NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

ISSUES IN THE

COORDINATION

OF MONETARY

AND

FISCAL POLICY

Alan S. Blinder

Working Paper No. 982

NATIONAL

BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050

Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge MA 02138

September 1982

This paper was

prepared

for the conference on "Monetary Policy

Issues in the 1980's," sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of

Kansas City at Jackson Lake Lodge, Wyoming, August 9—10, 1982.

am grateful to Benjamin Friedman, John Taylor, James Tobin, William

Poole and other conference participants for helpful discussions, to

Albert Ando and Rick Sitnes for use of the MPS model, and to the

National Science Foundation for financial support. The research

reported here is part of the NBER's research program in Economic

Fluctuations. Any opinions expressed are those of the author and

not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

NBER Working Paper #982

September 1982

ISSUES IN THE COORDINATION OF MONETARY AND FISCAL

POLICY

Abstract

This paper examines issues in the current debate over

coordination between fiscal and monetary policies.

Section II uses the traditional targets-instruments

approach to assess the potential gains from greater

coordination.

Since greater coordination is often equated with looser money

and tighter fiscal policy, two econometric models of the economy

are used to estimate the quantitative importance of the policy

mix. Expectational effects that arise from the government budget

constraint are also analyzed.

Section III shows that our attitudes toward the non-

coordination problem may be quite different depending on why

policies were not coordinated to begin with, and argues that

there are plausible circumstances under which it may be better

to have uncoordinated policies.

Section IV turns to the design of a coordination system.

The game-theoretic aspects of having two independent authorities

are stressed, and I offer a general reason to expect that

uncoordinated behavior will result in tight money and loose

fiscal policy even when both parties would prefer easy money

and tight fiscal policy.

Finally, Section V considers the old "rules versus

discretiont' debate from the particular perspective of this paper.

Professor Alan S. Blinder

Department of Economics

Princeton University

Princeton, New Jersey 08544

(609) 452—4010

Page 1

I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

Now, as often in the past, there are complaints from all

quarters about the lack of coordination between monetary and

fiscal policy. Indeed, the feeling that monetary and fiscal

policies are acting at cross purposes is quite prevalent. This

attitude, I think, reflects dissatisfaction with the current

mix of expansionary fiscal policy and contractionary monetary

policy, which pushes aggregate demand sideways while keeping

interest rates sky high. This, too, has frequently been so

in the past.

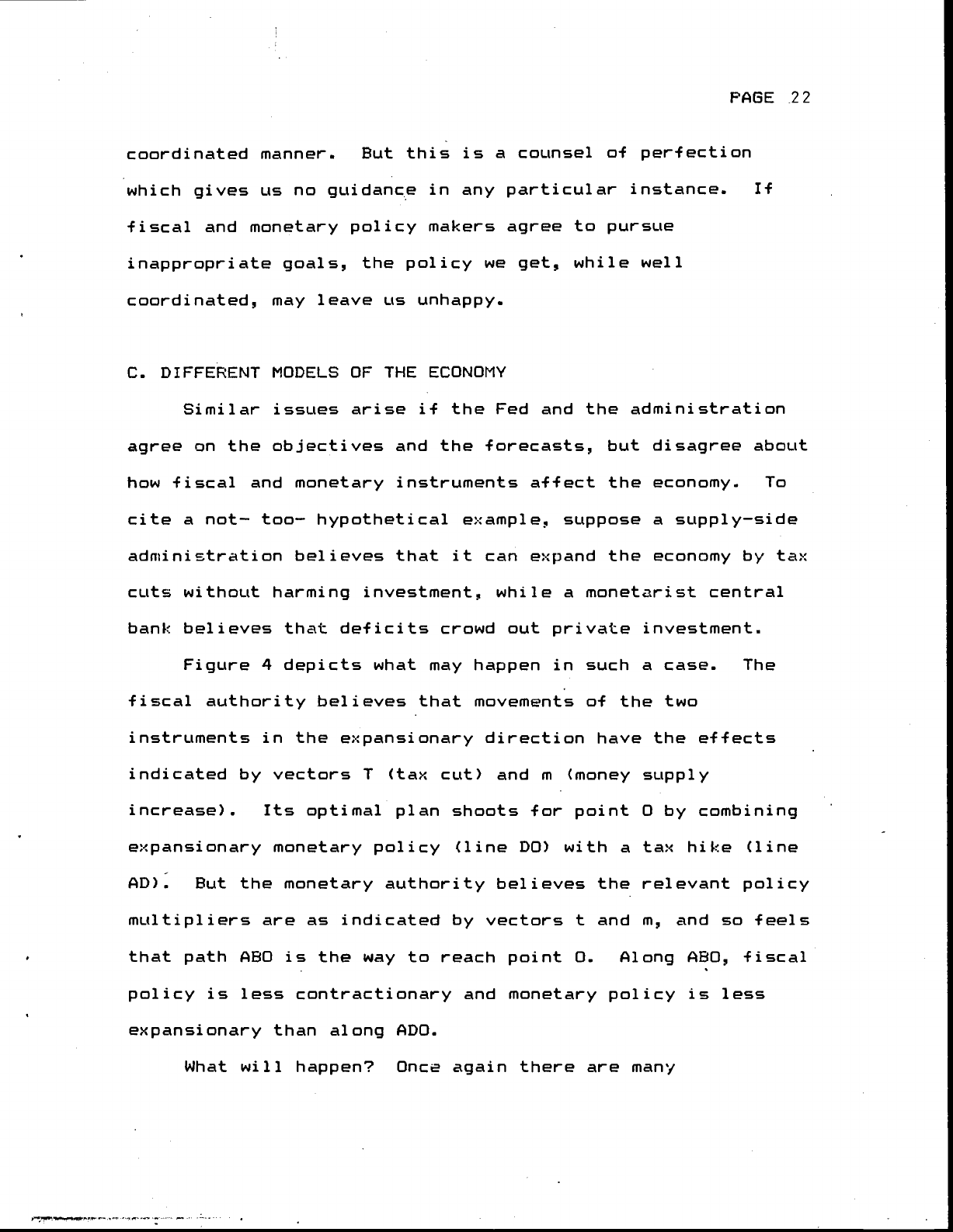

Figure 1 offers a rough impression of the recent history

of monetary-fiscal coordination. It plots the change in the

high-employment surplus (as a crude indicator of the thrust

of fiscal policy) on the horizontal axis and the change in

the growth rate of M1 (as a crude indicator of monetary

policy) on the vertical axis for the years 1961-1980. The

scatter of points does not leave the impression of a strong

negative correlation, as might be expected from well-coordinated

policies. But even by these lax standards, the projected

points for the early 1980's (falling moneygrowth rates with

widening high-employment deficits) will--if realized—-be

exceptional.

The clear implication of the current debate is that greater

coordination between the fiscal and monetary authorities would

Page 1A

A

money

crrowth rate

5

4

•67

3

72

2

•

63

76

70

71.

1

68

•

64

•

78

65

—1

80

62

74

—2

66

—3

—4

•73

69

—5

I

I

I

AHES

-30 -20

-10

0

10 20

I

-V

Page 2

-

be

better. There is so much unanimity on this point that even

an observer as distrustful of government as Milton Friedman

(1982) has urged that the Federal Reserve be brought under

the control of the administration.

This paper tries to take a fresh look at the coordination

issue. Among other things, it raises the possibility that

greater coordination might actually make things worse! The

paper takes as its objectives to raise questions, to clarify

issues, and to stimulate discussion rather than to provide

answers. Where answers are suggested, they should not be

interpreted as etched in stone.

Section II, which follows this summary, focusses on the

potential gains from greater coordination between monetary and

fiscal policy. The first part uses the traditional targets-

instruments approach to examine the possibility that coordination

might not be terribly important because the authorities have

more instruments than they need to achieve the goals of stabiliza-

tion policy. A variety of considerations, however, argue against

the empirical relevance of this possibility.

Since greater monetary—fiscal coordination is often

equated with looser money and tighter fiscal policy, the second

part of this section appeals to two econometric models of the

economy to estimate the quantitative importance of the so—called

mix issue. The empirical results suggest that the effects of

changes in the monetary—fiscal mix may not be as large as many

suppose.

Page 3

The final part of Section II deals with expectational

effects that arise from the government budget constraint, here

interpreted to state that the current mix of policies has

important implications for the range of policy combinations

that will be available in the future. I show that the government

budget constraint allows more degrees of freedom than some of

the recent literature suggests, and argue that some authors

have overplayed the role of expectational effects which, while

present, may not be dominant.

Section III turns to the reasons for lack of coordination,

and shows that our attitudes toward the non-coordination problem

may be quite different depending on why policies were not

coordinated to begin with. Here I argue that there are

plausible circumstances under which it may be better to have

uncoordinated policies. An analogy will explain why this may

be so.

Consider the problem of designing a car in which student

drivers will be taught to drive. The car will have two steering

wheels and two sets of brakes. One way to achieve "coordination"

is to design the car so that one set of controls——the teacher's

——can always override the other. And it may seem obvious

that this is the correct thing to do in this case. But now

suppose that we do not know in advance who will sit in which

seat. Or what if the teacher, while a superior driver, has

terrible eyesight? Under these conditions i± is no longer

obvious that we want one set of controls to be able to override

the other. Reasoning that a stalemate may be better than a

Page

violent collision, we may decide that it is best to design the

car with two sets of competing controls which can partially

offset one another.

Using the two previous sections as background, Section IV

discusses alternative fiscal—monetary arrangements ranging from

perfect coordination to complete lack of coordination. The

focus here is clearly at the "constitutional" level: what kind

of coordination system would we like to devise? The game-

theoretic aspects of having two independent authorities are

stressed, and I offer a general reason to expect that uncoordinated

behavior will result in tight money and loose fiscal policy

even when both parties would prefer easy money and tight fiscal

policy!

Finally, Section V considers the old "rules versus

discretion" debate from the particular perspective of this paper.

Rules are viewed as ways to resolve the coordination problem

and to alter the fiscal-monetary mix..

I conclude that the

celebrated k—percent rule for money growth is unlikely to score

highly on these criteria, and suggest two other rules that

might do better.

PAGE 5

II. TARGETS INsTRUMENTS., AND THE GAINS FROM COORDINATION

A. TARGETS AND INSTRUMENTS

The traditional targets and instruments approach of

Tinbergen and Theil provides a useful framework -for thinking

about monetary— fiscal coordination because the coordination

problem is basically one of an effective shortage of

instruments.. Were there, for example, as many fiscal

instruments as targets, the administration might not have to

worry about coordinating its actions with those o-F the

central bank.

As we know from Tinbergen and Theil, simply counting up

instruments and targets is not enough; we need to know how

many independent instruments we have, and this depends on

both the model of the economy and the precise list o-f

targets.. For example, a plausible set of targets -for

stabilization policy might be the level of output (y), the

price level (P), and the share o-f GNP invested (I/Y).

If the

fiscal instruments are government spending (6) and the

personal income tax rate (t), then, provided that supply—

side effects a-f tax cuts are big enough, we may have just the

number of instruments we need ——

but

only i-f monetary policy

is perfectly coordinated with fiscal policy. Lack of

coordination will make a suboptimal outcome inevitable.

PAGE 6

But what if we add a third fiscal instrument:

investment incentives such as accelerated depreciation or an

investment tax credit? Then, at least in principle, fiscal

policy can go it alone: it can achieve the desired levels of

the three targets regardless c-f what monetary policy does.

Now, the notion that monetary policy is a redundant

instrument may not sit well within the Federal Reserve

System. Nor should it, for there surely are additional

targets. For example, we may want to shift the mix of

investment spending away from housing and toward business

fixed investment. To this end, we may want to keep interest

rates high to discourage residential construction while

simultaneously providing strong tax incentives for industrial

capital formation.

In fact, precisely this policy mix has

been advocated by Feldstein (1980a) and others, and appears

to have been put in place by the Reagan administration. <1> A

second example is the foreign exchange rate which is strongly

influenced by the level of short—term interest rates, and

hence by central bank behavior.

-

The

likelihood that we have surplus instruments at our

disposal is further diminished by a number of other

considerations. One is that there may be many more targets

than the three traditional ones. For example, the use o-f

tax—and—transfer policies may also be influenced by important

distributional and allocative objectives. The same may be

true of government expenditures; and defense spending

PAGE 7

involves a host of other complex criteria.

In addition, the

mix between monetary and -fiscal policy may be influenced by

regional or sectoral objectives, or perhaps just by a desire

not to force one region or sector to bear too mLtch of the

burden of stabilization policy. For example, a desire not to

devastate the housing industry may be a reason not to rely

entirely on restrictive monetary policy to limit aggregate

demand. Like fiscal policy; monetary policy also has

important allocative effects.

In fart, the situation is a good deal worse than this

because the instruments themselves may be targets. It may

be, for example, that the government has an explicit

objective for the ratio o-( 6/? which limits the use of S as a

stabilization tool. Or perhaps sizable movements in policy

instruments entail significant costs of their own ——

costs

which preclude moving all the way to the global optimum.

Timing considerations make it still less likely that we

have more instruments than we need. Policy instruments like

6 and M may have rather different effects on target variables

in. the short and long runs. For example, both probably have

strong (and rather similar) effects on unemployment in the

short run, but little if any effects in the long run. This

makes it crucial to coordinate monetary and fiscal plans as

they un-fold through time.

Uncertainty may also reduce the effective number of

instruments. For example, we may feel less uncertain about

PAGE 8

the effects of particular monetary— fiscal combinations than

we do about the effects of individual instruments used in

isolation. If so, then coordination becomes that much more

critical.

The conclusion seems to be that, while it is logically

possible that we have more instruments than we need, the real

world seems to be characterized by a shortage of instruments

in the relevant empirical sense. Consequently, we should

expect failure to coordinate fiscal and monetary policy to

lead to losses of social welfare..

B. THE CAPITAL—FORMATION ISSUE

As I mentioned at the autset concern

that our current

policy mix will prove damaging to capital formation seems to

be the potential loss of social welfare that is at the heart

of contemporary worries about

monetary—fiscal

coordination.

Because of their effects on investment, each of the tools

of demand management also has long—run implications for

aggregate supply. Put most simply, fiscal expansion probably

pushes up real interest rates, thereby inhibiting capital

formation and slowing the growth of aggregate supply.

Monetary expansion should have the opposite effects on

interest ratesand investment. Therefore, it is argued, a

tighter fiscal policy and a looser monetary policy would

provide a climate more conducive to investment and growth.

But just how large are these effects in practice?

PAGE 9

To get a serious quantitative answer, I see no place to

turn but

to

the much—maligned large—scale econometric models.

Otto Eckstein and Christopher Probyn (1981) recently reported

the results of

a

simulation exercise

with the DRI

model in

which the actual fiscal and monetary policies of the

1966—1980 period were replaced by a mix of policies less

expansionary on the fiscal side and more expansionary on the

monetary side.

The period in question was one in which DRI's version of

the full—employment deficit averaged about $27 billion,

varying between ahcut zero and $64 billion. In the

alternative scenario simulated by Eckstein and Probyn the

fLd 1

—empl

oymerit budget was

rough

I

y bal ariced every year, and

monetary

policy (defined by nonborrowed reserves) was

adjusted to maintain approximately

the same time

path for the

unemployment rate.

How

different would the economy's

evolution

have been under

this alternative monetary—fiscal

mix?

According to the

DRI model, the investment share in GNP

would

have been about one—half percentage point

higher in a

typical year of the simulation, leading to a cumulative

increase in the capital stock over the 15—year period of

about 5.37.. As a consequence, potential (and hence actual)

real GNP in 1980 would have been about 1.67. higher than in

the historical record. The GNP deflator in

1980 would have

been

2.67. lower, which translates to an average reduction in

PAGE 10

the

annual inflation rate of

about 0.2 percentage

points.

As Robert Solow once remarked, the nice thing about

large—scale econometric models is that they always have an

answer for

every question. What

we want to know, of course,

is whether the DRI model's answer to this particular

question

is roughly correct. This, unfortunately, is unknowable. The

next

best thing is to get another large—scale

model to answer

the

same question, and then compare the responses.

Fortunately,

Albert Ando kindly volunteered to run more or

less the same policy change on the MPS model. Some

modifications had to be made because of the different

structures of the two models. (Examples: Neither

full—employment GNP nor the full— employment deficit is

a

variable in the MPS

model; the simulation period was

1967—1981 instead of 1966—1980.,) But an effort

was made to

come as close as possible to duplicating the Eckstein—Probyn

policy of tighter budgets and looser money with no effect

on

Linempi oyment.

The MPS results were generally less

sanguine about the

potential gains from a switch in the policy mix. For

example, the share of business fixed investment in GNP

was

only about 0.3 percentage point higher in a typical

year of

the easy—money, tight—fiscal simulation with the

MPS model.

Correspondingly, the gains in real output were smaller: real

GNP in the final year of the simulation

was just 1V. higher

(versus 1.67. with the DRI model).

PAGE 11

Bigger differences emerged on the price side of the

model. Whereas the DRI simulation said that the GNF deflator

would be 2.67. lower by the end of the 15—year period, the MPS

model put the de-Flator 0.57. higher. The difference here

seems to stem from the divergent behavior of the money supply

in the two models. According to the DRI model, the "easier

money" policy actually leads to a slightly lower money

supply whereas the MPS model shows the money supply

increasing slightly.

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. But these

effects, while generally favorable, seem quite

modest

to me

especially when you realize that the swing in fiscal policy

was extremely substantial. Under the historical

stabilization policy mix, the cumulative increase in the

national debt during this 15—year period was more than $350

billion for DRI and about $450 billion for MPS. Under the

hypothetical policy with a balanced full—employment budget,

the debt would have declined by about $45 billion according

to DRI and by about $19 billion according to MPS.

-

Thus,

according to these models, an enormous change in

the policy mix would have caused only a modest increase in

real output.

And

the two models cannot even agree on whether

prices would have increased or decreased as a result.

C. THE GOVERNMENT BUDGET CONSTRAINT AND EXPECTATIONS

Dynamic constraints across choices of policy mixes

PAGE 12

arise from the so—called government budget constraint, the

accounting identity that insists that every budget deficit

mLlst be financed by selling bonds either to the public or to

the Fed. This identity points out that today's fiscal—

monetary decisions have implications for the number o-f bonds

that will have to be sold to the public today, and thus for

the feasible set of fiscal—monetary combinations in future

periods. <2>

For example, suppose an expansionary -fiscal policy today

leads to a large deficit that is not monetized. Future

government budgets will therefore inherit a larger burden of

interest payments, so the same time paths of 6, t, and M will

lead to larger deficits. What will the government do about

this? That depends on its reaction function. For example,

large deficits and high interest rates might induce greater

monetary expansion in the future (the possibility emphasized

by Sargent and Wallace (1981)).

Alternatively, it might

induce future tax increases (the case stressed by Barro

(1974)), or cuts in government spending (the apparent hope of

Reaganomics). Yet another possibility is that the government

will simply finance the burgeoning deficits by issuing more

and more bonds. <3>

All of these are live options, and have different

implications for the long run evolution of the economy. In

fact, under rational expectations, they may have different

implications for the current state of the economy.

PAGE: 13

Consider, as an example, the effects on consumer

spending of a tax cut financed by issuing new bonds. Such a

tax cut today enlarges current and prospective future budget

deficits, thereby-requiring some combination of the following

policy adjustments:

(1) increases in future taxes;

(2) decreases in future government expenditLires;

(3) increases in future money creation;

(4) increases

in

future issues of interest— bearing

national debt.

To the extent that

the

current decisions made by individuals

and firms

are influenced

by their expectations about the

future, each of these alternatives may have different

implications for the effects of the tax cut today.

For example, if people believe that a tax cut financed

by

bonds simply reduces today s

taxes

and raises future taxes

in order to pay

the

interest on the bonds, then consumption

may not be affected.. This is essentially

Barro's (1974)

argument.

Alternatively, people may believe that the policy will

eventually lead to

greater money creation.

I-f

so, the

inflationary expectations thereby engendered may affect

their

current

decisions in ways that are

not

captured by standard

behavioral 4unctions. This is

essentially

the

point

made by

Sargent and Wallace (1981)

in

arguing that tight

money may be

inflationary.

PAGE

Still

different reactions would be expected if people

thought the current deficit would lead to lower government

spending or to more bond issues in the future. The

theoretical possibilities are numerous,

limited

only by the

imagination of the theorist. <4>

Rational expectations interact with the government budget

constraint in an important way. Feopie's beliefs about the

futL(re consequences of current monetary—fiscal decisions are

conditioned by their views of the policy rules that the

authorities will follow. To the extent that these beliefs

affect their current behavior, different policy rules

actually imply dif-ferent short—run policy multipliers under

rational expectations.

A key question for policy formulation is: how impnr1nt

are these expectational effects in practice? This seems to

depend principally on how forward—looking current economic

decisions really are. Take the tax cut example again. Under

the pure permanent income hypothesis (PIH) only the present

discounted value o-f

lifetime

after—tax income flows affects

current consumption. <5> So expectations about future budget

policy should have important effects on current consumption.

But if short—sightedness. extremely high discount rates, or

capital market imperfections effectively break many of the

links between the future and the present, then current

consumption may be rather insensitive to these expectations

and rather sensitive to current income. Even under fulJ.y

PAGE 15

rational expectations and the pure PIH, consumption may

depend largely on current income if the stochastic process

generating income is highly serially correlated. These are

issues about which knowledge is accumulating; but

much

remains

to be learned. The

evidence to date

does not lead to

the

conclusion' that long—term expectations rule the roost.

<6:::.

The other two places where expectations about future

fiscal

and monetary policies might have significant effects

on current behavior are wage and price setting and

investment.

Investment., of courses is

the

quintessential example o-f

an

economic decision which is stronqly conditioned by

expectations about the -Future. Even Keynes knew this

But

once again, there are some

real—world considerations

that

interfere

with the strictly neoclassical view of investment

as the

unconstrained solution to an

intertemporal

optimization problem. One is that capital rationing may

interfere with a firm's ability to run current losses on the

expectation of

future

profits. A

second

is that management

may use ad hoc rules such as the payback period criterion in

appraising

investment projects. A third is that management

may be more shortsighted than it

"should be." A

fourth is

that there may be ——

and probably is —— a strong accelerator

element

in investment spending, which ties the current

investment decision much more tightly to the current state of

PAGE 16

the economy than neoclassical economics recognizes. As in

the consumption example, each of these things diminishes the

importance of the fLiture to current decision making and

thereby renders expectational effects less important.

Wage and price setting is another important example. Ad

hoc rules which adjust wages or prices in accordance with

"the law of supply and demand," or which are mainly backward

looking, render expectational effects rather unimportant.

But rules which are based on forward looking considerations

(such as expected future excess demand) make expectational

effects crucial. Again, this is an area where we must learn

much more before we can make any definitive judgments. <7>

A word on uncertainty seems appropriate before leaving

this topic. It seems to me that people probably attach great

uncertainty to their beliefs about what future government

policies will be.

If so, the means of their subjective

probability distributions may have far less influence on

their current decisions than the contemporary preoccupation

with rational expectations would suggest. For example, how

much influence does the two— week— ahead weather forecast

have on your decision about whether or not to plan a picnic

on a given date?

Similarly, the importance of expectations for

macroeconomic aggregates is diminished by the likelihood that

different people hold different expectations about what

future government policies are likely to be. <8> If some

PAGE 17

people believe today's tax cuts signal higher future taxes,

some believe they signal higher future money creation, and

some believe they signal lower future government spending,

then expectations about the future may have

meager current

effects in the aggregate.

The conclusion seems to be that, while we should not

forget about expectational effects operating through the

government budget constraint, neither should we get carried

away by them. There is no reason to believe that they are

the whole show.

III. REASONS FOR LACK OF COORDINATION

Is more coordination necessarily better? At first

blush, this question seems to admit only an affirmative

answer. But further reflection suggests that things are not

quite so clear.

If the central bank and the government agree on what

needs to be done, but a coordinated approach cannot be

promulgated because of perverse behavior by one o-f the two

authorities, then it is clear that coordination must

improve

things. Indeed, the type of coordination we want is also

clear: the sensible policy maker must dominate the

perverse

one. Would that things were so simple'

PAGE 18

So let us ask why, in reality, fiscal and monetary

policies are sometimes so poorly coordinated. If we assume

that both authorities are basically sensible, then lack of

coordination can stem from one of three causes (or, of

course, from combinations of the three):

(1) The fiscal and monetary authorities might have

different objectives, i.e. different conceptions of what is

best for society.

(2) The two authorities might have different

opinions about the likely affects of fiscal and/or monetary

policy actions on the economy,, i.e., they might adhere to

different economic theories.

(3) The two authorities might make different

forecasts of the likely state of the economy in the absence

of policy intervention. Divergent forecasts could result

either from different economic theories (as in (2) above)

or

from different forecasts of exogenous variables.

In each case, if we were certain about which of the two

authorities was correct, then we would know what to do about

the coordination problem. We would simply put all the

policy

levers in the hands of the authority with the

proper

objective or correct theory or accurate forecast, just as we

would want the instructor, not the student, to have ultimate

control over the learn—to—drive car.

PAGE 19

But, in fact, we rarely know this in any particular

case. And we certainly have no basis for setting out a

general constitutional rule predicated on one or the other

authority "always" being right. As a consequence, we may

conclude, as in the student driver example, that the best

strategy is to give some power to each authority, but at the

same time to give each some ability to cancel out the actions

o-F the other.

Let us examine each of the three possible reasons for

lack o-f coordination in turn, using the simple targets—

instruments framework. To keep the discussion as elementary

as possible, I assume (for thissection only) that there are

to targets and two instruments.

A. A FRAMEWORK

In

Figure 2 there are two

targets: the gap between

actual

and potential real output (y — y*), which serves as a

proxy for both unemployment (via Okun's law) and inflation

(via the short—run

Phillips curve), and

the share of

investment

in GNP (I/Y). Similarly, there are

two

instruments: monetary and fiscal policy. Point A indicates

the position which the economy is forecast to attain if

neither policy instrument is changed.

I-f the origin is

interpreted as the global optimum, then real output is too

high and the investment share is too low.

The vectors m and f, emanating from point A, indicate

Page 19A

Y

PAGE 20

the effect of a unit expansionary move of the monetary and

fiscal instrument, respectively.

Expansionary fiscal and

monetary policies each raise output

(thereby

lowering

unemployment and raising inflation), but monetary expansion

raises investment while fiscal policy expansion lowers it.

The line from A to 0 shows that a fully coordinated fiscal

and monetary plan can in this case achieve the global

optimum. And the dotted lines from A to B and from B to 0

indicate the two pieces of the coordinated policy plan:

fiscal restriction pushing the economy from A to B and

monetary expansion pushing from B to 0.

Having outlined this ideal situation, let us now

consider the various reasons for lack

of

coordination.

B. DIFFERENT OBJECTIVES

First assume that the monetary and fiscal authorities

agree both on the relevant economic theory and on forecasts

for all the important exogenous variables. They disagree

only over the objectives of economic policy.

-

Figure

3 adds one new wrinkle to Figure 2.

The target

of the fiscal authority is assumed to be point F, while the

central bank wants to push the economy to point N, which has

a lower level of real activity, instead. If the

administration is given control over both instruments, then

point F will result along the path ABF. But if the central

bank is dominant, then point N will result along the path

PAGE 21

ADM. Monetary policy will be less expansive and fiscal policy

more restrictive.

-

But what will happen if neither authority is in complete

control? That is difficult to say One possibility ——

though

certainly not the only one —— is that the central bank

will put the monetary portion of its optimal plan (line DM)

into effect while the government follows the fiscal portion

of its own optimal plan (line AB). This is certainly an

instance that we would call "lack of coordination." But is

the outcome so bad?

Figure 3 shows that the economy will reach point C,

which is a kind of compromise between point F (the

administration's target) and point M (the Fed's target). If

the truesocial optimum ——

whatever

that means! —— remains

point 0, then the "uncoordinated" outcome may conceivably be

superior to either of the two "coordinated" outcomes.

But, you may object, would it not be better still if the

fiscal and monetary authorities Jointly agreed to pursue

point 0? 0+ course. But this objection misses the point.

When there is true disagreement about what best serves the

commonweal, how can we expect a joint decision to be reached

except as a political compromise? And why should we think

this political compromise will be any better than point C?

The solution, of course, is simple to state and

impossible to achieve. We want policy makers to agree on

truly optimal targets, and then to pursue them in a

Page 21/i

b

F

0

3

PAGE 22

coordinated manner. But this is a counsel of

perfection

which gives

us no

gL(idanc.e in any particular instance. If

fiscal and monetary policy makers agree to pursue

inappropriate goals, the policy we get, while well

coordinated, may leave us unhappy.

C. DIFFERENT MODELS OF THE ECONOMY

Similar

issues arise if the Fed and the administration

agree

on the objectives and the forecasts, but

disagree about

how fiscal and monetary instruments affect the

economy. To

cite a not— too— hypothetical example, suppose a supply—side

administration

believes that it can

expand the economy by tax

cuts without

harming investment, while a monetarist central

bank believes that deficits crowd ut private investment.

Figure 4 depicts what may happen in such a case. The

fiscal authority believes that movements of the two

instruments in the expansionary direction have the effects

indicated by vectors I (tax cut) and m (money supply

increase). Its optimal plan shoots for point 0 by combining

expansionary monetary policy (line DO) with a tax hike (line

AD). But the monetary authority believes the relevant policy

multipliers are as indicated by vectors t and m, and so feels

that path ABO is the way to reach point 0. Along ABO, fiscal

policy is less contractionary and monetary policy is less

expansionary than along ADO.

What will happen? Once again there are many

Page 22A

.

yc1

/

/

•c:

PAGE 23

possibilities. If the fiscal authority's concept a-F the

optimal plan is promulgated, we will get point 0 if its model

is correct but point F if the Fed's model is correct. On the

other hand, if the Fed's optimal plan is accepted, we will

get point 0 i-f it has the correct model but point M i-f the

administration's model is correct.

An "uncoordinated" system, in which the Fed pursues its

version a-f optimal monetary policy while the administration

pursues its version a-F optimal -fiscal policy, leads to point

C if the Fed has the correct model and point 6 i-f the

government has the correct model. Coordination is obviously

better only i-f a probability blend o-F points 0 and F

(representing domination by the fiscal authority) or a-F

points 0 and M (representing domination by the monetary

authority) is clearly superior to a probability blend a-F

points C and 6.

It is by no means inevitable that this must

be true.

D. DIFFERENT FORECASTS

The case- in which the -fiscal and monetary authorities

agree on both the goals for economic policy and the model of

the economy —— a

remote possibility, it must be admitted ——

requires

no further analysis. Since it is the discrepancies

between the targets and the state the economy would attain

with no change in policy that really matter, the formal

analysis a-f the case of different targets applies here

PAGE 2L

directly. We need only read Figure 3 backwards and view ABF

and ADM as two paths that emanate from different initial

points but lead to the same terminal point.

As before, the principle is obvious, but impossible to

implement: we want to give all the power to the policy maker

with the correct forecast. Good luck' Alternatively, if

neither policy maker has a monopoly on knowledge, we want a

weighted average forecast with appropriate weights. But who

decides on the weights, gets both authorities to use them,

and then makes sure that neither party shades his forecast to

make the weighted average come out more to his liking?

E. CONCLUSION

Where does all this leave us? It seems that whenever

fiscal and monetary policy appear to be uncoordinated e must

ask ourselves: who is right? If there is one clearly

correct policy maker, then the right thing to do is to

achieve coordination by giving it control over all the policy

levers. But if this is not the case, as it often will not

be, we are left with no clear a priori argument that more

coordination is better.

This should not be a foreign notion in a country that

has always prided itself on its constitutional system o-F

checks

and balances. Dispersion of power is one safeguard

against misuse of power, in economic policy as elsewhere. We

know that checks and balances can sometimes lead to

stalemate, or to conflicts between different branches of

PAGE 25

government, but

in

many cases we view this as a reasonable

price to pay for protection against abuse of power. Is

economic policy so different?

One plausible viewpoint is that the fiscal authorities,

being elected officials, have the right social welfare

fLinction, and so their targets for policy should be accepted.

This seems a tenable attitude in a democracy. But consider

the following possibility. Suppose the body politics in its

1914 wisdom, realized that the president and Congress would

be

Linduly swayed by

short—run considerations, and so created

the

Fed as a counterweight to make sure that the long run did

not

get ignored.. Then

we

might

not want

to accept blithely

the

social welfare function of each newly— elected

administration.

Besides, evon if we accept the validity of the

administration's objectives, we are still in a muddle over

what to do if we simultaneously believe that the Fed has a

better model of the economy and is better (or at least more

honest) at forecasting. Can we then force the Fed to reveal

its model and forecasts to the

a!1ministration? Freedom of

information argues that we should try, but past experience

suggests that we may not succeed. But in any case, how can

we be sure that the administration will accept the Fed's

model of the economy?

I think we must face up to the obvious, though

uncomfortable, conclusion. When no one can be sure what is

PAGE 26

the right thing to do5 no one can ensure us that a unified

fiscal— monetary policy authority will do better than the

two— headed horse we now ride.

PAGE 27

IV. ALTERNATIVE MODELS OF COORDINATION

With the previous two sections as background this

section considers a variety of models of fiscal— monetary

coordination (or lack thereof). Two questions occupy our

attention here: What kinds of outcomes are likely to arise

from alternative interrelationships between the fiscal and

monetary authorities? and, Are these outcomes socially

attractive or not? The focus in this section is clearly at

the "constitutional" level, that is, on the kinds of

coordination mechanisms, if any, we would like to put in

place.

A. A SINGLE, UNIFIED POLICY MAKER

At one end o-F the spectrum is the case of. a single,

unified stabilization authority with control over all the

relevant instruments, whether fiscal or monetary. This

system could most plausibly be achieved in the United States

(and in other democracies) by subordinating the central bank

to the administration, as in Friedman's (1982) suggestion.

<9> But whether this would be a better system than what we

have now depends on the considerations outlined in the

previous two sections.

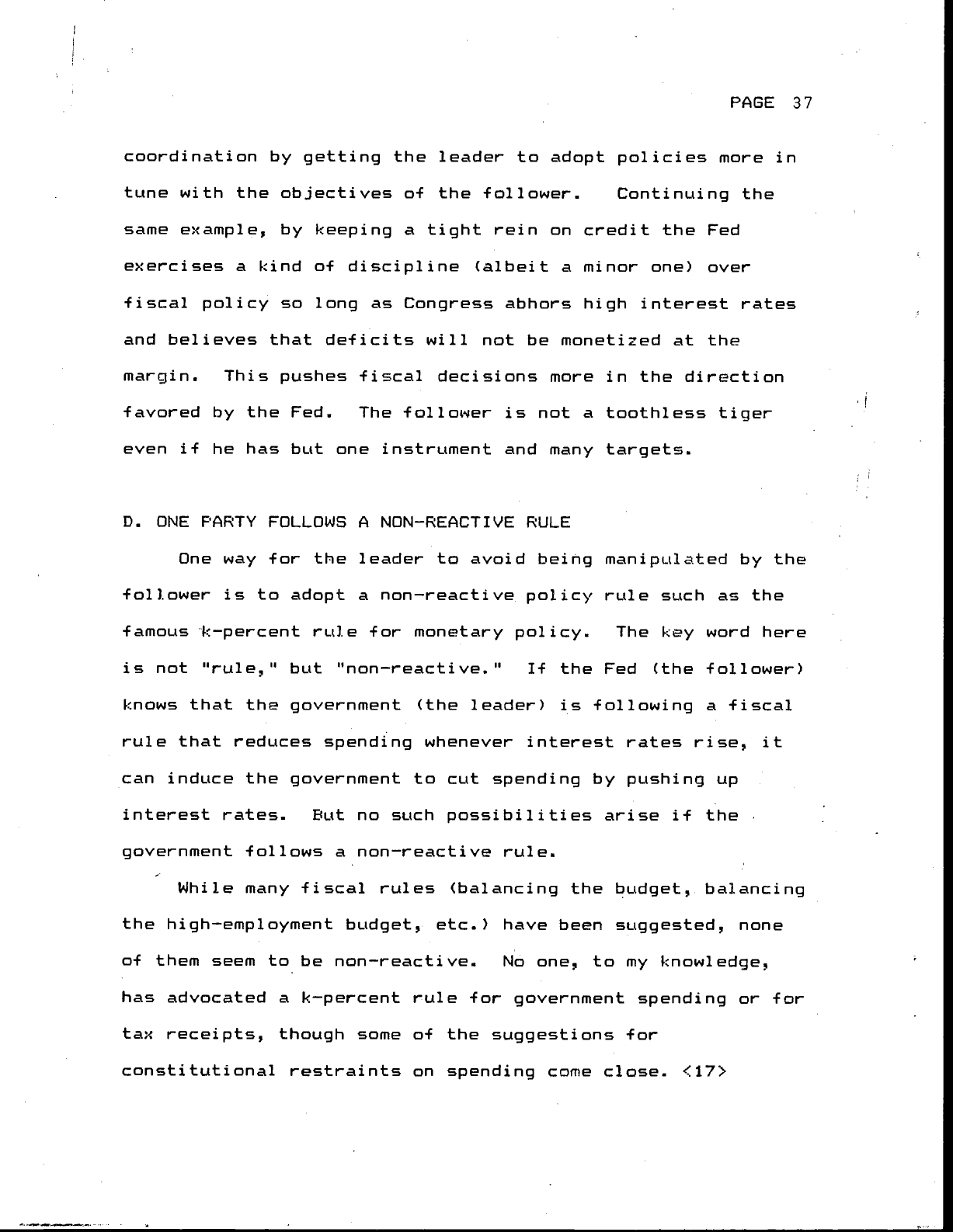

(1) How severe is our shortage of instruments in

PAGE 28

the relevant empirical sense? The greater the shortage,

relative to the targets we are pursuing, the greater the

potential gains from better coordination..

(2) How uncertain are we about the proper goals

and methods of stabilization policy, and also about which of

the two authorities has sounder views on these questions?

The

greater the

uncertainty, the more risky it is to put all

our

eggs

in one

basket.

On balance1 it is far from clear that these

considerations lead to support for Friedman's suggestion. If

we take output (or unemployment), the price level (or the

inflation rate), and the fraction of NP invested as the

three principal target variables, then the shor-tage of

instruments may not be a serious one. s pointed out in

Section II, the fiscal authorities cane in principle, use

control over government purchases, personal income tax rates,

and investment incentives such as depreciation allowances and

the investment tax credit to push all three of these target

variables to their desired level.s. regardless o-f what

monetary policy is

doing. It may be that the more serious

coordination problem is getting the disparate elements of the

fiscal

team to work together.

On the other hand, it would seem that uncertainty about

which policies are best is pervasive in these days of

macroeconomic agnosticism. Debates over the appropriate

goals for policy and the effects of policy changes on the

PAGE 29

economy are perhaps more heated now than at any time since

the early days of the Keynesian revolution. While my own

feeling is that the extent of contemporary agnosticism is not

quite merited by the evidence, this is a minority view. And

I rather doLlbt that we would want a constitutional convention

today to place all authority over macroeconomic policy in the

hands of either the devoutly supply— side administration or

the putatively monetarist Federal Reserve.

It seems unlikely that the model of a single, unified

monetary— fiscal authority is descriptive of actual policy

making arrangements in the United States. The only

econometric study of fiscal—monetary coordination in the U.S.

that I know of, by Coldfeld and myself (1976) some years ago

concluded that "the abstraction of a single authority

conducting stabilization policy in the United States is Just

that

——

an

abstraction with little or no empirical validity"

(p. 792). Using the MPS model to assess the effects of

policy on real GNP, we found a slight positive correlation

between the effects of fiscal and monetary policy over the

whole 1958—1974 period. But this was the net result of a

substantial positive correlation while Republican presidents

were responsible for fiscal policy and a negative correlation

during the Kennedy—Johnson years.

One final observation on the fully—coordinated case is

pertinent in this context. A single, unified policy maker

with an entire portfolio of fiscal and monetary instruments

PAGE 30

to manage may find it optimal to couple expansionary monetary

policy with contractionary fiscal policy or vice versa, Just

as an investor may find it optimal to buy one share long and

sell another short.

Thus the fact that we sometimes see fiscal and monetary

policy tugging aggregate demand in opposite directions is not

evidence that the two policies are uncoordinated. For

example, Figure 2 offered an example in which a properly

coordinated policy package requires contractionary fiscal

policy and expansionary monetary policy. While the example

is a simple one o-f

certainty

and an equal number o-f

targets

and instruments, the basic lesson is probably very robust and

holds ——

though

not so sharply —— in an uncertain world with

a shortage of instruments. It suggests that policy may

sometimes appear uncoordinated when it is not.

This point is neither

academic nit—picking nor a

theoretical curiosum.. For example, the policy mix that many

economists advocate right now combines a more expansionary

monetary policy with a more contractionary fiscal policy in

the coming years. This is offered as an example of well—

coordinated monetary and fiscal policy while the current

policy mix (tight money with loose fiscal policy) is supposed

to illustrate lack of coordination.. Clearly, coordination

does not imply correlation.

B. TWO

UNCOORDINATED POLICY

MAKERS

At the

opposite end of the coordination spectrum comes

PAGE 31

the case of two independent authorities, one in charge of

fiscal policy and the other in charge of

monetary policy,

with neither one dominating the other. This model may

approximate actual policy making arrangements in the

contemporary United States. <10>

When the two policy makers are at loggerheads, a policy

mix of tight money and loose fiscal policy frequently

results, with deleterious effects on interest rates and

investment. <11> What outcome does theory lead us to expect

when fiscal and monetary policy are in different hands and

the two parties cannot (or do not try to) reach agreement?

A natural way to conceptualize this situation is as a

two—person non—zero—sum game. And a natural candidate for

what will emerge, it seems to me, is the Nash equilibrium.

<12> Why the Nash equilibrium? Both policy makers

understand that they do not operate in a vacuum.. Each

presumably understands that he is facing an intelligent

adversary with a decision making problem qualitatively

similar to his own. Furthermore, this is a repeated game;

each policy maker has been here before and assumes that he

will be here again.' It seems natural that each would assume

that the other'will make the optimal response to whatever

strategy he plays.

If so, each will probably play his Nash

strategy.

Let us see how the Nash equilibrium works out in a

moderately realistic example. (See the payoff matrix in

PAGE '32

Figure 5.)

I assume that each policy maker has two available

strategies: contraction or expansion.

I also assume that

they order the outcomes differently, but know each other's

preference ordering. Specifically, the fiscal authority

(whose preference ordering appears below the diagonal in each

box) is assumed to favor expansionary policy. From its point

of view, the solution where both play "expansion" is best

(rank 1) and the solution where both play "contraction" is

worst (rank 4). The monetary authority (whose ordering

appears above the diagonal) wants to contract the economy to

fight inflation, and so orders these alternatives in the

opposite way. However, as between the two outcomes which

combine expansion and contraction, I assume that the two

players agree that easy money with a tight budget is a better

policy mix than tight money with a loose budget.

This explains the entries in the payoff matrix (Figure

5). Now where is the Nash equilibrium? If the Fed plays

"expansion," the administration will also play "expansion,"

and the Fed will wind up with its least— preferred outcome

(the lower righthand box). So the Fed will play

"contraction." Knowing this, the administration's best

strategy is "expansion," so the outcome will be the lower

lef€hand box. Clearly, this is the only Nash equilibrium for

this game. It also seems to be the most plausible outcome o-f

uncoordinated but intelligent behavior.

But notice something interesting about this outcome.

;it L

—

—r

Page'

3?A

-

-

-H t

H

Cot'-

_

:i:

)':i

___ ——

___

-

_±J

___

4:11 ii

.

5

-

I

—

—-_-

i:ti1 1111

-t-

-

___

---4-—•--— —f— — —

IlL: II

__

LlI

-r-—r——r— ' —4----r-—y--H——---"--4---f—----T---

Tf—r --—•----— r—-r--—-L--

--.-—-±--

I

__

-

:::

LT

-

—

-

_t

-l

—.-—

. .

...—.——.

PAGE 33

Both the Fed and the fiscal authority aQree that the upper

righthand box ——

easy

money plus tight fiscal policy ——

is

superior to the Nash equilibrium. Under full monetary—

fiscal coordination, they might well select this policy mix.

But, if they cannot reach an agreement, then the Nash

equilibrium ——

a Pareto— inferior outcome ——

is

likely to

arise. Here is a case in which some degree of coordinatian

——

at

least enough to avoid the inferior Nash equilibrium ——

is

better than none even if we cannot decide which authority

has the right social welfare function. <13>

If this example is

typical, then switching from a system

of two uncoordinated policy makers to one with a single,

unified policy maker miçht yield substantial gains. And

there is good reason to think that it is typical, because

Nash equilibria in two—person non— zero— sum games are very

often not Pareto optimal.

The problem, of course, is that achieving greater

coordination is more easily said than done. The two

authorities have reasons for disagreeing ——

reasons

which may

not be easily ironed out. However, this example illustrates

that full coordination (which is probably impossible in any

case)

may not be critical. What we need in this case is no

more than an agreement to consult with one another enough to

avoid outcomes that both parties view as inferior. Maybe

this is not too much to ask.

However,

things become far less

clear if one

policy

FAGE 3Lt

maker lacks knowledge of either the preferences or the

economic model of the other. Then there is no particLilar

reason to think the Nash equilibrium will result, and other

solutions become equally plausible. For example, each player

may simply pursue his global optimum, ignoring the decision

c-f the other. <14> There are other possibilities as well.

C. LEADER—FOLLOWER ARRANGEMENTS

An alternative model of fiscal—monetary coordination,

intermediate between the two extremes, is a leader— follower

arrangement according to which policy maker A goes first nd

then policy maker B decides what to do in view a-f the prior

decision by A.

This scenario may sound moderately descriptive of

current U.S. institutions in that fiscal policy first

determines the budget deficit and then monetary policy

decides how mLch of this deficit to monetize. However,

things are a bit more complicated because monetary policy

decisions are made much mare -frequently (monthly?) than

fiscal policy decisions (annually?), so sometimes the Fed is

the leader.

Under a leader—follower arrangement, the follower runs

the show, albeit subject to same constraints placed on him by

the leader's prior decision.

If the follower has enough

instruments at his disposal, these constraints may not be

binding.

In this case, the leader—follower system is

PAGE 3 5

equivalent

to having a single stabilization

authority

(the

follower). But if the follower does not have enough

instruments, then the constraints imposed by the leader are

real ones and may preclude the attainment of the (follower's)

first—best optimum.

For this reason, the leader—follower system may work

very differently depending on whether the Fed or the

government is the leader.

I have noted above that, at least

in principle, a fiscal authority interested in targetting y,

P, and I/V can achieve its aims regardless of what monetary

policy does. Under these ideal circumstant:es, the leader—

follower system with the Fed as

leader is

equivalent to

giving

full control to the fiscal authorities.

However, the central bank enjoys no such luxury. Its

three traditional instruments (reserve requirements, open

market operations, and discount policy) probably give it only

one independent instrument for stabilization purposes. If

so, a leader— follower arrangement with the Fed as follower

is not at all equivalent to vesting full control in the Fed.

This asymmetry, it seems, is something of which the Fed is

fully aware. It may be why Chairman Volckersmiles so

infrequently.

Even without this asymmetry, the outcome will depend on

who leads and who follows. Suppose, first, that the fiscal

authority is the leader. It

sets government spending, taxes,

and transfers where it

wants them, in full knowledge that

PAGE 36

these decisions will evoke some response from the Fed.

In

the case of the simple game in Figure 5, the administration

can predict with confidence that the Fed will play

"contraction" regardless of

the

fiscal—policy decision. So

it will surely

play "expansion." We

get the Nash equilibrium

once again.

By a similar line of reasoning, it is easy to see that

the same Nash equilibrium will arise if the Fed is the leader

and the administration is the follower. However, this is not

a general result. In general, the two leader—follower

solutions are different, and each differs from the

Nash

equilibrium <15>.

Under a leacier—follcwer arrangemEnt, the follower's

attitudes clearly influence the leader's decision because

when the leader makes his decision he takes into account the

anticipated response of the follower. For example, -Fear of

the high interest rates that the Fed might cause probably led

Congress to adopt a less expansive budget this year than it

otherwise would have chosen.

In a dynamic framework, still more possibilities for

policy interactions arise. The -follower knows, for example,

that his decision in period 1 will influence the

circumstances facing, and thus the decision made by, the

leader in period 2. He will probably take this into account

in making his period 1 decision. <16> At least potentially,

this dynamic interaction can reduce the loss from lack of

PAGE 37

coordination by getting the leader to adopt policies more in

tune with the objectives of the follower.

Continuing the

same example, by keeping a tight rein on credit the Fed

exercises a kind of discipline (albeit a minor one) over

fiscal policy so long as Congress abhors high interest rates

and believes that deficits will not be monetized at the

margin. This pushes fiscal decisions more in the direction

favored by the Fed. The follower is not a toothless tiger

even i-f he has but one instrument and many targets.

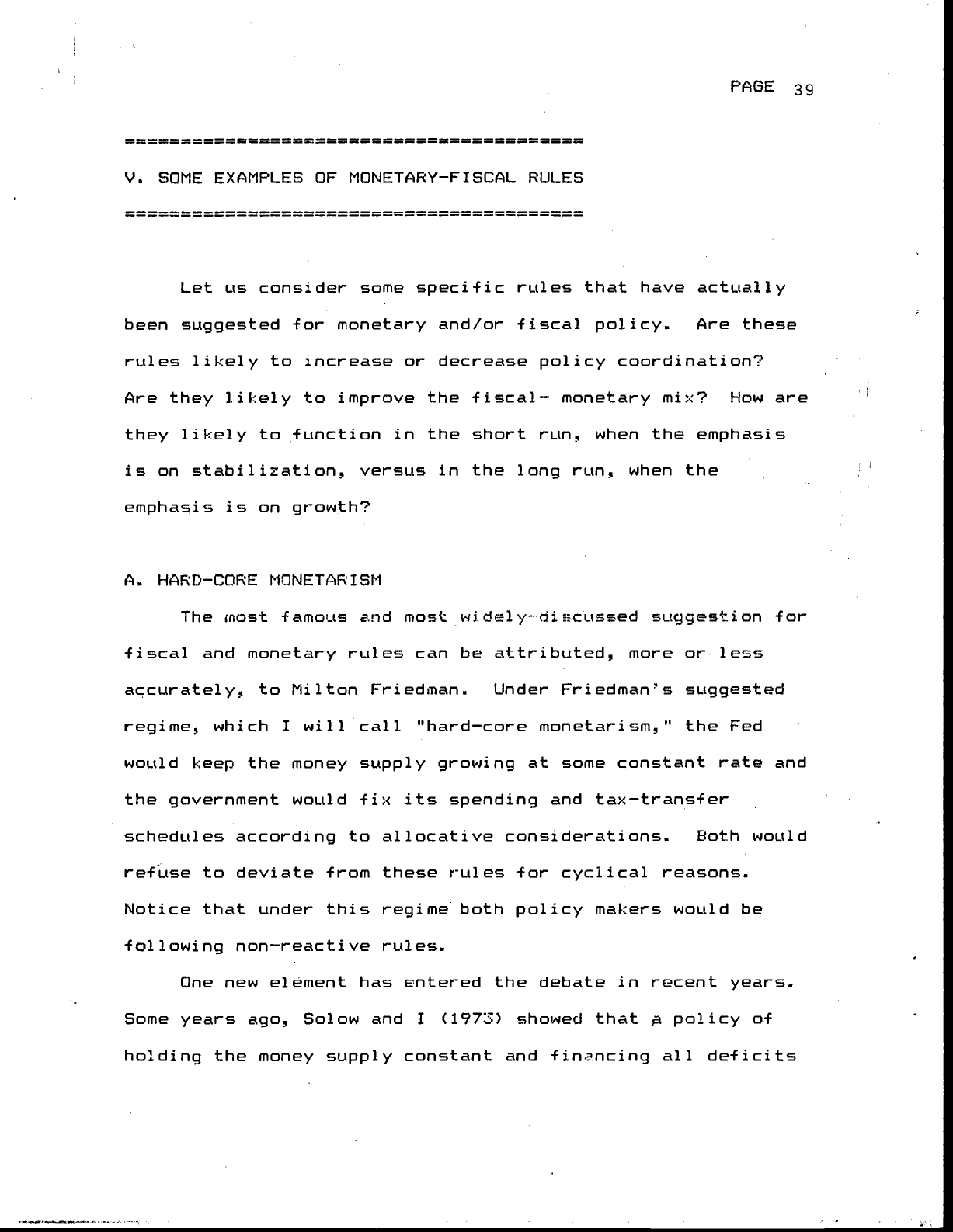

D. ONE PARTY FOLLOWS A NON—REACTIVE RULE

One way for the leader to avoid being manipulated by the

folJ.ower is to adopt a non—reactive policy rule such as the

famous k—percent rule for monetary policy. The key word here

is not "rule," but "non—reactive."

If the Fed (the follower)

knows that the government (the leader) is following a fiscal

rule that reduces spending whenever interest rates rise, it

can induce the government to cLit

spending by pushing up

interest rates. But no such possibilities arise if the

government follows a non—reactive rule..

While many fiscal rules (balancing the budget, balancing

the high—employment budget, etc.) have been suggested, none

of them seem to be non—reactive. No one, to my knowledge,

has advocated a k—percent rule -for government spending or for

tax receipts, though some o-F the suggestions for

constitutional restraints on spending come close.. <17>

PAGE 38

However, the most frequently suggested rule for the

conduct of

monetary

policy is non—reactive. And the desire

to free the Fed from the pressure to monetize bLidget deficits

may be one of the major motivations behind this rule.

If one policy maker follows a non—reactive rule, then

policy is ——

by

definition ——

perfectly

coordinated. One way

to think about non—reactive rules is as a way to give up some

freedom of action (the loss of one or more stabilization

policy instruments) in return for greater policy

coordination. If

the

non—coordination problem is big enough,

it may actually make sense to do this. To extend a well—worn

metaphor, if one o-F

your

hands will simply fight with the

other, it really may be better to tie one hand behind your

back.

PAGE 39

V.

SOME EXAMPLES OF MONETARY—FISCAL RULES

Let us consider some specific rules that have actually

been suggested for monetary and/or fiscal policy.. Are these

rules likely to increase or decrease

policy

coordination?

Are they likely to improve the fiscal— monetary mix? How are

they

likely to

function in the short rung when the emphasis

is on stabilization, versus in the long run when the

emphasis is on growth?

A. HARD—CORE MONETARISM

The most famous and most

widely—discussed suggestion for

fiscal and monetary rules can be attributed, more or less

accurately, to Milton Friedman. Under Friedman's suggested

regime, which I will call

"hard—core monetarism," the Fed

would keep the money supply growing at

some constant rate and

the government would fix its spending and tax—transfer

schedules

according to allocative considerations.. Both would

refuse to deviate from these r-ules for cyclical reasons.

Notice that under this regime both policy makers would be

following non—reactive rules..

One new element has entered the debate in recent years..

Some years ago, Solow and I (197.) showed that

policy of

holding the money supply constant and financing all deficits

PAGE 40

by issuing bonds could destabilize the economy, whereas

•financing deficits by money creation probably led to a stable

system. This finding, while derived in a very simple and

special case with fixed prices, has proven to be remarkably

rc,bLIst. Tobin and Buiter (1976) established a parallel

result for a full—employment economy with perfectly flexible

prices. Pyle and Turnovsky (1976) and others showed that

analogous results obtain in models intermediate between these

two extremes such as models with an expectations— augmented

Phillips curve.

Recently, McCallum (1981, 1982), Smith (1982) and

Sargent and Wallace (1981) have re—emphasized the importance

of this result for the hard—core monetarist policy rule.

Though using rather different models, each has made the same

point: that the system is liable to be dynamically unstable

under a policy that holds both fiscal policy (defined in

various ways by the different authors) and the money supply

(or its growth rate) constant.

The mechanism behind these results is not hard to

understand. Suppose some shock (such as an autonomous

decline in demand in a Keynesian model) opens up a deficit in

the government budget, and the hard—core monetarist regime is

in force. Bonds will be issued to finance the deficit. With

both interest rates and the number of bonds increasing,

interest payments on the national debt will be increasing.

But this increases the deficit still further, requiring even

PAGE i

larger

issues o-f bonds in subsequent periods, and the process

repeats..

I-f the real rate of interest exceeds the rate o-f

population

growth, then the real

supply of bonds per capita

will

grow

without limit. Consequently, unless bonds are

totally irrelevant to other economic variables (as in the

non— Ricardian view o-f Barro (1974)), the whole economy will

explode. <18>

So the stabilizing properties of the hard—core

monetarist rule are open to serious question, to say the

least. What

about its longer—run

effects?

As a long—run defense against inflation, the monetarist

rule seems to be very e-ffective.. Although academic

scribblers can, and have constructed examples of continuous

inf].aton without money growth, my feeling is that policy

makers can justifiably treat these models as intellectual

curiosa and proceed on the assumption that a maintained money

growth rate will eventually control th rate of inflation.

But what about capital formation and real economic

growth? When a recession comes, the hard—core monetarist

rule takes no remedial

action.

I-f there is an important

accelerator aspect to investment spending, the slack demand

will retard capital formation. At the same time, the

issuance c-f new government bonds to finance the budget

deficits that recession brings will push up interest rates.

And this, too, w-ill retard invesment spending. The likely

result is

that

hard—core monetarism will not create a climate

PAGE

conducive to investment unless long—run predictability of the

price level is a more important determinant of investment

than I think it is. <19>

It seems to me that much of

the

concern over fiscal—

monetary coordination derives from concern over the

implications of the policy mix for investment. If so, then

hard—core monetarism, which eliminates the coordination issue

by eliminating policy, does not look to be a very good

sol ut i on.

B. BONDISM

As McCallum (1981) first pointed out, a potentially

better monetary—fiscal rule was actually suggested by

Friedman in his earlier 'A Monetary and Fiscal Framework -for

Economic Stability" (1948), but subsequently abandoned. For

lack of

a

better name,

Gary

Smith (1982) has suggested that

-we call the policy "bondism" because it treats bonds in much

the same way as monetarism treats money.

Under the old Friedman policy, both fiscal and monetary

policy

would be governed by rules, but the monetary rule

would be

reactive. In particular, Friedman suggested that

government

spending and tax rates

be

set in accordance with

allocative

considerations, as in the monetarist rule, but

that all deficits be financed by money creation. Both

McCallum (1981, 1982) and Smith (1982) observed that this

policy regime is equivalent to. the "money financing" scenario

I-

PAGE '43

in Blinder and Solow (1973), and hence probably leads to a

stable system. On this score alone, it has much to recommend

it over monetarism.

But there is more to the story. Consider what would

happen when, for example, a deficiency o-F

aggregate

demand

brought on a recession. Falling incomes would open up a

budget deficit, and this would automatically induce the Fed

to open the monetary spigots. The economy would get a strong

anti—recessionary stimulus from monetary policy. And I do

mean strong. Think about the empirical magnitudes involved.

In the current U.S. economy, a 1 percentage point rise in the

unemployment rate adds about $25 billion to the budget

deficit. But the "money" that would be issued to finance the

deficit would be high—powered money. Adding $2 billion in

new bank reserves is a colossal injection of money; it would

increase total bank reserves by nearly 50 percent! Thus the

old Friedman rule would seem to be an incredibly powerful

stabilizer. <20>

How does it score on the more long—run criteria? The

fact that recessions would automatical

1 y engender easy money

under the "bondist" policy augurs well for capital formation.

So does the notion that cyclical disturbances would probably

be quite muted. The one potential worry is over inflation.

The rule can concEivably lead to a lot of money creation in a

hurry, with subsequent inflationary consequences. But i-f the

fiscal part o-f the rule keeps the high—employment budget

PAGE '4

balanced, and if the economy fluctuates around its high—

employment norm, this should not be a major worry. Monetary

expansions should subsequently be reversed by monetary

contractions. <21> If the rule is believed, even large

injections of money should not raise the spectre of secular

inflation.

Finally, note that the old Friedman rule completely

eliminates the possibility that monetary and fiscal policy

might act at cross pLirposes. Under the rule, monetary policy

is expansionary if and only if fiscal policy (defined by the

automatic stabilizers) is expansionary. Also, the game—

theoretic considerations raised in Section III cannot arise

because neither policy maker has any decision to make.

While I have never been an advocate of rules, it seems

to me that all this adds up to a clear conclusion: the old

Friedman rule ought to get serious quantitative attention.

C. SOFT—CORE MONETARISM

The rule just discussed would make fiscal policy non-

reactive and monetary policy reactive. A symmetric approach

would call for a rule in which monetary policy is non—

reactive but fiscal policy reacts in a counter—cyclical

fashion.

John Taylor (1982a) has mentioned just such a

possibility as a way to put a meaningful counter— cyclical

policy regime in place without creating expectations that

inflationary shocks will be accommodated. Under this regime,

PAGE L5

monetary

policy would adhere to a k—percent rule., but fiscal

policy would be used for counter—cyclical purposes. The

latter could be done either by rules or by discretion.

What can we say about this policy regime? Not much., of

course! until it has been given more theoretical and

empirical scrL(tiny. But a few observations can be made.

First, the coordination problem is de-Finitionally

solved. With no monetary pOlicy, it can hardly be in

opposition to fiscal policy. Second, the game—theoretic

aspects of stabilization policy would necessarily disappear.

The government could hardly try to "game" a k—percent rule.

Would cyclical stabilization be strong enough? That

cannot be answered in the abstract, since Taylor's policy mix

does not specify the strength of the fiscal stabilizers. But

it does not seem likely that they vould be as strong as the

stabiliz.ing

forces in Friedman's "hondist" rule.

Finally, there is the long—run capital formation issue.

Reducing the severity of recessions, I believe, can only do

good things for investment. But doing so with fiscal policy

probably means that interest rates would be pushed up by the

counter—cyclical policy. <22> So there could conceivably be a

trade—off between short—run stabilization and long—run

growth.

Page i6

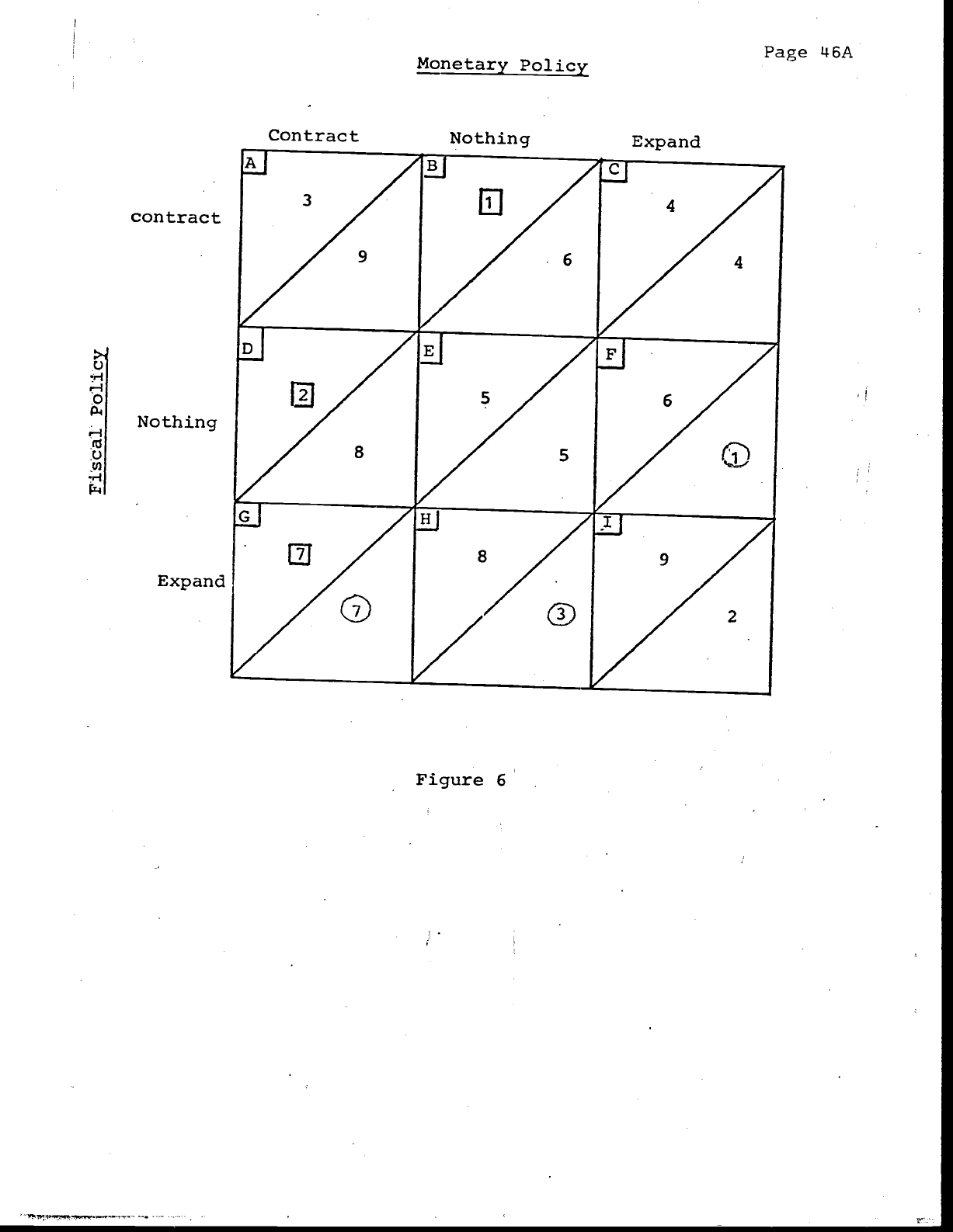

APPENDIX

This appendix considers a monetary-fiscal policy game in

which each authority has three strategies: to expand aggregate

demand, to contract aggregate demand, or to do nothing. The

outcomes are ranked from 1 to 9 in the payoff matrix in Figure 6,

with the rankings of the fiscal authority once again below the

diagonal and the monetary rankings above.

Circles indicate the best fiscal response to each monetary

strategy and squares indicate the best monetary response to

each fiscal strategy. It 1s clear that box G, in the lower

lefthand corner, is the only Nash equilibrium. As in the

2 by 2 example in the text, monetary policy is contractionary

and fiscal policy is expansionary. We can also see that the

Nash equilibrium is Pareto dominated by a variety of other

outcomes: boxes B, E, C, and F.

If the Fed is the leader and the government is the follower,

the solution is box F; this is the best the Fed can do if

constrained to the fiscal reaction function (the boxes with

circles). By similar reasoning, we see that box B will arise

if the government leads and the Fed follows. In this example

either leader-follower equilibrium is superior to the Nash

equilibrium (though the leader has more to gain).

Another possible outcome of complete lack of coordination is

that each authority ignores the other and shoots for its

global optimum. In the example, that would mean that each

does nothing and box E results. This outcome Pareto dominates

the Nash equilibrium, but is in turn Pareto dominated by box

C (in which fiscal policy is contractionary while monetary

policy is expansionary).

0

.0

I-I

fitS

.0

Cl)

n-I

[t4

Monetary Policy

Page 6A

contract

Nothing

Expand

Figure 6

PAGE 7

FOOTNOTES

1. The irony of having such a subtle policy mix advocated by

those who deride "fine tuning" is almost overwhelming.

2 The former has been stressed by, among others, Christ

(1968) and Blinder and Solow (1973). The latter has been

stressed by, among others, Auerbach and Kotlikoff (1981) and

Sargent and Wallace (1981).

3. The stability of the economy under this last policy has

been called into question. More on this later.

4. For a more detailed discussion of this issue, see

Feldstein (1982).

.

Indeed,

under the hypothesis advanced by Barro (1974) ——

that

each generation has an operative bequest motive based on

the next

generation's lifetime utility ——

the

period from now

to the end o-F time is relevant.

6. See, for example, Blinder (1981), Hall and Mishkin (1982),

Hayashi (1982), or Mankiw (1981). Bernanke (1981) is more

optimistic about the PIH.

7. For an interesting discussion of forward—looking versus

backward—looking wage contracts, and how we might distinguish

between them empirically, see Taylor (1982b).

8. Divergent expectations have been emphasized recently by,

among others, Phelps (1981) and Frydman (1981).

9. It is hard to conceive of the other roLte: putting all the

fiscal policy instruments in the hands of the central bank.

10.

In

reality, things are more complicated still because

the President and Congress often disagree over national

economic policy. A model of three stabilization authorities

may be better.

11. The opposite policy mix ——

tight

budgets and easy money

——

while

conceivable, seems to be rarely encountered.

12. The Nash equilibrium concept is defined as follows. Each

player does what he would if he knew what the other player

was going to do.

It is an equilibrium in the sense that the

two resulting strategies are consistent with one another;

once the game is played, neither player has any desire to

change his decision. Not all games have a unique Nash

equilibrium. The fiscal— monetary game

to be considered here

PAGE'8

does.

13. The example analyzed here is a case of what game

theorists call the Prisoners' Dilemma..

14. In the simple example of Figure 5. this pair of

strategies also leads to the Nash equilibrium. But this is

not generally true. A more complicated example in which the

Nash and other alternative solutions differ is offer-ed in the

Appendix.

15. See the example in the Appendix.

16. And, a-F

course,

the leader understands this when he makes

his period 1 decision! No wonder game theory is so hard.

17. Indeed, it may be possible to view the Reagan economic

program as a non—reactive fiscal rule that will cut the

ratios a-f government spending and tax recipts to GNP

regardless a-f the consequences for interest rates,

unemployment, and inflation.

18. In a complex system, many mare things are going on than I

can describe in a single paragraph. For example, income and

prices are changing, with important consequences -for the

budget deficit. Yet the basic mechanism described here seems

to come shining through in all the models.

19.

Or unless inflation itself is damaging to investment

via, for example, the deterioration of the real value a-f

depreciation allowances. Thi.s last factor has been stressed

in a number o-f places by Feldstein. See, among others,

Feldstein (1980b).

20.

Maybe

too powerful. This exercise in casual empiricism,

in conjunction with the fact that the effects a-f high—powered

money on income come with a distributed lag, raises worries

that the rule might acti.tally destabilize the economy by

over—reacting to disturbances. The theoretical papers

mentioned earlier deny this possibility, but they ignore

distributed lags. The issue seems worth investigating.

21. This statement is predicated on defining high employment

as approximately the natural rate. With a

Humphrey—Hawkins

type definition of high employment, the old Friedman rule can

lead to inflationary disaster.

22. This could be avoided if expansionary fiscal changes

took the -form, say, a-f liberalizing depreciation allowances

or raisjnQ the investment tax credit. But the personal

income tax and certain government expenditures appear to be

the prime candidates to bear the stabilization burden.

Page 9

REFERENCES

Alan J. Auerbach and Laurence J. Kotlikoff, "National Savings,

Economic Welfare, and the Structure of Taxation," NBER