(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

683

ARTICLE

FORECLOSURE REFORM AMID

MORTGAGE LENDING TURMOIL:

A PUBLIC PURPOSE APPROACH

Prentiss Cox

*

T

ABLE OF CONTENTS

I.

INTRODUCTION .....................................................................685

II. RISING MORTGAGE FORECLOSURES

IN THE UNITED STATES.........................................................687

A. Rising Foreclosures and the Subprime

Lending Connection .....................................................688

B. Impact of Rising Foreclosures on Communities ...........693

1. Concentrated Subprime Mortgage

Foreclosures Are Causing Blight ...........................693

2. Metropolitan Example:

Minneapolis, Minnesota ........................................696

III. BORROWERS, LENDERS, AND

M

ORTGAGE FORECLOSURE LAW ...........................................697

A. Elements of State Foreclosure Laws .............................699

1. Judicial Versus Nonjudicial Procedures...............699

2. Notice Requirements..............................................700

3. Foreclosure Sale Procedures..................................701

4. Borrower Redemption and

Reinstatement Rights.............................................701

5. Antideficiency Protections......................................702

* Associate Professor of Clinical Law, University of Minnesota Law School. The Author

thanks Donald Brewster for his generosity in sharing his extraordinary database of resources and

tremendous knowledge. The Author also thanks Ann Burkhart, Brett McDonald, and Jeff Crump for

their helpful advice, and Jon Taylor for his timely and excellent research assistance.

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

684 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

B.

Effect of Varying Foreclosure Laws ..............................703

1. Hypothetical Foreclosure

Laws in States A and B .........................................703

2. The Smiths.............................................................704

3. Investor Jones ........................................................706

C. Conduct of Lenders and Borrowers

in Foreclosure................................................................707

1. Lender Response To Mortgage Default..................707

2. Borrowers in Mortgage Default .............................708

IV. EXISTING SCHOLARSHIP ON

F

ORECLOSURE LAW ..............................................................715

A. Foreclosure Laws from the

Perspective of Economists .............................................715

B. Foreclosure from the Perspective of

Legal Scholars...............................................................717

C. Limited Importance of Foreclosure Sales .....................720

V. FORECLOSURE LAW AS HOUSING POLICY .............................723

A. Sustainable Homeownership ........................................723

B. Foreclosure Law Affects Community

Stability and Housing Quality .....................................726

VI. IMPLEMENTING FORECLOSURE

R

EFORM AS HOUSING POLICY ...............................................727

A. Bifurcated Foreclosure by Property Type......................728

1. Shorten the Foreclosure Process

for Investment Property .........................................728

2. Lengthen the Foreclosure Process

for Homeowners .....................................................730

3. Objections to Extended Reinstatement

Rights for Homeowners..........................................733

4. Defining Property Types in a

Bifurcated System..................................................739

B. Notices to Homeowners .................................................739

1. Plain Language Homeowner

Assistance Notices..................................................740

2. Nonpublic Notice of Default

to Public Entities. ..................................................741

C. Implementation of Foreclosure Reform.........................743

VII. CONCLUSION.........................................................................744

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

2008] AN APPROACH TO FORECLOSURE REFORM 685

I. I

NTRODUCTION

Irene Thomas was twenty-one years old when she met a man

outside of a nightclub who convinced her that she could make

money in real estate.

1

A mortgage broker and others used her

credit rating to obtain ten residential properties within a ninety-

day period with no money down.

2

Ms. Thomas incurred $2.4

million in mortgage debt for these home purchases.

3

Just over a

year later, all the properties were in foreclosure after Ms.

Thomas failed to make the mortgage payments.

4

The

neighborhood on the north side of Minneapolis where these ten

properties are located has been wracked by an approximately

five-fold increase in foreclosures that has led to abandoned

homes and neighborhood deterioration.

5

In north Minneapolis

alone there have been 1,400 houses sold through foreclosure

auctions.

6

Much of the problem in north Minneapolis involves

foreclosure of rental investment property,

7

which resulted in

deteriorated housing quality in the neighborhood. Ms. Thomas

now has ruined credit because she was duped by those who sold

her homes at inflated prices.

8

Franklin and Beryl Abazie bought a home in Newark using

two subprime mortgage loans.

9

Mr. Abazie took a second job at a

state mental hospital in an attempt to make the payments on the

loans.

10

After giving birth to their first child, Mrs. Abazie

returned to work at a home for the elderly.

11

The family also

found a tenant to help pay the mortgage.

12

Ultimately, the

monthly payments on the loans overwhelmed the Abazie family,

and their mortgage went into foreclosure.

13

The Newark

neighborhood in which the Abazie family lives is covered with

1. Pam Louwagie & Glenn Howatt, “Straw Buyer” Deals Fuel Tidal Wave of

Foreclosures, S

TAR TRIB. (Minneapolis), June 10, 2007, at A1.

2. Id.

3. Id.

4. Id.

5. The five-fold increase is reflective of the data provided by the Hennepin

County Sheriff’s Office. This data can be accessed at http://www4.co.hennepin.mn.us/

webforeclosure/.

6. Pam Louwagie & Glenn Howatt, Foreclosure Epidemic, S

TAR TRIB.

(Minneapolis), May 5, 2007, at A1.

7. Id.

8. See Louwagie & Howatt, supra note 1.

9. Kareem Fahim & Ron Nixon, Behind Foreclosures, Ruined Credit and Hopes,

N.Y.

TIMES, Mar. 28, 2007, at A1.

10. Id.

11. Id.

12. Id.

13. Id.

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

686 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

signs that say “Avoid Foreclosure” or “Sell Your Home,”

symptoms of a foreclosure crisis.

14

The explosive growth and recent collapse of the subprime

mortgage lending industry has led to an increase in mortgage

foreclosures that will persist for years.

15

Rising foreclosures have

started to blight certain areas of American cities hit hardest by

the problem.

16

As the consequences of rising foreclosure become

apparent in the form of deteriorating neighborhoods, state

legislatures are looking to reform foreclosure law.

17

State foreclosure laws have developed over centuries, and

the rights of the borrowers and the lenders vary widely between

jurisdictions.

18

In Georgia, property can be sold at auction within

two months of the initiation of the foreclosure.

19

In Indiana, the

foreclosure process must occur through court action and takes a

minimum of almost nine months.

20

Each state has its own array

of notice requirements, sale procedures, and borrower protections

prior to or after the sale.

21

Yet there are few distinctions in the

14. Id.

15. See

infra notes 26–55 and accompanying text (describing the nature of the

recent subprime mortgage crisis).

16. See N

EIGHBORHOOD HOUS. SERVS. OF CHI., INC., PRESERVING HOMEOWNERSHIP:

COMMUNITY-DEVELOPMENT IMPLICATIONS OF THE NEW MORTGAGE MARKET 13–20 (2004),

available at http://www.nw.org/network/neighborworksProgs/foreclosuresolutionsOLD/

documents/preservingHomeownershipRpt.pdf [hereinafter NEIGHBORHOOD HOUSING]

(recommending changes in state foreclosure laws to address the rising number of

foreclosures).

17. See National Conference of State Legislatures, 2007 Foreclosure Legislation,

http://www.ncsl.org/standcomm/sccomfc/Foreclosures_2007.htm (last visited Sept. 5, 2008)

(listing 28 state legislatures with proposed legislation addressing some aspect of

foreclosure law).

18. See, e.g., Debra Pogrund Stark, Facing the Facts: An Empirical Study of the

Fairness and Efficiency of Foreclosures and a Proposal for Reform, 30 U.

MICH. J.L.

REFORM 639, 643–48 (1997) (detailing the advantages to lenders and borrowers in

different kinds of foreclosures).

19. G

A. CODE ANN. § 44-14-180 (2007); see also THE NATIONAL MORTGAGE

SERVICER’S REFERENCE DIRECTORY 89 (22d ed. 2005) [hereinafter MORTGAGE DIRECTORY]

(estimating that a foreclosure sale can occur in as little as thirty-seven days from referral

of file to foreclosing attorney); Vikas Bajaj, Increasing Rate of Foreclosures Upsets Atlanta,

N.Y.

TIMES, July 9, 2007, at A1 (“Georgia’s foreclosure laws have also accelerated a

process that can drag on for months in legal proceedings in other states. Lenders can

declare a borrower in default and reclaim a house in as little as 60 days.”).

20. I

ND. CODE § 32-29-7-3 (2007); see also MORTGAGE DIRECTORY, supra note 19, at

1-105, 1-108 (estimating a minimum of 266 days to complete the foreclosure process).

21. Patrick A. Randolph, Jr., The Future of American Real Estate Law: Uniform

Foreclosure Laws and Uniform Land Security Interest Act, 20 N

OVA L. REV. 1109, 1112

(1996). (“[L]and laws in individual states developed to reflect the special political values

that the citizens of those states held.”); see also J

OHN RAO, ODETTE WILLIAMSON & TARA

TWOMEY, FORECLOSURES: DEFENSES, WORKOUTS AND MORTGAGE SERVICING § 1.3.1.2,

app. C (2d ed. 2007) (noting that each state has its own foreclosure laws and detailing the

provisions for each state).

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

2008] AN APPROACH TO FORECLOSURE REFORM 687

various state laws between foreclosing on the multiple loans for

the ten properties bought and abandoned by Irene Thomas and

foreclosing on loans to homeowners like the Abazie family.

Part II of this Article describes the origin, scope, and

consequence of rising foreclosures. Part III provides an overview of

the law governing mortgage foreclosure, which is predominantly a

matter of divergent state statutes. This Part also discusses the

reality for homeowners and lenders in the foreclosure process.

Part IV examines the current commentaries on foreclosure law.

Legal scholars have focused particular attention on the foreclosure

sale mechanism and proposals for alternate sale procedures, often

cleverly conceived, that arguably would provide for more efficient

outcomes for the parties or the broader market.

The principal argument in this Article is that state

foreclosure laws should reflect broader public interests in

housing policy, not just a balancing of the competing interests of

the parties to mortgage default. In particular, reform of state

foreclosure laws can be a tool in ameliorating homeownership

loss and stabilizing neighborhoods hardest hit by foreclosures.

Part V discusses the relationship between foreclosure laws and

these national housing policy goals. Focusing on broader public

policy goals provides a different focus on foreclosure law reform

than prior discourse in this area.

Part VI advocates two fundamental types of reform of state

foreclosure laws. Subpart A argues for a bifurcation of foreclosure

procedures by property type. Lenders should be able to

expeditiously foreclose on investor property, including residential

property not owner-occupied. Homeowners who occupy

residential property should be given longer reinstatement

periods, and redemption periods should be replaced with

reinstatement rights. The Abazie family should be given every

opportunity to maintain ownership of their home, while there is

little reason to prolong the foreclosure process to protect the

interests of Irene Thomas in her ten properties. Subpart B

advocates new notice provisions that would change the content,

frequency, and public filing requirements of state foreclosure

laws. Finally, Subpart C describes the advantage of this more

flexible approach to foreclosure reform rather than the multiple

unsuccessful attempts at enacting uniform state laws.

II. R

ISING MORTGAGE FORECLOSURES IN

THE UNITED STATES

Not since the Great Depression of the 1930s has mortgage

foreclosure been a significant topic of public discussion. This is no

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

688 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

doubt true because foreclosure rates are creeping toward

Depression-era levels.

22

The increase in mortgage defaults and

foreclosures are causing distress in the financial markets.

23

The

Federal Reserve Board and its chairman, Ben Bernanke, have

issued a series of statements in an effort to calm concerns about

widespread financial turmoil caused by the increase in defaults

and foreclosures.

24

The investment banking industry, which

issues mortgage-backed securities, is scrambling to decode the

magnitude of losses and the effect on the market.

25

Subpart A briefly describes the subprime lending practices

that primarily have caused increasing foreclosures. Subpart B

details the effect of rising mortgage foreclosure rates on certain

communities, including a detailed description of the increase in

foreclosures in Minneapolis, Minnesota, as an example of the

problem.

A. Rising Foreclosures and the Subprime Lending Connection

There is no comprehensive and authoritative source for data

on foreclosures.

26

Yet however measured, the number and rate of

22. Nelson D. Schwartz, Can the Mortgage Crisis Swallow a Town?, N.Y. TIMES,

Sept. 2, 2007, § 3 (Sunday Business), at 1.

23. See Deborah Solomon, Bush Moves to Aid Homeowners, W

ALL ST. J., Aug. 31,

2007, at A4 (discussing turmoil in the market caused by foreclosures and the political

response).

24. Ben S. Bernanke, Chairman, Fed. Reserve Bd., Remarks Made at the Federal

Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Economic Symposium (Aug. 31, 2007) (transcript

available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20070831a.htm);

Ben S. Bernanke, Chairman, Fed. Reserve Bd., The Housing Market and Subprime

Lending, Remarks via satellite to the 2007 International Monetary Conference (June

5, 2007) [hereinafter Bernanke, Housing Market] (transcript available at

http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/Bernanke20070605a.htm); Ben S.

Bernanke, Chairman, Fed. Reserve Bd., The Subprime Mortgage Market, Remarks at the

Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago’s 43rd Annual Conference on Bank Structure and

Competition (May 17, 2007) [hereinafter Bernanke, Subprime Market] (transcript

available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/Bernanke20070517a.htm).

25. See, e.g., A

M. SECURITIZATION FORUM, STATEMENT OF PRINCIPLES,

RECOMMENDATIONS AND GUIDELINES FOR THE MODIFICATION OF SECURITIZED SUBPRIME

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE LOANS 1 (2007), http://www.americansecuritization.com/

uploadedFiles/ASF Subprime Loan Modification Principles_060107.pdf [hereinafter

F

ORUM] (noting the “broader environment for subprime loans: an increase in delinquency,

default and foreclosure rates; a decline in home price appreciation rates; a prevalence of

loans with a reduced introductory rate that will soon adjust to a higher rate; and a

reduced availability of subprime mortgage lending for refinancing purposes”); Gretchen

Morgenson, Bear Stearns Says Battered Hedge Funds are Worth Little, N.Y.

TIMES, July

18, 2007, at C2.

26. T

HE CTR. FOR STATISTICAL RESEARCH INC., U.S. MORTGAGE BORROWING:

PROVIDING AMERICANS WITH OPPORTUNITY, OR IMPOSING EXCESSIVE RISK? 11–12 (2007),

available at https://www.afsaonline.org/CMS/fileREPOSITORY/Foreclosure%20Study%

20CSR%20May%202007%20FINAL.pdf [hereinafter M

ORTGAGE BORROWING] (describing

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

2008] AN APPROACH TO FORECLOSURE REFORM 689

foreclosures has been rising over the last ten years and especially

recently. The number of mortgages entering foreclosure rose from

0.35% in the second quarter of 1997

27

to 0.99% in the first quarter

of 2008, which was the highest foreclosure rate in more than

twenty-five years.

28

Subprime lending has driven this rise in foreclosures.

29

Subprime loans are designed for borrowers who have

characteristics that suggest a poorer credit risk.

30

Subprime

borrowers pay higher interest rates, higher loan fees, or both, in

order to compensate lenders for the greater risk of default.

31

Only

14% of mortgages are subprime loans, yet subprime loans

constitute over 64% of the loans in foreclosure.

32

Subprime lending has long been associated with deceptive

and unfair sales practices.

33

State attorneys general cooperated in

a series of cases against some of the largest subprime mortgage

lenders, alleging violations of consumer protection laws. These

cases resulted in settlements costing these lenders approximately

$850 million in restitution to homeowners.

34

Subprime lending

the three most common means of measuring the number of foreclosures and the rate of

change in foreclosure activity). There is some indication that the most commonly cited

sources may grossly undercount foreclosures. See, e.g., Steve Alexander & Jim Buchta,

Foreclosures Taking a Bigger Toll Across Minnesota, S

TAR TRIB. (Minneapolis), Aug. 2,

2007, at D1 (reporting that the 11,207 actual count of foreclosure sales in Minnesota in

2006 were almost twice the number reported by RealtyTrac based on mortgage industry

reporting).

27. See U.S. Dep’t of Housing & Urban Dev., U.S. Housing Market Conditions

National Data: Housing Finance, Fall 1997, available at http://www.huduser.org/

periodicals/USHMC/fall97/nd_hf.html (reporting the MBA delinquency survey for the 2Q

of 1997).

28. Press Release, Mortgage Bankers Assoc., Delinquencies Decrease in Latest

MBA National Delinquency Survey (June 14, 2007), available at

http://www.mortgagebankers.org/NewsandMedia/PressCenter/55132.htm (announcing the

results of the MBA national delinquency survey).

29. See C

TR. FOR RESPONSIBLE LENDING, A SNAPSHOT OF THE SUBPRIME MARKET 1

(2007), http://www.responsiblelending.org/pdfs/snapshot-of-the-subprime-market.pdf.

30. Patricia A. McCoy, Rethinking Disclosure in a World of Risk-based Pricing, 44

H

ARV. J. ON LEGIS. 123, 126 (2007).

31. See id. at 126–27 (observing that the amount of higher loan rates and charges

are theoretically correlated to the risk presented by the borrower’s characteristics, but

loan pricing does not always follow this model in practice).

32. C

TR. FOR RESPONSIBLE LENDING, supra note 29, at 3.

33. Up to 25% of Subprime Losses Blamed on Fraud, I

NSIDE B & C LENDING, Nov. 5,

2007, at 5 (finding indications of fraud in almost every subprime loan file examined); see

Heather M. Tashman, The Subprime Lending Industry: An Industry in Crisis, 124

B

ANKING L.J. 407, 407–08, 413–14 (2007) (describing skepticism toward subprime lending

and the congressional response).

34. See, e.g., Michelle Singletary, Taming the Predators, W

ASH. POST, Jan. 29, 2006,

at F1 (noting the $325 million dollar settlement with Ameriquest and the agreement to

avoid predatory practices); Mark Skertic, Household Settles Class-action Suits for $100

Million, C

HI. TRIB., Nov. 26, 2003, § 3, at 1 (stating that the lender had reached a $484

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

690 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

has been associated with interest rates and loan fees

disproportionate to the risk of the loan, deceptive representations

as to the terms of the loans, appraisals inflated beyond fair

market value, servicing abuses, and a range of other unfair and

deceptive practices.

35

The vast majority of subprime mortgage loans are sold by

the entity that originates the loan into the secondary market for

“mortgage-backed securities.”

36

This shifting of risk from the

originator of the loan to investors in securities comprised of these

loans fueled the rapid expansion of the subprime market.

37

Unfortunately, securitization has also likely encouraged many of

the unfair and deceptive practices.

38

The regulatory structures

erected in previous generations, including disclosure

requirements and bank supervision, do not fit well with and do

not effectively control the problems created in a world of

expansive mortgage lending, especially when that lending occurs

through securitized financing.

39

While foreclosure rates vary by region, the relationship

between subprime lending and drastically higher foreclosure

rates is well established.

40

Subprime mortgages accounted for

million settlement with state Attorneys General); Press Release, Fed. Trade Comm’n,

Subprime Loan Victims to Receive Consumer Redress (Dec. 19, 2002) (stating that $60

million or more would be distributed to homeowners as a result of settlement between

First Alliance Mortgage Company and the Federal Trade Commission, state attorneys

general, and private plaintiffs). The Author notes that he was substantially involved in

the leadership of all of these cases as an assistant attorney general in the Minnesota

Attorney General’s Office.

35. See Kurt Eggert, Limiting Abuse and Opportunism by Mortgage Servicers, 15

H

OUSING POL’Y DEBATE 753, 756–61 (2004) (describing servicing abuses in the subprime

mortgage industry); Kathleen C. Engel & Patricia A. McCoy, Turning a Blind Eye: Wall

Street Finance of Predatory Lending, 75 F

ORDHAM L. REV. 2039, 2043–45 (2007) (giving

examples of predatory lending practices).

36. Engel & McCoy, supra note 35, at 2045.

37. Id. at 2045, 2049.

38. T

HE REINVESTMENT FUND, MORTGAGE FORECLOSURE FILINGS IN PENNSYLVANIA

71–72 (2005), http://www.trfund.com/resource/downloads/policypubs/Mortgage-Forclosure-

Filings.pdf [hereinafter P

ENNSYLVANIA]; Bernanke, Subprime Market, supra note 24, at 3

(“[T]he practice of selling mortgages to investors may have contributed to the weakening

of underwriting standards.”).

39. See Engel & McCoy, supra note 35, at 2080–81 (arguing that disclosure laws do

not effectively address predatory lending problems with subprime borrowers);

Christopher L. Peterson, Predatory Structured Finance, 28 C

ARDOZO L. REV. 2185, 2255–

63 (2007) (describing the inadequacy of current consumer protection laws in providing

recourse against lending abuses with securitized financing).

40. See M

ARK DUDA & WILLIAM C. APGAR, NEIGHBORWORKS AM., MORTGAGE

FORECLOSURES IN ATLANTA: PATTERNS AND POLICY ISSUES 1, 7 (2005),

http://www.nw.org/Network/neighborworksProgs/foreclosuresolutionsOLD/documents/fore

closure1205.pdf (finding high foreclosure areas have approximately four times the level of

nonprime loans); P

ENNSYLVANIA, supra note 38, at 27–32 (“[I]t is the subprime foreclosure

rate that is driving rising foreclosure filings [in Pennsylvania].”); E

LLEN SCHLOEMER ET

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

2008] AN APPROACH TO FORECLOSURE REFORM 691

more than half of all foreclosures initiated in the last quarter of

2006.

41

A study by the Center for Responsible Lending estimates

that more than 15% of all subprime, first-lien, and owner-

occupied mortgage loans made between 1998 and 2006 will end

in foreclosure.

42

Specific loan terms that are far more prevalent in the

subprime lending market are particularly correlated with higher

foreclosure rates.

43

Failure to verify a borrower’s income, loans at

very high loan-to-value ratios (i.e., little or no equity), and

interest only or negative amortizing loans all indicate a much

higher probability of foreclosure.

44

Subprime loans made recently

are significantly more likely to enter foreclosure because the risk

profile of subprime loans began to worsen as lending volume was

skyrocketing in the last few years.

45

By 2006, almost 80% of

subprime loans were adjustable rate,

46

and about half of all

subprime loans were based on no documentation or limited

documentation.

47

Federal financial regulators have recently

AL., CTR. FOR RESPONSIBLE LENDING, LOSING GROUND: FORECLOSURES IN THE SUBPRIME

MARKET AND THEIR COST TO HOMEOWNERS 5 (2006), http://www.responsiblelending.org/

pdfs/CRL-foreclosure-rprt-1-8.pdf; Engel & McCoy, supra 35, at 2042; Anne Balcer

Norton, Reaching the Glass Usury Ceiling: Why State Ceilings and Federal Preemption

Force Low-Income Borrowers into Subprime Mortgage Loans, 35

U. BALT. L. REV. 215, 221

(2005) (describing the continuing growth in foreclosures caused by the increase in

subprime lending and the consequences); Pamela Prah, Ohio Tries to Fend Off

Foreclosures on Home Loans, S

TATELINE.ORG, Apr. 23, 2007, http://www.stateline.org/

live/details/story?contentId=201186.

41. Bernanke, Subprime Market, supra note 24.

42. S

CHLOEMER ET AL., supra note 40, at 15–16 (citing two recent studies with

results reflecting the relationship between the rate of foreclosure among subprime

borrowers); see also Kristopher Gerardi, Adam Hale Shapiro & Paul S. Willen, Subprime

Outcomes: Risky Mortgages, Homeownership Experiences, and Foreclosures 1 (Fed.

Reserve Bank of Boston, Working Paper No. 07–15, 2008), available at

http://www.bos.frb.org/economic/wp/wp2007/wp0715.pdf (concluding that almost 20% of

homeowners who used a subprime mortgage to obtain a home eventually will enter

foreclosure, which is six times the rate for prime mortgages). But see M

ORTGAGE

BORROWING, supra note 26, at 9–28 (arguing that foreclosure rates are not rising as

rapidly as suggested by the CRL study, but noting that subprime loans enter foreclosure

at a rate four times or more higher than the rate for prime loans).

43. S

CHLOEMER ET AL., supra note 40, at 5.

44. Id.

45. Id. at 15–16 (estimating that over 19% of subprime loans made in 2005 or

2006 will enter foreclosure); I

VY L. ZELMAN ET AL., CREDIT SUISSE, MORTGAGE

LIQUIDITY DU JOUR: UNDERESTIMATED NO MORE 46 (2007), http://www.recharts.com/

reports/CSHB031207/CSHB031207.pdf.

46. Sandra L. Thompson, Dir., Div. of Supervision and Consumer Prot., Fed.

Deposit Ins. Corp., Mortgage Market Turmoil: Causes and Consequences,

Statement

Before Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, U.S. Senate

(Mar. 22, 2007)

(transcript available at http://www.fdic.gov/news/news/speeches/archives/2007/

chairman/spmar22071.html) (“[N]early 80% of securitized subprime loans were ARMs by

early 2006.”).

47. Z

ELMAN ET AL., supra note 45, at 4 (“2006 subprime purchase originations

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

692 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

acknowledged the high risk factors and poor underwriting

quality of many subprime loans.

48

A report from a major

investment banking firm discussing weakening underwriting

standards in the subprime mortgage lending industry quoted a

private builder as reporting that “anybody with a pulse that was

interested in buying a home was able to get financing” during

2006.

49

The current foreclosure rise is unlikely to make a single pass

and quickly recede back to historic levels.

50

The foreclosure

problem in 2006 and 2007 does not account for a bulge of

subprime adjustable rate loans that are “re-setting” to a higher

interest rate through mid-2008.

51

Furthermore, the explosion in

subprime lending starting in 2004 was accompanied by an

equally dramatic increase in risky “nontraditional” mortgage

products in the prime or near-prime mortgage loan market.

52

This

segment of the market grew from about 2% of new mortgage

originations in 2003 to about 18% for 2006.

53

In late July 2007,

the nation’s largest mortgage lender announced a significant

increase in loan defaults in both subprime and prime loans, with

subprime default rates increasing from 13.4% to over 20% from

posted an alarming 94% combined loan to value ratio.”).

48. See Bernanke, Housing Market, supra note 24 (stating that some of the increase

in subprime delinquency is likely the result of looser underwriting standards); Bernanke,

Subprime Markets, supra note 24; John C. Dugan, Comptroller of the Currency, Remarks

Before the National Foundation for Credit Counseling Spring Meeting 1–2 (Apr. 24, 2007)

(transcript available at http://www.occ.treas.gov/ftp/release/2007-44a.pdf) (“[W]e now

know that the increase in subprime lending also reflects the fact that some lenders have

been making loans that borrowers have no realistic prospect of repaying.”).

49. Z

ELMAN ET AL., supra note 45, at 24, 50 (noting a major issue in the subprime

industry is “inflated appraisal values” resulting from “lax appraisal methods”); see also

T

HOMAS BIER & IVAN MARIC, ARGENT MORTGAGE COMPANY LENDING AND FORECLOSURE

ACTIVITY CUYAHOGA COUNTY, OHIO (2007) (linking subprime loan originations that result

in foreclosure with unrealistically high property values) (on file with the Houston Law

Review); Bernanke, Housing Market, supra note 24; Bernanke, Subprime Market, supra

note 24 (stating that some of the increase in subprime delinquency is likely the result of

looser underwriting standards).

50. See generally Karen Weaver, Katie Reeves & Art Frank, The Subprime

Mortgage Crisis and Potential Government Action, Sept. 7, 2007 (describing the long term

problems in the subprime market).

51. See Z

ELMAN ET AL., supra note 45, at 46–47; Weaver et al., supra note 50, at 3.

52. See Z

ELMAN ET AL., supra note 45, at 29–38.

53. Thompson, supra note 46, at 2–4; Vikas Bajaj, Defaults Rise in Next Level of

Mortgages, N.Y.

TIMES, Apr. 10, 2007, at C1. This part of the market is known as “Alt-A”

loans, which includes lending to borrowers with slightly impaired credit and borrowers

with prime credit but who obtain more risky forms of adjustable rate loans, such as an

“option ARM” that allows the borrower the choice of paying less than the amount needed

to amortize the loan. Together, subprime and Alt-A lending at these substantial levels

represents an unprecedented increase in the risk profile of residential mortgage lending.

See Z

ELMAN ET AL., supra note 45, at 1 (pointing out that together subprime and Alt-A

mortgage lending accounted for about 40% of all new mortgage originations in 2006).

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

2008] AN APPROACH TO FORECLOSURE REFORM 693

the same period in 2006, and defaults on home equity loans to

borrowers with “good credit” more than doubling from 2.2% to

5.4% for the same period in 2006.

54

Financial markets responded

by plummeting worldwide.

55

B. Impact of Rising Foreclosures on Communities

Foreclosure affects people with no direct relation to the

mortgage transaction, including neighboring homeowners,

renters, and municipalities.

56

This Subpart examines the effect of

increased foreclosures on communities.

1. Concentrated Subprime Mortgage Foreclosures Are

Causing Blight. Subprime lending has been geographically

concentrated, and thus the current wave of foreclosures has been

geographically concentrated.

57

Studies repeatedly show that

foreclosure caused by subprime lending is clustered in poorer and

minority communities.

58

This result has been observed in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania;

59

Atlanta, Georgia;

60

Chicago,

Illinois;

61

Baltimore, Maryland;

62

and Minneapolis–Saint Paul,

54. Vikas Bajaj, Top Lender Sees Mortgage Woes for “Good” Risks, N.Y. TIMES, July

25, 2007, at A1.

55. Floyd Norris & Vikas Rajaj, Global Stock Markets Tumble Amid Deepening

Credit Fears, N.Y.

TIMES, July 27, 2007, at A1.

56. W

ILLIAM C. APGAR & MARK DUDA, HOMEOWNERSHIP PRESERVATION

FOUNDATION, COLLATERAL DAMAGE: THE MUNICIPAL IMPACT OF TODAY’S MORTGAGE

FORECLOSURE BOOM 4–7 (2005), http://nw.org/network/neighborworksprogs/

foreclosuresolutionsOLD/documents/Apgar-DudaStudyFinal.pdf (identifying actors

outside the mortgage foreclosure and how they are impacted by the process).

57. P

ENNSYLVANIA, supra note 38, at 37. (“[T]he pattern of differences across

counties is fairly consistent—areas with more highly clustered foreclosures tend to be

areas with lower than average housing values, lower than average family incomes, higher

than average percentages Black or African American and higher than average

percentages Hispanic.” (emphasis omitted)).

58. Id.

59. Id.

60. See D

EBBIE GRUENSTEIN & CHRISTOPHER E. HERBERT, THE NEIGHBORHOOD

REINVESTMENT CORP., ANALYZING TRENDS IN SUBPRIME ORIGINATIONS AND

FORECLOSURES: A CASE STUDY OF THE ATLANTA METRO AREA, at ii, 3 (2000), available at

http://www.abtassociates.com/reports/20006470781991.pdf (analyzing HDMA data which

shows that “[i]n very low-income neighborhoods, subprime lenders accounted for 37

percent of all originations in 1997—3 times the subprime market share in the Atlanta

area overall”); Bajaj, supra note 19.

61. See D

AN IMMERGLUCK & GEOFF SMITH, WOODSTOCK INST., RISKY BUSINESS—AN

ECONOMETRIC ANALYSIS OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SUBPRIME LENDING AND

NEIGHBORHOOD FORECLOSURES 12–23 (2004), available at http://www.woodstockinst.org/

document/riskybusiness.pdf.

62. See T

HE REINVESTMENT FUND FOR THE GOLDSEKER FOUND., MORTGAGE

FORECLOSURE FILINGS IN BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 19 (2006), available at

http://www.nw.org/Network/neighborworksProgs/foreclosuresolutionsOLD/documents/mar

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

694 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

Minnesota.

63

The concentration of subprime foreclosures in

certain neighborhoods magnifies the deleterious impact of

foreclosures on the community.

64

The value of housing decreases in direct correlation to

proximity of foreclosed properties.

65

A study in Chicago

established a decrease in home values of 1.14% for homes within

one-eighth of a mile from a foreclosure and a decrease of 0.325%

for homes within one-fourth of a mile of a foreclosure.

66

The loss

of housing value associated with foreclosures worsens when

considering only low and moderate income tracts where

foreclosures are concentrated.

67

Foreclosure leads to a higher number of vacant and

abandoned properties.

68

Vacant properties degrade the quality of

life for neighbors; they are a “curse” on the livability of a

ylandForeclosuresIn2006.pdf [hereinafter BALTIMORE].

63. See I

NST. ON RACE & POVERTY, COMMUNITIES IN CRISIS: RACE AND MORTGAGE

LENDING IN THE TWIN CITIES 2–3 (Aug. 6, 2008) (draft report on file with the Houston

Law Review); M

ICHAEL GROVER ET AL., TARGETING FORECLOSURE INTERVENTIONS: AN

ANALYSIS OF NEIGHBORHOOD CHARACTERISTICS ASSOCIATED WITH HIGH FORECLOSURE

RATES IN TWO MINNESOTA COUNTIES 3, 4 (2007), available at http://www.chicagofed.org/

cedric/2007_res_con_papers/car_55_grover_targeting_foreclosure_interventions_revised_f

or_the_conf_1_12_2007.pdf; Jeff Crump, Subprime Lending in Hennepin and Ramsey

Counties: An Empirical Analysis, 35 C

URA REP., Spring 2005, at 18, available at

http://www.cura.umn.edu/reporter/05-Spr/Crump.pdf.

64. Kathleen C. Engel, Do Cities Have Standing? Redressing the Externalities of

Predatory Lending, 38 C

ONN. L. REV. 355, 357–60 (2006).

65. See C

TR. FOR RESPONSIBLE LENDING, SUBPRIME SPILLOVER 1 (2007), available at

http://www.responsiblelending.org/pdfs/subprime-spillover.pdf (estimating that 40.6

million homeowners not in foreclosure will lose property value as a result of foreclosures

of subprime mortgages); D

AN IMMERGLUCK & GEOFF SMITH, WOODSTOCK INST., THERE

GOES THE NEIGHBORHOOD: THE EFFECT OF SINGLE-FAMILY MORTGAGE FORECLOSURES ON

PROPERTY VALUES 8–9 (2005), available at http://www.woodstockinst.org/publications/

download/there-goes-the-neighborhood%3a-the-effect-of-single%11family-mortgage-

foreclosures-on-property-values/.

66. See I

MMERGLUCK & SMITH, supra note 65, at 8–9 (estimating that the average

Chicago home would lose $1,870 when the foreclosure was within one-eighth of a mile);

see also Robert A. Simons, Roberto G. Quercia & Ivan Maric, The Value Impact of New

Residential Construction and Neighborhood Disinvestment on Residential Sales Price, 15

J.

REAL EST. RES. 147, 158 (1998) (stating that the value of a home falls $788 within two

blocks of tax delinquent homes).

67. See, e.g., I

MMERGLUCK & SMITH, supra note 65, at 9 (noting that homes within

one-eighth of a mile of foreclosure lose 1.8% of their value for lower-income census tracts).

68. See Ronald H. Silverman, Toward Curing Predatory Lending, 122 B

ANKING L.J.

483, 530 (2005) (“A relatively large number of foreclosures in a low-income neighborhood

may lead to abandonments.”); Edward M. Gramlich, Governor, Fed. Reserve Bd.,

Remarks at the Financial Services Roundtable Annual Housing Policy Meeting (May 21,

2004) (transcript available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/

2004/20040521/default.htm) (discussing the link between subprime lending and

foreclosure rates and stating that “[t]here is . . . evidence of serious neighborhood blight if

foreclosure rates, and abandoned properties, proliferate in a given city area”).

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

2008] AN APPROACH TO FORECLOSURE REFORM 695

community.

69

A study of vacancies in Austin, Texas, found that

crime rates on blocks with vacant properties were about twice as

high as blocks with similar demographics and no vacant

buildings.

70

Vacant properties result in arson and health

problems resulting from “trash, illegal dumping, and rodent

infestations.”

71

Home values also sink substantially in direct

proportion to the distance from a vacant home.

72

Vacant

properties can increase the cost of home insurance.

73

Foreclosures also have substantial negative consequences for

municipal governments.

74

Foreclosures and vacant properties simultaneously increase

city costs while decreasing revenue.

75

Municipal costs may

include increased policing and fire response, demolition,

inspection, and administrative burdens.

76

A study of municipal

expense in dealing with foreclosed vacant properties in Chicago

estimated that the net municipal cost of dealing with each

property range from $430 to $34,199 based on five typical

scenarios.

77

At the same time that municipalities confront these

costs, declining home values as a result of vacant properties

erode the tax base.

78

The concentration of subprime lending in

certain neighborhoods has led to a concentration of vacant

properties that is causing neighborhood deterioration and

overwhelming the ability of municipal governments to manage

the problem.

79

69. See NAT’L VACANT PROPS. CAMPAIGN, VACANT PROPERTIES: THE TRUE COSTS TO

COMMUNITIES 1 (2005), available at http://www.vacantproperties.org/latestreports/

True%20Costs_Aug05.pdf [hereinafter V

ACANT PROPERTY].

70. See William Spelman, Abandoned Buildings: Magnets for Crime?, 21 J.

CRIM.

JUST. 481, 484–85, 489–90 (1993); cf. VACANT PROPERTY, supra note 69, at 3 (citing a

study of Richmond, Virginia, in which vacant buildings were the highest correlated to

crime of all factors studied).

71. V

ACANT PROPERTY, supra note 69, at 4–5 (citing a report from the U.S. Fire

Administration reporting over 12,000 fires in vacant properties each year).

72. Id. at 9.

73. Id. at 11.

74. See generally Engel, supra note 64, at 357–60 (describing the negative impacts

of foreclosure on providers of municipal services).

75. Id. at 358–59.

76. A

PGAR & DUDA, supra note 56, at 6 (“For municipalities, foreclosures trigger

significant direct expenditures for increased policing and fire suppression, demolition

contracts, building inspections, legal fees, and expenses associated with managing the

foreclosure process (e.g., recordkeeping/updating).”).

77. W

ILLIAM C. APGAR, MARK DUDA & ROCHELLE NAWROCKI GOREY, HOMEOWNERSHIP

PRESERVATION FOUND., THE MUNICIPAL COST OF FORECLOSURES: A CHICAGO CASE STUDY

23 (2005), available at http://www.nw.org/network/neighborworksProgs/

foreclosuresolutions/documents/2005Apgar-DudaStudy-FullVersion.pdf.

78. See A

PGAR & DUDA, supra note 56, at 6; VACANT PROPERTY, supra note 69, at 9.

79. See, e.g., Municipalities Struggle with Foreclosed Houses, C

ASCADE, Fall 2007,

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

696 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

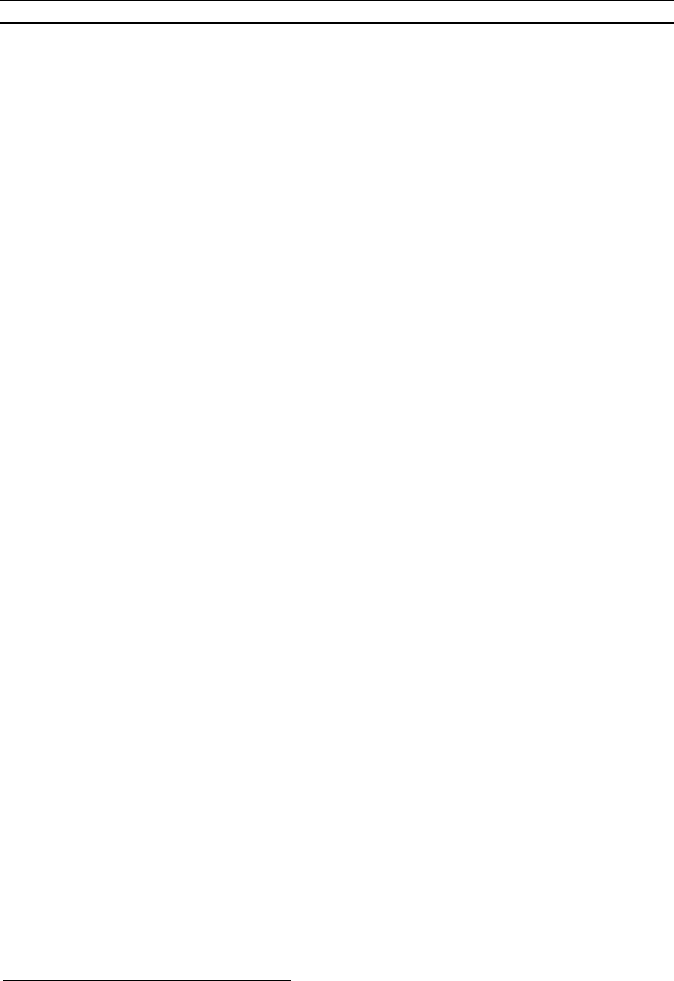

2. Metropolitan Example: Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Hennepin County, Minnesota, which includes Minneapolis, is a

relatively prosperous and stable urban area. It also has

neighborhoods that are being devastated by foreclosures. The

following chart shows foreclosure sales

80

and related economic

data

81

from 1988 through 2007:

Hennepin County Foreclosures and Economic Data, 1988-2007

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

1

98

8

198

9

1

99

0

1991

1992

199

3

1994

199

5

1

99

6

1

99

7

1998

1

99

9

2000

200

1

200

2

200

3

200

4

2

00

5

2006

2

00

7

# of Foreclosure Sales

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Interest / Unemployment Rates

Hennepin County Foreclosure Sales

Long Term Rates (Conventional Mortgages)

Hennepin County Unemployment Rate

at 15, available at http://www.philadelphiafed.org/cca/capubs/cascade/66/cascade_no-

66.pdf (describing the problem of concentrated foreclosures in Cleveland and its inner-

ring suburbs).

80. Foreclosure Sale Data is from the records of the Hennepin County Sheriff’s

Office (on file with the Houston Law Review). Foreclosure sales are for year-end 2007. In

Minnesota, the foreclosure sale typically is near the middle of the foreclosure process

because the borrower usually has a six month redemption period during which the

borrower can possess the property. See M

ORTGAGE DIRECTORY, supra note 19, at 1-159–66

(describing Minnesota foreclosure procedures).

81. Unemployment data is from the Minnesota Department of Employment and

Economic Development, http://www.deed.state.mn.us/lmi/tools/laus/detail.asp?geog=

2704000053&adjust=0 (last visited Sept. 5, 2008). Unemployment rate is current as of

May 2007. Conventional mortgage interest rates data is from the Federal Reserve Board,

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/data.htm (last visited Sept. 5, 2008). The

interest rate data is based on June 2007 monthly rates. Similar increases in foreclosure

rates occurred throughout Minnesota starting in 2005. G

REATER MINN. HOUS. FUND &

HOUSINGLINK, FORECLOSURES IN GREATER MINNESOTA: A REPORT BASED ON COUNTY

SHERIFF’S SALES DATA 6–7 (2007), http://www.housinglink.org/adobe/reports/

GreaterMN_Foreclosure_Oct2007_Supplement.pdf (finding a foreclosure sales increase of

48% from 2005 to 2006 in Minnesota outside of the Twin Cities metropolitan area and

projecting a 84% increase from 2006 to 2007).

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

2008] AN APPROACH TO FORECLOSURE REFORM 697

Hennepin County had a steady number of mortgage

foreclosure sales per year from 1988 through 2004, followed by an

extraordinary, more than five-fold increase in foreclosure sales

from 2005 through 2007.

82

Hennepin County provides a good example of the degree of

racial and low income concentration in foreclosures. The

foreclosure rate was 2 per 1,000 loans in census tracks that were

80% or more white, but 26 per 1,000 loans in census tracks 80%

or more non-white, with a straight line increase in foreclosures

as non-white concentration increases in the census track.

83

A

similar strong correlation exists between low income census

tracks and foreclosure rates.

84

III. B

ORROWERS, LENDERS, AND

M

ORTGAGE FORECLOSURE LAW

The rights of parties to a mortgage developed over centuries

of English law as a means to fairly balance the interest of

borrowers and lenders when land ownership is used as security

for a loan.

85

English courts of equity developed the still extant

concept of the equitable right of redemption, which provides that

when a borrower who gave a mortgage defaults on the payment,

he retains the right to pay off the debt for a fixed period after the

default.

86

English courts then created the right of the mortgage

lender to “foreclose” this equitable right to redeem.

87

Ultimately,

lenders and the courts evolved the generally accepted mortgage

foreclosure procedure that has been mostly codified today, which

provides for sale of a property by the lender after compliance

82. Analysis was based on data retrieved from Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office

website, http://www4.co.hennepin.mn.us/webforeclosure/ (last visited Sept. 5, 2008). In

the period from 1988 through 2004, the number of foreclosure sales in Hennepin County

was never more than 32% higher or 24% lower than the average of 1,066 foreclosure sales

per year. Id.

83. Id.; G

ROVER ET AL., supra note 63, at 15, 35; see also INST. ON RACE & POVERTY,

supra note 63, at 2–3; Crump, supra note 63, at 17–18 (demonstrating a statistical link

between race and foreclosure rates).

84. G

ROVER ET AL., supra note 63, at 35.

85. Ann M. Burkhart, Lenders and Land, 64 M

O. L. REV. 249 passim (1999)

(providing a detailed history of the relationship between a borrower and lender in a land

purchase). This Article uses the more easily distinguishable and simple terms “borrower”

and “lender,” rather than “mortgagor” and “mortgagee.” In most cases, the lender is a

mortgagee who has been assigned ownership of the mortgage loan from the originating

lender or another assignee.

86. Id. at 264.

87. Id. at 265–66.

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

698 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

with procedural requirements for terminating the borrower’s

interests.

88

Foreclosure occurs under federal law only for certain

mortgages held by the United States Department of Housing and

Urban Development.

89

Bankruptcy also provides controlling

federal law for those who seek bankruptcy protection during the

proceeding, especially with a Chapter 13 filing.

90

State law

nonetheless controls the overwhelming majority of foreclosures.

91

Many transactions governed primarily by state law either

strive for uniformity or are generally recognizable from state to

state.

92

Contract disputes, for example, are settled under widely-

held common law tenets or the Uniform Commercial Code.

93

State

foreclosure laws do not adhere to this pattern.

94

Foreclosure laws

vary dramatically in both substantive rights of the parties and in

the procedures used to complete the process.

95

Attempts to enact uniform state foreclosure laws have been

an abysmal failure.

96

88. Id. at 265–67.

89. Multifamily Mortgage Foreclosure Act, 12 U.S.C. § 3701 (2006); Single Family

Mortgage Foreclosure Act, 12 U.S.C. § 3751 (2006).

90. See Melissa B. Jacoby, Bankruptcy Reform and Homeownership Risk, 2007 U.

ILL. L. REV. 323, 327–28 (2007). Legislation currently pending in the United States

Congress would make it easier for homeowners to file for Chapter 13 bankruptcy

protection by deleting the current prohibition on loan modifications for residential

mortgage loans. See H.R. Res. 3609, 110th Cong. (2007).

91. See Grant S. Nelson & Dale A. Whitman, Reforming Foreclosure: The Uniform

Nonjudicial Foreclosure Act, 53 D

UKE L.J. 1399, 1415 (2004) (describing federal

foreclosure laws, but noting that mortgage law remains largely the province of the states);

Debra Pogrund Stark, Foreclosing on the American Dream: An Evaluation of State and

Federal Foreclosure Laws, 51 O

KLA. L. REV. 229, 238–42 (1998) (describing various federal

laws governing foreclosure).

92. See generally Fred H. Miller & Albert J. Rosenthal, Uniform State Laws: A

Discussion Focused on Revision of the Uniform Commercial Code, 22 O

KLA. CITY U. L.

REV. 257, 262–64 (discussing the process of creating uniformity in state law).

93. Id. at 320; see also Robert F. Blomquist, Ten Vital Virtues for American Public

Lawyers, 39 I

ND. L. REV. 493, 498 (2006) (indicating the interaction of the common law

and Uniform Commercial Code in contract law).

94. See, e.g., Grant S. Nelson, A Commerce Clause Standard for the New

Millennium: “Yes” to Broad Congressional Control over Commercial Transactions; “No” to

Federal Legislation on Social and Cultural Issues, 55 A

RK. L. REV. 1213, 1244–45 (2003)

(detailing the diverse and nonuniform state approaches to foreclosure law).

95. See Nelson & Whitman, supra note 91, at 1401 (“Mortgage law varies

enormously from state to state and represents an often perplexing amalgam of English

legal history, common law, and legislation.”). See generally M

ORTGAGE DIRECTORY, supra

note 19 (cataloging the varying requirements of each state foreclosure law); R

AO ET AL.,

supra note 21, at § 1.3.1.2, app. C (noting the variability of state foreclosure laws and

cataloging the varying requirements of each state law).

96. Nelson & Whitman, supra note 91, at 1408–09. There have been numerous attempts

at uniform state law promulgation through the National Conference of Commissioners on

Uniform State Laws, including the Uniform Real Estate Mortgage Act (1927); the Model Power

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

2008] AN APPROACH TO FORECLOSURE REFORM 699

Subpart A of this section describes the basic elements that

can be found in various state foreclosure laws. Subpart B looks at

how the existence and arrangement of different elements in

various state foreclosure laws creates vastly different incentives

for the parties in a foreclosure proceeding. Subpart C examines

the incentives and options for borrowers and for lenders in

dealing with mortgage default and foreclosure.

A. Elements of State Foreclosure Laws

The common denominator in state foreclosure laws is some

form of notice to some interested party or parties.

97

Not much else

can be said to unite the bewildering diversity in both substantive

rights of the parties and the procedures required to complete the

foreclosure.

98

1. Judicial Versus Nonjudicial Procedures. The primary

procedural difference between state foreclosure laws is whether

the jurisdiction requires judicial action.

99

In states with “judicial

foreclosure,” the process usually starts with a summons and

complaint and requires a court order prior to the sale of the

mortgaged property.

100

Judicial foreclosure procedures generally

are more costly for the lender and take much longer to

complete.

101

While nominally a court-supervised process,

borrowers routinely fail to appear and the proceedings typically

are resolved by default.

102

of Sale Foreclosure Act (1940); the Uniform Land Transactions Act (1975); and the Uniform

Land Security Interest Act (1985). No state adopted any of these proposed uniform laws. Id. at

1407–09, 1408 n.49. In 2002, the Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws tried

with the Uniform Nonjudicial Foreclosure Act. See U

NIF. NONJUDICIAL FORECLOSURE ACT

(2002) [hereinafter UNFA] (The act was printed in the Uniform Laws Annotated at 14 U.L.A.

131 (2005)). Efforts to enact federal foreclosure laws also have been unsuccessful. Janet A.

Flaccus, Pre-Petition and Post-Petition Mortgage Foreclosures and Tax Sales and the Faulty

Reasoning of the Supreme Court, 51 A

RK. L. REV. 25, 46 (1998) (noting two failed attempts by

the Senate to add protections for mortgage foreclosure buyers).

97. Basil H. Mattingly, The Shift from Power to Process: A Functional Approach to

Foreclosure Law, 80 M

ARQ. L. REV. 77, 93–94 (1996) (describing the foreclosure process

and how it may vary from state to state).

98. Id.; see also Nelson, supra note 94, at 1243–45.

99. Mattingly, supra note 97, at 92. (“[F]oreclosure models may be divided into two

broad categories: judicial foreclosures and nonjudicial foreclosures.”).

100. See G

RANT S. NELSON & DALE A. WHITMAN, REAL ESTATE FINANCE LAW § 7.11

(4th ed. 2001); see, e.g., M

ORTGAGE DIRECTORY, supra note 19, at 208–10 (describing

initiation of a judicial foreclosure action in New York).

101. See Nelson & Whitman, supra note 91, at 1403 (reviewing the basic judicial

foreclosure process and highlighting the inherent delays and costs); see also Stark, supra

note 91, at 232 (contrasting judicial and nonjudicial foreclosures and emphasizing the

time and cost advantages in nonjudicial foreclosures).

102. See Stark, supra note 91, at 244 (finding that in only 1% of the 1993 cases and in

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

700 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

States permitting nonjudicial foreclosure are said to use a

“power of sale” process whereby the lender, or a trustee, is

allowed to conduct a foreclosure sale without court involvement

after sending the required notices.

103

About thirty states permit

power of sale foreclosure.

104

States allowing power of sale

foreclosure also have judicial procedures available to the lender,

although they are rarely used in most states.

105

Two New

England states primarily employ different forms of “strict

foreclosure” that can allow the foreclosing lender to avoid the sale

procedure and just take title to the property.

106

2. Notice Requirements. Notice in states with judicial

foreclosure follows the form of notice in a civil action.

107

States

with power of sale foreclosure generally use either a one-notice

system or a two-notice system.

108

Both systems require a notice of

foreclosure, but the two-notice system requires a prior notice of

default, typically accompanied by a right to reinstate the loan by

paying the arrearage.

109

The name and contents of the notices,

the timing requirements, the methods of service, and the people

who must be served vary widely among the states.

110

Alabama, for

example, requires only one “Notice of Sale” that must be

published once a week for three consecutive weeks.

111

California

none of the 1994 cases in the Empirical Study did the borrower raise a defense to the

foreclosure action in the judicial proceeding); see also Julia Patterson Forrester, Constructing a

New Theoretical Framework for Home Improvement Financing, 75 O

R. L. REV. 1095, 1131–32

(1996) (detailing propensity of consumers sued by their creditors to default, although

homeowners would be more likely to appear at a hearing than sue for an injunction).

103. N

ELSON & WHITMAN, supra note 100, at § 7.19. A prerequisite to nonjudicial

foreclosure is that the mortgage note allows for the lender to liquidate the real property

through a sale process. Brandon Bennet, Secured Financing in Russia: Risks, Legal

Incentives, and Policy Concerns, 77 T

EX. L. REV. 1443, 1466 (1999) (asserting that power

of sale provisions are required for nonjudicial foreclosures). Standard loan documents in

states permitting a power of sale all contain this type of authority. See, e.g., M

ORTGAGE

DIRECTORY, supra note 19, passim (describing the prevalence of nonjudicial foreclosure in

certain states and the power of sale clauses regularly used in financing documents); R

AO

ET AL

., supra note 21, at § 4.2.3 (explaining that twenty-six states use nonjudicial

foreclosure based on power of sale clauses in mortgages and deeds of trust).

104. N

ELSON & WHITMAN, supra note 100, at § 7.19.

105. See M

ORTGAGE DIRECTORY, supra note 19, passim (describing nonjudicial foreclosure

processes in certain states and noting that judicial proceedings are only used if there is a defect

in the financing documents or if there is some other unusual circumstance).

106. Id. at § 7.9.

107. Nelson & Whitman, supra note 91, at 1403.

108. UNFA, supra note 96, at 4.

109. Id.

110. R

AO ET AL., supra note 21, at app. C (describing the notice requirements in each

state foreclosure law).

111. A

LA. CODE § 35-10-13 (LexisNexis 1996); MORTGAGE DIRECTORY, supra note 19,

at 2.

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

2008] AN APPROACH TO FORECLOSURE REFORM 701

law provides for a two-notice system.

112

The Notice of Default

must contain specified information, including the amount

necessary to cure the default, must be recorded, and must be

served by first class and certified mail.

113

The Notice of Sale must

be publicly posted, published, and served at least twenty days

before the foreclosure sale.

114

3. Foreclosure Sale Procedures. The typical foreclosure sale

is not a scene from movie lore with an excited mob on the

courthouse steps or at the foreclosed property. Some foreclosure

sales have multiple potential bidders.

115

In other situations, the

sale of the property occurs at the local sheriff’s office with only

the lender, perhaps the borrower, and the selling official

present.

116

While the lender can make a credit bid, offering up to

the amount it is owed, other purchasers typically are required to

provide cash.

117

The highest “bidder” at a foreclosure sale often is

the lender.

118

For a variety of reasons, the foreclosure sale rarely

brings a market price.

119

The foreclosure sale itself does not differ

simply because the state uses judicial foreclosure as opposed to

power of sale procedures, although the validity of the sale may be

more questionable in a power of sale process.

120

4. Borrower Redemption and Reinstatement Rights.

Borrowers also have important substantive rights provided by

112. CAL. CIV. CODE § 2924(a) (West 1993 & Supp. 2008).

113. C

AL. CIV. CODE § 2924(a)(1) (West 1993 & Supp. 2008); MORTGAGE DIRECTORY,

supra note 19, at 34.

114. C

AL. CIV. CODE §§ 2924(a)(3), 2924(f) (West 1993 & Supp. 2008); MORTGAGE

DIRECTORY, supra note 19, at 34.

115. See, e.g., Bajaj, supra note 19 (describing the strong interest at one foreclosure

sale in Atlanta, where more than 200 people came out to the auction).

116. Evan H. Krinick, Deposits by Bidders at a Sheriff’s Sale, 117 B

ANKING L.J. 446,

446–50 (2000) (detailing the process of the sheriff’s sale).

117. Id. at 446–47.

118. Stark, supra note 18, at 663 (“In most cases, the only people present at the

foreclosure sale are the lender, the borrower, and the party conducting the foreclosure

sale. Third parties successfully bid in only 11.2% of the 1993 judicial sales cases and only

9.6% of the 1994 judicial sales cases.”); Steven Wechsler, Through the Looking Glass:

Foreclosure by Sale as De Facto Strict Foreclosure: An Empirical Study of Mortgage

Foreclosure and Subsequent Resale, 70 C

ORNELL L. REV. 850, 865, 875 (1985) (finding that

in Onondaga County, New York, “[i]n the sample of 118 foreclosure sales, the mortgagee

bid successfully in 91 cases, or seventy-seven percent of the total, and third parties bought

in 27 cases, or twenty-three percent of the total”).

119. Nelson & Whitman, supra note 91, at 1420–23 (describing barriers to obtaining

market price at foreclosure auction and concluding that, “In sum, it would be difficult to

design a sale procedure less apt to result in market prices than the usual foreclosure

auction.”).

120. Mattingly, supra note 97, at 95 (inferring that borrowers more readily question

nonjudicial sales).

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

702 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

foreclosure statutes in many states.

121

Under common law,

foreclosure extinguishes the borrower’s right of redemption in

equity.

122

Statutory redemption rights extend the borrower’s right

to recover the property by paying off the full amount bid at the

foreclosure sale plus additional costs.

123

In most states with a

redemption period, the borrower can maintain possession of the

property during the redemption period.

124

Redemption periods

vary from ten days to two years.

125

Mortgage notes typically provide for acceleration of the full

amount of the loan and unpaid interest within thirty days

following the lender’s notice to the borrower of default.

126

Standard loan documents include a reinstatement right up to a

fixed number of days before the foreclosure sale or until entry of

judgment.

127

Some state foreclosure laws also expressly provide

the right to reinstate the loan by paying the arrearage on the

loan plus some costs.

128

This statutory right of reinstatement

extends up to the date of the foreclosure sale in some states, is

extinguished a number of days prior to the foreclosure sale in

other states, and runs from the notice of default or service of the

complaint in yet other states.

129

Even in the absence of statutory

or contractual rights, many lenders will voluntarily accept

reinstatement prior to the foreclosure sale.

130

5. Antideficiency Protections. As with any other loan, if the

foreclosure sale price is less than the amount the borrower owes,

the borrower can be liable for a deficiency judgment.

131

As with

much of state foreclosure law, the scope and protection against a

121. See generally Mattingly, supra note 97 passim (discussing the rights of the

borrower and the power struggle between borrower and lender).

122. George M. Platt, The Dracula Mortgage: Creature of the Omitted Junior

Lienholder, 67 O

R. L. REV. 287, 293–95 (1988).

123. Id. at 294–96; Nelson & Whitman, supra note 91, at 1404.

124. N

ELSON & WHITMAN, supra note 100, at § 8.4.

125. M

ORTGAGE DIRECTORY, supra note 19, at 1-221, 1-272.

126. Nelson & Whitman,

supra note 91, at 1464.

127. Mattingly, supra note 97, at 86 n.38.

128. Nelson & Whitman, supra note 91, at 1465.

129. See, e.g., M

INN. STAT. ANN. § 580.30 (West 2000) (permitting right to reinstate

up to date of sale); N

EV. REV. STAT. ANN. § 107.080(2)(a) (LexisNexis 2007 & Supp. 2008)

(granting right to reinstate for thirty-five days after notice of default recorded and

served); W

ASH. REV. CODE ANN. § 61.24.090 (West 2004) (allowing borrower to reinstate

until eleven days before foreclosure sale).

130. See S

TATE FORECLOSURE PREVENTION WORKING GROUP, ANALYSIS OF SUBPRIME

MORTGAGE SERVICING PERFORMANCE: DATA REPORT NO. 1 12–13 (2008), available at

http://www.state.ia.us/government/ag/latest_news/releases/feb_2008/Foreclosure_Preventi

on.pdf [hereinafter S

TATE FORECLOSURE GROUP].

131. N

ELSON & WHITMAN, supra note 100, at § 8.

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

2008] AN APPROACH TO FORECLOSURE REFORM 703

deficiency judgment varies widely.

132

Some antideficiency statutes

protect borrowers against any deficiency judgments, while other

states limit the amount of any potential deficiency judgment to

the fair market value of the property.

133

Several states prohibit

deficiency judgments with a power of sale procedure but allow

such an action in a judicial proceeding.

134

As a practical matter,

lenders do not routinely seek or collect on deficiency judgments

against foreclosed borrowers.

135

B. Effect of Varying Foreclosure Laws

The presence, sequencing, and specific terms of these

elements in a state foreclosure law make for drastically different

incentives for the parties to the process.

136

The varying financial

and personal circumstance of borrowers adds another layer of

complexity to the effect of a state law on how borrowers and

lenders will act during foreclosure.

137

Consider an example of two

different borrowers under two different foreclosure laws.

1. Hypothetical Foreclosure Laws in States A and B. State

A has a foreclosure law with the following characteristics:

• Power of sale procedures are allowed with a three

month notice period culminating in a sheriff’s sale;

• A six month statutory redemption period for the

borrower with the right of possession by the

borrower, and then a one week period for each junior

lien holder to exercise redemption rights and pay off

all senior lien holders; and

• An antideficiency provision applicable to all

borrowers if the power of sale process is used, but

deficiency judgments are permitted if a judicial

foreclosure process is selected by the foreclosing

lender.

132. Id. at § 8.3.

133. Id.; James B. Hughes, Jr., Taking Personal Responsibility: A Different View of

Mortgage Anti-Deficiency and Redemption Statutes, 39 A

RIZ. L. REV. 117, 124 (1997).

134. See N

ELSON & WHITMAN, supra note 100, at § 8.3.

135. See Wechsler, supra note 118, at 878 (noting only one deficiency judgment

obtained among “the ninety-four studied cases in which the foreclosure sale left a

deficiency amount . . . and in that case the judgment was not satisfied”); see also Stark,

supra note 91, at 244 (“Lenders brought a deficiency action within one year after the

foreclosure sale in approximately six to seven percent of the foreclosure sale cases.”).

136. See generally Mattingly, supra note 97, at 101–03 (detailing various incentives

and obstacles with respect to foreclosure laws).

137. Id. at 84–89 (hypothesizing about potential complications and frustrations

based on the borrowers’ situations).

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

704 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

The power of sale process in State A typically takes a

minimum of nine months from default, including the six month

redemption period. Although rarely used because of the expense,

State A has an alternative judicial procedure that takes a

minimum of fourteen months from default, including the six

month redemption period after the foreclosure sale.

State B has a foreclosure law with the following

characteristics:

• Power of sale procedures are allowed with a two

month notice period culminating in a sheriff’s sale;

• No statutory redemption period; and

• No antideficiency provision. The amount of the

deficiency (if any) is equal to the amount owed on the

debt minus the foreclosure sale price. Any surplus

from the foreclosure sale is distributed to all the lien

holders in priority order, with any remainder to the

homeowner.

The power of sale process takes a minimum of three months

from default in State B. The alternative judicial foreclosure

procedure in State B typically takes a minimum of nine months

from default, but otherwise the same lack of borrower protections

apply.

2. The Smiths. The Smith family has owned a single family

residence for nine years. The home is worth $235,000, with

selling expenses of about $15,000. The Smiths’ home is

encumbered by a first lien mortgage loan of $175,000. The

Smiths also have a $5,000 judgment against them from a prior

credit card debt. The Smiths, therefore, have about $40,000 in

realizable equity in the property, with $180,000 of encumbrances

on a home worth a net of $220,000 after selling costs.

The Smiths have three children and desperately want to

stay in their current home. Based on their current credit score,

income, and debts, the Smiths qualify for a refinancing loan of

only $125,000 at a high interest rate. Mr. Smith is recovering

from an illness and unemployed. If he can find work in his field,

it is much more likely the Smiths will be able to obtain a loan,

either a refinancing loan or a home equity loan, sufficient to

either reinstate their mortgage in foreclosure or redeem the

property.

The lender foreclosing on the Smiths in State A very likely

will use the quicker, less expensive power of sale procedure. The

foreclosure sale, however, will almost surely consist of only the

bid by the lender for the amount owed, $175,000, because in a

state with a six month redemption period, a party other than the

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

2008] AN APPROACH TO FORECLOSURE REFORM 705

lender would have to make a cash bid at the sale knowing that

the home has a substantial chance of being redeemed because the

borrower has equity in the property. There is little chance for a

third party to make money when he or she has to pay cash for the

home; wait six months and hope that the Smiths do not redeem

or sell the home; that the Smiths’ judgment creditor doesn’t

redeem or sell the judgment to a specialist in foreclosure

purchases who would redeem the property; that the property is

not substantially damaged; and that no other judgment creditors

or lien holders with the intent to redeem appear during the

redemption period. Nor does the lender have an incentive to bid

less than the amount owed to it because there is no prospect of a

deficiency judgment due to antideficiency legislation.

Because their top priority is to stay in the home, the Smiths

likely will pursue reinstatement or refinancing of the loan. After

the foreclosure sale, the Smiths will face difficult decisions

during the six month redemption period. The foreclosure sale will

have resulted in no surplus because the lender will have bid the

amount it was owed, so the end of the redemption period will

mean the Smiths not only lose possession of the home, but also

lose their equity in the property. The longer they wait to sell

their home, the less time they will have to obtain the best price

and liquidate the equity in their home. The Smiths will be

making these pressing choices at a time of extraordinary stress

from lack of employment and income, and very likely managing

debt and debt collectors.

The actions of the lender probably will be no different in

State B. The lender again will use the power of sale procedure. If

the property goes to a foreclosure sale, the lender likely will bid

the amount owed plus costs, as in State A. A higher bid could

result in a surplus due to the Smiths; a lower bid will result in no

gain because any deficiency judgment against the Smiths

probably will be uncollectible and be dischargeable in

bankruptcy.

State B has fewer protections for borrowers, leaving the

Smiths with limited options. The likelihood of the Smiths

retaining their home, their top priority, is substantially less in

State B. Given the much shorter period between default and

dispossession, the Smiths probably will need to immediately put

the house on the market to have a chance of controlling the sale

price and the amount of equity they will receive. If the Smiths

are unable to sell their home before the date of the foreclosure

sale, they will receive a portion of their equity only in the

unlikely event that the foreclosure sale exceeds about 80% of the

(2)COX 9/20/2008 3:02 PM

706 HOUSTON LAW REVIEW [45:3

fair market value, which is the amount they owe to the

foreclosing lender and judgment credit.

3. Investor Jones. Investor Jones owns ten single family

residential properties in an area that has suffered from declining

property values. One of her properties is located at 100 Main

Street and is in deteriorating condition.

The house at 100 Main is worth about $175,000 and is

encumbered by a mortgage loan of $200,000. The unit currently

provides Jones with $1,500 per month in rental income. 100 Main

recently became a cash drain when the adjustable rate mortgage

rose by 1%. Jones stopped paying on the loan and let it go into

foreclosure. Seven of her other properties also are unprofitable.

Jones has little net worth and few assets other than the ten

rental buildings, and seven of the ten properties are mortgaged

to at least the full amount of their fair market value.

The lender faces a choice of which procedure to use in state

A. The power of sale procedure is quicker by five months and less

costly, but the judicial foreclosure process offers the possibility of

a deficiency judgment. The lender will have to weigh the value of

a relatively small deficiency judgment against a perhaps

insolvent Jones against a more rapid acquisition of the property.

Jones will attempt to collect rent from the tenants in 100

Main while she is in possession of the property.

138

She will also

make the least possible investment in the maintenance of the

property while it is in foreclosure. In State A, Jones could be able

to obtain $21,000 or more in rental income (14 months @ $1,500

per month) if the lender selects the judicial foreclosure

procedure. Even with the power of sale process in State A, Jones