Visa

Economic

Empowerment

Institute

Imagining an open

future for payments

The economic empowerment

of digital remittances:

How to unlock the benets

of innovation and competition

Remittances are born of sacrice and separation. These monetary lifelines sent

back home by migrant workers are crucial for hundreds of millions of families

and for scores of countries that depend on them. This paper examines the latest

global remittance trends; describes the advantages of digital remittances and the

transparency they aord; and oers recommendations for further unlocking these

benets for migrant workers, their families, businesses, and communities.

Synopsis

Remittances are monetary lifelines sent by migrant workers

back home. They are crucial for hundreds of millions of families

and for many countries that depend on them. In this paper,

the Visa Economic Empowerment Institute (VEEI) examines

remittance trends, highlights the advantages of digital

remittances, and oers recommendations for continuing to

improve global money movement. By examining World Bank

data and performing our own remittance modeling, we nd

that digital remittances are on an excellent cost trajectory.

We nd that remittance innovation, in the form of new digital

business models paired with global network capabilities,

is achieving faster speed, better transparency, and lower

costs for people who depend on them. Further reductions

in remittance costs will require compliance and license

streamlining and—just as importantly—digital enablement

for recipient families and countries, so that remittance

ows are truly digital end to end. In this paper, we oer ve

recommendations for unlocking the benets of remittance

innovation and competition for everyone, everywhere.

©2022 Visa. All rights reserved.

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute

The economic empowerment

of digital remittances:

How to unlock the benets

of innovation and competition

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute

Imagining an open

future for payments

Acknowledgments

This study was authored by Chad Harper from the Visa Economic

Empowerment Institute and Ram Rakkappan from Visa Government

Engagement, with strong research and analytical support from Jacob Levy.

The authors thank the following colleagues for their input and review: Peter

Conti-Brown, Tierney Deggelman, Hanif Dharamsi, Brendan Fitzgibbon, Tania

Garcia-Millan, Aida Hadzibegovic, Aysen Kenar, Barbara Kotschwar, and Dan

Roesbery. The following colleagues from DevTech Systems made impactful

research contributions: Matthew Dietz, Nemanja Jovanovic, Jose Pineda,

Haykuhi Sekhposyan, Gabrielle Sinnott, and Adrienne Uselman. For their

helpful comments and contributions, we also gratefully thank Jen Swetzo for

editorial assistance and the design team from 451.

About the Visa Economic Empowerment Institute

The VEEI is a non-partisan center of excellence for research and public-private

dialogue established by Visa.

The VEEI’s overarching mission is to promote public policies that empower

individuals, small businesses, and economies. It produces research and insights

that inform long-term policy within the global payments ecosystem. Visa

established the VEEI as the next step in its ongoing work to remove barriers to

economic empowerment and to create more inclusive, equitable economic

opportunities for everyone, everywhere.

Visit: visaeconomicempowermentinstitute.org

Index

Key insights 7

Introduction 11

Remittance inows are critical—and they have been

resilient in challenging times 12

Digital remittances were key to the resilience of inows,

but we need to enable more of them 17

Costs are still high for the “average” remittance, but are much

lower for digital remittances and in cases where a migrant worker

can compare multiple options 20

In light of these insights, a few imperatives emerge 26

How we unlock the benets of remittance innovation

and competition for everyone, everywhere 29

Sources 32

Annex 1: Foreign exchange percentage for 2022 data sample 35

Annex 2: Text descriptions of gures and tables 36

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

7

Key insights

This paper examines the latest global remittance trends; describes the advantages of digital

remittances and digital enablement of migrant workers, their families, and communities; and oers

recommendations for unlocking the benets of innovation and competition for everyone, everywhere.

Below are the key insights from our research and analysis—they are discussed at greater length in the

body of the paper.

Remittance inows are critical—and they have been resilient in challenging times

Remittances proved surprisingly resilient during the pandemic. Though expected to decline in 2020,

global remittance inows actually rose, a remarkable showing in a year characterized by shutdowns

and slowdowns. Remittance inows for 2021 were very strong, reaching $773 billion globally and $605

billion for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In addition to being a critical lifeline for families,

remittances are critical to many countries. In 2021, 30 countries received over 10 percent of their GDP in

remittances, and eight countries received over 25 percent of their GDP via these ows.

Digital remittances were key to the resilience of inows, but we need to enable more of them

Border closures and business lockdowns in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic made cash-based

over-the-counter and informal systems dicult to operate. Mobile-money remittances grew almost

50 percent from 2020 to 2021, but they still account for less than 3 percent of overall remittance ows.

Money Transfer Operators (MTOs)—both the established operators with updated digital business

models and the new breed of digital-rst MTOs—saw digitally initiated remittances more than double

during the pandemic, accelerating a trend that was already in play. These newer services oer a variety

of advantages for senders and receivers, but still only a third of remittances are initiated digitally, and

only one third of those are picked up digitally. Given the cost advantages of digital remittances, our

focus needs to be on how to enable more of them.

Costs are still high for the “average” remittance, but are much lower for digital remittances

and in cases where a migrant worker can compare multiple options

Policymakers have focused on remittances for years, and these transfers have often been the most-

discussed example of the various frictions of cross-border payments. The frictions include lack of

transparency, slowness, and relatively high costs due to the complexities of regulatory compliance and,

in some cases, a lack of competitors.

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

8

As of Q2 2022, World Bank remittance price data show that:

• The average $200 remittance costs 6.01 percent—this is the headline number policymakers most

often mention.

• Cash-funded remittances cost 6.52 percent, and cash has routinely been the highest cost way of

funding a remittance.

• The digital remittances index (for remittances digitally initiated in an online or self-assisted way) is 4.80

percent.

• The SmaRT index (a measure of what a savvy consumer with access to suciently complete

information could pay) is at 3.35 percent—almost at the 3 percent UN Sustainable Development Goal

(SDG) 10 target.

These observations are conrmed by VEEI modeling of card-initiated digital remittances over the last

two years. In our modeling, we determined costs across several MTOs for 25 key global corridors and

compiled three measures: the average cost, lowest cost, and highest cost.

• The average costs for a $200 remittance across all MTOs and corridors declined from 4.24 to 3.89

percent in 2022, a drop of almost 10 percent—this is roughly analogous to the “digital remittances

index” from the World Bank.

• The average of the lowest costs declined from 2.96 to 2.08 percent in 2022, a decline of almost 30

percent—this measure is roughly analogous to the World Bank’s SmaRT index.

• By contrast, the average of the highest costs found in the corridors went up from 6.15 to 7.09 percent

in 2022, driven largely by two corridors, where MTOs were oering dramatically dierent pricing.

Migrant workers without the ability to check on multiple options could have paid exceptionally high

prices (and some undoubtedly did) during this period.

Overall, while the average price of a remittance in our research was 3.89 percent, we were able to nd a

sub-3 percent remittance in 20 of our 25 corridors in 2022.

I

n light of these insights, a few imperatives emerge

Clearly, the abilit

y to send remittances digitally and to easily compare options make a big dierence

to remittance senders and their families. So, what can the public and private sectors do to bring the

power of innovation and competition to more people?

• Traditional remittances must become digital. Cash-initiated remittances are the most expensive way

to send a remittance, and it is perhaps worse on the receiving end—many MTOs maintain vast cash

out networks in receiving countries, and this adds appreciable costs to remittances today.

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

9

• Migrant workers must be able to compare options and send remittances digitally, and their families

must be able to then spend the funds digitally at businesses in their communities. None of this can

happen without basic digital infrastructure.

• Innovation must be facilitated by more consistently applied compliance rules and by well-developed

standards, and consumer choice needs to be promoted by making it easier for remittance providers to

bring new innovations to market.

How we unlock the benets of remittance innovation and competition for everyone,

everywhere

We believe these ve steps will help unlock the benets of innovation and competition for more people

while also uplifting businesses and communities.

Begin with digital enabling infrastructure, if it does not already exist

The digital receipt and use of remittances will be a non-starter without basic enabling infrastructure. For

millions of people, basic infrastructure like electricity will be a barrier to the digitization of remittances,

payments, and commerce. Beyond electricity, internet connectivity—and increasingly broadband

connectivity—will be crucial.

Focus on digital enablement broadly, keeping both consumers and businesses in mind

While the digital receipt of remittances is critical for further progress on eciency, we must keep in mind

that the larger goal is to digitally enable everyone, everywhere, to fully participate in this new world.

Individuals need to be able to receive remittance funds digitally and then to use them digitally, with

ubiquity. This requires digitally enabling businesses, especially small businesses, helping them to accept

digital payments and to connect them to digital marketplaces. Therefore, consumers and businesses

must both be part of the equation in achieving digital ubiquity, and the countries that have driven digital

ubiquity most successfully over the last decade have worked to drive adoption on both sides.

Aim for an open, interoperable digital ecosystem built on a foundation of resilience and security

As policymakers strive to promote digital remittances, we believe that they should adopt a principle-led

and outcome-based approach, giving payment service providers and payment networks the exibility to

innovate in order to deliver against goals. Interoperability should be favored over uniformity—more paths

are better than one. A truly interoperable service should be able to reach as many endpoints as possible:

traditional bank accounts, prepaid accounts, or digital wallets.

Streamline the compliance environment to reduce cross-border frictions

While the private sector is innovating, competing, and improving speed and eciency, policymakers

have a key role to play. Remittances and other cross-border payments go through a number of regulatory

regimes that currently add frictions. But these frictions can be reduced by streamlining and aligning

compliance rules as much as possible. We therefore believe that it is critical for the public sector to address

the regulatory, supervisory, and oversight frameworks focus area of the Financial Stability Board (FSB)

cross-border roadmap.

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

10

Simplify the licensing process to allow innovation and competition to thrive

Policymakers can also help the private sector introduce innovations more quickly and with

less burden. Increased consistency of licensing requirements would help remittance service

providers enter and operate across multiple markets with less friction. Currently, with vastly

dierent license requirements around the globe that need to be navigated, companies must

spend large amounts of time and money to navigate the dierent policies and requirements,

and as Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and World Bank researchers recently noted,

this process can take years. Streamlining licensing requirements and processes will help new

market entrants bring the benets of digital remittances to more corridors, and therefore to

more people.

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

11

Introduction

Remittances

1

have been top of mind for policymakers for years, but two recent developments

have made them more topical than ever. First, there has been an increasing policy focus on

cross-border payments, and remittances are a key component; the public and private sectors

are currently mobilized to examine and address the various frictions of cross-border money

movement as part of a multiyear roadmap being managed by the Financial Stability Board

(FSB). Second, the COVID-19 pandemic reduced employment in typical remittance-sending

countries and also made traditional remittances more dicult to send, since many people in

these jurisdictions have spent more than two years living through various levels of stay-at-

home orders. Against this backdrop, remittances have been transforming toward digital for

a few years—the way commerce has transformed toward e-commerce—and this trend has

accelerated during the pandemic, even as overall economic activity and remittance volumes

have been suppressed.

The Visa Economic Empowerment Institute (VEEI) assembled a study team to examine how

innovation, technology, and the power of global networks are aecting remittance behaviors

and costs. The narrative ow of the paper is as follows:

• Remittance inows are critical—and they have been resilient in challenging times.

• Digital remittances were key to the resilience of inows, but we need to enable more of them.

• Costs are still high for the “average” remittance, but are much lower for digital remittances and in

cases where a migrant worker can compare multiple options.

• In light of these insights, a few imperatives emerge, and they include enabling more digital

remittances and streamlining the regulatory and licensing environments.

• We oer ve steps for unlocking the benets of innovation and competition for everyone,

everywhere.

For the purposes of this paper, remittances are dened as cross-border person-to-person payments

of relatively low value.

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

12

Remittance inows are

critical—and they have been

resilient in challenging times

From 1990 to 2021, there was a total of $10.9 trillion in remittances sent globally with an annual average

of $340 billion. Of this, $7.9 trillion went to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), for a yearly

average of $245 billion. Remittances remained mostly steady from 1990 to 2000 before increasing at a

greater rate in the early 2000s. As migration continued to climb, the remittances also grew.

Remittances proved surprisingly resilient during the pandemic. These critical inows were initially

expected to decline appreciably in 2020, but by the end of the year most observers expected that

inows had fallen only slightly. When KNOMAD (a global hub of knowledge and policy expertise on

migration and development issues supported by the World Bank) published nal data for 2021 in

May of 2022, the data for 2020 were also restated, and observers learned that remittances had not

fallen at all in the most severe year of the pandemic. In 2020, global remittance inows rose slightly

to $719 billion, and ows to LMICs rose to nearly $558 billion—a remarkable showing. Remittance

ows for 2021 were very strong, reaching $773 billion globally, including $605 billion for LMICs.

Further growth of about 4 percent is expected for 2022 (World Bank Group [WBG] & KNOMAD, 2022).

The next two gures depict the absolute dollar ows of remittances and the year-over-year (YoY)

growth trends from 1990 to 2021, for both the world and LMICs.

Figure 1: Remittance inows for world and LMICs, 1990-2021

Source: KNOMAD May 2022 data

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

13

Figure 2: Year-over-year changes in remittance ows to LMICs (bars) and world (lines), 1991-2021

Source: VEEI analysis of KNOMAD May 2022 data

The resilience of remittance ows during the pandemic can be attributed to several factors.

The unexpected increase of remittances was partially driven by a surge in COVID-19 cases

in LMICs; migrants (often considered essential workers in their host G20 countries) rushed

to provide nancial support to cushion the impact of the pandemic on their families. This

pattern was reinforced by the robust scal stimulus implemented by developed countries,

which are major migrant host countries. Additionally, more remittances likely shifted from

informal channels (which were not as resilient to border closures and travel restrictions) to

more formal and digital channels.

Remittances

are key to many

LMICs

The following gure depicts the LMICs receiving the largest remittance ows in 2021. The

gold points show inows for 2020. The relative positions of these countries have been fairly

steady over time; only a couple of positions in the chart would have been dierent in 2020.

Ukraine, a key receiver of remittances, occupied tenth place in 2021. Remittances to the

country are expected to rise 22 percent in 2022, so this position should be higher when

2022 inow data become available (WBG & KNOMAD, 2022).

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

14

Figure 3: Top 10 remittance receiving LMICs by absolute value (2021 in bars, 2020 in points)

Source: KNOMAD May 2022 data

Perhaps a better way to consider the importance of remittance inows is to analyze how much of

a country’s GDP is derived from them. The current global average of remittances as a percentage

of a country’s GDP is 5.6 percent. In 2021, 30 countries received more than 10 percent of their GDP

in remittances, and eight countries received more than 25 percent of their GDP via these ows. The

countries most reliant on remittance inow were Lebanon (53.8 percent of GDP), Tonga (43.9 percent

of GDP), and Tajikistan (35.5 percent of GDP). Many LMICs experienced a severe recession following the

COVID-19 pandemic, so although inows were quite resilient, the remittance-to-GDP ratio could be

higher in some places than it has been historically.

Figure 4: Top 10 remittance receiving LMICs as a % of GDP, 2021

Source: KNOMAD May 2022 data

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

15

Regional

developments

aected 2021

inows

Remittance trends in 2021 varied widely across countries and regions. Analysis of KNOMAD data shows

that LMICs accounted for just over three-fourths of global remittance inows in 2021. In this group,

South Asia contributed $157 billion (up 6.8 percent from 2020); East Asia and the Pacic contributed

$136 billion (down 2 percent); Latin America and the Caribbean contributed $133 billion (up 27

percent); Europe and Central Asia contributed $74 billion (up 8 percent); and the Middle East and

North Africa (MENA) region contributed $62 billion (up 7.6 percent).

• In South Asia, India received the greatest value of remittance inows in 2021, for a total of $82.7 billion

(up 8 percent from 2020). In Bangladesh, remittances also showed growth, increasing by 2.2 percent in

2021. By contrast, there was a 10 percent decline in remittances ows to Pakistan in 2021. The economic

turmoil in Sri Lanka also led to a considerable reduction in remittance inows, which decreased by 22.7

percent between 2020 and 2021.

• In East Asia and the Pacic, remittance inows grew 2.5 percent by the end of 2021, following a

2.4 percent decline in 2020. Defying earlier predictions of lessening ows due to the pandemic,

remittances to the Philippines increased by 4.3 percent in 2021. A key factor for this resilience was the

growth of inows from the United States. This positive growth helped to oset declines in remittances

from the Middle East and Europe, which fell by 10.6 percent and 10.8 percent, respectively, in 2020.

The decline from remittances in the Middle East reects the absence of formal safety nets available to

migrant workers in the face of the pandemic and the large repatriation of overseas Filipino workers. In

contrast with the Philippines, Indonesia’s overall remittances fell by 17.3 percent in 2020 and 1.3 percent

in 2021 due to the country’s dependency on inows from Saudi Arabia and Malaysia.

• In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), Mexico received the greatest value of remittance inows,

a total of $54.1 billion—up by a staggering 25.3 percent from 2020, largely due to the continuing

number of migrants moving to the United States. In Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and

Jamaica, 95 percent of remittances come from migrants working in the United States. The economic

situation in Spain also has a direct impact on the remittance ows to the LAC region, as the country

hosts one-tenth of all migrants from this area. Spain’s poor economic situation in 2020 had an especially

negative impact on Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia, which all saw decreased inows that year. However, the

subsequent economic growth in Spain led to sizeable increases in the remittance ows to Bolivia (24

percent), Peru (22 percent), and Colombia (24 percent) in 2021.

• Although the region was strongly aected by COVID-19, Europe and Central Asia saw inows increase

by 8 percent in 2021, for a total of $74 billion. Ukraine, the largest recipient of remittances in the region,

saw an 11.6 percent increase in 2021. In Central Asia, Uzbekistan saw a decline of 7.1 percent in 2020 and

an increase of 12.1 percent in 2021. The most remittance-dependent country in the region at present is

the Kyrgyz Republic. Remittance inows amounted to 31.3 percent of GDP in 2020 and 32.8 percent of

GDP in 2021. More than 80 percent of remittances sent to the Kyrgyz Republic come from Russia. Near-

term projections for remittances to the region are highly uncertain, owing to the war in Ukraine and the

eectiveness of the sanctions on outbound payments from Russia. However, as stated above, remittance

inows to Ukraine are expected to increase by 22 percent in 2022 (WBG & KNOMAD, 2022).

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

16

• The LMICs of the Middle East and North Africa accrued remittances totaling $61 billion during

2021, with growth registering a strong 7.6 percent. The Arab Republic of Egypt was the largest

recipient of remittances in the region (representing 51 percent of the total in 2021), garnering

$32 billion—an increase of 6.4 percent from 2020. Morocco saw a signicant increase, nearly

40 percent, in 2021. In Sub-Saharan Africa, remittance inows to Nigeria declined 27 percent

in 2020 and showed a recovery increase of 12 percent in 2021. Remittance growth was also

reported in Mozambique (67 percent), Kenya (20 percent), and Ghana (5 percent).

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

17

Digital remittances were key

to the resilience of inows,

but we need to enable more of them

The resilience in the formal recorded remittance ows may be attributed to several factors. One

was the desire on the part of cross-border workers to help their families by reducing their own

consumption, drawing on their accumulated savings, or in some cases repatriating their wealth

as their host countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, reduced the number

of migrants. As traditional sources of work in sectors disrupted by the pandemic disappeared and

incomes declined, migrants found alternative means of funding these crucial remittances. This

prevented many low-income households in LMICs—including rural, women-led, and refugee

households—from falling into poverty.

Also, countercyclical scal policies have sustained incomes and livelihoods, especially in the United

States and Europe. These two regions are among the largest originators of the remittances. Thus,

in 2020, remittance outows from the United States, Switzerland, and Germany were $68 billion,

$28 billion, and $22 billion, respectively, accounting for 22 percent of global remittances. Saudi

Arabia ($43 billion) and the United Arab Emirates ($34 billion) were also major remittance countries

undertaking stimulative measures. Such countercyclical policies softened employment and income

declines among migrant and foreign-born populations. One relevant example in this sense is the

CARES Act, implemented in the United States, hosting the largest migrant stock worldwide and

recording the largest remittance outows in 2020 (WBG & KNOMAD, 2021).

The actions of public-sector and international bodies have signicantly contributed to the continuity

of remittance ows. Often working in consultation with the private sector, governments and

regulators took measures to create a more enabling environment to keep remittances owing

and to promote the uptake of digital channels. As a rst step, many governments declared

remittance service providers (RSPs)—the businesses that provide remittance services to senders and

recipients—to be essential. International organizations, for their part, used their convening powers

to bring together dierent industry stakeholders, framing their eorts within the commitments to

existing global development goals on remittances. These goals include the UN (2015) Sustainable

Development Goal (SDG) targets to reduce remittance costs to 3 percent by 2030 and to mobilize

additional nancial resources for LMICs from dierent sources, including remittances; as well as

Objective 20 of UN Women’s (2022) Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) to

“promote faster, safer and cheaper transfer of remittances and foster nancial inclusion of migrants.”

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

18

There was an unprecedented switch to regulated and digital channels for remittances as the

pandemic changed consumer behavior and business models. Border closures and business

lockdowns in the early days of the crisis caused cash-based over-the-counter and informal systems to

struggle to operate. Under such conditions, the cost, convenience, and security attractions of digitally

enabled remittances became apparent, and the demonstrated use of these channels increased.

This, in turn, facilitated the development of linkages with other digital nancial services, building

longer term nancial resilience for remittance users. Some observers believe crypto remittances hold

much promise, but as Manuel Orozco noted this spring, crypto accounted for less than 1 percent of

remittances to Latin America in 2021, and there are a variety of barriers to migrant workers obtaining

and using crypto (Orozco et al., 2022). Migrant workers in the US have an income four times below

that of the average crypto user, for instance. Crypto notwithstanding, there is an increase in number

of cross-border transactions for mobile-based payment channels. According to the GSM Association,

$15.9 billion in remittances were processed through mobile money in 2021, representing strong

yearly growth of 48 percent (Awanis et al., 2022). But mobile money remittances still make up less

than 3 percent of overall remittance ows. Migrant workers around the globe are also shifting toward

digital remittance services because they help reduce the money transfer time and remittance costs.

Moreover, digital remittance services oer high privacy and protection for consumers’ money. The

surge in formal transfers is validated, among other evidence, by the rising volume of transactions

through digital money transfer operators (MTOs) (Balch, 2020). However, digitally initiated

remittances still represent just one third of all remittances.

The next gure depicts a six-year quarterly view of remittance initiation trends derived from a

DevTech/VEEI analysis of the data in the World Bank’s (2022) Remittance Prices Worldwide database,

which includes information on a few hundred global corridors. More than 100,000 records were

analyzed and categorized. Remittances not initiated through payment cards (debit or credit)

or mobile money payment instruments were treated as traditionally initiated. It is possible this

methodology misses some online remittances, but the other payment methods have long been

used in physical locations, so the team chose to use a conservative view. Of the remittances initiated

with payment cards or mobile money, a further distinction was made in how the remittance was

picked up. If a remittance was digitally initiated but picked up in some traditional way such as cash, it

is considered “digitally initiated” in the gure. If a remittance was digitally initiated and transmitted to

a card, mobile money account, or bank account, it was considered “digital end-to-end.”

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

19

Figure 5: Digital remittance trends over 25 quarters, 2016-2022

Source: VEEI/Devtech Systems analysis of WBG Remittance Prices Worldwide Quarterly data

The gure shows a marked shift toward digital initiation overall (which includes both blue

categories), and a very important shift in digital end-to-end remittances. The gure further shows

this shift accelerated greatly in early 2021. However, many observers noted the change in early

2020 as lockdowns proceeded, so it was likely taking place for some corridors earlier and became

widespread in the sampled corridors a few quarters later. Since mid-2018, digitally initiated

remittances have tripled, rising from 10 percent of remittances to 34 percent. Digital end-to-end

remittances more than quadrupled during this period (from 3 to 13 percent), but much of this

progress was quite recent: Fully digital remittances more than doubled, growing from 6 to 13

percent between Q1 of 2021 and Q1 of 2022. We will discuss the importance of these end-to-end

digital remittances later in this paper.

Still, the majority of remittances involves cash being used at RSPs, where migrant workers can rely

on the mediating support of agents. Thus, during COVID-19 related lockdowns, resilient remittance

ows also depended on the accessibility of RSPs that were declared “essential” services (Remittance

Community Task Force, 2020).

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

20

Costs are still high for the “average”

remittance, but are much lower for digital

remittances and in cases where a migrant

worker can compare multiple options

In 2015, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), seeking to reduce inequality among

countries, set forth a 3 percent remittance cost target (for a $200 remittance) to be achieved by 2030.

More recently, remittances have become an important part of the cross-border payments roadmap

being managed by the FSB (2020) with signicant support from the Committee on Payments and

Market Infrastructures (CPMI), International Monetary Fund (IMF), WBG, and others. In October of

2021, the FSB rearmed the remittance cost target of 3 percent, and new targets for speed, access,

and transparency were added.

Some key players in cross-border payments and remittances

FSB: Entity that promotes international nancial stability by coordinating nancial authorities and international standard-setting

bodies; responsible for the cross-border roadmap.

CPMI: Committee of nearly 30 central banks / jurisdictions that coordinates international eorts on payments policy and standards;

a major player in the cross-border roadmap.

World Bank: An international nancial institution that provides assistance to the governments of LMICs for the purpose of pursuing capital

projects; the World Bank is the major source of data on remittance prices and (through KNOMAD) on remittance ow trends.

KNOMAD: The Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development is a brain trust for the global migration community. It is an

open, inclusive, multidisciplinary knowledge partnership that draws on experts to create and synthesize knowledge for use by

policymakers in sending, receiving, and transit countries. The secretariat is housed in the World Bank.

IMF: An international organization of almost 200 countries that works to foster global monetary cooperation, secure nancial

stability, and reduce poverty around the world.

Cost

measurements

include transfer

charges and

foreign exchange

margins

When the UN (or another organization) sets a cost target of 3 percent, the total consumer cost of

the remittance is envisioned. The cost of remittances is calculated as the simple average total cost

for sending $200 or $500 (and their equivalents) through RSPs, as captured by the World Bank

(2022) Remittance Prices Worldwide database. The total cost charged by a provider includes the

remittance transfer fee and, importantly, the foreign exchange rate applied by the RSP. The World

Bank tracks costs in a variety of ways.

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

21

World Bank

quarterly reports

and data show

positive cost

trends

Although these gures have not fallen as much as the public and private sectors would like,

there have been benecial cost trends even over the last few years, and some of these results

are attributable to the rise of digital remittances. The gure below depicts trends over the past

11 quarters for three key measures of remittance costs.

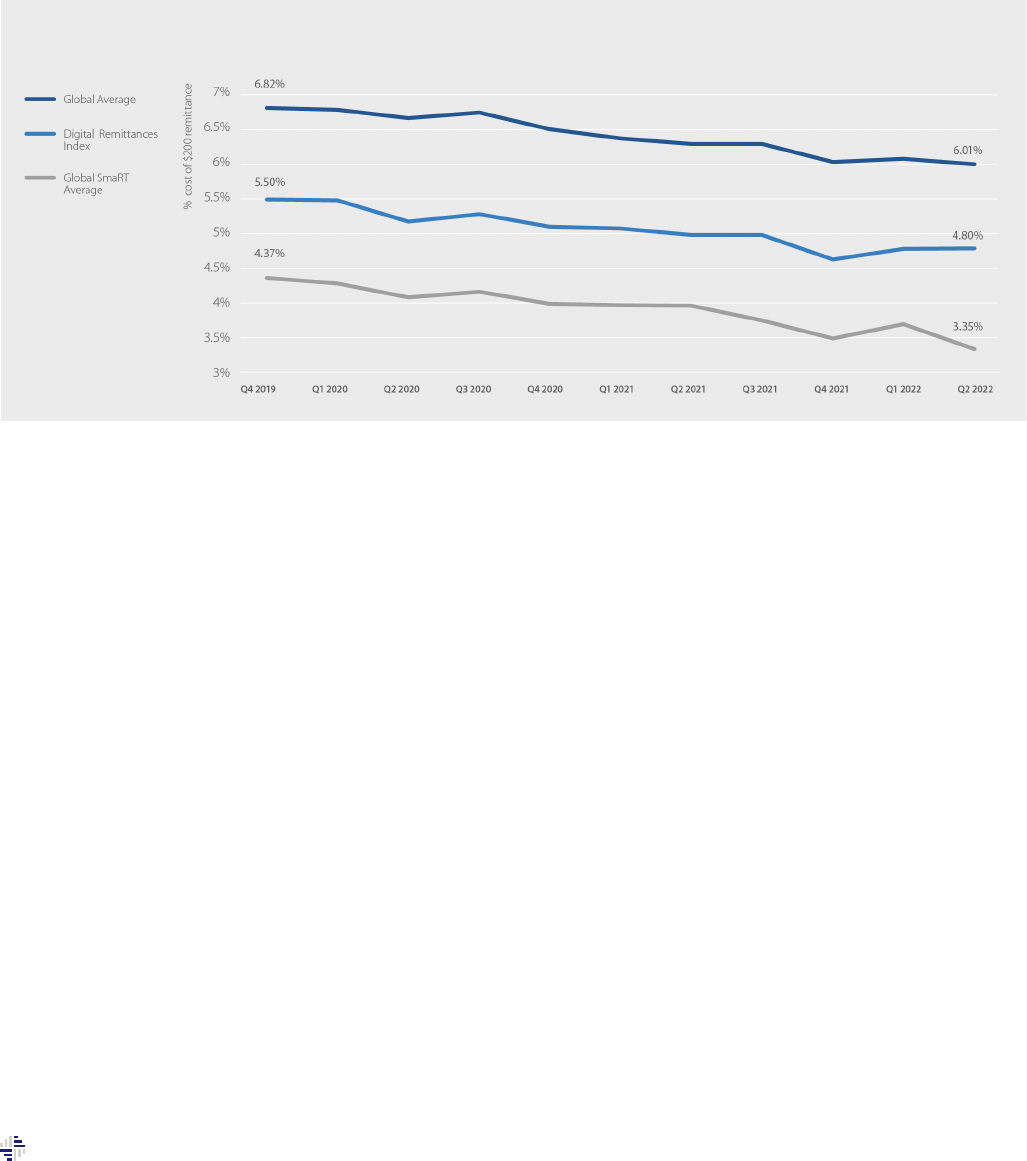

Figure 6: Remittance cost trends; $200 remittance, Q4 2019 - Q2 2022

Source: WBG Remittance Prices Worldwide Quarterly reports

The trends across three key measures (despite a slight uptick in early 2022) are all good:

• At the time the FSB roadmap stages were kicking o in late 2019, the average cost of sending a $200 remittance

was 6.82 percent; this has fallen to 6.01 percent, a decline of more than 10 percent over the 11 quarters.

• A relatively new measure (the digital remittances index) was introduced to track the cost of remittances

that are digitally initiated in an online or self-assisted way. Costs for this index fell from 5.5 to 4.8 over 11

quarters, about a 12 percent decline.

• The Global SmaRT Average reects what a savvy consumer could pay to transfer remittances in each corridor.

The three lowest costs for each corridor in the World Bank’s quarterly sample are averaged to produce the

number. It is clear that access to information really helps obtain a lower cost. Over the past 11 quarters, costs

have dropped from 4.37 percent to 3.35 percent for this index, a decline of around 23 percent.

An analysis of the past 11 Remittance Prices Worldwide quarterly reports reveals a couple of other key trends.

Cash and bank accounts are almost always the highest cost methods for sending a remittance. Mobile money

and payment cards are the lowest cost ways of sending remittances, and mobile money is often the very

lowest cost. In 10 of the last 11 quarterly reports, mobile money was found to be the least expensive means of

sending remittances, with cards dipping below mobile money in the rst quarter of 2021. With these trends in

mind, VEEI wanted to take a deeper dive into (1) card-initiated remittances (which are likely to take advantage

of newer money movement innovations) and (2) the value of being able to shop around for the best price.

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

22

VEEI cost modeling

conrms the

value of digital

remittances and

the ability to

compare options

In concert with other MTO innovations, digital remittances can oer faster and more ecient transfers

because they take advantage of new money movement networks, avoiding correspondent banking

movement in many instances. Correspondent banking has been critical to global money movement for

decades, but this money movement method inherently involves more touches by more players, which

will always increase costs. In fact, simply maintaining the “nostro and vostro” accounts needed to move

money through the correspondent system can be quite costly for the banks involved. Correspondent

banking is also facing a variety of challenges, notably a broad-based retreat in the number of its cross-

border relationships (Rice et al., 2020). As we noted in The rise of digital remittances, several newer global

money movement capabilities have been developed and rolled out in recent years (Harper, 2021). These

models typically involve a central network that is “always on” and that avoids multiple hand-os. These

services are faster, often completing cross-border transactions in minutes, and they provide greater visibility

and certainty for both the sender and the receiver. In these newer money movement methods, a network

solves for the complexity of interacting with multiple payment systems, settlement, and foreign exchange.

(See Box 1 for a real-world example of one of these next-generation networks, which is powering millions

of digital remittances today.)

We used publicly

available tools to

model costs

To further evaluate digital remittance cost trends, we examined digital remittance costs in 28 corridors

in February 2021. The study team was particularly interested in the costs of digital remittances powered

by the new global money movement networks, and debit and/or credit cards are used to initiate more

of these transfers. In other words, debit card- and credit card-initiated remittances were used as a proxy

for digital remittances using the new global networks. The corridors were chosen to represent a good

number of the top receiving countries—both the ones that receive the most in value and the ones that

receive a high percentage of their GDP in remittances. We repeated the exercise in February 2022.

A very positive aspect of digital remittances is that consumers can shop around if they have digital

tools. Of the ve MTOs we looked into, four allowed modeling of a remittance via their website or app.

A user is able to select a corridor, payment method, and pickup method and see the costs, broken into

transfer fees and foreign exchange margins. We used this modeling capability to examine costs for $200

and $500 remittances (or the sending country’s equivalent) for the corridors in February 2021 and 2022.

This analysis obviously is not comprehensive—we wanted to examine the impact on costs of digital

remittances using the newer global networks. Data were gathered for a couple of established MTOs

that oer a digital remittance product and for a few of the new digital-rst MTOs. Due to some remote

browsing restrictions imposed by one country in our 2021 sample, we have 25 corridors in the two-year

data collection. The full matrix of corridors and costs is included in the following table. The table depicts

the average costs for all MTOs in the corridors, the lowest costs, and the highest costs. These costs are

inclusive of fees and foreign exchange costs. See Annex 1 for more detail on the FX portion of the 2022

average costs depicted in the table.

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

23

BOX 1:

Visa Direct and

global money

movement

Visa Direct is a payments network partnering up with nancial institutions, ntechs, processors,

remitters, governments, and merchants to oer real-time* person-to-person (P2P), business-

to-small business (B2b), business-to-consumer (B2C), and government-to-consumer (G2C)

payments and funds disbursements. Visa Direct can reach 7 billion cards, accounts, and digital

wallets across 190 countries to help our clients transform global money movement.

Visa Direct reaches endpoints by providing access to 16 card-based networks, 65 domestic ACH

schemes, 11 RTP schemes, 5 payment gateways, and access to one of the world’s largest cross

border ACH networks.

* Actual funds availability depends on receiving nancial institution and region.

Visa Direct Network for Cross Border

Visa Direct is a leading global network to help transform global money movement

Visa Direct already partners with the top 5 remittances businesses, with some of them reporting the

following trends during their 2Q 2022 earnings calls:

• MoneyGram reported 36 percent year-over-year growth in digital transactions, with 44 percent of

all money transfer transactions being digital in Q2.

• Remitly, a digital-rst MTO, reported a 43 percent rise in active customers and a 90 percent

increase in engagement via mobile device.

• Intermex reported a 106.6 percent increase in digital transactions from the previous quarter.

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

24

Table 1: VEEI / DevTech corridor analysis of $200 and $500 remittances, 2021-2022

CORRIDOR

$200 REMITTANCES $500 REMITTANCES

AVERAGE

CUSTOMER COST %

LOWEST

CUSTOMER COST %

HIGHEST

CUSTOMER COST %

AVERAGE

CUSTOMER COST %

LOWEST

CUSTOMER COST %

HIGHEST

CUSTOMER COST %

2021 2022 2021 2022 2021 2022 2021 2022 2021 2022 2021 2022

Australia-Vietnam 3.09 3.39 1.95 1.45 6.04 5.27 2.19 2.68 1.26 0.94 4.97 4.49

Canada-Vietnam 4.29 4.34 2.00 2.21 7.45 7.56 3.72 4.03 2.00 1.75 7.27 7.65

France-Algeria 10.94 4.98 10.94 2.49 10.94 9.95 8.97 3.47 8.97 1.17 8.97 8.05

Germany-Vietnam 4.44 3.81 2.48 0.71 10.63 10.33 3.24 2.82 1.66 0.71 9.25 8.40

Gr

eece-Albania 2.72 2.05 0.65 0.64 3.40 2.40 1.88 1.09 0.50 0.50 2.34 1.41

Italy-Albania 2.56 2.52 0.65 0.64 3.49 4.84 1.81 1.78 0.50 0.50 2.69 3.53

Italy-Nigeria 2.70 1.20 2.46 0.00 3.17 2.66 2.43 0.71 2.38 0.00 2.46 1.55

Kuwait-India 1.96 1.74 1.73 1.74 2.19 1.74 0.98 0.77 0.76 0.77 1.21 0.77

New Zealand-Samoa 8.15 5.75 8.15 4.44 8.15 7.28 6.87 5.08 6.87 3.66 6.87 6.54

Russia-Kyrgyzstan 0.52 3.05 0.03 3.05 1.96 3.05 0.51 3.16 0.02 3.16 1.96 3.16

Russia-Moldova 1.82 2.78 0.03 2.74 7.20 2.90 1.81 2.08 0.02 1.77 7.20 3.01

Russia-Tajikistan 5.99 2.90 5.99 2.90 5.99 2.90 5.99 3.01 5.99 3.01 5.99 3.01

UAE-Egypt 3.70 4.34 2.54 3.74 5.94 5.71 3.94 4.71 3.48 4.51 4.77 4.85

UAE-India 2.37 3.33 0.37 2.54 4.49 5.07 3.24 3.82 2.51 3.52 4.01 4.59

UAE-Pakistan 3.41 3.46 2.54 2.64 4.97 5.25 3.83 3.92 3.48 3.62 4.35 4.68

UAE-P

hilippines 3.04 3.20 2.21 2.17 4.66 5.20 3.47 3.66 3.14 3.15 4.08 4.64

UK-Kenya 4.62 3.54 2.89 1.57 9.92 9.62 3.97 3.27 2.10 1.37 9.13 8.86

UK-Nigeria 1.79 1.68 1.13 0.00 2.13 4.98 1.67 0.95 0.75 0.00 2.13 3.08

USA-Dominican Republic 7.06 7.94 4.29 4.04 9.06 18.70 6.29 6.88 2.87 2.01 8.88 15.30

USA-El Salvador 4.70 4.31 2.91 0.99 6.10 8.26 3.01 2.81 1.19 0.40 4.40 4.85

USA-Guatemala 4.43 3.78 2.13 0.29 9.97 8.79 3.56 2.87 1.49 0.29 8.44 7.12

USA-Haiti 5.27 6.11 4.90 4.47 5.66 10.97 3.22 4.06 2.15 2.15 4.06 8.55

USA-Honduras 5.33 5.19 3.93 1.72 6.59 9.15 3.63 3.72 2.24 1.13 4.82 5.75

USA-Jamaica 6.42 7.54 4.46 2.57 7.85 17.22 6.16 5.87 3.57 2.74 8.38 12.81

USA-Mexico 4.60 4.30 2.62 2.17 5.84 7.53 3.67 2.71 1.56 0.29 5.31 5.53

AVERAGES

4.24 3.89 2.96 2.08 6.15 7.09 3.60 3.20 2.46 1.72 5.36 5.69

CORRIDORS UNDER 3%

8 7 18 20 3 5

Source: VEEI / DevTech Systems analysis

Although the average costs across all MTOs and corridors were over the 3 percent target, a consumer

able to shop around would have been able to send a remittance at below a 3 percent cost in 20 of the

25 corridors (80 percent of them) in 2022—an improvement over 2021.

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

25

The average costs

declined, but the

real story is the

power of shopping

for the best option

As detailed in the following box plots, costs declined from 2021 to 2022 for two measures,

and they increased for one.

Figure 7: Averages of overall costs, lowest costs, and highest costs for sending a $200 remittance, 2021-2022

Source: VEEI / DevTech Systems analysis

The average costs across all MTOs and corridors declined from 4.24 to 3.89 percent in 2022, a decline of

almost 10 percent. Looking at the second pair of box plots oers a more compelling insight. Here, we show

the lowest cost oered by any of the MTOs for the corridors. The average of the lowest costs declined from

2.96 to 2.08 percent in 2022, a decline of almost 30 percent. Highlighting the benets of being able to shop

around, the average of the highest costs found in the corridors actually went up from 6.15 to 7.09 percent.

This was driven largely by two corridors: the US to the Dominican Republic (where the lowest cost was 4.04

percent and highest was 18.70 percent) and the US to Jamaica (where the lowest cost was 2.57 percent,

but the highest was 17.22 percent). MTOs were oering dramatically dierent pricing for some corridors

when we looked at costs in early 2022—migrant workers without the ability to check on multiple options

could have paid very high prices during this period (and some undoubtedly did).

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

26

In light of these insights,

a few imperatives emerge

Traditional

remittances must

become digital to

continue lowering

costs

Cash is already known as the most costly way to initiate a remittance. Another huge cost barrier is that digital

remittances are still typically received in cash. According to our conversations with MTOs (and numerous public

statements by the rms), the majority of digitally initiated remittances are still ultimately picked up in cash. In Figure

5 we showed that 34 percent of remittances were digitally initiated in Q2 of 2022, but only a third of those were

digital end-to-end. To make further progress on costs, we need the number of digitally initiated remittances to grow

much higher, and we need the proportion of digitally “picked up” remittances to grow as well. Aside from the many

advantages of digital pickup (which include physical safety for women, who still receive the majority of remittances),

there is a notable cost issue for remittances that become “physical” at the end of the process by being cashed out.

Traditional MTOs maintain vast networks for this cash-out capability, and digital-rst MTOs have likewise engaged

numerous third parties to facilitate transfers on the receiving end as conversion to cash. There are usually

some banks and many retail partners set up to facilitate these cash pickups, and these arrangements are quite

expensive. Based on discussions with MTOs, we believe these arrangements add 100-300 basis points of expense

to remittances picked up in cash. These costs are assumed in the business model of many of the new remittance

providers, and they do not take into account the time and eort the remittance receiver must spend on the cash

collection. Our evaluation of digital remittance costs revealed that there was usually no dierence in the “cost to

remittance sender,” according to the disbursement (pickup) method; these costs are often built into the overall

pricing. Because of the high costs associated with cash disbursement, and because the majority of remittances

are still picked up in cash, it stands to reason that further reductions in overall remittance costs will require digital

receipt, and this requires the digital enablement of people in the receiving countries.

Migrant workers

must be able

to compare

options and

send remittances

digitally, and their

families must be

able to then spend

the funds digitally

at businesses in

their communities

We have already seen the power of digital in delivering better transparency of options and lower costs. But

what types of eorts are needed to enable receiving families to actually use funds digitally? A recent example

is worth highlighting. Mobile money, as mentioned before, is a traditionally low-cost way of sending funds

digitally. But mobile money is not accepted at many merchant and e-commerce locations, so mobile money

users would need to cash out to make purchases in their everyday lives. The private sector is innovating and

forging key partnerships to resolve these challenges, however. As an example, in June 2022 Safaricom and Visa

introduced a new virtual card, called M-PESA GlobalPay, that enables more than 30 million customers in Kenya

to shop using their mobile money account at more than 100 million merchants across 200 countries through

Visa’s global network. This capability will open e-commerce opportunities for M-PESA customers and make it

easier for Kenyans traveling abroad. More detail is provided in Box 2. This is the type of partnership that will enable

remittances to stay digital from end-to-end, providing many advantages, including lower costs.

The costs associated with cash pickup are unlikely to disappear until a strong majority of remittances are digital

end-to-end. Partnerships like this—repeated many times—should be encouraged.

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

27

Innovation must

be facilitated by

more consistently

applied

compliance

rules and by

well-developed

standards, and

competition needs

to be promoted by

making it easier

for remittance

providers to bring

new innovations to

market

Regulatory complexities remain a challenge in cross-border payments generally, and for remittances

specically. The MTOs we have spoken with have mentioned that know your customer (KYC) requirements,

suspicious activity report (SAR) thresholds, oce of foreign asset control (OFAC) screening, and anti-money

laundering (AML) requirements are topics worthy of policymaker attention. And it appears this attention is

being given. In the FSB’s 2020 cross-border payments roadmap, Focus Area B is devoted to “coordinating on

regulatory, supervisory, and oversight frameworks.” There are currently ve workstreams in this focus area,

covering initiatives such as aligning regulatory frameworks for cross-border payments, applying AML and

counterterrorism nancing rules consistently, and fostering KYC and identity sharing. It is critical that the

public sector make progress in these areas, and on standards.

Standards are perhaps the unsung heroes in the history of payments. Global standards form the backbone

of the global payment system, enabling ubiquity by creating a common set of protocols and specications

that payment service providers can adopt anywhere in the world while still preserving the ability to foster

innovation. Further, global standards enable closed-loop payment systems to become open-loop systems

and remove signicant technical barriers, making it easier for new providers of payment services to connect to

the broader payment system. But standards need to be able to support rapid change, allowing innovation to

happen within the standards rather than outside of them.

Another key area requiring public-sector coordination is the licensing of new products and services. If

policymakers desire to have more players and competition in remittance corridors, then streamlining licensing

will be a key way to achieve that goal. A June joint paper from the BIS and World Bank highlighted several

licensing-related issues and noted:

Licensing processes in both send and receive countries can take between 90 days to two years to obtain

authorisation to commence operations. Documentation requirements can discourage new entrants from

submitting applications to authorities. Limited competition can result in higher remittance costs and poor

quality of service. In some markets, it can also push consumers to use unregulated channels, undermining the

integrity of the system (Ardic et al., 2022).

Making licensing easier will allow more options to come to market faster, and we have already seen how costs

are lower when there are multiple options for a corridor, and when people know about the options.

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

28

BOX 2:

M-PESA

GlobalPay Visa

Virtual Card

Why Safaricom and Visa partnered

Enabling Global Payments: The partnership will enable M-PESA customers to

make payments for subscriptions, shopping, e-learning, and entertainment from

Visa Merchants in over 200 countries. The partnership will provide access to cards

for more than 30 million M-PESA customers in Kenya, making access to cards

easy for a lot of consumers who are not able to access traditional bank issued

debit and credit cards. M-PESA users can enable the GlobalPay Visa virtual card

directly from the M-PESA wallet app. Users click “activate” and then select their

desired design for the virtual card.

Other key benets of M-PESA GlobalPay

Safe and secure payment for consumers, with increased security using

a combination of Dynamic CVV and M-PESA PIN for all transactions. The

consumer has also been empowered to disable or suspend the cards.

Convenience and transparency: Additional tools like the cost estimator

and budget control have been included to provide the consumer with

transparent cost and spend control.

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

29

How we unlock the benets

of remittance innovation

and competition for

everyone, everywhere

To continue the encouraging path that digital remittances are on, policymakers must focus on removing

more barriers. When it comes to enhancing payment systems and developing new cross-border

capabilities, the private sector is making signicant progress on fast and ecient global money movement.

Based on our research and analysis, the VEEI study team believes that public-sector resources would be best

allocated to the digital enablement of people and to further enabling the private sector to innovate. These

ve steps are a good place for policymakers to start:

Begin with

digital enabling

infrastructure,

if it does not

already exist

For millions of people, basic infrastructure like electricity will be a barrier to the digitization of remittances,

payments, and commerce. Beyond electricity, internet connectivity—and increasingly broadband

connectivity—will be crucial. And given that mobile phone adoption outstrips computer penetration in

many parts of the world, mobile broadband is perhaps the best answer for connectivity moving forward.

Countries with policymakers who prioritize digital infrastructure will have an advantage in this new

era. Aside from making digital remittances possible, these capabilities enable e-commerce and digital

marketplaces for small businesses, and they enable telework for many types of employees, which has

proven important during the pandemic.

Focus on digital

enablement

broadly, keeping

both consumers

and businesses

in mind

Although the digital receipt of remittances is critical for further progress on costs, we must keep in mind

that the larger goal is to digitally enable everyone, everywhere, to fully and meaningfully participate in an

increasingly digital world. Individuals need to be able to receive remittance funds digitally and then to use

them digitally, with ubiquity. This requires digitally enabling businesses, especially small businesses, helping

them accept digital payments and to connect them to digital marketplaces. Consumers and businesses

must both be part of the equation in achieving digital ubiquity, and the countries that have driven digital

ubiquity most successfully over the last decade have worked to drive adoption on both sides. Digital ID

will play a key role in digital enablement and will likewise require a dual focus: Adoption by people on one

side, and public institutions and businesses on the other, are key to overall adoption. Digital skills, for both

consumers and small businesses, will need to be part of this focus.

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

30

Aim for an open,

interoperable

digital ecosystem

built on

resilience and

security

As policymakers strive to promote digital remittances (and digital payments), we believe that they

should adopt a principles-led and outcome-based approach, giving payment service providers and

payment networks the exibility to innovate in order to deliver against goals. Interoperability should be

favored over uniformity—more paths are better than one. Given the favorable cost trajectories of digital

remittances originated using mobile money and debit/credit instruments, which have been obtained by

innovative MTOs working with new global network capabilities, we do not believe that the public sector

needs to build new global infrastructure that could stie competition. Open competition combined

with the use of open and global technical standards drives payment innovation. A truly interoperable

service should be able to reach as many end points as possible: traditional bank accounts, prepaid

accounts, and digital wallets. Building consumer trust in the digital economy requires developing

systems, products, and services that are secure—that protect consumers’ data, money, and identity.

Only with those safeguards can consumers and businesses interact with condence. Adopting digital

security systems enables real-time vetting of fraudulent transfers, with tokens and articial intelligence

increasing the security of remittances. Alleviating fraud risk requires signicant investment in areas such

as authentication methods, behavioral biometrics, and aggregation tracking.

Streamline the

compliance

environment to

reduce cross-

border frictions

While the private sector is innovating, competing, and improving speed and eciency, policymakers

have a key role to play. Remittances and other cross-border payments go through a number of

regulatory regimes that currently add frictions. But these frictions can be reduced by streamlining and

aligning compliance rules as much as possible. This includes the development of a consistent AML

compliance framework that would improve the eciency and transparency of cross-border solutions

oered by the private sector. We therefore believe that it is critical for the public sector to address the

“regulatory, supervisory, and oversight frameworks” focus area of the FSB (2020) cross-border roadmap.

Though global coordination will no doubt be challenging, we believe progress in this focus area would

oer the greatest return on the time invested.

Simplify the

licensing

process to allow

innovation and

competition to

thrive

Policymakers can also help the private sector introduce innovations more quickly and with less burden.

The “passporting of licenses,” a suggestion from the World Economic Forum in its June 2020 paper on

cross-border payments, was not directly mentioned in the FSB’s cross-border roadmap. Even increased

consistency of licensing requirements would help remittance service providers to enter and operate

across multiple markets with less friction. We believe that the private sector should prioritize creating

products that oer better customer experiences and enable more ecient transfers of money. But

the public sector can help by reducing the barriers to market entry. Currently, with vastly dierent

license requirements around the globe that need to be navigated, companies must spend large

amounts of time and money to navigate the dierent policies and requirements, and as BIS and World

Bank researchers recently noted, this process can take years (Ardic et al., 2022). Streamlining licensing

requirements and processes will help new market entrants bring the benets of digital remittances to

more corridors, and therefore to more people.

At the Visa Economic Empowerment Institute, we will continue to explore and analyze developments

in global money movement and remittances. We hope this paper’s insights and recommendations are

useful to policymakers and private sector partners, and we welcome continued engagement with all

stakeholders on how digital innovation can be a ywheel for upward mobility in the global economy.

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

32

Sources

Ardic, O., Baijal, H., Baudino, P., Boakye-Adjei, N.

Y., Fishman, J., & Maikai, R. A. (2022, June). The

journey so far: making cross-border remittances

work for nancial inclusion (FSI Insights on policy

implementation No. 43). World Bank Group & Bank

for International Settlements.

https://www.bis.org/fsi/publ/insights43.pdf

Awanis, A., Lowe, C., Andersson-Manjang, S. K., &

Lindsey, D. (2022). State of the Industry Report on

Mobile Money. GSM Association.

https://www.gsma.com/sotir/wp-content/

uploads/2022/03/GSMA_State_of_the_

Industry_2022_English.pdf

Balch, O. (2020, May 10). Are digital payments COVID

winners? Raconteur.

https://www.raconteur.net/nance/payments/

digital-payments-covid-19/

Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems,

& World Bank. (2007, January). General principles for

international remittance services.

http://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d76.pdf

Financial Stability Board. (2020, October). Enhancing

Cross-border Payments – Stage 3 roadmap.

https://www.fsb.org/2020/10/enhancing-cross-

border-payments-stage-3-roadmap/

(2021, October 13). Targets for Addressing the Four

Challenges of Cross-Border Payments.

https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P131021-

2.pdf

(2022, July 6). Developing the Implementation

Approach for the Cross-Border Payments Targets.

https://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/P060722.pdf

Harper, C. (2021). The rise of digital remittances: How

innovation is improving global money movement. Visa

Economic Empowerment Institute.

https://usa.visa.com/content/dam/VCOM/global/ms/

documents/veei-the-rise-of-digital-remittances.pdf

KNOMAD. (2022). Remittances Data [Data set].

https://www.knomad.org/data/remittances

Migration Data Portal. (2021, February 5).

International migrant shocks.

https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/

international-migrant-stocks#key-trends-2000-2020

Orozco, M., Yansura, J., Porras, L., Bosworth, J., &

Schmitz, K. (2022, May 3). Will Cryptoassets Disrupt

Remittances in Latin America? The Dialogue.

https://www.thedialogue.org/analysis/will-

cryptoassets-disrupt-remittances-in-latin-america/

Remittance Community Task Force. (2020,

November). Remittances in crisis: Response, Recovery,

Resilience.

https://143163-1013359-1-raikfcquaxqncofqfm.

stackpathdns.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/

Blueprint-for-Action_FINAL.pdf

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

33

Rice, T., von Peter, G., & Boar, C. (2020, March). On the

global retreat of correspondent banks. BIS Quarterly

Review.

https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2003g.htm

United Nations. (2015, September). Sustainable

Development Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities.

https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/

inequality/

UN Women. (2022). GCM Objective 20: Promote faster,

safer and cheaper transfer of remittances and foster

nancial inclusion of migrants.

https://ppguide.unwomen.org/objective/20

World Bank. (2022, July 13). Remittance Prices

Worldwide [Data set].

https://remittanceprices.worldbank.org/

World Bank Group (WBG). (2020, December).

Remittance Prices Worldwide Quarterly. Issue 36.

https://remittanceprices.worldbank.org/sites/default/

les/rpw_main_report_and_annex_q42020.pdf

World Bank Group (WBG) & KNOMAD. (2020, April).

COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens (Migration

and Development Brief No. 32).

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/

handle/10986/33634/COVID-19-Crisis-Through-a-

Migration-Lens.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y

(2021, November). Recovery: COVID-19

Crisis Through a Migration Lens (Migration and

Development Brief No. 35).

https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/les/2021-11/

Migration_Brief%2035_1.pdf

(2022, May). A war in a pandemic: Implications of

the Ukraine crisis and COVID-19 on global governance

of migration and remittance ows (Migration and

Development Brief No. 36).

https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/les/2022-05/

Migration%20and%20Development%20Brief%20

36_May%202022_0.pdf

World Economic Forum (WEF). (2020,

June). Connecting Digital Economies: Policy

Recommendations for Cross-Border Payments.

https://www.weforum.org/reports/connecting-

digital-economies-policy-recommendations-for-

cross-border-payments

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

35

Annex 1: Foreign exchange

percentage for 2022 data sample

When a cost target of 3 percent is mentioned, the total consumer cost of the remittance is envisioned.

The cost of remittances is calculated as the simple average total cost for sending $200 or $500 (and their

equivalents) through remittance service providers, as captured by the World Bank Remittances Prices

Worldwide database. The total cost charged by a provider includes the remittance transfer fee and,

importantly, the foreign exchange rate applied by the remittance service provider.

Table 1 depicts the full matrix of corridors and costs for 2021 and 2022 data collection. The table depicts the

average of costs for all MTOs in the corridors, the lowest costs, and highest costs. These costs are inclusive of

fees and foreign exchange costs.

Figure 8 below oers more detail on foreign exchange margins for the 2022 average cost columns of the

table. For example, if a given remittance corridor had an average cost of ve percent, and the average FX fee

below is 3 percent, then the remaining 2 percent was the remittance transfer fee.

Figure 8: Average exchange rate margin in 25 corridors; debit/credit payment, for $200 and $500 remittances

Source: VEEI / DevTech Systems analysis

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

36

Annex 2: Text descriptions

of gures and tables

Figure 1: Remittance inows for world and LMICs, 1990-2021

This line plot tracks the value of remittance inows between 1990 and 2021, with one line representing

world inows and another representing inows to LMICs. In 1990, both values stood well below $100

billion, growing slowly but steadily through 2000—aside from a minor downturn in 1996. From 2000

through 2021, the rate of growth increased signicantly. By 2021, inows to LMICs surpassed $600 billion

and world inows reached nearly $800 billion. The only downturns during this period took place in 2009

and 2016, with inows increasing only slightly between 2019 and 2020 and taking o again in 2021.

Figure 2: Year-over-year changes in remittance ows to LMICs (bars) and globally (lines), 1991-2021

This plot tracks the year-over-year percentage change in remittance inows to LMICs (represented as bars)

and globally (represented as lines). During most years, remittance inows increased—typically between 5

and 20 percent. The two largest increases took place in 1997 and 2005. In 1997, inows in both corridors

increased by approximately 40 percent, with global inows slightly outpacing LMICs. In 2005, global inows

increased by approximately 30 percent, while inows to LMICs increased by approximately 40 percent. In

1996, 2009, and 2016, inows in both corridors decreased, with the sharpest downturns taking place in

1996. In 1998, inows to LMICs decreased slightly, while global inows continued to increase.

Figure 3: Top 10 remittance receiving LMICs by raw value (2021 in bars, 2020 in points)

This plot displays the top 10 remittance receiving LMICs by raw value of inows during the years 2021

(represented as bars) and 2020 (represented as points). The countries are ordered by 2021 value. The top

recipient was India, which received over $75 billion in remittances during 2021. The next two countries—

Mexico and China—each received approximately $50 billion. The following three countries—Philippines,

Egypt, and Pakistan—each received between $25 and $50 billion. The following country—Bangladesh—

received just shy of $25 billion and the nal three—Nigeria, Vietnam, and Ukraine—each received close to

$20 billion. The rankings were similar in 2020, with China taking the number two spot over Mexico.

Figure 4: Top 10 remittance receiving LMICs as a % of GDP, 2021

This bar plot displays the top 10 remittance-receiving LMICs by percent of GDP in 2021. The top recipient

was Lebanon, with remittances making up over 50 percent of its GDP. Tonga holds the number two

spot, with remittances making up over 40 percent of its GDP. The following three countries—Tajikistan,

Kyrgyz Republic, and Samoa—receive between 30 and 40 percent of their GDP in remittances. The next

three—The Gambia, El Salvador, and Honduras—each receive between 20 and 30 percent of their GDP in

remittances. The nal two are Jamaica and South Sudan, with remittances making up approximately 20

percent of their GDP.

Visa Economic Empowerment Institute Imagining an open future for payments

37

Figure 5: Digital remittance trends over 25 quarters, 2016-2022

This stacked bar plot displays the percentage of world remittance payments falling into one of three

categories—traditionally initiated, digitally initiated, and digital end-to-end—between Q2 2016 and Q2

2022, by quarter. In Q2 2016, traditionally initiated remittances made up 93 percent of the total, while

digitally initiated and digital end-to-end remittances made up 4 and 3 percent, respectively. Traditional

remittances continued to make up at least 90 percent of the total until Q3 2018, when they dipped down to

88 percent. At this time, digitally initiated remittances made up 8 percent of the total and digital end-to-end

remittances made up 4 percent. Traditional remittances continued to hover above 80 percent until Q2 2021,

when they dropped signicantly to 66 percent. By this time, digitally initiated remittances had climbed to

23 percent and digital end-to-end remittances to 11 percent. As of Q2 2022, traditional remittances still

make up 66 percent of the total, white digital end-to-end payments increased slightly to 13 percent and

digitally initiated payments dipped to 21 percent.

Figure 6: Remittance cost trends; $200 remittance, Q4 2019 – Q2 2022

This line plot displays the average cost of sending a remittance payment between Q4 2019 and Q2 2022

using three metrics—the global average, digital remittances index, and global SmaRT average. The global

SmaRT average reects what savvy consumers with access to suciently complete information could pay,

constructed by taking the average of the three lowest costs in each corridor. Throughout the period, the

global average remained highest, followed by the digital remittances index, and lastly, the SmaRT average.

In Q4 2019, the global average stood just shy of 7 percent, falling down to 6 percent by Q2 2022. The digital

remittances index stood at 5.5 percent in Q4 2019, falling almost a full percentage point by Q4 2021 and

increasing slightly in the rst two quarters of 2022. The SmaRT index stood just shy of 4.5 percent in Q4

2019, falling below 3.5 percent by Q2 2022.

Table 1: VEEI/DevTech corridor analysis of $200 and $500 remittances, 2021-2022

This table displays the average, lowest, and highest costs—in percent—of sending $200 and $500

remittances in 25 corridors during 2021 and 2022. Averaged out across all 25 corridors, the average,

lowest, and highest costs of sending $200 during 2021 were 4.24 percent, 2.96 percent, and 6.15 percent,

respectively. In 2022, the average and lowest costs dipped to 3.89 and 2.08 percent, while the highest cost

rose to 7.09 percent. Generally, the cost of sending $500 is lower. In 2021, the average, lowest, and highest

costs were 3.6, 2.46, and 5.36 percent, respectively. In 2022, the average and lowest costs dipped to 3.2 and

1.72 percent, while the highest cost rose to 5.69 percent. The table also displays the number of corridors

in which the cost of sending a $200 remittance payment is below 3 percent. In 2021, only eight of the 25

corridors saw average costs of less than 3 percent, down to seven in 2022. However, 18 of the 25 corridors

saw lowest costs of less than 3 percent in 2021, increasing to 20 corridors in 2022.

Figure 7: Averages of overall costs, lowest costs, and highest costs for sending a $200 remittance

This gure contains three box and whisker plots. The rst plot displays the distribution of the average cost—

in percent—of sending a $200 remittance payment across 25 corridors during 2021 and 2022. The second

displays the distribution of the lowest cost of sending $200, while the third displays the distribution of

the highest cost. Each plot also displays the mean costs for 2021 and 2022. The means for average, lowest,

and highest costs during 2021 were 4.24 percent, 2.96 percent, and 6.15 percent, respectively. In 2022, the

average and lowest costs dipped to 3.89 and 2.08 percent, while the highest cost rose to 7.09 percent.

OCT 2022The economic empowerment of digital remittances: How to unlock the benets of innovation and competition

38