1

BILLING CODE 4910-13-P

DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

Federal Aviation Administration

14 CFR Parts 1, 11, 47, 48, 89, 91, and 107

[Docket No.: FAA-2019-1100; Amdt. Nos. 1-75, 11-63, 47-31, 48-3, 89-1, 91-361, and 107-7]

RIN 2120–AL31

Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft

AGENCY: Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Department of Transportation (DOT).

ACTION: Final rule.

SUMMARY: This action requires the remote identification of unmanned aircraft. The remote

identification of unmanned aircraft in the airspace of the United States will address safety,

national security, and law enforcement concerns regarding the further integration of these aircraft

into the airspace of the United States, laying a foundation for enabling greater operational

capabilities.

DATES: Effective dates: Except for subpart C of part 89, this rule is effective [INSERT DATE

60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. Subpart C of

part 89 is effective INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AND 18 MONTHS AFTER DATE OF

PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. The incorporation by reference of certain

publications listed in the rule is approved by the Director of the Federal Register as of [INSERT

DATE 60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER].

Compliance dates: Compliance with §§ 89.510 and 89.515 is required [INSERT DATE 60

DAYS AND 18 MONTHS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL

REGISTER]. Compliance with §§ 89.105, 89.110, and 89.115, and subpart C of part 89 is

This is a copy of the final rule that h

as been submitted to the Federal Register for publication.

2

required [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AND 30 MONTHS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN

THE FEDERAL REGISTER].

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Ben Walsh, Flight Technologies and

Procedures Division, Federal Aviation Administration, 470 L’Enfant Plaza S.W., Suite 4102,

Washington, D.C, 20024; telephone 1-844-FLY-MY-UA (1-844-359-6981);

email: [email protected].

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary

A. Remote Identification Requirements

B. Registration Requirements

C. Elimination of the Network-Based Remote Identification Requirement

D. Summary of Benefits and Costs

II. Authority for this Rulemaking

III. Background

IV. Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft

A. Clarification of Use of the Term Unmanned Aircraft in this Rule

B. Purpose for the Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft

C. Public Comments and FAA Response

V. Terms Used in this Rule

A. Definition of Unmanned Aircraft System

B. Definition of Visual Line of Sight

C. Definition of Broadcast

D. Definition of Home-Built Unmanned Aircraft

E. Definition of Declaration of Compliance

F. Requests for other Definitions

VI. Applicability of Operating Requirements

A. Discussion of the Final Rule

B. Public Comments and FAA Response

VII. Operating Requirements for Remote Identification

3

A. Elimination of Network-based Remote Identification Requirement

B. Limited Remote Identification UAS

C. Standard Remote Identification Unmanned Aircraft

D. Remote Identification Broadcast Modules

E. Other Broadcast Requirements Applicable to Standard Remote Identification Unmanned

Aircraft and Unmanned Aircraft with Remote Identification Broadcast Modules

F. Unmanned Aircraft without Remote Identification

VIII. Message Elements and Minimum Performance Requirements: Standard Remote

Identification Unmanned Aircraft

A. Message Elements for Standard Remote Identification Unmanned Aircraft

B. Minimum Performance Requirements for Standard Remote Identification Unmanned

Aircraft

C. Message Elements Performance Requirements for Standard Remote Identification

Unmanned Aircraft

IX. Message Elements and Minimum Performance Requirements: Remote Identification

Broadcast Modules

X. Privacy Concerns on the Broadcast of Remote Identification Information

A. Discussion of the Final Rule

B. Public Comments and FAA Response

XI. Government and Law Enforcement Access to Remote Identification Information

A. Discussion of the Final Rule

B. Public Comments and FAA Response

XII. FAA-Recognized Identification Areas

A. Discussion of the Final Rule

B. Eligibility

C. Time Limit for Submitting an Application to Request an FAA-Recognized Identification

Area

D. Process to Request an FAA-Recognized Identification Area and FAA Review for Approval

E. Official List of FAA-Recognized Identification Areas

F. Amendment of the FAA-Recognized Identification Area

G. Duration of an FAA-Recognized Identification Area, Expiration, and Renewal

H. Requests to Terminate an FAA-recognized Identification Area

I. Termination by FAA and Petitions to Reconsider the FAA’s Decision to Terminate an FAA-

Recognized Identification Area

XIII. Means of Compliance

A. Performance-Based Regulation

4

B. Applicability and General Comments

C. Submission of a Means of Compliance

D. Acceptance of a Means of Compliance

E. Rescission of FAA Acceptance of a Means of Compliance

F. Record Retention Requirements

XIV. Remote Identification Design and Production

A. Applicability of Design and Production Requirements

B. Exceptions to the Applicability of Design and Production Requirements

C. Requirement to Issue Serial Numbers

D. Labeling Requirements

E. Production Requirements

F. Accountability

G. Filing a Declaration of Compliance

H. Acceptance of a Declaration of Compliance

I. Rescission of FAA Acceptance of a Declaration of Compliance

J. Record Retention

XV. Registration

A. Aircraft Registration Requirements

B. Registration Fees for the Registration of Individual Aircraft

C. Information Included in the Application for Registration

D. Proposed Changes to the Registration Requirements to Require a Serial Number as Part of

the Registration Process

E. Serial Number Marking

F. Compliance Dates

XVI. Foreign Registered Civil Unmanned Aircraft Operated in the United States

A. Discussion of the Final Rule

B. Public Comments and FAA Response

XVII. ADS-B Out and Transponders for Remote Identification

A. Discussion of the Final Rule

B. Public Comments and FAA Response

XVIII. Environmental Analysis

A. Public Comments and FAA Response

XIX. Effective and Compliance Dates

A. Effective Date of this Rule

B. Production Requirements Compliance Date

5

C. Operational Requirements Compliance Date

D. Incentives for Early Compliance

XX. Comments on the Regulatory Impact Analysis—Benefits and Costs

A. General Comments about Cost Impacts of the Rule

B. Comments on Benefits and Cost Savings

C. Comments on Data and Assumptions

D. Comments on Regulatory Alternatives

E. Miscellaneous Comments

XXI. Guidance Documents

XXII. Regulatory Notices and Analyses

A. Regulatory Evaluation

B. Regulatory Flexibility Act

C. International Trade Impact Assessment

D. Unfunded Mandates Assessment

E. Paperwork Reduction Act

F. International Compatibility and Cooperation

G. Environmental Analysis

XXIII. Executive Order Determinations

A. Executive Order 13132, Federalism

B. Executive Order 13175, Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments

C. Executive Order 13211, Regulations that Significantly Affect Energy Supply, Distribution,

or Use

D. Executive Order 13609, Promoting International Regulatory Cooperation

E. Executive Order 13771, Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs

XXIV. Additional Information

A. Availability of Rulemaking Documents

B. Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act

List of Abbreviations Frequently Used in this Document

AC – Advisory Circular

ADS-B – Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast

AGL – above ground level

ARC – Aviation Rulemaking Committee

ATC – Air traffic control

6

BVLOS – Beyond visual line of sight

DOT – U.S. Department of Transportation

FAA – Federal Aviation Administration

GPS – Global Positioning System

ICAO – International Civil Aviation Organization

LAANC – Low Altitude Authorization and Notification Capability

LOS – line-of-sight

MOA – Memorandum of Agreement

NPRM – notice of proposed rulemaking

OMB – Office of Management and Budget

UAS – Unmanned aircraft system

UAS-ID ARC – UAS Identification and Tracking Aviation Rulemaking Committee

USS – UAS service supplier

UTM – Unmanned aircraft systems traffic management

VLOS – visual line of sight

I. Executive Summary

This rule establishes requirements for the remote identification of unmanned aircraft

1

operated in the airspace of the United States. Remote identification (commonly known as

Remote ID) is the capability of an unmanned aircraft in flight to provide certain identification,

1

The FAA does not use the terms unmanned aircraft system and unmanned aircraft interchangeably. The FAA uses

the term unmanned aircraft as defined in 14 CFR 1.1 to refer specifically to the unmanned aircraft itself. The FAA

uses the term unmanned aircraft system to refer to both the unmanned aircraft and any communication links and

components that control the unmanned aircraft. As explained in section V.A of this rule, the FAA is adding the

definition of unmanned aircraft system to 14 CFR part 1.

The FAA acknowledges that UAS may have components produced by different manufacturers (e.g., an unmanned

aircraft could be manufactured by one manufacturer and the control station could be manufactured by another). In

addition, unmanned aircraft that operate beyond the radio-line-of-sight may use third-party communication links. As

finalized, the remote identification requirements in this final rule apply to the operation and the design and

production of unmanned aircraft. Unmanned aircraft producers are responsible for ensuring that the unmanned

aircraft comply with the design and production requirements of this rule even when the unmanned aircraft uses

control station equipment (such as a smart phone) or communication links manufactured by a different person. The

unmanned aircraft producer must address how any dependencies on control station functionality are incorporated as

part of the remote identification design and production requirements.

7

location, and performance information that people on the ground and other airspace users can

receive. The remote identification of unmanned aircraft is necessary to ensure public safety and

the safety and efficiency of the airspace of the United States. Remote identification provides

airspace awareness to the FAA, national security agencies, law enforcement entities, and other

government officials. The information can be used to distinguish compliant airspace users from

those potentially posing a safety or security risk. Remote identification will become increasingly

important as the number of unmanned aircraft operations increases in all classes of airspace in

the United States. While remote identification capability alone will not enable routine expanded

operations, such as operations over people or beyond visual line of sight, it is the next

incremental step toward enabling those operations.

Unmanned aircraft operating in the airspace of the United States are subject to the

operating requirements of this rule, irrespective of whether they are operating for recreational or

commercial purposes. The rule requires operators to seek special authorization to operate

unmanned aircraft without remote identification for aeronautical research and other limited

purposes.

Unmanned aircraft produced for operation in the airspace of the United States are subject

to the production requirements of this rule. There are limited exceptions allowing the production

of unmanned aircraft without remote identification, which include home-built unmanned aircraft

and unmanned aircraft of the United States Government, amongst others.

A. Remote Identification Requirements

There are three ways to comply with the operational requirements for remote

identification. The first way is to operate a standard remote identification unmanned aircraft that

broadcasts identification, location, and performance information of the unmanned aircraft and

8

control station. The second way to comply is by operating an unmanned aircraft with a remote

identification broadcast module. The broadcast module, which broadcasts identification,

location, and take-off information, may be a separate device that is attached to an unmanned

aircraft, or a feature built into the aircraft. The third way to comply allows for the operation of

unmanned aircraft without any remote identification equipment, where the UAS is operated at

specific FAA-recognized identification areas. The requirements for all three of these paths to

compliance are specified in this rule.

Except in accordance with the requirements of this rule, no unmanned aircraft can be

produced for operation in the airspace of the United States after [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS

AND 18 MONTHS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER] and

no unmanned aircraft can be operated in the airspace of the United States after [INSERT DATE

60 DAYS AND 30 MONTHS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL

REGISTER].

1. Standard Remote Identification Unmanned Aircraft

Standard remote identification unmanned aircraft broadcast the remote identification

message elements directly from the unmanned aircraft from takeoff to shutdown. The required

message elements include: (1) a unique identifier to establish the identity of the unmanned

aircraft; (2) an indication of the unmanned aircraft latitude, longitude, geometric altitude, and

velocity; (3) an indication of the control station latitude, longitude, and geometric altitude; (4) a

time mark; and (5) an emergency status indication. Operators may choose whether to use the

serial number of the unmanned aircraft or a session ID (e.g., an alternative form of identification

that provides additional privacy to the operator) as the unique identifier. The required message

9

elements for standard remote identification unmanned aircraft are discussed in section VIII.A of

this preamble.

A person can operate a standard remote identification unmanned aircraft only if: (1) it has

a serial number that is listed on an FAA-accepted declaration of compliance; (2) its remote

identification equipment is functional and complies with the requirements of the rule from

takeoff to shutdown; (3) its remote identification equipment and functionality have not been

disabled; and (4) the Certificate of Aircraft Registration of the unmanned aircraft used in the

operation must include the serial number of the unmanned aircraft, as per applicable

requirements of parts 47 and 48, or the serial number of the unmanned aircraft must be provided

to the FAA in a notice of identification pursuant to § 89.130 prior to the operation.

Persons operating a standard remote identification unmanned aircraft in the airspace of

the United States must comply with the operational rules in subpart B of part 89 by [INSERT

DATE 60 DAYS AND 30 MONTHS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL

REGISTER].

Operating requirements for standard remote identification unmanned aircraft are

discussed in greater detail in section VII.C of this preamble.

2. Remote Identification Broadcast Modules

An unmanned aircraft can be equipped with a remote identification broadcast module that

broadcasts message elements from takeoff to shutdown. The required message elements include:

(1) the serial number of the broadcast module assigned by the producer; (2) an indication of the

latitude, longitude, geometric altitude, and velocity of the unmanned aircraft; (3) an indication of

the latitude, longitude, and geometric altitude of the unmanned aircraft takeoff location; and (4) a

10

time mark. The required message elements for remote identification broadcast modules are

discussed in section IX of this preamble.

Persons can operate an unmanned aircraft equipped with a remote identification

broadcast module only if: (1) the remote identification broadcast module meets the requirements

of this rule; (2) the serial number of the remote identification broadcast module is listed on an

FAA-accepted declaration of compliance; (3) the Certificate of Aircraft Registration of the

unmanned aircraft used in the operation includes the serial number of the remote identification

broadcast module, or the serial number of the unmanned aircraft must be provided to the FAA in

a notice of identification pursuant to § 89.130 prior to the operation; (4) from takeoff to

shutdown the remote identification broadcast module broadcasts the remote identification

message elements from the unmanned aircraft; and (5) the person manipulating the flight

controls of the unmanned aircraft system must be able to see the unmanned aircraft at all times

throughout the operation.

A person operating an unmanned aircraft equipped with a remote identification broadcast

module in the airspace of the United States must comply with the operational rules in subpart B

of part 89 by [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AND 30 MONTHS AFTER DATE OF

PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER].

The operating requirements for remote identification broadcast modules are discussed in

greater detail in section VII.D of this preamble.

3. Unmanned Aircraft without Remote Identification Equipment

This rule requires all unmanned aircraft operating in the airspace of the United States to

have remote identification capabilities, except as described below.

11

Upon full implementation of this rule, most unmanned aircraft will have to be produced

as standard remote identification unmanned aircraft. However, there will be some unmanned

aircraft (e.g., home-built unmanned aircraft and existing unmanned aircraft produced prior to the

date of compliance of the production requirements of this rule) that might not meet the

requirements for standard remote identification unmanned aircraft.

Persons operating an unmanned aircraft without remote identification in the airspace of

the United States must comply with the operational rules in subpart B of part 89 by [INSERT

DATE 60 DAYS AND 30 MONTHS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL

REGISTER]. Unless operating under an exception to the remote identification operating

requirements, a person operating an unmanned aircraft without remote identification must always

operate within visual line of sight

2

and within an FAA-recognized identification area.

An FAA-recognized identification area is a defined geographic area where persons can

operate UAS without remote identification, provided they maintain visual line of sight. Persons

eligible to request establishment of FAA-recognized identification areas include community-

based organizations recognized by the Administrator and educational institutions including

primary and secondary educational institutions, trade schools, colleges, and universities. The

FAA will begin accepting applications for FAA-recognized identification areas on [INSERT

DATE 60 DAYS AND 18 MONTHS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL

REGISTER]. The FAA will maintain a list of FAA-recognized identification areas at

https://www.faa.gov. FAA-recognized identification areas are discussed further in section XII of

this preamble.

2

Part 89 limits unmanned aircraft without remote identification and unmanned aircraft with remote identification

broadcast modules to visual line of sight operations. Nothing in part 89 authorizes beyond visual line of sight

(BVLOS) operations for any unmanned aircraft; such authority will spring from other FAA regulations.

12

4. Prohibition against the Use of ADS-B Out and Transponders

This rule prohibits use of ADS-B Out and transponders for UAS operations under

14 CFR part 107 unless otherwise authorized by the FAA, and defines when ADS-B Out is

appropriate for UAS operating under part 91. The FAA is concerned the potential proliferation of

ADS-B Out transmitters on unmanned aircraft may negatively affect the safe operation of

manned aircraft in the airspace of the United States. The projected numbers of unmanned aircraft

operations have the potential to saturate available ADS-B frequencies, affecting ADS-B

capabilities for manned aircraft and potentially blinding ADS-B ground receivers. Therefore,

unmanned aircraft operators, with limited exceptions, are prohibited from using ADS-B Out or

transponders. The prohibition against the use of ADS-B Out and transponders is discussed in

section XVII of this preamble.

Persons must comply with the ADS-B Out and transponder prohibition as of [INSERT

DATE 60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER].

5. Design and Production

Standard remote identification unmanned aircraft and remote identification broadcast

modules must be designed and produced to meet the requirements of this rule. The FAA

recognizes that UAS technology is continually evolving, making it necessary to harmonize new

regulatory action with technological advancements. To promote that harmonization, the FAA is

implementing performance-based requirements to describe the desired outcomes, goals, and

results for remote identification without establishing a specific means or process for regulated

entities to follow.

A person designing or producing a standard remote identification unmanned aircraft or

broadcast module for operation in the United States must show that the unmanned aircraft or

13

broadcast module meets the requirements of an FAA-accepted means of compliance. A means of

compliance describes the methods by which the person complies with the performance-based

requirements for remote identification.

Under this rule, anyone can create a means of compliance; however, the FAA must

accept that means of compliance before it can be used for the design or production of any

standard remote identification unmanned aircraft or remote identification broadcast module. A

person seeking acceptance by the FAA of a means of compliance for standard remote

identification unmanned aircraft or remote identification broadcast modules is required to submit

the means of compliance to the FAA. The FAA reviews the means of compliance to determine if

it meets the minimum performance requirements and includes appropriate testing and validation

procedures in accordance with the rule. Specifically, the person must submit a detailed

description of the means of compliance, a justification for how the means of compliance meets

the minimum performance requirements of the rule, and any substantiating material the person

wishes the FAA to consider as part of the application. FAA-accepted consensus standards are

one way, but not the only way, to show compliance with the performance requirements of this

rule. Accordingly, the FAA encourages consensus standards bodies to develop means of

compliance and submit them to the FAA for acceptance.

3

The FAA indicates acceptance of a means of compliance by notifying the submitter of the

acceptance of the proposed means of compliance. The FAA also expects to notify the public that

it has accepted the means of compliance by including it on a list of accepted means of

compliance at https://www.faa.gov. The FAA will not disclose commercially sensitive

3

A means of compliance is not considered to be “FAA-accepted” until the means of compliance has been evaluated

by the FAA, the submitter has been notified of acceptance, and the means of compliance has been published at

https://www.faa.gov

as available for use in meeting the requirements of part 89.

14

information from the means of compliance that has been marked as such. The FAA may disclose

the non-proprietary broadcast specification and radio frequency spectrum so that sufficient

information is available to develop receiving and processing equipment and software for the

FAA, law enforcement, and members of the public.

See section XIII of this preamble for more information on means of compliance and FAA

acceptance.

In addition, a person responsible for the production of standard remote identification

unmanned aircraft (with limited exceptions) or remote identification broadcast modules is

required to:

• Issue each unmanned aircraft or remote identification broadcast module a serial

number that complies with the ANSI/CTA-2063-A serial number standard.

• Label the unmanned aircraft or remote identification broadcast module to indicate

that it is remote identification compliant.

• Submit a declaration of compliance for acceptance by the FAA, declaring that the

standard remote identification unmanned aircraft or remote identification broadcast

module complies with the requirements of the rule.

A person producing a standard remote identification unmanned aircraft for operation in

the airspace of the United States must comply with the requirements of subpart F of part 89 by

[INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AND 18 MONTHS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE

FEDERAL REGISTER].

A person producing a remote identification broadcast module must comply with the

requirements of subpart F of part 89 by [INSERT DATE 60 DAYS AFTER DATE OF

PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REISTER].

15

See the design and production requirements in section XIV of this preamble for more

information about the production requirements for standard remote identification unmanned

aircraft and remote identification broadcast modules, and the process for declarations of

compliance.

B. Registration Requirements

The FAA proposed requiring all unmanned aircraft, including those used for limited

recreational operations, to obtain a unique registration number. After reviewing comments and

further consideration, the FAA decided not to adopt this requirement. Owners of small

unmanned aircraft used in civil operations (including commercial operations), limited

recreational operations,

4

or public aircraft operations, among others, continue to be eligible to

register the unmanned aircraft under part 48 in one of two ways: (1) under an individual

registration number issued to each unmanned aircraft; or (2) under a single registration number

issued to an owner of multiple unmanned aircraft used exclusively for limited recreational

operations.

The FAA adopts the requirement tying remote identification requirements to registration

requirements and the requirements to submit the unmanned aircraft’s serial number and other

information.

This rule also revises and adopts certain requirements originally established in the interim

final rule on Registration and Marking Requirements for Small Unmanned Aircraft.

5

These

requirements directly affect registration-related proposals made in the Remote Identification of

4

The FAA is revising its regulations and guidance documents to delete references to “model aircraft.” Consistent

with the exception for limited recreational operations of unmanned aircraft in 49 U.S.C. 44809, the FAA now refers

to recreational unmanned aircraft or limited recreational operations of UAS.

5

80 FR 78593.

16

Unmanned Aircraft Systems NPRM. See section XV of this preamble for more information

about registration requirements.

C. Elimination of the Network-Based Remote Identification Requirement

In the NPRM, the FAA proposed requiring standard remote identification UAS and

limited remote identification UAS to transmit remote identification message elements through a

network connection.

6

To comply with this requirement, UAS would have had to transmit the

remote identification message elements through the Internet to a third-party service provider,

referred to as a Remote ID UAS Service Supplier (USS). Remote ID USS would have collected

and, as appropriate, disseminated the remote identification information through the Internet.

In response to the NPRM, the FAA received significant feedback about the network

requirement identifying both public opposition to, and technical challenges with, implementing

the network requirements. The FAA had not foreseen or accounted for many of these challenges

when it proposed using the network solution and USS framework. After careful consideration of

these challenges, informed by public comment, the FAA decided to eliminate the requirement in

this rulemaking to transmit remote identification messages through an Internet connection to a

Remote ID USS.

Without the requirement to transmit remote identification through the Internet, limited

remote identification UAS, as proposed, would have no means to disseminate remote

identification information. As a result, limited remote identification UAS as proposed in the

NPRM are no longer a viable concept. Nonetheless, the FAA recognizes the need for the existing

6

As used in this rule, terms such as “network,” “network-based requirement,” “network solution,” “network

framework,” and “network transmission” typically refer to the transmission of remote identification message

elements through an Internet connection to a Remote ID USS, as proposed in the NPRM.

17

unmanned aircraft fleet to be able to comply with remote identification requirements. To meet

that need, the FAA incorporates a modified regulatory framework in this rule under which

persons can retrofit unmanned aircraft with remote identification broadcast modules.

The FAA’s decision to eliminate the network-based remote identification requirement is

discussed in greater detail in section VII.A of this preamble.

D. Summary of Benefits and Costs

This rule requires remote identification of unmanned aircraft to address safety, security,

and law enforcement concerns regarding the further integration of these aircraft into the airspace

of the United States. The remote identification framework promotes compliance by operators of

unmanned aircraft by providing UAS-specific data, which may be used in tandem with new

technologies and infrastructure to provide airspace awareness to the FAA, national security

agencies, law enforcement entities, and other government officials which can use the data to

discern compliant airspace users from those potentially posing a safety or security risk. In

addition, as being finalized, the rule reduces obsolescence of the existing unmanned aircraft fleet.

This rule results in additional costs for persons responsible for the production of

unmanned aircraft, owners and operators of registered unmanned aircraft, entities requesting the

establishment of an FAA-recognized identification area, and the FAA. This rule provides cost

savings for the FAA from a reduction in hours and associated costs expended investigating

unmanned aircraft incidents.

7

7

This analysis includes quantified savings to the FAA only. A variety of other entities involved with airport

operations, facility and infrastructure security, and law enforcement would also save time and resources involved

with unmanned aircraft identification and incident reporting, response, and investigation.

18

The analysis of this rule is based on the fleet forecast for small unmanned aircraft as

published in the FAA Aerospace Forecast 2020-2040.

8

The FAA forecast includes base, low, and

high scenarios. This analysis provides a range of net impacts from low to high based on these

forecast scenarios. The FAA considers the primary estimate of net impacts of the rule to be the

base scenario. For the primary estimate, over a 10-year period of analysis this rule would result

in present net value costs of about $227.1 million at a three percent discount rate with annualized

net costs of about $26.6 million. At a seven percent discount rate, the present value net costs are

about $186.5 million with annualized net costs of $26.6 million.

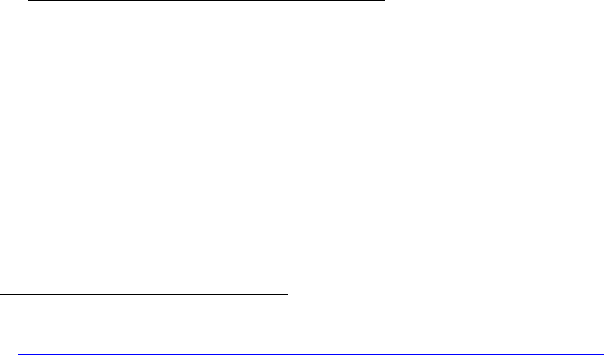

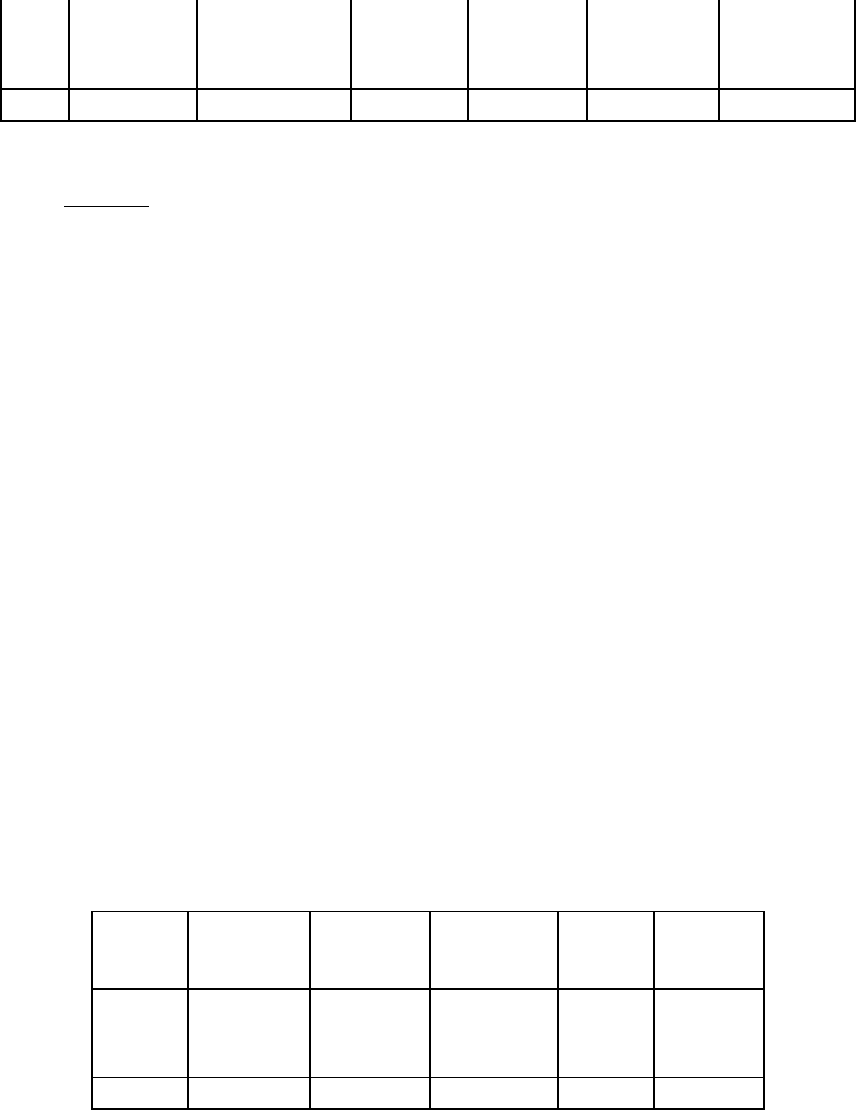

The following table presents a summary of the primary estimates of the quantified costs

and cost savings of this rule, as well as estimates for the low and high forecast scenarios.

Additional details are provided in the Regulatory Evaluation section of this rule and in the

Regulatory Impact Analysis available in the docket for this rulemaking.

Table 1: Costs and Savings of Final Rule ($Millions)*

Forecast Scenario

10 Year

Present

Value (3%)

Annualized

(3%)

10 Year

Present

Value (7%)

Annualized

(7%)

Base Scenario—Primary Estimate

Costs

230.69

27.04

189.38

26.96

Cost Savings

(3.58)

(0.42)

(2.85)

(0.41)

Net Costs

227.11

26.62

186.53

26.56

Low Scenario

Costs

217.08

25.45

178.60

25.43

Cost Savings

(3.47)

(0.41)

(2.77)

(0.39)

Net Costs

213.61

25.04

175.83

25.03

High Scenario

Costs

250.18

29.33

204.90

29.17

Cost Savings

(3.74)

(0.44)

(2.98)

(0.42)

8

FAA Aerospace Forecast Fiscal Years 2020-2040, available at

https://www.faa.gov/data_research/aviation/aerospace_forecasts/media/FY2020-40_FAA_Aerospace_Forecast.pdf

.

The forecast provides a base (i.e., likely) with high (or optimistic) and low (or pessimistic) scenarios.

19

Forecast Scenario

10 Year

Present

Value (3%)

Annualized

(3%)

10 Year

Present

Value (7%)

Annualized

(7%)

Net Costs

246.44

28.89

201.92

28.75

*Table notes: Columns may not sum to total due to rounding. Savings are shown in parenthesis to distinguish from costs.

Estimates are provided at three and seven percent discount rates per Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance.

The final rule incorporates several important changes that reduce costs and provide

additional flexibilities compared to the proposed rule. These include simplifying the approach to

remote identification by requiring only broadcast transmission of data, and authorizing a remote

identification broadcast module option that enables retrofitting of unmanned aircraft that do not

meet the requirements for standard remote identification unmanned aircraft. These changes allow

unmanned aircraft built without remote identification (e.g., existing unmanned aircraft fleet,

home built unmanned aircraft) to be operated outside of FAA-recognized identification areas.

These changes also eliminate the requirement for a person to connect the unmanned aircraft to

the Internet. This shift allows unmanned aircraft with remote identification broadcast modules to

operate in areas where the Internet is unavailable. As a result, the final rule reduces compliance

costs compared to the proposed rule.

The net costs of the final rule have decreased by about 60 percent as compared to the

proposed rule. The NPRM stated that the primary estimate over a 10-year period of analysis for

the proposed rule would have resulted in net present value costs of about $582 million at a three

percent discount rate with annualized net costs of about $68 million. At a seven percent discount

rate, the net present value costs for the proposed rule were about $474 million with annualized

net costs of $67 million.

The FAA expects this rule will result in several important benefits and enhancements to

support safety and security in the airspace of the United States. Remote identification provides

information that helps address existing challenges faced by the FAA, law enforcement entities,

20

and national security agencies responsible for the safety and security of the airspace of the

United States. As unmanned aircraft operations increase, so does the risk of unmanned aircraft

being operated in close proximity to manned aircraft, or people and property on the ground, or in

airspace unsuitable for these operations. Remote identification provides a means to identify these

aircraft and locate the person who controls them (e.g., operators, pilots in command). It allows

the FAA, law enforcement, and national security agencies to distinguish compliant airspace users

from those potentially posing a safety or security risk. It permits the FAA and law enforcement

to conduct oversight of persons operating UAS and to determine whether compliance actions,

enforcement, educational, training, or other types of actions are needed to mitigate safety or

security risks and foster increased compliance with regulations. Remote identification data also

informs the public and users of the airspace of the United States of the local operations that are

being conducted at any given moment.

II. Authority for this Rulemaking

The FAA’s authority to issue rules on aviation safety is found in Title 49 of the United

States Code (49 U.S.C.). Subtitle I, section 106 describes the authority of the FAA

Administrator. Subtitle VII, Aviation Programs, describes the scope of the Agency’s authority.

This rulemaking is promulgated pursuant to 49 U.S.C. 40103(b)(1) and (2), which direct

the FAA to issue regulations: (1) to ensure the safety of aircraft and the efficient use of airspace;

and (2) to govern the flight of aircraft for purposes of navigating, protecting and identifying

aircraft, and protecting individuals and property on the ground. In addition,

49 U.S.C. 44701(a)(5) charges the FAA with promoting safe flight of civil aircraft by prescribing

regulations the FAA finds necessary for safety in air commerce and national security.

21

Section 2202 of Pub. L. 114-190 requires the Administrator to convene industry

stakeholders to facilitate the development of consensus standards for remotely identifying

operators and owners of UAS and associated unmanned aircraft and to issue regulations or

guidance based on any standards developed.

The Administrator has authority under 49 U.S.C. 44805 to establish a process for, among

other things, accepting risk-based consensus safety standards related to the design and

production of small UAS. Under 49 U.S.C. 44805(b)(7), one of the considerations the

Administrator must take into account prior to accepting such standards is any consensus

identification standard regarding remote identification of unmanned aircraft developed pursuant

to section 2202 of Pub. L. 114-190.

In addition, 49 U.S.C. 44809(f) provides that the Administrator is not prohibited from

promulgating rules generally applicable to unmanned aircraft, including those UAS eligible for

the exception for limited recreational operations of unmanned aircraft. Among other things, this

authority extends to rules relating to the registration and marking of unmanned aircraft and the

standards for remotely identifying owners and operators of UAS and associated unmanned

aircraft.

The FAA has authority to regulate registration of aircraft under 49 U.S.C. 44101–44106

and 44110–44113, which require aircraft to be registered as a condition of operation, and to

establish the registration requirements and registration processes.

This rulemaking is also promulgated under the authority described in 49 U.S.C. 106(f),

which establishes the authority of the Administrator to promulgate regulations and rules, and

49 U.S.C. 40101(d), which authorizes the FAA to consider in the public interest, among other

things, the enhancement of safety and security as the highest priorities in air commerce, the

22

regulation of civil and military operations in the interest of safety and efficiency, and assistance

to law enforcement agencies in the enforcement of laws related to regulation of controlled

substances, to the extent consistent with aviation safety.

Finally, this rulemaking is also being issued consistent with DOT’s regulatory policy

which requires that DOT regulations “be technologically neutral, and, to the extent feasible, they

should specify performance objectives, rather than prescribing specific conduct that regulated

entities must adopt.”

9

III. Background

The rapid proliferation of unmanned aircraft has created significant opportunities and

challenges for their integration into the airspace of the United States. The relatively low cost of

highly capable UAS technology has allowed for hundreds of thousands of new operators to enter

the aviation community.

The complexities surrounding the full integration of UAS into the airspace of the United

States have led the FAA to engage in a phased, incremental, and risk-based approach to

rulemaking based on the statutory authorities delegated to the Agency. On December 16, 2015,

the Administrator and Secretary jointly published an interim final rule in the Federal Register

titled Registration and Marking Requirements for Small Unmanned Aircraft (“Registration

Rule”),

10

which provides for a web-based aircraft registration process for small unmanned

aircraft in 14 CFR part 48 that serves as an alternative to the registration requirements for aircraft

established in 14 CFR part 47. The Registration Rule imposes marking requirements on small

9

49 C.F.R. § 5.5(e).

10

80 FR 78594.

23

unmanned aircraft registered under part 48, according to which the small unmanned aircraft must

display a unique identifier in a manner that is visible upon inspection. The unique identifier

could be the registration number issued to an individual or to the small unmanned aircraft by the

FAA Registry or the small unmanned aircraft’s serial number if authorized by the Administrator

and provided with the application for the certificate of aircraft registration.

On June 28, 2016, the FAA and DOT jointly published the final rule for Operation and

Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (“The 2016 Rule”) in the Federal Register.

11

This was an important step towards the integration of civil small UAS operations (for aircraft

weighing less than 55 pounds) into the airspace of the United States. The 2016 Rule set the initial

operational structure and certain restrictions to allow routine civil operations of small UAS in the

airspace of the United States in a safe manner. Prior to the 2016 Rule, the FAA authorized

commercial UAS operations, including but not limited to real estate photography, precision

agriculture, and infrastructure inspection, under section 333 of Pub. L. 112-95. Over 5,500

operators received this authorization. The FAA also issued over 900 Certificates of Waiver or

Authorization (COA), allowing Federal, State, and local governments, law enforcement

agencies, and public universities to perform numerous tasks with UAS, including but not limited

to search-and-rescue, border patrol, and research activities. The 2016 Rule allows certain

operations of small UAS to be conducted in the airspace of the United States without an

airworthiness certificate, exemption, or COA.

The 2016 Rule also imposed certain restrictions on small UAS operations. The

restrictions included a prohibition on nighttime operations, limitations on operations conducted

11

81 FR 42064.

24

during civil twilight, restrictions on operations over people, a requirement for all operations to be

conducted within visual line of sight, and other operational, airspace, and pilot certification

requirements. Since the 2016 Rule took effect on August 29, 2016, most low-risk small UAS

operations that were previously authorized on a case-by-case basis under section 333 of Pub. L.

112-95 became routine operations. With some exceptions,

12

these operations are now permitted

without further interaction with the FAA if they comply with the requirements of part 107.

Publishing part 107 was the first significant regulatory step to enable lower risk, less complex

UAS operations in the airspace of the United States.

Part 107 opened the airspace of the United States to the vast majority of routine small

UAS operations, allowing flight within visual line of sight while maintaining flexibility to

accommodate future technological innovations. Part 107 allows individuals to request waivers

from certain provisions, including those prohibiting operations over people and beyond visual

line of sight. Petitions for waivers from the provisions of part 107 must demonstrate that the

petitioner has provided sufficient mitigations to safely conduct the requested operation.

On October 5, 2018, Congress enacted Pub. L. 115-254, also known as the FAA

Reauthorization Act of 2018. The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 amended part A of

subtitle VII of title 49, United States Code by inserting a new chapter 448 titled Unmanned

Aircraft Systems and incorporating additional authorities and mandates to support the further

integration of UAS into the airspace of the United States, including several provisions that

specifically deal with the need for remote identification of UAS. Section 376 of the FAA

Reauthorization Act of 2018 requires the FAA to perform testing of remote identification

12

See, e.g., 14 C.F.R. § 107.41 (requiring prior FAA authorization for small unmanned aircraft operation in certain

types of airspace).

25

technology, and to assess the use of remote identification for the development of unmanned

aircraft systems traffic management (UTM).

Additional congressional action supports the implementation of remote identification

requirements for most UAS. Section 349 of the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 goes so far as

to indicate that the Administrator may promulgate rules requiring remote identification of UAS

and apply those rules to UAS used for limited recreational operations.

13

The provision denotes

Congress’ acknowledgment that remote identification is an essential part of the UAS regulatory

framework.

On February 13, 2019, the FAA published three rulemaking documents in the Federal

Register as part of the next phase of integrating small UAS into the airspace of the United States.

The first of such documents was an interim final rule titled External Marking Requirement for

Small Unmanned Aircraft,

14

in which the FAA required small unmanned aircraft owners to

display the registration number assigned by the FAA on an external surface of the aircraft. The

second rulemaking document was a notice of proposed rulemaking titled Operation of Small

Unmanned Aircraft Systems Over People,

15

in which the FAA proposed to allow operations of

small unmanned aircraft over people in certain conditions and operations of small UAS at night

without obtaining a waiver. The third rulemaking document was an advance notice of proposed

rulemaking titled Safe and Secure Operations of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems,

16

in which

the FAA sought information from the public on whether, and under which circumstances, the

13

See 49 U.S.C. 44809.

14

84 FR 3669.

15

84 FR 3856.

16

84 FR 3732.

26

FAA should promulgate new rules to require stand-off distances, additional operating and

performance restrictions, the use of UTM, additional payload restrictions, and whether the

Agency should prescribe UAS design requirements and require that unmanned aircraft be

equipped with critical safety systems.

On December 31, 2019, the FAA published the Remote Identification of Unmanned

Aircraft Systems NPRM. The FAA received approximately 53,000 comments on the NPRM. A

significant amount of the comments were submitted by individuals, many of whom identified as

recreational flyers. In addition, the FAA received numerous comments from UAS manufacturers,

other aviation manufacturers, organizations representing UAS interest groups, organizations

representing various sectors of manned aviation, State and local governments, news media

organizations, academia, and others.

IV. Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft

A. Clarification of Use of the Term Unmanned Aircraft in this Rule

As a result of the comments concerning the use of the term unmanned aircraft system

(UAS), the FAA clarifies that the term “unmanned aircraft” is used when referring to the aircraft,

and UAS is used when referring to the entire system, including the control station.

The FAA acknowledges that UAS may have components produced by different

manufacturers (e.g., an unmanned aircraft could be manufactured by one manufacturer and the

control station could be manufactured by another). In addition, unmanned aircraft that operate

beyond the range of the radio signal being transmitted from the control station may use third-

party communication links, such as the cellular network. As finalized, the remote identification

requirements in this rule apply to the operation, and the design and production of unmanned

27

aircraft. Unmanned aircraft producers are responsible for ensuring that the unmanned aircraft

comply with the design and production requirements of this rule even when the unmanned

aircraft uses control station equipment (such as a smart phone) or communication links

manufactured by a different person. The unmanned aircraft producer must address how any

dependencies on control station functionality are incorporated as part of the remote identification

design and production requirements.

B. Purpose for the Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft

UAS are fundamentally changing aviation and the FAA is committed to working to fully

integrate them into the airspace of the United States. The next step in that integration is enabling

unmanned aircraft operations over people and at night. Remote identification of unmanned

aircraft is a critical element to enable those operations that addresses safety and security

concerns.

Remote identification is the capability of an unmanned aircraft in flight to provide

identification, location, and performance information that people on the ground and other

airspace users can receive. In its most basic form, remote identification can be described as an

electronic identification or a “digital license plate” for UAS.

Remote identification provides information that helps address existing challenges of the

FAA, law enforcement entities, and national security agencies responsible for the safety and

security of the airspace of the United States. As a wider variety of UAS operations such as

operations over people are made available, the risk of unmanned aircraft being operated in an

unsafe manner, such as in close proximity to people and property on the ground, is increased.

Remote identification provides a means to identify these aircraft and locate the person who

controls them (e.g., operators, pilots in command). It allows the FAA, law enforcement, and

28

national security agencies to distinguish compliant airspace users from those potentially posing a

safety or security risk. It permits the FAA and law enforcement to conduct oversight of persons

operating unmanned aircraft and to determine whether compliance actions, enforcement,

educational, training, or other types of actions are needed to mitigate safety or security risks and

foster increased compliance with regulations.

The requirements for the identification of manned and unmanned aircraft form an integral

part of the FAA’s regulatory framework. Prior to this rule, the requirements included aircraft

registration and marking and electronic identification using transponders and Automatic

Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B). This rule creates a new regulation, 14 CFR part 89,

which establishes the remote identification requirements for unmanned aircraft. These

requirements are particularly important for unmanned aircraft because the person operating the

unmanned aircraft is not onboard the aircraft, creating challenges for associating the aircraft with

its operator. In addition, the small size of many unmanned aircraft means the registration

marking is only visible upon close inspection, making visual identification of unmanned aircraft

in flight difficult or impossible.

As discussed in the NPRM, the remote identification framework is necessary to enable

expanded UAS operations and further integration. This final rule scales that framework to

support the next steps in that integration: operations over people and operations at night. Though

the NPRM discussed remote identification as a building block for UAS Traffic Management

(UTM), the FAA has determined that, at this time, this rule will only finalize the broadcast-based

remote identification requirements. See section VII.A of this preamble for a discussion on the

FAA’s decision to eliminate network-based remote identification requirements at this time. The

29

broadcast-based approach of this rule contains the minimum requirements necessary to allow for

remote identification of unmanned aircraft under the current operational rules.

C. Public Comments and FAA Response

1. General Support for Remote Identification

Comments: Many commenters expressed general support for the NPRM, including the

Helicopter Association International, the League of California Cities, and, commenting jointly,

the Michigan Department of Transportation Office of Aeronautics, Michigan Aeronautics

Commission, and Michigan Unmanned Aircraft Systems Task Force. Most commenters in

support of the rule cited improvements to safety and privacy. Commenters expressed that with

UAS becoming increasingly widespread, the rule would make identification easier, increase the

safety of airspace, particularly for manned aircraft operating at the same altitudes as unmanned

aircraft, and protect citizens’ privacy.

17

The International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions supported the rule,

stating that the rule would enhance situational awareness and foster accountability of the

operator and improved knowledge for the FAA, law enforcement, and operators of certain

facilities identified by Congress in section 2209 of the FAA Extension, Safety and Security Act

of 2016.

18

The Edison Electric Institute, American Public Power Association, and National Rural

Electric Association, commenting jointly, expressed support for the rule and for FAA’s real-time

17

Though remote identification potentially allows for greater ability of law enforcement to locate the person

controlling an unmanned aircraft, this rule has not been promulgated for the purpose of addressing concerns about

unmanned aircraft that violate privacy laws.

18

Section 2209 requires “the Secretary of Transportation to establish a process to allow applicants to petition the

Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration to prohibit or restrict the operation of an unmanned aircraft in

close proximity to a fixed site facility.” The FAA Extension, Safety and Security Act of 2016, Pub. L. No. 114-

190, § 2209, 130 Stat. 615, 633-635 (2016).

30

access to UAS location information, particularly over energy infrastructure. Various institutions

of higher education expressed support for remote identification and mentioned it would assist

law enforcement agencies affiliated with said institutions to better identify UAS operators,

particularly where the UAS poses risk or nuisance to bystanders, facilities, or other aircraft.

The National Transportation Safety Board stated it had no technical objections provided

the FAA can ensure that remote identification functions do not interfere with aviation safety.

FAA Response: The FAA acknowledges the support of commenters and finalizes this rule

and related policies to implement a remote identification framework that provides near-real time

information regarding unmanned aircraft operations and increases situational awareness of

unmanned aircraft to the public, operators of other aircraft, law enforcement and security

officials, and other related entities.

2. General Opposition to Remote Identification

The FAA received a multitude of comments opposing remote identification. Many of the

commenters opposed the concept, as a whole, while others expressed opposition to specific

aspects, concepts, or proposed in the NPRM.

Comments: Among the comments expressing general disagreement with the proposed

rule was one of the two form letters written and submitted by the First Person View Freedom

Coalition (FPVFC) and 90 of its members. The commenters argued that the proposed rule would

have many negative effects, including destroying the hobby of building and flying recreational

remote controlled aircraft, making the sport of drone racing illegal, ending the “multi-million

[dollar] cottage industry around home built drones,” outlawing “acrobatic drone videography,”

imposing costs on both hobbyists and the drone industry by making current fleets obsolete, and

making criminals of hobbyists. These commenters asked the FAA to rewrite the proposed rule

31

with input from the FPVFC and Academy of Model Aeronautics (AMA). Similar concerns were

common among many other commenters who opposed the NPRM in general terms. Instead of

finalizing the rule as proposed, a member of the executive board for the AMA suggested the

FAA adopt a “technology agnostic” approach to remote identification, so a variety of technical

solutions could be used to meet the remote identification needs.

The most common objections to the proposed rule were that it would impose burdens and

costs that would make it difficult or impossible for hobbyists to fly model aircraft; that it would

impose an unnecessary financial burden on UAS or model aircraft owners; and that it would

harm or end the recreational UAS hobby. Commenters noted that it would be very difficult to

upgrade many existing UAS because of the burden of carrying and powering new equipment

such as navigation receivers and remote identification transmitters. They argued that this would

reduce available flight time and could affect safety of operations if the additional weight is

excessive. The FPVFC form letter and many other comments included similar objections.

Many commenters, including 33 persons who submitted a form letter addressed as the

“Traditional Hobbyist Form Letter Campaign,” argued that the proposed rule would not achieve

its objectives of providing safety for the airspace of the United States and protecting national

security. Many of these commenters questioned whether the FAA provided an adequate

justification for the proposed rule, with many commenters stating the FAA has not demonstrated

that UAS are dangerous. The commenters questioned the need for the rule, often stating that

existing regulations and standards are sufficient for protecting public safety. They mentioned that

historically UAS have not been dangerous and have not caused fatalities and indicated the FAA

should concentrate on enforcing current rules. A related and separate statement repeatedly made

by commenters was that model aircraft are not dangerous. These comments often distinguish

32

between model aircraft and other UAS, stating that model aircraft are not dangerous because

they must remain in the pilot’s visual line of sight to stay airborne due to lack of navigation

equipment, flight planning capability, flight stabilization, first person view capability, or

automation that is common on newer UAS. Some commenters saw the proposed rule as an

attempt to privatize the airspace in which UAS and model aircraft operate.

Commenters indicated remote identification would have negative effects. Many stated the

proposed rule would harm innovation in the UAS industry. Others believed it would harm the

educational and research potential of UAS or model aviation. Commenters pointed to model

aviation driving young people’s interest in science, technology, engineering, and math fields and

aviation; and providing educational benefits that relate to these fields. Those commenters

believed the rule would contribute to exacerbating a national shortage of manned aircraft pilots.

Many commenters believed the rule would be unenforceable. A related argument was

that only lawful flyers would follow the rules and that the rule would do nothing to change the

behavior of bad actors. Some expressed concerns for widespread noncompliance with the rule.

A significant number of commenters opposed any regulation of UAS used for

recreational operations.

A number of commenters believed remote identification requirements for UAS are

stricter than ADS-B Out or transponder requirements for manned aircraft. Several commenters

suggested permitting UAS operations without remote identification in uncontrolled airspace and

away from airports, similar to the requirements for ADS-B Out that only apply in certain

airspace. Commenters also stated that manned aircraft should be required to broadcast ADS-B

Out in all airspace if all UAS are required to transmit remote identification. Several commenters

also noted that manned aircraft were offered grants and rebates to help cover the cost of ADS-B

33

implementation and had over 10 years to equip for ADS-B Out compared to the shorter

implementation time proposed for remote identification.

FAA Response: The FAA acknowledges the significant number of comments opposing

the proposed regulation and related policies. After further consideration of public comments, the

FAA has modified some of the remote identification policies in the final rule, as further

discussed throughout this preamble, to reduce the burdens on unmanned aircraft operators and

producers while maintaining the necessary requirements to address the safety and security needs

of the FAA, law enforcement, and national security agencies. The FAA does not agree with

commenters who believed remote identification will harm innovation in the UAS industry. On

the contrary, the Agency believes that this performance-based regulation provides opportunities

for innovation and growth of the UAS industry by addressing the security concerns associated

with unmanned aircraft flight at night and over people. In addition, the FAA does not agree that

the remote identification requirements are stricter than ADS-B Out requirements. Remote

identification has fewer technical requirements compared to ADS-B, and this rule provides

accommodations for unmanned aircraft operations without remote identification.

The FAA does not agree that the requirements of this rule are unenforceable. In fact, the

enforcement mechanism for this rule will in many respects parallel existing regulatory

compliance activities for manned aviation. The Agency intends to meet its statutory and

regulatory compliance and enforcement responsibilities by following a documented compliance

and enforcement program that includes legal enforcement action, including civil penalties and

certificate actions, as appropriate, to address violations and help deter future violations.

Many commenters opposed remote identification because they believed it would impact

the recreational UAS community. The remote identification requirements apply to unmanned

34

aircraft operating in the airspace of the United States irrespective of what the unmanned aircraft

are being used for. However, the FAA has incorporated additional flexibilities into this rule to

facilitate compliance with the remote identification requirements. For example, an operator of an

unmanned aircraft without remote identification can now retrofit the unmanned aircraft with a

remote identification broadcast module to identify remotely. See section VII.D of this preamble

for further discussion of remote identification broadcast modules.

The Agency has also eliminated the requirement to transmit remote identification

message elements through the Internet to a Remote ID USS, which will decrease costs to

operators by eliminating the potential for subscription fees. See section VII.A of this preamble

for further discussion on the elimination of the limited remote identification UAS concept. The

revised rule also increases the availability of FAA-recognized identification areas where

operations may occur without remote identification equipment. See section XII of this preamble

for further discussion on FAA-recognized identification areas. The FAA also revised the

definition of amateur-built UAS as discussed in section V.D of this preamble. The term is now

addressed in this rule as home-built unmanned aircraft.

3. Alternatives proposed by commenters

Many commenters, including the Academy of Model Aeronautics, AirMap, American

Farm Bureau Federation, the Experimental Aircraft Association, Flite Test, Kittyhawk, and the

Small UAV Coalition noted that the best path to widespread compliance is a simple, affordable

solution. They recommended an application-based interface that would permit a UAS operator to

self-declare an operational area and time either at the beginning, or in advance of, operations in

areas where Internet service might not be available, similar to current LAANC implementations.

Some commenters suggested either a smart phone application or phone-in option where UAS

35

operators could reserve a small block of airspace so other non-participating UAS could

voluntarily re-route around that operations area.

The Academy of Model Aeronautics recommended providing a path to compliance using

ground-based or application-based remote identification for the pilot in command rather than

specific equipment mandates applicable to manufacturers. For non-autonomous UAS which

require continuous pilot input and visual line of sight (e.g., no programmable waypoints or other

automation), the Charles River Radio Controllers also recommended a pre-flight registration via

the Internet where operators would indicate their destination, flight parameters, and time of

operation. Streamline Designs suggested permitting UAS that self-report location to operate in

rural locations.

Wing Aviation suggested revising limited remote identification UAS to permit

recreational operations within VLOS for UAS that are not highly automated and not available for

sale to third parties, provided that operators declare their operational intent to a Remote ID USS.

The intent information would include the flight area, maximum height AGL, earliest and latest

operations times, and the actual or expected location of the ground control station, while also

requiring the operator to share actual control station location if the Internet is available. SenseFly

also supported uploading a flight plan and stated that this type of identification would give

adequate information, especially for a short-range flight, such as those limited to a 400-foot

range. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce Technology Engagement Center recommended

permitting remote identification UAS to continue to operate without a persistent connection to a

Remote ID USS if operators declare their identifier and flight intent to provide situation

awareness for other airspace users.

36

Kittyhawk stated that network-based solutions are the most agile, scalable, and

information-rich, but also recommended providing a variety of options to better achieve remote

identification compliance. They proposed a three-tier solution that would permit volume-based

reservations without requiring network or broadcast remote identification information for UAS

operations in VLOS below 200 feet in Class G airspace and 100 feet in controlled airspace, as

well as UAS operations within VLOS below 400 feet with volume-based reservations and

transmission of remote identification information by either broadcast or network.

One commenter suggested permitting the installation of Broadcom chips in UAS so they

could be tracked similar to cellular phones. One commenter suggested the FAA supply RFID

tags to track each UAS for a fee upon completion of their UAS knowledge test. Several

commenters, including the American Property Casualty Insurance Association, suggested remote

identification data could be stored locally and uploaded after flight in areas with no Internet

coverage. The New Hampshire Department of Transportation assumed that many retrofit UAS

would become limited remote identification UAS and recommended permitting those UAS to

operate when the Internet is not available if equipped with an anti-collision beacon that is visible

for at least 3 statute miles to increase conspicuity for manned aircraft.

FAA Response: The FAA considered the alternative approaches proposed by commenters

and assessed whether they met the needs of the FAA, law enforcement, and national security

agencies to ensure the safety and efficiency of the airspace of the United States sufficient to

enable unmanned aircraft to fly over people and at night. The Agency agrees with commenters

that a retrofit option could enable operators to meet the remote identification requirements of this

rule. Therefore, the FAA adopts the concept in this rule by incorporating operating requirements,

discussed in section VII.D of this preamble, and production requirements, discussed in section

37

XIV.E.3 of this preamble, to permit the production and use of remote identification broadcast

modules. A person may now equip an unmanned aircraft without remote identification with a

remote identification broadcast module to enable the unmanned aircraft to identify remotely.

At this time, the FAA has determined that the other options proposed by commenters do

not meet the needs of the Agency or are outside the scope of this rule. For example, the volume-

based reservation proposal from Kittyhawk would affect airspace access and is outside the scope

of identification. The FAA declines to require the installation of Broadcom chips as suggested by

one commenter because the FAA is committed to performance-based requirements that do not

require using a specific manufacturer’s equipment. The recommendation to require unmanned

aircraft to be equipped with anti-collision lighting when not transmitting remote identification

information is unacceptable because it does not provide information about the identity of the

unmanned aircraft or the control station location. The FAA also notes that providing flight intent

information as a means to satisfy the remote identification requirements would not ensure that

flight information is available in areas where there is no Internet connectivity. However, the

remote identification broadcast requirements in this rule ensure that remote identification

information is available even in areas where the Internet may not be available.

V. Terms Used in this Rule

The NPRM proposed to define a number of terms to facilitate the implementation of the

remote identification of unmanned aircraft. In part 1, definitions and abbreviations, the FAA

proposed to add definitions of unmanned aircraft system and visual line of sight to § 1.1. The

FAA also proposed several definitions to be included in § 89.1, including the definitions for

broadcast, amateur-built unmanned aircraft system, and Remote ID USS.

38

A. Definition of Unmanned Aircraft System

1. Discussion of the Final Rule

The FAA proposed that the term unmanned aircraft system (UAS) means an unmanned

aircraft and its associated elements (including communication links and the components that

control the unmanned aircraft) that are required for the safe and efficient operation of the

unmanned aircraft in the airspace of the United States. The FAA adopts the term “unmanned

aircraft system” as proposed.

2. Public Comments and FAA Response

Comments: Many commenters suggested that the definition be changed for a variety of

reasons including a need to distinguish between various categories of UAS, particularly to

distinguish between drones, quadcopters, and remote control model aircraft. Commenters raised

issues such as the interchangeable nature of home-built kits and models with interchangeable

parts. Commenters also cited a lack of clarity regarding when the communication links are

considered part of the UAS. In addition, some commenters stated the definition of UAS was not

detailed enough and recommended it be amended to list the specific components that are

covered.

FAA Response: Congress established the definition of unmanned aircraft system in

49 U.S.C. 44801(12). Therefore, the FAA adopts the definition of unmanned aircraft system as

proposed. The FAA also considers that any kit containing all the parts and instructions necessary

to assemble a UAS would meet this definition. As further explained in section XIV.B.2 of this

preamble, producers of complete kits offered for sale are subject to the production requirements

of this rule.

39

B. Definition of Visual Line of Sight

1. Discussion of the Final Rule

The FAA proposed that the term visual line of sight means the ability of a person

manipulating the flight controls of the unmanned aircraft or a visual observer (if one is used) to

see the unmanned aircraft throughout the entire flight with vision that is unaided by any device

other than corrective lenses. The FAA recognized that this definition is consistent with how

“visual line of sight” is currently used in part 107. The term is specifically described in

§ 107.31(a). The FAA proposed that because visual line of sight will now be used in multiple

parts, providing a definition in § 1.1 would ensure that the term is used consistently throughout

all FAA regulations. To account for the use of the term in proposed part 89 and the potential use

of the term in other parts of 14 CFR, the FAA proposed to include a slightly modified version of

the description used in part 107.

The FAA will not be adopting the definition in this rule because the concept may apply

differently to various persons and conditions depending upon the type of operation. In addition,

future rules, such as rules providing for routine unmanned aircraft BVLOS operations, may need

to describe visual line of sight in a different manner or context in order to establish the difference

between VLOS and BVLOS operations.

2. Public Comments and FAA Response

Comments: An individual commenter noted that the maximum distance one can operate

under visual line of sight varies based on several factors such as the size and speed of the

aircraft, terrain, and weather.

FAA Response: As noted, the FAA has determined not to adopt a definition for “visual

line of sight” in this rule. The FAA recognizes that the concept of visual line of sight allows for

40

variation in the distance to which an unmanned aircraft may fly and still be within visual line of

sight of the person manipulating the flight controls of the UAS or the visual observer. The FAA

believes this is appropriate given the performance-based nature of current UAS regulations.

C. Definition of Broadcast

The FAA proposed to define broadcast in part 89 to mean “to send information from an

unmanned aircraft using radio frequency spectrum.” The definition was necessary to distinguish