Disaster Preparedness

2021

DG ECHO Guidance Note

European Civil

Protection and

Humanitarian Aid

Operations

DG ECHO Thematic Policy Documents

N°1: Food Assistance: From Food Aid to Food

Assistance

N°2: Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: Meeting the

challenge of rapidly increasing humanitarian

needs in WASH

N°3: Cash and Vouchers: Increasing efficiency and

effectiveness across all sectors

N°4: Nutrition: Addressing Undernutrition in

Emergencies

N°5: Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

N°6: Gender: Different Needs, Adapted Assistance

N°7: Health: General Guidelines

N°8: Humanitarian Protection: Improving protection

outcomes to reduce risks for people in

humanitarian crises

N°9: Humanitarian Shelter and Settlements

Guidelines

DG ECHO Operational Guidelines: The Inclusion of

Persons with Disabilities in EU-funded Humanitarian

Aid Operations

For more information or questions on the Guidance Note, please consult the DG ECHO webpage on Disaster Preparedness or contact the Unit B2 at ECHO-B2-

SECRETARIA[email protected]

1

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

Table of contents

Foreword 2

Executive Summary 3

1. Introduction 5

2. International and EU Policy Frameworks 6

2.1 International frameworks 6

2.1.1 Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 6

2.1.2 Grand Bargain - the Agenda for Humanity 6

2.1.3 Paris Agreement 7

2.1.4 The Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals 8

2.2 EU policy frameworks 8

2.2.1 Preparedness and DG ECHO’s Mandate 8

2.2.2 European Consensus on Humanitarian Aid 9

2.2.3 European Communication on Humanitarian Action 9

2.2.4 European Consensus on Development 10

2.2.5 EU Joint Communication on Resilience 10

2.2.6 The European Green Deal 10

2.2.7 EU Adaptation Strategy 10

3. Preparedness & Risk Informed Approach 11

3.1 Disaster Preparedness 11

3.2 Risk Informed Approach 12

3.2.1 Risk Assessment 14

3.2.2 Anticipatory or Early Action 16

3.2.3 Mainstreaming Preparedness and Risk Proofing Response Interventions 16

3.2.4 Targeted Preparedness Actions 18

4. Key Elements of the DG ECHO Preparedness and Risk-Informed Approach 19

5. Complementary implementing modalities 22

5.1 Humanitarian Development Peace (HDP) Nexus 22

5.2 Partnerships 24

5.3 Union Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM) 26

6. Preparedness Actions 27

6.1 Early Warning System (EWS) 27

6.2 Anticipatory Action 28

6.3 Logistics 29

6.4 Strengthening Capacity 30

6.5 Shock Responsive Social Protection (SRSP) 31

6.6 Cash Preparedness 32

6.7 Institutional, Policy and Legislative Frameworks 33

6.8 Information Management, Data and Technology 34

6.9 Contingency Planning 36

6.10 Advocacy and Awareness 37

6.11 Preparedness - Specific Considerations 37

6.11.1 Climate and environmental resilience interventions 37

6.11.2 Preparedness for Protection 40

6.11.3 Preparedness in urban settings 42

6.11.4 Preparedness for conflict and violent situations 43

6.11.5 Preparedness for Drought 44

6.11.6 Preparedness for Displacement 45

7. Evidence and Learning 47

Annex 48

Annex 1. Mainstreaming Preparedness and Risk Proofing Humanitarian Response 48

Annex 2. Crisis Modifier Note 60

Annex 3. Targeted Preparedness Actions - Global Priorities 2021-2024 69

Annex 4. Resources and Tools 75

Acronyms 79

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

2

Foreword

While this Guidance Note was being drawn up in 2020, the world was suddenly

confronted with an unprecedented crisis: the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the beginning

of the pandemic, countries and organisations across the globe have undertaken

extraordinary efforts to respond to the crisis and strengthen their preparedness to

respond to possible new peaks and future emergencies.

This pandemic has helped us recognise even more that preparedness and effective

response are closely intertwined. This lies at the heart of DG ECHO’s humanitarian

approach, in which preparedness plays a critical role. Ensuring that communities

have the capacity to respond to crises, and to anticipate and address the risks ahead,

whatever they may be, form an integral part of humanitarian aid. This is why DG

ECHO strongly promotes preparedness and risk-based interventions throughout its

humanitarian action.

As our approach has been evolving and adjusting to the new challenges and risks

represented by climate change, environmental degradation and the increasing

overlaps between disasters, conflict and fragile situations, this Guidance Note aims to

support our staff and, more importantly, our partners in their concrete interventions on

the ground. As such, we hope that it will contribute to our common final objective of

helping to save lives.

This is an ambitious objective and we know that as humanitarian actors we cannot

achieve it alone. We need to work in partnership with our development colleagues to

capitalise on mutual strengths and ensure long-term sustainability and resilience. DG

ECHO is firmly committed to this way of working and to translating it into programming

and specific initiatives.

DG ECHO’s work can only be implemented thanks to our humanitarian partners’

commitment, dedication and tireless work. We will stand by their side and work together

to put our approach into practice. We look forward to continuing our collaboration, and

creating a more prepared and resilient world.

Ms Paraskevi Michou

Director General

DG ECHO

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

3

Executive Summary

Over the past two decades, the nature of

humanitarian crises has gradually become more

protracted, unpredictable and complex. Crises

are increasingly exacerbated by factors such

as climate change, environmental degradation,

rapid urbanisation and industrialisation, and

by the overlaps between disasters, conflict

and fragile situations. Faced with these new

challenges, the humanitarian community

- including DG ECHO - needs to adjust its

practices and tools in order to provide a more

effective early response.

As the humanitarian landscape has changed,

international agreements such as the Sendai

Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction

(SFDRR), the Paris Agreement for Climate

Change, as well as the Grand Bargain have

been adopted. They have redefined the

international community’s commitment

towards reducing disaster risk, fighting climate

change and improving the effectiveness

and efficiency of humanitarian action.

Concurrently, the European Commission (EC) has renewed its commitment to

strengthening the resilience of partner countries and to increasing the impact

of its external action through the Joint Communication on Resilience in 2017

1

.

As a result of these developments, and the changing humanitarian landscape,

DG ECHO decided to review and renew its work on disaster preparedness and

promote a risk-informed approach to humanitarian action. This Guidance Note

presents DG ECHO’s new approach and its practical application. It is intended to

be a dynamic document, and will be continuously updated to address changes

in the operational environment.

DG ECHO views preparedness as being critically important for the quality

and timeliness of response operations, as well as being a way of improving

anticipation, thus complementing humanitarian assistance in saving lives,

reducing suffering and pre-empting or decreasing humanitarian needs. DG

ECHO recognises that disaster preparedness applies to all forms of risk, ranging

from natural hazards and epidemics to human-induced threats such as conflict

and violence. Understanding and anticipating such risks is essential in order

to define the needs that they might generate and to design and implement

effective preparedness actions and response operations. All humanitarian

action therefore needs to be informed by risk assessment and analysis, which

should consistently complement a needs-based approach.

1. 2017 Joint Communication - A Strategic Approach to Resilience in the EU’s External Action.

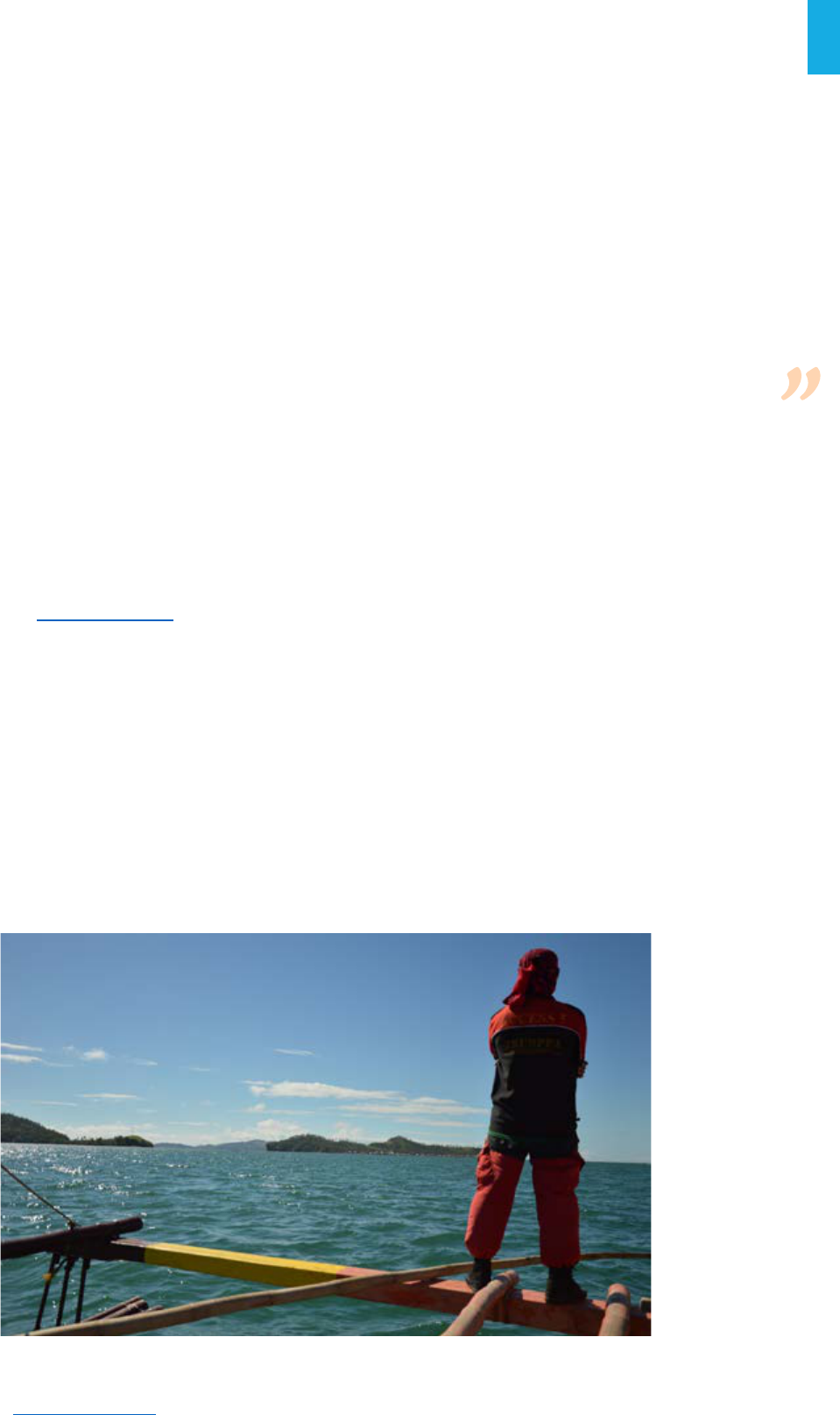

Civil Protection and

Red Cross volunteers

trained under the

Disaster Preparedness

programs funded by DG

ECHO perform a rescue

operation, Haiti.

© EU/ECHO/I.COELLO

In line with the above, DG ECHO promotes the mainstreaming of a preparedness

and risk-informed approach in all its response operations. This approach helps

to systematically strengthen the capacity of first responders to be prepared for

further problems or aershocks while responding to a crisis. It also helps to risk-

proof response interventions by designing them in a way that reduces immediate

and imminent risks. To complement its mainstreaming efforts, DG ECHO also

supports targeted preparedness actions as a specific way of strengthening

preparedness for the early response to a hazard and/or threat (e.g. establishment

of early warning systems, development of contingency plans and Standard

Operating Procedures, emergency prepositioning of stock, etc.).

Strengthening the capacity of local actors

2

, involving affected people in the design

and implementation of activities, and sensitivity to gender, age and diversity,

as well as conflict dynamics, are critical elements of both mainstreaming and

targeted preparedness actions. Similarly, the effects of climate change and

environmental degradation are increasingly integrated into all interventions

in recognition of their role as risk multipliers. Protection and respect for

humanitarian principles are integral to all DG ECHO funded interventions.

As illustrated by this Guidance Note, DG ECHO supports a very broad range of

single sector and multi-sector interventions. Importantly, all these interventions

are flexible in nature as they adjust to the context in which they are being

implemented and, as such, they respond to actual needs, risks and challenges

on the ground.

Humanitarian actors are DG ECHO’s primary partners

in the implementation of both mainstreaming and

targeted preparedness actions. In recognition of the

importance of the humanitarian-development-peace

(HDP) nexus for achieving sustainability and promoting

resilience, DG ECHO will continue to work closely with

all European Union (EU) services aiming to promote

complementarity and mutual reinforcement between

humanitarian and development initiatives – in particular with the Directorate

General for International Partnerships (DG INTPA) and with the Directorate General

for European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement (DG NEAR). A nexus approach

needs to be the backbone of preparedness and resilience. Concurrently, DG ECHO is

increasingly engaging with a variety of actors, including other donors, climate and

environmental organisations, academic, scientific and research institutes, financial

institutions, private sector bodies, and civil protection mechanisms, through the

European Union Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM).

Finally, alongside its commitment to support risk-informed humanitarian action, DG

ECHO is equally committed to ensuring that its humanitarian action is evidence-

based and generates learning, which then feeds into its humanitarian policy and

practice, so that they remain relevant.

2. Local refers to both national and local government actors, civil society, academia, private sector and communities.

“

Protection and respect

for humanitarian principles are

integral to all DG ECHO funded

interventions.

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

4

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

5

1. Introduction

The purpose of this Disaster Preparedness

(DP) Guidance Note is to present and

explain DG ECHO’s disaster preparedness

and risk-informed approach. It aims to

help humanitarian partners, DG ECHO staff,

the staff of relevant Commission services,

and other stakeholders concerned with

DP, to implement the approach through

interventions funded by DG ECHO and other

forms of collaboration with DG ECHO.

This Guidance Note replaces the 2013 DG

ECHO Thematic Policy Note on Disaster Risk

Reduction (DRR)

3

and sets out DG ECHO’s

policy and operational recommendations for

the years to come. However, it is intended to

be a dynamic document that will continuously

be updated to reflect changes and emerging

challenges in humanitarian contexts.

The Guidance Note is structured into 7 Chapters and 4 Annexes. Following a

brief introductory chapter, Chapter 2 presents the international and EU policy

frameworks in which DG ECHO’s preparedness work and risk informed approach

are grounded.

Chapter 3 and 4 explore the different components of the DP and risk-informed

approach, and introduce the two main implementation modalities – mainstreaming

and targeted preparedness. Chapter 5 then introduces the nexus approach to

preparedness and complementary implementation modalities.

Chapter 6 provides a broad overview of those actions that DG ECHO considers

as preparedness and includes operational recommendations. It also gives a

series of concrete examples of preparedness actions that can be implemented

by partners.

Chapter 7 emphasises the need to gather evidence and to learn from partners’

preparedness interventions and risk-informed approaches.

Finally, the Annexes 1 to 3 contain guidance on specific topics - namely,

mainstreaming preparedness and risk reduction into response operations, crisis

modifier and global priorities 2021-2024 for the DP Budget Line. Annex 4

contains a list of resources and tools to explore further the matters addressed

in this document.

3. DG ECHO Thematic Policy Document n° 5: Disaster Risk Reduction: Increasing resilience by reducing disaster risk in humanitarian

action.

Vietnam: Schoolchildren

participate in a Disaster

Preparedness class

organised by the

NGO PLAN, funded by

DG ECHO. © Cecile

Pichon, June 2011,

DG ECHO.

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

6

2. International and EU

Policy Frameworks

DG ECHO’s work in disaster preparedness is firmly grounded in international and

EU policy frameworks that provide orientation to DRR, humanitarian assistance,

and climate change. The main frameworks of reference are presented in this

section, others with relevance to specific issues will be mentioned as necessary

throughout the Guidance.

2.1 International frameworks

2.1.1 Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (Sendai Framework)

is a global non-binding agreement outlining seven targets and four priorities for

action to prevent and reduce existing and new disaster risk. In keeping with DG

ECHO’s principles and risk-based approach to preparedness (see Chapter 5), the

Sendai Framework places strong emphasis on anticipatory risk management and

on a wide scope of action - including small-scale and slow-onset disasters as well

as human-induced, technological, environmental and bio hazards. It also strongly

embraces principles such as protecting people from the risk and impact of disasters

as well as an all-of-society approach, based on non-discriminatory participation, the

empowerment of local communities and increased collaboration among all relevant

stakeholders, including academia, the scientific community and the private sector.

Importantly, the Framework clearly recognises the “need to further strengthen

disaster preparedness for response, take action in anticipation of events, integrate

disaster risk reduction in response preparedness and ensure that capacities are in

place for effective response and recovery at all levels”

4

. As such, DG ECHO’s work in

preparedness is a primary contribution to the implementation of Sendai Priority 4:

‘Enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response, and to “Build Back Better”

in recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction’.

2.1.2 Grand Bargain - the Agenda for Humanity

The Grand Bargain is an agreement of nine commitments

5

between donors

and humanitarian organisations, launched during the World Humanitarian

Summit (WHS) in 2016, aimed at improving the effectiveness and efficiency of

humanitarian aid.

4. Sendai Framework page 21.

5. 1. Greater Transparency, 2. More support and funding tools to local and national responders, 3. Increase the use and coordination

of cash-based programming, 4. Reduce Duplication and Management costs with periodic functional reviews, 5. Improve Joint and

Impartial Needs Assessments, 6. A Participation Revolution: include people receiving aid in making the decisions which affect their

lives, 7. & 8. Increase collaborative humanitarian multi-year planning and funding & Reduce the earmarking of donor contributions;

9. Harmonize and simplify reporting requirements.

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

7

As a signatory of the Grand Bargain, DG

ECHO contributes to the implementation of

all commitments. Its disaster preparedness

approach specifically aims to increase the

efficiency and effectiveness of the response

and it is specifically relevant to Commitment

N°2 (More Support and Funding Tools to

Local and National Actors) as this helps to

strengthen the capacity of first responders

- including national and local governments,

communities, Red Cross and Red Crescent

National Societies and civil society. Reinforcing local capacity is an explicit

objective of DG ECHO, which recognises that the localisation of humanitarian

action is a means for increasing sustainability and strengthening the resilience

of crisis-affected people.

2.1.3 Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement establishes a long-term goal to limit global temperature

rise to ‘well below 2° Celsius’ and to pursue efforts to limit the rise in temperature

before the end of the century to 1.5°C. In addition to establishing a legally-

binding framework to guide global efforts for this purpose, the Agreement also

aims to increase the ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change

and foster climate resilience. The EU is supporting partner countries to do so,

recognising the critical importance of adaptation and disaster risk management

in the global response to the climate crisis.

Closer to DG ECHO’s mandate, the Paris Agreement recognises the importance

of averting, minimising and addressing loss and damage

6

associated with

the adverse effects of climate change. The Agreement calls for enhanced

cooperation, action and support in different areas, including those in which DG

ECHO operates, such as early warning systems, and emergency preparedness.

6. https://unfccc.int/wim-excom

“

DG ECHO’s disaster

preparedness activities are firmly

grounded in international and EU

policy frameworks that provide

orientation in DRR, humanitarian

assistance, and climate action.

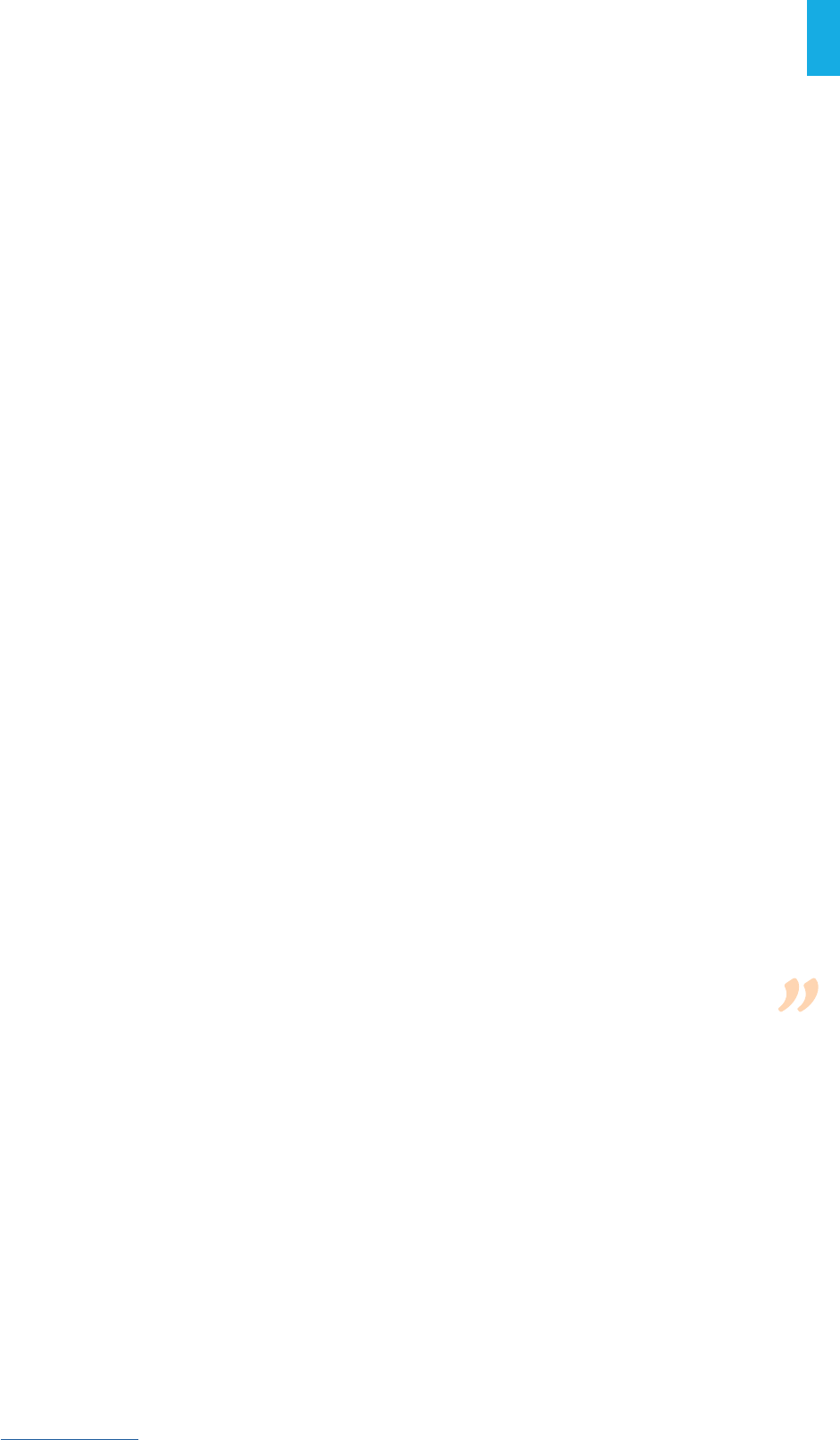

Thanks to improved

coordination mechanisms

between different levels

of administration,

professional rescue teams

sent by the municipality

also form part of the

disaster management

mechanism – travelling

by boat to reach

remote villages such

as Tigdaranao. © EU/DG

ECHO/Pierre Prakash

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

8

2.1.4 The Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted in 2015, form a plan

to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all. They address global

challenges, including poverty, inequality, food insecurity, climate change,

environmental degradation, peace and justice. DG ECHO’s actions contribute to

many SDGs, in particular SDG 13 on climate change, which is directly linked to

disaster preparedness and early action.

With the adoption of the European Green Deal in 2020 and its overall resilience and

recovery approach, the European Commission is contributing to the 2030 Agenda for

Sustainable Development.

2.2 EU policy frameworks

2.2.1 Preparedness and DG ECHO’s Mandate

Preparedness is embedded into DG ECHO’s mandate as provided by the Council

Regulation No 1257/96 of 20 June 1996. Article 1 mentions that ‘aid shall also

comprise operations to prepare for risks or prevent disasters or comparable

exceptional circumstances”. Furthermore, Article 2.f stipulates that operations

should ensure preparedness for risks of natural disasters or comparable exceptional

circumstances and use a suitable rapid early warning and intervention system.

In line with these articles, support for better preparedness has been gradually

mainstreamed in the majority of DG ECHO funded humanitarian aid programmes.

Preparedness and risk reduction concerns are included in all DG ECHO thematic

humanitarian aid policies, namely: Cash; Disability; Education in Emergencies; Food

Assistance; Gender; Health; Nutrition; Protection; Shelter and

Settlements; and Water, Sanitation and Hygiene.

In 1996, DG ECHO created a dedicated programme

and budget line to strengthen preparedness capacities

in partner countries: the Disaster Preparedness ECHO

Programme, DIPECHO. Initially rolled out in the Caribbean

region, the programme was progressively expanded to

eight regions

7

. DIPECHO has allowed DG ECHO to support

its partners in strengthening the quality, timeliness and

effectiveness of a more localised

8

humanitarian response,

and it has shown that investing in preparedness and risk

reduction is efficient and contributes to saving lives

9

. In

addition to community-based interventions, DIPECHO

has helped to design national and regional platforms for

practitioners which allow them to regularly discuss best

practices and lessons learnt.

Since 2015, the DIPECHO approach has focused more strictly on disaster

preparedness and early action to avoid overlaps with long-term development

instruments used for disaster risk reduction. The programming was streamlined

7. Caribbean, Central America, South America, South East Asia, South Asia, Central Asia and Southern Caucasus, Southern Africa

including the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific. Even though never formally qualified as a DIPECHO project, a similar approach

was developed in the Horn of Africa, which focused on drought from 2006 to 2012 before it was embedded in the countries’

interventions and linked to the resilience agenda.

8. Reflecting the localisation agenda, “localised” here refers to the capacity of in-country actors, both at national and local level.

9. Cf. also international studies such as the Centre for Climate Research - CICERO’s document Disaster Mitigation is Cost-Effective..

DG ECHO’s mission is to preserve lives,

prevent and alleviate human suffering

and safeguard the integrity and dignity

of populations affected by a crisis. DG

ECHO’s protection mandate is also to

encourage and facilitate cooperation

between the 33 EU Members and

participating States in the EU Civil

Protection Mechanism (UCPM) in order

to improve the effectiveness of systems

for preventing and protecting against

natural, technological or human-induced

disasters in Europe.

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

9

around five priorities

10

and the funding

allocation agreed in accordance with country

or regional strategies.

DIPECHO evaluations

11

recommended a more

focused and coherent multi-year preparedness

strategy in countries where operations were

taking place. Specifically, they highlighted the

critical importance of: i. increasing support

to strengthen the capacity of Disaster Risk

Management authorities to complement the

support given to communities, which was

the main focus of DIPECHO interventions; ii.

improving risk/vulnerability analysis as the

basis for preparedness programming; and iii.

strengthening collaboration with development

actors. Additionally, all the evaluations

highlighted the need to increase coordination

with Civil Protection bodies, including the UCPM.

The 2021 renewed DG ECHO DP approach recognises and builds on the multiple

strengths of the DIPECHO programme and its pioneering role in supporting disaster

preparedness via a community approach, by linking community-based approaches

with national and regional systems. It also provides guidance on how to implement

evaluation recommendations and improve coherence and effectiveness.

2.2.2 European Consensus on Humanitarian Aid

The European Consensus on Humanitarian Aid which was adopted in 2007,

is the core policy framework that guides the EU’s humanitarian action,

ensuring that it complies with humanitarian principles

12

. The Consensus clearly

recognises the increasingly complex, multi-hazard/threat nature of current

crises, and takes into account the multiplying effect of climate change, and the

overlapping of disasters and situations of conflict and fragility. The Consensus

also acknowledges that preparedness is essential to saving lives and enabling

communities to increase their resilience to shocks and, therefore, capacity

building in this area is viewed as an integral part of EU humanitarian action.

2.2.3 European Communication on Humanitarian Action

The Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council

on the EU’s Humanitarian Action: New Challenges, Same Principles (2021) places a

clear emphasis on the need for preparedness and anticipatory action in responding

to climate impacts and addressing environmental concerns through humanitarian aid.

Preparedness is viewed as integral to humanitarian action and a key element of the

broader, longer-term disaster risk reduction agenda. In this respect, the Communication

highlights how the humanitarian-development-peace nexus approach as a primary

vehicle by which to achieve the complementary objectives of disaster risk reduction

and preparedness. The Communication also underlines how anticipatory approaches to

10. 1. Linking Relief Rehabilitation and Development (LRRD) – Disaster Preparedness as part of recovery strategies - opportunities

to build back better; 2. Recurrent and predictable crises - National DP systems, contingency planning and surge models into

key services - e.g. health (epidemic), food security, shock responsive safety nets; 3. Urban preparedness with an emphasis on

mega cities, hence including Asia and the LAC region; 4. Ongoing crises or situations of fragility - early response mechanisms;

5. Institutional partnership with UCPM in support of CP administrative agreements.

11. 2013 Global, 2013 Central Asia, 2016 Latin America and Caribbean, and 2017 Southern Africa and Indian Ocean.

12. The principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence.

Nepal: 3 years aer

the earthquake,

DanChurchAid conducts

regular awareness

sessions on Disaster

Risk Reduction with local

communities © European

Union 2018 (photo by

Pierre Prakash)

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

10

humanitarian action can help to bolster community resilience, including that of forcibly

displaced people, in regions vulnerable to climate-related and other hazards.

2.2.4 European Consensus on Development

The European Consensus on Development (2017) frames the action of EU

institutions and Member States (MS) in their cooperation with all developing

countries. Responding to the Agenda 2030, the Consensus includes assistance

to populations and countries affected by disasters (natural and human-induced

hazards and threats) among its core objectives. The Consensus clearly mentions

the key role of preparedness in reducing risk, and strengthening resilience to

withstand and recover from shocks and disasters (Article 70), in accord with the

Sendai Framework.

2.2.5 EU Joint Communication on Resilience

The Joint Communication, A Strategic Approach to Resilience in the EU’s external

action (2017), strongly positions resilience as a central priority of the EU’s external

action, and establishes better anticipation, risk reduction and disaster preparedness

as integral components of the EU’s approach. The Communication explicitly states

that resilience requires risk-informed programming for responses to all crises and

situations of fragility. With risk reduction at their core, the EU’s resilience approach

and the Sendai Framework are complementary and mutually reinforcing.

2.2.6 The European Green Deal

The European Green Deal (2019) aims to make Europe the first climate-

neutral, climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable continent by 2050

through a series of actions and measures underpinned by the core principles of

environmental sustainability, climate neutrality and climate resilience.

The vision of the European Green Deal is also expected to guide the external

action of the EU, including in humanitarian aid. Mainstreaming preparedness,

as well as climate and environmental concerns, in humanitarian action will

increase resilience among those who receive EU Aid.

2.2.7 EU Adaptation Strategy

As an essential element of the European Green Deal, the interface between climate

change and DRR is also central to the EU Adaptation Strategy. This strategy

includes an external dimension (i.e. related to non-EU countries) for the first time,

in recognition of the interconnectedness of risks as well as the EU’s responsibility

to help the most vulnerable, including those most affected by climate change. The

new strategy also responds to the need for better preparedness and has dedicated

measures on anticipatory action: climate change adaptation is about understanding,

planning and acting to prevent the impacts in the first place, minimising their

effects, and addressing their consequences.

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

11

This section presents DG ECHO’s Preparedness and Risk Informed Approach.

It is critical that, when working together, DG ECHO and humanitarian partners are

on the same page in terms of the language they use, given that there may be

differences in emphasis in the broader humanitarian sector. It is also important to

keep in mind that the meaning and application of the approach, and some of its key

elements, may continue to evolve.

DG ECHO recognises that the effectiveness of a response depends on investments

in preparedness, as a component of risk management. It also recognises that a

risk-informed approach is crucial to reduce the humanitarian needs caused by risks.

To this end, it seeks to mainstream preparedness and a risk-informed approach in

all of its response operations. And as a complementary measure, it also promotes

targeted preparedness actions as a specific way of strengthening preparedness

for response and early action.

Although preparedness and risk-proofing are intrinsic to humanitarian action, DG

ECHO acknowledges that development actors play a key role in scaling up and

complementing these interventions, and thus ensuring their long-term sustainability.

As such, DG ECHO promotes a nexus approach with development actors as the

primary implementation modality for preparedness and risk

reduction and seeks concrete opportunities to promotethis

way of working.

While this chapter focuses on DG ECHO’s mainstreaming

and targeted preparedness approach, the nexus approach

is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5, together with

other implementation modalities.

3.1 Disaster Preparedness

Preparedness allows for an early and efficient response

and therefore helps to save lives, reduce suffering and pre-

empt or decrease the extent of needs. In this way it lessens

the impact of a hazard and/or threat and contributes to

resilience. In particular, DG ECHO views preparedness as a

way to promote

anticipatory actions, early response,

and flexibility

which are critical to managing disasters

(see box for definition) more efficiently and effectively,

and mitigating their impact.

Disaster preparedness is ‘the knowledge and capacities

developed by governments, response and recovery

organizations, communities and individuals to effectively

3. Preparedness & Risk

Informed Approach

Disaster

DG ECHO’s definition of the term

disaster

includes all events, as follows:

• Natural hazards such as earthquakes,

cyclones/hurricanes, storms, tsunamis,

floods and drought;

• Conflict and violence;

• Disease outbreaks and epidemics, such

as Ebola or Covid-19;

• Technological and industrial hazards.

DG ECHO mainly interprets disasters

as humanitarian crises, which are

understood by the European Commission

as events or series of events which

represent a critical threat to the

health, safety, security or wellbeing of

a community or other large group of

people. A humanitarian crisis can have

natural or human-induced causes, can

have a rapid or slow onset, and can be of

short or protracted duration.

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

12

anticipate, respond to and recover from the impacts of likely, imminent or current

disasters’ (UNDRR, 2017). DG ECHO embraces this definition and understands

preparedness as an important component of the larger work on Disaster Risk

Management.

Although preparedness does not address the structural causal factors of disasters, it

complements the longer-term risk management strands (Prevention, and Recovery)

that sit within a developmental approach and are within the remit of other services

of the European Commission.

As a humanitarian donor, DG ECHO views ‘hazardous events’ as encompassing

both natural hazards and human-induced threats. It views

preparedness as relevant to all types of hazards and

threats in a given context.

3.2 Risk Informed Approach

EU Humanitarian Aid aims to support people in addressing their

needs and managing the risks they face. As such, a sound assessment of these needs

has to be carried out, based on evidence and regular updates, and factoring in an

accurate assessment of the risks people face. In line with the 2016 World Humanitarian

Summit’s commitment to anticipate and better manage risks and crises, a needs-

based approach must consistently integrate risk assessment and analysis.

This allows existing and potential risks to be evaluated and action taken before a crisis

hits or a situation deteriorates, thus reducing suffering and humanitarian needs.

DG ECHO’s risk-informed approach therefore implies that all humanitarian actions

are designed based on an assessment and understanding of risks, and are

implemented to respond to and possibly reduce these risks, with the final objective

of mitigating their impact.

Risk is “the combination of the consequences of an

event or hazard and the associated likelihood of its

occurrence” (ISO 31010) as defined in the Commission

staff working paper Risk Assessment and Mapping

Guidelines for Disaster Management (2010).

• Hazard/Threat & Exposure:

Depending on

the context and the nature of the hazard, this

dimension of risk may be reduced by measures

including prevention or reducing the occurrence or

extent of the hazard/threat and by reducing the

exposure of people to the impact of the hazard/

threat.

• Vulnerability:

Reducing the vulnerability

of exposed people will reduce their risk.

Vulnerability is not a fixed criterion attached to

specific categories of people, and no one is born

vulnerable per se. In this regard, it is particularly

important to target the most vulnerable groups,

based on an intersectional analysis (sensitive to

gender, age, disability, ethnicity, displacement

etc.).

• Coping Capacity:

Increasing coping capacity

lowers the level of risk. This covers a very

broad area and requires careful analysis to

target investments in capacity development. It is

closely linked to the development of resilience.

Experiences, knowledge and networks strengthen

the ability to withstand adverse impact from

external stressors. The development of many

elements of capacity (such as communication

and organisational capacities) helps reduce the

risk from a wide range of hazards/threats.

RISK =

VULNERABILITY

COPING CAPACITY

HAZARD

AND/OR THREATS X

Risk

“

EU Humanitarian Aid

aims to support people in

addressing their needs and

managing the risks they

face.

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

13

The concept of risk involves forecasting the probability of future harm. As such, it

involves the capacity for anticipation and dealing with uncertainty.

Effective risk management involves a number of strands, including:

• Prevention (Risk Reduction)

• Preparedness

• Response

• Recovery

These strands are closely connected and overlapping, as illustrated in the graph below.

DG ECHO’s support focuses primarily on preparedness and response. Within these

strands, DG ECHO applies a risk-informed approach by:

• Mainstreaming preparedness in, and risk-proofing, response operations

by integrating risk reduction measures (henceforth referred to simply as

‘mainstreaming’);

• Targeted preparedness actions (see chapter 6 for a detailed overview of

targeted preparedness actions).

Both ‘mainstreaming’ and ‘targeted preparedness’ actions are based on a

comprehensive risk assessment. Similarly, risk assessment is key to the design

of effective anticipatory actions, which are another important element of a

risk-informed approach. The following sections focus on risk assessment,

anticipatory action, mainstreaming and targeted preparedness.

Graph 1. Risk management strands

PREPAREDNESS

PREVENTION

TIME

RESPONSE

RECOVERY

ANTICIPATORY

ACTION

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

14

3.2.1 Risk Assessment

Risk assessment must be the basis for designing interventions and should be

considered an integral part of all humanitarian action. Risk assessment should always

be context-specific, examining each situation individually, thus avoiding generalisations

or assumptions, and with a view to generating information that is precise enough to

inform programming decisions. Particularly relevant for humanitarian action are the

following key questions to guide the assessment:

• What are the main hazards/threats faced by people in their context, and what

level of impact or consequences do these have?

• How likely is the hazard/threat to occur (i.e. probability)?

• What level of exposure do people have to these hazards/threats?

• How vulnerable are people to these risks, noting that different groups have

different vulnerabilities?

• What is the coping capacity of the community?

As far as is practicable, a risk assessment should be conducted from the perspective

of the affected population, thus ensuring their engagement in the analysis, decision-

making and implementation of the assessment itself. It should identify risks related

to specific hazards and threats and each component should be disaggregated to a

detailed level. It should reveal the specific dynamics of the situation and help identify

ways that interventions can reduce the associated risks. Risk assessment and risk

analysis should be a continuous process, rather than taking place only at

fixed points within the programme cycle.

Data for risk assessments can come from commercial and open-source

satellite images and maps

13

, project reports from national and international

13. Low Resolution free imagery: https://www.sentinel-hub.com/ (ESA Sentinel 2/3 imagery and NASA Landsat 8); Medium

Resolution commercial imagery: Planet Labs; High Resolution commercial imagery: DigitalGlobe; Historical data available at:

Google Earth Pro, Yandex, Bing.

TARGETED

PREPAREDNESS

RISK INFORMED

HUMANITARIAN

ACTION

Exposure

RISK

Hazard

Vulnerability

socio-economic

Lack of coping

capacity

Gap analysis

Anticipatory actions

Strengthening

Preparedness within

a response

Risk-proofing of response

Build Back Better (BBB)

Greener humanitarian

response

EWS

Contingency planning

Stockpiling

Capacity building

Graph 2. Risk Informed Humanitarian Action

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

15

environmental agencies, local knowledge, environmental assessments, national/

international environmental databases, wildlife and fisheries management

plans, development plans, and land tenure records

14

, climate trends, projections

and adaptation options

15

.

Considering the unfolding climate and environmental crisis, analysis of current and

future risks stemming from both climate change and environmental degradation

should be included in all risk assessments to identify interlinkages and priorities

for action in specific contexts. Although their causes can be different, the result

of environmental degradation (i.e. environmental hazards) can be the same

as that of climate-related hazards, and they

can be made more severe by climate change.

For example, climate change can increase the

risk of landslides through increased heavy

rain over time. Deforestation, particularly on

hillsides, can also increase the risk of landslides

by destabilising the soil. Furthermore, climate

change impacts and environmental degradation

can also exacerbate existing tensions, increasing

risk of conflict and can therefore be seen as

“threat multipliers”

16

. As such, risks should not

only be assessed individually but their interacting

nature should also be considered, to identify so-

called ‘compounding’ risks, for example that of

climate and environment crises interacting with

conflict risk, and compounding vulnerabilities.

Multi-risk analyses can make use of different

context-specific environmental data sources,

e.g. climate data, the location of protected

areas, vegetation/land cover, measurements

of pollution (including information on areas

where there are hazardous and toxic materials),

topographical and hydrological data, biodiversity

levels, the availability of natural resources, and

natural hazard data

17

.

Finally, it should still be a priority to ensure the

meaningful participation and involvement of

meteorological agencies (governmental and

non-governmental), climate organisations and

research institutes, civil society (including affected

communities), grassroots associations, academia,

voluntary work organizations, and affected

populations, including the most vulnerable,

marginalized and exposed groups, in designing

and carrying out an effective and comprehensive

risk assessment. This, in turn, increases the

ownership of preparedness measures and

mechanisms implemented to counter the risks

that have been jointly identified.

14. https://ehaconnect.org/preparedness/environmental-situation-analysis/how-to-guide/

15. World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal.

16. EU, 2008. Paper from the High Representative and the European Commission to the European Council: Climate Change and

International Security. S113/08, 14 March 2008.

17. https://ehaconnect.org/preparedness/environmental-situation-analysis/how-to-guide/

“

Considering the unfolding

climate and environmental crisis,

analysis of current and future

risks stemming from both climate

change and environmental

degradation should be included

in all risk assessments to identify

interlinkages and priorities for action

in specific contexts.

This is a drill in which

recently trained brigades

perform rescue operations

saving people from

collapsed buildings during

a fire in Nicaragua’s

capital Managua.

© 2013 - © Spanish

Red Cross

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

16

3.2.2 Anticipatory or Early Action

18

Anticipatory or Early Actions (AA and EA) are taken

when a disaster is imminent (or, in the case of a slow-

onset disaster, when it is about to reach a peak).

Therefore, they are carried out before a crisis occurs, or

before a significant development within a crisis. Early

actions are implemented according to a pre-determined

protocol, which describes the activities to be undertaken

and pre-agreed triggers established on the basis of

historical and current forecast analysis. Ahead of a

crisis, forecasts are combined with risk, vulnerability and

exposure indicators to develop an intervention map, and

dedicated funds are defined to be quickly released when

pre-agreed thresholds are reached. Anticipatory action

thus reduces the vulnerability of affected communities

and strengthens their capacity to manage an emergency

and to safeguard their assets. As such, anticipatory

action is integral to risk management as it helps pre-

define needs and respond to them more effectively, and

thus reduce the impact of a hazard or threat on lives and

livelihoods. In so doing, it complements preparedness as

part of an effective response and, as such, it is also part

of preparedness. Anticipatory action is further discussed in section 6.2.

Early Response

(ER) refers to actions that are undertaken right aer a disaster

occurs. Anticipatory (or early) action is different from ‘early response’ insofar as

the former begins before the hazard and/or threat strikes whereas the latter begins

aer it has struck. “In contrast to anticipatory action, early response is based on an

evidenced hazard/threat and observable rather than forecasted needs and does not

require pre-agreed implementation plans”

19

.

3.2.3 Mainstreaming Preparedness and Risk Proofing Response Interventions

In line with a risk-informed approach, DG ECHO aims to risk proof its humanitarian

response interventions by mainstreaming preparedness and integrating risk

reduction measures. The objective is to make humanitarian assistance more

effective, while increasing the coping capacities and resilience of communities

at risk, and ultimately reducing the need for external assistance. Except in

duly justified cases, preparedness actions should therefore be systematically

mainstreamed into humanitarian operations to strengthen the capacity to

respond to a crisis within a crisis (e.g. sudden floods during a conflict) or any

recrudescence or aershock.

To make humanitarian action more effective, response interventions should be

designed to reduce immediate and imminent risks, and not add new risks (the

‘do no harm’ principle). By

risk-proofing

humanitarian interventions, they are

protected against imminent hazards and threats

20

. Risk-proofing considerations

should be specifically interpreted according to the local context, the nature of

the hazardous/threating event and tailored to the best suited humanitarian

18. For DG ECHO anticipatory actions and early actions are the same concept. In this guidance, they will be used interchangeably,

so in the paragraph 6.2 on anticipatory actions we refer also to early actions.

19. https://cerf.un.org/sites/default/files/resources/CERF_and_Anticipatory_Action.pdf

20. For example: ensuring water points are located above high water levels in flood-prone areas so they are not damaged by floods

or incorporating adequate fire-protection in shelter.

Floods risk assessment

and anticipatory actions

Ahead of flooding peaks, it is possible

to quickly disburse unconditional multi-

purpose cash grants and distribute

non-food items to transport goods

and purify water. The potential at risk

population and high-risk areas of action

should be pre-selected on the basis of a

risk and vulnerability assessment ahead

of the disaster. Targeting should be

adjusted once the hazard impact area can

be forecast more concretely. For reference

see examples in Bangladesh (July 2020)

by the World Food Programme (WFP) and

the Bangladesh Red Crescent Society.

Note: This action was supported through DG ECHO’s

funding via IFRC’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund

(DREF).

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

17

action. Risk reduction measures, however, remain relevant to every sector of

humanitarian assistance. Before and during their implementation, it is important

to consider the linkages between sectors. Further guidance on preparedness

and risk proofing of response operations can be found in the humanitarian

policies of DG ECHO, mentioned in section 2.2, as well as in Annex 1.

In addition to specific guidance on how to integrate preparedness and risk

reduction into humanitarian assistance, DG ECHO has developed two tools, the

Resilience Marker (RM), and the Crisis Modifier (CM) (see Annex 2), to ensure that

programming is risk-informed and that there is a greater degree of financial

flexibility in humanitarian action in order to respond to crises within crises.

The Resilience Marker is included in the DG ECHO electronic Single Form (eSF)

and allows partners to verify whether their programming is effectively based

on a systematic analysis of risks, and how the action addresses these risks and

avoids creating new risks from the design stage. The Crisis Modifier promotes

systematic consideration of preparedness through the integration of a flexible,

early action component to address, in a timely manner, immediate and life-

saving needs resulting from a rapid-onset crisis or a deteriorated situation

21

within a DG ECHO-funded action.

The priorities and funding for humanitarian response operations are included

in the regional and/or country Humanitarian Implementation Plans (HIPs),

regularly published by DG ECHO.

21. For example, although a drought is a slow onset crisis, it could trigger acute malnutrition rapidly.

Women experts reaching

remote communities

in Nicaragua. ©EU

2013- Photo credits:

EC/DG ECHO/Silvio

Balladares

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

18

3.2.4 Targeted Preparedness Actions

Targeted preparedness refers to actions taken in

advance of a hazardous and/or threatening event

and aimed at improving the effectiveness of the

response to it. This can involve, for example,

the development of early warning systems,

reinforcing the link between early warning and

early action, the development of contingency

plans, anticipatory actions, the emergency

prepositioning of stock, and overall capacity

building for early action/early response, etc.

The Disaster Preparedness Budget Line is

DG ECHO’s dedicated source of funding

22

for

targeted preparedness actions at regional and

country levels. It allows support for preparedness

to be extended beyond DG ECHO’s regular

humanitarian funding modalities.

As of 2021, the DP Budget Line is structured

around a set of global priorities, for a period of

five years, in order to maximise the strategic

use of this funding, and bring more focus and

coherence to DG ECHO’s support to disaster

preparedness across regions. Regional and

country actions will have to mirror one or more

of these priorities, while ensuring that they are

tailored to the specific needs of local contexts

(country and/or regional level). The 2021-2024

priorities are detailed in Annex 3, which will be

regularly updated as the priorities evolve.

The DP Budget Line replaces the previously available DG ECHO Preparedness

Programme (DIPECHO). The DP Budget Line is allocated under the Humanitarian

Implementation Plans HIPs), complementing the budget dedicated to humanitarian

response operations. Funding for humanitarian response and for preparedness is

managed under the same framework to provide a more coherent and cohesive

approach, and to further mainstream preparedness into humanitarian assistance.

22. EUR 75 million in 2021.

Emergency Toolbox

The Emergency Response Coordination Centre

(ERCC)’s instruments include the Emergency

Toolbox, which is a fund that specifically provides

humanitarian assistance to respond to fast-onset

crises that could not be foreseen in DG ECHO’s

humanitarian implementation plans.

Three of

the four tools within the Toolbox can be used for

disaster preparedness

as well as response:

• The Small-scale Tool is used to assist a limited

number of people (< 100,000) affected by a

natural hazard or human-induced disaster.

This includes the deployment of preparedness

activities. All DG ECHO partners can access

these tools by submitting a proposal through

the DG ECHO electronic Single Form.

• The Epidemics Tool is used to prevent and

respond to epidemic outbreaks, and is available

to all DG ECHO partners through the DG ECHO

electronic Single Form.

• The IFRC’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund

(DREF) and Forecast-based Action by DREF

provide National Red Cross and Red Crescent

Societies with funds for early action or for

response.

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

19

Humanitarian principles

The humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence,

enshrined in the European Consensus on Humanitarian Aid, guide DG ECHO’s disaster

preparedness activities, which are an integral part of humanitarian action. The

humanitarian projects that DG ECHO funds aim to preserve life, and prevent and

alleviate suffering. They also have to adhere to the do no harm principle to avoid

exposing people to additional risks.

Multi-hazard and multi-threat

Crises are becoming more complex, with natural hazards increasingly overlapping

with human-induced ones, or with unprecedented biological hazard situations like the

COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Consequently, preparedness applies to any type of crisis

and covers all types of risks, from natural and biological hazards, to human-induced

threats, such as technological hazards (e.g. industrial), conflict and violence.

People centred

For DG ECHO, humanitarian action starts with affected people and communities.

Interventions aim to meet, or contribute to meeting, the basic needs of affected

populations, addressing needs in a demand-driven way. DG ECHO acknowledges

that effective humanitarian action requires the participation of, and accountability

towards, affected people. DG ECHO also recognises that, in addition to needs and

vulnerabilities, affected people - including first responders - have the capacity to

manage the risks they face.

Humanitarian projects must be people-centred,

prioritising their impact on people’s lives and

livelihoods. By promoting this approach, DG ECHO

contributes to strengthening people’s resilience

and ensures that preparedness and response

measures address the needs of all, without

barriers, so that no one is le behind.

In pursuing its people-centred approach, DG

ECHO will take note of the provisions in the Grand

Bargain and good practice as elaborated in the

Core Humanitarian Standard.

4. Key Elements of the

DG ECHO Preparedness

and Risk-Informed Approach

With funding from

DG ECHO, PAH is

implementing and

coordinating water

and sanitation related

projects,as well as

improving preparedness

in emergency prone areas

of South Sudan. ©Tomasz

Woźny / PAH

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

20

Gender, age and diversity sensitivity

Integrating gender and age enhances the quality of humanitarian programming,

in line with the EU’s humanitarian mandate. Aid that is not gender- and age-

sensitive is less effective. It risks not reaching the most vulnerable people or failing

to respond adequately to their specific needs. Furthermore, a comprehensive

understanding of vulnerabilities must take an intersectional approach, considering

multiple aspects of diversity, which can intersect with gender to produce multiple

discrimination and exacerbate vulnerability

23

. These aspects influence the impact

that crises have on people, as they affect both vulnerabilities and capacities, and

hence their exposure to risk. This means that risk assessment, and the associated

preparedness and response measures, must fully factor in the particular

characteristics of different groups (age, gender, ability, ethnicity, social status,

etc.) and their circumstances (rural, urban, displaced, wealth and income).

Conflict sensitivity

DG ECHO recognises that violence and conflict are either a key driver or a risk

multiplier in many crises. Hence, all interventions should adopt a conflict sensitive

approach. Conflict sensitivity is defined as the ability of an organization to understand

the context in which it is operating, and the interaction between the intervention

and the context, and thus avoid negative impacts and maximise positive impacts

24

.

The Centrality of protection

All humanitarian actors need to take protection into account in their programming

- in line with the Inter-agency Standing Committee (IASC) Principals’ statement on

23. DG ECHO Thematic Policy N° 6, Gender: Different Needs, Adapted Assistance.

24 Adapted from International Alert et al., 2004. Conflict-sensitive approaches to development, humanitarian assistance and

peacebuilding: a resource Pack. London: International Alert

In Vanuatu, Disaster

Preparedness measures

in such small and isolated

communities take

time and effort but the

appreciation expressed by

the communities for such

assistance is heartfelt.

© EU 2012 - Story

and photo credits: EC/DG

ECHO/Mathias Eick

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

21

the Centrality of Protection which emphasises the importance of protection and

contributing to collective protection outcomes in all aspects of humanitarian action.

Protection should be central to humanitarian preparedness efforts, and should be

taken into account throughout the duration of the humanitarian response and beyond.

Strengthening local capacity

Anticipatory action and enhanced predictability of response can only be achieved if

local

25

preparedness and response capacities are in place as per the Grand Bargain

commitments. Therefore, preparedness actions must strengthen first responders’

capacity to act as locally and as early as possible.

While recognising the importance of capacity

strengthening within communities, and of

maintaining a strong focus on it, DG ECHO

appreciates that it needs to be well anchored, and

should complement the capacity of state disaster

management systems at the national and local

levels as much as possible. A system wide approach

is encouraged to ensure linkages and simultaneous

capacity-building at community and governmental

level, whenever possible, whilst respecting the do no

harm principle, and other humanitarian principles.

Context specificity

Local context is crucial in shaping risks, vulnerabilities, capacities and the needs of

populations and countries affected, or with a potential to be affected, by a crisis.

Preparedness interventions should therefore always respond, and be adapted, to the

context, including in the choice of target beneficiaries and partners.

Climate change and environmental degradation

Climate change and environmental degradation are risk multipliers

26

. Climate change

is increasing the frequency and severity of both sudden-onset and slow-onset

climate-related hazards

27

. This, in turn, is increasing humanitarian needs and posing

greater challenges to humanitarian action (e.g. scale or geographical distribution). It

is increasingly clear that environmental degradation can also trigger significant and

protracted humanitarian crises, e.g. by exposing human food systems to increased risk

of failure through droughts or by increasing the risk of the re/emergence of zoonotic

diseases and increasing human exposure to diseases. In addition, climate change is

an accelerating factor in environmental degradation, including land degradation and

biodiversity loss. The impact of climate change and environmental degradation can

also exacerbate existing tensions, increasing the risk of conflict. As current and future

climate change and environmental degradation may increase the risks faced by people

in affected areas, and may jeopardise the effectiveness of interventions themselves,

these phenomena should be accounted for in humanitarian action. See section 6.11.1

on climate and environmental resilience interventions.

25. Local refers to both national and local government actors, civil society, academia, private sector and communities. It also

includes international partners working in country in support of preparedness and response systems.

26. EU, 2008. Paper from the High Representative and the European Commission to the European Council: Climate Change and

international security. S113/08, 14 March 2008.

27. IPCC, 2013: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fih Assessment Report

of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels,

Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp.

“

Protection should be

central to humanitarian

preparedness efforts, and should

be taken into account throughout

the duration of the humanitarian

response and beyond.

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

22

The implementation and effectiveness of disaster preparedness interventions relies on

cooperation with key actors, notably development and peace actors. In this light, when

mainstreaming and in targeted preparedness actions, DG ECHO will work in a nexus

approach with development and peace actors, and will establish and/or strengthen

partnerships with key stakeholders and with the UCPM. This chapter provides an

overview of the implementing modalities that complement mainstreaming and

targeted preparedness.

5.1 Humanitarian Development Peace (HDP) Nexus

The recurrent, protracted and complex nature of many crises re-enforces the

importance of designing interventions that address development and peacebuilding

challenges as well as humanitarian needs. This can be done through the Humanitarian

Development Peace (HDP) nexus approach, which is based on the shared vision and

collective effort of the EU, its Member States, and its partners, and stems from the 2017

Council Conclusions: “the Council stresses the importance of investing in prevention

and addressing the underlying root causes of vulnerability, fragility and conflict while

simultaneously meeting humanitarian needs and strengthening resilience, thus reducing

risks”. Within this, resilience is a central objective of EU development and humanitarian

assistance.

DG ECHO fully adheres to the nexus approach and the idea of engaging with development

and peace actors in preparedness activities, and throughout humanitarian operations,

in order to increase their sustainability and promote resilience.

DG ECHO’s preparedness actions, be they mainstreamed or

targeted, need to be undertaken in a way that complements and/

or reinforces ongoing or future, relevant development initiatives.

DG ECHO funded preparedness actions should therefore, whenever

possible, include an exit strategy that addresses the issues of

scaling up and integrating elements into longer-term risk reduction

and development interventions. This entails the establishment of

a close relationship, and the sustained exchange of information

and coordination between DG ECHO and the European Commission

development services (DG INTPA and DG NEAR) at both HQ and

field levels, as well as between partners. Partners with experience

and expertise across the humanitarian and development spectrum,

including in conflict zones, are particularly well placed to support the

design and implementation of mutually-reinforcing humanitarian-

development interventions, and bringing together funding from

humanitarian and development donors.

5. Complementary

implementing modalities

Nexus in practice:

an example

from Chad

Close coordination between

development and humanitarian

interventions in Chad has been

underway for several years.

For example, DG ECHO and DG

INTPA are working together

to deliver nutritional services

to children and to establish

a unified social register for

ambitious social safety nets

that strengthen food security.

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

23

A joint crisis context analysis is an essential step of

a nexus approach, allowing risks and vulnerabilities

to be identified, and humanitarian and development

actors to define entry points/areas for collaboration,

complementary action and mutually-reinforcing

initiatives. Joint post-crisis needs assessments can

also help to facilitate dialogue and promote the

systematic integration of preparedness, risk and

vulnerability concerns into both humanitarian and

development interventions.

The targets set out by the EU Neighbourhood,

Development and International Cooperation

Instrument (NDICI) 2021-2027 for climate, migration

and human development show that climate change

resilience among the most vulnerable populations

is a priority for the Commission. As such, the

Instrument provides a framework for DG ECHO

and the development services of the Commission

(namely DG INTPA and DG NEAR) to work in a

complementary manner in the areas of disaster

preparedness and risk reduction.

In line with this approach, DG ECHO will:

• Encourage and support dialogue, information exchange and coordination

between humanitarian, development and peace actors at headquarters and

country levels;

• Support the development and use of a common analysis framework covering

context, needs and risk analysis and, where possible, support joint assessments

and joint planning, in a manner compatible with humanitarian principles;

• Support a multi-year NDICI planning and programming cycle to counter the

multi-year funding gaps that have been faced in the past;

• Support the development of key complementary preparedness interventions

that underpin this approach, notably early warning and early action measures;

• Promote further complementary action in Disaster Risk Finance (DRF)

28

,

ensuring that it meets the needs of affected communities and engagement

of civil society organisations (CSO)

29

. Particularly, DG ECHO will explore and

support collaboration to leverage the financing of social protection mechanisms,

where they exist (see also section 6.5 on Shock Responsive Social Protection)

and Forecast-based Financing (see also section 6.1 on Early Warning Systems

and 6.2 on Anticipatory Action as examples of collaboration areas). DG ECHO

is also currently assessing its organisational readiness regarding risk-transfer

instruments, such as financial insurance/micro-insurance, to create and finance

insurance schemes to complement development-funded insurance solutions, as

an additional mechanism for mitigating the impact of shocks at household level;

28. Disaster Risk Finance (DRF) includes “financial protection strategies that increase the ability of national and local governments,

homeowners, businesses, agricultural producers, and low income populations to respond more quickly and resiliently to disasters”

(aer World Bank). It helps minimise the cost and optimise the timing of meeting post-disaster funding needs without compromising

development goals, fiscal stability, or wellbeing. DRF promotes comprehensive financial protection strategies and market-based

disaster risk financing and insurance solutions (such as sovereign catastrophe risk transfer solutions for governments or domestic

catastrophe risk insurance for public and private assets) to ensure that governments, homeowners, small and medium-sized

enterprises, agricultural producers, and people in the most vulnerable situations (especially youth and women) can meet post-

disaster funding needs as they arrive.

29. For more on DRF tools and the engagement of civil society organisations: Ensuring impact: the role of civil society organisations

in strengthening World Bank disaster risk financing (UK Aid, Mercy Corps, Oxfam - 2019).

As part of a disaster

preparedness project

that aims to increase the

resilience of Mongolian

herders, the EU’s

partner, People in Need

(PIN), created an SMS

service that provides the

herders with weather

forecasts and data on

pasture degradation.

This allows them to take

precautionary measures

and manage their herds

more effectively when

there is a harsh winter

(known as ‘dzud’).

© 2018 European Union /

Pierre Prakash

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

24

• Encourage initiatives to leverage funding across the humanitarian, development

and peace boundaries to invest in national capacities and systems to enhance

first responders’ ability to operate across the nexus divides, while building self-

reliance and reducing their dependence on external intervention.

Embedding DG ECHO-funded humanitarian projects in a nexus approach ensures that

the hand-over to our development partners is more fluid. This can only benefit the

sustainability of these projects and help to guarantee that exit strategies are successful.

5.2 Partnerships

In addition to strong partnerships with humanitarian actors, DG ECHO seeks to develop

synergies and complementarity through new partnerships, fostering a coordinated

approach where needed, while allowing space for creative and critical dialogue in

relation to policy development and implementation. DG ECHO brings the following

assets to this process:

• Its convening power as one of the world’s largest humanitarian donors;

• Its role as a reference donor and advocate;

• Its support for learning and the development of policy and good practice.

DG ECHO will engage with a broad spectrum of key actors and stakeholders

30

, such as:

• Other donors, both those that are like-minded and those with different

perspectives;

• Non humanitarian multi-lateral organisations, including the relevant UN

agencies and the World Bank;

• Climate and environmental experts/organisations;

• Organisations working with indigenous people;

• Academic, scientific, research and policy development institutes;

• Private sector bodies, particularly those involved in risk management;

• Security and military actors, in line with international humanitarian civil military

coordination guidelines and recommended practices

31

.

DG ECHO recognises that there is potential value in cooperation

between the scientific and academic community and the

humanitarian sector in all phases of humanitarian aid, from

disaster preparedness to needs assessment and early recovery.

This type of partnership can be particularly relevant in improving

understanding of current and emerging risks, for example

those related to climate change, as well as in the enhancement

of technical innovation for both preparedness and response

activities.

DG ECHO will increase exchanges with operational and research

partners, to ensure that its policy continues to evolve.

DG ECHO will also increase the timeframe of some of the existing partnerships

through the establishment of Programmatic Partnerships

32

, which address the

30. Development actors within the European Commission (i.e. DG INTPA, NEAR and the EEAS) are not listed here as they are

considered included already as partners in the Nexus approach.

31. www.unocha.org/fr/themes/humanitarian-civil-military-coordination

32. Programmatic partnerships have been piloted with NGO partners since 2019. As of 2021, they will also be piloted with UN

Agencies, IFRC and ICRC.

“

DG ECHO will increase

exchanges with operational

and research partners,

to ensure that its policy

continues to evolve.

DG ECHO Disaster Preparedness Guidance Note

25

Grand Bargain commitments to increase predictability and the provision of multi-

year funding. Programmatic partnerships are a specific operational modality: for

NGO partners under the DG ECHO Humanitarian Certification; for UN agencies

under the Financial and Administrative Framework Agreement - FAFA; for the

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) under their respective Framework

Partnership Agreement

33

.

Furthermore, coordination with security and military actors will take place in

accordance with humanitarian principles. Coordination of this kind can be particularly

useful in humanitarian emergency and disaster situations which require capabilities

that are only available from the military community, and that civilian bodies can

request as a last resort. In this regard, DG ECHO will continue to promote and