6

e Taft Proposal of 1946 s the

(Non-) Making of American

Fair Employment Law

David Freeman Engrom

F

the

evolution of American fair em-

ployment law, the years clustered

around provide the most obvious

opportunities to identify so-called “critical

junctures” – those hinge moments in history

when a number of different pathways of le-

gal or political development remain open. It

was during this period that federal appeals

courts approved class-action lawsuits under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of , and

that the Supreme Court’s Griggs¹ decision

sanctioned a “disparate impact” standard, al-

lowing plaintiffs to prove job discrimination

with something less than concrete evidence

of discriminatory intent.² It was also around

then that the Nixon Administration imple-

mented the so-called “Philadelphia Plan,”

prescribing “goals and timetables” for hiring

minority workers by contractors bidding

on federally assisted construction projects.³

Together, these developments transformed

federal fair employment law from the “poor,

enfeebled thing” that had emerged from the

legislative compromises of into a potent

set of anti-discrimination policies.⁴

David Engstrom is an associate, Kellogg, Huber, Hansen, Todd, Evans s Figel, P.L.L.C. is piece draws

on the author’s Ph.D. dissertation, titled “e Lost Origins of American Fair Employment Law: State Fair

Employment Practices Bureaus and the Politics of Regulatory Design, 1943–1964.” e author gratefully ac-

knowledges the support of the John M. Olin Program in Law, Economics, and Public Policy at Yale Law

School during 2004–2005.

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., U.S. ().

See, e.g., John Donohue III s Peter Siegelman, e Changing Nature of Employment Discrimination

Litigation, S. L. R. (); A M. B, M L: T L T-

S E E O ().

See omas J. Sugrue, Affirmative Action from Below: Civil Rights, the Building Trades, and the Politics

of Racial Equality in the Urban North, 1945–1969, J. A. H. (); Paul Frymer s John Da-

vid Skrentny, Coalition-Building and the Politics of Electoral Capture During the Nixon Administration:

African-Americans, Labor, Latinos, S. A. P. D. (); H D G, T

C R E: O D N P, – –, –

().

e phrase “poor, enfeebled thing” is from M I. S, L R R

D E (), though he was referring to the Equal Employment

182 9 G r e e n Ba g 2 d 181

Davi d Fre eman En gs trom

But few know that the history of Ameri-

can fair employment law reached an equally

critical juncture more than years earlier, in

. It was in May of that year that Repub-

lican Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, perhaps

the leading conservative voice in Congress at

the time, privately approached an emerging

coalition of civil rights, labor, religious, and

civic groups with a draft bill – reproduced

in its entirety at the end of this essay – that

broadly prohibited job discrimination on the

basis of race, creed, color, or national origin

and empowered federal courts to oversee

sweeping injunctive remedies, including the

requirement that employers hire a particular

quota of protected workers.⁵ e stunning

details of that proposal, and its quiet rejection

by the nascent liberal coalition, offer a win-

dow onto the early, pre-Brown politics of civil

rights in the United States. What makes the

Taft episode so intriguing, however, are the

rich counterfactual possibilities it presents.

ough the liberal coalition’s rejection of the

Taft bill prevented its formal introduction in

Congress, a contrary response would have

fundamentally altered the course of Ameri-

can fair employment law and the American

civil rights movement along with it. More

sweeping still, it is not at all implausible that

enactment of the Taft measure would have

transformed the post-war American party

system, making Republicans, not the sec-

tionally challenged Democrats, the party of

civil rights going forward. It is therefore sur-

prising that Taft’s offer has entirely escaped

popular or scholarly treatment until now.

Taft had long been a thorn in the side of

the broad coalition of groups lobbying for

federal fair employment legislation in the

immediate post-war period. e drive for

fair employment had begun in when

President Roosevelt, responding to a threat

by civil rights groups to unleash a “March

on Washington,” signed Executive Order

declaring a national policy against dis-

crimination and establishing the President’s

Committee on Fair Employment Practice.⁶

But soon after it opened its doors, the Com-

mittee’s limited reach became clear. Because

it was authorized only to hold hearings and

receive and “conciliate” discrimination com-

plaints, but lacked any further enforcement

authority where those efforts failed, many

employers simply ignored the Committee’s

directives.⁷ Soon civil rights groups called for

the vesting of the Committee with new pow-

ers modeled on the recently established Na-

tional Labor Relations Board, including the

authority to order that an employer “cease

and desist” from discriminatory practices and

take various types of action, including hiring,

Opportunity Commission (EEOC), not the entire regime. On Title VII’s potency after , see Paul

Frymer, Acting When Elected Officials Won’t: Federal Courts and Civil Rights Enforcements in U.S. Labor

Unions, 1935–95, A. P. S. R. (); Robert C. Lieberman, Weak State, Strong Policy: Para-

doxes of Race Policy in the United States, Great Britain, and France, S. A. P. D. ().

Finally, for the argument that judicial interpretation of Title VII went beyond the original statutory

bargain, see Daniel Rodriguez s Barry Weingast, e Positive Political eory of Legislative History: New

Perspectives on the 1964 Civil Rights Act and Its Interpretation, U. P. L. R. ().

A Bill (undated) (NAACP Papers, Library of Congress, Part II, Box A). See page below.

Studies of the Committee include A K, R, J, W: T FEPC

M, – (); M E. R, S M C R

M: T P’ C F E P, – ();

L R, R, J, P: T S FEPC ().

L C K, T S P FEPC: A S R P

M n. (); R, supra note , at ; F E P C-

, F R – ().

From The Ba g Wi nte r 2 006 183

The Taf t Pro posal of 1946

promotion, or backpay. Such hopes would

be dashed in early , however, when an

awkward alliance of Southern Democrats

and conservative Republicans, including Taft,

slashed the Committee’s budget, leaving just

enough to liquidate its affairs.⁸

As lobbying efforts for and against a per-

manent and more powerful Fair Employ-

ment Practices Commission (FEPC) moved

fair employment to the center of the Ameri-

can political stage, Taft’s strategy was to press

instead for a “voluntary” fair employment

scheme that, like Roosevelt’s Committee

before it, vested a new federal commission

with the power to receive and conciliate com-

plaints, but otherwise lacked coercive powers.

Anything more, Taft argued, would prove

counter-productive in the delicate area of

race relations. Taft’s strategy derived its pow-

er from the peculiar political economy of the

immediate post-war period. Referred to by

allies and enemies alike as “Mr. Republican,”

Taft was the arbiter of a key voting bloc of a

dozen northern Republican Senators on the

key political issues of the day. Indeed, Taft’s

staunch refusal to support anything more

than “voluntary” fair employment measures,

when combined with the outright opposition

of Southern Democrats to any bill that even

mentioned civil rights, had proven just barely

sufficient to defeat cloture votes during dra-

matic Senate filibusters in the previous Con-

gress. All the while, Taft and his Republican

allies seemed content to stand back as Dem-

ocrats struggled to overcome the deepening

sectional split within their ranks.⁹

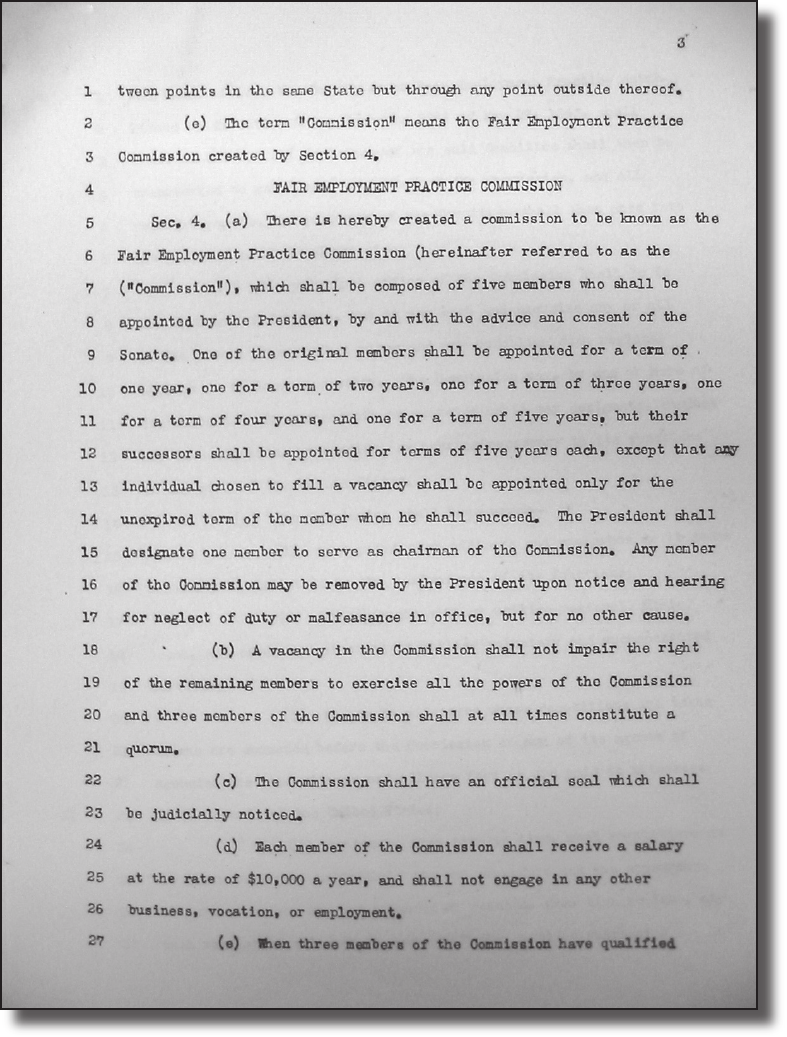

e draft measure Taft put forward in

, however, was different from his previ-

ous offerings – and strikingly different from

all other fair employment bills before or after.

e bill’s opening paragraphs carefully avoid-

ed creating any rights, instead establishing a

“policy” against discrimination. e bill then

provided for the creation of a five-member

Fair Employment Practices Commission

wielding a full complement of subpoena and

investigatory powers. In each of these re-

spects, it was not significantly different from

many of the “voluntary” bills from before.

e clean break from past bills came in

Section , titled “Preparation and Enforce-

ment of Compulsory Plan.” is Section

directed the new Commission to make a

“comprehensive study” of discrimination and

prepare a “comprehensive plan” for eliminat-

ing discrimination. “Such plan,” the bill con-

tinued, “may provide for additional employ-

ment throughout the area by increasing the

number of persons of the group discriminat-

ed against to be employed by specified em-

ployers who employ more than fifty persons”

and by requiring any union certified under

federal labor law “to admit to membership

persons of the group discriminated against.”

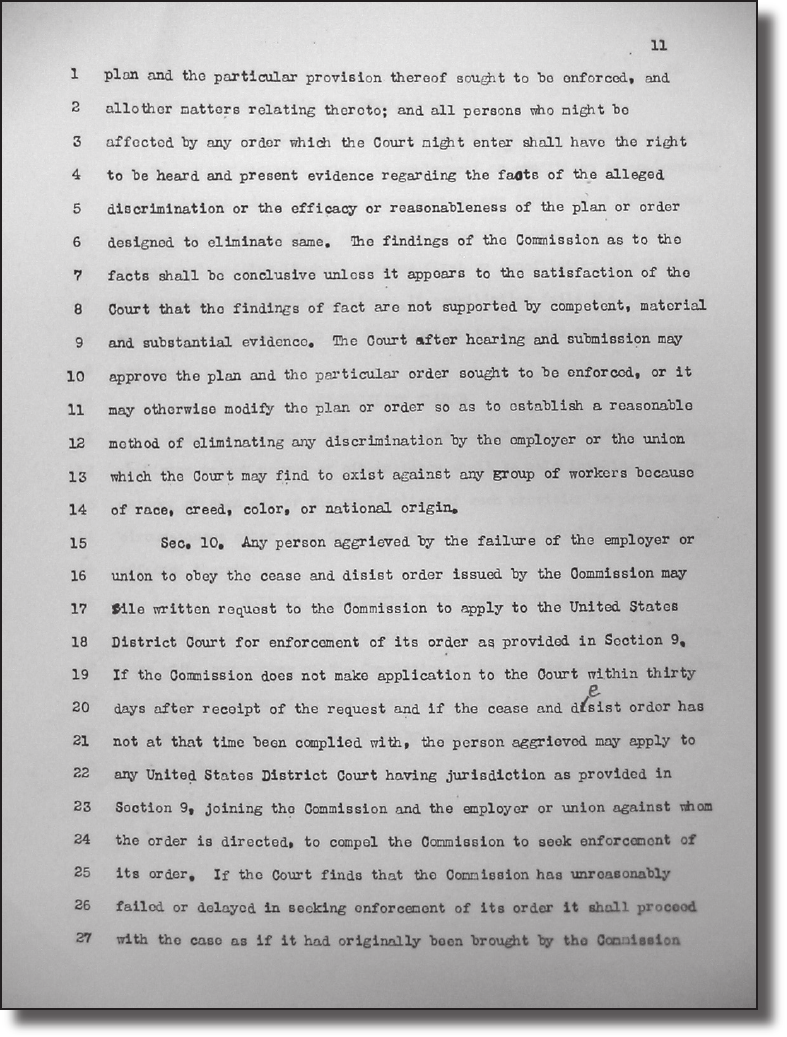

e concluding paragraph of Section

and Section provided the “teeth” that so

thoroughly differentiated the bill from past

bills. Once a compulsory plan had been in

operation for at least six months, “any sub-

stantial failure” to implement the plan would

trigger “compulsory enforcement.” is

would begin with a Commission order re-

quiring that an employer “provide forthwith

employment of specified character for the

number of persons belonging to the group

discriminated against” or that a union ad-

mit “members of such group.” Any failure to

comply with such an order, the bill contin-

ued, would result in the Commission’s filing

of a petition in federal court. Further, any

person aggrieved by a failure of an employer

or union to comply with a compulsory plan

R J. W, W W J: A H A A ().

See Sean Farhang s Ira Katznelson, e Southern Interposition: Congress and Labor in the New Deal and

Fair Deal, S. A. P. D. (); R, supra note , at .

184 9 G r e e n Ba g 2 d 181

Davi d Fre eman En gs trom

could, after filing a written request with the

Commission and waiting for days, file suit

in federal court to compel compliance.

Compared to previous Taft offerings, this

new bill was shockingly broad. Unlike previ-

ous proposals, this one was fully enforceable,

albeit after the various delays built into the

scheme. Taft’s scheme also provided indi-

vidual claimants with more-or-less direct re-

course to federal courts. Indeed, once a plan

was in place, an individual needed only ad-

vise the Commission, wait days, and then

seek injunctive relief in court. Finally, its core

provisions, centered as they were upon the

creation of regional “comprehensive plans,”

seemed to contemplate widespread use of

systemic, quota-based hiring.

One reason that the Taft proposal has not

previously come to light¹⁰ is that Taft only

privately communicated his offer to the Na-

tional Council for a Permanent FEPC (“Na-

tional Council”), the leading national orga-

nization lobbying in the fair employment

area, and the National Council quietly and

unceremoniously rejected it. Neither side, it

seems, was willing to make public its con-

sideration of the measure. But the National

Council’s decision to reject Taft’s offer also

occasioned heated internal deliberation, and

it is here that the archival record offers a rare

glimpse of the complex coalitional politics of

civil rights at mid-century.

Founded by black labor leader A. Philip

Randolph in , the National Council

exemplified the broad set of interests that

came to march beneath the fair employment

standard in the immediate post-war period.¹¹

Among its member groups were more than

a hundred different organizations, includ-

ing unions like Randolph’s all-black Broth-

erhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the United

Auto Workers of the Congress of Industrial

Organizations (CIO), and the International

Ladies’ Garment Workers Union of the

American Federation of Labor (AFL); race

advancement organizations such as the Na-

tional Association for the Advancement of

Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban

League; religious groups such as the Ameri-

can Jewish Congress and the Catholic Inter-

racial Council; and liberal civic groups like

the Americans for Democratic Action. e

real decision-making power, however, lay

with the Council’s Policy Committee, where

only the more influential member organiza-

tions held seats. And it was here that the Taft

proposal had to gain traction if it was ever to

see the light of day.

As the Policy Committee members

worked their way through the provisions of

Taft’s offer, Randolph was the first to weigh

in, by way of a starkly worded telegram.¹²

“Since no FEPC bill can get thru without

bipartisan support,” he pleaded, “I strongly

urge acceptance of amended Taft bill since

it has enforcement and investigatory powers.”

Moreover, Randolph conceded that it was

not “just what Council and cooperating or-

ganizations may want” but was nonetheless

e sole mention of the Taft plan in any writing is the following sentence in K, supra note ,

at : “When Randolph suggested that the National Council accept a watered-down FEPC bill spon-

sored by Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio to salvage something out of the legislative drive, White

and Carey vigorously rejected the proposal, giving temporary credence to the National Council’s claim

that the responsibility for leadership had been broadened.” No discussion follows.

K, supra note , at –. On the rise of “racial liberalism” through groups like the National

Council, see M B, C L: C R S A’ “R

F,” – (), esp. Chapter One.

Telegram from A. Philip Randolph to Walter White (May , ) (NAACP Papers, Library of Con-

gress, Part II, Box A).

From The Ba g Wi nte r 2 006 185

The Taf t Pro posal of 1946

“a step in right direction.” “Have spent some

time in Washington lobbying for FEPC and I

am familiar with political problems involved,”

Randolph concluded. “It is my considered

judgment that it would be tragic blunder

not to push Taft bill now with all our forces

since there appears to be some possibility of

getting passed. Kindly advise Council your

reaction immediately.”

Over the next two days, a series of tele-

grams, letters, and phone messages made

their way into National Council headquar-

ters.¹³ Two of these were guarded but favor-

able. e position of Charles Houston, per-

haps the leading civil rights lawyer of his day,

was that “we should accept compromise if

it is best we can get since bill would at least

establish policy.” “Must however be assured,”

he continued, “of enactment this Congress.”

Another leading civil rights lawyer, urman

Dodson, arrived at a similar conclusion: de-

spite the bill’s “terribly emasculated” state, he

would “reluctantly consent to the proposal if

we had a guarantee of its passage.”

e remaining responses, however, were

uniformly negative. Walter White, head of

the NAACP, announced that the bill was “so

weak it is tantamount to throwing in sponge.”

He continued, “Bill unsatisfactory in that

it does not contemplate redress individual

grievances but predicated upon discrimina-

tion against groups.” When the “year or eigh-

teen months” required to negotiate a compul-

sory plan was combined with the six-month

waiting period prior to court action, the re-

sulting delay would “virtually insure issue be-

ing dead one by that time.” White also noted

that Congress was due to adjourn in July,

leaving little time to enact even this “greatly

weakened compromise measure.” “Regret we

cannot go along with you,” he concluded.

Equally dismissive was the response of

organized labor. e AFL’s Boris Shishkin

echoed many of the NAACP’s concerns, ob-

jecting above all to the group ontology of the

remedial scheme. “e individual is reached

secondarily and may or may not be reached,”

Shiskin asserted, since the individual “does

not have the right to go to court until the

plan is in effect.” Shishkin also decried the

“time lag” built into the scheme, and then fin-

ished with a flourish: “If you deal with a right,

you deal with the right of a man. [With the

Taft bill, y]ou are improving a condition per-

haps, but you are not making employment

opportunity the basic right of an individual.”

A telegram from James B. Carey, Secretary-

Treasurer of the CIO, was less detailed but

just as emphatic in its conclusion: “Cannot

endorse contents of amended Taft Bill. Be-

lieve we should push principles original pro-

gram.”

e remaining voices in the archival

record were equally opposed. “is bill,”

George Hunton of the Catholic Interracial

Council charged, “is a detailed procedural

survey only,” and its acceptance would make

Council members “traitors to the people sup-

porting us.” A.S. Makover, a Baltimore lawyer

consulted by the NAACP, noted the asym-

metrical treatment of employers and unions,

since increasing “the number of persons” dis-

criminated against would not ensure that an

aggrieved was actually given a job, but indi-

viduals denied union membership would be

specifically admitted. Moreover, Makover

See Telegram from Leslie Perry to Walter White (May , ) (NAACP Papers, Library of Congress,

Part II, Box A); Memorandum, Reactions to Proposed Taft Bill (May , ) (NAACP Papers,

Library of Congress, Part II, Box A); Telegram from Walter White to A. Philip Randolph (May ,

) (NAACP Papers, Library of Congress, Part II, Box A); Telegram from James B. Carey, Sec-

retary-Treasurer of the CIO to Walter White (May , ) (NAACP Papers, Library of Congress,

Part II, Box A); Letter from A.S. Makover to Anna Arnold Hedgeman (May , ) (NAACP

Papers, Library of Congress, Part II, Box A).

186 9 G r e e n Ba g 2 d 181

Davi d Fre eman En gs trom

expressed concern about the plan’s judicial

review provisions, citing “past experience in

other legislation” and warning of “the emas-

culation of any good in any plan proposed

by the Commission by some of the District

Court judges.”

What impelled Taft to change course in

and propose a fully enforceable fair employ-

ment scheme? e reasons surely include

many of the same forces that drove fair em-

ployment to the top of the post-war politi-

cal agenda in the first place: widening public

concern about the deterioration of American

race relations in response to a spate of war-

time race riots; the moral authority conferred

by African-American contributions to the

war effort; the obvious disjunction between

the political values projected abroad and

those practiced at home as the Cold War

chill set in; and a rapidly shifting electoral

landscape with the migration of some three

million southern African-Americans to piv-

otal northern industrial states. On the latter,

Taft may have been looking to shore up his

popularity among black voters as he eyed

a presidential run in . Firmer answers

than these, however, are hard to come by, for

Taft’s own papers at the Library of Congress

make no mention of his offer.

e mix of factors that explains the

mostly negative reaction of various mem-

bers of the fair employment coalition to the

Taft offer is no less certain. As White at the

NAACP argued, there were strong pragmat-

ic reasons that militated against throwing co-

alition support behind a new scheme so late

in the congressional session. e Taft episode

also came at a liminal moment in American

political development. e Lochner-ism of

recent decades meant that most regulatory

architects saw courts as a brake on, not a

spur to, social and political change.¹⁴ When

combined with a cresting New Deal faith

in administrative governance, this may have

been enough to drive civil rights groups away

from the hybrid agency-court Taft propos-

al and towards the more agency-centered

FEPC approach.

ere is strong evidence that political-

organizational considerations played a role

as well. e NAACP had long taken heat

for its middle-class tenor and elite-litigation

focus.¹⁵ Its preference for an individualized,

agency-centered model without the Taft

scheme’s delays may have reflected an orga-

nizational imperative to support a scheme

that could deliver rapid and concrete relief

to particular complainants rather than more

elite-level litigation. Similarly, much has

been written documenting the famously am-

biguous relationship of organized labor to

the fair employment movement as stemming

from pervasive rank-and-file racism and the

differing economic incentives that faced the

low- and semi-skill industrial unions of the

CIO and the higher-skill and more exclusive

craft unions of the AFL.¹⁶ But it is also clear

that much of labor’s support for fair employ-

ment was instrumental, conceived as much

e Supreme Court’s decision in Lochner v. New York, U.S. (), has come to symbolize the

anti-regulatory stance of the pre-New Deal judiciary. See Gary D. Rowe, Lochner Revisionism Revisited,

L s S. I ().

See, e.g., Risa Lauren Goluboff, ‘Let Economic Equality Take Care of Itself ’: e NAACP, Labor Liti-

gation, and the Making of Civil Rights in the s, UCLA L. R. , – (); Beth

Tompkins Bates, A New Crowd Challenges the Agenda of the Old Guard in the NAACP, –,

A. H. R. ().

See, e.g., D E. B, O O P R: A-A, L R-

, C R N D –, – ().

From The Ba g Wi nte r 2 006 187

The Taf t Pro posal of 1946

as an opportunity to win over black voters

and fend off attacks on the New Deal state

by Southern Democrats and conservative,

Taftite Republicans as it was a principled

stance on equality.¹⁷ Enactment of the Taft

plan would have both exposed union locals

to regulation and likely spelled the end of

what was serving as a fruitful rallying point

for labor’s political organizing efforts.

Whatever its precise cause, the National

Council’s rejection of the Taft offer would

critically shape the future course of the

fair employment movement and perhaps

post-war American law and politics more

broadly. Fall-out from the Taft episode led

to changes in leadership at the National

Council and, after a careful effort to obtain

buy-in from member groups, the final crys-

tallization of the agency-centered FEPC

model as the consensus choice of the fair

employment coalition.¹⁸ e Taft episode

also marked a pronounced centralization of

the fair employment movement as a whole,

including much more aggressive National

Council oversight of state-level legislative

campaigns.¹⁹ What emerged from this dual

process of crystallization and centraliza-

tion in the years after was an ironclad

consensus in favor of the administratively

enforced and highly individualized FEPC

approach over other, more court-centered or

systematic alternatives. Ultimately, of

states that enacted fully enforceable fair em-

ployment laws prior to created purpose-

built bureaus to enforce them. No state en-

acting fair employment legislation opted for

anything resembling the Taft plan.²⁰

If the short-run consequences of the

National Council’s rejection of the Taft pro-

posal were significant, then the long-term

consequences of that rejection are incalcu-

lable. It is clear, for instance, that the Taft

plan would have yielded far more vigorous

efforts to regulate job discrimination than

anything seen until the s, when expan-

sive judicial interpretations of Title VII and

the advent of affirmative action programs in

public contracting transformed American

fair employment law into a potent regula-

tory scheme. Fair employment groups would

not be successful in their efforts to enact a

federal-level fair employment law until

– a full years later – and even then would

fail to win creation of a centralized admin-

istrative body armed with cease-and-desist

authority. Similarly, in the years following

the Taft episode, the delays that accompa-

nied the adjudication of complaints by the

fair employment practices commissions cre-

ated by many states – and that, in , were

already operating in New York, New Jersey,

and Massachusetts – often rivaled the year-

and-a-half to two years that the NAACP

worried would elapse prior to court enforce-

ment of a compulsory plan under the Taft

K B, T UAW H A L, – (); H-

S, A N D B: T E C R N

I – ().

See Meeting Minutes of Policy Committee (November , ) (McLaurin Papers, Schomburg Center

– New York Public Library, Box ); Memorandum from Roy Wilkins to Walter White (November ,

) (NAACP Papers, Library of Congress, Part II, Box A); Meeting Minutes of Legal Commit-

tee (November , ) (McLaurin Papers, Schomburg Center – New York Public Library, Box ).

See, e.g., K, supra note , at , ; Letter from Albert J. Weiss to “Friend” (December , )

(NAACP Papers, Library of Congress, Part II, Box A).

David Freeman Engstrom, e Lost Origins of American Fair Employment Law: State Fair Employment

Practices Bureaus and the Politics of Regulatory Design, 1943–1964 – (unpublished Ph.D. disserta-

tion, Yale Univ., ).

188 9 G r e e n Ba g 2 d 181

Davi d Fre eman En gs trom

scheme.²¹ Finally, the concern that the Taft

measure was insufficiently focused on indi-

vidual-level remedies stands in stark contrast

to a pervasive criticism of the state commis-

sions in subsequent years: that the individual-

complaint method at the core of the FEPC

model hampered efforts to move more than

trivial numbers of minorities into labor mar-

kets and unions.²² All of this compels the

conclusion that implementation of the Taft

plan would have improved the labor market

position of African-Americans.

e most arresting counterfactual pos-

sibilities, however, go far beyond increased

enforcement vigor and labor-market gains

for African-Americans. For instance, the

Taft scheme would have been the most

significant policy intervention on behalf of

African-Americans since Reconstruction.

Its symbolism alone would have provided a

powerful boost to early civil rights mobiliza-

tions a full eight years before Brown v. Board

of Education,²³ and the Mississippi murder

of Emmett Till a year later, catalyzed the

movement.

e Taft plan’s explicit authorization of

quota-based relief could also have altered the

trajectory of federal equal protection juris-

prudence by forcing a much earlier reckon-

ing with the constitutionality of preferential

treatment under the Fourteenth Amendment.

at issue would not be squarely before the

Supreme Court until more than years later,

in the Bakke case.²⁴ A decision uphold-

ing the Taft scheme might have made Bakke,

as well as City of Richmond, Adarand, and

the recent Bollinger cases, relatively straight-

forward as a precedential matter, reducing

the political salience of affirmative action.²⁵

A contrary decision invalidating the systemic

components of the Taft plan might have fore-

closed development of the affirmative action

programs at issue in these later cases in the

first place. Either ruling could have excised a

highly divisive issue from American politics

in later decades.

is latter point hints at perhaps the most

sweeping counterfactual possibility of all, for

it is not a stretch to suggest that enactment

of the Taft plan in would have funda-

mentally altered the post-war American

party system. Indeed, Taft’s apparent will-

ingness to support a wide-open, highly sys-

temic remedial scheme, and the rejection of

that scheme by coalition members because

it was insufficiently individualized, reverses

the partisan valence of much recent debate

over affirmative action. If Taft’s offer was a

legitimate one – and biographies of Taft

himself, as well as his status as “Mr. Repub-

lican” in the Senate chamber, suggest no rea-

son to believe he could not deliver the nec-

essary votes – then Republicans stood ready

to put into place a fully enforceable scheme

Herbert Hill, Twenty Years of State Fair Employment Commissions: A Critical Analysis with Recommenda-

tions, B. L. R. , , (–); Elmer A. Carter, Practical Considerations of Anti-Discrimi-

nation Legislation – Experience Under the New York Law Against Discrimination, C L.Q. ,

().

See, e.g., Symposium, Toward Equal Opportunity in Employment: e Role of State and Local Government,

B. L. R. (); D L, T E O (), esp. Chapter ;

P H. N s S E. H, T F E (), esp. Chapter ; Note,

e Right to Equal Treatment: Administrative Enforcement of Antidiscrimination Legislation, H. L.

R. (); Albert L. Alford, FEPC: An Administrative Study of Selected State and Local Programs

(unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton Univ., ).

U.S. ().

Regents of the Univ. Cal. v. Bakke, U.S. ().

Gratz v. Bollinger, U.S. (); Grutter v. Bollinger, U.S. (); Adarand Construc-

tors, Inc. v. Pena, U.S. (); City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., U.S. ().

From The Ba g Wi nte r 2 006 189

The Taf t Pro posal of 1946

that would have advanced the clock by more

than twenty years in providing for a systemic,

group-based approach to remedying job

discrimination.²⁶ At the dawn of American

fair employment law, it was the fair employ-

ment coalition, not Republicans, that shied

away from systemic remedies and insisted

on the creation of individualized rights to be

administratively enforced via case-by-case

adjudication of complaints.

Here, the Taft episode also implicates

a well-known storyline among students of

post-war American politics: that the unrav-

eling of the New Deal coalition flowed, at

least in part, from the quickening of the civil

rights movement after and the develop-

ment by Republicans of a so-called “South-

ern strategy” that capitalized on a growing

white backlash against anti-discrimination

policies in employment, housing, and edu-

cation.²⁷ How might enactment of the Taft

plan have changed matters? One view is that

the systemic remedies called for by the Taft

plan – combined with an emboldened civil

rights movement – would have spawned an

earlier backlash. But this is by no means a

given. A more aggressive approach to job dis-

crimination might have just as easily defused

the situation. Observers in believed as

much, arguing that aggressive early imple-

mentation efforts by state FEPCs would

have ensured that any backlash was “stimu-

lated and met between and ,” set-

ting “a different pattern … for the administra-

tion of anti-bias legislation generally.”²⁸ On

this view, the opening of labor markets to

black workers was a race against time before

the civil rights movement turned to the more

emotional questions raised by the desegrega-

tion of housing and schools.

Perhaps most important of all, enactment

of the Taft measure might have dampened

the later politics of backlash, either by pre-

venting civil rights policy from traveling

down the bitterly partisan road that it did, or

perhaps even making Republicans, not Dem-

ocrats, the party of civil rights going forward.

Neither possibility is as implausible as it

sounds. Race had been swept under the car-

pet during the period of Republican ascen-

dance that stretched roughly from McKinley

to Hoover, and even during the New Deal

itself.²⁹ is decades-long silence on race is-

sues meant that the partisan mantle on civil

rights was largely up for grabs.

Further, while we are conditioned to

think of African-Americans as thoroughly

aligned with the Democratic party – in the

and presidential elections, more

than percent of blacks voted Democratic

– the movement of black voters away from

the “party of Lincoln” and towards the Dem-

ocratic party was far from complete in .

is was surely the case in the liberal North-

east, where moderate Republicans like New

York Governor omas Dewey remained

out front on civil rights issues, and in key

cities like Philadelphia where Republican

machines continued to hold power.³⁰ In the

presidential election that pitted Tru-

See J T. P, M R: A B R A. T (). On advancing

the clock, the Taft plan resembles in some of its particulars proposals as recent as . See, e.g., David

Strauss, e Law and Economics of Racial Discrimination in Employment: e Case for Numerical Stan-

dards, G. L.J. , – ().

See generally T B. E s M D. E, C R: T I R,

R, T A P ().

Joseph B. Robinson, Comment, B. L. R. , (–).

P F, U A: R P C A (); N

W, F P L: B P A FDR xiv ().

Oscar Glantz, Recent Negro Ballots in Philadelphia, in Miriam Ershkowitz s Joseph Zikmund II, eds.,

190 9 G r e e n Bag 2d 181

Davi d Fre eman En gs trom

man against Dewey, held just four months

after President Truman integrated the mili-

tary and civil service, and just one year after

his high-profile Commission on Civil Rights

set forth an aggressive civil rights agenda

in To Secure ese Rights, Truman could

not muster more than percent of black

votes nationwide. ( Just eight years later, in

, Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson

could garner only percent in his second

loss to Eisenhower.³¹) Enactment of the Taft

plan two years before the election might

have undercut Truman’s civil rights efforts,

stanching the flow of black voters away from

the Republican party, putting Dewey in the

White House in the short-term, and making

racial appeals of the later, “Southern strategy”

sort politically risky over the long-term.

Finally, because it retained strong judicial

control over implementation, the Taft plan

might have halted the growing partisan bent

of American civil rights politics by unhitch-

ing Republican opposition to the New Deal

administrative state from the fair employ-

ment issue. Here is a weakness of the few

existing histories of early American fair em-

ployment law, which have too often strained

to see in early legislative debates the devel-

opment of a rhetorical template of racial

reaction centered around quotas, preferen-

tial treatment, and reverse discrimination.³²

Missing in this rush to uncover the histori-

cal antecedents to contemporary affirmative

action debates, however, is an equally criti-

cal point: the choice of the FEPC model at

the dawn of the fair employment movement

delivered that movement – and the early

civil rights movement more broadly – into

the teeth of a larger, and mostly partisan,

struggle over the legitimacy of the New Deal

administrative state and its place within the

post-war American legal and political order.

If the Taft episode is any indication, Republi-

can objections to fair employment regulation

at the dawn of the movement were rooted

at least as much in concerns about creeping

administrative power as in race matters or

racial preferences. Separating out regulatory

concerns from civil rights issues might have

further denied the partisan soil in which the

later politics of backlash would take root and

flourish.

B P P (); J R, T A G: R

O P P ().

For general discussion, see Michael J. Klarman, Brown, Racial Change, and the Civil Rights Movement,

V. L. R. , – ().

Anthony Chen, “is Law Would … Result in the Hitlerian Rule of Quotas”: e Rhetoric of Racial Back-

lash and the Politics of Fair Employment Practice Legislation in New York State, 1941–1945 (forthcoming,

J. A. H., ); P D. M, F D A A A: F E-

L P A, – (); J D S, T I

A A: P, C, J A ().

From The Ba g Wi nte r 2 006 191

The Taf t Pro posal of 1946

192 9 G r e e n Bag 2 d 181

Davi d Fre eman En gs trom

From The Ba g Wi nte r 2 006 193

The Taf t Pro posal of 1946

194 9 G r e e n Bag 2 d 181

Davi d Fre eman En gs trom

From The Ba g Wi nte r 2 006 195

The Taf t Pro posal of 1946

19 6 9 G r e e n Ba g 2 d 181

Davi d Fre eman En gs trom

From The Ba g Wi nte r 2 006 197

The Taf t Pro posal of 1946

198 9 G r e e n Ba g 2 d 181

Davi d Fre eman En gs trom

From The Ba g Wi nte r 2 006 199

The Taf t Pro posal of 1946

200 9 G r e e n Ba g 2 d 181

Davi d Fre eman En gs trom

From The Ba g Wi nte r 2 006 201

The Taf t Pro posal of 1946

202 9 G r e e n Ba g 2 d 181

Davi d Fre eman En gs trom