Money Laundering

Introduction.................................................... 1

By Richard Weber

Suspicious Activity Reports Disclosure and Protection. ................ 2

By Lester Joseph

Money Laundering Trends . ..................................... 1 4

By Emery Kobor

The Money Laundering Statutes (18 U.S.C. §§ 1956 and 1957). ........ 2 1

By Stefan D. Cassella

One-Hour Money Laundering: Prosecuting Unlicensed Money

Transmitting Businesses Using Section 1960......................... 3 4

By Courtney J. Linn

Bulk Cash Smuggling. .......................................... 4 1

By Rita Elizabeth Foley

Sources of Information in a Financial Investigation................... 4 8

By Alan Hampton

Criminal Prosecution of Banks Under the Bank Secrecy Act........... 5 4

By Lester Joseph and John Roth

September

2007

Volume 55

Number 5

United States

Department of Justice

Executive Office for

United States Attorneys

Washington, DC

20530

Kenneth E. Melson

Director

Contributors' opinions and

statements should not be

considered an endorsement by

EOUSA for any policy, program,

or service.

The United States Attorneys'

Bulletin is published pursuant to

28 CFR § 0.22(b).

The United States Attorneys'

Bulletin is published bimonthly by

the Executive Office for United

States Attorneys, Office of Legal

Education, 1620 Pendleton Street,

Columbia, South Carolina 29201.

Managing Editor

Jim Donovan

Program Manager

Nancy Bowman

Internet Address

www.usdoj.gov/usao/

reading_room/foiamanuals.

html

Send article submissions and

address changes to Program

Manager, United States Attorneys'

Bulletin,

National Advocacy Center,

Office of Legal Education,

1620 Pendleton Street,

Columbia, SC 29201.

In This Issue

SEPTEMBER 2007 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN 1

Intr oduction

Richard Weber

Chief, Asset Forfeiture and Money

Laundering Section

Criminal Division

Money laundering constitutes a significant

threat to the safety of our communities, the

integrity of our financial institutions, and our

national security. In order to effectively address

this serious threat, the best efforts to apply and

coordinate all of the available resources of the

federal government, along with those of state and

local authorities, as well as our foreign

counterparts, must be used. The United States

Department of Justice is fully committed to using

the money laundering and asset forfeiture statutes

to the fullest extent possible. They will be used to

identify, investigate, and prosecute those who

launder the illegal proceeds of terrorists, drug

traffickers, fraud perpetrators, organized crime

organizations, and other criminals, and to seize

and forfeit their ill-gotten assets.

In recent years, crime has become

increasingly international in scope, and the

financial aspects of crime have become more

complex. This is due to the rapid advances in

technology and the globalization of the financial

services industry. Modern financial systems

permit criminals to transfer millions of dollars

instantly though personal computers and satellite

dishes. Money is laundered through currency

exchange houses, stock brokerage houses, gold

dealers, casinos, automobile dealerships,

insurance companies, trading companies, and

other sophisticated systems. Private banking

facilities, offshore banking, shell corporations,

free trade zones, wire systems, and trade financing

all have the ability to mask illegal activities. The

criminal's choice of money laundering vehicles is

limited only by his or her creativity. Ultimately,

this laundered money flows into global financial

systems where it can undermine national

economies and currencies.

Organized criminal groups transcend national

borders and extend their influence to areas of the

world far-removed from their countries of origin.

The gradual erosion of border controls in the

countries of Europe not only contributes to the

free flow of trade and commerce, but also

increases the threat of transborder financial

crimes. This internationalization of crime makes

the sharing, collating, and analysis of information,

among and within governments, essential.

Organized criminals are motivated by one

thing—profit. Greed drives the criminal. Huge

sums of money are generated through drug

trafficking, arms smuggling, white collar crime,

human trafficking, terrorism, and corruption. The

end result is that organized crime moves billions

of illegally-gained dollars into our nation's

legitimate financial systems. The success of

organized crime is based upon its ability to

launder money.

The challenges facing law enforcement in this

environment make it necessary for investigators

and prosecutors to have all the legal and

regulatory tools, as well as international legal

assistance mechanisms available to them, to keep

up with, and ahead of, those who launder the

proceeds of crime. To effectively combat such

criminal activity, law enforcement must have the

means that are at least as sophisticated, if not

more so, than the criminals.

The money laundering statutes Congress

provided, both in the Bank Secrecy Act and the

Criminal Code, are major weapons in the war

against the laundering of drug trafficking proceeds

and other serious crimes. These weapons gut the

economic base that these criminals need to operate

and stops them from continuing business as usual,

which is integral to the fight against terrorism. It

also prevents replacement of members who have

been incarcerated. Another tangential benefit is

the deterrence of crime. Greed is one of the

primary reasons for criminal activity. Asset

forfeiture removes this incentive by denying

criminals the assets illegally acquired. Not only

will they go to jail, but they will not realize any

economic gain from the crime.

Investigating and prosecuting money

laundering and forfeiting criminal assets can be a

long, arduous, and complex process. It is critical

to bear in mind, however, that it is more than a

bloodless exercise in accounting. When the crime

of money laundering is fought, organized crime is

fought. The fight against money laundering

accomplishes the following goals, among many

others.

2UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN SEPTEMBER 2007

• Keeps drugs out of playgrounds and away

from children.

• Safeguards the human dignity of women and

children trafficked into forced labor and

prostitution.

• Most importantly, keeps funding out of the

hands of terrorists.

The Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering

Section (AFMLS) releases several publications,

including the monthly Asset Forfeiture Quick

Release (new forfeiture case law) and the bi-

monthly Asset Forfeiture News. This edition of

the United States Attorneys' Bulletin supplements

those publications and is intended to provide an

overview of the money laundering statutes and a

survey of some of the tools that can be used in

financial investigations. A future edition of the

Bulletin will focus on asset forfeiture and provide

a series of articles on that topic.

The articles in this edition of the Bulletin

cover several topics, including those listed below.

• An overview of the statutes used to combat

money laundering, including the primary

money laundering statutes (18 U.S.C. §§ 1956

and 1957), the Bulk Cash Smuggling statute

(31 U.S.C. § 5332), and the Unlicensed

Money Remitting Statute (18 U.S.C. § 1960).

• Money laundering trends and techniques.

• Tools to use in financial investigations.

• The use and disclosure of Suspicious Activity

Reports in investigations.

• Criminal enforcement actions against banks

for the failure to file Suspicious Activity

Reports or to have effective Anti-Money

Laundering programs.

The AFMLS is committed to using the money

laundering statutes to the fullest extent possible

and stands ready to give whatever support and

advice is needed in prosecuting money laundering

and asset forfeiture cases.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Richard Weber has served as the Chief of the

Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section

since March 2005. Prior to that, he was an

Assistant United States Attorney in the Eastern

District of New York, serving as Deputy Chief of

the Civil Division and Chief of the Asset

Forfeiture Unit. Rich first joined the Department

under the Attorney General's Honor Program. His

expertise in asset forfeiture and money laundering

has developed from prosecuting over 100 complex

international and domestic money laundering and

asset forfeiture cases. Among many others, he

prosecuted U.S. v. Blarek/Pellecchia, 166 F.3d

1202 (2d Cir. 1998) (interior decorators were

convicted of laundering millions of dollars of drug

proceeds for the leader of the Cali cartel and

forfeited $7 million dollars); U.S. v. Jordan

Belfort and Daniel Porush, 98-cr-00859-JG (E.D.

N.Y. Oct. 14, 2003) (where an international

securities fraud money laundering investigation

resulted in the forfeiture of $15 million dollars);

and U.S. v. Palm View Corp, 99-cr-00702-ILG

(E.D. N.Y. July 21, 2000) (which involved

gambling proceeds and the forfeiture of $6 million

dollars).a

Suspicious Activity Reports Disclosure

and Protection

Lester Joseph

Principal Deputy Chief

Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering

Section

Criminal Division

I. Introduction

Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) have

become one of law enforcement's most valuable

tools for detecting and investigating criminal

activity. Banks have been notifying law

enforcement of suspected criminal activity for

many years, either by submitting Criminal

SEPTEMBER 2007 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN 3

Referral Forms or by checking the "suspicious"

box on the old Currency Transaction Reports

(CTRs). The modern SAR program came into

effect on April 1, 1996, when the Treasury

Department regulations requiring banks to file

SARs became effective. See 31 C.F.R. § 103.18.

Other types of financial institutions have

subsequently been required to file SARs as of the

dates shown in Figure 1. As of 2006, the financial

institutions shown in Figure 2 have filed more

than four million SARs.

The SAR system is designed to assist the law

enforcement community by requiring financial

institutions to report transactions that are

indicative of possible violations of law or

regulation. The required threshold for filing is

easily triggered, simply by suspicions, not proof,

of illegal activity. The information contained in

SARs constitutes raw allegations of the most

sensitive kind, precisely because the reported

"suspicions" are unsubstantiated and unproven.

Financial institutions file SARs with the

expectation that they will be accorded sensitive

treatment. Unnecessary disclosure of SARs could

frustrate that expectation and have a chilling

effect on both the quantity and the quality of

future SAR filings. Moreover, SARs may contain

information concerning the methods by which an

institution learned of or uncovered suspicious

activity, possibly allowing other potential

wrongdoers to take action to avoid those methods

of detection. Therefore, it is essential that law

enforcement agencies and prosecutors take

measures to ensure that the existence of a SAR or

its contents are not disclosed unless absolutely

necessary or required by law.

II. Protection and disclosure by

financial institutions

Financial institutions have a significant

interest in protecting SARs from disclosure.

Institutions are generally reluctant to publicize the

fact that they have filed SARs on their customers,

and certainly do not want their customers to know

that they have reported their activity to the

government. This reluctance is based upon both

business and safety concerns. Institutions know

that their customers would not be pleased to have

their suspicious transactions reported to the

government, and are also concerned about

retaliation from customers whose transactions

have been reported. This is especially true in

small communities where it would be obvious

which institution or employee filed the SAR.

However, to ensure that complicit or corrupt bank

officers do not tip off a customer concerning the

filing of a SAR, 31 U.S.C. § 5318(g) includes the

following provision.

(2) NOTIFICATION PROHIBITED.--

(A) IN GENERAL.--If a financial institution

or any director, officer, employee, or agent of

any financial institution, voluntarily or

pursuant to this section or any other authority,

reports a suspicious transaction to a

government agency--

(i) the financial institution, director, officer,

employee, or agent may not notify any person

involved in the transaction that the transaction

has been reported....

The SAR statutory scheme also contains a

"safe harbor" provision that protects financial

institutions from civil liability resulting from the

reporting of suspicious transactions.

(A) IN GENERAL.--Any financial institution

that makes a voluntary disclosure of any

possible violation of law or regulation to a

government agency or makes a disclosure

pursuant to this subsection or any other

authority, and any director, officer, employee,

or agent of such institution who makes, or

requires another to make any such disclosure,

shall not be liable to any person under any law

or regulation of the United States, any

constitution, law, or regulation of any State or

political subdivision of any State, or under

any contract or other legally enforceable

agreement (including any arbitration

agreement), for such disclosure or for any

failure to provide notice of such disclosure to

the person who is the subject of such

disclosure or any other person identified in the

disclosure.

31 U.S.C. § 5318(g)(3).

The major issue that courts have disagreed on

is whether the safe harbor provision is an

unqualified privilege or whether there is a good

faith belief requirement in the language of the

statute. In Lopez v. First Union Nat'l Bank, 129

F.3d 1186 (11th Cir. 1997), an account holder

filed a lawsuit against the bank alleging inter alia

violations of the Right to Financial Privacy Act

after the bank notified law enforcement that there

were unusual movements of money in certain

accounts at the bank. The court dismissed the

4UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN SEPTEMBER 2007

complaint based on its conclusion that § 5318(g)

immunized the bank from liability. The Eleventh

Circuit reversed the dismissal, finding that "there

must be some good faith basis for believing [that]

there is a nexus between the suspicion of illegal

activity and the account or accounts from which

information was disclosed." Id. at 1195. The court

was concerned because the bank disclosed

information about 1,100 accounts based on

"unusual movements of money at the bank," but

may not have had a good faith basis for believing

that there was suspicious activity in each of the

1,100 accounts. Id.

The Second Circuit ruled differently two

years later in Lee v. Bankers Trust Co., 166 F.3d

540 (2d Cir. 1999), holding that there is no good

faith requirement in §5318(g). Lee, a former

managing director for Bankers Trust, brought an

action alleging that the bank defamed him through

its conduct in investigating wrongdoing with

respect to the transfer of unclaimed accounts and

through the alleged filing of a SAR after he was

asked to resign. In affirming the District Court's

granting of a motion to dismiss, the Second

Circuit stated, "The plain language of the safe

harbor provision describes an unqualified

privilege, never mentioning good faith or any

suggestive analogue thereof." Id. at 544. The court

also noted that a good faith requirement made no

sense because, if the bank sought summary

judgment, it would have to establish that the

statements in the SAR were made in good faith,

but it would be prohibited by law both from

disclosing the filing or the contents of a SAR.

Further, the court noted that an earlier draft of the

safe harbor provision included an explicit good

faith requirement, but that the requirement was

not included in the bill that was finally enacted.

Id. Note, however, that one state court has ruled

that a bank may lose its safe harbor protection if a

SAR is filed maliciously. See Bank of Eureka

Springs v. Evans, 109 S.W.3d 672 (Ark. 2003).

In addition to prohibiting institutions from

disclosing SARs to persons involved in a reported

transaction and protecting financial institutions

from civil liability resulting from filing SARs,

FinCEN has issued regulations to prevent SARs

from being disclosed during the course of

litigation:

(e) Confidentiality of reports; limitation of

liability.... [A]ny person subpoenaed or

otherwise requested to disclose a SAR or the

information contained in a SAR, except where

such disclosure is requested by FinCEN or an

appropriate law enforcement or bank

supervisory agency, shall decline to produce

the SAR or to provide any information that

would disclose that a SAR has been prepared

or filed, citing this paragraph (e) and 31

U.S.C. 5318(g)(2), and shall notify FinCEN

of any such request and its response thereto.

31 C.F.R § 103.18(e). The Federal Reserve Board

(12 C.F.R. § 208.62(j) (2006)), the Office of

Thrift Supervision (12 C.F.R. § 563.180(d)(12)

(2005)), and the Office of the Comptroller of the

Currency (12 C.F.R. § 21.11(k)) have issued

essentially identical regulations that apply

specifically to the institutions under their

respective jurisdictions. SARs have been sought

by litigants in a variety of civil cases. In many of

these cases, the government has intervened or

filed briefs to prevent the disclosure of the SARs,

and courts have generally been very supportive of

the government's efforts to protect SARs from

disclosure.

Courts have noted that the disclosure of a

SAR could compromise an ongoing law

enforcement investigation, provide information to

a criminal wishing to evade detection, or reveal

the methods by which banks are able to detect

suspicious activity. See, e.g., Cotton v.

PrivateBank and Trust Co., 235 F. Supp. 2d 809,

815 (N.D. Ill. 2002); Youngblood v. Comm'r,

2000 WL 852449, *11-12 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 6,

2000). Courts have also observed that a bank may

be reluctant to prepare a SAR if it believed that its

cooperation may cause customers to retaliate. See,

e.g., Cotton, 235 F. Supp. 2d at 815. Courts have

also expressed concern that the disclosure of a

SAR could harm the privacy interests of innocent

people whose names may be mentioned. See, e.g.,

id.; Weil v. Long Island Sav. Bank, 195 F. Supp.

2d 383, 388 (E.D.N.Y.2001) ("the production of

SARs by a bank in response to a subpoena would

invariably increase the likelihood that the person

involved in the transaction would discover or be

notified that the SARs had been filed") (internal

citations and quotations omitted); Whitney Nat'l

Bank v. Karam, 306 F. Supp. 2d 678, 680-81

(S.D. Texas 2004).

For example, in Weil v. Long Island Sav.

Bank, 195 F. Supp. 2d 383 (E.D.N.Y. 2001),

borrowers sued the defendant bank in connection

with a purported illegal kickback scheme

involving the CEO. The plaintiffs moved to

compel production of any SAR regarding the

SEPTEMBER 2007 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN 5

CEO that had been filed with the Office of Thrift

Supervision. The court held that 12 C.F.R.

§ 563.180(d)(12) "prohibit[ed] the disclosure of

SARs or their content, even in the context of

discovery in a civil lawsuit, and that the enabling

legislation... [was] specific enough to support that

purpose." The court further found that the statute

created an unqualified discovery and evidentiary

privilege that could not be waived by the

reporting financial institution. Id. at 389.

In Gregory v. Bank One, Indiana, N.A., 200 F.

Supp. 2d 1000 (S.D. Ind. 2002), a bank that was a

defendant in a civil lawsuit sought to disclose its

own filing of a SAR. The plaintiff was a bank

employee who asserted defamation and related

claims arising from accusations of theft. The bank

sought leave of court to submit, under seal for in

camera review, any information that it might have

reported pursuant to 31 U.S.C. § 5318(g)(2) in

support of an affirmative safe harbor immunity

defense. While the court initially granted the

request, upon reconsideration, it vacated its order

and returned the materials produced. The court

explained.

There is no provision in the Act or the Rule

allowing a court-order exception to the

unqualified privilege. [citation omitted] Thus,

the Court is not authorized to order or to

permit Bank One to make any disclosure,

sealed or unsealed, of any information which

is privileged under the Act or the Rule,

whether in the form of a copy of an SAR or

other report.... Quite the opposite: under the

clear, unambiguous terms of the Act and the

Rule, courts have an obligation to prevent

disclosures of privileged information.

Id. at 1003.

Although the regulations issued by the federal

regulators are broader in their prohibitions against

disclosure of the existence or the content of a

SAR than is the statute, the regulations have been

held to be consistent and in harmony with the

enabling statute. In Cotton v. PrivateBank & Trust

Co., 235 F. Supp. 2d 809 (N.D. Ill. 2002), during

the course of civil litigation concerning an estate,

PrivateBank sought the disclosure of certain

SARs from CIBC World Market Corp (CIBC).

PrivateBank argued that disclosure of the SARs

by CIBC would not violate the statutory scheme

because 31 U.S.C. § 5318(g) prohibits disclosure

of a SAR only to any person involved in the

transaction. PrivateBank contended that the

regulations are inconsistent with the statute and,

therefore, unenforceable. The court, citing

Gregory and Weil, disagreed, and held that the

regulations were consistent with the statute and

should be enforced. Id. at 815.

III. Disclosure of supporting documents

Courts have, however, made a distinction

between disclosure of SARs and disclosure of the

supporting documents underlying the SAR. Under

the regulations, the supporting documents

underlying the SAR are not to be filed with the

SAR, but are to be retained by the financial

institution and treated as if they were filed with

the SAR.

(d) Retention of records. A bank shall

maintain a copy of any SAR filed and the

original or business record equivalent of any

supporting documentation for a period of five

years from the date of filing the SAR.

Supporting documentation shall be identified,

and maintained by the bank as such, and shall

be deemed to have been filed with the SAR. A

bank shall make all supporting documentation

available to FinCEN and any appropriate law

enforcement agencies or bank supervisory

agencies upon request.

31 C.F.R. § 103.18(d).

The courts have generally held that the

prohibition against a bank's disclosure of the

existence or contents of a SAR does not apply to

disclosure of any supporting documents. See, e.g.,

Weil v. Long Island Sav. Bank, 195 F. Supp. 2d

383, 389 (E.D.N.Y. 2001). "Nothing in the Act or

regulations prohibits the disclosure of the

underlying factual documents which may cause a

bank to submit a SAR." Cotton, 235 F. Supp. 2d

at 814. Furthermore, those underlying documents

do not become confidential by reason of being

attached or described in a SAR. For example, if a

wire transfer of funds is described in a SAR as a

suspicious activity, the wire transfer transaction

remains subject to discovery. Therefore, the court

in Cotton held that "the better approach prohibits

disclosure of the SAR while making clear that the

underlying transaction such as wire transfers,

checks, deposits, etc., are disclosed as part of the

normal discovery process." Id.

The Cotton court, however, distinguished

between two types of supporting documents.

The first category represents the factual

documents which give rise to suspicious

conduct. These are to be produced in the

6UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN SEPTEMBER 2007

ordinary course of business because they are

business records made in the ordinary course

of business. The second category is

documents representing drafts of SARs or

other work product or privileged

communications that relate to the SAR itself.

These are not to be produced because they

would disclose whether a SAR has been

prepared or filed.

Id. at 815. In United States v. Holihan, 248 F.

Supp. 2d 179 (W.D.N.Y. 2003), the defendant

bank employee was charged with embezzlement.

As part of her defense, the defendant served a

subpoena on the bank for production of complete

personnel files of the bank's investigator and other

bank employees. The bank opposed the request of

personnel files insofar as it would require the

production of any SARs filed against any other

bank employee working at the branch during the

relevant time period. The court, citing Gregory

and Cotton, ordered the disclosure of any

supporting documents relating to a SAR in the

personnel file of any relevant bank employee at

the time of the embezzlement, provided that such

documentation did not disclose either the

existence or contents of a SAR. Id. at 187.

The case of Union Bank of California v.

Superior Court of Alameda County, 130 Cal. App.

4th 378 (2005), further opined on the term

"supporting documentation." Union Bank was

sued by several investors who lost money in a

Ponzi scheme. The fraud victims alleged that

Union Bank was complicit in the operation of the

scheme by allowing the perpetrators to set up a

sham trust account that was used to transfer

millions of dollars to offshore accounts. During

the course of the litigation, the victims sought

permission from the Office of the Comptroller of

the Currency (OCC) to allow Union Bank to

produce certain SARs it had filed during the

relevant time frame. The OCC denied this request.

During discovery, the victims learned that Union

Bank had in place certain internal procedures and

forms to identify, register, and describe what

might constitute suspicious activity, particularly

an internal form (Form 244) which is filled out by

bank personnel to report suspicious activity. The

victims requested the Forms 244 filed within the

bank. The trial court ordered production of all

such Forms 244, whereupon Union Bank filed a

petition seeking a writ of mandate with the

appellate court.

The California Appellate Court noted that "a

draft SAR or internal memorandum prepared as

part of a financial institution's process for

complying with federal reporting requirements is

generated for the specific purpose of fulfilling the

institution's reporting obligation." The court found

that "[t]hese types of documents fall within the

scope of the SAR privilege because they may

reveal the contents of a SAR and disclose whether

a SAR has been prepared or filed." (Citation

omitted). Unlike transactional documents, which

are evidence of suspicious conduct, draft SARs

and other internal memoranda or forms that are

part of the process of filing SARs are created to

report suspicious conduct. Id. at 391. This led the

court to find that the Forms 244 are privileged

documents that should not be disclosed.

A bank's internal procedures may include the

development and use of preliminary reports

subject to various quality control checks

before the bank prepares the final SAR that

will be filed. Revealing these preliminary

reports, the equivalent of draft SAR's would

disclose whether a SAR had been prepared.

Id. at 392. Accordingly, the court held that the

SAR privilege extends to documents prepared by

a bank "for the purpose of investigating or

drafting a possible SAR." Id. at 394.

IV. Disclosure by regulators

The Union Bank case referred to the fact that

the fraud victims initially sought permission from

the OCC to allow Union Bank to produce the

SARs. The OCC's regulations prohibit financial

institutions under its jurisdiction from disclosing

SARs, and require that persons seeking disclosure

of nonpublic documents, such as SARs, submit a

request to the Director of the OCC's Litigation

Division in Washington, D.C. See 12 C.F.R.

§ 4.34(a). The request must provide sufficient

detail to apprise the OCC of the nature of the

litigation, and the request must evidence that "the

information is relevant to the purpose for which it

is sought," that "other evidence reasonably suited

to the requestor's needs is not available from any

other source," and that "the need for the

information outweighs the public interest

considerations in maintaining the confidentiality

of the OCC information and outweighs the burden

on the OCC to produce the information." 12

C.F.R. § 4.33(a)(iii)(A)-(C). Finally, the OCC,

alone, has discretion to deny these requests "based

on its weighing of all appropriate factors

SEPTEMBER 2007 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN 7

including the requestor's fulfilling of the

requirements enumerated in § 4.33." 12 C.F.R.

§ 4.35(a).

Litigants, in some cases, have alleged that the

OCC's denials of their requests for SAR

information were arbitrary and capricious because

they were not analyzed in conjunction with the

regulatory requirements outlined above. One such

complaint arose in the case of Wuliger v. Office of

the Comptroller of Currency, 394 F. Supp. 2d

1009 (N.D. Ohio 2005). In Wuliger, an escrow

agent used investors' money to fund several bank

and brokerage accounts. After the investors

suffered monetary losses, plaintiff was appointed

as Receiver. In conjunction with his role, plaintiff

submitted a request to the OCC for the release of

SARs, all supporting documentation, and all

correspondence, memos, or other documents

pertaining to the investment of these funds. The

OCC responded to the request by outlining the

public policy in favor of maintaining SAR

confidentiality, relying on the regulations

requiring confidentiality, and citing to cases

denying disclosure of SARs in the course of

discovery proceedings. The court ruled that the

OCC acted properly and that its decision could not

be deemed arbitrary or capricious, even though

the OCC did not conduct any analysis as to

whether the plaintiff satisfied the burden

established by its regulations. Id. at 1018.

The Eastern District of Louisiana, however,

reached a contrary result in the case of BizCapital

Bus. & Indus. Dev. Corp. v. OCC, 406 F. Supp.

2d 688 (E.D. La. 2005). BizCapital involved a

SAR disclosure request and OCC response that

were virtually identical to those analyzed in the

Wuliger case. When the OCC denied BizCapital's

request for disclosure, BizCapital filed suit in

federal district court, seeking review of the OCC's

final administrative decision. The district court

granted BizCapital's cross-motion for summary

judgment, rejecting the OCC's argument that it

was absolutely prohibited from revealing SARs to

third parties and determining that the OCC

improperly failed to weigh the factors outlined in

its own regulations prior to denying BizCapital's

request. Id. at 692-93. The court ordered the OCC

to submit any responsive SAR to the court for an

in camera review so that a determination could be

made regarding the appropriate extent of

disclosure. Id. at 697-98. The OCC appealed the

decision on the ground that the district court

should have remanded the case to the OCC for

further consideration, rather than ordering the

disclosure of the SAR. The Fifth Circuit agreed

and remanded the case to the district court.

BizCapital Bus. & Indus. Dev. Corp. v. OCC, 467

F.3d 871 (5th Cir. 2006). This case leaves open

the possibility that, at least in some cases, a civil

litigant may be able to obtain disclosure of a SAR

through a federal regulator during the course of

civil litigation.

V. Disclosure by the government

Section 5318(g)(2)(A)(ii) addresses the

disclosure of SARs by government employees.

(ii) no officer or employee of the Federal

Government or of any State, local, tribal or

territorial government within the

United States, who has any knowledge that

such report was made may disclose to any

person involved in the transaction that the

transaction has been reported, other than as

necessary to fulfill the official duties of such

officer or employee.

While this provision further expresses the notion

that SARs are confidential and should not be

disclosed without authority or good cause, it does

not begin to address the myriad of situations that

prosecutors and investigators encounter during the

course of a criminal investigation and prosecution.

On its face, the restriction is limited to disclosure

of the SAR or information related to the subject of

the SAR, and excludes situations that are

necessary to fulfill the employee's official duties.

This leaves open numerous questions, such as the

following.

• How should prosecutors deal with SARs

during the course of carrying out their

discovery obligations?

• How can investigators and prosecutors use

SARs to support applications for search

warrants and seizure warrants?

• How can investigators and prosecutors share

SARs with other agents during the course of

an investigation?

While there are no statutes or regulations that

directly address these questions, the short answer

is that every effort should be made by

investigators and prosecutors to protect SARs

from disclosure. As mentioned above, release of a

SAR may jeopardize an ongoing investigation,

alert criminals, disclose bank methods to detect

suspicious activity, or alienate customers. Cotton

8UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN SEPTEMBER 2007

v. PrivateBank and Trust Co., 235 F. Supp. 2d

809, 815 (N.D. Ill. 2002).

Financial institutions are prohibited from

disclosing SARs, and the financial regulators

rigorously seek to protect SARs from being

disclosed. It is only fair—and consistent with the

spirit of the SAR program—that law enforcement

does everything within its power to protect SARs

from being disclosed. Therefore, the existence or

contents of a SAR should only be disclosed when

absolutely necessary, and only after there has been

discussion with supervisors in the U.S. Attorneys'

Offices or with the Criminal Division.

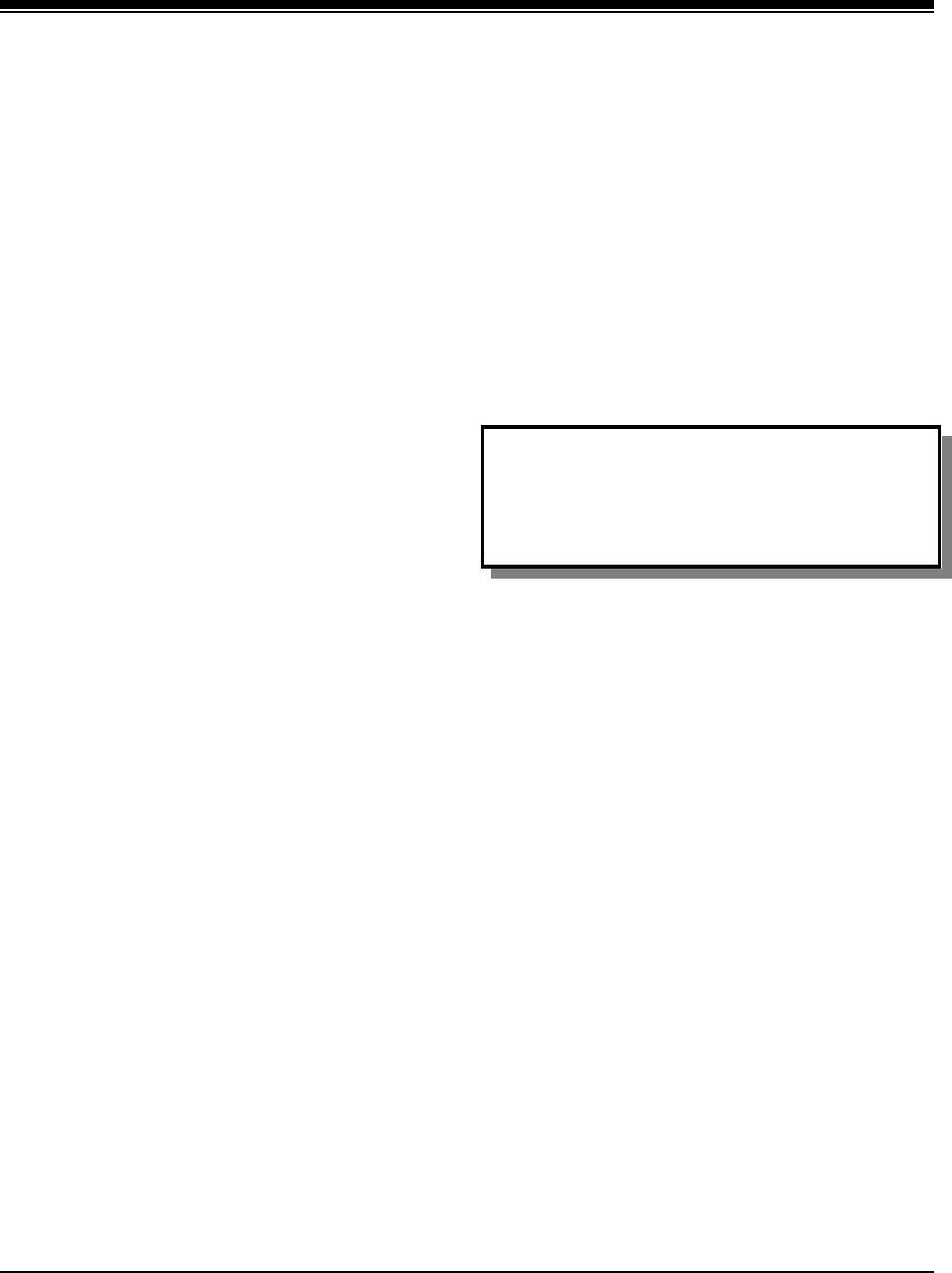

In 2003, the Department of Justice's

(Department) Criminal Division issued guidance

on the "Disclosure of Suspicious Activity

Reports." This guidance is reproduced in Figure 3.

The premise of the guidance is that "[l]aw

enforcement agencies and prosecutors should

consider SARs similar to confidential source

information that, when further investigated, may

produce evidence of criminal activity," and that,

"[c]onsistent with the treatment accorded

confidential source information, the existence of

SARs... should not normally be disclosed to

persons outside of the law enforcement

community." The guidance also notes the

distinction between SARs and the records

underlying the SAR, and states, "[b]ecause the

underlying documents prove the transaction, and

the SAR does not, it should rarely be necessary to

use a SAR in the prosecution's case."

In accordance with this premise, these general

guidelines should be followed.

• SARs should not be referenced in affidavits

for search warrants, Title IIIs, or seizure

warrants. The underlying bank records should

be sufficient to establish the basis for the

search, seizure, or electronic surveillance.

• SARs should not be referenced in motions or

responses to motions.

• SARs should not be referenced in indictments,

informations, or any other charging

documents.

• SARs should not be shown to subjects or

witnesses during the course of interrogations.

• SARs should not be referenced in press

releases.

There are certain situations where a

prosecutor may have an obligation to disclose a

SAR, or more likely, information included within

a SAR, such as the following.

• [The SAR] contains exculpatory or potential

impeachment information that a prosecutor is

constitutionally obligated to disclose.

• [The SAR] is a document, or contains

information, required to be disclosed under

Rule 16 of the Federal Rules of Criminal

Procedure or under the Jencks Act, 18 U.S.C.

§ 3500.

However, even in these situations, it should

not be necessary to disclose the SAR, itself. The

SAR is not the critical information. It is the

information in the SAR that is relevant. Thus, if a

SAR contains potential exculpatory information,

the relevant information can, for example, be

provided to defense counsel in a letter. In any

case, prosecutors should not disclose a SAR,

either in its entirety or in redacted form, before

consulting with their supervisors, the Criminal

Division, and FinCEN's Office of General

Counsel. The disclosure of a SAR in any

particular case can have consequences beyond the

scope of that case.

VI. Sharing of SARs with other

government personnel

The Department encourages the development

of interagency SAR teams to review SARs and

coordinate resulting investigations. There are

restrictions, however, on the sharing of SARs and

SAR information among law enforcement

personnel, pursuant to applicable law and policy,

aimed at protecting the integrity of these sensitive

reports. There are significant privacy issues that

arise from the use and disclosure of SARs.

FinCEN, in its role as the administrator of the

Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), is the central point of

dissemination of BSA information. In this role,

FinCEN is responsible for ensuring that SARs are

used appropriately and in a manner designed to

respect the significant privacy interests that are at

stake. In furtherance of this mission, in June 2004,

FinCEN issued "Re-Dissemination Guidelines for

Bank Secrecy Act Information" which established

the procedures for the re-dissemination of BSA

information by appropriate users of the data.

These Re-Dissemination Guidelines were revised

and reissued in December 2006.

SEPTEMBER 2007 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN 9

The December 2006 Re-Dissemination

Guidelines state that, subject to certain conditions,

a federal, state, or local government agency may

re-disseminate BSA information to another

government agency in the following situations,

without obtaining the approval of FinCEN.

• In support of a financial institution examination,

law enforcement investigation, or prosecution.

• In the conduct of intelligence or

counterintelligence activities, including analysis,

to protect against international terrorism.

The conditions to this rule, in part, include the

following.

• The disclosing federal, state, or local

government agency must obtain a written

acknowledgment of the receiving agency,

reflecting its understanding that further

dissemination of the BSA information is

prohibited without the prior approval of

FinCEN.

• The disclosing federal, state, or local

government agency must ensure that each

item of BSA information shared contains a

specific warning statement which states that

the information cannot be further released

without prior approval from FinCEN.

• The disclosing federal, state, or local

government agency must keep a record of

each disclosure of BSA information.

The December 2006 Re-Dissemination

Guidelines further state that BSA information can

be re-disseminated, without first obtaining the

approval of FinCEN, in the following specific

situations.

• In limited circumstances, a federal prosecutor

may disclose BSA information in the course

of a judicial proceeding without first

obtaining the approval of FinCEN. (See the

discussion of the Department SAR Guidance,

supra.)

• The federal bank supervisory agencies each

have concurrent authority to re-disseminate a

SAR that is filed with FinCEN by a bank or a

banking organization.

• U.S. Customs and Border Protection and U.S.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement have

concurrent authority to re-disseminate a

Currency and Monetary Instrument Report.

As the above is a brief synthesis of the Re-

Dissemination Guidelines, it is imperative that the

guidelines be reviewed prior to the sharing of any

BSA information among law enforcement

personnel. It is important that prosecutors and law

enforcement agents be familiar with, and

understand, these guidelines. The SAR Re-

Dissemination Guidelines are available from

FinCEN, or from the Asset Forfeiture and Money

Laundering Section, or the Fraud Section, of the

Criminal Division.

VII. Conclusion

SARs are one of the most valuable tools to

proactive law enforcement. They allow the

government to identify targets, trends, and related

criminal schemes. They allow law enforcement

agencies to coordinate and prioritize

investigations, thereby allowing the government

to use its limited resources more efficiently. In

addition, they provide a partnership between law

enforcement and the financial services industry.

In order to foster and develop this partnership,

prosecutors and investigators must safeguard

these sensitive tools and protect them from

disclosure. Financial institutions also value

feedback from law enforcement on the utility of

the SARs they file. Financial institutions spend a

considerable amount of resources on systems to

identify and report suspicious activity. They are

obligated to do this under the law, but most

institutions are eager to support law enforcement's

efforts in fighting crime. When they provide

substantial assistance, their efforts should be

recognized. Prosecutors and agents are

encouraged to reach out to the financial

community to explain the government's mission,

discuss recent law enforcement trends and cases,

and encourage the efforts of the financial

community in fighting crime and terrorism.

10 UNITED STATE S ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN SEPTEMBER 2007

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Lester M. Joseph is the Principal Deputy Chief

in the Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering

Section (AFMLS). He has been a Deputy Chief

since the Money Laundering Section was created

in 1991. He became Principal Deputy Chief in

January 2002. Mr. Joseph joined the Department

in 1984 as a Trial Attorney in the Organized

Crime and Racketeering Section. From 1981 to

1984, he was an Assistant State's Attorney in

Cook County (Chicago), Illinois.a

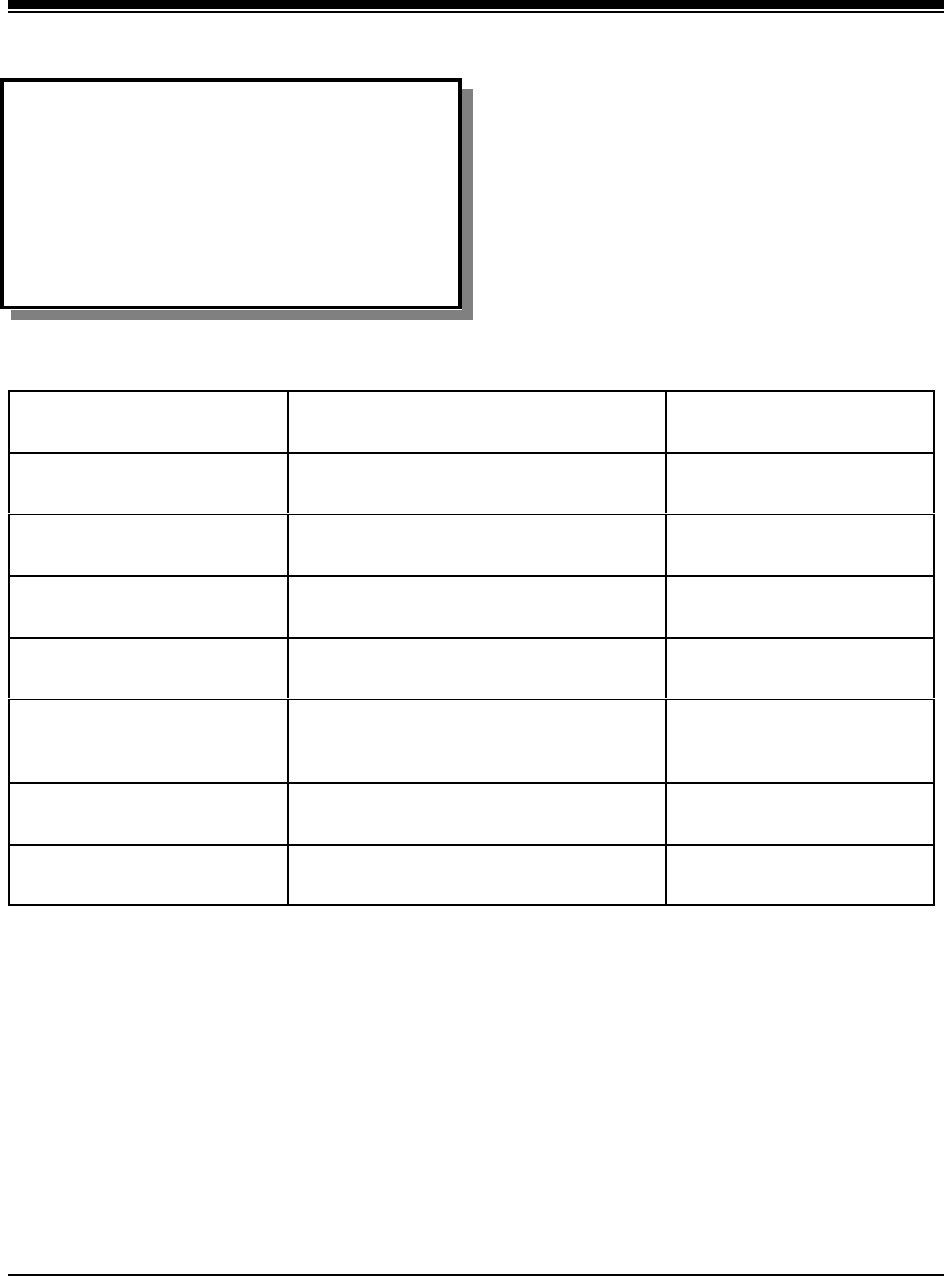

Type of Financial Institution Date of SAR Requirement 31 C.F.R. Cite

Banks April 1, 1996 103.18

Money Service Business January 1, 2002 103.20

Broker-Dealers December 30, 2002 103.19

Casinos March 25, 2003 103.21

Futures Commission

Merchants

May 18, 2004 103.17

Insurance Companies May 3, 2006 103.16

Mutual Funds Nov. 1, 2006 103.15

Figure 1

SEPTEMBER 2007 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN 11

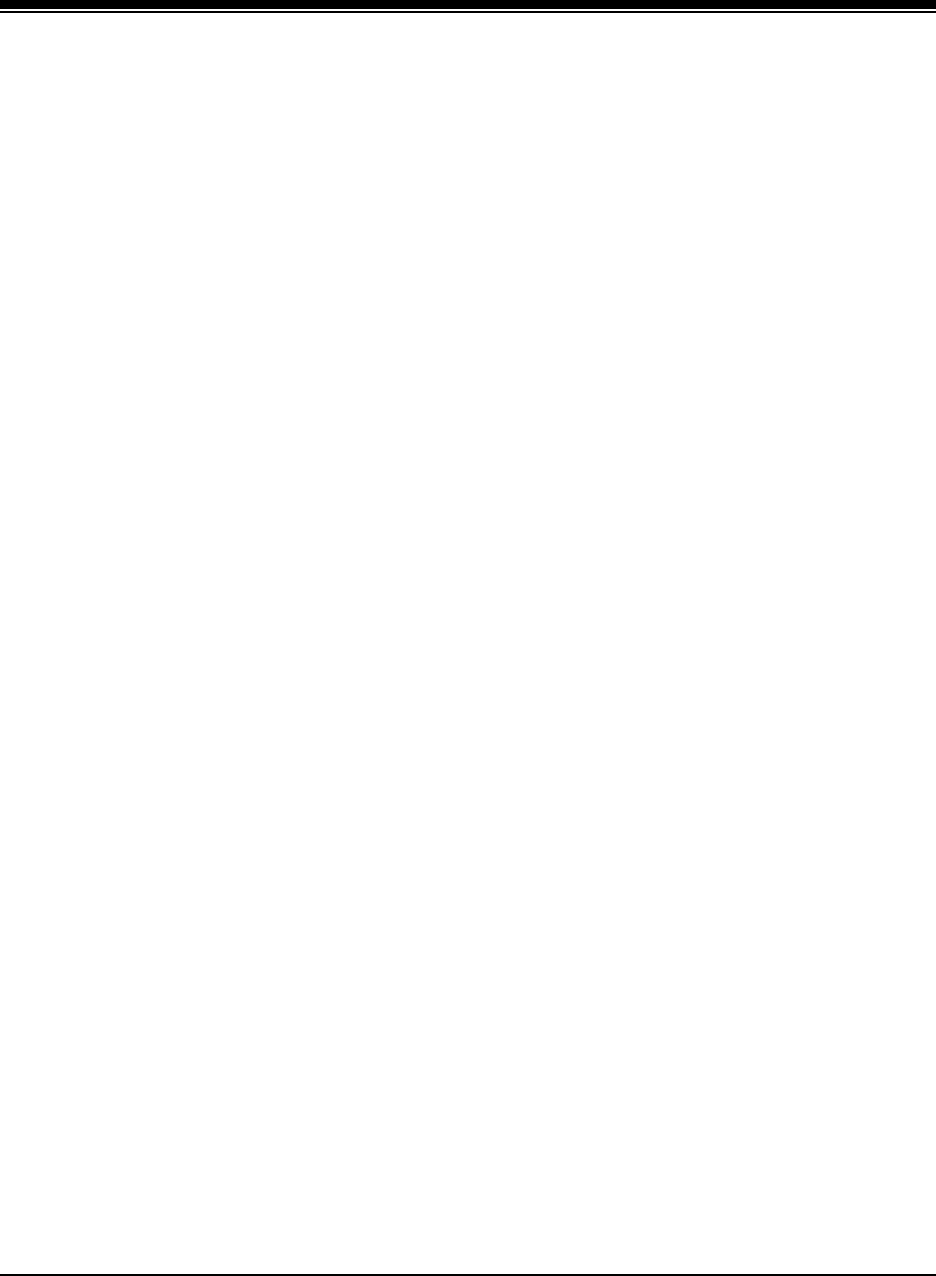

Number of Suspicious Activity Report Filings by Year

Form 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

Depository

Institution

62,388 81,197 96,521 120,505 162,720 203,538 273,823 288,343 381,671 522,655 567,080

Money Services

Business

- - - - - - 5,723 209,512 296,284 383,567 496,400

Casinos and Card

Clubs

85 45 557 436 464 1,377 1,827 5,095 5,754 6,072 7,285

Securities &

Futures Industries

- - - - - - - 4,267 5,705 6,936 8,129

Subtotal

62,473 81,242 97,078 120,941 163,184 204,915 281,373 507,217 689,414 919,230 1,078,894

Total 4,205,961

Figure 2

12 United States Attorneys' Bulletin

Disclosure of Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs)

From: Joshua R. Hochberg

Chief, Fraud Section

Criminal Division

U.S. Department of Justice

July 8, 2003

Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) provide valuable information that can accelerate the

investigation and development of cases for prosecution and provide significant leads for

investigations and intelligence. The routine or unnecessary disclosure of SARs or even of

their existence undermines the confidentiality surrounding their filing.

Certain financial institutions operating in the United States are required to file reports of known

or suspected criminal conduct that takes place at or was perpetrated against the financial

institutions. These reports, known as Suspicious Activity Reports or SARs, are filed with the

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a bureau of the United States Department of

the Treasury. SARs are made available to the law enforcement community for use in

investigations, prosecutions and related law enforcement activities.

The SAR system was designed to assist the law enforcement community by requiring financial

institutions to report transactions that are indicative of possible criminal activity. The required

threshold for filing is easily triggered, simply by suspicion, not proof, of criminal activity. The

information contained in SARs constitutes raw allegations of the most sensitive kind, precisely

because the reported suspicions are unsubstantiated and unproved.

Because financial institutions file SARs with the expectation that they will be accorded sensitive

treatment, unnecessary disclosure of SARs could frustrate that expectation and have a chilling

effect on both the quantity and the quality of future SAR filings. Moreover, SARs may contain

information concerning the methods by which an institution learned of or uncovered suspicious

activity, possibly allowing other potential wrongdoers to take action to avoid those methods of

detection. Law enforcement agencies and prosecutors should consider SARs similar to

confidential source information that, when further investigated, may produce evidence of

criminal activity.

Consistent with the treatment accorded confidential source information, the existence of SARs

relating to conduct being investigated, as well as the content of SARs, should not normally be

disclosed to persons outside the law enforcement community. Disclosure of a SAR should be

distinguished from disclosure of the records constituting the transactions discussed in a SAR,

such as a wire transfer record, which can be treated as an ordinary piece of evidence. Because

the underlying documents prove the transaction, and the SAR does not, it should rarely be

necessary to use a SAR in the prosecution's case.

Figure 3

SEPTEMBER 2007 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN 13

Special Note—Disclosure of SARs and SAR Information to Subjects

Given the nature of the information contained in SARs and the purposes for which such

information is collected, there are strict statutory restrictions governing disclosures of SARs, or

the fact that SARs have been filed, when these disclosures are made to persons involved in the

reported transactions. These provisions recognize that there will be instances in which the

disclosure of SARs or their contents is unavoidable due to constitutional or statutory discovery

obligations placed on prosecutors.

As amended by the USA PATRIOT ACT (Pub. L. 107-56), 31 U.S.C. 53 18(g) states in relevant

part:

(2) NOTIFICATION PROHIBITED -

(A) IN GENERAL --If a financial institution or any director, officer, employee, or agent of

any financial institution, voluntarily or pursuant to this section or any other authority, reports

a suspicious transaction to a government agency

(i) the financial institution, director, officer, employee, or agent may not notify any person

involved in the transaction that the transaction has been reported; and

(ii) no officer or employee of the Federal Government or of any State, local, tribal, or

territorial government within the United States, who has any knowledge that such report was

made may disclose to any person involved in the transaction that the transaction has been

reported, other than as necessary to fulfill the official duties of such officer or employee.

Under 31 U.S.C. 53l8(g)(2), no government official may disclose a SAR to a person involved in

the transaction "other than as necessary to fulfill the official duties of such officer or employee."

For example. it may be necessary for a prosecutor to disclose a SAR in situations in which the

SAR:

• contains exculpatory or potential impeachment information that a prosecutor is

constitutionally obligated to disclose; or

• is a document or contains information required to be disclosed under Fed. R. Crim. P. 16

or the Jencks Act, 18 U.S.C. 3500.

In these and other instances in which a prosecutor believes that disclosure of a SAR to the

defense may be compelled by constitutional, statutory or regulatory authority, the prosecutor

should consult with supervisory personnel in the office to consider whether the SAR or the

material included within the report must be disclosed to the defense, or whether it may be

withheld, redacted, limited by protective order or otherwise protected from disclosure.

Attorneys in the Criminal Division's Fraud Section, John Arterberry, Barry Goldman and Jack

Patrick (202-514-0890), and Asset Forfeiture and Money Laundering Section, Lester Joseph

(202-616-0593), are available for consultation on SAR disclosure issues. Because disclosure of a

SAR may affect other investigations or cases and because FinCEN is charged with responsibility

for enforcing the SAR laws and regulations, FinCEN's Office of Chief Counsel, 703-905-3590,

should be given notice if an office decides to disclose a SAR.

Figure 3 Cont'd

14 UNITED STATE S ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN SEPTEMBER 2007

Money Laundering Trends

Emery Kobor

Policy Advisor

Office of Terrorist Financing and Financial

Crimes

Department of the Treasury

I. Introduction

Combating money laundering is a massive

and evolving challenge which requires a clear and

thorough understanding of the various trends and

techniques being used by criminals to launder

their illicit funds. These trends range from well-

established techniques for integrating dirty money

into the financial system to modern innovations

that exploit global payment networks, as well as

the Internet. New and innovative methods for

electronic cross-border funds transfer are

emerging globally. These new payment tools

include extensions of established payment

systems, and new payment methods that are

substantially different from traditional

transactions. New payment methods raise

concerns about money laundering and terrorist

financing because criminals can adjust quickly to

exploit new opportunities that often allow

anonymous high value transactions with little or

no paper trail or legal accountability. This article

is a digest of thirteen different methodologies

which were identified in the 2005 Money

Laundering Threat Assessment as being used by

criminals to launder money in the United States,

available at http://www.treas.gov/offices/

enforcement/pdf/mlta.pdf.

II. Banks and other depository financial

institutions

In the United States, only banks and other

depository financial institutions are allowed to

hold financial deposits and provide direct access

to those deposits through the use of paper checks

and various bank-to-bank electronic payment

networks. Although Money Services Businesses

(MSBs) offer an alternative to banks for many

financial services, they have to use a depository

financial institution to hold their deposits, clear

checks, and settle transactions.

Once illicit funds are in a bank, the money

can be transferred quickly from account to

account, leading to a tangled web of transactions

that make it difficult to trace the path or identify

the ultimate owner of the money. Criminals open

both consumer and business accounts to move

illicit cash into the banking system. One technique

to avoid a Currency Transaction Report (CTR)

being filed is to use "smurfs,"—students,

travelers, or other accomplices—to open accounts

in a number of banks, then "structure" cash

deposits into the accounts by keeping each deposit

below the $10,000 CTR threshold. The money

launderer will periodically draw down the

accounts, transferring funds to other accounts or

money laundering vehicles, domestically and

offshore.

Bank accounts opened in the name of a

business or other legal entity can be useful to

disguise the beneficial owner of the account and

the true nature of the funds that move through the

account. Retail businesses that ring up cash

transactions and make nightly deposits can be

used as a front to disguise illicit cash added to the

day's deposit. Bank accounts held by shell

companies and trusts often do not require the

disclosure of beneficial ownership and can mask

illicit money movement as trade or investment

transactions.

III. Correspondent banking

Despite rapid developments in banking

technology, domestic bank payment networks

around the world generally do not connect with

one another. To move money across borders, a

U.S. bank often has to hold an account with a

bank overseas, a relationship known as

correspondent banking. When a U.S. bank

customer wants to send a cross-border wire

transfer, the bank transfers funds from the

correspondent account it holds in the recipient

country.

Correspondent accounts and "payable

through" accounts create opportunities to use a

U.S. or foreign bank without the bank always

knowing the true payment originator. A "payable

through" account at a U.S. bank involves a foreign

bank holding a checking account at the U.S.

institution. The foreign bank can issue checks to

its customers, allowing them to make payments

from the U.S. account. A variation on the

"payable through" account is "nesting," in which

SEPTEMBER 2007 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN 15

foreign banks open correspondent accounts at

U.S. banks, but then solicit other foreign banks to

use the account. This results in an exponential

increase in the number of individuals with access

to a single account at a U.S. banking institution.

As cross-border wire transfers come under

increased scrutiny and regulation, criminals are

using paper checks, money orders, and cashier's

checks, as an effective alternative. These more

traditional payment instruments take longer to

clear when traveling outside the United States, but

often receive less scrutiny.

Money launderers can transfer large dollar

amounts by writing a number of checks or buying

a number of money orders at various U.S.

locations, with each payment below the CTR

reporting threshold. The dollar-denominated

payments are mailed or transported to

accomplices overseas who deposit the checks and

money orders in foreign bank accounts. Because

these are dollar-denominated payments, the

foreign banks that receive them have to send them

back to the United States for deposit in their U.S.

correspondent accounts. Some banks handle as

many as five to seven million checks a day.

Processing is done as efficiently as possible,

making it difficult to aggregate related payments

or scrutinize individual payments for evidence of

money laundering.

IV. Money services businesses

MSBs provide an alternative to the banking

system, offering a full range of financial products

and services without the same level of regulation

and supervision imposed on banks and other

depository financial institutions. Under the Bank

Secrecy Act (BSA), 12 U.S.C. §§ 1251-1259,

MSBs include the following.

• Currency exchangers.

• Check cashers.

• Issuers of traveler's checks, money orders, or

stored value.

• Sellers or redeemers of traveler's checks,

money orders, or stored value.

• Money transmitters.

Unlike banks, which are obligated to verify

customer identification at account opening, MSBs

do not hold customer accounts and are currently

obligated, under federal law, to verify and record

customer identification only when selling $3,000

or more of money orders or travelers' checks, or

conducting a money transfer of $3,000 or more.

Most MSBs are required to report suspicious

activity, however, excluded from that requirement

are check cashers and sellers and redeemers of

stored value.

Many MSBs, including the vast majority of

money transmitters in the United States, operate

through a system of agents. Agents are not

required to register with the Financial Crimes

Enforcement Network (FinCEN), but are required

to establish anti-money laundering (AML)

programs and to comply with certain record

keeping and reporting requirements.

A. Currency exchangers

Currency exchangers, also referred to as

currency dealers, money exchangers, casas de

cambio, and bureaux de changes, exchange bank

notes of one country for that of another. Less than

ten states currently regulate this activity, which

makes it the least regulated MSB category.

Casas de cambio are currency exchange

houses specializing in Latin American currencies.

In the United States, more than 1,000 casas de

cambio are located along the border from

California to Texas. Some casas de cambio exist

primarily for money laundering. They take in

illicit cash from many clients and then deposit the

money under the name of the exchange house.

Seized documents in raids conducted by the

Venezuelan Guardia Nacional in the state of

Tachiria revealed that a number of casas de

cambio were laundering drug proceeds from the

United States and routing them through Venezuela

to Colombia to avoid the relatively high tariff on

U.S. currency in Colombia. Many of the casas de

cambio involved in the money laundering process

have access to U.S. dollar checking accounts

through correspondent accounts held by major

banks in Venezuela.

B. Check cashers

Money launderers use check-cashing

businesses to cash checks that were written to

small businesses, but which the launderer

purchased with illicit cash. Small businesses

benefit by receiving immediate cash, avoiding

fees, passing on the risk of bad checks, and

potentially evading income taxes. Money

launderers sometimes purchase check-cashing

businesses outright so that checks can be

deposited directly into the launderer's bank

account. The lack of record keeping or suspicious

16 UNITED STATE S ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN SEPTEMBER 2007

activity report (SAR) filing requirements may

hinder law enforcement attempts to trace illicit

proceeds through this channel.

C. Money orders

Money orders are attractive to money

launderers because they can be issued in large

dollar denominations, are less bulky than cash,

and are issued anonymously for amounts under

$3,000. A common money laundering technique is

to structure multiple money order purchases just

under the $3,000 customer-identification

threshold. It is estimated that more than 830

million money orders, worth more than $100

billion, are issued annually, with 80% issued by

the U.S. Postal Service (USPS), Western Union,

and MoneyGram International. The remainder are

issued by small regional companies.

Money order issuers, other than USPS, rely

largely on licensed agents, rather than employees.

While the parent firm is responsible for activity

across their agent network, it is not required to

review individual SARs, and some firms

specifically discourage their agents from

submitting SARs to the parent firm. Western

Union and MoneyGram agents issue more than 50

percent of all money orders in the United States,

yet filed only 1 percent of the SARs from October

1, 2002 through December 31, 2004 that involved

money orders and money laundering. During the

same period USPS, which issues approximately

one-quarter of all money orders in the

United States, filed 93 percent of the SARs related

to money laundering via money orders.

D. Stored value

Stored value, or prepaid cards, operate within

either an "open" or "closed" system. Open system

cards can be used to make purchases from

merchants or to get cash at ATMs that connect to

the global payment networks, specifically those

operated by Visa and MasterCard. Open system

card programs, although issued through banks and

other depository institutions, generally do not

require a bank account or face-to-face verification

of the cardholder's identity. Funds can be prepaid

by one person, with someone else in another

country accessing the cash via ATM. Open system

prepaid cards typically can have additional funds

added on an ongoing basis. There are no

regulatory guidelines that address customer

identification, record keeping, or reporting

requirements, regarding open system prepaid card

accounts.

Closed system cards can only be used to buy

goods or services from the merchant or service

provider issuing the card. Examples of closed

system cards include store-specific retail gift cards

and mass transit system cards. These cards may be

limited to the initial value posted to the card or

may allow the card holder to add value.

The target markets for prepaid cards include

teenagers, people without bank accounts, adults

unable to qualify for a credit card, and immigrants

sending cash to family outside the United States.

Depending on the safeguards employed by the

card-issuing bank and its support network, open

system prepaid cards may provide an anonymous

way to store, transport, and access, illicit cash

globally. Closed system cards, primarily store gift

cards, present more limited opportunities and a

correspondingly lower risk as a means to move

monetary value out of the country. Nevertheless,

federal law enforcement agencies report both

categories of stored value cards are used as

alternatives to smuggling physical cash.

E. Money transmitters

The volume and accessibility of money

transmitters makes them attractive vehicles to

money launderers. Western Union runs the largest

nonbank money transmitter network, with more

than 245,000 agent locations in 195 countries and

territories.

Money transmitters are obligated to verify and

record customer identification only when sending

a wire of more than $3,000. To evade that

threshold, customers can divide up their funds

transfers among several wires and several

different money transmitters.

Online payment services, including dealers in

digital precious metals, are another option for

cross-border funds transfers. These intermediaries

operate via the Internet and facilitate funds

transfers for individuals and businesses by using a

variety of payment methods. The forms of

payment a service provider accepts and uses to

pay out to recipients varies by service provider.

Those willing to accept and pay out using

anonymous forms of payment (cash, money

orders, nonbank wires, and some prepaid cards)

create a potential money laundering threat.

U.S. citizens can access payment services

online that are based outside of the United States

and transfer funds either electronically or by mail.

Some online payment services exist to facilitate

transactions for online gambling and adult content

SEPTEMBER 2007 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN 17

that U.S.-based money transmitters typically will

not service. Online payment services that offer

immediate final settlement with no recourse are

often used for illegal transactions and are popular

with fraudulent investment schemes.

V. Casinos

As high-volume cash businesses, casinos are

susceptible to money laundering, as well as many

other financial crimes, and were the first nonbank

financial institutions required to develop AML

compliance programs. In addition to gaming,

casinos offer a variety of financial services

including credit, funds transfers, check cashing,

and currency exchange.

Tribal casinos are moving rapidly from

relative obscurity within the U.S. casino industry

to a position of prominence. Collectively, tribal

casinos took in $18.5 billion in revenue in

2004—twice the amount generated by Nevada

casinos. There are 567 federally recognized

American Indian tribes (half are in Alaska), with

gaming facilities in twenty-eight states.

Money laundering schemes involving casinos

usually start with the purchase of casino chips

using illicit cash. The chips then can be used in

the following ways.

• Cashed in for a casino check or wire transfer

for deposit into a bank account.

• Used as a form of currency for goods and

services, particularly illegal narcotics, so that

others ultimately cash in the chips.

• Used for gambling in the hope of generating

certifiable winnings.

While criminals will structure transactions at

banks and MSBs to avoid transaction records or

reports that draw attention to them, they use

casinos for the opposite purpose. Having a CTR

filed on a casino payout has the effect of making

the money appear legitimate. Criminals also use

casinos to launder counterfeit money, as well as

large currency notes that would be conspicuous

and difficult to use elsewhere, and which may be

marked by undercover law enforcement officers.

VI. Bulk cash smuggling

Increasingly effective AML policies and

procedures at U.S. financial institutions may be

responsible for money launderers moving illicit

cash out of the country to jurisdictions with lax or

complicit financial institutions, or to fund criminal

enterprises. Smugglers conceal cash in aircraft,

boats, vehicles, commercial shipments, express

packages, on their person, and in their luggage.

Cash associated with illicit narcotics typically

flows out of the United States across the

southwest border into Mexico, retracing the route

that illegal drugs follow when entering the

United States. The cash may stay in Mexico,

continue on to a number of other countries, or

head back into the United States as a deposit by a

bank or casa de cambio. Illicit funds leaving the

United States also flow into Canada, which also is

a source of illegal narcotics.

Cash can be smuggled out of the

United States through the 317 official land, sea,

and air ports of entry, and any number of

unofficial routes along the Canadian and Mexican

borders. The United States shares a 3,987 mile

border with Canada and a 1,933 mile border with

Mexico. In addition to individuals carrying cash

over the border, or hiding it in vehicles, it can be

hidden in any of the thousands of shipping

containers involved in commercial trade with the

top two U.S. trading partners (Mexico and

Canada).

The extent to which cash smuggled out of the

United States is derived from criminal activity

other than the sale of illegal drugs is not known.

Other cash-intensive sources of illicit income

include alien smuggling, bribery, contraband

smuggling, extortion, fraud, illegal gambling,

kidnapping, prostitution, and tax evasion.

VII. Shell companies and trusts

The United Nations noted, in a 1998 report,

that "the principal forms of abuse of secrecy have

shifted from individual bank accounts to corporate

bank accounts and then to trust and other

corporate forms…." OFFICE FOR DRUG CONTROL

AND CRIME PREVENTION, UNITED NATIONS,

FINANCIAL HAVENS BANKING SECRECY AND

MONEY LAUNDERING 57 (1998). Legal entities,

such as shell companies and trusts, can use bearer

shares and nominee shareholders and directors to

hide ownership and mask financial transactions.

Legal jurisdictions, whether states within the

United States or entities elsewhere, that offer strict

secrecy laws, lax regulatory and supervisory

regimes, and corporate registries that safeguard

anonymity, are obvious targets for money

launderers. A handful of U.S. states offer

18 UNITED STATE S ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN SEPTEMBER 2007

company registrations with secrecy

features—such as minimal information

requirements and limited oversight—that rival

those offered by offshore financial centers.

Delaware, Nevada, and Wyoming, are often cited

as the most accommodating jurisdictions in the

United States for the organization of these legal

entities.

Intermediaries, called nominee incorporation

services, establish U.S. shell companies and bank

accounts on behalf of foreign clients. By hiring a

firm to serve as an intermediary, the true owners

of a shell company, or other legal entity, may

avoid disclosing their identities in state corporate

filings and in the documentation used to open

corporate bank accounts.

Several options are available in the formation

of legal entities that allow beneficial owners even

greater anonymity. Bearer shares are negotiable

instruments that accord ownership of a company

to the person who possesses the share certificate.

Bearer share certificates do not contain the name

of the shareholder and are not registered, with the

possible exception of their serial numbers.

Accordingly, these shares provide for a high level

of anonymity and are easily negotiable.

Nominee shareholders can be used in

privately-held companies as stand-ins to shield

beneficial ownership information. Where nominee

shareholders are allowed, the usefulness of the

shareholder register is undermined because the

shareholder of record may not be the ultimate

beneficial owner. Similarly, nominee directors

and companies serving as directors of a legal

entity may conceal who really controls the

company.

Trusts separate legal ownership from

beneficial ownership and are useful when assets

are given to minors or individuals who are

incapacitated. The trust creator transfers legal

ownership of the assets to a trustee, which can be

an individual or a corporation. The trustee

manages the assets on behalf of the beneficiary,

based on the terms of the trust deed. Although

trusts have many legitimate applications, they can

also be misused. Trusts enjoy a greater degree of

privacy and autonomy than other corporate

vehicles, as virtually all jurisdictions recognizing

trusts do not require registration or central

registries and there are few authorities charged

with overseeing trusts. In most jurisdictions, no

disclosure of the identity of the beneficiary or the

creator of the trust is made to authorities.

VIII. Trade-based money laundering

Money launderers use fraudulent foreign trade

transactions as a way to provide cover for, and

legitimize, funds transfers using illicit proceeds.

Trade-based money laundering encompasses a

variety of schemes that involve over- and under-

invoicing, double invoicing, and misclassification

of the goods shipped.

The most common method of trade-based

money laundering in the Western Hemisphere is

the Black Market Peso Exchange (BMPE), which

is responsible for moving an estimated $5 billion

worth of drug proceeds per year from the

United States to Colombia. The scheme allows

drug traffickers to exchange their illicit dollars in

the United States for clean pesos in Colombia,

without physically moving funds from one

country to the other. See David Marshall Nissman,

The Columbia Black Market Peso Exchange,

UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS' BULLETIN, June

1999, at 31.

Money brokers act as intermediaries between

the drug traffickers in the United States who hold

dollars, but want pesos, and Colombian

businessmen who hold pesos, but want dollars to

purchase goods for import. The money brokers

buy the illicit dollars in the United States and

enlist smurfs to buy money orders or deposit the

cash in U.S. bank accounts. The money is then

used to purchase U.S. products which are

exported to Colombia and elsewhere. The

Colombian importers complete the money

laundering cycle by paying the money broker for

the U.S. merchandise with pesos, which are

transferred to the drug dealers.

Access to U.S. dollars is regulated by the

Colombian government. Before pesos can be

exchanged for dollars, the importer has to