GUIDANCE on the UK Regulations

(May 2008) implementing the Unfair

Commercial Practices Directive

© Crown copyright 2008

This publication (excluding the OFT and BERR logos) may be

reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it

is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The

material must be acknowledged as crown copyright and the title of

the publication specified.

Guidance on

the Consumer

Protection

from Unfair

Trading

Regulations

2008

CONTENTS | 1

CONTENTS

CHAPTER PAGE

1 Using the Guidance 2

PART 1

2 Introduction 7

3 The CPRs – an overview 9

4 Scope 13

5 Assessing unfairness 16

PART 2

6 Banned practices (Schedule 1) 20

7 Misleading practices (Regulations 5 and 6) 28

8 Aggressive commercial practices (Regulation 7) 40

9 Promoting unfair practices in codes of conduct

(Regulation 4) 44

10 General prohibition of unfair commercial practices

(Regulation 3) 46

PART 3

11 Compliance and enforcement 50

12 Criminal offences 55

13 Investigative powers 59

PART 4

14 Glossary 63

ANNEX

A Illustrative examples 71

B Effect on UK law 77

C List of contacts 81

2 | PART 1 | USING THE GUIDANCE

CHAPTER 1

USING THE GUIDANCE

AIM OF THE GUIDANCE

1.1 This Guidance is principally intended to help traders to

comply with the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading

Regulations 2008 (CPRs). It will also be of use to enforcers,

and to consumer advisors in understanding what actions are

prohibited. The Guidance sets out the views of the Office

of Fair Trading (OFT) and the Department for Business,

Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR). It seeks to

illustrate how the CPRs may apply in practice. Ultimately,

however, only the courts can decide whether or not a

commercial practice is unfair within the meaning of the

CPRs. This Guidance should not be regarded as a substitute

for, or definitive interpretation of, the CPRs and should be

read in conjunction with them.

1.2 The examples used in this Guidance seek to illustrate the

possible effect of the CPRs. They do not cover every situation

or practice in which a breach of the CPRs may occur.

USING THE GUIDANCE | PART 1 | 3

HOW TO USE THE GUIDANCE

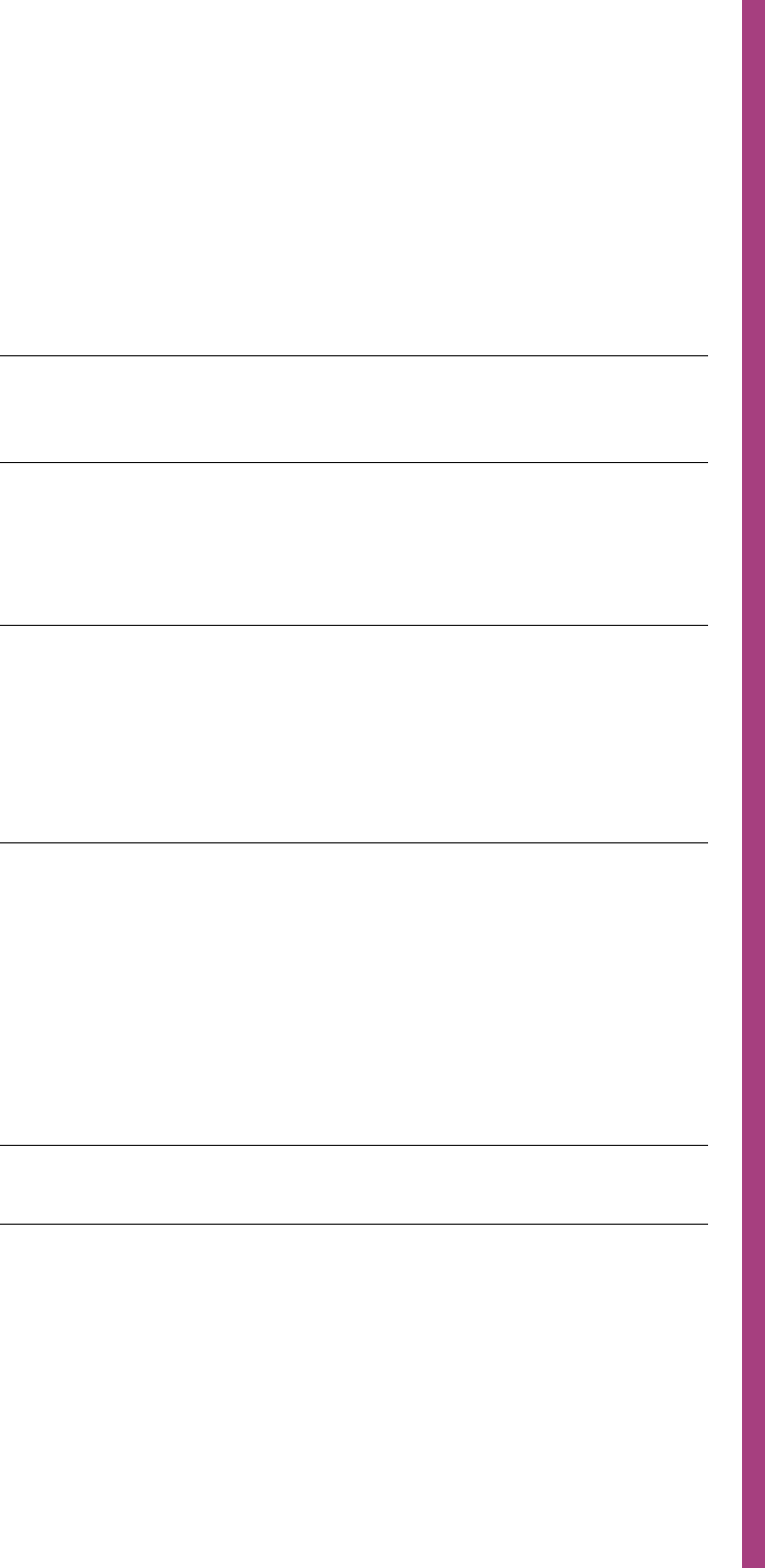

1.3 This Guidance is split into four parts. Part 1 contains an

introduction and a short overview, including a description

of the scope of the CPRs. There is a also a flowchart to help

the reader assess whether commercial practices are unfair

under the CPRs.

1.4 Part 2 deals with what is prohibited by the CPRs in more

detail. It explains the prohibitions in the order which we

consider it most helpful to approach them, starting with

the specific prohibitions, then covering misleading and

aggressive practices and finally the general duty not to trade

unfairly.

1.5 Part 3 provides information on compliance, enforcement,

offences, and investigative powers.

1.6 Part 4 starts with a glossary of terms. These terms are

printed in bold type throughout the Guidance. They refer

to key concepts such as ‘transactional decision’. The

glossary discusses the concept of the ‘average consumer’

in some detail. Note that illustrative examples can be found

throughout the text in italics.

1.7 Also in Part 4, the Annexes to the Guidance contain some

examples which show how an assessment against the

prohibitions might work in practice, and information about

changes to those legislative measures that were repealed or

amended by the CPRs. Finally, there is a list of contacts and

references where further information can be found.

1.8 A diagram illustrating the key provisions and structure of the

Regulations is given below. See Chapter 3 for a more detailed

summary of the different prohibitions.

4 | PART 1 | USING THE GUIDANCE

Unfair if

they cause

consumers

to take a

different

decision

Always

Unfair

BANNED PRACTICES

31 SPECIFIC PRACTICES

(BANNED IN ALL CIRCUMSTANCES)

MISLEADING PRACTICES AGGRESSIVE

PRACTICES

OMISSIONSACTIONS

GENERAL PROHIBITION

(CONTRARY TO THE REQUIREMENTS

OF

PROFESSIONAL DILIGENCE)

USING THE GUIDANCE | PART 1 | 5

PART 1

6 | PART 1 | USING THE GUIDANCE

CHAPTER 2

INTRODUCTION

1 Statutory Instrument 2008/1277

2 Directive 2005/29/EC.

The Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations

2.1 The Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations

2008 (CPRs)

1

, came into force on 26 May 2008, and

implemented the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive

(UCPD) into UK law.

2

2.2 The UCPD aims to harmonise the legislation across the

European Community preventing business practices

that are unfair to consumers, so as to support growth of

the internal (European) market. Uniform law about unfair

commercial practices will make it easier for traders based

in one Member State to market and sell their products

to consumers in other Member States. It will also give

consumers greater confidence to shop in the UK, and across

borders, by providing a high common standard of consumer

protection.

2.3 The UCPD’s broad scope means that it tackles many

issues already covered by existing laws. In order to avoid

duplication, and so as to modernise and simplify the UK’s

consumer protection framework, the CPRs partially or

wholly repeal provisions in 23 such laws. Twelve of these

laws are repealed outright, including for instance Part III

of the Consumer Protection Act 1987. Eleven are repealed

in part, including most of the Trade Descriptions Act 1968.

The CPRs provide similar or greater protection to these laws.

See Annex B for further details on changes to previously

existing law.

2.4 The CPRs apply to commercial practices before, during

and after a contract is made. The CPRs contain a general

prohibition of unfair commercial practices and, in

particular, contain prohibitions of misleading and aggressive

commercial practices. They also prohibit 31 specific

commercial practices that are listed in chapter 6 on banned

practices. These prohibitions are explained in more detail in

Part 2 of the Guidance.

2.5 Broadly speaking, if consumers are treated fairly, then

traders are likely to be complying with the CPRs. This means

that fair-dealing businesses should not have to make major

changes to their practices. However, if a trader misleads,

behaves aggressively, or otherwise acts unfairly towards

consumers, then the trader is likely to be in breach of the

CPRs and may face action by enforcement authorities.

Details of potential enforcement action (both civil and

criminal enforcement is possible under the CPRs) can be

found in Part 3 of the Guidance.

8 | PART 1 | INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 3

THE CPRs –

AN OVERVIEW

3.1 The CPRs consist of:

• ageneralprohibitionofunfaircommercial practices,

• prohibitionsofmisleadingandaggressivepractices,

and

• 31practicesprohibitedinallcircumstances.

These prohibitions, and the scope of the CPRs, are

summarised below. Further explanation appears in the

following chapters and in the glossary.

2 SCOPE

3.2 The CPRs apply to any act, omission and other conduct by

businesses directly connected to the promotion, sale or

supply of a product

3

to or from consumers (whether before,

during or after a commercial transaction, if any). They do not

apply when only consumers are involved in a transaction.

Most commercial practices covered by the CPRs will

involve a direct relationship between businesses (that is,

‘traders’) and consumers. However there may be instances

where the commercial practice could have a sufficiently

close connection with consumers as to fall within the scope

of the CPRs, even though the trader himself does not deal

directly with consumers.

4

3 GENERAL PROHIBITION

3.3 Regulation 3 contains a general prohibition of unfair

commercial practices.

3.4 A commercial practice is unfair if:

• itisnotprofessionally diligent, and

• itmaterially distorts, or is likely to materially distort,

the economic behaviour of the average consumer.

Essentially, for the general prohibition to apply, the trader’s

practice must be unacceptable when measured against an

objective standard and must also have (or be likely to have) an

effect on the economic behaviour of the average consumer.

The second condition is likely to be met if, for example,

because of the practice, the average consumer would buy a

product they would not otherwise have bought, or would not

exercise cancellation rights when otherwise they would have

done so.

MISLEADING AND AGGRESSIVE PRACTICES

3.5 Regulations 5-7 of the CPRs prohibit commercial practices

which are misleading (whether by action or omission) or

aggressive, and which cause or are likely to cause the

average consumer to take a different decision.

3 This has a wide meaning – see the box at the end of this

chapter.

4 See chapter 4 on Scope.

10 | PART 1 | THE CPRS – AN OVERVIEW

PRACTICES PROHIBITED IN ALL CIRCUMSTANCES

3.6 Schedule 1 to the CPRs lists 31 commercial practices

which are unfair in all circumstances and are prohibited.

The CPRs use ‘product’ to refer to goods and services in a wide

sense, including immovable property, rights and obligations. The

prohibitions apply to commercial practices relating to products

in this wider sense. It is important to note this because the

legislation they replace was in many cases narrower in scope,

for instance applying to just goods or services, for instance

applying to just goods and services. The Trade Descriptions Act

1968 applied to both goods and services but there were, different

sets of rules applied to goods and to services. The CPRs apply

in the same way to both goods and services, and also extend to

intangible rights such as cancellation or cashback options.

In the text of the Guidance we use ‘average consumer’ to refer

to each of three types of consumer (‘average’, ‘average targeted’

and ‘average vulnerable’). These concepts are explained in the

glossary. We use ‘take a different decision’ as shorthand for

‘take a transactional decision that he would not have taken

otherwise’. See the glossary entry for ‘transactional decision’

for more details.

THE CPRS – AN OVERVIEW | PART 1 | 11

IS THE PRACTICE

UNFAIR?

PRACTICE

IS UNFAIR

* In some situations (where an invitation to purchase is made) certain

specified information must always be provided unless apparent. (pages 35-39)

PRACTICE IS NOT UNFAIR

Practice not

caught by CPRs

START

HERE

Might my

practice affect

consumers?

(pages 14-15)

Is what I am doing

prohibited outright

(see list of 31

practices)?

(pages 21-27)

Am I giving false

information to,

or deceiving, my

customers?

(pages 29-33)

Or

Am I failing to

give important

information about

a product?*

(pages 33-35)

Or

Am I acting

aggressively?

(pages 41-43)

Am I failing to act

in accordance with

the standards a

reasonable person

would expect?

(pages 47-48)

Does my practice

cause, or is it

likely to cause,

the average

consumer to

take a different

decision about

any products or

related decisions

(including

cancellation)?

(pages 68-70)

12 | PART 1 | THE CPRS – AN OVERVIEW

CHAPTER 4

SCOPE

PRACTICES AFFECTING CONSUMERS

4.1 Broadly the CPRs apply to practices that may affect

consumers. The CPRs sit alongside the other protections

for consumers. In particular, the existing system of contract

law, including the law on unfair contract terms, remains

unchanged by the CPRs.

4.2 The CPRs apply to commercial practices that can

be described as ‘business to consumer’. These are

acts or omissions by a trader, directly connected with

the promotion, sale or supply of a product to or from

consumers. Products include goods and services, rights

and obligations, and range from simple products like an item

of clothing to the services involved in complex processes

such as buying a house.

4.3 Whilst most commercial practices will occur where a

trader deals directly with consumers, any commercial

practice that has the potential to affect consumers may

need to be assessed against the prohibitions in the CPRs.

For example where a trader sells a product to a consumer,

acts or omissions which occur further up the supply chain

may also constitute commercial practices.

4.4 The CPRs apply to commercial practices that occur

before, during and after a transaction, if any. Examples of

commercial practices that occur following a transaction

include actions related to debt collection,

5

after-sales

services, and the cancellation of an existing contract. This

is because these practices are directly connected with the

sale or supply of a product.

5 Although it is important to note that whilst the way in

which debts are enforced or collected may lead to unfair

commercial practices by the trader or his agents this

does not of itself enable consumers to refuse to pay

legitimate debts.

14 | PART 1 | SCOPE

6 Statutory Instrument 2008/1276

7 Other legislation also applies to the labelling of food

products. Traders must comply with all relevant legislation,

not just the CPRs.

Examples:

OUTSIDE SCOPE (not covered by the CPRs)

1. Business to business practices with no potential to affect

consumers

A trader sells specialist tractor parts to businesses only.

As consumers do not buy his products, the trader does not

need to consider compliance with the CPRs. The trader may

need to consider the Business Protection from Misleading

Marketing Regulations 2008.

6

IN SCOPE (covered by the CPRs)

2. Business practices with the potential to affect both

consumers and businesses

A trader sells spare computer parts over the internet. He sells

a range of different products. The trader needs to consider

compliance with the CPRs if consumers may buy the products.

3. Any aspect of a business to business practice that is directly

connected to the sale of a product to consumers.

A trader makes and sells processed cheese slices to

supermarkets. Although the trader does not sell directly to

consumers, any labels he produces must be compliant with

the CPRs as they are directly connected with the promotion

and sale of the cheese slices to consumers.

7

4. Practices by a trader where he purchases a product from

the consumer

A trader makes statements about the value of a car he

intends to purchase from a consumer. These statements

would need to comply with the CPRs. This does not preclude

haggling over the value of the product, but does cover

misleading statements and other unfair practices (by the

trader) engaged in as part of this process.

A trader who is an expert on Chinese pottery tells a

consumer that a Ming vase she wants to sell to him is a

fake. If this was not the case the statement would be likely to

amount to a misleading action.

A trader offers to buy scrap metal from a consumer and

offers £10 a kilo. He states that the metal offered weighs

5 kilos, whereas it actually weighs 9. This would be a

misleading action.

SCOPE | PART 1 | 15

CHAPTER 5

ASSESSING

UNFAIRNESS

CONDUCT AND EFFECT

5.1 There are 31 commercial practices listed in Schedule 1 to

the CPRs which, because of their inherently unfair nature,

are prohibited in all circumstances. Evidence of their effect,

or likely effect, on the average consumer is not required in

order to prove a breach of one of these outright prohibitions.

5.2 By contrast, for a commercial practice to be a breach of

the other two prohibitions mentioned above – the general

prohibition, and the prohibition on misleading and aggressive

practices – the trader must exhibit the conduct specified in

the prohibition, and the practice must have, or be likely to

have, an effect on the behaviour of the average consumer.

To assess the effect, or potential effect, of the conduct it is

necessary to consider the concepts of average consumer

and transactional decision, which are explained in the

glossary.

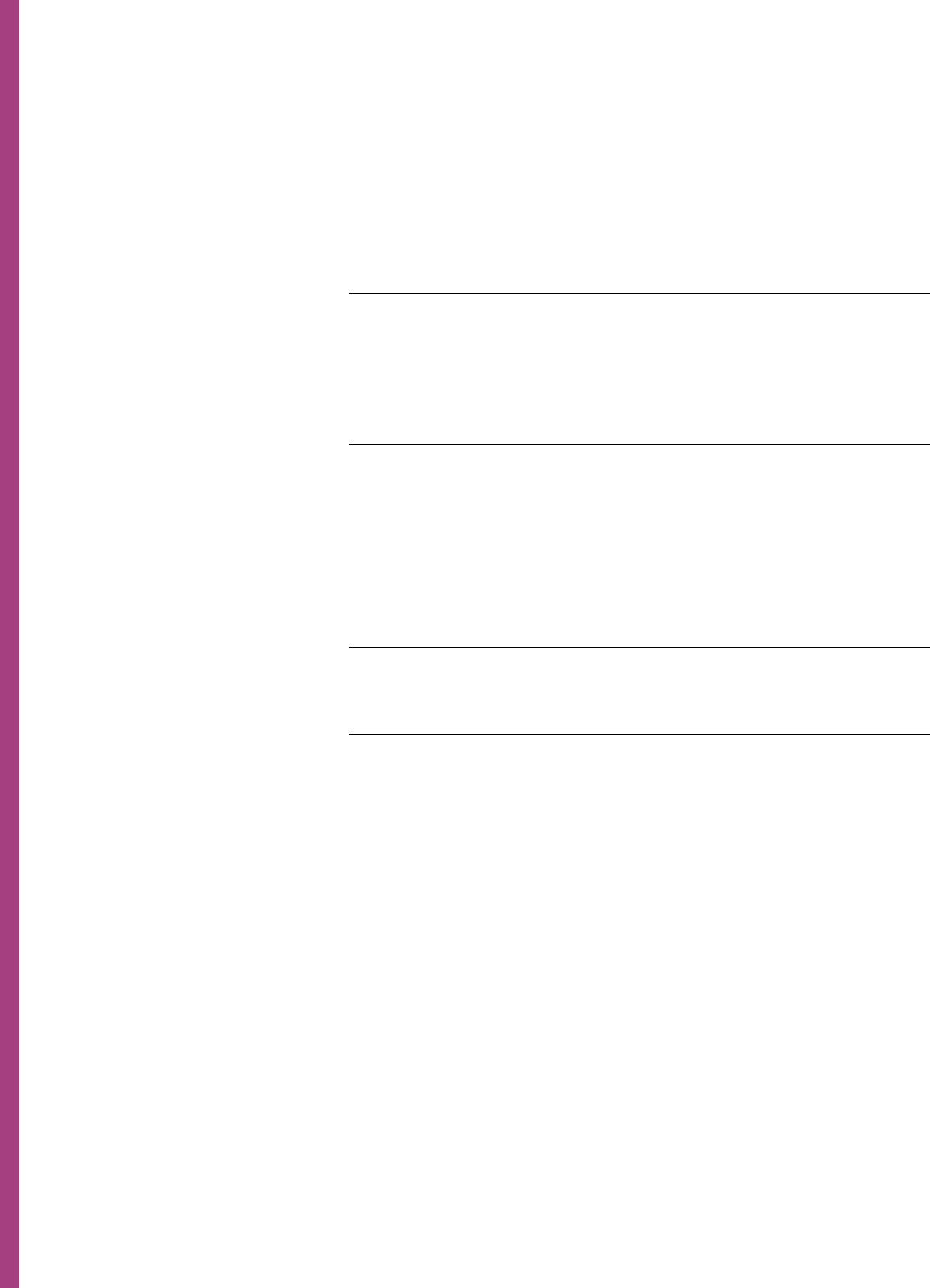

5.3 The table below summarises the type of conduct to

which each of the prohibitions can apply, and (where an

effect is needed) the effect on consumers that will make

such conduct unfair. Please see the relevant chapters for

explanations of the terms used in this table. The table refers

to the individual Regulations that make up the CPRs. Both the

conduct and effect ‘tests’ relevant to each specific Regulation

need to be satisfied before a practice can be considered

unfair under the CPRs by reference to that Regulation.

ASSESSING UNFAIRNESS | PART 1 | 17

18 | PART 1 | ASSESSING UNFAIRNESS

TABLE FOR ASSESSING

UNFAIRNESS

REGULATION 3

REGULATION 5

REGULATION 6

REGULATION 7

SCHEDULE 1

Contrary to the

requirements

of professional

diligence

False or deceptive

practice in relation

to a specific list of

key factors

Aggressive practice

by harassment,

coercion or undue

influence

Read across the page for the relevant conduct and effect ‘tests’ for each Regulation.

And

(Likely to) significantly

impair the average

consumer’s freedom of

choice or conduct

And as a result

DOES NOT APPLY

(No impairment or transactional

decision tests)

And

(Likely to) appreciably

impair the average

consumer’s ability

to make an informed

decision

And as a result

One of 31 specified

practices

Causes (or is

likely to cause)

the average

consumer to

take a different

(transactional)

decision

REGULATION CONDUCT EFFECT

Omission (or unclear/

untimely provision) of

material information

PART 2

CHAPTER 6

BANNED

PRACTICES

(SCHEDULE 1)

CHAPTER 6

BANNED

PRACTICES

(SCHEDULE 1)

OUTRIGHT PROHIBITIONS

6.1 Schedule 1 to the CPRs lists 31 commercial practices

which are considered unfair in all circumstances and which

are prohibited.

8

There is no need to consider the likely effect

on consumers. The text that follows lists these banned

practices and provides some illustrative examples in italicised

text. Breaches of these provisions may also breach the other

prohibitions in the CPRs.

(1) Claiming to be a signatory to a code of conduct when the

trader is not.

(2) Displaying a trust mark, quality mark or equivalent without

having obtained the necessary authorisation.

(3) Claiming that a code of conduct has an endorsement

from a public or other body which it does not have.

A member of the (voluntary) Pure Water Code displays the

code logo in his shop and on his advertising materials and

claims beside the logo that the code is ‘approved by the

Office of Fair Trading’. The code has not been approved. This

would breach the CPRs.

(4) Claiming that a trader (including his commercial

practices) or a product has been approved, endorsed

or authorised by a public or private body when the trader,

the commercial practices or the product have not or

making such a claim without complying with the terms

of the approval, endorsement or authorisation.

A plumber claims that he is CORGI-Registered

9

when he is

not. This would breach the CPRs.

(5) Making an invitation to purchase products at a specified

price without disclosing the existence of any reasonable

grounds the trader may have for believing that he will not

be able to offer for supply, or to procure another trader

to supply, those products or equivalent products at

that price for a period that is, and in quantities that are,

reasonable having regard to the product, the scale of

advertising of the product and the price offered (bait

advertising).

A camera firm advertises nationally using the line ‘Digital

cameras for £3’.

10

They had only ever planned to have a very

small number of such cameras available at that price. This

would breach the CPRs because the number of cameras

actually available for £3 would not be sufficient to meet the

likely level of demand arising from the scale of the advertising

and the trader knew this but failed to make clear in the

advertisement that only limited numbers were available.

8 The prohibition is contained in regulations 3(1) and 3(4)(d)

of the CPRs.

9 Council for Registered Gas Installers scheme.

10 For the purposes of this example assume it is an invitation

to purchase.

BANNED PRACTICES (SCHEDULE 1) | PART 2 | 21

(6) Making an invitation to purchase products at a specified

price and then:

(a) refusing to show the advertised item to consumers

(b) refusing to take orders for it or deliver it within

a reasonable time, or

(c) demonstrating a defective sample of it,

with the intention of promoting a different product (bait

and switch).

A trader advertises a television in his shop window for

£300.

11

When consumers ask him about it, he shows them a

model which does not work properly, and then refers them to

a different model of television. If the trader intentionally used

this practice to promote a different model (for instance one

offering a higher profit margin), it would breach the CPRs.

(7) Falsely stating that a product will only be available for

a very limited time, or that it will only be available on

particular terms for a very limited time, in order to elicit an

immediate decision and deprive consumers of sufficient

opportunity or time to make an informed choice.

A trader falsely tells a consumer that prices for new houses

will be increased in 7 days time, in order to pressurise him

into making an immediate decision to buy.

(8) Undertaking to provide after-sales service to consumers

with whom the trader has communicated prior to a

transaction in a language which is not an official language

of the European Economic Area State where the trader

is located, and then making such service available only

in another language without clearly disclosing this to

the consumer before the consumer is committed to

the transaction.

A trader based in the UK agrees to provide after-sales service

to a consumer with whom he has been communicating in

German. The trader then provides after-sales services only

in English, without warning the consumer pre-contract that

that would be the case. This would breach the CPRs.

(9) Stating or otherwise creating the impression that a

product can legally be sold when it cannot.

A trader offers goods for sale in circumstances in which the

consumer cannot legally become their owner by buying

them from him, for instance because they have been stolen

and he has no legal title to pass on. This would breach the

CPRs.

11 For the purposes of this example assume it is an

invitation to purchase.

22 | PART 2 | BANNED PRACTICES (SCHEDULE 1)

(10) Presenting rights given to consumers in law as

a distinctive feature of the trader’s offer.

A stationer sells pens. He advertises on the following basis:

‘Pens for sale. If they don’t work I’ll give you your money back

or replace them. You won’t find this offer elsewhere’. If the

pen is faulty at the time of purchase the consumer would be

entitled to a refund, repair or replacement under contract law.

The trader’s emphasis on the unique nature of his offer to

refund or replace would breach the CPRs.

(11) Using editorial content in the media to promote a

product where a trader has paid for the promotion

without making that clear in the content or by images or

sounds clearly identifiable by the consumer (advertorial).

A magazine is paid by a holiday company for an advertising

feature on their luxury Red Sea diving school. The magazine

does not make it clear that this is a paid-for feature – for

example by clearly labelling it ‘Advertising Feature’ or

‘Advertorial’. This would breach the CPRs.

(12) Making a materially inaccurate claim concerning the

nature and extent of the risk to the personal security

of the consumer or his family if the consumer does

not purchase the product.

A trader selling video door entry systems tells potential

customers ‘There have been a lot of doorstep muggings in

your street recently. There is clearly a gang at work in this

area, and you will probably be mugged on your doorstep too,

before very long, unless you purchase one of my door entry

systems now’. If the risk of doorstep mugging is materially

exaggerated the statement would breach the CPRs.

(13) Promoting a product similar to a product made by a

particular manufacturer in such a manner as deliberately

to mislead the consumer into believing that the product

is made by that same manufacturer when it is not.

A trader designs the packaging of shampoo A so that it

very closely resembles that of shampoo B, an established

brand of a competitor. If the similarity was introduced to

deliberately mislead consumers into believing that shampoo

A is made by the competitor (who makes shampoo B) – this

would breach the CPRs.

BANNED PRACTICES (SCHEDULE 1) | PART 2 | 23

(14) Establishing, operating or promoting a pyramid

promotional scheme where a consumer gives

consideration for the opportunity to receive

compensation that is derived primarily from the

introduction of other consumers into the scheme

rather than from the sale or consumption of products.

A trader operates a holiday club which offers consumers,

on payment of a membership fee, the opportunity of earning

large amounts of money by recruiting other consumers

to membership of the club. The other benefits of club

membership are negligible compared to the potential

rewards of earning commission for introducing new

members. This practice would breach the CPRs.

(15) Claiming that the trader is about to cease trading

or move premises when he is not.

A trader runs a clothes shop. He puts up a sign in the shop

window stating: ‘Closing down sale’. Unless the shop was

genuinely closing down this would breach the CPRs.

(16) Claiming that products are able to facilitate winning in

games of chance.

A trader advertises a computer program with the claim:

‘This will help you win money on scratchcard lotteries’. This

would breach the CPRs.

(17) Falsely claiming that a product is able to cure illnesses,

dysfunction or malformations.

A trader sells orthopaedic beds to the elderly with the

advertisement ‘Cure your backache once and for all with my

special beds’. If untrue, his definitive statement about the

curative effects of his product would breach the CPRs. The

court may order the trader to substantiate such a claim in

proceedings.

(18) Passing on materially inaccurate information on market

conditions or on the possibility of finding the product

with the intention of inducing the consumer to acquire

the product at conditions less favourable than normal

market conditions.

An estate agent tells a consumer that he has recently

sold several houses in the same area, just like the one the

consumer is viewing, at a certain price. If this is not true and

he is making the claim in order to persuade the consumer

to buy at an inflated price, the estate agent would breach the

CPRs.

24 | PART 2 | BANNED PRACTICES (SCHEDULE 1)

(19) Claiming in a commercial practice to offer a competition

or prize promotion without awarding the prizes described

or a reasonable equivalent.

A trader operates a scratch-card prize promotion with a top

prize of £10,000. In fact, he does not print any cards that win

this top prize (or does print the cards but does not make them

available). As this would mean that no prizes of £10,000 could

be awarded, this would breach the CPRs.

(20) Describing a product as ‘gratis’, ‘free’, ‘without charge’

or similar if the consumer has to pay anything other than

the unavoidable cost of responding to the commercial

practice and collecting or paying for delivery of the item.

A trader advertises a ‘free’ gift. He then tells consumers that

in order to receive their ‘free’ gift they need to pay an extra

fee. This would breach the CPRs.

(21) Including in marketing material an invoice or similar

document seeking payment which gives the consumer

the impression that he has already ordered the marketed

product when he has not.

A trader sends letters to consumers with his marketing

material which are or closely resemble invoices for a product

that has not been ordered. This would breach the CPRs.

(22) Falsely claiming or creating the impression that the

trader is not acting for purposes relating to his trade,

business, craft or profession, or falsely representing

oneself as a consumer.

A second-hand car dealership puts a used car on a nearby

road and displays a handwritten advertisement reading

‘One careful owner. Good family run-around. £2000 or

nearest offer. Call Jack on 01234 56789’. The sign gives the

impression that the seller is not selling as a trader, and

hence this would breach the CPRs.

(23) Creating the false impression that after-sales service in

relation to a product is available in a European Economic

Area State

12

other than the one in which the product is sold.

(24) Creating the impression that the consumer cannot leave

the premises until a contract is formed.

A holiday company advertise sales presentations at hotels.

During the presentations, intimidating doormen are posted

at all the exits, creating the impression that the consumers

cannot leave before buying. This would breach the CPRs.

12 European Economic Area (EEA) States are all European

Member States and, in addition, Norway, Iceland and

Liechtenstein. See http://ec.europa.eu/external_relations/

eea/ for further information on the EEA.

BANNED PRACTICES (SCHEDULE 1) | PART 2 | 25

(25) Conducting personal visits to the consumer’s home

ignoring the consumer’s request to leave or not to return

except in circumstances and to the extent justified

13

to

enforce a contractual obligation.

A door to door salesman visits a consumer to sell her some

cleaning products. She tells him she is not interested

and asks him to leave. He is determined to try and get her

to change her mind and continues his sales pitch on her

doorstep. This would breach the CPRs.

(26) Making persistent and unwanted solicitations by

telephone, fax, e-mail or other remote media except

in circumstances and to the extent justified

14

to enforce

a contractual obligation.

A direct seller telephones consumers to sell them products,

but does not record when consumers have explicitly asked

to be removed from their contact lists. The trader calls back

consumers several times, who have asked him not to. This

would breach the CPRs.

Note that a consumer who has signed up to the Telephone

Preference Service is likely to be regarded as a consumer

who does not want unsolicited telephone calls.

(27) Requiring a consumer who wishes to claim on an

insurance policy to produce documents which could

not reasonably be considered relevant as to whether

the claim was valid, or failing systematically to respond

to pertinent correspondence, in order to dissuade a

consumer from exercising his contractual rights.

(28) Including in an advertisement a direct exhortation to children

to buy advertised products or persuade their parents or

other adults to buy advertised products for them.

Advertising a comic book for children stating ‘read about the

adventures of Fluffy the Bunny in this new comic book each

week – ask your mum to buy it from your local newsagents’.

This (telling children to ask their mothers) would breach the

CPRs.

(29) Demanding immediate or deferred payment for or the

return or safekeeping of products supplied by the trader,

but not solicited by the consumer, except where the

product is a substitute supplied in accordance with

regulation 19(7) of the consumer Protection (Distance

Selling) Regulations 2000 (inertia selling).

15

A trader writes to consumers informing them of a new

grease eradicating dishcloth which he is selling for £2.99.

In the letter the trader encloses one of the cloths for the

consumer to inspect and says that if the consumer does

not return the cloth within 7 days then action will be taken to

collect the £2.99. This would breach the CPRs.

13 Allowed actions would include legitimate debt

collection or asset recovery in line with the rules

governing such actions.

14 Allowed action would include, for example,

legitimate debt collection. Collectors must,

however, comply with CPRs, as well as the

Consumer Credit Act 1974 – on which the Office of

Fair Trading has issued guidance: Debt collection

guidance OFT 664.

15 Statutory Instrument 2000/2334

26 | PART 2 | BANNED PRACTICES (SCHEDULE 1)

(30) Explicitly informing a consumer that if he does not buy the

product or service, the trader’s job or livelihood will be in

jeopardy.

(31) Creating the false impression that the consumer has already

won, will win, or will on doing a particular act win,

a prize or other equivalent benefit, when in fact either:

(a) there is no prize or other equivalent benefit, or

(b) taking any action in relation to claiming the prize or other

equivalent benefit is subject to the consumer paying money

or incurring a cost.

A trader sends letters to consumers which, at the top of the letter

in large characters, state: ‘You have won our top prize of £3,000.’

This is false – only the small print on the back of the letter mentions

that the consumer must buy a product before being entered into a

draw for the money. This would breach the CPRs.

BANNED PRACTICES (SCHEDULE 1) | PART 2 | 27

CHAPTER 7

MISLEADING

PRACTICES

(REGULATIONS 5 AND 6)

7.1 The CPRs prohibit misleading actions and misleading

omissions (as detailed in regulations 5 and 6),

16

which cause

or are likely to cause the average consumer to take a

different decision.

7.2 A practice can mislead by action or omission or both. These

prohibitions aim to ensure that consumers get from traders,

in a clear and timely fashion, the information they need to

make informed decisions relating to products. In addition,

in some commercial practices (referred to as ‘invitations

to purchase’) certain specific information must be given to

consumers, unless apparent from the context.

MISLEADING ACTIONS (regulation 5)

Giving false information to, or deceiving, customers

7.3 A misleading action occurs when a practice misleads through

the information it contains, or its deceptive presentation, and

causes or is likely to cause the average consumer to take a

different decision.

7.4 For instance, if a trader falsely tells a consumer that his

boiler cannot be repaired and he will need a new one, he will

have committed a misleading action.

7.5 The CPRs specify three types of misleading actions:

• misleadinginformationgenerally(seepara7.6below)

• creatingconfusionwithcompetitors’products

(see para 7.10 below)

• failingtohonourrmandveriablecommitmentsmadein

a code of conduct (see para 7.11 below).

Each of these three types of misleading actions

is dealt with in greater detail below.

16 The prohibitions are contained in regulations 3(1), 3(4)(a)

and 3(4)(b) of the CPRs.

MISLEADING PRACTICES (REGULATIONS 5 AND 6) | PART 2 | 29

MISLEADING INFORMATION GENERALLY

7.6 These are actions that mislead by:

• containingfalseinformationORdeceivingorbeinglikely

to deceive the average consumer (even if the information

they contain is factually correct),

17

and

• thefalseinformation,ordeception,relatestooneormore

pieces of information in a (wide-ranging) list (see below),

and

• theaverage consumer takes, or is likely to take,

a different decision as a result.

7.7 The list of information mentioned above includes the main

factors consumers are likely to take into account in making

decisions relating to products, for example the main

characteristics of the product and the price or the way it is

calculated. The full list follows:

(a) the existence or nature of the product,

(b) the main characteristics of the product

(c) the extent of the trader’s commitments

(d) the motives for the commercial practice

(e) the nature of the sales process

(f) any statement or symbol relating to direct or indirect

sponsorship or approval of the trader or the product

(g) the price or the manner in which the price is calculated

(h) the existence of a specific price advantage

(i) the need for a service, part, replacement or repair

(j) the nature, attributes and rights of the trader or his agent

(k) the consumer’s rights or the risks he may face.

The ‘main characteristics of the product’ include:

(a) availability of the product

(b) benefits of the product

(c) risks of the product

(d) execution of the product

(e) composition of the product

(f) accessories of the product

(g) after-sale customer assistance concerning the product

(h) the handling of complaints about the product

(i) the method and date of manufacture of the product

(j) the method and date of provision of the product

17 The deception can occur in any way, including in the

overall presentation of the commercial practice.

30 | PART 2 | MISLEADING PRACTICES (REGULATIONS 5 AND 6)

(k) delivery of the product

(l) fitness for purpose of the product

(m) usage of the product

(n) quantity of the product

(o) specification of the product

(p) geographical or commercial origin of the product

(q) results to be expected from use of the product

(r) results and material features of tests or checks carried out

on the product.

The ‘nature, attributes and rights of the trader or his agent’

include:

(a) identity

(b) assets

(c) qualifications

(d) status

(e) approval

(f) affiliations or connections

(g) ownership of industrial, commercial or intellectual

property rights

(h) awards and distinctions.

7.8 The ‘consumer’s rights’ include rights the consumer may

have under Part 5A of the Sale of Goods Act 1979 or Part 1B

of the Supply of Goods and Services Act 1982.

Examples:

A trader tries to sell a consumer a satellite television

package. The consumer is falsely told that the package

includes certain key channels, which are in fact only available

at an additional subscription cost. The trader has provided

false information about the ‘main characteristics of the

product’ (in this case, the contents of the package). As this

practice is likely to cause the average consumer to take a

different decision about the package – for example to buy it

where otherwise he would not - it will breach the CPRs.

A trader advertises televisions for sale saying the price has

been substantially discounted. In fact, they have only been

on sale at the non-discounted price in very small numbers for

a very short period of time in one of the trader’s numerous

shops. Whilst the trader’s advertisement may be factually

correct, it is likely nonetheless to be deceptive. The average

consumer would have been deceived about the existence of

a specific price advantage in a way that is likely to cause him

to take a different decision about the television – in this case

to buy it.

MISLEADING PRACTICES (REGULATIONS 5 AND 6) | PART 2 | 31

A trader advertises a house as having 3 bedrooms, when

in fact it has 2; or it does have 3 rooms called bedrooms but

the third is physically too small to fit a bed in. This will be a

misleading action if it causes the average consumer to take

a different decision in relation to the house as a result. The

misleading information here about the number of bedrooms

would probably relate to 5(4)(a), the ‘main characteristics

of the product’, by virtue of 5(5)(o) the ‘specification’ of the

product, i.e. the house.

7.9 The Code of Practice for Traders on Price Indications

no longer has effect. BERR have issued non-statutory

best practice guidance on pricing,

18

which reflects the

requirements of the CPRs.

CREATING CONFUSION WITH COMPETITORS’

PRODUCTS

7.10 Commercial practices are also prohibited as misleading

actions if they:

• marketaproduct in a way which creates confusion

with any products, trade marks, trade names or other

distinguishing marks of a competitor,

and

• theaverage consumer takes, or is likely to take,

a different decision as a result

Example:

A trader names or brands his new sunglasses so as to

very closely resemble the name or brand of a competitor’s

sunglasses. If the similarity is such as to confuse the average

consumer making him more likely to opt for the new

sunglasses when he otherwise would not, this would breach

the CPRs.

FAILING TO HONOUR COMMITMENTS MADE IN A CODE

OF CONDUCT

7.11 The third category of commercial practices prohibited as

misleading actions is that where:

• thetrader has undertaken to be bound by a code of

conduct (or code of practice), and indicates that he

is bound by it in the commercial practice,

and

• thetrader fails to comply with a firm and verifiable

commitment in that code,

and

• theaverage consumer takes, or is likely to take,

a different decision as a result

18 BERR Pricing Practices Guide: Guidance for traders on

good practice in giving information about prices

- URN 08/918

32 | PART 2 | MISLEADING PRACTICES (REGULATIONS 5 AND 6)

Example

A trader has agreed to be bound by a code of practice that

promotes the sustainable use of wood and displays the

code’s logo in an advertising campaign (i.e. in a commercial

practice). The code of practice contains a commitment that

its members will not use hardwood from unsustainable

sources. However, it is found that the product advertised by

the trader contains hardwood from endangered rainforests.

This practice is a breach of a firm and verifiable commitment.

As the average consumer would expect code members to

sell products which comply with their code, and is likely to

decide to buy them on this basis, this practice would breach

the CPRs.

MISLEADING OMISSIONS (regulation 6)

Giving insufficient information about the product

7.12 Practices may also mislead by failing to give consumers the

information they need to make an informed choice (in relation

to a product). This occurs when practices:

• omitorhidematerialinformation,orprovideitinan

unclear, unintelligible, ambiguous or untimely manner,

and

• theaverage consumer takes, or is likely to take,

a different decision as a result.

7.13 A misleading omission can also occur where a trader fails to

identify the commercial intent of a practice, if it is not already

apparent from the context. The presence of a price, or of a

statement making it clear that the practice is commercial

(for example: ‘this is an advertisement’), are examples of

how commercial intent could be made clear.

7.14 When deciding whether a practice misleads by omission,

the courts will take account of the context.

19

MATERIAL INFORMATION

7.15 Material information is information that the average

consumer needs to have, in the context, in order to make

informed decisions. It includes any information required

by European (EC) derived law, such as the Package Travel,

Package Holidays and Package Tours Regulations

20

and the

Consumer Protection (Distance Selling) Regulations.

21

19 See the section on ‘context’ later in this chapter for more

information on how this might work in practice.

20 Statutory Instrument 1992/3288.

21 Statutory Instrument 2000/2334, as amended.

MISLEADING PRACTICES (REGULATIONS 5 AND 6) | PART 2 | 33

7.16 What information is required will depend on the

circumstances, for example what the product concerned is,

and where and how it is offered for sale. This may range from

a very small amount of information for simple products,

to more information for complex products.

7.17 The price of a product in most circumstances is material

information. Therefore, failing to provide this in a timely

fashion before a transactional decision is made is likely

to amount to a misleading omission. For example, in

restaurants, the prices of the food and drink available will

usually need to be given to consumers before they order.

7.18 Material information includes any information which causes

or is likely to cause the average consumer to take a different

decision about the product.

Examples:

A trader omits to mention that a contract has to run for a

minimum period, or that the consumer has to go on making

purchases in future, this would probably be a material

omission.

A trader advertises mobile phones for sale. If the phones

were second hand and/or had been reconditioned, this would

be material information, which would need to be made clear

to consumers.

A trader operates a car park. If he fails to clearly display the

price(s) of parking at a point before the consumer enters the

car park and incurs a charge, this would be failing to provide

material information.

A trader sells audio-visual equipment. He omits to inform

the consumer that a particular product includes only an

analogue tuner, and of the implications in the context of the

switch from analogue to digital-only television. This is likely to

be material information that the consumer needs to make an

informed decision.

CONTEXT

7.19 Consideration of the context includes any limitations of the

communication medium used (of space or time) that make

it impractical to give the necessary information. In such

circumstances, if other means have been used by the trader

to convey this information, these will be relevant.

34 | PART 2 | MISLEADING PRACTICES (REGULATIONS 5 AND 6)

Example:

A trader sells cereal bars. On their wrappers the trader

advertises a ‘t-shirt for £1’ offer. In fact, various conditions

apply (such as restrictions on the availability of the t-shirts).

The outside of the wrapper is too small to include all of this

information. The trader is less likely to commit a misleading

omission if he makes clear on the wrapper that terms and

conditions apply and provides details of where they can be

found.

INVITATIONS TO PURCHASE (regulation 6[4])

7.20 The CPRs make special provision for certain kinds of

commercial practice known as ‘invitations to purchase’.

22

They specify information that is automatically regarded as

material information unless it is apparent from the context.

Its omission may therefore lead to a misleading omission as

described in paragraph 7.12 above.

7.21 So, where traders make invitations to purchase they will

need to ensure that their commercial practices include the

information required by the CPRs, or that such information

is apparent from the context. This is not to say that such

information only needs to be provided where there can be

said to be an invitation to purchase. It may need to be

provided anyway if consumers need it to make an informed

decision. Failure to provide information that is needed for that

purpose can constitute a misleading omission, and thus make

a commercial practice unfair, whether or not an invitation

to purchase is involved. For more details on misleading

omissions generally see above paragraphs 7.12 – 7.19.

IDENTIFYING AN INVITATION TO PURCHASE

7.22 An invitation to purchase has the following elements:

• itisacommercialcommunication,and

• itindicatescharacteristicsoftheproduct concerned and

the price, in a way appropriate to the communication

medium used, and

• ittherebyenablestheconsumer to make a purchase.

7.23 The idea behind this concept is that the consumer is

given the key information he needs to make an informed

purchasing decision.

7.24 ‘Thereby enables’ primarily refers to enabling of a purchase

through the provision of information. The amount of

information that enables the consumer to make a purchase

will vary depending on the circumstances. Complex

products may require the provision of more information than

simple ones before a purchase is enabled.

22 The CPRs concept of ‘invitation to purchase’ is not

the same as the UK concept of ‘invitation to treat’.

MISLEADING PRACTICES (REGULATIONS 5 AND 6) | PART 2 | 35

7.25 The following will normally be invitations to purchase

where the product’s price and characteristics are given:

• anadvertisementinanewspaperwherepartofthe

advertisement is an order form that can be sent to the

trader

• aninteractiveTVadvertisementthroughwhichorderscan

be directly placed

• apageorpagesonawebsitewhereconsumers can

place an order

• amenuinarestaurantfromwhichconsumers can place

an order

• atextmessagepromotiontowhichconsumers can

directly respond in order to purchase the promoted

product

• aradioadvertisementforamobilephoneringtone,which

provides a word and number to text in order that the

consumer can purchase and pay for (via their phone bill)

the jingle to be uploaded to their device.

• apriceonaproduct in a shop.

COMMERCIAL PRACTICES WHICH ARE NOT INVITATIONS

TO PURCHASE

7.26 It is important to note that if a communication is not an

invitation to purchase it may still mislead by omission if

it meets the conditions described in paragraph 7.12 above.

7.27 Where a commercial communication does not indicate the

characteristics of a specific product, through text, image or

otherwise, it will not be an invitation to purchase.

7.28 A commercial communication which does not include a price

is not an invitation to purchase.

7.29 Where a commercial communication does not ‘enable

the consumer to make a purchase’, then it will not be an

invitation to purchase.

7.30 In many cases, advertisements which promote a trader’s

‘brand’ rather than any particular product(s) will not be

invitations to purchase.

REQUIRED (MATERIAL) INFORMATION

7.31 The CPRs deem certain information to be ‘material’ where

traders make invitations to purchase. Subject to the same

considerations about the context and the limitations of the

communication medium as apply to misleading omissions

generally (see paragraph 7.19), that information must be

provided in a clear, unambiguous, intelligible and timely

manner, unless apparent from the context.

36 | PART 2 | MISLEADING PRACTICES (REGULATIONS 5 AND 6)

7.32 Where the required information is apparent from the context

then traders do not need to provide it separately. An example

of information which is likely to be apparent from the context

will be the address of a shop which the consumer is already

in.

7.33 Information that is deemed to be material in invitations to

purchase is set out in regulation 6(4), which is summarised

below:

• themaincharacteristicsoftheproduct – for example,

what it is and what it does – to the extent appropriate to

the medium used by the invitation to purchase and the

product

• theidentityofthetrader, such as his trading name, and

the identity of any other trader on whose behalf the

trader is acting

• thegeographicaladdressofthetrader or traders

• thepriceoftheproduct (including taxes) or, where the

price cannot be reasonably calculated in advance, the way

it will be calculated

• anyfreight,deliveryorpostalcharges,or,wherethese

cannot reasonably be calculated in advance, the fact that

such charges may be payable

• anyarrangementsforpayment,delivery,performance

(that is the way in which any work is to be carried out, or a

service provided) and complaint handling that differ from

the requirements of professional diligence

• theexistenceofanycancellationrights.

This is in addition to any other information the average

consumer needs, in the context, to make informed decisions

and any other information required under other Community

law provisions.

EXAMPLES OF INVITATIONS TO PURCHASE

7.34 The following are examples of how the information listed

in Regulation 6(4) might be provided in differing types of

invitation to purchase:

Pencil (a simple product)

23

A shop has a number of pencils for sale and displays the

price. This is an invitation to purchase because the

information given in the context of a shop enables the

consumer to make a purchase (by taking the pencil to

the till and paying for it). The pencils themselves ‘indicate’

their characteristics (that they are pencils), and the pencils

together with the price ticket / label are the commercial

communication.

In this instance, the material information required is provided

23 See paragraph 7.24 above.

MISLEADING PRACTICES (REGULATIONS 5 AND 6) | PART 2 | 37

on the pricing label or is already apparent from the context.

The main characteristics of the product – such as the colour

or thickness of the lead – are apparent from looking at it. The

trader trades under his own name and is based in the shop

(the address), the price is given, there are no arrangements

for payment, delivery, performance or complaint handling

that differ from those that consumers would reasonably

expect. There are no omissions of cancellation rights or

information requirements under other Community law

provisions.

Price list in a bar

A licensed premises offers various drinks for sale to

consumers. The price list (which is the commercial

communication) placed near the bar provides consumers

with the information they need to enable them to purchase

drinks, in that it tells consumers what drinks are available

and their price.

In this instance, the main characteristics are the name (and

possibly the name of the brand) of the drinks available. The

trader’s identity and the name of the establishment are given

on the price list, and the address is apparent from the context

(because consumers are already at the address). There are

no delivery or other arrangements which are contrary to the

requirements of professional diligence that need noting.

Mail order advertisement

An advertisement in a magazine features T-shirts for sale.

The prices and sizes of the T-shirts available are given in the

advertisement, and the bottom half of the advertisement is

an order form which can be filled in, with payment enclosed,

and sent direct to the retailers. This would be an invitation to

purchase.

Here, the main characteristics of the product are included

in the advertisement – such as the size, material and colour).

The trader’s identity is stated in the advertisement, as

is his geographical address. So, too, are payment and

delivery arrangements. The advertisement also mentions

the consumer’s entitlement to cancel any order and the

period for which the advertised price would be valid, given

this is a contract concluded by mail order and the Consumer

Protection (Distance Selling) Regulations 2000 apply (see

page 33, paragraph 7.15).

38 | PART 2 | MISLEADING PRACTICES (REGULATIONS 5 AND 6)

Car

A car showroom has a used car on display for sale. The price

is shown clearly on the car. This (the car and the price) would

be an invitation to purchase, because the information given

in the context of the showroom enables the consumer to

make a purchase, by asking to purchase the car and paying

for it within the showroom.

Here, the main characteristics of the product are included

in the sales card or are already apparent from the context,

such as the make, model, accurate mileage, engine

capacity, colour and other physical characteristics of the car.

The trader’s identity is apparent from information in the

showroom, the price is given on a sign on the car and there

are no arrangements for payment, delivery, performance

or complaint handling, that differ from the requirements of

professional diligence. The car can be purchased and taken

from the showroom, and returned there if complaints arise.

There are no omissions of cancellation rights or information

requirements under other Community law provisions.

Computer (a complex product)

A trader sells computers from his website. The site’s

homepage pictures the range of computers sold by the

trader. Each picture provides a link to a detailed page which

gives the specifications (characteristics) of the relevant

computer and that page also gives its full price and has a

‘buy now’ button (by clicking on which the computer may be

purchased). This detailed page is an invitation to purchase.

On separate pages on the website that can be reached via a

clearly-indicated link on the detailed page, are:

• themaincharacteristicsofthecomputer(forexamplethe

processor, memory, graphics, software and accessories)

including its function (for example ‘home multimedia’ or

‘games package’)

• thefullprice(inclusiveoftaxesandanyfreightordelivery

charge) if this was not given on the previous page

• thetrader’s name and geographic address

• thedeliveryandpaymentarrangementsaswellasthe

complaints/after-sales procedures, and

• sincethecomputerisbeingsoldovertheinternet,

information required by the Electronic Commerce

(EC Directive) Regulations 2002

24

and The Consumer

Protection (Distance Selling) Regulations 2000

25

, including

cancellation rights

24 Statutory Instrument 2002/2013.

25 Statutory Instrument 2000/2334, as amended.

MISLEADING PRACTICES (REGULATIONS 5 AND 6) | PART 2 | 39

CHAPTER 8

AGGRESSIVE

COMMERCIAL

PRACTICES

(REGULATION 7)

8.1 The CPRs also prohibit aggressive commercial practices

(as detailed in regulation 7)

26

. These are practices that, in the

context of the particular circumstances, intimidate or exploit

consumers, restricting their ability to make free or informed

choices. In order for an aggressive practice to be unfair it

must cause or be likely to cause the average consumer to

take a different decision.

PROHIBITION ON AGGRESSIVE PRACTICES

8.2 The CPRs prohibit commercial practices which

• byharassment,coercion(includingphysicalforce)or

undue influence,

• signicantlyimpair,orarelikelytosignicantlyimpair,

the average consumer’s freedom of choice or conduct

concerning the product,

and

• Theaverage consumer takes, or is likely to take, a

different decision as a result

These elements are described below.

HARASSMENT, COERCION AND UNDUE INFLUENCE

8.3 Harassment and coercion are not expressly defined in the

CPRs but include both physical and non-physical, (including

psychological) pressure.

8.4 Undue influence is defined in regulation 7(3)(b) of the CPRs as:

‘exploiting a position of power in relation to the consumer

so as to apply pressure, even without using or threatening

to use physical force, in a way which significantly limits the

consumer’s ability to make an informed decision’.

An example of this might be a mechanic who has a

consumer’s car at his garage and has done more work than

agreed, and who refuses to return the car to the consumer

until he is paid in full for the work. The mechanic did not check

with the consumer before he went ahead with the extra

work. As he has the car, he has power over the consumer’s

decision to pay for the unauthorised work. He has exploited

his position of power, by demanding payment for doing more

than was agreed and refusing to return the vehicle until the

consumer has paid for all the work.

Another example might be a trader selling credit

27

who

pressurises an existing borrower to take out an additional

loan. This could amount to harassment, coercion or undue

influence.

See the glossary for more information.

26 The prohibition is contained in regulations 3(1) and 3(4)(c) of

the CPRs.

27 Additional examples of unfair (including aggressive) debt

collection practices can be found in the OFT’s Debt collection

guidance – OFT 664.

AGGRESSIVE COMMERCIAL PRACTICES (REGULATION 7) | PART 2 | 41

SIGNIFICANT IMPAIRMENT OR LIMITATION

8.5 The CPRs refer to practices that ‘significantly impair’ and

those that ‘significantly limit’ decisions (the latter is in the

definition of undue influence). These are likely to have a very

similar meaning and both will depend on the context.

8.6 Significant impairment might occur when, for example, a

trader stays in a consumer’s home for so long that they feel

compelled to sign a contract for a product.

28

FREEDOM OF CHOICE OR CONDUCT

8.7 The concept of freedom of choice is not limited solely to

decisions about whether to purchase a product or not. It

covers a wide range of choices that are likely to impact on

transactional decisions.

8.8 For example, coercion might cause consumers to purchase

the product at a much higher price or on disadvantageous

terms. Breaches of the CPRs could occur even if:

• consumers might still have bought the product from the

same trader, but on different terms

• consumers might still have bought the product, but from

a different trader.

FACTORS INDICATING AN AGGRESSIVE PRACTICE

8.9 The CPRs list factors which shall be taken into account when

determining whether a commercial practice is aggressive.

It is not necessary for all of these factors to be present for

a practice to be aggressive and therefore unfair (provided

that the commercial practice uses harassment, coercion or

undue influence).

8.10 The factors are:

(a) Timing, location, nature or persistence,

(b) The use of threatening or abusive language or behaviour,

(c) The exploitation by the trader of any specific misfortune, or

circumstance, of such gravity as to impair the consumer’s

judgement, of which the trader is aware, to influence the

consumer’s decision with regard to the product,

(d) Any onerous or disproportionate non-contractual barriers

imposed by the trader where a consumer wishes to

exercise rights under the contract, including rights to

terminate a contract or switch to another product or

trader,

(e) Any threat to take any action that cannot legally be taken.

28 This practice could also breach paragraph 25 of Schedule

1 to the Regulations, the list of practices that will always

be unfair – ‘Conducting personal visits to the consumer’s

home ignoring the consumer’s request to leave or not to

return except in circumstances and to the extent justified,

under national law, to enforce a contractual obligation’.

42 | PART 2 | AGGRESSIVE COMMERCIAL PRACTICES (REGULATION 7)

POSSIBLE AGGRESSIVE PRACTICES

8.11 The examples below assume that the average consumer

would or would be likely to take a different decision as a

result of the practice(s) described.

Staff working in a funeral parlour put pressure on a recently

bereaved relative, who is deciding on a coffin, to buy a more

expensive coffin to avoid bringing shame on the family. This

could amount to coercion or undue influence. (Exploitation

of specific misfortune, and timing)

A trader takes consumers to a holiday club presentation at a

distant location, with no apparent return transport unless the

consumers sign a contract. This could amount to coercion

and/or undue influence. (Nature / location)

A doorstep trader pressures a consumer to pay in cash

for home repairs immediately. He insists on giving the

consumer a lift to the bank to withdraw the money. This

could amount to coercion or undue influence. (Nature,

persistence, location)

A debt collector

29

pressurises existing borrowers/debtors

to repay a debt, for example, by contacting debtors at

unreasonable times (such as late at night) or at unreasonable

locations (such as at work when they have been requested

not to). This could amount to harassment, coercion or

undue influence. (Timing, persistence, nature and location,

exploitation of circumstances – this might amount to

exploitation of the imbalance of power between the creditor

and debtor, as well as of the specific circumstances of the

debtor)

A debt collector threatens consumers with recovery of

money by bailiffs for unenforceable debts.

30

This could

amount to harassment, coercion or undue influence.

(Exploitation of circumstances and threat to take action

which cannot legally be taken)

29 Additional examples of unfair (including aggressive)

debt collection practices can be found in the OFT’s Debt

collection guidance – OFT 664.

30 This could also breach the prohibitions on misleading

actions as well as the prohibition on aggressive practices.

AGGRESSIVE COMMERCIAL PRACTICES (REGULATION 7) | PART 2 | 43

CHAPTER 9

PROMOTING UNFAIR

PRACTICES IN

CODES OF CONDUCT

9.1 The CPRs also prohibit the promotion of unfair commercial

practices by a code owner in a code of conduct

(see regulation 4).

9.2 Note that there is no criminal offence attached to this

prohibition. Any enforcement action, if needed, will be taken

through the civil route via Part 8 of the Enterprise Act 2002.

Action will be against the relevant code owner (including, in

some situations, specific individuals).

9.3 In order for this prohibition to be infringed, the code owner

must in a code of conduct promote a practice that is unfair

as determined by one (or more) of the other prohibitions

contained in the CPRs.

9.4 Enforcers are likely to rely on this prohibition where the

promotion takes the form of a statement in the code of

conduct and altering the code of conduct is therefore likely

to be a more effective method of dealing with the unfair

practice than taking action against any individual trader or

traders who are engaging in the practice.

POSSIBLE UNFAIR PRACTICES PROMOTED BY A CODE

OF CONDUCT

9.5 A code owner is responsible for a code of practice relating

to the online sale of personal computers. The code states that

there is no need for member businesses to give a geographic

address when advertising in any circumstances. As this a

material omission in certain circumstances, promotion of the

resulting commercial practice via this statement would be

prohibited.

PROMOTING UNFAIR PRACTICES IN CODES OF CONDUCT | PART 2 | 45

CHAPTER 10

GENERAL PROHIBITION

OF UNFAIR COMMERCIAL

PRACTICES

(REGULATION 3)

FAILING TO ACT IN ACCORDANCE WITH REASONABLE

EXPECTATIONS OF ACCEPTABLE TRADING PRACTICE

10.1 Regulations 3(1) and 3(3) of the CPRs set out the general

prohibition on unfair business to consumer commercial

practices, also known as the general duty not to trade

unfairly. This prohibition allows enforcers to take action

against unfair commercial practices, including those that

do not fall into the more specific prohibitions of misleading

and aggressive practices, or into the very specific banned

practices. This means it acts as a safety net. It is designed

to ‘future-proof’ the protections in the CPRs, by setting

standards against which all existing and new practices can

be judged.

GENERAL PROHIBITION

10.2 The general prohibition is made up of two tests. It prohibits

practices that:

• contravenethe requirements of professional diligence

and

• materiallydistorttheeconomicbehaviouroftheaverage

consumer with regard to the product

(or are likely to).

10.3 The first test is concerned with the conduct itself – that is the

standards of the trader’s practice. The second is concerned

with the actual or likely effect the practice has on the average

consumer’s economic behaviour.

TEST 1: PROFESSIONAL DILIGENCE

10.4 Professional diligence is defined (in Regulation 2) as:

‘the standard of special skill and care which a trader may

reasonably be expected to exercise towards consumers

which is commensurate with either — (a) honest market

practice in the trader’s field of activity, or (b) the general

principle of good faith in the trader’s field of activity’.

10.5 Professional diligence is an objective standard which

will vary according to the context. The word ‘special’ is not

intended to require more than would reasonably be expected

of a trader in their field of activity. However, poor current

practice that is widespread in an industry/sector cannot

amount to an acceptable objective standard. That is because

this is not what a reasonable person would expect from

a trader who is acting in accordance with honest market

practice or good faith.

GENERAL PROHIBITION OF UNFAIR COMMERCIAL PRACTICES (REGULATION 3) | PART 2 | 47

10.6 The CPRs do not define honest market practice or good faith.

They are similar and overlapping principles. They require

traders to approach transactions professionally and fairly as

judged by a reasonable person.

10.7 Guidance and codes of practice, including OFT-approved

codes, may be drawn upon to help establish whether a

trader is behaving in a professionally diligent manner.

However, complying with these codes and Guidance may not

be necessary, or, alternatively, sufficient of itself in order for a

trader to be professionally diligent.

TEST 2: MATERIAL DISTORTION

10.8 Material distortion is defined (in Regulation 2) as:

‘appreciably to impair the average consumer’s ability to

make an informed decision thereby causing him to take

a transactional decision that he would not have taken

otherwise’. It applies either when a practice distorts or

is likely to distort the average consumer’s behaviour.

10.9 ‘Material distortion’ means that a practice impairs the

average consumer’s ability to make an informed decision.

The impairment must be significant enough to change the

decisions the average consumer makes. This means that

practices that do not affect, or are unlikely to affect, the

economic behaviour of average consumers are unlikely

to be unfair under the general prohibition in the CPRs.

10.10 The CPRs define ‘the average consumer’ by reference

to the concepts of the ‘average’ consumer, the ‘average’

member of a targeted group of consumers and the ‘average’

member of a vulnerable group of consumers. Different types

of average consumer may react differently to the same

practice. These concepts, and their relation to each other,

are discussed in the Glossary.

48 | PART 2 | GENERAL PROHIBITION OF UNFAIR COMMERCIAL PRACTICES (REGULATION 3)

PART 3

CHAPTER 11

COMPLIANCE AND

ENFORCEMENT

11.1 Local Authority Trading Standards Services (TSS), the

Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment in Northern

Ireland and the OFT have a duty to enforce the CPRs. This

does not mean that (civil or criminal) enforcement action

must be taken in respect of each and every infringement.

Instead, enforcers should promote compliance by the most

appropriate means, in line with their enforcement policies,

priorities and consistent with available resources.

11.2 Enforcers can use a range of tools to ensure that businesses

are complying with CPRs. The main options, which are

explained below, are:

• education,adviceandguidance

• establishedmeans

• codesofconduct

• civilenforcement

• criminalenforcement.

11.3 When considering action under the CPRs enforcers will have

regard to the principles of proportionality, accountability,

consistency, transparency and targeting and where formal

enforcement action is taken this should seek to:

• changethebehaviouroftheoffender

• eliminateanynancialgainorbenetfromnon-

compliance

• beresponsiveandconsiderwhatisappropriateforthe

particular offender and regulatory issue

• beproportionatetothenatureoftheoffenceandtheharm

caused

• restoretheharmcausedbytheregulatorynon-

compliance, where appropriate, and

• deterfurthernon-compliance.

11.4 Enforcers taking action under the CPRs will act in accordance

with the Regulators’ Compliance Code in carrying out

enforcement action.

31

EDUCATION, ADVICE AND GUIDANCE

11.5 The OFT will generally seek to obtain compliance by

education, giving advice and guidance in the first instance

unless circumstances indicate that enforcement action

is the appropriate first step which may include a criminal

investigation and prosecution.

32

Other enforcers may have

their own enforcement policies in this regard.

COMPLIANCE AND ENFORCEMENT | PART 3 | 51

31 The Regulators’ Compliance Code only applies to the

enforcement of the CPRs in England, Scotland and Wales

and not Northern Ireland where consumer protection

is devolved. See section 24(3) of the Legislative

and Regulatory Reform Act 2006 and article 4 of The

Legislative and Regulatory Reform (Regulatory Functions)