A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving

Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to

Serve Latinxs Equitably

2 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

Introduction

Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs), which are broadly

defined as non-profit postsecondary institutions enroll-

ing a minimum of 25% Latinx undergraduates, currently

constitute 19% of all colleges and universities across the

United States and Puerto Rico. Historically, most HSIs

have been institutions with open and inclusive admis-

sions policies. Yet, a growing number of research 1 (R1)

universities, which are better known for their selective

admissions processes and historical underrepresenta-

tion of Latinx students, are now meeting the enrollment

thresholds for HSI designation. Despite increasing

Latinx undergraduate enrollments, Latinx graduate

students, faculty, staff and administrative leadership at

these institutions remain severely underrepresented.

This pattern is concerning given that research 1 universi-

ties play a critical role in producing the next generation

of researchers and professionals. Recognizing this

issue, national efforts involving R1 HSIs are aiming to

boost Latinx graduate and faculty representation at

these institutions. Yet, it remains uncertain to what extent

these R1 HSIs are changing their structures to achieve

these objectives, which points to a critical gap in educa-

tional research and policy that needs to be addressed.

As the public research university system in the state with

the largest Latinx population in the nation, the University

of California (UC) is similarly reflecting these broader

enrollment trends. UC educates an increasingly diverse

student body, including many historically underserved

racial minorities and those who are first-generation and

from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Much of this

diversification at the UC is due to increased enrollment of

Latinx undergraduate students. Five of the nine under-

graduate campuses now meet HSI eligibility criteria, while

the remaining campuses are on paths to meet the 25%

undergraduate enrollment threshold soon. As these

institutions, which were historically predominantly attend-

ed by white students, now educate a significantly more

racially diverse student population, it is essential to

employ culturally responsive and asset-based approaches

in serving this multicultural, multilingual, and first-gener-

ation critical mass of students. Substantial efforts are

required to transform the entire UC system into a reflec-

tion of the state’s population and to establish structures

and environments indicative of servingness. This presents

ample opportunities for UC to actively engage in the

necessary process of institutional transformation,

ensuring optimal support for its students and remaining

the world’s leading research public university system.

Purpose of the Report

This report explores the concept of “servingness” within

the University of California (UC) system, which is on its

way to becoming a collection of fully-fledged Hispan-

ic-Serving Research 1 Institutions (HSRIs). This work

stems from a UCOP Office of the Provost planning grant

under the cross-campus leadership of Drs. Marcela G.

Cuellar (Davis), Frances Contreras (Irvine), and Juan

Poblete (Santa Cruz). The report begins with an intro-

ductory section, outlining the increasing presence of

HSRIs across higher education overall and, more

specifically, within the UC system. Following this, three

papers explore how servingess can be conceptualized

within UC, given existing inequities in outcomes. Finally,

the report concludes by offering a series of recommen-

dations aimed at establishing frameworks, structures,

and environments that truly embody the notion of serv-

ingness throughout the entire UC system.

Paper Summaries

In the first paper, Dr. Juan Poblete proposes that the

arrival of Latinx students into the University of California

marks a progressive development, democratizing

access and potentially paving the way for greater educa-

tional equity within the state. However, this development

takes place against the backdrop of substantial student

enrollment growth and a series of regressive dynamics

that have so far limited the positive social impact of that

access. These dynamics encompass factors such as

reduced per-student spending, decreased state funding

for public education, and the imposition of tuition increas-

es that place a burden on students’ families. Within this

context, two contradictory dynamics become evident: the

expansion of public education’s reach and the concur-

rent privatization of the concept of public education. The

attainment of Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) status

across the University of California system presents a

notable opportunity. By reconsidering the meaning of

“servingness,” this status can potentially initiate a shift

Executive Summary

3 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

back towards perceiving public education as an inher-

ently public good. This perspective views public educa-

tion as a collective investment that we undertake to

foster educational equity, uphold social justice, and forge

a more promising future for all residents in the state.

In the second paper, Dr. Marcela G. Cuellar and Mariana

Carrola (a UC Davis PhD student) present the notion

that within HSRIs there is a need to formulate a theoreti-

cal framework for the concept of servingness, given the

unique institutional characteristics shared by HSRIs and

key constituents that are understudied, such as graduate

students. By conducting a critical literature review of

existing research on HSRIs, the paper synthesizes key

themes, identifies gaps in knowledge, and begins to

contextualize the extent to which institutional transforma-

tion is occurring to intentionally serve Latinx communi-

ties at these institutions. The paper concludes with a

series of recommendations that focus on how research

can play a role in informing and guiding the transforma-

tion of UC institutional cultures and practices. This

approach aims to foster greater responsiveness while

simultaneously advancing scholarship on HSRIs. Addi-

tionally, these recommendations are intended to guide

the overarching process of institutional transformation

across higher education to better address the needs of

underrepresented communities.

In the final paper, Dr. Frances Contreras examines UC

data systems. This paper introduces a novel proposal for

a revamped data infrastructure that can effectively

assess servingness within the UC system. This section

provides an overview of the key data points, surveys, and

annual reporting mechanisms within the UC system as a

whole and across its individual campuses. These tools

have the potential to be harnessed for the purpose of

assessing, analyzing, and developing solutions-oriented

approaches to better serve and respond to the needs of

its Latinx students. Through a critical analysis of key

annual reports and pertinent data, this paper emphasizes

the potential value of such information in facilitating

rigorous self-assessment for campuses. This evaluation

pertains to the outcomes and experiences of students,

faculty, and staff while attending or working within the

UC system. Recognizing that UC’s aspiration to grow its

own pool of future academicians, top managers and

leaders, and to support innovation, it becomes evident

that adopting a systemic approach to assessing Latinx

progress for all concerned parties is imperative to the UC

system’s domestic and global prominence. This endeavor

serves as a cornerstone for bolstering the standing of

the UC system, both on a national and international

level, by ensuring that the advancement and welfare of

all those involved remain central to its mission.

Recommendations

The final section offers several recommendations for

enacting a 21st century vision for creating a HSRI sys-

tem. These recommendations represent a multifaceted

approach to guide UC in these endeavors.

Shared HSRI Vision

• Establish a shared systemwide HSRI definition.

Defining and enacting an HSI identity varies across

institutions and intersects with other organizational

identities, such as R1 status, at UC. UC should estab-

lish a shared HSRI definition for the system and its

individual campuses.

• Create actionable goals in line with HSRI vision.

UC should outline actionable goals that can be pursued

across the system and all UC campuses.

• Develop a UC HSI Dashboard and produce annual

HSRI reports. UC should develop an HSI dashboard

monitoring progress and produce annual HSI reports

for each campus for the purposes of monitoring

progress.

• Convene a systemwide HSRI equity summit. UC

should continue to invest in the UC-HSI Initiative,

which has successfully convened campus leaders in

several annual HSI retreats since 2017.

Latinx Student Supports

• Advance undergraduate student success beyond

enrolling and graduating Latinx students. The 2030

UC Dashboard laudably aims to increase graduation

rates across the system and eliminate equity gaps

among underserved student groups, including Latinx

students. UC must expand its perspective on success

beyond these important measures to achieve greater

equity among Latinx students. Key indicators of

success to consider are fostering graduate school

access, enhancing career opportunities, civic engage-

ment, and more.

4 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

• Increase student support. By implementing changes

in existing opportunities/programs that take into

consideration a growing Latinx student population and

the engagement of this student population in academ-

ic/career development programs, UC can more

intentionally support Latinx undergraduate and gradu-

ate students.

• Reduce student debt. Reducing the prospect of

student debt would encourage enrollments and ensure

that low-income students are working fewer hours and

are able to focus on their academic coursework.

• Direct more support and resources to Latinx

graduate students. UC should direct more support

and resources to support the academic and professional

development of Latinx graduate students.

Latinx Faculty and Staff Supports

• Hire and retain more Latinx faculty. The UC 2030

dashboard boldly aims to invest in faculty hiring and

research. To achieve this goal and align with an HSRI

vision, UC must intentionally hire and retain more

Latinx faculty. This commitment must be championed

at all levels—systemwide, at the campus level, and

within individual departments.

• Establish a faculty diversity task force. A faculty

diversity task force would be charged with critically

analyzing faculty diversity, retention, and progression

through the tenure track ranks.

• Establish a staff diversity task force. A staff diversity

task force would be charged with analyzing staff

composition across campuses, with close attention to

mobility within UC.

Research Capacity

• Provide funding for an HSRI research center. As

more research institutions become HSIs, the need to

understand these unique contexts will require research

and opportunities for cross-campus collaborations. As

UC campuses comprise almost 20% of existing HSRIs

in the nation, the system is further poised to lead in

research efforts on this institutional type. Funding for

the establishment of an HSRI Research Center will

create an infrastructure to support this type of research.

• Incentivize research practice partnerships rooted

in the Latinx community and within Latinx-serving

institutions. It’s imperative to understand how UC’s

land-grant mission is intertwined with the identities of

Indigenous and historically underserved communities.

Specific to the HSRI identity and this report recommen-

dation, providing incentives and opportunities for faculty

and researchers to engage in more community-engaged

efforts will further advance the historic research and

land-grant mission of the system.

Data Infrastructure

• Invest in HSRI data infrastructure for increased

accountability and agency. UC has made great

strides in creating dashboards that provide actionable

data. Building on these resources, UC should also

develop HSRI-focused data resources.

• Establish a systemwide HSRI data task force. An

HSRI data task force would convene to assess the

status of UC across various metrics for its key partners

and collaborators (faculty, staff, students, partnership

program participants).

• Articulate more structured and standardized

measures for evaluating HSRIs. These measures

should consider institutions, their programs, and

interventions meant to support the retention and

success of Latinx undergraduate, graduate students,

and faculty.

• Hire institutional research (IR) staff at UCOP for

HSI analysis.

At this critical juncture, the UC system also has the

potential to emerge as the foremost HSRI system in the

nation, provided it rises to the challenge of serving its

Latinx students equitably. With several HSRIs, the UC

system assumes a crucial role and responsibility in

spearheading the development of new theoretical

frameworks, informing programmatic interventions, and

setting exemplary models and methods that can guide

the broader national postsecondary education landscape

as it endeavors to serve a growing Latinx population. By

undertaking these efforts, the UC system can uphold

and expand upon its legacy of excellence which has

been characteristic of the system since its inception.

5 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

Over the past two decades, the University of California

(UC) has progressed in its advancement of greater

inclusion and equity for historically underserved stu-

dents, including Latinx students. In fall 2020, 25% of the

UC system’s undergraduates were Latinx, compared to

12.3% in fall 2000 (UCOP, nd). These enrollments also

include many who are first-generation and from low

socioeconomic backgrounds. This demographic compo-

sition has led to the attainment of federal Hispanic-Serv-

ing Institution (HSI) designation for several UC campuses.

HSIs are broadly defined as non-profit postsecondary

institutions enrolling at least 25% Latinx undergraduates.

Five undergraduate campuses have obtained this

designation, and the remaining four campuses are on

the path to attaining this status in the near future. The

diversification of the UC system means that these

selective institutions that were predominantly white are

now educating much more diverse student populations,

which calls for more culturally responsive and as-

set-based approaches to serving this multicultural,

multilingual, first-generation critical mass of students.

Despite these strides, inequitable representation within

key positions and specific educational outcomes continue

to plague the UC system. For example, the composition

of the undergraduate student body is still not reflective of

California’s growing Latinx population of high school

graduates (Paredes et al., 2021). Remarkably, nearly

53% of the state’s high school graduates are now Latinx,

and 45% have met the A-G requirements, enabling them

to qualify for admission to the California State University

(CSU) or UC (UCLA HSI Task Force, 2022). Similarly,

while diversity among graduate students and ladder-rank

faculty has increased, the representation of Latinxs in

these influential roles continues to substantially lag

behind their undergraduate enrollment (Paredes et al.,

2021). Inequities in graduation rates between Latinx

students and other student groups also persist. The HSI

designation invites campuses to engage in the necessary

institutional transformation to achieve more equitable

access and outcomes for Latinx students (Santiago,

2012). The challenge therefore for the UC system is to

ensure that all campuses are critically reflecting on the

degree to which they are Latinx responsive, relevant,

and serving (Contreras, 2019).

As UC sets out to address these challenges, there is an

opportunity for the system to lead as a national model

for a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI)

system. Given the critical role of research-1 (R1) institu-

tions in producing the next generation of researchers

and professionals, a few national initiatives are now

catalyzing the capacity of HSIs that also hold R1 status.

These initiatives aim to advance the progress of Latinx

graduate students and faculty. The National Alliance of

Hispanic-Serving Research Universities, for instance,

has set bold goals of doubling the number of Latinx

graduate students and increasing Latinx faculty by 2030

among the 21 HSIs that also hold R1 status (Alliance of

Hispanic Serving Research Universities, 2022). With UC

representing 19% of all HSRIs, it has the potential to

emerge as a leader not only among these institutions but

across broader national systems. The system has taken

a proactive stance by initiating UC-HSI Initiative—a

platform designed to connect leaders across campuses

and to strengthen the capacity of UC to serve an in-

creasingly diverse population (Paredes et al., 2021).

Exploring the various avenues through which UC can

augment its servingness capacity will empower the

institution to fully leverage its potential as a trailblazing

Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) system.

Servingness at HSIs

While most HSIs lack a historical mission to serve Latinx

students, scholars have theorized ways through which

these institutions can more effectively serve Latinx

students. This notion is encapsulated in a concept called

servingness (Garcia et al., 2019). Servingness is a

multidimensional construct that considers multiple forces

shaping HSIs and their ability to support Latinx students.

External to an institution, federal and state policy as well

as institutional governing boards influence HSIs and

servingness. Internally, servingness is embodied through

various structures, such as the mission and values of an

institution, HSI grants, the cultural relevance of curricula,

engagement with the Latinx community, and the compo-

sitional diversity of students, staff, faculty, and adminis-

trators. Consequently, these factors contribute to the

formation of environments that Latinx students encoun-

ter within HSIs, which can hold both validating and

racialized characteristics. The measurement of serving-

Introduction

6 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

ness can also encompass an array of academic and

non-academic outcomes.

Each of these elements of servingness are further

shaped by larger systems of oppression, including

settler colonialism and white supremacy (Garcia, 2018;

Garcia et al., 2019). These systems of oppression are

particularly entrenched in research universities across

various structures, including UC. Being California’s

land-grant institution, UC is deeply intertwined with the

history of settler colonialism, as these institutions were

established through the dispossession of Native lands.

(Nash, 2019). White supremacy is further embedded in

the design and culture of most institutions of higher

education. Cabrera et al. (2017) describe how definitions

of meritocracy are always informed by a white racial

frame and consistently evolve when intended outcomes

are no longer produced. Notions of meritocracy, for

example, are shaped by and reinforced by whiteness in

certain higher education cultural practices, such as

admissions processes (Cabrera et al., 2017).

Within UC, admissions and access for racially minori-

tized individuals have been hotly contested issues.

Twenty five years ago, California residents voted to ban

affirmative action in state institutions with the passage of

Proposition 209, which eliminated the consideration of

race in UC admissions processes. The elimination of

affirmative action immediately reduced the representa-

tion of students of color within UC. Lasting impacts are

also visible in hostile campus racial climates and under-

representation of faculty of color on these campuses over

time (Ledesma, 2019). Attempts to repeal the affirmative

action ban through recent ballot measures, such as

Proposition 16 in 2020, also failed. Though strides have

been taken to dismantle certain structural barriers, like

the recent elimination of standardized exam prerequi-

sites for admissions, there is still a significant amount of

work ahead to reshape the UC system in a way that

aligns with California’s demographics and actively

nurtures Latinx faculty, staff, and students. Comparable

obstacles are anticipated in other HSRIs, particularly

following the Supreme Court’s ruling against affirmative

action practices in higher education.

Purpose of This Report and Structure

This report will explore the concept of servingness

(Garcia et al., 2019) specifically within R1 universities

with a focus on the University of California (UC) system.

This work stems from a planning grant provided by the

UCOP Office of the Provost starting on July 1, 2021.

Under the cross-campus leadership of Drs. Marcela G.

Cuellar (Davis), Frances Contreras (Irvine), and Juan

Poblete (Santa Cruz), the planning grant aimed to:

1.

Engage in deep, conceptual, and analytical work to

fully understand the theoretical and empirical landscape

for HSRIs.

2.

Conduct a critical assessment of the UC system’s

ability to measure HSRI outcomes for all partners and

collaborators (students, staff and faculty).

3.

Provide recommendations for greater data transpar-

ency and access by suggesting a framework and

infrastructure for data mapping and analytics.

4.

Develop a blueprint for the UC system as it moves

toward becoming a premier Hispanic-Serving Re-

search system in the nation.

Three papers in this report address these activities and

deliverables as part of the grant:

1. Conceptualizing HSRI at UC

1.1. Develop a historical overview of Latinx arrival to the

system.

1.2. Examine investment and disinvestment of resources

in the past 15 years.

1.3. Develop a literature review of existing HSI scholar-

ship and identify gaps.

1.4.

Generate a blueprint for a 21st Century Vision for

UC to become the premier HSRI system in the nation.

7 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

2. Data Mapping

2.1. Examine the landscape of existing data sources

that can be used for assessing UC’s current state of

“servingness” and its possibilities and challenges for

HSRIs.

2.2. Propose how these sources can be aggregated and

presented as an HSI data module that is more acces-

sible for research, policy and practice.

In the first paper, Dr. Juan Poblete examines the socio-

historical developments leading to the formation of UC as

a HSRI system and calls for a recommitment to the

public good as integral to servingness. Next, Dr. Marcela

G. Cuellar and Mariana Carrola critically analyze litera-

ture on HSRIs and propose areas for future research

that can guide transformation towards servingness

within UC. Lastly, Dr. Frances Contreras proposes HSI

metrics that would enable UC campuses to monitor

progress in becoming more Latinx responsive and to

fulfill the concept of servingness. Collectively, these

three papers advance ideas on how servingess can be

conceptualized and enacted at UC. The report con-

cludes with recommendations that serve as a blueprint

for how UC can set an example in its efforts to become a

leading HSRI system in the nation.

8 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

a. I would like to thank my colleagues Marcela Cuellar and Frances Contreras for their collaboration in this project. Likewise, my thanks to Catherine Coo-

per for invaluable feedback and Mariana Carrola Flores for some of the UC data research.

The Arrival of Latinx Students to the University of California

System and the Future of California

a

“ Futures are coordination devices. They are central to the creation and sustenance of political projects and

material practices. They act as programs around which people, tools, finances, and organizations are

mobilized. The process of attending to futures forms an arena in which groups can construct a collabora-

tive agency where none existed before.” (Facer and Newfield, 79)

A

bstract: This paper proposes that the arrival of

Latinx students to the University of California—a

progressive development democratizing access and

potentially making possible higher levels of educational

equity in the state—has occurred in the context of

sizable student enrollment growth and a series of

regressive dynamics that have so far limited the positive

social effect of that access—among them: lower

per-student spending, diminished state funding for public

education, and tuition increases burdening students’

families. More generally, the pipeline guiding Latin@

Californians from P–20 (preschool through graduate and

professional school) has been affected by increasing

levels of demand throughout the pipeline and decreasing

resources to address the needs and aspirations of a

significantly diversified population at the college level.

Two contradictory dynamics are manifest here: an

expansion of the reach of public education and the

privatization of the concept of public education. Hispan-

ic-Serving Institution status (HSI) across the University

of California system is a great opportunity, through

rethinking the meaning of ‘servingness,’ to begin a return

to an understanding of public education as fundamentally

a public good, i.e., one on which we collectively invest

because we strive for educational equity, social justice

and a better future for all in the state. Moreover, the UC

system—including, as of 2021, five of the 17 Hispanic

Serving Research Institutions (HSRI) listed among the

more than 560 HSIs nationally, many of which are

two-year community colleges)—is destined to play a key

role in the evolution of the meaning and possibilities of

servingness in the Hispanic-Serving Institution category,

as the work of educational inclusion meets the mission

of high levels of research production.

During the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries,

three long-term processes changed the University of

California. The first involved the demographic changes

in the state of California in the last 50 years, including

the ascent of Latinx populations to the largest ethnoracial

group in the state and their increased eligibility for and

access to the UC system. The second was a significant

defunding of public education. The third was the result-

ing relative privatization of funding for attendance to

public universities, as more and more of the burden of

covering the costs of attendance was shifted to students’

families through loans to pay for tuition. This paper

examines these three processes, situates them within

historical patterns of inclusion and exclusion, and explores

the implications, difficulties, and opportunities arising

from their convergence in the contemporary landscape.

The aim is to provide context for what the paper terms

Dr. Juan Poblete, Professor, University of California, Santa Cruz

9 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

as the “Arrival of Latinx Students to the University of

California” and the consequent evolution of the UC

system into the leading Hispanic-Serving Research

system in the country.

Six quick facts illustrate this complex and

contradictory situation:

• Between 1970 and 2020, California’s population

doubled from 20 to 39.5 million, tripling its Hispanic

component;

• Between 1992 and 2019, undergraduate student

enrollment at the UC grew from 125,000 to 226,000

(approximately 80%);

• Between 1990 and 2009, per-student state funding for

UC students (adjusted for inflation) decreased by more

than 50%. In the late 1980s, state funding was as high

as $25,000 per student and fell to about $10,000 by

2015 (Johnson et al., 2014);

• Today, Pell Grants are the federal government’s main

tool for helping low-income students pay for college. In

1980, Pell Grants covered more than 75% of the cost

to attend a 4-year public university; the current maxi-

mum award covers just 28%

1

;

• In the last 40 years, nationally, per capita student debt

has skyrocketed,

• Five of the UC system’s nine undergraduate teaching

campuses are Hispanic-Serving Institutions (at least

25% of their undergraduate students are Latinx) and

1 Source: www.universityofcalifornia.edu/double-the-pell

2 Source: Public Policy Institute of California, www.ppic.org/publication/californias-population

the other four are emerging HSIs, approaching that

status in the next few years.

The growth of California’s Latinx population in the last

fifty years is illustrated in Figure 1.

2

Since 1970, California’s Latinx population has tripled. This

transformation has sparked substantial inquiries into how

a prominent public education system like the University

of California, a public Land-Grant institution, can uphold

its dedication to the public and its mission of fostering

knowledge, prosperity, and societal welfare. What could

it mean for UC to become a Hispanic-Serving public

education system? How should we interpret the essence

of “servingness” embedded in this designation? This

paper explores a range of implications stemming from

this demographic and societal shift. The convergence of

three enduring processes—demographic shifts (leading

to the Latinx population becoming the largest ethnoracial

group in the state and to increased UC enrollment),

substantial disinvestment in public education, and the

partial privatization of funding for public higher educa-

tion—coinciding with the arrival of Latinx students to the

University of California, needs to be examined within the

backdrop of four broader historical trends that have

historically influenced the status of Hispanics in the state

and shaped their historically formed pattern of inclusion

with elements of exclusion.

1970

76

67

19

13

7

8

Share of population (%)

1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

White Latino Asian or Pacific Islander Black

Two or more races

Native American or Alaska Native

3

5

6

5

58

47

40

35

25

32

38

39

15

13

11

9

7

6

Source: Census Bureau decennial counts

Figure 1: California’s Population is Increasingly Diverse

10 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

Coloniality, according to Peruvian sociologist Aníbal

Quijano (2008), refers to the productive structure of

power resulting from what we now term as the continen-

tal expansion in the Americas of colonialism with the

accompanying racialization of labor. Coloniality not only

solidified the identity of the colonizing subjects (White

Europeans) but also defined the identity of the colonized

individuals (non-European, non-White others), categoriz-

ing them as subjects of political, economic, and cultural

exploitation at the hands of the former. Across the

Americas, this conquest was realized by instituting a

system that intertwined labor and racial difference at the

economic level, as well as knowledge and subjectivity at

the social level. As a result, the labor of some (Whites)

was deemed worthy of a full salary while the labor of

others (enslaved Africans and Native Americans, and

later Mexican Americans in the USA) could be minimally

remunerated or even exploited without compensation. A

Eurocentric ideology, dichotomizing concepts like

civilization/barbarism and modern/pre- or nonmodern

societies, further shaped the narrative concerning the

value of knowledge and the establishment of hierarchi-

cally ordered and racialized subjectivities and laborers

(Quijano 2008).

Proletarianization is the racialization-based process

through which California-based Mexican citizens who

were entitled to American citizenship due to the Treaty

of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) experienced gradual

dispossession, whether de jure or de facto, of those

entitlements and their ownership and property rights.

Consequently, they were assimilated to the social racial

classification, along with other Hispanic proletarian

immigrants, as citizens or non-citizens of second or third

category (Almaguer 1994). Proletarianization was the

manifestation of the coloniality of power, understood as

the capacity of coloniality to function even after the histor-

ical demise of colonialism, resulting in the constitution of

racialized subjects whose access to labor compensation,

property and social rights was negatively affected.

Studying the racialized restrictions on third world immi-

grants to the U.S. from 1924 to 1965 and the production

of illegality, Mae Ngai (2004) outlined the emergence of

the illegal alien as a racialized and discriminated against

actual presence that cannot turn itself into a full person.

This specific form of limited belonging was an “inclusion

in the nation [that] was simultaneously a social reality

and a legal impossibility,” and it generated what Ngai

calls “impossible subjects” (2004, 4).

Latinx immigrants have historically emerged as these

impossible subjects within the historical context of Califor-

nia. Similarly, a conspicuous contemporary case involves

undocumented students, who inhabit a dual status of

being a tangible social presence and simultaneously

facing legal precarity that renders their existence either

implausible or significantly limited. Thus, “the Integrated

Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), the

National Center for Education Statistics’ (NCES) core

postsecondary education data collection program,

designed to help NCES meet its mandate to report full

and complete statistics on the condition of postsecond-

ary education in the United States for the Department of

Education” (IPEDS, 1), does not count undocumented

students, despite their relevance for states like Califor-

nia. Their case is a specific manifestation of a much

more generalized dynamic historically modulating the

forms of economic, social, political, and cultural belong-

ing and exclusion of Latinx populations in California.

Coloniality, proletarianization, impossible subjects, and

racialization processes, as well as the ensuing struggles

for equity and social justice, are then the historical roots

of the coexistence of dynamics of relative inclusion and

significant exclusion of Latinx populations in the state of

California today. In other words, the experience of Latinx

populations are characterized by limited participation

and access, as well as notable exclusion, whether in

historical or contemporary contexts, all of which are

shaped by the enduring influence of racial identification

within the framework of coloniality.

The UC has been a crucial space in which these dynam-

ics have unfolded and is now one of the central sites

where these issues can be redressed and the nation’s

ongoing struggle for equity and social justice can be

fought. These dynamics can be retraced from the

historical exclusion of Latinx students to their present-day

inclusion at the undergraduate level, thus showcasing

the gradual demographic arrival and integration of Latinx

students into UC. From 1980 to 2020, enrollment of

11 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

Latinx undergraduates at the UC grew by a factor of 10,

and their percentage of all undergraduates almost

quintupled (Table 1

3

).

At the graduate level, as expected, growth has been

slower but increasingly significant; the number of Latinx

graduate students enrolled in the UC system quadrupled

since 1980 and close to tripled as a percentage of the

total graduate student population (Table 2

4

).

Despite this expansion, both undergraduate and gradu-

ate students, and, even more significantly, faculty and

senior management, are categories in which Latinx

people are still underrepresented in the UC, considering

3 Source: The University of California Statistical Summary of Students and Staff. Fall 1981, 1990, 2000, 2010. Source 2020: Fall enrollment at a glance

| University of California

4 Source for 2020: Fall enrollment at a glance | University of California. Source: The University of California Statistical Summary of Students and Staff.

Fall 1981, 1990, 2000, 2010

5 Source: The University of California Statistical Summary of Students and Staff. Fall 1981, 1990, 2000, 2010. Source: UC workforce diversity | University

of California.

*Latinx is reported as Hispanic.

their demographic size in the state today. According to

the UC system, the two major categories of UC person-

nel are: 1) Academic: including academic administrators,

regular teaching faculty, lecturers, and other teaching

faculty, student assistants, researchers, librarians,

cooperative extension researchers, university extension

faculty, and other academic personnel; and 2) Non-aca-

demic: including senior management (SMG), manage-

ment and senior professionals (MSP), and professional

and support staff (PSS). How underrepresented Latinx

people are in the UC system in those two key personnel

categories in the last four decades can be clearly seen

in Tables 3–5

5

.

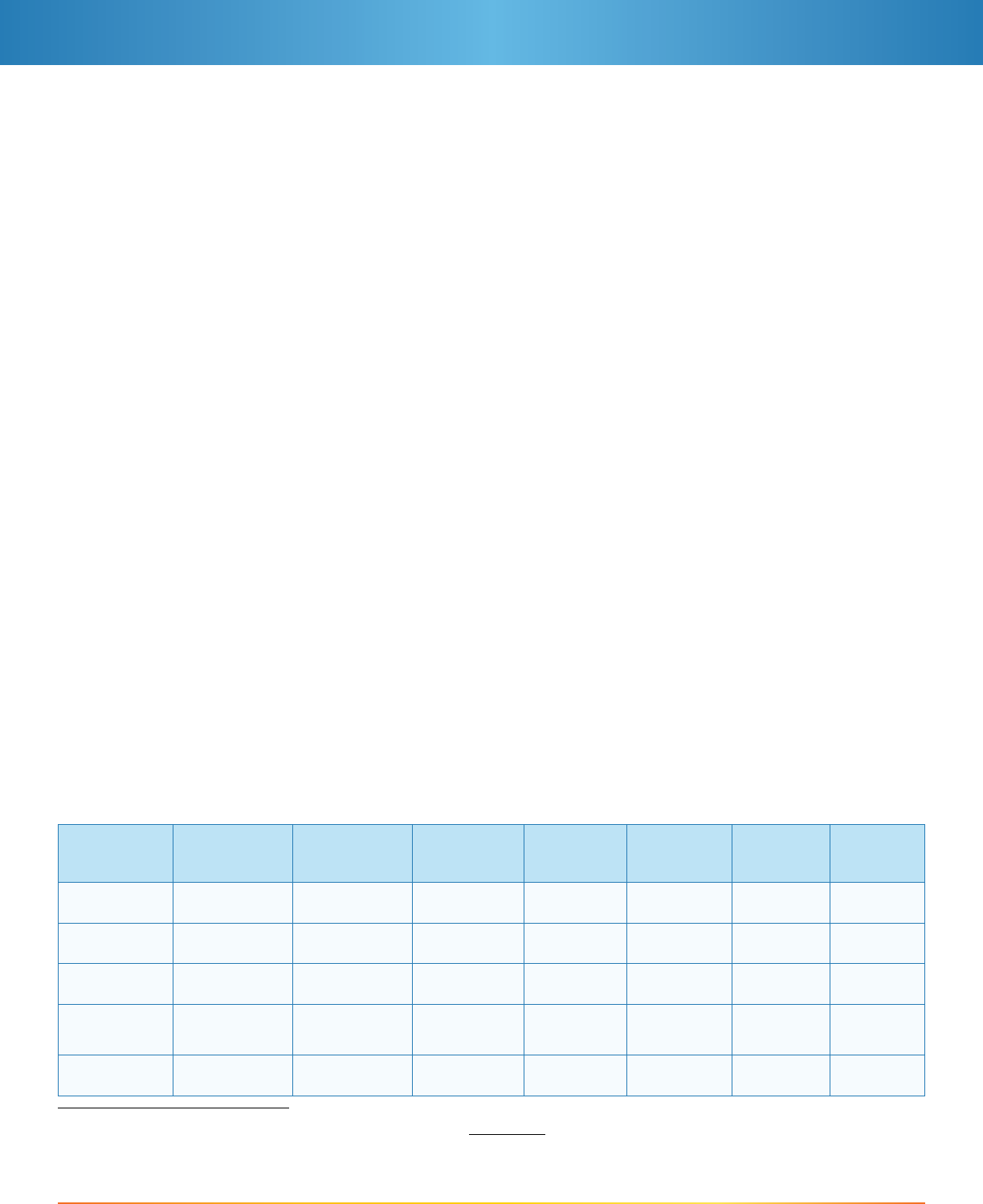

1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

Total 66,993 88,858 106,351 126,702 123,372

Latinx 5,474 10,876 16,734 22,721 29,856

% Latinx 8.2% 12.2% 15.7% 17.9% 24.2%

1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

Total 38,719 41,089 41,989 54,883 59,267

Latinx 1,633 2,443 2,681 4,084 6,751

% Latinx 4.2% 5.9% 6.4% 7.4% 11.4%

Table 2: All UC Campuses Fall

Enrollment–Graduate Level*

Table 4: University of California

Non-Academic Personnel

1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

Total 27,225 37,908 44,960 58,687 73,012

Latinx 849 1,758 2,582 3,492 5,816

% Latinx 3.1% 4.6% 5.7% 5.6% 8.0%

Table 3: University of California

Academic Personnel

1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

Total 97,102 125,458 141,366 179,581 226,449

Latinx 5,355 14,284 17,402 31,909 56,667

% Latinx 5.5% 11.4% 12.3% 17.8% 25.0%

Table 1: UC Campus Fall Undergraduate

Enrollment: 1980–2020*

*Latinx reported as Chicano and Latin American for 1980 and 1990. Latinx reported as Chicano/Chicana and Latino/Latina for 2000. Latinx reported as

Hispanic/Latino(a) for 2020.

12 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

The arrival of Latinx students into the UC system,

constituting our initial long-term process, has always

been an inevitable demographic occurrence, intricately

interwoven within the broader historical trajectory of

constrained inclusion, often accompanied by marked

exclusion. However, this arrival has also been con-

strained in its potential for transformative impact, due to

its alignment with the concurrent unfolding of two other

processes: a noteworthy reduction in public education

funding and a parallel tendency towards the privatization

of financial support for public higher education. These

two latter dynamics are intricately connected.

Thus, according to UC data, adjusted for inflation, as

6 Source: https://accountability.universityofcalifornia.edu/2021/chapters/chapter-12.html#12.1.5

shown in Figure 2 below: “since 1990–91, total instruc-

tional expenditures per UC student have declined by

21%,” while “students and their families bear a greater

share of that cost.” In other words, California, as a state,

invests less in students (today, on a per capita basis,

less than 50% than in 1990) precisely when more

first-generation and working-class students of color are

entering the system, placing an increased financial

burden on them and their families to finance their educa-

tion (today, twice as much, through tuition increases and

loans, than they did in 1990) (See Figure 2

6

with infla-

tion-adjusted amounts).

State-provided education has nationally, on the other

hand, come to depend on the payment of tuition through

federal loans by the families of many of these newly

arriving students of color. As Josh Mitchell’s The Debt

Trap. How Student Loans Became a National Catastro-

phe (2021) makes clear, a vicious circle has developed

between underfunding of state schools and the growth of

tuition paid for by loans in both state and private schools:

“The more colleges raise tuition, the more Americans

borrow. The more Americans borrow, the more colleges

raise tuition” (2021,7). In that scenario, today “more than

two-thirds of undergraduates borrow, and those who do

graduate owing an average of $29,000. [...] A generation

2000 2010 2020

Total 5,312 9,285 16,801

Latinx 262 591 1,646

% Latinx 4.9% 6.4% 9.8%

Table 5: SMG & MSP (Managers, Senior

Professionals, and Senior Management Group)*

*In 2010, the UC recategorized some academic administrators (mostly

deans) from SMG staff to academics.

State General Funds Tuition/Fees (Cal Grants) Tuition/Fees UC General Funds

$7,500

$2,510

$7,420

$3,670

$21,100

2018–19

$8,140

$2,290

$6,230

$3,760

$20,420

2019–20

1990–91

$20,850

$430

$2,920

$2,450

$26,650

$16,030

$5,070

$2,340

$24,420

1995–96

$980

$18,530

$4,030

$2,370

$25,740

2000–01

$810

$12,530

$5,560

$2,660

$21,850

2005–06

$1,100

Figure 2: Core Fund Expenditures for Instruction Per Student

13 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

ago it was rare to owe $60,000 in student debt; now

more than seven million Americans owe that much”

(2021,7).

The interlinked dynamics of defunding and privatization,

operating on both a national and interconnected level,

have limited the potential impact of the arrival of people

of color and non-traditional students to higher education

in the U.S. This also pertains to Latinx students’ access

to California’s premier tier of public education. These

dynamics are analyzed in a series of important and

recent books such as Caitlin Zaloom’s Indebted, How

Families Make College Work at Any Cost (2019), Eliza-

beth Tandy Shermer’s Indentured Students. How Gov-

ernment-Guaranteed Loans Left Generations Drowning

in College Debt (2021); Josh Mitchell’s The Debt Trap.

How Student Loans Became a National Catastrophe

(2021), Tressie McMillan Cottom’s Lower Ed. The

Troubling Rise of For-profit Colleges in the New Econo-

my (2017), and Christopher Newfield’s The Great

Mistake. How We Wrecked Public Universities and How

We Can Fix Them (2016).

For Elizabeth Tandy Shermer, the multiple comparisons

sprouting from the end of the 20th century into the 21st

between indentured labor and educational debt have an

underlying commonality: as did workers of color in the

past, many students throughout the nation today—espe-

cially those from low socioeconomic backgrounds

(preyed upon by for-profit colleges more interested in

capturing federal loans than in effectively educating and

graduating students)—find themselves unable to escape

the debts acquired in the pursuit of their degrees, debts

that, instead of decreasing with time, tend to increase

through interests and penalties. As a result, “Student

debt has become one of the largest categories of Ameri-

can consumer debt, second only to home mortgages, in

the new millennium” (2021,3). Differences in families’

capacities to pay tuition mean that a working-class

family will pay more money over time than a wealthy one

for the same degree, increasing “the racial wealth gap,”

accomplishing the opposite of the historical promise of

education. Mitchell (2021) opens with the illustrative

case of an adult student, two years into an educational

loans-generated bankruptcy, who had gone into college

to get a BA and then to graduate school to get a degree

that would allow her to become a psychologist:

Exhibit 1 of her bankruptcy documents listed how

much she had sent over the years to Sallie Mae and

its spinoff, a company called Navient, to repay her

student loans. Month after month, year after year [for

seventeen years], she mailed off those payments,

each check for more than $700. After some 160

checks, she had paid $135,603.34. Most of it,

$100,000, went toward interest, padding the profits

of Sallie Mae. Her balance now sat at $96,820. (7)

Lest this be seen as an aberration exploited only in the

for-profit sector, Shermer clarifies that “By 2017 state-

school graduates [nationally] had an 11 percent default

rate, just a few points less than for-profits’ percentage”

(5). Likewise, it is not only a problem for working-class

families but one with the capacity to redefine the experi-

ence of middle-classness in the U.S., as Caitlin Zaloom

(2019) makes clear: “Today being middle class means

being indebted. It means feeling insecure and uncertain

about the future, and wrestling with the looming cost of

college and the debt it will require” (1).

Tressie McMillan Cottom’s Lower Ed. The Troubling Rise

of For-profit Colleges in the New Economy (2017) points

to the unexpected synergy between traditional higher

education in not-for-profit institutions and for-profit

colleges: “Lower Ed can exist precisely because elite

Higher Ed does. The latter legitimizes the educational

gospel [as a morally and financially sound investment]

while the former absorbs all manner of vulnerable

groups who believe in it: single mothers, downsized

workers, veterans, people of color, and people transition-

ing from welfare to work” (11).

After describing the history of the federal student loans

program, Josh Mitchell concludes:

The student loan program is the quintessential form

of crony capitalism. It privatized profits and socialized

losses. In an echo of the housing bubble, all the risk

fell to students and their families, who have been told

repeatedly that college and grad school are safe and

necessary investments. The narrative of higher

education as a ticket to the American Dream fueled

the exploitation of good intentions by bad actors. (18)

14 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

After showing how, in a tuition and loans system, racial

wealth inequality affects college affordability and post-

secondary educational success, including “students’ abil-

ity to attend college, complete their studies, and depart

with a reduced debt burden,” Fenaba R. Addo and Lorna

Jorgensen Wendt conclude their essay on “The Racial-

ization of the Student Debt Crisis” (2020) by stating: “A

debt-financed higher education system in a society with

extreme wealth inequality means those with fewer

resources are more likely to take on debt to access

postsecondary education” (211). Unfortunately, relative

defunding and privatization of cost have been two of the

contemporary forms of historical inclusion/exclusion or

qualified inclusion determining the social trajectory of

Latinx people in California.

In The Great Mistake. How We Wrecked Public Universi-

ties and How We Can Fix Them (2016), Christopher

Newfield traces the intertwined history of this double

privatization of public education as a social reality and as a

concept. He makes clear that this is not a problem exclu-

sively produced by a bad system of financing but, instead,

one generated by a fundamental change in our concept

of public education as, centrally, a private and individual

good instead of part of the common good. This point is

important for this paper’s argument because delivering on

the progressive and democratizing promise and potential

of the University of California becoming the premier

HSRI public education system in the nation depends, to

a significant extent, on the institution’s honoring of

education’s public good status. This promise depends on

UC’s commitment to shifting from a focus on equitable

access work to widely distributed excellence. After all, by

2019–2020 “The majority of Latinos earned their degrees

at a public institution. Over 70% of Latinos that earned a

certificate or degree did so at a public four-year (42%) or

public two-year (29%)” and “Over half of Latinos who

earned a degree [in 2019–20] did so at a Hispanic-Serv-

ing Institution (HSI). HSIs awarded 55% of the degrees

Latinos earned in 2019–20” (Excelencia, 2022, n.p.).

Defying the dominant ideology about the origins of the

contemporary troubles in public higher education in the

U.S., Newfield sees those problems as not stemming

7 Source: www.equityinhighered.org/indicators/u-s-population-trends-and-educational-attainment/educational-attainment-by-race-and-ethnicity

from a lack of business acumen in the sector or from its

distance from market logic. Instead, for him they are the

direct reflection of the penetration of such logic into the

sector. This affects public higher education in two

connected ways: the relative privatization of funding and

the lack of understanding of what are the meaning and

goals of public education itself.

To Newfield, “the American Funding Model” of public

higher education is “broken”: “It has been broken by too

much private funding and service to private interests”

(2016, 4). His diagnosis: “Private sector ‘reforms’ are not

the cure for the college costs disease—They are the

college cost disease” (4). They lower educational quality

and raise costs. His concise formula for such an analysis

is: “low public funding equals high tuition equals high

student debt equals lower access equals lower college

attainment, period.” (12).

Newfield traces the origins of the ideological transforma-

tion that facilitated a substantial level of higher education

privatization back to the Reagan era and the era of

economic uncertainty. He clarifies that this transforma-

tion didn’t directly entail the transfer of public assets to

private ownership. Neoliberalism, one of the ideological

responses to such a situation, resulted in the white

middle class voting to lower their taxes and weakening

of support for public infrastructure more generally.

Ideologically, such diagnosis: “narrowed the value of

college to the individual’s private investment in their

future earnings while stigmatizing public benefits,

particularly racial equity via race-conscious admissions,

as attacks on private interests” (39).

Newfield argues that in continuous 20th century expan-

sion, by 1980, the U.S. was still a world leader in educa-

tional attainment, but by 2015 had moved into “a middle

of the pack” position (45). As we have seen, those same

four decades were also the years of the arrival of Latinx

students to the UC system. The promise of such an

arrival was to begin correcting the still very unequal

distribution of educational attainment nationally, as seen

in Figure 3 on the following page

7

:

15 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

The neoliberal response, as it did in many other areas of

life such as health and social services, misunderstood or

misconstrued the meaning and goals of public education

itself. Faced with budgetary crisis, partly produced by

the neoliberal cutting of taxes, educational leaders felt

compelled to embrace the neoliberal definition of public

education as a private good, something like an invest-

ment the individual made on their own future, and thus

something they should be willing to incur debt to pay for.

This, in turn, became the basis for justifying tuition

raises to address California’s decreased funding. This is

a cycle that has significantly privatized public education.

According to Newfield, tuition increases in the 1980s

and 1990s preceded and were initially independent of

the funding cuts (42). This cycle became part of the

informal agreement between state legislatures and state

higher education leaders; tuition raises could be justified

by state cuts, and the latter could be absorbed by tuition

increases, allegedly without affecting the quality of

education. Nationally, “state appropriations for public

colleges and universities declined by 25 percent in

constant dollars between 1989 and 2014. During the

same period, net student tuition doubled” (18).

The accepted main rationale, on both the state and

college sides, was that an education would eventually

amply compensate the individual beneficiary for the

investment and the temporary debt. For Newfield, this

was only one half of the historical understanding of such

rationale in the previous 20th century expansion of

public higher education. Forgotten was the second half

that insisted on private-nonmarket and public benefits for

all, such as democratization, a generalized intellect

based on skills and cognitive development, better health,

and a more informed electorate. What was forgotten

then was the dual nature of public education: “It has

obvious private good features like increasing a gradu-

ate’s future personal income, and it has an equally public

good status” (65). Newfield understands the notion of

public good as “a good whose benefit continues to

increase as it approaches universal access” (64). In fact,

those socially distributed benefits depend precisely on

public funding to achieve something close to universality

within a society. Absent public funding, higher education

transforms into a privilege distinguishing some from

others, instead of connecting them as a society and

benefiting all of them as a group. Using economist Walter

W. McMahon’s calculations of the benefits of higher

education, Newfield divides the yearly benefits into

thirds: private market benefits (as return on investment)

= $31,174 (in 2007 dollars); direct and indirect nonmar-

ket private benefits = $38,080, including the ability to

work in areas with high compensation, affording high

quality of life and services; and direct and indirect social

benefits = $31,180. More than 50% of the benefit of

higher education, according to McMahon, could be

< High School Associate

Doctoral

Bachelor’s

Master’s Professional

High School Some College/No Degree

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

All racial & ethnic groups

American Indian or

Alaska Native

Asian

Black or African American

Hispanic or Latino

Native Hawaiian or other

Pacific Islander

White

More than one race

Figure 3: U.S. Educational Attainment of Adults Ages 25 and Older by Race and Ethnicity, 2017

16 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

deemed externalities, i.e., benefits realized by others in

society as a result of the individual’s education. Newfield

concludes: “In sum, standard calculations of the value of

college are completely wrong. They miss about two

thirds of its overall value” (72).

Elizabeth Popp Berman’s book, “Thinking like an Econo-

mist: How Efficiency Replaced Equality in U.S. Public

Policy” (2022), elucidates the historical evolution of what

she terms “the economic style of reasoning” (13), which

has supplanted other conceptual frameworks, such as

“universalism, rights, and equality” (38), in shaping

public policy design in the United States since the

1970s. Unlike denunciations of right-wing neoliberalism

at the macroeconomic level, Popp Berman’s account

emphasizes, at the microeconomic level, the central role

played by center-left economists and thinkers in the

supposedly neutral privileging of “markets as efficient

allocators of resources’’ and efficiency itself as the

supreme value for all realms of life, including areas

“such as education or healthcare, that are not governed

primarily or solely as markets” (17).

The social and individual benefits of a public education,

its dependence on broad access and high quality mas-

sively distributed among the population, its contribution

to social mobility, and the democratization of the benefits

of economic development are part of what I termed as

the progressive and democratizing promise and potential

of the University of California. In particular, UC’s path to

becoming the premier HSRI public education system in

the nation is an opportunity to think about how a public

understanding of education and servingness (García,

2020) help us honor and enhance the social benefits of

education as a public good. Rather than constituting a

paradox, the notion of combining extensive inclusivity

with substantial research endeavors is exemplified by

the concept of HSRI, an educational classification that,

though still uncommon, is progressively gaining ground.

This term encapsulates a noteworthy endeavor in itself.

8 An R-1 institution is, according to the Carnegie Classication of Institutions of Higher Education, a university that produces “very high research activity”

(Carnegie)

The promise and potential of UC as an HSRI

system as seen in the example of UC Santa

Cruz

As a research-intensive (R-1) institution, UC Santa Cruz

is, as of 2022, one of 20 Hispanic-Serving Research

Institutions (HSRIs) and one of two HSRIs and Asian

American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving

Institutions (AANAPISIs) elected to the American Associ-

ation of Universities (AAU). UC Santa Cruz has earned

international distinction for its high-impact research and

uncommon commitment to teaching, public service, and

social justice.

In 2012, as UC Santa Cruz anticipated reaching 25%

Latinx undergraduate student enrollment, a task force of

faculty, staff, and students was charged with planning how

the campus would implement its HSI mission (Reguerín

et al., 2020). The task force began by reviewing relevant

research models, empirical evidence, and best practices

to address the question “What accelerates or impedes the

academic and socioemotional success of our Latina/o

students?” It was the first time the campus systematically

used data disaggregated by race/ethnicity, socio-eco-

nomic status, and gender to study Latinx students’

academic pathways, complemented by the voices of

Latinx undergraduates, who developed and presented

their study of this question at the American Educational

Research Association (Reguerín et al., 2020). This work

allowed UC Santa Cruz to begin asking questions about

itself such as: What is the meaning of HSI servingness

and more specifically within an HSRI (Hispanic-Serving

Research Institution)? Our now 10-year long HSI trajec-

tory is captured by the further evolution of our initial

guiding question about what accelerates or impedes the

academic and socio-emotional success of our Latina/o

students to our current guiding questions:

• What forces accelerate or impede the holistic success

of Latinx, low-income, and first-generation undergradu-

ate, transfer, and graduate students at UC Santa Cruz?

• What educational interventions, student-centered

practices, and investments can increase UC Santa

Cruz’s capacity as a public R-1 institution

8

to support

successful academic and career pathways of Latinx,

17 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

low-income, and first-generation undergraduate,

transfer, and graduate students?

• What structures, changes, and institutional

investments can increase the capacity of UC Santa

Cruz, as a public R-1 HSI, to serve as a UC and

national leader in redefining servingness, achieving

equity, and promoting social mobility?

The comprehensive redefinition of the purpose and extent

of our educational endeavors carries a significant

implication—the potential for HSI initiatives to reintro-

duce and emphasize inquiries like: What is the meaning

and mission of public education? What are the connec-

tions among public education, the public who funds it in

California, and both of their futures? What does educa-

tional equity mean in this context and how do we

achieve it? It also means exploring the possibilities of

being a public, HSRI, and R1 educational institution and

system. This centrally involves exploring, expanding and

developing the meanings of “servingness” (García,

2020; Reguerín et al, 2020) by probing the fit between

the needs of our students and our institutional capacity

to satisfy them, in ways that lead to equity of results at

all levels of the educational process:

• How do underrepresented students experience the

institution?

• Are classes designed for the success of students from

underrepresented groups (URGs)?

• Are departments and their faculty—through their

courses, schedules, curricular logics and course

sequences, and major requirements—cognizant of the

differential impact they may have?

• Are we ready to investigate our own practices and

premises to be more effective in our work towards

educational equity?

• Are all campus divisions (academic, student affairs,

advising, etc.) coordinating?

• How can we bridge their practices?

Since “race” can be historically seen as one of the

organizing principles structuring inequality in U.S. history

(Omi & Winant, 2014 )—and, certainly, determining the

status of Latinx people in California—and given that “In

post-secondary education in the United States, the core

educational concepts of college, college students, and

education are racialized by the ideological values of

merit and equal opportunity [...] which block awareness

of structural racism” in education (Dowd and Bensimon,

p.1–2), UC Santa Cruz’s HSI Initiatives developed a set

of Guiding Principles for Becoming a Racially Just HSI

(Reguerín et al., 2020, p. 57):

• Move from successful admission of racially diverse

students (our strengths) to equitable outcomes and

experiences across all racial groups (our challenge).

• Raise awareness and consensus building by disag-

gregating data by race and other identities.

• Reject attempts to mute race and highlight racial (in)

equities at every opportunity.

• Improve inclusion and campus climate by redesigning

gateway classes and providing professional develop-

ment with faculty and staff to meet needs of all students.

• Introduce socially and culturally informed innovations in

teaching and practice, including those centered on

minoritized ways of knowing and being.

• Build on successes and acknowledge challenges and

issues revealed by ongoing inquiry.

As we undertake the revision of these principles to align

with the expansive evolution of our HSI endeavors,

which now encompass all educational levels (ranging

from undergraduate to transfer to postgraduate educa-

tion and faculty roles) and all facets (including admission,

the first-year experience, retention, persistence, profes-

sional preparation and timely and successful graduation,

as well as postbaccalaureate access and achievement)

within the educational pipeline, they vividly underscore

our dedication to confronting the interconnected structure

between “race” and unequal educational outcomes.

Moreover, these revisions serve to emphasize our

commitment, both as researchers and practitioners, to

scrutinize our educational practices to prevent any

participation in perpetuating social inequality and to

propel the cause of educational justice forward.

The choice to prioritize the examination of structural

disparities in access, opportunities, readiness, and

outcomes, and to subsequently scrutinize our institutional

practices through both cognitive and non-cognitive

lenses, with the objective of preventing the perpetuation

of inequality and initiating steps towards rectification,

stands as a pivotal embodiment of servingness at UC

Santa Cruz as an HSRI. Such work has allowed us to

18 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

improve many of our institutional practices—including

our gateway and other required classes in STEM,

introductory literacy and mathematics classes preparing

students from different backgrounds for success in

college—build a transfer-receptive culture (Herrera &

Jain, 2013), provide access to research and internship

opportunities, and address graduate students’ need for

writing support.

These efforts allowed us to see that if we want to be

more effective with all our students, we must change

institutionally. They helped us see that our problems

achieving equity of results were not centrally an issue of

students’ alleged under-preparation but instead of our

institutional relative (in)capacity to meet our students’

needs and hopes. Moreover, HSI work—reorienting our

priorities to serve the needs of the students who need us

the most, often the majority of students in many of the

UC campuses now—also holds the promise of improv-

ing educational attainment for all students. By concen-

trating on the quality and actual results of students’

learning experiences and support services, we improve

our capacity to foster success among all our students.

The Challenges We Must Meet

The array of challenges we must confront to fully harness

the potential of HSI efforts in substantially enhancing

equitable outcomes throughout the University of California

is extensive. In essence, we are tasked with achieving

9 Sources: California demographics: Public Policy Institute of California: www.ppic.org. Personnel: UCSC personnel prole 2019–20. Faculty welfare:

UCSC Committee on Faculty Welfare May 2018.

more with fewer resources to effectively meet the re-

quirements of a markedly diversified student population.

This paper has argued that the increasing levels of

student debt and underfunding per capita by the state

are fundamental challenges to the transformative power

of higher education in California. They are structural

conditions that no amount of HSI work can fully neutral-

ize. We must then recover our view of public education

as a fundamental public good, in which we collectively

invest because we strive for educational equity, social

justice, and a better future for all. The current Latinx

underrepresentation at all levels of university life poses a

significant problem that was notably evident at UC Santa

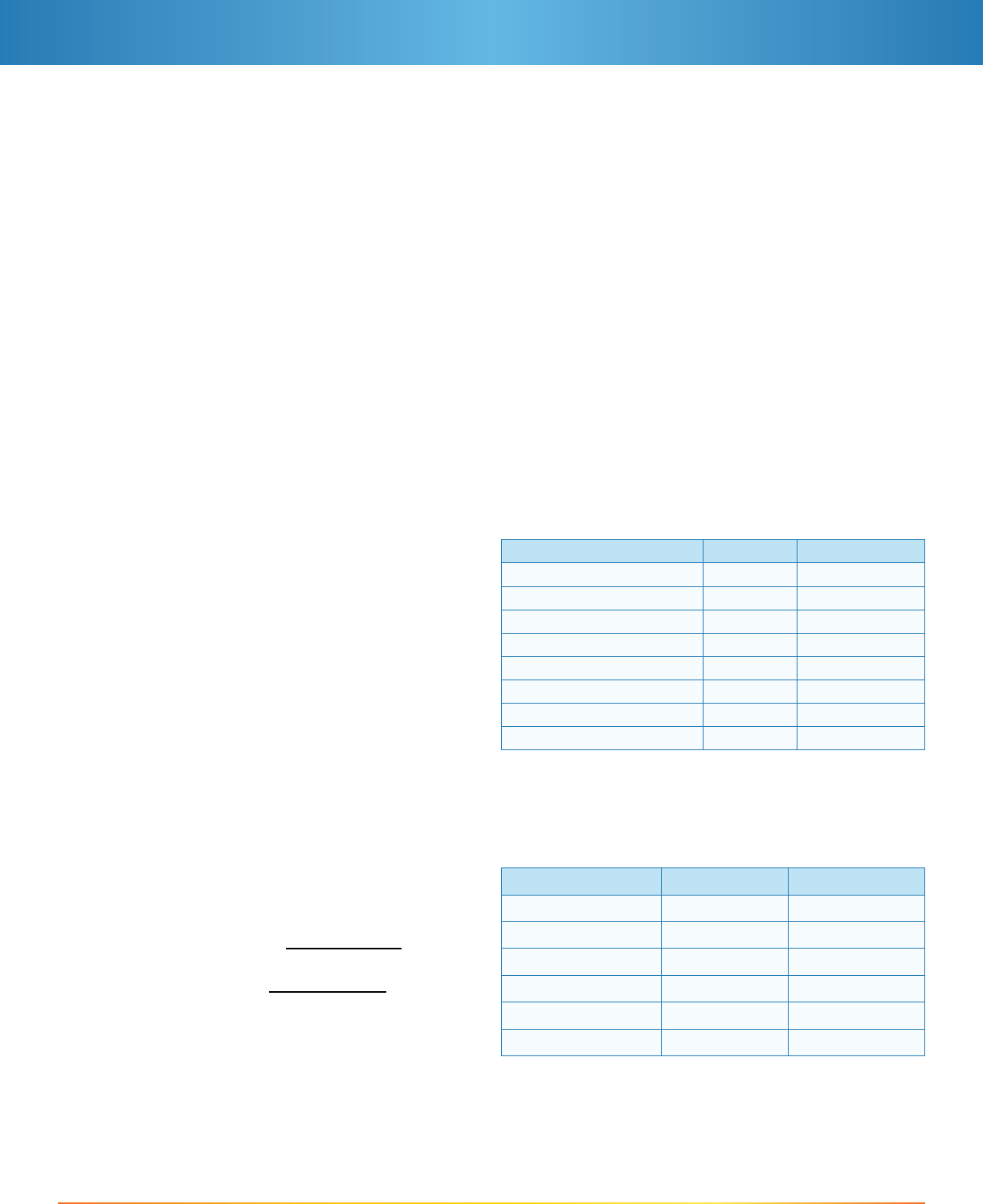

Cruz in 2019, as shown in Table 6.

9

Taking into account that UC Santa Cruz boasts a com-

mendable diversity profile in numerous categories within

the UC system, encompassing the percentage of both

undergraduate and graduate students, as well as

faculty members, it becomes apparent just how pro-

found and significant the imbalanced representation of

Latinx individuals within UC system truly is. The fact that

a considerable portion of our senior management

remains predominantly White implies that the input of

people of color is less impactful than what the state’s

demographic makeup necessitates. Furthermore, the

limited presence of Latinx graduate students introduces

complexities in terms of attaining improved representa-

tion among faculty members and senior administrators in

Race/Ethnicity

CA Population

(2019) PPIC

Ladder-Rank

Faculty

Lecturers

(Individuals)

Management

Senior Staff

(Individuals)

Professional

Support Staff

(Individuals)

Graduate

Students

Undergrad

Students

Latinx 39%

10%

(55 individuals)

31 35 759 10% 27%

White 37%

65%

(361 individuals)

221 373 1,369 40% 30%

Asian, P.I. 15%

17%

(100 individuals)

29 34 254 11% 28%

African. Am. 6%

3%

(18 individuals)

7 14 102 3% 4%

Native Am. 1.6%

2%

(11 individuals)

3 5 23 1% 1%

Table 6: Levels of Representation by Race/Ethnicity at UCSC in 2019

19 | A Blueprint for Becoming a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution (HSRI) System

Reimagining the University of California to Serve Latinxs Equitably

the future. While we have made strides in expanding

undergraduate access to UC, the composition of the

faculty has not experienced a similar democratization.

This imbalance leaves the few professors in place

shouldering an excessive load, sometimes grappling

with an overwhelming volume of student and institutional

demands on their time and attention.

A different challenge is highlighted in Laura Hamilton

and Kelly Nielsen’s Broke: The Racial Consequences of

Underfunding Public Universities (2021). The authors

use the case of the UC system to illustrate two opposing

but connected dynamics affecting public university

systems across the country. First, they discuss the racial

consequences of what they call “postsecondary racial

neoliberalism,” where using individual “merit” to launder

family and class privilege results in significant levels of

per capita defunding for under-represented students

who, lacking cultural, social, and economic capital

relative to most of their White peers, are most in need of

resources and support (20). Second, they highlight the

limitations and possibilities of what they call “new univer-

sities” such as UC Merced and UC Riverside, “schools

that pair high research ambitions with predominantly

disadvantaged student populations” (3). The limitations

are derived from the mismatch between student needs

and available per capita funding. They include “potential-

ly risky public-private partnerships (or P3) as a strategy

for building and maintaining large portions of campus”

(25), “austerity practices”, and “tolerable suboptimization”

of services such as “academic advising, mental health

services, and cultural programming” (25). The possibili-

ties, on the other hand, paradoxically reside in the

transformational potential of the work that is required to

make underfunding compatible with high research,

diversity with excellence, and racial inclusion with full

socialization of knowledge and creativity. Such potential

may entail successfully ‘breaking’ the mold of the tradi-

tional (predominantly White) research university.

Although the UC system is significantly more democratic

in demographic composition and in Pell grant recipients’

participation than other large higher education public

systems in the country and, certainly, is more inclusive

10 URS refers to historically underrepresented racially marginalized students.

than most research universities, it still has a hierarchy of

trajectory, endowments, and prestige that makes some

campuses (UC Berkeley and UCLA at the top) fund most

of their educational per capita expenditures with private

resources and out-of-state enrollments; while other

campuses such as Merced, Riverside and Santa Cruz

must fundamentally rely on decreasing state funding.

This situation risks what the authors call the perils of a

stratified UC system, resulting in an unequal “co-opetition,”

both cooperation and competition, for UC resources (86).

In that context, UC Merced and UC Riverside provide