The Platform for

Collaboration on Tax

Practical Toolkit to Support the Successful

Implementation by Developing Countries of

Effective Transfer Pricing Documentation

Requirements

International Monetary Fund (IMF)

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

United Nations (UN)

World Bank Group (WBG)

1

This document has been prepared in the framework of the Platform for Collaboration on Tax (PCT)

under the responsibility of the Secretariats and Staff of the four organizations. The work of the PCT

Secretariat is generously supported by the Governments of Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway,

Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. This report should not be regarded as the officially endorsed views

of those organizations, their member countries, or the donors of the PCT Secretariat.

The toolkit has benefited from comments submitted during the period of public review in September–

November 2019. The PCT partners wish to express their gratitude for all submissions received.

2

CONTENTS

ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................................................... 5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................... 6

PART I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 8

1.1 Introduction: Why a toolkit on implementing Transfer Pricing documentation? ................. 8

1.2 Structure of this Toolkit ............................................................................................................................... 9

1.3 Scope .................................................................................................................................................................. 9

1.4 Context and background of transfer pricing documentation requirements ........................ 12

1.5 Objectives of transfer pricing documentation requirements ...................................................... 13

1.6 Policy principles ............................................................................................................................................ 14

Ensuring international consistency .................................................................................................................. 15

PART II. OPTIONS FOR COUNTRIES TO IMPLEMENT TRANSFER PRICING DOCUMENTATION ....... 16

2.1 Regulatory framework ................................................................................................................................ 16

2.1.1 General considerations .............................................................................................................................. 16

2.1.2 Burden of proof ............................................................................................................................................ 17

2.2 Confidentiality ............................................................................................................................................... 19

2.3 Timing Issues ................................................................................................................................................. 20

2.4 Penalties and compliance incentives .................................................................................................... 21

2.5 Accessing documents held outside the jurisdiction ....................................................................... 24

2.6 Simplification and exemptions. .............................................................................................................. 26

PART III. SPECIFIC DOCUMENTATION ELEMENTS .............................................................................................. 28

3.1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 28

3.2 Transfer pricing returns ............................................................................................................................. 28

3.2.1 Functions of transfer pricing returns ................................................................................................... 28

3.2.2 Format and content .................................................................................................................................... 29

3.2.3 Submission mechanism ............................................................................................................................ 30

3.2.4 Regulatory framework ............................................................................................................................... 31

3.2.5 Timing issues ................................................................................................................................................. 33

3.2.6 Enforcement .................................................................................................................................................. 34

3.2.7 Confidentiality............................................................................................................................................... 36

3.2.8 Simplification and exemptions ............................................................................................................... 36

3.3 Transfer pricing studies ............................................................................................................................. 38

3

3.3.1 Functions of transfer pricing studies ................................................................................................... 38

3.3.2 Format and content .................................................................................................................................... 40

3.3.3 Regulatory framework ............................................................................................................................... 46

3.3.4 Timing issues ................................................................................................................................................. 46

3.3.5 Enforcement .................................................................................................................................................. 49

3.3.6 Confidentiality............................................................................................................................................... 52

3.3.7 Simplification and exemptions ............................................................................................................... 52

3.4 Country by Country Reporting ............................................................................................................... 58

3.4.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 58

3.4.2 Filing mechanism ......................................................................................................................................... 69

3.4.3 Format and Content ................................................................................................................................... 71

3.4.4 Legislative and regulatory framework ................................................................................................. 72

3.4.5 Enforcement .................................................................................................................................................. 75

3.4.6 Practical issues on the implementation of CbC Reporting ......................................................... 77

3.5 Other information gathering mechanisms (Transfer pricing questionnaires and ad hoc

information requests) ................................................................................................................................................ 82

3.5.1 Functions of transfer pricing questionnaires and ad hoc information requests ................. 83

3.5.2 Format and content .................................................................................................................................... 83

3.5.3 Regulatory framework ............................................................................................................................... 83

3.5.4 Timing issues ................................................................................................................................................. 83

3.5.5 Enforcement .................................................................................................................................................. 83

3.5.6 Confidentiality............................................................................................................................................... 84

PART IV. CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 85

Annex 1 ............................................................................................................................................................................... 86

Sample primary legislation to implement transfer pricing documentation requirements ........ 86

Annex 2 ............................................................................................................................................................................... 94

Illustrative examples – Countries’ transfer pricing documentation rules ......................................... 94

Annex 3 ............................................................................................................................................................................... 97

Illustrative examples - Transfer pricing annual returns ........................................................................... 97

India Form No. 3ECB ............................................................................................................................................. 98

Annex 4 ............................................................................................................................................................................ 100

Master file content (from Annex I to Chapter V of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines) ... 100

Local file content (from Annex II to Chapter V of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines) ..... 102

Annex 5 ............................................................................................................................................................................ 104

4

Belgium: Transfer pricing documentation package ............................................................................... 104

Annex 6 ............................................................................................................................................................................ 106

Master file and local file - Filing obligations in selected countries ................................................. 106

Annex 7 ............................................................................................................................................................................ 109

Example - Exemptions regimes (transfer pricing studies) ................................................................... 109

Annex 8 ............................................................................................................................................................................ 110

CbC Report template (from Annex III to Chapter V of the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines)

.................................................................................................................................................................................... 110

Template for the Country-by-Country Report – General instructions ............................................ 112

References ....................................................................................................................................................................... 117

5

ACRONYMS

APA Advance Pricing Arrangement

BEPS Base Erosion and Profit Shifting

CAA Competent Authority Agreement

CbC Country-by-Country

CRS Common Reporting Standard or Standard for Automatic Exchange of Financial

Account Information in Tax Matters

CTS Common Transmission System

DTC Double Tax Convention

DWG Development Working Group of the G20

EOI Exchange of Information

EU The European Union

GAAP Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

Global Forum Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes

IMF International Monetary Fund

MAP Mutual Agreement Procedure

MAP APA Advance Pricing Arrangement under the Mutual Agreement Procedure

MNE Multinational Enterprise

MTC Model Tax Convention

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

QCAA Qualifying CAA

SME Small and Medium Enterprises

SPE Surrogate Parent Entity

TIEA Tax Information Exchange Agreement

UN United Nations

UPE Ultimate Parent Entity

WBG World Bank Group

6

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Transfer pricing rules apply to taxpayers that conduct transactions with associated parties.

In most countries, they require the taxable profit of such taxpayers to be computed in

accordance with the arm’s length principle – that is, on the assumption that the price and other

conditions of the transactions are the same as those that would be expected had the transaction

been between unrelated parties.

In establishing the prices and other conditions for transactions between associated

enterprises and assessing whether such prices and conditions are consistent with the “arm’s

length principle”, it is necessary for enterprises and tax administrations to conduct what is

often called a ‘transfer pricing analysis’. This analysis requires taxpayers or tax administrations

to identify and understand the key features of a transaction between related parties, and analyze

the functions performed, risks assumed and assets used by those parties in order to determine and

apply the most appropriate transfer pricing method. The application of the transfer pricing method

normally relies on information from external and internal sources to find one or more comparable

uncontrolled transactions or, in the application of a profit split method, to determine the value of

the contribution of the respective parties.

1

In some cases, this analysis involves a complex

examination of a large amount of information. This Toolkit concerns the measures that tax

administrations use to require taxpayers to document all stages of their transfer pricing analysis. It

has a specific emphasis on developing countries.

Robust transfer pricing documentation rules are a prerequisite for the effective

implementation of transfer pricing rules. The requirement to prepare, keep or submit

information enhances compliance and enables tax administrations to access the information

necessary to enforce their transfer pricing regulations. The access to such information also allows

tax administrations to focus their efforts and to deploy their limited resources on taxpayers and

transactions that pose the greatest risk of base erosion and profit shifting and should reduce any

unnecessary taxpayer compliance costs, including those which arise from unfocused or misdirected

audits. However, comprehensive documentation can be costly for the taxpayer, and finding the

right balance between the tax authorities’ needs and avoiding excessive and unnecessary

compliance costs is not always an easy task.

The outcome of Action 13 of the OECD/G20 BEPS initiative outlined a standardized approach

to transfer pricing documentation aimed at balancing compliance imperatives with

compliance costs. The approach consists of three elements: a master file, containing information

on the overall multinational enterprise (MNE) group; a local file, containing specific information on

the local enterprise; and a Country-by-Country (CbC) Report, which describes the high-level

financial and economic position of the MNE group. This Toolkit takes the view that all three

elements are potentially beneficial for developing countries and focuses on the issues related to

the implementation of each of them. It should be noted that CbC reporting is one of the four BEPS

1

The process of the comparability analysis has been described in the Toolkit “Addressing Difficulties in Assessing

Comparable Data for Transfer Pricing Analysis”, http://www.oecd.org/tax/toolkit-on-comparability-and-mineral-

pricing.pdf. See also Section 3.5 of the UN Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries (2017).

7

minimum standards, and that members of the OECD’s Inclusive Framework

2

commit to its

implementation, and to take part in the Inclusive Framework’s peer review process.

This Toolkit also describes additional approaches to documentation, including information

required in or to be filed along with the tax return (such as transfer pricing return schedules), and

other measures such as questionnaires.

2

In response to the call of G20 Leaders in November 2015, the OECD and G20 members established an Inclusive

Framework which allows interested countries and jurisdictions to work on an equal footing with OECD and G20

members on the implementation of the OECD/ G20 BEPS Package.

Membership of the Inclusive Framework builds on the existing OECD Committee on Fiscal Affairs, to include

interested countries and jurisdictions that commit to the comprehensive BEPS package and its consistent

implementation. They participate in the decision-making plenary body, as well as all of the technical working groups.

As of October 2020 there are over 135 members and 14 observer organisations. See the list of members and

observers of the Inclusive Framework at https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/

8

PART I. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Introduction: Why a toolkit on implementing Transfer Pricing

documentation?

The relevance of transfer pricing to developing countries, together with the challenges faced

by low-capacity or inexperienced tax administrations, has been high on the regional and

global tax agenda in the last several years. The OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS)

initiative brought the issue to the fore, and served to highlight the relevance to, and challenges

faced by, developing countries, which were specifically discussed in a two-part report to the G20

Development Working Group: ‘The Impact of BEPS on Low Income Countries’ (July and August

2014).

3

This is being followed up with a number of Toolkits developed by International

Organizations,

4

which are intended to support developing countries implement those anti-BEPS

measures that have most relevance to them.

Research using firm-level information and selected country experiences suggest that the

introduction of effective documentation obligations is a critical component of compliance

management strategies to address transfer mispricing. Since 1994 the number of countries

with transfer pricing documentation requirements has increased more than tenfold (see Figure 1

below), and this has been linked to a reduction in observable indicators of profit shifting,

5

possibly

related to better-targeted enforcement activities and self-compliance induced by the obligations

to revisit the related party dealings more systematically.

Figure 1 : Timeline of Effective Transfer Pricing Documentation Rules by number of

countries 1994–2014

3

OECD (2014), Two-part report to G20 Development Working Group on the impact of BEPS in Low Income

Countries 2014, OECD Publishing, Paris. //www.oecd.org/tax/tax-global/report-to-g20-dwg-on-the-impact-of-

beps-in-low-income-countries.pdf

4

IMF, OECD, UN, WBG

5

Cooper, Joel, Randall Fox, Jan Loeprick, and Komal Mohindra. 2016. Transfer Pricing and Developing Economies:

A Handbook for Policy Makers and Practitioners. Directions in Development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

doi:10.1596/978-1-4648- 0969-9. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO p.7; and Beer and Loeprick,

2015. ‘Profit Shifting Drivers of Transfer (Mis)Pricing and the Potential of Countermeasures’. International Tax and

Public Finance 22 (3): 426-51

0

20

40

60

80

100

1994-1997 1998-2000 2001-2002 2003-2004 2005-2007 2007-2011 2011-2014

Source: World Bank (2016), based on Oosterhoff, 2008 and PwC, 2014.

9

1.2 Structure of this Toolkit

This toolkit is intended to provide an analysis of policy options and a “source book” of

guidance and examples to assist low capacity countries in implementing efficient and

effective transfer pricing documentation regimes. Key points from these sources are

reproduced, for ease of reference.

This first part of the Toolkit provides information on the background, context and objectives of

transfer pricing documentation regimes. Part II then discusses a number of general policy options

and legislative approaches relevant to all types of documentation requirements.

Part III focuses more specifically on each kind of documentation in turn and examines the specific

policy choices that are relevant to each, as well as providing a number of examples of country

practices. This format inevitably involves some repetition; however, a reader interested in

implementing a particular type of documentation requirement can find all of the relevant

information in a single section.

The final part sets out a number of conclusions.

1.3 Scope

For the purposes of this Toolkit, the term ‘transfer pricing documentation’ comprises the

following:

1. Group level documentation. This category includes documents such as the master file and the

Country-by-Country (CbC) Report described in Action 13 of the OECD/G20 BEPS initiative (“BEPS

Action 13 Report”). Note that while there is a high degree of standardization of the CbC Report (as

it applies globally), countries have taken a variety of approaches on the implementation of the

master file.

2. Entity level documentation, generally comprising one or more of the following:

• The local file or similar (e.g. transfer pricing study), providing details of a local taxpayer’s

intragroup transactions, and a description of the transfer pricing analyses giving rise to the

selected method and comparables;

• A transfer pricing specific return or schedule, separate from the income tax return, that may

be required to be lodged periodically with the tax administration;

• Any schedule to the tax return i.e. one or more transfer pricing specific questions included

on a tax return or a schedule to the tax return; and

• Questionnaires issued by the tax authority on a regular or ad-hoc basis.

It should be noted that the term ‘transfer pricing documentation’ does not include business

documents or records such as invoices, contracts, communications etc., which might be used to

support or substantiate amounts of assessable income or deductible expenses. Typically, however,

tax administrations require taxpayers to keep this type of information and to submit specified items

during an audit. Legislation may stipulate the records that taxpayers are required to keep, and the

10

length of time they should be kept. For completeness and comparison purposes, this type of record

keeping requirement is briefly discussed at various points in this Toolkit.

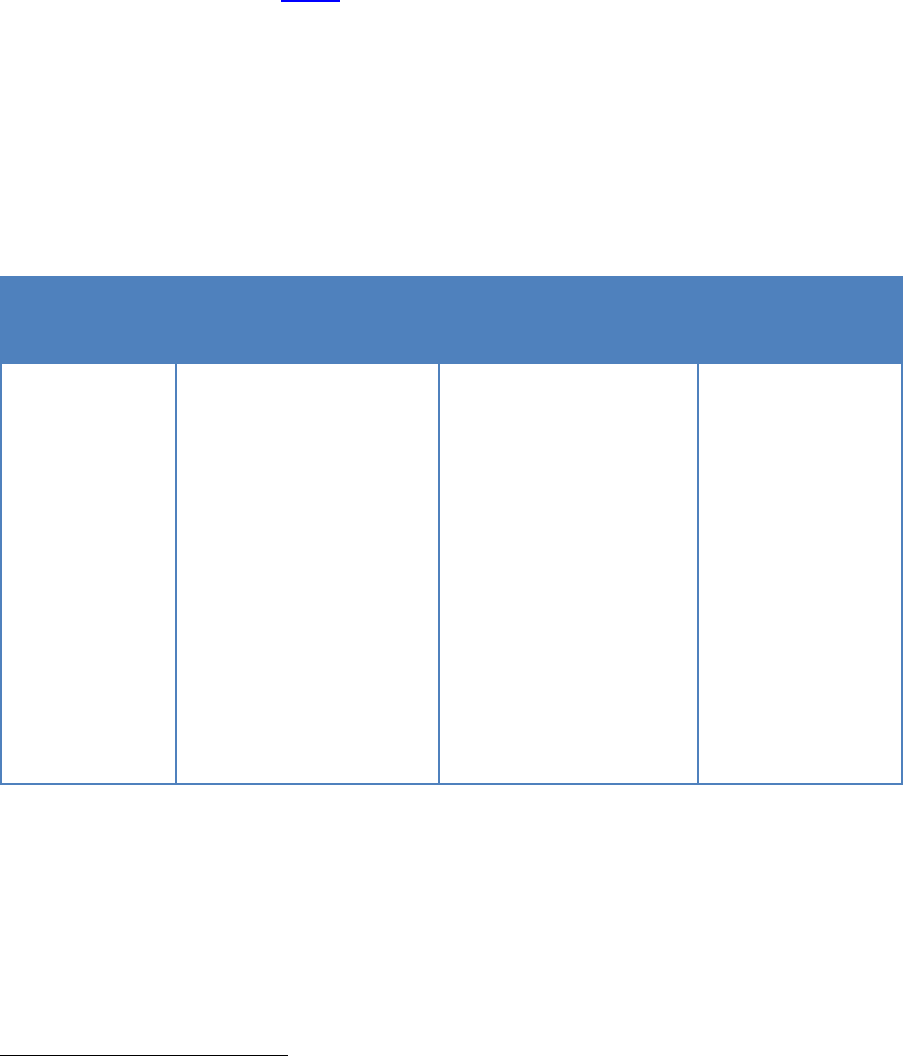

Table 1 : Type and scope of transfer pricing documentation

Type of

Documentation

Group or local

entity

documentation

Entity submitting

document

Required by

legislation, and

enforced by

penalties

BEPS

minimum

standard

Transfer pricing

returns or

schedules

Local

Local taxpayer

Yes (where

applicable)

No

Local file

Local

Local taxpayer

Generally, yes

No

Master file

Group

Local taxpayer

Generally, yes

No

CbC Reports

Group

Depends on domestic

legal obligations. The

Action 13 standard

generally requires that

the report is submitted

by the ultimate parent

entity, or specified

surrogate entity, to that

entity’s tax jurisdiction.

In exceptional

circumstances it may be

required to be

submitted by the local

taxpayer.

Yes

Yes

Questionnaires

Local

Local entity

Generally, no,

but depends on

how framed

No

Further

information,

data and

documents

Local

Local entity

Generally, yes

No

11

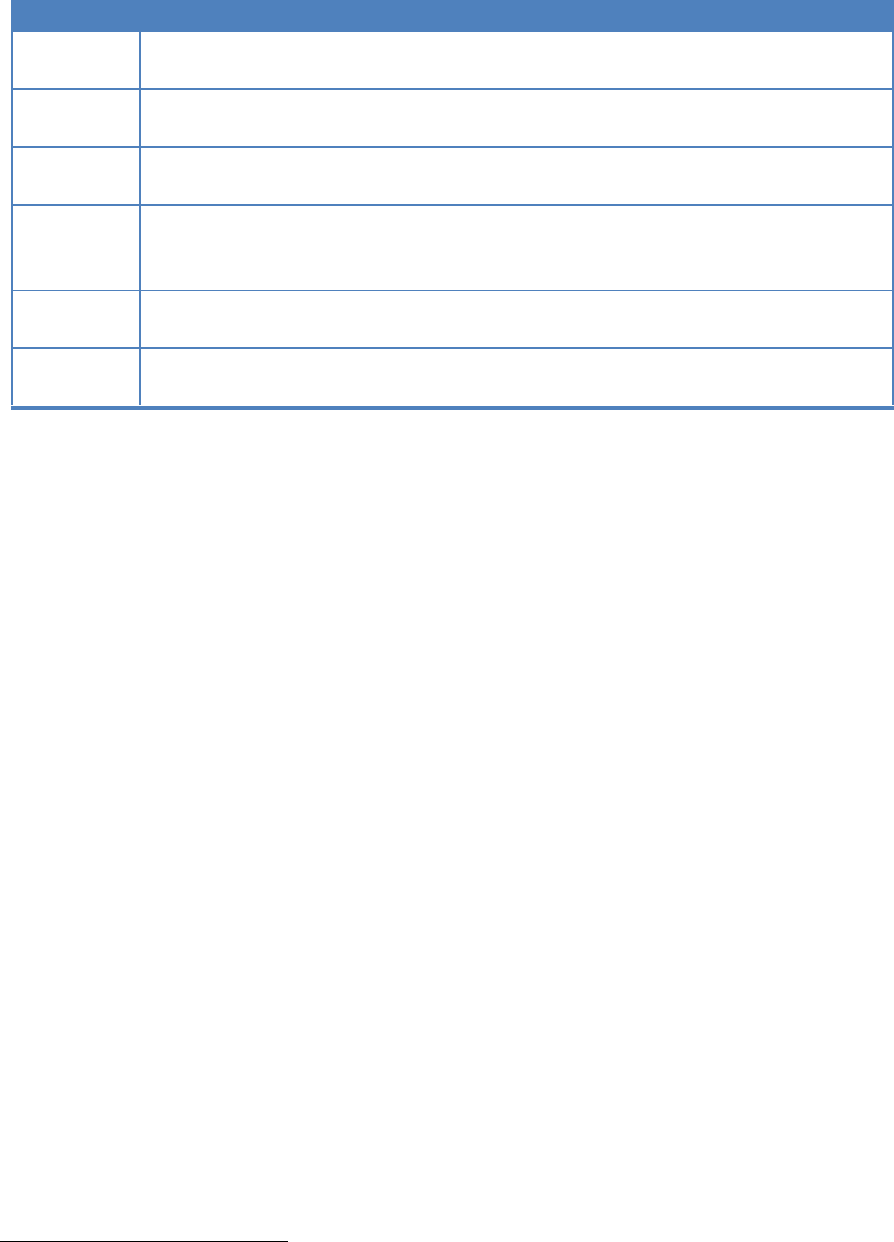

The following table summarizes the different practices of a number of countries:

Table 2 : Country practices on transfer pricing documentation requirements

Local file or

similar

transfer

pricing

study

Master

file

CbC

Report

Transfer

pricing

return

Questions

in Tax

Returns

Questionnaires

or ad-hoc

requests

Argentina

Australia

1/

Austria

Canada

2/

Colombia

Czech Republic

Dominican Republic

Finland

Georgia

Latvia

Liberia

Lithuania

Mexico

Netherlands

Nigeria

Peru

3/

Spain

Slovak Republic

Turkey

United States

4/

Uruguay

Vietnam

1/

The preparation of transfer pricing documentation is not compulsory, but taxpayers are recommended to do so

(with details of comparables and transfer pricing polices) to defend their position and to mitigate any administrative

penalties that may apply in the event the tax authority amends an assessment. Australia has an International

Dealings Schedule which includes questions on transfer pricing. It is not exclusively a transfer pricing return, but it

is a compulsory disclosure form that must be filed with the tax return. Questionnaires or other ad hoc requests for

information may arise during the course of an examination.

2/

Canada has legislation in place for something similar to the local file – it is referred to as “contemporaneous

documentation” and it has been in place since 1999 (see Annex 2). With respect to the master file, Canada can

request a master file from a Canadian taxpayer based on certain provisions in their law.

3/ The master file and the local file constitute compulsory returns, which must be submitted electronically annually.

4/

The general documentation requirements under United State law are not legally mandated, but as a practical

matter are voluntarily followed by taxpayers in the vast majority of cases because voluntary compliance is a

prerequisite for penalty protection.

12

It can be seen that there is no single approach to transfer pricing documentation

requirements, or combination of approaches, that is universally adopted. Furthermore, other

than for CbC reporting (which is a BEPS minimum standard) there is no internationally agreed form

and format of documentation. The OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines,

6

the UN Practical Manual on

Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries

7

(UN Transfer Pricing Manual) and the World Bank

Transfer Pricing Handbook for Policy Makers and Practitioners

8

provide guidance at the level of

general principles, including specifying the types of information to be included in the

documentation, but do not attempt to prescribe documentation requirements in detail. Rather than

reproducing such guidance, this toolkit aims to help translate those principles into practically

administrable transfer pricing documentation regimes. See Part III.

1.4 Context and background of transfer pricing documentation

requirements

Guidance on transfer pricing documentation was first included in the OECD Transfer Pricing

Guidelines in 1995, following the introduction of documentation requirements in the United

States one year earlier. Since then, an increasing number of countries have adopted documentation

requirements (see Figure 1, above).

The proliferation of individual country documentation regimes resulted in a wide range of

differing requirements around the world, contributing to an increased compliance burden

for multinational enterprises. In response to this, a number of initiatives to coordinate country

transfer pricing documentation requirements have been undertaken, for instance by the Pacific

Association of Tax Administrators

9

in 2003, within the European Union

10

in 2006, and finally as part

of the OECD/G20 BEPS project in 2015.

The BEPS Action 13 Report required the development of transfer pricing documentation

rules that enhanced transparency for tax administrations while taking into consideration the

compliance costs for business.

11

As a result, a three-tiered, standardized approach, comprising a

local file, master file and, for large MNEs with world-wide group turnover of EUR 750 million or

6

See OECD (2017), “Documentation”, Chapter V in OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises

and Tax Administrations 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/tpg-2017-en.

7

See UN (2017), “Documentation”, Section C.2 in Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries

2017, UN Publishing, New York, http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Manual-TP-2017.pdf.

8

Cooper, Joel, Randall Fox, Jan Loeprick, and Komal Mohindra. 2016

9

The Pacific Association of Tax Administrators (Australia, Canada, Japan and the United States) released

documentation principles to assist taxpayers in creating one set of documentation which would satisfy the

requirements of each of the PATA member countries. While application of the PATA requirements was voluntary

for taxpayers, the package included an exhaustive list of documents which was more comprehensive than the

requirements of any one of the member countries.

10

The EU Code of Conduct on Transfer Pricing Documentation for Associated Enterprises in the European Union,

agreed by the Council of the EU in June 2006, consisted of a common master file relevant to all EU group members

of a multinational enterprise (and had to be provided to all relevant EU member states), as well as standardised

country-specific documentation. Application of the Code of Conduct was optional for taxpayers.

11

See OECD (2013), “Action 13” in Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting 2013, OECD Publishing, Paris, p.

23, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264202719-en

13

more, the CbC Report was developed and then incorporated into the OECD Transfer Pricing

Guidelines. A similar approach is taken in the UN Transfer Pricing Manual.

As has been noted above, only the CbC Report is a BEPS minimum standard. The BEPS Action 13

Report acknowledges that the specific content of the CbC Report template was the subject of

compromise by participating countries and its implementation will be reviewed no later than the

end of 2020.

12

As part of this review, aspects related to the scope and content of the CbC Report

may be modified.

13

The outcomes of the 2020 review are expected to be released in 2021.

1.5 Objectives of transfer pricing documentation requirements

Fundamentally, transfer pricing documentation enables taxpayers to demonstrate their

compliance (or attempt of compliance) with transfer pricing rules.

The BEPS Action 13 Report identifies three main objectives of transfer pricing

documentation requirements:

→ To ensure that taxpayers give appropriate consideration to transfer pricing requirements in

establishing prices and other conditions for transactions between associated enterprises and in

reporting the income derived from such transactions in their tax returns.

→ To provide tax administrations with the information necessary to conduct an informed transfer

pricing risk assessment and selection of cases for audit.

→ To provide tax administrations with information necessary to conduct a transfer pricing audit of

entities subject to tax in their jurisdiction.

As part of the process of complying with reporting obligations, taxpayers may also be

incentivized to focus attention on their transfer pricing arrangements and their compliance

with transfer pricing rules. Through preparation of transfer pricing documentation taxpayers can

place themselves in a better position to defend their transfer pricing policies in the event of an

audit by the tax authorities.

For tax administrations, requirements for contemporaneous transfer pricing documentation will

help to ensure the integrity of the taxpayer’s position.

14

In summary, requiring enterprises to document their transfer pricing positions could be

expected to enhance compliance.

12

OECD (2015), Transfer Pricing Documentation and Country-by-Country Reporting, Action 13 - 2015 Final Report,

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD publishing, Paris, p.10,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264241480-en;

13

In February 2020 the Inclusive Framework released the public consultation document: Review of Country-by-

Country Reporting. The document requested comments on all aspects of the BEPS Action 13 report, but specifically

invited comments on a number of questions concerning the scope and content of the CbC Reports. See at

https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/public-consultation-document-review-country-by-country-reporting-beps-

action-13-march-2020.pdf

14

OECD (2017), Paragraph 5.7 in OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax

Administrations 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris.

14

While various types of documentation may serve a number of purposes, they generally

provide different types of information which can be particularly useful for different

purposes, for example:

→ For risk assessment purposes: Transfer pricing return schedules, CbC Reports and

questionnaires are primarily relevant for risk assessment purposes.

15

These tools can be

used in identifying taxpayers or transactions to be audited, or which may warrant further

investigation. They also provide auditors with early-stage indications of potential audit

issues.

→ For audit purposes: information contained in the local and the master files are a critical

source of information for tax auditors during an audit. They contain detailed information

needed by tax administrations to effectively verify whether the country’s transfer pricing

laws, including the arm’s length principle, are being complied with.

→ To encourage voluntary compliance: As noted above, all types of transfer pricing

documentation discussed in this Toolkit can also be expected to focus taxpayers’ attention

on their compliance responsibilities and thus enhance voluntary compliance.

1.6 Policy principles

Country requirements on the preparation and maintenance of transfer pricing

documentation should aim at the following objectives:

→ To be clear enough to provide some certainty to a taxpayer on how to demonstrate to the

tax administration that its transfer pricing is consistent with the country’s transfer pricing

rules.;

→ To provide the tax administration with the information they need in conducting risk

assessments, planning and conducting audits and testing the validity and reliability of the

transfer prices established by taxpayers;

16

and

→ To be balanced, so that reporting obligations fulfil tax administrations’ need for information

to be able to enforce the transfer pricing rules and at the same time avoid the imposition

of excessive documentation requirements on taxpayers. It is important that the costs to a

taxpayer of complying with these requirements are not disproportionately high relative to

the size and complexity of the controlled transactions in point, and the tax at risk. For this

reason, countries often provide exemptions or simplified documentation requirements for

smaller and low risk taxpayers or transactions.

15

Under the minimum standard in BEPS Action 13 Report, the CbC Report may be used only for risk assessment

purposes and for collection of data for statistical analyses.

16

Formal transfer pricing documentation may be supplemented by additional information requests made during

the course of an audit.

15

Ensuring international consistency

Both the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines and the UN Transfer Pricing Manual recognize

the advantages of consistent documentation rules to minimize transfer pricing compliance

burdens on taxpayers. International consistency and alignment of the content and format of

required documentation, for example, reduces the compliance costs of MNEs. This is particularly

relevant for the group level documentation referred to above. A standardized framework also

facilitates the sharing of experiences and good practices and it might also help to ease MAP APAs

and MAPs negotiations between countries.

As noted in the UN Transfer Pricing Manual, when considering the implementation of the BEPS

Action 13 documentation approach in developing economies, almost all MNE groups will likely be

required by at least one tax administration to prepare a master file; and MNE groups exceeding

the EUR 750 million annual global turnover threshold will also need to prepare a CbC Report.

Consequently, requiring these documents to be delivered to the local tax administration in a

developing country in a standard format should not impose disproportionate compliance burden

on a MNE group.

17

17

UN (2017), “Implementation of Global Documentation Standards in Developing Countries”, Paragraph C.2.2. 2.2

in Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries 2017, UN Publishing, New York.

16

PART II. OPTIONS FOR COUNTRIES TO IMPLEMENT

TRANSFER PRICING DOCUMENTATION

This section discusses various policy considerations and options relevant to designing a

regime for transfer pricing documentation. These include:

1. The regulatory framework, through a combination of primary legislation, secondary

legislation and guidance;

2. Confidentiality of taxpayers’ documentation and information;

3. Timing issues concerning when documentation must be in place and when it is required to

be submitted to the tax administration;

4. Enforcement, including penalties and measures to assist and promote voluntary

compliance;

5. Dealing with access to information outside the jurisdiction; and

6. Simplification and exemptions.

These are discussed in turn below.

2.1 Regulatory framework

2.1.1 General considerations

Developing a transfer pricing documentation regime raises a number of questions, which

concern not only the type and combination of documentation requirements to be introduced but

also the type and level of legal instruments introducing such requirements. The balance between

primary and secondary legislation varies between countries. For example, some countries include

detailed specifications on, for example, the format and content of documentation in their primary

law. Others include only a general provision in primary law and detailed specifications in secondary

law or regulations.

The choice of regulatory approach refers to the different levels of law that will apply in

practice to institute a legal obligation. These are:

• Primary law, consisting of statutes or legislation;

• Secondary law, consisting of regulations and procedures, executive orders and presidential

decrees, common law/case law, codes of conduct and policies;

• Supplementary guidance or statutory documents, including administrative procedures

such as ‘practice notes’ issued by the tax administration or Ministry of Finance;

Each of these elements fits into, or interacts with, the domestic legal system in different ways

depending on the country.

The starting point for all forms of transfer pricing documentation is a provision in the

primary law (e.g. tax code, tax statute or tax law), which may or may not be specific to transfer

pricing, and which is usually supplemented in secondary regulations.

17

In addition, countries often supplement these with administrative guidance. While such

guidance is not normally binding on taxpayers, it is in practice generally considered binding on the

tax administration. This means that care needs to be taken to ensure that guidance accords with

primary and secondary law, and government policy.

Countries follow different approaches when drafting legislation for transfer pricing

documentation requirements. Some countries adopt very brief language setting out the basic

principles in primary law and then elaborate those principles in secondary law and/or

supplementary guidance. In such cases, the primary legislation is typically intended to legislate

core taxpayer obligations and tax administration powers, which the secondary legislation builds on

with more comprehensive and detailed rules. Other countries have more extensive language in the

primary law leaving only few specific aspects for secondary law. In all cases, the primary law would

normally have a provision allowing the government, ministry or tax administration to introduce

and amend secondary law.

An advantage of establishing general principles in the primary law and more detailed specific

rules in subrogated or secondary law is the flexibility for future updates. Primary law usually

tends to be less flexible than secondary law and the process for its amendment requires more time

and approval steps from different government branches. By contrast, amendments to secondary

laws are usually primarily approved at government, ministry or tax administration level, and thus

offers greater flexibility.

It should be noted that the ability to receive CbC Reports filed with other tax jurisdictions

requires exchange of information instruments (e.g. treaties or membership of a multilateral

agreement), together with appropriate competent authority agreements, to be in place. (This is

discussed further in Section 3.4 below.)

2.1.2 Burden of proof

An important consideration for developing countries when devising transfer pricing regimes

is to define who bears the burden of proof. That is, who (either the taxpayer or the tax

administration) has to prove that the pricing is in accordance with the arm’s length principle.

Primary Legislation

Type: Laws (e.g. Corporate

Income Tax Act, Income Tax

Act, Tax Statute, Tax

Collection and Administration

Law)

Objective: establish the general

rules

Secondary Legislation

Types: Regulations and

Decrees

Objective: provide rules for the

implemetation and

interpretation of the tax

acts/laws

Supplementary Guidance

Type: Administrative

Procedures: Rulings, circulars,

instructions.

Objective: produce more

detailed rules for the

implementation and

interpretation of the primary

and secondary legislations

18

It is not always straightforward to determine how the burden of proof operates in different

jurisdictions and legal systems. It is often the case that when there is a self-assessment or similar

system requiring taxpayers to comply with the arm’s length principle, the burden of proof, in this

case that the measure of profit filed in a tax return accords with the arm’s length principle, is placed

on the taxpayer. In such cases, there should be a general provision requiring the taxpayer to keep

documentation to that effect in support of the tax return, and one of the purposes of such

documentation is to provide the taxpayer with the means of demonstrating that, in the taxpayer’s

opinion, it has made a correct return and fulfilled that burden. If the tax administration then

chooses to audit the tax return, in many instances, the burden of proof in relation to any adjustment

to profit is shifted to the tax administration. If the transfer pricing documentation fails to meet the

legal requirements, however, the tax administration may contend that the initial burden of proof

remains with the taxpayer. An example of an option to legislate this approach is illustrated in the

sample legislation at Annex 1.

In some countries however, the transfer pricing rules may be interpreted to allow the tax

administration to adjust taxable profit if needed to enforce the arm’s length principle, but

not to require the taxpayer to return an arm’s length measure of taxable profit

18

. In such cases, the

burden of proof lies with the tax administration and general documentation requirements within

the tax code may not apply to transfer pricing.

Where the tax administration holds the burden of proof and there are no, or only very

limited, requirements for taxpayers to provide transfer pricing documentation, a perverse

incentive can be created whereby taxpayers are effectively encouraged not to provide information

that would be needed by the tax administration to undertake and support a transfer pricing analysis

that could result in amendments to the taxpayer’s returns. In such cases, it is essential that adequate

penalty-backed information powers are in place to allow the tax administration to conduct a

comprehensive and effective audit.

According to country practices, the burden of proof:

• Could be defined in the law: this is generally contained in the primary law and applicable

in the ordinary course of the tax administration examination process, i.e. the provision is

not necessarily exclusive to transfer pricing. The stipulated burden of proof could be placed

on the taxpayer, the tax administration or split between them (See example on Spain

below).

• Could be placed on taxpayers, through the specific documentation requirements. It is

generally the case that when domestic legislation requires taxpayers to prepare, maintain

and/ or submit transfer pricing documentation the burden of proof lies with the taxpayer

(e.g. Argentina and Mexico).

Where the burden of proof lies with the taxpayer, it is helpful for countries to provide

guidance on how taxpayers should satisfy this requirement.

18

This is, the law may not be self-executing and while it may provide the tax administration with the power to make

an adjustment, it may not technically require anything of the taxpayer.

19

Box 1 : Example of countries’ provisions on the burden of proof

In Spain,

19

the tax law provides that:

1. In tax proceedings, the constituent facts of a right must be proved by the party seeking

to exercise that right.

2. The taxpayers will fulfil their duty of proof if they provide specific evidence to the tax

administration.

More specifically, specific transfer pricing provisions in Spain’s tax law states

20

that, in order to

justify that controlled transactions are valued according to the arm´s length principle, associated

entities should maintain at the disposal of the Tax Administration the transfer pricing

documentation. So, the burden of proof in relation to transfer pricing transactions is placed

primarily on taxpayers. However, if the Tax Administration disagrees with the valuation derived

from the documentation included in the tax return, the Tax Administration must prove its position.

2.2 Confidentiality

In most countries, taxpayer-specific information provided to the tax administration must,

by law, be kept confidential except where specifically provided for (e.g. specific disclosures,

disclosures to a court of law).

Confidentiality of taxpayer information is a fundamental tenet of most tax systems.

Confidentiality is likely to be a particularly important issue in relation to transfer pricing

documentation which may contain commercially sensitive material. In order to have confidence in

their tax system and comply with their obligations under the law, taxpayers need to have

confidence that such commercially sensitive information is not disclosed inappropriately. Ensuring

confidentiality of sensitive taxpayer information requires a legal framework as well as systems and

procedures to ensure that the legal framework is respected in practice and that there is no

unauthorized disclosure of information.

21

Confidentiality requirements would apply to transfer pricing documentation in the same way

that they apply to other information provided by a taxpayer to the tax administration, and

taxpayers should be assured that the information presented in transfer pricing documentation will

remain confidential, except as may be provided for by law. Further, confidentiality requirements

specified in BEPS Action 13 Report relating to CbC Reports form an element of the BEPS minimum

19

“Ley 58/2003 General Tributaria” [General Tax Law], Article 105. At: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-

A-2003-23186

20

“Ley 27/2014, de 27 de noviembre, del Impuesto sobre Sociedades” [Corporate Income Tax Law], Article 18.3. At:

https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2014-12328

21

OECD (2012), Keeping It Safe: The OECD Guide on the Protection of Confidentiality of Information Exchanged for

Tax Purposes, OECD, Paris. http://www.oecd.org/ctp/exchange-of-tax-information/keeping-it-safe.htm

20

standards, which are subject to peer review under the BEPS Inclusive Framework process. (This is

discussed further in Section 3.4 below).

Section D.8 of the BEPS Action 13 Report encourages tax administrations to take all

reasonable steps to ensure that there is no public disclosure of confidential information

(trade secrets, scientific secrets, etc.) and other commercially sensitive information that will be part

of transfer pricing documentation. A relatively small number of countries including Australia

22

,

Finland, Norway and Sweden provide for public disclosure of certain tax return data in relation to

(large) corporations. In most cases, only high-level tax data is made available, e.g. total taxable

income and taxes paid, rather than detailed disclosures or breakdowns of income and expenses.

Many civil society organizations (NGOs) and political observers have called for public disclosure of

CbC Reports. The issue of public disclosure was addressed, and broadly rejected, in the final report

of BEPS Action 13.

The European Commission’s current proposal for a directive on corporate tax transparency, if

agreed, would require MNE groups to publish a yearly report on profits and tax paid in each country

where they are active in a business register.

23

2.3 Timing Issues

A number of timing issues arise in the context of transfer pricing documentation regimes:

• When the taxpayer is required to have specified information in place;

• When the taxpayer is required to submit specified information to the tax administration;

• The length of time that records need to be kept.

Country information requirements - and associated penalty provisions - need to be tailored

to domestic rules concerning time limits for, for example, conducting an audit. Some countries

may have less time to review transfer pricing documentation, perform risk assessment and

complete an audit and, therefore, would need information to be provided within a shorter

timeframe.

Timing and submission requirements may vary depending on the type of documentation,

reflecting their different purposes. For instance, high level information for risk assessment would

be most useful if filed regularly; other, more detailed information may be best kept by the taxpayer

and made available on request. Typical scenarios are summarized below. The next section discusses

in more detail these options for each type of transfer pricing documentation, i.e. master file, local

file, CbC Report, transfer pricing returns and transfer pricing questionnaires.

22

Australia requires the disclosure of total income, taxable income and income tax payable amounts for large

corporate entities that meet the eligibility criteria. This requirement is enshrined in legislation.

23

This proposal (commonly known as Public country-by-country reporting), should be distinguished from the

existing and adopted Council Directive (EU) 2016/881 that requires the MNEs with more than EUR 750 million

consolidated group revenue per fiscal year that are either established or with a permanent establishment in any of

the EU Member States to file a CbC Report to the tax authorities of a given Member State.

21

Table 3 : Timing and submission of transfer pricing documentation

Type of

Documentation

When taxpayer is

required to have in

place

When the tax

administration may

request

When taxpayer is

required to submit to

the tax administration

Transfer

pricing annual

returns or

schedules

Normally by time of

filing annual tax

returns.

N/A – normally

required by specified

filing date.

Normally required to be

submitted with, or as part

of, the annual tax return.

Local file

Either

contemporaneous to

the transaction or

time of filing return

or combination.

At any time after filing

tax return, typically

during an audit. In

some cases, the local

file must be submitted

annually to the tax

administration.

Within a specified time

following request, or in

some cases, submitted

with, or as part of, the

annual tax return.

Master file

Either

contemporaneous to

the transaction or

time of filing or

combination

1/

.

At any time after filing

tax return, typically

during an audit. In

some cases, the master

file must be submitted

annually to the tax

administration.

Within a specified time

following request, or in

some cases, submitted

with, or as part of, the

annual tax return.

CbC Reports

By filing date.

N/A – normally

required by a specified

filing date.

Normally specified filing

date.

Questionnaires

N/A

At any time after filing

tax return, typically

during an audit.

As requested by the tax

administration or at a

time agreed upon with

the taxpayer. (Such

requirements are often

informal).

Further

information,

data and

documents

Depends on

legislation relating to

information powers.

Normally at any time

during the course of an

audit.

Within a specified time

following request.

1/

some countries allow local subsidiary entities to lodge the master file in line with the fiscal year of their foreign

parent / filing entity of the group. See discussion in Section 3.3.

2.4 Penalties and compliance incentives

As transfer pricing documentation is vital for the enforcement of transfer pricing rules,

effective penalties are essential. Some penalties may be applied for failing to provide required

documentation, others may be tied to transfer pricing adjustments and, in other cases, failure to

fulfil documentation requirements may lead to a higher penalty in relation to a transfer pricing

22

adjustment. Generally, omissions and misinformation should be subject to penalties and the

penalty should be sufficient to dissuade taxpayers from not complying with their obligations.

A penalty should be proportionate to the gravity of the infringement, for instance, by taking into

account the level of culpability of the taxpayer and the level of harm, including tax lost, caused by

the non-compliance. Penalties should allow for mitigating circumstances.

A summary of approaches to penalties on transfer pricing documentation is shown in Table 4.

24

These are discussed further in Part III.

Penalties relating to transfer pricing documentation may rely on a specific regime or on

general documentation or record keeping rules that are not specific to transfer pricing. In

the latter case, the general rules are most likely to be found in the primary legislation, and then

elaborated for transfer pricing purposes in regulations or guidance.

Table 4 : Penalty and compliance incentive approaches

Type of

Documentation

Penalty conditions

Possible approaches to

penalty

Based on specific

or general penalty

provisions

Transfer

pricing annual

returns or

schedules

a) Failure to file a return

by a required date.

b) Submission of an

incomplete return.

c) Making an incorrect

return.

For a) and b) a penalty

may be determined

according to the delay in

filing a complete return,

computed by reference

to a sum per day

between a) the due date

and b) the submission of

a complete return.

For c) a penalty may be

based on a fixed sum,

and/or the amount of

any subsequent

adjustment to taxable

income or tax payable.

In cases where the

transfer pricing

return is part of the

annual tax return,

the penalty may be

linked to that in

place for failure to

file a return or a

complete return, or

for filing an

incorrect return.

In other cases, a

specific penalty

may be required.

24

For further discussion on policy design of penalties see Waerzeggers, Christophe, Cory Hillier, and Irving Aw,

2019, “Designing Interest and Tax Penalty Regimes”, Tax Law IMF Technical Note 1/2019, IMF Legal Department

23

Transfer

pricing studies

(master file or

local file)

a) Failure to maintain

adequate documentation

at a specified date.

b) Failure to submit

adequate documentation

upon request or by a

specified date.

c) Submission of incorrect

documentation.

Penalties may be:

i. a fixed sum

ii. based on any

subsequent adjustment

to taxable income

iii. based on any

subsequent adjustment

to tax payable.

Alternatively, for b) the

penalty may be

determined according to

the delay in making a

complete submission,

computed by reference

to a sum per day

between a) the due date

for submission and b) the

submission of a complete

transfer pricing study.

The penalty may be

based on either a

general penalty

regime, or specific

penalty provisions

contained in the

transfer pricing

rules.

CbC Reports

a) Penalty for failure to

submit a complete CbC

Report by a specified

date.

b) Penalty for making an

incorrect CbC Report.

For a) penalty may be

determined according to

the delay in making a

complete submission,

computed by reference

to a sum per day

between (i) the due date

for submission and (ii)

the submission of a

complete CbC Report.

For b) a penalty may be

based on a fixed sum,

and/or on the value of

the consolidated MNE

revenue.

In both cases, the

penalty may be

based on either a

general penalty

regime, or specific

penalty provisions

contained in the

transfer pricing

rules.

Questionnaires

In most cases, a questionnaire will be non-statutory, and thus may not be

subject to penalties. Some questionnaires will be purely of an advisory nature

and/or used for risk assessment. However, a failure to comply with valid

requests for information during an audit may impact on penalties which are

applied to transfer pricing adjustments, which may take account of, for

example, whether the taxpayer will be regarded as having co-operated or

obstructed the tax administration, or whether the taxpayer’s position is

assessed as being ‘reasonably arguable’.

Further

information,

data and

documents

a) Penalty for failure to

submit complete

information by the due

date.

For a) a penalty may be

determined according to

the delay in making a

complete submission,

computed by reference

In both cases, the

penalty is most

likely to be based

on either a general

penalty regime, or

24

requested

during an audit

b) Penalty for supplying

incorrect information

to a sum per day

between (i) the due date

for submission and (ii)

the submission of

complete information as

requested.

For b) a penalty may be

based on a fixed sum,

and/or the amount of

any subsequent

adjustment to taxable

income or tax payable.

specific penalty

provisions

contained in the

transfer pricing

rules.

Relationship with burden of proof

Another way to encourage taxpayers to fulfil transfer pricing documentation requirements

is to design compliance incentives in the form of a shift in the burden of proof. In this case,

where the initial burden of proof lies with a taxpayer, it may be shifted to the tax administration if

the taxpayer complies with the transfer pricing documentation requirements. This approach, which

is illustrated in Paragraph 3 of the illustrative transfer pricing documentation legislation in Annex

1, is most appropriate in respect of contemporaneous transfer pricing studies such as a the local

and master file.

Likewise, where the initial burden of proof may be with the tax authorities, a failure to adhere to

transfer pricing documentation requirements may lead to shifting the burden of proof to the

taxpayer.

2.5 Accessing documents held outside the jurisdiction

Some countries report that MNE group subsidiaries or permanent establishments in their

jurisdiction sometimes contend that they do not have access to information held by the

group outside the jurisdiction. As a result, they argue that they are unable to make certain

information available to the tax administration. This issue will involve information held by foreign

parent, head office or sister companies. It should not affect information held by foreign subsidiaries

of a locally headquartered company – in such cases, the local company will normally have the

power to require its subsidiaries or branches to submit information and data to them.

This issue potentially affects the different categories of documentation to different extents.

1. Transfer pricing studies

25

and transfer pricing return schedules are required to be

submitted under domestic rules and, typically, penalties will apply for a failure to submit them.

Despite this, developing countries report that MNEs exceptionally contend that they do not have

access to sufficient information to be able to submit complete schedules or transfer pricing studies.

For those countries that adopt the BEPS Action 13 approach to transfer pricing documentation, the

25

The term transfer pricing study includes the ‘local file’ and the ‘master file’ described in the BEPS Action 13 Report.

25

issue is likely to affect the master file (which provides a global analysis, and will normally be

prepared by the ultimate parent entity (UPE)) more so than the local file (which provides an analysis

of intercompany transactions affecting the domestic taxpayer).

Such contentions should be resisted:

- The information required in these types of documentation is necessary in order to establish

that the price and other conditions of transactions within the scope of the transfer pricing

rules have been determined in accordance with the arm’s length principle. If the local entity

does not have access to this information, then it follows that said entity has not been able

to establish the arm’s length nature of transfer prices applied and thus that it has made a

correct tax return in accordance with the domestic rules.

- MNE groups are increasingly integrated organizations, with regional or global

management structures and supply chains. This means that it is increasingly unlikely that

local entities will be denied access to information concerning the wider operations.

It is important that penalties for failure to provide this information are sufficiently robust, and

effectively applied, to ensure that such information is submitted locally. An additional option may

be to apply measures such as those described in Section 3.3.5 (1), which involves shifting the

burden of proof to the taxpayer.

2. In the cases where CbC Reports are required to be filed locally, as described in Section

3.4.2, the local entity could contend that it does not have access to the report. Therefore, it

will be important that penalties for failure to provide the report are sufficiently robust and

effectively applied to ensure that they are submitted locally.

3. A request to foreign affiliates of the local taxpayer to return questionnaires will often

be informal and unenforceable in law. In such cases, there will be little scope for the tax

administration to enforce submission. In some countries, the law may provide that where a taxpayer

has not provided such information when requested, they cannot later rely on the same information

in a court of law. Where the tax administration is unable to compel a taxpayer to provide such

information, a request under exchange of information provisions may be possible. This will depend,

however, on whether the information requested falls within the scope of exchange of information

provisions.

26

4. Information required by auditors during the course of an audit may include

information that can legitimately be contended by the tax administration should be

available, or made available, to the local entity. However, there may also be information that is

26

Article 26.1 of the OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital as well as Article 26.1 of the UN Model

Double Taxation Convention between Developing and Developed Countries allow exchange of information that is

‘foreseeably relevant for carrying out the provisions of this Convention or to the administration or enforcement of

domestic laws concerning taxes of every kind…’

See also Chapter III, Section I, on Exchange of Information in OECD/Council of Europe (2011), The Multilateral

Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters: Amended by the 2010 Protocol, OECD Publishing,

Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264115606-en.

26

genuinely not available to a local entity – for example submissions made by a foreign related entity

to its tax administration. In such cases, exchange of information processes may be appropriate.

27

It is further noted that tax authorities should request only information that is relevant and

reasonable.

2.6 Simplification and exemptions.

The costs of compliance with transfer pricing rules can be very significant for taxpayers. It is

important that measures are taken to avoid unnecessary or disproportionally high compliance

costs when designing a transfer pricing documentation regime. This is recognized in the UN

Transfer Pricing Manual, in relation particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that

engage in cross-border related transactions.

28

Many countries address this concern by simplifying

the transfer pricing documentation rules for smaller or lower risk taxpayers (e.g. entities with only

limited related party transactions). Alternatively, countries may exempt such taxpayers from the

documentation rules (but not transfer pricing rules). In such cases, the exemption would not cover

a requirement, under general information powers, to submit information about cross-border

transactions during the course of an audit. Approaches to this are summarized in the table below.

These are discussed further in Part III.

Table 5 : Simplification and exemptions

Type of Documentation

Possible simplification or exemption measures

Transfer pricing annual

returns or schedules

1. Exemption for smaller or low risk taxpayers

2. Simplified return schedule for smaller taxpayers

3. Exemptions from disclosure of transactions below a certain

value

Local file

1. Exemption for smaller or low risk taxpayers

2. Exemptions for taxpayers belonging to a group whose

consolidated turnover is less than a certain amount

3. Exemption for taxpayers within the scope of a safe harbour

or for transactions covered by an APA

4. Simplified documentation requirements for smaller

taxpayers

Master file

Exemption or simplification for taxpayers belonging to a group

whose consolidated turnover is less than a certain amount

CbC Reports

Exemption for MNE groups with a global consolidated revenue

of less than EUR 750 million

29

27

Again, the request must be within the scope of the exchange of information instrument. See Footnote 15, above.

28

See UN (2017), “Documentation”, Section C.2.4.4.1 in Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing

Countries 2017, UN Publishing, New York, http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Manual-TP-

2017.pdf.

29

This criterion is specified in BEPS Action 13, and forms part of the minimum standards on BEPS Action 13.

27

Questionnaires

As these are generally non-statutory, tax administrations may

choose to issue these to the larger or higher risk taxpayers

only

Further information, data

and documents

Such information is requested by the tax administration during

an audit – statutory exemptions are therefore not relevant

These measures require the term ‘smaller taxpayer’ or ‘low risk taxpayer’ to be defined. There are

several possibilities:

- Existing definitions of small or medium enterprises. Where such a definition is used,

exemptions may be denied to taxpayers undertaking higher risk transactions – for example

a taxpayer that conducts one or more transactions with an entity in a low tax jurisdiction;

- By reference to the value of the related party transactions. This may be problematic if the

taxpayer undervalues related party transactions;

- By reference to the proportion of the value of related party transactions to third party non-

related transactions. This may be problematic if the taxpayer undervalues related party

transactions;

- By exemption for purely domestic transactions between local related entities, where both

parties to the transactions are subject to the same taxation regime and rate of taxation.

Countries need to tailor definitions of ‘smaller taxpayer’ or ‘low risk taxpayer’ to the context of their

specific markets.

Where feasible, regional alignment of simplifications and exemptions might be considered. Such

consistency would help to prevent harmful tax competition between countries.

28

PART III. SPECIFIC DOCUMENTATION ELEMENTS

3.1 Introduction

This part will look in more detail at each of the categories of transfer pricing documentation

discussed in Part II, i.e. transfer pricing returns, transfer pricing studies (including the master and

local files described in the BEPS Action 13 Report), CbC Reports and questionnaires. It provides

some examples of country approaches.

3.2 Transfer pricing returns

A transfer pricing return is a specified set of information concerning transfer pricing that

affected taxpayers must periodically submit to the tax administration, typically annually.

This information may be submitted with the annual income tax return, or in a schedule generally

lodged at the same time as the return. The taxpayer is required to disclose, in a standardized

format, information relating to its transactions with related parties. This is in addition to other

transfer pricing documentation requirements.

A transfer pricing return contains information on related-party transactions. This generally

includes, at minimum, a list of related party transactions and the countries in which the

counterparties are resident.

3.2.1 Functions of transfer pricing returns

The transfer pricing return serves several purposes, including:

1. Risk assessment and case selection. The information it provides can be used to:

‒ Identify and analyze risks at a macro level. For example, risks arising from a category of

transactions or by sector;

‒ Identify taxpayers that present a high risk to the revenue, including as a part of an audit

case-selection process;

‒ Identify specific transactions to be followed up in the context of an audit.

A transfer pricing return is very unlikely to provide sufficient information to conduct an audit

and to decide on the arm’s length nature of transactions. It is normally viewed as a tool for use

in the first step of an audit process – the selection of cases for audit, and identification of specific

issues to follow up in an audit.

The information provided in transfer pricing returns is usually in a tabular format consisting

mainly of quantitative information, which may make it suitable to be prepared in electronic

format. Where a tax administration has the resources, electronic submission using automated

29

processes enables analysis of mass information using techniques such as data mining and data

matching.

30

2. Transfer pricing returns can promote positive MNE behavioral changes and assist in

the creation of a compliance culture. The requirement to submit data as part of, or as a

supplement to, a tax return, is likely to raise awareness of the need to consider transfer pricing and

focus attention on the responsibility to comply with transfer pricing rules.

In the design of this type of form, care should be taken not to request information that

would be overly burdensome for taxpayers by requiring more information than is needed

for risk assessment purposes, or information already in the possession of the tax administration

by other means. Simplicity, non-duplication and standardization might usefully be the governing

principles of disclosure forms and specific transfer pricing returns.

If disclosure forms are to be used, tax authorities may want to consider the extent to which

these can follow a consistent regional format. A regional approach may have the potential to

be beneficial to both taxpayers and tax administrations. These include:

a. The capacity to improve investment climate. Taxpayer compliance costs will be reduced

if countries apply similar formats in their documentation requirements.

b. Prevention of ‘tax competition’. A non-aligned application of transfer pricing rules has

the potential to create tax competition between countries. For example, non-application,