Article

__________________________________________________

a

Jindal Global Business School, O. P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat, Haryana, India (f09anujs@iimidr.ac.in)

b

Indian Institute of Management Nagpur, Maharashtra, India (kapilk@iimnagpur.ac.in)

c

Indian Institute of Management Nagpur, Maharashtra, India (prakash@iimnagpur.ac.in)

d

Indian Institute of Management Nagpur, Maharashtra, India (phd22abhishek@iimnagpur.ac.in)

Corresponding Author:

Kaushik (kapilk@iimnagpur.ac.in)

416

Leveraging Text Mining for Trend Analysis and

Comparison of Sustainability Reports: Evidence

from Fortune 500 Companies

American Business Review

Nov. 2022, Vol.25(2) 416 - 438

© The Authors 2022, CC BY-NC

ISSN: 2689-8810 (Online)

ISSN: 0743-2348 (Print)

Anuj Sharma

a

, Kapil Kaushik

b

, Prakash Awasthy

c

and Abhishek Gawande

d

https://doi.org/10.37625/abr.25.2.416-438

ABSTRACT

In the recent upsurge in environmental concerns, business sustainability has become more prominent than

ever. Organizations worldwide are expected to function sustainably, causing the least negative impact on the

environment and promoting harmony among the firm, environment, and society. Most firms report their

actions related to sustainability in corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports. This research aims to

understand and analyze contemporary trends in CSR reports by Fortune 500 companies using text mining. It

compares how the focus of sustainability reports varies across countries and industries along key dimensions

of sustainability (i.e., environmental, economic, social, and government). Findings from the study suggest

variations in the focus of sustainability reports based on various factors, such as country of origin and company

size, sector, and tenure, on the Fortune 500 list. Thus, it helps to gain a deeper understanding of the company’s

motivations for focusing on various dimensions of corporate sustainability.

KEYWORDS

Sustainability, Text Mining, Government Regulation, Sustainability Reporting, Environmental

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, issues pertaining to sustainability have become a topic of concern for regulators,

businesses, and researchers (Linnenluecke and Griffiths, 2013; Perkiss et al., 2020). Firms and

governments across countries have started to recognize that addressing environmental and social

challenges, such as poverty and climate change, has become more critical than ever (UNDP Annual

report 2021; Kumar et al., 2022). For example, rising CO

2

emissions are a major global issue

(Subbaraman, 2022). To address these challenges, business organizations have started adopting

sustainability-related practices in their policies and programs, either voluntarily or as a response to

government regulations (Dahlmann and Bullock, 2020; Lorenzoni and Benson, 2014). Moreover,

organizations publish details of their activities related to sustainability through annual reports,

sustainability reports, or Environmental Social Governance reports. Furthermore, several business

organizations have implemented frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) to

understand and report sustainability-related initiatives in a structured and globally recognizable form.

The structured GRI framework is conducive to performing a comparative analysis of such reports.

In addition to actions by regulators and business organizations on sustainability fronts, there has

been a surge in sustainability research by academics and practitioners over the last couple of decades.

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

417

A review article by Minutiello and Tettamanzi (2021) suggests that the disclosure quality of

sustainability reporting is increasingly becoming a relevant research topic because the extent of

disclosure reflects a firm’s long-term performance and value creation for its stakeholders. Analyzing

almost 20 years of literature, Purvis et al., (2019) discuss three primary pillars of sustainability:

economic, social, and environmental. These three pillars were also explained from a triple-bottom-line

perspective by Elkington (2018). Rasmussen et al., (2017) used three pillars of sustainability to track

sustainability indicators in agricultural commodity production. The economic pillar pertains to profit,

which is a significant determinant of a firm’s success and survival, at least in the short- to medium-

term. The economic pillar includes better corporate governance and does not consider “profit at any

cost” to be appropriate. The social pillar emphasizes the importance of following business practices

that are fair to all stakeholders and neighboring communities and not just to shareholders. The social

pillar involves various responsible actions from the organization that promote giving back, including,

but not limited to, learning and growth opportunities, maternity/paternity leave for employees, and

better working conditions (Roberts, 2021). The environmental pillar refers to the firm’s responsibility

toward causing minimum negative externality in terms of emissions, pollution, and climate change,

which are generally unaccounted for while pricing the products traditionally. It involves initiatives from

the firm, such as zero-waste, zero-deforestation, water harvesting, efficient machines/equipment

usage, reduced packaging and transportation, recycling, and the usage of renewable energy. Based

on a review of the extant literature on sustainability and a content analysis of sustainability reports,

the authors generated a list of keywords representing each dimension of sustainability. The initial list

of such keywords was further refined using bigram analysis, which is discussed in detail in the

methodology section of the paper. These factors are of particular interest to regulators and

researchers in identifying problems concerning the variation in sustainability disclosures.

This study analyzes the sustainability reports of Fortune 500 firms from a three-pillar perspective

of sustainability. Moreover, it has been reported (Lyon et al., 2018; OECD, 2001) that government

regulations and policies play a critical role in enforcing organizations to take positive actions on

environmental and social fronts (Dauvergne and Lister, 2012). Therefore, in our study, we included a

fourth dimension: government regulation. This research proposes a framework to represent, analyze,

and compare sustainability reports by firms in terms of their focus on three pillars of sustainability

(economic, social, and environmental) along with government regulations. Using this framework, this

study aims to answer the following questions related to sustainability. Which dimensions of

sustainability are focused more on by companies in their reports? Why do companies focus on a

particular sustainability dimension? What external and internal factors drive a firm’s focus on these

different dimensions of sustainability?

The aforementioned questions were chosen because the literature reveals that organizations are

skewed in reporting on certain dimensions of sustainability (Hahn and Kühnen, 2013). Firms show such

behavior as they are bound by budgetary constraints, as a result of which the firms focus on low-

hanging fruits to generate relatively faster outcomes and impact. In certain cases, firms are bound by

regulatory pressure. For example, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a global

health crisis. Globally, governments have pushed corporate entities to allocate their Corporate Social

Responsibility (CSR) budgets to improve the overall health and safety of their employees and

surrounding communities. In response, corporations across the globe have shifted their attention to

the social aspects of sustainability (Klymenko and Lillebrygfjeld Halse, 2021).

To answer the aforementioned questions, this study analyzes sustainability reports of leading

Fortune 500 companies on the economic, social, environmental, and government dimensions

(henceforth referred to as the four dimensions). We developed a novel methodology to generate

scores for the four dimensions of sustainability from sustainability reports of 360 companies in the

Fortune 500. To this end, we extended the sustainability score calculation proposed by Yadava and

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

418

Sinha (2016). In addition, we automated this process through an algorithm using text-mining

techniques. Based on the review of the literature, the authors synthesized the significant determinants

of sustainability reporting (Farisyi et al., 2022; Haidar et al., 2021). These factors were further

categorized into internal and external. Furthermore, we conducted an analysis to explore the

influence of external (origin country of company, sector, etc.) and internal (company size, tenure on

Fortune 500 list) factors on the sustainability scores along the four dimensions of sustainability.

Moreover, we conducted an analysis to explore the influence of external (origin country of

company, sector, etc.) and internal (company size, tenure on Fortune 500 list) factors on the

sustainability scores along the four dimensions of sustainability. We found that the development

ranking of a firm’s country of origin influences the economic and social scores reflected in the

sustainability report. Companies from relatively less developed countries are likely to have more focus

on economic development, while on the other hand, companies from developed countries have more

focus on the environmental dimension. Furthermore, the impact of other factors such as company

size, sector, and company age on the four dimensions of sustainability has also been analyzed.

The quantity of non-financially reported data is growing exponentially across sectors and

geographies. Thus, it is becoming increasingly important to assess the quality and quantity of the

reported data to derive meaningful insights. To bridge this gap, the present study developed a novel

methodology to assess the semantics of corporate sustainability data. By developing an automated

alternative to the manual evaluation of sustainability data proposed by Yadava and Sinha (2016), this

study contributes to overcoming the biases associated with manual evaluation.

BACKGROUND

Content analysis of firms’ non-financial disclosures has attracted the attention of researchers in both

academia and industry exploring sustainability trends in various parts of the world. Many studies have

focused on specific geographies. Skouloudis and Evangelinos (2009) evaluated the compliance and

quality of sustainability reports from Greek companies using the GRI 2002 reporting framework.

Yadava and Sinha (2016) assessed the sustainability reporting disclosures of leading Indian private- and

public-sector companies based on the GRI 2011 guidelines. Loh et al., (2017) investigated how the

adoption and quality of sustainability reporting disclosures are related to a firm’s market value for

Singaporean listed companies. Hongming et al., (2020) explored the relationship between corporate

sustainability practices and firm performance in 50 publicly limited companies on the Pakistan Stock

Exchange. Girón et al., (2021) investigated the relationship between sustainability disclosure and a

firm’s financial performance, particularly for firms in developing economies, such as Asia and Africa.

Some studies have explored sustainability reporting disclosures for a particular sector. Mahmood

and Orazalin (2017) examined Kazakhstan’s oil, gas, and mining companies to study the relationship

between board characteristics and sustainability reporting disclosures. Buallay (2019) investigated the

European banking sector to determine whether sustainability reporting disclosures are associated

with bank performance. Kumar and Prakash (2019) examined the banking sector to study Indian banks’

sustainability reporting. Raquiba and Ishak (2020) depicted the extent of sustainability reporting

practices in 19 energy companies in Bangladesh.

Several studies have targeted the Forbes Fortune list to understand the sustainability reporting

disclosures of leading firms across the globe and explore the relationship between firms’ corporate

sustainability (CS) reporting behavior and variables such as firm size, age, sector, ownership, country

of origin, and industry type. Morhardt et al., (2002) assessed the extent of sustainability reporting

using the GRI 2000, ISO 14031, and other criteria for 40 of the world’s largest companies. Jose and Lee

(2007) analyzed corporate environmental disclosures for the 200 largest corporations in the world on

the Fortune list. Furthermore, they investigated the environmental reporting of the 200 largest

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

419

corporations in the world and found that environmental disclosures vary with respect to country and

industry type. Morhardt (2010) examined the sustainability reports of 454 Fortune Global 500

companies and Fortune 1000 companies and observed that organization size has a negligible impact

on the sustainability reporting of the sampled companies. Gallo and Christensen (2011) analyzed the

effect of firm size and ownership on sustainability-related behavior and found that larger companies

report more sustainability information. In terms of firm ownership, public companies engage more in

sustainability reporting than private firms. Adler et al., (2018) specifically analyzed the corporate

disclosures related to wildlife, biodiversity, and threatened species of the top 150 Fortune Global

companies for the year 2014 and observed that the reporting by the sampled companies on

biodiversity and threatened species is quite limited, and there is inconsistency in reporting across the

index items, even among the high-scoring companies. Schreck and Raithel (2018) investigated the

effects of corporate social performance (CSP), visibility, and firm size on sustainability reporting levels

and observed that firm size has an inverted U-shaped relationship with sustainability reporting.

Ardiana (2021) assessed stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting by examining 646

sustainability reports of Fortune Global 500 companies from 2015 to 2017 and found a lower level of

stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting disclosures.

The aforementioned literature pertaining to the evaluation of sustainability reporting disclosures

has utilized different methodologies for assessing the quality, adherence, and extent of sustainability

reporting. Initial studies approached the analysis with the help of content analysis of reports using

human coders (Abbott and Monsen, 1979; Aggarwal and Singh, 2018; Daub, 2007; Jose and Lee, 2007;

Morhardt et al., 2002; Morhardt, 2010; Vormedal and Ruud, 2009; Yadava and Sinha, 2016; Zhang et al.,

2020). Later, some studies started to explore tools and text-mining techniques for conducting a

content analysis of CS reports. For instance, Székely and Vom Brocke (2017) applied a natural language

processing technique using topic modeling to identify the most common topics and practices in more

than 9,500 corporate sustainability reports published between 1999 and 2015. Amini et al., (2018)

performed a thematic and content analysis on sustainability reports of 2,013 Fortune 500 companies

using Leximancer software. Harymawan et al., (2020) examined the tone of language in sustainability

reports of construction sector companies listed in the Indonesian Stock Exchange using a sentiment

analysis technique in Python.

Recent studies of large firms in low- and middle-income countries in Africa and Asia have

investigated the key company features that influence the adoption and reporting of sustainability

practices. For instance, Kazemikhasragh et al., (2021) found that some peculiar characteristics such as

the type of company, its economic performance, increased engagement in CSR initiatives, and its

assurance by external parties have a positive correlation with the adoption of sustainability reporting.

The study by Cicchiello et al., (2022) reported that factors such as higher market-to-book value, higher

adoption of external assurance of reports, and higher representation of women and young directors

in the company’s board structure are positively related to the adoption of sustainability reporting.

Although scholars and practitioners have focused a great deal of attention toward the three-pillar

perspective on sustainability as proposed by Purvis et al., (2019), the current study has added

government regulation and compliance as the fourth pillar because the non-financial reporting

motives are highly influenced by regulatory requirements (Kolk, 2003). This is also evident from the

fact that sustainability reporting disclosures have entered from the voluntary to the mandatory realm,

and there is growing regulatory pressure in several countries, including the G20 members (European

Union and 19 countries including India, China, the UK, and the USA) that require environmental, social,

and governance (ESG) disclosures (Aggarwal and Singh, 2018).

The aforementioned studies that use text mining tools for analyzing sustainability reports are

limited to finding common themes, topics, and tones in sustainability reports. Our work uses

automated text mining and bigram analysis to analyze the focus of Fortune 500 companies on various

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

420

dimensions of sustainability. Therefore, our contribution is twofold: Using automated text mining and

bigram analysis; and developing a framework to compare Fortune 500 companies on four dimensions

of sustainability with help of the EESG (Economic, Environmental, Social, Government) framework

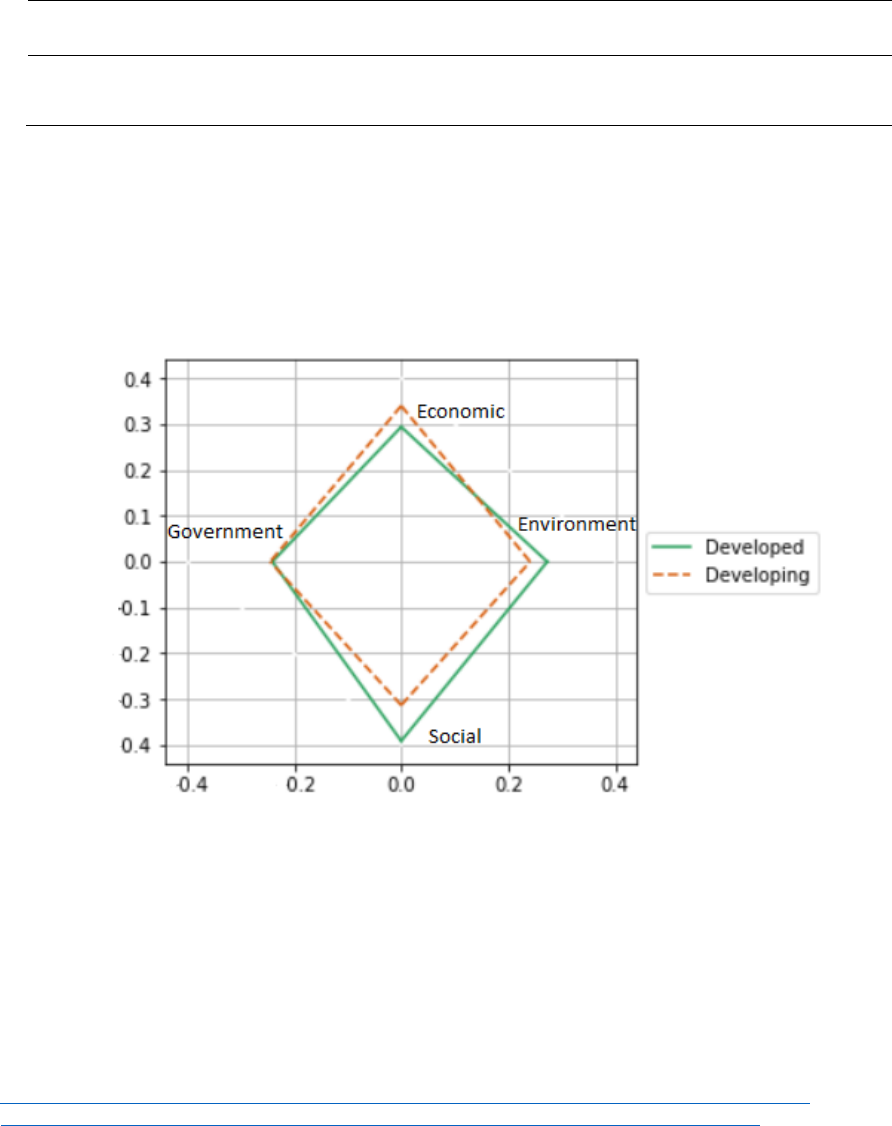

proposed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. EESG Framework for Four Dimensions of Sustainability

METHODOLOGY

To explore the sustainability reports of corporations worldwide, this study utilized the sustainability

reports of Fortune 500 companies in 2019. A sustainability report for each company was searched on

the web. Companies for which the 2019 report was not available, the sustainability report for the year

2018 was considered. For most Chinese and Korean companies, sustainability reports are not available

in English. The reports for these companies were not considered in further analyses. Overall, the

authors found sustainability reports for 395 companies out of Fortune 500 companies in the English

language. All sustainability reports were converted to a suitable format (txt format) for text mining

using custom code developed in Python 3.7.

As the research was conducted in the year 2020, the most recently available data, that is, for the

year 2019, were taken. Moreover, the authors wanted to avoid 2020 and 2021, as both of these years

were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, the focus shifted to certain

dimensions of sustainability. For example, emissions were temporarily reduced because of the

slowdown in economic activity imposed by the lockdowns. Such situations would not have resulted in

estimating a true picture of the disclosures, and it may have failed to assess the long-term impact of

sustainability disclosures. In addition, 2019 witnessed a surge in regulatory requirements in various

parts of the world. For instance, the Securities and Exchange Board of India extended the business

responsibility reporting requirements from the top 500 to the top 1000 listed companies in 2019.

Similarly, the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited amended the requirements for ESG reporting to

shift focus from mere reporting to the board of directors’ role in managing ESG-related aspects.

Similarly, NASDAQ and the Athens Stock Exchange strengthened their ESG reporting requirements.

The UK is legally committed to net zero by 2050, becoming the first major economy in the

world(KPMG, 2020).

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

421

The primary objective of this research was to compare sustainability reports on four dimensions of

sustainability: social, economic, environmental, and government. The authors generated a list of

keywords representing each dimension, based on a review of the extant literature on sustainability.

To identify other related keywords for each dimension, this study performed content analysis of

sustainability reports and backward snowballing using studies from the initial literature review. Hence,

the initial list was further refined by extracting important bigrams from the sustainability reports after

performing a bigram analysis using a bigram tokenizer implemented in Python 3.7. Initially, we

generated the top 1000 most frequent bigrams from all sustainability reports and manually examined

each bigram. If the bigram was relevant and related to one of the four dimensions, it was added to the

keyword list of that dimension. This step yielded four lists of 69, 69, 32, and 34 words representing

each dimension, namely environmental, social, economic, and governmental, respectively. Table 1 lists

the keywords extracted from the literature for each dimension. Similarly, a few sample bigram words

for each dimension are listed in Table 2. The reader may take a note that in a bigram, two words are

separated by ‘_’.

Table 1. List of Keywords Extracted from Literature

Dimension

Keywords

Environmental

environment, emission, pollution, co2, carbon, green, green-energy, solar, wind

power, responsible, deforestation, renewable, eco-friendly, ground water level,

sustainability

Social

social, responsible, community, human, safety, society, living standard, health

support, donation, contribution (not profit), ngo

Economic

profit, revenue, sales, cost, margin, market, segment, customer, promotion,

price, money, economic, loss, production, units, target

Government

regulations, policy, rule, compliance, amendment, restrictions, relaxation,

penalty, permission, law, restrictions, cap, government

Table 2. Sample Bigrams for Various Dimensions of Sustainability Extracted from Sustainability Reports

Environmental

(69 words)

Social

(69 words)

Economic

(32 words)

Government

(33 words)

climate_change

social_responsibility

energy_efficiency

audit_committee

environmental_protection

health_safety

carbon_economy

audit_supervisory

clean_energy

poverty_alleviation

technological_innovation

ethics_compliance

carbon_footprint

respect_human

zero_waste

internal_audit

environmental_footprint

social_governance

reduce_waste

code_ethics

wind_power

safety_health

technology_innovation

supervisory_committee

water_consumption

gender_equality

technology_development

ethics_integrity

food_waste

food_safety

development_sustainable

legal_compliance

emission_reduction

community_development

energy_waste

environmental_compliance

energy_conservation

socially_responsible

waste_reduction

regulatory_compliance

reduce_carbon

public_welfare

open_innovation

governance_code

solar_power

human_labor

sustainable_supply

ethical_conduct

hazardous_waste

occupational_safety

fair_trade

committee_audit

global_warm

inclusion_diversity

fuel_efficiency

compliance_committee

environmentally_friendly

child_labor

drive_innovation

governance_ethics

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

422

After creating the keyword lists for each dimension, the dimensionality reduction technique and

cosine similarity method were deployed to compute the similarity score of each report for all four

dimensions of sustainability. This study uses latent semantic indexing (LSI) (Deerwester et al., 1990)

based on singular value decomposition (Businger and Golub, 1969; Golub and Reinsch, 1971) to map

the semantic structure of sustainability reports from a high-dimensional vector space model to a low-

dimensional representation. This study first converted all sustainability reports into a matrix of terms

by document. This term-document matrix X was decomposed by Singular Vector Decomposition (SVD)

to analyze the semantic association among terms in the collection of sustainability reports. We used

the term frequency-inverse document frequency (a standard method used in information retrieval

research) to identify the weights of the terms (Turney, 2001). Matrix X of rank p was decomposed into

a product of three matrices, U, L, and A, which are called the linearly independent components of X.

X= ULA

T

where the matrices U and A have a unit length with orthonormal columns (and are called singular

vectors), and matrix L is a diagonal matrix (and is called singular values) of the same rank (p) as X. Most

of the singular values are very small and may be removed to retrieve a new matrix X' with rank k (k <

p) that best approximates X.

X'= U

k

L

k

A

k

T

where the matrix L

k

is the resultant matrix after removing (p-k) diagonal nonsignificant singular values.

To remain consistent, we removed the corresponding entries from matrices U and A to retrieve U

k

and

A

k

, respectively. In this way, we map all sustainability reports to this “compressed version” of the

vector space model.

To identify the similarity of these reports with the vector of the keyword list representing each

dimension, we converted each keyword list into a vector of dimension k using the fold-in method

(Adelman and Simina, 2004; Berry et al., 1995) of LSI. In this way, we converted each sustainability

report into a vector of dimension k and each sustainability dimension (social, economic,

environmental, and government) into vectors of dimension k. Finally, to assess the similarity between

a particular sustainability report of a company and the four sustainability dimensions, we estimated

cosine similarity (Han et al., 2012). We used the final cosine values as similarity scores to represent the

focus of a report on various dimensions of sustainability.

RESULTS

In this section, we analyze the results to explain the impact of various countries’ characteristics on

firms’ focus on various dimensions of sustainability. First, we explored the effect of the level of

development of the originating country on the scores of various sustainability dimensions. Further, we

explore the effects of firm size and age in the Fortune 500 list on sustainability disclosure across

various dimensions. Finally, the Results section concludes by exploring interesting sustainability

disclosure patterns across companies and industry sectors.

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

1

https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_current/2014wesp_country_classification.pdf

2

https://epic.uchicago.edu/news/why-environmental-quality-is-poor-in-developing-countries-a-primer/

423

IMPACT OF THE LEVEL OF DEVELOPMENT

We segregated countries into two types – developing and developed – based on the report “World

Economic Situation and Prospects 2014” by the UN

1

. Table 3 presents the average scores for these

countries on various dimensions of sustainability.

Table 3. Comparison Between Firms from Developed and Developing Countries

Country of

Origin

No. of

Firms

Social

Environmental

Economic

Government

Developed

318

0.391

0.273

0.294

0.241

Developing

77

0.313

0.241

0.340

0.245

Figure 2 graphically represents the scores (Table 3) for firms in developed and developing countries.

We can observe from Figure 2 that for developed countries, the highest focus is on the social

dimension, whereas for developing countries, the highest focus is on the economic dimension. This is

justifiable from the fact that developed countries have already achieved economic sustainability and

have focused more on social aspects. We also find that, for developing countries, the environmental

dimension is the least focused one. This section is discussed in detail in the media

2

.

Figure 2. Comparison Between Firms Belonging to Developing and Developed Countries

We can observe from Figure 2 that the focus of firms in developed countries is skewed toward the

social dimension only. However, in developing countries, the focus is skewed toward economic and

social dimensions. Moreover, in the government/regulation dimension, firms in developing and

developed countries seem similar in terms of their focus.

To further understand the differences between firms in developed and developing countries, we

ran an independent samples t-test. Table 4 presents the results. The table shows that, except for the

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

424

government/regulation dimension, firms in developed and developing countries differ in their level of

focus on various dimensions of sustainability. This is also in line with the inferences from Figure 2.

Table 4. Comparison Between Developed and Developing Countries

Feature/Dimension

Developed-

Developing

Lower

Upper

p-value

Environmental

0.03

-0.001

0.07

0.06

Economic

-0.05

-0.08

-0.01

0.01

Government

-0.004

-0.04

0.03

0.81

Social

0.08

0.03

0.12

0.00

IMPACT OF FIRM CHARACTERISTICS

In this subsection, we analyze the impact of firm characteristics, such as size (with respect to the

number of employees) and age (duration for which it is part of the Fortune 500 list), on their relative

scores on the four dimensions. We can observe from Table 5 and Figure 3 that irrespective of firm size,

their scores on the economic dimension are similar. However, firms with fewer than 50,000 employees

do better than other firms in the remaining three dimensions (environmental, social, and

government). This implies that it is easier for smaller firms to manage other than the economic

dimensions of sustainability. Firms with more than 50,000 employees have a similar environmental

score, but firms in the size range 50,000–200,000 have a better score on social dimensions. This again

signifies the difficulty in managing social issues in a larger organization.

Table 5. Comparison of Sustainability Dimensions with Respect to Firm Size

Firm Size

Social

Environmental

Economic

Government

Below 50000

0.401

0.288

0.294

0.248

Between 50 K

and 200K

0.373 0.257 0.308 0.243

Above 200K

0.346

0.261

0.303

0.229

Figure 3. Comparison of Sustainability Dimensions with Respect to Firm Size

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

425

The samples t-test results presented in Table 6 confirm our earlier findings that firms larger than

200,000 (high) are significantly different from the other two categories. Moreover, firms below

50,000 (low and medium) do not differ from each other.

Table 6. Comparison of Social Score for Firms with Different Size

Size Pairs

Difference

Lower

Upper

p-value

Medium -Low

-0.03

-0.01

0.04

0.31

High-Low

-0.06

-0.11

0.00

0.08

High-Medium

-0.03

-0.05

0.001

0.07

We can observe from Table 7 and Figure 4 that the duration for which firms are part of the Fortune

500 list does not impact their score on the economic, environmental, and government fronts.

However, firms with more than 20 years of experience on the Fortune list perform better on social

scores than the rest. This finding, along with the finding with respect to size, indicates the sequence

in which firms focus on the various dimensions of sustainability. Firms justifiably focus first on the

economic dimension, followed by environmental and government regulations. The social dimension

appears to be the last dimension to focus on.

Table 7. Sustainability Dimension Scores with Respect to Firm’s tenure on Fortune 500 List

Years on Fortune 500 List

Social

Environmental

Economic

Government

Less than 10 years

0.347

0.257

0.314

0.236

Between 10 to 20

0.361

0.261

0.308

0.236

More than 20 years

0.395

0.273

0.296

0.247

Figure 4. Comparison of Sustainability Scores with Respect to Firm’s Tenure on Fortune 500 List

From Table 8, we observe that firms less than 10 years old (0 decade) and firms between 10 and 20

years old (1 decade) do not differ from each other. Similarly, 1-decade type firms are not different from

firms with more than 20 years (2 decade) on the Fortune list. However, the 0-decade firms are

significantly different from the 2-decade firms. This indicates that the transformation in these four

dimensions was a relatively slow process, and differences were observed only after a couple of

decades.

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

426

Table 8. Comparison of Social Scores Among Firms with Different Tenure on Fortune 500 list

Duration Pairs

Difference

Lower

Upper

p-value

1 decade- 0 decade

0.01

-0.05

0.07

0.85

2 decade- 0 decade

0.05

-0.01

0.10

0.09

2 decade- 1 decade

0.03

-0.02

0.08

0.25

ALIGNMENT BETWEEN COUNTRIES

We explored the similarity between the top-15 countries from the Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

perspective to assess the alignment between countries on different dimensions of sustainability. We

performed a community-based network analysis for this comparison. Network analysis is an

established method for developing relational interpretation of a community-based network to yield

additional insights regarding network properties (Lin et al., 2015; Maya-Jariego and Holgado, 2015). As

a part of the community-based network analysis, we obtain hubs, authorities, and communities of the

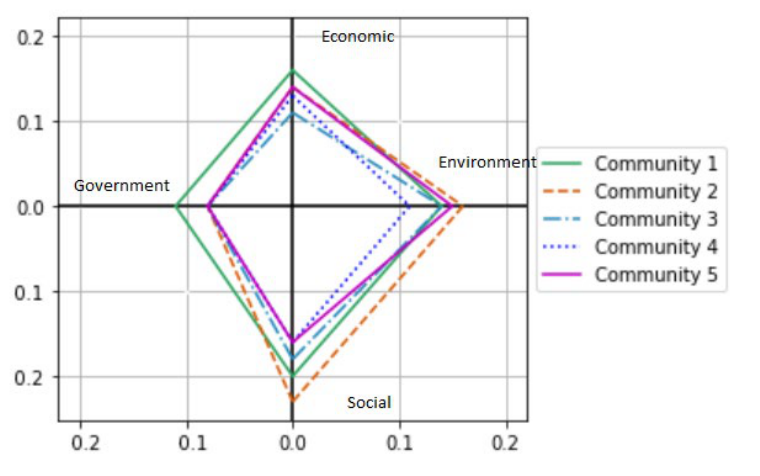

top-15 countries based on GDP. The hub and authority graphs are shown in Figure 5. From the

community detection graph presented in Figure 5, we observe three communities in each country.

Figure 5. Community Detection Graph for Top-15 GDP Countries

The first community is formed by countries such as China, India, the UK, and the USA, with South

Korea overlapping Communities 1 and 2. The presence of China, India, and South Korea in the same

community is justifiable because of the development path and commonly understood similarities

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

3

https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/articles/challenges-implementing-sustainable-development-goals-asia

427

based on dimensions such as environmental, economic, social, and government

3

. Firms in these

countries have relatively low scores for the environmental, economic, and government dimensions of

sustainability. Surprisingly, countries such as the UK and USA are in the same community.

Nevertheless, from Table 9, we can observe that China, India, and South Korea score lower than the

USA and UK on the environmental dimension.

The second community consisted of Australia, Brazil, Japan, Mexico, and South Korea. We can

observe from Table 9 that firms in Japan have better environmental dimension scores than firms

belonging to other countries in Community 2. Similarly, firms in Brazil are relatively better than other

firms in Community 2. The aforementioned observations of Japan and Brazil from Table 9 are

identifiable from the location of these two countries in the community detection graph shown in

Figure 5.

Table 9. Comparison of Top-15 GDP Countries on Sustainability Dimensions

Country

Social

Environmental

Economic

Government

Community

US

0.361

0.262

0.235

0.214

1

China

0.249

0.231

0.317

0.203

1

India

0.344

0.203

0.303

0.262

1

United

Kingdom

0.403 0.275 0.315 0.171 1

South Korea

0.421

0.236

0.361

0.227

1, 2

Japan

0.483

0.271

0.286

0.27

2

Brazil

0.499

0.217

0.415

0.345

2

Australia

0.489

0.212

0.282

0.297

2

Mexico

0.442

0.252

0.335

0.244

2

Germany

0.325

0.304

0.339

0.306

3

France

0.381

0.314

0.362

0.249

3

Italy

0.34

0.287

0.445

0.295

3

Canada

0.469

0.371

0.229

0.279

3

Russia

0.31

0.248

0.579

0.404

3

Spain

0.39

0.296

0.396

0.344

3

Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Russia formed a third community. It is intuitive that

European countries, such as France, Germany, Italy, and Spain, are part of the same community

because of the similarity in their geographical, economic, and shared regulation practices. In certain

ways, the presence of Russia in the cluster could also be explained, as Russia shares some of the

aforementioned aspects. However, the presence of Canada in the same community is counterintuitive

because of differences in policies and initiatives on sustainability. Nevertheless, we can observe from

Figure 5 that Canada is relatively distant from the other countries in Community 3. Moreover, Table 9

shows that the scores of firms in Canada on the environmental, economic, and social dimensions are

quite distinct from those of other firms in the same community.

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

428

From Figure 6, it is evident that countries in Community 1 have lower government scores than

countries in Communities 2 and 3. To determine if this is statistically true, a t-test was conducted, with

the results shown in Table 10.

Figure 6. Alignment Among Communities with Respect to Countries

Table 10. Comparison of Government Score Among Various Country Communities

Community Pairs

Difference

Lower

Upper

p-value

Community 2-1

0.06

0.02

0.11

0.00

Community 3-1

0.09

0.05

0.13

0.00

Community 3-2

0.02

-0.03

0.07

0.72

Similarly, another interesting insight from Figure 6 is that social scores for countries in Community

2 are higher than those in the other two communities. To determine if this is statistically true, a t-test

was conducted, with the results shown in Table 11.

Table 11. Comparison of Social Score Among Various Country Communities

Community Pairs

Difference

Lower

Upper

p-value

Community 2-1

0.14

0.08

0.20

0.00

Community 2-3

0.11

0.05

0.18

0.00

Community 3-1

0.02

-0.03

0.08

0.51

From Figure 6, we can also see that Community 3 has a higher environmental score than the other

two communities. To determine if this is statistically true, a t-test was conducted, with the results

shown in Table 12.

Table 12. Comparison of Environmental Score Among Various Country Communities

Community Pairs

Difference

Lower

Upper

p-value

Community 3-1

0.06

0.01

0.10

0.00

Community 3-2

0.05

0.00

0.11

0.05

Community 2-1

0.01

-0.04

0.05

0.96

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

429

ALIGNMENT BETWEEN SECTORS

In this section, we apply community-based network analysis to visualize the alignment among

different business sectors. We can observe from the community detection graph shown in Figure 7

that five distinct communities are formed based on the sectors.

Figure 7. Community Detection Graph for Various Industry Sectors

The first community is represented by firms in the energy, motor vehicles and parts, wholesalers,

and chemical sectors. It is intuitive that firms in the chemical, energy, and motor sectors fall into the

same community because of the intensive raw material requirements and emissions during the

manufacturing process. However, the presence of a wholesale sector in the same community is

counterintuitive. Nevertheless, close observation of Table 13 reveals that wholesalers seem to be

different from the rest of the firms in the community in the economic dimension. The same can be

observed in the community detection graph presented in Figure 7. Unexpectedly, in the environmental

dimension, firms in the wholesale sector scored lower than firms in the energy sector, while they

scored higher than firms in the motor and chemical sectors. For a long time, energy sector firms

(mostly thermal power-based) have been known to have high environmental emissions and take

various steps, including switching to renewable energy sources. On the other hand, environmental

issues related to the auto and chemical sectors have not received much attention in the past, and

green initiatives in these sectors are a relatively recent phenomenon. Therefore, different stages of

green focus for these sectors could explain the aforementioned counterintuitive finding. Firms are

distinct from each other, except for firms in Communities 4 and 5, which appear to be similar.

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

430

Table 13. Comparison of Various Sectors on Sustainability Dimensions

The second community consisted of food and drug stores, retail, engineering, and construction

sectors. The presence of firms in food and drug stores and retail sectors in the same community is

expected; however, the inclusion of firms in the engineering and construction sectors is unexpected.

However, we can observe from Table 6 that engineering and construction share similarities with other

firms in the community on the economic and environmental dimensions, and therefore explain the

inclusion of these three sectors in the same community. Moreover, the wholesale sector is not far from

food and drug stores and retail, even though it is in a different community (Figure 7). This closeness is

justified because wholesale, food and drug stores, and retail are non-manufacturing sectors and have

similar business characteristics.

The financial, technological, aerospace, and defense sectors form a third community. Table 13

shows that firms in these three sectors are similar in all dimensions. However, they are relatively

dissimilar on the environmental front, and technology firms have a higher score than firms in the other

two sectors.

The fifth community comprises sectors such as healthcare, food, beverages and tobacco,

telecommunications, industries, and materials organized into one community. All four sectors except

the telecommunications sector require raw materials, and they are relatively more productive sectors

than services.

Healthcare is predominantly a service but requires material management for medicine and other

medical supplies. Therefore, the presence of materials, industrial, food, beverages and tobacco, and

healthcare in the same sector is justifiable. However, the presence of telecommunications is

counterintuitive, but we can observe from Table 13 that firms in the telecommunication sector are

different from other firms in the community in terms of social and government dimensions. Moreover,

the position of telecommunications in Figure 7 also indicates that it is different from other firms in the

Sector

Social

Environmental

Economic

Government

Group

Energy

0.20

0.16

0.17

0.10

1

Motor Vehicles & Parts

0.20

0.12

0.16

0.13

1

Wholesalers

0.22

0.14

0.12

0.12

1

Chemicals

0.19

0.12

0.17

0.08

1

Food & Drug Stores

0.21

0.16

0.12

0.08

2

Retailing

0.22

0.17

0.15

0.07

2

Engineering & Construction

0.25

0.15

0.15

0.08

2

Financials

0.17

0.14

0.11

0.09

3

Technology

0.19

0.16

0.12

0.08

3

Aerospace & Defence

0.18

0.13

0.10

0.08

3

Health Care

0.16

0.09

0.12

0.09

4

Food, Beverages & Tobacco

0.16

0.12

0.14

0.09

4

Telecommunications

0.19

0.12

0.13

0.05

4

Industrials

0.16

0.10

0.12

0.10

4

Materials

0.15

0.11

0.14

0.07

4

Transportation

0.16

0.15

0.14

0.08

5

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

431

community.

Further investigations of these communities reveal that sectors in Community 1 have higher scores

for social and economic dimensions, and sectors in Community 2 have a higher score for social and

environmental dimensions. Community 3 (financial, technology, aerospace, and defense sectors) has

a lower score for economic and social dimensions. Sectors in Community 4 had lower environmental

and social scores. Community 5 had a moderate social score and a lower score for the environmental

dimension.

Figure 8 depicts the alignment among various communities of sectors on sustainability dimensions.

From Figure 8, we can observe that in the environmental dimension, all communities except

Community 5 are similar. Similarly, in the government dimension, all sectors except Community 1 are

similar. However, in the social dimension, all communities are different from each other.

Figure 8. Alignment Among Communities Based on Industry Sectors

Figure 8 shows that sectors in Community 1 have higher scores for the government than that for

other communities. However, we could not find a statistical difference in the government scores for

various communities of sectors. Another striking observation is the low score for the environment

dimension of Community 4 compared with other communities. Table 14 provides the statistical

differences in the environmental scores for Community 4 compared with other communities.

Companies belonging to sectors in Community 4 had significantly lower environmental scores than

those belonging to sectors in Communities 1, 2, and 3. Thus, sectors such as materials, healthcare,

telecommunications, and industries have a lower score on the environmental dimension than other

sectors.

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

432

Table 14. Comparison of Environmental Score Among Various Sector Communities

Community Pairs

Difference

Lower

Upper

p-value

Community 4-1

-0.07

-0.12

-0.01

0.01

Community 4-2

-0.09

-0.17

-0.01

0.01

Community 4-3

-0.06

-0.11

-0.01

0.01

Community 4-5

-0.07

-0.17

0.03

0.26

DISCUSSION

In continuation of the research efforts to evaluate corporate sustainability reports, we derived a novel

content analysis methodology to assess the sustainability reports of Fortune 500 companies and

subsequently compared the scores on different dimensions with an emphasis on factors such as level

of development, firm characteristics, sectors, and countrywide analysis.

The developmental status of a country has an impact on various dimensions of sustainability,

except for the government dimension. In comparison, the focus of firms in developed countries is

skewed only toward the social dimension, whereas firms in developing countries are skewed toward

the economic and social dimensions. This is evident from the fact that developed countries have

achieved economic sustenance and, as such, firms in developed countries are focusing more on social

development. By contrast, developing countries have the highest focus on economic dimensions and

the least focus on environmental dimensions. This is in line with the common notion that developing

countries aspire to transform into developed economies, and in the process, the focus on

environmental sustainability is compromised. In a similar context, Farisyi et al., (2022) investigated

sustainability reporting adoption in developing countries and found that lack of training, low level of

expertise, and negative attitudes toward sustainability reporting are significant determinants

affecting the quality of disclosures in developing countries. Bhatia and Tuli (2018) suggested that

developing nations should work more on the quality of sustainability reporting, as sustainability issues

are more pertinent in developing countries than in developed countries.

Many studies have explored the relationship between the size of a company (in terms of revenue)

and the different dimensions of sustainability. Gallo and Christensen (2011) analyzed the effect of firm

size on sustainability-related behavior and found that larger companies report more on sustainability

information, whereas Bergmann and Posch (2018) found that the size of the firm matters only in the

case of mandatory sustainability reporting, while it is not a crucial factor for firms not mandated by

law for sustainability reporting. However, our research did not find a significant impact of the size (in

terms of revenue) on the EESG dimensions. Hence, we analyzed the impact of firms’ characteristics,

such as size (in terms of the number of employees), on their relative scores on the EESG dimensions.

This adds a new perspective to the body of literature with regard to company size and sustainability

disclosures. In comparison, we observed that large firms (more than 200,000 employees) are

significantly different from small (below 50,000) and medium firms (50,000–200,000). We observed

that as company size increased, the score on the social dimension decreased, signifying ignorance of

managing social issues in larger organizations. At the same time, it poses great opportunities for large

organizations to tackle these issues by utilizing employee engagement in CSR activities.

We further observe that the longevity of the firm for which it is part of the Fortune 500 list does

not have much impact on the economic, environmental, and government dimensions. However, as the

number of years on the Fortune 500 list increased, the score on the social dimension also increased.

We also observed that firms below 10 years old (0-decade type) are significantly different from those

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

433

with more than 20 years old (2-decade type), which indicates that the transformation of the EESG

dimensions is a relatively slow process, and differences are observed only after a couple of decades.

When the two dimensions (size and age) are combined, old small firms have a greater focus on the

social dimension, whereas big new firms have a comparatively lesser focus on the social dimension.

This is in line with a study by Badulescu et al., (2018) that observes that newer (young) firms are less

involved in social responsibility actions than older firms that have dedicated departments or people to

manage social responsibility actions. Our findings also aligned with the finding by Prashar (2021), which

found that large and mature firms engage more in sustainability reporting because they have a

comparatively better presence of institutional investors in their corporate board composition.

IMPLICATIONS

As the pandemic was a big setback for sustainable development, it would be interesting to understand

the future trajectories of firms in both developed and developing countries. The Sustainable

Development Report 2021 reveals that sustainable development has been severely impacted by the

COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a downward trend in the global average SDG index score for 2020 since

the adoption of the SDGs in 2015 (Sachs et al., 2021). The United Nations have announced the 2020-30

decade as the Decade of Action, and 17 SDGs have to be achieved by 2030. As part of the Paris Climate

Agreement, the majority of countries have made climate-related commitments, and firms located in

these countries are also increasingly taking net-zero pledges to achieve carbon neutrality

commitments. Against the backdrop of this scenario, the current research provides a framework and

methodology to scrutinize communicated sustainability data with the help of technological

interventions.

THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS

Sustainability reporting frameworks are evolving and will continue to evolve over time (Minutiello and

Tettamanzi, 2021). This necessitates the assessment of the information provided by these frameworks.

At this crucial juncture, the current study provides a technological intervention by developing a novel

content analysis methodology through digitalized means to assess various dimensions of

sustainability. Furthermore, this study contributes to sustainability disclosure research and aligns with

the findings of previous studies by suggesting that there are variations in sustainability reporting with

respect to organizational size, origin, age, and sector (Bergmann and Posch, 2018; Gallo and

Christensen, 2011; Prashar, 2021). The findings and observations from this study may serve as a premise

for future inquiries into the sustainability reporting behavior of firms across the globe. This study adds

a new EESG framework and automated text mining methodology using bigram analysis to the body of

literature to analyze corporate sustainability disclosures. The developed framework and methodology

have wide applications across various sectors and geographies for assessing longitudinal data

pertaining to corporate sustainability.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

This research reveals that there is a lack of a uniform set of standards for disclosing, measuring, and

reporting a company’s progress on various dimensions of sustainability. The need for a globally

recognized standard that integrates all previous standards and frameworks was recognized at the COP

26 summit. In response, the International Sustainability Standards Board is developing a standard for

sustainability reporting similar to the financial reporting standard developed by the International

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

434

Accounting Standards Board (Eccles and Mirchandani, 2022). Toward this end, the present study

would help stakeholders understand the underlying behavior of firms in a variety of contexts with the

robust methodology developed in this study. In particular, it would be helpful to generate insights into

the relative focus of firms on different dimensions of sustainability. Such information would be of

greater interest to regulators and evaluators in taking corrective measures to ensure long-term

impacts and outcomes in maintaining an equitable planet and just society. Community graphs would

particularly be of interest to policymakers in assessing the variation and similarities in reporting

between different countries.

LIMITAIONS AND CONCLUSION

This study has several limitations. First, the present research was restricted to analyzing the

sustainability reports of 395 out of Fortune 500 companies in the English language. Future research

could address this shortcoming by incorporating a large sample and including sustainability reports

written in other prominent international languages. Second, this study generated a list of limited

keywords by reviewing the literature pertaining to different dimensions of sustainability. The

keywords extracted from the literature were subjective in nature. Thus, future research may consider

analyzing other linguistic versions of sustainability reports using the automated text mining

methodology applied in the current study. In addition to limiting the analysis to keywords and bigrams,

future studies may also incorporate semantic analyses to extract deeper trends and patterns from

sustainability reports. Third, this study leverages the state-of-the-art LSI technique to project reports

to vectors. Future studies may utilize the latest advancements in natural language processing, such as

word embeddings and text encoders, for the effective analysis of sustainability reports.

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

435

REFERENCES

Abbott, W. F. & Monsen, R. J. (1979). On the measurement of Corporate Social Responsibility: Self-

Reported Disclosures as a Method of Measuring Corporate Social Involvement. Academy of

Management Journal, 22(3), 501-515.

Adelman, N. & Simina, M. (2004). Adapting LSI for Fine-Grained and Multi-Level Document

Comparison. American Association for Artificial Intelligence, 1, 141–146.

Adler, R., Mansi, M., & Pandey, R. (2018). Biodiversity and Threatened Species Reporting by the Top

Fortune Global Companies. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal. 31 (3), 787-825.

Aggarwal, P. & Singh, A. K. (2018). CSR and Sustainability Reporting Practices in India: An In-Depth

Content Analysis of Top-Listed Companies. Social Responsibility Journal. 15(8), 1033-1053.

Amini, M., Bienstock, C. C., & Narcum, J. A. (2018). Status of Corporate Sustainability: A Content

Analysis of Fortune 500 Companies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1450-1461.

Ardiana, P. A. (2021). Stakeholder Engagement in sustainability Reporting by Fortune Global 500

Companies: A Call for Embeddedness. Meditari Accountancy Research.

Badulescu, A., Badulescu, D., Saveanu, T., & Hatos, R. (2018). The Relationship Between Firm Size and

Age, and Its Social Responsibility Actions—Focus on a Developing Country (Romania).

Sustainability, 10(3), 805.

Bergmann, A. & Posch, P. (2018). Mandatory Sustainability Reporting in Germany: Does Size Matter?

Sustainability, 3904.

Berry, M. W., Dumais, S. T., & Letsche, T. A. (1995, December). Computational Methods for Intelligent

Information Access. In Proceedings of the 1995 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing (p. 20).

Bhatia, A. & Tuli, S. (2018). Sustainability Reporting: An Empirical Evaluation of Emerging and

Developed Economies. Journal of Global Responsibility, 9(2), 207-234.

Buallay, A. (2019). Is Sustainability Reporting (ESG) Associated with Performance? Evidence from the

European Banking Sector. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal,

30(1), 98-115.

Businger, P. A. & Golub, G. H. (1969). Algorithm 358: Singular Value Decomposition of a Complex Matrix

[f1, 4, 5]. Communications of the ACM, 12(10), 564-565.

Cicchiello, A. F., Alicia, G., Kazemikhasragh A., & Eva, P. (2022). Company Characteristics and

Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from Asia and Africa. International Journal of Social Ecology

and Sustainable Development, 13, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJSESD.290309.

Dahlmann, F. & Bullock, G. (2020). Nexus Thinking in Business: Analysing Corporate Responses to

Interconnected Global Sustainability Challenges. Environmental Science & Policy, 107, 90-98.

Daub, C. H. (2007). Assessing the Quality of Sustainability Reporting: An Alternative Methodological

Approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 15(1), 75-85.

Dauvergne, P. & Lister, J. (2012). Big Brand Sustainability: Governance Prospects and Environmental

Limits. Global Environmental Change, 22(1), 36-45.

Deerwester, S., Dumais, S. T., Furnas, G. W., Landauer, T. K., & Harshman, R. (1990). Indexing by Latent

Semantic Analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 41(6), 391-407.

Eccles, R. G. & Mirchandani, B. (2022, February 15). We Need Universal ESG Accounting Standards.

Harvard Business Review.

Elkington, J. (2018). 25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” Here’s Why It’s Time to

Rethink It. Harvard business review, 25, 2-5.

Farisyi, S., Musadieq, M., Utami, H., & Damayanti, C. (2022). A Systematic Literature Review:

Determinants of Sustainability Reporting in Developing Countries. Sustainability, 14(16), 10222.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610222.

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

436

Gallo, P. J. & Christensen, L. J. (2011). Firm Size Matters: An Empirical Investigation of Organizational

Size and Ownership on Sustainability-Related Behaviors. Business & Society, 50(2), 315-349.

Girón, A., Kazemikhasragh, A., Cicchiello, A. F., & Panetti, E. (2021). Sustainability Reporting and Firms’

Economic Performance: Evidence from Asia and Africa. Journal of the Knowledge Economy,

12(4), 1741-1759.

Golub, G. H. & Reinsch, C. (1971). Singular Value Decomposition and Least Squares Solutions. In

Handbook for Automatic Computation. Die Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften,

vol 186. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-86940-2_10.

Haidar, H. M., Sohail, R. M., & Al Qurashi, S. M. (2021). Emerging Trends in Sustainability Reporting (SR):

Comparative Literature Review in Developed, Developing and GCC Countries. Open Journal of

Business and Management, 2697-2718.

Hahn, R. & Kühnen, M. (2013). Determinants of Sustainability Reporting: A Review of Results, Trends,

Theory, and Opportunities in an Expanding Field of Research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 5-

21.

Han, J., Kamber, M., & Pei, J. (2012). Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques. Scopus.

https://doi.org/10.1016/C2009-0-61819-5.

Harymawan, I., Nasih, M., Ratri, M. C., Soeprajitno, R. R. W. N., & Shafie, R. (2020). Sentiment Analysis

Trend on Sustainability Reporting in Indonesia: Evidence from Construction Industry. Journal

of Security and Sustainability Issues, 9(3), 1017-1024.

Hongming, X., Ahmed, B., Hussain, A., Rehman, A., Ullah, I., & Khan, F. U. (2020). Sustainability

Reporting and Firm Performance: The Demonstration of Pakistani Firms. SAGE Open, 10(3), 1-

12.

Jose, A. & Lee, S. M. (2007). Environmental reporting of global corporations: A Content Analysis Based

on Website Disclosures. Journal of Business Ethics, 72(4), 307-321.

Kazemikhasragh, A., Cicchiello, A. F., & Pietronudo, M. C. (2021). Factors Influencing the Adoption of

SDG Reporting by Large African and Asian Companies. International Journal of Technology

Management & Sustainable Development, 43-60.

Klymenko, O. & Lillebrygfjeld Halse, L. (2021). Sustainability Practices During COVID-19: An Institutional

Perspective. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 33(4), 1315-1335.

Kolk, A. (2003). Trends in Sustainability Reporting by the Fortune Global 250. Business Strategy and the

Environment, 12(5), 279-291.

KPMG. (2020). The Time Has Come: The KPMG Survey of Sustainability Reporting 2020. KPMG.

Kumar, K. & Prakash, A. (2019). Examination of Sustainability Reporting Practices in Indian Banking

Sector. Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility, 4(1), 1-16.

Kumar, P., Sharma, D., & Pandey, P. (2022). Industry 4.0 (I4. 0) Based Virtual Organization Model for

the Coordination of Sustainable Textile Supply Chain. American Business Review, 25(1), 10.

Lorenzoni, I. & Benson, D. (2014). Radical Institutional Change in Environmental Governance:

Explaining the Origins of the UK Climate Change Act 2008 Through Discursive and Streams

Perspectives. Global Environmental Change, 29, 10-21.

Lin, C. C., Kang, J. R., & Chen, J. Y. (2015). An Integer Programming Approach and Visual Analysis for

Detecting Hierarchical Community Structures in Social Networks. Information Sciences, 299,

296-311.

Linnenluecke, M. K. & Griffiths, A. (2013). Firms and Sustainability: Mapping the Intellectual Origins and

Structure of the Corporate Sustainability Field. Global Environmental Change, 23(1), 382-391.

Loh, L., Thomas, T., & Wang, Y. (2017). Sustainability Reporting and Firm Value: Evidence from

Singapore-listed Companies. Sustainability, 9(11), 2112.

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

437

Lyon, T. P., Delmas, M. A., Maxwell, J. W., Bansal, P., Chiroleu-Assouline, M., Crifo, P., ... & Wijen, F.

(2018). CSR Needs CPR: Corporate Sustainability and Politics. California Management Review,

60(4), 5-24.

Mahmood, M. & Orazalin, N. (2017). Green Governance and Sustainability Reporting in Kazakhstan's

Oil, Gas, and Mining Sector: Evidence from a Former USSR Emerging Economy. Journal of

Cleaner Production, 164, 389-397.

Maya-Jariego, I. & Holgado, D. (2015). Network Analysis for Social and Community Interventions.

Psychosocial Intervention, 24(3), 121-124.

Minutiello, V. & Tettamanzi, P. (2021). The Quality of Nonfinancial Voluntary Disclosure: A Systematic

Literature Network Analysis on Sustainability Reporting and Integrated Reporting. Corporate

Social Responsibility and Environmental Management.

Morhardt, J. E., Baird, S., & Freeman, K. (2002). Scoring Corporate Environmental and Sustainability

Reports Using GRI 2000, ISO 14031 and Other Criteria. Corporate Social Responsibility and

Environmental Management, 9(4), 215-233.

Morhardt, J. E. (2010). Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting on the Internet.

Business Strategy and the Environment, 19(7), 436-452.

OCED (2001), Policies to Enhance Sustainable Development. Meeting of the OCED Council at Minister

Level 2001, retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/1869800.pdf.

Perkiss, S., Anastasiadis, S., Bayerlein, L., Dean, B., Jun, H., Acosta, P., ... & Gibbons, B. (2020).

Advancing Sustainability Education in Business Studies Through Digital Service Learning.

American Business Review, 23(2), 283-299.

Prashar, A. (2021). Moderating Effects on Sustainability Reporting and Firm Performance

Relationships: A Meta-Analytical Review. International Journal of Productivity and Performance

Management.

Purvis, B., Mao, Y., & Robinson, D. (2019). Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual

Origins. Sustainability Science, 14(3), 681-695.

Raquiba, H. & Ishak, Z. (2020). Sustainability Reporting Practices in the Energy Sector of Bangladesh.

International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 10(1), 508.

Rasmussen, L. V., Bierbaum, R., Oldekop, J. A., & Agrawal, A. (2017). Bridging the Practitioner-

Researcher Divide: Indicators to Track Environmental, Economic, and Sociocultural

Sustainability of Agricultural Commodity Production. Global Environmental Change, 42, 33-46.

Roberts, M. (2021, November 1). The 'S' in ESG and What It Truly Means for Corporate Sustainability.

Business Think.

Sachs, J., Kroll, C., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G., & Woelm, F. (2021). The Decade of Action for the Sustainable

Development Goals: Sustainable Development Report 2021. Published online at sdgindex.org,

Cambridge. Retrieved from: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/.

Schreck, P. & Raithel, S. (2018). Corporate Social Performance, Firm Size, and Organizational Visibility:

Distinct and Joint Effects on Voluntary Sustainability Reporting. Business & Society, 57(4), 742-

778.

Skouloudis, A. & Evangelinos, K. I. (2009). Sustainability Reporting in Greece: Are We There Yet?

Environmental Quality Management, 19(1), 43-60.

Subbaraman, N., (2022), Carbon-Dioxide Level in Atmosphere Hits Historical High. The Wall Street

Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/carbon-dioxide-level-in-atmosphere-hits-historical-high-

11651777260?mod=Searchresults_pos7&page=1.

Székely, N. & Vom Brocke, J. (2017). What Can We Learn from Corporate Sustainability Reporting?

Deriving Propositions for Research and Practice from Over 9,500 Corporate Sustainability

Reports Published Between 1999 and 2015 Using Topic Modelling Technique. PloS One, 12(4),

e0174807.

A. Sharma, K. Kaushik, P. Awasthy and A. Gawande American Business Review 25(2)

__________________________________________________

438

Turney, P. D. (2001, September). Mining the Web for Synonyms: PMI-IR Versus LSA on TOEFL. In

European Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 491-502). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

UNDP Annual Report (2021), United Nations Development Program Annual Report 2021, retrieved from:

https://www.undp.org/publications/undp-annual-report-2021.

Vormedal, I. & Ruud, A. (2009). Sustainability Reporting in Norway–An Assessment of Performance in

the Context of Legal Demands and Socio-Political Drivers. Business Strategy and the

Environment, 18(4), 207-222.

Yadava, R. N. & Sinha, B. (2016). Scoring Sustainability Reports Using GRI 2011 Guidelines for Assessing

Environmental, Economic, and Social Dimensions of Leading Public and Private Indian

Companies. Journal of Business Ethics, 138(3), 549-558.

Zhang, L., Zhao, S., Cui, L., & Wu, L. (2020). Exploring Green Innovation Practices: Content Analysis of

the Fortune Global 500 Companies. SAGE Open, 10(1), 1-13.