Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law

Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Santa Clara Law Digital Commons

Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship

3-7-2022

Estimating the Earnings Loss Associated with a Criminal Record Estimating the Earnings Loss Associated with a Criminal Record

and Suspended Driver’s License and Suspended Driver’s License

Colleen Chien

Santa Clara University School of Law

Alexandra George

Srihari Shekhar

Santa Clara University

Robert Apel

Rutgers University - Newark

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs

Part of the Law Commons

Automated Citation Automated Citation

Colleen Chien, Alexandra George, Srihari Shekhar, and Robert Apel,

Estimating the Earnings Loss

Associated with a Criminal Record and Suspended Driver’s License

ARIZ. L. REV. (2022),

Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs/994

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital

Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara

Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Estimating the Earnings Loss Associated with a Criminal

Record and Suspended Driver’s License

Colleen Chien, Alexandra George, Srihari Shekhar, and Robert Apel

1

As states pass reforms to reduce the size of their prison populations, the number of Americans

physically incarcerated has declined. However, the number of people whose employment and

related opportunities are limited due to their criminal records continues to grow. Another

sanction is the loss of one's driver's licenses for reasons unrelated to driving. While many states

have laws on the books to redress these harms, a growing body of research has documented large

“second chance gaps” between eligibility and delivery of expungement and restored license

relief due to their poor administration. This paper is a first attempt to measure the cost of these

“paper prisons” of limited economic opportunity, in terms of annual lost earnings. Analyzing the

literature, we estimate the annual earnings loss associated with misdemeanor and felony

convictions to be $5,100 and $6,400, respectively, and that of a suspended license to be $12,700.

We use Texas as a case study for comparing the cost of “paper prisons” with the cost of physical

prisons. In Texas, individuals with criminal convictions may seal their records after a waiting

period and people that have lost driver’s licenses may get restored occupational driver’s licenses

to drive to work or school. Analyzing administrative data, this paper finds that approximately

5% of people eligible for relief have had their records sealed. The 670K people in the second

chance sealing gap translates to an annual earnings loss of about $3.5 billion annually. Using a

similar approach, we find that about 20% of the people that appear eligible for occupational

drivers’ licenses (ODLs) in Texas have received them, leaving about 430,000 people who could

have them without licenses; an earnings loss of about $5.5 billion. Based on these figures, we

find the cumulative annual earnings loss associated with Texas’s “paper prisons” to be

comparable with, and likely more than, the yearly cost to Texas of managing its physical prisons,

of around $3.6 billion.

1

(c) 2022 Colleen Chien is a Professor of Law at Santa Clara University School of Law, Alexandra George is a

graduate from Santa Clara University with degrees in Philosophy and Political Science, Srihari Shekhar is a graduate

student in the Masters of Information Science program at SCU, and Robert Apel is a criminologist and Professor at

Rutgers University-Newark. Corresponding author: Colleen Chien, [email protected]

1

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION 3

PART I: OVERVIEW OF TEXAS’ RECORD SEALING AND LICENSE REINSTATEMENT LAWS 6

Record Relief: Order of Non-Disclosure 8

Driver’s License Restoration: Occupational Driver’s License 11

Barriers to Relief Under Texas’s Second Chance Laws 13

PART II: ESTIMATING THE SIZE OF TEXAS’S SEALING AND DRIVER’S LICENSE

RESTORATION SECOND CHANCE GAPS 14

The Texas Criminal Population That Could Benefit from Sealing Relief 15

Table 1: The Population of People in Texas with Convictions 17

The Texas Population That Could Benefit from License Restoration Relief 18

Table A: Demographic Information About Population With Suspended Driver’s Licenses 20

Sizing Texas’s Second Chance Sealing Gap 21

Table 2: Estimated Eligibility and Uptake of Texas Record Sealing and Drivers Restoration 22

Sizing Texas’s Second Chance Driver’s License Restoration Gap 22

PART III: ESTIMATING THE ANNUAL EARNINGS IMPACTS OF A CRIMINAL CONVICTION

AND LOST DRIVER’S LICENSE AND THE EARNING IMPACTS OF TEXAS’ SECOND CHANCE

GAPS 25

Summary of Results 25

Table 3: The Size and Annual Earnings Losses Associated with Texas’s Second 25

Chance Sealing and Driver’s License Gaps 25

Estimating The Earnings Effect of Incarceration and Conviction 26

Table B. Estimates of Lost Annual Earnings from Conviction and Incarceration 29

Estimating the Earnings Impact of the Texas Second Chance Expungement (Sealing) Gap 30

The Earnings Effect of a Suspended Driver’s License 31

Comparing the Cumulative Earnings Effect of Texas’s Paper Prisons with the Out-of-Pocket Cost of

Texas’s Physical Prisons 34

PART IV: AUTOMATION AND POLICY PILOTS 34

CONCLUSION 40

APPENDIX 41

Sizing the Texas Sealing Second Chance Gap 41

2

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

INTRODUCTION

In 2002, Christian Watts was charged with felony drug possession after purchasing

MDMA (ecstasy) from a friend.

2

Watts pleaded guilty to a lower misdemeanor charge, and the

judge sentenced him to three months of house arrest and 36 months of probation.

3

At an average

cost of $9.17 per day, Watts’s supervision cost federal taxpayers $9,904.

4

But the consequences

of his conviction did not end there. Since Watts completed his sentence, he has been denied

civilian and military employment opportunities due to his record.

5

Despite earning Associates

and Bachelors degrees, and the praise of a judge for his self-rehabilitation efforts,

6

Watts has

been able to find work only as a dog walker and cross-fit trainer, jobs with average annual

incomes of around $35,000.

7

Commenting that “my life is stuck in a standstill,”

8

Watts has

abandoned plans to become a lawyer, a profession with an average annual income of about

$90,000.

9

These figures imply a potential earnings gap of $55,000 per year, and associated with

it, a gap in productivity, skills, and tax revenue.

In 2002, Demetrice Moore, a Certified Nursing Assistant, was convicted of grand larceny

and sentenced to jail and costs, including the cost of the lawyer appointed to represent her

because she was indigent.

10

Moore served her time, but could not repay the costs.

11

As a result,

her driver’s license was automatically suspended.

12

This interfered with her work because “[a]s a

12

Id.

11

Id.

10

Mario Salas & Angela Ciolfi, Driven by Dollars: A State-By-State Analysis of Driver’s License Suspension Laws

for Failure to Pay Court Debts, Lᴇɢᴀʟ Aɪᴅ Jᴜsᴛɪᴄᴇ Cᴇɴᴛᴇʀ, 3, (Fall 2017),

https://www.justice4all.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Driven-by-Dollars.pdf.

9

Prosecutor Salary in Las Vegas, NV, ZɪᴘRᴇᴄʀᴜɪᴛᴇʀ, (last visited November 5, 2021),

https://www.ziprecruiter.com/Salaries/Prosecutor-Salary-in-Las-Vegas,NV. See also U.S. ᴠ. Wᴀᴛᴛs, supra note 4

(Watts explaining that “I want to continue to further my education and have an active application into Boyd school

of law for this fall semester. I'm hoping to pursue a career as a prosecutor. Law school is costly and at 37 years old

loans of that magnitude can be daunting. I did not want this to deter me from accomplishing my goal. I came to

discover if I served my country in the military, not only can I satisfy my sense of duty, contribute to the greater

good, but the government will help me with the cost of my education. I want very much to enlist as an officer and

serve, possibly in the National Guard. However, no branch of the military will accept me with my current federal

drug conviction”).

8

Rʜᴏᴅᴀɴ, supra note 1.

7

Professional Dog Walker Salary in Las Vegas, NV, ZɪᴘRᴇᴄʀᴜɪᴛᴇʀ, (last visited November 5, 2021),

https://www.ziprecruiter.com/Salaries/Professional-Dog-Walker-Salary-in-Las-Vegas,NV and Fitness Trainer Salary

in Las Vegas, NV, ZɪᴘRᴇᴄʀᴜɪᴛᴇʀ, (last visited November 5, 2021),

https://www.ziprecruiter.com/Salaries/Fitness-Trainer-Salary-in-Las-Vegas,NV (listing average salaries at $30,830

and $37,602, respectively).

6

Id. and Rʜᴏᴅᴀɴ, supra note 1 (At Watts’ hearing, the judge said, “I wish I had far more people before me who

show the kind of self rehabilitation and effort that you’ve demonstrated” and even shook Watts’ hand.)

5

U.S. v. Watts, 2:04-CR-00146-PMP-RJJ (D. Nev. Apr. 25, 2011).

4

$9.17 per day x 30 days per month x 36 months = $9,903.60. For per day probation supervision costs, see

Supervision Costs Significantly Less than Incarceration in Federal System, Uɴɪᴛᴇᴅ Sᴛᴀᴛᴇs Cᴏᴜʀᴛs, (July 18, 2013),

https://www.uscourts.gov/news/2013/07/18/supervision-costs-significantly-less-incarceration-federal-system.

3

Id. and United States of America v. Watts. Case no: 2:04-0146-PMP-RJJ. Motion to Terminate Supervised Release.

June 3, 2009.

2

Maya Rhodan, Misdemeanor Conviction Is Not a Big Deal, Right? Think Again, Tɪᴍᴇ, (April 24, 2014),

https://time.com/76356/a-misdemeanor-conviction-is-not-a-big-deal-right-think-again/.

3

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

CNA, she had to drive extensively to care for elderly and disabled patients in their homes.”

13

Despite this, Moore attempted to keep working and was consequently convicted several times

and jailed for driving on a suspended license.

14

In the end, Moore had to “stop working as a CNA

because of the required driving.”

15

An average-to-experienced CNA makes around $33,000 to

$40,000 annually.

16

Many have commented on the massive size of the American criminal justice system and

celebrated reforms to reduce it.

17

But while the number of people put behind bars declines,

18

those who have old convictions and criminal records

19

continue to encounter structural barriers to

work or the deprivation of a driver’s license.

20

Among the freedoms curtailed by such actions,

economic liberty stands out. As the Supreme Court commented about suspended licenses in the

case of Bell v. Burson: “Once licenses are issued. . . their continued possession may become

essential in the pursuit of a livelihood. Suspension of issued licenses thus involves state action

that adjudicates important interests of the licensees.”

21

To remove these barriers, nearly every state has laws on the books that allow old,

generally minor, convictions to be expunged.

22

In many states, lost licenses can be restored in

22

In this article we use the word “expunged” to refer generally to the shielding of records from public view through

records remediations strategies such as sealing, orders of non-disclosure expungement, and expunction.

21

402 U.S. 535, 539, 1971.

20

See Kansas v. Glover, 589 U.S. ___ (2020) (in her concurring opinion, Justice Kagan notes that “several studies

have found that most license suspensions do not relate to driving at all; what they most relate to is being poor.” See

also Suspended/Revoked Working Group, Best Practices to Reducing Suspended Drivers, Aᴍᴇʀɪᴄᴀɴ Assᴏᴄɪᴀᴛɪᴏɴ ᴏғ

Mᴏᴛᴏʀ Vᴇʜɪᴄʟᴇs, 34-37, (February 2013),

https://www.aamva.org/Suspended-and-Revoked-Drivers-Working-Group/ (building off of the Department of

Transportation’s H.S. 811 092, “Reasons for Drivers License Suspension, Recidivism and Crash Involvement among

Suspended/Revoked Drivers,” this study estimates that, based on a sample of drivers from six states in the U.S., the

number of people who had licenses suspended for reasons unrelated to driving increased from 21% to 29% between

2002 and 2006). Some states have reported declines, however; see, e.g. Nina R. Joyce et al., Individual and

Geographic Variation in Driver’s License Suspensions: Evidence of Disparities by Race, Ethnicity, and Income, 19

Jᴏᴜʀɴᴀʟ ᴏғ Tʀᴀɴsᴘᴏʀᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Hᴇᴀʟᴛʜ 1, 4-5, 2020 (finding that, based on a random sample of about 7.6M drivers in

New Jersey, the prevalence of people with non-driving related suspensions between 2004 and 2018 decreased from

7.9% to 5%).

19

Becki Goggins, New Blog Series Takes Closer Look at Findings of SEARCH/BJS Survey of State Criminal History

Information Systems, 2016, Sᴇᴀʀᴄʜ, (March 29, 2018),

https://www.search.org/new-blog-series-takes-closer-look-at-findings-of-search-bjs-survey-of-state-criminal-history-

information-systems-2016/ (showing the growth in the number of subjects in state criminal history files, from ~81M

in 2006 to ~110M in 2016. These numbers, which represent biometric (fingerprint) data, contain duplicates).

18

John Gramlich, America’s incarceration rate falls to lowest level since 1995, Pᴇᴡ Rᴇsᴇᴀʀᴄʜ Cᴇɴᴛᴇʀ, (August 16,

2021), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/16/americas-incarceration-rate-lowest-since-1995/ (noting

that “[a]t the end of 2019, there were just under 2.1 million people behind bars in the U.S., including 1.43 million

under the jurisdiction of federal and state prisons and roughly 735,000 in the custody of locally run jails”)

17

See Overcrowding and Overuse of Imprisonment in the United States, Aᴍᴇʀɪᴄᴀɴ Cɪᴠɪʟ Lɪʙᴇʀᴛɪᴇs Uɴɪᴏɴ, (May

2015), https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/RuleOfLaw/Overincarceration/ACLU.pdf (discussing the causes of

the growth in the U.S.’s incarcerated population).

16

Nurse Journal Staff, Certified Nursing Assistant Salary Guide, NᴜʀsᴇJᴏᴜʀɴᴀʟ, (January 20, 2022),

https://nursejournal.org/cna/salary/.

15

Id.

14

Id.

13

Id.

4

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

order to support going to work or school.

23

But as an emerging literature has documented, the

poor administration of “second chance” policies means that many of the people, and often, the

majority, that stand to benefit from, e.g., expunged records or restored licenses, are not receiving

the benefits of these laws. One of us has defined this difference as the “second chance gap,” and

estimated its size across a number of realms, including expungement, restoration of the right to

vote, and resentencing.

24

An associated project, the Paper Prisons Initiative, has documented

uptake rates of records-expungement across over a dozen states, finding rates of less than 10%

— implying that over 90% of eligible people are not taking advantage of the law —- to be

common.

25

The economic impacts of paper prisons are more difficult to quantify than the

out-of-pocket costs of physical prisons, but they are still consequential. Though the total

unemployment rate in January 2022 was less than 4%, the last estimate of unemployment of

formerly incarcerated people living in the United States, published in 2018, reported an

unemployment rate of “over 27% — higher than the total U.S. unemployment rate during any

historical period, including the Great Depression,”

26

which figure was also close to triple the

national unemployment rate at the time.

27

But the fact that the cost of paper prisons is largely unquantified and unknown makes it

difficult to know how much to prioritize closing the gap. It also obscures the cost of the poor

drafting of second chance laws, which, in many cases, are extremely complicated and become

applicable only after numerous conditions have been satisfied.

28

Efforts to pass “Clean Slate”

bills that would help narrow the second chance gap have stalled across the country due to the

28

See Appendix A for a description of Texas's sealing law.

27

Kimberly Amadeo, Unemployment Rate by Year Since 1929 Compared to Inflation and GDP, Tʜᴇ Bᴀʟᴀɴᴄᴇ, (last

updated January 28, 2022), https://www.thebalance.com/unemployment-rate-by-year-3305506 (reporting a national

unemployment rate of 10% in 2009)

26

Lucius Couloute & Daniel Kopf, Out of Prison & Out of Work: Unemployment Among Formerly Incarcerated

People, Pʀɪsᴏɴ Pᴏʟɪᴄʏ Iɴɪᴛɪᴀᴛɪᴠᴇ, (July 2018), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/outofwork.html. (describing the

findings based on the National Former Prisoner Survey, conducted in 2008.)

25

Id. (noting that across a variety of second chance programs in the U.S., “ only a small fraction (less than 10

percent) of those eligible for relief actually received it”); See also J.J. Prescott and Sonja B. Starr, Expungement of

Criminal Convictions: An Empirical Study, 133 Hᴀʀᴠ. L. Rᴇᴠ. 2460, 2461 (2020) (finding that in Michigan “among

those legally eligible for expungement, just 6.5% obtain it within five years of eligibility”); Pᴀᴘᴇʀ Pʀɪsᴏɴs

Iɴɪᴛɪᴀᴛɪᴠᴇ, (last visited September 19, 2021), https://www.paperprisons.org/ (documenting the “uptake rate” of

expungement relief in states across the U.S.).

24

See Colleen Chien, America’s Paper Prisons: The Second Chance Gaps, 119 Mɪᴄʜ. L. Rᴇᴠ. 519, 519 (2020)

(analyzing a variety of second chance programs in the U.S. including clemency, compassionate release,

resentencing, and nonconvictions expungement, finding that in many cases “ only a small fraction (less than 10

percent) of those eligible for relief actually received it”).

23

See What is a hardship license vs. restricted license comparison, Iɴᴛᴏxᴀʟᴏᴄᴋ, (June 30, 2021),

https://www.intoxalock.com/blog/post/difference-between-hardship-and-restricted-license/ (describing that states

including Florida, Indiana, Wisconsin, Arkansas, and Kentucky all have“hardship licenses” that allow certain

individuals to have licenses for going to work, and California, Texas, Washington, Virginia, and Iowa have

“restricted licenses” that serve a similar purpose). Such licenses are also available to drivers in Pennsylvania

(Occupational Limited Licenses, Pᴇɴɴsʏʟᴠᴀɴɪᴀ Dᴇᴘᴀʀᴛᴍᴇɴᴛ ᴏғ Tʀᴀɴsᴘᴏʀᴛᴀᴛɪᴏɴ & Vᴇʜɪᴄʟᴇ Sᴇʀᴠɪᴄᴇs,

https://www.dmv.pa.gov/Information-Centers/Suspensions/Pages/Occupational-Limited-Licenses.aspx).

5

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

cost of updating records.

29

As the problem of paper prisons persists unabated, it is important to

quantify the economic costs of second chance gaps. This article does so by estimating the

earnings and employment consequences of old expungable convictions and lost driver’s licenses

that are available for restoration under existing law.

Part I of the article provides an overview of two of Texas’s second chance laws,

governing the grant of orders of non-disclosure (ONDs) and restoration of occupational driver’s

licenses (ODLs). It details the processes required to obtain each form of second chance relief and

explores how various administrative factors may contribute to gaps in their uptake. Part II then

describes the populations of people eligible for convictions and driver’s license relief, and our

methodology for estimating each second chance gap, measured by the number of individuals

with records who qualify for relief (“the current gap”), the share of people eligible for a given

second chance that have obtained it (“the uptake gap”), and the number of years it would take to

clear each second chance backlog based on the current pace of relief. Part III presents estimates

of the lost earnings and employment consequences associated with a criminal record and a lost

driver’s license. We then use these estimates and the findings from Part II to calculate the

earnings loss associated with Texas’s paper prisons.

We find that approximately 5% of people eligible for sealing relief have accessed it,

leaving a gap of about 670,000 people (with people in the gap having a last conviction, on

average, of 17 years ago). We estimate the earnings loss associated with this gap to be

approximately $3.5 billion annually. Using a similar approach, we find that about 20% of people

eligible for occupational drivers licenses (ODLs) in Texas have accessed them, leaving a gap of

430,000 people eligible for ODLs who have not gotten one, which translates into an earnings

loss of about $5.5 billion. Based on these figures, we find the cumulative annual earnings loss

associated with Texas’s “paper prisons” to exceed the yearly cost of funding physical prisons in

Texas, which is around $3.6 billion.

PART I: OVERVIEW OF TEXAS’ RECORD SEALING AND LICENSE

REINSTATEMENT LAWS

For our exploration of the economic impacts of the second chance gap, we used Texas as

a case study for a few reasons. First, Texas has the 9th largest economy in the world by GDP, and

prides itself on being business-friendly and a reliable source of skilled workers.

30

Secondly, like

many states, Texas has been under fiscal pressure to reform and reduce the costs of its criminal

30

https://businessintexas.com/news/texas-enters-2021-as-worlds-9th-largest-economy-by-gdp/ (describing the

benefits of Texas for businesses as including “highly competitive tax climate, world-class infrastructure, a skilled

workforce of 14 million people, business-friendly economic policies and abundant quality of life,”

29

See, e.g. Washington state, which in 2020 passed a “Clean Slate” bill that would have narrowed but which the

Governor vetoed due to cost,. Iin part exacerbated by the anticipated cost of COVID expenditures. Rachel M.

Cohen, Washington Governor Vetoes Bill that Would Have Automatically Cleared Criminal Records, Tʜᴇ Aᴘᴘᴇᴀʟ,

(May 19, 2020), https://theappeal.org/politicalreport/washington-governor-vetoes-clean-slate-bill/.

6

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

justice system and has led the country in many respects in doing so.

31

As part of this reform,

policymakers and politicians have widely celebrated the cost savings associated with closing

Texas’s physical prisons.

32

However, while the number of Texans who were incarcerated in state

prisons and jails decreased by 27% between fiscal years 2005 and 2020,

33

individuals with

criminal history in the state doubled over the same period, according to repository consortium

SEARCH.

34

There are 5 million people in Texas’s database of people with convictions, and,

before the law was reformed in 2020, 1.4 million Texans, or 5% of the population, had

suspended licenses.

35

As such, the extent to which people with records and suspended licenses

are integrated — or not — into the workforce has significant consequences for the Texas

economy.

35

At least 400,000 licenses remain suspended though the elimination of a controversial program restored 1.4M

licenses. Letter from Department of Public Safety to Karly Jo Dixon from the Texas Fair Defense Project. Letter on

file with authors. For more on the significance of the repeal of the controversial program, see Emily Gerrick & Mary

Mergler, Commentary: Lawmakers Need to fix another problem that buries Texas drivers in fines, Sᴛᴀᴛᴇsᴍᴀɴ, (last

updated July 5, 2020), https://www.austintexas.gov/edims/document.cfm?id=340640 (noting that “[we]e cannot

overstate how significant the repeal of this program is. When the law goes into effect in September, 1.4 million

license suspensions will be lifted, and nearly $2.5 billion of surcharge debt will be wiped clean. Huge numbers of

people will escape the cycle of suspensions and get back on the road driving legally. This repeal will help vulnerable

Texans achieve financial stability, save taxpayer dollars and boost the Texas economy.”)

34

Data from bi-annual Survey of State Criminal History Information Systems, SEARCH (2020, 2008, 2009, 2011,

2014, 2015, 2018, 2020) at Table 1. (2020 report available e.g. at

https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bjs/grants/255651.pdf). In 2006, the repository had 7,986,000 records (Bureau of

Justice Statistics, Survey of State Criminal History Information, 2003, U.S. Dᴇᴘᴀʀᴛᴍᴇɴᴛ ᴏғ Jᴜsᴛɪᴄᴇ, (February

2006), https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/sschis03.pdf), in 2018 that number was 15,437,000 (Becki R. Goggins &

Dennis A. DeBacco, Survey of State Criminal History Information Systems, 2016: A Criminal Justice Information

Policy Report, Sᴇᴀʀᴄʜ, (February 2018), https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bjs/grants/251516.pdf).

33

From 152,213 people to 142,169 people. This excludes participants in the Substance Abuse Felony Program. See

Statistical Reports, Tᴇxᴀs Dᴇᴘᴀʀᴛᴍᴇɴᴛ ᴏғ Cʀɪᴍɪɴᴀʟ Jᴜsᴛɪᴄᴇ (2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013,

2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005) at 8 (all reports as of January 21, 2022 available at

https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/publications/statistical_reports.html).

32

In 2020, for example, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice projected that closing two Texas prisons would

“free up about $20 million in its budget.” Julie McCullogh, As the Texas prison population shrinks, the state is

closing two more lockups, Tʜᴇ Tᴇxᴀs Tʀɪʙᴜɴᴇ, (February 20, 2020),

https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/news/2020/02/21/361405/as-the-texas-prison-population-shrinks-the-st

ate-is-closing-two-more-lockups/. This followed a 2017 estimate that Texas could “eliminate more than 2,000

beds...[and] save the state some $49.5 million” from closing four prisons. Brandi Grissom, With crime,

incarceration, rates falling, Texas closes record number of prisons, Tʜᴇ Dᴀʟʟᴀs Mᴏʀɴɪɴɢ Nᴇᴡs, (July 5, 2017),

https://www.dallasnews.com/news/politics/2017/07/05/with-crime-incarceration-rates-falling-texas-closes-record-nu

mber-of-prisons/.

31

Michael Haugen, Ten Years of Criminal Justice Reform in Texas, Rɪɢʜᴛ ᴏɴ Cʀɪᴍᴇ, (August 1, 2017),

https://rightoncrime.com/2017/08/ten-years-of-criminal-justice-reform-in-texas/ (describing states adopting justice

reinvestment packages similar to the ones in Texas).

7

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

Sources: Texas Department of Criminal Justice's Annual Statistical Reports for fiscal years 2005 through 2020 (for

jail and prison population data)

36

; SEARCH (for criminal subjects data).

37

Third, over the past several decades, Texas has introduced laws that advance both

criminal justice and workforce-related objectives, allowing individuals with old convictions to

get them sealed and individuals that have lost their licenses a chance to regain their right to drive

to work or school. The scale of Texas’s criminal justice system and its adoption of many second

chance reforms, as well as the lack of attention paid to their implementation, make the state a

good subject for study and analysis.

This section provides an overview of Texas’s second chance laws, describing their

legislative history and the processes set forth by the law for obtaining relief. These laws share the

goals of advancing economic interests and removing barriers to work, as well as preserving

public safety.

A. Record Relief: Order of Non-Disclosure

In Texas, every time a person is convicted of a crime, this event is memorialized in the

37

Based on data obtained from Becki Goggins et al; Survey of State Criminal History Information Systems, 2020: A

Criminal Justice Information Policy Report, available at https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bjs/grants/255651.pdf,

Table 1 (listing the total number of records in the state repository as of Dec 2018) (2020) and previous versions of

the report, at Table 1.

36

Data about the size of the on hand state jail and prison population obtained from Annual Statistical Reports, Tᴇxᴀs

Dᴇᴘᴀʀᴛᴍᴇɴᴛ ᴏғ Cʀɪᴍɪɴᴀʟ Jᴜsᴛɪᴄᴇ, 8 (2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009,

2009, 2007, 2006, 2005) (reports last available on January 23, 2022,

https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/publications/statistical_reports.html). Even though the TDCJ places people in jail, prison,

and Substance Abuse Felony Punishment Facility (SAFP) Program in the same “on hand” category in its annual

reports, we exclude the number of people in the SAFP Program from our estimate of the size of the state's prison and

jail population.

8

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

person’s criminal record, which sets off various “collateral consequences,” or civil punishments

that follow a person long after time has been served. The National Inventory of Collateral

Consequences of Conviction has cataloged over 1,600 civil sanctions in Texas alone for people

with criminal records spanning child support, employment, volunteering, civic participation, real

estate, visitation and parental rights, and housing residency.

38

People with certain criminal

records are disqualified from numerous top jobs for people without college degrees. “Private

security” on the Texas Labor Analysis’ list of the top 25 projected occupations for individuals

with a maximum education of postsecondary non-degree,

39

with wages from ~$21,000 to

~$37,000,

40

is one of them.

41

In an effort to give people a second chance and allow them to more easily find

employment, the Texas Legislature passed Texas Gov. Code Chap. 411, creating two pathways

for individuals to remove their past criminal records from public access. The first pathway

provides relief via an expunction, which occurs when all “information about an arrest, charge, or

conviction [is removed] from [one’]s permanent records.”

42

Expunction is only available for

felony and Class A, B, and C misdemeanor nonconvictions.

43

In contrast, the second pathway, an

“Order of Nondisclosure” (OND), seals records from the general public, while allowing certain

employers and government agencies to “see through” the OND.

44

Sealing via OND is available

to people convicted of first-time low-level misdemeanor convictions as well as to those who

completed deferred adjudication community supervision (“deferred adjudication”) for low-level

offenses. This article focuses only on sealing of convictions because the earnings impact of a

conviction is recognized to be much more significant than a non-conviction.

45

As such, we will

use “sealing” throughout the remainder of the article to refer exclusively to record relief granted

using the OND pathway.

In 2003, S.B. 1477 put the OND pathway on the books in Texas,

46

in an effort to remove

46

Id.

45

See Chien, supra note ___ at ___. (providing an overview of this impact literature) [pin/add’l parenthetical

needed]

44

Expunctions in Texas, Tᴇxᴀs Yᴏᴜɴɢ Lᴀᴡʏᴇʀs Assᴏᴄɪᴀᴛɪᴏɴ & ᴛʜᴇ Sᴛᴀᴛᴇ Bᴀʀ ᴏғ Tᴇxᴀs, 5, (2010 and 2019),

https://www.texasbar.com/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Our_Legal_System1&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&

ContentID=23459 and Tex. Gov. Code Sec. 411.0765. Thank you to Derek Cohen of the Texas Policy Lab for

raising this to us in a comment on a previous draft.

43

Id.

42

Texas Code of Criminal Procedure Art. 55.01 (2005). For more on the legislature’s intent for expunction to redress

the harm associated with criminal justice involvement, see also State v. T.S.N, 547 S.W.3d 617 (Tex. 2018) (noting

that the state’s expunction statute allows for expunction “in limited, specific circumstances…[with the] intent to,

under certain circumstances, free persons from the permanent shadow and burden of an arrest record, even while

requiring arrest records to be maintained for use in subsequent punishment proceedings and to document and deter

recidivism.”

41

Collateral Consequences Inventory, Nᴀᴛɪᴏɴᴀʟ Iɴᴠᴇɴᴛᴏʀʏ ᴏғ Cᴏʟʟᴀᴛᴇʀᴀʟ Cᴏɴsᴇᴏ̨ᴜᴇɴᴄᴇs, supra note ___ (specify

“private security, investigations, and locksmiths” as a keyword.)

40

Demand Analysis - Occupational Detail - Texas - Security Guards (SOC 33-9032), Tᴇxᴀs Lᴀʙᴏʀ Aɴᴀʟʏsɪs, Report

generated August 27, 2021.

39

Top Statistics - Texas - Projections - No Education Requirement, High School Diploma, or Postsecondary

Non-Degree, Tᴇxᴀs Lᴀʙᴏʀ Aɴᴀʟʏsɪs, Report generated August 27, 2021.

38

Collateral Consequences Inventory, Nᴀᴛɪᴏɴᴀʟ Iɴᴠᴇɴᴛᴏʀʏ ᴏғ Cᴏʟʟᴀᴛᴇʀᴀʟ Cᴏɴsᴇᴏ̨ᴜᴇɴᴄᴇs, (last visited November 5,

2021), https://niccc.nationalreentryresourcecenter.org/consequences (select “Texas”).

9

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

impositions on a “person's ability to obtain a desired job or position for many years after the

offense.”

47

In 2015, the 84th Texas Legislature passed S.B. 1902 to “[give] reformed offenders a

second chance, creating a safer Texas, and increasing the workforce with individuals who are no

longer limited by their minor criminal histories” by making sealing of deferred adjudication

dismissals “automatic.”

48

This was followed two years later by H.B. 3016 to further expand

eligibility.

49

Despite these revisions, the scope of Texas’s record sealing law remains narrow. Offenses

that are given deferred adjudication up to a maximum duration

50

are eligible for relief following

successful completion of community supervision and dismissal.

51

First offense misdemeanor

convictions, after a two-year waiting period following sentence completion, are also generally

eligible as long as there have been no prior convictions or deferred adjudications.

52

First-time

driving while intoxicated (DWI) offenses are eligible after a two-to-five year waiting period.

53

Offenses involving violence besides simple assault, sex crimes, or a handful of other crimes,

54

or

that are committed by individuals who have been convicted of certain crimes, are disqualified or

have longer waiting periods.

55

There are two processes people can use to apply for record sealing. The first process, the

petition route, is used for convictions, most misdemeanors and felonies given deferred

adjudication.

56

The petition process starts with an individual submitting a petition and a fee to the

“clerk of the court. . . that sentenced [them] or placed [them] on community supervision. . . or

56

Tex. Gov’t Code §§411.0735 and 411.0725. See also Nondisclosure - Procedure for Deferred Adjudication - for

Felonies and Certain Misdemeanors - Under Section 411.0725, Tᴇxᴀs Lᴀᴡ Hᴇʟᴘ, (last updated January 22, 2022),

https://texaslawhelp.org/article/nondisclosure-procedure-for-deferred-adjudication-for-felonies-and-certain-misdeme

anors-under; Nondisclosure - Procedure for Conviction for Certain Misdemeanors - Under Section 411.0735, Tᴇxᴀs

Lᴀᴡ Hᴇʟᴘ, (January 21, 2022),

https://d9.texaslawhelp.org/article/nondisclosure-procedure-for-conviction-for-certain-misdemeanors-under-section-

4110735.

55

Tex. Gov. Code §411.0735(c-1) (2015). People are ineligible to have their records sealed if they have ever been

convicted of or received deferred adjudication for offenses including homicide, human trafficking, aggravated

kidnapping, child or elder abuse, stalking, and offenses that require registration as a sex offender. Texas Government

Code §411.074(b) (2015). Payment of legal financial obligations, if required for sentence completion, is also

required. Texas Government Code §411.0735(b) (2015); Texas Government Code §411.0736(b) (2017).

54

Including Boating while intoxicated (Penal Code §49.06), Flying while intoxicated (Penal Code §49.05),

Assembling or operating an amusement ride while intoxicated (Penal Code §49.065), or Organized Crime (Penal

Code Chapter 71)

53

Tex. Gov’t Code §411.0736 (2017).

52

Tex. Gov’t Code §§ 411.073, 411.0735. Some convictions have a shorter waiting period, but for simplicity and to

be conservative, we do not model these shorter periods, as described in the Appendix.

51

Texas Government Code §42A.102, Texas Government Code §411.0725.

50

A maximum of 2 years of community supervision following misdemeanors and 10 years of community

supervision for a felony. Art. 42A.103

49

Senfronia Thompson et al., C.S.H.B. 3016 Bill Analysis, Sᴇɴᴀᴛᴇ Rᴇsᴇᴀʀᴄʜ Cᴇɴᴛᴇʀ, (May 18, 2017),

https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/85R/analysis/pdf/HB03016S.pdf#navpanes=0.

48

Charles Perry, S.B. 1902 Bill Analysis, Sᴇɴᴀᴛᴇ Rᴇsᴇᴀʀᴄʜ Cᴇɴᴛᴇʀ, 1, (April 17, 2015),

https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/84R/analysis/pdf/SB01902I.pdf#navpanes=0.

47

Royce West, C.S.S.B. 1477 Bill Analysis, Sᴇɴᴀᴛᴇ Rᴇsᴇᴀʀᴄʜ Cᴇɴᴛᴇʀ, 1, (May 8, 2003),

https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/78R/analysis/pdf/SB01477S.pdf#navpanes=0.

10

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

deferred adjudication. . . .”

57

Although the filing fee can vary by county,

58

“the petition must be

accompanied by payment of a $28 fee to the clerk of the court in addition to any other fee that

generally applies to the filing of a civil petition.”

59

After submitting a petition, the court holds a

trial to determine whether the petitioner is eligible for sealing and whether sealing the

petitioner’s record “is in the best interests of justice.”

60

If the court answers both questions

affirmatively, the relief is granted and the record is sealed.

61

The second process of sealing one’s record, the submission route, is used only for

nonviolent first-time misdemeanor offenses that received a deferred adjudication community

supervision sentence that was completed and dismissed on or after September 1, 2017.

62

The

submission route does not require a petition.

63 64

Instead, to initiate the process, the applicant

must “[p]resent evidence necessary to establish that [they] are eligible to receive an order under

Section 411.072,” which typically involves filing a Letter Requesting an Order of Nondisclosure

Under Section 411.072.

65

When submitting the Letter to the clerk, the applicant must also pay a

$28 fee or request a fee waiver.

66

A judge will then review the evidence and seal the record if the

applicant meets the eligibility criteria.

67

Despite the procedural differences between the two

record sealing processes, both involve legal fees, court fees, and a petition initiated by the

applicant, which requires awareness of both eligibility and the possibility of sealing.

B. Driver’s License Restoration: Occupational Driver’s License

In Texas, individuals can lose their licenses for a variety of reasons ranging from minor

driving-related offenses (e.g., not having insurance, outdated registration, or not signaling

68

), to

68

Chris Abel, Failure to Appear and Traffic Violations, Aʙᴇʟ Lᴀᴡ Fɪʀᴍ, (last visited September 20, 2021),

https://www.flowermoundcriminaldefense.com/failure-appear-and-traffic-violations.

67

Id., 11.

66

Id., 11-12.

65

Id., 11.

64

Texas Criminal Law: Orders of Nondisclosure, Sᴀᴘᴜᴛᴏ Lᴀᴡ, (last visited September 18, 2021),

https://saputo.law/criminal-law/record-clearing/orders-of-nondisclosure/ (also explaining that although some call

this type of OND “automated,” this is misleading because an individual must still initiate the process).

63

Id.

62

Nondisclosure - Deferred Adjudication Community Supervision for Certain Nonviolent Misdemeanors - Under

Section 411.072, Tᴇxᴀs Lᴀᴡ Hᴇʟᴘ, (last updated January 21, 2022),

https://texaslawhelp.org/article/nondisclosure-deferred-adjudication-community-supervision-for-certain-nonviolent-

misdemeanors-under.

61

Id.

60

Collateral Consequences Resource Center, Texas: Restoration of Rights & Record Relief, Rᴇsᴛᴏʀᴀᴛɪᴏɴ ᴏғ Rɪɢʜᴛs

Pʀᴏᴊᴇᴄᴛ, (last updated May 20, 2021),

https://ccresourcecenter.org/state-restoration-profiles/texas-restoration-of-rights-pardon-expungement-sealing/.

59

Texas Administrative Code §411.0745(b) (2015).

58

Orders of Nondisclosure Overview, Tᴇxᴀs Oғғɪᴄᴇ ᴏғ Cᴏᴜʀᴛ Aᴅᴍɪɴɪsᴛʀᴀᴛɪᴏɴ, 5, (last updated April 2017),

https://www.txcourts.gov/media/821650/order-of-nondisclosure-overview.pdf.

57

An Overview of Orders of Nondisclosure, Tᴇxᴀs Oғғɪᴄᴇ ᴏғ Cᴏᴜʀᴛ Aᴅᴍɪɴɪsᴛʀᴀᴛɪᴏɴ, 2, (last updated January 2020),

https://www.txcourts.gov/media/1445464/overview-of-orders-of-nondisclosure-2020.pdf.

11

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

serious driving offenses (e.g., “a habitually reckless or negligent operator of a motor vehicle”

69

).

Individuals can also lose their driver’s license for non-driving related offenses, such as “fail[ing]

to appear for a citation (FTA) or fail[ing] to satisfy a judgment ordering the payment of a fine” or

fee.

70

Once an individual loses their driver’s license, that person is faced with a difficult choice:

find alternatives for basic tasks like driving to work or school, or risking further criminalization

if they are caught driving without a license.

71

To redress the productivity-related harms associated with not having a driver’s license,

72

Texas Transportation Code Section 521 Subchapter L allows certain individuals to apply for an

Occupational Driver’s License (ODL) to regain their rights to drive to work and school. The

legislative history suggests that the goal of providing ODLs was to support employment. For

instance, in 1969 Senator William T. Moore noted that “[t]he law relating to driver’s licenses is

now discriminatory in that it deprives many persons of the privilege of following their

occupations and earning a living.”

73

S.B. 743, which “provide[d] for the issuance of an

occupational license to certain people who have had their license suspended” followed.

74

In 2015

the 84th Legislature passed H.B. 2246 to both balance the need for public safety, vis-a-vis

individuals with licenses suspended due to past intoxication, with the desire to help such

individuals “continue to support themselves and their families.”

75

To effect this goal, ODLs were

made available following the installation of an ignition interlock device.

76

A more recent, related development to restore driver’s licenses was the 2019 repeal of the

Driver's Responsibility Program (DRP), which controversially imposed large fines for often

minor traffic offenses (e.g., speeding or driving without insurance) for the funding of trauma

centers in rural areas.

77

The program’s end resulted in the restoration of thousands of licenses.

77

Described by Morgan Smith, To pay for trauma centers, state program sinks thousands of Texas drivers into deep

debt, Tʜᴇ Tᴇxᴀs Tʀɪʙᴜɴᴇ, (August 27, 2018),

https://www.texastribune.org/2018/08/27/pay-trauma-centers-texas-sinks-thousands-drivers-deep-debt/ (describing

how the program, originally intended to "hold bad drivers responsible for the damage they caused, with the license

suspensions having the added benefit of keeping them off the roads" was eventually seen as a “massive failure”).

See also Matthew Menendez et al., Fees and Fines: A Fiscal Analysis of Three States and Ten Counties, Bʀᴇɴɴᴀɴ

Cᴇɴᴛᴇʀ ғᴏʀ Jᴜsᴛɪᴄᴇ, 26, (November 21, 2019),

https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/steep-costs-criminal-justice-fees-and-fines.

76

Texas Transportation Code §521.244(e). (creating OND eligibility based on evidence of financial responsibility

and proof of the installation of an ignition interlock device on each motor vehicle operated by the individual.)

75

Jason Villalba et al., H.B. 2246 Bill Analysis, Sᴇɴᴀᴛᴇ Rᴇsᴇᴀʀᴄʜ Cᴇɴᴛᴇʀr, (May 18, 2015),

https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/84R/analysis/pdf/HB02246E.pdf#navpanes=0.

74

Id.

73

William T. Moore, S.B. 753 Bill Analysis, Sᴇɴᴀᴛᴇ Rᴇsᴇᴀʀᴄʜ Cᴇɴᴛᴇʀ, 8, (May 7, 1969),

https://lrl.texas.gov/LASDOCS/61R/SB743/SB743_61R.pdf#page=8.

72

As recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court, see Bell v. Burson (1971), supra note __.

71

Driven By Debt, Tᴇxᴀs Aᴘᴘʟᴇsᴇᴇᴅ ᴀɴᴅ Tᴇxᴀs Fᴀɪʀ Dᴇғᴇɴsᴇ Pʀᴏᴊᴇᴄᴛ, (December 13, 2018),

https://report.texasappleseed.org/driven-by-debt/.

70

Failure to Appear/Failure to Pay Program, Tᴇxᴀs Dᴇᴘᴀʀᴛᴍᴇɴᴛ ᴏғ Pᴜʙʟɪᴄ Sᴀғᴇᴛʏ, (last visited September 20,

2021), https://www.dps.texas.gov/section/driver-license/failure-appearfailure-pay-program.

69

Texas Government Code §521.292(a)(2) (1999). See also Driver’s License Enforcement Actions, Tᴇxᴀs

Dᴇᴘᴀʀᴛᴍᴇɴᴛ ᴏғ Pᴜʙʟɪᴄ Sᴀғᴇᴛʏ, (last visited September 20, 2021),

https://www.dps.texas.gov/internetforms/Forms/DL-176.pdf (listing the reasons individuals can have their licenses

revoked, suspended, and/or disqualified).

12

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

However, “an estimated 500,000 individuals’ licenses remained suspended after their DRP

surcharges were eliminated,”

78

a figure consistent with the data reported in this study.

To obtain an ODL under Texas Transportation Code Section 521 Subchapter L, one must

demonstrate “an essential need” for the ODL, for example as evidenced by the need to drive to

work or to school, and a lack of an alternative transportation option.

79

However, individuals are

ineligible for ODLs if they have “lost [their] driving privileges because of a mental or physical

disability,” have “lost [their] driving privileges for failure to pay child support,” have “received

two ODLs in the past 10 years after a conviction,” or “have a ‘hard suspension’ waiting period

due to a prior DWI arrest or conviction.”

80

ODLs are also unavailable to individuals who need a

license to drive a commercial motor vehicle.

81

To obtain an ODL, an eligible individual must complete a petition, in accordance with

local court requirements.

82

Next, the applicant must file the petition and submit a filing fee.

83

If

their license was “automatically suspended or canceled following a conviction, [the applicant

should] file the Petition in the same court that convicted [them].”

84

If not, they can choose to file

the petition “in the county where [they] live or where the offense occurred.”

85

Following filing,

there is a hearing where a judge reviews the petition and other paperwork of the petitioner,

including a Certified Abstract of the petitioner’s full driving record, an SR-22 Proof of Insurance

from the petitioner’s insurance company, and evidence that the petitioner needs the license to go

to work, attend school, etc.

86

The judge will then decide whether to grant an ODL.

87

C. Barriers to Relief Under Texas’s Second Chance Laws

As discussed above, Texas enacted its record sealing and driver’s relicensing laws with

the goals of reducing the size of the criminal justice system and increasing accessibility to

second chances and workforce opportunities. However, three administrative burdens placed on

applicants by the second chance laws limit the legislature’s success in meeting these goals.

88

88

A related area of literature about administrative burdens is growing quickly. For instance, see Julian Christensen

et al., Human Capital and Administrative Burden: The Role of Cognitive Resources in Citizen-State Interactions, 80

Pᴜʙʟɪᴄ Aᴅᴍɪɴɪsᴛʀᴀᴛɪᴏɴ Rᴇᴠɪᴇᴡ 127, (January/February 2020) (describing the ways in which “citizens with lower

levels of human capital” experience greater administrative burdens, which contributes to reinforcing inequality);

Pᴀᴍᴇʟᴀ Hᴇʀᴅ & Dᴏɴᴀʟᴅ P. Mᴏʏɪɴʜᴀɴ, Aᴅᴍɪɴɪsᴛʀᴀᴛɪᴠᴇ Bᴜʀᴅᴇɴ: Pᴏʟɪᴄʏᴍᴀᴋɪɴɢ ʙʏ Oᴛʜᴇʀ Mᴇᴀɴs (2018) (arguing

that administrative burdens are conscious policy choices); Elizabeth Linos et al., Nudging Early Reduces

Administrative Burden: Three Field Experiments to Improve Code Enforcement, 39 Jᴏᴜʀɴᴀʟ ᴏғ Pᴏʟɪᴄʏ Aɴᴀʟʏsɪs ᴀɴᴅ

87

Id.

86

Id.

85

Id.

84

Id.

83

Supra note 75, 3.

82

Id, 2.

81

Id.

80

Id. For more on hard suspension waiting periods, see Occupational Driver’s License, Tᴇxᴀs Lᴀᴡ Hᴇʟᴘ, (last

updated June 2, 2021), https://texaslawhelp.org/guide/occupational-drivers-license/?tab=0.

79

Texas Occupational Driver’s License, 1, (last visited January 20, 2022),

https://www.co.chambers.tx.us/upload/page/0100/docs/Occupational%20DL/BrochureODL.pdf.

78

Tᴇxᴀs Lᴀᴡ Hᴇʟᴘ, supra note 72.

13

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

First, the petition process in both cases requires an individual not only to prove they deserve a

second chance, but also to ascertain the law and fill out potentially confusing paperwork.

Second, the requirement that individuals seeking a second chance attend a hearing similarly

burdens people with challenges ranging from getting a hearing on the calendar (which requires

successfully submitting a petition) to attending a hearing (which can involve taking time off of

work, traveling, etc.). Third, complex criteria that frequently evolve make it difficult for

individuals to keep up with the law and determine their eligibility. These administrative barriers

to petitioners not only contrast with the automatic removal of rights and collateral consequences

after a misdemeanor conviction, incarceration, or the suspension of a driver’s license, but also

contribute to the gap in delivery of record cleaning and license restoration, as quantified in the

next part.

PART II: ESTIMATING THE SIZE OF TEXAS’S SEALING AND DRIVER’S LICENSE

RESTORATION SECOND CHANCE GAPS

89

While Texas legislatures have passed second chance laws to advance a variety of goals,

the benefits of second chance relief depend on its delivery. In this part, we start by profiling the

people in each target population. Analyzing criminal convictions data from the state, we find

individuals with convictions on average to be of working age (mid-40s) and on average, have a

last conviction from over a decade ago. The available evidence suggests that people with

suspended licenses appear to be a bit younger (30-40), and have their licenses suspended on

average for five years and seven months.

To ascertain the number of people eligible to have their convictions sealed,

90

we applied a

simplified version of the sealing law to criminal convictions records to estimate the size of

Texas’s “second chance sealing gap” and “second chance driver restoration gap.” Based on our

analysis, we estimate that about 670,000 people are able to have their records cleared, 59,000

people completely, to achieve a “clean slate” under existing law (Table 1). For this eligible

population, the average number of years since the last conviction is about 17 (median = 15

years). Furthermore, 430,000 people appear eligible to apply for an ODL to drive to work or

school. These numbers translate into a 5% and 17% uptake rate of sealing and driver’s license

reinstatements, respectively. (Table 1)

A. The Texas Criminal Population That Could Benefit from Sealing Relief

90

Cʜɪᴇɴ, supra note 20.

89

Language modified and adapted from Colleen Chien et al., The Texas Second Chance Non-Disclosure/Sealing

Gap, Pᴀᴘᴇʀ Pʀɪsᴏɴs Iɴɪᴛɪᴀᴛɪᴠᴇ, (last visited January 21, 2022), https://www.paperprisons.org/states/TX.html.

Mᴀɴᴀɢᴇᴍᴇɴᴛ 243, (Winter 2020) (uses a field experiment to demonstrate that learning costs, compliance costs, and

psychological costs help to explain why residents do not always take up programs for which they are eligible”); Cass

R. Sunstein, Sludge and Ordeals, 68 Dᴜᴋᴇ L. J. 1843, (2019) (argues that deregulation driven by data and behavioral

information should be undertaken due to the 9.78 billion hours of “sludge” paperwork Americans completed in 2018

for the government, but notes that such deregulation will be filled with numerous tradeoffs).

14

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

Before estimating the size of the population entitled to second chance relief, it is worth

considering the current size and characteristics of the existing Texas criminal population, as

reflected in the dataset upon which we rely for our records sealing analysis: the Texas

Computerized Criminal History System (CCH). Maintained by the Texas Department of Public

Safety, the CCH is a database containing all publicly available convictions for adults from 1976

to the date of extraction.

91

This database is quite large, containing over 5.2 million Texans who

have publicly available convictions records. However, the true size of Texas's conviction

population is smaller because the CCH data likely includes individuals who are deceased. To

account for this, we removed all individuals over the age of 80 years old from the dataset on the

basis that the average life expectancy for Americans in 2019 was 78.8 years.

92

After doing so, we

estimate that approximately 4.8 million Texans (~16.4% of the state’s adult population in 2020)

have publicly available convictions records.

93

This estimate is at best an approximation because

it fails to account for the thousands of people who move in and out of the Lone Star State each

year. This database also does not include people with non-conviction and deferred

adjudication-only records, who are also eligible for records relief under the law.

94

Analyzing a random sample selected from the database of 150,000 people, we find that

about 80% have felony convictions and 62% have misdemeanor convictions. The most common

charges include drug possession, driving while intoxicated, and felony burglary as well as

misdemeanor assault causing bodily injury to a family member (Appendix Table 1). Consistent

with general trends, the population is overwhelmingly male. But while the average

94

See Appendix __ for details.

93

America Counts Staff, Texas Added Almost 4 Million People Last Decade, Uɴɪᴛᴇᴅ Sᴛᴀᴛᴇs Cᴇɴsᴜs Bᴜʀᴇᴀᴜ,

(August 25, 2021),

https://www.census.gov/library/stories/state-by-state/texas-population-change-between-census-decade.html. ~16.4%

= 4.8M divided by Texas's adult population in 2020, which we calculated by multiplying the size of Texas's

Population in 2020 (29,145,055 people) by the percentage of the population over the age of 18 (75%).

92

National Center for Health Statistics, Life Expectancy, Cᴇɴᴛᴇʀs ғᴏʀ Dɪsᴇᴀsᴇ Cᴏɴᴛʀᴏʟ ᴀɴᴅ Pʀᴇᴠᴇɴᴛɪᴏɴ, (January 8,

2022), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/life-expectancy.htm.

91

About CCH, Tᴇxᴀs Dᴇᴘᴀʀᴛᴍᴇɴᴛ ᴏғ Pᴜʙʟɪᴄ Sᴀғᴇᴛʏ, (last visited August 20, 2021),

https://publicsite.dps.texas.gov/DpsWebsite/CriminalHistory/AboutCch.aspx (also see this source for more about the

CCH). Per the Department of Public Safety, “Computerized Criminal History (CCH) was created in 1976 and we

began sending the conviction database in 1998. A person’s criminal history is retained for 125 years from their date

of birth.” See email from Texas Department of Public Safety, on file with editors. < for editors:

https://app.sparkmailapp.com/web-share/sW1CF6EOzhRBYaJTOh-6TdDpbW6qQLxd8W2CwfVq >

15

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

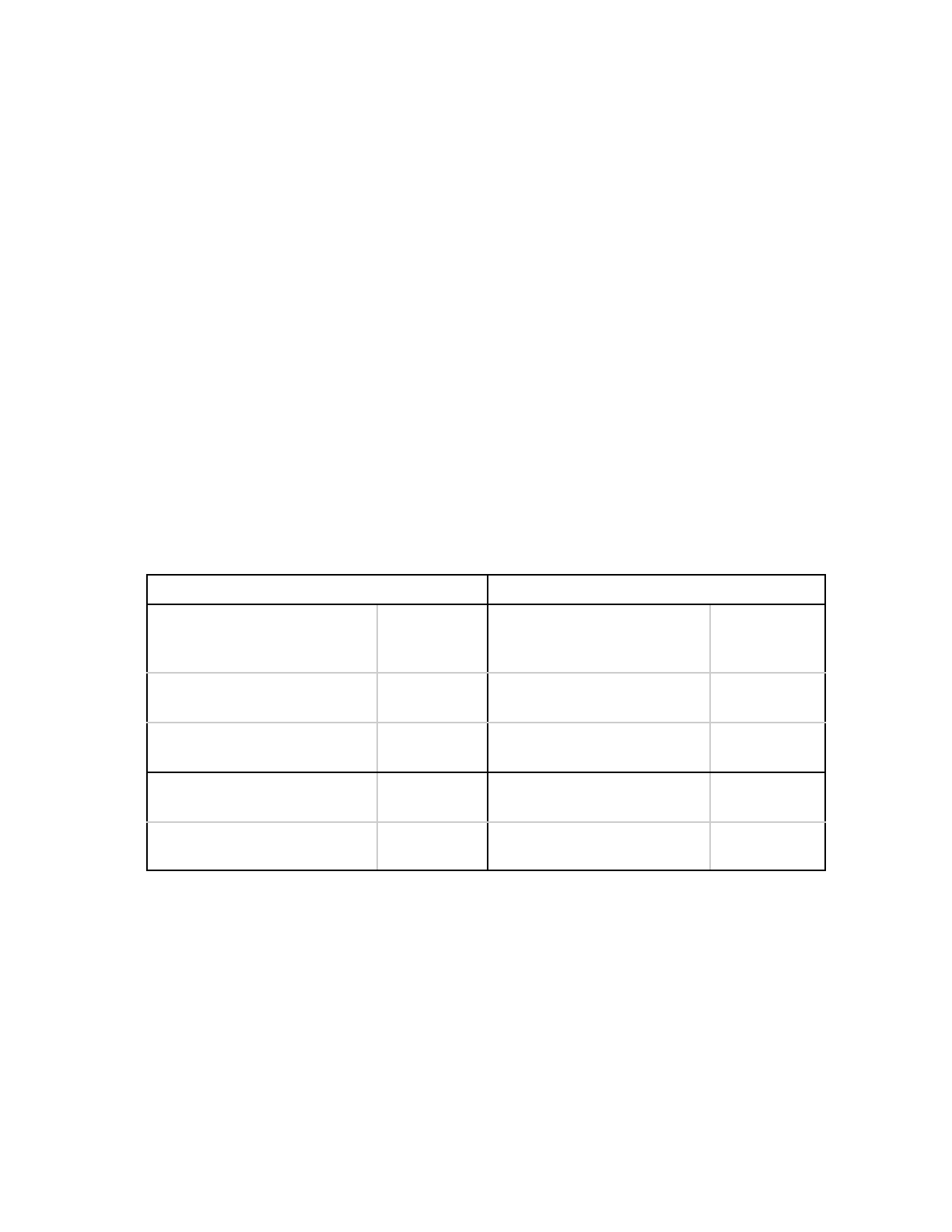

Table 1: The Population of People in Texas with Convictions

Estimated Number of People with

Convictions

4.8M

% Male

85%

Top Convictions - Felonies

poss cs pg 1 <1g (11.4%), DWI 3rd

or more (4.2%), burglary (3.7%)

Top Convictions - Misdemeanors

poss marij <2oz (8.3%), DWI

(5.6%), assault (3.7%)

Avg Years since last Conviction

12.6 (median = 11)

Average Age at First Conviction

28 (median =27)

Average Current Age of People with

Convictions

45

White and Latinx % (share in pop =

82%)

69%

Black % (share in pop = 13%)

31%

Asian % (share in pop = 5%)

1%

Source: Authors’ analysis based on the Texas CCH database.

age at first conviction is 28, the average current age of people in the sample is 45. On average,

the last conviction of each person was 12.6 years ago. From an earnings perspective this implies

that the average age of people who live with convictions in Texas overlaps with the years in

which workers typically hit their peak earnings.

95

Previous research finds that the racial disparities in Texas's criminal justice system are

significant. For example, although Black people account for 13% of the state population,

96

they

make up 33% of the Texas prison population.

97

In contrast, white people make up 44% of the

state population but account for just 33% of the prison population.

98

Thus, as of 2020, Black

98

Id.

97

Incarceration Trends in Texas, Vᴇʀᴀ Iɴsᴛɪᴛᴜᴛᴇ ᴏғ Jᴜsᴛɪᴄᴇ, (December 2019),

https://www.vera.org/downloads/pdfdownloads/state-incarceration-trends-texas.pdf.

96

Ashley Nellis, The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in State Prisons, Tʜᴇ Sᴇɴᴛᴇɴᴄɪɴɢ Pʀᴏᴊᴇᴄᴛ.

(October 13, 2021),

https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/ at 7.

95

Julia Carpenter, Millennials’ High-Earning Years Are Here, but It Doesn’t Feel That Way, Tʜᴇ Wᴀʟʟ Sᴛʀᴇᴇᴛ

Jᴏᴜʀɴᴀʟ, (August 12, 2021),

https://www.wsj.com/articles/millennials-high-earning-years-are-here-but-it-doesnt-feel-that-way-11628769603

(indicating, based on figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, that workers typically experience peak earnings

“between the ages of 35 and 54”).

16

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

people are 3.4 times more likely to be in prison than white people in Texas.

99

In contrast, Latinx

and Asian people are underrepresented in the prison population relative to their representation in

the population in general.

100

The data we analyzed, from the Texas Department of Public Safety, suggests similar

disparities in the breakdown of felony and misdemeanor convictions by race. For instance, even

though Black people make up just 13% of Texas's population, we find that Black people make up

30% of people with misdemeanor convictions and 31% of people with felony convictions in our

database. Whites and Asians appear to be underrepresented in felony and misdemeanor

convictions relative to their representation in the population in general. (Table 1)

B. The Texas Population That Could Benefit from License Restoration Relief

In contrast to the population of people with criminal records, less is known about the

demographic characteristics of people with suspended licenses. The populations are distinct,

however, as driver’s license suspensions are administrative penalties that, in Texas, generally

follow non-compliance with court-ordered fines and fees or requests to appear.

101

This means that

license suspensions often impact people who haven’t committed serious crimes,

102

or even been

accused of them.

Other studies have considered license suspension programs in Texas, North Carolina, and

New Jersey. Though the details of each suspension program are unique, the available evidence

suggests that individuals with suspended licenses tend to draw disproportionately from

low-income, urban communities and particularly harm the Black community.

Carnegie et al.’s study of New Jersey drivers from 2007 reports that “only 16.5 percent of

New Jersey licensed drivers reside in lower income zip codes, while 43 percent of all suspended

drivers live there.”

103

A later study by Joyce et al.

104

of all suspended licenses in New Jersey from

2004 to 2018 found that the median household income for people with non-driving related

suspensions was about $78,000,

105

which is about $14,000 lower than the median household

105

Quick Facts: New Jersey, Uɴɪᴛᴇᴅ Sᴛᴀᴛᴇs Cᴇɴsᴜs Bᴜʀᴇᴀᴜ, (last visited January 23, 2022),

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/NJ/SBO001212.

104

Nina R. Joyce et al., Individual and Geographic Variation in Driver’s License Suspensions: Evidence of

Disparities by Race, Ethnicity, and Income, 19 Jᴏᴜʀɴᴀʟ ᴏғ Tʀᴀɴsᴘᴏʀᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Hᴇᴀʟᴛʜ 1, 6 (2020).

103

Jon A. Carnegie et al., Driver’s License Suspensions, Impacts and Fairness Study, Nᴇᴡ Jᴇʀsᴇʏ Dᴇᴘᴀʀᴛᴍᴇɴᴛ ᴏғ

Tʀᴀɴsᴘᴏʀᴛᴀᴛɪᴏɴ, 66 (August 2007).

102

Justin Wm. Moyer, More than 7 million people may have lost driver’s licenses because of traffic debt,

Wᴀsʜɪɴɢᴛᴏɴ Pᴏsᴛ (May 19, 2018),

https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/public-safety/more-than-7-million-people-may-have-lost-drivers-licenses-be

cause-of-traffic-debt/2018/05/19/97678c08-5785-11e8-b656-a5f8c2a9295d_story.html (noting that “[d]river’s

license suspensions were criticized by anti-poverty advocates after a 2015 federal investigation, focused on

Ferguson, Mo., revealed that law enforcement used fines to raise revenue for state and local governments”).

101

100

See Table 1 for a snapshot of the Texas criminal population, by race.

99

Ashley Nellis, The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in State Prisons, Tʜᴇ Sᴇɴᴛᴇɴᴄɪɴɢ Pʀᴏᴊᴇᴄᴛ, 21

(October 13, 2021),

https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/.

17

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

income of $82,000 in 2019.

106

In contrast, the median household income for people who did not

have suspensions was nearly $105,000, about $23,000 above New Jersey’s median household

income.

107

Although estimates about the average or median income of people with suspended

licenses is unavailable for Texas, researchers for the Texas Fair Defense Project and Texas

Appleseed found a negative correlation between the number of license suspensions and the

household income in both Houston

108

and Dallas: “as zip code income increased, the number of

holds decreased.”

109

Both studies from New Jersey find people with suspended licenses are disproportionately

from urban areas. Carnegie et al. note that “[a]lthough only 43 percent of New Jersey licensed

drivers reside in urban areas, 63 percent of suspended drivers live there.”

110

More recent research

similarly reports that 4% of people who had any non-driving related suspensions lived in rural

areas, compared to 5.7% of people with no suspension.

111

Racial disparities among drivers with suspended licenses are significant. The Texas

studies referred to earlier, for example, find that in Dallas, Black people account for only 11% of

the driving population and yet account for 28.6% of people who cannot get their licenses

renewed due to OmniBase holds.

112

A similar trend is present in Houston, where Black people

make up only 22% of the city population, but comprise 40% of the people with OmniBase

license holds from the Houston Municipal Court.

113

Couzier and Garrett’s study of suspensions in

North Carolina finds that Black people make up 21% of drivers and account for 50.5% of license

113

Driven by Debt Houston, Tᴇxᴀs Fᴀɪʀ Dᴇғᴇɴsᴇ Pʀᴏᴊᴇᴄᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Tᴇxᴀs Aᴘᴘʟᴇsᴇᴇᴅ, 5 (July 2020),

https://www.texasappleseed.org/sites/default/files/DrivenByDebt-Houston-July2020.pdf.

112

Driven by Debt Dallas, Tᴇxᴀs Fᴀɪʀ Dᴇғᴇɴsᴇ Pʀᴏᴊᴇᴄᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Tᴇxᴀs Aᴘᴘʟᴇsᴇᴇᴅ, 6 (November 2019),

https://www.texasappleseed.org/sites/default/files/Driven%20By%20Debt%20Dallas.pdf.

111

Nina R. Joyce et al., Individual and Geographic Variation in Driver’s License Suspensions: Evidence of

Disparities by Race, Ethnicity, and Income, 19 Jᴏᴜʀɴᴀʟ ᴏғ Tʀᴀɴsᴘᴏʀᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Hᴇᴀʟᴛʜ 1, 6 (2020). (also finding that

6.7% of people with driving-related suspensions lived in rural areas)

110

Jon A. Carnegie et al., Driver’s License Suspensions, Impacts and Fairness Study, Nᴇᴡ Jᴇʀsᴇʏ Dᴇᴘᴀʀᴛᴍᴇɴᴛ ᴏғ

Tʀᴀɴsᴘᴏʀᴛᴀᴛɪᴏɴ, 66 (August 2007).

109

Driven by Debt Dallas, Tᴇxᴀs Fᴀɪʀ Dᴇғᴇɴsᴇ Pʀᴏᴊᴇᴄᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Tᴇxᴀs Aᴘᴘʟᴇsᴇᴇᴅ, 5 (November 2019),

https://www.texasappleseed.org/sites/default/files/Driven%20By%20Debt%20Dallas.pdf and Driven by Debt

Houston, Tᴇxᴀs Fᴀɪʀ Dᴇғᴇɴsᴇ Pʀᴏᴊᴇᴄᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Tᴇxᴀs Aᴘᴘʟᴇsᴇᴇᴅ, 4 (July 2020),

https://www.texasappleseed.org/sites/default/files/DrivenByDebt-Houston-July2020.pdf.

108

For more specific data on Houston, see Driven by Debt Houston, Tᴇxᴀs Fᴀɪʀ Dᴇғᴇɴsᴇ Pʀᴏᴊᴇᴄᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Tᴇxᴀs

Aᴘᴘʟᴇsᴇᴇᴅ, 5 (July 2020), https://www.texasappleseed.org/sites/default/files/DrivenByDebt-Houston-July2020.pdf

(“The zip code with the most holds per resident is 77026, an area in Northeast Houston covering the Kashmere

Gardens neighborhood, with 344 holds per every 1,000 residents. This zip code has more than one third of its

residents living below the poverty level and a majority of its residents (52%) are black. The median income is over

$20,000 less than the citywide median income. Profiles of other heavily affected zip codes are similar. The ten zip

codes with the highest rates of holds all have people living in poverty at higher rates than the city’s overall poverty

rate and most have median incomes below the city’s median income. Six of these ten zip codes have a population

that is more than 50% people of color).

107

Nina R. Joyce et al., Individual and Geographic Variation in Driver’s License Suspensions: Evidence of

Disparities by Race, Ethnicity, and Income, 19 Jᴏᴜʀɴᴀʟ ᴏғ Tʀᴀɴsᴘᴏʀᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Hᴇᴀʟᴛʜ 1, 6 (2020).

106

Jon A. Carnegie et al., Driver’s License Suspensions, Impacts and Fairness Study, Nᴇᴡ Jᴇʀsᴇʏ Dᴇᴘᴀʀᴛᴍᴇɴᴛ ᴏғ

Tʀᴀɴsᴘᴏʀᴛᴀᴛɪᴏɴ, 66 (August 2007).

18

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

suspensions, whereas white people account for 65% of drivers and 36.3% of license

suspensions.

114

Insofar as lost earnings due to suspended licenses is concerned, it is also worthwhile

considering the age of people with a suspended license and the average number of years their

license was suspended. Crozier and Garrett’s North Carolina study finds that the average age of

people at the time of license suspension was 28 years to 29 years, and the average length of hold

ranges from five to ten years.

115

Joyce et al.’s study of all New Jersey drivers with a suspended

license from 2004 to 2018 documented an average driver age of 39.4. Most relevant for our

purposes, the reports by the Texas Fair Defense Project and Texas Appleseed report an average

hold length of five years and seven months based on 2018 data acquired from the Department of

Public Safety. A summary of this information is available in Table A.

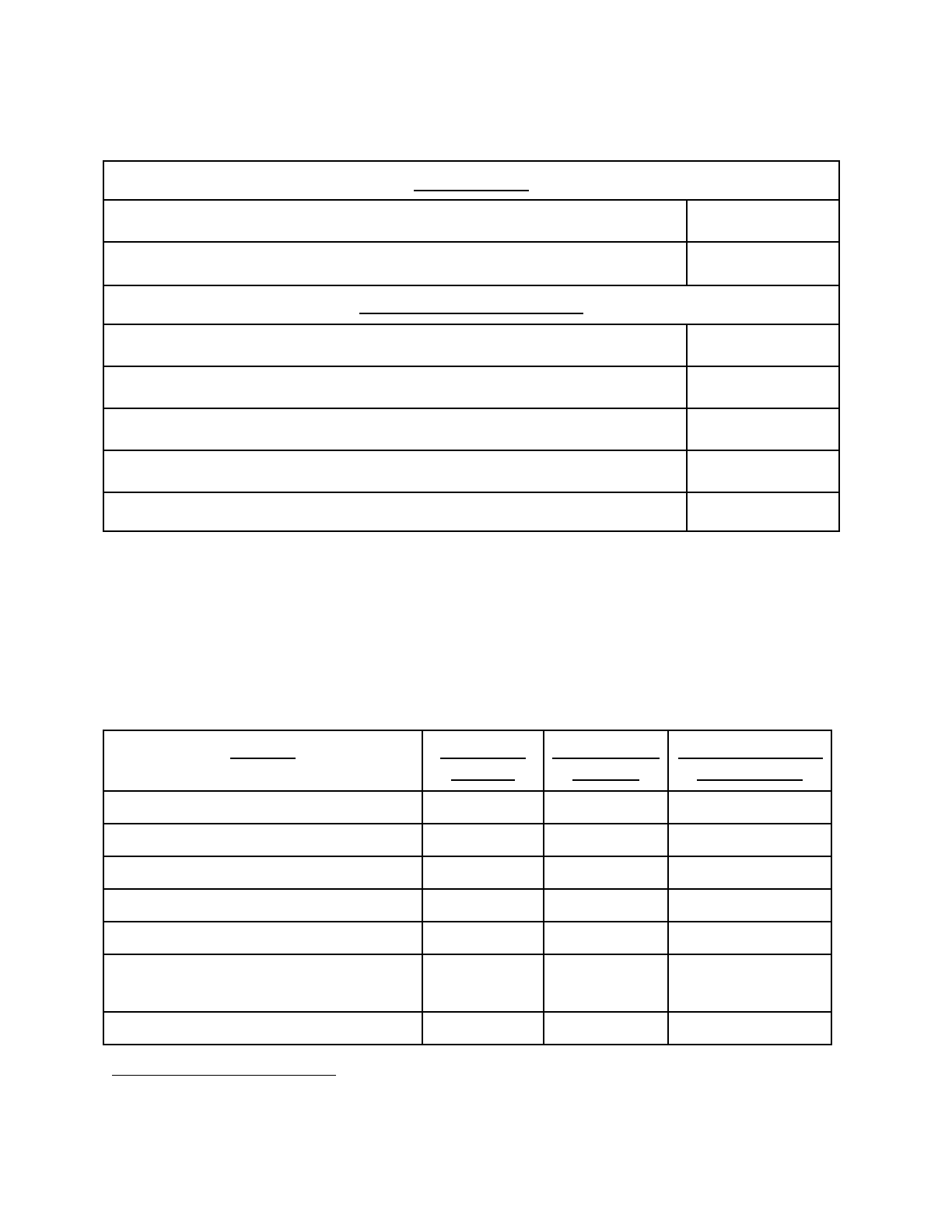

Table A: Demographic Information About Population With Suspended Driver’s Licenses

Study

Jurisdiction

Age

Average Length of

Hold

Source of

Estimates

Texas Fair Defense Project

and Texas Appleseed

(2019 and 2020)

Dallas and

Houston

– –

5 years and 7 months

(statewide estimate

from 2018 DPS data)

Pages 5-6

Joyce et al. (2020)

New Jersey

39.4 (mean age of

people with any

non-driving related

suspension)

– –

Table 1

Crouzier and Garrett

(2020)

North

Carolina

28.67 (median age at

time of offense)

10.1 years (median)

Table 2

C. Sizing Texas’s Second Chance Sealing Gap

115

Driven by Debt Dallas, Tᴇxᴀs Fᴀɪʀ Dᴇғᴇɴsᴇ Pʀᴏᴊᴇᴄᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Tᴇxᴀs Aᴘᴘʟᴇsᴇᴇᴅ, 5-6 (November 2019),

https://www.texasappleseed.org/sites/default/files/Driven%20By%20Debt%20Dallas.pdf; Driven by Debt Houston,

Tᴇxᴀs Fᴀɪʀ Dᴇғᴇɴsᴇ Pʀᴏᴊᴇᴄᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Tᴇxᴀs Aᴘᴘʟᴇsᴇᴇᴅ, 4-5 (July 2020),

https://www.texasappleseed.org/sites/default/files/DrivenByDebt-Houston-July2020.pdf; William E. Couzier &

Brandon L. Garrett, Driven to Failure: An Empirical Analysis of Driver’s License Suspension in North Carolina, 69

Dᴜᴋᴇ L.J. 1585, 1607 (2020); Nina R. Joyce et al., Individual and Geographic Variation in Driver’s License

Suspensions: Evidence of Disparities by Race, Ethnicity, and Income, 19 Jᴏᴜʀɴᴀʟ ᴏғ Tʀᴀɴsᴘᴏʀᴛ ᴀɴᴅ Hᴇᴀʟᴛʜ 1, 6

(2020).

114

William E. Couzier & Brandon L. Garrett, Driven to Failure: An Empirical Analysis of Driver’s License

Suspension in North Carolina, 69 Dᴜᴋᴇ L.J. 1585, 1607-1608 (2020).

19

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

Having provided an overview of Texas’s criminal population, we begin by calculating the

second chance sealing gap — the difference between eligibility and delivery of sealing relief to

people with criminal convictions. We use the gap-sizing methodology described in Chien,

America's Paper Prisons: The Second Chance Gap, Michigan Law Review (2020) to determine

several numbers: (1) the current gap — the number and share of individuals with records that

could qualify for relief, (2) the uptake gap — the share of people eligible for a given second

chance that have obtained it,

116

and (3) based on the same data used to calculate the current and

uptake gaps, how many years, at current rates, it would take to clear the existing backlog.

First, we ascertained and modeled Texas’s OND law. Next, we applied the model of the

laws to a sample of criminal histories obtained from the state to identify the number of

individuals eligible for a given second chance. Once we had estimated the number of people

eligible for a given second chance, we calculated the “current gap,” the uptake rate, and the pace

of record relief using the following steps. To estimate the current gap, we divided the number of

people eligible for a given second chance by the number of people in our sample. To estimate the

population eligible for relief, we multiplied the current gap by the total population, which was

estimated using state data. Next, using historical data obtained from the state, we calculated the

estimated relief granted over the past five to ten years by adding the number of second chances

granted to the product of (i) the number of second chances granted in the earliest year of data and

(ii) the number of years left to reach five or ten years of data (whichever was closest to the actual

number of years of data the state provided). Then, to calculate the uptake rate, we divided the

estimated historical relief rate by the number of people eligible for relief plus the estimated

historical relief rate. After calculating the current gap and the uptake gap, we estimated the

number of years it would take to clear the backlog by dividing the population eligible for relief

by the number of people who were granted a second chance in the most recent full year of data.

There are several weaknesses with our methodology. First, we do not account for

eligibility requirements related to fines and fees due to a lack of data, making our eligibility

estimates generous. In the other direction, we also do not include eligibility for expungements of

non-convictions, which depress, potentially dramatically, our estimates of who falls into the

records relief gap. Second, the underlying criminal history provided by the state at times was

missing sentence expiration dates. When that data was missing, we inferred expiration dates

based on data where expiration dates were present.

117

Finally, as detailed in the appendix, certain

eligibility provisions contained ambiguities that we were unable to resolve despite multiple

consultations with local criminal law experts. These challenges introduce inaccuracies that cause

our estimates to be both over- and under-inclusive.

Table 2: Estimated Eligibility and Uptake of Texas Record Sealing and Drivers Restoration

Order of Non-Disclosure

Occupational Driver’s

117

Based on our analysis, we assumed expiration date = sentence_start_date + 2.9 years for misdemeanors and 3.2

years for felonies. Additional details are available in the Appendix.

116

Colleen Chien, America’s Paper Prisons: The Second Chance Gaps, 119 Mɪᴄʜ. L. Rᴇᴠ. 519 (2020) at 542-543.

20

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920

(Sealing)

License (Restoration)

Total Population (Eligible + Ineligible)

4,826,860

N/A

Population Eligible for Relief

676,845

438,000

Population Eligible for a Clean Record (no

Conviction)

58,501

N/A

Relief Granted in Last Available Year

2,650 (2019)

16,350 (2019)

Estimated Relief Granted

36,409 (10 years)

87,027 (5 years)

Uptake Rate (estimated share of people eligible

for a given second chance that have obtained it)

~5%

~17%

Years It Would Take to Clear the Backlog

255

27

Current Gap (estimated share of all people with

records that are eligible for relief)

14%

N/A

Based on taking the steps described above,

118

we estimate that around 677,000 people

with misdemeanor convictions or deferred adjudications are eligible for sealing relief under

Texas Gov. Code Chapter 411, and 59,000 for a clean record. We further find that 18,593 people

had their records sealed between fiscal years 2014 and 2019. Based on this, we project that, at

most, 36,000 people sealed their records over the past ten years. Combining these historical

figures with our eligibility calculations, we estimate that ~5% of people eligible for relief have

received it, leaving 95% of people in the “Texas Second Chance Sealing Gap.” Based on

administrative data, 2,650 people sealed their records in the last year of available data (2019).

119

At this rate, it would take 255 years to clear the sealing backlog. The profile of individuals that

could get a “cleaner” or “completely cleaned” record is similar to that of the average profile of a

person with a conviction, except that the average years since the last conviction is 17 and 19

years, respectively.

120

D. Sizing Texas’s Second Chance Driver’s License Restoration Gap

We applied a similar “second chance gap” approach to quantifying the number of people

in Texas who appear eligible for but have not received an occupational driver’s license

“restoration” based on Texas Transportation Code Section 521 Subchapter L. Doing so requires

an understanding of how driver’s licenses are suspended in Texas in the first place. Practitioners

have generally described two main, non-driving-related causes of a license suspension: (i) failure

120

See Appendix

119

Data was acquired from the Texas Department of Public Safety. See Appendix E for a breakdown of sealings by

year for every year of data the Department of Public Safety gave us.

118

Further details are provided in the Appendix.

21

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4065920