Mississippi Morbidity Report

Annual Summary

Selected Reportable Diseases

Mississippi – 2013

Volume 32, Number 4 December 2016

MISSISSIPPI STATE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH

Mississippi Morbidity Report

Annual Summary

Selected Reportable Diseases

Mississippi – 2013

Page Left Blank Intentionally

Table of Contents

Preface .................................................................................................................................. 5

Mississippi Public Health Districts & Health Officers ........................................................... 7

Reportable Disease List ........................................................................................................ 8

Arboviral Infections (mosquito-borne) ............................................................................. 12

• Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) .......................................................................... 13

• LaCrosse Encephalitis ............................................................................................. 14

• St. Louis Encephalitis ............................................................................................... 15

• West Nile Virus ......................................................................................................... 16

Campylobacteriosis ........................................................................................................... 20

Chlamydia .......................................................................................................................... 23

Cryptosporidiosis ................................................................................................................ 27

E. coli O157:H7/ STEC / HUS ............................................................................................... 28

Gonorrhea .......................................................................................................................... 31

Haemophilus influenzae, type b ....................................................................................... 35

Hepatitis A ........................................................................................................................... 37

Hepatitis B, acute ............................................................................................................... 39

HIV Disease ......................................................................................................................... 43

Influenza – 2013 – 2014 Season ......................................................................................... 48

Legionellosis ....................................................................................................................... 52

Listeriosis ............................................................................................................................. 53

Lyme Disease ..................................................................................................................... 55

Measles ............................................................................................................................... 56

Meningococcal disease, invasive .................................................................................... 59

Mumps ................................................................................................................................ 62

Pertussis ............................................................................................................................... 63

Pneumococcal disease, invasive ..................................................................................... 66

Rabies .................................................................................................................................. 68

Rocky Mountain spotted fever .......................................................................................... 70

Rubella ................................................................................................................................ 73

Salmonellosis ...................................................................................................................... 74

Shigellosis ............................................................................................................................ 77

Syphilis ................................................................................................................................ 80

Tuberculosis ........................................................................................................................ 86

Varicella .............................................................................................................................. 90

Vibrio disease ..................................................................................................................... 91

Special Reports ................................................................................................................... 96

• Enhanced Surveillance of Adult Influenza Mortality, 2013-2014 Influenza Season

................................................................................................................................. 96

• Haff Disease Identified in Three Mississippi Residents, July 2013 ........................ 98

Reportable Disease Statistics ...........................................................................................100

List of Contacts, Editors and Contributors ........................................................................102

General References ..........................................................................................................103

Return to Table of Contents

Preface

Public health surveillance involves the systematic collection, analysis and dissemination

of data regarding adverse health conditions. The data are used to monitor trends and

identify outbreaks in order to assess risk factors, target disease control activities,

establish resource allocation priorities and provide feedback to the medical community

and the public. These data support public health interventions for both naturally

occurring and intentionally spread disease.

Statistics incorporated into tables, graphs and maps reflect data reported from health

care providers who care for Mississippi residents. Cases counted have met the

surveillance case definitions of the CDC and the Council of State and Territorial

Epidemiologists (CSTE), available at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/search/

.

Unless otherwise noted all rates are per 100,000 population. Data are based on “event”

date of the case with the exception of TB in which the case confirmation date is used.

The “event” date is defined as the earliest known date concerning a case and is

hierarchical (onset, diagnosis, laboratory date or date of report to the health

department).

Mississippi law (Section 41-3-17, Mississippi Code of 1972 as amended) authorized the

Mississippi State Board of Health, under which MSDH operates, to establish a list of

diseases which are reportable. The reportable disease list and the Rules and

Regulations Governing Reportable Diseases and Conditions may be found online at

http://www.msdh.state.ms.us/msdhsite/_static/14,0,194.html

. Class 1A diseases,

reportable by telephone within 24 hours of first knowledge or suspicion, are those to

which the MSDH responds immediately to an individual case. Class 1B diseases are

those that require individual case investigation but do not require an immediate public

health response and can therefore be reported by telephone within one business day

of first knowledge or suspicion. Class 2 diseases are reportable within a week of

diagnosis, and Class 3 diseases are reportable only by laboratories and do not

necessitate an immediate response to an individual case.

To report a case of any reportable disease or any outbreak, please call 601-576-7725

during working hours in the Jackson area, or 1-800-556-0003 outside the Jackson area.

For reporting tuberculosis, you also may call 601-576-7700, and for reporting STD’s or

HIV/AIDS, you may call 601-576-7723. For emergency consultation or reporting Class 1A

diseases or outbreaks afterhours (nights, holidays and weekends) please call 601-576-

7400.

The data included in the following document have come from physicians, nurses,

clinical laboratory directors, office workers and other health care providers across the

state who called or sent in reports. Without these individuals, public health surveillance

5

Return to Table of Contents

and response would be incapacitated. For your dedication to this important part of

public health information, we thank you.

Paul Byers, MD

State Epidemiologist

6

Return to Table of Contents

Mississippi Public Health Districts & Health Officers

Public Health

Districts

Northwest Public Health

District I

Dr. Alfio Rausa

662.563.5603

Northeast Public Health

District II

Dr. Crystal Tate

662.841.9015

Delta/Hills Public Health

District III

Dr. Alfio Rausa

662.453.4563

Tombigbee Public Health

District IV

Dr. Robert Curry

662.323.7313

West Central Public Health

District V

Dr. Kathryn Taylor

601.978.7864

East Central Public Health

District VI

Dr. Christy Barnett

601.482.3171

Southwest Public Health

District VII

Dr. Leslie England

601.684.9411

Southeast Public Health

District VIII

Dr. Christy Barnett

601.271.6099

Coastal Plains Public Health

District IX

Dr. Christy Barnett

228.436.6770

7

Return to Table of Contents

Reportable Disease List

Mississippi State Department of Health

List of Reportable Diseases and Conditions

Reporting Hotline: 1-800-556-0003

Monday - Friday, 8:00 am - 5:00 pm

To report inside Jackson telephone area or for consultative services

Monday - Friday, 8:00 am - 5:00 pm: (601) 576-7725

Phone

Fax

Epidemiology

(601) 576-7725

(601) 576-7497

STD/HIV

(601) 576-7723

TB

(601) 576-7700

Mail reports to: Office of Epidemiology, Mississippi State Department of Health, Post Office Box

1700, Jackson, Mississippi 39215-1700

Class 1A Conditions should be reported within 24 hours (nights, weekends and holidays by

calling: (601) 576-7400)

Class 1A: Diseases of major public health importance which shall be reported directly to the

Department of Health by telephone within 24 hours of first knowledge or suspicion.

Class 1A diseases and conditions are dictated by requiring an immediate public

health response. Laboratory directors have an obligation to report laboratory findings

for selected diseases (refer to Appendix B of the Rules and Regulations Governing

Reportable Diseases and Conditions).

Any Suspected Outbreak (including foodborne and waterborne outbreaks)

Anthrax

Hepatitis A

Rabies (human or animal)

Botulism (including foodborne,

Influenza-associated pediatric

Ricin intoxication (castor

infant or wound)

mortality (<18 years of age)

beans)

Brucellosis

Measles

Smallpox

Diphtheria

Melioidosis

Tuberculosis

Escherichia coli O157:H7 and any

Neisseria meningitidis Invasive

Tularemia

shiga toxin-producing E. coli

Disease

†‡

Typhus fever

(STEC)

Pertussis

Viral hemorrhagic fevers

Glanders

Plague

(filoviruses [e.g. Ebola,

Haemophilus influenzae Invasive

Poliomyelitis

Marburg] and

Disease

†‡

Psittacosis

arenaviruses [e.g.,Lassa,

Hemolytic uremic syndrome

Q fever

Machupo])

(HUS), post-diarrheal

Any unusual disease or manifestation of illness, including but not limited to the appearance of a novel

or previously controlled or eradicated infectious agent, or biological or chemical toxin.

†

Usually presents as meningitis or septicemia, or less commonly as cellulitis, epiglottitis, osteomyelitis,

pericarditis or septic arthritis.

‡

Specimen obtained from a normally sterile site.

8

Return to Table of Contents

Class 1B Conditions should be reported within 24 hours (within one business day)

Class 1B: Diseases of major public health importance which shall be reported directly to the

Department of Health by telephone within one business day after first knowledge or

suspicion. Class 1B diseases and conditions require individual case investigation, but

not an immediate public health response. Laboratory directors have an obligation to

report laboratory findings for selected diseases (refer to Appendix B of the Rules and

Regulations Governing Reportable Diseases and Conditions).

Arboviral infections including but

Chancroid

Syphilis (including

not limited to:

Cholera

congenital)

California encephalitis virus

Encephalitis (human)

Typhoid fever

Chikungunya virus

HIV infection, including AIDS

Varicella infection,

Dengue

Legionellosis

primary, in patients >15

Eastern equine encephalitis

Non-cholera Vibrio disease

years of age

virus

Staphylococcus aureus,

Yellow fever

LaCrosse virus

vancomycin resistant (VRSA) or

Western equine encephalitis

vancomycin intermediate (VISA)

virus

St. Louis encephalitis virus

West Nile virus

9

Return to Table of Contents

Class 2: Diseases or conditions of public health importance of which individual cases shall be

reported by mail, telephone, fax or electronically, within 1 week of diagnosis. In

outbreaks or other unusual circumstances they shall be reported the same as Class 1A.

Class 2 diseases and conditions are those for which an immediate public health

response is not needed for individual cases.

Chlamydia trachomatis, genital

HIV infection in pregnancy

Rocky Mountain spotted

infection

Listeriosis

fever

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease,

Lyme disease

Rubella (including

including new variant

Malaria

congenital)

Ehrlichiosis

Meningitis other than

Spinal cord injuries

Enterococcus, invasive infection

‡

,

Meningococcal or

Streptococcus

vancomycin resistant

Haemophilus influenzae

pneumoniae, invasive

Gonorrhea

Mumps

infection

‡

Hepatitis (acute, viral only) Note -

M. tuberculosis infection (positive

Tetanus

Hepatitis A requires Class 1A

TST or IGRA*)

Trichinosis

Report

Poisonings** (including elevated

Viral encephalitis in horses

Hepatitis B infection in pregnancy

blood lead levels***)

and ratites****

‡

Specimen obtained from a normally sterile site.

*TST- tuberculin skin test; IGRA- Interferon-Gamma Release Assay (to include size of TST in millimeters

and numerical results of IGRA testing).

**Reports for poisonings shall be made to Mississippi Poison Control Center, UMMC 1-800-222-1222.

***Elevated blood lead levels (as designated below) should be reported to the MSDH Lead Program

at (601) 576-7447.

Blood lead levels (venous) ≥5µg/dL in patients less than or equal to 6 years of age.

**** Except for rabies and equine encephalitis, diseases occurring in animals are not required to be

reported to the MSDH.

Class 3: Laboratory based surveillance. To be reported by laboratories only. Diseases or

conditions of public health importance of which individual laboratory findings shall be

reported by mail, telephone, fax or electronically within one week of completion of

laboratory tests (refer to Appendix B of the Rules and Regulations Governing

Reportable Diseases and Conditions).

All blood lead test results in

CD4 count and HIV viral load*

Hepatitis C infection

patients ≤6 years of age

Chagas Disease (American

Nontuberculous

Campylobacteriosis

trypanosomiasis)

mycobacterial disease

Carbepenam-resistant

Cryptosporidiosis

Salmonellosis

Enterobacteriaceae (CRE)

Hansen disease (Leprosy)

Shigellosis

Enterobacter species, E.coli or

Klebsiella species only

*HIV associated CD4 (T4) lymphocyte results of any value and HIV viral load results, both detectable

and undetectable.

10

Return to Table of Contents

Class 4: Diseases of public health importance for which immediate reporting is not necessary for

surveillance or control efforts. Diseases and conditions in this category shall be

reported to the Mississippi Cancer Registry within six months of the date of first contact

for the reportable condition.

The National Program of Cancer Registries at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

requires the collection of certain diseases and conditions. A comprehensive reportable list

including ICD9CM/ICD10CM codes is available on the Mississippi Cancer Registry website,

https://www.umc.edu/Administration/Outreach_Services/Mississippi_Cancer_Registry/Reportabl

e_Diseases.aspx.

Each record shall provide a minimum set of data items which meets the uniform standards

required by the National Program of Cancer Registries and documented in the North American

Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR).

11

Return to Table of Contents

Arboviral Infections (mosquito-borne)

Background

Arthropod-borne viral (arboviral) diseases in Mississippi are limited to a few types

transmitted by mosquitoes. In this state, there are four main types of arboviral infections

that have been reported: West Nile virus (WNV), St. Louis encephalitis (SLE), eastern

equine encephalitis (EEE), and LaCrosse encephalitis (LAC). WNV and SLE are members

of the Flavivirus genus, while EEE is an Alphavirus, and LAC is in the California virus group

of Bunyaviruses.

Infections do not always result in clinical disease. When illness occurs, symptoms can

range from a mild febrile illness to more severe cases of neuroinvasive disease with

encephalitis and/or meningitis. Neuroinvasive disease can result in long term residual

neurological deficits or death. The proportion of infected persons who develop

symptoms depends largely on the age of the persons and the particular virus involved.

Mosquito borne arboviral infections are typically more common in the warmer months

when mosquitoes are most active, but WNV cases have been reported year round. All

are transmitted by the bite of an infected mosquito, but the mosquito vectors and their

habitats differ. Infections are not transmitted by contact with an infected animal or

other person; humans and horses are “dead end” or incidental hosts. Rare instances of

WNV transmission have occurred through transplanted organs, blood transfusions, and

transplacentally.

Methods of Control

The methods of controlling mosquito-borne infections are essentially the same for all the

individual diseases. The best preventive strategy is to avoid contact with mosquitoes.

Reduce time spent outdoors, particularly in early morning and early evening hours

when mosquitoes are most active; wear light-colored long pants and long-sleeved

shirts; and apply mosquito repellant to exposed skin areas. Reduce mosquito breeding

areas around the home and workplace by eliminating standing or stagnant water.

Larvacides are effective when water cannot be easily drained.

Mosquito Surveillance

Mosquitoes are collected throughout the state for West Nile and other arboviral testing

to provide information regarding the burden and geographic distribution of infected

vectors. Mosquitoes are collected by local mosquito programs and MSDH personnel

and submitted as pools of 5-50 mosquitoes for testing. In 2013, 1044 mosquito pools

were submitted to MSDH PHL for WNV testing.

12

Return to Table of Contents

Arboviral Testing

The Public Health Laboratory (PHL) performs an arboviral panel consisting of IgM testing

for WNV and SLE, and, for patients less than 25 years of age, LAC IgM. Clinicians are

encouraged to call MSDH Epidemiology or the PHL for specifics and indications for

arboviral testing. In 2013, 1110 samples were submitted to the MSDH PHL for arboviral

testing.

Please refer to the individual disease summaries for information on and epidemiology of

each specific arbovirus.

Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE)

2013 Case Total 0 2013 rate/100,000 0.0

2012 Case Total

0

2012 rate/100,000

0.0

Clinical Features

Clinical illness is associated with symptoms that can range from a mild flu-like illness

(fever, headache, muscle aches) to seizures and encephalitis progressing to coma and

death. The case fatality rate is 30-50%. Fifty percent of those persons who recover from

severe illness will have permanent mild to severe neurological damage. Disease is more

common in young children and in persons over the age of 55.

Infectious Agent

Eastern equine encephalitis virus, a member of the genus Alphavirus.

Reservoir

Maintained in a bird-mosquito cycle. Humans and horses are incidental hosts.

Transmission

Through the bite of an infected mosquito, usually Coquilletidia perturbans. This

mosquito, known as the salt and pepper or freshwater marsh mosquito, breeds mainly in

marshy areas.

Incubation

3-10 days (generally within 7 days).

Reporting Classification

Class 1B.

13

Return to Table of Contents

Epidemiology and Trends

Human cases are relatively infrequent largely because primary transmission takes place

in and around marshy areas where human populations are generally limited. There

were no reported cases of EEE in Mississippi in 2013. The last two reported cases of EEE

occurred in October 2002.

Horses also become ill with EEE and are dead end hosts. Infected horses can serve as

sentinels for the presence of EEE, and can indicate an increased risk to humans. The

Mississippi Board of Animal Health (MBAH) reports equine infections to MSDH, and in

2013, 12 horses tested positive for EEE, which is a drastic decline from 32 in 2012. In 2013,

the EEE positive horses were reported from the following counties: Clarke (2), George

(1), Harrison (1), Jasper (1), Lamar (1), Lawrence (1), Madison (1), Neshoba (1), Pearl

River (1), Perry (1), and Wayne (1). All twelve of the positive horses were located in the

lower half of the state, with 50% (6) located in Districts VIII and IX.

LaCrosse Encephalitis

2013 Case Total 3 2013 rate/100,000 0.1

2012 Case Total

1 2012 rate/100,000 0.0

Clinical Features

Clinical illness occurs in about 15% of infections. Initial symptoms of LaCrosse

encephalitis infection include fever, headache, nausea, vomiting and lethargy. More

severe symptoms usually occur in children under 16 and include seizures, coma, and

paralysis. The case fatality rate for clinical cases of LaCrosse encephalitis is about 1%.

Infectious Agent

LaCrosse encephalitis virus, in the California serogroup of Bunyaviruses.

Reservoir

Chipmunks and squirrels.

Transmission

Through the bite of an infected Ochlerotatus triseriatus mosquito (commonly known as

the tree-hole mosquito). This mosquito is commonly associated with tree holes and

most transmission tends to occur in rural wooded areas. However, this species will also

breed in standing water in containers or tires around the home.

Incubation

7-14 days.

14

Return to Table of Contents

Reporting Classification

Class 1B.

Epidemiology and Trends

Reported LaCrosse encephalitis remains relatively rare in Mississippi, with 19 reported

cases since 1999. There were three reported cases of LaCrosse encephalitis in 2013; all

of the cases were 10 years old or younger.

Of the 19 total cases since 1999, 53% were in females. The ages ranged from 3 months

to 78 years of age, with 95% of the cases under the age of 15 and a median age of 6

years.

Another Bunyavirus in the California group, Jamestown Canyon encephalitis virus, has

also been seen in Mississippi, with one reported case in 1993, one in 2006, and one in

2008. There were no reported cases of Jamestown Canyon encephalitis virus in 2013.

St. Louis Encephalitis

2013 Case Total 0 2013 rate/100,000 0.0

2012 Case Total

0 2012 rate/100,000 0.0

Clinical Features

Less than 1% of infections result in clinical illness. Individuals with mild illness often have

only a headache and fever. The more severe illness, meningoencephalitis, is marked

by headache, high fever, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors,

occasional convulsions (especially in infants) and spastic (but rarely flaccid) paralysis.

The mortality rate from St. Louis encephalitis (SLE) ranges from 5 to 30%, with higher rates

among the elderly.

Infectious Agent

St. Louis encephalitis virus, a member of the genus Flavivirus.

Reservoir

Maintained in a bird-mosquito cycle. Infection does not cause a high mortality in birds.

Transmission

Through the bite of an infected mosquito generally belonging to genus Culex (Culex

quinquefasciatus, Culex pipiens), the southern house mosquito. This mosquito breeds in

standing water high in organic materials, such as containers and septic ditches near

homes.

15

Return to Table of Contents

Incubation

5-15 days.

Reporting Classification

Class 1B.

Epidemiology and Trends

The number of reported SLE cases fluctuates annually. There were no cases reported in

2004, 2006, 2008 or 2010, but there were nine cases with one death reported in 2005,

and two reported cases in both 2007 and 2009. There were no deaths due to SLE in

2007 or 2009.

Mississippi had no reported cases of SLE in 2013.

West Nile Virus

2013 Case Total 45 2013 rate/100,000 1.5

2012 Case Total

247

2012 rate/100,000

8.3

Clinical Features

Clinical illness occurs in approximately 20% of infected individuals. Most with clinical

manifestations will develop the milder West Nile fever, which includes fever, headache,

fatigue, and sometimes a transient rash. About 1 in 150 infected persons develop more

severe West Nile neuroinvasive disease ranging from meningitis to encephalitis.

Encephalitis is the most common form of severe illness and is usually associated with

altered consciousness that may progress to coma. Focal neurological deficits and

movement disorders may also occur. West Nile poliomyelitis, a flaccid paralysis

syndrome, is seen less frequently. The elderly and immunocompromised are at highest

risk of severe disease.

Infectious Agent

West Nile virus, a member of the genus Flavivirus.

Reservoir

WNV is maintained in a bird-mosquito cycle; it has been detected in more than 317

species of birds, particularly crows and jays.

Transmission

Primarily through the bite of an infected southern house mosquito (Culex

quinquefasciatus). This mosquito breeds in standing water with heavy organic matter.

16

Return to Table of Contents

Incubation

3-15 days.

Reporting Classification

Class 1B.

Epidemiology and Trends

In Mississippi, West Nile virus was first isolated in horses in 2001 followed by human

infections in 2002 with 192 cases reported. The years following saw a decrease in the

number of reported infections; however in 2006, there was a resurgence of 184 cases

(Figure 1). In 2013, there was a decrease in reported WNV cases from 247 cases in 2012

to 45 cases in 2013, leading to one of the lowest recorded rates in the past ten years.

There were five deaths associated with WNV in 2013. Of the 45 cases in 2013 of WNV,

58% were males and 42% were females.

Figure 1

WNV is now thought to be endemic in Mississippi, and the mosquito vector is present the

entire year. Human illness can occur year round, but is most prevalent from June to

October. July, August, and September are usually the peak months and 89% of the

cases over the past five years have occurred during these three months (Figure 2).

17

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 2

Of the 45 cases reported in 2013, 18 (40%) were classified as WNV fever and 27 (60%)

were neuroinvasive. The cases ranged in age from 3 to 91 years, with a median age of

54 years (Figure 3). The five reported deaths occurred in individuals over the age of 65,

with a median age of 84 years.

Figure 3

18

Return to Table of Contents

WNV infection can occur in any part of the state, and since 2001, activity (human

cases, positive mosquito pools, horses or birds) has been reported in every Mississippi

County except Issaquena. The cases in 2013 were spread throughout the state with the

most cases in any one county reported from Hinds County with 12 cases (Figure 4).

District VIII had the highest rate of WNV infection in 2013 with a rate of 5.2 cases per

100,000 residents (Figure 5).

A total of 43 mosquito pools tested positive for WNV in 2013. Horses may also become ill

with WNV and can act as sentinels for the presence of infected mosquitoes. The

Mississippi Board of Animal Health reports equine infections to MSDH. In 2013, 4 horses

tested positive for WNV throughout Mississippi.

Figure 4

West Nile Virus Cases by County, Mississippi, 2013

19

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 5

Campylobacteriosis

2013 Case Total 99 2013 rate/100,000 3.3

2012 Case Total

99

2012 rate/100,000

3.3

Clinical Features

Campylobacteriosis is a zoonotic bacterial disease of variable severity ranging from

asymptomatic infections to clinical illness with fever, diarrhea (may be bloody),

abdominal pain, and nausea and vomiting. Symptoms typically resolve after one

week, but may persist for weeks if untreated. Rare post-infectious syndromes include

reactive arthritis and Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS).

Infectious Agent

Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) causes most cases of diarrheal illness in humans.

Reservoir

Commonly present in cattle and poultry.

West Nile Virus Case Rates by District, Mississippi, 2013

20

Return to Table of Contents

Transmission

Transmission mainly occurs through ingestion of undercooked meat, usually poultry, but

occasionally contaminated food or water or raw milk. The number of organisms

required to cause infection is low.

Incubation

Average incubation is 2-5 days, with a range from 1-10 days.

Period of Communicability

Person to person transmission does not typically occur, though the infected individual

may shed organisms for up to 7 weeks without treatment.

Methods of Control

Disease prevention includes promotion of proper food handling, good hand washing,

particularly after handling raw meats, and after contact with feces of dogs and cats.

Pasteurizing milk and chlorinating water are also important. Symptomatic individuals

should be excluded from food handling or care of patients in hospitals or long term

care facilities.

Reporting Classification

Class 3.

Epidemiology and Trends

In 2013, there were 99 reported cases of campylobacteriosis in Mississippi; this was

comparable to the number of reported cases in 2012 and to the three-year average

(2010-2012) of 100 cases (Figure 6). The 2013 cases were not associated with any

reported outbreaks.

21

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 6

Campylobacter infections are typically more common in the warmer months, as are

many enteric illnesses; however in 2013, the reported number of cases remained stable

throughout the year (Figure 7). Children less than five years of age and adults 65 years

of age and older accounted for 42% of the overall cases in 2013 (Figure 8).

Figure 7

22

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 8

Chlamydia

2013 Case Total 17,355 2013 rate/100,000 580.2

2012 Case Total

22,992

2012 rate/100,000

770.3

Clinical Features

Chlamydia is a sexually transmitted bacterial infection causing urethritis in males and

cervicitis in females. Urethritis in males presents with scant to moderate mucopurulent

urethral discharge, urethral itching, and dysuria. Cervicitis presents as a mucopurulent

endocervical discharge, often with endocervical bleeding. The most significant

complications in women are pelvic inflammatory disease and chronic infections, both

of which increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy and infertility. Perinatal transmission of

chlamydia occurs when an infant is exposed to the infected cervix during birth resulting

in chlamydial pneumonia or conjunctivitis. Asymptomatic infections can occur in 1%-

25% of sexually active men and up to 70% of sexually active women.

Infectious Agent

Chlamydia trachomatis, an obligate intracellular bacteria. Immunotypes D through K

have been identified in 35-50% of nongonococcal urethritis.

Reservoir

Humans.

23

Return to Table of Contents

Transmission

Transmitted primarily through sexual contact.

Incubation

Incubation period is poorly defined, ranging from 7 to 14 days or longer.

Period of Communicability

Unknown.

Methods of Control

Prevention and control of chlamydia are based on behavior change, effective

treatment, and mechanical barriers. Condoms and diaphragms provide some degree

of protection from transmission or acquisition of chlamydia. Effective treatment of the

infected patient and their partners, from 60 days prior to the onset of symptoms, is

recommended.

Reporting Classification

Class 2.

Epidemiology and Trends

Chlamydia is the most frequently reported bacterial sexually transmitted disease in the

United States and in Mississippi. In 2013, the number of chlamydia cases in Mississippi

decreased 25% (from 22,992 to 17,355 cases), resulting in a case rate of 580.2 per

100,000 population (Figure 9). The 2013 case count and rate of chlamydia was the

lowest in Mississippi since 2003. The Mississippi rate has been above the national rate for

several years. In 2013, Mississippi had the fifth highest case rate of chlamydia in the

United States.

24

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 9

Chlamydia was reported in every public health district, with the highest incidence

noted in Public Health District III (Figure 10).

Figure 10

Chlamydia infections were reported over a range of age groups, but the largest

proportion was reported among 15-24 year olds, accounting for 74% of the reported

cases (Figure 11). African Americans accounted for 82% of the reported cases in which

Chlamydia Incidence by Public Health District, Mississippi, 2013

District

Cases

Rate*

I

1,999

617.7

II

1,606

436.2

III

2,256

1,069.5

IV

1,472

598.9

V

4,021

628.3

VI

1,592

656.5

VII

947

549.9

VIII

1,480

478.5

IX

1,982

414.0

Statewide

17,355

580.2

*per 100,000 population

25

Return to Table of Contents

race was known (Figure 12). In 2013, the rate of chlamydia infections for African

Americans (1,029.5 per 100,000) was eight times the rate for whites (125.0 per 100,000).

Figure 11

Figure 12

26

Return to Table of Contents

Cryptosporidiosis

2013 Case Total 48 2013 rate/100,000 1.6

2012 Case Total 40 2012 rate/100,000 1.3

Clinical Features

A parasitic infection characterized by profuse, watery diarrhea associated with

abdominal pain. Less frequent symptoms include anorexia, weight loss, fever, and

nausea and vomiting. Symptoms often wax and wane and but generally disappear in

30 days or less in healthy people. Asymptomatic infections do occur and can serve as

a source of infection to others. The disease may be prolonged and fulminant in

immunodeficient individuals unable to clear the parasite. Children under 2, animal

handlers, travelers, men who have sex with men, and close personal contacts of

infected individuals are more prone to infection.

Infectious Agent

Cryptosporidium parvum, a coccidian protozoan, is associated with human infection.

Reservoir

Humans, cattle and other domesticated animals.

Transmission

Transmission is fecal-oral, which includes person-to-person, animal-to-person,

waterborne (including recreational use of water) and foodborne transmission. Oocysts

are highly resistant to chemicals used to purify drinking water and recreational water

(swimming pools, water parks). The infectious dose can be as low as 10 organisms.

Incubation

1 to 12 days (average 7 days).

Period of Communicability

As long as oocysts are present in the stool. Oocysts may be shed in the stool from the

onset of symptoms to several weeks after symptoms resolve.

Methods of Control

Education of the public regarding appropriate personal hygiene, including

handwashing. Symptomatic individuals with a diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis should not

use public recreational water (e.g., swimming pools, lakes, ponds) while they have

diarrhea and for at least 2 weeks after symptoms resolve. It is recommended that

infected individuals be restricted from handling food, and symptomatic children be

27

Return to Table of Contents

restricted from attending daycare until free of diarrhea. Prompt investigation of

common food or waterborne outbreaks is important for disease control and prevention.

Reporting Classification

Class 3.

Epidemiology and Trends

There were 48 reported cases of cryptosporidiosis in 2013 (Figure 13). This is comparable

to the 40 cases reported in 2012, but higher than the three year average of 38 cases

from 2010 to 2012. There were no common source outbreaks identified in 2013.

Figure 13

E. coli O157:H7/ STEC / HUS

2013 Case Total 30 2013 rate/100,000 1.0

2012 Case Total 31 2012 rate/100,000 1.0

Clinical Features

Escherichia coli (E. coli) O157:H7 is the most virulent serotype of the Shiga toxin-

producing E. coli (STEC), and is associated with diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, hemolytic-

uremic syndrome (HUS), and post-diarrheal thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

(TTP). Symptoms often begin as nonbloody diarrhea but can progress to diarrhea with

28

Return to Table of Contents

occult or visible blood. Severe abdominal pain is typical, and fever is usually absent.

The very young and the elderly are more likely to develop severe illness and HUS,

defined as microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute renal

dysfunction. HUS is a complication in about 8% of E. coli O157:H7 infections. Supportive

care is recommended as antibiotic use may increase the risk of progression to HUS.

Other serotypes of E. coli are capable of producing Shiga toxins (STEC) that can lead to

illness and HUS.

Infectious Agent

E. coli are gram negative bacilli. E. coli O157:H7 is thought to cause more than 90% of

all diarrhea-associated HUS. Other non-O157 STEC serogroups include O26, O111, and

O103.

Reservoir

Cattle, to a lesser extent other animals, including sheep, deer, and other ruminants.

Humans may also serve as a reservoir for person-to-person transmission.

Transmission

Mainly through ingestion of food contaminated with ruminant feces, usually

inadequately cooked hamburgers; also contaminated produce or unpasteurized milk.

Direct person-to-person transmission can occur in group settings. Waterborne

transmission occurs both from contaminated drinking water and from recreational

waters.

Incubation

2-10 days, with a median of 3-4 days.

Period of Communicability

Duration of excretion is typically 1 week or less in adults but can be up to 3 weeks in

one-third of children. Prolonged carriage is uncommon.

Methods of Control

Education regarding proper food preparation and handling and good hand hygiene is

essential in prevention and control. Pasteurization of milk and juice is important.

MSDH investigates all reported cases of HUS and E. coli O157:H7 infections. All isolates

should be submitted to the Public Health Laboratory (PHL) for molecular subtyping, or

DNA “fingerprinting”, with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). Isolate information is

submitted to a national tracking system (PulseNet), a network of public health and food

regulatory agencies coordinated by the CDC. This system facilitates early detection of

29

Return to Table of Contents

common source outbreaks, even if the affected persons are geographically far apart,

and assists in rapidly identifying the source of outbreaks.

Reporting Classification

Class1A (includes E. coli O157:H7, non O157:H7 STEC and post-diarrheal HUS).

Epidemiology and Trends

In Mississippi, all E. coli O157:H7 infections, non O157:H7 STEC infections (added to the

List of Reportable Diseases and conditions in late 2010) and cases of post-diarrheal HUS

are reportable. In 2013 there were 30 cases reported to MSDH; 11 E. coli O157:H7 and 19

non O157:H7 STEC. This was comparable to the 31 reported cases in 2012 (Figure 14).

The 19 non O157:H7 STEC cases were due to serogroups O103 (3), O26 (4), O111 (4),

and O121 (1). The serogroups of the remaining seven STEC cases were unknown. One of

the E. coli O157:H7 cases also developed HUS. There were no deaths reported in

Mississippi in 2013.

Figure 14

*U.S. rate includes E. coli O157:H7; shiga toxin positive, serogroup non-O157; and shiga toxin positive, not serogrouped.

**Mississippi rate includes E. coli O157:H7; shiga toxin positive, serogroup non-O157; shiga toxin positive, not serogrouped,

and post-diarrheal HUS.

The 2013 E. coli O157:H7/STEC/HUS cases ranged in age from 14 months to 73 years with

a median of 10.5 years of age. Of the 61 cases of E. coli O157:H7/STEC/HUS that were

reported to MSDH in 2012 and 2013, 46% occurred in children less than 10 years of age

30

Return to Table of Contents

(Figure 15). Children and the elderly are at higher risk for the development of severe

illness and HUS as a result of infection.

Districts I, VIII, and IX experienced the highest rates of E. coli O157:H7 and non-O157:H7

STEC cases, with rates of 1.85, 2.26, and 1.46 cases per 100,000 residents, respectively.

Figure 15

There was one outbreak reported by the CDC in March 2013. This included 35 cases in

19 states, one case being in Mississippi. The STEC strain O121 was identified as the

infectious agent and frozen food products were found to be the source of infection.

There were two other outbreaks in Mississippi. In May 2013, an outbreak of E. coli O26

was identified with 23 cases across 11 states, with one in Mississippi. Another outbreak

occurred in June 2013, when a child was infected with E. coli O111 while at a camp in

Missouri.

Gonorrhea

2013 Case Total 5,090 2013 rate/100,000 170.2

2012 Case Total 6,860 2012 rate/100,000 229.8

Clinical Features

Gonnorhea is a sexually transmitted bacterial infection that primarily targets the

urogenital tract leading to urethritis in males and cervicitis in females. Other less

common sites of infection include the pharynx, rectum, conjunctiva, and blood.

31

Return to Table of Contents

Urethritis presents with mucopurulent discharge and dysuria, while cervicitis often

presents with vaginal discharge and postcoital bleeding. Asymptomatic infections do

occur.

Complications associated with gonorrhea infection in males include epididymitis, penile

lymphangitis, penile edema, and urethral strictures. The primary complication

associated with gonorrhea infection in females is pelvic inflammatory disease, which

produces symptoms of lower abdominal pain, cervical discharge, and cervical motion

pain. Pregnant women infected with gonorrhea may transmit the infection to their

infants during a vaginal delivery. Infected infants can develop conjunctivitis leading to

blindness if not rapidly and adequately treated. Septicemia can also occur in infected

infants.

Infectious Agent

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, an intracellular gram-negative diplococcus.

Reservoir

Humans.

Transmission

Gonorrhea is transmitted primarily by sexual contact, but transmission to an infant

delivered through an infected cervical canal also occurs.

Incubation

In males the incubation period is primarily 2-5 days, but may be 10 days or longer. In

females it is more unpredictable, but most develop symptoms less than 10 days after

exposure.

Period of Communicability

In untreated individuals, communicability can last for months; but if an effective

treatment is provided communicability ends within hours.

Methods of Control

Prevention and control of gonorrhea are based on education, effective treatment, and

mechanical barriers. Condoms and diaphragms provide some degree of protection

from transmission or acquisition of gonorrhea. Effective treatment of the infected

patient and their partners from 60 days prior to the onset of symptoms is recommended.

Reporting Classification

Class 2.

32

Return to Table of Contents

Epidemiology and Trends

Gonorrhea is the second most commonly reported notifiable disease in the United

States. From 2007 through 2011 there was a steady decline in the rate and number of

cases of gonorrhea in Mississippi. The number of cases during that time period

decreased from 8,163 cases in 2007 to 5,806 cases in 2011, representing a 29%

decrease. From 2011 to 2012, reported cases of gonorrhea increased 18% (from 5,806 to

6,860 cases); however in 2013, reported cases decreased 26% to 5,090 cases (Figure

16). In 2013, Mississippi had the third highest case rate of gonorrhea in the United States.

Figure 16

Gonorrhea was reported in every public health district, with the highest incidence

noted in Public Health District III (Figure 17).

33

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 17

Although the disease impacted individuals across all age groups, 66% of reported cases

were among 15-24 year olds (Figure 18). African Americans accounted for 89% of the

reported cases in which race was known (Figure 19). In 2013, the rate of gonorrhea

infections for African Americans (343.1 per 100,000) was fifteen times the rate of whites

(23.0 per 100,000).

Figure 18

Gonorrhea Incidence by Public Health District, Mississippi, 2013

District

Cases

Rate*

I

498

153.9

II

380

103.2

III

573

271.6

IV

436

177.4

V

1523

238.0

VI

403

166.2

VII

229

133.0

VIII

480

155.2

IX

568

118.6

Statewide

5,090

170.2

*per 100,000 population

34

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 19

Haemophilus influenzae, type b

2013 Case Total 1 2013 rate/100,000 0.0

2012 Case Total

0

2012 rate/100,000

0.0

Clinical Features

Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae) is an invasive bacterial disease, particularly

among infants, that can affect many organ systems. There are six identifiable types of

H. influenzae bacteria (a through f). Type b (Hib) is the most pathogenic and is

responsible for the majority of invasive infections. Meningitis is the most common

manifestation of invasive disease. Epiglottitis, pneumonia, septic arthritis, and

septicemia are other forms of invasive disease. Hib meningitis presents with fever,

decreased mental status and nuchal rigidity. Neurologic sequelae can occur in 15-30%

of survivors, with hearing impairment as the most common. Case fatality rate is 2-5%

even with antimicrobial therapy. Peak incidence is usually in infants 6-12 months of age;

Hib disease rarely occurs beyond 5 years of age. In the prevaccine era, meningitis

accounted for 50-60% of all cases of invasive disease. Since the late 1980’s, with the

licensure of Hib conjugate vaccines, Hib meningitis has essentially disappeared in the

U.S.

Infectious Agent

Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae), a gram-negative encapsulated bacterium.

Serotypes include a through f.

35

Return to Table of Contents

Reservoir

Humans, asymptomatic carriers.

Transmission

Respiratory droplets and contact with nasopharyngeal secretions during the infectious

period.

Incubation

Uncertain; probably short, 2-4 days.

Period of Communicability

As long as organisms are present; up to 24-48 hours after starting antimicrobial therapy.

Methods of Control

Two Hib conjugate vaccines are licensed for routine childhood vaccination. The

number of doses in the primary series is dependent on the type of vaccine used. A

primary series of PRP-OMP (PedvaxHIB®) vaccine is two total doses, at 2 and 4 months

of age; the primary series with PRP-T (ActHIB®) requires three total doses, given at 2, 4

and 6 months of age. A booster dose at 12-15 months of age is recommended

regardless of which vaccine is used for the primary series. Vaccination with Hib

containing vaccines may decrease the carriage rate, decreasing the chances of

infection in unvaccinated in children. Immunization is not recommended for children

over 5 years of age.

The Mississippi State Department of Health (MSDH) investigates all reports of suspected

or confirmed invasive disease due to H. influenzae to determine serotype and the need

for prophylactic antibiotics for contacts. For Hib cases MSDH provides prophylactic

antibiotics (rifampin) for all household contacts with one or more children under one

year of age or in households with children 1-3 years old who are inadequately

immunized. Although the protection of contacts is only recommended after exposure

to cases of Hib disease, contacts are often treated before the isolate’s serotype is

known in order to facilitate rapid provision of post-exposure prophylaxis . MSDH requests

that all H. influenzae isolates be sent to the Public Health Laboratory (PHL) for

serotyping.

Reporting Classification

Class 1A.

Epidemiology and Trends

Prior to the development and widespread use of Hib conjugate vaccines in the late

1980’s and early 1990’s, Hib was the most common cause of bacterial meningitis in

children < 5 years of age. In Mississippi, conjugate vaccine was first offered to 18 month

olds in 1989, to 15 month olds in 1990, and as a primary series, starting at 2 months of

age, with a 12-15 month booster, in January 1991. With the institution of vaccination, the

36

Return to Table of Contents

number of reported cases of invasive disease due to Hib dropped from 82 in 1989, to 5

by 1994. There have been fewer than 5 cases of Hib per year since 1995.

There were 31 cases of H. influenzae reported in 2013, with only one case confirmed as

type b. This case presented as septicemia in an 81 year old female. There were three

deaths associated with invasive H. influenzae infection, all of which were over the age

of 60. Districts I and V had the highest rates of H. influenzae infection of 1.85 and 1.72

per 100,000 residents, respectively. Of the overall cases, 26 presented as septicemia

(84%), three presented as meningitis (10%) and two presented as other invasive

infections (6%). Ages ranged from newborn to 88 years, with a median of 69 years. The

invasive H. influenzae cases were identified as being type b (3%), type f (3%), not type b

(71%), not typed (3%) and unknown (19%).

Hepatitis A

2013 Case Total 5 2013 rate/100,000 0.2

2012 Case Total

11

2012 rate/100,000

0.4

Clinical Features

Hepatitis A is a viral illness with an abrupt onset of fever, malaise, anorexia, nausea,

vomiting, and abdominal pain, followed by jaundice in a few days. The disease varies

in intensity from a mild illness of 1-2 weeks, to a severe disease lasting several months.

Most cases among children are asymptomatic and the severity of illness increases with

age; the case fatality rate is low—0.1%-0.3%. No chronic infection occurs.

Infectious Agent

Hepatitis A virus (HAV), an RNA virus.

Reservoir

Humans, rarely chimpanzees and other primates.

Transmission

Transmission occurs through the fecal-oral route either by person to person contact or

ingestion of contaminated food or water. Common source outbreaks may be related

to infected food handlers. Many younger children are asymptomatic, but shed virus

and are often sources of additional cases.

Incubation

Average 28-30 days, (range 15-50 days).

37

Return to Table of Contents

Period of Communicability

Infected persons are most likely to transmit HAV 1-2 weeks before the onset of

symptoms and in the first few days after the onset of jaundice, when viral shedding in

the stool is at its highest. The risk of transmission then decreases and becomes minimal

after the first week of jaundice.

Methods of Control

In the prevaccine era, hygienic measures and post-exposure immune globulin were the

primary means of preventing infection. Vaccine was first introduced in 1995, and

following successful vaccination programs in high incidence areas, the Advisory

Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended routine vaccination for all

children in 2005. Children aged 12-23 months of age should receive one dose of

hepatitis A vaccine followed by a booster 6-18 months later, with catch up vaccination

for children not vaccinated by 2 years of age.

Post-exposure prophylaxis is recommended within two weeks of exposure for all

susceptible individuals who are close personal contacts to the case or who attend

daycare with infected individuals, or are exposed to hepatitis A virus through common

source outbreaks. Hepatitis A vaccine (with completion of the series) is recommended

for post-exposure prophylaxis for all healthy persons aged 12 months to 40 years.

Immune globulin should be considered for children less than 12 months of age, adults

over 40 years of age, and those in whom vaccination is contraindicated. Use of both

simultaneously can be considered with higher risk exposures. Post-exposure prophylaxis

is not generally indicated for healthcare workers who care for patients infected with

hepatitis A unless epidemiological investigation indicates ongoing transmission in the

facility.

Reporting Classification

Class 1A.

Epidemiology and Trends

The rate of hepatitis A in Mississippi has been below the national average for more than

a decade. In 2013, there were only five cases of acute hepatitis A reported in

Mississippi; less than both the eleven cases reported in 2012 and the three year (2010-

2012) average of six annual cases (Figure 20). No common source exposures or

outbreaks of hepatitis A were reported in 2013.

38

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 20

Hepatitis B, acute

2013 Case Total 54 2013 rate/100,000 1.8

2012 Case Total

78

2012 rate/100,000

2.6

Clinical Features

An acute viral illness characterized by the insidious onset of anorexia, abdominal

discomfort, nausea and vomiting. Clinical illness is often unrecognized because

jaundice occurs in only 30-50% of adults and less than 10% of children. Approximately

5% of all acute cases progress to chronic infection. Younger age at infection is a risk

factor for becoming a chronic carrier with 90% of perinatally infected infants becoming

chronic carriers. Chronic cases may have no evidence of liver disease, or may develop

clinical illness ranging from chronic hepatitis, to cirrhosis, liver failure or liver cancer.

Hepatitis B infections are the cause of up to 80% of hepatocellular carcinomas

worldwide.

Infectious Agent

Hepatitis B virus, a hepadnavirus.

Reservoir

Humans.

39

Return to Table of Contents

Transmission

Transmission occurs through parenteral or mucosal exposure to body fluids of hepatitis B

surface antigen (HBsAg) positive persons, such as through perinatal exposure, contact

with contaminated needles, or sexual contact. Blood and blood products, saliva,

semen and vaginal secretions are known to be infectious. The three main groups at risk

for hepatitis B infection are heterosexuals with infected or multiple partners, injection-

drug users, and men who have sex with men.

Incubation

45-180 days, average 60-90 days.

Period of Communicability

As long as HBsAg is present in blood. In acute infections, surface Ag can be present 1-2

months after the onset of symptoms.

Methods of Control

Routine hepatitis B vaccination series is recommended for all children beginning at

birth, with catch-up at 11-12 years of age if not previously vaccinated. The usual three

dose schedule is 0, 1-2, and 6-18 months. Vaccination is also recommended for high

risk groups, including those with occupational exposure, household and sexual contacts

of HBsAg positive individuals (both acute and chronic infections), and injection drug

users.

Transmission of hepatitis B can be interrupted by identification of susceptible contacts

and HBsAg positive pregnancies, and the timely use of post-exposure prophylaxis with

vaccine and/or immune globulin.

Perinatal transmission is very efficient in the absence of post-exposure prophylaxis, with

an infection rate of 70-90% if the mother is both HBsAg and hepatitis B e antigen

(HBeAg) positive. The risk of perinatal transmission is about 10% if the mother is only

HBsAg positive. Post-exposure prophylaxis, consisting of hepatitis B immune globulin

and vaccine, is highly effective in preventing hepatitis B vertical transmission, therefore,

testing of all pregnant women for HBsAg is recommended with each pregnancy. MSDH,

through the Perinatal Hepatitis B Program, tracks HBsAg positive pregnant women,

provides prenatal HBsAg testing information to the delivery hospitals when available,

and monitors infants born to infected mothers to confirm completion of the vaccine

series by 6 months of age, and then tests for post-vaccine response and for possible

seroconversion at 9-12 months of age. As an addition to the existing reporting

requirement of acute hepatitis B infection, in 2011 hepatitis B infection in pregnancy

was added to the list of reportable diseases. This addition was made to facilitate

40

Return to Table of Contents

identification of hepatitis B infected women and ensure the provision of appropriate

vaccination for the affected infant.

Reporting Classification

Class 2; any acute hepatitis B infection and any hepatitis B infection in pregnancy

Epidemiology and Trends

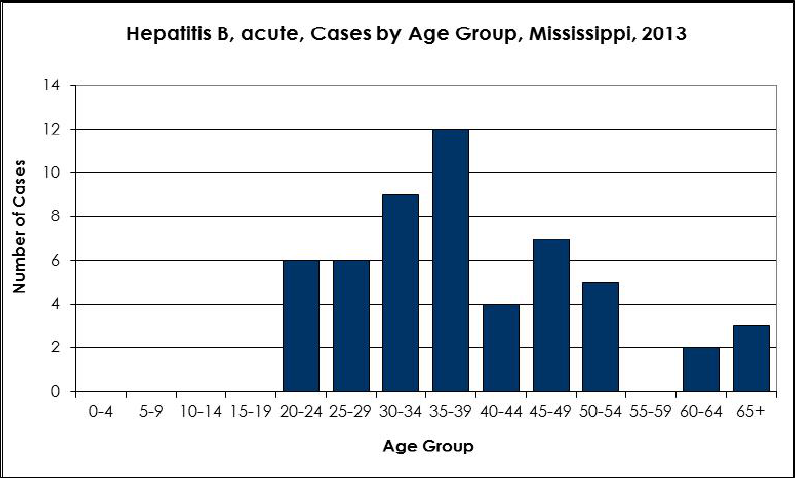

In 2013, 54 cases of acute hepatitis B were reported. This was lower than the 78

reported cases in 2012, but was comparable to the three year average (2010-2012) of

57 annual cases (Figure 21). Thirty-three (61%) of the 54 reported cases occurred in

individuals aged 20-39 years. Overall, the cases ranged in age from 21 years to 74

years old, with a median age of 37 years (Figure 22).

Figure 21

41

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 22

A comprehensive strategy to eliminate hepatitis B virus transmission was recommended

in 1991. The strategy includes prenatal testing of pregnant women for Hepatitis B

surface antigen (HBsAg) to identify newborns that require immunoprophylaxis,

identification of household contacts who should be vaccinated, the routine

vaccination of infants, the vaccination of adolescents, and the vaccination of adults at

high risk for infection.

In 2013, 76 HBsAg positive pregnant women were reported to the Perinatal Hepatitis B

Prevention Program (Figure 23). This is lower than both the 100 reported in 2012 and the

three year average (2010 – 2012) of 100. There were no reported cases of HBsAg

positive infants born to HBsAg positive mothers in 2013. The last cases of perinatal

transmission occurred in 2007, when two cases were reported.

42

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 23

HIV Disease

2013 Case Total 556 2013 rate/100,000 18.6

2012 Case Total

547

2012 rate/100,000

18.3

Clinical Features

The clinical spectrum of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection varies from

asymptomatic infections to advanced immunodeficiency with opportunistic

complications. One half to two thirds of recently infected individuals have

manifestations of an infectious mononucleosis-like syndrome in the acute stage. Fever,

sweats, malaise, myalgia, anorexia, nausea, diarrhea, and non-exudative pharyngitis

are prominent symptoms in this stage. Constitutional symptoms of fatigue and wasting

may occur in the early months or years before opportunistic disease is diagnosed. Over

time, HIV can weaken the immune system, lowering the total CD4 count and leading to

opportunistic infections and the diagnosis of Acquired Immunodeficiency syndrome

(AIDS).

Infectious Agent

Human immunodeficiency virus is a retrovirus with two known types, HIV-1 and HIV-2.

These two types are serologically distinct and have a different geographical

distribution, with HIV-1 being primarily responsible for the global pandemic and the

more pathogenic of the two.

43

Return to Table of Contents

Reservoir

Humans.

Transmission

HIV infection can be transmitted from person to person during sexual contact, by blood

product transfusion, sharing contaminated needles or infected tissue or organ

transplant. Breast feeding is also a known vehicle of mother to infant transmission of HIV.

Without appropriate prenatal treatment, 15-30% of infants born to HIV positive mothers

are infected through maternal fetal transmission. Transmission by contact with body

secretions like urine, saliva, tears or bronchial secretions has not been recorded.

Incubation

The time from infection to the detection of antibodies to HIV is usually less than one

month. The period from the time of infection to the development of AIDS ranges from 1

year up to 15 years or longer. The availability of effective anti-HIV therapy has greatly

reduced the development of AIDS in the U.S.

Period of Communicability

Individuals become infectious shortly after infection and remain infectious throughout

the course of their lives, however, successful therapy with antiretroviral drugs can lower

the viral load in blood, semen and vaginal secretions to undetectable levels,

substantially decreasing the transmission probability of HIV.

Methods of Control

Abstinence is the only sure way to avoid sexual HIV transmission; otherwise mutual

monogamy with partners known to be uninfected and the use of latex condoms are

known to reduce the risk of infection. Confidential HIV testing and counseling and

testing of contacts, prenatal prevention by counseling and testing all pregnant women,

and early diagnosis and treatment with appropriate anti-retroviral therapy can reduce

transmission. Post-exposure prophylaxis for health care workers exposed to blood or

body fluids suspected to contain HIV is an important worksite preventive measure. In

recent years, a number of biomedical interventions including male circumcision, pre-

exposure, and post-exposure prophylaxis have proven to be effective in decreasing the

rate of acquisition of HIV among high risk individuals. MSDH performs contact

investigation, counseling and testing for each reported case of HIV infection in addition

to facilitating linkage to care of infected individuals.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, is a prevention option for those individuals at high risk

for HIV infection. Taken consistently, PrEP has been shown to substantially reduce the

risk of infection, especially if combined with condoms and other prevention methods.

44

Return to Table of Contents

Reporting Classifications

Class 1B; HIV infection-including AIDS

Class 3; CD4 count and HIV viral load.

Epidemiology and Trends

Both HIV infection and AIDS are reportable at the time of diagnosis, so many patients

may be reported twice (once at first diagnosis of HIV infection, and again when

developing an AIDS defining illness). The epidemiologic data that follows is regarding

the initial report of HIV disease, whether first diagnosed as HIV infection or AIDS. Over

the past few years, there has been little change in HIV disease trends. There were 556

cases of HIV disease reported in 2013 (Figure 24).

Figure 24

Individuals from every Public Health District were impacted by this disease. Public

Health District V reported the highest case rate statewide, followed by District III (Figure

25).

45

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 25

HIV disease was reported in all age groups, with 41% of the cases reported among 20-

29 year olds and 23% among 30 to 39 year olds (Figure 26). African Americans were

disproportionately impacted by HIV disease. In 2013, 78% of new cases were among

African Americans in which race was known (Figure 27).

Figure 26

HIV Disease Incidence by Public Health District, Mississippi, 2013

District

Cases

Rate*

I

57

17.6

II

41

11.1

III

51

24.2

IV

27

11.0

V

197

30.8

VI

35

14.4

VII

29

16.8

VIII

57

18.4

IX

62

13.0

Statewide

556

18.6

*per 100,000 population

46

Return to Table of Contents

Figure 27

There are a number of identifiable risk factors associated with HIV infection, including

male-to-male sexual contact (MSM), heterosexual contact (hetero), and injection drug

use (IDU)(Figure 28). Cases in persons with no reported exposure to HIV through any

routes listed in the hierarchy of transmission categories are classified as “no risk factor

reported or identified” or NIR. For the last several years, the percentage of cases

among individuals identifying themselves as MSM has steadily increased, from 36% in

2008 to 54% in 2013.

Figure 28

47

Return to Table of Contents

Additional References:

Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the

use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department

of Health and Human Services. Available at

https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for Prevention and

Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents.

MMWR 2009;58 (No. RR-4) April 10, 2009

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the Prevention and

Treatment of Opportunistic Infections Among HIV-Exposed and HIV-Infected

Children. MMWR 2009; 58 (No. RR-11) September 4, 2009

Influenza – 2013 – 2014 Season

Clinical Features

An acute viral infection of the respiratory tract characterized by sudden onset of fever,

often with chills, headache, malaise, diffuse myalgia, and nonproductive cough. The

highest risks for complications from seasonal influenza are in persons aged 65 years and

older, young children, pregnant and postpartum women, and persons at any age with

chronic underlying illnesses. Pneumonia due to secondary bacterial infections is the

most common complication of influenza. Estimated influenza deaths range from a low

of 3,000 to a high of 49,000 per year in the United States.

Infectious Agent

Influenza is caused by an RNA virus. Each season both influenza A and B virus strains

circulate and cause illness but there is usually one predominant type or subtype of

influenza virus that causes the majority of infections.

Reservoir

Humans are the reservoir for seasonal influenza. Wild aquatic bird, domestic poultry and

domestic pigs can serve as reservoirs for emerging variant influenza strains.

Transmission

Transmission occurs person to person by direct or indirect contact with virus laden

droplets or respiratory secretions. Transmission of variant strains is usually the result of

direct contact with an infected animal, such as pigs or domestic poultry.

48

Return to Table of Contents

Incubation

The incubation period usually is 1 to 4 days, with a mean of 2 days.

Period of Communicability

From 1 day before clinical onset through 3-5 days from clinical onset in adults; and up

to 7-10 days from clinical onset in young children.

Methods of Control

Routine annual influenza vaccination is recommended for all persons aged ≥6 months,

and is the single most effective method for the prevention of infection. Additionally,

basic personal hygiene, including handwashing, and respiratory etiquette should be

reinforced.

Antivirals can also be used to prevent and treat influenza. The neuraminidase inhibitors

(oseltamivir and zanamivir) are effective against all forms of influenza. Sporadic

resistance to oseltamivir has been identified in some influenza strains (influenza A H1N1),

however neuraminidase inhibitors are still recommended for the treatment of influenza

A (H1N1) and A (H3N2) and influenza B virus infections. Treatment with antivirals within

the first 48 hours of can be effective in reducing the duration of illness, and is

recommended for individuals who are hospitalized or at higher risk of severe

complications from influenza infections. Adamantanes (amantadine and rimantadine)

are not effective against influenza B viruses and are not recommended for influenza A

viruses due to high levels of resistance.

For the most current guidelines available at the date of this publication, please see the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Recommendations and Reports,

“Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2016-2017”. MMWR

65(No. RR5); August 26, 2016, available online at

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/pdfs/rr6505.pdf

For guidelines on the use of antivirals see the CDC website at:

http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/antiviral-use-influenza.htm

and the CDC

report “Antiviral Agents for the Treatment and Chemoprophylaxis of Influenza”

available at:

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6001a1.htm

Reporting Classification

Class 1A: Influenza-associated pediatric deaths (<18 years of age).

Epidemiology and Trends

A typical influenza season usually peaks anywhere from December through March but

influenza activity can occur earlier or later. The risk of complications depends on many

49

Return to Table of Contents

factors, including age and underlying medical conditions. Vaccination status and the

match of vaccine to circulating viruses affect both the susceptibility to infection and

the possibility of complications. Outbreaks can occur in group settings, such as nursing

homes.

MSDH monitors seasonal influenza activity statewide through an active syndromic

surveillance program reported by sentinel providers. In the 2013 – 2014 influenza

season, 47 sentinel providers in 37 counties were enrolled in this system, representing

hospital emergency departments, urgent care and primary care clinics, and college

and university student health centers. These providers reported weekly numbers of non-

trauma patient visits consistent with an influenza-like illness (ILI), defined as fever >100ºF

and cough and/or sore throat in the absence of a known cause other than influenza.

MSDH uses this information to estimate the magnitude of the state’s weekly influenza

activity. These data are also used to estimate the geographic spread of influenza

within the state, ranging from no activity to widespread activity. This terminology

represents a geographic estimate rather than an indication of severity of the season. ILI

providers are also supplied with kits for PCR influenza testing at the Public Health

Laboratory (PHL).

Influenza activity peaked in late December in the US and influenza A (pH1N1) was the

predominant virus in the US, although influenza B activity increased later in the influenza

season. The 2013 – 2014 influenza season was the first pH1N1-predominant season since

the 2009 pH1N1 pandemic. Also of significance for the 2013 – 2014 was the higher than

expected hospitalization rates among those aged 50 to 64 years. This age group had

the second highest hospitalization rate, just behind those aged 65 years and older. The

CDC surmised that the increased hospitalization rates were likely due to several factors,

including lack of cross-protective immunity to pH1N1 and lower influenza vaccination

coverage in this age group.

In Mississippi, influenza activity also peaked in late December 2013 at 8.2%, which was

comparable to when the peak occurred during the previous season. The 2013 – 2014

season followed the same seasonal pattern as the two previous influenza seasons

(Figure 29). Early in the 2013 – 2014 season, the predominant virus identified in the PHL

was influenza A (pH1N1), although both influenza A (subtyped not performed) and

Influenza B isolates were identified later in the season (Figure 30). There was one

influenza-associated pediatric death reported in Mississippi in the 2013 – 2014 season.

The death occurred in a 17 month old.

During the 2013-2014 influenza season, MSDH began receiving reports of serious

complications associated with influenza infection, including deaths, in individuals less

than 65 years of age. In response to these reports, MSDH developed an enhanced

50

Return to Table of Contents

surveillance system to identify influenza deaths in hospitalized adults. Please see the

Special Reports section for a discussion of this enhanced surveillance activity.

Figure 29

Figure 30

51

Return to Table of Contents

Legionellosis

2013 Case Total 18 2013 rate/100,000 0.6

2012 Case Total 17 2012 rate/100,000 0.6

Clinical Features

Legionellosis is an acute bacterial infection that has two clinical syndromes;

Legionnaires’ disease and Pontiac fever. Both syndromes can present with fever,

headache, diarrhea and generalized myalgias. Those with Legionnaires’ disease

develop a non-productive cough and pneumonia that can be severe and progress to

respiratory failure. Even with improved diagnosis and treatment, the case fatality rate

for Legionnaires’ disease remains at approximately 15%. Pontiac fever is a self-limited

febrile illness that does not progress to pneumonia or death.

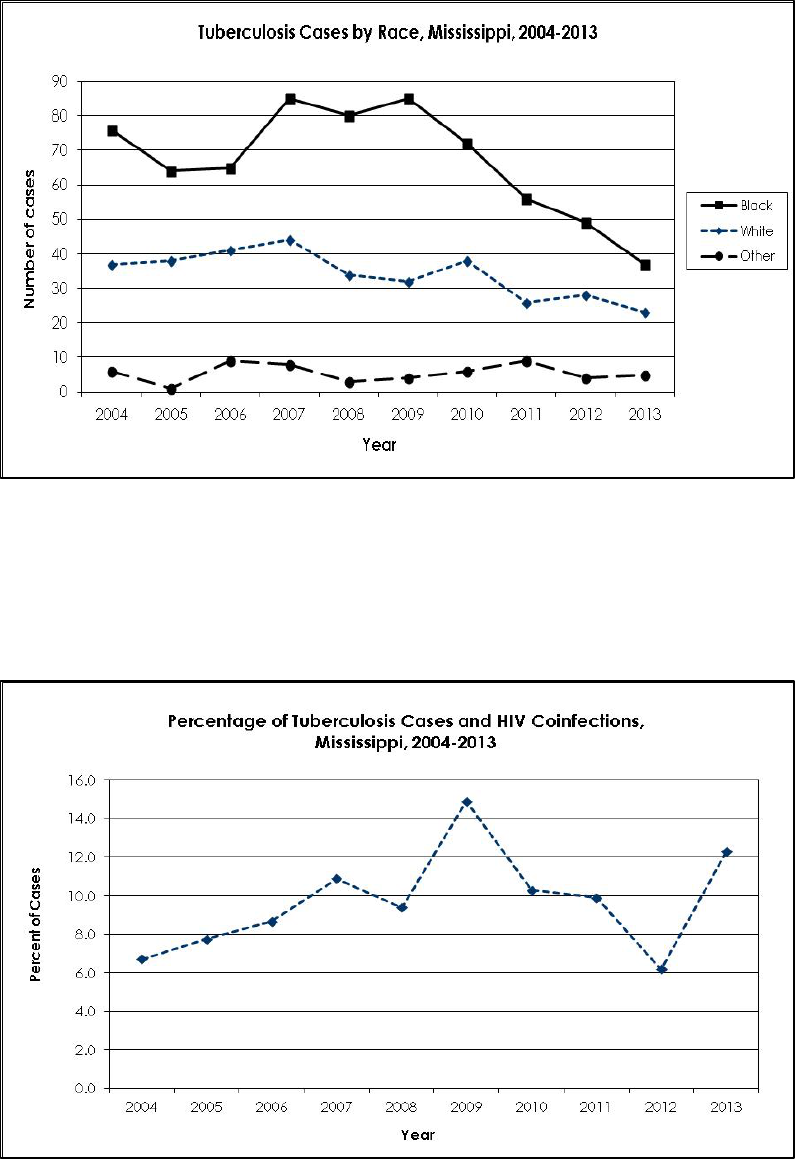

Infectious Agent