MONETARY POLICY IN A NEW ERA

Ben S. Bernanke

Brookings Institution

October 2, 2017

Prepared for conference on Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy, Peterson Institute, Washington

DC, October 12-13, 2017. The author is a Distinguished Fellow at the Brookings Institution and

the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy. I thank Olivier Blanchard, Donald Kohn,

and David Wessel for comments and Michael Ng for excellent research assistance.

1

In 2017, the flagship research conferences of the European Central Bank and the Federal

Reserve—held in Sintra, Portugal, and Jackson Hole, Wyoming, respectively—had something in

common: Both had official themes unrelated to monetary policy, or even central banking. The

ECB conference (theme: Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies) did include an

opening speech by President Mario Draghi on monetary policy and the outlook, before turning to

issues like the prospective effects of technological advances on employment. However, the

Fed’s meeting (theme: Fostering a Dynamic Global Economy), which included papers on topics

ranging from fiscal policy to trade to income distribution, made almost no mention of monetary

policy. Whether intended or not, the signal, I think, was clear. After ten years of concerted

effort first to restore financial stability, then to achieve economic recovery through dramatic

monetary interventions, central bankers in Europe and the United States believe that they see the

light at the end of the tunnel. They are looking forward to an era of relative financial and

economic stability in which the pressing economic issues will relate to growth, globalization, and

distribution—issues that are the responsibility of other policymakers and not primarily the

province of central bankers.

Would that it were so simple. Although central bankers can certainly hope that the next

ten years will be less dramatic and demanding than the past ten, there will certainly be important

new challenges to be met. In this note, I focus selectively on two such challenges: the

implications of the secular decline in nominal interest rates for the tools and framework of

monetary policy; and the status of central banks within the government, in particular, the

questions of whether central banks should and will retain their current independence in making

monetary policy. As I will explain, the two challenges are related, in that the low-inflation, low-

interest-rate environment in which we now live calls into question some of the traditional

rationales for central bank independence.

The long-term decline in nominal interest rates is well known and has been extensively

studied (Rachel et al., 2015). The decline appears to be the product of many causes, including

lower inflation rates; aging populations in advanced economies (Gagnon et al., 2016a); slower

productivity growth and “secular stagnation” (Summers, 2015); global patterns of saving and

investment (Bernanke, 2005); and increased demand for “safe” assets (Del Negro et al., 2017;

Caballero et al., 2017). Some of these factors may reverse in the medium term—for example,

2

recent historically low rates of productivity growth could revert to more-normal levels (Byrne

and Sichel, 2017), and there is some evidence that the global savings glut may be moderating

(Chinn, 2017)—which could lead to somewhat higher rates in the future. For now, though, the

combination of low nominal rates and the difficulty of reducing short-term interest rates (much)

below zero implies that monetary policymakers may have limited scope to address deep

economic slowdowns through the traditional means of cutting short-term interest rates. Recent

research by Kiley and Roberts (2017) illustrates the potential severity of the problem. Based on

simulations of econometric models, including the Fed’s main model for forecasting and policy

analysis, these authors show that the use of conventional, pre-crisis policy approaches could lead

to policy rates being constrained by the zero lower bound (ZLB) as much as one-third of the

time, with adverse effects on the Fed’s ability to hit its 2 percent inflation target or to keep output

near potential.

1

How should central banks respond? Outside of making a stronger case for proactive

fiscal policies, there are two broad possibilities (interrelated and not mutually exclusive). First,

rather than relying on the management of short-term interest rates alone, as assumed by Kiley

and Roberts, monetary policymakers could make greater use of new tools developed in recent

years. In the first main section of this paper, I review some of these tools. I argue that both

forward guidance and quantitative easing are potentially effective supplements to conventional

rate cuts, and that concerns about adverse side effects (particularly in the case of quantitative

easing) are overstated. These two tools can thus serve to ease the ZLB constraint in the future, as

argued by Yellen (2016). Two other tools—negative interest rates and yield curve control—are

less likely to play important roles, at least in the United States. European and Japanese

policymakers have successfully employed negative rates, but overall they appear to have

relatively modest benefits (because the option to hold cash limits how far negative rates can go),

as well as some offsetting costs (related to their effects on certain financial institutions and

markets). Yield curve control, or the direct management of longer-term interest rates, has been

adopted by the Bank of Japan and makes sense in the current Japanese context. However, as I

1

As some major central banks have employed modestly negative rates, conventional usage now often refers to the

“effective lower bound” (ELB) on interest rates rather than the ZLB. The Federal Reserve has not used negative

rates, however. Since I am focusing on the Fed here, for simplicity I’ll stick with the ZLB acronym.

3

will discuss, the depth and liquidity of the markets for U.S. government securities would make it

difficult for the Fed to peg rates beyond a horizon of two years or so.

Although unconventional tools can increase the potency of monetary policy, the ZLB is

still likely to be a binding constraint on the monetary response to a downturn that is more

serious, or which occurs when rates remain (like today) below neutral levels. A second broad

response to the problem is to modify the overall policy framework, with the goal of enhancing

monetary policymakers’ ability to deal with such situations (Williams, 2017). Focusing on the

case of the Federal Reserve, in the second principal section of the paper I briefly consider two

proposed alternatives: (1) raising the Fed’s inflation target from its current level of 2 percent,

and (2) introducing a price-level target. I argue that a higher inflation target has a number of

important drawbacks: It would, obviously, lead to higher average inflation (possibly inconsistent

with the Fed’s mandate for price stability); and, more subtly, it implies a Fed reaction function

that theoretical analyses suggest is quite far from the optimal response. A price-level target

performs better on both counts, as 1) it is fully consistent with the goal of price stability, perhaps

even more so than an inflation target; and 2) it implies a “lower-for-longer” response to periods

when rates are at their ZLB, which approximates what theory tells us is the optimal approach.

However, a price-level target can be problematic in the face of supply shocks, and the switch to a

price-level target from the current inflation targeting approach would be a significant

communications challenge. In the latter part of the section, I propose and discuss a third possible

alternative: a “temporary price-level target” that kicks in only during periods in which rates are

constrained by the ZLB. I argue that the adoption of a temporary price-level target would be

likely to improve economic performance, relative to the current framework. Importantly, it

would do that while both maintaining price stability and requiring only a relatively modest shift

in the Fed’s framework and communication policies. However, this proposal is a tentative one at

this stage, and more analysis would be needed before taking it further.

Beyond the problems arising from low nominal interest rates, monetary policymakers

also face challenges to central bank independence (CBI). The challenge to CBI has been

heightened by the political blowback that followed the financial crisis. But, as already noted,

questions about CBI are also related to the change in the macroeconomic and interest-rate

environment, linking this issue to the themes of the first part of the paper. In the United States,

the doctrine of CBI emerged, in part, from the inflationary experience of the 1960s and 1970s,

4

which was blamed in part on undue political influence on monetary policymakers. Following

these events, both formal models and informal conventional wisdom held that, to avoid pressures

to overheat the economy and allow higher inflation, the Fed needed greater independence from

politics. However, the inflation-centric rationale for CBI looks a bit outdated in a world in which

inflation and nominal interest rates are too low, rather than too high; and in which politicians

have criticized central banks for being too expansionary rather than not expansionary enough.

Indeed, the same logic that holds that CBI is necessary to avoid excess inflation can be turned on

its head, to imply that CBI is a barrier to the fiscal-monetary coordination needed to combat

deflation (Eggertsson, 2013).

The last principal section of the paper briefly takes up these issues. I argue that the case

for CBI has always been broader than the anti-inflationist argument, and that CBI should remain

in place in the new economic environment. At the same time, I contend that the case for CBI is

instrumental, that it depends on costs and benefits rather than on philosophical principles, so that

the limits of independence appropriately depend on the sphere of activity under consideration

and on economic conditions. The general principle of CBI thus does not preclude coordination

of central bank policies with other parts of the government in certain situations.

DEFEATING THE ZLB: UNCONVENTIONAL POLICY TOOLS

Central bankers in 2008 faced extraordinarily difficult challenges, in particular the

combination of a deep recession—which made a sharp easing of monetary conditions

necessary—and the proximity of short-term interest rates to zero, which made easing difficult.

In response, monetary policymakers employed a number of unconventional policy measures.

Which ones will become part of the standard toolbox? In what order or combination might the

various tools of monetary policy be used in the future? In this section, I comment on these

issues. I take as given that management of a short-term policy rate (e.g., the federal funds rate in

the United States) will remain the primary tool, so long as the ZLB is not binding. I won’t have

much to say about the technicalities of monetary policy implementation (e.g., the distinction

between a “floor” and “corridor” system for managing short-term rates), although

unconventional policies (such as quantitative easing) can at times complicate implementation. I

discuss, sequentially, forward guidance, quantitative easing, negative rates, and yield curve

control (the management of longer-term yields).

5

Forward guidance

The non-standard tool on which central bankers are most likely to rely in the next easing

cycle is forward guidance, or communication about the expected or intended future path of the

policy rate. The Fed used variants of forward guidance in the Greenspan era, for example, in

references to keeping rates low for “a considerable period” (Federal Open Market Committee,

2003). Even earlier, a number of central banks experimented with forward-looking policy

commitments, a notable case being the Bank of Japan’s zero-interest-rate policy (ZIRP), in

which the BOJ said that it would not lift rates from zero until certain conditions had been met

(Bank of Japan, 1999). The prices of longer-term financial assets (including those most closely

tied to economic activity, such as corporate bonds, mortgages, and stocks) depend on not only

the current setting of the policy rate but on its entire expected future path. Consequently, central

bank “open-mouth operations” that influence market expectations of future policies can affect

financial conditions today, even if the short-term policy rate is close to its effective lower bound

(Guthrie and Wright, 2000).

Forward guidance comes in a number of forms. A useful distinction is between Delphic

and Odyssean forward guidance (Campbell et al., 2012). Delphic guidance is a simple statement

of how monetary policymakers see the economy and interest rates as likely to evolve. Delphic

guidance is advisory only and makes no promises about future policy. In contrast, Odyssean

guidance—the phrase is motivated by Odysseus’s decision to tie himself to the mast to be able to

resist the calls of the Sirens—is intended to pre-commit the central bank to some (possibly

contingent) set of future policies.

The goals of Delphic and Odyssean guidance are different. Delphic guidance—as for

example seen in the Fed’s famous “dot plot,” which shows the interest-rate forecasts of

individual FOMC participants—is designed primarily to help the public and market participants

understand the committee’s outlook, reaction function, and policy plans. More informally,

central bankers’ public remarks about the likely course of the economy and policy are usually

Delphic in intent. Increasingly, central banks are incorporating Delphic guidance into their

communication strategy during normal times; this development primarily reflects trends to

increased transparency by central banks, rather than the emergence of the ZLB as an important

6

policy constraint. By improving the clarity of the central bank communication, Delphic

guidance is intended to increase the predictability of monetary policy and make it more effective.

Odyssean guidance, in contrast, is most likely to be relevant when the policy rate is at or

close to the ZLB, so that the scope for short-term rate cuts is limited. Typically, monetary

policymakers use Odyssean guidance to communicate a promise to keep rates lower for longer

than implied by their “normal” reaction function. If the promise is credible, then market

participants should bid down longer-term yields and bid up asset prices today, effectively adding

stimulus despite the ZLB constraint. The key word here is “commitment.” If prior commitment

were impossible, for the reasons explored in the time-consistency literature (Kydland and

Prescott, 1977), then Odyssean forward guidance could not materially change market

expectations and would consequently be useless. In practice, central bank guidance does appear

to have significant effects on asset prices (Campbell et al., 2012; Swanson, 2017) and thus,

presumably, on the economy. Central bankers’ concerns for their own reputations and those of

their institutions, as well as the tendency of market participants to look for focal points around

which expectations can coalesce, appear in practice to provide monetary policymakers some

ability to commit to future policy actions.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the Fed’s policymaking body, provided

regular forward guidance during the recovery from the crisis. Some controversy has arisen about

the FOMC’s approach. Michael Woodford (2009) and others have argued that the FOMC

inappropriately used Delphic rather than Odyssean formulations in its guidance, limiting its

benefit. For example, at the same meeting at which the policy rate was cut effectively to zero,

the December 2008 FOMC statement indicated, “…the Committee anticipates that weak

economic conditions are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for

some time” (FOMC, 2008). By speaking of “anticipating” or “expecting” rates to remain low,

rather than using stronger language of commitment or intention, Woodford argues, the FOMC

created less stimulus than it might have. Indeed, by signaling pessimism about the outlook, the

FOMC’s guidance (in Woodford’s view) might have been counterproductive.

Woodford is right in principle, and all else equal, a policy committee whose intent is to

provide Odyssean guidance should try to make its commitments as clear and as nearly ironclad

as possible. A real-world complication is that policy committees are not typically unitary actors,

but may include participants of diverse views, trying to reach compromise in an uncertain

7

environment. Some hedging or ambiguity in the committee’s official statements may therefore

be difficult to avoid. In practice, however, the FOMC’s guidance after the crisis—as mediated

by the public comments of policymakers—did seem to have Odyssean effects. Notably, the

Fed’s introduction of forward guidance was typically followed by changes in longer-term interest

rates, exchange rates, and equity prices consistent with substantial increases in monetary

accommodation (Femia et al., 2013; Swanson, 2017) and by reduced sensitivity of near-term rate

expectations to economic news (Williams, 2014). The increases in equity prices in particular

suggested that markets were focused on the FOMC’s signal of greater policy patience (the

Odyssean aspect) rather than on an indication of greater pessimism (Delphic). Moreover,

professional forecasters reacted to FOMC guidance by repeatedly marking down the

unemployment rate they expected to prevail at the time that the Committee began to lift the funds

rate away from zero, implying a perceived shift in the Fed’s expected reaction function

(Bernanke, 2012; Femia et al., 2013). The apparent success of the FOMC’s guidance, developed

on the fly, is promising for the future use of verbal interventions. As both central bankers and

market participants gain experience with forward guidance, the tool should become increasingly

effective.

Another important distinction is between qualitative guidance (“considerable period”)

and quantitative guidance, for example, describing specific economic conditions that would lead

to a change in policy. Over the years, Fed guidance has evolved from qualitative towards

quantitative, reflecting the desire to enhance transparency as well as the imperative of adding

substantial accommodation during the ZLB period. Economic logic suggests that quantitative

guidance will be more effective, because it is both more precise and more verifiable ex post (and

thus easier to support by reputational concerns). However, again, a policy committee may not

always be able to agree on quantitative guidance. It may also be the case that uncertainty about

the economic situation favors the relative ambiguity of a qualitative formulation, at least initially.

Experience suggest though that qualitative guidance, if maintained for a while, often morphs into

quantitative guidance, as market participants, legislative committees, and other stakeholders

press policymakers to clarify the meaning of key phrases.

Yet another dimension of forward guidance is time-dependency versus state-dependency.

The FOMC used both types after the crisis, indicating first that it expected to hold rates low

through a certain date, then tying rate increases to thresholds based on the prevailing

8

unemployment and inflation rates.

2

In principle, policy settings should depend on the state of the

economy, and so state-dependent guidance should be the default in the future (Feroli et al.,

2016).

3

As pointed out by Williams (2016) however, date-based guidance may at times be more

effective, perhaps because it is more definitive and more credible to market participants. A

particular situation in which date-based guidance might be desirable arises when policymakers

and the market have different economic outlooks. Suppose the ideal guidance would hold rates

at zero at least until unemployment fell to 6 percent; but suppose also that market participants

expect unemployment to reach 6 percent in one year while policymakers believe that

unemployment will decline more slowly, reaching 6 percent in two years. In that case, state-

dependent guidance would be insufficiently stimulative from the policymakers’ point of view,

and time-dependent guidance (a promise that rates will remain low for two years) would achieve

a greater reduction in current long-term rates and be more consistent with the policymakers’

objectives.

I’ve been discussing forward guidance about rates, but guidance can be provided about

aspects of policy other than rates, notably, about plans for asset purchases. Such guidance is a

natural extension of rate guidance and can be Delphic or Odyssean in intent. The main point

here is that guidance about the components of policy needs to be carefully coordinated, so that

the planned sequencing of policy changes is clear. For example, the famous 2013 “taper

tantrum” followed Fed guidance that it anticipated reducing the pace of its asset purchases,

conditional on economic developments. However, the tantrum reflected not so much the

expectation of reduced asset purchases per se, but rather the inference in some quarters of the

market (as could be seen in futures quotes) that increases in short-term rates would quickly

follow the slowing of asset purchases. (See below for more on the “signaling” aspects of

quantitative easing.) Fed policymakers had communicated their intention to keep rates low for a

long time after the end of asset purchases, but evidently those promises had not sunk in, and

2

The FOMC experimented with three variations of qualitative forward guidance in December 2008, March 2009,

and November 2009. In August 2011, January 2012 and September 2012, the FOMC used different versions of

calendar-based forward guidance in which they set a date in which they would keep rates ‘exceptionally low’. In

December 2012 the FOMC switched to a state-dependent form of forward guidance in which they committed to

keeping interest rates ‘exceptionally low’ at least as long as the unemployment rate was above 6.5%, inflation was

below 2.5% based on one to two year ahead forecasts, and inflation expectations remained anchored.

3

In principle, optimal policy depends not only on the current state of the economy but on its history as well. I

discuss this point further below.

9

coordinated reiterations of the point had to be made before market expectations re-adjusted and

market conditions calmed.

A final observation on forward guidance: In this section I have been treating guidance,

particularly of the Odyssean variety, as an ad hoc intervention, a supplement to management of

the short-term rate. Alternatively, or in addition, the central bank could adopt an overarching

framework that implies systematic Odyssean responses to ZLB episodes. I’ll explore this

possibility below, in the section on policy frameworks.

Quantitative easing

Probably the most controversial form of unconventional policy adopted in recent years

was what the Federal Reserve called large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs) but most of the rest of

the world persisted in calling “quantitative easing”, or QE.

4

The Federal Reserve engaged in

three rounds of QE, during which its balance sheet expanded from less than a trillion dollars to

$4.5 trillion. The Bank of England, European Central Bank, Swedish Riksbank, and Bank of

Japan (which had pioneered asset purchases as a form of monetary policy well before the crisis)

have also undertaken quantitative easing.

Quantitative easing involves central bank purchases of securities in the open market,

financed by the creation of bank reserves held at the central bank. By law, the Fed was able to

purchase only Treasury securities and mortgage-related securities issued by government-

sponsored enterprises. Other central banks, in contrast, have been able to buy a range of private

securities, including corporate bonds and equities. The limits on the Fed did not seem to prevent

its version of QE from being effective, although it was perhaps fortunate that, following a crisis

centered on housing finance, the law did permit Fed purchases of mortgage-related securities.

Research suggests that QE works through two principal channels, the signaling channel

and the portfolio balance channel. The signaling channel arises to the extent that asset purchases

serve to demonstrate the central bank’s commitment to monetary easing, and in particular to

keeping short-term rates lower for longer (Bauer and Rudebusch, 2013). As discussed above, the

so-called taper tantrum in 2013 demonstrated the practical relevance of the signaling channel of

4

I also tried, without success, to name the program “credit easing,” to distinguish it from the Bank of Japan’s earlier

foray into asset purchases (Bernanke, 2009). I argued that “credit easing” focused on removing duration from bond

markets, in contrast to BOJ-style quantitative easing, which had the primary goal and metric of increasing the high-

powered money stock.

10

QE. As noted, because of the importance of the signaling channel, it is essential that asset

purchases and interest rate policy be closely integrated, and that in particular the central bank be

clear about its planned sequencing of the introduction and withdrawal of its various tools.

The portfolio balance channel depends on the premise that securities are imperfect

substitutes in investors’ portfolios, reflecting differences in liquidity, transactions costs,

information, regulatory restrictions, and the like. Imperfect substitutability implies that changes

in the net supply of a security affect asset prices and yields, as investors must be induced to

rebalance their portfolios (Bonis et al., 2017). In principle, the two channels of QE can be

distinguished by the fact that the signaling channel operates by affecting expectations of future

policy rates while the portfolio balance channel works by changing term and risk premiums.

There have been many studies of the effectiveness of QE, mostly through event studies of

the impact of QE announcements on interest rates and asset prices; for surveys, see, e.g., Gagnon

(2016b), Bhattarai and Neely (2016), and Williams (2014). There is not a large sample of QE

programs to study, and econometric identification of the unexpected (and thus not fully

discounted) components of QE announcements is difficult. Consequently, disagreements remain

among researchers about the magnitude and persistence of QE effects and about the relative

importance of the two primary channels of effect. Nevertheless, the strong view that QE is

ineffective has been pretty decisively rejected. There appears instead to be a broad consensus

that QE has proven a useful tool, with demonstrable effects on financial conditions.

5

QE has

been found to have significant effects on both rate expectations and term premiums, suggesting

that both the signaling and portfolio balance channels are operative (Bauer & Rudebusch, 2013:

Huther et al., 2017). And, although showing direct links to macroeconomic outcomes is not

straightforward, the experiences of the U.S., U.K. Japan, and Europe all suggest that the use of

large-scale QE has been followed, over the subsequent couple of years, by strengthening

aggregate demand and improved economic performance (Engen et al., 2015).

6

5

For example, Gagnon (2016b), Table 1, reports 18 estimates from 16 studies of the effects of QE bond purchases

on bond yields. For U.S. data, the median effect of a hypothetical program sized at 10 percent of GDP on 10-year

yields is 82 basis points. Using the conventional rule of thumb that a 10 basis point reduction in the 10-year yield is

about equivalent to a 25 basis point cut in the federal funds, that’s roughly equal to 200 basis points of funds rate

reductions for a program of that size. (The Fed’s program was considerably larger than 10 percent of GDP.)

According to Gagnon’s survey, the median effect of purchases programs on the term premium component of 10-year

yields only is 44 basis points, suggesting that both signaling effects and portfolio balance effects operate.

6

It is true that QE has not been sufficient in a number of those cases to return inflation to target. However, the weak

link in the causal chain appears to be in the influence of declining slack on inflation, not the effect of monetary

11

Controversies about QE have focused less on whether the medicine works and more on

the possible side effects. Many dark warnings accompanied the introduction of QE programs by

major central banks after the financial crisis. In a memorable example, the Republican

leadership of the U.S. Congress wrote to the Fed in November 2010 to express concerns about

further asset purchases. Their letter argued that “such a measure introduces significant

uncertainty regarding the future strength of the dollar and could result both in hard-to-control

long-term inflation and potentially generate artificial [sic] asset bubbles that could cause further

economic disruptions” (Herszenhorn, 2010). The Congressional leaders also were worried about

foreign criticism of the Fed’s actions, noting that “any action….that impairs U.S. trade relations

at a time when we should be fighting global trade protection measures will only further harm the

global economy and could delay recovery in the United States.” As the legislators noted, there

was indeed foreign criticism of Fed plans for more QE, including from Brazilian finance minister

Guido Mantega, who argued that the Fed’s actions presaged a “currency war”, and German

finance minister Wolfgang Schauble, who reportedly called the policy “clueless” (Garnham &

Wheatley, 2010; Atkins, 2010). A subsequent letter from conservative economists and market

participants echoed the themes of the Congressional letter, warning against “currency

debasement and inflation” and adding that QE could “distort financial markets and greatly

complicate future Fed efforts to normalize monetary policy” (Wall Street Journal, 2010). Less

well remembered is that, in September 2011 the Republican Congressional leadership wrote a

similar, follow-up letter, adding the concern that QE could “promote borrowing by

overleveraged consumers” (Wall Street Journal, 2011). Of course, these themes were staples of

Wall Street Journal and Financial Times op-eds throughout the period.

7

I think it’s fair to say that these warnings, and many more like them, have not proved

prescient. Certainly there has been no massive upsurge in inflation—quite the opposite, of

course—or a collapse in the dollar, as predicted by proponents of crude monetarism (of a type,

certainly, that Milton Friedman would never have endorsed). Without a sustained decline in the

dollar, and with a stronger U.S. economy providing increased demand for imports, Mantega’s

concern about a currency war also proved baseless. Household leverage has not risen as the

policy (including QE) on aggregate demand. The apparent flatness (or downward shift) of the Phillips curve is a

problem for any macroeconomic policy aimed at raising inflation.

7

See for example Taylor and Ryan (2010).

12

second Congressional letter predicted; indeed, household debt and interest burdens have fallen

significantly since the crisis.

Concerns about asset bubbles have been especially persistent (although these would

appear to relate more to accommodative monetary policies in general than to QE in particular).

To be clear, there is no doubt that monetary policy affects the prices of stocks and other assets;

indeed, those effects are an important vehicle of monetary transmission. The intended effects of

monetary easing on asset prices work through fundamentals, including the reduced discounting

of future returns implied by lower interest rates, expectations of stronger economic performance,

and moderate increases in risk-bearing capacity. Asset price increases due to those fundamental

causes are desirable and pose no significant risks to economic or financial stability. Concern

about bubbles is therefore properly focused on asset price increases that significantly exceed

what can be justified by fundamentals. Claims that QE has generated asset bubbles in this

relevant sense are difficult or impossible to disprove; and, of course, at some point there will

inevitably be a downward correction in asset prices, as has happened periodically in the past.

However, it’s been seven years since the first Congressional letter, and the Fed stopped

purchasing securities three years ago (although other central banks have continued it), so if QE

has generated bubble dynamics we can at least conclude that some pretty long lags are involved.

What about other critiques? The claim that QE “distorts” financial markets, raised in the

letter from economists and market participants, is heard fairly often. It’s not clear exactly what

that means. The goal of QE, and of monetary policy generally, is to set financial conditions

consistent with full employment and stable prices, which can be thought of as trying to undo the

economic distortions arising from price and wage stickiness, monopolistic competition, credit

market frictions, and the like. In this respect appropriate monetary policy is “un-distorting;” in

particular, allocations under active monetary policy should be closer rather than further from the

competitive, free-market, flexible-price ideal.

A possible rationalization of the “distortion” claim is that QE works, at least in part, by

affecting term premiums (and through them, the whole gamut of asset prices). From a market

participant’s point of view, when QE is active it feels as if government (central bank) decisions,

rather than private-sector fundamentals, are setting asset prices. Moreover, in such situations it

may appear that the highest returns go to the best Fed-watchers, rather than to those whose

expertise is in evaluating economic fundamentals. Some frustration with this state of affairs on

13

the part of professional investors is understandable. Note, though, that QE affects term premiums

by affecting the net maturity distribution of government debt held by the private sector. In this

respect, a QE program—which amounts to a replacement of longer-term government obligations

in private hands with shorter-term obligations (bank reserves, in the case of QE)—is not

fundamentally different from a change in the maturity structure of debt issued by the Treasury.

That government decisions about the maturity structure of its debt would affect term premiums

seems natural and, since the government has to choose some maturity distribution, it’s not clear

what it would mean for government policy to be “neutral” with respect to the term premium

(Greenwood et al., 2014). In short, there is no such thing as an “undistorted” value of the term

premium, not so long as the mix of outstanding government liabilities is relevant to asset pricing.

A possible response to this point is that at least Treasury maturity decisions are largely

non-responsive to short-term economic conditions, with issuance policies generally being

smooth and set well in advance. In contrast, Fed QE programs are typically large in size and less

predictable, responding to economic developments and (importantly) to how monetary

policymakers choose to interpret those developments. To the extent that Fed decisions are hard

to forecast, even conditional on the outlook, they add noise to asset prices. But of course that is

true for any form of monetary policy. I think it comes down to whether Fed policy, inclusive of

policy errors and misjudgments, is economically stabilizing on net, or not. If it is stabilizing,

then though the unpredictable components of Fed policy and communication may be a nuisance

for market participants, overall monetary policy (including QE) reduces rather than increases the

overall level of distortions in the economy.

8

Another common critique of QE is that it purportedly promotes increased inequality,

primarily because of its effects on the prices of stocks and other assets. This claim is

questionable on its face (Bernanke, 2015; Bivens, 2015). Empirically, it is far from obvious that

QE (or easy money generally) worsens inequality in any meaningful way, once all the diverse

effects of policy are taken into account. It is of course true that, all else equal, higher stock

prices mean greater inequality of wealth—although the effect on income inequality is mitigated

by the fact that easy money also lowers the rate of return on assets, so that income from capital

8

As James Tobin (1977) once said, “It takes a heap of Harberger triangles to fill an Okun gap.” Translated from

economist, this aphorism suggests that distortions at the microeconomic level are hardly of consequence when the

economy as a whole is operating far from its potential. The goal of monetary policy is to close Okun gaps.

14

rises by less than the rise in asset values.

9

However, QE also yields gains in income and wealth

that are more broadly based, including 1) positive effects on house prices, the principal asset of

the middle class; 2) the benefits of lower interest rates and higher prices for debtors, including

homeowners able to refinance to lower payments; 3) the savings for taxpayers of lower

government borrowing costs and (possibly) increased seigniorage; and 4) most importantly, the

effects of monetary accommodation on jobs, wages, and incomes (Bivens, 2015; Engen et al.,

2015). It’s revealing that in public debates, advocates for workers—like the group Fed Up,

which met with FOMC members in Jackson Hole in 2016—have tended to favor the

continuation of easy money, while the typical op-ed about the adverse effects of easy money on

the distribution of income and wealth is written by a hedge fund manager, banker, or right-wing

politician—people who have otherwise not traditionally exhibited much concern about inequality

(Fleming, 2016). That political alignment—workers’ groups in support of easy money,

financiers in favor of higher interest rates—is of course the historical pattern in the United States,

going back to William Jennings Bryan and beyond.

In any case, whatever effects monetary policy has on inequality are likely to be transient,

in contrast to the secular forces of technology and globalization that have contributed to the

multi-decade rise in inequality in the United States and some other advanced economies. If the

monetary effects on inequality are modest (indeed, of indeterminate sign) and mostly temporary,

as seems most likely, then it makes sense for monetary policymakers to ignore distributional

effects and to focus on their legal mandate to promote price stability and full employment,

leaving distributional concerns be addressed by other policies, including fiscal policy. If, on the

other hand, the effects of monetary policy on inequality are not transient, then presumably the

reason is what economists have called hysteresis, the idea that a “hot” economy promotes higher

long-term growth by promoting labor force participation, higher skills, and higher wages.

However, the presence of significant hysteresis effects would likely imply that easy money

during periods of economic weakness reduces inequality, rather than the reverse.

A final criticism of QE is that it exposes the central bank to capital losses, in the event

that longer-term interest rates rise unexpectedly quickly. Although central banks don’t have to

mark to market, and they can operate perfectly well with negative capital, losses on their asset

9

Hence the apparently contradictory claims that QE both helps wealth-holders and hurts savers; see Bernanke

(2015) for a discussion.

15

holdings would ultimately be reflected in reduced seigniorage payments to the treasury. Central

banks naturally see this outcome as a political risk to their independence and institutional

reputations which, all else equal, may make them more hesitant to use QE. However, political

risk to the central bank is not equivalent to a loss in social welfare. From the perspective of

society as a whole, the fiscal risks of QE have to be balanced against the substantial benefits of a

tool that gives monetary policymakers additional scope to respond to a serious economic

downturn or to unwanted disinflation.

Moreover, the fiscal risks of QE are not one-sided. QE programs can be quite profitable

for the central bank and the Treasury, because on average the yields on the longer-term assets the

central bank acquires are higher than those on its short-term liabilities, and because declining

yields create capital gains on the central bank’s existing bond holdings. Since 2009, the Federal

Reserve has remitted more than $650 billion in profits to the U.S. Treasury (Federal Reserve,

2017), a much higher rate of remittances than usual before the crisis. On the other hand, if fiscal

losses do occur as the result of a QE program, it will likely be because the economy recovered

more quickly and strongly than expected, resulting in higher interest rates; since losses are most

likely to occur at times when the economy is unexpectedly strong, they are hedged, from a social

perspective. Finally, and importantly, the beneficial fiscal effects of an effective QE program go

well beyond seigniorage, as the government’s budget also benefits from low borrowing rates,

avoidance of deflation or very low inflation, and the higher revenues that result from increased

economic activity.

All that said, the fiscal argument seems to me to be more balanced than some of the other

criticisms of QE. There are difficult governance issues and competing values in play here, and

people could reasonably come to different conclusions. One approach, similar to that taken by

the United Kingdom, is for the central bank to consult with the Treasury on QE plans. I don’t

advocate that approach because of the implied reduction in central bank independence, but I

appreciate that it may reduce the political risks associated with the use of QE.

Negative interest rates and yield curve control

I will comment briefly on two monetary tools in use outside the United States, but which

I don’t expect to be used by the Fed in the foreseeable future: negative (nominal) interest rates

and pegging longer-term interest rates (so-called yield curve control).

16

Negative interest rates have been recently employed in Japan and a number of European

countries (Bernanke, 2016a). To enforce negative rates, central banks generally charge a fee on

the reserve holdings of commercial banks. Arbitrage ensures that the negative return to reserves

translates into negative returns to other short-term liquid assets. Negative short rates need not

imply negative rates on longer-term assets, particularly those that are less liquid or involve credit

risk. Rather, negative short-term rates give the central bank a new tool for bringing down the

longer-term rates, like mortgage rates, that matter most for economic activity. The evidence

suggests that negative rates have helped to ease overall financial conditions in the countries in

which they have been used, thereby promoting economic recovery (Dell'Ariccia et al, 2017).

For economists, used to thinking about negative real interest rates, moderately negative

nominal rates are not a big deal. There is very little practical difference between a 0.1 percent

return and a return of negative 0.1 percent, for example. However, many non-economists find

the idea of negative nominal rates disorienting, a reaction that has contributed to political

resistance and on the margin has probably made central bankers more hesitant to use this tool.

Putting aside the politics, and excluding limitations on the use of currency (Rogoff, 2016) as

beyond the scope of this note, negative interest rates appear to provide relatively modest benefits

and have modest costs. So while the tool may well be appropriate and useful in some contexts, it

does not merit the overheated public attention it has received.

Under current institutional arrangements, the potential benefit of negative rates are

relatively modest because attempts to push rates too far below zero will induce substitution into

cash. The most negative rate yet imposed is minus 75 basis points, by Denmark (Danmarks,

2015). To date, negative rates have so far not triggered much movement into cash, as best as we

can tell, but it is likely that more such adjustment would occur if rates were to go much further

below zero, or if negative-rate policies were perceived to be recurring or persistent.

The costs of negative rates mostly arise from their interaction with certain institutional

features of financial markets. For example, in the United States, money market mutual funds

(MMMFs) generally guarantee a nominal return of no less than zero, and failure to meet that

standard (called “breaking the buck”) led to a run on MMMFs in 2008, after the Lehman failure.

Concerns about possible destabilization of MMMFs were an important reason that the Fed did

not employ negative rates during the post-crisis period (Burke et al., 2010). Reforms undertaken

since the crisis have reduced this risk, by forcing many money market funds that invest in private

17

assets to shift to a system of floating net asset values (which allows for a negative nominal

return) and by inducing a shift toward lower-risk government funds (SEC, 2014; Chen et al.,

2017).

A more frequently heard concern is that negative rates could decapitalize the banking

system, because banks are supposedly unable to pass negative rates on to depositors and thus

would have to absorb the loss. There is little evidence from the European or Japanese

experiences that modestly negative rates have actually hurt bank profits or bank lending. Retail

deposits are only a portion of bank funding; presumably, banks can pass on negative yields to

wholesale funders or institutional depositors. Moreover, central banks can implement negative

rates in ways that mitigate the effects on bank profits; for example, the Bank of Japan exempts a

significant portion of bank reserves from its fees, which are applied only on the margin. Overall,

there are few costs of negative rates that could not be managed over time through institutional

reform or alternative approaches to enforcing negative rates by central banks. Whether

undertaking such changes is worthwhile, given that political resistance to negative rates appears

disproportionate to their generally modest benefits, is an open question. At the Fed, there was

little support for negative rates during the post-crisis period, a situation that does not appear to

have changed.

10

Yield curve control, recently introduced by the Bank of Japan, is the targeting of yields

on longer-term bonds; e.g., the BOJ is currently targeting the yield of ten-year government bonds

at around zero. Yield curve control is “dual” to conventional QE: Instead of setting targets for

securities purchases and letting the market determine yields, as in ordinary QE, under yield curve

control the central bank targets the yield on one or more securities and adjusts its purchases as

necessary to hit the targets (Bernanke, 2002; Chaurushiya & Kuttner, 2003; Bernanke, 2016b).

Yield curve control has some potential advantages: Because yields directly affect

borrowing and investment decisions, a rate-targeting strategy affords greater precision in

estimating the amount of financial accommodation delivered than does ordinary QE. A credible

yield target may also be enforceable with reduced quantities of purchases by the central bank,

because deviations from the target will be arbitraged away by market participants. Yield curve

10

John Williams, the president of the San Francisco Fed, said in 2016 that negative interest rates “are at the bottom

of the stack in terms of net effectiveness” (Mui, 2016). However, interestingly, Chair Yellen has indicated that she

believes that the Fed has the legal authority to impose negative interest rates should it choose to do so (United

States, 2016).

18

control can also be an efficient strategy when the securities available for purchase are potentially

limited in quantity and supplied with less-than-perfect elasticity, as is the case with the Japanese

government bonds that make up the bulk of the BOJ’s purchase program. In particular, the

adoption of yield curve control by the BOJ has allowed the Japanese authorities to maintain

substantial stimulus, even as the supply of bonds available for purchase by the BOJ has shrunk

(Bernanke 2016d).

On the other hand, in jurisdictions with deep and liquid securities markets, like those for

U.S. government bonds, a rate-targeting central bank might have to buy up most of the market if

the target it set were not fully credible. A rate target for a security whose maturity exceeded the

expected duration of the targeting program would be particularly hard to enforce, as incoming

news would affect investors’ views of the time of exit from the targeting regime and of the post-

regime yield. For that reason, Fed staff considering rate-targeting strategies concluded that only

relatively short-term yields—perhaps up to a couple of years—could be fixed, potentially

limiting the utility of the program (Bowman et al., 2010; Bernanke 2016b). An intriguing

possibility, however, is that a relatively short-horizon peg could be used to complement forward

guidance about future short rates.

11

Policy sequencing

What policy tools will be used, and in what sequence, when the next recession hits?

Yellen (2016) has described the Fed’s prospective toolbox. In the face of an economic

slowdown, the FOMC would respond first with conventional rate cuts. In an environment of

super-abundant bank reserves, in practice that would involve reductions in the Fed’s key

administered rates, including the interest rate paid to banks on excess reserves, the rate offered to

money market funds and others on overnight reverse repurchase agreements, and the lending rate

at the discount window. Current thinking is that, when the ZLB looms, rate cuts should be

aggressive (no “saving ammunition”); see Reifschneider and Williams (2000). However, in

practice, uncertainty about the state of the economy might lead the Fed to put off decisive action

until the situation becomes clearer.

11

For example, a promise to keep rates low for two years would be reinforced by a commitment to peg yields out to

a date two years from the announcement. This strategy would be difficult to implement for state-dependent (as

opposed to time-dependent) guidance, however.

19

Forward guidance, of the Odyssean variety, would come next (substantial Delphic

guidance is already in place). Relative to earlier experience, I would expect a much earlier

adoption of state-contingent, quantitative commitments to hold rates low.

What about QE? Fed policymakers have been clear that QE is now part of the toolkit and

that it would be used if necessary (United States, 2017; FOMC, 2017). I am sure that’s true, but

I would not be surprised if there is a period of hesitation before the FOMC starts up new rounds

of asset purchases. The effects of QE on financial markets and the economy are less well

understood and less precisely estimated than those of more-conventional policies. QE’s effects

likely vary over time, depending for example on whether financial markets are stressed or

operating normally. Moreover, because some significant part of its power comes through

signaling effects, QE is also a difficult tool to use in a continuous, gradated manner. I expect

that QE will be used only occasionally in the future, during more severe downturns, and then

typically in large discrete chunks.

Speaking positively rather than normatively, I don’t see much likelihood that negative

rates or yield curve control will be employed in the United States in the foreseeable future,

unless circumstances become dire. Given current institutional arrangements, negative rates have

only modest benefits and may create problems for some financial institutions. Targeting longer-

term interest rates, at least at maturities out beyond a couple of years, could be a hazardous

undertaking given the deep and liquid markets for U.S. government obligations. It is not

inconceivable though that the Fed might consider targeting yields at somewhat shorter horizons,

particularly as a way of reinforcing its forward guidance on rates.

DEFEATING THE ZLB: THE POLICY FRAMEWORK

As discussed in the previous section, the Fed and other central banks retain a number of

effective monetary tools, even if the current low level of neutral rates persists. In particular, the

experience gained in recent years with forward guidance, quantitative easing, and (in some

jurisdictions) negative interest rates should at least partly compensate for the reduced scope for

conventional rate cuts. We should also not ignore the countercyclical potential of fiscal policy.

Political and ideological constraints, as well as constraints on fiscal space in some jurisdictions,

limit the flexibility and timeliness of fiscal tools; that’s why monetary policy has normally been

the first line of defense against short-term economic instability. But recent experience suggests

20

that fiscal policy can provide some backstop in the most severe slowdowns, as in the United

States in 2008 and 2009 (Matthews, 2011; Auerbach and Gorodnichenko, 2017).

All that said, I am less sanguine than Yellen (2016) that the current monetary toolbox

would prove sufficient to address a sharp downturn. In particular, there is no guarantee that the

next recessionary shock will occur only when policy rates are at or above neutral levels. If the

Fed had to react to a new slowdown today, it would have only 100 basis points or so of room to

cut short rates, and other major central banks (such as the ECB and BOJ, whose short rates are

already negative) would have virtually no room to cut, even at the long end of the curve. I am

consequently sympathetic to the view of Williams (2017) and others that we should be thinking

now about what can be done to enhance the potency of monetary policy. In this section I’ll

discuss some recent proposals to improve the effectiveness of monetary policy by changing the

policy target/framework. I’ll focus here on two leading options: raising the inflation target and

switching to a price level target.

12

After discussing some pros and cons of these two leading

options, I’ll suggest a compromise approach.

As noted, one proposal for modifying the policy framework is to keep the current

inflation targeting framework of the Fed and other major central banks, but to raise the level of

the target—from 2 percent or so to 3 or even 4 percent. Presumably, after a period of transition,

an increase in the inflation target would result in a comparable increase in nominal interest rates.

Higher nominal rates would in turn expand the scope for short-term rate cuts and reduce the

salience of the zero lower bound at all points of the yield curve.

13

Most recently, a group of

economists signed a letter to the Fed arguing for a higher inflation target, and the aforementioned

Fed Up group held a seminar at this year’s Jackson Hole conference endorsing the idea (Baker et

al., 2017; Leubsdorf, 2017).

As a measure to increase the potency of monetary policy, raising the inflation target has

some advantages: It’s a straightforward step, one that should be easy to communicate and

explain, and it would allow the Fed and other major central banks to stay within their established

12

An option that deserves further study, but which I don’t have space to discuss here, is nominal GDP targeting. A

practical issue with this approach is that measurements of nominal GDP are not as timely as those of inflation and

unemployment, and more subject to revision.

13

Should the increase be to 3 percent or 4 percent? The literature offers limited guidance (Diercks, 2017). An

increase to 4 percent provides more room for future rate cuts, but it might be difficult to defend 4 percent inflation as

being consistent with central bank mandates for price stability. An increase to 3 percent adds only modest scope for

rate cuts; if that is the increase contemplated, it would be desirable to compare the costs and benefits of that increase

with the adoption of negative rates, which add similar amounts of policy space (Bernanke 2016c).

21

policy frameworks. These are important benefits. At the same time, I see some problems with

this proposal:

First, proponents may be underestimating the costs, uncertainties, and delays associated

with the transition to a higher target. We have seen, most recently in Japan, that managing

inflation expectations through central bank announcements can be tricky. Given that inflation

expectations in advanced economies seem well anchored at two percent or below, trying to raise

expectations and to re-anchor them at a higher level could well be a protracted and uncertain

process, with side effects including financial volatility and increases in risk premiums. (Inflation

uncertainty would be particularly challenging for bond markets, where investors would be

simultaneously skeptical of the central bank’s statements and fearful of capital losses.) If

inflation expectations were to remain sticky near current levels, then the Fed would have to

demonstrate its commitment to the higher target by intentionally overheating the economy for an

extended period. It’s possible that sustained overheating could have beneficial effects—through

hysteresis channels, for example—but it might also prove to be destabilizing and difficult to

manage, particularly if inflation expectations became volatile.

Second, to be fully effective in raising longer-term nominal yields, the increase in the

inflation target must be perceived as permanent and irrevocable. However, that perception

would be undermined by the apparent willingness of the Fed to raise its target for what might

appear to be tactical reasons. Looking forward, it is likely that the determinants of the “optimal”

inflation target—such as the prevailing equilibrium real interest rate, the costs of inflation, and

aspects of the monetary transmission mechanism—will change over time. If the Fed raised its

inflation target today based primarily on the low level of real interest rates, would it change the

target again in response to future changes in fundamentals? That would be important to clarify

when making the first change to the target, but it is not an easy matter on which to commit, since

the membership of the policy committee and the state of knowledge about monetary policy and

the economy both change over time.

Third, although quantifying the economic costs of inflation has proved difficult, we know

that inflation is very unpopular with the public. This unpopularity may be due to reasons that

economists find unpersuasive—various forms of money illusion, for example. Or perhaps the

public perceives costs of inflation—the greater difficulty of planning and calculation when

inflation is high, for example—that economic models don’t well capture. In any case, it’s not a

22

coincidence that the promotion of “price stability” is a key part of the mandate of the Fed and

most other central banks. Certainly, a substantial increase in targeted inflation would invite a

backlash, perhaps even a legal challenge. Proponents have suggested convening a national

commission to approve the increase in the inflation target, to increase its legitimacy and

durability. Those proponents should be careful what they wish for. In the United States, rather

than validating a higher inflation target to afford scope for discretionary monetary policy, I

suspect that the political process would be more likely instead to reaffirm the centrality of “price

stability” and possibly even eliminate the “maximum employment” component of the Fed’s dual

mandate. Even if the political process supported the higher target in the first instance, market

participants would put some weight on a future reversal, undermining the target’s credibility.

Fourth, and importantly, we know from a great deal of insightful theoretical work that an

increase in the inflation target is an inferior response to the problems created by the ZLB

(Krugman, 1998; Woodford and Eggertsson, 2003; Werning, 2011). Rather, the theoretically

preferred response is for the central bank to promise to follow a “make-up” policy (or, in

Woodford’s term, for policy to be “history-dependent”). Specifically, suppose the ZLB binds for

a period, keeping monetary policy tighter than it otherwise would have been. Then (speaking

very loosely) the optimal policy involves the central bank promising to keep rates lower for

longer than it otherwise would have, where the length of the “make-up” period increases with the

severity of the episode and the cumulative shortfall in monetary ease. If the public understands

and believes this promise, then the expectation of easier policy and more rapid growth in the

future should act to mitigate declines in output and inflation during the period in which the ZLB

is binding. Note, by the way, the close analogy to Odyssean forward guidance, discussed earlier.

The difference is that, rather than being implemented by ad hoc guidance, the optimal policy is

conceptualized as part of the central bank’s permanent policy framework, about which the public

is supposed to learn over time.

In comparison to this theoretically optimal policy, an increase in the inflation target is

inefficient in at least two respects. First, as Woodford (2009) has pointed out, it forces society to

bear the costs of higher inflation at all times, whereas under the optimal policy, inflation should

rise only temporarily, following ZLB episodes. Second, a one-time increase in the inflation

target does not optimally calibrate the vigor of the policy response to a given ZLB episode to the

duration or severity of the episode.

23

A somewhat better option than raising the inflation target is to adopt a price level target,

an approach advocated by a number of economists and policymakers (Svensson, 1999; Gaspar et

al., 2007; Williams, 2017). Effectively, a price-level targeting central bank tries to keep the long-

run average inflation rate close to a targeted value, say 2 percent. The principal difference

between price-level targeting and conventional inflation targeting is the treatment of “bygones.”

An inflation-targeting central bank aims to keep inflation stationary around its target, an

approach that allows policymakers to “look through” a temporary change in the inflation rate, so

long as inflation returns to target after a time. A price-level targeter, by contrast, commits to

reversing temporary deviations of inflation from target, by following a temporary surge in

inflation with a period of inflation below target; and, likewise, following an episode of low

inflation with a period of inflation above target. Importantly, both inflation targeters and price-

level targeters can be “flexible.” That is, they can take output and employment considerations

into account, in that the speed at which they return to target can depend (and in formal models,

usually optimally depends) on the state of the real economy.

14

In this section I consider only

“flexible” variants of policy rules.

Switching to a price level target has at least two principal advantages over raising the

inflation target. The first is that price-level targeting is consistent with low average inflation

(say, 2 percent) over time and thus with the price stability mandate. Indeed, price-level targeting

arguably promotes price stability better than does inflation targeting, because its commitment to

stabilizing long-run average inflation should lead to considerably less uncertainty about the level

of prices far in the future. The second advantage is that price-level targeting has the desirable

“make-up” feature of the theoretically optimal monetary policy. In particular, under price-level

targeting, periods of below-target inflation (as is likely to happen when interest rates are stuck at

their ZLB) are followed by periods in which the central bank shoots for inflation above target,

leading to “lower for longer” rate-setting.

Adopting a price level target seems preferable to raising the inflation target, but this

strategy too is not without its drawbacks. It would amount to a significant change in the central

bank’s policy framework and reaction function, and it is hard to judge how difficult it would be

to get the public and markets to understand and accept the new approach. In particular,

14

Erceg, Kiley, and Lopez-Salido (2011) show that strict price-level targeting, which ignores fluctuations in output

and employment, does not perform well.

24

switching from the inflation concept to the price level concept might require considerable

education and explanation by policymakers. How quickly, for example, would markets and the

public adjust to the implication of price-level targeting that a burst of inflation today should lead

them rationally to expect lower-than-normal inflation in the future?

Another possible concern about price-level targeting is that the “bygones are not

bygones” aspect of this approach is a two-edged sword. Under price-level targeting, the central

bank cannot “look through” supply shocks that temporarily drive up inflation, but must commit

to tightening policy in order to reverse the effects of the shock on the price level. This reversal

could be gradual and responsive to real-side conditions, as indeed the theory suggests it should

be, but it would nevertheless imply a possibly painful tightening even as the supply shock

depresses employment and output. Although a once-and-for-all commitment to such an

approach is theoretically optimal (under full credibility), in practice the commitment to reverse

the effect of supply shocks by engineering a period of below-target inflation might not be

credible; if not, efforts to offset positive inflation shocks would likely be costly.

Is there a compromise approach? One possibility, that I will describe briefly here, is to

apply a price level target and the associated “make-up” principle only to periods around ZLB

episodes, retaining the inflation-targeting framework and the current 2 percent target at other

times. As I will explain, the central bank can explain this combined policy in familiar inflation-

targeting terminology, which I take to be an advantage.

So, to be concrete, at some moment when the economy is away from the ZLB, suppose

the Fed were to make an announcement like the following:

(1) The FOMC has determined that it will retain its inflation-targeting framework, with a

symmetric inflation target of 2 percent. The FOMC will continue to pursue its

balanced approach to price stability and maximum employment, meaning in

particular, that the speed at which the FOMC aims to return inflation to target will

depend on the state of the labor market and the outlook for the economy.

(2) However, the FOMC recognizes that, at times, the zero lower bound on the federal

funds rate may prevent it from reaching its inflation and employment goals, even with

the use of unconventional monetary tools. The Committee agrees that, in future

situations in which the funds rate is at or near zero, a necessary condition for raising

the funds rate will be that average inflation since the date at which the funds rate first

25

hit zero be at least 2 percent. Beyond this necessary condition, in deciding whether to

raise the funds rate from zero, the Committee will consider the outlook for the labor

market and whether the return of inflation to target appears sustainable.

The figures below illustrate the necessary condition above as it might have been applied

to the recent ZLB episode. To be clear, nothing in this illustration should be taken as a

commentary on current Fed policy. I am considering instead a counterfactual world in which the

announcement above had been made, and internalized by markets, prior to 2008. In that

counterfactual world, it would be important for the Fed to follow through on that commitment.

However, in reality, no such commitment was made, of course, and actual policy today is not

constrained by earlier promises.

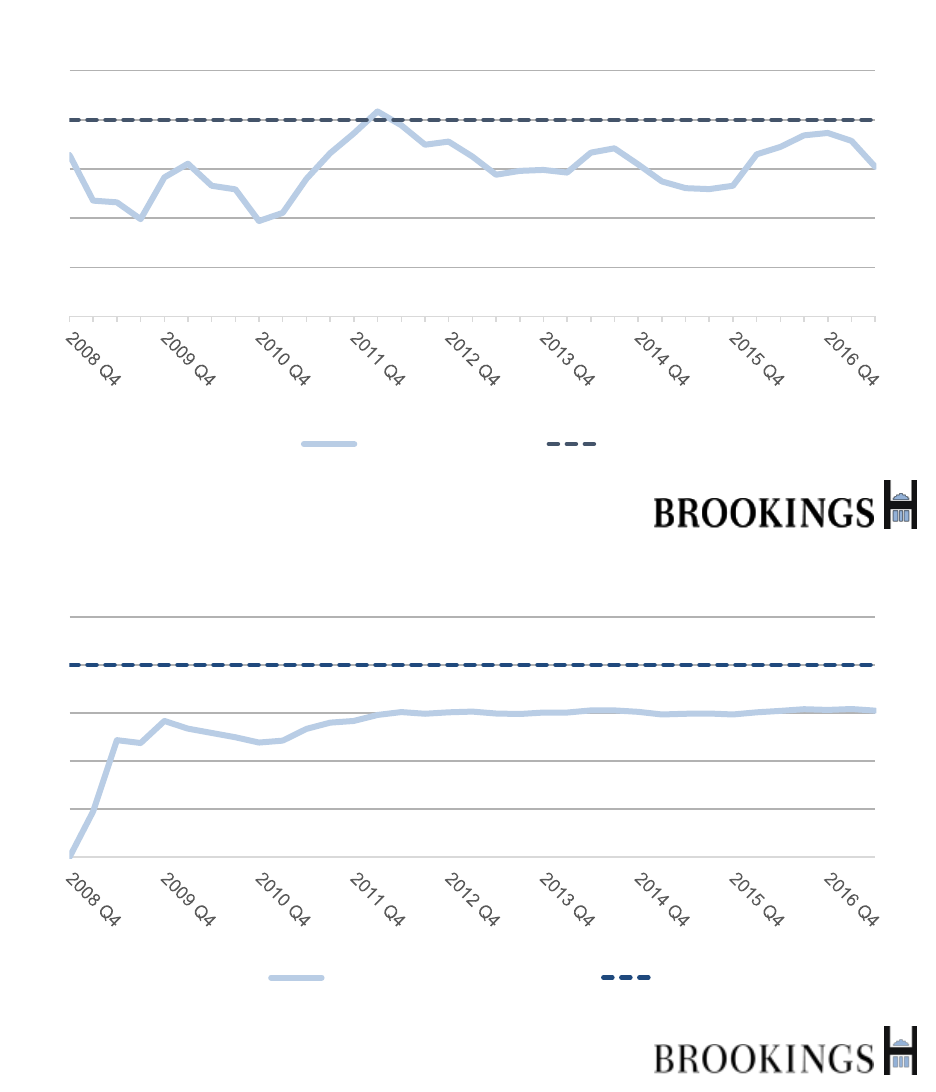

Figure 1 shows the behavior of (core PCE) inflation since 2008 Q4, the quarter in which

the federal funds rate first reached zero, or effectively zero. (I assume for this illustration that

the FOMC relies on the core inflation measure, excluding food and energy prices, to better

capture the underlying inflation trend.) As the figure shows, since 2008, inflation has been

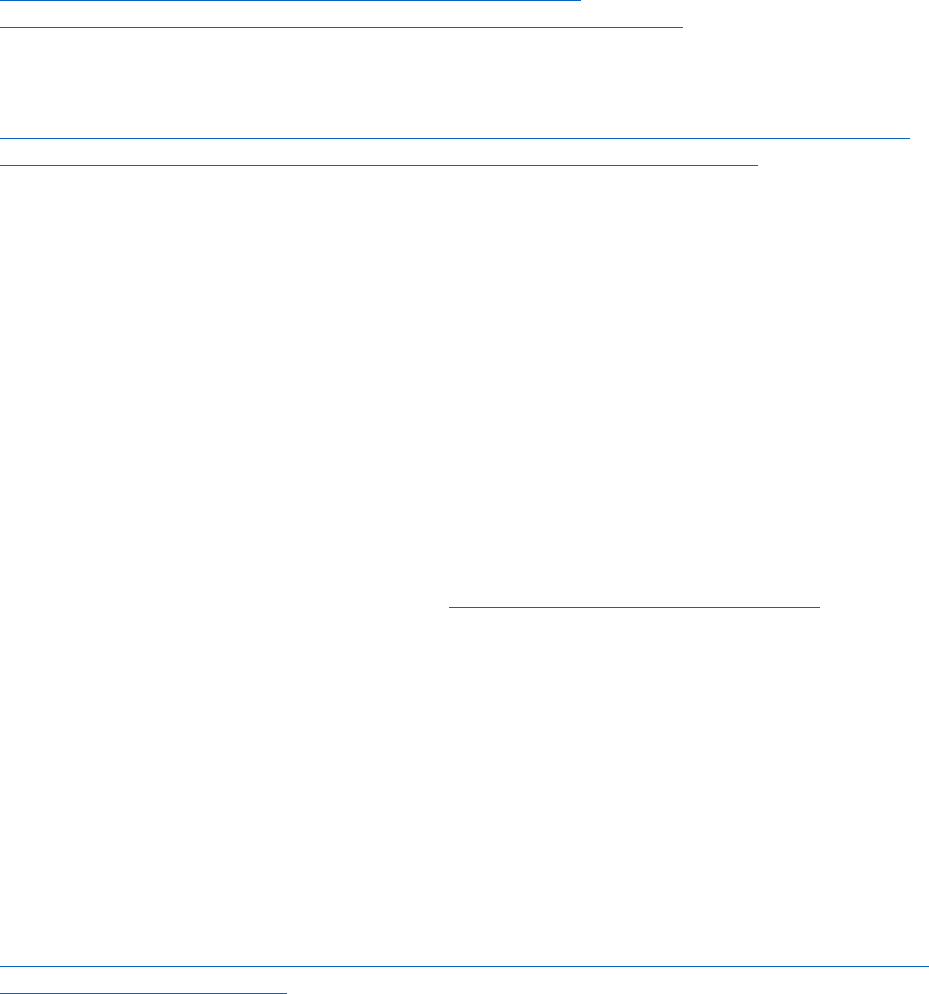

below the 2 percent target most of the time. Figure 2 shows the cumulative, annualized inflation

rate—roughly, the average inflation rate—from 2008 Q4 to the present. Consistent with Figure

1, the average inflation rate since 2008 Q4 is also below 2 percent, by about a half percent. As

average inflation since the beginning of the ZLB period is below the 2 percent target, by the

criterion in paragraph #2 above, the FOMC would not have yet lifted the federal funds rate from

zero. Again, I am using the recent episode to illustrate my suggested rule, not to make a

recommendation about what the FOMC should do now. Note though, that if this policy rule had

been in place prior to 2008, and if it had been understood and anticipated by markets, then

longer-term yields would likely have been lower and the effective degree of policy

accommodation during the past decade might have been significantly greater. In that

counterfactual world, inflation might have been higher and the average-inflation criterion might

have already been met. This is because the Fed would have already communicated their intention

to be more accommodative going into the ZLB episode.

26

The average-inflation criterion, in (2) above, is couched in the language of inflation

targeting, which I take to be an advantage from a communications perspective. My readers will

recognize, though, that the average-inflation criterion is equivalent to a temporary price-level

target, which applies only during the ZLB episode. Expressing this in terms of the price level,

0.00%

0.50%

1.00%

1.50%

2.00%

2.50%

Figure 1: Inflation Since 2008 Q4 (Annual Rates)

Core PCE Inflation 2% Target

Source: FRED.

0.00%

0.50%

1.00%

1.50%

2.00%

2.50%

Figure 2: Cumulative Inflation (Annualized) Since 2008 Q4

Cumlative Inflation (Core PCE) 2% Target

Note: Data shows the cumulative annualized inflation rate of the core PCE price

index since 2008 Q4.

Source: FRED, Author's calculations.

27

rather than inflation, Figure 3 below shows recent values of the (core PCE) price level, relative to

a 2 percent trend starting in 2008 Q4. (Again, 2008 Q4 is the base quarter because that’s when

the federal funds rate first reached the zero lower bound.) The necessary condition, that average

inflation over the ZLB period be at least 2 percent, is equivalent to the price level (light blue

line) returning to its trend (dark blue line). As Figure 3 suggests, a period of inflation exceeding

2 percent would be necessary to satisfy that criterion.

I should emphasize that, in my proposal and as stated in paragraph (2), meeting the

average-inflation criterion is a necessary but not sufficient condition to raise rates from the ZLB.

There are at least two additional considerations: First, monetary policymakers would want to be

sure that the average inflation condition is being met on a sustainable basis and not as the result

of a transitory shock or measurement error. Expressing the condition in terms of core rather than

headline inflation, as in the figures above, would help on that score. Second, consistent with the

concept of “flexible” targeting, policymakers would also want to factor in real economic

conditions in deciding whether it was time to raise rates. Specifically, even if the average-

inflation criterion is met, the FOMC might delay liftoff until labor market conditions are or are

expected soon to be healthy. For example, they might stipulate the additional necessary

90

95

100

105

110

115

120

Index Level, 2009=100

Figure 3: Price Level Since 2008 Q4 vs. 2% Target

Core PCE Price Index 2% Target

Note: Figure shows the core PCE price level against the target core PCE price level,

assumed to rise at a 2% annual rate since 2008 Q4. Equivalently, the target price

level is the level implied by a 2% cumulative (annualized) inflation target during the

ZLB period. Data are seasonally adjusted.

Source: FRED.

28

condition that the unemployment rate be at or below estimates of the natural or sustainable rate.

I elaborate on this point and its rationale in the Appendix.

What I have called a temporary price level target shares several advantages with an

ordinary, permanent price-level targeting regime. As already noted, it has the critical “make-up”

feature, that it delays the exit from the ZLB relative to the prescriptions of conventional policy

rules, like the Taylor (1993) rule. Moreover, the make-up period will generally be longer

following more severe ZLB episodes, thereby delivering more stimulus when it is most needed.

It’s also worth reiterating the distinction between this approach and the Odyssean forward

guidance described in the previous section. The key difference is that, under a temporary price

level target, the lower-for-longer strategy is an integral part of the policy framework and thus can

be explained (and, one hopes, anticipated by market participants) in advance of an encounter

with the ZLB. If this strategy is understood, it should serve to make encounters with the ZLB

not only shorter and less severe but also less frequent in the first place.

The temporary price level target also shares with the ordinary price level target the

benefit of preserving price stability, in contrast to the strategy of simply raising the inflation

target. In particular, under this approach, inflation during both ZLB and non-ZLB periods

should average about 2 percent.

My proposal has two potential advantages over an ordinary price level target, however.

First, it does not require a major shift in existing policy frameworks, since 1) inflation targeting

would continue to define policy away from the ZLB and 2) the temporary price-level target

could be reinterpreted as part of an inflation-targeting regime, in that, as we have seen, it