2013

Training our

future teachers:

Revised January 2014

AUTHORS:

Julie Greenberg, Hannah Putman and Kate Walsh

OUR THANKS TO:

Research analysts: Laura Pomerance, with assistance from Katherine Abib

Graduate fellow: Natalie Dugan

Database design, graphic design and technical support: EFA Solutions

FUNDING FROM:

Carnegie Corporation of New York - Gleason Family Foundation - Laura and John Arnold Foundation - Michael & Susan Dell Foundation - Searle

Freedom Trust - The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation - The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation - B&L Foundation - The Rodel Charitable

Foundation of Arizona - Arthur & Toni Rembe Rock - Chamberlin Family Foundation - The Anschutz Foundation - Donnell-Kay Foundation - Rodel

Foundation of Delaware - The Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation - The James M. Cox Foundation - The Zeist Foundation, Inc. - J.A. and Kathryn

Albertson Foundation - Finnegan Family Foundation - Lloyd A. Fry Foundation - Osa Foundation - Polk Bros Foundation - Ewing Marion Kauffman

Foundation - The Aaron Straus and Lillie Straus Foundation - The Abell Foundation - Morton K. and Jane Blaustein Foundation - Barr Foundation

- Irene E. and George A. Davis Foundation - Longeld Family Foundation - Sidney A. Swensrud Foundation - The Boston Foundation - The Harold

Whitworth Pierce Charitable Trust - The Lynch Foundation - Treer Foundation - MinnCAN: Minnesota Campaign for Achievement Now - Foundation

For The Mid South - Phil Hardin Foundation - The Bower Foundation - Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation - The Bodman Foundation - William E.

Simon Foundation - George Kaiser Family Foundation - Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation - The Heinz Endowments - Benwood

Foundation - Hyde Family Foundations - Houston Endowment - Sid W. Richardson Foundation - The Longwood Foundation - Cleveland Foundation

- Walker Foundation

WE ARE GRATEFUL FOR:

The comments from two members of NCTQ’s Teacher Advisory Group: Freeda Pirillis and Sheryl Place

The helpful critiques from: Robert Pianta, James Cibulka, Jane Close Conoley, Barry Kaufman, Thomas Lasley,

Douglas Lemov and Robert Presbie

NCTQ BOARD OF DIRECTORS:

John L. Winn, Chair, Stacey Boyd, Chester E. Finn, Jr., Ira Fishman, Marti Watson Garlett, Henry L. Johnson,

Thomas Lasley, Clara M. Lovett, F. Mike Miles, Barbara O’Brien, Carol G. Peck, Vice Chair, and Kate Walsh,

President

NCTQ ADVISORY BOARD:

Sir Michael Barber, McKinley Broome, Cynthia G. Brown, David Chard, Andrew Chen, Celine Coggins, Pattie Davis,

Michael Feinberg, Elie Gaines, Michael Goldstein, Eric A. Hanushek, Joseph A. Hawkins, Frederick M. Hess, E.D.

Hirsch, Michael Johnston, Barry Kaufman, Joel I. Klein, Wendy Kopp, James Larson, Amy Jo Leonard, Robert H.

Pasternack, Michael Podgursky, Stefanie Sanford, and Suzanne Wilson

Note:

This January 2014 version of the report includes minor revisions of the original December 2013 version. The only

substantive revisions stem from changes to the analysis of four programs (of 122): these programs are now credited

with attention to all of the Big Five on the basis of their instruction on the Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports

model. Relevant gures and text have been updated as necessary to reect this new analysis.

i

Executive Summary

Executive summary

Every teacher wrestles with the challenge of keeping two or three dozen students

in a classroom engaged. While better instruction generally results in better

behaved students, the most brilliantly crafted lesson can fall on deaf ears

— or, worse, be upended by disruptive behavior. A strong, veteran teacher

may only occasionally have difculty handling disengaged or poorly behaved

students, but for new teachers, the strain of trying to deliver sufciently engaging

instruction and at the same time orchestrate appropriate behavior can be intense,

overwhelming and ultimately defeating.

In this new report from the National Council on Teacher Quality, we investigate

the extent to which America’s traditional teacher preparation programs offer

research-based strategies to their teacher candidates to help them better

manage their classrooms from the start.

The wisdom accumulated from centuries of teaching — as well as ndings

from strong, recent research studies — recognizes that student learning depends

on both engaging instruction and a well-managed classroom.

What is behind a well-managed classroom? First, it is critical that teachers

plan and implement daily routines before any misbehavior has a chance to

erupt, and second, teachers should establish the right kinds of interactions

with students (e.g., praising good behavior rather than drawing attention to

bad behavior with criticism) to consistently maintain a focus on instruction.

Considerable research exists on classroom management, much of it consolidated

into three authoritative summaries of 150 studies conducted over the last six

decades. These studies’ agreement that some classroom management strategies

are more likely to be effective than others helped us isolate the ve most important

strategies on which to train teacher candidates:

1. Rules: Establish and teach classroom rules to communicate

expectations for behavior.

2. Routines: Build structure and establish routines to help

guide students in a wide variety of situations.

New teachers

deserve better.

It is time for teacher

prep programs to

focus on classroom

management so that

rst-year teachers

are prepared on

day one to head off

potential disruption

before it starts.

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

ii

www.nctq.org/teacherPrep

3. Praise: Reinforce positive behavior using praise and other means.

4. Misbehavior: Consistently impose consequences for misbehavior.

5. Engagement: Foster and maintain student engagement by teaching interesting lessons

that include opportunities for active student participation.

These strategies are so strongly supported by research that we refer to them here as the “Big Five.” They serve as

the yardstick for this study, measuring the extent to which teacher preparation programs are training teachers in

research-based classroom management strategies. We also examine the integration of a handful of other strategies,

although their research bases are not quite as strong.

Everywhere but nowhere

By examining a sample of 122 teacher preparation programs in which we were able to review the full breadth of the

professional sequence — including lecture schedules, teacher candidate assignments, practice opportunities, instruments

used to observe and provide feedback on teaching episodes, and textbooks — we can conclude the following:

n Most programs can correctly claim to cover classroom management, with only a tiny fraction (<3 percent) in our

sample ignoring instruction altogether. However, instruction and practice on classroom management strategies

are often scattered throughout the curriculum, rarely receiving the connected and concentrated focus they deserve.

n Most teacher preparation programs do not draw from research when deciding which classroom management

strategies are most likely to be effective and therefore taught and practiced. Especially out of favor seem to

be strategies that impose consistent consequences for misbehavior, foster student engagement, and — most

markedly — use praise and other means to reinforce positive behavior. Half of all programs ask candidates to

develop their own “personal philosophy of classroom management,” as if this were a matter of personal preference.

n Instruction is generally divorced from practice (and vice versa) in most programs, with little evidence that what

gets taught gets practiced. Only one-third of programs require the practice of classroom management skills as

they are learned. This disconnect extends to the student teaching experience.

n Contrary to the claims of some teacher educators, effective training in classroom management cannot be

embedded throughout teacher preparation programs. Our intensive analysis of programs in which classroom

management is addressed in multiple courses reveals far too great a degree of incoherence in what teacher

candidates learn and what they are expected to do in PK-12 classroom settings. Embedding training everywhere

is a recipe for having effective training nowhere.

The false promise of instructional virtuosity

There is little consensus in the eld regarding what aspects of classroom management should be taught or practiced.

The closest the eld comes to an endorsed approach is the apparent conviction that teachers should be able to rise to

a level of instructional virtuosity that eliminates the need for dened strategies to manage a classroom. Defending the

lack of focused classroom management training in many teacher preparation programs, the eld’s intellectual leader,

Linda Darling-Hammond, argues that the teacher candidate should instead learn to “manage many kinds of learning

iii

Executive Summary

and teaching, through effective means of organizing and presenting information, managing discussions, organizing

cooperative learning strategies, and supporting individual and group inquiry.”

Another discouraging development concerns the edTPA, a performance assessment intended as a gateway for licensure,

which is now being rolled out in half the states with the strong endorsement of the eld’s leadership. Although in many

ways the edTPA is a commendable effort to insert greater rigor and accountability into teacher preparation, it has

yet to specify explicitly what teacher candidates ought to demonstrate as classroom managers. Given how important

the edTPA has already become, it is crucial that evaluation of teacher candidates’ classroom management skills be

incorporated more explicitly into the edTPA’s rubrics.

The silver lining is that, according to one survey, half of teacher educators aren’t entirely sure that the approach —

actually more of a non-approach — of relying solely on instructional virtuosity for classroom management works. It is

also clear that some programs are paying more attention to research and to the alignment of instruction and practice:

St. Mary’s College of Maryland, the University of Virginia and the University of Washington – Seattle are

notable for aligning instruction and practice with research-based strategies.

Other than calling out programs that do well on a particular aspect of classroom management training, this report

does not provide overall ratings on individual programs. Further, we could not identify a single program in the sample

that did well addressing all research-based strategies, identifying classroom management as a priority, strategically

determining how it should be taught and practiced, and employing feedback accordingly. Teacher preparation’s

misdirection in the area of classroom management — insisting that instructional excellence alone can maintain the order

necessary for learning — appears almost universally accepted by the eld’s leadership, and therefore this report

necessarily reaches conclusions that require attention by the eld as a whole.

Solutions

States

Unfortunately, we hold out little hope for a regulatory solution to this issue. While the regulations of every state at least

briey mention training in classroom management, most regulations are poorly informed by the research. Regulators

and legislators can and should use their inuence to make clear to programs their belief that training new teachers in

classroom management strategies is crucial. Unfortunately, policymakers may lack the tools to ensure that preparation

programs are actually training their candidates in these strategies.

Programs

It is up to programs to prepare their candidates in research-based classroom management strategies, beginning with

the rst foundational courses and continuing to their culminating experience as student teachers. Such integrated

preparation runs counter to current practice in higher education, where individual faculty members are too often permitted

to decide what to teach, with insufcient regard for programmatic goals. Instruction is needed that connects the dots,

with seamless transitions between content delivery and practice.

Because of largely avoidable instances of student misbehavior, the rst year of teaching can be a harrowing experience.

New teachers and our children deserve better from America’s teacher preparation programs, and training that is

carefully designed to prepare teacher candidates to be both effective instructors and effective classroom managers

will help make the rst year a happier and more rewarding experience for both teachers and their students.

v

Table of Contents

Preface page vii

1. Introduction 1

2. What the research about classroom management says 3

3. How this study was conducted 7

4. Findings 11

5. Programs that rise to the top 29

6. Recommendations 31

7. Conclusion 37

Appendices

(available separately online at http://www.nctq.org/dmsStage/Future_Teachers_Classroom_Management_NCTQ_Report)

Appendix A: Teacher preparation programs included in this study

Appendix B: Methodology

Appendix C: Inventory of research on classroom management

in PK-12 classrooms

Appendix D: Crosswalk of classroom management models and the Big Five

Appendix E: Cross-program analyses

Appendix F: How NCTQ develops standards for the Teacher Prep Review

Appendix G: Sample demographics

vii

Preface

The purpose of this report is to investigate the extent to which traditional teacher preparation programs — where

most new teachers get their training — deliver content and provide teacher candidates with opportunities to practice

on a body of knowledge about classroom management. The examination complements rather than mirrors the analysis

of classroom management conducted in the 2013 edition of NCTQ’s Teacher Prep Review, which will be repeated

in the 2014 edition. Here we primarily address the classroom management instruction and practice that teacher

candidates receive before student teaching, while the Teacher Prep Review addresses the feedback on classroom

management skills that teacher candidates receive during student teaching.

We originally intended this study to serve as a pilot for an enhanced classroom management standard to be applied

in the Review. (See Appendix F for our approach to developing standards.) A new standard would have considered

coursework and clinical practice, as well as the feedback provided to student teachers. Unfortunately, that standard

is not feasible as long as so many teacher preparation programs decline to participate in the Teacher Prep Review

evaluation process. Absent their participation, it is simply too challenging to collect from the 1,100-plus institutions

rated in the Review full sets of syllabi and other materials for all professional coursework.

As an added complication, there are a multitude of textbooks used to teach classroom management (more than 140

different textbooks in the small sample for this study). This overabundance of textbooks has precluded the textbook

reviews that would be valuable additions to any discussion about what teachers should learn about classroom management

before going into the classroom.

We are grateful to the institutions that provided the full sets of materials that made this study possible.

1

Introduction

Nearly every one of the

122 teacher preparation

programs included in this

study provides some kind

of instruction on classroom

management. It is likely

that the same is true for

the teacher preparation

programs housed in

1,450 institutions

nationwide. And yet,

despite classroom

management’s apparent

pervasiveness in

preparation coursework,

something is not working.

1. Introduction

A paradox exists in our classrooms. While many classroom management problems

are probably symptoms of poor instruction, it is unlikely that improving instruction

is the whole solution, or at least not the solution a teacher needs most immediately.

For that reason, specic attention to classroom management itself is necessary.

Conversely, even if instruction is adequate, it can be complemented, and its

impact enhanced, by good classroom management.

1

There is no question that dynamic instruction and a strong rapport with students

are both desirable in their own right and reduce the need for overt management.

However, the possibility always exists that a teacher will need to act in the

moment — for example, regaining the attention of a student who is losing

focus or handling an unusually chaotic return from recess.

2

Teachers who can

plan and implement daily classroom routines and patterns of interaction that

mitigate misbehavior, and also can address inevitable misbehavior, are able to

teach more effectively. Furthermore, classroom climate is highly predictive of

the teacher stability every school craves, particularly schools serving high-need

populations. Teachers are more likely to stay in schools where they feel

successful, having created functional classrooms with students who are behaving

appropriately and are academically engaged.

3

Some argue — particularly proponents of the nontraditional pathways through

which teacher candidates enter classrooms with little preparation — that classroom

management can only truly be learned through experience. No doubt, experience

helps, but the capacity to achieve a well-managed classroom need not be

developed only through trial and error from years of teaching experience.

Fortunately, there also is a clear body of knowledge that, if taught and practiced,

could help lessen the steepness of the new teacher’s learning curve. This

knowledge speaks to the most effective approaches to classroom organization and

techniques for interaction with students, developed over centuries of teaching

and conrmed by research conducted over the last half century.

Every teacher preparation program should impart this knowledge to the next

generation of teachers, developing as much competence in teacher candidates

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

2

www.nctq.org/teacherPrep

In a 2013

survey, classroom

management was

“the top problem”

identied by

teachers.

as possible through instruction and practice. Doing so will create a virtuous cycle

from day one in which a novice teacher’s functional classroom environment

helps to build relationships with students that, in turn, produce even more

functional and productive teaching and learning.

Nearly every one of the 122 teacher preparation programs included in this

study provides some kind of instruction on classroom management. It is likely

that the same is true for the teacher preparation programs housed in 1,450

institutions nationwide. And yet, despite classroom management’s apparent

pervasiveness in preparation coursework,

4

something is not working. Classroom

management continues to be one of the greatest challenges new teachers

face. Surveys repeatedly document that novice teachers struggle in this area,

and their school district supervisors concur.

5

n A 1997 poll revealed that 58 percent of PK-12 teachers said that behavior

that disrupted instruction occurred “most of the time or fairly often.”

6

n A 2003 survey of teachers found that nearly half indicated that “quite a

large number” of new teachers need a lot more training on effective ways

to handle students who are discipline problems.

7

n In 2012, over 40 percent of surveyed new teachers reported feeling either

“not at all prepared” or “only somewhat prepared” to handle a range of

classroom management or discipline situations.

8

n In a 2013 survey, classroom management was “the top problem” identied

by teachers.

9

In this report, we delve deeper into the practices of actual programs to better

understand the specics of preparation in classroom management. Our ndings

will shed light on why too many new teachers, by their own account or that of

their supervisors, are entering schools ill-equipped to move beyond behavioral

challenges and into the heart of instruction.

3

What the research about classroom management says

2. What the research about

classroom management says

Considerable research exists on classroom management, much of it consolidated into three authoritative summaries

relevant to the PK-12 grade span: a 2008 summary by Simonsen, Fairbanks, Briesch, Myers, and Sugai; a 2011 summary

by Oliver, Wehby, and Reschly; and another summary published in 2008 by the Institute of Education Sciences, Reducing

Behavior Problems in the Elementary School Classroom. (See Appendix C for our analysis of this research.) Together

these summaries examine over 150 studies conducted over six decades.

Despite the wide variation in research citations in these sources, there is congruence in their ndings on essentially

ve strategies for classroom management. These ve carry signicant evidence of their effectiveness. For that reason

we label them the “Big Five.”

THE BIG FIVE

Research-based classroom management strategies that every teacher candidate should learn and practice:

1. RULES

Teachers (or teachers and students collaboratively) should develop a limited set of positively stated expectations for

behavior. These expectations should not simply be posted in the classroom; rather, they should be explicitly taught

by discussion and practice and applied transparently and equitably.

2. ROUTINES

Teachers should teach routines and procedures, including specic guidelines for how to act in a variety of situations

(e.g., arriving in the classroom, handing in homework, working in groups). These routines should be taught at the beginning

of the school year and then revisited periodically throughout the year. In turn, teachers should sustain momentum for

instruction by orchestrating the management of time and materials by themselves and students, especially in transitions

between activities.

3. PRAISE

Teachers should reinforce positive behavior using praise and other rewards. Intangible rewards such as praise

10

should be specic (e.g., “Good job nding your seat quickly,” “Great work sharing your crayons,” “John, Neery, and

Dominic all have their homework ready to turn in — well done”) and abundant.

11

Rewards also may be tangible (e.g., a

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

4

www.nctq.org/teacherPrep

No one can

learn when the

learning environment

is not under control,

whatever that looks

like for each grade

and age.

– 3rd grade teacher

Respondent to

NCTQ survey

prize like a sticker or pencil, or a privilege like extra free time). Rewards can be

used for individual or group behavior and may be phased out over time as students’

behavior improves by habit.

12

(See the textbox below for more on praise.)

4. MISBEHAVIOR

Just as every parent learns that children will not always follow rules and has in

mind consequences for noncompliance, so, too, do teachers need to determine

the appropriate consequences for misbehavior and apply these consequences

consistently. Consequences generally follow different levels of severity, escalating

to one-on-one conferences with the teacher, detentions, meetings with parents

or guardians, and so on.

5. ENGAGEMENT

This technique is closely linked to the quality of instruction. Teachers should

constantly engage students in the lesson, whether through creating an interesting

lesson that holds students’ attention or through building in frequent opportunities

for student participation. Students who are involved in the lesson generally

have less inclination to act out.

Praise can be used effectively and appropriately

Perhaps because using praise effectively is more complicated

than simply telling a student “Good job!,” it is frequently neglected

in teacher preparation.

13

Researchers have identied the Do’s and

Don’ts of successful use of praise and positive reinforcement:

Do…

n …be specic about the behavior you are praising.

14

n …make praise contingent on the student actually doing the

target behavior.

15

n …be sincere in the way you praise a student.

16

n …give praise immediately following the appropriate behavior.

17

n …consider the individual student’s characteristics, such as age.

18

n …give praise frequently as a student acquires a behavior

and taper off with students’ mastery.

19

n …praise the process or action.

20

Don’t…

n …praise the person or trait (e.g., “Jill is such a good girl”).

21

n …use reinforcers for a task that students already want to do

absent a performance target.

22

n …ignore the student’s individual response to praise.

23

5

What the research about classroom management says

Secondary strategies

In addition to the Big Five, there are other strategies that do not enjoy the same level of research consensus but still

have a place in any preparation program. For that reason, they should be viewed as valuable topics to address in

teacher preparation after the Big Five:

n Manage the physical classroom environment: This technique refers to thinking strategically when setting up

the classroom; for example, ensuring that the teacher can see all students at all times, considering the ow of

trafc for different classroom activities, and considering how to group desks to maximize student engagement.

n Motivate students: This topic is distinct from engagement in that it focuses on whether students want to learn

or follow the rules. While some people distinguish between internal and external motivation, and fear that a

focus on rewards for good behavior may reduce students’ intrinsic motivation to behave, research evidence is

reassuring that this need not occur.

24

n Use the least intrusive means: This topic refers to using subtle techniques to prevent or quickly halt budding

misbehavior. These techniques include using proximity, giving a rule reminder, giving a “teacher look,” or asking

off-task students substantive questions to redirect attention back to the lesson.

n Involve parents and the school community: Involvement can mean making phone calls home, meeting with

parents or taking other actions that engage stakeholders beyond the classroom.

n Attend to social/cultural/emotional factors that affect the classroom’s social climate: This interaction

technique focuses on maintaining a positive affect in the classroom and being culturally sensitive.

The importance of relationships

Virtually all teachers with whom we have discussed this report, including the experienced teachers who advise

NCTQ (http://www.nctq.org/about/teacherAdvisoryGroup.jsp), believe that building relationships with students

is just as essential for a functional, productive classroom as anything mentioned above, and that these relationships

can preclude the need for heavy-handed classroom management. We agree. Research indicates that effective

teacher-student relationships are not established by teachers taking on a “buddy” role. Rather, teachers build

relationships by providing clear purpose and strong guidance—the types of purpose and guidance that are

conveyed by fair rules and productive routines, as well as by clear learning goals and expectations.

25

7

How this study was conducted

Examples of lecture topics:

n Managing the Classroom

Environment

n Discipline and Consequences

n Establishing Rules and

Procedures

n Schedule of Reinforcement

n Routines and Procedures

Examples of common

pencil-and-paper assignments:

n Write a set of rules for

a classroom

n Write a personal philosophy

of classroom management

Examples of common

practice assignments:

n Videotape yourself teaching

a lesson and present the video

in class for discussion

n Teach a lesson and receive

feedback from a cooperating

teacher

3. How this study was conducted

The methodology is explained in more detail in Appendix B. See the

textbox on page 10 for a primer on the nature of instructional and

clinical coursework in teacher preparation.

The study examines the degree to which 122 teacher preparation

programs teach and provide opportunities to practice research-based

classroom management strategies and techniques. (See Appendix A

for a list of programs and Appendix G for sample demographics.)

These programs are housed in 79 institutions across 33 states, and

include most types of programs (undergraduate and graduate, elementary

and secondary). All programs were willing (sometimes voluntarily, but

generally by means of open records requests) to provide NCTQ with

full sets of materials for their professional coursework, making this

analysis possible.

Preparation in classroom management in both instructional and clinical

coursework should theoretically be seamless, meaning that skills

build upon each other and follow a natural progression. Ideally teacher

candidates learn about and practice these skills in foundational

coursework, practice in more challenging situations (e.g., real classrooms)

in clinical coursework, and receive detailed and critical feedback in

a full-scale teaching situation in student teaching. This principle of

seamlessness underlies the three kinds of analyses undertaken for

this study.

For the rst, broadest analysis, we identied 213 courses in our sample

that could conceivably address classroom management. Our analysis

included: 1) instructional coursework where content is delivered

(and in which there is often eldwork in PK-12 classrooms), and 2)

practica closely aligned with classroom management-focused

instructional coursework. These categories of coursework are referred

to in the report as “foundational coursework.”

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

8

www.nctq.org/teacherPrep

For all foundational courses, we examined the syllabus, pulling out lecture topics, student assignments, and required

textbooks. Each lecture topic, student assignment, and textbook was then coded to distinguish which were relevant

to classroom management and what precisely was being addressed.

Example of coding a lecture description from a syllabus

For more examples of how lectures and assignments were coded, see Appendix B: Methodology

Sample lecture schedule from course entitled “Classroom Management”

Aaren tic:

• Rne an rcv aegie;

• Tm an aerial anagemen;

• Oganiza clar

Ce: B v aeg: Rne;

cdar aeg: Physica envirmen

Aaren tic:

• Respdin disrupv behavi;

• Respdin inimal disrupv behavi

Ce: B v aeg: Misbehavi;

cdar aeg: Leas nusiv ean

II. COURSE OUTLINE AND SCHEDULE. Tentative schedule

Meeting 4 Review/Application Activity

Discuss Unit C Part I — Typed Discussion Questions due!

Discuss Video Self Assessment of Teaching

Assignment: Read Unit C Part II (pgs. 116-145)

Space, Time, and Routines

Causes of Disruptive or Inattentive Behavior

Group work on presentations

Through this analysis we were able to discern how much time programs are dedicating to classroom management and

which topics they are addressing, including which of the Big Five (and secondary topics as well) are being addressed, if

they are addressed at all.

In the event that two different interpretations of lectures or assignments were possible, we used context clues from other

parts of the syllabus or applied the most generous interpretation. For example, a reference to a lecture on “intervention

strategies” might refer to instruction on responding to either or both off-task behavior using least intrusive means or

disruptive behavior using consequences for misbehavior. If context clues did not help us discern which, we credited the

lecture to coverage of both relevant strategies. Or, for example, it was sometimes necessary to discern if a course is

teaching “student engagement,” one of the Big Five, as a means to a well-managed classroom, or if it is teaching that

student engagement is a feature of a well-constructed lesson. When it was not possible to discern the difference, credit

was given for covering it as a management strategy. In cases in which topics could not be discerned, the syllabus was

removed from the analysis.

In a second, more focused analysis of 25 programs, we looked for classroom management instruction and practice in

general clinical coursework designed to provide PK-12 classroom experiences that touch on a variety of professional

skills. The purpose of this analysis was to determine the extent to which such coursework provides additional classroom

management content and practice opportunities beyond the foundational courses treated in our rst, broader analysis.

9

How this study was conducted

Lastly, in the third analysis, we conducted intensive “cross-program” analyses that traced preparation from start to

nish for a sample of nine programs, effectively case studies. This analysis determines the level of coherence in training

in all classroom management strategies, beginning with foundational coursework, running through clinical coursework,

and culminating with the feedback on the execution of classroom management strategies in student teaching. It provides

a comprehensive portrait of what teacher candidates typically experience in the way of training in this area and provides

a clear sense of whether embedding such training is adequate.

Fig. 1 How we sampled coursework in three different analyses

Analysis 1:

Foundational coursework

Analysis 2:

General clinical coursework

Analysis 3:

All coursework (“Cross-program”)

What is it?

Instructional courses and closely

aligned practica that explicitly

address classroom management

in whole or in part.

General clinical coursework

that does not explicitly address

classroom management, but

is designed to provide PK-12

classroom experiences on a range

of professional skills that may

or may not include classroom

management.*

Foundational, general clinical

experience, and student teaching

courses (for observation/

evaluation instruments).

What was

evaluated?

Examples of foundational courses:

n Classroom Organization

and Management

n Curriculum and Methods

of Teaching in Elementary

Education

Examples of general clinical

coursework:

n September Experience

in the Schools

n Elementary Education

Capstone Seminar

n Elementary Methods

Practicum III

Sequence of relevant courses from

a graduate elementary program:

n Field Experience –

Elementary Education

n Instruction and Assessment

n Teaching Associateship –

Elementary Education

n Student Teaching Evaluation

Instrument

What did we

look for?

Instruction and practice in 213

courses in the 119 programs

(of 122) that have foundational

coursework.

Instruction and practice in

43 courses in 25 programs

randomly selected from the

full 122-program sample.

Instruction, practice and feedback

in all courses in nine programs

selected in a stratied random

sample from the full 122-program

sample.

Why did we

look here?

To determine if programs lay a

foundation for teacher candidates

to understand and use classroom

management strategies.

To determine the extent to which

this increasingly common type

of clinical experience adds to

teacher candidate understanding

and capacity to use classroom

management strategies.

To provide a deeper dive

that shows if what’s taught in

coursework relates to what’s

evaluated in student teaching.

(These cross-program analyses

complement a 93-program statistical

analysis that provided information

on coherence.)

* Student teaching seminars were included. In keeping with the rationale for including subject-specic secondary practica in Analysis 1

(see Appendix B), subject-specic clinical experiences were included in Analysis 2.

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

10

www.nctq.org/teacherPrep

In my undergraduate

studies, it was all about

developing a classroom

management philosophy,

but nothing about the

practical routines and rules

that work in the classroom

and that are backed

by research. I had to

research and learn these

on my own.

– 17- year veteran

Respondent to

NCTQ survey

A primer on instructional and clinical coursework in

teacher preparation

While classroom management may be a difcult topic to teach

because it is hard to substitute for sustained whole-class

experiences, and opportunities for those are scarce, traditional

teacher preparation seems relatively well congured for the task.

Traditionally, the rst part of a teacher candidate’s preparation

is “instructional” coursework, with light doses of eldwork in

PK-12 classes. The second part is “clinical coursework,” with a

gradual and increasing infusion of PK-12 classroom experiences

that culminate in a semester-long placement in a PK-12 classroom

generally called “student teaching.”

Instructional coursework for the most part takes place on the

college campus. With the exception of some hours of associated

eldwork in PK-12 classrooms, this coursework is generally

analogous to the coursework taken by other undergraduate or

graduate students on a campus. Especially on larger campuses,

most instructional courses are taught by academically specialized

faculty with advanced degrees. However, former practitioners

hired as adjunct faculty can also serve as instructors.

Clinical coursework

26

encompasses a broad range of

coursework for which programs often take very different

approaches. Clinical coursework is largely or entirely based

in PK-12 classrooms. To varying degrees, clinical coursework

entails some class meetings. These, in turn, have varying degrees

of similarity to class meetings in instructional courses in terms

of expectations for organized instruction and assignments,

both for the instructors and for teacher candidates.

In most cases, the individuals who oversee teacher candidates

in clinical coursework are contract employees (often former

teachers or school administrators) whom we refer to as “university

supervisors.” These university supervisors may also serve as

instructors who convene class meetings associated with clinical

coursework.

The teachers in whose classrooms clinical coursework takes place

go by many titles, but we refer to them as “cooperating teachers.”

Programs vary on how much they depend on cooperating

teachers for the formal observation and evaluation of teacher

candidates in their clinical coursework.

11

4. Findings

To answer the basic question, “Are teacher candidates provided with the knowledge and practice opportunities that

will prepare them to competently manage a classroom from day one?” we turned over a lot of rocks. We did not

predetermine under which rock we had to nd such evidence — in effect deciding for programs in which course or

semester they must teach classroom management — only that there needed to be evidence somewhere that programs

draw upon research-based strategies.

Finding 1: While virtually all programs have coursework that claims

to teach classroom management, many actually give the

subject short shrift.

Programs can correctly claim to cover classroom management, with only a tiny fraction of programs (<3 percent) in

the sample ignoring it altogether.

Our analysis examined 213 courses in 122 programs where classroom management might conceivably be addressed.

In almost all programs it was readily apparent which foundational courses were designed to address classroom

management. The average time in candidates’ coursework spent on classroom management — dened to include anything

having to do with classroom management, whether research-based or not — is the equivalent of eight class periods,

or about 40 percent of a single course (with most programs requiring somewhere between 10 and 15 courses prior to

student teaching).

27

This amount holds true regardless of type of program (elementary or secondary, undergraduate or

graduate), although elementary programs spend slightly more time on classroom management than do secondary programs.

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

12

www.nctq.org/teacherPrep

1. Rules:

Establish and teach

rules.

2. Routines:

Build structure and

establish routine within

the classroom.

3. Praise:

Reinforce positive

behavior using praise

and other means.

4. Misbehavior:

Address misbehavior.

5. Engagement:

Foster and maintain

student engagement.

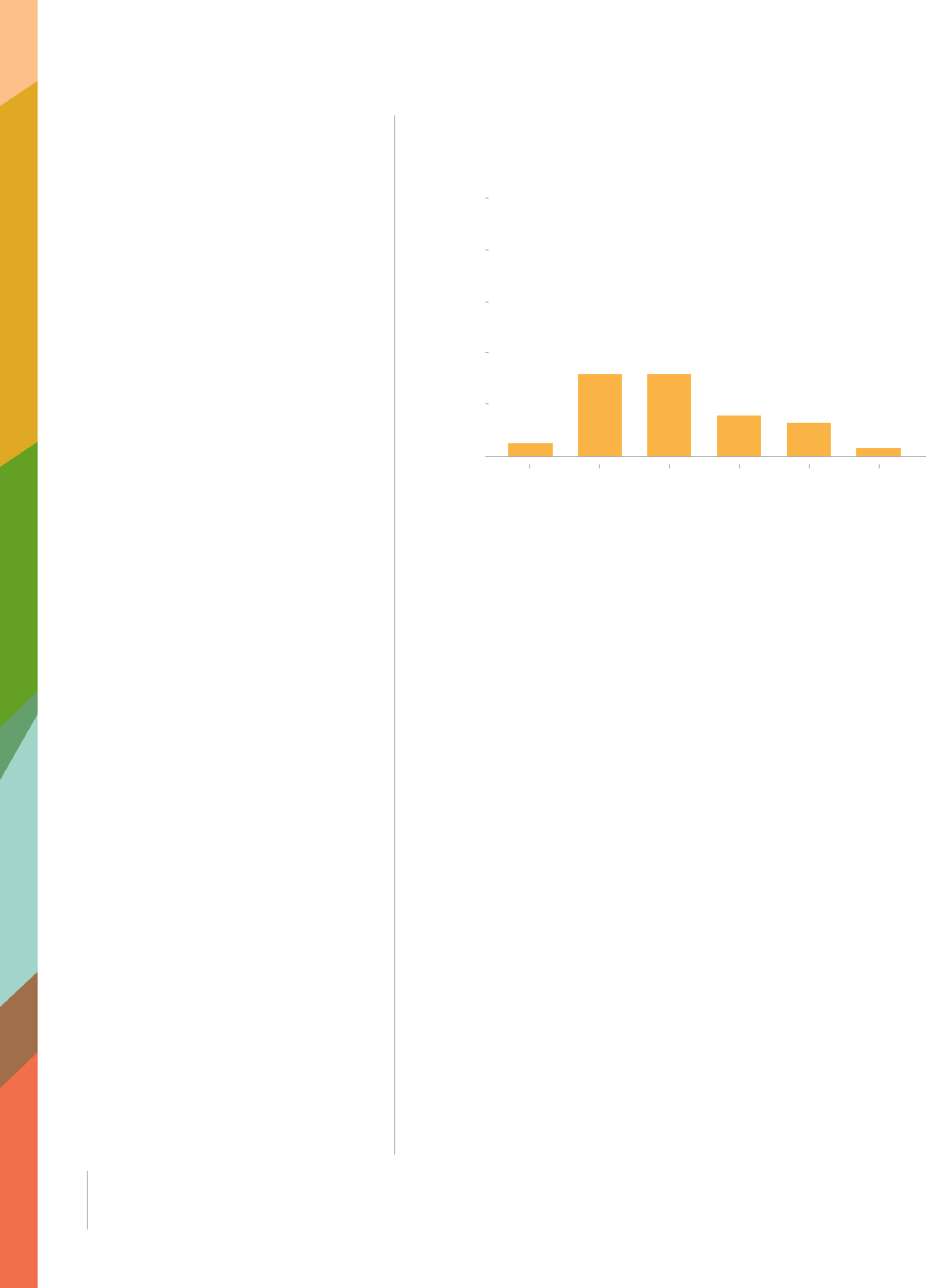

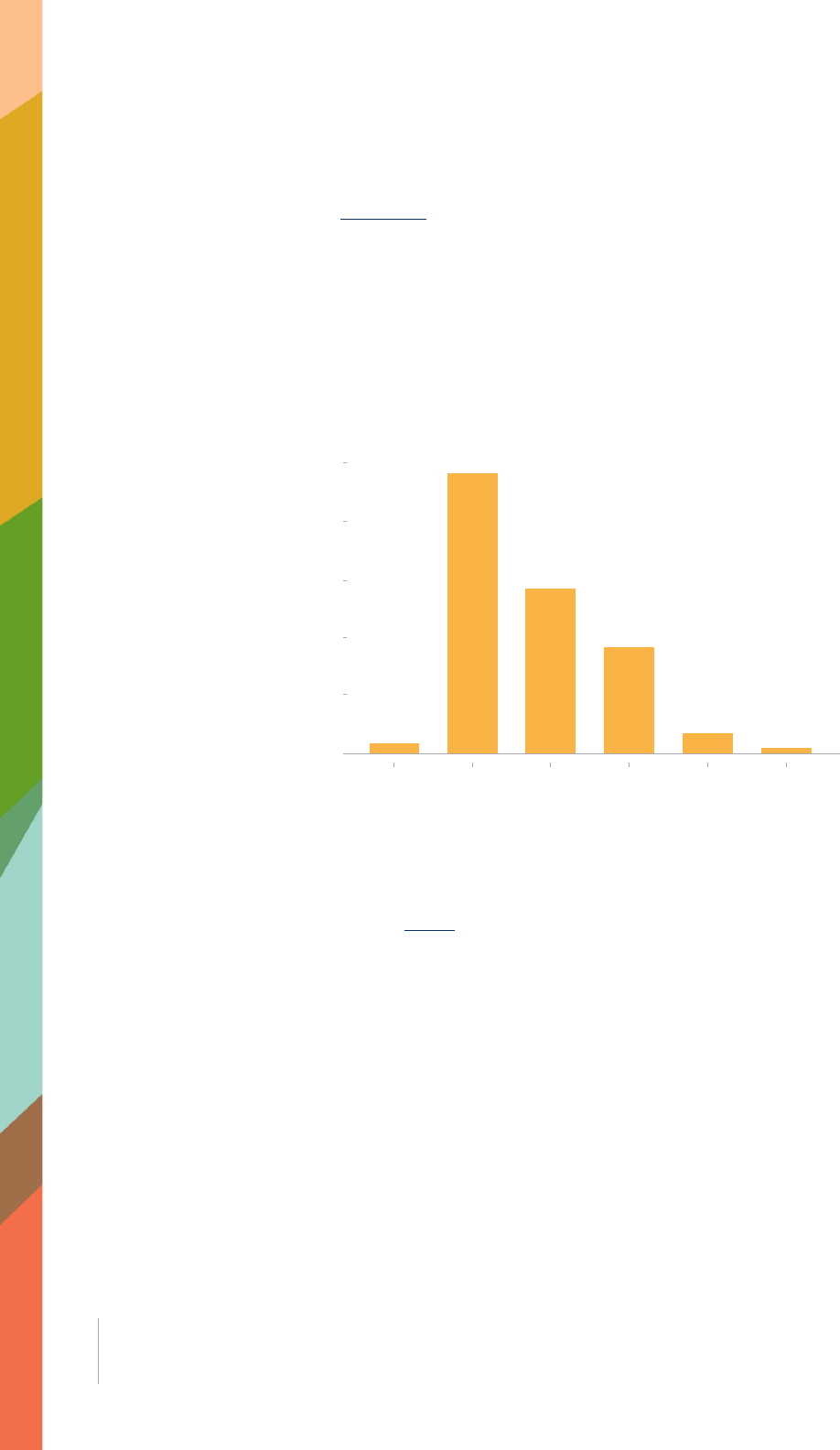

Fig. 2 What proportion of a course do teacher prep programs

devote to instruction on classroom management?

100

80

60

40

20

0

0% 1-25% 26-50% 51-75% 76-100% 101-125%

Percent of one course spent on classroom management

Percent of all programs

(N=76 programs)

Five percent of programs devote less than a single lecture or class in

foundational coursework to any classroom management strategies or topics,

while 16 percent of programs devote most of a course (76% or more), or

even the equivalent of more than one course.

Note: This analysis is based only on the 73 programs that identify individual

topics in all classroom management-related course schedules, with the

addition of the three programs that do not have any coursework on classroom

management, 62 percent of the 122 programs evaluated for this report.

Finding 2: On average, programs

expose teacher candidates

to roughly half of the

core content on effective

classroom management

techniques and approaches.

Research provides a clear consensus for the ve most effective strategies

teachers should know for managing a classroom. (See p. 3 for full

descriptions.) In our analysis we searched for how many of these

Big Five strategies were addressed in candidates’ coursework.

28

The

mean number hovered between two and three addressed in each

program.

29

Again, as with the rst nding, this pattern holds true

regardless of type of program (elementary or secondary, undergraduate

or graduate).

13

Findings

Fig. 3 How many of the Big Five strategies are addressed by teacher prep programs?

100

80

60

40

20

0

0 1 2 3 4 5

Number of Big Five addressed

Percent of programs

(N=105 programs)

Thirty-four teacher prep programs (32 percent) address at least four of the Big Five classroom management strategies (rules,

routines, praise, misbehavior and engagement) in foundational coursework. Only 22 programs (21 percent) address all ve.

Which of the Big Five are taught?

While three strategies (“rules,” routines” and “misbehavior”) are addressed by more than half of teacher preparation

programs, two are seldom addressed, including “praise,” the strategy that is arguably the most strongly supported

by decades of psychology research.

Fig. 4 Which of the Big Five strategies are addressed by teacher prep programs?

Rules

Routines

Praise

Misbehavior

Engagement

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Percent of programs

(N=105 programs)

38%

do not address

misbehavior

51%

74%

24%

29%

do not address

engagement

do not address

praise

do not address

routines

do not address

rules

While the strategy of “routines” is the most commonly addressed of the Big Five, it is still neglected by foundational coursework

in nearly a quarter of programs. “Praise,” which is supported by strong research, is addressed in only 26 percent of programs.

While our analysis focused primarily on the Big Five, other strategies can play a valuable role in helping teachers

proactively prevent disruptions and maintain a focus on instruction. The most common of the second-tier strategies

taught (see p. 5 for a full listing) is “least intrusive means” (e.g., using proximity or eye contact to prevent misbehavior),

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

14

www.nctq.org/teacherPrep

We note that programs

that are generally doing

a good job covering the

Big Five also are more

likely to teach second-

tier strategies.

taught by 75 programs (71 percent). Next most common is “motivation,”

which 45 programs (43 percent) address.

Programs that are generally doing a good job covering the Big Five

also are more likely to teach these second-tier strategies.

In many cases, teacher candidates are introduced to the topic of

classroom management through class discussion of common behavior

models such as “Assertive Discipline” or “Cooperative Discipline” (not

to be confused with whole school behavior programs). These models

(see Appendix D) generally incorporate a collection of strategies. For

the most part, programs do not rely solely on these models to teach

the research-based strategies, with the exception of “praise.” Of the

programs that address praise (again, a surprisingly small number given

its evidentiary base), a third do not provide any explicit instruction or

assignment apart from discussion of a behavior model in which praise

is integral.

Finding 3: Only a third of programs

require teacher candidates

to practice classroom

management skills as

they learn them.

For this somewhat involved analysis of foundational coursework, we

explored any area that might provide evidence that programs are taking

a systematic, coherent approach to developing classroom management

skills in their candidates. We examined lecture schedules to determine if

a classroom strategy was presented in lectures or applied in assignments

required of teacher candidates. We then turned to any associated eld

work and looked at the full breadth of the practicum designed to align

with coursework, seeking some evidence that what was being taught

was then practiced by teacher candidates, whether through a simula-

tion exercise conducted with fellow teacher candidates (found in only

a few foundational courses) or before real students.

Almost all of the programs in the sample (98 percent) do require

assignments of teacher candidates that are related to classroom

management. (See the textbox on p. 16 for common features of

assignments.) In addition, 87 percent of programs for which practice

opportunities can be discerned provide practice opportunities in PK-12

classrooms. Yet most assignments never move past paper-and-

pencil exercises — such as teacher interviews or note-taking

during observations of teachers — into real practice.

15

Findings

Clearly programs integrating content with practice are the minority. We estimate that likely only a third, but at most 44

percent,

30

have assignments that can reasonably be assumed to involve actual practice of classroom management

skills with feedback. In fact, by the strictest categorization — only counting assignments that explicitly state that they

provide candidates the opportunity to practice with feedback on classroom management — only 12 programs (10

percent) provide such opportunities.

Missed opportunities to learn from cooperating teachers and to self-evaluate

Teacher candidates are often not asked to critically evaluate their own teaching performance. An investigation of

foundational classroom management coursework in 40 randomly selected programs that require candidates to spend

time in PK-12 classrooms revealed that only 11 of them (28 percent) require teacher candidates to self-evaluate. Only

about half of these 11 programs require an in-depth or structured analysis; the others simply ask teacher candidates

to reect on their performance (with one program’s syllabus providing too little detail to analyze).

Similarly, teacher candidates’ observations of master teachers are infrequently targeted to classroom management.

Twenty-three of the forty programs (58 percent) include some observation of teachers. However, only about half of

these 23 programs clearly focus at least one observation on teachers’ classroom management. Others focus only on

instruction, or do not identify the relevant teacher behavior for observation in the syllabus.

While not ubiquitous, opportunities to practice become more prevalent in programs that address the Big Five classroom

management strategies.

Fig. 5 Teacher prep programs offering opportunities for practice in foundational coursework (N=118 programs)

24%

No opportunity for

practice provided

32%

Unlikely to provide practice

10%

Has eldwork,

but assignments unclear

24%

Presumed to

provide practice

10%

Explicitly provides

practice and

feedback

Across 118 programs, only a third (34 percent) can be reasonably assumed to offer teacher candidates an opportunity to practice

their classroom management skills and receive feedback in foundational courses. In the remaining programs, due to the

nature of in-class, eldwork or practica assignments, such practice and feedback is unlikely, or denitely does not occur.

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

16

Fig. 6 Practice in teacher prep programs relative to how many of Big Five are addressed in

foundational coursework

100

80

60

40

20

0

0 1 2 3 4 5

Number of Big Five strategies addressed by a program

Practice

Percent of programs

(N=106 programs)

While only twenty percent of programs that teach none or one of the Big Five classroom management strategies also offer

opportunities to practice in foundational coursework, 52 percent of programs that teach four or ve of the Big Five do so.

Note: The 12 programs with eldwork or practica assignments whose type cannot be determined have been removed from

this calculation.

High-quality paper-and-pencil assignments, which require candidates to demonstrate that they

have absorbed and can apply new knowledge, are rare. Following are three exceptions:

n You will read one case study that presents one or more classroom management issues, locate and review

current research articles from peer-reviewed scientic journals that address the same or similar issues and

possible solutions, and write a paper in which you recommend a course of action. Case studies, a list of

appropriate journals, and specic guidelines will be provided by the instructor.

— Central Washington University undergraduate elementary program

n Teacher candidates write an organizational plan that describes the classroom’s physical environment,

procedures and routines, strategies to respond to misbehavior, and other components of a management

plan and reference course readings.

— University of Virginia graduate secondary program

n During eldwork, this course instructs teacher candidates to observe a class with regard to a specic aspect

of teaching. In the rst structured observation, teacher candidates focus on the classroom environment:

they draw a diagram of the classroom layout, describe what’s posted on the walls, and comment on how the

classroom layout affects instruction, peer interactions, and other elements of the class environment. In the

second structured observation, teacher candidates track students’ on-task and off-task behavior. In the third

structured observation, teacher candidates focus on teacher, tracking both instructional and managerial

behaviors (e.g., using praise and specifying rules).

— University of Virginia graduate elementary program

17

Findings

Most assignments do not build on any content a course may have taught. Here are two

representative examples:

n Students will provide indications of learning through weekly online discussions on Blackboard and/or active

classroom participation on the course content. You will maintain a log which will indicate your thoughts,

reections, critical review, and connections to readings and to experiences from the eld.

n Students will develop (or rene) their philosophy paper on the topics of their beliefs about instructional

strategies/classroom arrangement and classroom management and provide a three to ve page paper.

Finding 4: General clinical coursework delivers neither much

content on classroom management, nor (ironically)

well-focused practice.

Virtually every initiative to improve traditional teacher preparation endorses a greater amount of clinical coursework.

Generally, the impetus to increase clinical coursework is attributed to the uneven quality of instructional coursework and

the perception that it is too theoretical to be useful. However, as important as clinical practice in teacher preparation

is, it appears poorly suited to deliver both consistent foundational content and oversight of practice. The inherent variability

in PK-12 classroom situations in which teacher candidates nd themselves — placed with different classroom teachers

and typically supervised by a variety of contract employees — means that the experiences are difcult to predict and

inconsistent across candidates.

We applied this analysis exclusively to the general clinical coursework (see Fig. 1) at 25 programs. We uncovered

only a few instances where classroom management was explicitly being addressed, that is, using assigned

readings with relevance to classroom management and dedicating at least one class session to a classroom management

topic. One out of six of the programs (17 percent) meets that standard. Only about one-third of programs have specic

classroom management assignments; the most common of these are developing a classroom management plan and

completing an assignment related to the physical organization of the classroom.

Leaving aside student teaching (in which teacher candidates are in a classroom daily for a full semester), each of the

general clinical courses reviewed for this particular analysis places candidates in classrooms for anywhere from 10

to 140 hours. Most of those hours are spent observing teachers. Few courses list any specic requirements

about what candidates are supposed to observe, suggesting only general observations about classroom

management or none at all. For example, “Complete a daily journal entry reecting on the personal impact of the

following: Observations made concerning effective classroom management.” Only one course contains an assignment

with a prompt that requires discussion of specic aspects of observed student or teacher behavior: “What are the

stated and unstated rules of the teachers? How are the rules applied?”

As for practice, virtually all the courses, ranging from clinical experiences that precede student teaching to student

teaching seminars, include some type of small-group or whole-group instruction. This practice teaching presents an

opportunity for candidates to critically examine and analyze their own performance. However, only four of 43 courses

(9 percent) in the general clinical coursework analysis require teacher candidates to do self-evaluations of

their own use of classroom management strategies.

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

18

www.nctq.org/teacherPrep

Bright Spot on smart uses of

clinical experiences

At Great Basin College in Nevada, the

“capstone seminar” accompanying student

teaching requires multiple observations

and reections related to classroom

management, each with a specic goal.

At one point, teacher candidates reect

on a targeted observation of a lead

teacher’s procedures and routines (to

accompany reading the text The First

Days of School). Later, teacher candidates

analyze their own ability to manage their

classroom, using a checklist from a text

entitled Qualities of Effective Teachers.

At another point, teacher candidates

develop ve rules they would use in the

classroom and reect on how they are

managing students’ time effectively. And

there’s considerable practice. Teacher

candidates videotape themselves teaching

and assess themselves on classroom

management-related issues like maintaining

an appropriate pace to instruction to ensure

student engagement.

Teaching episodes also presumably include some feedback from a

cooperating and/or a university supervisor on classroom management,

as well as a range of other skills.

31

However, if feedback is provided

in clinical experiences, it is probably provided using observation/

evaluation instruments similar to those used in student teaching,

and if the analysis conducted on such instruments (see p. 20) is any

guide, the feedback bears little relationship to strategies covered in

foundational coursework.

32

Finding 5: Few programs draw

a straight line between

what is learned about

classroom management

in coursework and

what is evaluated in the

culminating experience

of student teaching.

Student teaching is the component of traditional teacher preparation

that comes closest to the “real thing” — where candidates can take

what they have learned in their program and put that into practice

for extended periods — and is therefore crucially important for the

consolidation of classroom management skills.

Regardless of the extent of the training of supervisors and

cooperating teachers, few of them are intimately involved in

the curriculum of the programs with which they become afliated.

For this reason, the observation/evaluation instruments they use to

provide feedback to teacher candidates represent the best and

perhaps the only opportunity for the program to communicate to all

parties the specic aspects of teacher candidate performance it

considers central, including in the area of classroom management.

33

A coherent program would emphasize the same specic strate-

gies of classroom management in coursework as in observation/

evaluation instruments.

To get a better sense of how well programs connect the foundational

coursework addressing classroom management to student teaching,

we compared the results from this coursework study with the

scores for the 93 programs in this study that were also reviewed on

Bright Spot on teaching use

of praise

Teacher candidates at Hunter College

of The City University of New York are

asked to view a video of their own teaching

and “count the number of positive as well

as negative statements that you make.”

Candidates are then asked if the positive

statements outweigh the negative.

19

Findings

Programs appear to often

evaluate student teachers

on their skill at using

classroom management

strategies that the candidates

never practiced or even

encountered in previous

coursework.

our Classroom Management Standard in the 2013 edition of the Teacher

Prep Review. Program scores on that standard are based on the nature

of the feedback provided to student teachers by university supervisors.

Unfortunately, we found virtually no relationship between coursework

and how student teachers are judged. Indeed, in some instances we

found the opposite. Programs that dedicate lecture time to “managing

misbehavior,” for example, are actually less likely to evaluate teacher

candidates on their skills using this strategy than programs that don’t

spend lecture time on the strategy. No program taught candidates

about the Big Five classroom management strategies and then evaluated

them on how well they implemented the strategies in student teaching.

Bright Spots

St. Mary’s College of Maryland’s graduate elementary and

graduate secondary programs and the University of Washington

– Seattle’s graduate elementary program all teach three of the

Big Five (rules, routines, and misbehavior) in addition to at least

one of the other second-tier strategies (least intrusive means)

and address each of these strategies in their student teaching

feedback.

We also undertook an exhaustive “cross-program” analysis of nine

programs to see if we could nd examples of how teacher preparation

threaded training in classroom management through all required

courses and student teaching. Though the sample was small, the

systematic coherence lacking in the 93-program analysis described

above was, not surprisingly, no more apparent.

Following is a summary of what was found.

Of the nine programs included in these case studies, seven show a

very inconsistent relationship between what is taught in coursework

and what is evaluated in student teaching. Indeed, these programs

often evaluate student teachers on their skill at using classroom

management strategies that the candidates never practiced or even

encountered in previous coursework.

34

One program achieves coherence

between coursework on classroom management and feedback, but in

the worst possible way: addressing classroom management in neither.

What explains the incoherence? The absence of an institutional

consensus about how teacher candidates should be prepared in

classroom management (which will be discussed more in this report’s

conclusion), combined with a higher education tradition of deferring

20

?

No

course

Secondary strategies

CBD

No course

CBDCBD

Big Five

No course

CBDCBDCBDCBD

At least 1 lecture

At least 1 assignment

Student teaching feedback

At least 1 lecture

At least 1 assignment

Student teaching feedback

At least 1 lecture

At least 1 assignment

Student teaching feedback

At least 1 lecture

At least 1 assignment

Student teaching feedback

At least 1 lecture

At least 1 assignment

Student teaching feedback

At least 1 lecture

At least 1 assignment

Student teaching feedback

At least 1 lecture

At least 1 assignment

Student teaching feedback

At least 1 lecture

At least 1 assignment

Student teaching feedback

At least 1 lecture

At least 1 assignment

Student teaching feedback

Program AProgram BProgram CProgram DProgram EProgram FProgram GProgram HProgram I

Fig. 16 Summary of cross-program analyses

CBD means “could not be determined”

The classroom management topics found on the student teaching observation/evaluation instruments are generally not

addressed in candidates’ earlier coursework, and vice versa. The topics on these instruments do not always connect to any

lecture or assignment. Strategies that were taught in coursework often cannot be found on student teaching instruments.

Rules

Routines

Praise

Misbehavior

Engagement

Least intrusive

means

Physical

environment

Motivation

Parent/Community

involvement

Diversity/Cultural

factors

Social/

Emotional factors

Other (e.g., school

management

plans, student

responsibility)

Classroom

management:

Topic not specified

Big Five Secondary strategies

Classroom management strategies

21

Findings

to faculty prerogatives, produce a muddled form of preparation. All too often, individual instructors are allowed to

decide what is important to teach and what is not, with little regard for the overall integrity of the training provided by

the program, which may or may not have even articulated a picture of how its training should be constituted.

These full analyses — including a wealth of information taken from syllabi, textbooks and observation/evaluation

instruments in all of a program’s courses addressing classroom management — are found in Appendix E.

The bottom line on Findings 1 though 5

Teacher educators often make the claim that NCTQ analyses fail to discern various aspects of professional training

because the training is “embedded” in preparation in a holistic manner that simply can’t be detected in reviews of

coursework materials. Whatever the nature of this “embedded” training, we believe that our ndings to this point,

especially Finding 5, demonstrate that embedding classroom management training everywhere is a recipe for adequately

covering it nowhere.

Findings 1 through 4 summarize what we found in the way of classroom management instruction and practice under

the many different rocks we uncovered, and it was generally far too little. Finding 5 lines up in a row all of the rocks

in a program to illustrate how classroom management instruction, practice and feedback would be experienced by

individual teacher candidates.

The exhaustive cross-program analysis we performed for Finding 5 paints a clear picture of how classroom management

instruction, practice and feedback is actually experienced by individual teacher candidates. What is embedded is incoherent:

Most of the programs we examined evaluate teacher candidates on their skill at using classroom management strategies

that the candidates have never practiced — or even encountered in previous coursework — or teach skills on which

candidates are never evaluated.

35

Given what we have found — and the prerogatives accorded to higher education faculty, with each instructor given

leeway to teach what he or she wants — it is hard to see how embedding classroom management training can actually

help teacher candidates master the skills they need to enable learning in their classrooms.

Finding 6: The eld of teacher education has not reached any sort

of consensus on the “who, what, where, when or why” of

classroom management preparation.

Most programs do not appear to draw from the research when deciding which classroom management strategies are

most likely to be effective and therefore should be taught and practiced. Especially disfavored are research-based

strategies suggesting that teachers need to frame consequences for misbehavior, foster student engagement, and

— most markedly — use praise to reinforce positive behavior. Half of all programs ask candidates to develop their

own “personal philosophy of classroom management,” as if this is a matter of personal preference.

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

22

As NCTQ has found in its other studies of teacher preparation, there is no common approach the eld of teacher

education takes to deliver the instruction and practice teacher candidates need.

There is no agreement on how many courses are needed.

The number of courses in which classroom management is addressed ranges from none up to ve per program. Most

programs embed classroom management topics in an average of two courses, though those courses also address

several other unrelated subjects.

As shown on p. 12, only 4 percent of programs dedicate the equivalent of a full course or more to classroom management

alone.

36

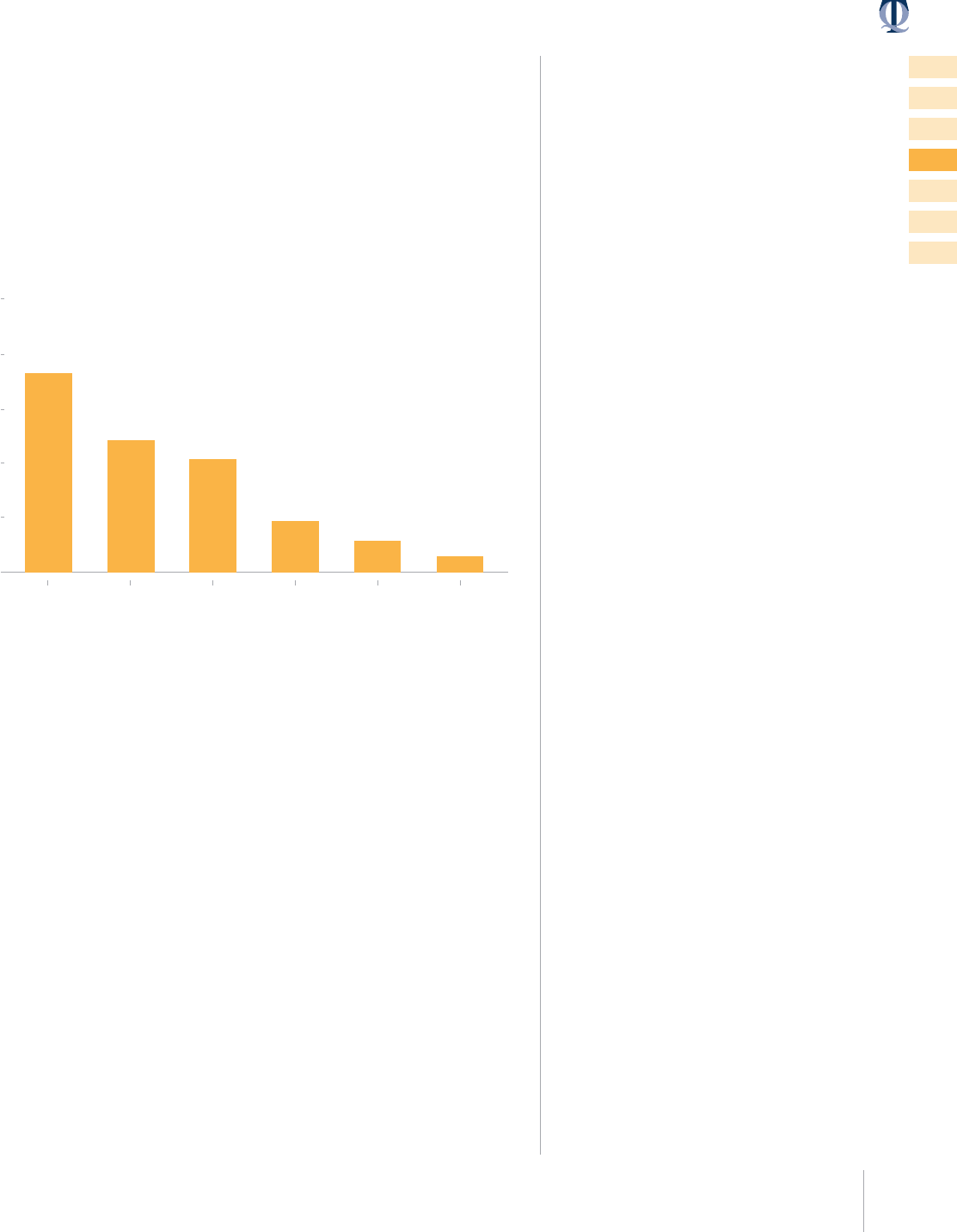

Fig. 7 In how many courses do teacher prep programs address classroom management?

50

40

30

20

10

0

0 1 2 3 4 5

Number of courses

Percent of programs

(N=122 programs)

Programs are almost evenly divided in their choice to consolidate classroom management instruction in one course or

distribute it across more than one course.

There is also no consensus about where in the sequence of coursework classroom

management should be taught.

Most often classroom management is embedded in methods courses, but it can also be found in educational psychology

courses, special education courses and, of course, in a fair number of courses appropriately titled “classroom management.”

23

Findings

The absence of instruction on classroom management in

special education courses is glaring.

While the Big Five are general strategies relevant for all classrooms,

the behavior issues posed by some students with special needs do

demand specic treatment. Yet only 15 percent of the programs address

classroom management in special education coursework taken by

elementary and secondary teacher candidates.

Fig. 8 Where is classroom management taught?

50

40

30

20

10

0

Methods Classroom Education Special Assorted All others

management psychology education practicum

Percent of courses

(N=213 courses)

Type of course

Classroom management is most commonly addressed in methods, classroom

management, and educational psychology instructional coursework.

Research does not generally inform what gets taught.

As discussed earlier, only a third of programs address at least four

of the Big Five. It is telling that the likelihood of doing so does rise if

a program dedicates a course to classroom management. Consistently,

praise is barely mentioned in any type of course, including in educational

psychology courses in which one would expect it to gure prominently

due to its connection to psychological theories regarding the nature

of positive reinforcement as an operant principle.

37

Your best lesson plan of

the year won’t go well

if you don’t have good

classroom management.

– 3rd year teacher

Respondent to

NCTQ survey

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

24

Fig. 9 Which Big Five classroom management strategies are addressed by each of the course types in

which classroom management instruction is commonly offered?

Special education

(N=17 courses)

Education psychology

(N=32 courses)

Classroom managment

(N=48 courses)

Methods

(N=64 courses)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Percent of courses

(N=161 courses)

Rules

Routines

Praise

Misbehavior

Engagement

Each type of instructional course addresses a different mixture of the Big Five. Compared to any other type of course, classroom

management courses consistently address more, but not all, of the Big Five strategies.

Note: Thirty-three courses that only contain ambiguous references to classroom management topics were removed from

the sample.

Textbooks used to teach classroom management content reveal the incoherence in the eld.

Most foundational courses in this study (166 courses) use at least one textbook addressing classroom management,

but few courses share the same text, as 141 different texts across the programs are required. Almost all of these

texts (70 percent) are only used in a single course for a single program on a campus. Only a handful of textbooks are

used by four or more programs. This nding is similar to the nding on reading preparation: NCTQ’s recent review

of reading courses identied 866 different reading textbooks among 692 programs, and more continue to ood the

eld.

38

Only about half of the programs (56 percent) have a course assigning a textbook that focuses primarily on issues surrounding

classroom management. Courses in the remaining programs either never assign a classroom management textbook

(6 percent) or assign one that only devotes a few chapters to the topic (38 percent).

39

25

Findings

Classroom management

texts most commonly used

in foundational coursework

n Charles, C. M., & Senter, G. W. (2008).

Building Classroom Discipline (six

programs at six IHEs).*

n Evertson et al. (2009). Classroom

Management for Elementary Teachers

(ve programs at four IHEs).*

n Marzano, R. J. (2003). Classroom

Management that Works: Research-

based Strategies for Every Teacher

(four programs at three IHEs).*

n Weinstein & Novodvorsky (2011). Middle

and Secondary Classroom Management

(four programs at four IHEs).

Largely unscientic textbook:

n Kohn, A. (2006). Beyond Discipline: From

Compliance to Community (ve programs

at four IHEs).

Commonly used textbook

addressing classroom management

and other topics:

n Wong, H. K., & Wong, R. S. (multiple

editions). The First Days of School: How

to Be an Effective Teacher.

* More information on these textbooks can be

found in Appendix E.

Of the six most commonly used textbooks (used by four or more

programs, see textbox to the right), ve address the Big Five.

Only Beyond Discipline by Ale Kohn disagrees with the bulk of

scientic research.

Finding 7: State standards on

teacher prep do not

focus on the classroom

management strategies

for which research

support is strongest.

The vast majority of public school teachers are recommended for

certication by traditional teacher preparation programs in institutions

that have been approved to offer certication by state agencies.

In turn, these agencies base their

approval on a program’s adherence

to regulations that speak explicitly to teacher preparation itself or

to professional competencies for all teachers.

40

While every state has regulations that have at least a glancing

mention of the need for teachers to know how to manage a

classroom, most states’ regulations seem to be poorly informed

by research. For example, the approach to classroom organization

that is strongly supported by research — the need for teachers to

employ a combination of both rules and routines — is mentioned

in regulations of less than half of all states (19). More commonly,

state regulations do address engagement (29 states), but nearly

as many address motivation (24), which lacks strong research

support. States are more likely to mention strategies for which

the research base is not as strong — such as managing the

physical classroom environment (24 states) and maintaining student

motivation (24 states) — than some research-supported strategies,

such as addressing misbehavior (13 states) and using praise

(only two states).

Training our future teachers: Classroom management

26

www.nctq.org/teacherPrep

Regulations in

California, New Mexico,

Oregon and Texas are

strong and address

four of the Big Five.

Fig. 10 How many states have regulations addressing the Big

Five strategies?

50

40

30

20

10

0

Rules Routines Praise Misbehavior Engagement