Guidance for Developing

and Maintaining a

Service Line Inventory

Office of Water (4606M)

EPA 816-B-22-001

August 2022

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining i August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Disclaimer

This document provides recommendations to public water systems in developing and

maintaining a service line inventory. The guidance within this document can be used to comply

with the requirements under the Lead and Copper Rule Revisions (LCRR) that are in effect at the

time of document publication. As described in the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s)

Federal Register notice of December 17, 2021 (“Notification of conclusion of review”), EPA

intends to publish a proposal to revise the LCRR and take final action on the proposal by October

16, 2024, but EPA does not expect to propose changes to the requirements for information to be

submitted in the initial service line inventory. However, the rulemaking could include changes to

the requirements for inventory updates (USEPA, 2021a). This guidance can also assist public

water systems with financing applications for Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) (P.L. 117-58)

funds and for implementation once funding is received. Note that the BIL is also known as the

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). The BIL contains a historic $15 billion in dedicated

funding through the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) for lead service line (LSL)

identification, planning, design, and replacement. LSL projects also may be funded using the

General Supplemental DWSRF fund of $11.7 billion as well as annual base appropriations for the

DWSRF. The BIL mandates that 49 percent of funds provided through the DWSRF General

Supplemental Funding and DWSRF Lead Service Line Replacement Funding must be provided as

grants and forgivable loans to disadvantaged communities. EPA encourages water systems to

begin service line inventory and replacement efforts as soon as possible. EPA emphasizes that

given the many benefits of lead service line replacement (LSLR), water systems should not wait

until their inventory is complete to begin replacement efforts. In fact, conducting replacements

while developing the inventory can have synergistic effects that enhance inventory development

while accelerating and increasing the efficiency of replacement programs. The statutory

provisions and EPA regulations described in this document contain legally binding requirements.

This document is not a regulation itself, nor does it change or substitute for those provisions and

regulations. Thus, it does not impose legally binding requirements on EPA, states, or the

regulated community. This document does not confer legal rights or impose legal obligations

upon any member of the public.

Although EPA has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the discussion in this document,

the legally binding requirements applicable to public water systems are determined by statutes

and regulations. In the event of a conflict between the discussion in this document and any

applicable statute or regulation, this document would not be controlling.

The information collections associated with the LCRR have been submitted for approval to the

Office of Management and Budget (OMB) under the Paperwork Reduction Act. The

recordkeeping and reporting requirements described in this draft guidance align with the

existing regulations and this guidance also includes recommendations for voluntary expanded

data collection and recordkeeping. An agency may not conduct or sponsor, and a person is not

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining ii August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

required to respond to a collection of information unless it displays a currently valid OMB

control number. The OMB control number for the service line inventory is 2040-0297.

The recommendations provided here may not apply to a particular situation based upon the

circumstances. Because they are recommendations, and not legally binding requirements, public

water systems retain the discretion to follow the recommendations or adopt approaches that

differ from those described in this document. In some cases, recommendations may reflect the

existing custom and practices of some states.

Note that this document does not address lending requirements or state or local regulations

related to service line inventories that may apply.

Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or

recommendation for their use.

This is a living document that EPA may revise periodically to reflect changes in regulatory

requirements and research regarding service line material identification. EPA welcomes

comment on this document at any time; please send comments to [email protected].

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining iii August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1-1

1.1 The Benefits of a Comprehensive and Accurate Inventory ................................................ 1-1

1.2 Purpose and Audience ....................................................................................................... 1-2

1.3 Overview of Regulatory Requirements and LCRR Review .................................................. 1-3

1.3.1 Overview of the LCRR Inventory Requirements .......................................................... 1-3

1.3.2 Outcome of EPA Review of the LCRR .......................................................................... 1-6

1.3.3 Related Requirements under the LCR ......................................................................... 1-7

1.4 Document Organization ..................................................................................................... 1-8

Chapter 2: Elements of the Inventory ........................................................................................... 2-1

2.1 Inventory Materials Classifications .................................................................................... 2-1

2.1.1 Required Service Line Inventory Material Classifications ........................................... 2-1

2.1.2 Recommended Subclassifications and Additional Information (Not Required Under

LCRR) .......................................................................................................................... 2-6

2.1.3 Recommendations for Other Drinking Water Infrastructure ...................................... 2-7

2.2 Include All Service Lines Regardless of Ownership Status and Intended Use ..................... 2-8

2.2.1 Required under the LCRR............................................................................................ 2-8

2.2.2 Recommendations (Not Required under the LCRR) .................................................... 2-9

2.3 Location Identifiers .......................................................................................................... 2-10

2.3.1 Required under the LCRR.......................................................................................... 2-10

2.3.2 Recommendations (Not Required under the LCRR) .................................................. 2-10

2.4 Other Recommended Service Line Characteristics ........................................................... 2-11

Chapter 3: Inventory Planning ..................................................................................................... 3-1

3.1 Inventory Development Approach ..................................................................................... 3-1

3.2 Identifying Staff and Resources .......................................................................................... 3-2

3.3 Selecting an Inventory Format ........................................................................................... 3-3

3.3.1 List, Spreadsheet, or Database ................................................................................... 3-4

3.3.2 Maps ........................................................................................................................... 3-6

3.4 Develop Procedures for Collecting Service Line Information ............................................. 3-6

3.5 Establish Partnerships with Third Parties ........................................................................... 3-8

Chapter 4: Historical Records Review ........................................................................................... 4-1

4.1 Previous Materials Evaluation ............................................................................................ 4-3

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining iv August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

4.2 Construction and Plumbing Codes and Records ................................................................. 4-4

4.3 Water System Records ....................................................................................................... 4-7

4.4 Inspections and Records of the Distribution System ........................................................ 4-10

Chapter 5: Service Line Investigation Methods ............................................................................. 5-1

5.1 Visual Inspection of Service Line Material .......................................................................... 5-1

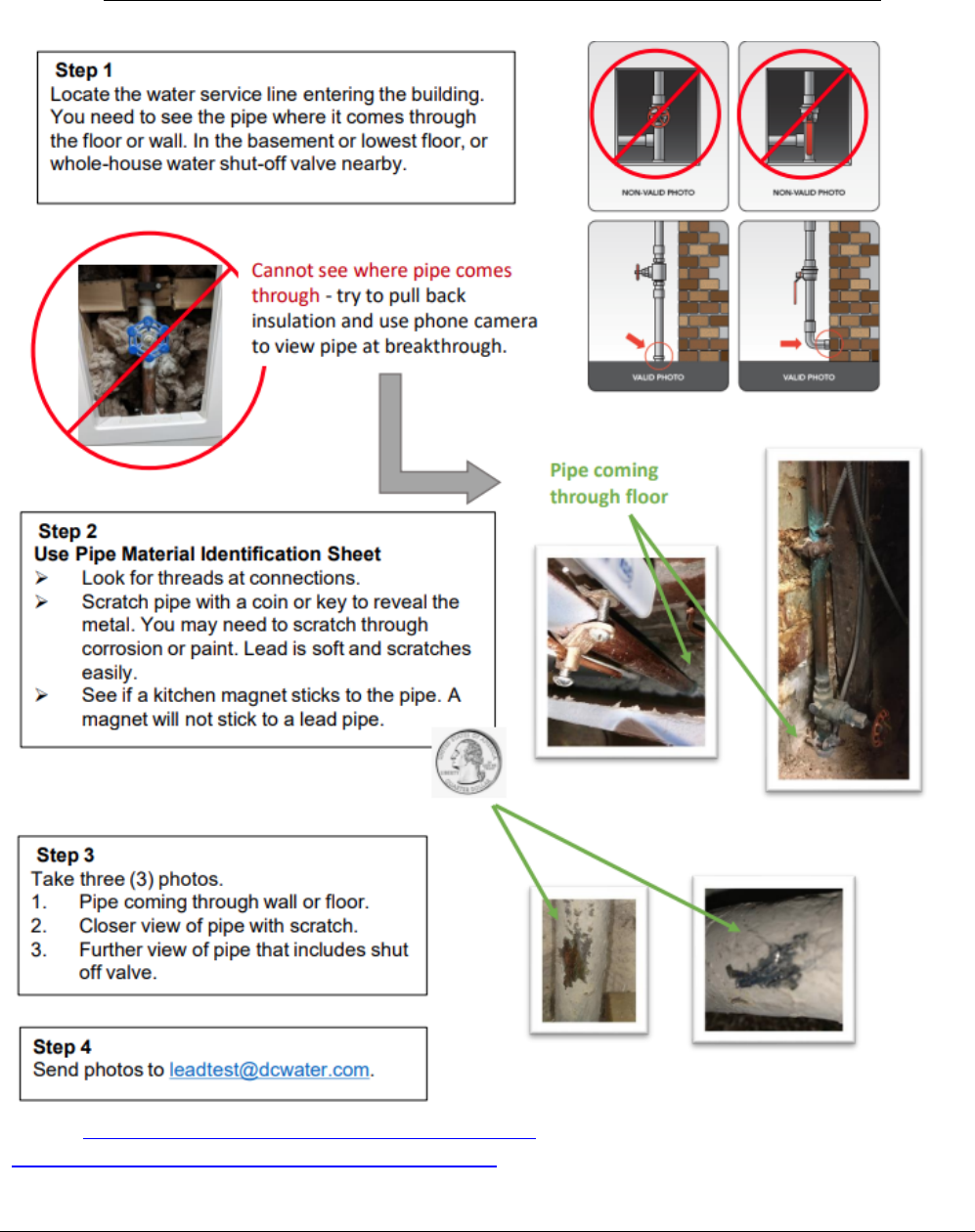

5.1.1 Visual Inspection of Service Line by Customers .......................................................... 5-3

5.1.2 CCTV Inspection by the Water System ....................................................................... 5-7

5.2 Water Quality Sampling ................................................................................................... 5-10

5.3 Excavation ........................................................................................................................ 5-12

5.3.1 Mechanical Excavation ............................................................................................. 5-13

5.3.2 Vacuum Excavation .................................................................................................. 5-14

5.4 Pros and Cons of Field Investigation Methods (Hensley et al., 2021) ............................... 5-14

5.5 Predictive Modeling ......................................................................................................... 5-17

5.6 Emerging Methods ........................................................................................................... 5-17

Chapter 6: Developing and Updating the Inventory ..................................................................... 6-1

6.1 Developing the Initial Inventory ......................................................................................... 6-1

6.1.1 Required under the LCRR............................................................................................ 6-1

6.1.2 Recommendations (Not Required under the LCRR) .................................................... 6-2

6.2 Prioritizing Field Investigations .......................................................................................... 6-6

6.3 Requirements and Recommendations for Systems with Only Non-Lead Service Lines ...... 6-8

6.3.1 LCRR Requirements .................................................................................................... 6-8

6.3.2 Recommendations (Not Required under the LCRR) .................................................... 6-8

6.4 Submitting the Initial Service Line Inventory .................................................................... 6-10

6.5 Notification of Known or Potential Service Line Containing Lead .................................... 6-11

6.6 Inventory Updates ........................................................................................................... 6-12

6.7 State Review and Reporting ............................................................................................. 6-13

6.7.1 State Review of the Initial Inventory ........................................................................ 6-13

6.7.2 State Reporting Requirements ................................................................................. 6-14

Chapter 7: Public Accessibility ...................................................................................................... 7-1

7.1 What Information to Include .............................................................................................. 7-1

7.1.1 Required under the LCRR............................................................................................ 7-1

7.1.2 Recommendations (Not Required under the LCRR) .................................................... 7-2

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining v August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

7.2 How to Make the Data Publicly Available .......................................................................... 7-5

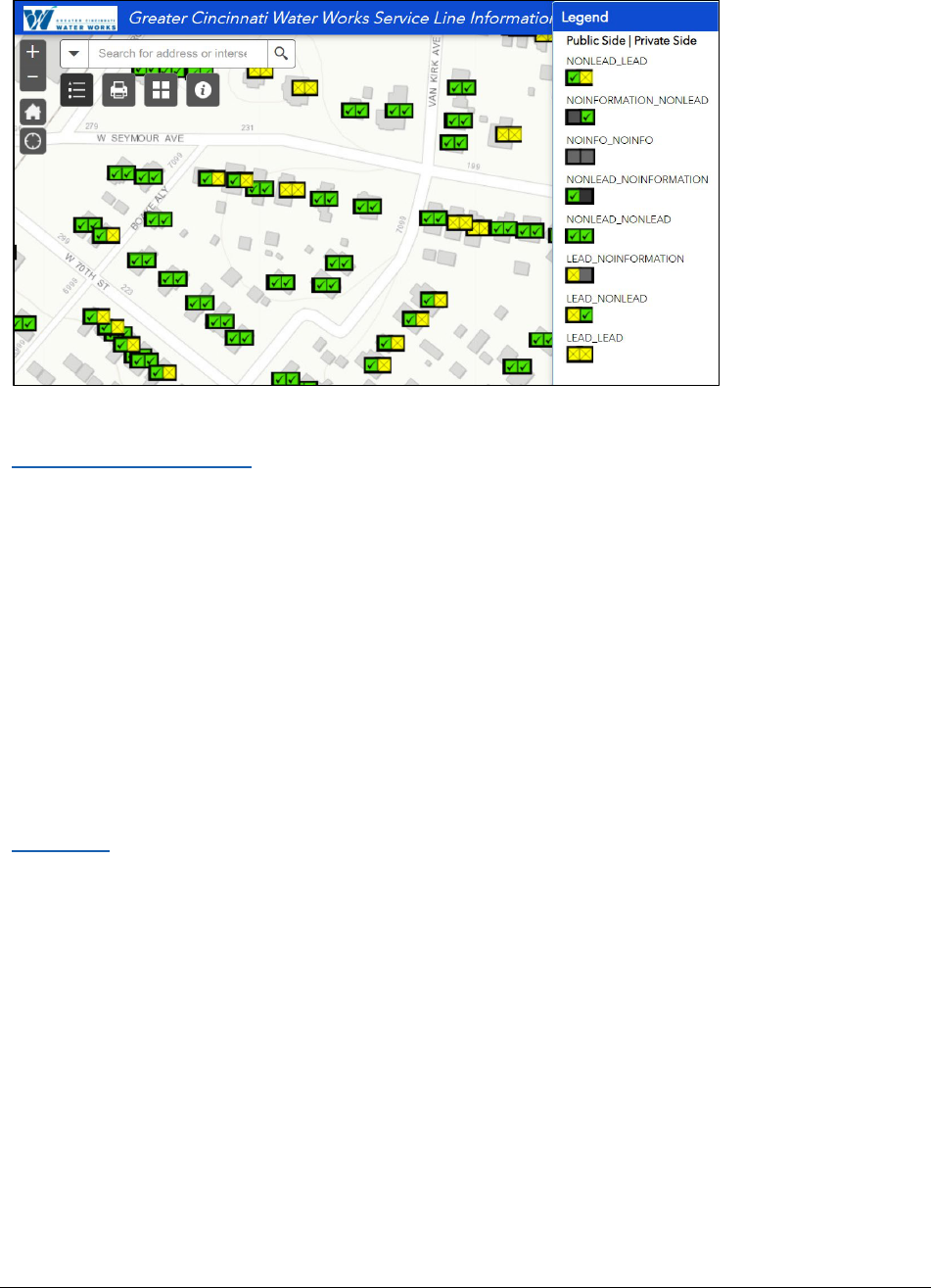

7.2.1 Description of Available Web-Based Map Applications .............................................. 7-5

7.2.2 Web-Based Map Application Best Practices ............................................................... 7-6

7.2.3 Public Data Sharing Alternatives ................................................................................. 7-8

7.2.4 Public Input and Updates ........................................................................................... 7-9

7.3 Considerations for States ................................................................................................. 7-10

7.4 Consumer Confidence Report Inventory Requirements ................................................... 7-11

Chapter 8: References .................................................................................................................. 8-1

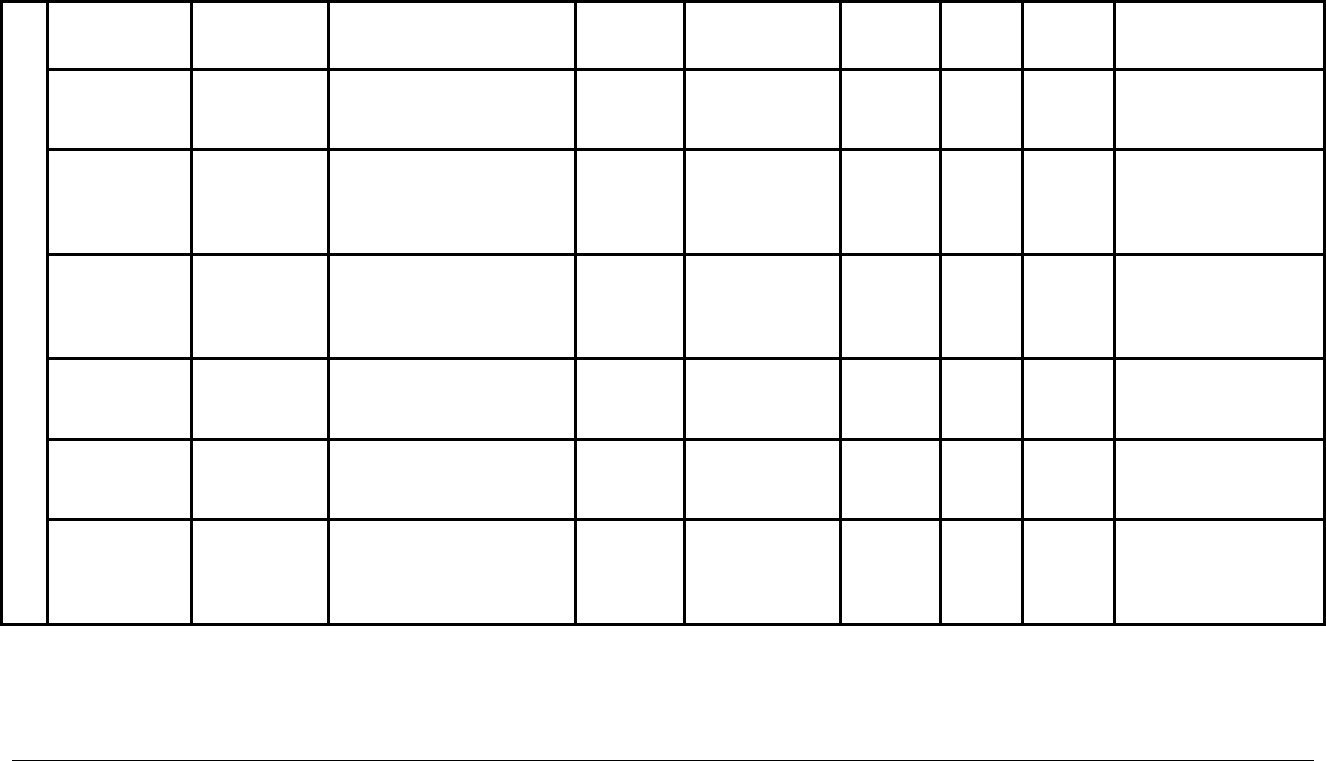

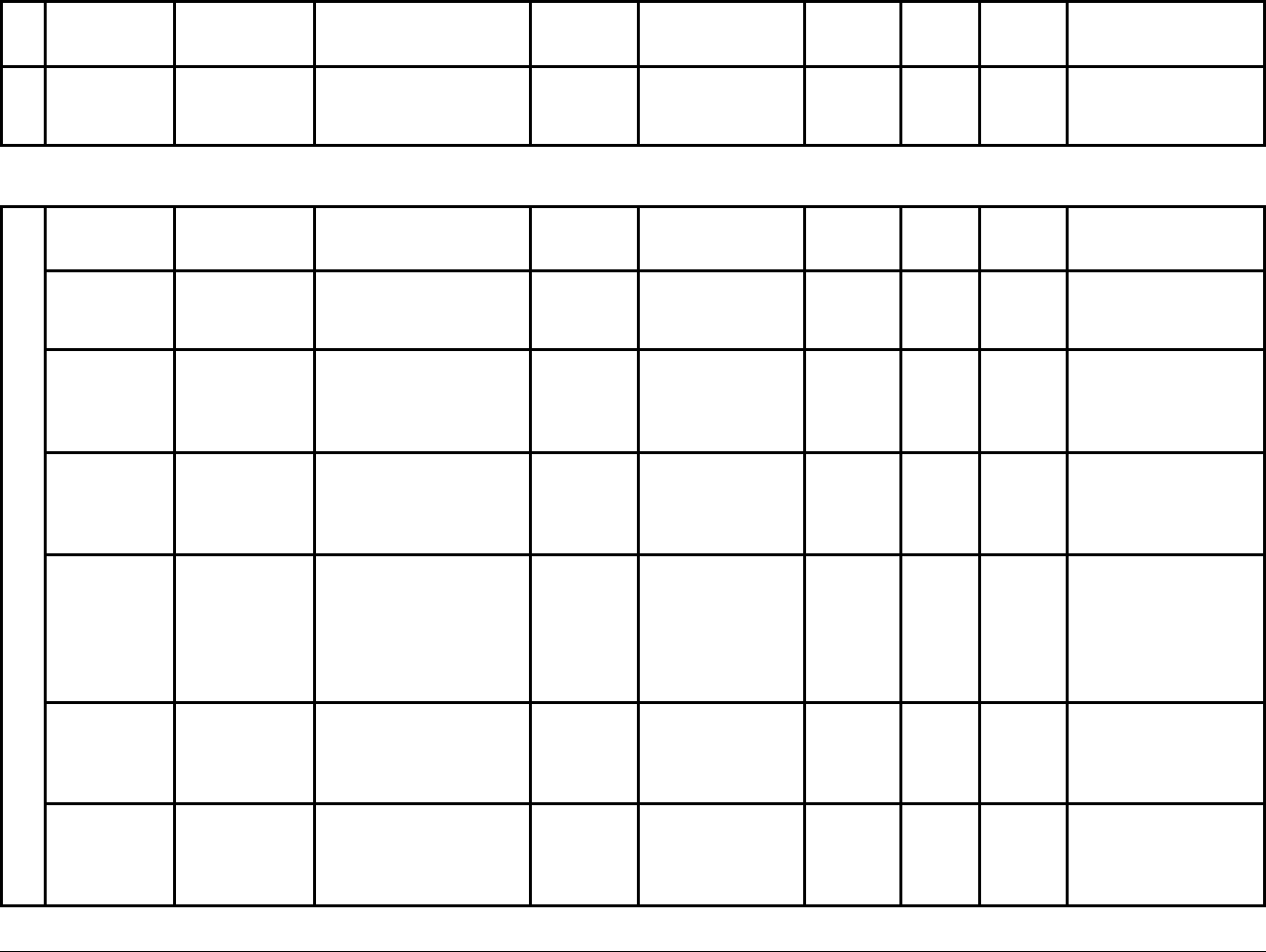

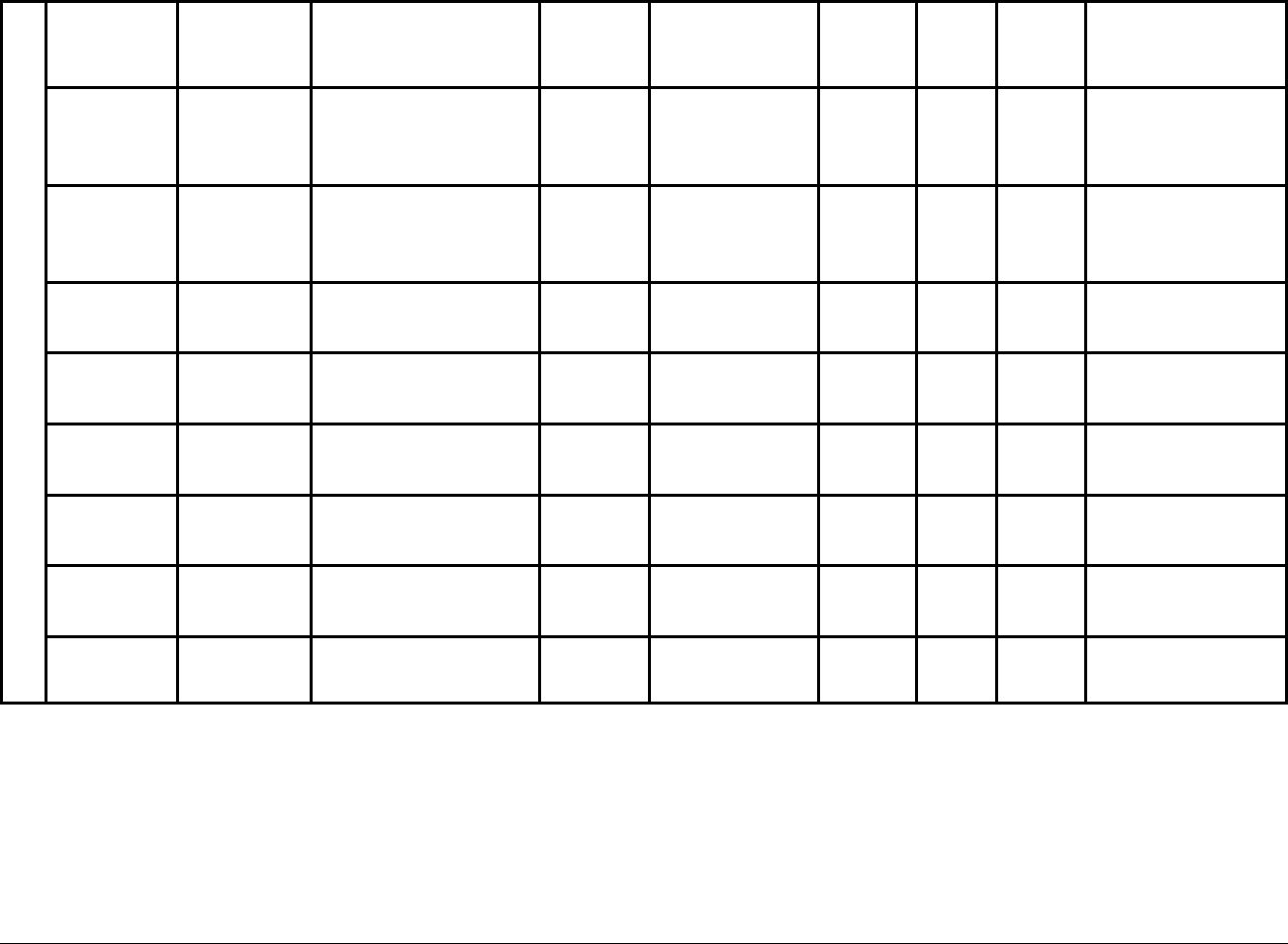

Appendix A: Blank Forms from the EPA Service Line Inventory Template .................................... A-1

Appendix B: Case Studies .............................................................................................................. B-1

Appendix C: Instructions for Self-Identifying LSLs and Information When Water System Conducts

Verification .......................................................................................................................... C-1

Appendix D: Summary of Lead Ban Provisions by State ................................................................ D-1

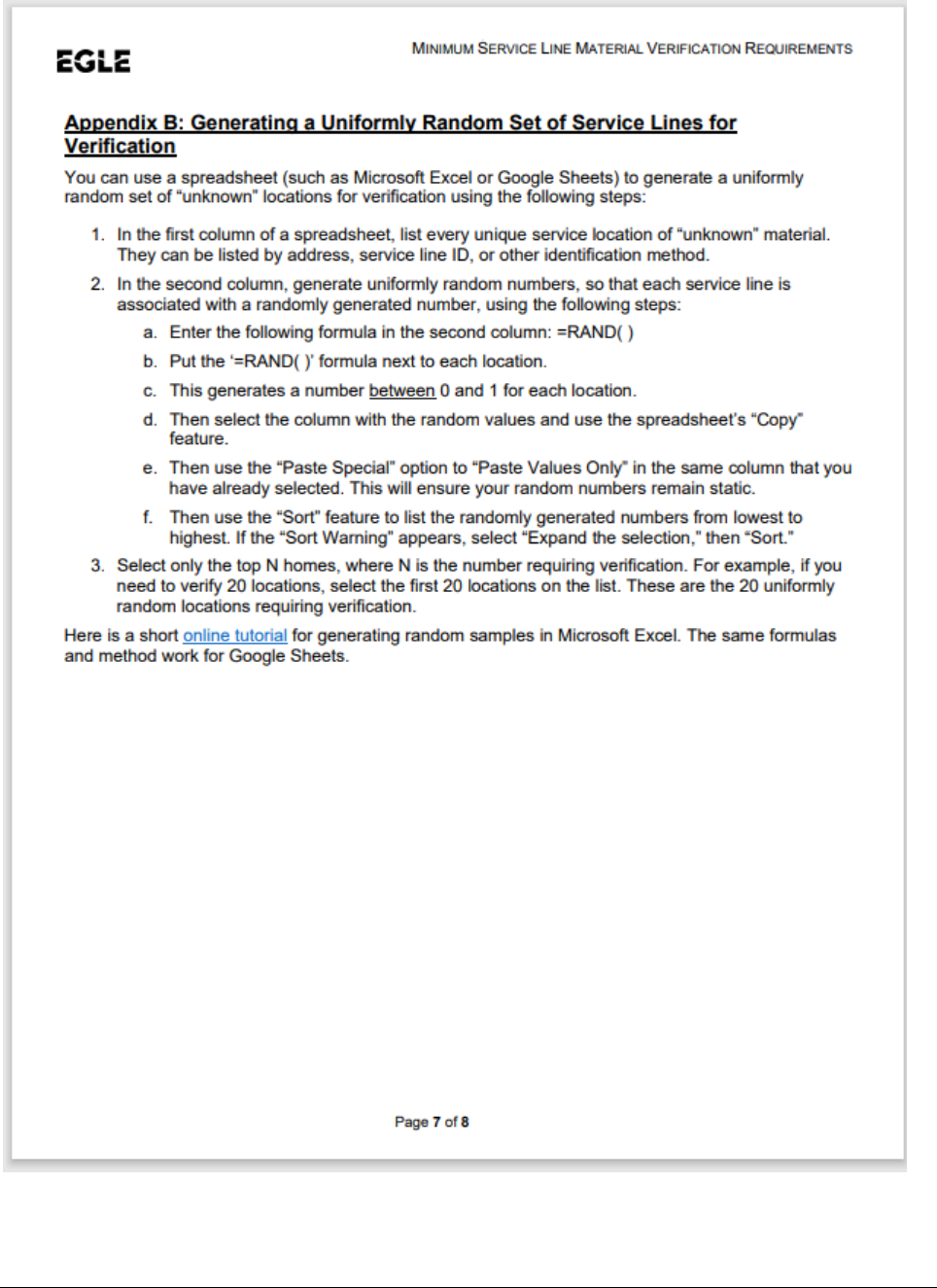

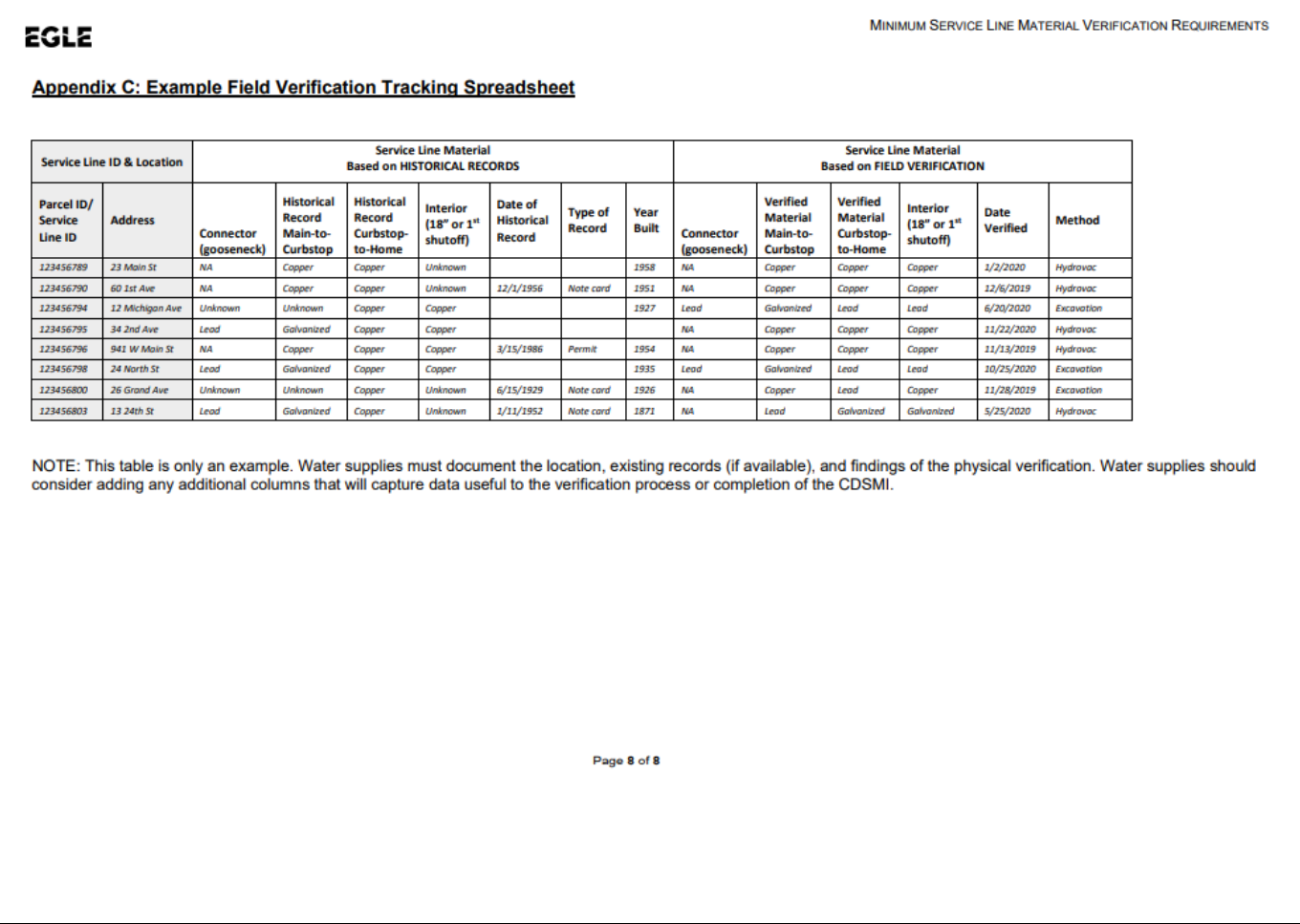

Appendix E: Michigan Minimum Service Line Verification Requirements .................................... E-1

Appendix F: Examples of Data Quality Disclaimer Language ........................................................ F-1

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining vi August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

List of Exhibits

Exhibit 1-1: LCRR Inventory Requirements ................................................................................... 1-4

Exhibit 2-1: Required Inventory Materials Classifications ............................................................. 2-2

Exhibit 2-2: Example of Service Line Ownership Distinction between the Water System and

Customer ...................................................................................................................................... 2-4

Exhibit 2-3: Classifying Service Line Materials When Ownership is Split According to the LCRR 40

CFR §141.84(a)(4) ......................................................................................................................... 2-5

Exhibit 3-1: Inventory Lifecycle ..................................................................................................... 3-2

Exhibit 3-2: Organization of EPA Inventory Template ................................................................... 3-5

Exhibit 4-1: Requirements for Historical Records Review for Initial Inventory Development under

the LCRR ....................................................................................................................................... 4-2

Exhibit 4-2: Illustrative excerpts from municipal codes, specifying that lead was allowed or

required as pipe material for service lines .................................................................................... 4-6

Exhibit 4-3: Water System Record Examples and Uses ................................................................. 4-8

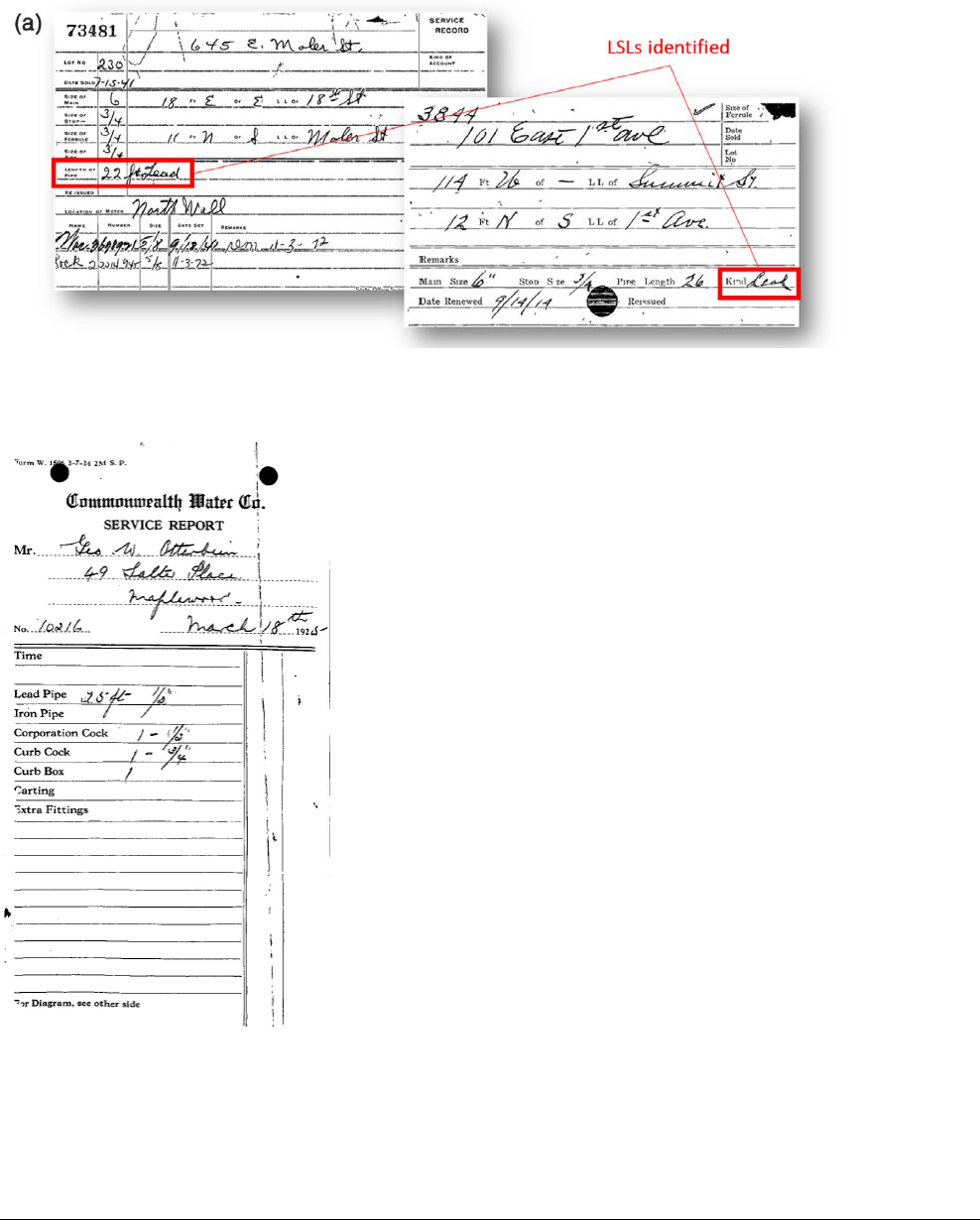

Exhibit 4-4: Examples of Tap Cards with Lead Listed as Service Line Material .............................. 4-9

Exhibit 5-1: Examples of Commonly Found Pipe Materials ........................................................... 5-2

Exhibit 5-2: Example of Wiped Lead Joint ..................................................................................... 5-3

Exhibit 5-3: Example of Location of Exposed Service Line in Basement ........................................ 5-4

Exhibit 5-4: Example Stop Box Schematic from Des Moines Water Works, Iowa ......................... 5-8

Exhibit 5-5: Lead Pipe at a Curb Stop ............................................................................................ 5-9

Exhibit 5-6: Examples CCTV Camera Pictures for LSL, non-LSL, and Unable to Determine ........... 5-9

Exhibit 5-7: Example of Sequential Sampling .............................................................................. 5-11

Exhibit 5-8: Comparison of Service Line Identification Techniques (Hensley et al., 2021) .......... 5-16

Exhibit 6-1: Service Material Screening Process Based on Records .............................................. 6-3

Exhibit 6-2: LSLR Collaborative Flow Chart ................................................................................... 6-4

Exhibit 6-3: Recommended Documentation for Systems with all Non-Lead Service Lines ........... 6-9

Exhibit 7-1: Greater Cincinnati Water Works Service Line Information Map ................................ 7-7

Exhibit 7-2: Examples of Online Data Sharing Alternatives ........................................................... 7-8

Exhibit 7-3: Denver Water’s Lead Service Line Replacement Map .............................................. 7-10

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining vii August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Acronyms

µg/L

Micrograms per liter

ACHD

Allegheny County Health Department

ASDWA

Association of State Drinking Water Administrators

AWWA

American Water Works Association

BIL

Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

CBI

Curb Box Inspection

CCR

Consumer Confidence Report

CCTV

Closed-Circuit Television

CFR

Code of Federal Regulations

CMMS

Computerized Maintenance Management System

CWS

Community Water System

DWINSA

Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment

DWSRF

Drinking Water State Revolving Fund

EDF

Environmental Defense Fund

EGLE

Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy

EPA

United States Environmental Protection Agency

FTP

File Transfer Protocol

GCWW

Greater Cincinnati Water Works

GIS

Geographic Information System

GPR

Ground Penetrating Radar

GPS

Global Positioning System

GRR

Galvanized Requiring Replacement

GRWS

Grand Rapids Water System

IIJA

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

LCR

Lead and Copper Rule

LCRI

Lead and Copper Rule Improvements

LCRR

Lead and Copper Rule Revisions

LSL

Lead Service Line

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining viii August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

LSLR

Lead Service Line Replacement

LWC

Louisville Water Company

NPR

National Public Radio

NTNCWS

Non-Transient Non-Community Water System

OMB

Office of Management and Budget

ORP

Oxidation-Reduction Potential

PWS

Public Water System

PWSA

Pittsburgh Water & Sewer Authority

PWSID

Public Water System Identification Number

SDWA

Safe Drinking Water Act

SOP

Standard Operating Procedure

USEPA

United States Environmental Protection Agency

WIIN

Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining ix August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Glossary

Term Definition

1

Curb stop

An exterior valve located at or near the property line that is used to turn on and

off water service to the building.

2

Community water

system

A public water system that serves at least 15 service connections used by year-

round residents or regularly serves at least 25 year-round residents (40 CFR

§141.2).

Full lead service line

replacement

Replacement of a lead service line (as well as galvanized service lines requiring

replacement) that results in the entire length of the service line, regardless of

service line ownership, meeting the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) Section

1417 definition of lead free

3

applicable at the time of the replacement. See 40

CFR §141.2 for the full regulatory definition.

Galvanized requiring

replacement

A galvanized service line that is or was at any time downstream of a lead service

line or is currently downstream of a lead status unknown service line. If the

water system is unable to demonstrate that the galvanized service line was

never downstream of a lead service line, it must presume there was an

upstream lead service line (40 CFR §141.84(a)(4)(ii)).

Galvanized service line

Iron or steel piping that has been dipped in zinc to prevent corrosion and

rusting (40 CFR §141.2).

Gooseneck, pigtail, or

connector

A short section of piping, typically not exceeding two feet, which can be bent

and used for connections between rigid service piping. For purposes of this

subpart, lead goosenecks, pigtails, and connectors are not considered to be part

of the lead service line but may be required to be replaced pursuant to

§141.84(c)

4

(40 CFR §141.2).

Lead service line

A portion of pipe that is made of lead, which connects the water main to the

building inlet. A lead service line may be owned by the water system, owned by

the property owner, or both. For the purposes of this subpart, a galvanized

service line is considered a lead service line if it ever was or is currently

downstream of any lead service line or service line of unknown material. If the

only lead piping serving the home is a lead gooseneck, pigtail, or connector, and

it is not a galvanized service line that is considered a lead service line, the

service line is not a lead service line (40 CFR §141.2).

Lead status unknown

service line

A service line where the material is not known to be lead, galvanized requiring

replacement, or a non-lead service line, such as where there is no documented

evidence supporting material classification. It is not necessary to physically

verify the material composition (e.g.,, copper or plastic) of a service line for its

lead status to be identified (e.g., records demonstrating the service line was

installed after a municipal, state, or federal lead ban

3

) (40 CFR §141.2).

Non-lead

A service line that is determined through an evidence-based record, method, or

technique not to be lead or galvanized requiring replacement (40 CFR §

141.84(a)(4)(iii)).

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining x August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Term Definition

1

Non-transient non-

community water

system

A public water system that is not a community water system and regularly

serves at least 25 of the same persons over 6 months per year (40 CFR §141.2).

Service line

The pipe connecting the water main to the interior plumbing in a building.

2

The

service line may be owned wholly by the water system or customer, or in some

cases, ownership may be split between the water system and the customer.

State

State means the agency of the State or Tribal government that has jurisdiction

over public water systems. During any period when a State or Tribal

government does not have primary enforcement responsibility pursuant to

Section 1413 of the Act, the term “State” means the Regional Administrator,

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (40 CFR §141.2).

Water main

A pipe that conveys water to a connector or customer's service line. In

residential areas, it is usually located underground.

2

Water meter

An instrument, mechanical or electronic, used for recording the quantity of

water passing through a particular pipeline or outlet.

2

Notes:

1

Definitions without a regulatory citation are recommended definitions for use in this guidance document.

2

Source: Seventh Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment: Lead Service Line

Inventory for America’s Water Infrastructure Act – State Survey Instruction (USEPA, 2021b).

3

In 1986, Congress amended the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), prohibiting the use of pipes, solder, or

flux that were not “lead free” in public water systems or plumbing in facilities providing water for human

consumption. See Appendix D: Summary of Lead Ban Provisions by State. At the time, "lead free” was

defined as solder and flux with no more than 0.2 percent lead and pipes with no more than 8 percent. In

2011, Congress passed the Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act (RLDWA) that amended Section 1417

of SDWA and updated the definition for “lead free” as a weighted average of not more than 0.25 percent

lead calculated across the wetted surfaces of a pipe, pipe fitting, plumbing fitting, and fixture and not

containing more than 0.2 percent lead for solder and flux. On September 1, 2020, EPA published the final

regulation “Use of Lead Free Pipes, Fittings, Fixtures, Solder, and Flux for Drinking Water” to make

conforming changes to existing regulations based on the RLDWA.

https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/01/2020-16869/use-of-lead-free-pipes-fittings-

fixtures-solder-and-flux-for-drinking-water

4

Section 141.84(c) of the January 15, 2021 Lead and Copper Rule Revisions (LCRR) specifies the operating

procedures for replacing lead goosenecks, pigtails, or connectors. The LCRR is under revision and all rule

provisions except for the initial inventory requirements may be subject to change.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 1-1 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Chapter 1: Introduction

This introductory chapter provides:

• The benefits of a comprehensive and accurate service line inventory (Section 1.1);

• The purpose of the guidance and its intended audience (Section 1.2);

• An overview of the inventory and related requirements of the January 15, 2021 Lead and

Copper Rule Revisions (LCRR) and related requirements under the Lead and Copper Rule

(LCR) (Section 1.3); and

• A brief discussion of how the remainder of the guidance is organized (Section 1.4).

1.1 The Benefits of a Comprehensive and Accurate Inventory

Given the many benefits of LSLR,

EPA encourages water systems to

begin LSLR as soon as possible,

regardless of the stage of their

inventory development.

Service line inventories are the foundation from which

water systems take action to address a significant

source of lead in drinking water - lead service lines

(LSLs). Establishing an inventory of service line

materials and identifying the location of LSLs is a key

step in getting them replaced and protecting public

health. Lead service line replacement (LSLR) is not

dependent on knowing the location of all LSLs; in fact,

simultaneously developing an inventory while conducting LSLR can have many benefits. For

example, systems can save costs by replacing LSLs when crews find them onsite during service line

investigations. Systems can also leverage the opportunity for LSLR by seeking customer consent

and private property access during service line investigation. Replacing LSLs in a safe and prompt

manner while crews are in the field for inventory development provides an opportunity for public

health benefits for consumers by more quickly eliminating this potential source of lead exposure

from drinking water.

Congress recognized the importance of LSLR when it appropriated supplemental Drinking Water

State Revolving Fund (DWSRF) funding as part of the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) (P.L.

117-58). The BIL contains a historic $15 billion in dedicated funding through the DWSRF for LSL

identification and replacement. This funding is being provided to states with no match

requirement. The BIL also provided $11.7 billion over five years to enhance DWSRF base funding.

EPA is collaborating with state DWSRF programs to share models, guidance, and build state

capacity to assist local communities and ensure LSL funding is effectively and equitably deployed

(USEPA, 2022). DWSRF BIL LSLR funding, DWSRF BIL General Supplemental funding, and base

appropriations for the DWSRF can all be used for LSL identification, such as service line material

classification and validation, and replacement. The new resources available under BIL, in

particular, provide a tremendous opportunity to make rapid progress on permanently removing a

significant source of lead in drinking water and achieving major improvements in public health.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 1-2 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

For the DWSRF, 49 percent of the DWSRF funding must be provided to disadvantaged

communities. Other federal programs also have available funding available for LSLR and related

technical assistance.

1

A comprehensive and accurate inventory has many additional benefits beyond regulatory

compliance. Inventorying service line material permits notification to consumers about potential

lead risks affecting them, which can facilitate customer actions to reduce lead in drinking water,

including flushing, use of filters certified to reduce lead, and customer-initiated LSLR. Inventories

allow water systems to publicly track their progress on LSL identification and replacement,

engaging the community and enhancing transparency. Inventories can also help water systems

and consumers determine the source of high lead levels in drinking water at a home or building

and the possible solutions for reducing exposure. Water systems with inventory information can

also proactively mitigate lead exposure caused by disturbances of a lead or galvanized requiring

replacement (GRR) service line, for example, during street construction. Inventories can also make

LSLR programs more efficient. Even incomplete inventories may create cost-saving opportunities

for water systems by better targeting locations served by LSLs, stretching the value of internal or

external funding that water systems receive, such as from the BIL. In addition, service line

inventories can help inform decisions for other drinking water rules and could inform future needs

surveys and potential future costs.

1.2 Purpose and Audience

The purpose of this document is to guide water systems as they develop and maintain service line

inventories and to provide states with needed information for oversight and reporting to EPA. The

guidance contained in this document can also position water systems to begin replacing LSLs as

soon as possible. Locating LSLs is the first and critical step to replacing them; however, water

systems do not need to complete the entire inventory process before designing and implementing

their LSLR programs.

This guidance covers the lifecycle of the inventory, including inventory creation, material

investigations, system reporting, state review, public accessibility of service line information, and

service line consumer notification. In addition, the guidance provides best practices, case studies,

and templates related to topics such as the classification of unknowns, goosenecks, and

galvanized plumbing; best practices for service line material investigations; inventory form and

format; inventory accessibility; tools to support inventory development and data tracking; and

ways to prioritize service line investigations.

1

Additional information is available at https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/funding-lead-service-

line-replacement.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 1-3 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

The practices surrounding service line material inventories are rapidly evolving as water systems

create their inventories and improve them over time. Additionally, emerging research on service

line identification methods is ongoing. Given the potential for new, relevant information to

become available, EPA anticipates that future updates to the guidance are possible. In addition,

although EPA anticipates this guidance will be useful for water systems of all sizes, EPA intends to

develop an additional tailored guidance for small community water systems (CWSs) and non-

transient non-community water systems (NTNCWSs).

1.3 Overview of Regulatory Requirements and LCRR Review

Section 1.3.1 provides an overview of the initial inventory requirements specified in the January

15, 2021 LCRR. Section 1.3.2 provides information on EPA’s review of the LCRR and plans to

develop the Lead and Copper Rule Improvements (LCRI). Section 1.3.3 discusses inventory-related

regulatory requirements under the LCR.

1.3.1 Overview of the LCRR Inventory Requirements

EPA published the LCRR in the Federal Register on January 15, 2021 (USEPA, 2021c). It applies to

all CWSs and NTNCWSs. The initial inventory requirements of the LCRR specify:

• Information that water systems must include in their service line inventory,

• When water systems must submit their initial inventories to their primacy agency

2

,

• Requirements for water systems to make their information publicly accessible and to

notify all persons served by the water system at the service connection with a lead, GRR,

or lead status unknown service line, and

• Reporting requirements for states.

Exhibit 1-1 provides a summary of these requirements with the relevant LCRR citations and the

section(s) in this guidance with additional information. Note that Exhibit 1-1 includes only the

LCRR initial inventory requirements that EPA stated would be retained for the LCRI. The LCRR

contains additional requirements that may be subject to change under the LCRI and are therefore

not included in the exhibit below.

2

EPA delegates primacy, which is primary enforcement responsibility to implement SDWA’s Public Water System

Supervision Program, for public water systems to states, territories, and Indian tribes if they meet special

requirements. Throughout this guidance, the terms “state” or “states” are used to refer to all types of primacy

agencies including U.S. territories, Indian tribes, and EPA Regions.

Note that this guidance addresses inventory requirements of the LCRR

only. All LCRR requirements aside from the initial inventory are subject to

change under the LCRI. See Section 1.3.2 for discussion.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 1-4 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

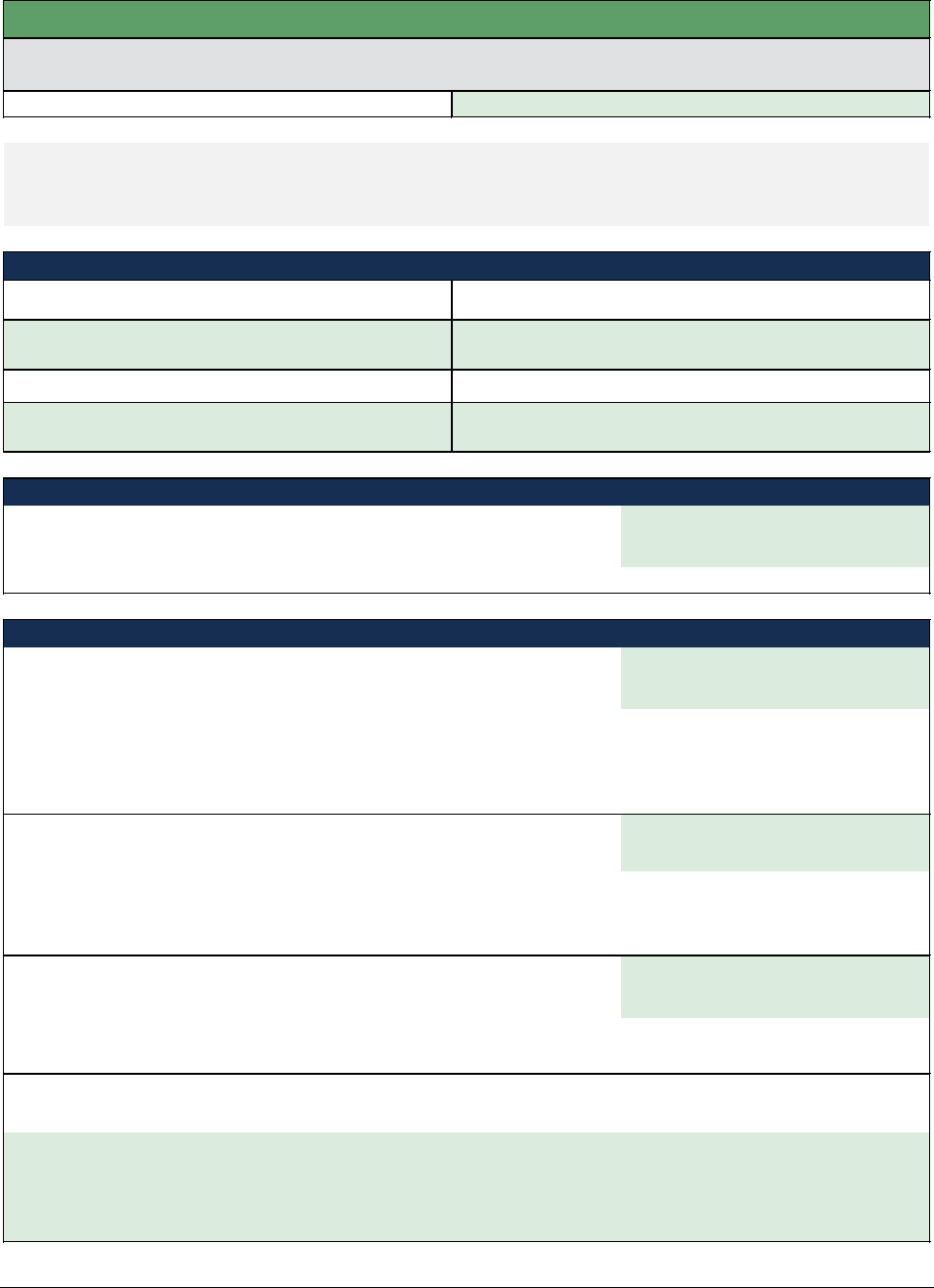

Exhibit 1-1: LCRR Inventory Requirements

Inventory Requirement 40 CFR Citation

Information

Provided in:

WATER SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS

Inventory Specifications

Material Classification: Classify each service line or portion of

the service line where ownership is split as lead, galvanized

requiring replacement, non-lead, or lead status unknown.

§141.84(a)(4) Section 2.1

All service lines and ownership: Prepare an inventory that

includes the system- and customer-owned portions of all

service lines in the system’s distribution system.

§141.84(a), (a)(2) Section 2.2

Information to Identify Material: Use previous materials

evaluation, construction and plumbing codes/records, water

system records, distribution system inspections and records,

information obtained through normal operations, and state-

specified information.

§141.84(a)(3),

(a)(5)

Sections 3.4 &

Chapter 4

Deadlines for Submission

Initial Inventory: Submit an initial inventory or demonstrate

the absence of LSLs by October 16, 2024.

§141.80(a)(3)

1

Se

ction 1.3.2 &

Section 6.4

Updates to Primacy Agency: Submit updated inventories to

the primacy agencies annually or triennially based on lead tap

sampling frequency, but not more frequently than annually

Water systems that have demonstrated the absence of LSLs

by October 16, 2024 are not required to provide an update.

However, if these systems subsequently find any LSL or

galvanized requiring replacement service line, they have 30

days to notify the state and prepare an updated inventory on

a schedule established by the state.

§141.90(e)(3),

§141.90(e)(3)(ii)

Se

ctions 6.3 & 6.6

Public Accessibility and Consumer Confidence Report

Public Accessibility: Make the inventory publicly available and

include a locational identifier for LSLs and galvanized

requiring replacement. Water systems serving more than

50,000 people must provide inventories online.

§141.84(a)(8)

Section 2.3 &

Chapter 7

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 1-5 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Inventory Requirement

40 CFR Citation

Information

Provided in:

Consumer Confidence Report (applies to CWSs only):

• CWSs with LSLs: Indicate how the public can access

the service line inventory information.

• CWSs with only non-lead service lines: Provide a

statement there are no LSLs and how to access the

service line inventory (or a statement in lieu of the

publicly accessible inventory with a description of

methods used to make this determination in 40 CFR

§141.84(a)(9)).

§141.84(a)(9),

§141.153(d)(4)(xi)

Section 7.4

Service Line Consumer Notification

Provide notification to persons served by the water system at

the service connection with an LSL, GRR, or lead status

unknown service line. If the water system serves communities

with a large proportion of non-English speaking consumers, as

determined by the state, public education materials must be

in appropriate languages or contain a telephone number or

address where persons served may contact the water system

to obtain a translated copy of the materials or to request

assistance in the appropriate language.

Timing: Notification within 30 days after completing of initial

inventory and repeated annually until only non-lead remains.

For new customers, water systems must also provide this

notice at the time of service initiation.

Content: Statement about service line material, lead health

effects, and steps to minimize lead exposure in drinking

water. If:

• Confirmed LSL, must include opportunities to replace

the LSL, any available financing programs, and

statement that the system must replace its portion if

property owners notify the system they are replacing

their portion.

• GRR, must also include opportunities for service line

replacement.

• Lead status unknown, must also include opportunities

to verify the material of the service line.

Delivery: By mail or by another method approved by the

state.

Reporting to states: Demonstrate that the water system

delivered the notification and provide a copy of the

§141.85(a)(1)(ii),

§141.85(e) &

§141.90(f)(4)

Section 6.5

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 1-6 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Inventory Requirement

40 CFR Citation

Information

Provided in:

notification and information materials to their states annually

by July 1 for the previous calendar year.

STATE REPORTING

Reporting to EPA: For each water system, the number of lead,

galvanized requiring replacement, and lead status unknown

service lines in its distribution system, reported separately.

§142.15(c)(4)(iii)(D)

EPA will include

additional details in

the data entry

instructions

guidance for the

LCRR.

Special Primacy: The LCRR specifies special primacy

requirements for states to adopt in 40 CFR §142.16(d)(5) that

include: (1) providing or requiring the review of any resource,

information, or identification method for the development of

the initial inventory or inventory updates, and (2) requiring

water systems whose inventories contain only non-lead

service lines and the water system subsequently finds an LSL

to prepare an updated inventory on a schedule determined

by the state.

§142.16(d)(5)

Chapters 4 – 6

EPA plans to include

additional

information in a

separate state

implementation

guidance.

Notes:

1

On June 16, 2021, EPA published a rule to extend the compliance date from January 16, 2024 to October 16,

2024 (40 CFR §141.90(e)(1), USEPA, 2021d).

Note that this guidance uses the terms “system-owned” and “customer-owned” because they are

consistent with the LCRR language. EPA recognizes that states and systems may use other terms

to describe ownership status such as “public” and “private” or other terms besides “ownership” to

describe the division of responsibility between the water system and the customer. EPA

recommends water systems using different terminology to provide clear explanations of those

terms to the state and the public.

1.3.2 Outcome of EPA Review of the LCRR

On June 16, 2021, EPA published the agency's decision to delay the effective and compliance dates

of the LCRR, published on January 15, 2021. The effective date was extended from March 16, 2021

to December 16, 2021, while the compliance date was extended from January 16, 2024 to

October 16, 2024 to ensure drinking water systems and primacy states continued to have the full

States may have laws or regulations for initial service line inventories that are

more stringent than federal requirements. For the most accurate and up-to-date

requirements, systems should reach out to their state primacy agencies.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 1-7 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

three years provided by the Safe Drinking Water Act to take actions needed for regulatory

compliance. They delay allowed time for EPA to review the LCRR in accordance with Presidential

directives issued on January 20, 2021, to the heads of federal agencies to review certain

regulations and conduct important consultations with affected parties (USEPA, 2021d). The

agency's review included a series of virtual public engagements to hear directly from a diverse set

of stakeholders.

EPA published the outcome of its review on December 17, 2021. The review stated that EPA

actions to protect the public from lead in drinking water should consider the following priority

areas for improvements: replacing 100 percent of LSLs is an urgently needed action to protect all

Americans from the most significant source of lead in drinking water systems; equitably improving

public health protection for those who cannot afford to replace the customer-owned portions of

their LSLs; improving the methods to identify LSLs and trigger action in communities that are most

at risk of elevated drinking water lead levels; and exploring ways to reduce the complexity of the

regulations. In the notice, EPA explained it would also consider changes to other areas of the rule

to equitably improve health protections and improve implementation of the rule to ensure that it

prevents adverse health effects of lead to the extent feasible (USEPA, 2021a). This could include

changes to the requirements applicable to the inventory updates.

To achieve these policy objectives, EPA announced its decision to proceed with a proposed rule

that would revise the LCRR while allowing the January 2021 rule to take effect. Through the LCRI,

EPA stated that it does not expect to propose changes related to the initial service line inventory

requirements because continued progress to identify LSLs is integral to lead reduction efforts

regardless of potential revisions to the rule. The LCRR effective date is December 16, 2021, and

the compliance date is October 16, 2024. In the review notice, EPA also highlighted non-regulatory

actions that EPA and other federal agencies can take to reduce exposure to lead in drinking water.

1.3.3 Related Requirements under the LCR

As mentioned in the previous section, EPA reviewed the requirements in the LCRR and published

its intent to revise the rule with the exception of the initial inventory requirements (USEPA,

2021a). Thus, this document focuses on guidance related to the LCRR initial inventory

requirements, while also including general best practices applicable to the later stages of the

inventory lifecycle.

This section describes existing LCR requirements that rely on service line inventory information

and provides recommendations on how these requirements can be supported by initial inventory

efforts. Water systems must comply with the requirements of the LCR (40 CFR §§141.80-141.91 as

codified on July 1, 2020) between December 16, 2021 and October 16, 2024 (40 CFR

§141.80(a)(3)).

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 1-8 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Inventory-Related Requirements in the Event of Action Level Exceedance

Under the LCR (40 CFR §141.84(b)), systems subject to LSLR requirements

3

must replace annually

at least seven percent of the initial number of LSLs in their distribution system. The initial number

of LSLs is the number of lead lines in place at the time the replacement program begins. Water

systems must identify the initial number of LSLs in their distribution system under this

requirement. EPA recommends that systems use information gathered for the initial inventory

under the LCRR to help identify the required initial number of LSLs.

How the Inventory Relates to the Tap Monitoring Requirements

Required lead and copper tap monitoring under the LCR is based on a tiering system for

prioritizing sample sites (40 CFR § 141.86(a)). Single family homes with LSLs are in the highest tier

(i.e., Tier 1), meaning systems should prioritize these locations for lead and copper tap monitoring.

Systems may gather more information on the location of LSLs under their initial inventory efforts.

1.4 Document Organization

The remainder of this document is organized as follows:

• Chapter 2: Elements of the Inventory includes information that must be included in the

service line inventory to meet LCRR requirements as well as additional information EPA

recommends that water systems consider tracking in their inventory.

• Chapter 3: Inventory Planning includes approaches for developing an inventory,

considerations for choosing an inventory format, procedures for collecting information

during normal operation, and guidelines for developing partnerships with third parties.

• Chapter 4: Historical Records Review summarizes the rule requirements for reviewing

historical records and provides additional recommendations on how the various types of

historical records can be used and where to find them.

• Chapter 5: Service Line Investigation Methods summarizes and compares service line

identification methods, including visual inspection, water quality sampling, excavation,

statistical data analyses, and emerging methods.

• Chapter 6: Developing and Updating the Inventory provides recommendations for

classifying service line materials, planning for proactive investigations, submitting the

initial inventory, and inventory updates. It includes requirements and recommendations

specific to systems with no LSLs and provides guidance to states related to inventory

3

Under the LCR, systems that exceeded the lead action level of 15 µg/L based on their 90

th

percentile sample result

after installing corrosion control and/or source water treatment (whichever sampling occurred later) are required to

replace 7 percent of their LSLs annually until they no longer exceeded the lead action level for two consecutive

monitoring periods (40 CFR §141.84(a)).

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 1-9 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

review and reporting. This chapter also contains requirements and recommendations for

notifying customers with LSLs, GRR, or unknown service lines.

• Chapter 7: Public Accessibility includes LCRR requirements for water systems to make

their inventory publicly accessible and provides suggestions for inventory content and

effective presentation, promoting public input, considerations for states, and Consumer

Confidence Report inventory-related requirements.

• Chapter 8: References provides a full list of references that were used in the

development of this document.

This guidance also includes key points to remember at the end of Chapters 1 through 7. In

addition, these chapters are supported by the following appendices:

• Appendix A provides blank forms from EPA’s Service Line Inventory Template, which is a

companion tool to help water systems and states comply with the LCRR service line

inventory requirements. The blank forms can be used for documenting inventory

methods and an inventory summary. The appendix also contains a blank form for the

state review checklist.

• Appendix B includes case studies for three water systems that have begun developing

their service line inventories.

• Appendix C includes example instructions on how customers can identify their service

line materials and example customer materials when the water system conducts the

material service line verification of the customer-owned portion.

• Appendix D provides a summary of 1986 SDWA lead ban provisions by state.

• Appendix E includes Michigan’s Minimum Service Line Verification Requirements.

• Appendix F includes examples of data quality disclaimers regarding the accuracy of the

inventory provided to the public.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 1-10 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Key Points to Remember

LCRR Requirements

All CWSs and NTNCWSs must develop an inventory of service lines that meets the LCRR

requirements, including service line materials classification, information sources, and

public accessibility (40 CFR § 141.84(a)).

Water systems must submit their initial inventories to their state by October 16, 2024 (40

CFR § 141.84(a)(1)) and 141.90(e)(1)).

All CWSs and NTNCWSs must notify all persons served by the water system at the service

connection with a lead, GRR, or lead status unknown service line within 30 days of

completing their service line inventory (40 CFR § 141.85(e)).

All LCRR requirements other than the initial inventory requirements are subject to change

under the LCRI.

Recommendations (Not Required under the LCRR)

Water systems should not wait until their inventories are complete to begin conducting

LSLR. Replacing LSLs while developing the inventory may create synergies or introduce

opportunities for cost-savings.

This guidance covers the lifecycle of the inventory, including inventory creation, inventory

updates, material investigations, system reporting, state review, and public accessibility

of service line information. The inventory is based on the best available data and should

improve over time with updated information.

States may have passed laws or regulations for a service line inventory that are more

stringent than the federal inventory requirements.

For water systems, a comprehensive and accurate service line inventory will facilitate

LCRR compliance, improve LSLR program efficiency, provide greater public health

protection, potentially assist in obtaining external funds for inventory development and

LSLR, and provide potential cost savings.

For states, a robust inventory will provide information for oversight and reporting.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 2-1 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Chapter 2: Elements of the Inventory

This chapter contains the required elements of the service line inventory based on the January 15,

2021 Lead and Copper Rule Revisions (LCRR) (USEPA, 2021c) and is organized as follows:

• Section 2.1 presents requirements and recommendations for materials classification for

service lines and other related infrastructure,

• Section 2.2 presents requirements and recommendations for what to include in the

inventory,

• Section 2.3 includes a discussion of location identifiers for service lines, and

• Section 2.4 provides other suggested service line information for inclusion in the

inventory.

2.1 Inventory Materials Classifications

This section summarizes the required service line material classifications and presents additional

classifications and subclassifications for states and water systems to consider.

2.1.1 Required Service Line Inventory Material Classifications

Under the LCRR, the inventory must use one of the following four material classifications to describe

the entire service line, including separate material classifications for the water system-owned and

customer-owned portions of each service line where ownership is split:

• Lead

• Galvanized requiring replacement (GRR)

• Non-lead (or the actual material, such as copper or plastic)

• Lead status unknown service lines (or unknown)

4

Exhibit 2-1 provides the required criteria for assigning each of the four material classifications and

additional information that may be helpful to states and water systems.

4

This guidance document uses the term lead status unknown interchangeably with unknown.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 2-2 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

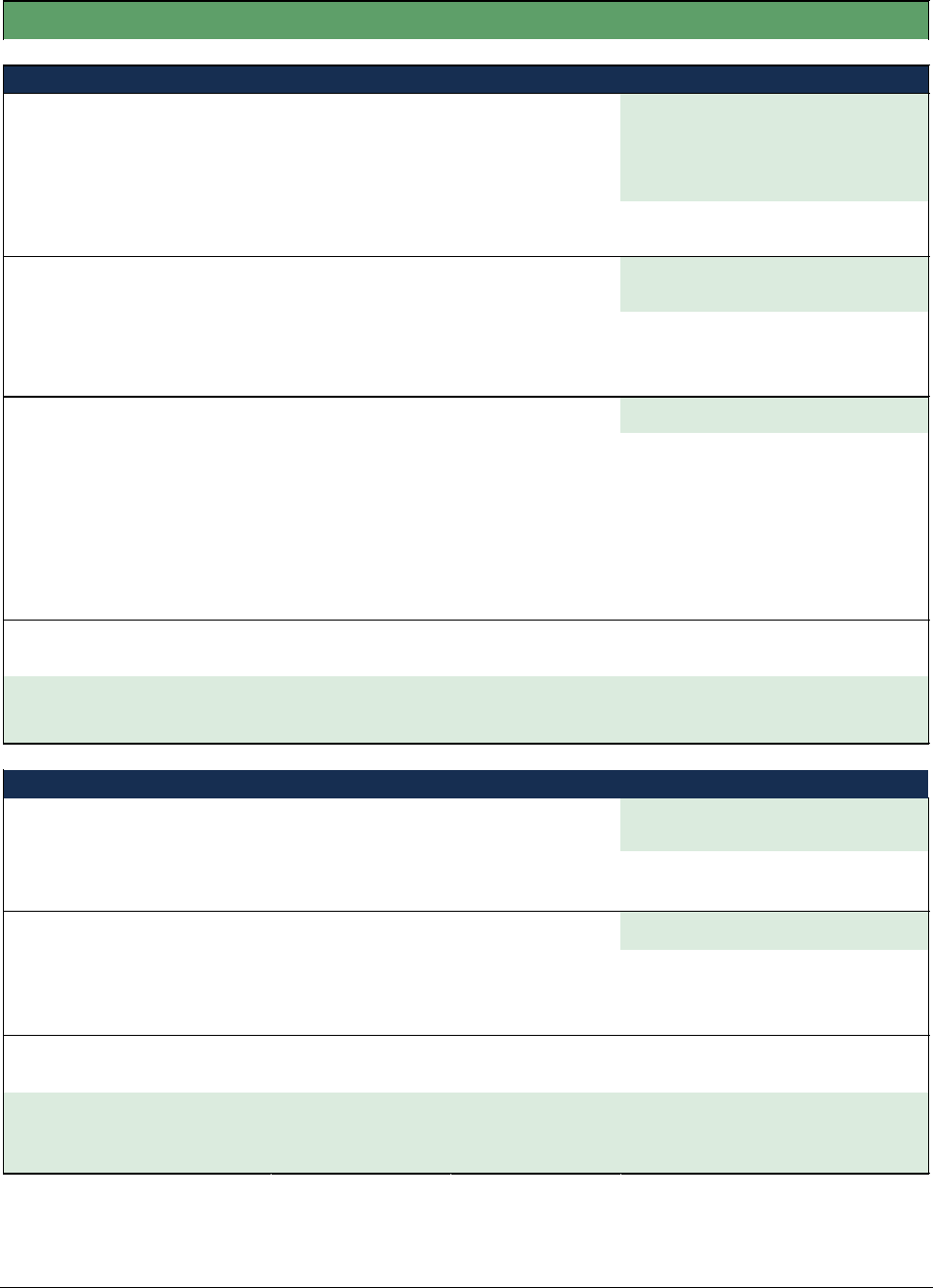

Exhibit 2-1: Required Inventory Materials Classifications

Material

Classification

Use This Classification If:

Lead

The service line is made of lead (40 CFR §141.84(a)(4)(i)).

Keep in Mind:

• The LCRR updates the definition of a lead service line (LSL) as “a portion of pipe that

is made of lead, which connects the water main to the building inlet” (40 CFR

§141.2).

• If the only lead pipe serving the building is a lead gooseneck, pigtail, or connector

1

,

the service line is not considered an LSL under the initial inventory requirements of

the LCRR. EPA recommends that the system track the material of all components

that potentially contain lead, including connectors.

2

Galvanized

Requiring

Replacement

(GRR)

The galvanized service line is or ever was at any time downstream of an LSL or is

currently downstream of a lead status unknown service line. If the water system is

unable to demonstrate that the galvanized service line was never downstream of an LSL,

it must presume there was an upstream LSL (40 CFR §141.84(a)(4)(ii)).

Keep in Mind:

• Galvanized service lines that are or ever were downstream from an LSL can adsorb

lead and contribute to lead in drinking water.

• An example of a GRR service line is when the customer-owned portion from the

meter to the building is galvanized, and the system-owned portion from the water

main to the meter was previously lead but has been replaced. The customer-owned

portion of the service line would be GRR.

• Under the initial inventory requirements of the LCRR, a galvanized service line that

was never downstream of an LSL but is downstream or previously downstream of a

lead gooseneck, pigtail, or connector is not considered GRR. However, systems

should check with their states if they have more stringent requirements.

Non-Lead

The service line is determined through an evidence-based record, method, or technique

that it is not lead or GRR (40 CFR §141.84(a)(4)(iii)).

Keep in Mind:

• If a system can demonstrate that a galvanized service line was never downstream of

an LSL, it may be classified as non-lead.

• The water system may classify the actual material of the service line (for example,

galvanized, plastic, or copper) as an alternative to classifying it as non-lead.

• The term “non-lead” refers to the service line material only and does not include

other potential lead sources present in solder, connectors, and other plumbing

materials.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 2-3 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Material

Classification

Use This Classification If:

Lead Status

Unknown

The service line material is not known to be a lead, GRR, or non-LSL, such as where there

is no documented evidence supporting material classification (40 CFR §141.84(a)(4)(iv)).

Keep in Mind:

• Water systems have the option to use the terminology of unknown instead of lead

status unknown service line (40 CFR §141.84(a)(4)(iv)).

• Water systems may elect to provide more information regarding their unknown

lines as long as the inventory clearly distinguishes unknown service lines from those

where the material has been determined through records or inspections (40 CFR

§141.84(a)(4)(iv)).

Note:

1

A lead gooseneck,

pigtail, or connector is defined as “a short section of piping, typically not exceeding two

feet, which can be bent and used for connections between rigid service piping” (40 CFR §141.2).

2

Some states include lead connectors in their definition of an LSL. In these instances, the state requirements

are more stringent than the LCRR and water systems must follow these requirements.

Exhibit 2-2 is a diagram of a possible division in service line ownership (or responsibility) between

the customer and water utility in which the system-owned portion of the service line is from the

water main to the curb stop and the customer-owned portion is from the curb stop to the water

meter. For some systems, the delineation may be different, (e.g., the ownership or responsibility

distinction is at the water meter or property line). In other instances, the water system may share

ownership with customers, or the water system or customer may have sole ownership of the

service line. Note that ownership of the property on which the service line is located does not

always equate to ownership or responsibility of the service line.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 2-4 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

Exhibit 2-2: Example of Service Line Ownership Distinction between the Water System and

Customer

While the LCRR requires the inventory to categorize each service line or portions of the service

line where ownership is split, a single classification per service line is also needed to support

various LCRR requirements, such as lead service line replacement (LSLR), tap sampling, and risk

mitigation. Systems should follow these guidelines to comply with the LCRR requirements when

classifying the entire service line when ownership is split:

• Service line is lead if either portion is a lead service line (LSL) (40 CFR §141.84(a)(4)(i)).

• Service line is GRR if the downstream portion is galvanized and the upstream portion is

unknown or currently non-lead, but the system is unable to demonstrate that it was

never previously lead (40 CFR §141.84(a)(4)(ii)).

• Service line is lead status unknown if both portions are unknown, or one portion is non-

lead and one portion is unknown (40 CFR §141.84(a)(4)(iv)).

• Service line is non-lead only if both portions meet the definition of non-lead (40 CFR

§141.84(a)(4)(ii)).

EPA recognizes that some segments of the system- or customer-owned service lines could be

made of more than one material. EPA recommends that systems follow the guidelines above to

classify the system-owned or customer-owned portion in these cases. Exhibit 2-3 provides

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 2-5 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

examples for classifying the entire service line for various system-owned and customer-owned

material combinations.

Exhibit 2-3: Classifying Service Line Materials When Ownership is Split According to the

LCRR 40 CFR §141.84(a)(4)

System-Owned Portion Customer-Owned Portion

Classification for Entire Service

Line

Lead Lead Lead

Lead

Galvanized Requiring

Replacement

Lead

Lead Non-lead Lead

Lead Lead Status Unknown Lead

Non-lead Lead Lead

Non-lead and never previously

lead

Non-lead, specifically galvanized

pipe material

Non-lead

Non-lead

Non-lead, material other than

galvanized

Non-lead

Non-lead Lead Status Unknown Lead Status Unknown

Non-lead, but system is unable to

demonstrate it was not previously

Lead

Galvanized Requiring

Replacement

Galvanized Requiring

Replacement

Lead Status Unknown Lead Lead

Lead Status Unknown

Galvanized Requiring

Replacement

Galvanized Requiring

Replacement

Lead Status Unknown Non-lead Lead Status Unknown

Lead Status Unknown Lead Status Unknown Lead Status Unknown

If the only lead pipe serving a building is a lead gooseneck, pigtail, or other connector (i.e., a non-

LSL attached to a lead connector), then the line should not be designated as an LSL in the initial

service line inventory required under the LCRR. The line may be required to be identified

separately by the state. In addition, as will be discussed in more detail in Section 2.1.3, EPA

recommends water systems identify the lines with only these components separately in their

inventory. Also note that service material classifications can change over time as the system

gathers more information and updates the inventory.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 2-6 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

2.1.2 Recommended Subclassifications and Additional Information (Not Required Under

LCRR)

Water systems may also consider going beyond the requirements of the LCRR by subclassifying

service line materials and tracking additional information. These subclassifications are discussed

below and can provide additional information not only to help facilitate material classification, but

also to inform the public about service lines in their homes and community.

Recommended Subclassifications

A Lead Status Unknown’s “LSL Likelihood.” Some water systems have incorporated additional

information that indicates the probable material of an unknown service line, such as an “LSL

Likelihood.” For example, Flint, Michigan, categorized unknowns as low likelihood of lead, medium

likelihood of lead, and high likelihood of lead (see their online map showing these

subclassifications

5

). Systems using predictive models may also assign numerical probabilities to

unknowns representing the probability they are LSLs.

Systems could rely on historical records described in Chapter 4, service line material investigations

described in Chapter 5, and the methodology described in Section 6.1 to determine various

subclassifications of unknown service lines. For example, if an individual service line material is

unknown but was installed when lead was not commonly used in the system based on interviews

with experienced system staff and plumbers, the system could consider subclassifying the service

line as “Unknown- Unlikely Lead” or a similar designation. If the system has confirmed service line

materials in a representative number of locations in a neighborhood to be lead, it could consider

subclassifying the remaining unknown service lines in the neighborhood as “Unknown- Likely

Lead” or a similar designation until its material can be investigated.

Although systems are not required to track this information or include it in their publicly

accessible inventories or submittals to the state, internally tracking this information could help

focus proactive inventory investigations and LSLR efforts. If subclassifications are made available

to the public, EPA recommends that water systems clearly communicate this information to the

public by providing easy-to-understand definitions for each subclassification and explaining how

the subclassifications were determined.

GRR Known or Unknown to have been Downstream of an LSL. EPA recommends that systems

that identify GRR service lines, as defined in Section 2.1.1, consider tracking and differentiating

these lines into subclassifications to indicate if: 1) the galvanized pipe is known to be currently

downstream of an LSL, 2) if the galvanized pipe was previously downstream of an LSL, or 3) the

system is unable to demonstrate that the galvanized service line was never downstream of an LSL.

This information could be used for many purposes, such as informing an LSLR prioritization

5

https://flintpipemap.org/map. Accessed December 8, 2021.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 2-7 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

approach or serving as an input for a predictive model. The system could also consider

subclassifying galvanized service lines that are or were downstream of a lead gooseneck, pigtail, or

connector.

Lead-lined Galvanized Pipes. EPA is aware of the existence of lead-lined galvanized service lines

but found limited information indicating their prevalence

6

. A lead-lined galvanized service line is

consistent with the definition of an LSL under the LCRR (“a portion of pipe that is made of lead,

which connects the water main to the building inlet”) (40 CFR §141.2) and must therefore be

classified in the inventory as an LSL. These lines would be subject to the same LCRR requirements

as other LSLs in the inventory, such as LSLR, public education, tap sample tiering, and risk

mitigation. Inventorying these types of lines will be more straightforward where water systems

have records of their known or likely use. Given that these pipes may appear to be non-lead on

the exterior, attempts to identify their material by visual observation or excavation may not reveal

an interior lead lining. EPA recommends that water systems consider any available information

that indicates where (if ever) lead-lined galvanized pipes were used in the system, along with

approaches such as service line sampling, to populate the inventory with these types of

connections.

Actual Material for Non-lead. The LCRR states that water systems may classify the actual material

of the service line (e.g., galvanized, plastic, or copper) as an alternative to classifying it as non-lead

(40 CFR §141.84(a)(4)(iii)). If states and systems wish to classify these lines as non-lead, EPA

encourages water systems to track the actual materials as additional information internally and/or

as part of the publicly accessible inventory. Including these classifications could improve system

asset management and better inform a statistical model, if used.

2.1.3 Recommendations for Other Drinking Water Infrastructure

EPA encourages water systems to include information on lead-containing infrastructure in their

inventories, including:

• Goosenecks, Pigtails, and Connectors: EPA encourages water systems to identify the

location and material of goosenecks and pigtails (connectors) and to include this

information in their inventories. This would allow water systems to track and manage this

potential source of lead, improve asset management, and increase transparency with

customers. This could also help water systems identify where lead connectors are or

were previously upstream of galvanized pipe and to manage this additional potential

source of lead in their system. As previously discussed, lead from an upstream source can

adsorb onto the galvanized pipe over time. The LCRR requires that when lead connectors

6

http://sedimentaryores.net/Pipe%20Scales/Fe%20scales/Galvanized_lead-lined.html. Accessed December 6, 2021.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 2-8 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

are encountered, they be removed or disconnected.

7

In addition, funding sources, such

as the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF), Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL),

and Water Infrastructure Improvements for Nations Act (WIIN), can be used to pay for

lead connector removal and replacement.

Note that systems must follow any state requirements that are more stringent than the

LCRR for these materials. For example, Michigan includes lead connectors in their

definition of an LSL (Michigan EGLE, 2018). California requires water systems to include

in their inventory lead fittings on a non-lead pipe, lead fittings on a lead pipe, and

fittings of unknown material (ASDWA, 2019).

• Lead Solder: EPA recommends that water systems track the presence of lead solder in

the service line or premise plumbing, such as after encountering information indicating

their presence in records or if seen during system inspections or maintenance. Tracking

the presence of lead solder in the service line improves system asset management and

can inform future actions for reduction of lead sources in drinking water. In addition,

knowing locations with lead solder in premise plumbing can help identify tap monitoring

locations under the Lead and Copper Rule (LCR) and LCRR.

• Fittings and Equipment Connected to the Service Line: Devices such as curb stops and

meters may be made of older brass that pre-date the effective date for the Reduction of

Lead in Drinking Water Act (January 4, 2014). These devices may not meet the revised

lowered lead-free standard

8

and could contribute to lead exposure (Sandvig et al., 2008).

EPA recommends water systems consider tracking these devices if information is

available.

2.2 Include All Service Lines Regardless of Ownership Status and Intended Use

2.2.1 Required under the LCRR

All community water systems (CWSs) and non-transient non-community water systems

(NTNCWSs) must prepare an inventory of all service lines connected to the public water

distribution system, regardless of ownership status (40 CFR §141.84(a)(2)). This means that any

service line connected to the public water system, even where the water system owns no portion

of the service line, must be included in the inventory. In those instances where ownership is split,

the inventory must include both the system-owned and customer-owned portions of the service

line. Water systems must internally track address locations of each service line and their

7

The LCRR is under revision and all rule provisions except for the initial inventory requirements may be subject to

change.

8

In 2011, Congress passed the Reduction of Lead in Drinking Water Act that amended Section 1417 of the Safe

Drinking Water Act (SDWA) and established an updated definition for “lead free” as a weighted average of not more

than 0.25 percent lead calculated across the wetted surfaces of a pipe, pipe fitting, plumbing fitting, and fixture and

not containing more than 0.2 percent lead for solder and flux.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 2-9 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

respective material classification (40 CFR §141.84(a)). Where a single service line serves multiple

units in the same building, the water system may choose to exclude unit numbers from the

address. Note that unit numbers may be required to comply with other LCRR requirements, such

as the notification requirements of 40 CFR §141.84(d) and 40 CFR §141.85(e). Because LSLs were

generally not constructed with an interior diameter over two inches, they will typically be

connected to single family homes or buildings with a limited number of units.

Note that some CWSs and NTNCWSs may not have an extensive distribution system, such as those

with a direct connection from a well to a single building. Systems must report the material from

the well to the building inlet for their inventory. EPA intends to develop a separate guidance that

is tailored to small CWSs and NTNCWSs.

Systems must include all service lines (40 CFR 141.84(a)(2)), regardless of the actual or intended

use. These include, for example, service lines with non-potable applications such as fire

suppression or those designated for emergency. These service lines could be repurposed in the

future for a potable or non-emergency use. Water systems must include in their inventory service

lines connected to vacant or abandoned buildings, even if they are unoccupied and the water

service is turned off.

2.2.2 Recommendations (Not Required under the LCRR)

Documentation that Describes System and Customer Responsibility or Ownership

As a best practice, where service line ownership or responsibility is divided between the customer

and the system, water systems may want to include with their inventory relevant information that

describes how ownership or responsibility is divided. Examples could include local ordinances or

local water utility tariff agreements or state laws or regulations. This information may be helpful

to provide to customers who have questions about how the responsibility for the service line is

divided as well as the utility’s authority to access and maintain the portion of the service line that

is located on the customer’s property.

Recommended Procedures for Service Lines of Vacant or Abandoned Buildings

Water systems could have service lines that connect to vacant or abandoned homes or buildings

that must be included in their inventory even if they are unoccupied and the water service is

Remember: States and systems may use other terms to describe ownership status

such as “public” and “private” or other terms besides “ownership” to describe the

division of responsibility between the water system and the customer. Systems

should include clear definitions in their publicly accessible inventory.

Guidance for Developing and Maintaining 2-10 August 2022

a Service Line Inventory

turned off. EPA recommends water systems have procedures in place for managing the service

lines for these structures. For example, water systems could consider:

• Prioritizing occupied homes for service material investigation or replacement to achieve a

greater lead exposure reduction from their overall program, provided that the water is

turned off at the vacant or unoccupied structure.

• Investigating these structures’ service lines if they are doing maintenance or construction

work in the area.

• Identifying service material before service is restored, or not reconnecting LSLs on

previously vacant homes or buildings (or new construction built after demolition).

• Using the transfer of property as an opportunity for service line identification or LSLR.

2.3 Location Identifiers

This section describes the LCRR requirements for providing location identifiers for LSLs and GRRs

in the publicly available inventory as well as suggested identifier information.

2.3.1 Required under the LCRR

Water systems must make a service line inventory publicly available (40 CFR §141.84(a)(8)) that

includes a location identifier for any lead or GRR service lines, such as a street address,