National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

National Emergency

Communications Plan

PRELIMINARY DRAFT v1.02

National Emergency

Communications Plan

PRELIMINARY DRAFT v1.02

National Emergency

Communications Plan

July 2008

Rev. Aug 7, 2008

National Emergency Communications Plan

July

2008

Message from the Secretary

Numerous after-action reports from major incidents throughout the history of emergency

management in our Nation have cited communication difficulties among the many

responding agencies as a major failing and challenge to policymakers. Congress and the

Administration have recognized that successful response to a future major

incident-

either a terrorist attack or natural disaster-would require a coordinated, "interoperable"

response by the Nation's public safety, public health, and emergency management

community, both public and private, at the Federal, State, tribal, Territorial, regional, and

local levels.

Recognizing the need for an overarching strategy to help coordinate and guide such

efforts, Congress directed the Department of Homeland Security to develop the first

National Emergency Communications Plan (NECP).

The purpose of the NECP is to

promote the ability of emergency response providers and relevant government officials to

continue to communicate in the event of natural disasters, acts of terrorism, and other

man-made disasters and to ensure, accelerate, and attain interoperable emergency

communications nationwide.

Natural disasters and acts of terrorism have shown that there is no simple solution-or

"silver bullet"-to solve the communications problems that still plague law enforcement,

firefighting, rescue, and emergency medical personnel.

To strengthen emergency communications capabilities nationwide, the Plan focuses on

technology, coordination, governance, planning, usage, training and exercises at all levels

of government. This approach recognizes that communications operability is a critical

building block for interoperability; emergency response officials first must be able to

establish communications within their own agency before they can interoperate with

neighboring jurisdictions and other agencies.

The NECP seeks to build on the substantial progress that has been made over the last

several years. Among the key developments at the Federal, State, regional, and local

levels are:

Most Federal programs that support emergency communications have been

consolidated within a single agency-the

Department of Homeland Security-to

improve the alignment, integration, and coordination of the Federal mission.

All

56

States and U.S. Territories have developed

Statewide Communication

Interoperability Plans

(SCIP) that identify near- and long-term initiatives for

improving communications interoperability.

The Nation's

75

largest urban and metropolitan areas

maintain policies for

interoperable communications.

National Emernencv Communications Plan

Julv

2008

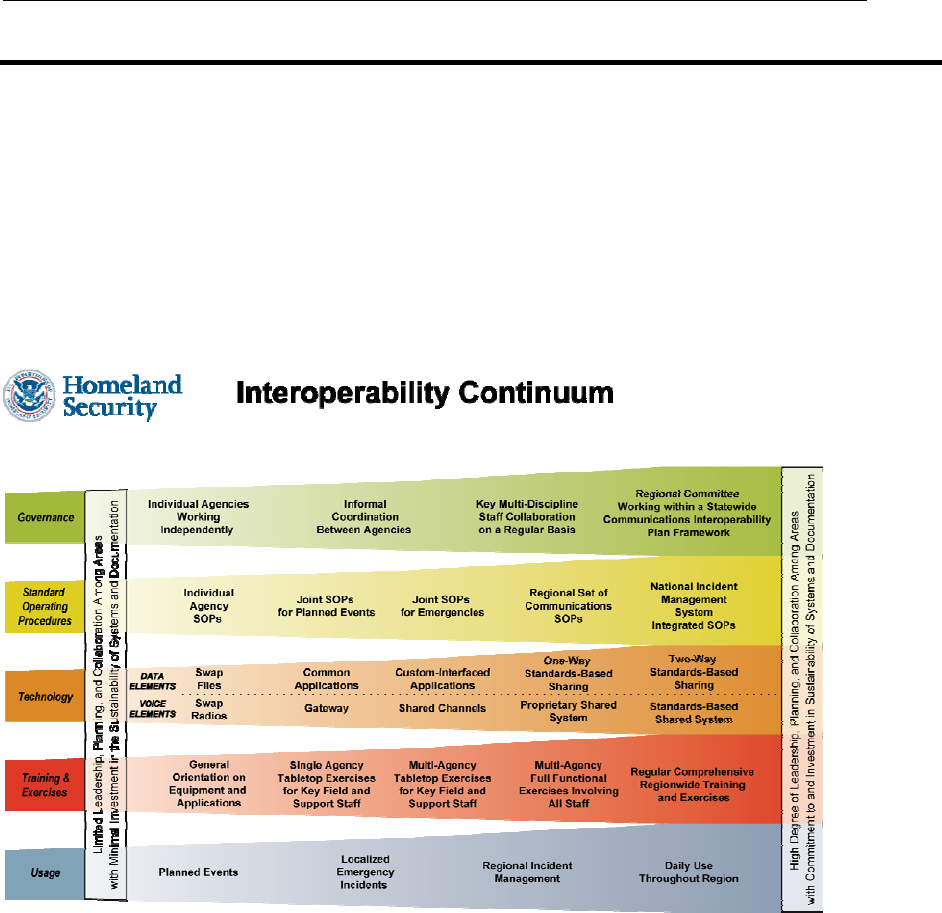

The

SAFECOM Interoperability Continuum

is widely accepted and used by the

emergency response community to address critical elements for planning and

implementing interoperability solutions. These elements include governance,

standard operating procedures, technology, training and exercises, and usage of

interoperable communications.

The DHS Federal Emergency Management Agency

(FEMA)

is establishing

Regional Emergency Communications Coordination

(RECC) Working Groups

in each of the

10

FEMA regions to coordinate multi-state efforts and measure

progress on improving the survivability, sustainability, and interoperability of

communications at the regional level.

In

developing the NECP, DHS worked closely with stakeholders from all levels of

government to ensure that their priorities and activities were addressed. The Department

will continue to coordinate with Federal, State, local, and tribal governments, and the

private sector, to ensure that the NECP is implemented successfully.

Ultimately, the NECP's goals cannot be achieved without the support and dedication of

the emergency response community that was instrumental in crafting it.

I

ask everyone

within the emergency response community to take ownership of the

NECP's initiatives

and actions and to dedicate themselves to meeting the key benchmarks. Working

together, we can achieve our vision:

Emergency responders can communicate-

as

needed, on demand, and

as

authorized;

at all levels of government; and

across all disciplines.

Michael Chertoff

P+

Secretary of Homeland Security

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

Table of Contents

Executive Summary....................................................................................................ES-1

1. Introduction....................................................................................................................

1.1 Purpose of the National Emergency Communications Plan............................. 1

1.2 Scope of the National Emergency Communications Plan................................. 2

1.3 Organization of the NECP................................................................................... 5

2. Defining the Future State of Emergency Communications.................................... 6

2.1 Vision...................................................................................................................... 6

2.2 Goals....................................................................................................................... 6

2.3 Capabilities Needed .............................................................................................. 7

3. Achieving the Future State of Emergency Communications.................................. 9

Objective 1: Formal Governance Structures and Clear Leadership Roles.. 11

Objective 2: Coordinated Federal Activities.................................................... 16

Objective 3: Common Planning and Operational Protocols ......................... 20

Objective 4: Standards and Emerging Communication Technologies......... 24

Objective 5: Emergency Responder Skills and Capabilities.......................... 28

Objective 6: System Life-Cycle Planning ........................................................ 31

Objective 7: Disaster Communications Capabilities...................................... 34

4. Implementing and Measuring Achievement of the NECP..................................... 39

5. Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 41

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

Executive Summary

Every day in cities and towns across the Nation, emergency response personnel respond

to incidents of varying scope and magnitude. Their ability to communicate in real time is

critical to establishing command and control at the scene of an emergency, to maintaining

event situational awareness, and to operating overall within a broad range of incidents.

However, as numerous after-action reports and national assessments have revealed, there

are still communications deficiencies that affect the ability of responders to manage

routine incidents and support responses to natural disasters, acts of terrorism, and other

incidents.

1

Recognizing the need for an overarching emergency communications strategy to address

these shortfalls, Congress directed the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Office

of Emergency Communications (OEC) to develop the first National Emergency

Communications Plan (NECP). Title XVIII of the Homeland Security Act of 2002

(6 United States Code 101 et seq.), as amended, calls for the NECP to be developed in

coordination with stakeholders from all levels of government and from the private sector.

In response, DHS worked with stakeholders from Federal, State, local, and tribal agencies

to develop the NECP—a strategic plan that establishes a national vision for the future

state of emergency communications. The desired future state is that emergency

responders can communicate:

As needed, on demand, and as authorized

At all levels of government

Across all disciplines

To measure progress toward this vision, three strategic goals were established:

Goal 1—By 2010, 90 percent of all high-risk urban areas designated within the Urban

Areas Security Initiative (UASI)

2

are able to demonstrate response-level

emergency communications

3

within one hour for routine events involving

multiple jurisdictions and agencies.

Goal 2—By 2011, 75 percent of non-UASI jurisdictions are able to demonstrate

response-level emergency communications within one hour for routine

events involving multiple jurisdictions and agencies.

Goal 3—By 2013, 75 percent of all jurisdictions are able to demonstrate response-

level emergency communications within three hours, in the event of a

significant incident as outlined in national planning scenarios.

1

Examples include The Federal Response to Hurricane Katrina: Lessons Learned, February 2006; The 9-11

Commission Report, July 2004; and The Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the

Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina, February 2006.

2

As identified in FY08 Homeland Security Grant Program or on the FEMA Grants website:

http://www.fema.gov/pdf/government/grant/uasi/fy08_uasi_guidance.pdf.

3

Response-level emergency communication refers to the capacity of individuals with primary operational leadership

responsibility to manage resources and make timely decisions during an incident involving multiple agencies,

without technical or procedural communications impediments.

ES-1

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

To realize this national vision and meet these goals, the NECP established the following

seven objectives for improving emergency communications for the Nation’s Federal,

State, local, and tribal emergency responders:

1. Formal decision-making structures and clearly defined leadership roles

coordinate emergency communications capabilities.

2. Federal emergency communications programs and initiatives are collaborative

across agencies and aligned to achieve national goals.

3. Emergency responders employ common planning and operational protocols to

effectively use their resources and personnel.

4. Emerging technologies are integrated with current emergency communications

capabilities through standards implementation, research and development, and

testing and evaluation.

5. Emergency responders have shared approaches to training and exercises,

improved technical expertise, and enhanced response capabilities.

6. All levels of government drive long-term advancements in emergency

communications through integrated strategic planning procedures, appropriate

resource allocations, and public-private partnerships.

7. The Nation has integrated preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery

capabilities to communicate during significant events.

The NECP also provides recommended initiatives and milestones to guide emergency

response providers and relevant government officials in making measurable

improvements in emergency communications capabilities. The NECP recommendations

help to guide, but do not dictate, the distribution of homeland security funds to improve

emergency communications at the Federal, State, and local levels, and to support the

NECP implementation.

Communications investments are among the most significant, substantial, and long-

lasting capital investments that agencies make; in addition, technological innovations for

emergency communications are constantly evolving at a rapid pace. With these realities

in mind, DHS recognizes that the emergency response community will realize this

national vision in stages, as agencies invest in new communications systems and as new

technologies emerge.

There is no simple solution, or “silver bullet,” for solving emergency communications

challenges, and consequently DHS’ approach to the NECP involves making

improvements at all levels of government, in technology, coordination and governance,

planning, usage, and training and exercises. This approach also recognizes that

communications operability is a critical building block for interoperability; emergency

response officials must first establish reliable communications within their own agency

before they can interoperate with neighboring jurisdictions and other agencies.

Finally, DHS acknowledges that the Nation does not have unlimited resources to address

deficiencies in emergency communications. Consequently, the NECP will be used to

identify and prioritize investments to move the Nation toward this vision. As required by

Congress, the NECP will be a living document subject to periodic review and updates by

DHS in coordination with stakeholders. Future iterations will be revised based on

progress made toward achieving the NECP’s goals, on variations in national priorities,

and on lessons learned from after-action reports.

ES-2

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

1. Introduction

The ability of emergency responders to effectively communicate is paramount to the

safety and security of our Nation. During the last three decades, the Nation has witnessed

how inadequate emergency communications capabilities can adversely affect response

and recovery efforts. Locally, agencies developed ad hoc solutions to overcome these

challenges. The issue of inadequate coordination of emergency communications received

national attention in the aftermath of the January 1982 passenger jet crash into the

14

th

Street Bridge (and, subsequently, the Potomac River) near downtown Washington,

DC. The inability of multiple jurisdictions to coordinate a response to the Air Florida

crash began to drive regional collaboration. More recently, the terrorist attacks of

September 11, Hurricane Katrina, and other natural and man-made disasters have

demonstrated how emergency communications capabilities—in particular the lack of

those capabilities—impact emergency responders, public health, national and economic

security, and the ability of government leaders to maintain order and perform essential

functions.

4

During each of these events, the lack of coordinated emergency communications

solutions and protocols among the responding agencies hindered response and recovery

efforts. These events raised awareness of the issue among public policymakers and

highlighted the critical role emergency communications plays in incident response.

These events also prompted numerous national studies and assessments on the state of

emergency communications, which in turn has helped DHS to formulate a unified

approach for addressing emergency communications.

5

1.1 Purpose of the National Emergency Communications Plan

The Homeland Security Act of 2002, as

amended in 2006, mandated the creation of an

overarching strategy to address emergency

communications shortfalls. In addition, the

emergency response community has sought

national guidance to support a more integrated

coordination of emergency communications

priorities and investments.

• Set national goals and priorities

for addressing deficiencies in the

Nation’s emergency

communications posture

• Provide recommendations and

milestones for emergency

response providers, relevant

government officials, and

Congress to improve emergency

communications capabilities

4

“Hurricane Katrina was the most destructive natural disaster in U.S. history. The storm crippled thirty-eight 911-call

centers, disrupting local emergency services, and knocked out more than 3 million customer phone lines in

Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. Broadcast communications were likewise severely affected, as 50 percent of

area radio stations and 44 percent of area television stations went off the air.” White House Report, The Federal

Response to Katrina: Lessons Learned, February 2006.

5

Such as the Final Report of the National Commission of Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, December 2001;

the White House Report, The Federal Response to Katrina: Lessons Learned, February 2006; and the Independent

Panel Reviewing the Impact of Hurricane Katrina on Communications Networks—Report and Recommendations to

the Federal Communications Commission, June 12, 2006, all of which documented the numerous failures in

emergency communications among emergency responders, which affected their ability to effectively respond to

these incidents

.

1

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

As a result, Congress directed the DHS’ Office of Emergency Communications (OEC)

6

to develop a plan to:

• Identify the capabilities needed by emergency responders to ensure the availability

and interoperability of communications during emergencies, and identify obstacles

to the deployment of interoperable communications systems;

• Recommend both short- and long-term solutions for ensuring interoperability and

continuity of communications for emergency responders, including

recommendations for improving coordination among Federal, State, local, and tribal

governments;

• Set goals and timeframes for the deployment of interoperable emergency

communications systems, and recommend measures that emergency response

providers should employ to ensure the continued operation of communications

infrastructure;

• Set dates by which Federal agencies and State, local, and tribal governments expect

to achieve a baseline level of national interoperable communications, and establish

benchmarks to measure progress; and

• Guide the coordination of existing Federal emergency communications programs.

7

1.2 Scope of the National Emergency Communications Plan

The National Emergency Communications Plan (NECP) focuses on the emergency

communications needs of response personnel in every discipline, at every level of

government, and for the private sector and non-governmental organizations (NGO).

Emergency communications is defined as the ability of emergency responders to

exchange information via data, voice, and video as authorized, to complete their

missions. Emergency response agencies at all levels of government must have

interoperable and seamless communications to manage emergency response, establish

command and control, maintain situational awareness, and function under a common

operating picture, for a broad scale of incidents.

Emergency communications consists of three primary elements:

1. Operability—The ability of emergency responders to establish and sustain

communications in support of mission operations.

2. Interoperability—The ability of emergency responders to communicate among

jurisdictions, disciplines, and levels of government, using a variety of frequency

bands, as needed and as authorized. System operability is required for system

interoperability.

3. Continuity of Communications—The ability of emergency response agencies to

maintain communications in the event of damage to or destruction of the primary

infrastructure.

6

The OEC supports the Secretary of Homeland Security in developing, implementing, and coordinating interoperable

and operable communications for the emergency response community at all levels of government. The OEC was

directed by Title XVIII of the Homeland Security Act of 2002, as amended, to lead the development of a National

Emergency Communications Plan.

7

Appendix 4 provides more detailed information on DHS programs supporting emergency communications.

2

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

1.2.1 Approach to Developing the NECP

The majority of emergency incidents occur at the local level. Therefore, improving

emergency communications—specifically, operability, interoperability, and continuity of

communications—cannot be accomplished by the Federal Government alone. For this

reason, working through OEC, DHS used a stakeholder-driven approach to develop the

NECP, one that included representatives from the Federal, State, and local responder

communities as well as from the private sector.

8

Exhibit 1 lists the partnerships and

groups that provided input to the NECP.

Exhibit 1: Key Homeland Security and Emergency Communications Partnerships

Entity Roles and Responsibilities

SAFECOM

Executive Committee

(EC) and Emergency

Response Council

(ERC)

The SAFECOM EC serves as the leadership group of the ERC and as the

SAFECOM program’s primary resource to access public safety practitioners and

policymakers. The EC provides strategic leadership and guidance to the

SAFECOM program on emergency-responder user needs and builds

relationships with the ERC to leverage the ERC subject matter expertise. The

SAFECOM ERC is a vehicle to provide a broad base of input from the public

safety community on its user needs to the SAFECOM program. The ERC

provides a forum for individuals with specialized skills and common interests to

share best practices and lessons learned so that interested parties at all levels of

government can gain from one another’s experience. Emergency responders

and policymakers from Federal, State, local, and tribal governments compose

the SAFECOM EC and ERC.

Emergency

Communications

Preparedness Center

(ECPC)

The ECPC was created under the authority of Title XVIII of the Homeland

Security Act of 2002, as amended in 2006, to serve as the focal point and

clearinghouse for intergovernmental information on interoperable emergency

communications. The ECPC is an interdepartmental organization, currently

composed of 12 Federal departments and agencies, that assesses and

coordinates Federal emergency communications operability and interoperability

assurance efforts. The ECPC is the focal point for interagency emergency

communications efforts and seeks to minimize the duplication of similar activities

within the Federal Government. It also acts as an information clearinghouse to

promote operable and interoperable communications in an all-hazards

environment.

Federal Partnership

for Interoperable

Communications

(FPIC)

The FPIC is a coordinating body that focuses on technical and operational

matters within the Federal wireless communications community. Its mission is to

address Federal wireless communications interoperability by fostering

intergovernmental cooperation and by identifying and leveraging common

synergies. The FPIC represents more than 40 Federal entities; its membership

includes program managers of wireless systems, radio communications

managers, Information Technology (IT) and Land Mobile Radio (LMR)

specialists, and telecommunications engineers. State and local emergency

responders participate as advisory members.

Project 25 Interface

Committee (APIC)

As part of the Project 25 (P25) standards development process, the

Telecommunications Industry Association (TIA) developed the APIC to

resolve issues that arose during that process. The APIC is composed of private

sector representatives and emergency response officials and serves as a liaison

to facilitate user community and private sector relationships regarding the

evolution and use of P25 standards.

National Public

Safety

Telecommunications

Council (NPSTC)

The NPSTC is a federation of national public safety leadership organizations

dedicated to improving emergency response communications and

interoperability through collaborative leadership. The NPSTC is composed of

State and local public safety representatives. In addition, Federal, Canadian,

and other emergency communications partner organizations serve as liaisons to

the NPSTC.

8

Appendix 6 details the three-phased approach to develop the NECP that relied on stakeholder involvement.

3

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

Entity Roles and Responsibilities

National Security

Telecommunications

Advisory

Committee (NSTAC)

The NSTAC is composed of up to 30 private sector executives who represent

major communications and network service providers as well as IT, finance, and

aerospace companies. Through the National Communications System

(NCS), the NSTAC provides private sector-based analyses and

recommendations to the President and the Executive Branch on policy and

enhancements to national security and emergency preparedness (NS/EP)

communications.

Critical Infrastructure

Partnership Advisory

Council (CIPAC)

The CIPAC is a DHS program established to facilitate effective coordination

between government infrastructure protection programs and the infrastructure

protection activities of the owners and operators of critical infrastructure and key

resources. The CIPAC enables public and private sector representatives to

engage in candid, substantive discussions regarding the protection of the

Nation’s critical infrastructure.

The NECP has been designed to complement and support overarching homeland security

and emergency communications legislation, strategies, and initiatives. The NECP applies

guidance from these authorities, including key principles and priorities, to establish the

first national strategic plan that is focused exclusively on improving emergency

communications for emergency response providers nationwide. As demonstrated in

Exhibit 2 below, the NECP provides a critical link between national communications

priorities and strategic and tactical planning at the regional, State, and local levels.

Appendix 2 provides a comprehensive listing and explanation of these documents.

Exhibit 2: Key Homeland Security and Emergency Communications Authorities

NATIONAL

NATIONAL

LEGISLATION &

STRATEGIES

PREPAREDNESS/

INCIDENT

MANAGEMENT

POLICY & PLANNING

INITIATIVES

DIRECTIVES &

EXECUTIVE ORDERS

REGIONAL, STATE, LOCAL

REGIONAL, STATE, LOCAL

HSPDs(e.g., 5, 7, 8)

EOs

(e.g., 12406,3,

12472, 12656)

NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR

HOMELAND SECURITY

NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR

PHYSICAL PROTECTION OF CI/K

NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR

PHYSICAL PROTECTION OF CI/KA

HOMELAND SECURITY ACT

HOMELAND SECURITY ACT

NRF, SUPPORT

FUNCTION

OPERATIONAL

NIPP

NIPP

NATIONAL

PREPAREDNESS

GUIDELINES

NATIONAL

PREPAREDNESS

GUIDELINES

TICPS

TICPs

SCIPS

SCIPs

Regional Strategic

Planning

Regional Strategic

Planning

STRATEGIC

PREPAREDNESS/

COMMUNICATIONS

PLANNING

INITIATIVES

Hazard Mitigation

Hazard Mitigation

Emergenc

y

Operations Plans

Emergenc

y

Operations Plans

NIMS

HSPDs

(e.g., 5, 7, 8)

(e.g., 12046,

12472, 12656)

EOs

NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR

HOMELAND SECURITY

NECP

Communications-specific

4

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

1.3 Organization of the NECP

The NECP establishes a national vision for the desired future state of emergency

communications. It sets strategic goals, national objectives, and supporting initiatives to

drive the Nation toward that future state. The NECP also provides recommended

milestones to guide emergency response providers and relevant government officials as

they make measurable improvements to their emergency communications capabilities.

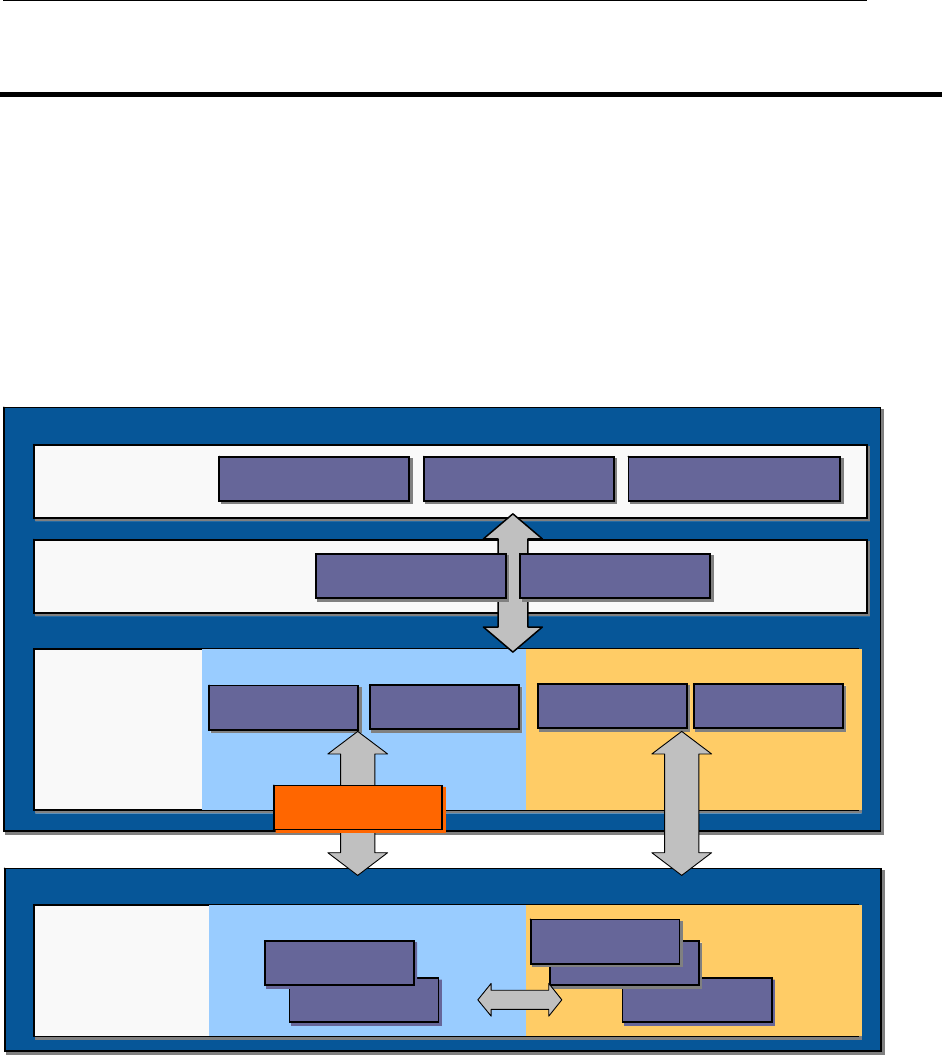

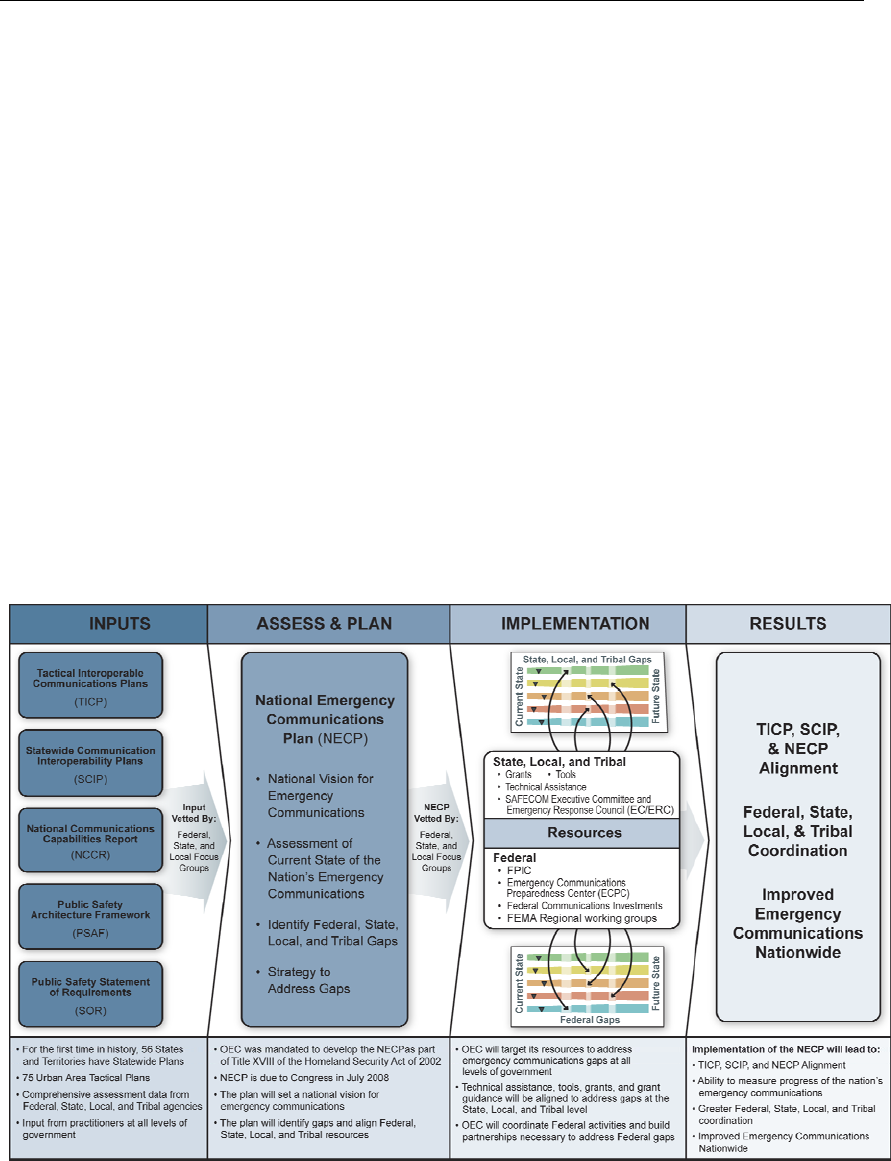

As illustrated in Exhibit 3, the NECP approach is based on three logical steps that inform

the organization of this document: 1) defining the future state of emergency

communications; 2) developing a strategy to achieve the future state; and 3)

implementing the future state and measuring how well it is being implemented.

Exhibit 3: NECP Approach and Organization

NECP Approach and Organization

Future State

Vision

Goals

Capabilities

Strategy

Objectives

Initiatives

Milestones

Implementation

Coordination

Measurement

Evaluation Framework

1.3.1 Defining the Future State of Emergency Communications

In this first step, DHS worked with stakeholders to develop an overall Vision statement

(Section 2.1) and established three high-level Goals (Section 2.2) that define the desired

future state of emergency communications. DHS then identified the emergency

communications Capabilities Needed (Section 2.3) for the emergency response

community to achieve the desired future state.

1.3.2 Developing a Strategy to Achieve the Future State

Based on the capabilities needed for the emergency response community to achieve the

desired future state, DHS developed seven Objectives (Section 3). Although all seven

objectives were designed to support the realization of the long-term vision, execution of

all initiatives and achievement of national milestones are not necessarily prerequisites for

achieving the three goals. DHS will continue to work with its stakeholders on the

implementation of the NECP initiatives and the attainment of these near-term goals. For

each objective, DHS developed Supporting Initiatives (Section 3), which are intended

to drive outcomes toward the future state. In crafting each initiative, DHS identified both

current emergency communications activities that affect the initiative and key gaps that

drive action in the initiative area. Finally, DHS identified Recommended National

Milestones (Section 3) that detail the timeline and outcomes of each initiative.

1.3.3 Implementing and Measuring Achievement of the Future State

In the final step, DHS provides guidance for implementing the NECP and

recommendations for measuring success (Section 4). These recommendations are based

on the legislative requirements for the NECP as outlined in Appendix 1.

5

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

2. Defining the Future State of Emergency Communications

The NECP outlines the future vision of emergency communications over the next five

years. In doing so, it establishes tangible goals by which success can be measured.

2.1 Vision

Vision

The NECP vision is to ensure operability,

interoperability, and continuity of

communications to allow emergency

responders to communicate as needed, on

demand, and as authorized at all levels of

government and across all disciplines.

Emergency response personnel

can communicate—

• As needed, on demand,

and as authorized

• At all levels of

government

• Across all disciplines

2.2 Goals

To work toward this desired future state, DHS defined a series of goals that establish a

minimum level of interoperable communications and dates by which Federal, State, local,

and tribal agencies are expected to achieve that minimum level. Although not

comprehensive, these goals provide an initial set of operational targets which OEC will

expand further through a process that engages Federal, State, and local governments, the

private sector, and emergency responders. Section 4.2 outlines how OEC plans to

measure the nationwide achievement of these goals.

If emergency responders train regularly and use emergency communications solutions

daily, they will be able to use emergency communications more effectively during major

incidents. Therefore, the first two goals focus on day-to-day response capabilities that

will inherently enhance emergency response capabilities.

Response-level emergency communications is the capacity of individuals with primary

operational leadership responsibility to manage resources and make timely decisions

during an incident involving multiple agencies, without technical or procedural

communications impediments.

9

In addition to communicating with first-level

subordinates in the field, an Operations Section Chief should be able to communicate up

the management chain to the incident command level (i.e., between the Operations

Section Chief and Incident Command).

10

During the course of incident response,

Incident Command/Unified Command may move off-scene, which may require

establishing communications between Incident Command and off-scene Emergency

Operations Centers (EOC), dispatch centers, and other support groups.

9

As defined in the National Incident Command System 200, Unit 2: Leadership and Management.

10

As defined in the National Incident Management System, FEMA 501/Draft August 2007, p.47.

6

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

NECP Goals

Goal 1—By 2010, 90 percent of all high-risk urban areas designated within the Urban

Areas Security Initiative (UASI)

11

are able to demonstrate response-level

emergency communications within one hour for routine events

12

involving

multiple jurisdictions

13

and agencies.

Goal 2—By 2011, 75 percent of non-UASI jurisdictions are able to demonstrate

response-level emergency communications within one hour for routine

events involving multiple jurisdictions and agencies.

Goal 3—By 2013, 75 percent of all jurisdictions are able to demonstrate response-

level emergency communications within three hours, in the event of a

significant event

14

as outlined in national planning scenarios.

The NECP identifies seven key objectives to move the Nation toward its overall vision.

Although all seven objectives are important to achieving all three goals, Objective 7

focuses primarily on enhancing the ability to communicate during a significant event as

outlined in Goal 3. Further, through OEC and the Federal Emergency Management

Agency’s (FEMA) Regional Emergency Communications Coordination Working Groups

(RECCWG), DHS will collaborate with State homeland security directors and State

interoperability coordinators to develop appropriate methodologies to measure progress

toward these goals in each State.

2.3 Capabilities Needed

Leveraging the findings from various sources of information, including analyses, from

Federal, State, local, and tribal governments on emergency communications, DHS

completed a comprehensive examination of emergency communications capabilities

across all levels of government and some private sector entities.

15

(A capability enables

the accomplishment of a mission or task.) Exhibit 4 summarizes the range of emergency

communications capabilities needed by emergency responders and maps those to the

SAFECOM Interoperability Continuum.

16

11

As identified in the FY08 Homeland Security Grant Program or on the FEMA Grants website:

http://www.fema.gov/pdf/government/grant/uasi/fy08_uasi_guidance.pdf.

12

Routine events—During routine events, the emphasis for response-level emergency communications is on operability

and interoperability. These types of events are further delineated in the Usage element of the SAFECOM

Interoperability Continuum as planned events, localized emergency incidents, regional incident management

(interstate or intrastate), and daily use throughout the region. See Appendix 5 for a further description of the

SAFECOM Interoperability Continuum.

13

Jurisdiction—A geographical, political, or system boundary as defined by each individual State.

14

Significant events—During significant events, the emphasis for response-level emergency communications is on

interoperability and continuity of communications. Homeland Security Presidential Directive 8: National

Preparedness (HSPD-8) sets forth 15 National Planning Scenarios, highlighting a plausible range of significant

events such as terrorist attacks, major disasters, and other emergencies that pose the greatest risks to the Nation. Any

of these 15 scenarios should be considered when planning for a significant event during which all major emergency

communications infrastructure is destroyed.

15

The National Communications Capabilities Report, 2008.

16

SAFECOM’s Interoperability Continuum was designed to help the emergency response community and Federal,

State, local, and tribal policymakers address critical elements for success as they plan and implement interoperability

solutions: http://www.safecomprogram.gov/SAFECOM/tools/continuum/default.html.

7

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

These identified capabilities serve as the foundation for the NECP priority objectives,

initiatives, and recommended national milestones set forth in Section 3.

Exhibit 4: Emergency Communications Capabilities Needed to Achieve Future State

Lanes of the SAFECOM

Interoperability

Continuum

Capabilities Needed

Governance

• Strong government leadership

• Formal, thorough, and inclusive interagency governance

structures

• Clear lines of communication and decision-making

• Strategic planning processes

Standard Operating

Procedures (SOP)

• Standardized and uniform emergency responder interaction

during emergency response operations

• Standardized use and application of interoperable emergency

communications terminology, solutions, and backup systems

Technology

• Voice and data standards that pertain to real-time situational

information exchange and reports for emergency responders

before, during, and after response

• Uniform model and standard for emergency data information

exchange

• Testing and evaluation of emergency communications

technology to help agencies make informed decisions about

technology

• Emergency response communications technology based on

voluntary consensus standards

• Basic level of communications systems operability

Training and Exercises

• Uniform, standardized performance objectives to measure

effectiveness of emergency responders communications

capabilities

• Emergency response providers who are fully knowledgeable,

trained, and exercised on the use and application of day-to-day

and backup communications equipment, systems, and

operations irrespective of the extent of the emergency response

Usage

• Adequate resources and planning to cover not only initial

system and equipment investment but also the entire life cycle

(operations, exercising, and maintenance)

• Broad regional (interstate and intrastate) coordination in

technology investment and procurement planning

8

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

3. Achieving the Future State of Emergency Communications

This section describes the strategy for achieving the NECP’s future state for emergency

communications and for meeting the overall goals identified in Section 2. Specifically,

this section discusses in detail the seven Objectives that delineate a comprehensive

assessment of the capabilities needed to close existing gaps and achieve the long-term

vision. In the near- term, DHS will continue to work with its stakeholders on

implementing the NECP initiatives and attaining near-term goals. As previously defined,

the three critical elements of emergency communications are operability, interoperability,

and continuity of communications. Progress toward achieving each of the seven

objectives is essential in realizing improvements in all three of these primary elements of

emergency communications.

17

In addition, this section defines Supporting Initiatives

for each objective, with a focus on driving outcomes toward the future state. Each

initiative identifies current emergency communications activities and key gaps. To

implement these initiatives, there are Recommended National Milestones to define the

timelines and outcomes.

3.1 Objectives, Initiatives, and Milestones

The objectives and initiatives provide national guidance to Federal, State, local, and tribal

agencies to implement key activities to improve emergency communications. Milestones

provide key checkpoints to monitor NECP implementation. The proposed timelines for

completing these initiatives began when the NECP was delivered to Congress on July 31,

2008. OEC will then coordinate development of implementation strategies with partner

organizations at all levels of government, private sector organizations, and non-

governmental associations The NECP identifies the following objectives to improve

emergency communications for Federal, State, local, and tribal emergency responders:

1. Formal decisionmaking structures and clearly defined leadership roles coordinate

emergency communications capabilities.

2. Federal emergency communications programs and initiatives are collaborative

across agencies and aligned to achieve national goals.

3. Emergency responders employ common planning and operational protocols to

effectively use their resources and personnel.

4. Emerging technologies are integrated with current emergency communications

capabilities through standards implementation, research and development, and

testing and evaluation.

5. Emergency responders have shared approaches to training and exercises,

improved technical expertise, and enhanced response capabilities.

6. All levels of government drive long-term advancements in emergency

communications through integrated strategic planning procedures, appropriate

resource allocations, and public-private partnerships.

7. The Nation has integrated preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery

capabilities to communicate during significant events.

17

Note that no single objective is discretely linked to any one of the three elements (i.e., operability, interoperability, or

continuity of communications). Rather, progress in any objective area will result in improvements in each of the

three emergency communications components.

9

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

Substantial cooperation and collaboration across the stakeholder community are

necessary to achieve all of the milestones in each objective. The supporting initiatives

and recommended national milestones represent the DHS’ position on actions that must

occur and establish completion dates to meet NECP goals. DHS continues to work with

stakeholders at all levels of government to identify and verify ownership roles to drive

full participation and implementation of this Plan.

For some of the milestones, specific leadership and ownership roles are defined based on

associated mission areas, current activities, existing authorities, and feedback from

organizations during NECP development. In many cases, specific leadership roles to

achieve the milestones are not and presently cannot be defined. Although DHS has been

mandated by Congress to develop the NECP and coordinate its implementation, DHS has

limited authority to compel responsibilities and leadership roles—and the associated

expenditure of resources—for external organizations. To implement the NECP, OEC

will collaborate with its partner organizations to develop strategies that guide

achievement of the objectives, initiatives, and milestones. Exhibit 4 illustrates these

integrated elements of the NECP and depicts: A vision of the future state and goals that

support achievement of the vision; specific objectives to meet these goals; and supporting

initiatives with national milestones that define the outcomes and timelines required.

Exhibit 4: The NECP Roadmap

10

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

Objective 1: Formal Governance Structures and Clear Leadership

Roles

Formal decision-making structures and clearly defined leadership roles coordinate

emergency communications capabilities.

More than 50,000 independent agencies across the Nation routinely use emergency

communications. Each of these agencies is governed by the laws of its respective

jurisdiction or area of responsibility. No single entity is, or can be, in charge of the

Nation’s entire emergency communications infrastructure. In such an environment,

collaborative planning among all levels of government is critical for ensuring effective

and fully coordinated preparedness and response. Formal governance structures and

leadership are needed to manage these complex systems of people, organizations, and

technologies.

18

Current Emergency Communications Activities:

19

• National-level policies identify roles, responsibilities, and coordinating structures

for incident management (e.g., National Response Framework [NRF] and its

Emergency Support Function #2 [ESF#2], National Incident Management System

[NIMS] Joint Field Office Activation and Operations—Interagency Integrated

Standard Operating Procedure Annex E).

• The Statewide Communication Interoperability Plan (SCIP) Guidebookprovides

guidance on establishing a structure for governing statewide communications

interoperability planning efforts. All 56 States and territories now have SCIPs.

• The ECPC establishes a governance and decision-making structure for strategic

coordination of interdepartmental emergency communications at the Federal

level.

• FEMA leads the integration of tactical Federal emergency communications during

disasters and is developing requirements and an associated Disaster Emergency

Communications (DEC) Integration Framework for fulfilling emergency

communications needs during disasters.

• Decision-making bodies at the State, regional, and local levels coordinate

emergency communications issues (e.g., RECCWG,

statewide interoperability

coordinators and executive committees, local communications committees).

20

18

Most emergencies occur at the local level and are managed by local incident commanders. To best support the local

incident commander, Federal and State agencies must ensure the coordination of their interoperability efforts with

local agencies. This perspective is in agreement with the ERC’s guiding principles, SAFECOM Emergency

Response Council, Agreements on a Nationwide Plan for Interoperable Communications, Summer 2007.

19

A subset of relevant and current emergency communication activities has been identified for each objective in the

NECP; these subsets are not meant to be comprehensive, but represent examples of stakeholder input collected

during NECP development. Many additional activities are planned and underway across all levels of government.

20

As defined in Section 1805 of the Department of Homeland Security Act of 2007, RECCWGs assess emergency

communications capabilities within their respective regions, facilitate disaster preparedness through the promotion of

multijurisdictional and multiagency emergency communications networks, and ensure activities are coordinated with

all emergency communications stakeholders within the RECCWG’s associated FEMA region. The FEMA Regional

Administrator oversees the RECCWG and its activities, and the RECCWG is required to report annually (at a

minimum) to the FEMA Regional Administrator. The RECCWG advises on all aspects of emergency

communications in its respective Region and incorporates input from emergency communications stakeholders and

representatives from all levels of government as well as from nongovernmental and private sector agencies.

11

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

• OEC is developing a governance sustainability and SCIP implementation

methodology to provide guidance and share lessons learned in creating and

sustaining effective statewide communications interoperability governance

structures for SCIP implementation.

Key Gaps and Obstacles Driving Action:

• In many cases, emergency response agencies are unaware of (or have yet to adopt

and integrate) national-level policies that define roles, responsibilities, and

coordinating structures for emergency communications.

• State Interoperability Executive Committees (SIEC) or their equivalents do not

have uniform structures, they typically act in an ad hoc capacity, and they often

lack inclusive membership.

• The Nation does not have an objective, standardized framework to identify and

assess emergency communications capabilities nationwide. Thus, it is difficult

for jurisdictions to invest in building and maintaining appropriate levels of

operability, interoperability, and continuity of communications.

• Emergency communications strategic planning efforts vary in scope and often do

not address the operability and interoperability concerns of all stakeholders.

• Many agencies often do not consider communications planning to be a priority

and therefore do not allocate resources for participation in planning activities.

• There is a need for greater Federal department and agency participation in State,

regional, and local governance and planning processes.

• Many States do not have full-time statewide interoperability coordinators, or

equivalent positions, to focus on the activities needed to drive change.

Supporting Initiatives and Milestones to Address Key Gaps:

• Initiative 1.1: Facilitate the development of effective governance groups and

designated emergency communications leadership roles. Uniform criteria and

best practices for governance and emergency communications leadership across

the Nation will better equip emergency response agencies to make informed

decisions that meet the needs of their communities. Establishing effective

leadership positions and representative governance groups nationwide will

standardize decision-making and enhance the ability of emergency response

agencies to share information and respond to incidents.

Recommended National Milestones:

o Within 12 months, DHS will establish a central repository of model formal

agreements (i.e., Memorandums of Agreement [MOA], Memorandums of

Understanding [MOU], and Mission Assignments) and information that will

enhance interstate and intrastate coordination.

21

o Within 12 months, all States and territories should establish full-time

statewide interoperability coordinators or equivalent positions.

21

This repository is envisioned as a component of the ECPC clearinghouse function. Please refer to Initiative 2.1 for

additional information and activities regarding the ECPC clearinghouse.

12

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

o Within 12 months, DHS will conduct a National Emergency

Communications workshop to provide an opportunity for RECCWG

participants, statewide emergency communications coordinators, and other

interested parties to collaborate with one another and with Federal

representatives from the ECPC and FPIC.

o Within 12 months, RECCWGs are fully established as a primary link for

disaster emergency communications among all levels of government at the

FEMA regional level, sharing information, identifying common problems,

and coordinating multistate operable and interoperable emergency response

initiatives and plans among Federal, State, local, and tribal agencies.

22

o Within 12 months, SIECs (or their equivalents) in all 56 States and

territories should incorporate the recommended membership as outlined in

the SCIP Guidebook and should be established via legislation or executive

order by an individual State’s governor.

o Within 18 months, DHS will publish uniform criteria and best practices for

establishing governance groups and emergency communications leadership

roles across the Nation.

• Initiative 1.2: Develop standardized emergency communications

performance objectives and link to DHS’ overall system for assessing

preparedness capabilities nationwide. DHS will collaborate with Federal,

regional, State,

23

local, and tribal governments and organizations, as well as with

the private sector, to develop a more comprehensive and targeted set of evaluation

criteria for defining and measuring communications requirements across the

Nation. To prevent duplicative reporting requirements for its stakeholders, DHS

will ensure these assessment efforts leverage existing reporting requirements (e.g.,

for SCIPs, Tactical Interoperable Communications Plans [TICPs], and State

Preparedness Reports) and grant program applications (e.g., for the Interoperable

Emergency Communications Grant Program [IECGP] and the Homeland Security

Grant Program [HSGP]). Evaluation criteria will be based on the approach being

followed in DHS’ implementation plans for the National Preparedness

Guidelines/Target Capabilities List (TCL).

24

22

FEMA organizes the United States into 10 FEMA regions. Each FEMA region has its own Regional Headquarters

led by a Regional Administrator. FEMA regions are responsible for working in partnership with emergency

management agencies from each state within the respective region to prepare for, respond to, and recover from

disasters. FEMA regions and their Regional Administrators will be leveraged to provide oversight, implementation,

and execution for their respective RECCWGs.

23

This collaboration would include State homeland security advisors and statewide interoperability coordinators.

24

DHS is currently developing TCL implementation plans for animal health, EOC management, intelligence, onsite

incident management, mass transit protection, and weapons of mass destruction (WMD)/hazardous material (hazmat)

rescue and decontamination. Communication requirements will be based on the concepts and principles outlined in

the NECP and in the baseline principles provided in the NIMS (e.g., common operating picture; interoperability;

reliability, scalability and portability; and resiliency and redundancy). These requirements will be based on the

command requirements for response-level emergency communications as defined in the NECP, and will also include

the full range of communications requirements for all of the standardized types of communications (e.g., strategic,

tactical, support, public address) identified in the NIMS.

13

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

Recommended National Milestones:

o Within 12 months, DHS will develop a standardized framework for

identifying and assessing emergency communications capabilities

nationwide.

o Within 18 months, DHS’ emergency communications capability framework,

in preparation for release, will be reviewed during a series of technical

working group meetings with stakeholders from the emergency response

community.

o Within 24 months, the emergency communications capability framework

will be incorporated as the communications and information management

capability in the DHS/FEMA National Preparedness Guidelines/TCL, which

will serve as a basis for future grant policies.

• Initiative 1.3: Integrate strategic and tactical emergency communications

planning efforts across all levels of government. Tactical and strategic

coordination will eliminate unnecessary duplication of effort and maximize

interagency synchronization, bringing together tactical response and strategic

planning.

Recommended National Milestones:

o Within 12 months, DHS will make available an effective communications-

asset management tool containing security and privacy controls to allow for

nationwide intergovernmental use.

o Within 12 months, tactical planning among Federal, State, local, and tribal

governments occurs at the regional interstate level.

• Initiative 1.4: Develop coordinated grant policies that promote Federal

participation and coordination in communications planning processes,

governance bodies, joint training and exercises, and infrastructure sharing.

The largest investment category of DHS grant funds is interoperable

communications. Federal acquisition, deployment, and operating funds

supporting Federal mission-critical communication systems often cannot be used

to support State and local communication needs (when otherwise appropriate).

These limitations on the use of these funds can inhibit the realization of the goals

of coordination and interoperability, as systems are developed, deployed, and

maintained.

Recommended National Milestones:

o Within 12 months, DHS fiscal year (FY) 2009 grant policies provides

guidance on how to best support national interoperability needs through the

promotion of shared infrastructure, cooperative planning, and coordinated

governance.

14

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

o Within 12 months, best practices for sharing infrastructure, addressing

spectrum issues, and developing agreements among Federal, State, and local

emergency response communicators are promoted through DHS technical

assistance programs, in accordance with applicable laws.

15

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

Objective 2: Coordinated Federal Activities

Federal emergency communications programs and initiatives are collaborative across

agencies and aligned to achieve national goals.

Federal departments and agencies rely on emergency communications capabilities to

support mission-critical operations (e.g., law enforcement, disaster response, homeland

security). Traditionally, individual Federal departments and agencies have not

considered the benefits of planning and implementing emergency communications

systems in conjunction with other Federal departments and agencies, or with State and

local agencies. It is critical that Federal programs and initiatives—including grant

programs—responsible for managing and providing emergency communications, are

coordinated to minimize duplication, maximize Federal investments, and ensure

interoperability.

Current Emergency Communications Activities:

• The ECPC has been established to serve as the Federal focal point for

interoperable emergency communications. An ECPC clearinghouse is being

designed as a central repository for Federal, State, local, and tribal governments to

publish and share tactics, techniques, practices, programs, and policies that

enhance interoperability for emergency communications.

• RECCWGs are being established to provide regional coordination points for

emergency communications preparedness, response, and recovery for Federal,

State, local, and tribal governments within each FEMA region.

• Federal, State, and local agencies are both independently and jointly upgrading

and modernizing their tactical communications systems. There are several

Federal grant programs (e.g., the HSGP and the Public Safety Interoperable

Communications [PSIC] Grant Program) that State, local, and tribal entities can

use to enhance their emergency communications capabilities.

• DHS is establishing the IECGP to support projects that focus on improving

operable and interoperable emergency communications for State, local, and tribal

agencies and for international border agencies. IECGP guidance is being

developed to close gaps associated with governance, planning, training, and

exercises and currently focuses grant funds on initiatives that are not focused on

technology.

• OEC’s Interoperable Communications Technical Assistance Program (ICTAP)

helps to enhance interoperable emergency communications among Federal, State,

local, and tribal governments by providing assistance on governance, SOPs,

technology, training and exercises, usage, and engineering issues. The ICTAP

leverages and works with other Federal, State, and local interoperability efforts

whenever possible to enhance the overall capacity for agencies and individuals to

communicate with one another.

16

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

Key Gaps and Obstacles Driving Action:

• Information on Federal emergency communications programs, activities, and

standards is not consistently or adequately shared with State and local agencies.

• Federal emergency responders are not integrated into existing State and local

networks because of capacity, frequency coordination, and channel congestion

issues.

• Federal grant programs for interoperable emergency communications are not

targeting gaps in a consistent and coordinated manner.

• There is a lack of overall Federal coordination at the regional level and

participation in regional UASI and statewide planning activities (e.g., SIEC).

• Regulatory and legal issues act as barriers to the further use of shared capabilities

across all levels of government.

Supporting Initiatives and Milestones to Address Key Gaps:

• Initiative 2.1: Establish a source of information about Federal emergency

communications programs and initiatives. There are a number of Federal

programs and initiatives focused on emergency communications. DHS will

establish a focal point for coordinating intergovernmental emergency

communications to help the Federal Government identify duplicative efforts and

achieve greater economies of scale.

Recommended National Milestones:

o Within 12 months, Federal departments and agencies leverage the ECPC as

the central coordinating body for providing Federal input into, and

comments on, Federal emergency communications projects, plans, and

reports.

o Within 12 months and annually thereafter, the ECPC submits a strategic

assessment to Congress, detailing progress to date, the remaining obstacles

to interoperable emergency communications, and Federal coordination

efforts.

o Within 12 months, DHS establishes a uniform method for coordination and

information sharing between ECPC and the RECCWGs.

o Within 18 months, the ECPC web-based clearinghouse portal commences

operation, with strong consideration given to leveraging existing portals,

such as the Homeland Security Information Network (HSIN),

DHS ONE-Net, and DHS Interactive.

o Within 24 months, DHS establishes targeted outreach and training activities

to ensure that stakeholders across the Nation are aware of the availability of

ECPC clearinghouse resources.

• Initiative 2.2: Coordinate all technical assistance programs to provide

greater consistency for the delivery of Federal services. Coordinated and

uniform technical assistance will improve the reliability of communications

17

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

systems and operator expertise. Technical assistance can be targeted to address

gaps identified in SCIPs and the priorities outlined in the NECP.

Recommended National Milestones:

o Within 6 months, through the ECPC, a catalog of current technical

assistance programs will be established, to both ensure the awareness of

available technical assistance and reduce duplication.

o Within 6 months, DHS establishes a focal point for consistent and

comprehensive technical assistance and guidance for emergency

communications planning with Federal, State, local, and tribal agencies.

o Within 12 months, Federal agencies establish a common methodology

across all Federal operability and interoperability technical assistance

programs and will train the personnel who provide technical assistance on

the use of this methodology.

o Within 18 months, DHS establishes a consistent and coordinated method for

States and localities to request Federal technical assistance.

• Initiative 2.3: Target Federal emergency communications grants to address

gaps identified in the NECP, SCIPs, and TICPs. Targeted Federal grants will

allow emergency response agencies to address communications gaps and

coordinate planning efforts. Federal grant funding represents only a small

fraction of overall emergency response emergency communications investment.

Nonetheless, such funding is a key tool by which State and local emergency

response agencies can address national emergency communication priorities.

Recommended National Milestones:

o Within 12 months, all IECGP investments are coordinated with the

statewide interoperability coordinator and SIEC, or its equivalent, to support

State administrative agency investments, including filling the gaps identified

in the NECP and SCIPs.

o Within 12 months, DHS grant policies are developed to encourage regional

operable and interoperable solutions, including shared solutions, and to

prioritize cost-effective measures and multi-applicant investments.

o Within 12 months, the ECPC stands up a working group to coordinate grant

priorities across Federal grant programs.

• Initiative 2.4: Enable resource sharing and improve operational efficiencies.

Most government-owned wireless infrastructure that supports emergency

response exists at the State and local levels. Further, many State and local

agencies have modernized and expanded their systems through mechanisms such

as Federal grant programs (e.g., the HSGP and the PSIC Grant Program), or they

are currently in the process of doing so. By working with State and local

agencies, Federal agencies can benefit from these improvements by leveraging

both existing and planned infrastructure to improve operability and

interoperability. In addition, there are a number of Federal-level programs and

18

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

initiatives involving the deployment of communications infrastructure, which

present opportunities for resource and infrastructure sharing (e.g., spectrum,

Radio Frequency [RF] sites). Federal agencies should work to better understand

existing and planned programs, initiatives, and infrastructure across all levels of

government to improve coordination, maximize investments, and more quickly

field capabilities.

Recommended National Milestones:

o Within 6 months, DHS conducts an assessment of shared regional/State

systems to determine the potential for resource sharing among Federal,

State, local, and tribal agencies.

o Within 12 months, DHS prioritizes sharing opportunities, based on Federal

emergency communications requirements.

o Within 24 months, DHS establishes partnerships between Federal, State,

local, and tribal agencies, as appropriate.

• Initiative 2.5: Establish interoperability capabilities and coordination

between domestic and international partners. Emergencies occurring near the

Mexican and Canadian borders frequently require a bi-national response,

necessitating interoperability with international partners. These countries often

have different technical configurations and regulatory statutes than the United

States. Coordination is essential to ensure that domestic and international legal

and regulatory requirements are followed.

Recommended National Milestones:

o Within 6 months, and annually thereafter, hold plenary meetings of the

United States-Mexico Joint Commission on Resolution of Radio

Interference to address identified interference cases between the United

States and Mexico.

o Within 12 months, DHS establishes best practices for emergency

communications coordination with international partners (i.e., cross border

interoperability coordination with Mexico and Canada).

o Within 24 months, DHS establishes demonstration projects between

Federal, State, local, and tribal agencies, and international partners, to

improve interoperability in border areas that are at risk for large-scale

incidents (natural or man-made) requiring international responses (including

illegal border crossings or smuggling activities that result from an incident).

19

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

Objective 3: Common Planning and Operational Protocols

Emergency responders employ common planning and operational protocols to effectively

use their resources and personnel.

Agencies often create SOPs to meet their unique emergency communications

requirements. In recent years, with support from the Federal Government, emergency

responders have developed standards for interoperability channel naming, the use of

existing nationwide interoperability frequencies, and the use of plain language. NIMS

represents an initial step in establishing national consistency for how agencies and

jurisdictions define their operations; however, additional steps are required to continue

streamlining response procedures.

Current Emergency Communications Activities:

• National-level preparedness and incident management doctrines (e.g., NRF,

NIMS, Joint Field Office Activation and Operations Interagency Integrated

Standard Operating Procedures, TCLs) are in various stages of development;

these exist to define common principles, roles, structures, and target capabilities

for incident response.

• Strategic and tactical interoperable emergency communications planning has

begun at the State and local levels (e.g., TICPs, SCIPs, FEMA, State and regional

emergency communications planning).

• Common nomenclature initiatives for interoperability channels (e.g., NPSTC

Channel Naming Report) are underway.

• FEMA has developed a DEC Integration Framework and continues to support

both government and nongovernmental organizations in developing plans and

response frameworks and defining roles and responsibilities.

• FEMA’s NIMS Integration Center is developing the National Emergency

Responder Credentialing System (NERCS).

• Federal grant guidance (e.g., FY 2008 SAFECOM grant guidance; FY 2008

IECGP grant guidance) exists for migrating current radio practices to plain

language standards.

• The Office for Interoperability and Compatibility (OIC), in coordination with

OEC, is developing an SOP Development Guide, a Shared Channel Guide v2.0,

and a brochure on plain language.

• DHS recently issued Federal Continuity Directive-1, which establishes continuity

planning guidelines for Federal departments and agencies.

• The Office of Science and Technology Policy issued the National

Communications System Directive (NCSD) 3-10, Minimum Requirements for

Continuity Communications Capabilities as planning direction for

communications capabilities that support continuity of operations.

Key Gaps and Obstacles Driving Action:

• There are inconsistencies in the use of plain language, the interoperability channel

naming conventions, the interoperability frequencies, and SOPs.

20

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

• Nationwide adoption and usage of NIMS, NRF, and NERCS has been slow

because some users are often unfamiliar with the direction and intent of these

policies.

• Inconsistent use of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)-designated

national interoperability channels has limited the effectiveness of this

interoperability solution for emergency response communications systems

operating in the same frequency band.

Supporting Initiatives and Milestones to Address Key Gaps:

• Initiative 3.1: Standardize and implement common operational protocols

and procedures. A national adoption of plain-language radio practices and

uniform common channel naming, along with the programming and use of

existing national interoperability channels, will allow agencies across all

disciplines to effectively share information on demand and in real time. Using

common operational protocols and procedures avoids the confusion that using

disparate coded language systems and various tactical interoperability frequencies

can create. Use of the existing nationwide interoperability channels with common

naming will immediately address interoperability requirements for agencies

operating in the same frequency band.

25

Recommended National Milestones:

o Within 6 months, OEC develops plain-language guidance in concert with

State and local governments to address the unique needs of agencies/regions

and disciplines across the Nation.

o Within 6 months, American National Standards Institute (ANSI) certifies,

and emergency response accreditation organizations accept, the NPSTC

Channel Naming Guide as the national standard for FCC-designated

nationwide interoperability channels.

o Within 9 months, the National Integration Center’s (NIC) Incident

Management Systems Integration Division (IMSID) promotes plain-

language standards and associated guidance.

o Within 12 months, grant policies for Federal programs that support

emergency communications are coordinated, providing incentives for States

to include plans to eliminate coded substitutions throughout the Incident

Command System (ICS).

o Within 12 months, Federal agencies identify a uniform naming system for

the National Telecommunications and Information Administration’s (NTIA)

designated nationwide interoperability channels, and this naming system is

integrated into the NPSTC Guide.

25

TheNational Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) and members of the Interdepartment

Radio Advisory Committee (IRAC), with support from the FCC, revised the NTIA Manual of Regulations and

Procedures for Federal Radio Frequency Management. The NTIA amended the Conditions for Use and eliminated

the requirement to establish an MOU between non-Federal and Federal entities on the use of the law enforcement

(LE) and IR channels. However, the new conditions do require the non-Federal entity to obtain a license and include

a point of contact in the license application it submits to the FCC for use of the LE/IR channels.

21

National Emergency Communications Plan July 2008

o Within 18 months, DHS develops training and technical assistance programs

for the National Interoperability Field Operations Guide (NIFOG);

26

programs an appropriate set of frequency-band-specific nationwide

interoperability channels into all existing emergency responder radios;

27

and

preprograms an appropriate set of frequency-band-specific nationwide

interoperability channels into emergency response radios that are

manufactured or purchased through Federal funding as a standard

requirement.

o Within 24 months, all SCIPs reflect plans to eliminate coded substitutions

throughout the ICS, and agencies incorporate the use of existing nationwide

interoperability channels into SOPs, training, and exercises at the Federal,

State, regional, local, and tribal levels.

• Initiative 3.2: Implementation of the NIMS and the NRF across all levels of

government. Emergency response agencies across all levels of government

should adopt and implement national-level policies and guidance to ensure a

common approach to incident management and communications support.

Implementation of these policies will establish clearly defined communications