority Area 16: Barry Portnoy

(NIH) and Karen Richard (CDC)

Priority Area 17: Stephanie

Benjamin (CDC), Ben Burton (NIH),

Bill Foster (NIH), Linda Geiss (CDC),

Ed Tierney (CDC), and Frank Vinicor

(CDC)

Priority Area 18: Dave Brownell

(CDC), Brenda Garza (CDC), Shelley

Gordon (HRSA), Stacie Greby (CDC),

Gena Hill (CDC), Joyce Neal (CDC),

Ida Onorato (CDC), and Eva Seiler

(CDC)

Priority Area 19: Susan C. Clark

(CDC), Melinda Flock (CDC), Joel R.

Greenspan (CDC), Dana M. Shelton

(CDC), and Jack N. Spencer (CDC)

Priority Area 20: Jennifer Brooks

(CDC), Sarah Foster (CDC), John

Seggerson (CDC), and Nicole Smith

(CDC)

Priority Area 21: David Atkins

(AHRQ), Melissa Clarke (HRSA), Paul

Nannis (HRSA), Kathryn Rickard

(AHRQ), and Lyman Van Nostrand

(HRSA)

Priority Area 22: Diane Wagener

(CDC)

Technical review was provided by

Jennifer Madans, NCHS Associate

Director for Science. Publications

management and editorial review were

provided by Gail V. Johnson and

Rolfe W. Larson. The designer was

Sarah M. Hinkle. Graphics were

produced by Dorothy Day and

supervised by Stephen L. Sloan.

Production was done by Annette F.

Holman. Electronic publishing was done

by Annette F. Holman, Christine Brown,

and Margaret Avery. Printing was

managed by Patty L Wilson and

Joan Burton.

Publication of Healthy People 2000

Final Review would not have been

possible without the contributions of

many staff members throughout NCHS

and numerous other agencies,

particularly Carter Blakey, Office of

Disease Prevention and Health

Promotion. These people gave

generously of their time and knowledge;

their cooperation and assistance are

gratefully acknowledged.

NOTE: Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC), Office of Public Health Service

(OPHS), Office of Disease Prevention and Health

Promotion (ODPHP), Food and Drug

Administration (FDA), National Institute of Health

(NIH), Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration (SAMHSA), National

Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Health

Resources and Services Administration (HRSA),

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

(ATSDR), Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality (AHRQ).

v

Contents

Preface iii

Foreword

iv

Acknowledgments v

List of Figures

ix

List of Tables

xi

Introduction 1

Background

1

Summary of Progress 2

Organization and Scope of this Review

4

Healthy People 2000 Goals

7

Goal 1: Increase the Span of Healthy Life 7

Life Expectancy at Birth

7

Fair or Poor Health 7

Healthy and Unhealthy Life

7

Goal 2: Reducing Health Disparities 8

Reducing Disparities: American Indian/Alaska Native

9

Reducing Disparities: Asian or Pacific Islander

10

Reducing Disparities: Black or African American 10

Reducing Disparities: Hispanic or Latino 10

Reducing Disparities: Women

10

Reducing Disparities: Adolescents and Young Adults 10

Reducing Disparities: Older Adults

11

Reducing Disparities: People with Disabilities

11

Reducing Disparities: People with Low Socioeconomic Status 11

Goal 3: Achieving Access to Preventive Services

11

Health Status Indicators and Priority Data Needs 19

Health Status Indicators

19

Priority Data Needs 19

Sentinel Objectives

27

National Data

27

State Data 30

Healthy People 2000 Priority Areas

1. Physical Activity and Fitness

65

2. Nutrition 76

3. Tobacco

93

4. Substance Abuse: Alcohol and Other Drugs 108

5. Family Planning 117

6. Mental Health and Mental Disorders

127

7. Violent and Abusive Behavior

137

8. Educational and Community-Based Programs 146

9. Unintentional Injuries

155

10. Occupational Safety and Health 167

11. Environmental Health

176

12. Food and Drug Safety 187

13. Oral Health

195

14. Maternal and Infant Health 206

15. Heart Disease and Stroke

217

16. Cancer

228

17. Diabetes and Chronic Disabling Conditions 238

18. HIV Infection

254

19. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 267

20. Immunization and Infectious Diseases

279

21. Clinical Preventive Services 294

22. Surveillance and Data Systems

305

Appendix 315

vii

List of Figures

A. Healthy People 2000 objectives: Summary of progress by priority area 3

B. Life expectancy at birth: United States, 1988–98

8

C. Percent of people with fair or poor health: United States, 1990–98 9

D. Expected years of healthy and unhealthy life: United States, 1998

10

E. Assessment of disparity for American Indian/Alaska Native objectives 11

F. Assessment of disparity for Asian or Pacific Islander objectives

11

G. Assessment of disparity for black or African American objectives 12

H. Assessment of disparity for Hispanic or Latino objectives

12

J. Assessment of disparity for women objectives 13

K. Assessment of disparity for adolescents and young adults objectives

13

L. Assessment of disparity for older adults objectives 14

M. Assessment of disparity for people with disabilities objectives

14

N. Assessment of disparity for people with low socioeconomic status objectives

15

O. Access to care: United States, 1988–99 15

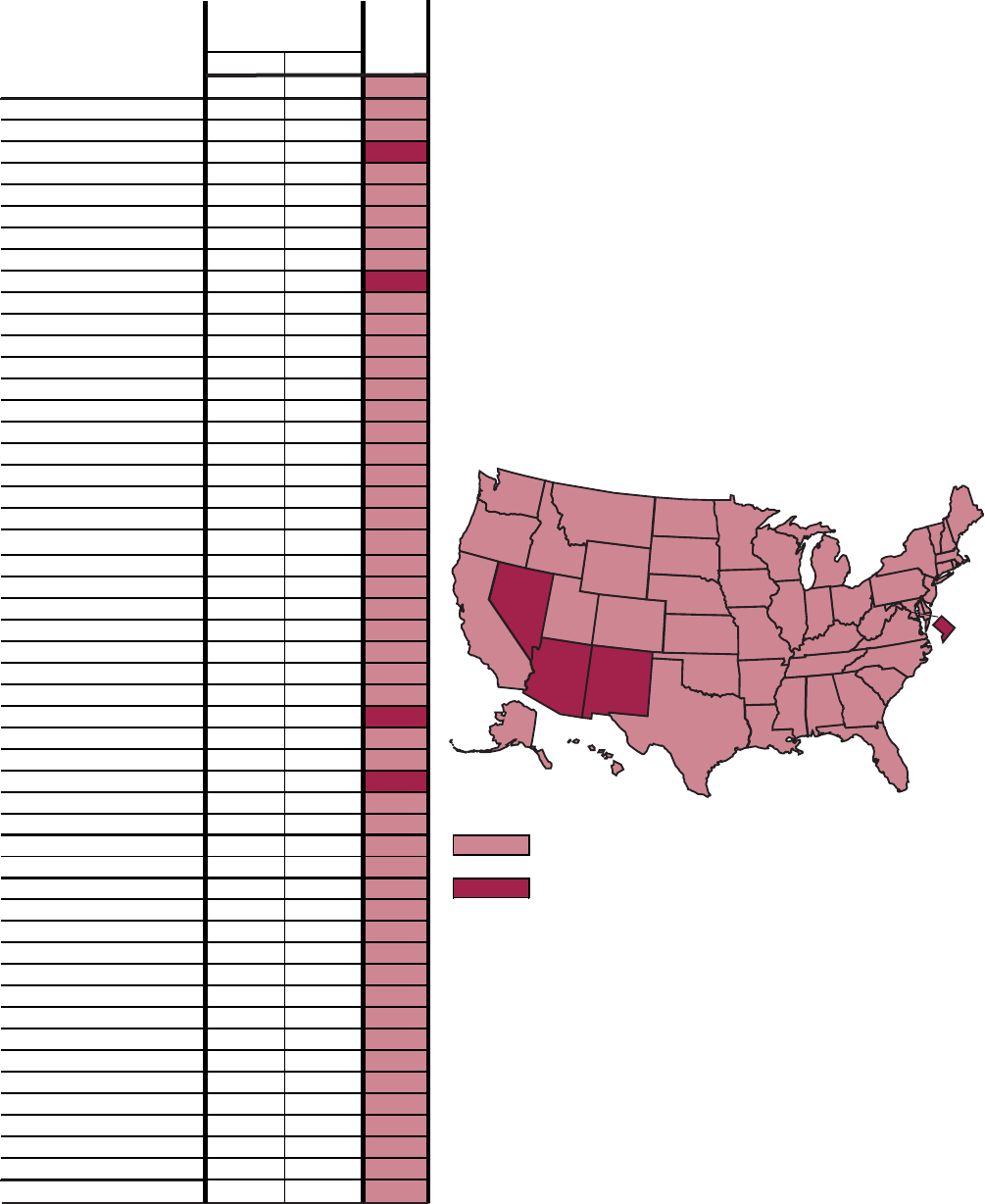

P. Percent of people under 65 years without health insurance coverage: United States, 1998 16

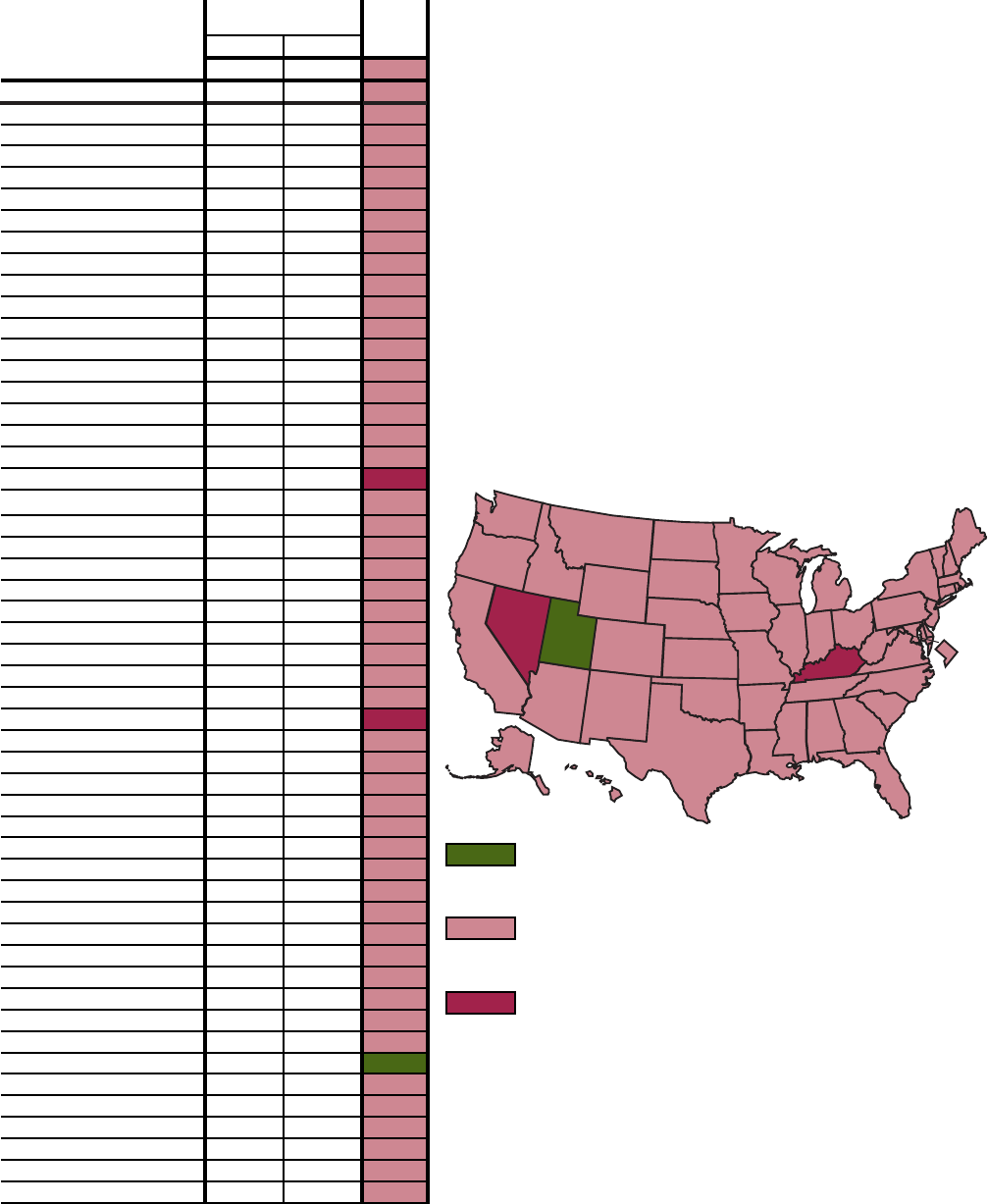

Q. Objective 1.3–Percent of adults who participated in regular physical activity (5 or more times per week):

United States and each State, 1996 and 1998

32

R. Objective 1.5–Percent of adults who reported no leisure-time physical activity: United States and each State, 1996

and 1998

33

S. Objective 2.3–Percent of persons 18 years and older who were overweight: United States and each State, 1998

and 1999

34

T. Objective 3.4–Percent of persons 18 years and older who reported current cigarette smoking: United States and each

State, 1998 and 1999 35

U. Objective 4.1–Alcohol-related motor vehicle crash deaths per 100,000 population: United States and each State,

1997 and 1998

36

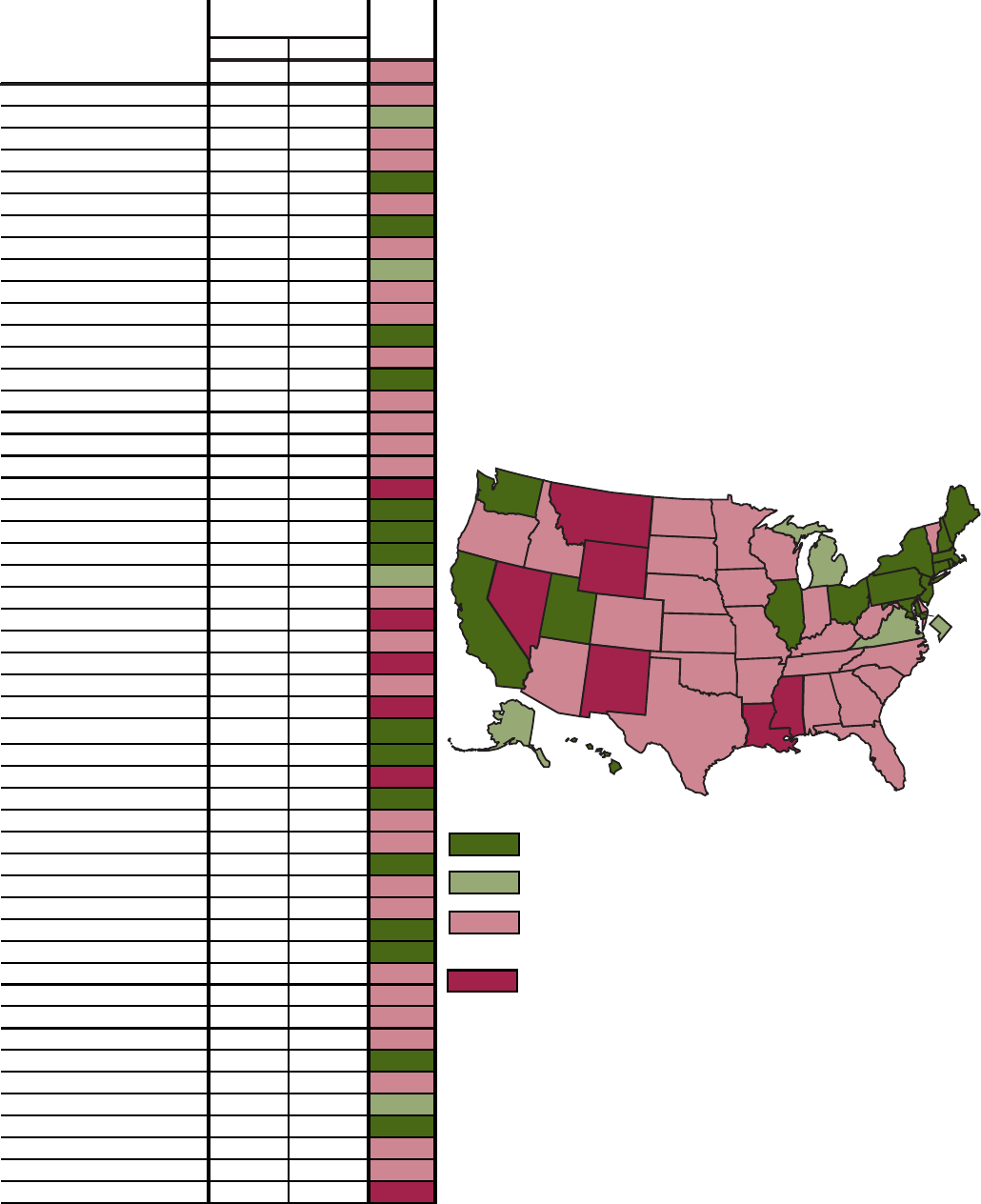

W. Objective 4.6–Percent of youth who currently use marijuana: United States and each State, 1999 37

Y. Objective 4.6–Percent of youth who currently smoke cigarettes: United States and each State, 1999

38

Z. Objective 5.1–Live birth rates for females 15–17 years old: United States and each State, 1997 39

AA. Objective 6.1–Age-adjusted death rates for suicide: United States and each State, 1997 and 1998

40

BB. Objective 7.1–Age-adjusted death rates for homicide: United States and each State, 1997 and 1998 41

CC. Objective 9.1–Age-adjusted death rates for unintentional injuries: United States and each State, 1997 and 1998

42

DD. Objective 9.12–Percent of persons wearing a safety belt while driving or riding in a car: United States and each

State, 1995 and 1997

43

EE. Objective 10.1–Work-related injury death rates: United States and each State, 1998 and 1999 44

FF. Objective 10.2–Nonfatal work-related injuries per 100 full-time workers in private industry: United States and

reporting States, 1997 and 1998

45

GG. Objective 11.5–Percent of persons in counties that have not exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

standards for air quality: United States and each State, 1997 and 1998

46

HH. Objective 14.1–Infant mortality rates: United States and each State, 1997 and 1998

47

JJ. Objective 14.5–Percent of live births of low birthweight: United States and each State, 1997 and 1998 48

KK. Objective 14.11–Percent of mothers who began prenatal care in the first trimester: United States and each State,

1997 and 1998

49

LL. Objective 15.1–Age-adjusted death rates for coronary heart disease: United States and each State, 1997 and 1998

50

MM. Objective 15.2–Age-adjusted death rates for stroke: United States and each State, 1997 and 1998 51

NN. Objective 16.1–Age-adjusted death rates for all cancers: United States and each State, 1997 and 1998

52

OO. Objective 16.11–Percent of women 50 years of age and older who received a mammogram and breast exam within

the last 2 years: United States and each State, 1998 and 1999

53

PP. Objective 16.12–Percent of women 18 years of age and older who had a Pap test during the last 3 years:

United States and each State, 1998 and 1999

54

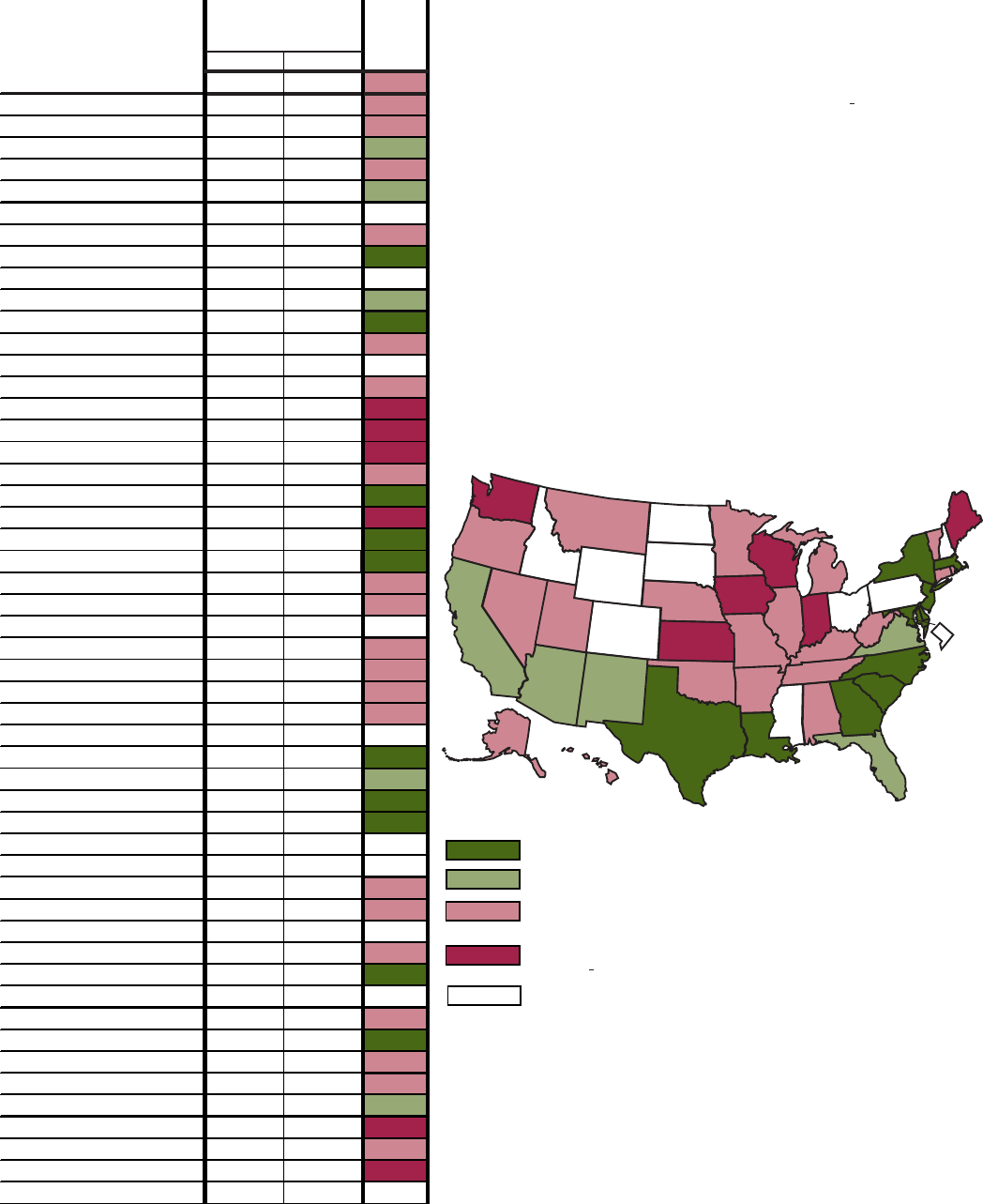

QQ. Objective 16.13–Percent of persons 50 years of age and older who have had a fecal occult blood test during the last

2 years: United States and each State, 1997 and 1999

55

RR. Objective 16.13–Percent of persons 50 years of age and older who have ever had a sigmoidoscopy or proctoscopic

exam: United States and each State, 1997 and 1999

56

SS. Objective 17.9–Age-adjusted death rates for diabetes-related deaths: United States and each State, 1997 and 1998

57

TT. Objective 19.1–Reported incidence of gonorrhea per 100,000 population: United States and each State, 1998 and

1999

58

UU. Objective 19.3–Reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis per 100,000 population: United States and each

State, 1998 and 1999

59

WW. Objective 20.1–Reported cases of measles: United States and each State, 1998 and 1999 60

viii

YY. Objective 20.11–Estimated vaccination coverage with the 4DTP/3polio/1MMR series among children ages

19–35 months: United States and each State, 1998 and 1999

61

ZZ. Objective 21.4–Percent of persons under 65 years of age with no health insurance coverage: United States and each

State, 1998 and 1999

62

Priority Area Progress Figures

1. Final status of Physical Activity and Fitness objectives 66

2. Final status of Nutrition objectives

77

3. Final status of Tobacco objectives 94

4. Final status of Substance Abuse: Alcohol and Other Drugs objectives 109

5. Final status of Family Planning objectives

118

6. Final status of Mental Health and Mental Disorders objectives 128

7. Final status of Violent and Abusive Behavior objectives

138

8. Final status of Educational and Community-Based Programs objectives

150

9. Final status of Unintentional Injuries objectives 156

10. Final status of Occupational Safety and Health objectives 168

11. Final status of Environmental Health objectives

177

12. Final status of Food and Drug Safety objectives 188

13. Final status of Oral Health objectives

196

14. Final status of Maternal and Infant Health objectives

207

15. Final status of Heart Disease and Stroke objectives 218

16. Final status of Cancer objectives

229

17. Final status of Diabetes and Chronic Disabling Conditions objectives 239

18. Final status of HIV Infection objectives

255

19. Final status of Sexually Transmitted Diseases objectives 268

20. Final status of Immunization and Infectious Diseases objectives

280

21. Final status of Clinical Preventive Services objectives 295

22. Final status of Surveillance and Data Systems objectives

304

ix

List of Tables

A. Life-stage objectives: United States, 1987–98 2

B. Health Status Indicators: United States, 1996–98

20

C. Health Status Indicators by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 1998

21

D. Priority Data Needs 22

E. An Assessment of Target Attainment for the Healthy People 2000 Sentinel Health Objectives for the United States

and Individual States

28

Priority Area Summary Tables

1. Physical Activity and Fitness objectives 70

2. Nutrition objectives

83

3. Tobacco objectives

100

4. Substance Abuse: Alcohol and Other Drugs objectives 112

5. Family Planning objectives

121

6. Mental Health and Mental Disorders objectives 132

7. Violent and Abusive Behavior objectives 142

8. Educational and Community-Based Programs objectives

150

9. Unintentional Injuries objectives

160

10. Occupational Safety and Health objectives 171

11. Environmental Health objectives

181

12. Food and Drug Safety objectives 192

13. Oral Health objectives

199

14. Maternal and Infant Health objectives 211

15. Heart Disease and Stroke objectives

221

16. Cancer objectives

231

17. Diabetes and Chronic Disabling Conditions objectives 244

18. HIV Infection objectives

259

19. Sexually Transmitted Diseases objectives 272

20. Immunization and Infectious Diseases objectives 285

21. Clinical Preventive Services objectives

298

22. Surveillance and Data Systems objectives

309

x

Introduction

Background

History of the Healthy People

Initiative

The Healthy People process began

in 1979 with the release of Healthy

People: The Surgeon General’s Report

on Health Promotion and Disease

Prevention (1), which provided national

goals for reducing premature deaths and

for preserving independence for older

adults. The five primary goals of the

1979 Surgeon General’s report were to

enhance the health of the U.S.

population in five major life stages

(infants, children, adolescents and young

adults, adults, and older adults).

Different focal points were targeted for

each age group, such as low birth-

weight and birth defects for infants, and

functional independence, influenza, and

pneumonia for older adults. Fifteen

priority areas were also identified as

keys to achievement of the overall

health status goals. In 1980, Promoting

Health/Preventing Disease: Objectives

for the Nation set forth 226 targeted

measurable health objectives for the

Nation to achieve over 10 years in 15

priority areas (2). This national agenda

for health proved its merit when, from

1979 to 1990, the infant mortality rate

decreased by nearly 35 percent and the

motor vehicle fatality rate for children

fell 28 percent. Promoting

Health/Preventing Disease: Objectives

for the Nation served as a model for the

development of Healthy People 2000

(3), which subsequently provided the

starting point for Healthy People 2010

(4).

Life-Stage Objectives

The five major life stages theme has

continued through the decades as part of

the Healthy People initiative. Healthy

People 2000 included targets for

reducing deaths among people under age

65, and for reducing the proportion of

people 70 years and over who have

difficulty performing two or more

activities of daily living. Healthy People

2000 contained four age-related

objectives.

Reduce the death rate for children

by 15 percent to no more than 28 per

100,000 children 1–14 years of age, and

for infants by approximately 30 percent

to no more than 7 per 1,000 live births.

Reduce the death rate for

adolescents and young adults by

15 percent to no more than 85 per

100,000 people 15–24 years.

Reduce the death rate for adults by

20 percent to no more than 340 per

100,000 people 25–64 years of age.

Reduce to no more than 90 per

1,000 people the proportion of all

people age 70 years and over who have

difficulty in performing two or more

personal care activities (a reduction of

about 19 percent), thereby preserving

independence.

As shown in table A, data for 1998

indicate that the targets for children and

adolescents and young adults have been

met. The 1998 infant mortality rates of

7.2 per 1,000 live births was very close

to meeting the year 2000 target.

However, the rate for older adults who

had difficulty performing two or more

personal care activities (bathing, eating,

dressing, using the toilet, or getting

in/out of chair/bed) moved away from

the target during the Healthy People

2000 tracking period.

Healthy People 2000

Healthy People 2000: National

Health Promotion and Disease

Prevention Objectives presented the

Nation’s health improvement agenda for

the last decade of the 20th century (3).

Released in 1990, it articulated goals

and objectives aimed at significantly

improving the health of all Americans

by the year 2000.

In developing its own strategy to

improve the health of all Americans,

Healthy People 2000 drew on the

experiences and knowledge gained

during the earlier Healthy People

endeavors. The Healthy People 2000

process was guided by three broad

goals: (1) increase the span of healthy

life, (2) reduce health disparities, and

(3) achieve access to preventive

services. To help meet these overarching

goals, it identified more than 300

national objectives addressing a broad

array of health issues. Forty-seven of

these objectives that were representative

of the scope and magnitude of Healthy

People 2000 were identified as

‘‘sentinel’’ objectives (see Sentinel

Objectives section).

The Healthy People 2000

objectives, each assigned a specific

target, were organized into 22 priority

areas. The activities of each priority area

were coordinated by at least one agency

of the Public Health Service. Addressing

special population groups at high risk of

poor health, Healthy People 2000 set

specific targets to narrow the gap

between the total population and those

groups with higher than average rates of

death, disease, and disability. In

addition, it included priority areas such

as HIV infection and cancer that were

not included in the 1990 objectives.

Underscoring the vital role of

partnerships, Healthy People 2000 was

the product of a cooperative effort

among government agencies, businesses,

nonprofit organizations, and the

scientific community. It was developed

in collaboration with 22 work groups of

experts, agencies of the Federal

government, the National Academy of

Sciences’ Institute of Medicine, and a

consortium of over 375 members

representing national voluntary

organizations and all the State health

departments. Regional and national

meetings provided input from a broad

cross section of citizens, families, and

communities. Moreover, following

extensive public review of and comment

on a draft document, the Healthy People

2000 objectives were revised and

refined.

Midcourse Modifications

Throughout the 1990s, a series of

reports tracked the progress of the

Nation in achieving the Healthy People

2000 objectives. Halfway through the

decade, the national commitment to

disease prevention and health promotion

was reaffirmed during the midcourse

review process, which allowed for the

modification and addition of objectives.

The midcourse review was a 2-year

process, culminating in the publication

of the Healthy People 2000 Midcourse

Review and 1995 Revisions (5) in 1995.

During the midcourse review, work

groups of the Public Health Service met

to consider new data, new information,

and new science that had become

available since the release of Healthy

People 2000 in 1990 (3). As a result, 19

new objectives were added to the

original 300 unduplicated main

objectives, bringing the total number of

objectives to 319. Additional data that

showed increased health risk or disparity

between the total population and people

in age, sex, racial, or ethnic minority

groups resulted in the addition of 111

new special population subobjectives

(bringing the total number of

subobjectives to 319). Including the

Healthy People 2000 Final Review 1

midcourse changes, Healthy People

2000 contained a total of 638 objectives

and subobjectives; because some priority

areas share identical objectives, the

number of objectives and subobjectives

including duplicates is 805. No changes

were made to the three broad goals of

Healthy People 2000 or to the

organization of the 22 priority areas.

The midcourse review also included

58 target revisions (29 objectives and 29

subobjectives), in almost all cases to

make the target more challenging. Text

changes were made to 75 existing

objectives, in some cases considerably

modifying the objective. All midcourse

review modifications are detailed in

Healthy People Statistical Note No. 13

(6).

The midcourse modifications

established baselines for all Healthy

People 2000 objectives for which data

were available. Most of these baselines

are the same as those established in the

original Healthy People 2000 report (3);

others were changed to reflect revisions

to the original baselines or were newly

created.

Healthy People 2010

Healthy People 2010: Objectives for

Improving Health (4), released in

January 2000, carries the Healthy People

initiative into the next decade as well as

into a new millennium. As the third

generation of 10–year goals for the

Nation, it builds on initiatives pursued

over the past two decades. Central to

Healthy People 2010 are its two broad

goals, which challenge the Nation to (1)

increase quality and years of healthy life

and (2) eliminate health disparities.

Providing a framework to achieve

these goals, Healthy People 2010

identifies 467 specific health promotion

and disease prevention objectives in 28

focus areas. Like its predecessors,

Healthy People 2010 is the product of

an extensive cooperative national

process involving both the public and

private sectors, including the Healthy

People Consortium, which by the end of

the 20th century had grown to include

some 350 national organizations and

250 State public health, mental health,

substance abuse, and environmental

agencies.

To facilitate tracking progress

toward the second goal of Healthy

People 2010—eliminating health

disparities—objectives that utilize

population-based measures display the

baseline status of multiple population

groups. The minimum breakout set of

groups includes race and ethnicity,

gender, and measures of socioeconomic

status. However, many objectives

include additional population groups

such as age, geographic location, health

insurance status, disability status, sexual

orientation, or people with a specific

health status or condition. Of the 396

measures in Healthy People 2010 that

listed population groups, baseline data

were available for nearly three quarters

of the over 6,000 data items for the

minimum set of groups (4).

Leading Health Indicators

Setting itself apart from previous

Healthy People efforts, Healthy People

2010 introduces for the first time a set

of 10 Leading Health Indicators (LHIs).

Intended to serve as a gauge of the

Nation’s well-being, the LHIs reflect

major public health priorities in the

United States at the beginning of the

21st century. They were selected

because of their importance as public

health issues, their ability to motivate

action, and the availability of data to

measure their progress. The 10 LHIs are

physical activity, overweight and

obesity, tobacco use, substance abuse,

responsible sexual behavior, mental

health, injury and violence,

environmental quality, immunization,

and access to health care. Each LHI will

be monitored using one or more of the

467 specific objectives, thus serving as a

link to the entire Heathy People 2010

initiative.

Through the LHIs, and through the

467 objectives, Healthy People 2010

continues an impressive tradition of

improving the Nation’s health through a

comprehensive process of setting goals

and measuring results. For more

information on Healthy People 2010,

visit the Web site at

http://www.health.gov/healthypeople.

Summary of Progress

Healthy People 2000 identifies 319

unduplicated main objectives. Because

some priority areas share identical

objectives, certain objectives are

presented in more than one priority area,

which increases the total number of

objectives to 376 including the

duplicates. Subobjectives for racial and

ethnic minorities and other special

populations were established to address

increased health risks or disparities

compared with the total population.

There are 319 subobjectives; with

duplicates, there are 429 (5).

Movement of an objective either

toward or away from the target was

assessed by the direction of the change

between the baseline and the most

recent data point for the measure(s) used

to track the objective. In most cases,

only measures with baselines and targets

were used for assessment; supplemental

data (no baseline or target) were used if

Table A. Life stage objectives: United States, 1987–98

Objectives

Baseline

1987 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

2000

Target

Infant mortality (per 1,000 live births) .......... 10.1 8.9 8.5 8.4 8.0 7.6 7.3 7.2 7.2 7

Children 1–14 years (total deaths per 100,000) . . . 33.7 30.7 28.8 29.8 28.5 27.8 26.5 25.1 24.0 28

Adolescents and young adults 15–24 years (total

deaths per 100,000) ...................... 97.8 100.1 95.6 98.5 98.0 95.3 89.6 86.2 82.3 85

Adults 25–64 years (total deaths per 100,000) . . . 426.9 400.7 394.7 400.1 398.6 397.3 382.0 368.1 364.0 340

People 70 years and over (difficulty in performing

two or more personal care activities per 1,000) . .

1

141 --- --- --- ---

2

163 --- --- --- 90

- - - Data not available.

1

1984–85 data.

2

1994–95 data

SOURCES: National Vital Statistics System, CDC, NCHS.

For people 65 years and over: National Health Interview Survey, CDC, NCHS; National Nursing Home Survey, CDC, NCHS.

2 Healthy People 2000 Final Review

measures with baseline and targets were

not available. Some of the changes

observed were relatively small and may

be within what could be expected on the

basis of sampling or random variation.

For objectives with more than one

measure (compound objectives), if data

showed movement in different

directions, progress was labeled as

‘‘mixed.’’ For compound objectives with

data not available for all measures,

progress was determined by the

direction of the measure(s) with data.

For example, objective 12.3 is tracked

using three measures. However,

sufficient tracking data are only

available for two of the three measures:

Refrigeration of perishable foods and

washing cutting boards with soap.

Progress for this objective is assessed

using these two measures. All measures

of a compound objective had to be met

for an objective to be considered met;

for example, a compound objective with

three measures meeting the target and

one measure progressing toward the

target would be considered moving

toward the target (objective 1.10). A few

objectives were very broad in scope and

tracking data were not available; in

these cases, the subobjectives were used

to track progress (for example, objective

17.14).

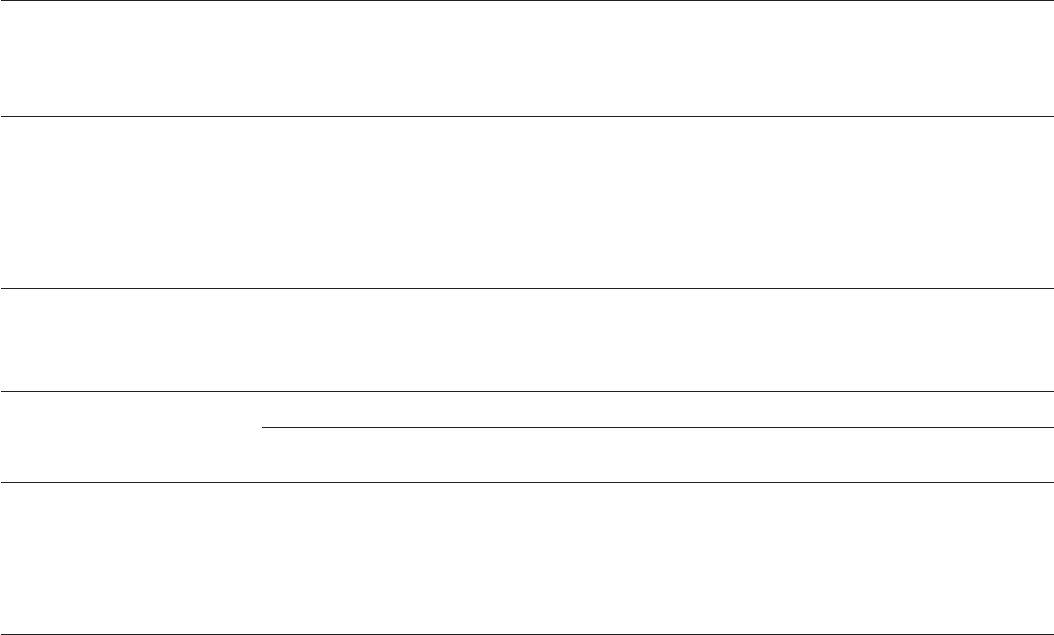

The following summary of progress,

based on the 319 unduplicated main

objectives, presents the final status for

the Healthy People 2000 objectives. The

most recent data indicate that 68

objectives (21 percent) met the year

2000 targets and an additional 129

(41 percent) showed movement toward

the targets. Data for 35 objectives

(11 percent) showed mixed results and 7

(2 percent) showed no change from the

baseline. Only 47 objectives (15 percent)

showed movement away from the

targets. The status of 32 objectives

(10 percent) could not be assessed.

Among these unassessed objectives, 23

have baseline data but no additional data

with which to evaluate progress (several

objectives in this category have

supplemental data that cannot be used

for determination of progress), and 9

objectives lacked baselines (see Priority

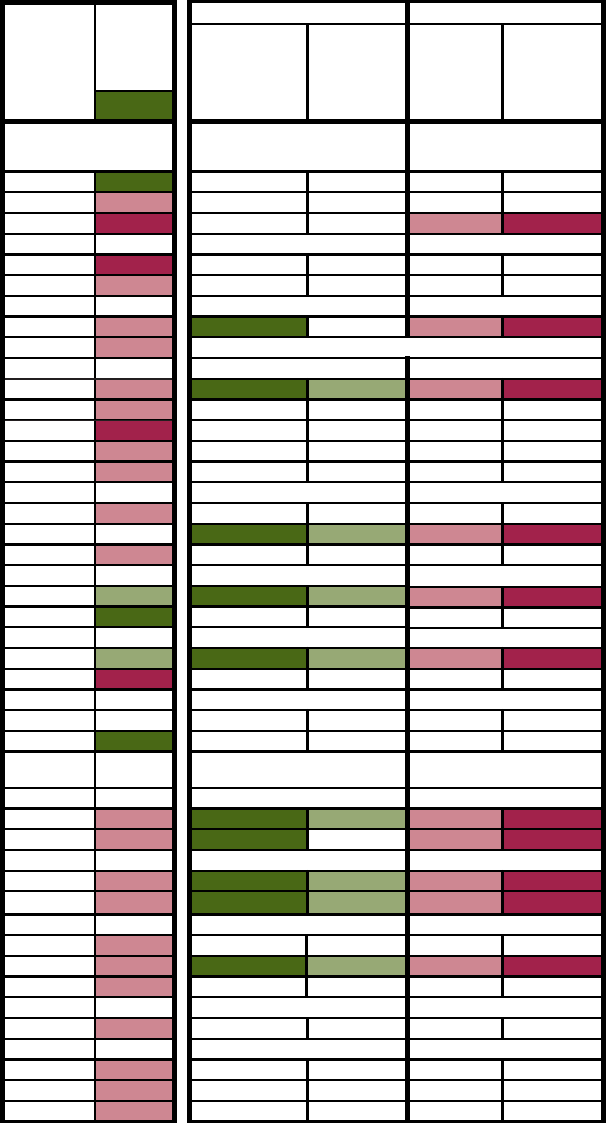

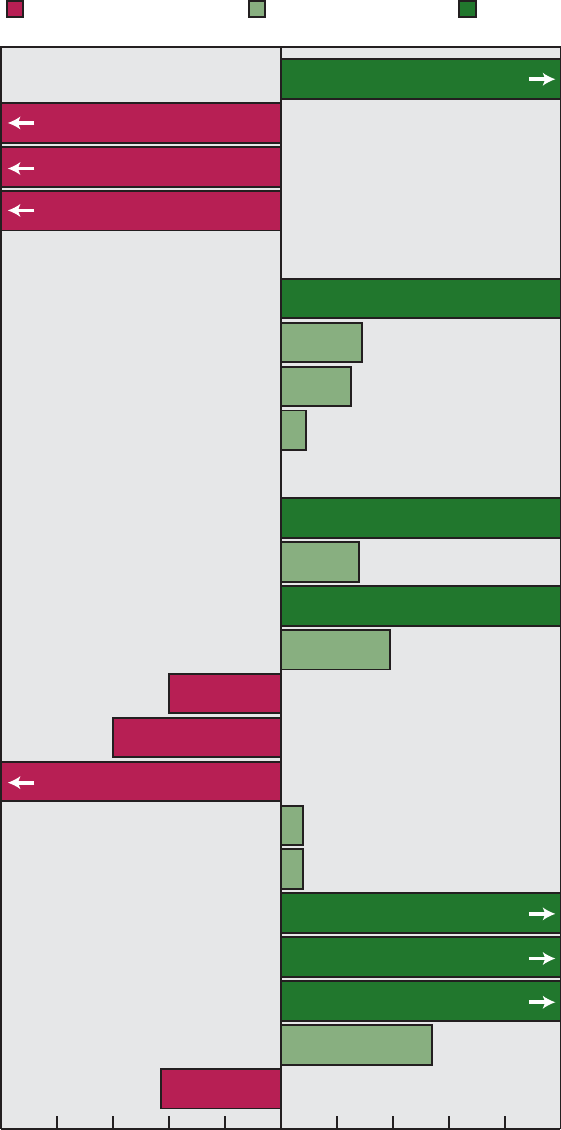

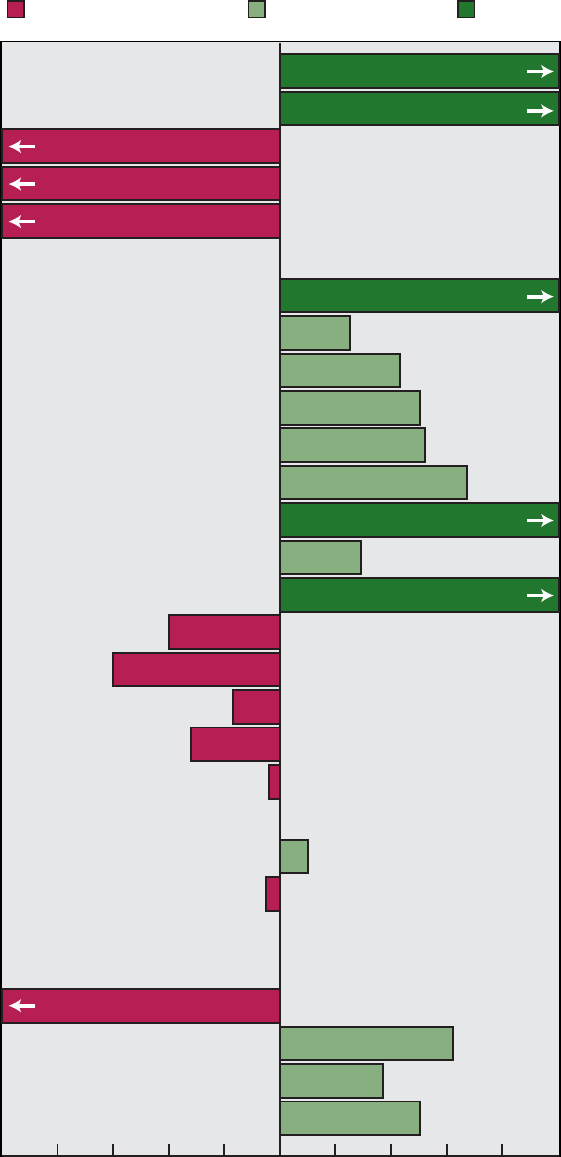

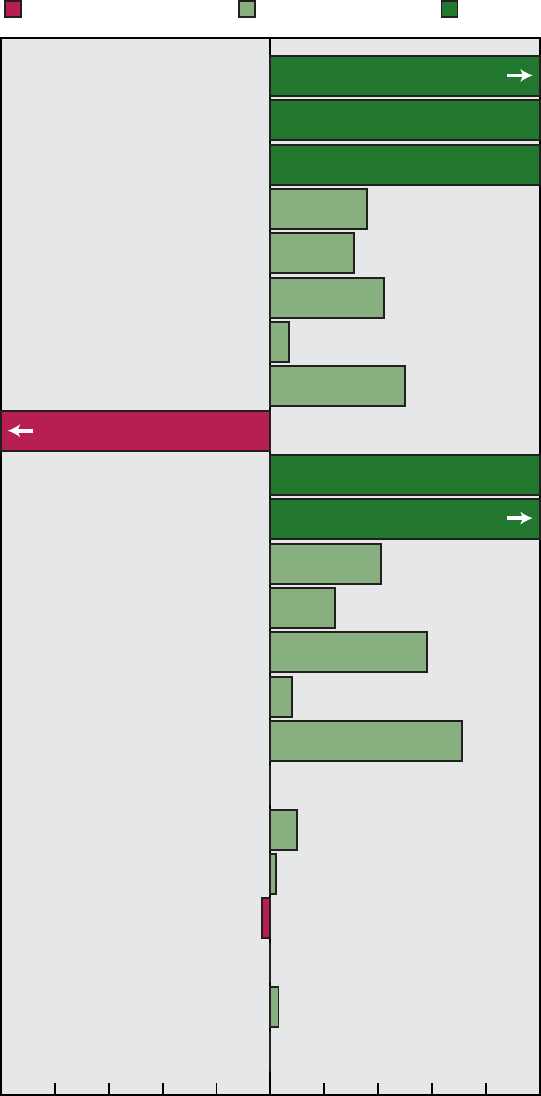

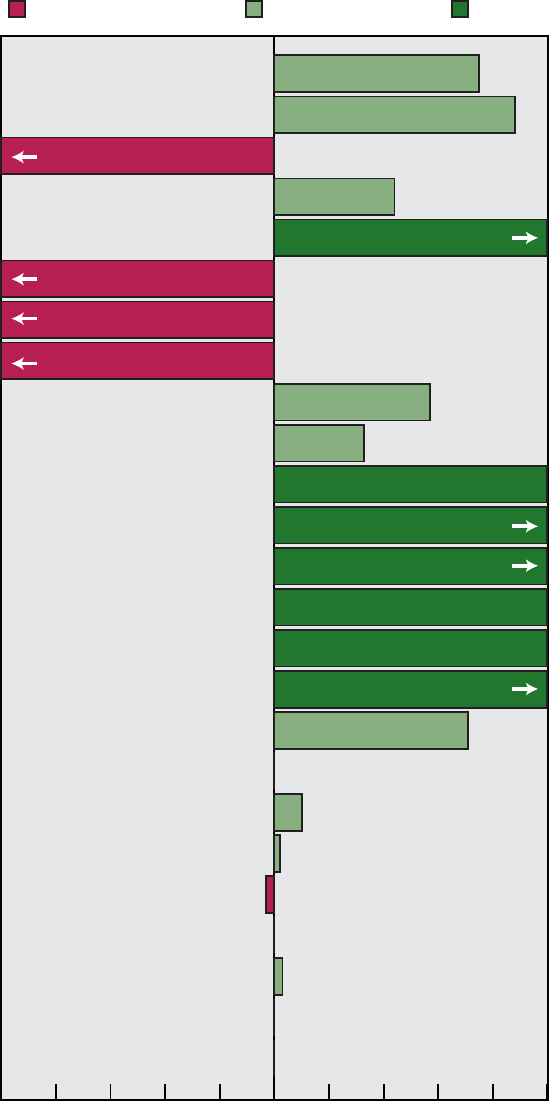

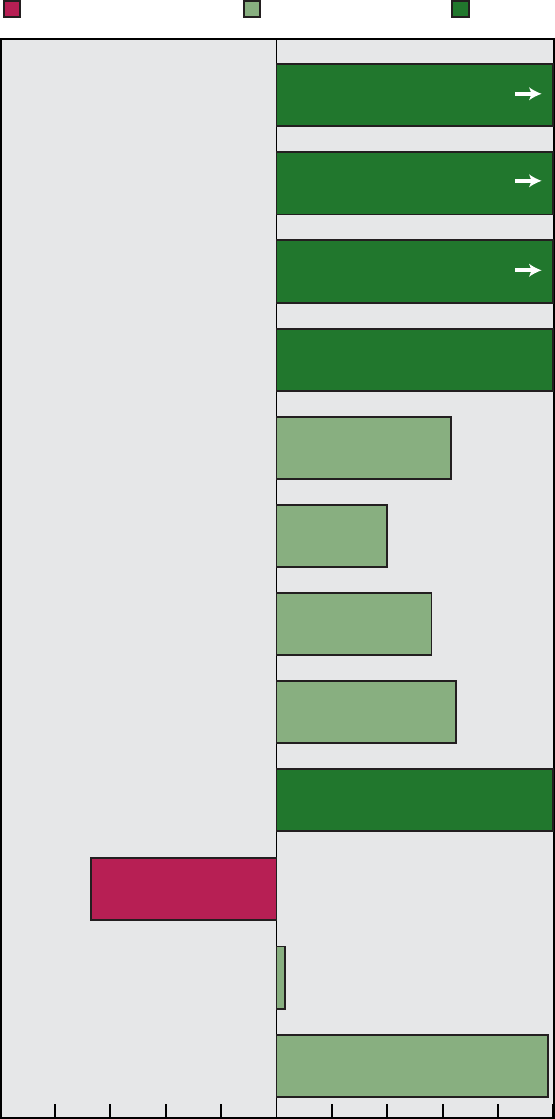

Area 22). Figure A shows the progress

of the objectives by priority area.

Progress for each individual objective is

shown in the priority area summary

tables (tables 1–22).

A number of Healthy People 2000

targets were revised during the

midcourse review process, in almost all

cases to make the target more

challenging (see section on Midcourse

Modifications). As a result, eight

objectives and nine subobjectives that

did not meet the targets in the final

assessment would have met their targets

if the original targets had not been

revised during the midcourse review.

0

1234567891011

Healthy People 2000

Priority Areas

12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

5

10

15

20

25

35

30

Number of objectives

Cannot assess

Moved away from target

No change

Mixed progress

Moved toward target

Met

Healthy People 2000 Final Review 3

Figure A. Healthy People 2000 objectives: Summary of progress by

priority area

Area Met

Moved

toward

target

Mixed

progress

No

change

Moved

away

from

target

Cannot

assess

1............ 1 6 0 1 4 1

2............ 6 13 2 0 6 0

3............ 7 10 5 1 1 2

4............ 3 7 4 0 2 4

5............ 0 8 3 0 0 1

6............ 5 1 1 0 7 1

7............ 7 4 0 0 5 3

8............ 5 2 2 1 1 3

9............ 7 11 2 2 2 2

10........... 7 7 1 1 4 0

11........... 4 9 2 0 1 1

12........... 2 5 0 0 1 0

13........... 1 12 1 1 2 0

14........... 1 8 2 1 3 2

15........... 3 12 0 0 2 0

16........... 7 8 2 0 0 0

17........... 2 6 3 0 11 1

18........... 5 5 1 0 3 3

19........... 4 7 2 0 1 3

20........... 3 7 5 0 2 2

21........... 1 2 2 0 1 2

22........... 2 4 1 0 0 0

Total ......... 83 154 41 8 59 31

Organization and Scope of this

Review

This Review is organized into three

major sections and presents the final

data collected for the 376 objectives that

comprise Healthy People 2000 (3).

While the data for these individual

objectives are the basis for this Review,

the additional analyses presented

provide further insight into the Nation’s

progress in health improvement over the

last decade.

The Introduction provides a brief

discussion of the history of the Healthy

People initiative, the current effort, and

the transition to the next decade in

Healthy People 2010 (4). There is also a

summary of progress for the past decade

and a description of the organization

and scope of this Review.

The first section presents

information that cuts across the 22

Healthy People 2000 priority areas. The

first part of this section summarizes

progress regarding the three broad goals

set in Healthy People 2000: Goal

1—Increase the span of healthy life,

Goal 2—Reduce health disparities, and

Goal 3—Achieve access to preventive

services. The second part of this section

presents data for three summary lists:

the Health Status Indicators (a set of

indicators of community health status

relevant to public health practice); the

Priority Data Needs (important

indicators for evaluating the health of a

population but not necessarily available

at all levels of government); and the

Sentinel Objectives (objectives

representative of the scope and

magnitude of the changes envisioned by

Healthy People 2000). Each of these

parts provide information through text,

charts, and tables describing progress

over the last decade by focusing on

particular issues that generally address

the 22 priority areas.

The second section consists of 22

chapters providing a progress report for

each of the Healthy People 2000

priority areas. Each chapter contains a

progress quotient chart, presenting a

summary of progress for each objective;

a discussion of the objectives that

addresses the area’s public health

significance, data highlights, progress

for the objectives, major results,

transition to Healthy People 2010, and

data issues; a summary data table; and

the full text of the objectives.

Technical notes and tables comprise

the Appendix, the third section. The

technical notes present and discuss data

and analysis issues involved in

monitoring the objectives and

subobjectives. The appendix provides

additional information that may be

useful in understanding and interpreting

the data. Additional sources of

information on Healthy People 2000 are

also presented.

This report is available on the

Internet at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/.

References

1. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report on

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Public

Health Service. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Washington. 1979.

2. Department of Health and Human Services.

Promoting health/preventing disease: Objectives

for the nation. Washington: Public Health Service.

1980.

3. Department of Health and Human Services.

Healthy people: National health promotion and

disease prevention objectives. Washington: Public

Health Service. 1991.

4. Department of Health and Human Services.

Healthy People 2010. 2d ed. With understanding

and improving health and objectives for improving

health. 2 vols. Washington: U.S. Government

Printing Office. 2000.

5. Department of Health and Human Services.

Healthy People 2000 midcourse review and 1995

revisions. Washington: Public Health Service.

1995.

6. Turczyn KM and Ryan CM. Healthy People

2000 midcourse revisions: A compendium. Healthy

people statistical notes; no 13. Hyattsville,

Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics.

1997.

4 Healthy People 2000 Final Review

Healthy People 2000 Goals

Healthy People 2000

Goals

The purpose of Healthy People

2000 was to commit the Nation to the

attainment of three broad goals. These

goals were to increase the span of

healthy life, to reduce health disparities

among Americans, and to achieve access

to preventive services for all Americans.

Attaining these broad goals would bring

the Nation’s health to its full potential.

Goal 1: Increase the Span of

Healthy Life

In the 20th century, the population

of the United States underwent a

continuous period of health

improvement that is unparalleled in

history. At the turn of the century, the

population was characterized by a

mostly low standard of living, poor

hygiene, poor nutrition, and a high

prevalence of communicable and acute

diseases typical of a population with

high mortality and high fertility. It

finished the century with a mostly high

standard of living, good hygiene, good

nutrition, and health-related habits

typical of populations with low

mortality and low fertility. In addition,

there was a low frequency of

communicable diseases and acute

conditions that were major causes of

most of the premature deaths in the

earlier part of the century. As a

consequence of the dramatic fall in

mortality, the average expectation of life

at birth for the total population

increased from 47.3 years in 1900 to

76.8 years in 1998 (1), an increase of

62 percent or 3.6 months per year for

each of the 98 years.

The same population and health

transitions that have jointly propelled

the average life expectancy by nearly 30

years, however, are also responsible for

ushering an era of new challenges. The

population is aging at an unprecedented

rate, resulting in an increased prevalence

of diseases that are noncommunicable

and not always fatal, but degenerative

and chronic. This adds a new dimension

to measuring the health of the

population. Expectation of life, which is

a traditional measure of longevity, has

now effectively become a ‘‘partial’’

measure of health for an aging

population that expects to live a long

life with degenerative diseases and

chronic conditions.

For an aging population fast

approaching the theoretical maximum

life span, the fundamental issues involve

not only longevity, but quality of life as

well. Quality of life (QOL) is a

subjective appraisal of life (2), relating

to the ‘‘goodness’’ of life as assessed by

external conditions (3). It is a

multidimensional concept that can, in

the broadest sense, include material

comfort, work, health, and active

recreation (4). The World Health

Organization’s concept of QOL on the

other hand, is based on the assessment

of the six broad domains that are related

to physical, psychological,

environmental, spiritual, level of

independence, and social relationship

(5). Some of these domains are directly

health related and others are not.

Healthy People 2000 is primarily

concerned with health-related QOL (6).

The formulation of the concept of

health-related QOL began in the 1970s

with a limited focus on domains of

physical function for measuring

activities such as activities of daily

living (5). Since then, the concept has

been expanded to include other domains,

such as general health perception,

limitations in usual roles, activity

restrictions, symptoms, and cognitive

psychological function (7).

The first goal of Healthy People

2000, to increase the span of healthy

life, is monitored using three statistics.

Life expectancy at birth (a measure of

longevity), the percent of people

reporting that their general health status

is fair or poor (a measure of

health-related QOL), and expected years

of healthy and unhealthy life (a

summary measure incorporating both

mortality and morbidity, known as years

of healthy life or YHL).

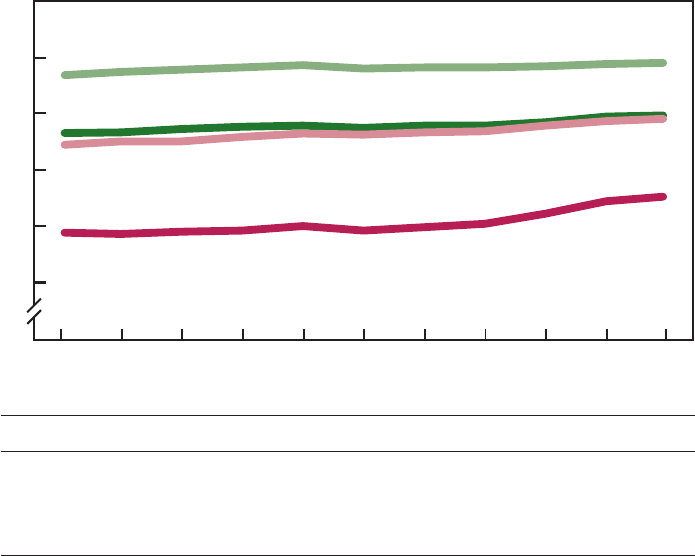

Life Expectancy at Birth

The expectation of life at birth is

the number of years a newborn would

expect to live if that person experienced

the mortality schedule existing at the

time of birth. This measure is one of the

most commonly used measures to

summarize mortality and study trends in

the span of human life. Figure B

presents the life expectancy at birth for

the U.S. population by sex and race for

the decade monitored by Healthy People

2000. Between 1988 and 1998 the

expectation of life increased from 74.9

to 76.7 years, an increase of nearly 2

years (2.4 percent). Life expectancy has

increased for all four population

subgroups shown. The biggest gain,

however, was for black males (3.2 years

or 5.0 percent), the population subgroup

with the lowest life expectancy.

Consequently, the difference between

the highest (white females) and lowest

(black males) life expectancy declined

over the decade from 10.5 years to 9.1

years, an indication that the disparity in

expectation of life among the subgroups

decreased in the 10-year period.

Fair or Poor Health

Between 1990 and 1996, the

percent of people reporting fair or poor

health increased from 9.9 to 10.4 percent

(figure C). Beginning in 1997, there was

a change in the methodology used to

measure this statistic in the National

Health Interview Survey so that data

collected in 1997 and subsequent years

are not directly comparable to those for

1996 and prior years. Between 1997 and

1998, the percent decreased slightly,

from 9.2 to 9.1 percent. Figure C also

displays the percent of people reporting

fair or poor health by socioeconomic

status (SES): poor (family income less

than poverty level), near poor (100 to

199 percent of poverty level), and

middle/high income (at least 200 percent

of poverty level). There is a clear

association between poor health and

poverty. In 1990, 22 percent of poor

people reported fair or poor health, three

times that reported by middle or high

income people (7 percent). In 1998, the

difference was slightly greater

(22 percent compared with 6 percent).

During the 1997–98 period, the trend in

the percent of people reporting fair or

poor health increased for the poor

population but decreased for the middle

or high-income population, widening the

disparity.

Healthy and Unhealthy Life

The broad purpose of the 319

Healthy People 2000 objectives was to

improve the health of the population.

Consequently, all objectives, at least

indirectly, involve increasing the span of

healthy life. However, one specific

objective (8.1, also duplicated as 17.1

and 21.1), targets a single measure of

the span of healthy life. The objective

measures health-related quality of life

using the summary measure of health

known as YHL. This measure estimates

the average number of years expected to

Healthy People 2000 Final Review 7

be lived in a healthy state for people of

a specified population. As a summary

measure of population health, this

measure incorporates mortality and

morbidity into a single statistic ( 8,9).

The mortality component utilizes total

mortality, while the morbidity

component is evaluated using two

measures: respondent-assessed health

and activity and functional limitations

due to chronic conditions. Individuals

are classified into 30 groups according

to both measures and these groups are

then assigned a quality-of-life score

(based on a mathematical model)

indicating the quality-of-life for that

group relative to a healthy state (10).

The YHL is calculated using a life table

approach that incorporates the

age-specific mortality with the

age-specific health related quality-

of-life score. The resulting ‘‘average

years of healthy life’’ is equivalent to

the average years a person would live if

he or she lived in a healthy state.

In 1990 the YHL was 64.0 years.

By 1998, this increased by 1.2 years to

65.2 years— a rise that was comparable

to the increase in expected years of life

(1.3 years between 1990 and 1998).

Consequently, average YHL as a percent

of total expected years of life was

largely unchanged. Figure D presents the

expected years of healthy life and

unhealthy life of the U.S. population by

race and ethnicity in 1998. The Hispanic

population has the greatest YHL.

However, Hispanics also have the

smallest proportion of life spent

equivalently in healthy states, that is

66.3 years of the total 82.1 expected life

years (81 percent). Blacks have the

smallest YHL and also a small

proportion of life spent in healthy states

(81 percent). Among whites, 86 percent

of the expected life years are

equivalently spent in healthy states.

Goal 2: Reducing Health

Disparities

The population of the United States

grew by 13 percent over the last decade,

and has increased in diversity at an even

greater rate (11). The aging of our

population is well documented and the

trend will continue for at least several

decades. Racial and ethnic minority

populations are among the fastest

growing of all communities in the

United States. Yet, these populations in

many respects, have poorer health and

remain chronically underserved by the

health care system. In many cases, the

health gaps initially identified in the

1985 Task Force Report on Black and

Minority Health (12) have grown.

Differences in accessibility, utilization,

quality of care, or benefits derived from

medical care are factors contributing to

inequality (13).

Healthy People 2000 included over

200 special population subobjectives to

address the overarching goal of reducing

health disparities in special populations

at higher risk than the total population

for death, disease, or disability (14).

Targets for these subobjectives were set

requiring a greater percent change with

the aim of reducing the gap between

these special populations and the total

population. A few subobjectives were

also included where, although the

special population was not at increased

risk, there was a disparate trend (for

example, 16.2b, lung cancer for

women). The populations highlighted in

Healthy People 2000 included American

Indian/Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific

Islander, black, Hispanic, women,

adolescents and young adults, older

adults, people with disabilities, and

people with low SES.

The Healthy People 2000

Midcourse Review and 1995 Revisions

resulted in the addition of many

subobjectives for these special

populations for a total of 49 objectives

or subobjectives for American

Indian/Alaska Native, 19 for Asian or

Pacific Islander, 97 for black, 84 for

Hispanic, 187 for women, 243 for

adolescents, 173 for older adults, 89 for

people with disabilities, and 65 for

people with low SES.

The objectives used for the

assessment of disparities include the

Healthy People 2000 subobjectives for

each of the nine special population

groups as well as other objectives

related to these groups. A list of the

objectives for each group can be found

in Appendix table VII. Some objectives

have measures for more than one group.

Progress toward the target can be

measured for all of these objectives;

however, not all the objectives can be

used to measure disparity. For groups

other than the racial/ethnic groups, a

0

1988 19901989 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

60

65

70

75

80

85

Years

White female

Black female

White male

Black male

1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

White female . 78.9 79.2 79.4 79.6 79.8 79.5 79.6 79.6 79.7 79.9 80.0

Black female. . 73.2 73.3 73.6 73.8 73.9 73.7 73.9 73.9 74.2 74.7 74.8

White male . . . 72.2 72.5 72.7 72.9 73.2 73.1 73.3 73.4 73.9 74.3 74.5

Black male . . . 64.4 64.3 64.5 64.6 65.0 64.6 64.9 65.2 66.1 67.2 67.6

SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, National Vital Statistics System.

8 Healthy People 2000 Final Review

Figure B. Life expectancy at birth: United States, 1988–98

relatively small proportion of the

objectives are applicable for assessment

of disparity. This is because, for these

groups, most objectives target the group

directly and do not also target a

reference population that could be used

to assess disparity status. Disparity was

assessed by comparing the percent

change between the baseline and last

data point for the special population

subobjective with the percent change

observed for the total population used to

track the objective. (See section on

Disparity Measurement in the

Appendix.)

The 1990s saw significant

improvements in the ability to track

progress for Healthy People 2000

objectives by special populations.

Leading into the decade, in 1989,

Hispanic origin was included for the

first time on standard birth and death

certificates recommended for use by all

States. By the end of the decade, the

number of States that publish vital

statistics data by race and ethnicity

increased from 19 to 27—surpassing the

Healthy People 2000 target. Despite

these improvements, data were still

missing at the end of the decade to

assess progress for 6 percent of the

objectives for American Indian/Alaska

Native, 5 percent for Asian or Pacific

Islander, 2 percent for black, 8 percent

for Hispanic, 10 percent for women,

26 percent for adolescents, 10 percent

for older adults, 7 percent for people

with disabilities, and 6 percent for

people with low SES.

At the conclusion of the decade,

more than one-half of the special

population subobjectives showed a

narrowing or elimination of disparities.

In addition, progress for special

populations was made in a number of

areas. However, only 16 percent of the

year 2000 targets for the special

population subobjectives were met

compared with 22 percent of all 318

unduplicated objectives and

subobjectives.

One of the two overarching goals

for Healthy People 2010, launched in

January 2000, extends this goal from

reducing disparities to actually

eliminating health disparities. As a

result, Healthy People 2010 has the

same target for all population groups,

including racial and ethnic groups. As

noted during the public comment period

for Healthy People 2010, ‘‘the ambitious

goal of eliminating health disparities

demands broader and more

interdisciplinary remedies than those

previously considered.’’

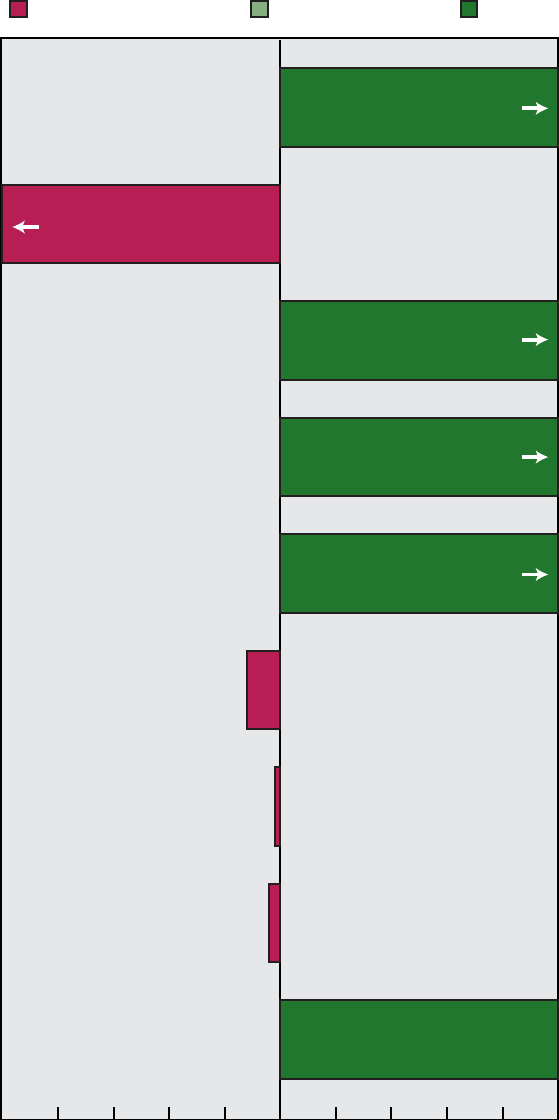

The following sections discuss

progress toward reducing disparities and

progress toward the year 2000 targets

for each of the nine special population

groups addressed by Healthy People

2000. A summary of progress is

graphically shown for each group along

with text discussion of some specific

examples. The specific examples are

shown for illustrative purposes only, and

do not infer priority or importance. A

complete assessment of progress toward

the target and progress toward reducing

disparity for the objectives in each of

the nine special population groups is

shown in Appendix table VII.

Reducing Disparities: American

Indian/Alaska Native

Figure E demonstrates progress

made in reducing disparities in the

health status of American Indians/Alaska

Natives. Twenty-four (55 percent) of the

forty-four American Indian/Alaska

Native subobjectives showed a reduction

or elimination of disparities in health

status between this population and the

total population. Of these 24 objectives,

20 met or moved toward their year 2000

targets.

Hepatitis A (20.3j) and bacterial

meningitis (20.7a) showed remarkable

improvement— surpassing year 2000

targets and narrowing the gap. Diabetes

prevalence for American Indians and

Alaska Natives, however, increased,

although the gap narrowed (17.11a)

because the prevalence for the total

population increased at an even greater

rate. Diabetes-related deaths (17.9b) and

end-stage renal disease rates (17.10b)

increased and the gaps widened.

0

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

5

10

15

20

25

30

Below poverty level

100-199% of poverty level

200% or more of poverty level

Percent

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

Below poverty

level ........ 22.1% 22.8% 23.8% 24.2% 23.7% 23.7% 23.8% 21.4% 22.2%

100–199% of

poverty level . . 14.5% 14.7% 15.0% 15.7% 15.0% 15.5% 15.2% 14.6% 15.6%

200% or more of

poverty level . . 6.8% 6.8% 7.0% 6.8% 6.9% 6.7% 6.6% 6.1% 5.7%

SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, National Health Interview Survey.

NOTE: The survey was redesigned in 1997. Data for 1997 and 1998 may not be directly

comparable with those for previous years.

Healthy People 2000 Final Review 9

Figure C. Percent of people with fair or poor health:

United States, 1990–98

Reducing Disparities: Asian or

Pacific Islander

Figure F represents the disparity

status of the subobjectives for Asians or

Pacific Islanders. Twelve of the sixteen

subobjectives for this group showed a

reduction or elimination of disparities,

and all 12 subobjectives either met or

moved toward their targets.

For example, the year 2000 target

was met and disparity decreased for flu

vaccinations among the elderly (21.2).

Cigarette smoking decreased for

Southeast Asian males at the beginning

of the decade and the disparity narrowed

(3.4g). The number of Hepatitis B cases

among Asian or Pacific Islander children

dramatically decreased (20.3d) although

disparity was not assessed for this

objective because the measure for the

subobjective was different from that for

the main objective. One objective, new

tuberculosis cases (20.4a), showed a

widening of disparity.

Reducing Disparities: Black or

African American

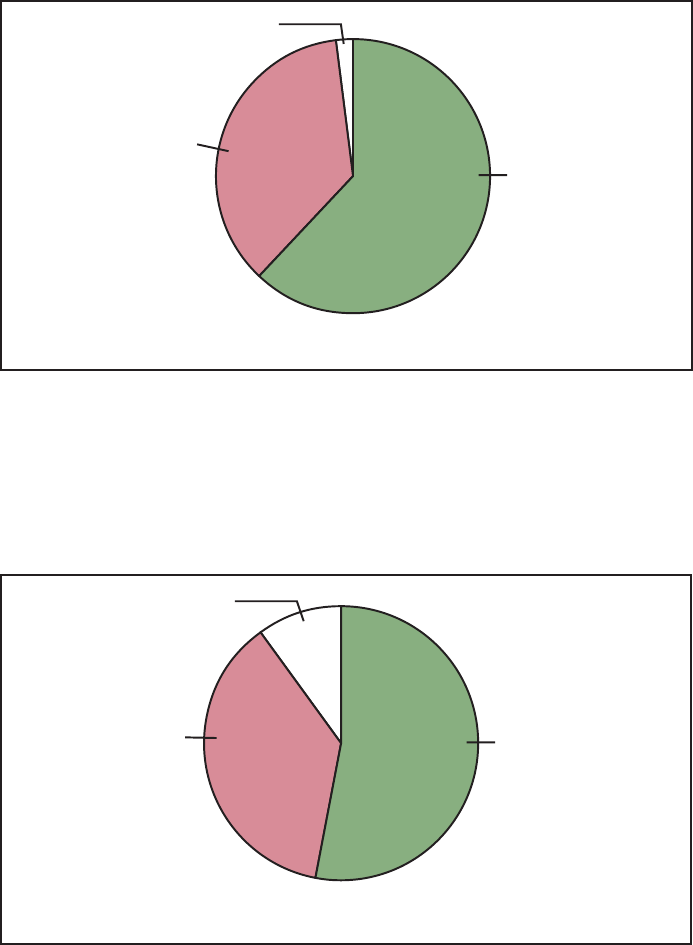

Figure G depicts the status of

subobjectives to reduce disparities

between black Americans and the total

population. Elimination or reduction of

disparities occurred for 55 (62 percent)

of the 89 subobjectives. Of these 55

subobjectives, 50 either met or moved

toward their targets.

Objectives for which targets were

met and disparities were reduced

included cancer deaths (2.2a),

firearm-related deaths (7.3a),

unintentional injuries (9.2a), clinical

breast examination and mammography

(16.11e), and syphilis (19.3a).

Unfortunately, diabetes prevalence

(17.11e), diabetes-related deaths (17.9a),

lower extremity amputations (17.10c),

maternal mortality (14.3a) and fetal

alcohol syndrome (14.4b) increased and

the disparity gaps widened.

Reducing Disparities: Hispanic or

Latino

Figure H shows the status of the 76

subobjectives for Hispanic persons.

Forty (52 percent) of these subobjectives

showed a reduction in disparity between

Hispanics and the total population. It is

interesting to note that 10 of these 40

subobjectives moved away from their

targets but at a slower rate than the

objectives for total population.

Objectives for which targets were

met and disparities were reduced

included infant mortality for Puerto

Ricans (14.1c), use of clinical breast

examination and mammography among

Hispanic women over 50 years of age

(16.11c), and rates of congenital syphilis

(19.4b). Adolescent pregnancy (5.1b)

and high school completion rates (8.2a),

however, remained essentially the same.

Reducing Disparities: Women

Figure J depicts progress made in

reducing health disparities for women in

the United States. Of the 19 objectives

for which disparities between women

and the total population can be assessed,

9 objectives showed a reduction or

elimination of health status inequity. Of

these nine objectives, six either met or

moved toward their targets.

Progress was made in smoking

prevalence (3.4) and homicide rates

among African American women (7.1e).

Unfortunately, although new cases of

AIDS decreased in recent years, the rate

of decrease for women (18.1d) was less

than that for the total population.

Reducing Disparities: Adolescents

and Young Adults

The pie chart depicted in figure K

reflects changes in disparities between

adolescents and young adults and the

total population. Disparities in seven

subobjectives decreased or were

eliminated, while five widened. All

seven of the subobjectives that reduced

or eliminated the disparity either met or

moved toward their targets.

Motor vehicle crash death rates for

people 15–24 years (9.3b) and

drownings for males 15–34 years

decreased substantially and the

disparities gaps narrowed. However,

there were increases in disparities for

rape or attempted rape (7.7a) and

adolescent gonorrhea (19.1b).

0

15

30

45

60

75

90

Expected years of life

* Hispanic origin can be of any race.

Healthy

Total White Black Hispanic*

Unhealthy

Total White Black Hispanic*

Healthy life expectancy ........ 65.2 66.1 57.8 66.3

Unhealthy life expectancy ...... 11.5 11.2 13.5 15.8

Total life expectancy .......... 76.7 77.3 71.3 82.1

*Data are preliminary. Hispanic includes people of any race with Hispanic origin.

SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, National Vital Statistics System and National Health Interview Survey.

10 Healthy People 2000 Final Review

Figure D. Expected years of healthy and unhealthy life:

United States, 1998

Reducing Disparities: Older Adults

Figure L depicts progress on

subobjectives used to measure disparity

between older adults and the total

population. Eleven of the nineteen

subobjectives measured showed a

reduction or elimination in disparity, and

all of these either met or moved toward

their targets.

There was nearly a 20–percent

reduction in the rate of white male

suicide in the elderly population (6.1c),

narrowing the gap with the total

population. This reduction is reflected in

the increase in years of healthy life for

adults 65 years and over (8.1c). There

were, however, increases in the

disparities for death rates due to falls

(9.4a,b) and motor vehicle crashes

(9.3c).

Reducing Disparities: People with

Disabilities

Figure M shows progress made on

the six subobjectives among people with

disabilities for which disparity could be

measured. The graph indicates that

disparities have been reduced or

eliminated for one-half of the

subobjectives for people with

disabilities. One of these subobjectives

moved away from its target, although at

a slower rate than the total population,

thus reducing the disparity.

Data indicate that progress is being

made in reducing the percent of

overweight persons in the disabled

population (1.2e). In addition, disparities

in sedentary lifestyle between the

disabled and the total population are

being reduced (1.5b).

Reducing Disparities: People with

Low Socioeconomic Status

The chart shown in figure N

demonstrates the disparity status of the

36 subobjectives used to measure

disparities between people with low

socioeconomic status (SES) and the total

population. While nearly one-third of

the subobjectives showed a widening or

no change in disparity, 21 (58 percent)

improved. But of these 21 subobjectives,

3 moved away from their targets,

indicating that the total population

moved away from its target at a faster

rate than those with low SES.

Encouraging improvements were

seen in the areas of breast feeding

(2.11a) and the use of contraception

(5.12b,c). Conversely, there were

increases in the percent of overweight

persons (1.2a) and certain oral health

issues (for example, prevalence of

gingivitis, 13.5a).

Goal 3: Achieving Access to

Preventive Services

Access to health services—

including preventive care, primary care,

and tertiary care—often depends on two

independent factors: having health

insurance and having a regular source of

health care (15–18). Uninsured people

are less than half as likely as people

with health insurance to have a primary

care provider; to have received

appropriate preventive care, such as

recent mammograms or Pap tests; or to

have had any recent medical visits. Lack

of insurance also affects access to care

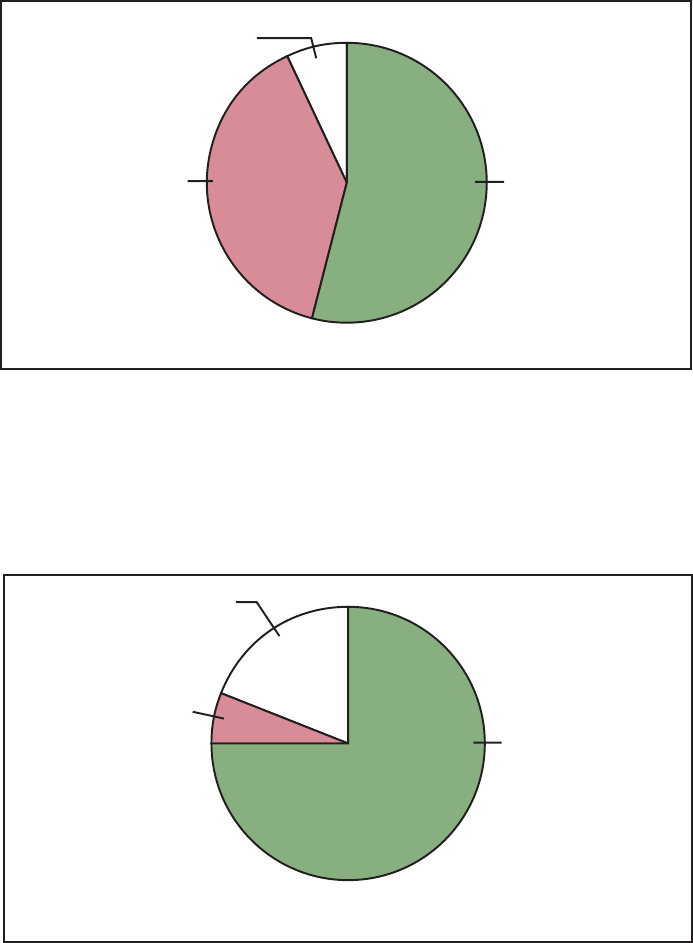

Disparity:

Eliminated/Narrowing

54% (N=24)

Cannot assess

7% (N=3)

Disparity:

Widening/No change

39% (N=17)

Number of objectives = 44

NOTE: Disparity is assessed by comparing the change for the special population with the change for

the total population. Not all objectives for the special population are applicable to disparity assessment.

(See Disparity Assessment section in the Appendix.)

Disparity:

Eliminated/Narrowing

75% (N=12)

Cannot assess

19% (N=3)

Disparity:

Widening/No change

6% (N=1)

Number of objectives = 16

NOTE: Disparity is assessed by comparing the change for the special population with the change for

the total population. Not all objectives for the special population are applicable to disparity assessment.

(See Disparity Assessment section in the Appendix.)

Healthy People 2000 Final Review 11

Figure E. Assessment of disparity for American Indian/Alaska

Native objectives

Figure F. Assessment of disparity for Asian or Pacific Islander

objectives

for relatively serious medical conditions.

Evidence suggests that lack of insurance

over an extended period significantly

increases the risk of premature death

and that death rates among hospitalized

patients without health insurance are

significantly higher than those with

insurance (19). Another study showed

that, among those without insurance,

chronically ill persons are even less

likely than those with acute conditions

to get health care services they need

(20). Beyond having health insurance,

access depends on the actual benefits

offered by the insurance plan. Many

plans do not offer adequate benefits for

some services such as mental health, eye

care, oral health, assistive devices, and

drugs. Medicaid expansions that increase

the proportion of a State’s population

eligible for Medicaid lead to increases

in enrollment, enhanced utilization of

medical services, and lower child death

rates (21).

More than 40 million persons in the

United States do not have a particular

doctor’s office, clinic, health center, or

other place where they usually go to

seek health care or health-related advice.

Even among privately insured persons, a

significant number lacked a usual source

of care or reported difficulty in

accessing needed care due to financial

constraints or insurance problems (15).

Barriers to obtaining health care can be

financial, structural, or personal.

Financial barriers include not having

health insurance, not having enough

health insurance to cover needed

services, or not having the financial

capacity to cover services outside a

health plan or insurance program.

Structural barriers include the lack of

primary care providers, medical

specialists, or other allied health care

professionals (including personal

assistants and caregivers) to meet

special needs; the lack of health care

facilities or exam equipment; or the lack

of transportation. Personal barriers

include cultural or spiritual differences,

language barriers (including sign

language), not knowing what to do or

when to seek care, or mistrust or

concerns about confidentiality or