Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel

Volume 20 Number 3 Article 4

9-2019

Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints

Joshua M. Sears

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re

Part of the Mormon Studies Commons

BYU ScholarsArchive Citation BYU ScholarsArchive Citation

Sears, Joshua M. "Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints."

Religious Educator: Perspectives

on the Restored Gospel

20, no. 3 (2019): 27-57. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol20/iss3/4

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel by an authorized editor of BYU

ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Latter-day Saints can benefit from combining the strengths of the King James translation with the strengths of

modern translations and from combining the strengths of the study aids in the official Latter-day Saint

editions of the Bible with the strengths of the study aids in academic study Bibles.

RE · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 · 27–57 27

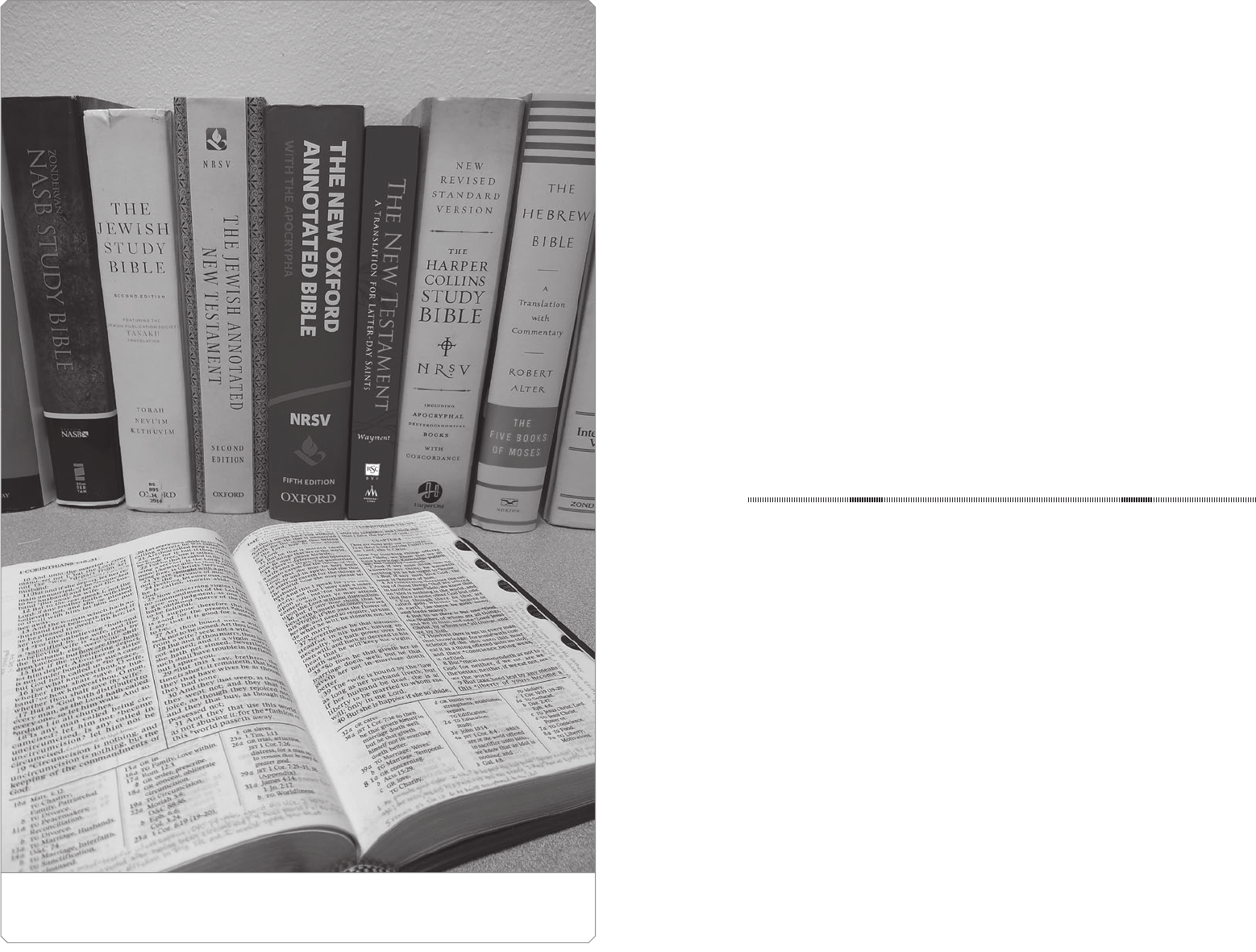

Courtesy of Josh Sears.

Study Bibles:

An Introduction for

Latter-day Saints

joshua m. sears

Joshua M. Sears ([email protected]) is an assistant professor of ancient scripture at

Brigham Young University.

Behold, a man of Ethiopia, an eunuch of great authority under Candace queen

of the Ethiopians, . . . [was] sitting in his chariot . . . And Philip ran thither

to him, and heard him read the prophet Esaias, and said, Understandest thou

what thou readest? And he said, How can I, except some man should guide me?

—King James Version, Acts 8:27–28, 30–31

e word Ethiopian, in Luke’s day, referred to anyone with dark or black skin.

A eunuch is a castrated male who serves the queen in some ancient societies. . . .

Candace is a title and not the specic name of an Ethiopian queen. . . . [e]

quotation [is] om Isaiah 53:7–8.

—e New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints—A Study Bible

L

atter-day Saints revere the Bible as “the bedrock of all Christianity” and

are instructed to feast upon its teachings regularly.

Although Latter-

day Saints appreciate so much about the Bible, many struggle with some of

its language and its deeply contextual messages. Fortunately, special editions

known as study Bibles can help make the Old and New Testaments much

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 29

28

clearer. ere are many kinds of study Bibles, but for present purposes we will

dene them as an edition of the Bible featuring a modern English translation

and sophisticated, context-focused study aids—including book introduc-

tions, footnotes, and appendixes—that provide textual, historical, cultural,

literary, linguistic, and theological insights about the biblical text.

Because

many Latter-day Saints may not be familiar with these kinds of Bibles, in this

article I will describe what study Bibles are and the benets they oer readers.

I will also give suggestions for choosing a study Bible and discuss how these

Bibles might be used to supplement one’s study of the ocial Bible editions

published by e Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Latter-day

revelation instructs that we utilize the “best books” to “seek learning, even

by study and also by faith” (Doctrine and Covenants :), and I recom-

mend study Bibles as among the “best” resources available to help us study

the scriptures.

The Development of Study Bibles

e idea of adding explanatory notes or commentary to accompany biblical

texts has a long history. Scribes since ancient times have added clarications

to the margins or in between the lines of the handwritten biblical texts they

were copying. ey would also add background information to the beginning

or end of a text, such as in the case of the subscripts that appear at the end

of Paul’s epistles, which provide information about the place of composition

and the person who helped Paul write or deliver the letter.

Over time, manuscripts and books that combined biblical text with later

commentary became more sophisticated. In Venetian printer Daniel

Bomberg published the rst Rabbinic Bible (Mikra’ot Gedolot), which was

prepared by Jacob ben Hayyim. It functions in many ways like a modern

study Bible: on any given page, several verses from the Hebrew Bible (Old

Testament) are presented, along with a parallel Aramaic translation called

the Targum, textual notes known as the Masorah, and two running commen-

taries from notable medieval Jewish interpreters Rashi and Ibn Ezra.

is

presentation allowed Jewish readers to study their scriptures with the added

richness of their extensive interpretive traditions.

For Christians, the Geneva Bible of is oen considered the ances-

tor of modern study Bibles. is Bible—used by Shakespeare and carried

by the Pilgrims aboard the Mayower—contains book introductions, chap-

ter summaries, maps, illustrations, cross-references, and marginal notes that

provide alternative translations or explain the meaning of the biblical text.

e strengths of the translation and the helpfulness of the study aids made the

Geneva Bible enormously popular, although in the heated religious climate

of the late sixteenth century, some did not appreciate the theological and

political messages that the marginal notes promoted.

To avoid any poten-

tial controversy, the translators assigned to work on the King James Version

(KJV) a half century later were explicitly instructed to include “no marginal

notes at all . . . [except] for the explanation of the Hebrew or Greek.”

Despite the popularity of the commentary-free King James Version, study

aids proved too helpful to leave out forever. In the runaway success of

This page from the 1538 edition of the Rabbinic Bible surrounds Isaiah 1:12–23a with notes and

commentary.

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 31

30

the Scoeld Reference Bible demonstrated how well the right kind of study

Bible could sell in the modern age—and how much its theological interpreta-

tions could inuence readers.

e study aids in modern study Bibles, which have increased in sophisti-

cation over time, are designed to meet a diversity of needs. Some study Bibles

interpret the text from the point of view of a specic religion, such as e

Catholic Study Bible

or e Jewish Study Bible,

which draw upon centu-

ries of interpretive history from their respective faith traditions. Other study

Bibles, such as e HarperCollins Study Bible

or e New Oxford Annotated

Bible,

aim to be ecumenical; they explain biblical texts in their original con-

text without favoring one modern theological system over another.

In addition to varying in religious orientation, study Bibles dier in

whether their notes emphasize contextual interpretation or personal applica-

tion. At the rst end of the spectrum, an edition like the Cultural Backgrounds

Study Bible focuses on “background—the missing pieces of information that

the biblical writers did not need to state explicitly because their original audi-

ences intuitively knew them.”

e notes are full of comparisons between

Israelite culture and that of Babylon, Ugarit, and Egypt, and color pictures

and maps help establish historical context. As another example, the online

NET (New English Translation) Bible (https://netbible.org/) contains over

, notes that focus on linguistic and textual information.

At the other

end of the spectrum, editions like the Starting Point Study Bible

or the

Christian Basics Bible

are light on the verse-by-verse context but instead use

sidebar comments to orient new believers in their life of faith.

Bibles in the

middle of the spectrum, such as the Life Application Study Bible, include a

great amount of contextual detail mixed with modern application.

Features in Study Bibles

Study Bibles oen share some common features, especially if they focus on

explaining original context. Instead of using older translations such as the

King James Version, most study Bibles favor newer versions, which use con-

temporary language, take advantage of more recent textual evidence and

biblical scholarship, and in some cases are translated more accurately (more

on this below).

Because these insights are incorporated directly into mod-

ern translations, study Bibles using these translations have more room in the

footnotes to dedicate to other subjects.

The 1560 Geneva Bible is supplemented with chapter summaries, cross-references, alternative word

meanings, and short commentaries.

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 33

32

Aer the translation itself, the most prominent feature of study Bibles

is the footnotes, which are oen copious. At the discretion of the scholar(s)

assigned to annotate any particular section of the biblical text, these notes may

provide historical background, cultural context, and textual variants; point

out literary features such as narrative structures, poetic forms, and rhetori-

cal devices; or provide such basic services as cross-references or explanations

of dicult passages. Most study Bibles are very careful about distinguishing

between the ancient scriptural text and the modern scholarly additions. For

example, the NIV Zondervan Study Bible

prints notes in a dierent font

and with a pale green background. Other Bibles use simpler methods, such as

printing the footnotes in smaller type.

As an example of these notes and the value they can provide, consider

the narrative in Isaiah chapter . While this chapter is well-known because

of the Immanuel prophecy in verse (“a virgin shall conceive”), it is di-

cult to understand as a whole because in this chapter Isaiah also describes

so many contemporary individuals, nations, and events—including Ahaz,

Jotham, Judah, Rezin, Syria, Pekah, Ephraim, and Assyria. Without some

background, reading this chapter today is akin to reading a story about World

War II without knowing the identications of France, Hitler, America, Stalin,

Roosevelt, or Japan; they’re all just names. But this is where study Bibles can

come to the rescue. For example, the Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible con-

tains this information immediately below the text of Isaiah :

Rezin . . . was an Aramean (Syrian) King who was dethroned when his nation was

incorporated into the Assyrian Empire in BC. He had been paying tribute to

Assyria for some time. . . . In order to forestall incorporation, Rezin joined Pekah,

son of Remaliah (Is. :–; :) and king of Israel from c. – BC, to oppose

Assyria. Rezin, Pekah and Hoshea (Pekah’s son and successor aer Pekah was killed

by the Assyrians), pressured Jotham, king of Judah (c. – BC), to join their

anti-Assyrian coalition ( Kin. :, ), but Jotham refused. To present a united

front against their common enemy, Aram/Syria and Israel (called “Ephraim,” the

name of its major tribe, in Is. :, ) united against Judah, now led by Ahaz (–

BC), to force their cooperation. is attack by Aram/Syria and Israel against

Judah is called the Syro-Ephraimite War.

In very little space, this note helps readers get a basic sense of what is

going on; they may then return to the biblical text with a much greater com-

prehension of what Isaiah is saying.

Other common aids in study Bibles include maps, tables, and illustra-

tions, which may appear on a page where they are most relevant or might be

Job 24:18b–26:10a in The New Oxford Annotated Bible, a modern study Bible published by an academic

press.

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 35

34

collected together in an appendix. Introductory essays at the beginning of

each book of the Bible provide some basic information regarding that book’s

subject matter, literary organization, genre(s), historical and theological sig-

nicance, and interpretive diculties.

How to Choose a Study Bible

e study Bible industry is extensive, and dozens of options are currently on

the market.

I have two recommendations for Latter-day Saints.

First, choose a study Bible prepared by recognized scholars with appropri-

ate academic credentials. e counsel of former Church historian Steven E.

Snow applies to biblical scholarship as much as it does to the study of Church

history: “Look for sources by recognized and respected historians, whether

they’re members of the Church or not.”

Such scholars have spent many years

immersed in the history, culture, and literature of the ancient Near Eastern

and Mediterranean worlds. While that experience does not always guarantee

accuracy, their expertise usually helps lter reasonable conclusions from the

occasionally quirky proposals of armchair Bible enthusiasts.

How does one identify good scholars? No set characteristics apply in

every case, but a few apply in many cases. Most legitimate biblical scholars

have earned PhDs from accredited universities. Most have degrees in bibli-

cal studies or related elds like Egyptology, Northwest Semitics, Assyriology,

classics, early Christianity, or Near Eastern archaeology. Most publish origi-

nal research in academic journals and books that are peer reviewed by experts

in the eld. However, these are only rules of thumb: excellent work has been

published by writers who do not match all of these descriptions. In a world

where so much is published that is outdated or idiosyncratic, we simply need

to be mindful of whom we are reading and to pay attention to what their

training and experience qualies them to say authoritatively.

Second, choose a study Bible that is aligned with, or at least respectful of,

your faith in the Savior and your commitment to the restored gospel. Study aids

prepared by Latter-day Saints should of course qualify, and scholarship writ-

ten from other perspectives should at least be respectful of our beliefs and

broadly aligned with our desire to seek out truth. A personal story illustrates

the potential pitfalls of an antagonistic source. Some years ago I was gied

the ESV Study Bible, which I had eagerly anticipated aer reading many

excellent reviews.

is is a truly comprehensive and beautiful book (of over

, pages) with helpful notes, ample use of color, and a user-friendly format.

As I began to use it, I started coming across scattered instances in which the

notes unnecessarily criticized Latter-day Saints, but I was most shocked when

I arrived at an appendix with a multipage exposé of “Mormonism” as a “cult.”

For obvious reasons, I do not recommend this study Bible to fellow Saints.

Given that some study Bibles are disrespectful of our beliefs, one good

option is to choose a study Bible that is ecumenical in its scholarship. Editions

such as e New Oxford Annotated Bible or e HarperCollins Study Bible t

this description; they are written by best-in-their-eld scholars who are trying

Carefully studying the Holy Bible brings great spiritual rewards.

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 37

36

to help readers of any religious background better understand biblical texts in

their original context.

A second option is to deliberately choose a study Bible that incorporates

insights from another religious tradition—one that is not antagonistic towards

others. I particularly enjoy e Jewish Study Bible (for the Old Testament)

and its companion volume, e Jewish Annotated New Testament, because

few people have better insight into Jewish history, culture, and literature than

Jews themselves (see Nephi :). Even though the restored gospel gives me

a dierent point of view than secular scholarship or than Jewish/Catholic/

Protestant scholarship, I have found that my own understanding is oen

enriched by reading what others have noticed.

A third option is to use a study Bible expressly prepared by and for

Latter-day Saints. is option has historically been limited because, despite

the number of helpful commentaries written by Latter-day Saints, few could

be categorized as a fully functioning, academic study Bible as I have been

using the term. e recent release of omas Wayment’s e New Testament:

A Translation for Latter-day Saints—A Study Bible has now provided that

option, at least for the New Testament.

is edition includes a fresh transla-

tion of the entire New Testament, and the notes combine the historical and

cultural background available in other study Bibles with selections from the

Joseph Smith Translation and comprehensive cross-references linking the

New Testament with Restoration scripture.

My Personal Study Bible Recommendations

There are several good study Bibles, and different people will have their own preferences.

These are my favorites in no particular order—check to see if newer editions are available.

Title Publisher Features

The New Testament: A

Translation for Latter-day

Saints—A Study Bible, by

Thomas A. Wayment

Religious Studies Center at

Brigham Young University;

Deseret Book

New Testament only;

Latter-day Saint

perspective

The Jewish Study Bible, 2nd

edition

Oxford University Press Old Testament only; Jewish

perspective

The New Oxford Annotated

Bible, 5th edition

Oxford University Press Theologically neutral;

often used in college

courses

The HarperCollins Study Bible,

2006 update

HarperOne and the Society

of Biblical Literature

Theologically neutral;

often used in college

courses

Title Publisher Features

The Hebrew Bible: A

Translation with Commentary

by Robert Alter

Norton Old Testament only;

divided into three substan-

tial volumes

The New English Translation

at https://netbible.org/

Biblical Studies Press 58,000+ translators’ notes

help explain linguistic

complexities

Using a Study Bible as a Supplement to the Official Latter-day Saint

Editions

While I encourage using study Bibles, I do not recommend that Latter-day

Saints set aside the ocial editions of the Bible published by e Church of

Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which currently include the Latter-day Saint

edition of the King James Version (published in , updated in ), the

Spanish Santa Biblia: Reina-Valera 2009, and the Portuguese Bíblia Sagrada—

Almeida 2015.

Church leaders have instructed that “members should use”

these editions.

At the same time, using other editions in addition to the

Church’s has never been prohibited.

Indeed, several modern apostles have

set an inclusive example by quoting other editions of the Bible in their general

conference addresses.

I rst experienced the value of reading two dierent editions side by side

when I was a missionary in Chile. In those days the Church had not yet pro-

duced its own Spanish Bible, and when I arrived at the missionary training

center I was handed the edition of the Reina-Valera Bible published by

the American Bible Society. During the course of my mission, the constant

comparison of that Bible with my Latter-day Saint Bible helped me learn

things I never would have noticed using just one translation or one set of

study aids. In more recent years, I have continued to use the Latter-day Saint

editions as my primary Bible for devotional reading while keeping one or two

good study Bibles close at hand as supplementary study aids.

As I have read through the Bible multiple times using dierent editions

simultaneously, I have found great benet in combining the strengths of the

King James translation with the strengths of modern translations and in com-

bining the strengths of the study aids in the ocial Latter-day Saint editions

with the strengths of the study aids in academic study Bibles.

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 39

38

Strengths and Weaknesses of the King James Version and Modern

Translations

e inuence of the King James Version “on the English-speaking world is

unparalleled. . . . It has a fair claim to be the most pivotal book ever written,

a claim made by poets and statesmen and supported by tens of millions of

readers and congregations.”

As the Bible of nineteenth-century America,

the language and text of the KJV had a profound inuence on Joseph Smith

and other early leaders of the Restoration.

Especially noteworthy is the use

of King James language in the English translation of the Book of Mormon,

as the revelatory idiom of the Doctrine and Covenants,

and as the basis for

the Prophet’s own translation of the Bible.

e inuential role of the King James Version in the production of

latter-day scripture means that using the KJV gives readers several advan-

tages. When the English translation of the Book of Mormon and other

revelations of the Restoration quote phrases from the KJV, attentive read-

ers can spot the connections and see how modern scripture interprets and

adapts biblical scripture. Certain doctrinal ideas are more easily identied

in the KJV because that version provided the phrases Joseph Smith used to

articulate those doctrines for a latter-day audience.

And nally, because the

archaic and heightened language of the KJV has been the traditional regis-

ter for scriptures, hymns, prayers, and sermons for so long, English-speaking

Saints tend to instinctively view such language as more “spiritual” than every-

day language.

As an example of a scripture block where the King James Version

gives Latter-day Saint readers an advantage, consider Jesus’s famous Olivet

Discourse in Matthew – (compare Mark and Luke ). While reading

Matthew – in a modern translation does clarify vocabulary and syntax,

using the KJV is crucial for Latter-day Saints because Joseph Smith received

two revelatory texts that are based on Matthew as rendered in the King

James Bible. A March revelation (now Doctrine and Covenants )

draws upon the language of KJV Matthew to teach about the signs of

the times, beginning with Doctrine and Covenants : (“I shall come in

my glory in the clouds of heaven”), which adapts KJV Matthew : (“the

Son of man coming in the clouds of heaven with . . . glory”). ese allusions

continue with great frequency

until the Lord stops and says more will be

revealed “concerning this chapter” (meaning Matthew ) when Joseph gets

to it as part of his new translation of the Bible (Doctrine and Covenants

:–). When Joseph reached Matthew a few months later, he was

given a revelatory reworking of the biblical text (now canonized as Joseph

Smith—Matthew in the Pearl of Great Price) that both claries and adds

to the original discourse.

However, while these latter-day revelations in

Doctrine and Covenants and Joseph Smith—Matthew can be fruitfully

studied on their own, their meaning is signicantly enhanced when they are

compared with the biblical chapter on which they build, and when making

those comparisons one must use the King James rendering or many of the

connections will be obscured. us, while modern translations are useful

for studying the Olivet Discourse in its biblical context, the KJV is essential

for seeing how the themes of Matthew have been adapted for a latter-day

context.

Despite the advantages of the King James Version for Latter-day Saints,

there are other ways in which the KJV puts readers at a disadvantage. Brigham

Young University scholars Lincoln Blumell and Jan Martin explain:

ere are essentially two fundamental challenges with the English of the KJV: acces-

sibility and accuracy.

An accessible text uses language that its readers easily understand.

Unfortunately, the sixteenth-century English of the KJV can make comprehension

dicult in places.

An accurate translation of a text uses a second language to carefully represent

the original language as closely as possible. Since the publication of the KJV in

, there have been important advances in understanding Biblical Hebrew and

Greek and numerous discoveries of additional biblical manuscripts that have pro-

vided important textual variations and clarications. . . . Unfortunately, the KJV

text does not reect these advances and in places is simply an inaccurate translation.

e problem of accessibility has increased over time as the English lan-

guage moves further from the vocabulary, grammar, and syntax of the KJV.

e narrative portions of the KJV (such as Genesis and Acts) are still rela-

tively accessible, but the poetic books (such as Job) or the prophetic books

of the Old Testament (such as Isaiah), as well as many of Paul’s epistles in the

New Testament, can be extremely dicult to follow.

e problem of accuracy has also grown more pronounced since scholars

know much more about biblical languages than they did four centuries ago.

is is particularly problematic in the Old Testament because the KJV trans-

lators struggled with several aspects of the Hebrew language, such as how

its poetry worked or what some of the rare vocabulary words meant (some-

times the translators simply guessed).

In addition, the discovery of many

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 41

40

additional ancient biblical manuscripts has allowed scholars to render some

passages more accurately than the KJV translators could. is is particularly

problematic in the New Testament because the KJV translators had access

to only a few late (medieval) Greek manuscripts, which contain more errors

than manuscripts from earlier centuries.

As an example of a passage in which the King James Version falls short,

consider Hosea :–:

When Israel was a child, then I loved him, and called my son out of Egypt.

As they called them, so they went from them: they sacriced unto Baalim,

and burned incense to graven images.

I taught Ephraim also to go, taking them by their arms; but they knew not

that I healed them.

I drew them with cords of a man, with bands of love: and I was to them as

they that take o the yoke on their jaws, and I laid meat unto them.

Passages like this can be very challenging to understand, even for expe-

rienced, college-educated readers. When I come to such passages, I follow a

simple three-step procedure:

1. read the passage in the KJV,

2. read the passage in a modern translation, and

3. reread the passage in the KJV and see if the modern translation

helps make sense of it.

In this case, aer reading Hosea :– in the KJV, I might glance at my

New Oxford Annotated Bible, which uses the New Revised Standard Version

(NRSV) as its translation:

When Israel was a child, I loved him,

and out of Egypt I called my son.

e more I called them,

the more they went from me;

they kept sacricing to the Baals,

and oering incense to idols.

Yet it was I who taught Ephraim to walk,

I took them up in my arms;

but they did not know that I healed them.

I led them with cords of human kindness,

with bands of love.

I was to them like those

who li infants to their cheeks.

I bent down to them and fed them.

Reading the NRSV does not eliminate all challenges, but because the

NRSV is more clearly written, xes certain words based on ancient manu-

script evidence, and presents the text of Hosea in a poetic format, the meaning

pops out with greater clarity. In the NRSV, as Latter-day Saint scholar Grant

Hardy has observed, “e entire passage takes on a striking poignancy as God

compares his love for Israel to the tender care of a father for a toddler.”

Once

I get a better sense of Hosea’s meaning, I can then return to the KJV and

reread it with greater comprehension.

is compare-and-contrast approach allows the best of both worlds: the

traditional text and beautiful cadence of the King James Version combined

with the accessibility and accuracy of newer translations. Using either the

KJV or a modern translation in isolation comes with certain advantages and

disadvantages, but using both in tandem allows them to productively comple-

ment one another.

Strengths of KJV translation Weaknesses of KJV translation

Traditional language and uniformity with

latter-day scripture

Sometimes difficult to understand and some-

times inaccurate

Strengths of modern translations Weaknesses of modern translations

Accessible English using the latest schol-

arship and textual evidence

Plain language may feel “unscriptural” and

Restoration connections less apparent

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study Aids in the Latter-day Saint

Editions of the Bible and Academic Study Bibles

Editions of the Bible published by e Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-

day Saints include study aids designed to help Church members appreciate

the teachings of ancient prophets and apostles in light of the truths of the

restored gospel. ese study aids include

•

cross-references that tie biblical texts to Restoration scripture,

•

a subject concordance (the Topical Guide, or the Guide to the

Scriptures in foreign-language editions) that displays how doctrinal

ideas are expressed across dispensations and scriptural texts,

•

interpretive chapter headings that steer readers toward key doctrinal

matters,

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 43

42

•

extensive quotations from the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible,

and

•

a dictionary (the Bible Dictionary, or the Guide to the Scriptures in

foreign-language editions) that addresses Latter-day Saint concerns

and viewpoints.

ese unique study aids make the Latter-day Saint editions an indispens-

able tool for Church members.

Academic study Bibles also aim to help readers understand the Bible, but

they focus on elucidating the ancient, contextual meaning of the text. ese

aids, which might be found at the bottom of the page, in essays preceding an

individual book, or in appendixes, can include

•

variant readings for a particular passage as found in ancient

manu scripts;

•

alternate translations, or notications of when the Hebrew or Greek

is particularly dicult;

•

explanations of historical, cultural, or linguistic information neces-

sary to properly understand the meaning of the text;

•

identications for the origin of quotations; and

•

a synopsis of how famous or controversial passages have been inter-

preted by dierent faith traditions over history.

In sum, the study aids in the ocial Church editions excel at bringing

restored doctrinal insights to the text. ey are weaker at helping with the

verse-by-verse details and at providing historical and cultural context.

Even

the Bible Dictionary, which provides the most help with that context, has

become increasingly out of date.

In contrast, the study aids in academic study

Bibles excel at illuminating the contextual worlds of the text. Many provide

nearly verse-by-verse insight. But with the exception of resources prepared by

Latter-day Saints, study Bibles do not incorporate the teachings of modern

prophets or help Latter-day Saint readers connect biblical and Restoration

scripture, and some may even oer doctrinally incorrect interpretations.

Personally, if I had to choose between the Restoration insights available

in the Church’s Bible editions or the historical context available in academic

publications, my clear choice would be the Church’s editions. But there is no

reason to choose—we can take advantage of both! eir respective strengths

and weaknesses complement one another so that when one falls short, the

other can help. Let us examine two illustrative examples, John :– and

Jeremiah :–.

John :– contains a rather enigmatic statement regarding the fate

of “the disciple whom Jesus loved,” the apostle John. It raises the possibility

that this disciple “should not die,” and yet the text itself hints at some uncer-

tainty regarding what Jesus meant. With little else to go by, the HarperCollins

Study Bible states, “According to legend, the apostle John . . . lived to a great

age.”

e Jewish Annotated New Testament says that “the Beloved Disciple

has apparently died. is verse corrects the rumor that Jesus had promised

him eternal life.”

e MacArthur Study Bible interprets Jesus’s saying as a

mere “hypothetical statement for emphasis.”

In contrast, the Latter-day Saint edition of the Bible is able to speak more

conclusively about John’s fate. e chapter heading states unequivocally that

“John will not die.”

A footnote points readers to Doctrine and Covenants ,

which contains a revelation given to the Prophet Joseph Smith in April or

May of regarding this very issue: John the Beloved asks Christ for “power

over death, that I may live and bring souls unto thee,” and Christ explains

that he will make John “as aming re and a ministering angel.”

Another

footnote directs readers to the Topical Guide entry for “Translated Beings,”

which expounds on this topic with three references from the Old Testament,

six from the New Testament, six from the Book of Mormon, six from the

Doctrine and Covenants, and two from the Pearl of Great Price. e benets

of the Church’s ocial scriptures are very clear in this case: where academic

study Bibles are lacking or misleading, the Latter-day Saint edition of the

Bible lls in the interpretive hole.

On the other hand, Jeremiah :– highlights a weakness in the

Latter-day Saint editions. While studying the Old Testament in Sunday

School, I once observed an interesting interaction as the Gospel Doctrine

teacher called on class members to read and interpret this passage:

Moreover the word of the Lord came unto me, saying, Jeremiah, what seest thou?

And I said, I see a rod of an almond tree.

en said the Lord unto me, ou hast well seen: for I will hasten my word

to perform it.

Try as they might, the members of the class were at a loss to explain how

“a rod of an almond tree” connects with “hasten[ing] my word to perform it.”

It just made no sense. Furthermore, the only footnote in the Latter-day Saint

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 45

44

Bible was attached to the word seest and pointed readers to the Topical Guide

entry for “Vision,” which oered no help in interpreting Jeremiah’s words.

is is a case in which the Latter-day Saint edition falls short because its

weakness is in providing historical, cultural, and literary context—precisely

what is needed to understand Jeremiah :–. In contrast, any good study

Bible will provide the needed information:

•

e HarperCollins Study Bible: “In the rst vision a wordplay, branch

of an almond tree (Hebrew shaqed) and watching (shoqed), stresses

that God will enact the content of the prophetic word.”

•

e New Oxford Annotated Bible: “Jeremiah sees an almond tree (Heb

‘shaqed’) and is assured that God is watching over (Heb ‘shoqed’) the

prophetic word to fulll it. For similar vision/puns see Am 7.7–9;

8:1–3.”

•

e Zondervan NASB Study Bible: “e Hebrew for ‘watching’

sounds like the Hebrew for ‘almond tree.’ Just as the almond tree

blooms rst in the year (and therefore ‘wakes up’ early—the Hebrew

word for ‘watching’ means to be wakeful), so the Lord is ever watch-

ful to make sure that His word is fullled.”

•

Robert Alter’s e Hebrew Bible: “e question about the riddling

vision ... hinge[s] on a pun.... ‘Almond-tree’ is shaqed; ‘vigilant’ is

shoqed.”

e Church’s edition of the Bible is simply not designed to explain every

verse in this kind of detail. In cases like this, however, a study Bible used as a

supplementary study aid can be enormously helpful and ultimately enriches

one’s experience with the Latter-day Saint edition.

Strengths of Church edition study aids Weaknesses of Church edition study

aids

Connections to latter-day scripture and cor-

rect doctrinal interpretations

Very little historical/cultural context, some

of which is outdated

Strengths of academic study aids Weaknesses of academic study aids

Detailed and up-to-date historical/cultural

context

May not benefit from revealed doctrinal

insights

Challenges and Opportunities

As I have introduced fellow Saints to study Bibles, I have heard a few common

questions and concerns, which I will briey respond to below. ey highlight

some of the challenges involved in supplementing the ocial Latter-day Saint

Bibles with academic resources, but also some of the great opportunities for

spiritual learning.

“A new translation is just someone’s interpretation of the scriptures.” It is true

that translation always involves interpretation; translators must make myriad

choices, from which ancient manuscript to use to which meaning of a word

to pick.

However, for many English-speaking Saints, our default familiar-

ity with the King James Version leads us to assume that the KJV represents

“the scriptures” while modern translations are simply an “interpretation” of

the scriptures. In so doing, we forget that the KJV itself is a translation from

Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek manuscripts and that the translators commis-

sioned by King James I were real people with their own biases—they were

white, male, British, Protestant (mostly bishops or priests of the Church

of England), early-seventeenth-century scholars, whose theological views

reect the turbulent years following the Reformation.

is is not a criti-

cism, simply a recognition that reading a new translation of the Bible is not to

introduce human interpretation, but to move from one set of interpretations

to another. In some cases the KJV translators’ interpretive choices may be bet-

ter, and in other cases, those of modern translators. Supplementing the KJV

with a modern translation allows readers to compare those interpretations

under the guidance of the Spirit.

“Why would I want to read what scholars have to say about the scrip-

tures? Interpreting scripture is the responsibility of prophets and apostles.” In

recommending the academic expertise of biblical scholars, I am in no way

discounting the crucial role of modern prophets. In doctrinal matters, inter-

pretive authority accompanies priesthood keys. President M. Russell Ballard

has reminded us, however, that apostolic authority and academic training are

not the same thing and that dierent kinds of questions require looking for

answers from dierent kinds of sources. “e Lord called the apostles and

prophets to invite others to come unto Christ,” President Ballard said, “not to

obtain advanced degrees in ancient history, biblical studies, and other elds

that may be useful in answering all the questions we may have about [the]

scriptures.” While apostles can readily “respond to certain types of questions,”

he continued, “there are other types of questions that require an expert in

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 47

46

a specic subject matter. . . . If you have a question that requires an expert,

please take the time to nd a thoughtful and qualied expert to help you.”

Elder uentin L. Cook demonstrated this distinction in his September

Face to Face devotional: while answering questions from young adults,

Elder Cook responded to doctrinal questions while deferring historical ques-

tions to the two professionally trained historians, Kate Holbrook and Matt

Grow, who shared the stage with him.

In light of President Ballard’s counsel

and the examples of other apostles like Elder Cook, I recommend that study

Bibles prepared by experts in the eld are a responsible way of answering our

historical, cultural, linguistic, and textual questions about the scriptures.

“Modern English translations make the scriptures too easy. e King James

Version may be dicult to read, but mentally engaging with the words encour-

ages pondering and invites revelation.” Based on my own experience, I agree

that the KJV’s heightened language can promote a more active mental and

spiritual engagement with the biblical text, sometimes precisely because of its

diculty.

However, this virtue can be pushed too far: there is a ne line

between diculty that encourages a productive struggle to understand and

diculty that leads readers to frustration or misunderstanding. For example,

many Latter-day Saints suer from what one writer calls an “Isaiah com-

plex”—that feeling of guilt that follows frustrating attempts to make sense of

Isaiah.

However, as someone who has read the book of Isaiah in the original

Hebrew and in various translations, I would estimate that the diculty of

reading Isaiah in the KJV is reduced by half when one simply follows along

in a modern translation. Reading two translations side by side preserves the

productive spiritual engagement that comes with the KJV’s archaic/height-

ened language while also giving readers linguistic help as needed. is in turn

gives us a greater opportunity to “seek inspiration concerning the message of

scripture rather than relying on the Holy Ghost to parse convoluted syntax

and obsolete vocabulary.”

It is also worth observing that almost none of the biblical authors wrote

in a “fancy” register; they generally wrote Hebrew and Greek in a straight-

forward way that was meant to be understood by common people.

While

there is value in what modern English speakers perceive to be the special, even

spiritual, register of the KJV, we should recognize that this is not how native

Hebrew and Greek speakers would have heard their scriptures. us, a trans-

lation using straightforward, contemporary language does not by its nature

betray the intent of the biblical authors and in some cases may in fact more

closely approximate what they were aiming for.

“Aren’t the scholars who are writing all these notes just overcomplicating the

scriptures? Why would God make the scriptures so obscure that you need a PhD

to understand them?” Certainly much of scripture—particularly central mes-

sages such as the love of God, the saving power of the Atonement of Jesus

Christ, and the need for repentance—is so straightforward that even chil-

dren can understand. And certainly the Lord wants to be understood, which

is why he reveals his word “unto [his] servants . . . aer the manner of their

language, that they might come to understanding” (Doctrine and Covenants

:). e problem is that many messages that were once easily understood

by their original audience can be dicult for a later audience when “the man-

ner of their language” changes—when assumed knowledge about historical

context, linguistic rules, or cultural expectations is no longer assumed but has

changed for new audiences living in dierent times, speaking dierent lan-

guages, and seeing the world through dierent cultural lenses. When scholars

write notes for a study Bible, much of what they are trying to do is simply

get twenty-rst-century, Western, English-speaking readers caught up with

the historical, linguistic, and cultural background that the biblical authors

assumed their audience already possessed. Without that background, mis-

interpretation is oen inevitable.

“I have always looked at this passage in a certain way that has great mean-

ing to me, but this study Bible is saying that it means something dierent.” One

reason the scriptures are so spiritually stimulating is that they are multilayered

and can address dierent needs. It is perfectly possible that a passage of the

Bible might have one meaning in its original context, additional meanings

as used in the Book of Mormon or the Doctrine and Covenants, and any

number of other meanings for readers who receive personalized direction

from the Holy Ghost. Be open to new meanings. Whether an interpretation

comes from the Topical Guide’s use of a scripture or from a scholar’s histori-

cal analysis, we do not want to limit any scripture passage by assuming that

with one explanation we have exhausted its rich interpretive possibilities. As

President Dallin H. Oaks has taught, while “scholarship and historical meth-

ods” may be especially helpful in illuminating “what was meant at the time

the scriptural words were [originally] spoken or written,” we must remember

that “a scripture is not limited to what it meant when it was written but may

also include what that scripture means to a reader today.”

Because of this,

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 49

48

“commentaries, if not used with great care, may illuminate the author’s chosen

and correct meaning but close our eyes and restrict our horizons to other pos-

sible meanings.”

“I don’t read the scriptures to learn about history; I just want to get some

personal revelation.” If someone needs inspiration and simply reading the

scriptures is doing that for her, I commend that eort and am pleased the

scriptures are helping. For long-term spiritual growth, however, more serious

engagement with the word of God yields rich rewards. President Gordon B.

Hinckley taught that “this restored gospel brings not only spiritual strength,

but also intellectual curiosity and growth. Truth is truth. ere is no clearly

dened line of demarcation between the spiritual and the intellectual. . . . e

Lord Almighty, through revelation, has laid a mandate upon this people in

these words: ‘Seek ye out of the best books words of wisdom; seek learning,

even by study and also by faith’ [Doctrine and Covenants :].”

Latter-day Saints have a wonderful example of this kind of inclusive learn-

ing in the Prophet Joseph Smith. is was a man who could take his King

James Bible, read the opening words of Genesis, and see a vision of Moses

beholding creation (Moses ). He could ponder John : and see through

those words the three kingdoms of glory (Doctrine and Covenants ). He

could declare that the enigmatic book of Revelation “is one of the plainest

books God ever caused to be written.”

But despite all that he was able to

learn through the Spirit, Joseph did not believe that this discounted the value

of learning “by study” out of the “best books.” He saw revelation and aca-

demic study as not only complementary, but also mutually reinforcing. For

example, Joseph went through great eort in the winter of – to hire a

Jewish scholar to teach Hebrew to the members of the School of the Prophets

in Kirtland, Ohio.

Even though he had already translated the Book of

Mormon without any formal language training, he wrote of how much “my

soul delights in reading the word of the Lord in the original [Hebrew], and I

am determined to persue [sic] the study of languages untill [sic] I shall become

master of them.”

While working on his new translation of the Bible, the Prophet also drew

upon both spiritual insight and the “best books”—in this case, a kind of study

Bible. Some scholars have suggested that while reading out of his copy of the

King James Version, Joseph would occasionally consult a six-volume commen-

tary series written by Methodist scholar Adam Clarke.

Clarke’s commentary,

though lengthier than the single-volume study Bibles we typically use today,

was set up much like a modern study Bible, with the biblical text occupying

the top half of the page and detailed historical, cultural, literary, and linguis-

tic notes lling the bottom half. It appears that Joseph occasionally drew

upon these academic insights as he worked on his translation. For him, truth

was truth whether it came through revelation or out of the best books, and he

happily gathered together all the truth he could nd.

As we pursue our own study of the scriptures, Joseph’s enthusiasm for

learning, his sensitivity to the Holy Ghost, and his careful use of the best

available biblical scholarship provide a model we would do well to emulate.

Notes

. omas A. Wayment, e New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints—A

Study Bible (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake

City: Deseret Book, ), .

. M. Russell Ballard, “e Miracle of the Holy Bible,” Ensign, May , . For

a detailed treatment of Latter-day Saint engagement with the Bible, see Philip L. Barlow,

Mormons and the Bible: e Place of the Latter-day Saints in American Religion, updated ed.

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, ).

. While the examples used herein are written in English, I hope that my suggestions

will also prove helpful to readers who wish to nd reliable study Bibles in other languages.

. ese subscripts are reproduced in the King James Version, but most modern Bible

editions omit them because they were composed centuries aer Paul and are oen incorrect.

See Bruce M. Metzger and Bart D. Ehrman, e Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission,

Corruption, and Restoration, th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, ), –.

. See B. Barry Levy, “Rabbinic Bibles, Mikra’ot Gedolot, and Other Great Books,”

Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish ought , no. (): –.

. Although some notes are anti-Catholic or otherwise extreme in their views, the

polemical nature of the Geneva Bible has oen been exaggerated. See David Daniell, e

Bible in English: Its History and Inuence (New Haven: Yale University Press, ),

–.

. Gordon Campbell, Bible: e Story of the King James Version, 1611–2011 (Oxford:

Oxford University Press, ), .

. See R. Todd Mangum and Mark S. Sweetnam, e Scoeld Bible: Its History and

Impact on the Evangelical Church (Colorado Springs, CO: Paternoster, ). On pages

– they discuss the impact that this particular edition had on subsequent study Bibles.

. Donald Senior, John H. Collins, and Mary Ann Getty, eds., e Catholic Study

Bible, rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, ). is study Bible uses the New

American Bible Revised Edition, a update of a translation created and used by

members of the Roman Catholic Church.

. Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds., e Jewish Study Bible, nd ed. (Oxford:

Oxford University Press, ). is study Bible uses the New Jewish Publication Society

(Tanakh) translation, rst published in by Jewish scholars. See also Amy-Jill Levine

and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds., e Jewish Annotated New Testament, nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, ).

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 51

50

. Harold Attridge, ed., e HarperCollins Study Bible, rev. ed. (San Francisco:

HarperOne, ). e study aids in this edition, which were produced by the Society of

Biblical Literature, accompany the New Revised Standard Version, a translation that

was produced by an ecumenical group of scholars and is oen used in academic writing.

. Michael D. Coogan, ed., e New Oxford Annotated Bible, th ed. (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, ). is study edition uses the New Revised Standard Version.

. Craig S. Keener and John H. Walton, eds., Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (Grand

Rapids, MI: Zondervan, ), viii. is edition uses the New King James Version, a transla-

tion published in . is same study Bible has an alternate edition, published in ,

that uses the New International Version, an evangelical Protestant translation rst published

in and updated in and . Another study Bible published by Zondervan with a

similar focus is the Archaeological Study Bible, which also comes in either the NIV () or

the KJV ().

. e New English Translation (Biblical Studies Press, ), now in its second

edition (), is available to purchase in physical form, but the notes are so extensive that

it is easiest to use on the web. Although the NET is a fresh translation of the entire Bible,

when I use the website, netbible.org, I am usually not as interested in the translation itself as

in the tens of thousands of translators’ notes that allow someone to peek behind the scenes at

the dierent problems and possibilities in the translation. Other websites showing the words

operating behind English translations include biblehub.com and www. blueletterbible.org.

. Luis Palau, ed., Starting Point Study Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, ).

is edition uses the New International Version.

. Martin H. Manser and Michael H. Beaumont, eds., Christian Basics Bible (Carol

Stream, IL: Tyndale House, ). is edition uses the New Living Translation, rst pub-

lished in and updated in and .

. In addition to study Bibles that focus on personal application, there are also

niche editions that single out some other theme. For example, e Green Bible (New York:

HarperOne, ) supplements the New Revised Standard Version with essays and sidebars

discussing our responsibility to care for the environment, as well as God’s relationship with

nature. Verses that have something to do with the earth, animals, stewardship, or related

issues are printed in green. Another example is Catherine Clark Kroeger and Mary J. Evans,

eds., e Women’s Study Bible (Oxford: Oxford University Press, ). is edition uses the

New Living Translation, and the study aids are particularly sensitive to women’s perspectives,

both ancient and modern.

. Life Application Study Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan; Carol Stream, IL:

Tyndale House, ). is edition uses the New International Version.

. See Gaye Strathearn, “Modern English Bible Translations,” in e King James Bible

and the Restoration, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham

Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, ), –; and Ben Spackman, “Why

Bible Translations Dier: A Guide for the Perplexed,” Religious Educator , no. ():

–.

. One study Bible using the King James Version is the three-volume Footnotes to the

New Testament for Latter-day Saints, edited by Kevin Barney and freely available to download

as PDF les at feastupontheword.org/Site:NTFootnotes. While the notes on each page do

oer some insights regarding historical, cultural, literary, or doctrinal issues, these kinds of

notes are outnumbered by those interpreting the four-hundred-year-old vocabulary, grammar,

and syntax of the KJV. Barney observes, “Much of the need for this book would be obviated

if one were simply to read the [New Testament] in a good, modern translation” (Barney,

Footnotes, :iii).

. D. A. Carson, ed., NIV Zondervan Study Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan,

). is edition uses the New International Version.

. Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible, .

. See Daniel Silliman, “e Most Popular Bible of the Year Is Probably Not What You

ink it Is,” Washington Post, August , www.washingonpost.com/news/acts-of-faith

/wp///the-most-popular-bible-of-the-year-is-probably-not-what-you-think-it-is.

. Steven E. Snow, “Balancing Church History,” New Era, June , .

. ESV Study Bible (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, ). is edition uses the English

Standard Version, an evangelical Protestant translation published in and revised most

recently in .

. See Wayment, New Testament. For reviews of this work, see Nicholas J. Frederick,

“e New Testament: A Translation for Latter-day Saints,” BYU Religious Education Review,

Fall , –; and Daniel O. McClellan, “‘As Far as It Is Translated Correctly’: Bible

Translation and the Church,” Religious Educator , no. (): –.

. Regarding the original English edition, see Lavina Fielding Anderson, “Church

Publishes First LDS Edition of the Bible,” Ensign, October , –. For subsequent

editions and updates, see “Church Publishes LDS Edition of the Holy Bible in Spanish,”

Ensign, September , –; “Church Releases New Edition of English Scriptures in

Digital Formats,” Ensign, April , ; and “LDS Edition of Bible in Portuguese,” Ensign,

November , . It is worth noting that the Church does not use the original text

of the King James Version, but rather an update of a revision prepared by Benjamin Blayney

in . See Kent P. Jackson, “e English Bible: A Very Short History,” in Jackson, King

James Bible, .

. Handbook 2: Administering the Church (Salt Lake City: e Church of Jesus Christ

of Latter-day Saints, ), ...

. For example, in an address at Brigham Young University, Elder John K. Carmack

said, “We clearly prefer the King James Version . . . , but we are not adamant about that. Any

responsibly prepared version could be used and might be helpful to us.” John K. Carmack,

“e New Testament and the Latter-day Saints,” in Sperry Symposium Classics: e New

Testament, ed. Frank F. Judd Jr. and Gaye Strathearn (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center,

Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, ), .

. For some examples, see Neal A. Maxwell, “‘Lest Ye Be Wearied and Faint in Your

Minds,’” Ensign, May , (quoting the Revised Standard Version); Jerey R. Holland,

“Miracles of the Restoration,” Ensign, November , (quoting the New English Bible);

Robert D. Hales, “In Remembrance of Jesus,” Ensign, November , (quoting the

New International Version); Jerey R. Holland, “‘Abide in Me,’” Ensign, May ,

(quoting the Reina-Valera ); Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “In Praise of ose Who Save,” Ensign,

May , (quoting the English Standard Version); Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Fourth Floor,

Last Door,” Ensign, November , , (quoting the New International Version);

Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “e Greatest among You,” Ensign, May , , (quoting the

New International Version and the New English Translation); Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Perfect

Love Casteth Out Fear,” Ensign, May , – (quoting the New King James Version);

and Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Missionary Work: Sharing What Is in Your Heart,” Ensign, May

, (quoting the English Standard Version).

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 53

52

. Because of the signicant inuence of the King James Version, Christians have built

up a great deal of mythos regarding the knowledge and skill of its translators, and Latter-day

Saints have sometimes repeated these exaggerations. For example, without diminishing in

any way the translators’ obvious expertise or the possibility of inspiration in their work, it is

simply not the case that “it would be dicult today to gather scholars with the knowledge

of ancient languages possessed by these men.” Richard N. W. Lambert and Kenneth R. Mays,

“ Years of the King James Bible,” Ensign, August , . ere are any number of biblical

scholars today whose language expertise is superior simply because they are drawing from

over four hundred years of additional research on biblical languages.

As one example, KJV Proverbs : reads, “Burning [=fervent] lips and a wicked heart

are like a potsherd [=an earthen vessel] covered with silver dross.” e KJV translates the

Hebrew phrase ksp sgm as “silver dross,” but this does not make sense within the context of

this passage on hypocrisy because dross is a negative material and the image requires some-

thing attractive that hides something inferior underneath, just as “burning lips” and a “wicked

heart” are negative qualities within a person. Furthermore, silver dross was not used to cover

earthenware but would have been discarded. A solution to this puzzle became available in

when French archaeologists uncovered the remains of Ugarit, a late second-millennium

BC city that once thrived on the coast of what is now Syria. e people there spoke Ugaritic,

a language closely related to Biblical Hebrew, and the decipherment of Ugaritic texts has

allowed scholars to better understand the Hebrew vocabulary of the Old Testament. In this

instance, a Ugaritic word spsg “glaze” makes it possible to reinterpret the Hebrew of Proverbs

: as k spsgm, meaning “like glaze,” which better ts the context because glaze was

indeed something attractive used to hide ordinary earthenware underneath. See Kenneth L.

Barker, “e Value of Ugaritic for Old Testament Studies,” Bibliotheca Sacra ():

–. Several modern English translations of the Bible reect this insight (e.g., the English

Standard Version, the New English Translation, and the New Revised Standard Version).

e point is that the King James translators could not have possibly made better sense of the

Hebrew without additional data, which did not come until aer . Recognizing instances

like this in which modern translations are more accurate than the KJV does not demean

either the skill or the sincere intent of the KJV translators, it simply acknowledges that

modern scholars have learned a great deal since that time and are able to use that knowledge

to translate the Bible more accurately than ever before.

. See Carl W. Grin and Frank F. Judd Jr., “Principles of New Testament Textual

Criticism,” in How the New Testament Came to Be, ed. Kent P. Jackson and Frank F. Judd Jr.

(Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret

Book, ), –; Carol F. Ellertson, “New Testament Manuscripts, Textual Families, and

Variants,” in Jackson and Judd, How the New Testament Came to Be, –; Lincoln H.

Blumell, “e Text of the New Testament,” in Jackson, King James Bible, –; Lincoln H.

Blumell, “A Text-Critical Comparison of the King James New Testament with Certain

Modern Translations,” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity (): –; omas A.

Wayment, “Textual Criticism and the New Testament,” in Blumell, New Testament History,

Culture, and Society, –; and Lincoln H. Blumell, “e Greek New Testament Text of

the King James Version,” in Blumell, New Testament History, Culture, and Society, –.

Regarding the Joseph Smith Translation, see Spackman, “Why Bible Translations Dier,”

–.

. Hardy, “King James Bible and the Future of Missionary Work,” .

. For a detailed treatment of the merits of comparing dierent translations, see

Grant Hardy, “e King James Bible and the Future of Missionary Work,” Dialogue , no.

(): –.

. Melvyn Bragg, e Book of Books: e Radical Impact of the King James Bible,

1611–2011 (Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint, ), –.

. See Grant Underwood, “Joseph Smith and the King James Bible,” in Jackson, King

James Bible, –; and Barlow, Mormons and the Bible, –.

. See Daniel L. Belnap, “e King James Bible and the Book of Mormon,” in Jackson,

King James Bible, –. Regarding the presence of King James language in the Book of

Mormon, Jan J. Martin, “e eological Value of the King James Language in the Book of

Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (): –, points out that the Book

of Mormon self-identies its purpose as both establishing truths in the Bible and restoring

truths lost from the Bible. “At the time the Book of Mormon was translated into English,”

Martin writes, “the King James translation was the authoritative version of the Bible, mak-

ing it the Bible that the Book of Mormon had to clarify. Furthermore, because theological

concepts are inseparable from the language used to express them, . . . the Book of Mormon

could not convincingly establish truths articulated in the KJV unless it employed seven-

teenth-century terminology.”

. See Eric D. Huntsman, “e King James Bible and the Doctrine and Covenants,” in

Jackson, King James Bible, –; and Nicholas J. Frederick, “e New Testament in the

Doctrine and Covenants,” in New Testament History, Culture, and Society: A Background to

the Texts of the New Testament, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center,

Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, ), –.

. See Kent P. Jackson, “e King James Bible and the Joseph Smith Translation,” in

Jackson, King James Bible, –.

. Examples of Latter-day Saint doctrines that are articulated using phrases from

the King James Version include the “dispensation of the fulness of times” (Ephesians :;

compare Doctrine and Covenants :; :; :; :, ; :), the “celestial”

kingdom ( Corinthians :; compare Doctrine and Covenants :, , , , ; :,

; :, , , , , , –; :; :–; :; :; :, , ; “A Facsimile

from the Book of Abraham, No. ”), and premortal life as a “rst estate” (Jude :; compare

Abraham :, ). Because newer Bibles oen translate these phrases dierently, their bibli-

cal origin is only apparent when consulting the KJV.

. KJV Matthew :Doctrine and Covenants :; KJV Matthew

:Doctrine and Covenants :; KJV Matthew :, Doctrine and Covenants

:; KJV Matthew :Doctrine and Covenants :; KJV Matthew :Doctrine

and Covenants :; KJV Matthew :Doctrine and Covenants :; KJV Matthew

:Doctrine and Covenants :; KJV Matthew :Doctrine and Covenants :;

KJV Matthew :Doctrine and Covenants :.

. See Kent P. Jackson, “e Olivet Discourse,” in e Life and Teachings of Jesus

Christ: From the Transguration through the Triumphal Entry, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel

and omas A. Wayment (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, ), –.

. Lincoln H. Blumell and Jan J. Martin, “e King James Translation of the New

Testament,” in Blumell, New Testament History, Culture, and Society, ; paragraph breaks

have been added. For a similar evaluation, see Leland Ryken, e Word of God in English:

Criteria for Excellence in Bible Translation (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, ), –.

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 55

54

While the Bible Dictionary remains reasonably functional for most Church members’

everyday needs, its deciencies are yet another reason it can be helpful to supplement the

Church’s ocial Bible with a modern, academic resource. Robert J. Matthews, one of the

primary editors for the Bible Dictionary during the s, himself recognized that not all

the information would remain current and is “subject to reevaluation as new discoveries

or additional revelation may require.” He advised that “if an in-depth discussion is desired,

the student should consult a more exhaustive dictionary.” Matthews, “Using the New Bible

Dictionary,” .

. HarperCollins Study Bible, .

. Jewish Annotated New Testament, .

. e MacArthur Study Bible (Nashville: omas Nelson, ), . is edition

uses the New American Standard Bible, which was published in with an update in .

. is is the reading in the edition of the Latter-day Saint Bible in English. e

original heading spoke of “John’s translation.”

. is revelation is usually dated to April based on the recollection of Joseph

Smith a decade later; see “History, –, volume A- [ December – August

],” p. , e Joseph Smith Papers, www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history

---volume-a---december---august-/. On the possibility that it

was given in May, see Frank F. Judd Jr. and Terry L. Szink, “John the Beloved in Latter-day

Scripture (D&C ),” in e Doctrine and Covenants: Revelations in Context, ed. Andrew H.

Hedges, J. Spencer Fluhman, and Alonzo L. Gaskill (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center,

Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, ), –. e original version

of the revelation, found on pp. – of Revelation Book (www.josephsmithpapers.org

/paper-summary/revelation-book-/) and as Chapter VI in the Book of Commandments

(www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/book-of- commandments-/), was later

expanded with additional detail for the Doctrine and Covenants (www

. josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/doctrine-and-covenants-/). It is this

expanded version that contains the phrases I have quoted herein.

. Of course, modern revelation and academic scholarship are not mutually exclusive.

omas Wayment’s New Testament study Bible, written specically for a Latter-day Saint

audience, uses the best academic scholarship but in this case also points out that John’s fate is

described in Nephi :– and Doctrine and Covenants :–.

. Kenneth Barker, ed., e Zondervan NASB Study Bible (Grand Rapids, MI:

Zondervan, ). is edition uses the New American Standard Bible.

. Robert Alter, e Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary, Volume 2:

Prophets (New York: Norton, ). is three-volume study Bible uses Alter’s own transla-

tion, which aims to capture the avorful poetics of the original Hebrew.

. On the challenges translators face, see Spackman, “Why Bible Translations Dier,”

–; and McClellan, “As Far as It Is Translated Correctly,” –.

. For the context from which the King James translators emerged and worked,

see Adam Nicolson, God’s Secretaries: e Making of the King James Bible (New York:

HarperCollins, ). Nicolson notes, “Of course, the King James Bible did not spring from

the soil of Jacobean England as quietly and miraculously as a lily. ere were arguments and

struggles, exclusions and competitiveness. It was the product of its time and bears the marks

of its making” (xiii).

. M. Russell Ballard, “uestions and Answers” (BYU devotional, November

), speeches.byu.edu/talks/m-russell-ballard_questions-and-answers/. On another

. For the development of the Latter-day Saint edition of the Bible in English, see

Robert J. Matthews, “e New Publications of the Standard Works—, ,” BYU

Studies , no. (): –; Fred E. Woods, “e Latter-day Saint Edition of the King

James Bible,” in Jackson, King James Bible, –; and the documentary at Promised Day:

e Coming Forth of the LDS Scriptures, broadcast on BYUtv on October , www.byutv

.org/player/bee-f-a-b-fb/that-promised-day. While the Spanish

and Portuguese editions are based on the English edition, they feature several language- and

culture-specic adaptations, as well as some improvements over the English edition. See

Joshua M. Sears, “Santa Biblia: e Latter-day Saint Bible in Spanish,” BYU Studies Quarterly

, no. (): –.

. e Latter-day Saint editions of the Bible do include some footnotes that oer

information on historical, cultural, or textual matters, but they appear very infrequently, and

several of the notes need to be revised. Some examples of mistakes that remain uncorrected

include Isaiah :, footnote b (the phrase “heifer of three years old” in the KJV does not

suggest that Zoar “should still have been young and vigorous,” rather the Hebrew phrase

translated “heifer of three years old” should have been transliterated as a town named Eglath-

shelishiyah); Ezekiel :, footnote a (the Hebrew behind KJV’s “Syria” is indeed “Aram,”

but the Hebrew word itself is misspelled and should read “Edom”); Mark title footnote (the

Joseph Smith Translation does not entitle the book “e Testimony of St. Mark”); Mark :,

footnote a (the JST of Mark was originally created by copying the JST of Matthew , but

subsequent revisions created some dierences between the two texts); Luke title footnote

(the Joseph Smith Translation does not entitle the book “e Testimony of St. Luke”); John

:, footnote a (“Cephas” is Aramaic, not Greek); and John :, footnote a (the description

of Greek manuscripts is not correct).

. e Bible Dictionary, which rst appeared in the edition of the Latter-day

Saint Bible, is a revision of a Bible dictionary published decades earlier by Cambridge

University Press, with the updates focusing primarily on aligning the entries with Latter-

day Saint doctrine. See Robert J. Matthews, “Using the New Bible Dictionary in the LDS

Edition,” Ensign, June , –; and Barlow, Mormons and the Bible, –. Although

a few minor adjustments were made in the edition, the scholarly information has not

been signicantly revised in well over half a century and several entries are now out of date.

As one example, the entry titled “Jamnia” describes it as a place “where, about A.D. ,

a council of rabbis declared the Old Testament canon to be completed. . . . Traditionally, at

this council the canon of the Old Testament was decided.” e idea that there was a “council

of Jamnia” where the Old Testament canon was xed became popular in the early twentieth

century, but has been thoroughly discredited since the s. See Jack P. Lewis, “Jamnia

Revisited,” in e Canon Debate, ed. Lee Martin McDonald and James A. Sanders (Peabody,

MA: Hendrickson, ), –.

Even entries focused on Latter-day Saint topics are not all current. For example, the

entry “Joseph Smith Translation” states, “Although the major portion of the work was

completed by July , [the Prophet] continued to make modications while preparing a

manuscript for the press until his death in .” Although scholars used to think the Joseph

Smith Translation was never nished, further research has since concluded that Joseph

completely ceased work on the Joseph Smith Translation in , and from then on his sole

aim was to publish the work. See Kent P. Jackson, “New Discoveries in the Joseph Smith

Translation of the Bible,” Religious Educator , no. (): –.

Religious Educator · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 Study Bibles: An Introduction for Latter-day Saints 57

56

occasion President Ballard gave similar counsel: “Wise people do not rely on the internet to

diagnose and treat emotional, mental, and physical health challenges. . . . Instead, they seek

out health experts, those trained and licensed by recognized medical and state boards. . . .

[Similarly,] we should nd thoughtful and faithful Church leaders to help us. And, if neces-

sary, we should ask those with appropriate academic training, experience, and expertise for

help. is is exactly what I do when I need an answer to my own questions that I cannot

answer myself.” M. Russell Ballard, “By Study and By Faith,” Ensign, December , .

. See a recording of the devotional at www.churchoesuschrist.org/media-library

/video/---worldwide-devotional-for-young-adults-a-face-to-face-event-with

-elder-cook.

. Several Latter-day Saints have pointed to this positive aspect of the KJV’s archaic

language. Ronan Head observes that “there is merit in the struggle to understand, as it

forces the Latter-day Saints to rely on revelation.” Ronan James Head, “Unity and the King

James Bible,” Dialogue , no. (): . Lincoln Blumell and Jan Martin write that “the

seventeenth-century phraseology feels richer and more capable of carrying complex and

multiple meanings than most twentieth- and twenty-rst-century translations do. Flattened

language, language that is submissive to its audience, loses some, if not all, of its ability to

move, challenge, chastise, and inspire. It is true that the language of the KJV can be strange

and dicult in places, but strange does not mean incomprehensible and dicult does