Family Seating in Air Transportation

Regulatory Impact Analysis

RIN 2105-AF15

Office of the General Counsel, Office of Regulation and Legislation

July 2024

U.S. Department of Transportation

Office of the General Counsel

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 1

Executive summary

This regulatory impact analysis evaluates the benefits, costs, and transfers associated with a

Department of Transportation proposed rule to require air carriers to seat children aged 13 and

under next to at least one accompanying adult without charging a separate seating fee. The

proposed rule meets the threshold for a significant regulatory action as defined in section

(3)(f)(1) of Executive Order (E.O.) 12866, “Regulatory Planning and Review,” as amended by E. O.

14094, “Modernizing Regulatory Review,” because it is likely to have an annual effect on the

economy of $200 million or more.

Table ES-1 provides a summary of the economic analysis. Benefits, which we did not quantify,

are due to the reduction in disutility to passengers from separation of families traveling by air.

Families can be reassured that they will be seated together during air travel. Some families

could experience a reduction in stress and anxiety associated with air travel. Passengers who do

not travel with children will no longer be burdened with being seated next to children who are

separated from their parents. Airlines will incur implementation costs, which are quantified.

Because benefits are not quantified, it is not possible to estimate net benefits.

Most quantifiable economic impacts are transfers, which are benefits and costs that have exactly

offsetting effects and do not contribute to the net benefits calculation. The total price of air

travel for families who currently purchase seat reservations will decrease, which creates a

transfer of consumer surplus to them. The elimination of seating fees for families encourages

additional travel and airfares will increase. Solo passengers and families who do not currently

purchase seat reservations will lose consumer surplus due to the airfare increase. The increase

in in airfare offsets the increase in consumer surplus to families who pay for seat reservation in

the baseline, but the effect is small. Airlines initially will incur revenue losses as well.

An important determinant of the quantifiable impacts is the percentage of passengers who

purchase seat assignments in the baseline. This percentage is not known with certainty, and we

apply market research that suggests about 37 percent of consumers might be willing to pay for

a seat reservation. The 37 percent is applied to the estimated 9.7 percent of passengers who

travel as families as well as the remaining 90.3 percent of passengers who travel solo.

Evaluation of the transfers created by the proposed rule provide insight into its distributional

consequences. There is a gain in consumer surplus to families due to elimination of their

seating fees and a loss in consumer surplus to other passengers from higher fares. We estimate

that that the proposed rule would initially reduce airline revenue by about $85 million in the first

year after full implementation.

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 2

Table ES-1: Summary of economic impacts, first year (2022$, millions)

Benefits (+)

Reduced disutility to passengers from separation

of families traveling by air

Unquantified

Costs (-)

Implementation costs

$5-21

Net societal benefits (costs)

Not applicable

Transfers (0)

Increase in consumer surplus from elimination of

seating fees for families (airlines to families)

$910

Decrease in consumer surplus for solo air

passengers (solo passengers to airlines)

$760

Decrease in consumer surplus for families who do

not pay for seat reservations in the baseline

(families to airlines)

$51

Airline revenue loss (airlines to consumers)

$85

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 3

Contents

1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 4

2 Need for regulation ................................................................................................................................ 4

3 Requirements of the proposed rule .................................................................................................... 5

4 Baseline for the analysis ......................................................................................................................... 6

4.1 Current family seating policies ................................................................................................................ 6

4.2 Airline passengers who travel as families ............................................................................................ 8

4.3 Seating fee revenue and charges ........................................................................................................... 9

5 Economic impacts of the proposed rule ...........................................................................................11

5.1 Framework for analysis ............................................................................................................................ 11

5.2 Price effects .................................................................................................................................................. 14

5.3 Benefits .......................................................................................................................................................... 16

5.4 Costs ............................................................................................................................................................... 17

5.5 Transfers ........................................................................................................................................................ 21

5.5.1 Consumer surplus gains for families who currently pay for seat reservations .......... 21

5.5.2 Reduction in consumer surplus due to airfare increases................................................... 21

5.5.3 Revenue effects ................................................................................................................................. 22

5.6 Comparison of benefits and costs ....................................................................................................... 22

5.7 Additional impacts .................................................................................................................................... 22

5.8 Sensitivity analysis ..................................................................................................................................... 24

6 Regulatory alternatives ....................................................................................................................... 24

6.1 No action ...................................................................................................................................................... 24

6.2 Guaranteed family seating without fee restrictions ...................................................................... 25

7 Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 25

Appendix A Implementation cost estimates at 3 and 7 percent discount rates ......................... 27

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 4

1 Introduction

This rulemaking would amend 14 CFR Part 259, Enhanced Protections for Airline Passengers, to

require air carriers to seat children aged 13 and under next to at least one accompanying adult

without charging a separate seating fee. This final rule meets the threshold for a significant

regulatory action as defined in 3(f)(1) of E.O. 12866, “Regulatory Planning and Review

,”

1

and

amended by E.O. 14094, “Modernizing Regulatory Review”

2

because it is likely to “have an

annual effect on the economy of $200 million or more.” This regulatory impact analysis (RIA)

evaluates benefits, costs, and other economic effects of the rule.

In conducting this analysis, the Department engaged an expert in the economics of the airline

industry, and this RIA draws heavily from the expert analysis. Specifically, we asked the expert to

identify primary economic impacts, quantify key values needed to evaluate those economic

impacts, and provide a quantitative analysis of the primary impacts to consumers and airlines of

a policy that prohibits airlines from charging a fee for families to be seated together. The expert

report (“expert report”) has been added to the rulemaking docket.

3

2 Need for regulation

The Department views family seating as a basic service that should be provided to passengers

without a separate fee for advance seat selection. Most airlines say that their gate agents and

flight crew will attempt to seat families together during the boarding process, but not all

guarantee family seating unless travelers have purchased seat assignments in advance or

purchased a fare with seat assignment included. Airlines often recommend that families who

need to be seated together consider paying the advance seat assignment fee to be assured of

adjacent seating. The Department is concerned about the stress and anxiety experienced by

families when they are not able to ensure family seating in advance of travel.

Many U.S. airlines offer basic economy, or another equivalent low-cost ticket that comes with

more limitations than a standard economy ticket. These low-cost economy ticket options may

not allow passengers to select a specific seat assignment. If a passenger wants to ensure a

specific seat assignment in advance of the flight, such as a window or aisle seat or being next to

a child, many carriers advise consumers who purchase low-cost economy tickets to either pay an

advance seat assignment selection fee, or purchase seats in a higher fare class that permits the

passenger to select a seat assignment. Most carriers have indicated to the Department that they

1

https://archives.federalregister.gov/issue_slice/1993/10/4/51724-51752.pdf#page=12

2

https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/04/11/2023-07760/modernizing-regulatory-review

3

Forbes, Silke (October 2023). “Expert Report on the Current Status of Family Seating Fees and the

Potential Economic Impacts of a Prohibition.”

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 5

would try to make accommodations at the airport to ensure that families are seated together,

regardless of the fare purchased by the passenger. Nonetheless, passengers who purchase low-

fare economy tickets for their family have reported having trouble when attempting to obtain

family seating at the gate.

Not all passengers are willing to pay the seating fees that airlines charge for a seat assignment.

Some passengers have no need for a specific seating arrangement, but some may be unaware

that the ticket purchased does not include a specific seat assignment. An Ipsos survey carried

out on behalf of Airlines for America in January 2023 asked participants who had purchased a

fare that did not include carry-on baggage or seat selection if they were aware these services

would have additional charges.

4

Of the respondents, only 85 percent said that they were fully

aware meaning that a significant minority of consumers was unaware of the additional charges

for services like carry-on baggage or seat assignment. This suggests that lack of information

could contribute to family seating problems.

Families who do not have prior seating arrangements, either because they are unaware of airline

seating policies or believed that they would be seated together despite having chosen not to

pay for a seat assignment, could experience stress or anxiety if they arrive at the gate to find

that they are seated away from a child. Other passengers might be burdened by being seated

next to children who are separated from their parents and might need assistance. Even where

accommodations can be made at the gate or onboard the aircraft to allow families without

advance seat assignments to sit together, doing so may require other passengers to give up

their seat for another, potentially less desirable one, imposing a cost on those travelers. The seat

switching process also creates a transaction cost on all parties involved that could be avoided if

the family had been assigned seats together. Some effects of airline family seating policies are

not fully internalized in the market and are a potential source of market failure.

3 Requirements of the proposed rule

This rulemaking would amend 14 CFR Part 259, Enhanced Protections for Airline Passengers, to

require U.S. and foreign air carriers to seat children aged 13 and under next to at least one

accompanying adult without a separate charge. There are certain limited exceptions, for

example, if the number of children on the reservation makes compliance not possible. The

proposed rule requires carriers to disclose their family seating policies clearly on their public-

facing websites and over the phone and to provide instructions for consumers to secure family

seating. The disclosure must include any check-in or boarding requirements that might impact

a family’s ability to be seated together.

4

See https://www.airlines.org/dataset/air-travelers-in-america-annual-survey/ .

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 6

The proposed rule also provides for the case where family seating is unavailable at the time of

booking. If the flight is purchased more than 2 weeks before departure, airlines must give

passengers the option within 7 days to receive a refund or wait for available family seating. If the

flight is purchased less than 2 weeks before departure, the airline must give passengers the

same options as soon as practicable after the ticket has been purchased. In the event an airline

is unable to provide adjacent seating, the proposed rule would require airlines to provide an

accompanying adult the choice of:

• rebooking on the next available flight with adjacent seats for the young child and an

accompanying adult as well as any other person on the same reservation;

• a full refund of the cost of the tickets for the young child and an accompanying adult

as well as any other person on the same reservation; or

• continuing their original transportation without adjacent seats.

The proposed rule also defines an open seating carrier as a carrier that does not assign seats or

does not allow an individual to select seats on a flight in advance of the date of departure of the

flight. Open seating carriers would be required to board passengers in a manner that allows for

family seating.

4 Baseline for the analysis

4.1 Current family seating policies

Several U.S. carriers have implemented family seating policies that allow young children to be

seated next to an adult traveling on the same reservation. All carriers have posted statements

saying that they will make an effort to seat families together, but not all of them guarantee that

families will be seated together in all circumstances. Frontier, American, Alaska Airlines, and

JetBlue are U.S. carriers that guarantee family seating. Among the largest foreign carriers,

several guarantee advance seat reservations at no additional charge for young children and an

adult traveling on the same reservation. Some foreign carriers have no information on family

seating available on their U.S. websites.

Table 4-1 provides a summary of family seating policies for U.S. carriers. Together, these airlines

and their operating partners accounted for approximately 85 percent of domestic passenger air

traffic in 2022. American, Alaska, JetBlue, Delta, Hawaiian, and United offer several different fare

classes: Basic Economy, Economy, Premium Economy, and First/Business Class. However, some

of these airlines do not offer Basic Economy and Premium Economy on all itineraries. Except for

Basic Economy, seat

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 7

Table 4-1: Overview of family seating policies of major U.S. carriers

Airline Statement on family seating

Alaska Airlines “Alaska guarantees that children 13 and under will be seated with at least one

accompanying adult, subject to certain conditions. Please contact us or check with an

airport agent as soon as possible to review available seating options.”

Allegiant Air “While we will do our best to accommodate families, the availability of seats together

cannot be guaranteed. To ensure that your party is seated together, we recommend

reserving seats when you book your travel.”

American Airlines “Seats for your family: Keep in mind, if you can't find seats together now, we'll do our

best to find them for you before the day of departure. If seats are limited, we'll assign

seats so children are next to at least 1 adult in your party.”

Delta Airlines “Delta strives to seat family members together upon request. If you are unable to obtain

seat assignments together for your family using delta.com or the Fly Delta mobile app,

please contact Reservations to review available seating options.”

Frontier Airlines “When one or more of the passengers on a reservation are 13 years of age or younger,

Frontier will guarantee adjacent seats for the child or children and an accompanying

adult (over age 13) at no additional cost for all fare types subject to limited conditions

specified below.”

Hawaiian Airlines “We'll do our best to seat children under age 14 with an accompanying family member.

Select your own seats as far in advance as possible by logging in to My Trips. If no

suitable seats are available online, let our agents know when you get to the airport, and

they'll do their best to reseat you.”

JetBlue Airways “We will always do our best to seat children with an adult family member. For the best

seating options, we recommend booking early and selecting seat assignments at the

time of booking or with a reservation crewmember (third party service fees may apply). If

seats together are not available, please let our airport gate crewmembers know when

you arrive at the airport. They will do their best to find a seating solution. We cannot

guarantee that seats together will always be available.”

Southwest Airlines “Family boarding after A group for adults with children under 6. If you need and request

assistance, Southwest will endeavor to seat a child next to one accompanying passenger

(14 and older) to the maximum extent practicable and at no additional cost.”

Spirit Airlines “If Guests with children aged 13 and under do not opt to pre-select seats at the time of

booking, our gate agents and Flight Attendants will work to provide adjacent seats when

possible.”

United Airlines “If you’re flying with children under 12, we have new tools that make it easier for them to

sit next to a family member for free. This includes families who have Basic Economy

tickets. If seats next to each other aren’t available on your flight because of last minute

bookings or unscheduled aircraft changes, you can switch to another flight with

availability in the same cabin for free and won’t be charged for the difference in fare.”

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 8

selection is included in the fare, subject to the availability of seats. American and JetBlue offer

advance seat reservations for a fee to customers who purchase Basic Economy tickets. Alaska,

Delta, Hawaiian, and United do not offer any advance seat reservations on Basic Economy fares.

Allegiant, Frontier, and Spirit do not include advance seat reservations in their basic fares.

Passengers can purchase advance seat reservations for a fee, either as a standalone add-on or in

a bundle with other services such as baggage or onboard beverages. Southwest does not assign

seats in advance of boarding. Passengers board in priority groups based on ticket type and time

of check-in. Travelers can purchase access to the first priority group for a fee, subject to

availability.

Families who do not arrange seating assignments prior to travel, either by paying a seating fee

or exercising an alternative to the fee that some airlines may offer, run the risk of arriving at the

gate and finding that a child may be seated way from an accompanying adult. Families must

then rely on gate agents, flight attendants, or perhaps other passengers to accommodate their

needs for specific seating arrangements.

4.2 Airline passengers who travel as families

The proposed rule would require that airlines distinguish passengers traveling with children

from other passengers. Regarding seat assignments, we assume that passengers traveling with

children currently are treated as all other passengers though as noted, airlines make some effort

to address family seating issues when they arise. Table 4-2 provides Bureau of Transportation

Statistics (BTS) data on the number of airline passengers by airline in 2022. We use 2022 as the

baseline number of passengers potentially affected by the rule.

Airlines that currently do not distinguish passengers traveling as a family from other passengers

will need to develop those capabilities. For this analysis, we consider a family to consist of

children under the age of 14 traveling by plane with persons who are at least 14 years old. We

assume that the proposed rule will require that airlines match one adult with one child (“adult-

child pair”). If a trip involves three children and two adults from the same household, the

number of adult-child pairs would be two, with one adult being seated with two children and

the other adult being seating with one child. If one child travels with two adults, the number of

adult-child pairs would be one. The proposed rule would not require that the entire family are

seated together, just that each child is matched with an accompanying adult. We term all other

passengers—i.e., those not traveling as an adult-child pair—"solo passengers.” The important

distinction between adult-child pairs and solo passengers is that solo passengers remain eligible

to be charged a separate seating fee under the proposed rule.

Disaggregating the data on overall airline passengers to estimate the number of adult-child

pairs versus solo passengers involved several steps. Estimates are derived from publicly available

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 9

Table 4-2: Number of airline passengers in 2022

Carrier

Domestic

International

Total

Alaska Airlines

29,878,122

1,913,336

31,791,458

Allegiant

16,827,212

41,892

16,869,104

American Airlines

120,554,448

30,306,916

150,861,364

Delta

122,484,640

19,420,112

141,904,752

Frontier

23,415,072

2,048,582

25,463,654

Hawaiian

9,637,017

361,388

9,998,405

JetBlue

30,508,098

9,115,926

39,624,024

Southwest

153,161,568

3,846,000

157,007,568

Spirit

33,850,212

4,557,293

38,407,505

United

87,444,528

25,209,342

112,653,870

Other Domestic Carriers

125,187,280

6,192,576

131,379,856

Total

752,948,197

103,013,363

855,961,560

Source: Air Carrier Statistics (Form 41 Traffic) T-100 data.

data, including the BTS American Travel Survey (ATS) and Air Carrier Statistics (Form 41 Traffic)

T-100 data, and the Census Bureau’s population statistics. Additional estimates are based on the

U.S. Family Travel Survey conducted by the Jonathan M. Tisch Center of Hospitality at New York

University.

5

The ATS collected trip-level information on the mode of transport and the ages of traveling

household members. However, BTS conducted the ATS in 1995 and it is necessary to adjust for

demographic composition changes since 1995. The adjustment factors are derived from Air

Carrier Statistics (Form 41 Traffic) T-100 data and the Census Bureau’s population statistics.

Updating the ATS with more recent air passenger and Census data is discussed in the expert

report (“Estimates Based on the American Travel Survey,” pp. 11-13), which provides the result

that roughly 9.7 percent of air passengers consist of adult-child pairs. Using the passenger totals

reported in Table 4-2, roughly 83 million travelers (73 million on domestic and 10 million on

international flights) on U.S. carriers are part of an adult-child pair. The remaining 773 million

passengers are solo passengers and remain eligible to be charged seating fees under the

proposed rule.

4.3 Seating fee revenue and charges

BTS collects data on airline revenue from fees for baggage and reservation changes and

cancellation, but not from seating fees. Another source of information on airline revenue is the

5

See Appendix 2 for links to the datasets.

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 10

airlines’ 10-k annual reports filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. In general,

airlines include revenues from seating fees in the passenger revenues reported in the 10-k

statements. Alaska Airlines, Allegiant Air, Delta Airlines, Southwest Airlines, and United Airlines

report revenues from ancillary fees, but not seat reservation fees, separately from other

passenger revenues in their 10-k reports. These ancillary fees include charges for checked

baggage, changed or canceled reservations, in-flight purchases, and seat reservations. American

Airlines, Hawaiian Airlines, and JetBlue Airlines do not break out revenues from ancillary fees or

from seat reservation fees in their 10-k reports.

Two airlines, Spirit and Frontier, report revenues from seat reservation fees as separate line

items. Based on their information, the estimated seating fee revenue per passenger was

approximately $9.43 in 2022. This estimate is the arithmetic mean between Frontier’s reported

seating fee revenue per passenger and Spirit’s estimated revenue per passenger. The average

includes passengers who did not make an advance seat reservation and paid $0 as well as other

passengers who paid a value greater than $9.43 for their seats. As shown in Table 4-2, U.S.

airlines transported 856 million air travelers in 2022. This means that the industrywide revenue

collected from seating fees could amount to about $8.1 billion annually ($9.43 * 856 million).

This estimate assumes that seating fee revenues for Spirit and Frontier are representative of the

industry as a whole. However, Spirit and Frontier are low-cost carriers which tend to rely more

on seat selection fee revenue than legacy carriers. Thus, we are likely overestimating industry-

wide seating fee revenue by using this approach.

The average cost of a seat reservation per person, for those who make a reservation, is not

reported in publicly available data but can be inferred by applying other market information. A

survey conducted by Skyscanner in 2022 found that 37 percent of U.S. respondents would be

willing to pay a fee for advance seat selection.

6

If 37 percent of travelers purchase advance seat

assignments and the average revenue per passenger is $9.43, then the average fee per

reservation must be $25.49 (0.37 * $25.49 = $9.43). The represents the seating fee for each

direction of travel so that passengers with a roundtrip ticket pay two times that amount, or

$50.98. Note that the Skyscanner estimate is based on a survey question about international

travel, and we are assuming that that passengers are equally likely to purchase a seat reservation

on domestic and international flights. We request comment on this estimate and seek data to

better estimate the number or percentage of passengers who purchase seat reservations, and

whether that percentage is different for passengers who travel as a family.

6

See https://www.partners.skyscanner.net/hubfs/Reports/Horizons-Nov2022.pdf .

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 11

5 Economic impacts of the proposed rule

5.1 Framework for analysis

To evaluate the economic impacts of the proposed rule, we apply a simple model of air travel

demand that groups air consumers into two categories: adult-child pairs and solo passengers.

To simplify the analysis, we assume that the overall number of tickets sold does not change as a

result of the proposed rule. That is, if the proposed rule induces any change in the number of

adult-child pairs that travels, that change is exactly offset by a change in the number of solo

passengers. This simplifies the analysis by constraining the resulting effects to fall in the

category of transfers. Transfers are benefits and costs that have exactly offsetting effects and do

not contribute to a net benefits calculation.

The proposed rule requires that airlines seat a child with an adult and prohibits them from

charging a separate seating fee. Initially, we assume that the airlines have technical capabilities

that allow them to distinguish between the two groups of passengers. Developing the

capability is an upfront cost to airlines who do not have family seating policies currently, which

we estimate separately in Section 5.4.

Once airlines can distinguish between adult-child pairs and solo passengers, the proposed rule

affects the two groups of passengers differently. For the families who pay seating fees in the

baseline, the effect of the elimination of those seating fees is to reduce the total price of air

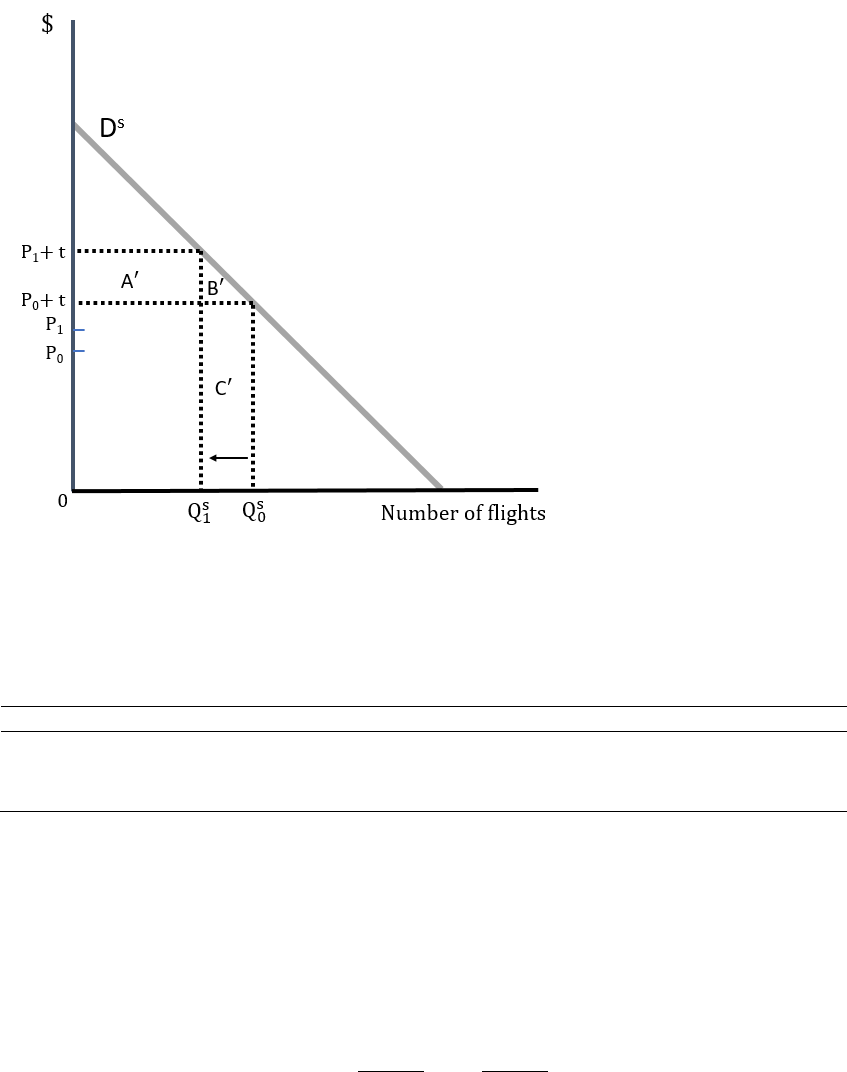

travel. In Figure 5-1, airlines charge families a fare of P

0

plus a seating fee of t in the baseline,

which results in families purchasing Q

airline tickets. If airfares remain unchanged, the

elimination of t would cause the quantity of airline tickets demanded by families to increase to

Q

. However, the increase in tickets purchased by families will put upward pressure on base

airfares, which increase to P

1

. As detailed in the expert report, the expected increase in airfare is

calculated by applying demand elasticities to estimates of baseline airfares, seating fees, and

numbers of adult-child pairs and solo passengers. Under the proposed rule, airlines will not be

allowed to charge families seating fees, so the total price of air travel to families becomes P

1

,

and families purchase Q

airline tickets. The quantity of tickets purchased is greater than in the

baseline scenario, but less than if airfares did not adjust.

The decrease in price increases consumer surplus for families by the area A+B in Figure 5-1.

Part of this increase would come from the reduction in the price paid by families who would

have flown even if they had to pay for advance seat reservations (area A). This part is a revenue

loss from the perspective to airlines, which is offset to an extent by the increase in number of

families who travel at the lower price, or area C in Figure 5-1. The remaining increase in

consumer surplus comes from families who would not travel if they had to pay for advance seat

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 12

Figure 5-1: Demand for air travel (adult-child pairs)

reservations but travel by air under the proposed rule because they do not have to pay for seat

reservations (area B).

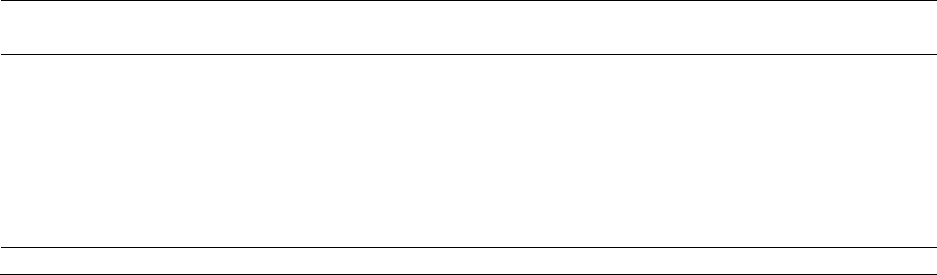

The proposed rule will also affect airfares for and the quantity of tickets sold to solo passengers

as shown in Figure 5-2. We assume that the proposed rule does not affect the amount of the

seating fee, and that the total price for solo passengers increases from P

0

+ t to P

1

+ t due to the

proposed rule. The increase in airfare reduces the quantity of tickets purchased by solo

passengers from Q

to Q

and solo passengers experience a decrease in consumer surplus in the

amount of the area A′ + B′. Part of the decrease in consumer surplus comes from passengers

who purchase tickets even after the price increase (area A′). This part of the reduction in

consumer surplus is a gain in revenue to the airlines, which is offset by a loss due to a lower

number of solo passengers (area C′). The remaining decrease in consumer surplus comes from

passengers who choose to no longer travel because of the price increase (area B’).

Figure 5-3 illustrates how we record these impacts in the social accounting ledger, and provides

the basic guidance for quantifying these effects.

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 13

Figure 5-2: Demand for air travel (solo passengers)

Figure 5-3: Social accounting ledger for recording economic impacts

Party

Gains

Losses

Change due to proposed rule

Families traveling by air

A + B

A + B

Solo passengers

A′ + B′

- (A′ + B′)

Airlines

A′ + C

A + C′

(A′ + C) – (A + C′)

As noted, this analysis assumes that the equilibrium number of tickets, Q

, sold does not change

because of the proposed rule, or that

Q

= Q

+ Q

= Q

+ Q

.

This means that, in the absence of other market effects,

P

= P

+ t =

P

+

(P

+ t) .

More specifically, due to the restriction that the overall equilibrium number of tickets sold does

not change under the proposed rule, we expect that the average market airfare, P

, will remain

at its baseline level in this simplified model. While the proposed rule may create an initial

disturbance away from equilibrium price, the tendency will be for the market to return to the

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 14

previous equilibrium. Ultimately, overall airline revenue will remain unchanged because the

equilibrium number of passengers and average ticket prices, Q* and P

*

remain unchanged.

Relative prices paid by families and solo passengers will adjust such that consumer surplus gains

are exactly offset by consumer surplus losses. For this reason, we view many of the economic

effects estimated below as transitory.

In reality, airlines are not constrained to operating within the simple model because they have

other options besides adjusting airfares. These other options include adjusting the seating fees

or any other existing or new fee.

5.2 Price effects

Price effects can be estimated applying information regarding the nature of the demand curve

for air travel. Several studies provide estimates of the price elasticities of demand in the U.S.

airline industry. The RIA for Accessible Lavatories on Single-Aisle Aircraft applied the values of -

1.2 for domestic travel and -0.6 for international travel in the primary analysis and conducted

sensitivity analyses for lower and higher elasticities. This analysis applies the same values in the

primary analysis, but other values are examined as part of a sensitivity analysis. In particular, the

sensitivity analysis examines elasticities ranging from -0.8 to -2.0 for domestic travelers and from

-0.6 to -2.0 for international travelers, as detailed in the appendix.

Because the overall number of available tickets available in the market is assumed to be

unaffected by a proposed rule, the increase in the number of airline tickets purchased by adult-

child pairs is equal in absolute value to the decrease in the in the number of airline tickets

purchased by solo passengers. Average overall ticket price will increase to equilibrate supply

and demand under the proposed rule, but adult-child pairs experience a lower effective price

than in the baseline because they will no longer pay for advance seat reservations. Ticket prices

will increase for solo passengers.

Price increases due to the proposed rule are estimated by applying the demand elasticities to

baseline passenger levels, ticket prices, and estimated seating fees. Average ticket prices in the

baseline are estimated to be $248.64 for domestic flights and $560.68 for international flights.

7

From Section 4.2, the baseline number of adult-child pairs is 72.8 million and the number of solo

passengers is 680.1 million on domestic flights. The estimated increase in price also depends on

the percentage of travelers who make advance seat reservations.

7

Average domestic airfare is based on data for the first quarter of 2023 from the Bureau of Transportation

Statistics, Airline Origin & Destination Survey. Average international airfare is estimated using FAA

forecasts. Details regarding these calculations are provided in the expert report (Appendix 3, p. 39).

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 15

Table 5-1 and Table 5-2 summarize the calculations under a scenario in which 37 percent of all

passengers, both families and solo passengers, purchase seat reservations. The average airfare

increase will range from $0.86 per direction for domestic travelers and $1.93 for international

travelers. Given ticket prices of $248.64 for domestic travel and $560.68 for international travel,

these price changes are equivalent to a price increase of about 0.3% of baseline airfare.

Table 5-1: Summary of price effects for domestic flights

Adult-child pairs

Solo passengers

Purchasing

Seats

Not Purchasing

Seats

Purchasing

Seats

Not Purchasing

Seats

Baseline number of passengers (millions)

26.9

45.8

251.7

428.5

Baseline airfare

$274.13

$248.64

$274.13

$248.64

Price under proposed rule

$249.50

$249.50

$274.99

$249.50

Airfare change (baseline airfare – price

under proposed rule)

-$24.63 $0.86 $0.86 $0.86

Percent airfare change

-9.0%

0.3%

0.3%

0.3%

Price elasticity of demand

-1.12

-1.12

-1.12

-1.12

Percent change in number of passengers

10.5%

-0.4%

-0.4%

-0.4%

Change in number of passengers (millions)

2.8

-0.2

-1.0

-1.7

Number of passengers under proposed rule

29.8

45.7

250.8

426.8

Table 5-2: Summary of price effects for international flights

Adult-child pairs

Solo passengers

Purchasing

Seats

Not Purchasing

Seats

Purchasing

Seats

Not Purchasing

Seats

Baseline number of passengers (millions)

3.6

6.2

34.5

58.7

Baseline airfare

$618.16

$560.68

$618.16

$560.68

Price under proposed rule

$562.61

$562.61

$620.09

$562.61

Airfare change (baseline airfare – price

under proposed rule)

$55.55

-$1.93

-$1.93

-$1.93

Percent airfare change

-9.0%

0.3%

0.3%

0.3%

Price elasticity of demand

-0.6

-0.6

-0.6

-0.6

Percent change in number of passengers

10.5%

-0.4%

-0.4%

-0.4%

Change in number of passengers (millions)

0.2

-0.0

-0.1

-0.2

Number of passengers under proposed rule

4.0

6.2

34.4

58.5

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 16

Despite the increase in base airfare, passengers who travel as a family and currently purchase

advance seat reservations would experience a decrease in the price of air travel because they

would no longer have to pay for seat reservations. Given the average seat reservation fee of

$25.49 for domestic travelers and $57.48 for international travelers, the full ticket price including

seat reservations for families will decrease about $24.63 for domestic travelers and about $55.55

for international travelers. This is equivalent to an average price reduction of roughly 9 percent.

The analysis assumes that total passenger traffic does not change, at least in the short run.

However, due to differential price changes, the mix of passengers between adult-child pairs and

solo passengers changes in the analysis. The number of passengers who travel with a child

under the age of 14 increases roughly 10 percent while the number of solo passengers

decreases about 0.4 percent.

5.3 Benefits

Benefits are due to the reduction in disutility experienced by consumers from the separation of

families on aircraft. Families traveling by air who do not purchase advance seat reservations or

make other arrangements with the airlines to ensure that they are seated together would

experience improved mental health because children and parents will no longer suffer from

anxiety related to their separation on the plane. Complaints submitted by travelers to the

Department reveal general concerns about young children being separated from their parents

and specific issues relating to children’s and adults’ anxiety.

8

Families also will save time if they no longer need to contact the airline or a gate agent to obtain

seats together. Currently, airlines that do not guarantee that they can seat families together

often recommend contacting the airline as soon as possible after booking to make seat

reservations or work with a gate agent at the airport. Airline call center wait times vary and

depending on whether there are service disruptions, call wait times can be significant. Gate

agents have many responsibilities and may have limited ability to make seating adjustments.

For families who purchase seating assignments in the baseline, these types of benefits would be

limited. We assume that the airlines largely honor these arrangements. However, there could be

some benefits for these families in cases of rebooking or situations where an airline might need

to reassign seats.

Passengers who do not travel with children could also experience benefits that we have not

quantified. In the status quo, some travelers might end up seated next to children who are

separated from their parents. If the separated children suffer anxiety or need assistance, the

passengers seated next to them likely are affected.

8

See https://www.regulations.gov/document/DOT-OST-2022-0109-0023

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 17

The proposed rule also requires that the airlines provide information on family seating to

consumers. Given that the airlines already provide family seating information as shown in Table

4-1 and that the proposed rule requires that the airlines provide family seating regardless of

whether the consumer is aware of those polices, the additional benefits from the information

requirements are probably limited. More specifically, this analysis assumes that the actual

requirement to provide family seating would largely override the need for families to collect

information about family seating, and that the information requirements would not provide an

independent benefit.

5.4 Costs

The proposed rule will require that airlines distinguish families from other passengers in

assessing seating fees, which will involve some upfront resource costs. Four airlines – Alaska,

American, Frontier, and JetBlue – implemented policies that guarantee family seating in 2023.

We do not have information of the costs of implementing these systems and assume that the

airlines with guaranteed family seating will not incur any additional costs. In addition, Southwest

Airlines does not allocate seats in advance, but would need to adjust boarding procedures to

assure for family seating for parties traveling with children between 7 and 13 years old. We do

not have an estimate of the costs of changes to open boarding procedures and those costs are

not included in the analysis.

A system to ensure family seating would identify bookings with children under 14 and

accompanying adults and allow those individuals to reserve seats together in advance with no

separate charge. Airlines would need to personalize the pricing of seats based on the ages of

the individuals in a reservation. Once this capability is implemented, there should not be other

ongoing costs.

The airline industry is transitioning to personalized pricing to tailor ticket prices or ancillary fees

to the customer’s identity or purchase history.

9

The International Air Transport Association

(IATA) has developed the “New Distribution Capability” (NDC), which is a data transmission

standard that facilitates communication between airlines and third-party sellers, such as travel

agents.

10

Importantly, the NDC enables dynamic and personalized fare offers including

individualized pricing of ancillary services. According to IATA, American, Delta, Southwest, Spirit,

and United have NDC capabilities.

11

9

See, for example, Fiig, Le Guen, and Gauchet (2018), “Dynamic Pricing of Airline Offers”, Journal of

Revenue Pricing Management, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41272-018-0147-z

10

See https://www.iata.org/en/programs/airline-distribution/retailing/ndc/ .

11

See, for example, https://www.sabre.com/insights/new-distribution-capability for more detail.

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 18

The NDC is a communication standard for third-party bookings, not a method for pricing tickets

sold directly by airlines. Airlines will need to implement seat reservation policies for qualifying

families in their own internal reservation systems as part of a personalized pricing strategy. Once

personalized pricing is implemented in internal systems, the NDC should allow airlines to

implement the same pricing for third-party bookings. The system will allow airlines to maintain a

different fee structure for families versus other travelers.

A 2019 report by the management consulting firm McKinsey & Company outlines a possible

transition from the traditional flight distribution system to personalized pricing with NDC-based

distribution.

12

The report estimates that the transition would cost the global airline industry

(including airlines outside the United States) about $3 billion. A 2021 report by IATA calculates

that this is equivalent to about 10 percent of current airline information technology spending.

NDC exceeds the capabilities needed for airlines to offer personalized pricing as it pertains to

family seating. However, we use the costs of implementing NDC to approximate the costs of

implementing the proposed family seating rule, recognizing that this may lead to an

overestimate of implementation costs.

Delta is the only airline that includes IT-related expenses (specifically, the amortization of

capitalized software) separately from other expenses in its 10-k annual reports. From Delta’s

2019 and 2022 annual reports, average amortized expenses of capitalized software over the

years 2017-2022 is $286 million as shown in Table 5-3. This amounts to $2.02 ($2022) per

passenger using Delta’s passenger numbers.

Industry-wide implementation costs depend on the number of airlines that need to make IT

upgrades that allow for family seating. As noted, four airlines (Alaska, American, Frontier, and

JetBlue) have already guarantee family seating and are assumed to incur no further costs. Also,

Southwest does not assign seating and is also not assigned costs.

Among the remaining airlines, those that already have NDC capabilities (Hawaiian, Spirit, and

United) will have lower costs that those that have yet to adopt NDC capabilities (Allegiant and

Delta). One estimate of implementation assumes that all airlines that have adopted the NDC

standard have also already implemented personalized pricing. A second estimate assumes that

airlines that have adopted the NDC standard have not yet adopted personalized pricing. These

estimates represent upfront one-time expenses, and we assume that that once implemented,

any ongoing maintenance will be conducted as part of overall IT maintenance and there will be

no recurring maintenance costs.

12

See https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/airline-

retailing-the-value-at-stake .

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 19

Table 5-3: Delta Airlines’ amortized expenses of capitalized software, 2017-2022

Year

Current $

(millions)

2022 $

(millions)

Total passengers

(millions)

2022 $ per

passenger

2017

187

225

145.4

1.55

2018

205

242

151.9

1.59

2019

239

276

162.5

1.70

2020

304

346

55.2

6.27

2021

301

320

103.1

3.10

2022

307

307

141.9

2.16

Average

286

2.02

Sources: Delta Airlines’ 2019 and 2022 10-k annual report, Air Carrier Statistics (Form 41 Traffic) T-100 data.

Note: Expenses reported in current dollars are not adjusted for inflation. The third column adjusts all expenses for

inflation by converting them to 2022 dollars. The average cost per passenger uses the 2022 passenger numbers.

Allegiant and Delta still need to implement NDC and personalized pricing capabilities. Summing

the product of the IT cost of $2.02 per passenger and the number of passengers in 2022 (see

Table 4-2) for each airline yields an estimated total IT cost of $320 million. Applying the

McKinsey estimate that the costs of implementing the NDC and personalized pricing are 10

percent of IT costs results in an estimated implementation cost of $32 million.

A second estimate assumes that the airlines that have already implemented the NDC still need

to implement personalized pricing, and that the cost of implementing personalized pricing is 50

percent of the full implementation costs. The estimated implementation costs for Hawaiian,

Spirit, and United in this scenario are $16.2 million. Adding this to the implementation costs of

the non-NDC-capable airlines results in an industry-wide implementation cost of $48.2 million.

The implementation costs are upfront costs that are incurred only once. We present two

scenarios in which these one-time costs are annualized over 5- and 10-year periods using a 2

percent discount rate (Table 5-4). Annualized implementation costs range from $6.8 million to

$10.2 million over 5 years, and $3.6 million to $5.4 million over 10 years.

While it is reasonable to expect that carriers’ implementation costs scale with carrier size, we

could alternatively assume that all carriers face the same fixed implementation cost. To estimate

industry-wide costs in this case, we start by taking the 5-year average annual IT-related costs for

Delta ($283 million) and assume that all carriers spend an equivalent amount. As before, we

assume that non-NDC-capable airlines (Delta and Allegiant) will need to spend 10 percent of

their annual IT-related expenditure to develop personalized pricing, while NDC-capable airlines

(Hawaiian, Spirit, and United) will need to spend 5 percent.

The estimated implementation costs of the proposed rule, assuming equivalent costs across all

airlines, are presented in Table 5-5. Again, we present annualized costs over 5- and 10-year

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 20

Table 5-4: Implementation costs per airline, scaled by carrier size

Total passengers

(2022, millions)

Implementation costs

(2022 $, millions)

Annualized

Airline

Total

5 years

10 years

Non-NDC-capable airlines

158.8

32.0

6.8

3.6

Allegiant

16.9

3.4

0.7

0.4

Delta

141.9

28.6

6.1

3.2

NDC-capable airlines

161.1

16.2

3.4

1.8

Hawaiian

10.0

1.0

0.2

0.1

Spirit

38.4

3.9

0.8

0.4

United

112.7

11.4

2.4

1.3

Implementation cost

Estimate 1 (Only non-NDC airlines incur costs)

158.8

32.0

6.8

3.6

Estimate 2 (NDC airlines incur 50% cost)

319.9

48.2

10.2

5.4

Sources: Delta Airlines’ 2019 and 2022 10-k annual report, Air Carrier Statistics (Form 41 Traffic) T-100 data.

Note: Total cost of implementation is estimated to be 10% of total IT cost ($2.02 per passenger) for airlines that do not

yet have NDC capabilities (Estimate 1), and 5% of total IT costs for those that do (Estimate 2). Annualized costs assume a

2% annual discount rate.

Table 5-5: Implementation costs per airline, fixed

Implementation costs

(2022 $, millions)

Annualized

Airline

Total

5 years

10 years

Non-NDC-capable airlines

56.6

12.0

6.3

NDC-capable airlines

42.4

9.0

4.7

Implementation cost

Estimate 1 (Only non-NDC airlines incur costs)

56.6

12.0

6.3

Estimate 2 (NDC airlines incur 50% cost)

99.0

21.0

11.0

Sources: Delta Airlines’ 2019 and 2022 10-k annual report, Air Carrier Statistics (Form 41 Traffic) T-100 data.

Note: Total cost of implementation is estimated to be 10% of total IT cost ($283 million) for airlines that do not yet have

NDC capabilities (Estimate 1), and 5% of total IT costs for those that do (Estimate 2). Annualized costs assume a 2%

annual discount rate.

horizons. Annualized costs range from $12.0 million to $21.0 million over 5 years, and from $6.3

million to $11.0 million over 10 years. While these figures are approximately double the size of

the scenario in which costs scale with carrier size, we believe that it likely overestimates the

implementation costs of the proposed rule.

The estimates of costs applied a discount rate of 2 percent to annualize costs. Cost estimates

using 3 and 7 percent discount rates are presented in Appendix A.

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 21

The proposed rule also requires that the airlines provide information on family seating to

consumers. Given that the airlines already provide family seating information as shown in Table

4-1, we assume that only minor adjustments would be needed. Thus, the cost of providing the

additional information should be small.

5.5 Transfers

5.5.1 Consumer surplus gains for families who currently pay for seat reservations

Families who pay for advance seat reservations will experience a net price reduction under the

proposed rule. Even though prices for tickets without seat reservations would increase, the

savings that these travelers experience from not needing to pay for seat reservations exceeds

the price increase, resulting in a net price reduction. Consequently, families would experience an

increase in their consumer surplus as described by Figure 5-1. Table 5-6 provides the results of

the calculations, using the information provided in Table 5-1 and Table 5-2.

5.5.2 Reduction in consumer surplus due to airfare increases

Consumer surplus would decrease for all solo passengers, whether they pay for a seat

reservation or not, because the base ticket price they pay will increase. Families who do not pay

for seat reservations in the baseline will also experience an increase in base ticket prices, and

thus, a decrease in consumer surplus. The losses in consumer surplus for families who do not

purchase seat reservations is lower than the gains in consumer surplus reported in Table 5-6.

This reflects that the increase in airfare is much smaller in size than the size of the seating fee

that is eliminated under the proposed rule. Table 5-7 summarizes these calculations.

Table 5-6: Consumer surplus gains to families who pay seat reservation fees (2022$, millions)

Domestic

International

Total

Consumer surplus gain

$698

$212

$910

Table 5-7: Consumer surplus loss due to airfare increases (2022$, millions)

Passenger group

Domestic

International

Total

Solo passengers

Purchase seat reservation in the

baseline

$215 $66 $281

Don’t purchase seat reservations

in the baseline

$366 $113 $479

Adult-child pairs not purchasing seat

reservations in the baseline

$39 $12 $51

Total consumer surplus loss

$620

$191

$811

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 22

Table 5-8: Decrease in airline revenue due to proposed rule (2022$, millions)

Domestic

International

Total

Decrease in airline revenue

$65

$21

$85

5.5.3 Revenue effects

Airlines would experience revenue impacts if they cannot charge seating fees to families. As

noted, we assume that the total number of tickets sold is unaffected and that the airlines are

indifferent to any change in the mix of passengers, which simplifies the calculation As with the

consumer surplus calculations, the necessary information to perform these calculations is

provided Table 5-1, Table 5-2, and Table 5-3. Table 5-8 summarizes the results.

5.6 Comparison of benefits and costs

The results of our analysis are summarized in Table 5-9. These results reflect an assumption that

37 percent of passengers purchase seat reservations, and DOT requests comment on that

assumption. Consumer surplus gains to families who no longer pay seating fees ($910 million)

outweigh losses in consumer surplus for other passengers ($811 million). Other passengers

include solo passengers and families who do not purchase seat assignments in the baseline.

Ultimately, net benefits depend on the size of the unquantified benefits relative to the

implementation costs. We did not quantify societal benefits due to the lack of reliable data on

the number of families who experience stress or anxiety due to airlines’ family seating policies.

We also have no information on the value that families attach to avoiding problems with family

seating arrangements.

Finally, we expect that the estimated effects would be transitory in nature. Under the

assumption that the total number of passengers (families plus solo passengers) remains

unchanged, the tendency will be for the market to return to its prior equilibrium. In addition,

airlines have many options for responding to the proposed rule including adjusting airfares,

seating fees, and any other existing or new fee.

5.7 Additional impacts

The result of the quantitative analysis is that airlines experience a reduction in revenue due to

this proposed rule. The reduction in revenue comes from the loss in seating fee revenue

collected from families and the reduction in travel on the part of solo passengers and families

that do not pay seating fees in the baseline. It is possible that airlines could make additional

price and fee adjustments to recover revenue losses subject to other competitive constraints. In

addition, airlines may try to pass on implementation costs to consumers. However, we have no

information to judge the extent of these secondary impacts.

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 23

Table 5-9: Summary of economic impacts, first year (2022$, millions)

Benefits (+)

Reduced disutility to passengers

from separation of families

traveling by air

Unquantified

Costs (-)

Implementation costs

$5-21

Net societal benefits (costs)

Not calculable

Transfers (0)

Increase in consumer surplus from

elimination of seating fees for

families

$910

Airline revenue loss

$85

Decrease in consumer surplus for

solo air passengers

$760

Decrease in consumer surplus for

families who do not pay for seat

reservations

$51

The economic analysis is a short-run analysis in that it assumes that the equilibrium overall

number of passengers is unchanged by the proposed rule. Equivalently, we are assuming that

the airlines are capacity-constrained and that it is not technically feasible or economical practical

for them to respond to the increase in air travel demand on the part of families by increasing

load factor, a measure of capacity utilization, or by filling empty seats, for example. This mirrors

the RIA for Accessible Lavatories on Single-Aisle Aircraft. In addition, for a given number of total

passengers, we assume the cost to airlines of providing air travel to a mix of passengers that

includes more families is the same as a mix that includes fewer. Airlines would be indifferent to

the mix of passengers and the increase in air ticket purchases by families who would purchase

seat assignments absent the rule is exactly offset by a decrease in ticket purchases by solo

passengers and families who do not purchase seat assignments. Under these assumptions,

average airfares paid by consumers will be affected only to the extent that implementation costs

are passed on to consumers. Cost impacts are estimated to be small relative to consumer

surplus impacts, which suggests that the predominant effect of the proposed rule will be

monetary transfers among consumer types. The lower airfares paid by the increased number of

families who travel will be offset by the higher airfares paid by decreased number of other

passengers such that average airfare should remain relatively stable.

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 24

An alternative approach to assuming that the total number of passengers is unchanged by the

proposed rule might be to allow for a supply response on the part of airlines, perhaps by

modelling the airline ticket supply curve as upward-sloping. In this case, the increase in demand

for airline tickets by families would increase both equilibrium average airfare and the number of

tickets sold. Estimating consumer surplus effects would require information on the supply curve

for air travel or other assumptions about how airlines make capacity adjustments to

accommodate an increase in demand. However, we do not have an empirical basis for

estimating these adjustments. In fact, we expect that if it is possible for airlines to profitably

increase the number of tickets sold, they would do so in the baseline and in the absence of this

rule.

5.8 Sensitivity analysis

As described in the expert report, the economic analysis included a sensitivity analysis to

examine how the results change using alternative demand elasticity values. The sensitivity

analysis applied elasticities ranging from -0.8 to -2.0 for domestic travelers and from -0.6 to -2.0

for international travelers. In general, the results are robust with respect to the demand

elasticity applied. Higher elasticity values tend to magnify the estimated impacts somewhat, but

do not change the general conclusions. The result that demand elasticity only modestly affects

estimated impacts could be a result of assuming adult-child pairs and solo passengers have the

same elasticity of demand. If the two consumer groups have different elasticities, that would

likely influence the results but also complicate the analysis. We do not, however, have an

empirical basis for assigning different elasticity values.

6 Regulatory alternatives

6.1 No action

The no action regulatory alternative would rely on current industry voluntary efforts. On July 8,

2022, the Department issued a notice that urged airlines “to do everything in their power to

ensure that children who are age 13 or younger are seated next to an accompanying adult with

no additional charge.” The Department launched the Family Seating Dashboard on March 6,

2023. The Dashboard currently shows four airlines (Alaska, American, Frontier, and JetBlue) as

having committed to guaranteeing family seating without a separate fee. As outlined above, all

other large domestic carriers have policies to do their best to seat families together, but they

stop short of guaranteeing it.

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 25

Given that six of the ten large airlines have chosen not to guarantee family seating despite the

Department’s efforts to encourage the practice and calls from consumer advocacy groups,

13

it is

unlikely that they would all issue such guarantees in the absence of additional pressure from the

market or the government. The four airlines with guaranteed family seating policies could

change their policies at any time. The experience with checked baggage fees shows that airlines

adopted baggage fees at a time when they were under financial pressure and when competition

from low-cost carriers pushed them to unbundle their services and advertise lower ticket prices.

It is possible that airlines would re-consider family seating policies in the future in times of

financial stress or competitive pressure.

However, research shows that public reporting of quality metrics can have a positive effect on

airline service quality. One study shows that airlines have lengthened their scheduled flight times

and reduced flight delays substantially in the decade leading up to 2019.

14

This development

coincided with increased public attention to flight delays, and it is possible that airlines may

have responded to pressure from the flying public to improve their on-time performance. Public

pressure to address family seating problems may elicit a similarly positive response.

6.2 Guaranteed family seating without fee restrictions

A second alternative would be to adopt the requirement for airlines to guarantee family seating

but not to impose a requirement that the airlines eliminate seating fees for families. This

alternative would result in roughly the same benefits and costs as the proposed rule. The

reassurance that airlines would meet family seating needs regardless of whether a family

purchases a separate seat reservation would reduce stress and anxiety for families. Other

passengers would no longer be burdened with being seated next to a child who is separated

from an accompanying adult. Airlines would still incur implementation costs. Families who

currently pay seating fees because they believe that the only way to assure being seated

together is to pay a seating fee could simply stop paying the fees and still be guaranteed seats

together. In general, we expect that this alternative would yield the same result as the proposed

rule.

7 Summary

This RIA evaluates the benefits and costs of a Department of Transportation proposed rule to

amend 14 CFR Part 259, Enhanced Protections for Airline Passengers, to require U.S. and foreign

13

See Airlines: Kids should sit with their parents! (consumerreports.org), accessed on 10/27/2023.

14

Forbes, Silke, Mara Lederman, and Zhe Yuan, “Do Airlines Pad Their Schedules?”, Review of Industrial

Organization Volume 54, Issue 1, February 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48702939 .

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 26

air carriers to seat children aged 13 and under next to at least one accompanying adult without

charging a separate fee.

The benefits of the proposed rule are that families can be assured that they will be seated

together during air travel without paying a separate fee. For families that do not currently pay

seating fees, some will experience a reduction in stress and anxiety associated with air travel or a

decrease in the amount of time needed to make seating arrangements prior to air travel.

Families who currently pay seating fees will see a reduction in the total price they must pay for

airline tickets. Passengers who do not travel as a family will experience increased costs due an

increase in airfare as will families who do not currently purchase seating assignments. Airlines

will incur upfront costs to adjust their ticketing systems to allow them to distinguish passengers

traveling as a family from other passengers, and opportunity costs associated with a reduction in

revenue they receive from seating fees.

An alternative that would yield roughly the same net societal benefits would be to adopt the

requirement for airlines to guarantee family seating but to not impose a requirement that the

airlines eliminate seating fees for families. The Department did not propose this option,

however, because as described in the notice of proposed rulemaking, the Department believes

that airlines should not charge families to sit together.

Family Seating in Air Transportation: Regulatory Impact Analysis 27

Appendix A Implementation cost estimates at 3 and 7 percent

discount rates

Table A-1: Implementation costs per airline, scaled by carrier size, 3% discount rate

Total passengers

(2022, millions)

Implementation costs

(2022 $, millions)

Annualized

Airline

Total

5 years

10 years

Non-NDC-capable airlines

158.8

32.0

7.0

3.8

Allegiant

16.9

3.4

0.7

0.4

Delta

141.9

28.6

6.2

3.4

NDC-capable airlines

161.1

16.2

3.5

1.9

Hawaiian

10.0

1.0

0.2

0.1

Spirit

38.4

3.9

0.8

0.5

United

112.7

11.4

2.5

1.3

Implementation cost

Estimate 1 (Only non-NDC airlines incur costs)

158.8

32.0

7.0

3.8

Estimate 2 (NDC airlines incur 50% cost)

319.9

48.2

10.5

5.7

Sources: Delta Airlines’ 2019 and 2022 10-k annual report, Air Carrier Statistics (Form 41 Traffic) T-100 data.

Note: Total cost of implementation is estimated to be 10% of total IT cost ($2.02 per passenger) for airlines that do not

yet have NDC capabilities (Estimate 1), and 5% of total IT costs for those that do (Estimate 2). Annualized costs assume a

3% annual discount rate.

Table A-2: Implementation costs per airline, scaled by carrier size, 7% discount rate

Total passengers

(2022, millions)

Implementation costs

(2022 $, millions)

Annualized

Airline

Total

5 years

10 years

Non-NDC-capable airlines

158.8

32.0

7.8

4.6

Allegiant

16.9

3.4

0.8

0.5

Delta

141.9

28.6

7.0

4.1

NDC-capable airlines

161.1

16.2

4.0

2.3

Hawaiian

10.0

1.0

0.2

0.1

Spirit

38.4

3.9

0.9

0.6

United

112.7

11.4

2.8

1.6

Implementation cost

Estimate 1 (Only non-NDC airlines incur costs)

158.8

32.0

7.8

4.6

Estimate 2 (NDC airlines incur 50% cost)

319.9

48.2

11.8

6.9

Sources: Delta Airlines’ 2019 and 2022 10-k annual report, Air Carrier Statistics (Form 41 Traffic) T-100 data.

Note: Total cost of implementation is estimated to be 10% of total IT cost ($2.02 per passenger) for airlines that do not

yet have NDC capabilities (Estimate 1), and 5% of total IT costs for those that do (Estimate 2). Annualized costs assume a

7% annual discount rate.