Understanding the “Whys”

Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

Grantee: University of Pennsylvania

Award Number: 2001-JN-FX-K001

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

November 2012

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

1

Preface

In 2001, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) funded a multiyear

project called “Understanding the ‘Whys’ Behind Juvenile Crime Trends.” It was designed to examine

the various explanations offered for the drop in juvenile crime during the 1990s and to assess how

useful they were in developing leading indicators of future trends. More specifically, the project had

three distinct but related goals:

1. To better understand the national downturn in most measures of juvenile crime, which, for

most types of crime, began around 1993 following a large increase during the preceding 7

years;

2. To work with local jurisdictions to incorporate valid explanations and correlates into a tool

that could be applied to data they already collect, so they could monitor leading indicators

of future turning points in their juvenile crime trends; and

3. To disseminate to the juvenile justice field both a better understanding of juvenile crime

trends and the leading-indicator tools developed with the local partners.

This effort was complemented by a series of ongoing, supplemental research projects intended to

fill gaps in knowledge that could prove important to predicting juvenile crime.

In one study, Fabio and colleagues (2006) measured age, period, and cohort effects on the

association and time lag between precursor risky behaviors (e.g., school truancy) and serious juvenile

offending. In another, Weisburd and colleagues (2009) used Seattle data to address two questions: (1)

neighborhood trajectories of violent juvenile crime (Groff et al., 2009), and (2) the concentration of

juvenile crime in locations as small as street blocks and the influence of those locations on jurisdiction-

level trends in juvenile crime (Weisburd et al., 2007). The Seattle results also will be reported in a future

OJJDP Research Bulletin.

Additional research that contributed to this book included the following: Souryal-Shriver’s review

of published research on causes and correlates of juvenile crime; analyses by Koper and Daly of trends

in community characteristics, criminal and juvenile justice practices, and juvenile crime during the

1990s in large cities and counties; Lynch and Snyder’s analysis of the interplay between juvenile drug

dealing and other forms of economic crime by juveniles; and Huizinga’s analysis of Denver data to

measure the extent to which trends in known causes and correlates of juvenile crime may explain

jurisdiction-level juvenile crime trends.

Finally, two future papers by Koper, Shelley, and Roth will report the results of attempts to forecast

juvenile crime trends in Los Angeles and Philadelphia.

The authors gratefully acknowledge OJJDP’s financial support of this work through Grant #2001-

JN-FX-K001. The findings and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not

necessarily represent the official position or policy of OJJDP. We are extremely grateful for the advice

and assistance of two OJJDP grant monitors: Barbara Allen-Hagen, who began the project; and Janet

Chiancone, who saw it through to completion. The work of the researchers named above contributed

immeasurably to the quality of the study. We are also grateful to the following individuals who served

as advisors to the project in its early stages: David Farrington, David Huizinga, John Laub, Rolf Loeber,

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

2

James Lynch, Doris McKenzie, Howard Snyder, David Weisburd, and Charles Wellford. The authors,

however, are solely responsible for all errors and omissions in this report.

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

4

Chapter 1: The Whys of the Project

By examining national trends in serious violence, one gains a better understanding of why juvenile

crime dropped so dramatically during the 1990s and remained relatively low for at least a decade.

While most would agree that the decrease actually occurred, there still are those who contend that the

drop (or its continuation) is largely an artifact of manipulation of crime statistics by some police

departments and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) (Karmen, 2000). Measuring the decrease

through multiple lenses should put this speculation to rest.

Disaggregating overall trends in serious juvenile crime informs the use of more rigorous analytical

methods for identifying and isolating factors that preceded or accompanied the drop in crime. To the

extent that the decrease was greater for some types of crime than others, greater among some

populations, or greater in some specific places, that helps narrow the range of possible explanations. If

the crime drop occurred disproportionately in large central cities, for example, then the search for

explanations could focus on those places and determine what it is about them that could have

precipitated their more pronounced decreases. Finally, the crime trends can be used to check on the

adequacy of the explanations emerging from more sophisticated analysis. Factors identified from

theory and more fine-grained analysis as the likely causes of crime drop must be shown to fit the

national crime trends during that period. That is, these factors must be shown to (1) have a likely effect

on crime; (2) be of sufficient magnitude or prevalence that changes in them could account for a

substantial portion of the drop; and (3) be distributed in the population, over time, and across places

in a manner that would account for the observed trends. The description of crime trends presented

here, then, will not only suggest where to look for explanations but also test whether the factors

identified in other analyses could have produced the decreases observed.

The intent of this project is to meet a specific need in juvenile justice policy analysis rather than

provide a comprehensive review of all scientific literature on causes of juvenile crime.

This book has five chapters, Chapters 2–5, which will be summarized in the remainder of this

chapter:

Chapter 2 establishes the groundwork for the subsequent three, using data from the National

Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) and the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) to describe Nation-

level trends in serious juvenile crime.

Chapter 3 accounts for trends in measurable conditions and processes in communities which,

combined, contribute to national trends in serious and violent juvenile delinquency.

Chapter 4 focuses primarily on the cultural processes that influence families and, in turn,

children’s involvement in delinquency. It examines both risk and protective cultural factors

related to family, school, religiosity, the legitimacy of the criminal justice system, violence in the

media, use of firearms, and gang membership.

Chapter 5 includes evaluations of the impact of various public policies and practices on

juvenile crime trends.

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

5

Overview of Chapter 2

Lynch and Snyder report that UCR arrest counts and NCVS victimization counts provide consistent

accounts of national trends in serious violent juvenile crime (i.e., homicide, rape, robbery, and

aggravated assault) between 1980 and 2000.

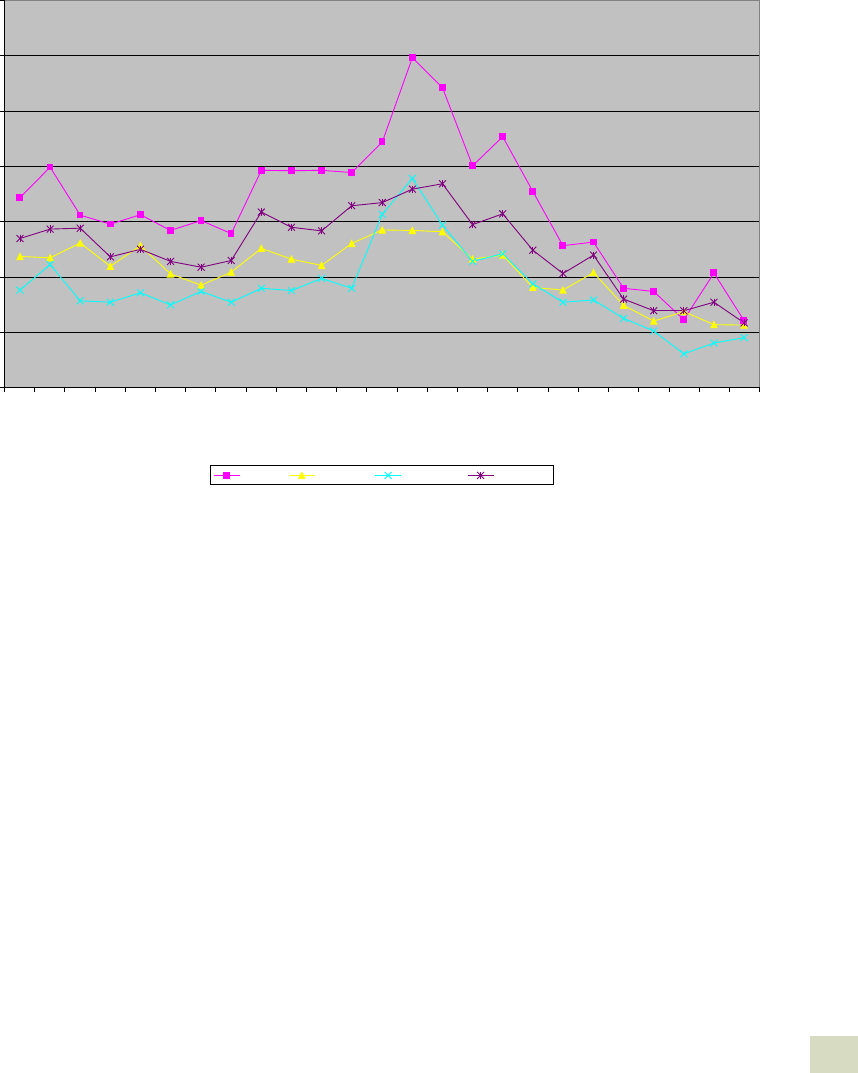

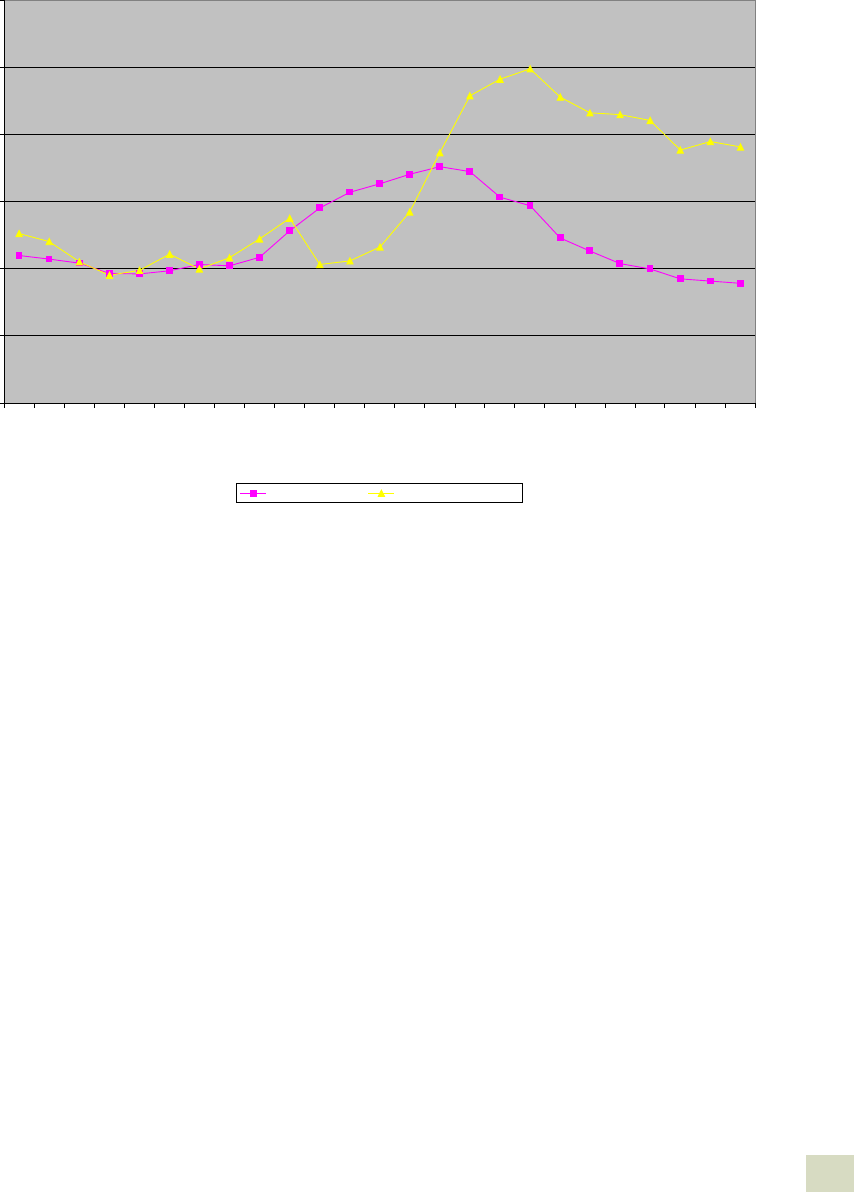

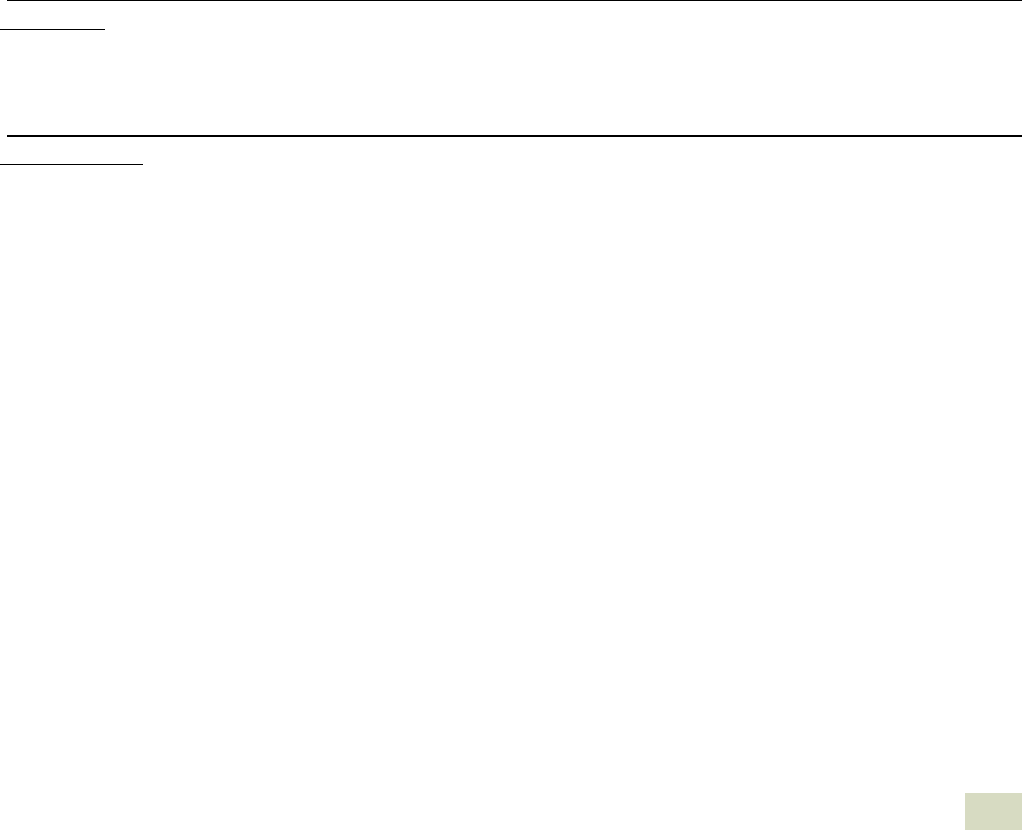

Figure 1-1. Juvenile Arrest Rate for Serious Violence, 1980–2004

Figure 1-1 displays annual UCR juvenile arrest rates for violent crimes for the period 1980–2000.

The rate hovered around 300 arrests per 100,000 juveniles from 1980 through 1987, when it began

rising steadily to a peak at about 530 in 1993. The trend reversed at that point; by 2000, the rate had

returned to about 300 arrests per 100,000, where it remained for the next several years.

0.0

100.0

200.0

300.0

400.0

500.0

600.0

700.0

800.0

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

Years

Rates per 100,000 persons age 12-17

Violent Crime Index

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

6

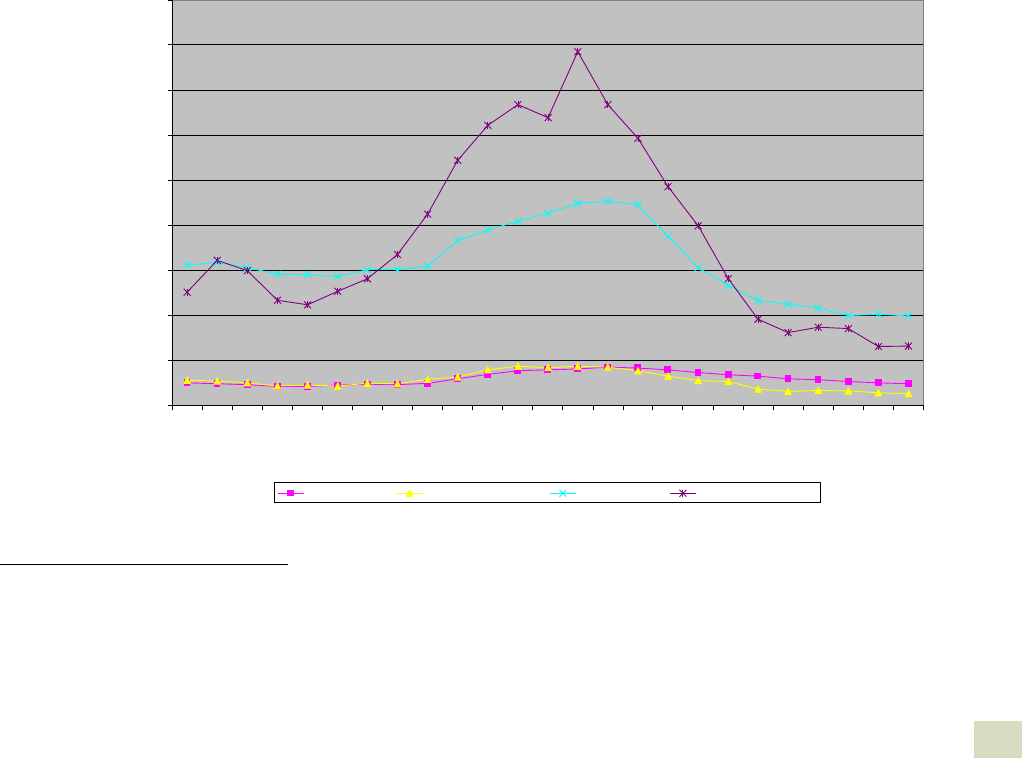

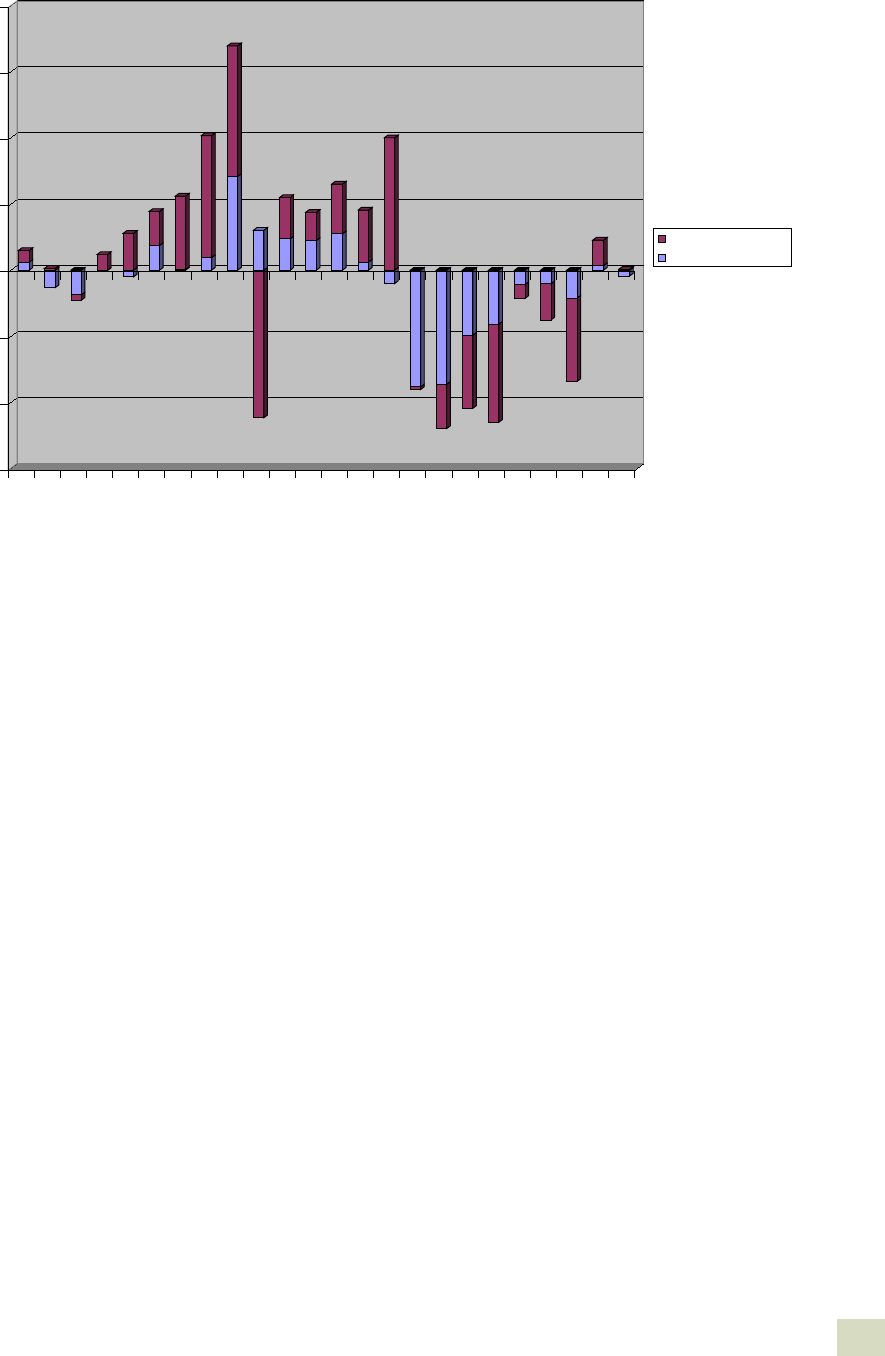

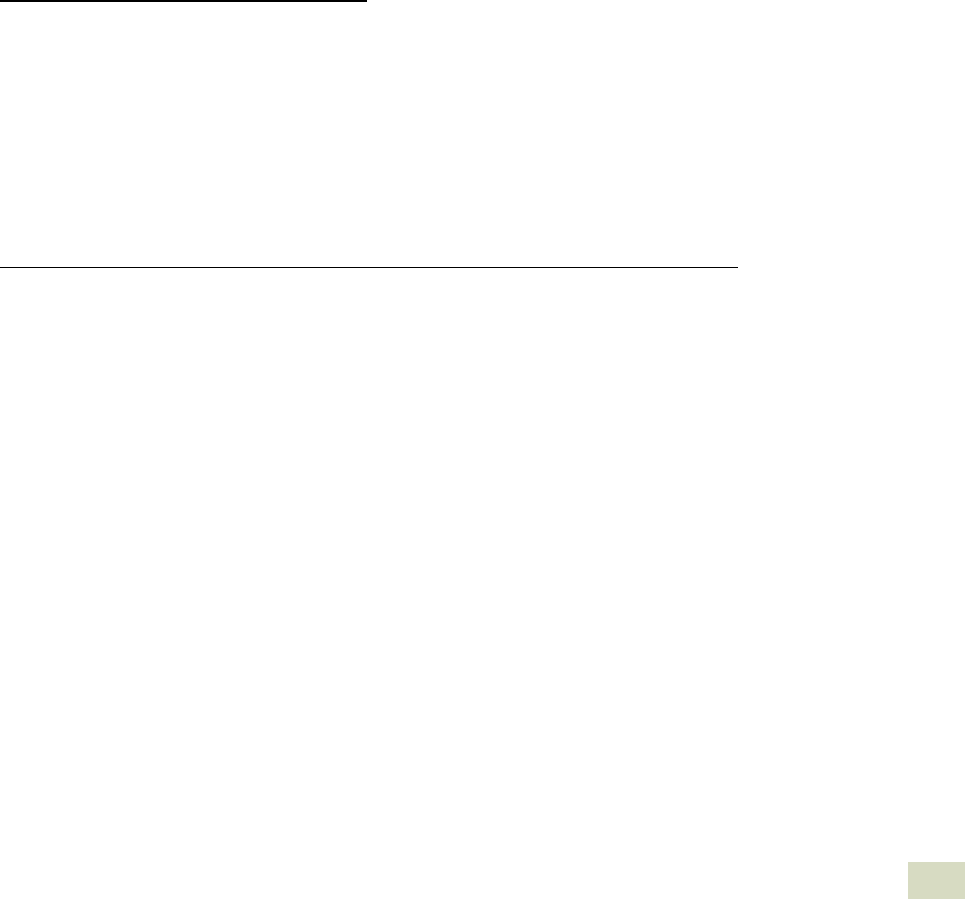

Figure 1-2. Serious Violent Offending Rates for Juveniles and Youth Adults with and

without Adult Co-offending, 1980–2004

Figure 1-2 shows that, over the same period, the NCVS rate of violent victimizations perpetrated by

at least one juvenile offender mirrored the juvenile arrest trend. In 1982, the offending rates for

juveniles and for 18- to 29-year-olds were both about 6,000 offenses per 100,000. However, by 1993,

the juvenile rate had approximately doubled to 12,000, while the young-adult rate remained just

below 6,000. At that point, both rates began falling. However, because the juvenile drop was so much

steeper, both rates were below 4,000 offenses per 100,000 by the year 2000.

When the overall trend is disaggregated by demographics and type of crime, specific patterns

emerge that serve as a starting point for understanding the increase and following decrease in serious

violent offending among juveniles. First, the trends in violent crime were more pronounced for

juvenile offenders than for adults. This was true for both the increase in crime between the mid-1980s

and 1993 and the drop in crime in the mid-1990s. This trend was similar but attenuated for young

adults, but not for older adults. This finding suggests that the factors driving the drop in crime are

significantly more pronounced in the juvenile and young-adult populations. Furthermore, the increase

in overall serious violent offending in the 1980s was not concentrated among black youth, with the

exception of homicide. However, the decrease in serious violent offending in the 1990s was greater for

black than for white youth.

Because males commit most violent crimes, it is not surprising that the male trends between 1980

and 2000 resemble the inverted U shape seen in overall trends. In contrast, violent female offending

rose throughout the entire period, doubling between 1980 and 2000. Female offending, however,

represents such a small percentage of serious and violent offending that it had little impact on

national crime trends.

The risk factors of an urban environment also figure prominently in many explanations of serious

and violent juvenile offending. For example, Blumstein and Wallace (2000) found that the 20 largest

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

Years

Rates per 100,000

<18 (1) 18-29 (1)

All <18 (2)

18-29 (2)

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

7

cities in the United States account for 80 percent of juvenile homicides. However, serious violent

juvenile offending decreased during the 1990s not only in central cities, but also in suburban and rural

areas. Therefore, the explanation for the crime drop should not be focused solely on urban

environments.

Finally, the data show that between 1980 and 2000, patterns of offending by juveniles were

changing in several ways. During the overall crime drop in the 1990s, there were especially large

decreases in group offending, juvenile co-offending with adults, use of firearms, and stranger-on-

stranger offending. And patterns in drug offending and serious violent offending among juveniles

varied significantly based upon the race of the offender. For white juveniles, increases in drug arrests

were associated with decreases in arrests for serious violent offending. In contrast, for black juveniles,

decreases in drug arrests were associated with decreases in arrests for serious violent offending. This

difference is difficult to interpret. It may suggest a deterrent effect of drug arrests on serious violent

offending for white but not for black juveniles. But it may merely reflect police patrolling patterns:

more intensive patrolling in largely black neighborhoods may increase the chances that both drug

and violent offenses are discovered and followed by arrests.

Criminologists, criminal and juvenile justice practitioners, public health professionals and others all

have attempted to explain the national juvenile crime trends described above. The following chapters

examine many of the conditions and processes they have offered from two perspectives: (1) evidence

that they affect criminal behavior, and (2) evidence that their patterns and trends from 1980 to 2000

were consistent with juvenile crime trends during the 1990s.

Overview of Chapter 3

Chapter 3 considers community- and neighborhood-level characteristics and processes that may

combine to influence national trends. Five categories are examined: (1) the proportion of the

population in demographic categories that are most at risk for offending; (2) the extent and

concentration of poverty in a community; (3) the prevalence of dysfunctional family structures; (4)

social organization and informal social control; and (5) employment opportunities.

Criminologists generally agree that age and gender are two of the most important correlates of

criminality. Rates of crime escalate and peak during adolescent years and taper off as the individual

ages (e.g., Ezell & Cohen, 2005; Farrington, 1986; Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1983; Sampson & Laub, 1992).

Male juveniles are responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime, and an obvious implication of

this is that the size of the male juvenile and young-adult populations should coincide with changes in

the aggregate crime rates. The empirical evidence on the size of the high-risk youth population,

however, yields mixed results (Donohue & Levitt, 2001; Easterlin, 1978, 1987; Hay & Evans, 2006;

Lauritsen, 2003). Further analysis of Census data and National Center for Health Statistics (2004) data

indicates that the male juvenile population declined slightly from 1980 to 1990 when serious and

violent crime was rising, and it rose slightly while serious and violent juvenile offending was declining

during the 1990s. As such, the relative changes in the size of the male juvenile population do not seem

to provide a strong explanation for the rise and fall in violent delinquency.

Of course, not all juveniles share the same level of risk for delinquency. Youth born to teen

mothers, growing up in communities with higher concentrations of poverty, and living in single-

parent households are at greater risk. Trends in some of these risk factors parallel the trends of the

time period 1980–2004, while others do not. For example, the birthrate of children born to teen

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

8

mothers declined from 1980 to 2000, trending toward older mothers and smaller families (Orlebeke,

2001). However, the national trends for families in poverty are fairly consistent with the juvenile crime

trends. Areas with high concentration of poverty have consistently higher crime rates, and

criminologists have long documented the relationship between difficult economic conditions and

crime. Poverty rates for children and families increased between 1985 and 1992 and decreased

between 1992 and 1998. This increase and decrease was greater for black families than for non-

Hispanic white families. Although these trends do not imply causation, they make clear that the two

issues are closely linked.

Another risk factor that is difficult to disentangle from poverty is family disruption. Youth living in

single-parent households are more likely to be poor than youth living in two-parent homes (Mack et

al., 2007). The empirical evidence documents both direct and indirect links between family disruption,

poverty, and delinquency (see Campbell, Hu, & Oberk, 2006; Demuth & Brown, 2004; Lauritsen, 2003).

A high prevalence of disrupted families is thought to increase delinquency both by its effects on

children and by weakening formal and informal community social controls. A low tax base in low-

income neighborhoods provides fewer resources to local law enforcement; children are more likely to

be unsupervised and more likely to associate with delinquent peers; and feelings of mutual obligation

are reduced, making residents of disorganized communities less likely to intervene in problems of

neighborhood children. Overall, the result is a reduction in community capacity to deter crime.

Trends in the number of poor, female-headed households with children were consistent with

juvenile crime trends. They both show an increase between 1985 and 1992 and then a decrease

between 1993 and 1998. Similar to the trends documented in Chapter 2, these increases and

decreases were more pronounced for black families than for whites. Employment opportunity, or the

lack thereof; routinization of the drug trade; and changes in economic opportunity in the drug

markets are three explanations offered for the crime drop. Changes in unemployment are somewhat

consistent with the crime drop; however, the relationship between unemployment and crime is

complex, especially for juveniles. Some have argued that increases in legitimate opportunity reduce

incentives for involvement in crime, reduce the burden and stress of unemployment, and strengthen

mechanisms of social control. Conversely, others argue that unemployment may contribute to a

reduction in crime by lowering the number of empty homes during the day, and may reduce the

number of potential targets by reducing the number of individuals traveling alone with valuables in

various neighborhoods at various points in the day. Furthermore, juveniles are less invested in the

labor market than their adult counterparts. The empirical evidence is mixed. Some evidence suggests

that juveniles who are employed are more likely to be delinquent than those who are not (e.g.,

Ploeger, 1997); other studies draw the opposite conclusion (e.g., Fergusson et al., 1997).

Blumstein (1995, 2006) argues that changes in the drug market and the punitive responses of the

criminal justice system influenced the rise and fall of serious violence committed by juveniles. The

expansion of the crack market involved recruiting and arming juveniles for participation in drug sales.

Juveniles were less expensive to hire, were not subject to the same consequences, and were less risk

averse than adults. Juveniles also were more vulnerable to robbery. Therefore, arming young males

who were involved in turf wars likely contributed to the escalation in violent offending during the late

1980s. However, the combination of changes in police practices, norms resulting from addiction, and

legitimate employment opportunities in the 1990s stabilized the drug markets and thus reduced the

related violence. This hypothesis seems to be consistent with the trends described in Chapter 2.

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

9

Overview of Chapter 4

Chapter 4 considers family- and individual-level conditions, which may in turn reflect cultural,

social, or biological influences. Criminologists reference multiple cultural factors—such as family

characteristics, schools, religiosity, violence in the media, use of firearms, and gang membership—in

explaining serious and violent juvenile delinquency. In the study of the influence of family factors on

delinquency, there appears to be a great deal of variation in the predictions made. First is that changes

in the demographics and the value of the familial institution influence trends in delinquency (see

Popenoe, 1993). Accordingly, the decline of family values since the 1970s should result in an upward

trend of juvenile crime. However, with the exception of changes in divorce rates, which began to

decrease when the crime drop began, this argument is inconsistent with the trends presented in

Chapter 2.

The second theoretical approach to understanding the effects of family characteristics on juvenile

delinquency is through general studies on risk and protective factors, such as the direct negative

relationship between parental monitoring and delinquency. The third explanation involves the idea

that family characteristics are multidimensional, and so the effects of different family variables should

be distinguished from one another. For example, family size and structure are related to delinquency

but are moderated by parental monitoring, family conflict, family substance abuse, and family

members’ criminal backgrounds. Family size and structure indirectly influence delinquency through

the amount of time spent with children and the quality of familial bonds (attachment). There remains

a great deal of variation in this approach, and the patterns in this category of research are not as

simple as the patterns identified in the more general risk-and-protective-factors studies.

The trend toward smaller families influences the amount and quality of time that parents can

spend with their children. While it has been documented that children increasingly have two parents

participating in the labor force, Sandberg and Hofferth (2001) found that parents reported spending

more time with their kids when the crime drop began. It is possible that working parents begin

spending more time with their children when they are not working. While there is evidence for both

the direct and indirect effects of family characteristics on delinquency, the support for direct controls

is much stronger. One limitation of these studies, however, is that many of them focus on family

structure and process during adolescence, and little has been done on how these variables affect the

developmental process in early childhood.

Schools and religious institutions are also linked to the explanations of the juvenile crime drop in

the 1990s. Schools play an important role in the lives of adolescents; they spend most of their day in

the classroom and not only learn academics but also develop (or fail to develop) important social skills.

Variables such as attendance, positive attitudes toward school, academic achievement, aspirations,

and feeling a sense of community demonstrate negative relationships with delinquency. Much of the

research on the impact of schools on delinquency revolves around social control and changes in social

bonds (see Hirschi, 1969). However, the empirical evidence on changes in the social bonds and school

dropout rates are generally inconsistent with juvenile crime trends. On the other hand, trends in

weekly religious attendance among high school seniors are consistent with the juvenile crime trends.

Furthermore, there are noticeable differences in the magnitude of the importance of religion by race.

Throughout the 1990s, black students were more than twice as likely as white students to report that

religion played an important role in their lives. Religion is thought to decrease participation in

delinquency both directly and indirectly through belief in conventional norms, disapproval of

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

10

delinquency, increased association with non-delinquent peers, and improved attachments to family

and school.

Trends of exposure to media violence also are inconsistent with the trends in juvenile crime.

Levels of violent media content did not decline during the 1990s. In fact, several scholars have

documented increases in the amount of violent content on television and in G-rated films. While

exposure to violence has been linked to aggressive and violence behavior in some people, a careful

review of the research indicates several methodological problems in many of the studies. Given the

limited empirical support for violence in the media as a causal mechanism for violence, it seems

implausible to use exposure to violent media to explain the substantial increase and decrease in

serious violent juvenile offending.

The trends in juvenile use of firearms are closely linked with gang membership, drug dealing, and

violence and parallel the crime trends in the previous two decades. There have been major changes in

arrests for possession, carrying, and use of weapons during the time period of interest here. The arrest

rate for juveniles for weapons more than doubled from the early 1980s to 1993 and then declined

sharply between 1993 and 2002. By the early 2000s juvenile homicide rates fell below the lowest point

in 1980.

There are demand- and supply-side explanations for this pattern. Blumstein argues that the

expansion and then stabilization drove juveniles’ desire to arm themselves and respond to conflict

with violence. On the supply side, changes in the production and availability of handguns are another

probable cause of the rise and fall of serious juvenile violence. Koper (2004) examined trends in

handgun production and found an increase in the production of handguns between 1987 and 1993

and a decline between 1993 and 2000. The increase in availability of handguns likely made some of

them more inexpensive, and, thus, more accessible to juveniles. However, the question of whether or

not changes in the availability of firearms to juveniles directly influence the violence level is complex.

Results from a self-report survey indicate that guns are widely available to juveniles. Therefore, it is

possible that changes in social norms, gun control laws, and punishment combined to influence or

change attitudes and behaviors regarding gun possession and use.

The trend data on the contribution of juvenile gangs to the crime trends is also somewhat unclear.

The empirical evidence demonstrates a strong and steady relationship between gang membership

and delinquency, and survey results indicate that gang members are more likely to own a gun than

non-gang members. Howell (1994) reports an increase in the number of cities citing gang problems,

and increases in gang membership and the number of gangs. The OJJDP National Youth Gang Survey

reveals a reduction in the prevalence of gangs in the 1990s (Egley & O’Donnel, 2009). These patterns

are consistent with the crime trends, especially for the greater decline in group offending than for solo

offending. However, gang data are reported by police, and they may reflect a substantial degree of

discretion in police practices in the process of identifying gang members and gang activity. While it is

difficult to draw solid conclusions, it seems plausible that fluctuations in gang membership

contributed to the crime trends described in Chapter 2.

Overview of Chapter 5

Chapter 5 considers government policies and practices that may affect crime trends either directly

(e.g., policing) or indirectly (e.g., public housing). It covers crime-control programs ranging from

prenatal care for high-risk mothers, to changes in housing policies intended to reduce the effects of

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

11

concentrated poverty, to police strategies to reduce juvenile offending. The effectiveness of programs

and policies are evaluated, followed by an examination of the breadth of the implementation and

then the consistency with the juvenile crime trends. The policies are grouped into three categories:

primary prevention, secondary prevention, and other public policies that may have an indirect effect

on the juvenile crime.

Primary Prevention Strategies

Primary prevention programs seek to reduce the harm from juvenile crime by intervening in a

broad segment of the population. Chapter 5 examines the following types of primary prevention

programs: prenatal and perinatal programs designed to improve the overall health of pregnant

women, lead abatement programs and environmental policies designed to reduce young children’s

exposure to lead, lead screening programs for at-risk youth, family intervention programs for at-risk

families, preschool interventions such as Head Start, and after-school programs such as Boys and Girls

Clubs of America.

Evidence consistently supports the link between prenatal substance abuse, low birth weight, and

increased risk for later delinquency (e.g., Day, Goldschmidt, & Thomas, 2006; Farrington, 1994; Tibbetts

& Piquero, 1999). However, aggregate trends in low birth weight and prenatal substance abuse are

inconsistent with the juvenile crime trends. Between 1970 and 1980, there was a slight decrease in live

births classified as “low birth weight” and “very low birth weight.” This decrease was followed by a

steady increase for the next two decades. Similarly, the prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS)

dropped in the 1970s and then rose between 1979 and 1993. These trends run counter to the

direction expected, assuming a 12-year time lag between birth and subsequent delinquency. This

inconsistency indicates that the proliferation of programs to improve prenatal care and substance

abuse was not a likely factor driving the crime drop of the 1990s.

Another primary prevention strategy that could plausibly be related to the juvenile crime trends is

the attempt to reduce young children’s exposure to lead, as both Federal and local policies have

aimed to do. Consistent evidence links the neurotoxic effects of young children’s exposure to lead and

increased risk for juvenile offending (e.g., Denno, 1993; Narag, Pizarro, & Gibbs, 2009; Needleman et al.,

1996). During the 1990s the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) made a series of changes to

gasoline regulations, which reduced the concentration of lead in gasoline. The policy changes reduced

exposure to lead in a way that is consistent with the juvenile crime drop; however, it seems unlikely

that the trends in gasoline lead concentration could account for the qualitative changes in violent

juvenile offending. The regulatory changes also do not explain the increase in juvenile violence in the

1980s.

Another source of exposure to lead that is more difficult to assess is lead in house paint. Interior

paint is durable and permanent. The concentration of lead in interior house paint changed

dramatically in the 1970s, dropping from about 50 percent concentration in the 1950s to a standard of

1 percent in 1971, and even further, to 0.06 percent, in 1977. It is possible that a reduction in the

concentration of lead in house paint is related to the juvenile crime trends of the 1990s, but the link

has not been closely studied.

The research on interventions for high-risk families is generally positive (e.g., Sherman et al., 1998).

But because there are no national data on the prevalence of family intervention programs, it is not

possible to formally assess the impact of these programs on the juvenile crime drop. Furthermore, the

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

12

abrupt nature of the rise and fall in juvenile violence makes the relationship between the proliferation

of family intervention programs and the juvenile crime trends unlikely.

Evidence on both preschool interventions and after-school programs is mixed and depends largely

upon the specific program, the target population, and the quality of the programming implemented.

One preschool program that could be related to the juvenile crime trends of the 1990s is Head Start, a

federally funded program for children 3 to 5 years of age. Using a 10-year lag between participation in

Head Start and involvement in juvenile delinquency, we would expect to see a decrease in enrollment

in Head Start from 1975 to 1983. Yet enrollment numbers rose from 1975 to 1989 (from 349,000 to

450,970), and they continued to increase between 1989 and 2001 (Head Start Bureau, 2002). While the

Head Start enrollment data do not correlate strongly with the juvenile crime trends, it is plausible that

the increase in Head Start enrollment had a small impact on juvenile violence during the 1990s.

After-school programs have gained popularity for many reasons—they provide structured

activities, academic programming, opportunities for community involvement, and, most importantly,

adult supervision during the after-school hours when many parents are working. From 1985 to 1997,

the percentage of two-parent families with children with both parents participating in the labor force

rose from 59 percent to 68 percent (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2009). Despite their popularity, most

evaluations of the impact of after-school programs on delinquency show mixed results. The paucity of

rigorous evaluations does not provide a great deal of theoretical support for increased after-school

programs having a strong causal impact on the juvenile crime drop of the 1990s. Despite the

questionable impact on past juvenile crime trends, local data on after-school programs may be

available in many places and could be useful in local leading indicator models to predict short-term

trends in juvenile delinquency.

Secondary Prevention Strategies

Secondary prevention strategies are programs that focus on people who already have offended

and aim to reduce the opportunities for recidivism. These programs also may attempt to prevent

crimes from occurring by intervening in situations that resemble those where crimes are likely to

occur. Secondary prevention strategies may involve interventions such as gun control, juvenile curfew,

juvenile boot camps, teen courts, transfer to adult court, and other juvenile justice interventions.

Roughly half of the largest cities in the United States had curfew laws between the late 1950s and

1980s (Ruefle & Reynolds, 1996). Juvenile curfew laws increased in popularity in the 1990s, and during

the early 1990s, 45 percent of large U.S. cities enacted new or revised curfew laws. Arrests for curfew

and loitering violations tripled between 1989 and 1998 (Ruefle & Reynolds, 1996). Although the

empirical research does not demonstrate a strong link between curfew laws and reduced juvenile

delinquency, it is possible that greater enforcement of juvenile curfew laws helped reduce serious

juvenile violence during the 1990s. It is also possible that curfew enforcement in juvenile crime “hot

spots” may be an effective tool in reducing juvenile violence, but more research linking curfew laws

and juvenile violence is necessary.

Gun control is another secondary preventive strategy that could help explain the crime drop of the

1990s. As summarized in Chapter 2, gun murders dropped from 80 percent of juvenile homicides in

1994 to 67 percent in 1999. The Federal handgun ban prohibited the sale of handguns to persons

younger than 18 years; both the Gun Free School Zone Act and the Brady Act were established in the

early 1990s. A number of states also enacted new restrictions on juvenile handgun possession and

Child Access Prevention (CAP) during the 1990s, but the research on these new laws does not show a

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

13

direct negative correlation with juvenile violence. There is some indirect evidence that the reforms of

the Federal firearms licensing system may have reduced homicides in urban areas by limiting the

number of gun dealers (Wiebe et al., 2009).

In the most prominent change in state gun control legislation in the 1990s, 22 states passed “shall

issue” laws, which require law enforcement to issue a permit to carry a concealed firearm. However,

there is insufficient evidence to determine whether these laws help or harm efforts to reduce juvenile

violence (National Research Council, 2005). Other innovative efforts to crack down on illegal handgun

possession in crime hot spots, such as the Youth Crime Gun Interdiction and Boston’s Operation

Ceasefire, were put in place during the 1990s. Boston’s Operation Ceasefire reduced youth homicide

by incorporating a zero tolerance policy and focusing criminal justice resources on violent gang

members. Most of these local-level efforts were undertaken during the late 1990s, and very little

evidence links them to the juvenile crime trends. In the future, data on gun control initiatives may be

useful in developing local leading-indicator models for juvenile crime and violence.

Growth in the private-sector security industry also may have contributed to the decline in serious

juvenile crime in the 1990s. Burglar alarms, private security guards, physical restructuring of

communities, and gated communities reduce juveniles’ opportunities to commit crimes. Evidence

indicates that situational crime prevention reduces crime at the neighborhood/street level (see Taylor,

2002). Unfortunately, little systematic data are available to assess the impact of such “target

hardening” on the juvenile crime trends of the 1990s. However, data on licensing records of private

security guards, locations of burglar alarms, and gated communities and buildings may permit

researchers to examine the impact in the local leading-indicators models.

Trends in juvenile justice policies—such as judicial waiver, prosecutorial discretion policies for

transferring juveniles to adult court, and statutory exclusion—also may have influenced the juvenile

crime trends. The juvenile justice system became more formal and more punitive in the 1990s.

Increasingly juveniles were tried as adults (from 1992 to 1997, 45 states passed laws expanding or

easing the transfer of juveniles from the juvenile justice system to the adult system) (Snyder &

Sickmund, 2006). Proponents of increasing the number of juveniles transferred to adult court argue

that the effects on juvenile crime can be threefold: (1) Serious violent offenders who are incapacitated

are not free to commit new offenses; (2) juveniles who have been incarcerated are less likely to

recidivate because of harsh punishment (specific deterrence); and (3) juvenile transfer provides general

deterrence. Empirical evidence, however, suggests that transferring juveniles to the adult system has

not had the intended effect; these juveniles were in fact more likely to reoffend than youth processed

in the juvenile justice system (see Cohn & Milan, 2010; Podkopacz & Feld, 1996; Redding, 2010).

Overall, greater use of juvenile transfer in the 1990s did not reduce violent juvenile crime; rather,

increasingly waiving juveniles to adult court may have worked to counter the crime drop.

Despite the crime drop that began after 1993, the trends in the juvenile justice system show that

there was an overall increase in the number of cases adjudicated (60.7 percent more between 1990

and 2000). This was coupled with increases in the number of juveniles held in a residential facility

before and after court disposition. Finally, this punitive trend also resulted in longer sentences being

handed down. The impact of these trends on the juvenile crime drop is not clear. Empirical research on

many of these trends is contradictory. For example, one study of formal versus informal processing of

less serious delinquents indicates that the outcomes of formal processing are generally worse than

those of juveniles handled informally (Petrosino, Turpin-Petrosino, & Guckenburg 2010). Furthermore,

evidence on sentence length indicates that longer sentences do not reduce rates of recidivism

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

14

(Wooldredge, 1988). The evidence on the links between juvenile custody and sentencing trends that

occurred in the 1990s are contradictory with the juvenile crime trends.

The evidence linking reentry services provided to juveniles with the 1990s crime drop is also

tenuous. Juvenile violence fell during the 1990s and early 2000s, despite the increasing number of

youth returning to communities after detention. Reentry services for juveniles were not widely

recognized as an important component of successful transition until the late 1990s, and Federal

legislation on reentry services was not established until 2003. However, data from tracking juvenile

reentry patterns could help practitioners anticipate future crime trends.

Another trend in juvenile justice services that could plausibly be linked to the drop in serious

juvenile violence in the 1990s was the establishment of teen courts and boot camps. Both gained

popularity in the 1990s. Teen courts are likely to involve other teens in the process of adjudication and

include letters of apology, community service obligations, and restitution as part of the sentence.

There are few rigorous evaluations of teen courts, but there is some evidence that suggests they have

reduced recidivism in target cities (see Butts et al., 2002). Data on the creation or termination of teen

courts may be helpful in developing local leading indicator models. The evidence on the effectiveness

of boot camps is less favorable, showing that they do not reduce recidivism relative to other types of

punishment. It is implausible that the proliferation of boot camps reduced juvenile violence in the

1990s.

The presence, activities, and use of resources by law enforcement may also be linked to the

reduction in serious juvenile violence during the 1990s. Levitt (2004) estimates a 14 percent increase in

the number of police per capita during that decade. Overall, the evidence on the impact of police

staffing on crime reduction is somewhat mixed, as it is difficult to distinguish the effect of the size of

the police force on crime from the impact of rising crime on the need for police. The evidence from

more recent and sophisticated research designs indicates police staffing may have played a role in

reducing serious juvenile violence. A study cited in the appendix of Chapter 5 indicates that growth in

police staffing accounted for an approximate 6 to 12 percent reduction in serious violence in the

1990s.

Police strategies for reducing violence may be as important as the numbers of officers in any given

city. Chapter 5 includes a systematic review of five types of police interventions: order maintenance

policing, community policing, problem-oriented policing, focused policing, and specific youth-related

interventions.

Order maintenance policing, generally considered aggressive policing, addresses the quality of

life and features a zero tolerance approach to all types of delinquency/crime. The theory

behind it is that a highly visible and vigilant police force will discourage more serious offending

while alleviating behaviors that are chronically problematic (e.g., disorderly conduct, drunk

driving, prostitution, enforcement of curfew violations, etc.). This type of policing became more

popular in the 1990s, but there is little systematic data on this approach. It is possible that order

maintenance policing may have reduced crime in large cities in the 1990s (see MacDonald,

2002).

Community policing emphasizes proactive policing strategies that involve cooperation and

communication at the community level. This approach may involve a range of activities, such

as foot patrol, neighborhood watch, the establishment of community substations, strategic

problem solving, and overall efforts to reduce signs of community disorder. The evaluation

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

15

results on community policing are mixed, and there is little evidence on its role in reducing

total or juvenile crime in the 1990s. One study suggested that large cities employing

community policing strategies did not have lower crime rates or larger crime drops than other

cities not using these methods (MacDonald, 2002). Another independent research project

found that agencies with stronger community policing orientation more effectively reduced

juvenile homicide (see the results of the analysis in the appendix to Chapter 5).

Problem-oriented policing includes an analysis of the problems contributing to the patterns of

crime and disorder in the community. It also may include community policing strategies, but

this approach to problem solving does not necessarily require cooperation with local residents.

Problem-oriented policing often concentrates resources on specific locations, groups, and

types of offenders. The approach was used increasingly in the 1990s, and the data linking its

effectiveness in juvenile crime trends is somewhat mixed. Some studies indicate that this type

of policing is an effective tool for crime reduction (National Research Council, 2004; Weisburd

et al. 2010); others find little evidence for crime reduction after widespread implementation of

problem-oriented policing in large U.S. cities (MacDonald, 2002). The authors suggest that the

success of this technique may be dependent upon the problem selected and the rigor with

which the solution is implemented.

Focused policing also is directed at specific places, offenders, and types of crime (e.g.,

crackdowns on drug markets, drunk driving, and elevated patrol levels around high crime

areas) and may involve order-maintenance policing, community policing, and problems-

solving initiatives as well. A recent change includes using computer record and geographic

information to map and target crime “hot spots.” The percentage of police departments

doubled from approximately 38 percent in the early 1990s to 76 percent in the early 2000s

(Johnson & Roth, 2003). It is difficult to evaluate the impact of focused policing on the juvenile

crime trends of the 1990s because COMPSTAT emerged just as crime was beginning to decline.

Another secondary prevention strategy that may have affected the juvenile crime rates is change

in state and Federal sentencing policies. Prison populations increased dramatically during the 1990s:

150 percent between 1990 and 2000. Studies on adult offending show that prison growth reduced

crime, but the impact of this overall reduction on juveniles is difficult to assess. There is little research

on how adult incapacitation specifically influences juvenile offending. Possibly, growth in the number

of incarcerated adults decreased the number of adults available to co-offend with juveniles. On the

other hand, the harsh punishment of adult offenders provided an incentive for recruiting juveniles to

participate in the drug markets (see Blumstein, 1995; 2006). Furthermore, the long-term negative

impact of incarceration on families and communities may indicate that trends in adult incarceration

may not play a significant role in reducing serious juvenile violence.

Other Policies and Programs

Finally, other public policies, such as school management, housing programs, and advances in

emergency medicine, are examined in Chapter 5. These policies are not primarily intended to prevent

juvenile crime but have indirect relevance to juvenile offending. For example, the ability of school

teachers and administrators to maintain order on and around school grounds is related to risk factors

for delinquency. The U.S. Department of Education established Safe and Drug Free Schools and

Communities, a Federal program that received $566 million in funding to reduce drugs and violence in

communities. The research on these types of programs is mixed, but evaluation data indicate that

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

16

skills training and programs that aim to reinforce behavioral norms are generally favorable. School-

based intervention programs increased in the 1990s and could have contributed to the crime drop.

Changes in the funding for public housing during the 1990s also could have indirectly influenced

the juvenile crime trends during the 1990s. In 1993, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development established a $6 billion initiative called the HOPE VI program, which gave grants to

redevelop and demolish severely distressed public housing. The program helped relocate residents

from large distressed public housing complexes in order to reduce the concentration of poverty in a

single neighborhood. HOPE VI was not implemented until the late 1990s; therefore, it seems unlikely

that it was a driving factor behind the dramatic drop in juvenile violence that began in 1994.

In addition to changes in public housing policies, innovations in the practice of emergency

medicine also could be indirectly linked to the juvenile crime trends of the 1990s. It is possible that the

proliferation of trauma centers and advancements in trauma surgery reduced the number of

aggravated assaults that resulted in death. These factors may help explain why the decrease in

juvenile homicide was larger than the decrease for other types of violent offending, but it would not

account for broader qualitative changes in juvenile violence that occurred during this period.

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

17

Chapter 2. Juvenile Crime Trends and Their Implications for

Understanding

(James P. Lynch, John Jay College, New York, NY, and Howard N. Snyder, National Center for Juvenile

Justice, Pittsburgh, PA)

Introduction

Nation-level trends in serious violence are the point at which the search begins to understand why

juvenile crime (and crime generally) has dropped so dramatically in the past decade. Describing the

decrease in juvenile violence through a variety of lenses can demonstrate that the drop has indeed

occurred. While most would agree that crime has decreased in the past decade, there still are those

who contend that the drop (or its continuation) is largely an artifact of crime statistics and, more

specifically, the manipulation of those statistics by the police and the Federal Bureau of Investigation

(FBI) (Karmen, 2000). This speculation should be put to rest.

By describing these violence trends, we also will inform the use of more rigorous analytical

methods for identifying and isolating the factors that preceded or accompanied the drop in crime. To

the extent that the decrease occurs in some types of crime, among some populations or in specific

places, this will narrow the range of possible explanations. If the crime drop occurred

disproportionately in large central cities, for example, then the search for explanations can focus on

those places and determine what it is about them that could have precipitated this more dramatic

decrease in juvenile crime.

Finally, the crime trends can be used to check on the adequacy of the explanations that emerge

from more sophisticated analysis. Factors identified from theory and more fine-grained analysis as the

likely causes of the juvenile crime drop must be shown to fit the national crime trends during that

period. That is, these factors must be shown (1) to have a negative effect on crime, (2) to be of the

magnitude or prevalence that changes in them could account for a substantial portion of the drop,

and (3) to be distributed in the population and across places in a manner that would account for these

trends. The simple description of crime trends presented here, then, will both suggest where to look

for explanations and confirm that the factors identified in other analyses could have produced the

decreases observed.

Crime Statistics and Crime Trends

Describing Nation-level trends in juvenile violence, like describing unemployment and other

indicators of social well-being, is dependent on national statistical systems. These systems routinely

and systematically assess the level of crime and the change in level over time. We are fortunate to

have reasonably good statistical systems for assessing these nationally in the United States. One of

these indicators is the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) conducted by the Census Bureau

under the auspices of the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). The other is the Uniform Crime Reports

(UCR) compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

1

These two systems employ very different

methodologies for collecting information on crime. The NCVS is a household survey in which a

1

The FBI is implementing the National Incident Based Reporting System (NIBRS) that will provide incident-level data on crimes reported

to the police. At present, this data system does not operate in enough jurisdictions to generate national estimates.

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

18

representative sample of residents of the United States is asked to report on criminal victimization. The

UCR is an administrative series in which police departments report to the FBI the offenses that come to

their attention and the arrests they make pursuant to those crimes. Using this information, the FBI

produces national estimates of reported crime.

2

These two overlapping but quite different series

provide a complementary picture of the crime problem (Lynch & Addington, 2006). The NCVS includes

crimes that the UCR omits by design or because they did not come to police attention. The FBI

includes crimes such as homicide that are not in the survey. Moreover, the kinds of distortions that

affect the NCVS are very different from those that affect the UCR. This is useful in that the two series

are unlikely to be affected by the same distortions or measurement errors and it is less likely that the

same measurement errors could drive both series down in the same period. Thus, if the two series are

showing a similar drop in crime, it is unlikely that the drop is due to measurement error or to the

conscious manipulation of these statistics.

3

The NCVS and the UCR are complementary in other ways (Biderman & Lynch, 1991; Lynch &

Addington, 2006). The UCR is an aggregate reporting system that collects jurisdiction-level counts of

crime for the vast majority of places in the United States. The NCVS collects data on only a sample of

the U.S. population, but it includes very detailed information on each crime event reported in the

survey. As a result, the UCR has greater coverage and a greater ability to provide estimates on

subnational units than the NCVS. But the NCVS can provide very detailed and disaggregated

information on the nature of crime and subgroups of the population. This permits the disaggregation

of crime rates into those for different demographic groups, regional groups, and more. Used together,

these social indicators can provide a more informative and differentiated description of the drop in

juvenile crime than either could do alone.

Generating Juvenile Crime and Offending Trends

This book focuses on trends in juvenile offending and, specifically, serious violent crime committed

by juveniles—i.e., homicide, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault. Information on juvenile offending

is typically found in the UCR arrest data on Age, Sex, Race, and Ethnic Origin (ASREO) and in the

Supplementary Homicide Reports (SHR). It is more unusual to use data on offenders provided by

victims in the NCVS to describe trends in juvenile offending, as the survey is typically used to generate

trends in victimization and not offending (Lynch, 2002). Using all of these data sources complicates

the analysis because they are all different and their differences must be taken into account in

comparing levels of crime and the trends and interpreting the differences and similarities between the

trends. Much of our current understanding of trends in juvenile crime comes from UCR’s ASREO report.

These data are jurisdiction-level counts of persons arrested grouped by the most serious offense for

which they were arrested

4

. Separate counts are provided by the age, race, and gender of the arrestee.

These data are useful for describing gross trends in specific crimes but are of limited use in

disaggregating the attributes of these crimes. Another important consideration in using arrest data is

that they reflect a conjunction of offender and police behavior. Therefore, there are potential biases

2

The term estimate refers to a set of procedures followed to produce counts and rates of crime with the UCR data. Different procedures

would yield different counts and rates.

3

The strategy of using different and complementary social indicators is not unique to the justice area. National unemployment trends,

for example, also are estimated by survey-based indicators from the Current Population Survey (CPS) and an administrative series of

claims for unemployment compensation.

4

When more than one crime is committed in an event, the UCR employs a hierarchy rule in which some crimes are given priority over

others in determining how the event should be classified (FBI, 1984).

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

19

due to both patrolling practices and police discretion in making an arrest. These biases no doubt affect

measured levels and patterns of juvenile crime. Fortunately for our purposes, if these practices remain

roughly consistent in each jurisdiction over the observation period, practice biases will affect

measures of relative trends less than measures of trends. Moreover, it seems likely that practices have

a larger effect on minor disorder crimes than on serious violent crimes, for which police officers have

less room for discretion in the arrest decision. Finally, the findings reported later in this chapter

demonstrate similar relative trends for ASREO and NCVS measures. This suggests that practice bias

was either small or fairly constant during the observation period.

For these reasons, many of the most influential analyses of crime trends employ data from the SHR

(Blumstein & Wallman, 2000). This component of the UCR provides detailed information on homicides

reported to the police. This information includes the age, race, and sex of the victim; the age, race, and

sex of the offender (if known); the relationship between the victim and offender; the circumstances of

the crime; whether a weapon was used and the type of weapon; and the jurisdiction in which the

crime occurred. Because the SHR data are collected on an incident basis and not aggregated to

jurisdiction counts, like the arrest data, they can be disaggregated by many of these characteristics

and thereby offer additional insight into why increases or decreases in homicides may have occurred.

One of the limitations of relying extensively on the SHR to understand juvenile crime trends is that

homicide is relatively rare and quite different from other types of crime and even other serious

violence. The factors driving homicide trends may be very different from those affecting robbery or

assaults, two serious violent crimes for which the NCVS is particularly helpful. The survey provides

reasonably detailed information on each crime event respondents report, including some information

on the offenders. Specifically, respondents are asked about the apparent age, race, and gender of the

offenders; how many there were; whether they appeared to be gang members; and the relationship

between the offender and victim. The survey also collects information on the crime event that can be

of use in understanding the social context of offending. So, for example, one can know the type of

place where the crime occurred, the time of day, the type of weaponry used, the type of injury

sustained, and much more. In this book we use both the UCR and the NCVS to describe general trends

in juvenile offending and disaggregate these trends by the demographic characteristics of the

offender (and victim) as well as the characteristics of the event. Using the NCVS in this way permits the

disaggregation of trends for a broader range of violence than does the SHR, which includes homicide

only.

Because the NCVS was not designed specifically to generate annual estimates of offending, some

accommodations must be made in computing offending rates. Estimating the juvenile offender rate

with the NCVS requires taking all serious violent offenses (homicide excluded) in which the victim

reports that a juvenile was involved and multiplying these events by the number of juvenile offenders

participating in the crime. This juvenile offending count is divided by the NCVS estimates of the

number of juveniles aged 12 to 17 in the population.

Some crimes are committed by groups, including both juveniles and adults, and the survey does

not obtain the age of each individual in these offending groups because that would be burdensome

for the respondent. Instead, interviewers ask the respondent to report the age of the oldest and

youngest members of the offender group. This makes it possible to compute high and low estimates

of juvenile offending by assuming first that all in the mixed group were juveniles and then that all

group members were adults. Throughout this book, both high and low estimates of violent offending

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

20

trends will be reported when NCVS data are used. A more detailed description of the methods used to

make these estimates can be found in Appendix A.

Computing the juvenile arrest rates with UCR data is more straightforward. They were computed

by dividing the reported counts of arrests of persons ages 10 to 17 for violence by estimates of the

population of persons 12 to 17 in the reporting jurisdiction. The UCR presents arrest counts grouped

by the age of the arrestees. For the juvenile years, these groups are “under 10,” “10 to 12,” “13 to 14,”

“15,” “16,” and “17.” The juvenile population linked to the NCVS data covers the ages of the

respondents (i.e., 12 through 17). The authors wanted to keep the population bases consistent

throughout this chapter. Therefore the arrest rates used the population base of 12 through 17. Given

the UCR age groupings in the arrest counts, it was impossible to have the age-range of the arrest

counts parallel the NCVS population range. Consequently, the juvenile arrest rates used different age

ranges for their arrest counts (10 to 17) and population counts (12 to 17). Because relatively few

persons ages 10 or 11 are arrested, including these events in the numerator but not the denominator

will result in a slight overestimate of the juvenile arrest rate for violence. However, this is preferred to

the confusion resulting from including the age-group 10–11 in the denominator of one series but not

the other.

This book also takes a unique approach to describing the trends generated from the available

national crime statistics. Typically the discussion of trends focuses on the percent change in rates.

These changes indicate the magnitude of the increase or decrease in crime over a specified period as a

percentage of the initial rate. Big percentage changes in rates in one series or one subpopulation and

not another would suggest that something different may be going on in the subgroups that could

point to factors that explain the changes in crime. In addition to this customary approach to

describing and assessing the difference between trends, we also will examine the proportion of the

change in the counts of crime attributable to a specific population. This is as important as the rate

comparisons because a small change in rates in a large population can account for more of the drop in

crime than a large change in a small population. Native American arrest rates, for example, could

change a great deal, and this would deserve explanation. The Native American population is so small,

however, that this change in rates will have little effect on the overall crime rate. On the other hand, a

small change in rates in a large population can account for a great deal of the change in crime and

should be examined. This less customary approach to assessing trends is particularly appropriate for

explaining the drop in juvenile violence rather than the testing of theories, which is the usual purpose

for examining crime trends. A large change on a small base is interesting for the purpose of testing

theory but may not be very important in explaining the drop in offending. However, both of these

perspectives are useful in the search for factors than can explain the change in juvenile crime.

Trends in Serious Violence by Juveniles, 1980–2004

The juvenile arrest rate reported by the UCR for serious violence—i.e., homicide, rape, robbery, and

aggravated assault—decreased from about 439 per 100,000 population 12 to 17 in 1980 to about 386

per 100,000 in 1984, when it began to increase steadily, reaching a high of 704 per 100,000 in 1994

(Figure 2-1). At that point the rates dropped sharply, falling to 357 per 100,000 by 2004. The rate of

decline was greatest in the mid-1990s, slowing after 1998 and remaining essentially unchanged in

2003 and 2004.

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

21

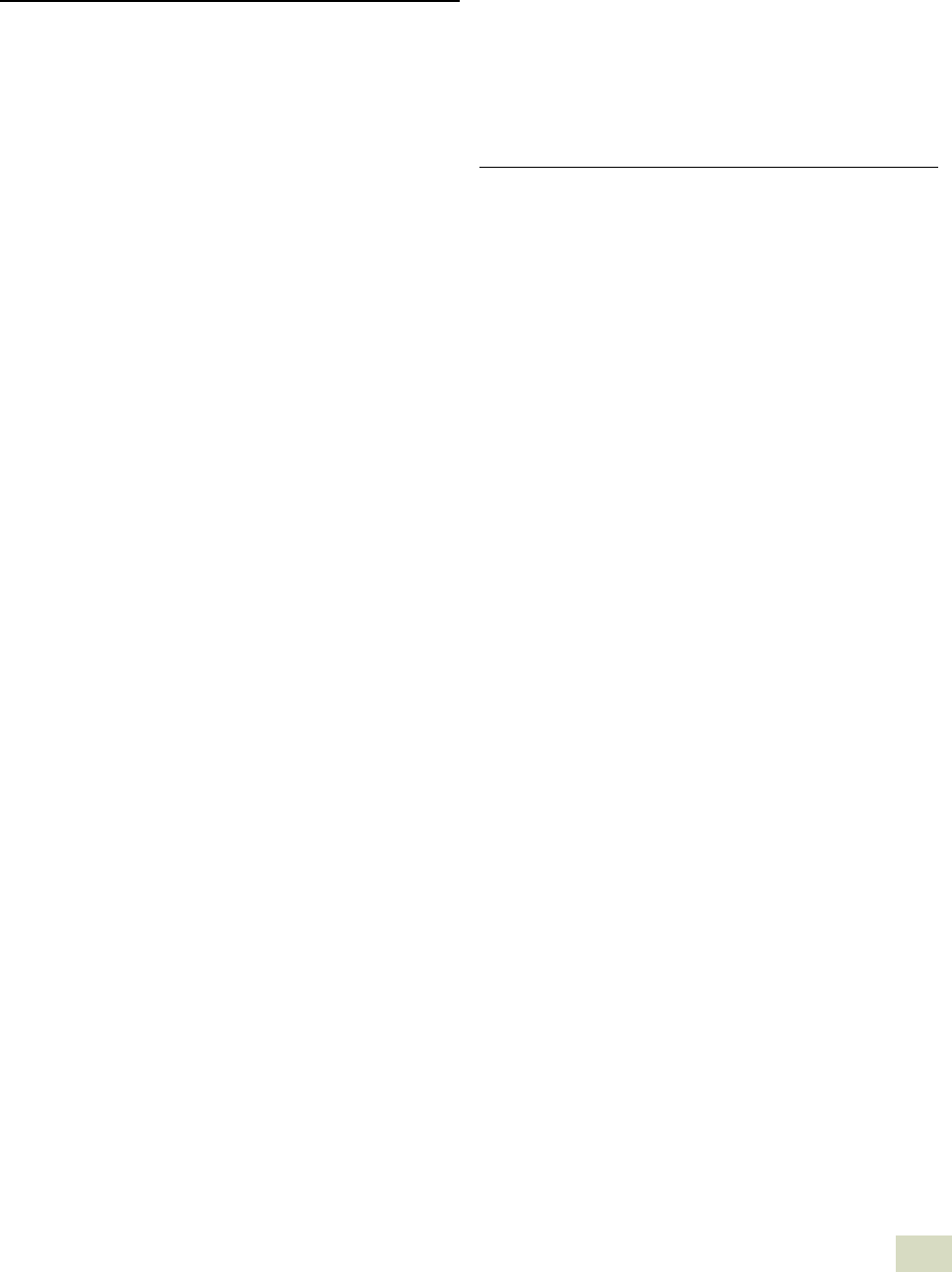

Figure 2-1. Juvenile Arrest Rates for Serious Violence, 1980–2004

The NCVS estimate of the juvenile offending rate for serious violence shows a similar but more

volatile trend. This rate declined from a high of 7,980 (i.e., 7,980 offenses per 100,000 persons ages 12

to 17) in 1981 to approximately 5,578 in 1987, and then rose to a high of 11,938 in 1993 only to fall to

2,427 in 2004. These rates include all instances of juvenile co-offending with adults as juvenile

offending. When co-offending with adults is removed from these juvenile rates, the general pattern

remains the same (Figure 2-2). The rate of serious juvenile offending went from 4,449 in 1981 to 3089

in 1987, then increased steadily to 7,576 in 1993 and decreased to 1,807 by 2004.

0.0

100.0

200.0

300.0

400.0

500.0

600.0

700.0

800.0

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

Years

Rates per 100,000 persons age 12-17

Violent Crime Index

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

22

Figure 2-2. Juvenile Offending Rates with and without Adult Co-offending, 1980–2004

The level of juvenile offending from the NCVS is much higher than that for the juvenile arrest rate

from the UCR. This is to be expected because, among other things, a large proportion of juvenile

offending is not reported to the police, and some of that reported is not recorded (Hart & Rennison,

2003). Even for the crimes that are reported and recorded by the police, relatively few are cleared by

arrest. In those crimes for which an arrest is made, only one person may be arrested when the victim

reported multiple offenders. For these reasons, the estimates of the level of juvenile offending from

the NCVS and the UCR ASREO data will be quite different. The trends, however, are broadly similar in

both series. Juvenile offending, like the juvenile arrest rates, increased from the mid-1980s until the

mid-1990s when it began to drop precipitously.

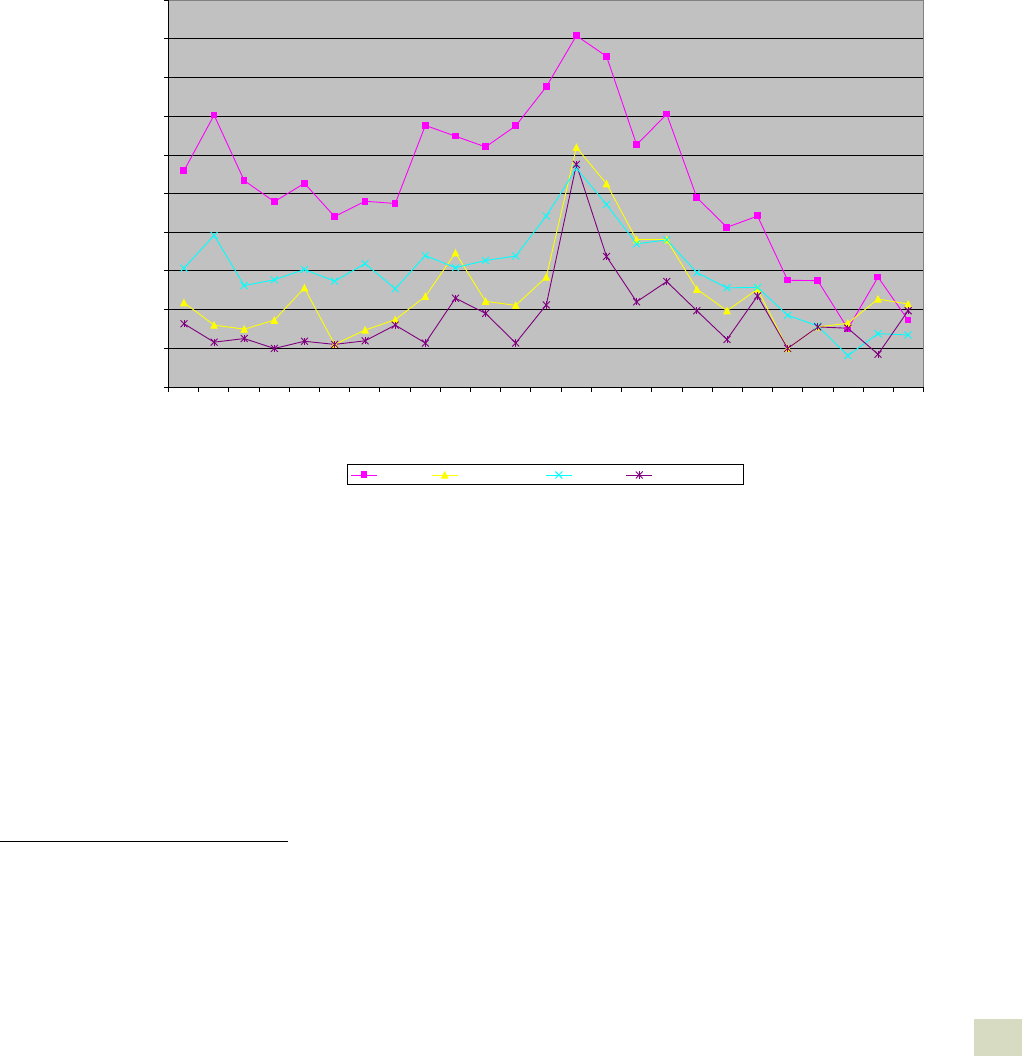

The trends in juvenile arrests differ somewhat across types of violent crime (Figure 2-3). The rise

and the fall for homicide are steeper than they are for other types of violent juvenile offending. The

juvenile arrest rate for homicide increased from 7.0 (i.e., 7.0 arrests of persons ages 10 to 17 for every

100,000 person ages 12 to 17) in 1984 to 19.5 in 1993, or 179 percent. This rate then decreased from

19.5 in 1993 to 4.3 in 2004, or 78 percent. Juvenile arrests for homicide were substantially lower in

2004 than they were in 1984.

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

Years

Rate per 100,000 persons 12-17

Any<18

All<18

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

23

Figure 2-3. Juvenile Arrest Rates by Type of Crime, 1980–2004

Homicide, however, is relatively rare compared with other forms of serious violence, and homicide

trends do not account for much of the increase and decrease in serious violence. When crime rates

were at their highest, in 1993, the juvenile arrest rate for homicide was 19.5 per 100,000, while the

overall rate of juvenile arrests for serious violence was 704 per 100,000. Juvenile arrests for homicide

accounted for about 3 percent of juvenile arrests for serious violence in 1993. Even though homicides

increased more and declined more over the period examined, homicide per se does not account for

much of the increase or the decline in serious juvenile violence. However, to the extent that the factors

driving the change in homicide rates are similar to those driving the bulk of serious juvenile violence,

examining homicide can shed some light on the decline in serious violent crime committed by

juveniles. More information on the similarities in homicide trends compared to other forms of serious

violence is presented below.

The trends in juvenile robbery arrests show steep increases in the late 1980s, although they were

not as large as those for homicide. Robbery rates rose by 70 percent, from a low of 156 per 100,000 in

1987 to a high of 266 per 100,000 in 1994, when they declined 62 percent, reaching a low of 101 per

100,000 in 2004. Like homicide, robbery by juveniles was substantially lower in 2004 than it was at any

time in the 1980s. Aggravated assault arrests showed similar increases during the period, while

forcible rape increased more slowly. Aggravated assault rose 127 percent from a low of 173 in 1983 to

a high of 393 in 1994. The decrease in aggravated assault was less dramatic than that for robbery,

declining only 40 percent from the high in 1994 to a rate of 236 per 100,000 in 2004. Aggravated

assault by juveniles was higher in 2004 than it was at its lowest point in the 1980s. In the 1990s,

robbery arrests decreased as rapidly as homicide, while both aggravated assault and forcible rape

arrest rates declined more slowly. After 2000, the rates of juvenile arrests for homicide and robbery

remained essentially stable, while the juvenile arrest rates for forcible rape and aggravated assault

continued to decline through 2004. These differences in the trends suggest that different processes

0.0

100.0

200.0

300.0

400.0

500.0

600.0

700.0

800.0

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

Years

Arrests per 100,000 Persons 12-17

Violence Index Homicide X 25 Rape X 10 Robbery Aggravated Assault

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

24

may be driving the decrease in homicide and robbery than are influencing rape and aggravated

assault.

These trends for specific types of violent crime are consistent with a number of explanations that

have been advanced for the crime drop. One of the explanations attributes the increase in crime to the

onset of the “crack epidemic” and the diffusion of violence into communities, while the decline is

attributed to a reversal of that process through a variety of mechanisms, including intensive policing

of disorder in public places (Blumstein & Wallman, 2000). The steep rise of homicide, robbery, and

aggravated assault in the 1980s is consistent with this explanation. Turf wars brought killings and

near-killings on the part of drug dealers and robberies on the part of those looking to buy crack.

Forcible rape was not as deeply affected by these factors and rose more slowly. The steep declines in

homicide and robbery in the 1990s are consistent with the reversal of the “crack epidemic,” but the

slower decline in aggravated assault in this period is not. Rosenfeld (2006) suggests that over this

period, the police were increasingly more inclined to treat domestic violence as aggravated assaults as

opposed to lesser offenses, so that intra-familial assault counts increased at the same time the assaults

attendant to the drug trade were decreasing. The result is the more modest decrease in the juvenile

aggravated assault trends observed here. This explanation will become more plausible if further

disaggregations of the data indicate that crimes among intimates became an increasingly larger

component of serious juvenile violence throughout the 1990s.

Trends in Serious Violent Crime by Characteristics of Offenders

Age of Offender. Although the rate of serious violent crime for the entire population increased and

decreased in the period 1980 to 2004, the increase and decrease in rates were greater for juveniles

than for older groups. The juvenile arrest rate for serious violence rose 83 percent from 1984 to 1994,

while this rate for persons 18 to 64 fell only 38 percent. From 1994 to 2004, the juvenile arrest rate for

serious violence fell 49 percent and the adult rate fell 34 percent. Again, the differences across age-

groups for homicide were more pronounced than they were for serious violence more generally. While

the juvenile arrest rate for homicide increased 179 percent between 1984 and 1993, the adult rate

increased only 20 percent from its low in 1985 to its high in 1991. The juvenile arrest rates for serious

violence declined 78 percent from 1994 to 2004, and the decrease in the adult arrest rate was 62

percent from its high of 14.1 per 100,000 persons ages 18 to 64 in 1991 to the low of 6.6 in 2004.

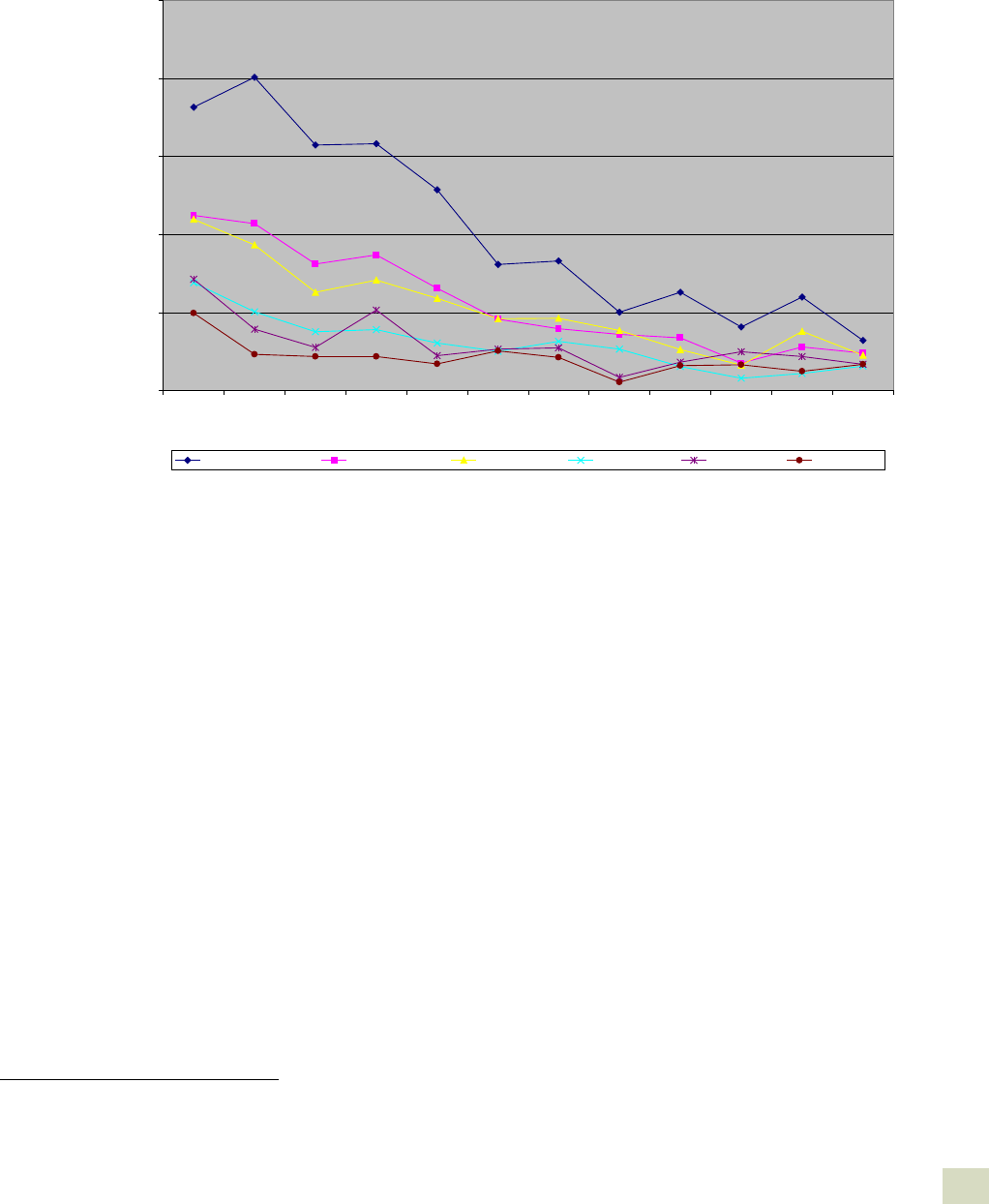

The decline in juvenile crime seems to have occurred in phases, with the decline from 1993 to 1998

or 2000 looking somewhat different from the decline after 2000 (Figure 2-4). The early phase was

concentrated among juveniles in the crimes of homicide, robbery, and aggravated assault. The later

phase of the decline affected adults more and involved aggravated assault and rape.

Most of the decrease in homicide and robbery occurred between 1994 and 2000 for both adults

and juveniles (Figure 2-5). The rate of homicides by juveniles decreased by 67 percent from 1994 to

2000, and by 77 percent from 1994 to 2004. For adults, the comparable figures were 42 percent and 45

percent. For robbery, juvenile arrest rates declined 56 percent from 1994 to 2000 and 59 percent from

1994 to 2004. The corresponding figures for adult robbery arrests were 42 percent and 38 percent.

More of the decrease in aggravated assault and rape occurred after 2000 for both juveniles and adults.

Juvenile forcible rape arrest rates declined by 27 percent from 1994 to 2000 and by 39 percent by

2004, and the corresponding figures for aggravated assault were 28 and 38 percent. The adult rape

Understanding the “Whys” Behind Juvenile Crime Trends

25

arrest rate declined 29 percent by 2000 and 40 percent by 2004, and the adult aggravated assault

arrest rate declined by 21 percent by 2000 and 31 percent by 2004.

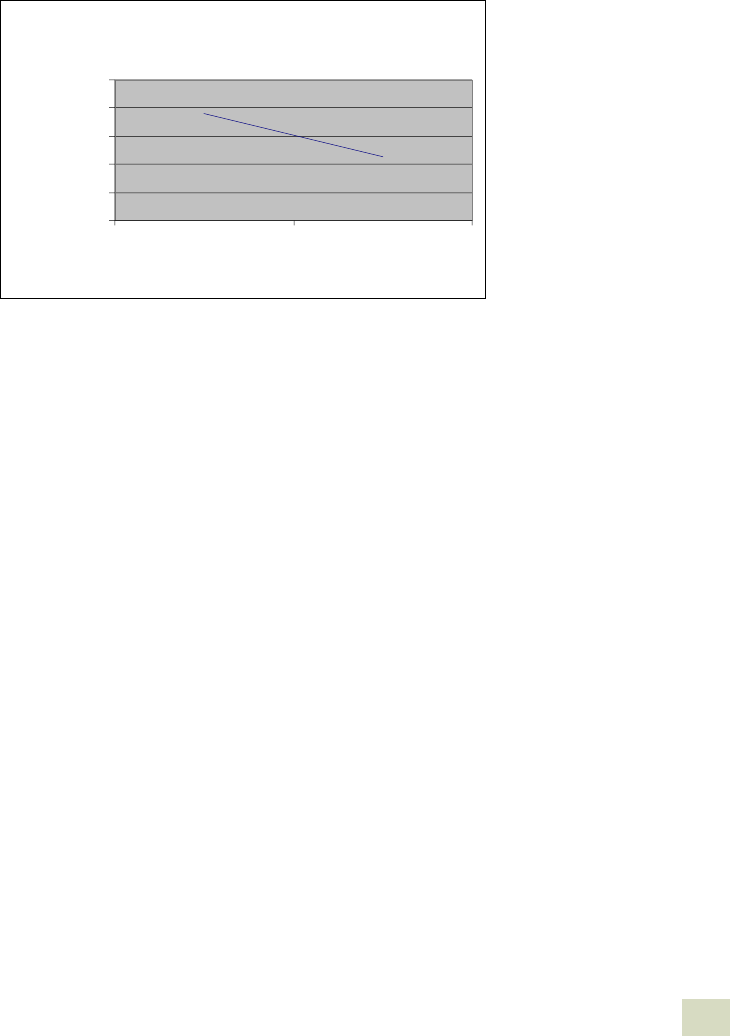

Figure 2-4. Ratio of the Percent Decline 1994–2004 to the Percent Decline 1994–2000 by Type of Crime

for Juveniles and Adults