Melissa Kearney, Benjamin Harris, Elisa Jácome, and Lucie Parker

POLICY MEMO | DECEMBER 2013

A Dozen Facts about America’s

Struggling Lower-Middle Class

WWW.HAMILTONPROJECT.ORG

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Hamilton Project is grateful to Karen Anderson, Stacy Dean,

David Dreyer, Robert Greenstein, Meeghan Prunty, and Dorothy

Rosenbaum for innumerable insightful comments and discussions.

It is also grateful to William Dyess, Laura Howell, Andrew Kim,

Jeremy Patashnik, Joseph Sullivan, and Lindsey Underwood.

MISSION STATEMENT

The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise of

opportunity, prosperity, and growth.

We believe that today’s increasingly competitive global economy

demands public policy ideas commensurate with the challenges

of the 21st Century. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a

judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by fostering

economic growth and broad participation in that growth, by

enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role

for effective government in making needed public investments.

Our strategy calls for combining public investment, a secure social

safety net, and fiscal discipline. In that framework, the Project

puts forward innovative proposals from leading economic thinkers

— based on credible evidence and experience, not ideology or

doctrine — to introduce new and effective policy options into the

national debate.

The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s

first Treasury Secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern

American economy. Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy,

believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would

drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent

aids and encouragements on the part of government” are

necessary to enhance and guide market forces. The guiding

principles of the Project remain consistent with these views.

A Dozen Facts about America’s

Struggling Lower-Middle Class

Introduction

Many American families whose incomes are not low enough to ocially place them in poverty

live in economically precarious situations. is struggling lower-middle class consists of the 30 percent of

working-age families with children who have incomes between 100 and 250 percent of the federal poverty

level (FPL), or between roughly $15,000 and $60,000, depending on family composition. ough not ocially

poor, these individuals and families experience limited economic security. One major setback could thrust

them into economic chaos.

e struggling lower-middle class encompasses low- and middle-skilled workers whose wages have stagnated

in recent decades (Autor, Katz, and Kearney 2008). More than half of these families are headed by married

couples, and of these families, roughly half rely on two earners to make ends meet. While lower-middle-

class families face many challenges, this policy paper focuses on two pointed struggles—food insecurity and

low returns to work due to the design of tax and transfer programs.

Compared to families ocially living in poverty, these struggling lower-middle-class families have

substantially dierent characteristics: they have higher rates of marriage, more dual-earning spouses, and

higher levels of educational attainment, yet they face some of the same challenges faced by families living

in poverty. For example, these households are oen unable to meet the most basic requirement of obtaining

a sucient diet. In 2012 more than 24 percent of struggling lower-middle-class children ages twelve to

seventeen (or approximately 1.7 million children) lived in a household identied as being food insecure.

Many of these families also rely on government programs for income support. In 2012 approximately one in

three struggling lower-middle-class families (approximately 3.7 million families) relied on at least one major

federal government transfer program. In fact, more than 20 percent of families (approximately 2.4 million

families) relied on food stamps in that year alone.

An array of tax and transfer programs—including food stamps, Medicaid, and the Earned Income Tax

Credit (EITC)—strengthen the resources available to struggling lower-middle-class families and provide

Melissa Kearney, Benjamin Harris, Elisa Jácome, and Lucie Parker

framework to consider what policies would be appropriate for

strengthening their economic security and well-being.

ese facts focus on those who are above the federal poverty

level, and yet are still quite economically insecure, relying

on government transfers, facing high levels of anxiety about

being able to feed their families, and facing extremely high

marginal tax rates as they try to work themselves securely

away from poverty.

Chapter 1 describes the group we dene as made up of

struggling lower-middle-class families. Chapter 2 focuses on

the challenge of food insecurity and provides information

about the nation’s most-important and wide-reaching

government program focused to address this issue, the

Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP).

Chapter 3 presents evidence about the relevant set of tax and

transfer programs facing the struggling lower-middle class,

highlighting how this panoply of programs can inadvertently

make the climb into middle-class security more dicult.

Introduction continued from page 1

a safety net for families in need. Income-support programs

undoubtedly improve the economic well-being of families

on the cusp of poverty, but they oen come with unintended

consequences. One major problem, highlighted in this paper,

is the implicit tax on families who receive reduced benets as a

result of higher earnings. Transfer-program benets phase out

as family earnings rise, which reduces the return to work and

makes it dicult for these families to work their way rmly

into a better economic life.

A founding principle of e Hamilton Project’s economic

strategy is that long-term prosperity is best achieved by

fostering economic growth and broad participation in that

growth. is principle calls for economic security among

a thriving and prosperous middle class, which has been a

long-celebrated feature of our nation’s social and economic

fabric. In this spirit, we oer “A Dozen Facts about America’s

Struggling Lower-Middle Class” to bring attention to who

these families are, to highlight two particular challenges

facing this broad group of American society, and to set up a

CHAPTER 1: A Snapshot of Struggling

Lower-Middle-Class Families

Many families in America’s struggling lower-middle class—dened to include those with income

between 100 and 250 percent of the federal poverty level, or between roughly $15,000 and $60,000,

depending on family size and composition—live in economically precarious situations. ough not

ocially poor, these families experience limited economic security; one major setback in income

could push them into poverty.

1. More than half of families in the United States earn $60,000 or less

per year.

2. Nearly half of families in the United States live below 250 percent of

the federal poverty level.

3. Struggling lower-middle-class families are almost equally headed by

single parents and married couples.

4. Nearly one out of two families in the struggling lower-middle class is

headed by an adult who has attended college.

5. Nearly one-third of struggling lower-middle-class families rely on

income support from a government program.

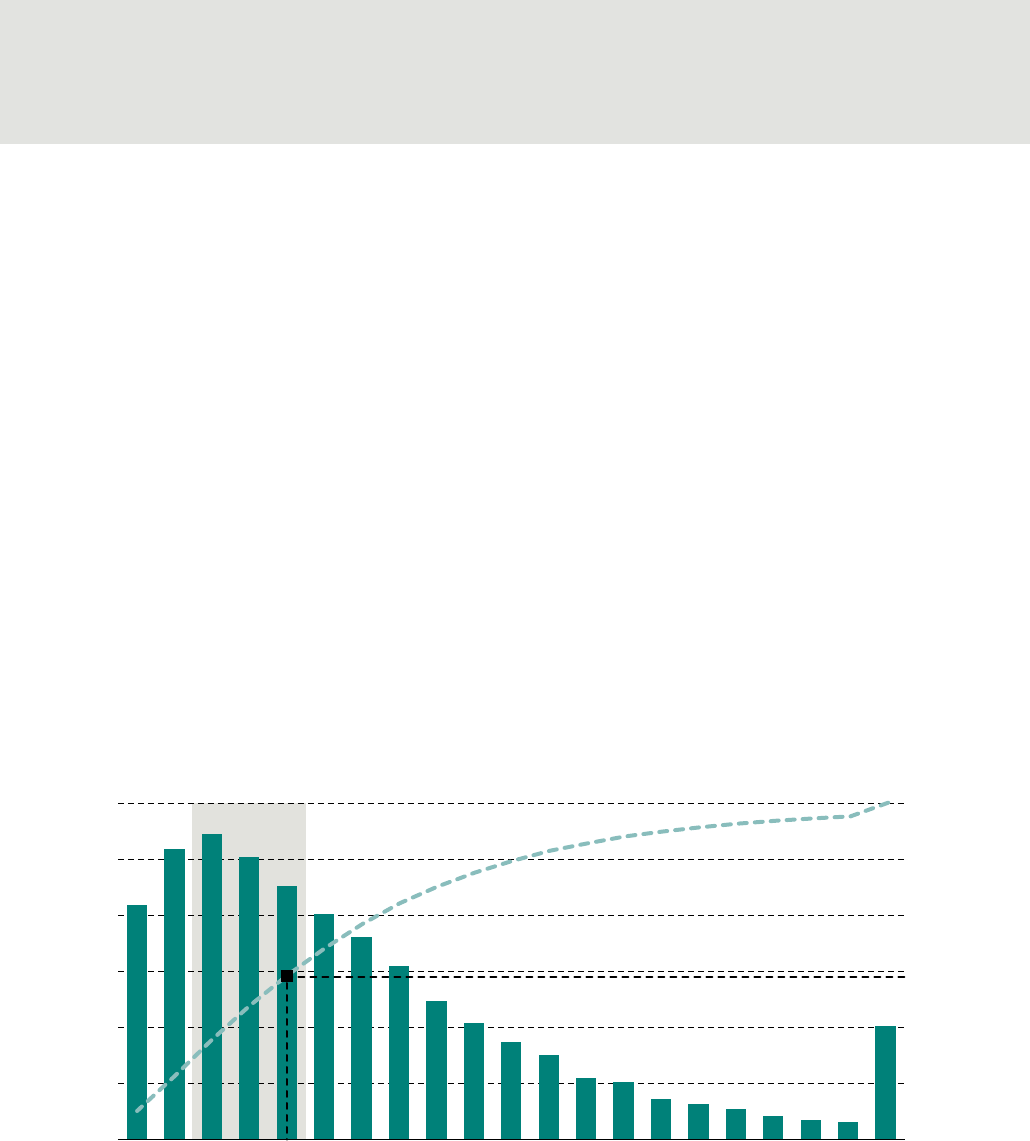

families earn $40,000 or less each year, 54 percent of families

earn $60,000 or less (demonstrated by the black dotted line),

and 76 percent of working-age families earn $100,000 or less.

For working-age families with children, earning over $100,000

is the exception, not the rule.

e vertical bars in gure 1, corresponding to the le axis,

show the percent of families that fall within various income

ranges. About 15 percent of working-age families (or

approximately 5.6 million families) earn between $1 and

$20,000 a year, while 19 percent of families (approximately

7.1 million families) earn between $20,001 and $40,000. On

the opposite end of the distribution, fewer than 3 percent of

families earn more than $260,000.

More than half of families in the United States

earn $60,000 or less per year.

More than half of America’s working-age families with

children under age eighteen (approximately 20.1 million

families) have annual incomes of $60,000 or below. is is

true whether we consider only earned wages and salary, or

if we use a broader denition of pretax, pretransfer income,

which also includes some unearned sources of income, such as

investment income and alimony payments. Figure 1 shows the

distributions for working-age families by (1) earned income,

and (2) pretax, pretransfer income. (Neither of these measures

includes taxes or transfer payments.)

e blue and green dotted lines in gure 1, corresponding

to the right axis, show the cumulative share of families with

income under various thresholds. Around 40 percent of

1.

Chapter 1: A Snapshot of Struggling Lower-Middle-Class Families

Income Distributions for Working-Age Families with Children Under 18

More than half of families in the United States earn $60,000 or less per year, and about three-fourths earn $100,000 or less.

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: A family is defined as a unit having at least one child under age eighteen and a family head under age sixty-five. A family’s earned income is the sum of each family member’s total pretax

wage and salary income. Pretax, pretransfer income is the sum of earned income and additional sources of nontransfer income (e.g., interest, dividends, or alimony). For more details, see the

technical appendix.

0

5

10

15

20

25

0

20

40

60

80

100

10

30

50

70

90

Pretax, pretransfer incomeEarned Income

1–20,000

0

20,001–40,000

40,001–60,000

60,001–80,000

80,001–100,000

100,001–120,000

120,001–140,000

140,001–160,000

160,001–180,000

180,001–200,000

200,001–220,000

220,001–240,000

240,001–260,000

260,001 or more

Percent of families

Family income (in dollars)

Cumulative percent of families

54 percent of families earn $60,000 or less.

and two children, the FPL was $23,283 (250 percent of the

FPL was $58,208); and for a family with two adults and three

children, the FPL was $28,087 (250 percent of the FPL was

$70,218) (U.S. Census Bureau 2012).

ese families’ proximity to the poverty line means that any

unanticipated downturns in income could push them into

poverty. For this reason, we could reasonably consider these

families to be the struggling lower-middle class. Figure 2

illustrates the income distribution relative to the FPL for

working-age families with children under age eighteen.

Together, these statistics (represented by the dotted black

line) reveal that nearly half of American families live either in

poverty or in the struggling lower-middle class.

Nearly one in ve American working-age families with

children lives in poverty, ocially dened as being below 100

percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Approximately 30

percent of families have incomes that place them between 100

and 250 percent of the FPL. Federal poverty thresholds vary

by family size and composition, meaning that families with

the same income, but with dierent household compositions,

can be in dierent positions relative to the FPL.

e U.S. Census Bureau dened the FPL in 2012 for a family

made up of one adult and one child to be $15,825 (250 percent

of the FPL for this family was therefore $39,563); for a family

with two adults and one child, the FPL was $18,480 (250

percent of the FPL was $46,200); for a family with two adults

Nearly half of families in the United States live

below 250 percent of the federal poverty level.

2.

Chapter 1: A Snapshot of Struggling Lower-Middle-Class Families

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: A family is defined as a unit having at least one child under age eighteen and a family head under age sixty-five. We constructed income relative to the FPL by dividing a family’s total income

(the sum of each family member’s total pretax personal income from all sources) by the Census Bureau’s corresponding official poverty threshold. The shaded gray area represents the struggling

lower-middle class (or 100 to 250 percent of the FPL). For more details, see the technical appendix.

Percent of families

Cumulative percent of families

Family income relative to the FPL (percent)

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

0–49

50–99

100–149

150–199

200–249

250–299

300–349

350–399

400–449

450–499

500–549

550–599

600–649

650–699

700–749

750–799

800–849

850–899

900–949

950–999

1000 and over

0

20

40

60

80

100

10

30

50

70

90

49 percent of families live below 250% of the federal poverty level.

Income Distribution for Working-Age Families with Children Under 18 Relative to the

Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

Almost one-third of American families are in the struggling lower-middle class, where any unanticipated downturns in income

could push them into poverty.

Struggling lower-middle-class families are

almost equally headed by single parents and

married couples.

3.

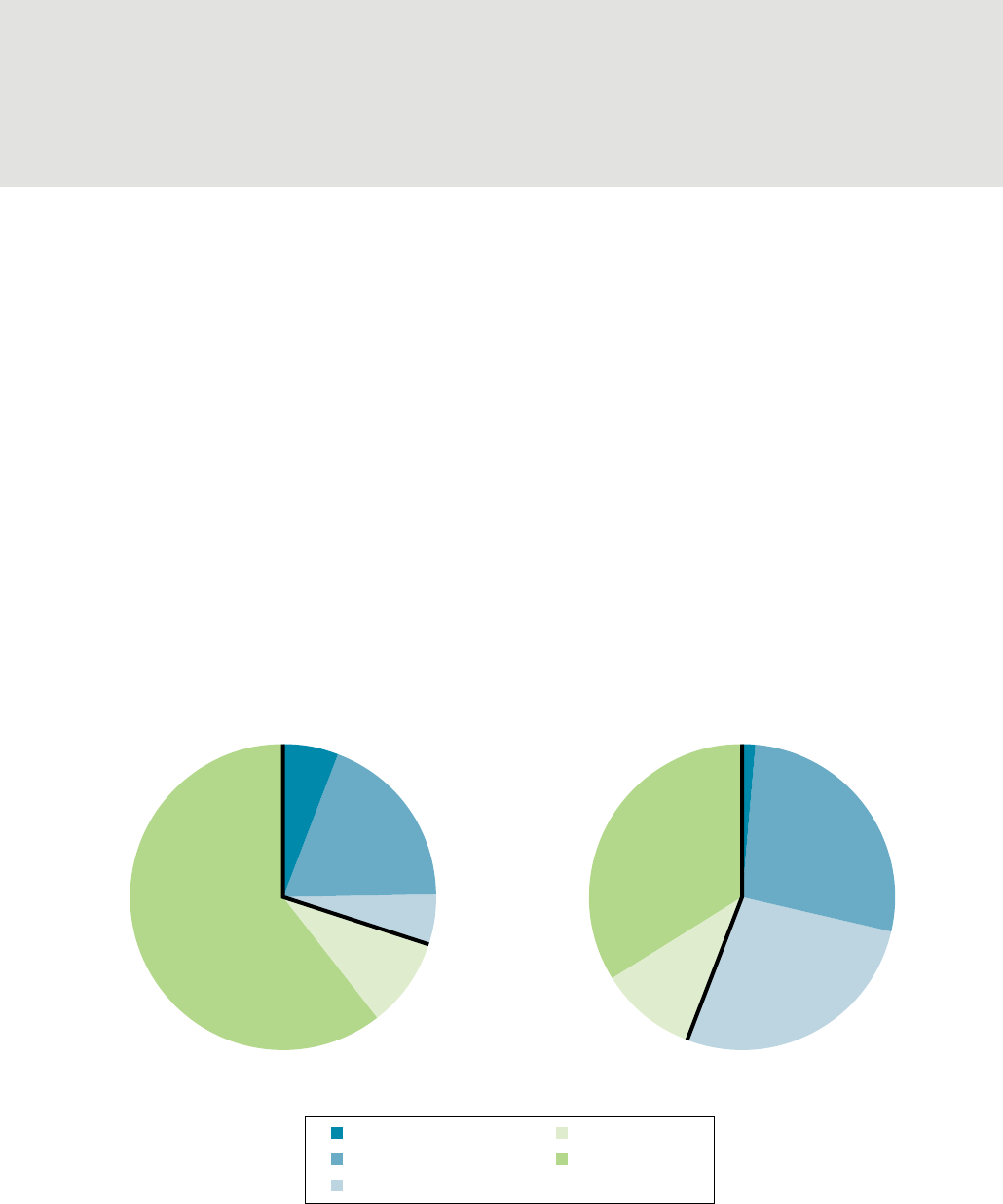

As illustrated in gure 3, household composition of families in

the struggling lower-middle class varies substantially from the

household composition of families in poverty. Of families with

income below the federal poverty level (FPL) (approximately

7.1 million families), 70 percent are headed by a single parent

(61 percent are single female parents), 24 percent are headed by

a married couple with one or two earners, and 6 percent are

headed by a married couple with no earners.

e composition of the struggling lower-middle class—dened

here as working-age families with children under age eighteen

whose income places them between 100 and 250 percent of the

FPL—is markedly dierent from families in poverty in terms of

marriage and number of earners. Of families in the struggling

lower-middle class (approximately 11.4 million families), 44

percent are headed by a single parent (34 percent are single

female parents), 27 percent are headed by a single-earner

married couple, another 27 percent are headed by a dual-earner

married couple, and 2 percent are headed by a married couple

with no earners.

Chapter 1: A Snapshot of Struggling Lower-Middle-Class Families

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: A family is defined as a unit having at least one child under age eighteen and a family head under age sixty-five. An earner is defined as an individual who has earnings greater than zero.

Single, male

Single, female

Married, zero earners

Married, one earner

Married, two earners

Below 100% of FPL Between 100% and 250% of FPL

6%

19%

5%

9%

61%

27%

27%

10%

34%

2%

Breakdown of Family Characteristics, by Income Relative to the Federal Poverty Level

(FPL)

In contrast to families in poverty, over half of struggling lower-middle-class families are headed by a married couple, and about

half of those married couples comprise two earners.

Nearly one out of two families in the

struggling lower-middle class is headed by an

adult who has attended college.

4.

College attainment diers markedly by poverty status. As

illustrated in gure 4, 33 percent of household family heads

below 100 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) attended

at least some college, although just 6 percent of those family

heads have a bachelor’s degree or higher. Among household

family heads with income between 100 and 250 percent of the

FPL, 48 percent have attended some college, and 14 percent

have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

In stark contrast to those living at or below 250 percent of the

FPL, 77 percent of household family heads above 250 percent

of the FPL attended at least some college, and about half have

a bachelor’s degree or higher. Only a very small share of this

group (4 percent) did not earn a high school diploma.

Chapter 1: A Snapshot of Struggling Lower-Middle-Class Families

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: A family is defined as a unit having at least one child under age eighteen and a family head under age sixty-five. The category “some college” includes an associate degree or having some

college, but no bachelor’s degree. Estimates may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding.

Bachelor's degree

More than college

Less than high school

High school diploma

Some college

Percent of family heads

0 20 40 60 80

100

10 30 50 70 90

32 35 27 5 1

17 34 34 11 3

4 28 3119 18

Below 100% of FPL

Between 100%

and 250% of FPL

Above 250% of FPL

Highest Educational Attainment of Family Head, by Income Relative to the Federal

Poverty Level (FPL)

Nearly one out of two family heads in the struggling lower-middle class has attended college; approximately one out of eight

family heads has a bachelor’s degree or more.

A majority of working-age families with children living below

the federal poverty level (FPL) receive federal transfer programs.

Of the families that rely on at least one government transfer

program, almost all receive food stamp benets through the

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Federal

transfer programs are not just for the very poor, however. As

shown in gure 5, approximately 33 percent of families with

incomes between 100 and 250 percent of the FPL depend on

at least one government transfer program for income support.

SNAP is by far the most prevalent transfer program for this

group, with 21 percent of these families (approximately 2.4

million families) depending on SNAP for food assistance at

some point during the year. It is important to note that families

only receive benets when their income is low, such as during

spells of unemployment, but not in months when their income

is higher than SNAP’s income threshold of 130 percent of the

FPL. is highlights the role of SNAP in supporting families

through temporary downturns, and the short-term dependence

on the program for many beneciaries.

Figure 5 shows only the share of families who depend on

various transfer programs in a single year; a much larger

share will rely on transfers at some point in their lives. For

example, while in any given year most Americans will not rely

on food stamps—approximately 17 percent of children under

age eighteen participated in SNAP in 2007 before the Great

Recession—between the ages of twenty and sixty-ve, more

than half of Americans will receive SNAP benets (Lein and

Wolkwitz 2009; Rank and Hirschl 2005; U.S. Census Bureau

2008). In addition to these transfer programs, tax credits, such

as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax

Credit (CTC), are important sources of income support for low-

to moderate- income families. ese two programs transferred

$59 billion and nearly $57 billion, respectively, in 2012 (e

Joint Committee on Taxation 2013).

Nearly one-third of struggling lower-middle-class

families rely on income support from a

government program.

5.

Chapter 1: A Snapshot of Struggling Lower-Middle-Class Families

Percent of Working-Age Families Who Receive Select Government Transfers, by Income

Relative to the Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

Many families in poverty and in the struggling lower-middle class rely on government transfers, with the Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program (SNAP) being by far the most common program.

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: A family is defined as a unit having at least one child under age eighteen and a family head under age sixty-five.

Between 100% and 250% of FPLBelow 100% of FPL

Percent of families

Supplemental

Security Income

Unemployment

benets

Welfare

benets

Disability

benets

SNAP Any of these

transfers

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

CHAPTER 2: The Struggling Lower-Middle Class,

Food Insecurity, and the Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program (SNAP)

Similar to families living in poverty, many families in America’s struggling lower-middle class

are not comfortably able to aord a sucient diet. Food insecurity in households with children

is widespread, existing in every state. e Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

serves a fundamental role in mitigating food insecurity and providing food assistance to both poor

and struggling lower-middle-class families.

6. Roughly 40 percent of children in the struggling lower-middle class

experience food insecurity or obesity, or both.

7. More than one in ve children faces food insecurity in thirty-seven

states and the District of Columbia.

8. Nearly 90 percent of Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program

(SNAP) recipients live in a household with at least one child, one

disabled individual, or one elderly individual.

Roughly 40 percent of children in the

struggling lower-middle class experience

food insecurity or obesity, or both.

6.

Children from low-income households have high rates of food

insecurity or obesity, or both. e U.S. Department of Agriculture

(USDA) classies a household as food insecure when it has

limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and

safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable

foods in socially acceptable ways (USDA 2000).

Figure 6 illustrates the diering nutritional circumstances of

children based on their family’s income. More than 10 percent

of children in households below the federal poverty level (FPL)

are both food insecure and obese, and more than 50 percent

have at least one of these conditions. Unfortunately, children

in the struggling lower-middle class—children whose family

income places them between 100 and 250 percent of the FPL—

more closely resemble children in poverty than they do children

in higher-income groups (above 250 percent of the FPL). More

than 24 percent of children (or approximately 1.7 million

children) in the struggling lower-middle class are food insecure

and approximately 23 percent are obese; almost 7 percent

of these children simultaneously face both obesity and food

Chapter 2: The Struggling Lower-Middle Class, Food Insecurity, and the Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

insecurity. In stark contrast, 85 percent of children living above

250 percent of the FPL face neither challenge. ese statistics

highlight the diverging nutritional conditions of children by

socioeconomic status.

Food insecurity, especially among children, is particularly

worrisome given the potential negative eects of hunger

during childhood. Studies have documented the importance

of early-life events, such as nutrition, on adult outcomes such

as earnings and mortality (Almond and Currie 2011). During

the initial rollout of the program in the 1960s, if mothers had

access to food stamps during pregnancy, their newborns had

higher birth weight (Almond et al. 2011). Academic research

has also shown that individuals who had access to food stamps

had markedly better long-run health than individuals who did

not have access to food stamps (Hoynes et al. 2012). Among

women, this study also found that access to food stamps during

childhood improved adult economic outcomes, ranging from

more education and higher lifetime earnings, to lessened

reliance on federal safety-net programs.

Sources: CDC 2001, 2012; authors’ calculations.

Note: The sample includes children aged twelve to seventeen. We classified children as obese if their body mass index (BMI) exceeds the 95th percentile BMI for each age and gender. Children

are considered food insecure if they live in a household that has limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in

socially acceptable ways (USDA 2000). For more details, see the technical appendix.

Obese, but not food insecure Food insecure, but not obeseBoth food insecure and obese

Percent of children

Below 100% of FPL Between 100% and 250% of FPL Above 250% of FPL

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Child Food Insecurity and Obesity Rates, by Income Relative to the Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

Children in families living below 250 percent of the FPL are much more likely to struggle with food insecurity and obesity than

are their higher-income peers.

the country, one in ten children is food insecure. Furthermore,

in thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia more than

one child in ve is food insecure, as represented in gure 7.

ere are regional patterns with regard to child food insecurity:

the most food-insecure states are consistently located in the

South and the West. Indeed, with the exception of Ohio, all of

the states with child food insecurity rates above 25 percent are

located in these two regions.

More than one in ve children faces food

insecurity in thirty-seven states and the

District of Columbia.

7.

Food insecurity exists everywhere in the United States, with

more than 16 percent of individuals living in households

reporting conditions indicating food insecurity (Coleman-

Jensen, Nord, and Singh 2013). e share of children living in

food-insecure households, approximately 22 percent, is even

higher (ibid.). e highest rates of child food insecurity in the

country are found in New Mexico and Washington, DC, where

roughly three out of ten children live in a household that is food

insecure. Even in North Dakota, the most food-secure state in

Chapter 2: The Struggling Lower-Middle Class, Food Insecurity, and the Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Child Food Insecurity Rates by State in 2011

Child food insecurity is widespread, with the highest rates appearing in the South and the West.

Source: Feeding America 2013.

Note: Children are considered food insecure if they live in a household that has limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire

acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways (USDA 2000).

15.0% to 19.9% 20.0% to 24.9%10.0% to 14.9% 25.0% and above

North Dakota

10.2%

Montana

21.8%

Washington

24.3%

Oregon

29.1%

Nevada

28.0%

California

27.3%

Utah

21.4%

Colorado

21.9%

New Mexico

30.6%

Texas

27.6%

Louisiana

23.5%

Arkansas

28.4%

Missouri

22.5%

Iowa

19.3%

Minnnesota

16.6%

Wisconsin

20.8%

Michigan

23.7%

Illinois

22.7%

Indiana

22.7%

Ohio

25.7%

Kentucky

22.4%

Tennessee

25.1%

Mississippi

27.4%

Georgia

28.8%

Florida

28.4%

South Carolina

27.4%

North Carolina

27.3%

Massachusetts

16.5%

Rhode Island

22.2%

Connecticut

19.8%

New Jersey

19.0%

Delaware

18.3%

Maryland

19.0%

D.C.

30.0%

Virginia

16.5%

West

Virginia

21.8%

Pennsylvania

20.5%

New York

22.0%

New Hampshire

14.7%

Vermont

19.3%

Maine

23.9%

Alabama

26.3%

Oklahoma

25.3%

Arizona

29.9%

Wyoming

18.0%

Idaho

23.0%

South Dakota

18.3%

Nebraska

21.0%

Kansas

22.6%

Alaska

20.3%

Hawaii

23.7%

however, and impose a time limit on the receipt of benets for

those who are not employed or in a work program at least half

time. Some of these policies can be suspended for areas with high

unemployment, and as a result, were suspended during the Great

Recession in most of the country, but have begun to be reinstated

throughout the country as the economy recovers.

Many of the participants (nearly 37 percent) live in single-

parent households with at least one child, but a sizable share

(more than 18 percent) live in households comprising married

adults with at least one child (Strayer, Eslami, and Lein

2012). In the year 2011 approximately 82 percent of SNAP

participants lived at or below the FPL in the month of SNAP

receipt, and these individuals received more than 91 percent of

all monthly SNAP benets (ibid.). In the same year, 45 percent

of SNAP participants were children, and 9 percent were elderly

individuals. SNAP’s benet expenditures were proportional,

with children receiving 44 percent of prorated SNAP benets

and elders receiving 7 percent (ibid.).

Nearly 90 percent of Supplemental Nutritional

Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients live in a

household with at least one child, one disabled

individual, or one elderly individual.

8.

e Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP)

caseload overwhelmingly comprises families with at least

one child, one disabled individual, or one elderly individual.

As illustrated in gure 8, 87 percent of SNAP participants in

2011 lived in such a household. e remaining 13 percent of

participants lived either in single-person or multiple-person

households that did not include at least one child, one disabled

individual, or one elderly individual.

SNAP participants who are aged eighteen to forty-nine, who are

not disabled, and who do not live with children are commonly

referred to as able-bodied adults without dependents, or ABAWDs;

they constitute roughly 10 percent of SNAP participants (Lee

2013). Most, but not all, of these ABAWDs are included within

the 13 percent of participants in gure 8. (ABAWDS can be in

the 87 percent if they themselves are able-bodied, aged eighteen

to forty nine, and live with an elderly or disabled person, but with

no children.) SNAP program rules typically require able-bodied

adults aged eighteen to forty-nine to satisfy work requirements,

Chapter 2: The Struggling Lower-Middle Class, Food Insecurity, and the Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Distribution of Participants Receiving Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP) Benets by Household Composition in 2011

The vast majority of SNAP beneciaries live in a house with at least one child, one disabled individual, or one elderly individual.

Source: Strayer, Eslami, and Leftin 2012.

Note: Nondisabled adults ages eighteen to forty-nine in childless households are subject to work requirements and a time limit. Elderly individuals are aged sixty or older. Children are aged

newborn to seventeen.

Participants in

households with

at least one child,

one disabled

individual, or one

elderly individual

87%

Nonelderly, nondisabled adult

participants without dependents

in single-person households

Nonelderly, nondisabled

adult participants

without dependents in

multiple-person households

10%

3%

CHAPTER 3: The Struggling Lower-Middle Class,

Taxes, and Transfer Programs

A variety of government tax and transfer programs augment the resources available to struggling

lower-middle-class families. e phase-out of these transfer programs, however, makes it dicult for

these families to work their way into a more stable economic life.

9. America’s tax and transfer system expands the middle class.

10. Struggling lower-middle-class families depend on an array of tax and

transfer benets.

11. A low-income, single parent can face a marginal tax rate as high as

95 percent.

12. The highest marginal tax rates tend to fall on the struggling lower-

middle class.

benet, such as a food voucher in the case of the Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

Figure 9 illustrates how the tax and transfer system changes the

distribution of income for working-age families with children.

Before taxes and transfers, about 5 percent of families have no

income, but this share falls to about 1 percent aer accounting

for taxes and transfers. Similarly, the share of families with

income between $1 and $20,000 falls from nearly 16 percent to

about 12 percent. On the other end of the income distribution,

there are fewer families in all of the income groups above

$80,000. e direct eect of the tax and transfer system is

to expand the middle class by compressing the number of

families located at either end of the income distribution and

raising the number of families in the middle range.

America’s tax and transfer system expands the

middle class.

9.

In the United States the system of taxes and transfers plays an

important role in determining the amount of income a family

ultimately has at its disposal. Taxes (such as federal and state

income taxes, payroll taxes, and property taxes) typically

reduce family income, but the tax system also provides credits

(such as the Earned Income Tax Credit [EITC] and the Child

Tax Credit [CTC]) that can increase the cash income for

qualifying families.

Transfer program and targeted tax benets protect families

against economic hardship and supplement low earnings,

which for some families could be zero. Some transfer programs

provide cash payments, such as Temporary Assistance for

Needy Families (TANF), and Supplemental Security Income

(SSI); others are in-kind programs, paying a nonmonetary

Chapter 3: The Struggling Lower-Middle Class, Taxes, and Transfer Programs

Income Distributions for Working-Age Families with Children Under 18 Before and

After Taxes

The tax and transfer system expands the middle class and leaves fewer families at either end of the income distribution.

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: A family is defined as a unit having at least one child under age eighteen and a family head under age sixty-five. Pretax, pretransfer income is the sum of earned income and additional

sources of nontransfer income (e.g., interest, dividends, or alimony). A family’s posttax, posttransfer income is the sum of pretax, pretransfer income, all transfer income (e.g., SNAP, welfare, or

unemployment benefits), property and payroll taxes, and state and federal taxes after tax credits. For more details, see the technical appendix.

Posttax, posttransfer incomePretax, pretransfer income

Percent of families

Family income (in dollars)

0

1–20,000

20,001–40,000

40,001–60,000

60,001–80,000

80,001–100,000

100,001–120,000

120,001–140,000

140,001–160,000

160,001–180,000

180,001–200,000

200,001–220,000

220,001–240,000

240,001–260,000

260,001 or more

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Median posttax, posttransfer income: $49,905

Median pretax, pretransfer income: $54,000

about $14,000 just below the FPL to about $7,500 at 250 percent

of the FPL.

While these programs undoubtedly improve the economic

security of low-income families, the programs’ impacts are not

included in the ocial measure of poverty. A family’s ocial

poverty status is based on pretax income, and thus does not

include benets received through the EITC or the Child Tax

Credit (CTC), nor does it include in-kind transfers, such as food

stamp benets, Medicaid, or housing assistance. Consequently,

ocial poverty estimates produced by the U.S. Census Bureau

reveal little to policymakers about the eect of these programs

on poverty and near-poverty rates. Additional measures of

poverty are needed to reveal the impact of the social safety net

on economic well-being in the United States (see Blank and

Greenberg 2008; and Meyer and Sullivan 2012).

Struggling lower-middle-class families depend on an

array of tax and transfer benets.

10.

Families living in poverty and among the struggling lower-

middle class have access to a number of income-support

programs. e nature and level of support of these programs

changes throughout the income distribution. For families below

the federal poverty level (FPL), the major transfer programs are

designed to provide for basic needs such as food and health care.

In addition, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is designed

to subsidize earnings. At higher levels of income, families have

access to child-related tax credits and health insurance exchange

subsidies implemented by the Aordable Care Act (ACA).

As shown in gure 10, struggling lower-middle-class families

benet from the EITC, Medicaid, and the Supplemental

Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), among other tax and

transfer benets. For the single-parent family with two children

illustrated in the gure, the total value of benets falls from

Chapter 3: The Struggling Lower-Middle Class, Taxes, and Transfer Programs

Tax and Transfer Benets for a Single Parent with Two Children by Household Earnings

in 2008

Most transfer programs phase out as families work their way into the lower-middle class.

Source: Maag et al. 2012.

Note: Figure shows value of tax and transfer benefits for a single parent with two children living in Colorado. Tax and transfer rules are for 2008 with hypothetical health insurance exchange

subsidy plans in 2014. CHIP is the Children’s Health Insurance Program. EITC is the Earned Income Tax Credit. SNAP is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. The shaded gray area

represents the struggling lower-middle class (or 100 to 250 percent of the FPL). For more details, see the technical appendix.

Value of benets (in dollars)

Household earnings (in dollars)

Earnings relative to federal poverty level (percent)

16,000

14,000

12,000

10,000

8,000

6,000

4,000

2,000

0

0

0 60 110 170 230 290 350 400 460 520 580

10,000 20,000 30,000 40,000 50,000 60,000 70,000 80,000 90,000 100,000

Exchange Subsidy (Adult)

Medicaid

CHIP

SNAP

Child and Dependent Care Credit

Child Tax Credit

EITC

Exchange Subsidy (Family)

A low-income, single parent can face a marginal

tax rate as high as 95 percent.

11.

e gap between the light and dark green lines in gure 11 shows

the eects of transfer phase-outs on this particular taxpayer’s

marginal tax rate: at the Medicaid limit, denoted by the rst

vertical black line, the phase-out of transfer benets increases her

marginal tax rate by about 60 percentage points—from around

negative 40 percent to about positive 20 percent. For this taxpayer,

the impact of transfer phase-outs could discourage additional

work that moves earnings beyond roughly $8,000. Low-income

households face a wide range of marginal tax rates depending on

program eligibility and family circumstances. As shown in this

gure, a low-income, single parent can face a marginal tax rate as

high as 95 percent.

Academic studies illustrate the complex impacts of tax and

transfer programs on worker behavior. For example, the EITC has

been shown to provide meaningful incentives for single parents

with children to work (Eissa and Liebman 1996; Meyer and

Rosenbaum 2001). For married mothers, however, the EITC tends

to provide a disincentive to work since the combined income of a

wife and husband reduces (and sometimes eliminates) a family’s

EITC benet (Eissa and Hoynes 2004a, 2004b).

Marginal tax rates for low-income families can be exceptionally

high. Marginal tax rates are the taxes paid on additional work

or investment. Eective marginal tax rates are determined by

taxes paid, tax benets received, and tax and transfer benets lost

due to extra income. For instance, as low- income families see an

increase in earnings, their transfer payments (such as Medicaid)

and tax credits (such as the Earned Income Tax Credit [EITC])

are phased out. is can raise eective marginal tax rates and

make the aer-tax return to additional earnings quite low.

In the absence of transfers, marginal tax rates tend to be low—

and oen negative—for low-income families. rough personal

deductions or exemptions, the tax code allows families to exclude

a share of their income from taxation. In addition, refundable tax

credits—tax credits that can drop a tax bill below zero—oen

make marginal tax rates negative. For the hypothetical taxpayer

illustrated in gure 11, marginal tax rates including taxes, but

not accounting for transfers, are around negative 40 percent,

indicating that these taxpayers would receive an additional 40

cents for every extra dollar earned. ese marginal tax rates turn

positive only at earnings of approximately $10,000.

Chapter 3: The Struggling Lower-Middle Class, Taxes, and Transfer Programs

Marginal Tax Rates under the System of Taxes and Transfers for a Hypothetical Single

Parent with One Child by Household Earnings in 2012

Given the phase-out of transfer programs and the progressivity of the tax code, the return to additional earnings can be close to

zero for many low-income workers.

Source: CBO 2012.

Note: The figures assume pre–American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) tax law. CHIP is the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

0

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 450

10,000 20,000 30,000 40,000 50,000 60,000

Tax rate (percent)

Earnings (in dollars)

Earnings relative to federal poverty level (percent)

Federal income, payroll, and state income taxes Plus transfer programs

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

100

Medicaid: Income

limit for parent

CHIP: Income limit for

free coverage

CHIP: Income limit for

reduced-cost coverage

The highest marginal tax rates tend to fall on the

struggling lower-middle class.

12 .

transfer programs will oen lose their benets if they earn

additional income, while ineligible families face lower marginal

tax rates because they do not have any benets to lose. As

a result, families with earnings higher up on the income

distribution, who as a group tend to be ineligible for transfer

programs, experience less variation in marginal tax rates.

High marginal tax rates for some low-income families are a

byproduct of safety-net programs that aim to provide means-

tested benets—benets aimed at low-income families—to the

most vulnerable households. An unfortunate consequence is

that some low-income households have little incentive to work

because they risk losing signicant benets as they move up the

income distribution.

High marginal tax rates can make the aer-tax return to

additional earnings quite low. is low return to work means

that, ultimately, families with high marginal tax rates have

limited ability to improve their own well-being.

Marginal tax rates—the tax collected on an additional amount

of income or earnings—are oen highest for families at or just

above the federal poverty level (FPL). Low- to moderate-income

families see an increase in marginal tax rates as their transfer

payments (such as Medicaid) and tax credits (such as the Earned

Income Tax Credit [EITC]) are clawed back or phased out.

As shown in gure 12, marginal tax rates are highest for those

families with income at or above the FPL. For example, 10

percent of families with earnings between 100 and 149 percent

of the FPL have marginal tax rates of 60 percent or higher—

meaning that these families keep 40 cents or fewer of each

additional dollar they earn. For the poorest families and for

those with incomes above 250 percent of the FPL, the top 10

percent of marginal tax rates fall around 35–45 percent.

Figure 12 also illustrates that there is far more variation in

marginal tax rates for families near the FPL than for families

farther from it. is disparity is primarily due to the varying

eligibility for transfer programs. Families that qualify for

Chapter 3: The Struggling Lower-Middle Class, Taxes, and Transfer Programs

Distribution of Marginal Tax Rates under 2012 Law, by Earnings Relative to the

Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

Due to the design of tax and transfer programs, families in the struggling lower-middle class face some of the highest marginal

tax rates in the population.

Source: CBO 2012.

Note: The figures assume pre–American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) tax law. CHIP is the Children’s Health Insurance Program. The shaded gray area represents the struggling lower-middle class

(or families whose income falls between 100 and 250 percent of the FPL).

0–49 50–99 100–149 150–199 200–249 250–299 300–349 350–399 400+

-10

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Tax rate (percent)

Earnings relative to FPL (percent)

Median 90th percentile10th percentile

Conclusion

Compared to families living in poverty, families in the

struggling lower-middle class are more likely to be headed

by a married couple, to have a second adult worker, and to be

headed by an individual with some college education. ose

in the struggling lower-middle class still face many of the

same challenges as those in poverty, however, including food

insecurity and a reliance on government programs for income

support.

ere are programs in place to assist the struggling lower-

middle class. In fact, nearly one-third of these families rely on

at least one government transfer program for income support

in any given year. For both the struggling lower-middle class

and families living in poverty, the Supplemental Nutritional

Assistance Program (SNAP) is by far the most prevalent

program. Low-income families benet from an array of tax

credits and transfer programs, such as the Earned Income Tax

Credit (EITC) and Medicaid. e phase-out of these programs

at near-poverty levels of income leads to high marginal tax

rates on low- to moderate-income families, however, lessening

the return to work and making economic security more

dicult for working families to achieve.

is policy paper presents a snapshot of America’s struggling

lower-middle-class families and highlights their challenges

with food insecurity and with barriers to work that are

inadvertently created through the tax and transfer system. An

important next step is to identify policies that can improve the

well-being of these families.

Blank, Rebecca M., and Mark H. Greenberg. 2008. “Improving

the Measurement of Poverty.” Discussion Paper 2008-17,

e Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, Washington,

DC. Available at http://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/

improving_the_measurement_of_poverty/.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2001.

“Data Table for BMI-for-age Charts.” Growth Charts.

Author, Washington, DC. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/

growthcharts/html_charts/bmiagerev.htm.

Coleman-Jensen, Alisha, Mark Nord, and Anita Singh. 2013.

“Household Food Security in the United States in 2012.”

Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture

(USDA), Washington, DC. Available at http://www.ers.usda.

gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err155.aspx#.

Un1lL_mkrYc.

Congressional Budget Oce (CBO). 2012. “Eective Marginal

Tax Rates for Low- and Moderate-Income Workers.”

Author, Washington, DC. Available at http://www.cbo.

gov/sites/default/les/cboles/attachments/11-15-2012-

MarginalTaxRates.pdf.

Eissa, Nada, and Hilary Hoynes. 2004a. “Taxes and Labor Market

Participation of Married Couples: e Earned Income Tax

Credit.” Journal of Public Economics 88: 1931–1958. Available

at http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/noe/jpube804.pdf.

———. 2004b. “e Hours of Work Response of Married Couples:

Taxes and the Earned Income Tax Credit.” In Tax Policy

and Labor Market Performance, edited by Jonas Agell and

Peter Birch Sørensen. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Available

at http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/noe/CESifo_

EissaHoynes.pdf.

Eissa, Nada, and Jerey B. Liebman. 1996. “Labor Supply Response

to the Earned Income Tax Credit.” Quarterly Journal of

Economics 111 (2): 605–637. Available at

http://qje.oxfordjournals.org/content/111/2/605.

Feeding America. 2013. “Map the Meal Gap: Highlights of Findings

for Overall and Child Food Insecurity.” Table 10. Author,

Chicago. Available at http://feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-

america/hunger-studies/map-the-meal-gap/~/media/Files/a-

map-2011/2011-mmg-exec-summary.ashx.

References

Primary Data Sources

e primary data sources include the National Health Interview

Survey (NHIS) produced by the National Center for Health

Statistics (NCHS) for the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC); and the March supplement to the Current

Population Survey (CPS), a survey conducted by the U.S.

Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics

(BLS). e CPS dataset was accessed through the Minnesota

Population Center’s Integrated Public Use Microdata Series

(IPUMS).

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2012. National

Health Interview Survey (NHIS). National Center for Health

Statistics (NCHS). Public-use data le and documentation.

Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_2012_data_

release.htm.

Current Population Survey (CPS)

King, Miriam, Steven Ruggles, J. Trent Alexander, Sarah Flood,

Katie Genadek, Matthew B. Schroeder, Brandon Trampe,

and Rebecca Vick. 2010. Integrated Public Use Microdata

Series (IPUMS), Current Population Survey (CPS): Version

3.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota.

Secondary Data Sources

Almond, Douglas, and Janet Currie. 2011. “Killing me Soly: e

Fetal Origins Hypothesis.” Journal of Economic Perspective

25 (3): 153–172. Available at http://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/

pdfplus/10.1257/jep.25.3.153.

Almond, Douglas, Hilary W. Hoynes, and Diane Whitmore

Schanzenbach. 2011. “Inside the War on Poverty: e Impact

of Food Stamps on Birth Outcomes.” Review of Economics

and Statistics 93 (2): 387–403. Available at http://www.

mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/REST_a_00089.

Autor, David H., Lawrence F. Katz, and Melissa S. Kearney. 2008.

“Trends in U.S. Wage Inequality: Revising the Revisionists.”

Review of Economics and Statistics 90 (2): 300–323. Available at

http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/rest.90.2.300.

Gunderson, Craig, Elaine Waxman, Emily Engelhard, Amy

Satoh, and Namrita Chawla. 2013. “Map the Meal Gap 2013:

Technical Brief.” Feeding America, Chicago. Available at

http://feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/hunger-

studies/map-the-meal-gap/~/media/Files/a-map-2011/2011_

technicalbrief_nal.ashx.

Hoynes, Hilary W., Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas

Almond. 2012. “Long Run Impacts of Childhood Access to

the Safety Net.” Working Paper 18535, National Bureau of

Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. Available at http://www.

nber.org/papers/w18535.

e Joint Committee on Taxation. 2013. “Estimates of Federal Tax

Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2012–2017.” Author, Congress of

the United States, Washington, DC. Available at https://www.

jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4503.

Lee, Helly. 2013. “SNAP Works: SNAP Work Requirements and

Time Limits.” Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP),

Washington, DC. Available at http://www.clasp.org/admin/

site/publications/les/SNAP-Work-Requirements-and-Time-

Limits-ABAWD.pdf.

Lein, Joshua, and Kari Wolkwitz. 2009. “Trends in Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program Participation Rates: 2000 to

2007.” Table B.3. Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department

of Agriculture (USDA), Washington, DC. Available at http://

www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/les/Trends2000-2007.pdf.

Maag, Elaine, C. Eugene Steuerle, Ritadhi Chakravarti, and Caleb

Quakenbush. 2012. “How Marginal Tax Rates Aect Families

at Various Levels of Poverty.” National Tax Journal 65 (4): 759–

782. Available at http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412722-

How-marginal-Tax-Rates-Aect-Families.pdf.

Meyer, Bruce D., and Dan T. Rosenbaum. 2001. “Welfare, the

Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Labor Supply of Single

Mothers.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 116 (3): 1063–1114.

Available at http://qje.oxfordjournals.org/content/116/3/1063.

Meyer, Bruce D., and James X. Sullivan. 2012, Fall. “Winning the

War: Poverty from the Great Society to the Great Recession.”

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Brookings Institution,

Washington, DC, 133–183. Available at http://www.brookings.

edu/~/media/Projects/BPEA/Fall%202012/2012b_Meyer.pdf.

Rank, Mark R., and omas A. Hirschl. 2005. “Likelihood of

Using Food Stamps during the Adulthood Years.” Journal of

Nutrition Education and Behavior 37 (3): 137–146.

Strayer, Mark, Esa Eslami, and Joshua Lein. 2012. “Characteristics

of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households:

Fiscal Year 2011.” Tables A.1, A.14, 3.4. Food and Nutrition

Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Washington,

DC. Available at http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/

les/2011Characteristics.pdf.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2008. “Vintage 2007: National Tables.”

“Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex and

Selected Age Groups for the United States: April 1, 2000 to

July 1, 2007 (NC-EST2007-02).” Population Division, Author,

Washington, DC. Available at http://www.census.gov/popest/

data/historical/2000s/vintage_2007/index.html.

———. 2011. “Frequently Asked Questions.” Author, Washington,

DC. Available at http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/

about/faqs.html.

———. 2012. “Poverty resholds.” “Poverty resholds by Size

of Family and Number of Children.” Social, Economic, and

Housing Statistics Division: Poverty. Author, Washington, DC.

Available at http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/

threshld/index.html.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2000. “Guide to

Measuring Household Food Security: Revised 2000.” Food

and Nutrition Service. Author, Washington, DC. Available at

http://www.fns.usda.gov/fsec/les/fsguide.pdf.

1. More than half of families in the United States earn

$60,000 or less per year.

Figure 1. Income Distributions for Working-Age Families

with Children Under 18

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: e sample consists of families, dened as a unit having

at least one child under age eighteen and a family head under

age sixty-ve. A family’s earned income is the sum of each

family member’s total pretax wage and salary income; pre-

income-tax nonfarm business and/or professional practice

income; and net pre-income-tax earnings as a tenant farmer,

sharecropper, or operator of the family’s own farm during the

previous calendar year. A family’s pretax, pretransfer income

is the sum of each family member’s earned income as well as

income from pension or retirement income from a previous

employer or union, or from other sources (excluding Social

Security and Veterans’ Administration payments); interest on

saving accounts, certicates of deposit, money market funds,

bonds, treasury notes, IRAs, and/or other investments that pay

interest; stocks and mutual funds; rent (aer expenses), charges

to roomers or boarders, and from money paid by estates, trusts,

and royalties; child support payments; alimony payments;

regular nancial assistance from friends or relatives not living

in the same household; and any pretax income that was not

reported in other, more-specic income variables (i.e., hobbies,

severance pay, and foster child care payments). Families with

negative income are included in the $0 earnings category.

2. Nearly half of families in the United States live

below 250 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL).

Figure 2. Income Distribution for Working-Age Families

with Children Under 18 Relative to the Federal Poverty

Level (FPL)

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: e sample consists of families, dened as a unit

having at least one child under age eighteen and a family

head under age sixty-ve. Families with negative income

are included in the 0–49 percent of the federal poverty level

(FPL) category. To determine a family’s position relative to the

FPL, we constructed each family’s income-to-poverty ratio

by dividing the CPS’ total income variable (the sum of each

family member’s total pretax personal income or losses from

all sources) by the Census Bureau’s poverty threshold for that

family. Using its income-to-poverty ratio, we then placed each

family into the corresponding income bin relative to the FPL.

3. Struggling lower-middle-class families are almost

equally headed by single parents and married couples.

Figure 3. Breakdown of Family Characteristics, by Income

Relative to the Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: e sample consists of families, dened as a unit having

at least one child under age eighteen and a family head under

age sixty-ve. A family is below 100 percent of the FPL if its

income-to-poverty ratio is below 1.0. (at ratio is constructed

by dividing the CPS’ total income variable by the ocial

poverty threshold used by the Census Bureau to evaluate the

poverty status of each family.) A family is between 100 and

250 percent of the FPL if its income-to-poverty ratio is greater

than or equal to 1.0 and less than or equal to 2.5. An earner is

dened as an individual who has earned income greater than

zero. Individuals are considered married if they are married

and their spouse is present, and single otherwise.

4. Nearly one out of two families in the struggling

lower-middle class is headed by an adult who has

attended college.

Figure 4. Highest Educational Attainment of Family Head,

by Income Relative to the Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: e sample consists of families, dened as a unit having

at least one child under age eighteen and a family head

under age sixty-ve. A family is below 100 percent of the

FPL if its income-to-poverty ratio is below 1.0. (at ratio is

constructed by dividing the CPS’ total income variable by the

Census Bureau’s corresponding poverty threshold.) A family

is between 100 and 250 percent of the FPL if its income-to-

poverty ratio is greater than or equal to 1.0 and less than or

equal to 2.5. A family is above 250 percent of the FPL if its

income-to-poverty ratio is greater than 2.5.

“Less than high school” indicates individuals who do not

have a high school diploma. “High school diploma” indicates

individuals who have a high school diploma or equivalent.

“Some college” indicates individuals who have an associate

degree (occupational/vocational or academic program) or

some college, but do not have a bachelor’s degree. “Bachelor’s

Technical Appendix

22

degree” indicates individuals who have a bachelor’s degree.

“More than college” indicates individuals who have a master’s

degree, professional school degree, or doctorate degree.

5. Nearly one-third of struggling lower-middle-class

families rely on income support from a government

program.

Figure 5. Percent of Working-Age Families Who Receive

Select Government Transfers, by Income Relative to the

Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: e sample consists of families, dened as a unit

having at least one child under age eighteen and a family

head under age sixty-ve. A family is below 100 percent of

the FPL if its income-to-poverty ratio is below 1.0. (at ratio

is constructed by dividing the CPS’ total income variable

by the ocial poverty threshold used by the Census Bureau

to evaluate the poverty status of each family.) A family is

between 100 and 250 percent of the FPL if its income-to-

poverty ratio is greater than or equal to 1.0 and less than or

equal to 2.5. A family receives Supplemental Security Income

(SSI), unemployment benets, welfare benets, disability

benets, or Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program

(SNAP) benets if at least one of the family members had

income greater than zero from SSI, unemployment benets,

welfare benets, disability benets, or SNAP benets,

respectively. A family receives any of these transfers if it

receives income greater than zero from at least one of these

ve government programs.

6. Roughly 40 percent of children in the struggling

lower-middle class experience food insecurity or

obesity, or both.

Figure 6. Child Food Insecurity and Obesity Rates, by

Income Relative to the Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

Sources: CDC 2001, 2012; authors’ calculations.

Note: e sample consists of children ages twelve to

seventeen. A child is below 100 percent of the FPL if her

family’s income-to-poverty ratio is below 1.0. A child is

between 100 and 250 percent of the FPL if her family’s

income-to-poverty ratio is greater than or equal to 1.0 and

less than 2.5. A child is above 250 percent of the FPL if her

income-to-poverty ratio is greater than or equal to 2.5.

Following the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA)

denition, a child lives in a food-insecure household if her

household-level food security status is “low food security” or

“very low food security” (Coleman-Jensen, Nord, and Singh

2013). Children are considered food insecure if they live

in a household that has limited or uncertain availability of

nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or limited or uncertain

ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways

(USDA 2000). To measure a household’s food security status,

adults in the Current Population Survey (CPS) are asked a

series of questions ranging from questions about whether

they experienced worry that they would run out of money

for food; to whether an adult in the family has had to skip a

meal, go hungry, or go for a day without eating because there

was not enough money for food; to whether a child in the

family had to skip a meal, go hungry, or go for a day without

eating. If a household answers “yes” to none or very few of

the questions, it is considered to be food secure. Households

that answer “yes” to more of the questions are classied as

food insecure or as having very low food security (a more

severe designation) (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2013).

To determine a child’s obesity status, the average 95th

percentile body mass index (BMI) values for each age and

gender were calculated by averaging the monthly 95th

percentile BMI values for the respective age (in months) and

gender. We consider a child obese if that child’s BMI is greater

than the average 95th percentile BMI for the corresponding age

and gender.

7. More than one in ve children faces food insecurity

in thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia.

Figure 7. Child Food Insecurity Rates by State in 2011

Source: Feeding America 2013.

Note: Original data come from the 2011 Core Food Security

Module of the Current Population Survey. For more details,

see Gunderson et al. (2013). Following the USDA’s denition,

a child lives in a food-insecure household if her household-

level food security status is “low food security” or “very low

food security” (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2013). Children are

considered food insecure if they live in a household that has

limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate

and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire

acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways (USDA 2000).

To measure a household’s food security status, adults in the

CPS are asked a series of questions ranging from questions

about whether they experienced worry that they would run

out of money for food; to whether an adult in the family has

had to skip a meal, go hungry, or go for a day without eating

because there was not enough money for food; to whether a

child in the family had to skip a meal, go hungry, or go for a

day without eating. If a household answers “yes” to none or

very few of the questions, it is considered to be food secure.

Households that answer “yes” to more of the questions are

classied as food insecure or as having very low food security

(a more severe designation) (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2013).

8. Nearly 90 percent of SNAP recipients live in a

household with at least one child, one disabled

individual, or one elderly individual.

Figure 8. Distribution of Participants Receiving

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

Benets by Household Composition in 2011

Source: Strayer, Eslami, and Lein 2012.

Note: Original data come from the scal year 2011 SNAP

Quality Control sample.

9. America’s tax and transfer system expands the

middle class.

Figure 9. Income Distributions for Working-Age Families

with Children Under 18 Before and Aer Taxes

Sources: CPS 2012, March supplement; authors’ calculations.

Note: e sample consists of families, dened as a unit

having at least one child under age eighteen and a family

head under age sixty-ve.

A family’s pretax, pretransfer income is the sum of each

family member’s earned income as well as income from

pension or retirement income from a previous employer

or union, or from other sources (excluding Social Security

and Veterans’ Administration payments); interest on saving

accounts, certicates of deposit, money market funds,

bonds, treasury notes, IRAs, and/or other investments that

pay interest; stocks and mutual funds; rent (aer expenses),

charges to roomers or boarders, and from money paid

by estates, trusts, and royalties; child support payments;

alimony payments; regular nancial assistance from friends

or relatives not living in the same household; and any pretax

income that was not reported in other, more-specic income

variables (i.e., hobbies, severance pay, and foster child care

payments).

A family’s posttax and posttransfer income is the sum

of a family’s total income; the total value of food stamps

received by the household; the amount of federal and state

tax liability aer tax credits (including the additional Child

Tax Credit [CTC] and the Earned Income Tax Credit [EITC])

are deducted; the total Social Security retirement payroll

deductions for an individual or for a couple ling a joint tax

return; and the amount of annual property taxes that the

household paid during the previous calendar year.

Families with negative income are included in the $0 earnings

category. Following the U.S. Census Bureau (2011) denition,

median income (for both pretax, pretransfer income and

posttax, posttransfer income) is the income level that divides

the income distribution into two equal groups: half of

American families have income above that amount and half of

American families have income below that amount.

10. Struggling lower-middle-class families depend on

an array of tax and transfer benets.

Figure 10. Tax and Transfer Benets for a Single Parent

with Two Children by Household Earnings in 2008

Source: Maag et al. 2012.

Note: Reproduction of gure 1 from Maag et al. (2012). For

the purposes of this exercise, gure 10 does not include

the recovery rebate credit and the dependent exemption.

Health value estimates are based on Medicaid spending

and insurance premiums as reported by the Kaiser Family

Foundation. Coverage varies by source: Medicaid and

Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) benets are

more comprehensive and have less cost-sharing than do those

in the health insurance exchange subsidies. Medicaid and

CHIP also pay providers at lower rates than private insurers

for services. A secondary horizontal axis representing the

FPL was added for further analysis, using original data

from Maag et al. 2012. e gray shaded area represents the

struggling lower-middle class, or households with earnings

between 100 and 250 percent of the FPL.

11. A low-income, single parent can face a marginal

tax rate as high as 95 percent.

Figure 11. Marginal Tax Rates under the System of Taxes

and Transfers for a Hypothetical Single Parent with One

Child by Household Earnings in 2012

Source: CBO 2012.

Note: Reproduction of fourth panel of gure 2 from CBO

(2012).

12. e highest marginal tax rates tend to fall on the

struggling lower-middle class.

Figure 12. Distribution of Marginal Tax Rates under 2012

Law, by Earnings Relative to the Federal Poverty Level

(FPL)

Source: CBO 2012.

Note: Reproduction of gure 5 from CBO (2012). e gray

shaded area represents the struggling lower-middle class,

or households with earnings between 100 and 250 percent of

the FPL.

24

Hamilton Project Papers on the

Struggling Lower-Middle Class

• “GivingSecondaryEarnersaTaxBreak:AProposaltoHelp

Low-andMiddle-IncomeFamilies”

Melissa S. Kearney and Lesley J. Turner propose a secondary-

earner deduction as a reform to the tax code that would help

secondary earners keep more of the money they earn and

increase the families’ take-home pay.

• “StrengtheningSNAPforaMoreFood-Secure,Healthy

America”

Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach proposes a series of targeted

reforms to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP) to strengthen the program while still retaining its

fundamental role as a cornerstone of our nation’s social

safety net.

• “ImprovingtheMeasurementofPoverty”

Rebecca M. Blank and Mark H. Greenberg discuss the need for

a new national poverty measure that better reects the actual

economic conditions of low-income Americans.

• “GettingMorefromLow-IncomeHousingAssistance”

Edgar O. Olsen examines shortfalls with the current system of

low-income housing assistance and proposes a transition to an

entitlement housing assistance program that relies exclusively

on tenant-based assistance.

• “BetterWorkersforBetterJobs:ImprovingWorker

AdvancementintheLow-WageLaborMarket”

Harry J. Holzer proposes a new federal funding stream to

identify, expand, and replicate the most successful state and

local initiatives designed to spur the advancement of low-wage

workers in the United States.

• “Employment-BasedTaxCreditsforLow-SkilledWorkers”

John Karl Scholz proposes increasing the return to work for low-

income families through the expansion the earned income tax

credit for low-income childless taxpayers and the creation of a

targeted wage subsidy in certain economically depressed areas.

• “NewHope:FulllingAmerica’sPromiseto‘MakeWork

Pay’”

Johannes M. Bos, Greg J. Duncan, Lisa A. Gennetian, and

Heather D. Hill evaluate the New Hope program—designed

to assist workers by providing work supports including access

to quality child care and health insurance—and provide

recommendations for scaling it up nationally.

• “FundamentalRestructuringofUnemploymentInsurance:

Wage-LossInsuranceandTemporaryEarningsReplacement

Accounts”

Jerey R. Kling proposes to restructure social insurance aer

job loss in order to improve protection against long-term

eects of unemployment, provide more progressive allocation

of benets, reduce incentives for rms to lay o workers, and

encourage reemployment.

• “ReformingUnemploymentInsuranceforthe21stCentury

Workforce”

Lori G. Kletzer and Howard Rosen outlinethree broad reforms

to update the unemployment insurance system, which has not

been updated since 1935 and is in need of reform to meet the

needs of today’s workforce.

• “ImprovingOpportunitiesandIncentivesforSavingby

Middle-andLow-IncomeHouseholds”

William G. Gale, Jonathan Gruber, and Peter Orszag propose

changing the default features of retirement savings and

creating new matching programs to incentivize people to save.

Advisory CounCil

GEORGE A. AKERLOF

Koshland Professor of Economics

University of California, Berkeley

ROGER C. ALTMAN

Founder & Executive Chairman

Evercore

ALAN S. BLINDER

Gordon S. Rentschler Memorial Professor

of Economics & Public Affairs

Princeton University

TIMOTHY C. COLLINS

Senior Managing Director

& Chief Executive Officer

Ripplewood Holdings, LLC

JONATHAN COSLET

Senior Partner & Chief Investment Officer

TPG Capital, L.P.

ROBERT CUMBY

Professor of Economics

Georgetown University

JOHN DEUTCH

Institute Professor

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

CHRISTOPHER EDLEY, JR.

Dean and Professor, Boalt School of Law

University of California, Berkeley

BLAIR W. EFFRON

Founding Partner

Centerview Partners LLC

JUDY FEDER

Professor & Former Dean

Georgetown Public Policy Institute

Georgetown University

ROLAND FRYER

Robert M. Beren Professor of Economics

Harvard University

CEO, EdLabs

MARK T. GALLOGLY

Cofounder & Managing Principal

Centerbridge Partners

TED GAYER

Vice President & Director

of Economic Studies

The Brookings Institution

TIMOTHY GEITHNER

RICHARD GEPHARDT

President & Chief Executive Officer

Gephardt Group Government Affairs

ROBERT GREENSTEIN

President

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

MICHAEL GREENSTONE

3M Professor of Environmental Economics

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

GLENN H. HUTCHINS