New York State

Disadvantaged Communities

Barriers and Opportunities Report

Final Report | Report Number 21-35 | December 2021

New York State Disadvantaged Communities

Barriers and Opportunities Report

Final Report

New York State Energy Research and Development Authority

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

New York Power Authority

NYSERDA Report 21-35 December 2021

ii

Abstract

New York State’s Disadvantaged Communities Barriers and Opportunities Report, required by the

Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (Climate Act), assesses why some communities

are disproportionately impacted by climate change and air pollution and have unequal access to clean

energy. This report identifies barriers faced by disadvantaged communities in having the opportunity

to own and access the goods and services necessary to:

• Make homes energy efficient, weather-proofed, and powered by renewable energy;

• Obtain and utilize clean transportation such as fuel efficient and electric cars, vans,

trucks, buses, and bikes, as well as walkable streets and livable neighborhoods; and

• Ensure health and safety in the face of more frequent and more severe weather events

driven by climate change.

This report recommends actions for New York State agencies to design climate mitigation and adaption

programs through a lens of justice. The recommendations will be incorporated into New York State’s

Climate Action Council’s final scoping plan, paving the way for the benefits of clean energy and a safe

and healthy environment for all New Yorkers.

Keywords

New York State; New York State Energy and Research Authority; NYSERDA; Department of

Environmental Conservation; DEC; New York Power Authority; NYPA; Climate Act; Climate

Leadership and Communities Protection Act; disadvantaged communities; barriers; opportunities;

recommendations; renewable energy generation; energy efficiency; zero-emissions transportation;

low-emissions transportation

iii

Acknowledgments

Many individuals provided the State with information, feedback, and expertise that has been

incorporated into this report. Thanks go specifically to Illume Advising, LLC and Industrial Economics,

Inc for their consultation services provided under contract with NYSERDA, and to Elizabeth Boulton

of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority and Sameer Ranade of New York

State’s Climate Action Council who co-managed the research, organizational, and outreach initiatives

required to complete this report. In addition, substantial contributions to the research came from the

public, including members of the Climate Justice Working Group, those who gave oral and written

public comments, and the numerous community members and organizations who lent their expertise

and time to provide direct feedback and encourage their fellow New Yorkers to participate in the public

processes that informed this report.

Lastly, the following agencies designated study advisors to provide extensive input during the

research process: the New York State Energy and Research Development Authority, Department

of Environmental Conservation, Department of Health, Department of Public Service, Department

of Transportation, and New York Power Authority. Additional invaluable input was provided by the

New York State Department of Homes and Community Renewal, the Department of Labor, and the

Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance.

iv

Table of Contents

Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... ii

Keywords ..................................................................................................................................... ii

Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................... iii

List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... v

Acronyms and Abbreviations .................................................................................................... v

Summary .................................................................................................................................. S-1

1 The Vision of the Climate Act ............................................................................................. 1

2 Legislative Basis of the Report .......................................................................................... 3

3 Report Objectives and Approach ....................................................................................... 4

3.1 Objectives of the Report ................................................................................................................ 4

3.1.1 Identifying Barriers ................................................................................................................ 4

3.1.2 Developing Recommendations and Opportunities ................................................................ 4

3.2 Role of the Report in the Climate Act ............................................................................................ 5

3.3 Key Operating Terms .................................................................................................................... 5

3.4 Data Collection Approach and Process ........................................................................................ 7

4 Barriers ................................................................................................................................. 9

4.1 Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 9

4.1.1 Categories of Barriers ........................................................................................................... 9

4.1.2 Barriers Across the Five Service and Commodity Areas .................................................... 11

4.2 Key Barriers to Access and Ownership ...................................................................................... 12

5 Recommendations and Opportunities Overview ............................................................ 17

5.1 Overview and Background .......................................................................................................... 17

5.2 Recommendations ...................................................................................................................... 17

6 Next Steps

................................

.......................................................................................... 55

6.1 Phase 1—Assessment of Recommendations ............................................................................. 56

6.2 Phase 2—Implementing Recommendations ............................................................................... 57

6.3 Phase 3—Continued Assessment and Refinement .................................................................... 57

7 References ......................................................................................................................... 58

Appendix A. Research Approach .......................................................................................... A-1

Appendix B. Defining Disadvantaged Communities ........................................................... B-1

Appendix C. Principles of Community Engagement ........................................................... C-1

Endnotes ................................................................................................................................ EN-1

v

List of Tables

Table 1. Services and Commodities Definitions and Examples .................................................... 7

Table 2. Physical and Economic Structures and Conditions. ..................................................... 13

Table 3. Financial and Knowledge Resources and Capacity Barriers. ....................................... 14

Table 4. Perspectives and Information Barriers. ......................................................................... 15

Table 5. Programmatic Design and Implementation Barriers. .................................................... 16

Table 6. Summary of Recommendations and Opportunities ...................................................... 18

Acronyms and Abbreviations

BIPOC Black, Indigenous, People of Color

CAC Climate Action Council

CJWG Climate Justice Working Group

Climate Act Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act

COAD Community Organizations Active in Disaster

CSC Climate Smart Communities (DEC program)

DEC New York State Department of Energy Conservation

DOH New York State Department of Health

DOL New York State Department of Labor

DOT New York State Department of Transportation

DPS New York State Department of Public Service

EV Electric Vehicle

GHG Greenhouse Gas

HCR New York State Department of Homes and Community Renewal

HEAP Home Energy Assistance Program (Federal Program)

HPD New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development

NYC New York City

NYCHA New York City Housing Authority

NYPA New York Power Authority

NYS New York State

NYSERDA New York State Energy and Research Development Authority

OTDA New York State Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance

REDC Regional Economic Development Council

SNAP Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (Federal Program)

WAP Weatherization Assistance Program (NYSERDA Program)

S-1

Summary

The Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (Climate Act) was signed into law on

July 18, 2019. The Climate Act aims to address the rising impacts and inequities of climate change

in New York State by setting tangible requirements and goals for reaching economy-wide carbon

neutrality and significant renewable energy expansion while expanding benefits and community

ownership to disadvantaged communities. This law also requires that the Department of Environmental

Conservation (DEC), in cooperation with the New York State Energy Research and Development

Authority (NYSERDA) and the New York Power Authority (NYPA), (1) prepare a report on the

barriers faced by disadvantaged communities in accessing and owning services and commodities

(e.g., renewable energy systems and cooling shelters) relating to climate change mitigation and

adaptation as well as (2) identify opportunities to increase access and community ownership. The

recommendations from this report will be incorporated, as appropriate, into the Climate Action

Council’s (CAC) Scoping Plan.

S.1 Report Development

In developing this report, DEC, NYSERDA, and NYPA utilized the services of ILLUME

Advising, with support from Industrial Economics (the study team), to assist in data collection

and report preparation. The study team conducted several activities to identify critical barriers that

will affect access to, and ownership of, certain services and commodities identified in the Climate Act

by disadvantaged communities and explored opportunities to break down these barriers. These services

and commodities are listed below:

• Distributed renewable energy generation.

• Energy efficiency and weatherization investments.

• Zero-emission and low-emission transportation options.

• Adaptation measures to improve the resilience of homes and local infrastructure

to the impacts of climate change, including but not limited to microgrids.

• Other services and infrastructure that can reduce the risks associated with

climate-related hazards, including but not limited to:

o Shelters during flooding events.

o Medical treatment for asthma and other conditions that could be exacerbated

by climate-related events.

S-2

The study team engaged State agency staff from the Department of Health (DOH), Department of

Public Service (DPS), Department of Transportation (DOT), Department of Labor (DOL), Office

of Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA), and the Homes and Community Renewal (HCR)

to inform the research activities, help recruit residents and organizations to provide feedback, and

provide input into the report. Research activities included the following: (1) a secondary research

review, including publications from academic institutions, non-governmental organizations, and

agencies inside and outside New York State; (2) eight focus groups, engaging 65 individuals who

live or work in disadvantaged communities across the State; and (3) two public hearings, as required

by the Climate Act, attended by 97 individuals. The study team also solicited written comments from

individuals through a public notice, an announcement on the Climate Act website, and recruitment

efforts with community organizations, capturing feedback beyond the hearings and focus groups.

The study team consulted with the Climate Justice Working Group (CJWG) and shared the research

plan at several points, including the list of draft barriers and opportunities. Additionally, the study

team reviewed CAC meeting materials to inform the development of the report.

S.2 Barriers

To identify the barriers that affect access and participation in the services and commodities listed

above, the study team first drew on the extensive research already completed by academic researchers,

agencies in New York State, other states, and other non-governmental organizations. The study team also

incorporated insights from focus groups, public hearings, and written comments. Key barrier categories

were identified that span across the services and commodity areas highlighted in the Climate Act. They

include the following:

• Physical and Economic Structures and Conditions: This category encompasses broad

economic conditions and historical patterns of inequality that exist in the broader context of

all programs and affect access and ownership of infrastructure. “Structures” in this context can

include both physical structures (e.g., aging housing stock that requires additional investment

to support new technologies), and economic and social structures.

• Financial and Knowledge Resources and Capacity: These barriers relate to household,

community, and agency capacity, and to resource availability for residents, communities,

and agencies. Time represents a critical limitation across all levels of community. On the

community and business levels, resource gaps can refer to limited personnel and data

systems and access to professional networks, as well as access to different financing options.

S-3

• Perspectives and Information: Barriers within this category describe community perceptions

of agencies and programs, including lack of trust in local and State authorities that, in some

cases, has developed over decades. In addition, this category includes knowledge gaps and

lack of awareness of programs and resources often due to complex or opaque bureaucratic

and administrative structures.

• Programmatic Design and Implementation: Programmatic barriers include the various

factors in program design and implementation that can limit participation and success,

including lack of information to inform program design and goals, complex eligibility

requirements, insufficient emphasis on engaging communities in the design process,

and limited alignment across agencies and resources.

Specific barriers by service and commodity area are included in section 4.

S.3 Recommendations and Opportunities

To identify opportunities to increase access and ownership of the services and commodities

identified in the Climate Act, the study team reviewed programs, services, and strategies found

through the secondary research review, feedback from agency staff and the CJWG, CAC meeting

materials, and insights from the focus groups, public hearings, and written comments. The study

team reviewed these opportunities for key themes and principles to formulate a list of overarching

recommendations for State agencies and other organizations offering programs or services to

disadvantaged communities.

The study team identified recommendations within three key themes, including (1) ensure processes

are inclusive, (2) streamline program access, and (3) address emerging issues. Table S-1 provides

an overview of the high-level report recommendations by theme. Full descriptions of the report

recommendations are included in section 5.

S-4

Table S-1. Recommendations by Theme Area

Theme Recommendations

1. Co-design programs or projects with and for communities.

Ensure Processes

2. Provide meaningful opportunities for public input in government processes

are Inclusive

and proceedings.

3. Work across intersecting issues and interests to address needs holistically.

4. Transition to program models that require little to no effort to participate

and benefit.

Streamline

5. Establish people-centered policies, programs, and funding across local,

Program Access

State, and federal governments.

6. Find and support resource-constrained local governments.

7. Mobilize citizen participation and action.

Address Emerging

Issues

8. Improve housing conditions and adherence to local bui

lding codes.

While t

his report does not include a comprehensive assessment or review of New York State agency and

authority programs, it should be acknowledged that the State has many programs working closely with

communities to address the barriers identified. In several cases, State agencies are already incorporating

different elements of the report recommendations into their programs. For example, DEC has its own

Office of Environmental Justice, which works to build community capacity and engages communities

in generating climate solutions. Additional program examples are highlighted in section 5.

S.4 Next Steps

This report and the barriers, recommendations, and opportunities identified within it represent an

initial step in the process of ensuring that disadvantaged communities have access to, and community

ownership of, the services and commodities needed to mitigate and adapt to climate change. In some

instances, significant staff effort will be required to implement the report recommendations. For

example, some recommendations may have policy implications that must be addressed or require

additional funding and staffing to facilitate program co-design with disadvantaged communities.

As a next step to continue this work, State agencies will assess the recommendations and complete a

needs assessment. DEC is committed to accepting feedback from the public on this report at any time.

After refining the recommendations with any additional needs and adjustments, information from this

report will be presented to the CAC and the recommendations will be included in the final version of its

scoping plan. Additional details on next steps are included in section 6.

1

1 The Vision of the Climate Act

The devastating effects of climate change are evident across New York State. Average temperatures

are increasing, along with the frequency of dangerous heat events, particularly in urban areas. Coastal

and inland flooding is happening more often. Along the coastline, sea levels are rising. The agricultural

growing season is becoming longer, but late frost, floods, drought, and extreme heat threaten crops.

Geographic ranges of plant and wildlife species are shifting, while biodiversity is diminishing.

Catastrophic weather events are more likely, and their costs to human life and to our built environment

are increasing. In short, climate change is already having a profound impact on the communities of

New York State. Department of Environmental Conservation’s (DEC) August 2021 report Observed

and Projected Climate Change in New York State: An Overview notes the following:

1

• New York State has warmed at an average rate of 0.25°F per decade since 1900.

2

Annual

average temperatures have increased in all regions of the State. More recently, warming

has accelerated: since 1970, the statewide annual average temperature has risen about

0.6°F per decade, with winter warming exceeding 1.1°F per decade.

3

• The nationwide trend of increasingly frequent extreme precipitation events has been

particularly pronounced in the Northeast, including New York State.

4

The proportion

of total annual precipitation falling in the heaviest 1% of events increased by 38% in

the Northeast, between the periods 1901–1960 and 1986–2016. More recently, from

1958–2016, this increase was 55%.

5

These trends are projected to continue and worsen, bringing more frequent flooding to both coastal

and inland areas, along with more frequent and more lengthy extreme heat events.

The impacts of climate change will not fall equally across all New Yorkers. A growing body of

research over the past decade has highlighted the links between vulnerability to the effects of climate

change and persistent disparities in economic opportunity, education, housing, environmental quality,

health status, mobility, and health care access and quality as well as by race and ethnicity, gender

identity, and socioeconomic status. These intersecting impacts affect populations across the State but

are also geographically concentrated in areas that have been historically underserved and marginalized.

These areas are characterized by older housing stock, less infrastructure investment, and historic burdens

increasing risks and vulnerabilities. These communities often have higher concentrations of non-White

racial and ethnic populations as well as populations characterized by lower incomes, education levels,

language barriers, immigration status, and greater vulnerability to climate change. These populations

are more likely to suffer disproportionately from compound or cascading climate or environmental

2

hazards. The COVID-19 pandemic both highlighted and exacerbated these disparities, adding urgency

to equity-focused efforts across State and local agencies.

6

To address these intersecting issues, New York State’s nation-leading Climate Leadership and

Community Protection Act (Climate Act) was signed into law on July 18, 2019. The Climate Act

aims to address the rising impacts and inequities of climate change by setting tangible requirements

and goals for reaching economy-wide carbon neutrality and significant renewable energy expansion

while expanding benefits and community ownership to disadvantaged communities. Among its key

provisions, the Climate Act sets requirements to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions 85% below

1990 levels by 2050, use renewable energy to provide at least 70% of New York State’s electricity by

2030, achieve a zero-emission electricity system by 2040, and invest resources to ensure that at least

35% of the benefits of spending, with a goal of 40%, are directed to disadvantaged communities. The

Climate Act explicitly centers on the intertwined issues of equity and climate change vulnerability.

As part of its findings and declaration, the Legislature noted that:

Climate change especially heightens the vulnerability of disadvantaged communities,

which bear environmental and socioeconomic burdens as well as legacies of racial and

ethnic discrimination. Actions undertaken by New York State to mitigate greenhouse gas

emissions should prioritize the safety and health of disadvantaged communities, control

potential regressive impacts of future climate change mitigation and adaptation policies

on these communities and prioritize the allocation of public investments in these areas.

The directives in the Climate Act anticipate a government-wide effort that recognizes the fundamental

changes needed across the economy to address climate change vulnerability and equity. Specifically,

the Climate Act:

1. Establishes the New York State Climate Action Council (CAC), a 22-member committee

with representatives from State agencies and authorities, members appointed by the leaders

of the Senate and Assembly, and two non-agency expert members appointed by the governor.

2. Directs the CAC to prepare a scoping plan that will set out recommendations for attaining

the statewide GHG emission limits across all sectors of the economy.

3. Creates the Climate Justice Working Group (CJWG) to advise the CAC and establish

criteria for identifying disadvantaged communities based on considerations related to

public health, environmental hazards, and socioeconomic factors.

In addition, section 6 of the Climate Act requires the development of a report on “barriers to, and

opportunities for, community ownership of, services and commodities in disadvantaged communities,”

which will be submitted to the Governor, the Senate, and the Assembly, and be posted to the DEC

website. This report therefore fulfills this requirement.

3

2 Legislative Basis of the Report

Section 6(1)-(2) of the Climate Act requires that DEC, in cooperation with the New York State

Energy and Research Development Authority (NYSERDA) and the New York Power Authority

(NYPA), and following two public hearings, develop a “report on barriers to, and opportunities

for, community ownership of services and commodities in disadvantaged communities,” including:

• Distributed renewable energy generation.

• Energy efficiency and weatherization investments.

• Zero-emission and low-emission transportation options.

• Adaptation measures to improve the resilience of homes and local infrastructure to the impacts

of climate change, including but not limited to microgrids.

• Other services and infrastructure that can reduce the risks associated with climate-related

hazards, including but not limited to:

o Shelters and cool rooms during extreme heat events.

o Shelters during flooding events.

o Medical treatment for asthma and other conditions that could be exacerbated by climate-

related events.

To support development of the report, the study team sought input and feedback from other State

agencies throughout the work, as required by the Climate Act, with staff from the Department of

Health (DOH), Department of Public Service (DPS), and Department of Transportation (DOT)

serving as study advisors. Staff from the Department of Labor (DOL), Office of Temporary and

Disability Assistance (OTDA), and Department of Homes and Community Renewal (HCR) were also

engaged to provide input. The CJWG was also consulted as barriers and opportunities were identified.

Per section 6(2) of the Climate Act, this report will be submitted to the Governor, the Assembly, and

the Senate and posted to the DEC website. In consultation with the CAC, DEC will amend the CAC’s

Scoping Plan for statewide GHG emission reductions to include recommendations from the report.

4

3 Report Objectives and Approach

The following sections provide additional background on the overarching objectives of the report, its

role within the Climate Act, key operating terms that provide bounds around the scope of the report

and its contents, and the data collection process.

3.1 Objectives of the Report

As previously noted, the Climate Act requires this report to identify the “barriers to, and opportunities

for, access to or community ownership” of the services and commodities that are key to combating

climate change. As stated in the law, this report will “include recommendations on how to increase

access” to these services and commodities. The approach for identifying barriers and developing

recommendations and opportunities (or tactics), is described further below.

3.1.1 Identifying Barriers

To identify and describe the most significant barriers and difficulties that affect access to and

participation in programs and services, the study team first drew on the extensive work already

done by academic researchers, agencies in New York State and other states, and non-governmental

organizations. This review, with feedback from agency staff and members of the CJWG, culminated

in an initial typology of barriers to be further investigated through this study.

In addition, the study team incorporated insights from focus groups, public hearings, written public

comments, and input from CAC meeting materials and notes. The result is a refined summary of the

suite of barriers that affect access to, and community ownership of, the services and commodities

needed to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

3.1.2 Developing Recommendations and Opportunities

The CAC’s Scoping Plan will provide recommendations for achieving statewide GHG emission

reductions, including regulatory measures. This report identifies the opportunities for accessing or

owning the services and commodities (listed in section 2 above) that may be included in the scoping

plan to meet GHG emission reduction directives. Opportunities were drawn from secondary research

5

review, feedback from agency staff and the CJWG, input from CAC meeting presentations and notes,

along with discussions held during focus groups, and input received through public hearings and written

public comments. The study team assessed these opportunities for key themes and principles to formulate

the overarching recommendations.

3.2 Role of the Report in the Climate Act

This report is intended as a standalone resource to inform the implementation of applicable provisions

of the CAC’s Scoping Plan in disadvantaged communities. Furthermore, the recommendations in this

report are to be shared with the Legislature and Governor, and the public. It will be posted on the Climate

Act and DEC websites to further New York State’s efforts to increase disadvantaged communities’ access

to and community ownership of services and commodities to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

It is important to highlight that the scoping

plan recommends the “what” to do, while this report identifies

the “how” to do it. Therefore, the report does not recommend specific programs or policies, such as GHG

emission reduction initiatives, or procurement or contracting policies, but rather, guidelines and strategies

for designing and delivering the programs and services that will be defined in the scoping plan to

disadvantaged communities.

A limita

tion to this report is its reliance on a finite number of sources for information. Although

the report draws on a range of sources, including primary research with community members and

organizations, it is recognized that a more comprehensive community and agency engagement process

may produce more complete results. Full and effective implementation of the scoping plan will require a

broad-based effort to engage residents of disadvantaged communities in program design and identification

of program priorities. An expanded effort to identify barriers and opportunities could also help to refine

and add to the recommendations and opportunities presented here and may further inform the set of

barriers, integrating community and agency-level feedback to reflect more community and agency

experiences and perspectives.

3.3 Key Operating Terms

Key terms used in this report, and the interpreted or defined meanings, are summarized below. The

study team looked to the Climate Act for definitions where available and worked with agency staff

to clarify these terms as needed.

6

• Access: The ability to use and benefit from programs or services offered to mitigate (i.e., reduce

GHG emissions) or adapt to the effects of climate change.

• Co-Design: Creating programs, projects, or plans with relevant stakeholders (e.g., affected

community members, and community organizations or groups) to ensure that the results meet

their needs.

• Community Ownership: Includes the following interpretations: (1) ownership by individuals

or businesses that reside within a disadvantaged community, (2) a collective ownership (like

cooperative models) of services or resources by several community members, and/or (3) the

result of a decision-making process that originates from within the community, is informed by

the community’s needs and values, and retains the benefits within the community.

• Community Members: People that live or work within disadvantaged communities.

• Community Organization: Organizations (typically nonprofits) founded to serve the various

needs of people within a local community. May offer services, or programs designed to help or

support community members, as well as advocacy in some cases.

• Community Group: A collective of people who organize around a specific issue or set of

issues but are not bound to an established organization registered with New York State.

• Disadvantaged Communities:

7

Defined in the Climate Act to mean “communities that bear

burdens of negative public health effects, environmental pollution, impacts of climate change,

and possess certain socioeconomic criteria, or comprise high-concentrations of low- and

moderate-income households.” Concurrent with the creation of this report, and as required by

the Climate Act, the CJWG is determining criteria by which to define a disadvantaged

community. Additional information is provided in appendix B.

• Local Government: Any city, town, village, or county government office or agency.

• Program: A local, State, or federal offering with a goal of community improvements or

benefits. Often may provide technical or financial assistance.

• Project or Plan: An idea or concept that is designed to achieve a particular aim to benefit the

community. May result in a program, service, or commodity that is provided to a community.

For example, a community-owned solar project, climate adaptation plan, or emergency

response plan.

• Services and Commodities: Interpreted to mean the programs, offerings, resources, and assets

within the five areas listed in section 2 to which New York State wants to increase access to and

ownership of by disadvantaged communities. These five services and commodities are further

defined in Table 1 below, including examples.

7

Table 1. Services and Commodities Definitions and Examples

Services and

Commodities

Definition Example Actions or Initiatives

Distributed Renewable

Energy Generation

Electricity generated from

renewable sources (solar, wind,

etc.) near the point of use, as

opposed to centralized

generation at power plants.

Individuals or Businesses: Small hydro or wind

installation, installation of solar photovoltaic panels,

community solar subscription models.

Municipal or Community-Based: Community-

owned solar or storage, adoption of codes or

ordinances for solar-ready new construction.

Energy Efficiency and

Weatherization

Investments

Optimizing energy use within

buildings to reduce generation

needs; weatherproofing

buildings to protect them from

extreme cold and heat,

moisture, and other natural

elements.

Individuals or Businesses: Heat pumps in

rental/multifamily housing, healthy homes initiatives;

direct installation measures with “energy

ambassadors,” deep energy retrofits.

Municipal or Community-Based: Electrification of

public housing; increased energy and safety code

enforcement.

Zero-emissions and

Low-emissions

Transportation Options

Transportation options that run

completely free of GHG

emissions or have low

emissions.

Individuals or Businesses: Mobility options without

a vehicle, e.g., active transportation, public transit,

ridesharing.

Municipal or Community-Based: Increased

infrastructure and availability for public transportation

systems, such as bus lines, train stops, etc.; electric

vehicle (EV) charging stations.

Adaptation Measures to

Improve Resilience of

Homes and Local

Infrastructure

Designing landscapes,

infrastructure, buildings, and

social systems intentionally to

prevent or reduce disruptions

related to climate-related

weather and extreme events.

Individuals or Businesses: Resilience audits for

homes or businesses, storm-hardening rental

properties, green/natural features, and shade trees

on private property.

Municipal or Community-Based: Upstream flood

mitigation, community resilience plans for public

infrastructure and buildings, microgrid development,

green/natural features and/or shade trees.

Other Services and

Infrastructure to Reduce

Risks associated with

Climate-Related

Hazards

Offering services to decrease

risks (especially health and

safety related) during extreme

heat and weather events.

Individuals or Businesses: Using community

shelters during heat or flooding, installing mini-split

heat pumps.

Municipal or Community-Based: Local emergency

planning, offering cooling centers or storm shelters,

asthma initiatives or heathy homes initiatives.

3.4 Data Collection Approach and Process

NYSERDA, DEC, and NYPA, along with the study team, performed the following data collection

activities to inform the report. These activities were pursued in close collaboration with several other

State agencies, including DOH, DPS, DOT, DOL, OTDA, and HCR. Additionally, the study team

consulted with the CJWG and the CAC to receive input and feedback on the potential barriers

and opportunities.

8

The research activities are summarized in the list below (see appendix A for more details):

1. P

erformed secondary research review focusing on existing literature, including from

academic institutions, non-governmental organizations, and agencies (from within and

outside of New York State), in addition to plans and proceedings to identify barriers

faced by disadvantaged communities and approaches to address those barriers.

2. Held eight focus groups with a total of 65 participants (including one group held in Spanish).

Participants were recruited and selected purposefully to ensure representation across the State.

Focus group discussions centered on four of the five service and commodity areas, including

renewable distributed energy resources, low- or no-emission transportation options, resilience

and adaptation, and climate hazards related to health and safety. Since there is enough secondary

research on the barriers to accessing energy efficiency and weatherization investments for

disadvantaged communities, it was decided to dedicate the focus groups to the other four

topics. These discussions explored people’s experiences as residents, business owners, or

nonprofit or local government staff accessing and participating in public processes and

programs, and barriers and opportunities for greater access and ownership.

3. Facilitated two public hearings attended by 97 individuals (21 of which were speakers),

as required per the Climate Act, and received 26 written public comments. Feedback was

received on the barriers faced in accessing or owning the services and commodities

highlighted in the legislation, as well as opportunities to break down these barriers.

9

4 Barriers

The following sections provide a high-level overview of the disparities faced by disadvantaged

communities in New York State as well as barriers identified through the research activities of

this study.

4.1 Overview

Barriers are obstacles that disadvantaged communities may face in participating in and advancing

New York State’s efforts under the Climate Act. Obstacles to participation and improvement can

be physical (e.g., aging infrastructure and housing stock or vulnerable geography), behavioral,

perceptual, cultural, social, or economic, such as financial constraints, ownership patterns, and

language and cultural structure.

Barriers can also physically affect movement and access (e.g., to zero emission or low-emission

transportation, health care, or shelter during severe weather events), as well as limit effective access

to and ownership of the infrastructure needed to mitigate and adapt to climate change, such as renewable

energy projects, green infrastructure, and the climate planning process itself. In this vein, many barriers

based on historical patterns of decision-making have prevented the social mobility of certain population

groups while promoting the social mobility of others, resulting in disproportionate exposure to risks and

limited access to mitigation and adaptation services and commodities today. Support of social mobility

will be a critical element in addressing barriers and opportunities in disadvantaged communities;

without that support, disproportionate exposures and inequitable access are likely to increase.

4.1.1 Categories of Barriers

This report organizes key barriers into four categories of overarching “themes” that align with

specific structural conditions routinely faced by disadvantaged communities. The categories of

barriers intersect and overlap to some extent, in part because they emerge from interwoven historical

patterns of exclusion, segregation, and disinvestment in communities. These patterns have affected

the quality of housing, schools, transportation, and electrical infrastructure, and have limited access to

capital, financial opportunities, employment, health care, fresh food, and other resources. However,

the categories generally group issues around specific program design challenges and priorities and are

broadly consistent with categories and topics identified in the literature, providing continuity with

other efforts to address equity. These four categories of barriers are described further below:

10

• Physical and Economic Structures and Conditions: This category encompasses the

structural challenges that characterize the broader context of all programs and affect access

to resources and ownership of infrastructure. “Structures” in this context can include both

physical structures (e.g., aging housing stock that requires additional investment to support

new technologies) and economic and social structures. For example, the “split incentive”

complicates investments in rental properties, because property owners have economic

priorities and power that can differ from and conflict with the priorities of renters.

Discrepancies between rented and owned housing are directly connected to social

inequities. In many cases, these structures reflect the cumulative impact of decades

of systematic disparities in public investment and policy priorities.

• Financial and Knowledge Resources and Capacity: These barriers relate to household,

community, and agency capacity, and to resource availability for residents, communities,

and agencies. Time represents a critical limitation across all levels of community. On

the community and business levels, resource gaps can refer to limited personnel (time

and expertise) and data systems and access to professional networks, as well as access

to different financing options. Residents may also face barriers such as lack of credit and

access to financial services and resources that could enable investment and participation.

• Perspectives and Information: Barriers within this category describe community perceptions

of agencies and programs, including lack of trust in local and State authorities that, in some

cases, has developed over decades. In addition, this category includes limits to understanding

of bureaucratic and administrative structures, awareness of programs and resources, as well

as the relative importance of agency programming compared to competing needs and interests.

Opaque regulatory processes preventing community participation and feedback to agencies

are a primary barrier within this category.

• Programmatic Design and Implementation: Programmatic barriers include the various

factors in program design and implementation that can limit participation and success,

including overly complex bureaucratic procedures, lack of information to inform program

design and goals, complex eligibility requirements, insufficient emphasis on designing with

communities, and limited alignment across agencies, resources, and geographical areas.

These barriers categories may be useful in identifying the types of policies and actions that could

effectively address (and remove) key barriers. In particular, the Programmatic Design and Implementation

category presents a slightly different perspective than the other categories, because the challenges in that

category reflect the design of programs themselves, rather than factors external to the programs.

Examining and addressing the barriers in this category are, therefore, critical to identifying opportunities

for addressing obstacles across the other categories.

11

4.1.2 Barriers Across the Five Service and Commodity Areas

In accordance with the Climate Act’s requirements, the study team addressed barriers that disadvantaged

communities face in accessing or owning services and commodities highlighted in the legislation.

Barriers experienced within each of these five areas are discussed further below.

1. Distributed renewable energy generation programs are often limited by barriers related

to building ownership. Due to physical and economic factors like aging building stock and

infrastructure, buildings in historically underserved and under-resourced communities may

need electrical updates or roof repairs before solar can be installed. Renters may not receive

any monetary benefits from tax credits and may need to deal with challenges and logistics

of installation. For example, programs may not communicate clean energy technology or

program benefits in a way that motivates community members, such as community-scale

renewable energy projects, which have not typically focused on historically underserved

and under-resourced communities.

2. Energy efficiency, weatherization, and electrification programs have deployment constraints

related to inadequate community infrastructure and household-level challenges. For example,

community members may live in old homes and have other more pressing personal issues to

overcome before considering energy efficiency, creating a strain on households with already

limited resources. Community members’ homes may also have structural deficiencies or

health and safety issues leading to their deferral and exclusion from energy efficiency and

weatherization program participation until structural issues are addressed. Further, split

incentives leave landlords with limited motivation to invest in improvements because they

will not recoup the investment; therefore, renters do not have the opportunity to improve

their residences or experience energy savings themselves. Energy efficiency barriers are

well-documented in the literature.

8

3. Zero-emission and low-emission transportation programs may not reach the

populations with the most limited access to clean and safe transportation. For example,

changing the vehicles that New Yorkers use from running on fossil fuels to cleaner options

will improve air quality for everyone, but direct benefits to owners are less likely to affect

those in disadvantaged communities, who may be less able to purchase new electric vehicles,

or may prefer to use public transportation. This makes designing programs to increase

accessibility of low- and zero-emission public transit in disadvantaged communities important.

4. Programs addressing community adaptation of homes, buildings, and infrastructure are

often less accessible to communities with limited capacity; that is, having the right resources

and information available to prioritize and finance improvements. Information on the impacts of

climate change and links between climate change and household and community risk is limited

and challenging to communicate. The relationship between climate change and individual risks

has been difficult to convey to communities. Further, communities attempting to plan for climate

change adaptation and resilience may lack the technical skills or tailored technical assistance

(including readily available and well-developed solutions), resources and information to

assess risk, prioritize, plan, and finance critical infrastructure projects.

12

5. Programs that address other services and infrastructure to reduce the risks of climate-related

hazards, such as extreme heat or storms, may also be limited by barriers related to community

capacity, as well as insufficient data collection and communication of risks. The challenges of

extreme heat and the urban heat island effect are amplified for the elderly, infants, and young

children, homeless, mentally ill, drug users, and residents of public housing. Programs may

not effectively mitigate health-related climate risks because of a lack of integrated planning

and coordination across numerous entities, including healthcare providers and planning

authorities in local, State, and federal governments.

4.2 Key Barriers to Access and Ownership

As noted, the study team identified four categories of barriers related to accessing, using, or owning

the services and commodities listed in the Climate Act. Table 3 through Table 6 detail barriers within

each of the categories and provide examples of how they present within three different levels of

community access:

• Individual or household levels.

• Community level (such as local governments).

• Landlord or business level.

Specific service and commodity areas affected are also highlighted in Table 2 through Table 5.

9

13

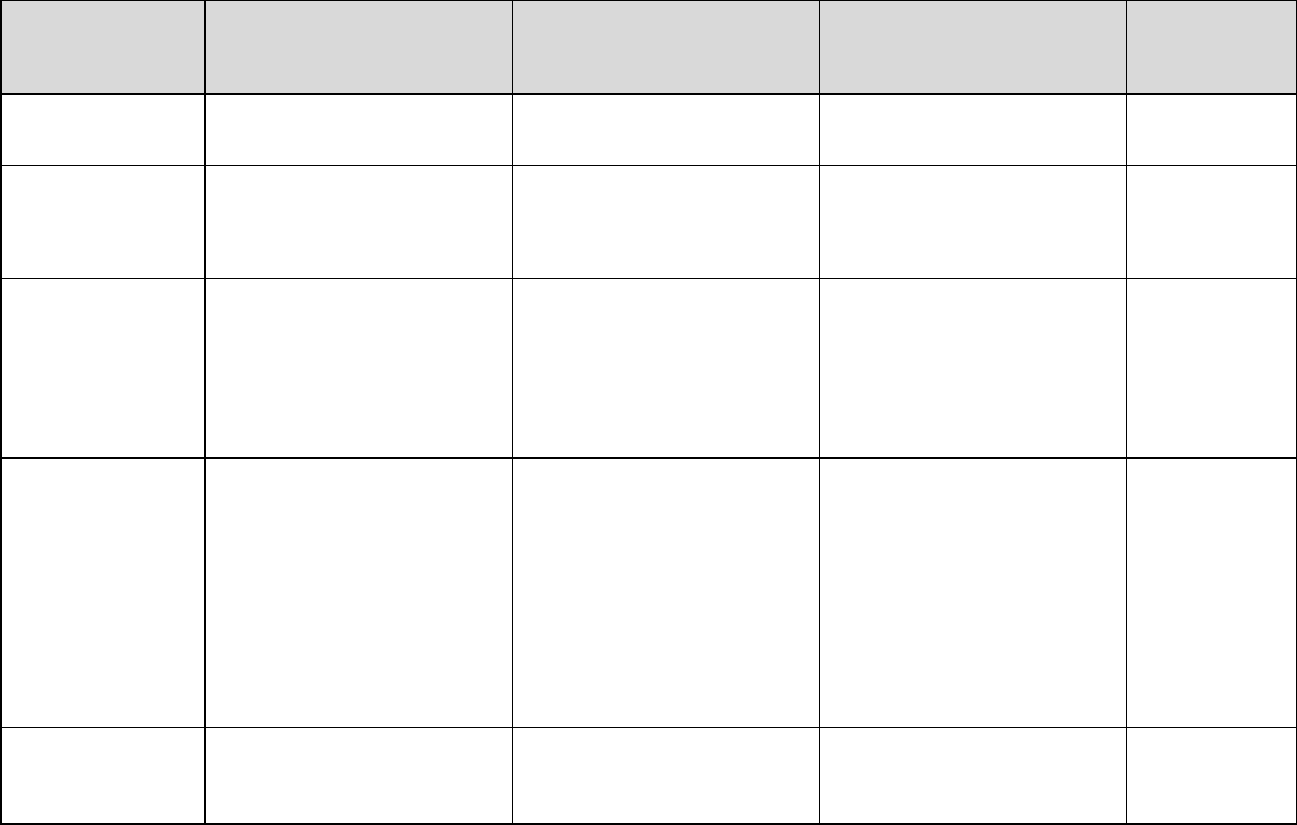

Table 2. Physical and Economic Structures and Conditions

Baseline conditions of physical or economic systems that impede access, use, or ownership of programs or solutions.

Barrier to Access

or Community

Ownership

Example Barriers: Individual

and Household Level

Example Barriers:

Community Level

(e.g., local agencies)

Example Barriers: Landlord

or Business Level

Specific

Services and

Commodities

Affected

Building stock may be

old and in disrepair.

Increased cost to upgrade, install,

or address more critical priorities

(e.g., roof repair).

Variable building conditions can

limit program reach to residents.

Increased costs to upgrade or

install; Limited financial incentive to

upgrade.

RE, Adaptation,

EE.

Multifamily/rental

structures create split

incentives.

Landlords may not invest in

upgrades, (e.g., electrification or

EV charging). Tenants have limited

ability to improve property or

accrue savings.

Limited influence with landlords;

Limited ability to ensure savings

are passed through to tenants.

Landlords have no/limited financial

incentive to upgrade if savings are

passed through to tenants.

EE, RE,

Adaptation

(buildings).

Products/services

available may not

match community

needs.

Products may not align with

household financial priorities.

New technologies may not be

practical investments (e.g., storage,

new EVs).

Variable community needs and

conditions can limit program reach

(e.g., rooftop solar or

weatherization).

Market-ready products may not be

local priority (e.g., electric vehicle

supply equipment with limited EV

drivers).

Market-ready products may not be

suited to application (e.g., EV

delivery vehicles).

All services and

commodities.

Physical infrastructure

may be insufficient.

Limited access to services (e.g.,

transportation).

Limited access to transportation

based on disabilities, gender, and

safety.

Limited infrastructural and

community resilience to damaging

events.

Limited or outdated infrastructure at

building or community level (e.g.,

drainage) makes adaptation

difficult.

High costs to upgrade outdated

infrastructure, add services (e.g.,

cooling and evacuation centers,

improved drainage).

Limited or outdated physical

infrastructure increases costs,

reduces ability to upgrade/adapt.

Local businesses have limited

resources to meet higher costs,

improve operations.

All services and

commodities.

Data/IT infrastructure

limitations can affect

community access.

Lack of internet access, Wi-Fi, and

hardware.

Limited information/technology

access.

Limited community data; Limits of

trained staff; Limited IT resources;

Impeded planning and

communications.

Limited community data or IT

infrastructure (e.g., broadband)

increases operating costs, limits

resources for other investments.

All services and

commodities,

especially RE,

Transportation.

14

Table 3. Financial and Knowledge Resources and Capacity Barriers

Insufficient resources, including financial resources, time, staffing or individuals on the household, agency, organization, or municipal level.

Barrier to Access

or Community

Ownership

Example Barriers: Individual

and Household Level

Example Barriers:

Community

Level

Example Barriers: Landlord

or Business Level

Specific

Services and

Commodities

Affected

Households and

community members

may lack access to

capital or financing

limits access.

Low/limited incomes.

Unbanked populations with limited

access to credit or cashless

options.

Limited municipal budgets.

Limited access to credit.

Limited small business capital.

Limited access to credit or

resources to improve credit access.

All services and

commodities.

Households and

community members

may lack time and

skills to find and

access programs.

Competing priorities creating

limited time to attend meetings or

learn of new options.

Not enough time to

find/plan/manage project and

submit applications.

Not enough time to

find/plan/manage projects and

programs.

Competing goals with deadlines for

funding.

Limited finances, networks.

Limited capacity for ancillary

projects.

No trained staff to plan or pursue

projects or programs.

All services and

commodities.

Lack of (or lack of

access to) information

networks (e.g.,

personal, or

professional networks)

can reduce ability to

participate.

Limited informal professional

resources/networks to provide

information about risk, benefits.

Limited knowledge resources,

professional contacts.

Limited professional

resources/networks to access

knowledge, support, strategic and

practical input.

Limited capacity and networks

professional resources/networks to

draw on for creative solutions that

aren’t “sales.”

All services and

commodities.

Communities have

limited programmatic

and information

capacity.

N/A

Limited data about population

needs.

Local social and health systems

with limited planning data and

capacity.

Limited information about workforce

availability and options related to

program or project implementation.

All services and

commodities.

Communities and

businesses face

workforce constraints.

Limited training, mobility, access to

jobs (e.g., court-involved workers

that may have a record).

Limited training capacity and

budget.

Limited workforce/contractor pool

due to lack of training opportunities,

job access (e.g., court-involved

workers).

Limited training capacity, need for

specific skill sets.

All services and

commodities.

15

Table 4. Perspectives and Information Barriers

Limited information, competing priorities and preferences, or lived experiences, including historical patterns of interaction that have eroded trust

and impede awareness of and access to programs or services.

Barrier to Access

or Community

Ownership

Example Barriers: Individual

and Household Level

Example Barriers:

Community

Level

Example Barriers: Landlord or

Business Level

Specific

Services and

Commodities

Affected

Communities may be

unaware or uncertain

of risks or needs.

Evolving information on health

effects and impacts of climate

risks may create uncertainty.

Health and risk information may

not be accessible or easy to

understand.

Limited information on impacts

of climate change on individual

health risks.

Evolving information on health

effects and impacts of climate

risks for households and

communities.

Limited documented information

about planning, infrastructure

priorities for addressing climate

vulnerabilities.

Evolving information on health

effects and impacts of climate

risks on businesses, markets,

and communities.

Lack of industry and business

leadership on addressing climate

and health risks to workers and

communities.

All services

and commodities,

focus on

adaptation, and

health and safety.

Communities may

have a lack of trust

in the program or

service provider.

Negative historical patterns of

interaction with utilities, government

agencies, landlords, potentially

due to immigrant status or identity.

Unwillingness to grant access to

homes for improvement or services.

Concern about “unproven” new

technologies.

Negative historical patterns

of interaction with utilities,

government agencies, landlords.

Complex and negative

interactions with State and

private sector.

Negative historical patterns

of interaction with utilities,

government agencies, and public.

All services

and commodities,

focus on EE,

adaptation, and

health and safety.

Communities may

perceive limited

benefits or value

of programs.

Ineffective communication of

value and lack of focus on

community priorities.

Competing priorities and lack

of clear benefit information limit

interest, including “not for me”

perspective.

Concern about “unproven”

new technologies.

Competing priorities and lack

of clear benefit information

limit interest.

Lack of focus on

community priorities.

Competing funding sources

and programs may affect

prioritization.

Concern about “unproven”

new technologies.

Competing priorities and lack of

clear benefit information limit

interest; payback period too long.

Ineffective communication of value,

limited trust in new technologies.

All services

and commodities.

16

Table 5. Programmatic Design and Implementation Barriers

Data and knowledge gaps related to lack of alignment between agencies and program design constraints.

Barrier to Access

or Community

Ownership

Example Barriers: Individual

and Household Level

Example Barriers:

Community

Level

Example Barriers: Landlord or

Business Level

Specific

Services and

Commodities

Affected

Lack of baseline

or benchmarking

and impact

assessment data.

Misaligned or conflicting program

offerings, limited access due

to changes in households or

missing information.

Lack of information about where

needs are across programs and how

well programs would meet them.

Misaligned or conflicting

program offerings, limited access

to meet needs, limited

community application.

Lack of information about where

needs are across programs

and how well programs would

meet them.

Programs not consistent with priorities.

Lack of information about business

priorities, processes, and needs.

All services and

commodities,

focus on EE.

Program not well

designed for

community members.

Limited focus to date on climate-

vulnerable and heat-vulnerable areas.

Historically focused on single-family

homes and homeowners with limited

offerings for multifamily renters.

Limited focus to date on climate-

vulnerable and heat-vulnerable

areas and programming.

Limited focus on multifamily renters.

Limited attention on climate-vulnerable

and heat-vulnerable areas, limited

options for C&I.

All services and

commodities.

Program eligibility

constraints and

application requirements

may eliminate

certain communities.

Programs requiring home ownership

or new technology purchase.

Income eligibility varies and difficult

to understand/navigate, limited

access for renters, technologies

require capital.

Programs requiring home ownership

or new technology purchase.

Multiple programs difficult to

optimize, variable eligibility.

Competitive grant structures favor

communities and organizations

with grant-writing capacity

and experience.

Programs requiring building ownership

or new technology purchase.

Loan-based programs not accessible

to small, cash-based businesses.

Application requirements favor

firms with resources.

All services and

commodities.

Program resources

may be insufficient

or inconsistent.

Program scope, timeframes

too limited to address complex

issues and widespread need.

Program scope, timeframes too

limited to address complex issues

and widespread need; short time

horizons for funding do not align

with planning.

Program scope, timeframes too

limited to address business financing

cycles and project scopes.

All services and

commodities.

Programs may lack

sufficient coordination.

Burdensome applications,

conflicting eligibility.

Lack of coordination across

governments (e.g., city or town

coordination with county or State)

may cause confusion.

Burdensome applications,

conflicting eligibility; local

alignment of programs requires

effort, difficult to optimize, schedules

difficult to implement.

Some agencies may lack authority

to participate at community level.

Burdensome applications,

conflicting eligibility.

All services and

commodities.

Program outreach

may be insufficient

or misaligned.

Lack of awareness of programs and

services because information is not

provided in the best channel,

source, language, or format.

Communities that could benefit

from programs/services aren’t

aware; programs have difficulty

communicating to residents.

Lack of awareness of programs and

services because information is not

provided in the best channel, source,

language, or format.

All services

and commodities.

17

5 Recommendations and Opportunities Overview

This section provides an overview of the report recommendations, including describing the structure of

recommendations and opportunities.

5.1 Overview and Background

This section details recommendations and opportunities identified through the activities described in

the report. Note that the recommendations do not address the significant and important work that will

be necessary to put them into practice, which is further discussed in section 6. Some examples of

remaining work and how they relate to the recommendations are highlighted below:

• Identifying and addressing policy implications. Some recommendations may have

larger policy repercussions. For example, integrating communities in program design is

an endeavor that takes additional time and money and could imply substantial changes to

established processes.

• Finding and gaining support for additional funding and staffing. Several recommendations

require local and State agencies to take a more active role within communities during planning

processes and to provide support to identify and address climate hazards. In many cases,

agencies or other organizations may not have the requisite budget, authority, skills, or

staffing to do this.

• Conducting a full-stakeholder review and feasibility assessment. Most, if not all,

recommendations require numerous parties to collaborate and determine a path forward

to implementation. Implementing agencies must establish organizational structures, develop

new and existing relationships, and build trust to facilitate this stakeholder collaboration.

The study team also recognizes that some of the recommendations identified may already be in

practice within certain communities or programs and has included some examples.

5.2 Recommendations

The study team makes eight high-level recommendations that are organized under three key themes:

• Recommendation Theme 1: Ensure processes are inclusive.

• Recommendation Theme 2: Streamline program access.

• Recommendation Theme 3: Address emerging issues.

18

For this report, a “recommendation” is considered a high-level principle to increase access and

ownership in disadvantaged communities, while an “opportunity” is a strategy or tactic that supports

the implementation of the related recommendation. Table 6 below summarizes these recommendations,

as well as the opportunities identified to implement them.

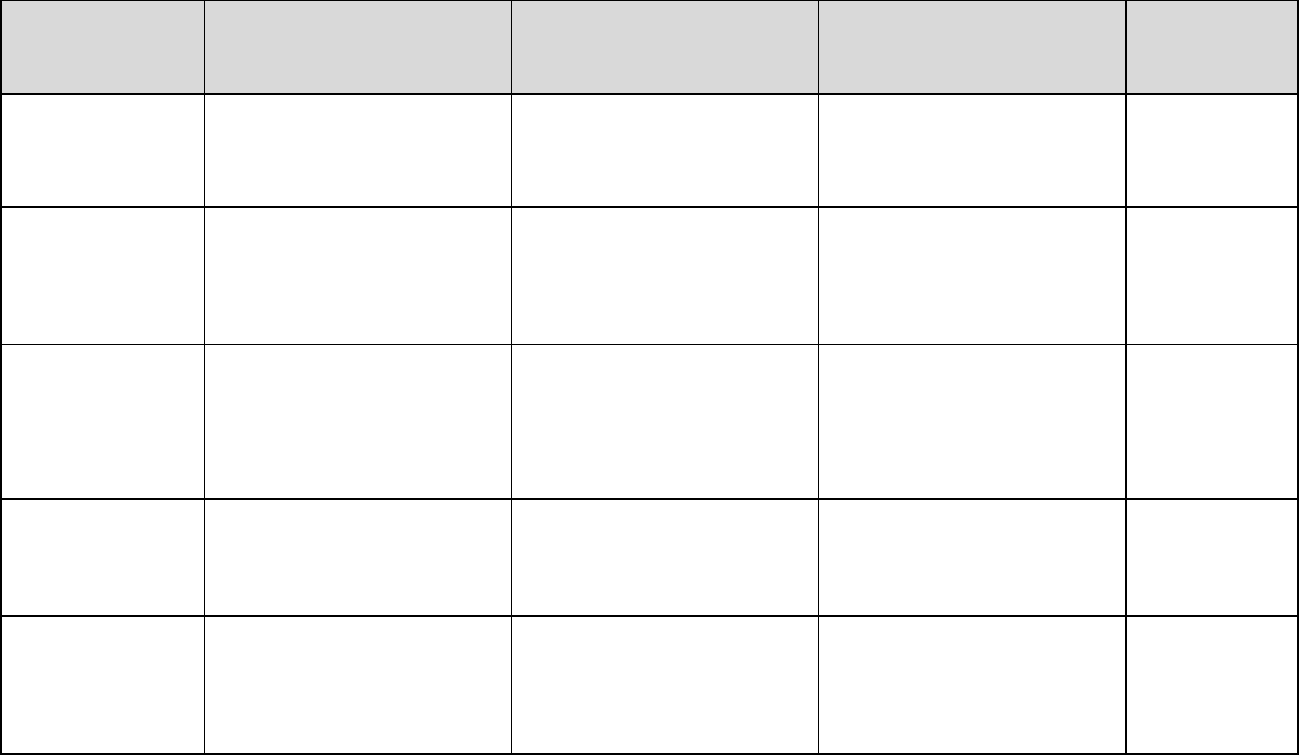

Table 6. Summary of Recommendations and Opportunities

Recommendation Related Opportunities

Recommendation Theme 1: Ensure Processes are Inclusive

1. Co-design programs

or projects with and

for communities.

1a. Staff agencies and funding programs to implement co-design processes

with communities.

1b. Build trust by dedicating time and resources to develop relationships

with communities.

1c. Co-design with and for the most vulnerable New Yorkers.

1d. Develop wealth-building and asset-building options or pathways.

2. Provide meaningful

opportunities for

public input in

government

processes and

proceedings.

2a. Revisit public outreach and engagement protocols and practices with communities

to bring more people into conversations earlier and show them how their input is

being addressed.

2b. Track and assess participation in public processes.

2c. Continue seeking and supporting community groups and representatives

in public processes.

3. Work across

intersecting

challenges and

interests to address

needs holistically.

3a. Recognize and address intersecting barriers in accessing programs and services.

3b. Describe the benefits of clean energy, transportation, environmental and adaptation

projects on several dimensions, with cultural awareness.

3c. Actively seek and recruit community partners for communication and program

or service facilitation needs.

3d. Expand intermunicipal and regional collaboration.

3e. Include a range of stakeholders with different roles and areas of expertise.

3f. Update codes, rules, and policies that currently limit or prevent climate

change solutions.

3g. Recognize and address the compounded effects of systemic racism

and environmental and climate injustice within climate plans.

Recommendation Theme 2: Streamline Program Access

4. Transition to

program models that

require little or no

effort to participate

and benefit.

4a. Automatically enroll people into programs where possible.

4b. Automatically refer eligible people and businesses between programs,

with follow-through.

4c. Directly award grants to communities instead of requiring lengthy and competitive

application processes, to the extent consistent with relevant legal requirements.

5. Establish people-

centered policies,

programs, and

funding across local,

State, and federal

governments.

5a. Expand eligibility where feasible to maximize impact and coordinate

between programs.

5b. Provide clearer participation roadmaps and pathways for community members.

5c. Offer more direct access to resources, information, data, and knowledge.

5d. Assess opportunities to merge, combine, or closely coordinate related programs

across State agencies, to the extent consistent with legal requirements.

5e. Review and reemphasize the State’s role as the connector between federal

and local programs and services and across different market actors.

19

Table 6 continued

Recommendation Related Opportunities

6. Find and support

resource-

constrained local

governments.

6a. Identify the most vulnerable communities and craft a set of services that

are most frequently needed.

6b. Provide digestible data and information to help local governments identify

climate risks and potential adaptation strategies.

6c. Bring education and training to local governments so they are prepared to receive

funding and understand what resources are available.

Recommendation Theme 3: Address Emerging Issues

7. Mobilize citizen

participation and

action.

7a. Develop channels and tools for people to report local concerns.

7b. Support people and neighborhoods in providing feedback about climate issues

that affect them.

7c. Facilitate ways for community members to contact and support each other

in emergencies.

7d. Find and support local champions.

8. Improve housing

conditions and

adherence to local

building codes.

8a. Address building integrity from a health and safety perspective.

8b. Continue to improve housing and energy upgrade incentives and financing for

building owners serving disadvantaged community members.

8c. Address the possibility of climate-related displacement or relocation early, and

work with communities to develop questions and options.

8d. Institute anti-displacement, relocation, or managed retreat policy that considers social,

cultural, and historical context in addition to infrastructure and natural environment.

8e. Increase building health and safety and energy code enforcement efforts

and partnerships.

8f. Bring energy code education and training to frontline contractors.

The fol

lowing sections further describe the recommendations and opportunities. Recommendations

are organized by the three key themes described above: ensure processes are inclusive, streamline

program access, and address emerging issues. Opportunities (or tactics) are grouped according to

the target audiences, differentiating among opportunities to work with individuals, households, or

businesses; to increase access and ownership; and opportunities to work at the community level

with community organizations, groups, or local government to increase access and ownership.

Where available, examples of the opportunities are provided, identifying the relevant service or

commodity area.

10

,

11

In most cases the recommendations do not name a specific responsible party or actor, as the same

opportunities may exist at the State, regional and local levels, and could be implemented by government

entities and nonprofits alike. Per above, a next step toward implementing this report may be a baseline

or gap analysis to understand current actions and processes, and the agencies or other entities that may

be best positioned to implement the recommendations.

20

Recommendation Theme 1: Ensure Processes are Inclusive

Recommendation 1: Co-Design Programs

or Projects with and for Communities

Involve community members and relevant community stakeholders

as programs or projects are designed, inviting participation at an early

stage in the process to ensure that the outcomes reflect the concerns

and needs of the community. The reason to encourage participation

of community members is that residents of disadvantaged communities

are often excluded from planning and other processes that impact their

communities. Rectifying these historical harms requires transforming

typical government processes and inviting participation from

stakeholders and residents who can fully explore the needs, concerns,

resources, and attitudes of a community. Early participation can also

unlock new synergies for effective and impactful program delivery.

Opportunities to work with individuals, households, or businesses:

1a. Staff agencies and fund programs to implement co-design processes with communities.

• Dedicate agency staff and funding to help residents of communities organize (or work

with trusted community organizations) to ensure they have a role in the co-design process

and that their priorities and needs are reflected in the programs or projects that impact them.

• Hire a diverse and bilingual staff who can engage with community members based on shared

experiences in the language they prefer and ensure that non-English speaking individuals

or those with limited English proficiency can participate in the co-design process.

• Ensure that agencies develop capacities to support co-design processes with

multi-disciplinary research and inquiry and diverse forms of expertise.

• Continue developing emergency response plans with input from public housing residents.

• Provide fair compensation for organizations and individuals to contribute to the

co-design process.

Effectively collaborating with communities will require new and inclusive processes. Such changes

will require staff time and effort and may require additional time to build relationships with community

stakeholders. Dedicated funding streams will assure these programs benefit from consistent support.

“Community members

and leaders need to be

involved in this discussion;

government agencies can’t be

left to their own silos to come

up with these plans, they are

not attuned to the real needs

of communities and have blind

spots. A comprehensive plan

that’s created with the input

of community members and

[organizations] that represent

front

line communities [is

what’s needed].”

- Focus Group Participant

21

Example Program: New York State has established through Executive Order a Language Access

Policy that directs each state agency that provides direct public services to offer interpretation services

to individuals in their primary language. These agencies are also required to translate vital documents,

including public documents such as forms, in the ten most common non-English language spoken by

Limited English Proficiency individuals in the State of New York. The agencies are also required to