New Jersey

Hepatitis C Epidemiologic Profile

Issued July 2023

New Jersey Department of Health

COMMUNICABLE DISEASE SERVICE | INFECTIOUS AND ZOONOTIC DISEASE PROGRAM

Page | 1

CONTRIBUTORS

Author

Bernice Carr, MPH, MS

Epidemiologist, Communicable Disease Service,

Infectious and Zoonotic Disease Program,

Epidemiology, Environmental and Occupational

Health, New Jersey Department of Health

Fellow, Leading Epidemiologists Advancing

Data, Council of State and Territorial

Epidemiologists

Mentor

Daniel Church, MPH

Epidemiologist, Viral Hepatitis Coordinator, Division

of Epidemiology, Bureau of Infectious Disease and

Laboratory Sciences, Massachusetts Department of

Public Health

Contributors

Maryellen Wiggins MSN, RN, ACRN

Public Health Consultant, Hepatitis C Nurse

Stella Tsai, PhD, CIH

Research Scientist, Data Analyst Coordinator

Vibha Gujar, PhD, MS

Health Data Specialist

Mojisola Ojo, MPH

Epidemiologist

Communicable Disease Service, Infectious and

Zoonotic Disease Program, Epidemiology,

Environmental and Occupational Health, New Jersey

Department of Health

Editors

Edward Lifshitz, MD, FACP

Medical Director

Kim Cervantes, MA, MPH, CIC

Program Manager

Laura Taylor, PhD, MCHES

Viral Hepatitis Coordinator

Keerti Kalluru, BSPH

Public Health Associate

Callie Shane

Management Assistant

Communicable Disease Service, Infectious and Zoonotic

Disease Program, Epidemiology, Environmental and

Occupational Health, New Jersey Department of Health

Acknowledgments

Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, Leading Epidemiologists Advancing Data Program

New Jersey Viral Hepatitis Elimination Advisor Group

Page | 2

CONTENTS

CONTRIBUTORS ............................................................................................................................................................ 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 3

ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................................................ 4

BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................................... 5

New Jersey Geographical Distribution and Population Overview ............................................................................ 5

Social Characteristics/Social Determinants of Health............................................................................................... 6

VIRAL HEPATITIS SURVEILLANCE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY IN NEW JERSEY ....................................................................... 10

Testing for HCV Infection ........................................................................................................................................ 10

Scope of Hepatitis C Disease in New Jersey ............................................................................................................ 10

Acute Hepatitis C in New Jersey ............................................................................................................................. 10

Chronic Hepatitis C in New Jersey ............................................................................................................................ 15

Perinatal Hepatitis C ............................................................................................................................................... 15

Morbidity and Mortality ......................................................................................................................................... 17

VIRAL HEPATITIS IN SPECIAL POPULATIONS IN NEW JERSEY ....................................................................................... 21

HIV Co-infections .................................................................................................................................................... 21

Persons Who Use or Inject Drugs ........................................................................................................................... 21

Incarcerated individuals.......................................................................................................................................... 22

ADDRESSING VIRAL HEPATITIS IN NEW JERSEY ........................................................................................................... 24

Prevention and Education ...................................................................................................................................... 24

Hepatitis C Testing .................................................................................................................................................. 24

Hepatitis C Treatment ............................................................................................................................................ 25

Laboratory Based HCV Clearance Cascade ............................................................................................................. 26

SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................................. 27

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................................................... 28

APPENDIX .................................................................................................................................................................... 31

Page | 3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the most common types of viral hepatitis in the United States.

An estimated 2.4 million people in the United States were living with hepatitis C during 2013–

2016 (1). Hepatitis means inflammation of the liver. HCV does not only impact the liver but can

affect an individual’s overall health. HCV is transmitted by infected blood and blood products.

HCV may present as either an acute or chronic illness. The most common method of

transmission is intravenous drug use and the sharing of injecting equipment. People at greatest

risk for HCV include people who use or used injection drugs, who have HIV infection or other

comorbidities, certain occupations, and children born to mothers who have HCV.

HCV is one of the most frequently reported infectious diseases in the state of New Jersey. The

yearly overview of HCV in New Jersey includes:

• About 100 to 145 acute HCV infections reported

• An average of 6820 new chronic cases reported

• Based on reported cases, about 470 babies who were exposed to HCV

This HCV epidemiologic profile describes the burden of HCV on the population of New Jersey

over a five-year period, from 2016 through 2020. More specifically, the epidemiologic profile’s

three main purposes are to:

• Provide a description of HCV among the state’s population/subpopulations in terms

of sociodemographic, geographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics.

• Describe the status of persons with HCV infection and provide some understanding

of future HCV distribution.

• Identify characteristics of populations who are living with, or who are at high risk

for, HCV in defined geographic areas and who need prevention or care services.

This epidemiologic profile can serve as a valuable tool at the state and local levels to assist in

making hepatitis C related decisions around resource allocations for prevention and care

resources, planning and evaluation programs, and policymaking. Moreover, this profile can be

used to streamline the work of the New Jersey Department of Health (NJDOH) and its partners

who are involved in viral hepatitis elimination planning.

Page | 4

ABBREVIATIONS

AASLD: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

ACA: Affordable Care Act

ACS: American Community Survey

AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CDS: Communicable Disease Service within the NJDOH

CDRSS: Communicable Disease and Surveillance System

DAA: Direct Acting Antiviral

DMHAS: Division of Mental Health and Addiction Services

within the NJ Department of Human Services

EBC: Electronic Birth Registration

ELR: Electronic Laboratory Reporting

HCV: Hepatitis C Virus

HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus

ICD: International Classification of Diseases

IDSA: Infectious Diseases Society of America

IDU: Injection Drug Use

IZDP: Infectious and Zoonotic Disease Program

within the NJDOH

MMC: Medicaid Managed Care

MSM: Men Who Have Sex with Men

NCI: National Cancer Institute

NCHS: National Center for Health Statistics

NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

NJAC: New Jersey Administrative Code

NJDOH: New Jersey Department of Health

NNDSS: National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System

PWID: People Who Inject Drugs

PWUD: People Who Use Drugs

RNA: Ribonucleic Acid

STD: Sexually Transmitted Diseases

US: United States

Page | 5

BACKGROUND

New Jersey Geographical Distribution and Population Overview

New Jersey is in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It is about 150 miles long and 70

miles wide, comprising 8,722 square miles and includes urban, suburban, and rural areas. New

Jersey has a population of approximately nine million residents and borders two large

metropolitan areas, New York City and Philadelphia (Figure 1). It is the most densely populated

state in the United States and is composed of 21 counties and 564 municipalities. Hudson County

is the smallest county (46.19 square miles), and Burlington County is the largest (798.58 square

miles). The capital of New Jersey is the City of Trenton, located in Mercer County, which is also

the approximate geographic center of the state (2).

Figure 1: State of New Jersey counties and

transportation network

Source: State of New Jersey Profile

(mit2019_section4_State_Profile.pdf (nj.gov))

In 2018, the estimated population of New

Jersey was 8,908,520 with 51% female and 49%

male (3). The three most populous counties

were Bergen, Middlesex, and Essex, whereas

the three least populated counties were Salem,

Cape May, and Warren (Figure 2). The largest

population by age group was between 25 and

54 years of age (Figure 3). When categorized by

race alone or in combination, with one or more

other races, the largest population was White

69.1%, followed by Black/African American

15%, then Asian 10.7% (Figure 4). In terms of

Hispanic or Latino race, 79.40% of the

population was non-Hispanic and 20.60%

Hispanic. The proportion of foreign-born

persons in 2018 was 22.8%, second highest in

the nation after California (26.9%), and higher

than the United States average of 13.7% (4),

with most residing in northern counties:

Hudson, Bergen, Passaic, Union, and Essex.

For public health planning and assessment purposes regarding HCV, NJDOH groups

New Jersey counties into the following six public health regions:

Northwest:

Morris, Passaic, Sussex, Warren

Northeast

Bergen, Essex, Hudson

Central West:

Hunterdon, Mercer, Somerset

Central East:

Middlesex, Monmouth, Ocean, Union

Southwest:

Burlington, Camden, Gloucester, Salem

Southeast:

Atlantic, Cape May, Cumberland

Page | 6

Figure 2: New Jersey population by

county, population estimate, 2018

Figure 3: New Jersey population by age group, 2018

Source: American Community Survey (ACS)

Figure 4: New Jersey population by race, 2018

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

White Black/African

American

Source: American Community Survey

Asian Other Amer Indian/

Alaska Native

Race

Social Characteristics/Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants indicators (i.e., social, behavioral, and environmental factors), such as

education level and income, contribute substantially to an individual’s health outcome. People

with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to have unhealthy lifestyle behaviors and lack

access to health care and information on preventive measures for communicable diseases.

69.1%

New Jersey

United States

15.0%

10.7%

7.5%

0.6%

Percent

of population

Page | 7

Education Attainment

People who do not graduate from high school or attend college are less likely to be employed in

safe, high-paying jobs and more likely to have health problems (5). In 2018, for the population

aged 25 years and older in New Jersey, 9.8% did not graduate high school and fewer than 50%

received a bachelor’s degree or higher Figure 5 (6).

Figure 5: Education attainment for the population 25 years and over, 2018

Source: American Community Survey

Median Household Income and Poverty Rate

Socioeconomic factors, such as poverty and living conditions, play a significant role in shaping

infection risk and disease outcomes. Often, people in poverty live in crowded conditions, must

continue to work when they are sick, encounter more stress, and are more likely than others to

use drugs and alcohol (7). Based on the American Community Survey, the estimated median

household income by New Jersey County for 2018 ranged from $55,709 to $117,858 (Figure 6)

(6).

4.7%

26.3%

16.4%

6.6%

24.8%

16.0%

5.1%

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

25.0%

30.0%

Proportion of Population

Education Attainment Level

Less than 9th grade

High school graduate

Some college, no degree

Associate's degree

Bachelor's degree

Graduate degree

12th grade, no diploma

Page | 8

Figure 6: New Jersey median household income for the population 25 years and over, 2018 by county

Source: American Community Survey

Civilian Non-institutionalized Population Who Are Uninsured

A lack of health insurance is associated with decreased care seeking and uptake of HCV

treatment, with cost being a driving factor. Having insurance coverage is associated with

increased linkage to care, faster approval times for treatment, and subsequent retention in care

(8). Since the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted in March 2010, the number of uninsured

persons in New Jersey decreased by 40% from 2010 to 2019 (9). In 2018, the overall proportion

of uninsured, non-institutionalized residents under 65 years of age in New Jersey was 8.7%, with

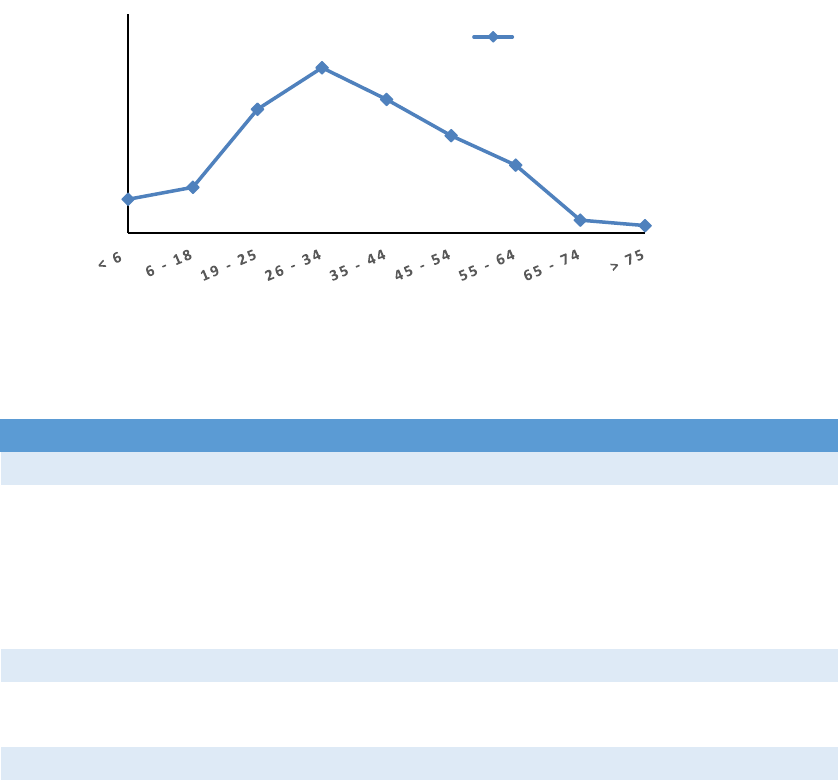

the highest proportion among the 26-34 age group, 15.1% (Figure 7). Of the non- institutionalized

residents between 19 through 64 years old, 9.5% of those employed, and 22.8% of those not

employed were uninsured (Table 1).

Page | 9

Figure 7: Percent of individuals uninsured by age group

Table 1: Number of residents uninsured based on employment status, nativity, and race/ethnicity, 2018.

Categories

Total

Uninsured

Uninsured %

Employment Status

Noninstitutionalized 19 to 64 years old

5,344,092

561,302

10.5%

In labor force

4,315,480

438,499

10.2%

Employed

4,112,267

392,099

9.5%

Unemployed

203,213

46,400

22.8%

Not in labor force

1,028,612

122,803

11.9%

Nativity

Native born

6,784,192

297,209

4.4%

Foreign born

2,019,796

357,791

17.7%

Race and Hispanic Origin

White

5,894,799

350,689

5.9%

Black

1,174,370

102,553

8.7%

American Indian/Alaska Native

20,790

3,732

18.0%

Asian

866,383

45,750

5.3%

Some other race

599,238

135,390

22.6%

Hispanic or Latino

1,822,422

315,286

17.3%

Source: American Community Survey

3.1%

4.2%

11.3%

15.1%

12.2%

8.9%

6.2%

1.2%

0.7%

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

Proportion Uninsured

Age Group

Uninsured by Age

Page | 10

VIRAL HEPATITIS SURVEILLANCE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY IN NEW JERSEY

Testing for HCV Infection

Testing for HCV infection begins with either a rapid or laboratory-conducted assay for hepatitis C

virus (HCV) antibody in blood. A nonreactive HCV antibody result indicates no HCV antibody

detected. A reactive result indicates one of the following: 1) current HCV infection, 2) past HCV

infection that has resolved, or 3) false positivity. A reactive result should be followed by nucleic

acid testing (NAT) for HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA). If HCV RNA is detected, that indicates current

HCV infection. If HCV RNA is not detected, that indicates either past, resolved HCV infection, or

false HCV antibody positivity (10). Per N.J.A.C. 8:57, laboratories and health care providers must

report all suspected cases of newly diagnosed acute and chronic cases of HCV within 24 hours of

diagnosis to NJDOH (11).

Scope of Hepatitis C Disease in New Jersey

HCV represents one of the most common communicable diseases in New Jersey. On average,

NJDOH receives more than 10,000 reports of hepatitis C annually. After data cleaning,

deduplication, and case classification, the number of reports that meet the public health

surveillance case definition for acute and chronic HCV and that were reported to the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) during the 2016-2020 period ranged between 5,517

to 8,125 annually. Regarding overall prevalence of HCV in New Jersey, an analysis of serum

specimens taken from participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

(NHANES) between 2013-2016 revealed a prevalence of 680 persons/100,000 population (12).

Acute Hepatitis C in New Jersey

Estimated Incidence of Hepatitis C in New Jersey

Despite being a reportable disease, many cases of diagnosed acute hepatitis C are not reported to

NJDOH. Most individuals with acute HCV infection do not have a clinically evident illness and, as

a result, do not seek medical care. Thus, determining the true incidence of new HCV infections

per year based on the number of reported cases requires complex epidemiological modeling

techniques. For each new acute HCV case that is reported in the United States, the CDC estimates

there are approximately 13.9 actual cases of new acute HCV (13). Using these estimates, in New

Jersey the estimated number of new cases per year can be as high as 2,000 (Figure 8). In 2018,

the actual number of acute cases reported was 112 compared to the estimated expected number

of 1,557.

Page | 11

Figure 8: Estimated incidence of acute hepatitis C in New Jersey versus reported cases, 2016-2020

2500

2000

1500

1000

500

0

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Year

New Jersey’s rate of acute cases ranked midway among states with reported acute hepatitis C

data in 2018 (13) and that are similar in geographic location and/or population density (14)

(Figure 9).

Figure 9: Rate per 100,000 population of reported cases of acute hepatitis C by selected states, 2018

2

1.8

1.6

1.4

1.2

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

CA CT MD VT IL NJ NY MA ME NH PA

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and United States Census Bureau

Surveillance of Acute Hepatitis C in New Jersey

Between 2016 through 2020, 605 acute hepatitis C cases were reported to NJDOH (Figure 10).

The increase in reported cases from 2016 to 2017 could be related to a change in the public health

surveillance case definition applied in 2017

1

. More than 50% of reported acute HCV cases were

between 25 and 50 years of age, with case rates were highest in Cumberland, Burlington, and

Salem counties (Figure 11). The majority by gender at birth were male, 67.4%. In 2018, the rate

of confirmed acute HCV

cases

in

New

Jersey

was

1.1 per 100,000,

compared

to

1.2 per

100,000 population nationally. For each year over this five-year period, the most reported race

for acute HCV cases was White, followed by Black/African American (cumulative data with

numbers less than 5 were excluded) (Figure 12).

1

Hepatitis C, Acute 2016 Case Definition; https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/hepatitis-c-acute-2016/

Reported

Estimated

1556.8

112

Number

of Cases

1.8

1.9

1.6

1.7

1.1

1.2

0.6

0.6

0.7

0.3 0.3

Rate per 100,000

population

Page | 12

Figure 10: Total reported acute cases in New Jersey, 2016-2020

Figure 11: Characteristics of reported hepatitis C acute cases in New Jersey, 2016-2020

122

147

112

103

121

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Number of Cases

Year

Page | 13

Figure 12: Reported acute hepatitis C cases by race in New Jersey, 2016-202

Source: New Jersey Department of Health, Communicable Disease Service

Risk Factor Characteristics of Acute Hepatitis C Viral Infections

HCV was historically a concern among the “baby boomer” population, those born between 1946-

1964. However, in recent years, most new infections of HCV nationally and in New Jersey have

been among people who share needles, syringes, or other equipment used to prepare and inject

drugs (15). 2018 surveillance data for acute hepatitis C showed that 41 out of the 112 reported

cases or 36.7% were people who use drugs/people who inject drugs (PWUD/PWID), and most

were between the ages of 25-44 years. Other risk factors included unprotected sex (10.87%) and

close contact with a person with confirmed hepatitis infection (7.25%). Approximately 20% to

30% of persons who inject drugs become infected with HCV within the first two years of starting

injection drug use, and 50% become infected within five years of starting injection drug use (12).

Chronic Hepatitis C in New Jersey

Chronic Hepatitis C Surveillance in New Jersey

Between 2016 and 2020, there were a total of 34,098 reported chronic hepatitis C cases in New

Jersey (Figure 13). Over the five-year period, the number of reported cases steadily declined, with

a relatively larger decrease in 2020 (Figure 13) that may be due to COVID-19 and associated

reductions in care seeking and testing. The distribution of reported chronic HCV cases by age, and

gender is illustrated below. A bimodal age distribution with peaks occurring at age 30 years and

60 years is observed (Figure 14). This pattern is consistent with national trends (16). The highest

case rates over the five-year period were in Cumberland, Cape May, and Camden counties (Figure

14). Most chronic HCV cases by gender at birth were male, 61.6%.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Number of Cases

Asian Black/African American Unknown White

Page | 14

Figure 13: Total reported chronic cases in New Jersey, 2016-2020

Figure 14: Characteristics of reported chronic hepatitis C cases in New Jersey, 2016-2020

Between 2016 and 2020, only 43% of reported chronic hepatitis C cases included information on

race. Obtaining race information for reported chronic HCV cases has been a challenge due to the

large number of cases and limited number of public health investigators at the local level focused

on chronic hepatitis C. Like acute HCV cases for each year, the most frequently reported race for

chronic HCV cases was White, followed by Black/African American (Figure 15). Unlike acute cases,

the proportion of cases with ethnicity information is low for chronic cases.

8006

7402

7148

6289

5396

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

7000

8000

9000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Number of Cases

Year

Page | 15

Figure 15: Reported chronic hepatitis C cases by race a) and ethnicity b) in New Jersey, 2016-2020

Source: New Jersey Department of Health, Communicable Disease Service

Perinatal Hepatitis C

The increase in HCV infection related to injection drug use in young adults has resulted in a

corresponding increase among women of childbearing age, age 15 to 44, and women diagnosed

during pregnancy (17). A doubling of HCV diagnoses among women of childbearing age was

observed between 2006 and 2014, surpassing the number among women in older age cohorts

(17). Vertical transmission of HCV occurs in approximately 5.8% of infants born to women who

are infected with HCV and in up to twice as many infants born to women who have high HCV viral

loads (18). In 2018, universal hepatitis C screening during pregnancy was recommended by the

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society

of America (IDSA) (19). Hepatitis C screening is recommended for all pregnant women during

each pregnancy.

NJDOH began monitoring babies born to pregnant people with known HCV infection in 2018. New

Jersey recommends that babies are monitored until they reach 36 months of age to capture HCV

laboratory test results. Additionally, NJDOH works with birthing facilities in New Jersey to ensure

the birthing parent’s HCV status is included on the electronic birth certificate. This process aims

to better capture the HCV burden among this population and to identify babies born to HCV

positive parents to ascertain perinatal HCV transmission.

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Number of Cases

ASIAN BLACK/AFRICAN AMERICAN

UNKNOWN WHITE

AMERICAN INDIAN/ALASKAN NATIVE NATIVE HAWAIIAN/PACIFIC ISLANDER

Page | 16

Between 2017 and 2020, the number of women of childbearing age infected with HCV was

highest among those 25-34 years of age (Figure 16). The southern regions of the state had the

highest rates of HCV-infected women of childbearing age per 10,000 population (Figure 17) and,

similarly, had the highest rates of babies exposed to women infected with HCV (data was

retrospectively collected for the year 2017) (Figure 18). Electronic birth certificate reporting

varies widely by birthing hospital, which may impact regional estimates from 2018 to 2019. At

least one birthing hospital in each region did not report any births associated with hepatitis C. In

2019, in the northeast region there were five hospitals who reported no births associated with

hepatitis C. Ultimately, the number of babies in New Jersey who tested positive for HCV and met

the perinatal HCV case definition in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 was 6, 10, 11, and 8, respectively.

Figure 16: Number of reported women of childbearing age infected with HCV by age group, 2017-2020

800

600

400

200

0

2017 2018 2019 2020

Years

Source: New Jersey Department of Health, Communicable Disease Service

Figure 17: Rate of HCV-infected women of childbearing age per 10,000 population by region, 2017-2020

20.0

15.0

10.0

5.0

0.0

Northwest Northeast

Central West Central East

Southwest Southeast

Regions

Source: New Jersey Department of Health, Communicable Disease Service

15-24 25-34 35-44

2017 2018 2019 2020

Rate per 10,000

Population

Number of

women

infected

Page | 17

Figure 18: Rate of reported perinatal HCV exposure per 10,000 female population of childbearing age, by

public health regions, 2017-2020

10.0

8.0

6.0

4.0

2.0

0.0

Northwest Northeast

Central West Central East South West Southeast

Regions

Source: New Jersey Department of Health, Communicable Disease Service

Morbidity and Mortality

Hepatocellular Cancer

Each year in the United States, around 31,000 people are diagnosed with liver cancer. Among

people with certain liver cancers in the United States, more than 50% have HCV at the time of

cancer diagnosis. Early detection and treatment of viral hepatitis could prevent 90,000 liver

cancer deaths by 2030, starting with 2015 as the baseline year (20). In New Jersey, the observed

incidence rates of liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer steadily increased from 2009 through

2018 for all ages (Figure 19) (21). During 2018, 561 male and 211 female New Jersey residents

were diagnosed with liver cancer (22).

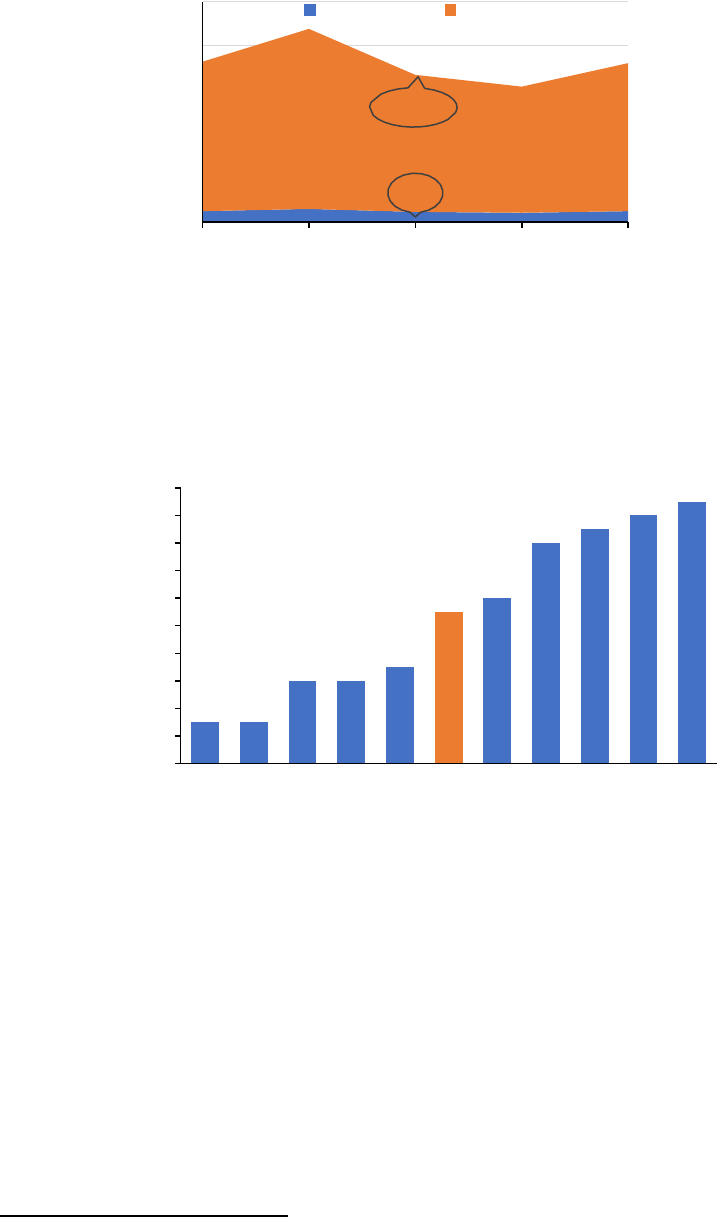

Figure 19: Observed liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer incidence rates in New Jersey, 2009-2018

Source: National Cancer Institute

6

6.5

7

7.5

8

8.5

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Incidence rate per 100,000 population

Years

2017 2018 2019 2020

Exposure

per 10,000

Population

Page | 18

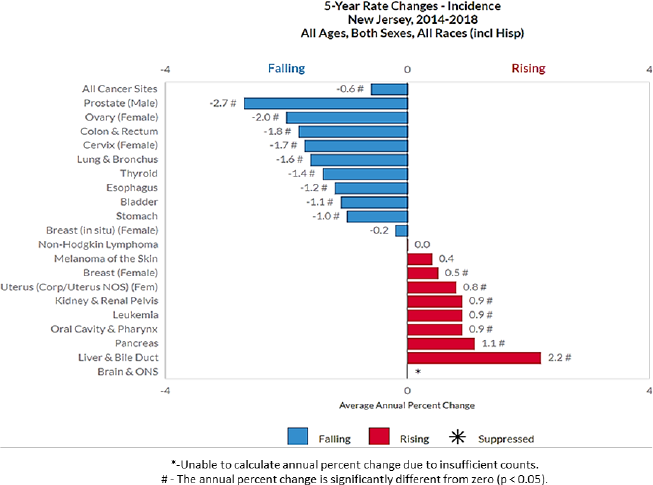

In New Jersey, the average incidence rates of liver and bile duct cancer vary by county and sex

(Figure 20). Camden, Cape May, Cumberland, Hudson, and Ocean counties have the highest

incidence rate for females whereas Atlantic, Camden, Cape May, and Cumberland counties have

the highest incidence rate for males. Cancer of the liver is more common in older people and is

more common in men than in women. In New Jersey, after brain and other nervous system

cancers, liver and bile duct cancer had the greatest increase in incidence rates between 2014 and

2018 (23) (Figure 21).

Figure 20: Average Incidence rates of liver and bile duct cancer in females and males by county, 2014-2018

Source: National Cancer Institute

*Data has been suppressed to ensure confidentiality and stability of rate estimates. Data is currently being

suppressed if there are less than 16 counts in a period.

Page | 19

Figure 21: Average annual percent change of different types of cancer, 2014-2018

Source: National Cancer Institute

Hepatitis C as Cause of Death

Death certificate data is used to characterize deaths in the United States associated with hepatitis

C (23). An overall decline in death rates associated with HCV is noted from 2016 through 2020

(Figure 22). This decline is consistent with the decrease in reported chronic HCV cases and could

be related to people with chronic hepatitis C receiving treatment. The slight increase in 2020

could be due to fewer people receiving treatment and/or people with hepatitis C dying from

causes related to COVID-19. Counties with the highest death rates of hepatitis C as the underlying

cause of death from 2016 to 2020 were Essex, Hudson, Camden, Mercer, and Passaic, with crude

rates of 1.5 to 1.1 per county population (24).

Page | 20

Figure 22: Deaths per 100,000 population where underlying cause of death was hepatitis C in New Jersey

and the United States, 2016-2020

4.5

4

3.5

3

2.5

2

1.5

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Year

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Liver Cancer as Cause of Death

Liver and intrahepatic bile duct cancer is the sixth leading cause of cancer death in the United

States. The death rate was 6.6 per 100,000 population per year based on 2016-2020 age- adjusted

deaths (21). In 2019, for every 100,000 people, there were eight new liver and intrahepatic bile

duct cancer cases, and seven deaths. In New Jersey, between 2018 and 2020, there were 2048

liver cancer-related deaths reported, with a crude rate of 7.7 per 100,000 population (25). The

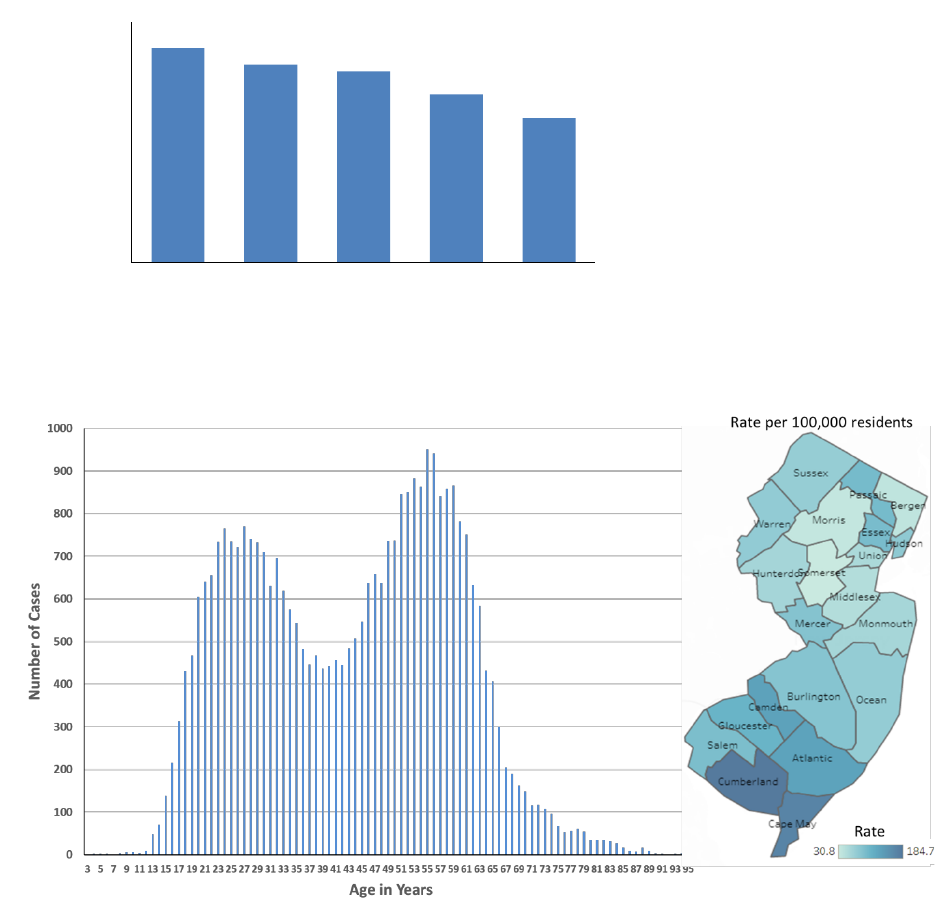

number of liver cancer related deaths was largest among people aged 65-74 years (Figure 23).

Figure 23: Number of liver-related cancer deaths for New Jersey residents by age group, 2018-2020

400

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85-89 90-94 95-99

Age Group

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

New Jersey

United States

Death per 100,000

Number

of deaths

Page | 21

VIRAL HEPATITIS IN SPECIAL POPULATIONS IN NEW JERSEY

HIV Co-infections

HCV and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are bloodborne viruses transmitted through direct

contact with the blood of an infected person, and, as a result, co-infection with HIV and HCV is

common. Among injection-drug users who have HIV, 62-80% are co-infected with HCV (26).

Although transmission via injection-drug use remains the most common mode of HCV acquisition

in the United States, sexual transmission is an important mode of acquisition among Men Who

Have Sex with Men (MSM) with HIV who also have risk factors, including those who use non-

injection drugs. HCV infection may also affect the management of HIV infection (26).

Of the 7,258 HCV cases reported to NJDOH in 2018, 258 (3.6%) were co-infected with HIV/AIDS.

Over 60% of those infected with HCV or HIV/AIDS, resided in Essex, Hudson, Union, Passaic, and

Middlesex counties. Fifty-two percent of the co-infected individuals were exposed to HIV/AIDS

through injection drug use (IDU) or MSM/IDU, 2.8 times the proportion among the HIV/AIDS

group that is not co-infected with HCV. Mortality was higher among HCV cases co-infected with

HIV, 6.4% died between the beginning of 2018 through August 2019, compared to 2% for HCV

cases not co-infected. The risk of mortality among HCV cases co-infected with HIV is greater than

3 times that of the HCV non co-infection group.

Persons Who Use or Inject Drugs

A deadly consequence of the opioid crisis is an increase in blood-borne infections, including viral

hepatitis (27). PWUD or PWID are at risk for HCV infection through the sharing of needles and

equipment used to prepare and inject drugs. In recent years, an emerging HCV epidemic has been

occurring among young PWID, particularly in rural and suburban settings (28). Between 2016 and

2019, the highest rate of drug-related hospital visits were among persons 25-34 years of age,

followed by persons 15-24 and 35-44 years of age (Figure 24) (29).

Page | 22

Figure 24: Rate of drug-related hospital visits per 100,000 population by age group in New Jersey, 2016-

2019

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

<15 15-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-74 75-84 85+

Age Group

Source: New Jersey Department of Health, Population Health

PWID/PWUD was the most frequently reported risk factor for reported acute hepatitis C cases in

2018, 2019, and 2020 at 36.6%, 46.6% and 33%, respectively. Acute HCV cases between 25

through 34 years of age had the highest proportion of PWID/PWUD (Figure 25).

Figure 25: Proportion of reported acute HCV cases with identified PWID/PWUD by age group, New

Jersey, 2018-2020

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

15-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64

Age Group

Source: Source: New Jersey Department of Health, Communicable Disease Service

Incarcerated individuals

Hepatitis C prevalence in U.S. correctional settings is disproportionately high because of

disproportionately high incarceration rates among persons who use drugs (30). Compared

with the general population, the prevalence of viral hepatitis and other bloodborne related

diseases such as HIV is higher among people who are incarcerated, with hepatitis C rates 10 times

higher in jails and prisons (31). The correctional institutions and jails in New Jersey that house

2019

2018

2017

2016

2018 2019 2020

Proportion

of Cases

Visits

per 100,000

Page | 23

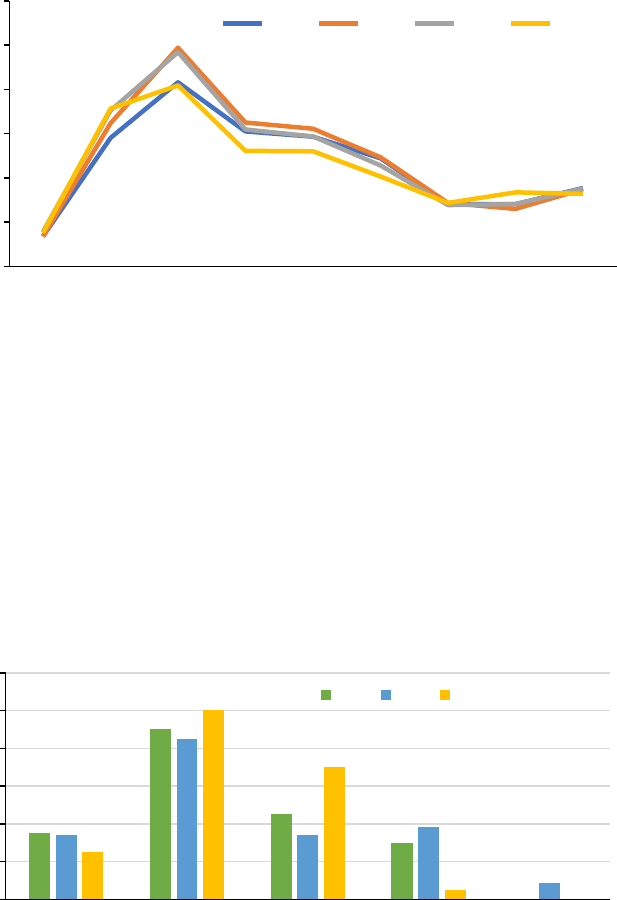

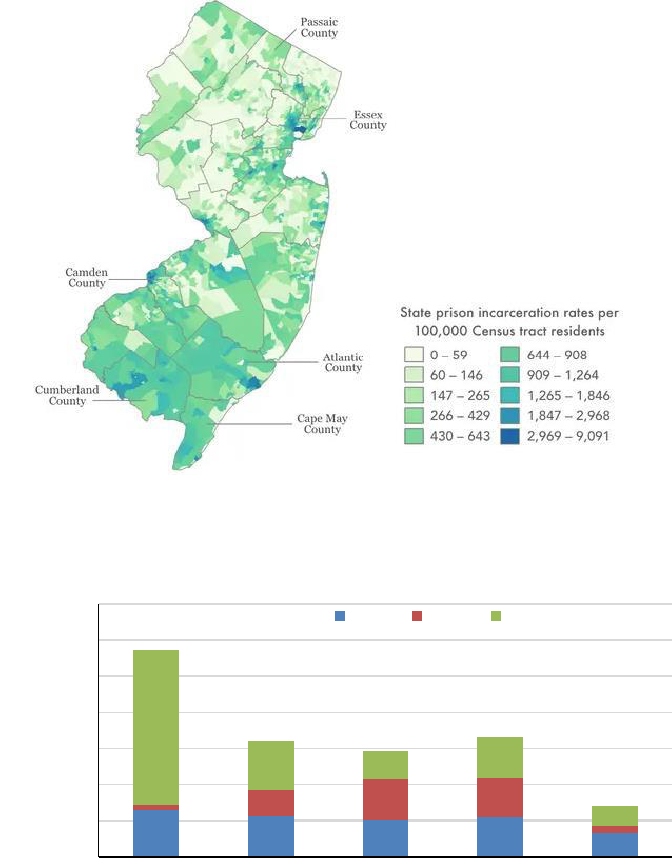

confined inmates are mainly federal, state, and county facilities. Six counties in New Jersey account

for roughly a quarter of the state’s population, however, more than half of the state’s imprisoned

population come from those counties (Figure 26) (32). Between 2016 and 2020, there has been an

increased number of HCV reports from federal facilities and a decreased number from state

facilities (Figure 27) (8).

Figure 26. State prison incarceration rates per 100,000 population (2020)

Source: Prison Policy Initiative

Figure 27: Number of cases reported with hepatitis C by correctional facility, 2016-2020

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Year

Source: New Jersey Department of Health, Population Health

County Federal State

Number

of cases

Page | 24

ADDRESSING VIRAL HEPATITIS IN NEW JERSEY

Prevention and Education

Successful hepatitis C surveillance and prevention plans require strong collaboration. The goal of

this collaboration is to use surveillance data to accurately identify high-impact settings and

populations, linking those in need to services, and prevention of new infections. The NJDOH

Communicable Disease Service (CDS) is continually working collaboratively with partners at the

federal, state, and local levels to accomplish such goals.

In October 2019, NJDOH participated in a statewide Viral Hepatitis Summit. This event drew 200

stakeholders and partners from across the state and served as the kickoff to the ongoing viral

hepatitis elimination planning in the state. Elimination planning is an integrative and

collaborative approach, with several focus areas, including HCV testing, data sharing, educational

outreach, linkage to care, harm reduction and technical support.

Hepatitis C Testing

CDC’s 2020 updated testing recommendations for HCV infection call for universal screening: a

one‑time hepatitis C testing regardless of age or setting prevalence among people with

recognized conditions or exposures, routine periodic testing for people with ongoing risk factors,

and ad hoc testing of any person who requests hepatitis C testing (33). One of the main goals of

the CDS HCV program is to promote HCV testing with a focus on the populations most at-risk. CDS

encourages health care providers, through education and outreach, to incorporate universal HCV

testing using recommended diagnostic tests (Appendix Figure 30). Currently, New Jersey only

requires positive HCV test results to be reported to the state. This makes it difficult to calculate

the total number of individuals tested for HCV, as well as those who may develop an acute

infection. Revised regulations targeted for 2024 are expected to include a requirement for the

reporting of negative hepatitis C results. This should facilitate better understanding of the

hepatitis C burden in New Jersey.

In New Jersey, 12 commercial labs conduct hepatitis C testing and report results via electronic

laboratory reporting (ELR) to NJDOH, as do all 71 acute care hospitals and three public health

laboratories (New Jersey, New York, and Florida). NJDOH has a viral hepatitis service locator

interactive dashboard available to the public 24/7 (34). This dashboard includes an HCV testing

facility locator as illustrated below (Figure 28).

Page | 25

Figure 28: HCV testing facilities in New Jersey.

Source: New Jersey Department of Health

Hepatitis C Treatment

While there are many challenges regarding HCV treatment, both personal and systematic, NJDOH

and other partners aim to address some of these barriers through elimination initiatives.

Systematically, there have been some improvements. As of 2018, fibrosis restrictions for access

to HCV treatment for Medicaid Managed Care (MMC) clients were lifted in New Jersey. There are

also no restrictions on the time abstained from drug or alcohol use, prescriber, or retreatment

restrictions. However, prior authorization requirements currently remain in place for HCV

treatment from MMC plans. There are several free or low-cost providers in the state who provide

HCV treatment, (34) (Figure 29), and HCV treatment is also provided in state correctional settings.

Figure 29: HCV treatment facilitates in New Jersey.

Source: New Jersey Department of Health

Page | 26

Laboratory Based HCV Clearance Cascade

Construction of an HCV testing cascade that quantifies screening and confirmatory testing can

help public health agencies ensure equity in diagnosis and linkage to HCV care at the population

level (35). Using CDC’s guidance, a laboratory-based care cascade model was developed from

HCV antibody and HCV RNA test results reported to the Communicable Disease Reporting and

Surveillance System (CDRSS) for the first time for a resident between 2018 and 2020. Cases were

evaluated for subsequent testing up to September 2022.

The HCV cure rate in New Jersey is low. The model shows that of the 18,787 persons who had a

positive anti-HCV test during the evaluation period (ever infected), 52.9% had an initial positive

HCV RNA reported (initial infection), with a subsequent positive HCV RNA 49.3% (not cured) and

6.6% had a subsequent negative HCV RNA (cured) reported (Figure 30). This cascade also suggests

that infection status is unknown for nearly half of individuals who were ever infected.

Figure 30: Laboratory-based HCV clearance cascade for New Jersey, 2018–2020

18787

Ever Infected Initial Infection Not Cured Cured/Cleared

In terms of specific populations, the HCV care cascade analysis highlights some disparities, (Table

2). Males are more likely to be infected with HCV, but less likely to receive confirmatory testing

and to achieve cure compared to females. The cascade analysis also shows that the 15-34-years

and 55-64 years age groups were most likely to not achieve cure despite receiving confirmatory

test results.

Because only positive HCV laboratory results are required to be reported to NJDOH, determining

the number of HCV infected persons who receive treatment is a challenge. A subset of

laboratories and hospitals do provide negative laboratory HCV results to NJDOH. However,

mandatory reporting of negative HCV results will better inform the progress of and gaps in HCV

treatment in the state.

9929, 52.9%

9269, 49.3%

660, 6.6%

Page | 27

Table 2: Conditional proportions for the laboratory-based HCV clearance cascade by subpopulation

Characteristics

Ever

Infected

No Viral

Tests

No Viral

Tests

Proportion

(%)

Initial

Infection

Not

Cured or

Cleared

Not Cured or Cleared

Proportion (%)

Age Group

<15

106

55

0.3

40

39

0.4

15-34

4862

1709

9.1

2945

2754

27.7

35-44

3215

1269

6.8

1823

1716

17.3

45-54

2921

1325

7.1

1482

1382

13.9

55-64

4500

2186

11.6

2177

2008

20.2

65-74

2516

1218

6.5

1180

1099

11.1

75+

667

349

1.9

282

271

2.7

Sex at birth

Female

7348

3393

18.1

3602

3355

33.8

Male

11415

4703

25

6318

5905

59.5

Unknown

24

15

0.1

9

9

0.1

Race/Ethnicity

White, NH

7924

2932

15.6

4660

4303

43.3

Black, NH

2608

1114

5.9

1406

1322

13.3

Hispanic

1978

829

4.4

1075

1004

10.1

Asian, NH

27

14

0.1

12

12

0.1

Asian

382

172

0.9

185

177

1.8

Other/Unknown

5868

3050

16.2

2591

2451

24.7

Total

18787

8111

43.2

9929

9269

93.4

SUMMARY

In observing data over the period 2018 through 2020, the New Jersey Hepatitis C Epidemiologic

Profile provides background information related to HCV disease burden and the overall landscape

of HCV in the state. HCV is one of the most common communicable diseases in the state of New

Jersey. From 2016 through 2020, there were 605 newly acquired, 34,098 chronic, and 35 perinatal

cases reported to NJDOH. Not all individuals are aware of their hepatitis status, and there is

significant underreporting of cases. Many individuals face various social constraints that impact

infection risk, access to health care, and information on preventative measures for this

communicable disease. Currently, the primary risk factor for HCV infection is injection drug use.

This profile points to the importance of appropriate testing, improved surveillance, aggressive

prevention and education activities, and collaboration with various partners to keep New Jersey

on track for HCV elimination. Furthermore, this document can be used as a resource for

researchers, providers, policymakers, and all residents of New Jersey who are dedicated to the

elimination of hepatitis C.

Page | 28

REFERENCES

1. Estimating prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United. Hofmeister, Megan G. 3, Atlanta:

Hepatology, 2019, Vol. 69.

2. State of New Jersey. 2019 New Jersey State Hazard Mitigation Plan. Office of Emergency

Management. [Online] January 25, 2019. [Cited: March 7, 2022.]

https://www.state.nj.us/njoem/mitigation/2019-mitigation-plan.shtml.

3. United States Census Bureau. Demographics and Housing Estimates, 2018: ACS 1-Year Estimates

Subject Tables. American Community Survey. [Online] 2018. [Cited: May 20, 2022.]

https://data.census.gov/table?q=DP05&g=0400000US34,34$0500000&y=2018.

4. Selected Social Characteristics in the United States, 2018: ACS 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables.

American Community Survey. [Online] 2018. [Cited: May 27, 2022.]

https://data.census.gov/table?q=Native+and+Foreign+Born&g=0100000US_0400000US06,34,36&tid=A

CSDP1Y2018.DP02.

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Education Access and Quality. Healthy People 2020.

[Online] [Cited: April 17, 2023.] https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-

objectives/education-access-and-quality.

6. United States Census Bureau. Selected Economic Characteristics. American Community Survey.

[Online] 2018. [Cited: May 20, 2022.]

https://data.census.gov/table?g=040XX00US34_050XX00US34001&tid=ACSDP1Y2018.DP03.

7. Vaida, Bara. Covering Health. Association of Health Care Journalists. [Online] September 27, 2018.

[Cited: April 17, 2023.] https://healthjournalism.org/blog/2018/09/connecting-the-dots-between-social-

determinants-and-infectious-diseases/.

8. Alexandra DeBose-Scarlett, Raymond Balise, Deukwoo Kwon, Susan Vadaparampil, Steven Xi Chen,

Eugene R. Schiff, Gladys Patricia Ayala, and Emmanuel Thomas. Obstacles to Successful Treatment of

Hepatitis C in Uninsured Patients from a Minority Population. Journal of Translational Medicine. 16,

2018, Vol. 178.

9. Healthinsurance.org. New Jersey and the ACA's Medicaid Expansion. A Trusted Independent Health

Insurance Guide Since 1994. [Online] Healthinsurance.org, 1994-2023. [Cited: February 28, 2023.]

https://www.healthinsurance.org/medicaid/new-jersey/.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Laboratory Testing. Viral Hepatitis. [Online] March 28,

2019. [Cited: October 10, 2022.] https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/labtesting.htm.

11. State of New Jersey Department of Health. NJ Administrative Code. Communicable Disease Service.

[Online] April 5, 2017. [Cited: May 20, 2022.]

https://www.nj.gov/health/cd/imm_requirements/acode/index.shtml.

Page | 29

12. University of Washington. HCV Epidemiology in the United States. Hepatitis C Online. [Online] May

26, 2021. [Cited: July 25, 2022.] https://www.hepatitisc.uw.edu/go/screening-diagnosis/epidemiology-

us/core-concept/all.

13. Hepatitis, Division of Viral. 2018 Surveillance Report. Viral Hepatitis. [Online] August 7, 2020.

[Cited: July 22, 2022.]

https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2018surveillance/pdfs/2018HepSurveillanceRpt.pdf.

14. United States Census Bureau. Historical Population Density Data (1910-2020). Census.gov. [Online]

April 26, 2021. [Cited: July 20, 2022.] https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/density-

data-text.html.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C Questions and Answers for Health

Professionals. Viral Hepatitis. [Online] Division of Viral Hepatitis, National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis,

STD, and TB Prevention, August 7, 2020. [Cited: July 22, 2022.]

https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#b1.

16. Hepatitis C now heavily impacting multiple generations. NCHHSTP Newsroom. [Online] April 9,

2020. [Cited: June 21, 2021.] https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2020/hepatitis-c-impacting-

multiple-generations.html.

17. Changing epidemiology, implications, and recommendations for hepatitis C in women of childbearing

age and during pregnancy. Tatyana Kushner, Nancy Reau. New York: Journal of Hepatology, 2021, Vol. 74.

18. Alaya Koneru, et al. Increased Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Detection in Women of Childbearing Age and

Potential Risk for Vertical Transmission — United States and Kentucky, 2011–2014. Morbidity and

Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 2016, Vol. 65, 28.

19. Sarah Schille et al. CDC Recommendations for Hepatitis C Screening Among Adults — United States,

2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 2020, Vol. 69, 2.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatitis & Liver Cancer Prevention Profile. CDC

Stacks. [Online] March 23, 2018. [Cited: August 16, 2022.] https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/109302.

21. National Institute of Health. Cancer Stat Facts: Liver and Intrahepatic Bile Duct Cancer. National

Cancer Institute, Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program. [Online] Surveillance Epidemiology

and End Results Program, 2022. [Cited: September 14, 2022.]

https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/livibd.html.

22. New Jersey Department of Health. Health Indicator Report of Incidence of Liver Cancer. New Jersey

State Health Assessment Data. [Online] December 03, 2021. [Cited: July 25, 2022.] https://www-

doh.state.nj.us/doh-shad/indicator/view/LiverCa.YearSex.html.

23. National Cancer Institute. Interactive Maps. State Cancer Profiles. [Online] September 14, 2022.

[Cited: September 14, 2022.]

https://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/map/map.withimage.php?34&county&001&035&00&1&01&0&

1&5&0#results.

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatitis. [Online] Numbers and rates* of deaths

with hepatitis C listed as a cause of death† among residents, by state or jurisdiction — United States,

Page | 30

2016-2020, August 17, 2022. [Cited: September 09, 2022.]

https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2020surveillance/hepatitis-c/table-3.7.htm.

25. About Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2020. CDC Wonder. [Online] National Center for Health

Statistics. National Vital Statistics, September 14, 2022. [Cited: September 14, 2022.]

https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html.

26. Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and People Coinfected with HIV and Viral Hepatitis. Viral

Hepatitis. [Online] September 21, 2020. [Cited: September 19, 2022.]

https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/populations/hiv.htm.

27. Persons Who Inject Drugs (PWID). National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB

Prevention. [Online] July 2018, 2018. [Cited: September 21, 2022.] https://www.cdc.gov/pwid/.

28. People Who Use or Inject Drugs and Viral Hepatitis. Viral Hepatitis. [Online] August 24, 2020.

[Cited: September 21, 2022.] https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/populations/idu.htm.

29. New Jersey Department of Health. Drug Related Hospital Visits. Population Health. [Online]

2022. [Cited: September 16, 2022.]

https://www.state.nj.us/health/populationhealth/opioid/opioid_hospital.shtml.

30. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Recommendations for Hepatitis C Screening Among

Adults — United States, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). [Online] April 10, 2020.

[Cited: September 21, 2022.] https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/rr/rr6902a1.htm.

31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Recommendations for Correctional and Detention

Settings. National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. [Online] April 18, 2022. [Cited:

September 21, 2022.] https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/dear_colleague/2022/dcl-041822-correctional-

health.html.

32. Emily Widra, Henal Patel, and Ronald Pierce. Where people in prison come from: The geography of

mass incarceration in New Jersey. Where people in prison come from. [Online] June 2022. [Cited: April

17, 2023.] https://www.prisonpolicy.org/origin/nj/2020/report.html.

33. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Testing Recommendations for Hepatitis C Virus

Infection. Viral Hepatitis. [Online] July 29, 2020. [Cited: February 14, 2023.]

https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/guidelinesc.htm.

34. New Jersey Department of Health. New Jersey Department of Health Hepatitis Services Locator.

[Online] March 2022. [Cited: February 14, 2023.]

https://dashboards.doh.nj.gov/views/HepatitsServicesDashboard/Introduction?%3Aorigin=viz_share_lin

k&%3Aembed=y&%3AisGuestRedirectFromVizportal=y&_gl=1*vahojy*_ga*MTEzNDM5OTUwLjE2NDg1

NTg0NTU. *_ga_5PWJJG6642*MTY2OTA2Mjc0MS40MS4xLjE2NjkwNjI3NjQuM.

35. Quynh T Vo, Shauna Onofrey, Daniel Church, Kevin Cranston, Alfred DeMaria, R Monina Klevens.

The Massachusetts Hepatitis C Testing Cascade 2014-2016. Microbiology Insights. 2019, Vol. 12.

Page | 31

APPENDIX

Figure 31. CDC recommended HCV testing sequence

Page | 32

Figure 32. New Jersey median age by county, population estimate 2018

Table 3. Median household income and poverty rate for population 25 years and over based on

education level

Population > 25 years/

Earnings and Poverty Rate

Earnings,

all

Poverty %

all

Earnings

Male

Poverty %

Male

Earnings

Female

Poverty

%

Female

Population > 25 years

50,913

(X)

60,183

(X)

41,869

(X)

Less than high school graduate

24,963

22.4

30,484

19.1

18,126

25.5

High school graduate

34,431

10.1

41,717

7.7

27,460

12.3

Some college/Associate degree

42,079

7.5

51,474

5.7

35,177

9.1

Bachelor’s degree

65,658

3.4

79,360

2.9

55,702

3.7

Graduate or professional degree

89,332

(X)

109,510

(X)

73,106

(X)

Source: American Community Survey (ACS)

Page | 33

Table 4. Percent of individuals uninsured by year for residents under the age 65 years

16.0%

14.0%

12.0%

10.0%

8.0%

6.0%

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

% Uninsured by Year

Source: New Jersey State Health Assessment Data

Figure 33. Age adjusted death rate, 2018-2020

45 - 49 50 - 54 55 - 59 60 - 64 65 - 69 70 - 74 75 - 79 80 - 84

Age Group

*Age groups without population data were excluded

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Age Adjusted

Crude

Death

Rate

1.7

4

8.2

16.8

24.9

29

37.5

40.1