University of Alabama at Birmingham University of Alabama at Birmingham

UAB Digital Commons UAB Digital Commons

All ETDs from UAB UAB Theses & Dissertations

2015

Chief Executive O=cer Characteristics In Relationship With Chief Executive O=cer Characteristics In Relationship With

Patient Experience Scores Of Hospital Value Based Purchasing Patient Experience Scores Of Hospital Value Based Purchasing

Christina Galstian

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.uab.edu/etd-collection

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Galstian, Christina, "Chief Executive O=cer Characteristics In Relationship With Patient Experience Scores

Of Hospital Value Based Purchasing" (2015).

All ETDs from UAB

. 1689.

https://digitalcommons.library.uab.edu/etd-collection/1689

This content has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the UAB Digital Commons, and is

provided as a free open access item. All inquiries regarding this item or the UAB Digital Commons should be

directed to the UAB Libraries O=ce of Scholarly Communication.

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER CHARACTERISTICS IN RELATIONSHIP WITH

PATIENT EXPERIENCE SCORES OF HOSPITAL VALUE BASED PURCHASING

by

CHRISTINA GALSTIAN

LARRY HEARLD, COMMITTEE CHAIR

NANCY BORKOWSKI

STEPHEN O’CONNOR

RICHARD JACKSON

A DISSERTATION

Submitted to the graduate faculty of The University of Alabama at Birmingham,

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Science in Health Services Administration

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA

201

Copyright by

Christina Galstian

2015

iii

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER CHARACTERISTICS IN RELATIONSHIP WITH

PATIENT EXPERIENCE SCORES OF HOSPITAL VALUE BASED PURCHASING

CHRISTINA GALSTIAN

ABSTRACT

Patient experience scores have become important indicators of value in

healthcare. This study was the first of its kind to examine CEO gender, tenure, and

education in relationship with patient experience scores and all other value based

purchasing scores, such as outcome, efficiency, clinical process of care, and total

performance scores. This study suggested that hospitals with certain types of CEOs may

perform better with respect to patient experiences and other value based purchasing

scores.

The primary analysis of this study was to examine the impact of hospital CEO

characteristics (tenure, education, gender) on patient experience scores. A supplementary

analysis examined CEO characteristics (tenure, gender, education) in relationship with all

other value based purchasing scores (outcome, efficiency, clinical process of care, and

total performance). The study controlled for a broad spectrum of organizational and

market characteristics.

Univariate, bivariate, and multivariate analysis techniques were used for the

purpose of statistical analysis. The OLS (ordinary least square) block modeling strategy

examined both primary and supplementary relationships of dependent and independent

variables. The most robust finding of this study was related to gender. Specifically, those

hospitals led by female CEOs were associated with significantly higher patient

experience scores and other value based purchasing scores.

iv

Findings from this study open new doors for future research of CEO attributes in

the healthcare industry and will provide useful insights for the recruitment and selection

processes used by hospital boards and other executive recruiters that are interested in

hiring CEOs who will improve patient experience and other value based purchasing

scores. Therefore, the study provides important information for identifying ways to

improve patient experience.

Keywords: CEO characteristics, patient experience scores, value based purchasing,

HCAHPS, healthcare

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................. iii

LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................... viii

CHAPTER

1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1

Study Purpose ......................................................................................................... 2

Study Significance .................................................................................................. 5

Dissertation Outline ................................................................................................ 5

2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ............................ 7

Theoretical Framework ............................................................................................ 12

Chief Executive Officer Characteristics ................................................................... 15

CEO Education ..................................................................................................... 15

Terminal vs. Non-Terminal Degrees ..................................................................... 17

Clinical Terminal vs. Non-Terminal Degrees ........................................................ 18

CEO Tenure .......................................................................................................... 20

CEO Gender (Female vs. Male CEOs) .................................................................. 21

3 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................. 23

Research Design ...................................................................................................... 23

Study Population...................................................................................................... 23

Data Sources ......................................................................................................... 23

Measures ................................................................................................................. 25

Dependent Variable .............................................................................................. 25

Independent Variables........................................................................................... 26

Gender ............................................................................................................ 26

Tenure............................................................................................................. 27

Education ........................................................................................................ 28

Control Variables .................................................................................................. 28

Hospital Characteristics ................................................................................... 28

Market Characteristics..................................................................................... 30

Merging Data ........................................................................................................ 32

Statistical Analysis................................................................................................... 34

vi

Page

4 ANALYSIS AND PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS ............................................. 36

Descriptive Results .................................................................................................. 39

Bivariate Results ...................................................................................................... 39

Correlation Analysis for Continuous Variables ..................................................... 39

Patient Experience Domain Scores ........................................................................ 39

Clinical Process of Care Domain Scores ............................................................... 39

Efficiency Domain Scores ..................................................................................... 40

Outcome Domain Scores....................................................................................... 40

Total Performance Scores ..................................................................................... 40

One-way ANOVA ................................................................................................... 42

Testing for Differences in the Means between Multiple Groups ............................ 42

Gender ............................................................................................................ 42

Clinical Terminal Degree ................................................................................ 43

Terminal Degree ............................................................................................. 44

Multivariate Results ................................................................................................. 45

Regression Analysis .............................................................................................. 45

Hierarchical Multiple Regression ............................................................................. 45

Patient Experience of Care Domain Scores...................................................... 46

Clinical Process of Care Domain Scores .......................................................... 49

Outcome Domain Scores ................................................................................. 50

Efficiency Domain Scores ............................................................................... 52

Total Performance Scores................................................................................ 54

5 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS .................................................................... 57

CEO Education ..................................................................................................... 57

CEO Tenure .......................................................................................................... 60

CEO Gender ......................................................................................................... 60

Control Variables .................................................................................................. 61

Limitations and Opportunities for Future Research............ ....................................... 64

Study Implications............ ....................................................................................... 65

Implications for Future Research........................................................................... 65

Implications for Practice ....................................................................................... 66

Conclusion............ ................................................................................................... 67

REFERENCES .............................................................................................................. 68

APPENDICES ............................................................................................................... 89

A INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD APPROVAL ......................................... 89

B CMS PE DATA SAMPLE PAGE ..................................................................... 91

C CHA MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY ................................................................. 93

D HOSPITAL WEBSITE CEO PAGE .................................................................. 95

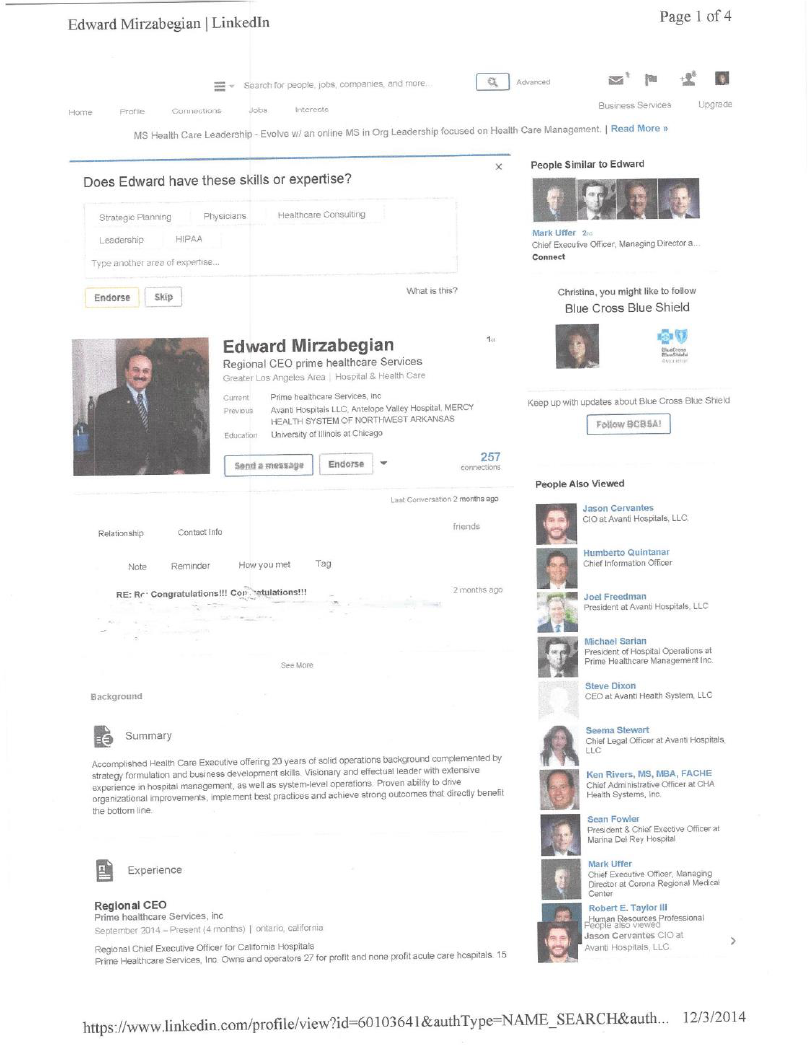

E LINKEDIN CEO PROFILE PAGE ................................................................... 97

F CA CENSUS DATA ......................................................................................... 99

vii

Page

G CENSUS DATA: MARGIN OF ERROR ........................................................ 101

H TERMINAL DEGREE LIST, UNITED STATES ........................................... 103

I CLINICAL TERMIAL DEGREE LIST ............................................................ 106

J HCAHPS SURVEY ......................................................................................... 108

viii

LIST OF TABLES

Page

1 HCAHPS Survey Questions ........................................................................................ 9

2 Study Variables, Measures, and Data Sources ........................................................... 33

3 Hospital and CEO Categorical Characteristics (N=294) ........................................... 37

4 Mean and Standard Deviations for Continuous Variables .......................................... 38

5 Correlation Matrix Continuous Variables .................................................................. 41

6 ANOVA. Dependent Variable Differences between Male and Female Groups .......... 43

7 ANOVA. Dependent Variable Differences between Clinical Terminal (CT)

And Non Clinical Terminal (NCT)........................................................................... 44

8 ANOVA. Dependent Variable Differences between Terminal (T) and Non-

Terminal (NT) ......................................................................................................... 45

9 Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression Models for CEO Characteristics

(independent variable) and Patient Experience (dependent variable) ........................ 48

10 Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression Models for CEO Characteristics

(independent variable) and Clinical Process of Care (dependent variable) ................ 50

11 Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression Models for CEO Characteristics

(independent variable) and Outcome (dependent variable) ....................................... 52

12 Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression Models for CEO Characteristics

(independent variable) and Efficiency (dependent variable) ..................................... 54

13 Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression Models for CEO Characteristics

(independent variable) and Total Performance (dependent variable) ......................... 56

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

Patient experience has emerged in recent years as a centerpiece of efforts to

improve the U.S. healthcare system. For example, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services (CMS) incentivizes or penalizes hospitals based on patient experiences during

an inpatient stay. Patient experience is derived from measuring patients' perceptions of

their hospital experiences (communication with nurses and doctors, the responsiveness of

hospital staff, the cleanliness and quietness of the hospital environment, pain

management, communication about medicines, discharge information, overall rating of

hospital, and whether or not they would recommend the hospital) (CMS, 2014).

Measuring patient experience is not a new concept in healthcare. In 2002, the

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey,

a tool to measure patient experiences during a hospital stay was approved as part of the

Deficit Reduction Act of 2005. As a part of the Act, the final IPPS rule stipulated that

IPPS hospitals must continuously collect and submit HCAHPS data to CMS in order to

receive their full IPPS annual payment update. Those IPPS hospitals that fail to publicly

report the required quality measures, which include the HCAHPS survey, may receive an

annual payment update that is reduced by 2.0 percentage points (www.hcahpsonline.org,

2014).

This initiative was a combined effort between Agency for Healthcare Quality and

Research (AHRQ) and CMS (ahrq.gov, 2014). The purpose of HCAHPS reporting was to

2

promote accountability, increase efforts to improve patient centeredness, promote care

coordination, and improve patient experiences during hospital stays (IOM, 2006).

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, also known as the

Affordable Care Act (ACA), (P.L. 111-148) includes HCAHPS among the measures to

be used to calculate value based incentive payments in the Hospital Value Based

Purchasing program, beginning with discharges in October 2012

(www.hcahpsonline.org). HCAHPS became part of a broader CMS strategy to promote

value based purchasing (VBP) (PPACA; Section 1003). The purpose of value based

purchasing is to offer the highest quality per each dollar spent, enhance patient

experience outcomes, and address concerns of the solvency of the U.S. healthcare system

(Porter, 2010).

Consequently, healthcare organizations are being asked to do more with less

reimbursement, less capital, and fewer resources (O'Connor, Trinh, & Shewchuk, 1995).

Value based purchasing is comprised of four key elements from 2013 through 2015 (1)

clinical process of care, (2) patient experience, (3) outcome, and (4) efficiency. Those

four elements combined create a total performance score (TPS) used by CMS to calculate

hospital incentives and penalties (cms.gov). Patient experience is weighted as 30% of the

total performance score calculation, and therefore, carries significant financial

implications for hospitals. Consequently, value based purchasing has been forcing

hospitals to reconsider their care delivery systems and leadership practices to identify

ways to provide higher value care at a lower cost (Holzer & Minder, 2011).

Study Purpose

Providing a positive patient experience is each individual’s responsibility within a

healthcare organization. CEOs, however, play an especially important role, as they are in

3

charge of setting the organizational vision and strategic goals, including those related to

providing a positive patient environment and patient experience.

Effective hospital CEOs are equipped with the knowledge and skills needed to

motivate and lead the process improvement initiatives after thorough organizational (e.g.,

needs, resources, cultures, skills) and environmental analysis. Their ability to execute

timely and effective change can be the driving force behind the success of an

organization (Kaufman, 2013). Given the CEO’s significant role in improving

performance, an important research question that guided this study was:

Are CEOs characteristics associated with patient experience outcomes?

Because patient experience outcomes have become important indicators of

organizational performance and can differentiate hospitals in the marketplace, efforts to

promote positive patient experience require strategic leadership, timely and effective

response to regulatory changes, and a commitment to quality and transparency (Merlino

& Raman, 2013). Patient centered leadership in the context of this study has been defined

as leadership that rests on values of patient centered care; is respectful of and responsive

to patient preferences, needs, and values; and ensures that patient values guide all clinical

decisions (IOM, 2001; Thibault, 2013). When organizations satisfy a consumer’s needs

and preferences, they are actually delivering value and/or increased perceptions of value

(Burden, 1998), which in healthcare translates into improved patient experience scores.

CMS defines patient experience as a measure of patient centeredness, delivering

value to the patient by meeting their needs and expectations (CMS, 2014). Patient

experience has also been defined as the sum of all interactions, shaped by an

organization’s culture, that influence patient perceptions across the continuum of care

(The Beryl Institute, 2014). These perceptions are recognized, understood, and

4

remembered by the patients based on their individual experiences. Therefore, patient

experience, in the context of this study, was defined as patient perceptions of the care

delivery experience by a hospital during an inpatient stay. .

It was the premise of this study that CEOs can provide value to their organizations

by practicing patient centered leadership and inspiring patient focused innovative

behaviors that can stimulate positive patient experiences. This includes their role as

“boundary spanners” in interpreting and defining expectations of various stakeholder

groups (e.g., government, payers, consumers) for the purpose of implementing strategies

and motivating and empowering staff to promote patient-friendly environments.

CEO attributes, such as their education, gender, and tenure, may reflect

differential skill and abilities to take on these roles and engage in these behaviors, and

thus may play an important role in cultivating a patient centered environment. For

example, MD CEOs, through extensive clinical training and education, have been taught

to practice medicine by putting their patients first, and therefore may facilitate better

patient experiences.

Despite the potentially important role of the hospital CEO, little published

research has examined whether CEO characteristics are associated with patient outcomes.

This is especially the case with patient experiences due to its relatively recent emergence

as a priority for hospitals. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to empirically

examine whether CEO characteristics such as gender, tenure, and education were

associated with reported patient experience outcomes.

Other value based purchasing domains (e.g., efficiency, clinical outcomes) have

been recently introduced as mandatory reporting by CMS; however, research establishing

the validity of these domain scores as hospital performance metrics is still in its infancy.

5

Therefore, this study included these other domains as outcomes in an exploratory,

supplementary analysis to provide preliminary evidence regarding the consistency of the

relationships between CEO characteristics and different domains of hospital performance.

Study Significance

Public reporting of patient experience scores became mandatory in 2013.

Consequently, CEOs and other hospital leaders increasingly view patient experience and

strategies for its improvement as important determinants for the future success of their

organizations (Manary, Staelin, Kosel, Schulman, & Glickman, 2013). Thus, the findings

from this study are timely and important for providing insight into ways to foster patient

centered environments and enhanced patient experience scores. The findings may also

provide useful insights for CEO recruitment and selection processes used by hospitals

and other healthcare executive recruiters. The supplementary analysis that incorporates

the additional domain scores (outcome, efficiency, clinical process of care, and total

performance) may also provide a foundation and benchmarks for future research as well

as additional insights into CEO recruitment and selection processes.

Dissertation Outline

Chapter 2 will review the existing empirical literature related to hospital patient

experience. First, it will explore the history of patient experience, its measurement, and

its effects on other outcomes of interest. Next, the chapter will review the literature on

leadership, organizational, and market characteristics correlated with patient experience.

Finally, Chapter 2 will present the study hypotheses regarding the association between

CEO characteristics and patient experience.

Chapter 3 will provide a description of the research design, sample data sources,

methods of data collection, measures, and analytic plan. Chapter 4 will present the results

6

of the statistical analysis; univariate, bivariate and multivariate analysis. Finally, chapter

5 will discuss the findings, study limitations, opportunities for future research, and

implications.

7

Chapter 2

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Reporting of hospital value based purchasing measures went into effect in 2013 as

a standard for measuring hospital performance for the delivery of healthcare services

(ACA, Section 3001a). Hospital value based purchasing measures and reporting

standards were developed by the CMS, Department of Health and Human Services

(HHS), National Quality Forum (NQF), National Quality Measures Clearinghouse

(NQMC), and others.

Hospital value based purchasing had two main components called domains in

2013; the clinical process of care domain and the patient experience of care domain.

Additional domains of efficiency and outcome were added in 2014. The domains are

weighted to calculate a total performance score. In 2013, patient experience score

comprised 30% and the clinical process of care domain 70% of total performance score.

In 2014, the clinical process of care domain was 20%, the outcome domain was

30%, efficiency domain 20%, and the patient experience domain was 30% of the total

performance score. Each year the federal rule determines how each domain will be

weighted to calculate the total performance score, which in turn is used to calculate

adjustments to Medicare reimbursements for services rendered (D. M. Cosgrove et al.,

2012; Medicare.gov, 2014). Eighty-one percent of the IPPS hospitals have already

implemented and/or are implementing new processes/policies and forming new formal

positions dedicated to patient experience in order to improve reimbursements (Balbale,

8

2014; Batailler et al., 2014; Bertakis & Azari, 2011; Beryl Institute, 2014; Hodnik, 2012;

Kolstad & Chernew, 2009).

Patient experience has been defined as the sum of all interactions, shaped by an

organization’s culture, that influence patient perceptions across the continuum of care

(The Beryl Institute, 2014). These perceptions are recognized, understood, and

remembered by the patients based on their individual experiences. Patient experience

measures patient centeredness, whether value was delivered, and whether patient’ needs

and expectations were met (CMS, 2014). Patient experience score is measured with the

HCAHPS survey (Table 2 and Appendix J). HCAHPS was identified in Section 3001 of

the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 as a measure to be included in the

Hospital Value Based Purchasing (HVBP) program payments made as of Fiscal Year

2013 (CMS, 2011).

HCAHPS survey questions measure patient perceptions of care experiences by

focusing on patient interactions during healthcare encounters, whether or not certain

events or behaviors occurred, and/or how often they occurred (Long, 2012). The

HCAHPS survey (Table 1) is composed of 27 items: 18 substantive items that encompass

critical aspects of the hospital experience; four items to skip patients to appropriate

questions; three items to adjust for the mix of patients across hospitals; and two items to

support congressionally mandated reports (CMS.org).

More specifically, HCAHPS focuses on nurse communication, doctor

communication, staff responsiveness, pain management, medication communication,

discharge information, cleanliness, quietness of the hospital environment, overall rating

of the hospital, and patient willingness to recommend its services (CMS, 2014).

9

Furthermore, it assesses whether the patient’s visit was patient centered or not

(Tsimtsiou, Kirana, & Hatzichristou, 2014).

Table 1

HCAHPS Survey Questions

HCAHPS

Survey Questions

Nurse Communication/Care

During this hospital stay, how often did nurses treat

you with courtesy and respect?

During this hospital stay, how often did nurses listen

carefully to you?

During this hospital stay, how often did nurses explain

things in a way you could understand?

During this hospital stay, after you pressed the call

button, how often did you get help as soon as you

wanted it?

Doctor Communication/Care

During this hospital stay, how often did doctors treat

you with courtesy and respect?

During this hospital stay, how often did doctors listen

carefully to you?

During this hospital stay, how often did doctors explain

things in a way you could understand?

Staff responsiveness

During this hospital stay, did you need help from

nurses or other hospital staff in getting to the bathroom

or in using a bedpan?

How often did you get help in getting to the bathroom

or in using a bedpan as soon as you wanted?

Pain management

During this hospital stay, did you need medicine for

pain?

During this hospital stay, how often was your pain well

controlled?

During this hospital stay, how often did the hospital

staff do everything they could to help you with your

pain?

Medications Communication

During this hospital stay, were you given any medicine

that you had not taken before?

Before giving you any new medicine, how often did

hospital staff tell you what the medicine was for?

Before giving you any new medicine, how often did

hospital staff describe possible side effects in a way

you could understand?

Cleanliness & Quietness

During this hospital stay, how often were your room

and bathroom kept clean?

During this hospital stay, how often was the area

around your room quiet at night?

10

CMS requires hospitals to administer a minimum of 300 surveys over one

calendar year to a random sample of adult patients between 48 hours and six weeks after

discharge (www.hcapsonline.org; 2013). Completed HCAHPS are submitted to the CMS

data warehouse by hospitals. Incomplete surveys are considered invalid and removed

from the system. Unweighted and weighted domain scores, including patient experience,

range from 0 to 100 (CMS, 2014).

Care instructions before/after

discharge

After you left the hospital, did you go directly to your

own home, to someone else’s home, or to another

health facility?

During this hospital stay, did doctors, nurses or other

hospital staff talk with you about whether you would

have the help you needed when you left the hospital?

During this hospital stay, did you get information in

writing about what symptoms or health problems to

look out for after you left the hospital?

During this hospital stay, staff took my preferences and

those of my family or caregiver into account in

deciding what my health care needs would be when I

left.

When I left the hospital, I had a good understanding of

the things I was responsible for in managing my health.

When I left the hospital, I clearly understood the

purpose for taking each of my medications.

Understanding the Patient

During this hospital stay, were you admitted to this

hospital through the Emergency Room?

In general, how would you rate your overall health?

In general, how would you rate your overall mental or

emotional health?

What is the highest grade or level of school that you

have completed?

Are you of Spanish, Hispanic or Latino origin or

descent?

What is your race? Please choose one or more.

What language do you mainly speak at home?

Overall Rating of Hospital

Using any number from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst

hospital possible and 10 is the best hospital possible,

what number would you use to rate this hospital during

your stay?

Would you recommend this hospital to your friends

and family?

11

As suggested by the different domains that constitute the overall total

performance score, patient experience is distinct from other aspects of hospital

performance and should be measured independently. For example, many hospitals today

measure clinical quality outcomes to meet regulatory compliance and patient/market

expectations. However, patient experience differs from clinical quality outcomes because

of its focus on subjective assessments of care processes, also viewed as abstract

expectations for quality (O'Connor, Trinh, & Scewchuk, 2001). Likewise, patient

experience differs from patient satisfaction because of its emphasis on subjective views

about hospital inpatient care processes based on experiences, perceptions, and specific

processes that are expected to occur during an inpatient hospital stay (Bleich, Özaltinb, &

Murrayc, 2009; Elliott et al., 2010; Price et al., 2014).

Because patient experience domain focuses on patient experiences and specific

care processes, patient centered care is believed to be a critical input into better patient

experience scores. In fact, a study of 69 U.S. hospitals revealed that patient centered and

compassionate care practices were significantly and positively associated with higher

patient experience scores and the likelihood of patients recommending a hospital

(McClelland, 2014).

Care that is patient centered is “respectful of and responsive to individual patient

preferences, needs, and values, and ensures that patient values guide all clinical

decisions” (IOM, 2001. p. 6). Patient centeredness enables patient access to timely and

appropriate care by skillful personnel at all levels of patient interactions, starting from the

patient’s admission to the facility through discharge and beyond. It builds compassionate

and caring relationships that bridge demographic, and economic differences, and engages

the patients in their own care; considers family values, religious beliefs, age, lifestyles,

12

and cultural diversities; makes them feel safe, comfortable, and cared-for (Bush, 2012; A.

M. Epstein, Zhonghe, Orav, & Jha, 2005; R. M. Epstein, Fiscella, Lesser, & Stange,

2010; Jadoo et al., 2013; Long, 2012; Tsimtsiou et al., 2014). Patient centered care

contributes to culturally sensitive communication, without which patients would feel

devalued and lacking in emotional support (Bramley, 2014; J. Chen, Koren, Munroe, &

Yao, 2014).

Importantly, although patient experience scores are used for calculating hospital

incentives, they can be used by multiple audiences. For consumers, patient experience

scores are intended to increase transparency and informed care decision making. For

hospitals and other healthcare organizations, patient experience scores might be used to

identify problems related to patient centered practices as well as reinforce and motivate

change to resolve those problems. States, federal agencies, and other regional/national

agencies could potentially use patient experience scores and related empirical evidence to

make informed policy decisions (ACA, Section 3015; ahrq.gov). Consequently,

understanding factors that influence patient experience are important for multiple health

care stakeholders. In the following section, Transformational Leadership Theory (TLT)

will be used to offer several hypotheses about why certain CEO characteristics may be

associated with better patient experience scores.

Theoretical Framework

Burns introduced the TLT in 1978. The theory suggests that leader characteristics

and behaviors can transform organizations and people to achieve better morale,

motivation, and outcomes (Burns, 1978). In 1985, Bass (1985) emphasized the

psychological components of transformational leadership and its influences on follower

motivation. According to Bass, transformational leaders are considered moral leaders

13

because they appeal to the values and ideals of their followers (Kuhnert, 1994; Kuhnert &

Lewis, 1987). In 1991, Covey wrote:

[T]he goal of the transformational leadership is to “transform” people and

organizations in a literal sense – to change them in mind and heart; enlarge vision,

insight, and understanding; clarify purposes; make behavior congruent with

beliefs, principles, or values; and bring about changes that are permanent, self-

perpetuating, and momentum building. (p. 287)

Consistent with these arguments, research has shown that a transformational CEO

develops and implements an organization’s vision, values, and goals. He/she motivates

positive follower behaviors through role modeling and mentoring; collaborates with

stakeholders and engages them towards achieving organizational goals, improves job

satisfaction and decreases burn out, stimulates strong stakeholder relationships and

alignment, enables compassionate and outcome driven cultures, empowers teamwork and

innovation, and implements evidence based practices and shared decision making

(Garman, Butler, & Brinkmeyer, 2006; Bass, 2008; Burns, 1978; D. Cosgrove et al.,

2012; IHI, 2014; Kaufman, 2013; Lo, Ramayah, & De Run, 2010; Luxford, Safran, &

Delbanco, 2011; Munir & Nielsen, 2009; Nielsen, Yarker, Randall, & Munir, 2009;

O'Reilly, Caldwell, Chatman, Lapiz, & Self, 2010; Resick, Weingarden, Whitman, &

Hiller, 2009; Rolfe, 2011; Sanders & Shipton, 2012; Tse, Huang, & Lam, 2013;

Vinkenburg, van-Engen, Eagly, & Johannesen-Schmidt, 2011; Wang & Howell, 2010;

Weberg, 2010). Likewise, healthcare researchers have found transformational leadership

to be positively associated with employee attitudes and intentions to follow quality and

safety practices for measurable patient outcomes (Colbert, 2008; Groves & LaRocca,

2012; Lee, Almanza, Jang, Nelson, & Ghiselli, 2013; Ling & Lubatkin, 2008).

14

It was the contention of this study that patient experience requires high

performing cultures that rest on values of patient centered care, cultures that are

cultivated and sustained by hospital leaders (Thibault, 2013). Research has shown that a

leader’s compassionate and patient centered behaviors can influence the degree to which

an organization is patient centered, an important determinant for patient experience

(Hartog & Belschak, 2012; O'Reilly et al., 2010). The focus of this study was on three

characteristics (education, tenure, gender) that previous research has identified as

indicators of a CEO’s transformational abilities.

Education has been identified as an important transformational leadership

attribute linked to patient centered care, in part because it enables leaders to practice

evidence based leadership (Brown & Posner, 2001; Covey, 2007; A. M. Epstein et al.,

2005; R. M. Epstein et al., 2005; Pedler, 1991). Similarly, CEO tenure is associated with

collaboration, adaptability, innovation, and trust, all of which may be important for

cultivating a culture of patient centered care. Finally, gender has been described in the

literature as a transformational characteristic that reflects differences in intuitiveness,

collaborativeness, compassion, and flexibility (Hambrick & Finkelstein, 1991, 1996;

Lewis, Walls, & Dowell, 2014; X. Luo, V. K. Kanuri, & M. Andrews, 2013b)

Thus, one could argue that hospitals that achieve high level(s) of patient

experience are likely to be led by executives/CEOs who can stimulate and sustain patient

centered values (Davis, Schoenbaum, & Audet, 2005; Latham, 2013), and CEO

characteristics that reflect transformational abilities of CEOs may be associated with

better patient experience scores.

15

Chief Executive Officer Characteristics

CEO Education

There is growing sentiment that healthcare leadership in the United States has to

be reconfigured to meet the needs of the reformed healthcare system to deliver timely

care in more complex care delivery systems, such as integrated care networks and

accountable care organizations (Ricketts & Fraher, 2013). The transformation of the U.S.

healthcare system requires well educated leaders (IOM, 2013). Of specific relevance for

this study, successful and effective patient experience practices have been shown to

require education that is focused on delivering value and meeting patient /family and

industry needs, with more education being associated with better patient services and

higher patient experience scores (Robert, Waite, Cornwell, Morrow, & Maben, 2014).

Research has also found CEO education to be associated with various leadership

practices and organizational outcomes, such as evidence based practices, innovation, and

improved financial performance (Bhagat, Bolton, & Subramanian, 2010; Gottesman &

Morey, 2006; Jalbert, Rao, & Jalbert, 2002).

For these reasons, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has

placed a significant emphasis on developing formal leadership education models that

foster improved patient outcomes (Rodrigue, Seoane, Gala, Piazza, & Amedee, 2012).

Formal graduate education can produce effective and innovative leaders, lead to better

care, improve health, and lower costs (Thibault, 2014) because it supports an

understanding of the theories and practices of successful leadership strategies and

provides access to the existing body of empirical literature (Becker, 1970).

Formal graduate education can also equip CEOs with the necessary technical,

human, business, and conceptual skills (Brooks, 1994; Reilly, 2004). Specifically, formal

16

graduate programs often emphasize important leadership skills such as effective

communication, interpersonal skills, managing healthcare resources, and measuring and

managing quality data and activities (Brooke, Hudak, Finstuen, & Trounson, 1998).

Thus, Master’s, doctoral, and other advanced graduate degrees have been acknowledged

in the literature as important factors predictive of better workplace environments and care

delivery systems that are associated with better pain management practices, lower

medical/administrative errors, reduced adverse occurrences, lower mortality rates, and

other quality performance outcomes (Aiken, Clarke, Cheung, Sloane, & Silber, 2003;

Blegen, Vaughn, & Goode, 2001; Garman, Goebel, Gentry, Butler, & Fine, 2010;

Gillespie, Chaboyer, Wallis, & Werder, 2011; Kim, 2014; Trinkoffa et al., 2014).

Consistent with this thinking, Garman et al. (2006, 2010) illustrated that

leadership competencies are typically taught at the graduate/post graduate level.

Healthcare Leadership Alliance (HLA) is a leadership model with a “cluster of

knowledge, skills and attitudes related to role and performance,” that is taught at a

graduate level ( Garman et al., 2006; Shewchuk, O’Connor, & Fine, 2005, p. 33). HLA is

a framework developed by the consortium of the six largest healthcare associations

(ACHE, ACPE, AONE, HFMA, HIMSS, MGMA, ACMPE) that allows leaders to

establish vision, enhance organizational goals, build trust and motivation, encourage

teamwork, support diversity, promote environments where employees contribute to their

full potential, and achieve higher levels of performance and quality outcomes (Garman et

al., 2006). HLA competencies include effective communication, stakeholder relationship

management, professionalism, leadership knowledge, business management, healthcare

systems understanding, resources management, governance, strategic planning, risk

management, quality/safety management, and more (Stefl, 2008).

17

Beyond healthcare, research has found that higher levels of formal education are

associated with better organizational performance such as higher profits and greater

market share (Besley, Montalvo, & Reynal-Querol, 2011; Hambrick & Aveni, 1992;

Hambrick & Mason, 1984). Executives with higher levels of formal education are more

successful at managing change, facilitating organizational adaptation, and motivating

followers to improve performance (Baker, Mathis, & Stites-Doe, 2011). Higher education

level, in general, is associated with leaders’ receptiveness to change and willingness to

take risks (Wiersema & Bantel, 1992).

Likewise, Lewis et al. (2014) found that financial decision-making and strategic

behaviors vary as a function of CEO formal educational background; organizations led by

CEOs with an MBA and/or other higher degrees spend more on capital expenditures, take

on more debt, and make more diversifying acquisitions than firms led by less educated

CEOs. Kimberly and Evanisko (1981) also found that CEO education level was

positively associated with the likelihood of adopting innovative technological and

administrative strategies.

Terminal vs. Non-Terminal Degrees

While some have described the Master’s degree as the terminal degree for

healthcare management practice this study defined a terminal degree as a doctoral degree

as it is the highest academic degree approved in a given field. Terminal degrees include

research and professional doctorate degrees such as Doctor of Medicine (MD), Doctor of

Psychology (PsyD), Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Doctor of Science (DSC), Doctor of

Education (EdD), Doctor of Public Health (DrPH), and other doctoral degrees.

Research has found that leaders with terminal degrees are associated with

transformational leadership behaviors and techniques such as inspiring, enabling,

18

encouraging, and modeling (Brown & Posner, 2001; Covey, 2007; Pedler, 1991).

Furthermore, graduate education which is grounded in theory, research, and utilization of

empirical literature, has shown to encourage use of evidence based leadership strategies

and has led to improved patient centered care (A. M. Epstein et al., 2005; R. M. Epstein

et al., 2005). The use of such evidence can help leaders make better decisions and

develop more effective strategies in response to changing external environments, such as

the increased emphasis on patient experience.

Therefore, it was hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1: Hospitals led by CEOs that hold terminal degrees will be

associated with higher patient experience scores compared to those hospitals led by

CEOs with non-terminal degrees.

Clinical Terminal vs. Non-Clinical Terminal Degrees

Patient experience requirements raise another question, whether CEOs with

clinical terminal degrees or non-clinical terminal degrees can produce better patient

experience outcomes and contribute to the ongoing discussion of whether healthcare

organizations are better off run by CEOs with a clinical terminal degrees, such as MDs

(Falcone & Satiani, 2008). Most U.S. hospitals have been traditionally led by non-clinical

non-terminal degree CEOs. In 1935, 35% of U.S. hospitals were led by medical doctors,

according to the Journal of Academic Medicine (Falcone & Satiani, 2008). In 2009,

however, out of 6,500 U.S. hospitals, only 235 were led by MD executives in 2009

(Falcone & Satiani, 2008; Goodall, 2011b; Gunderman & Kanter, 2009).

CEOs with a clinical terminal degree or a non-clinical terminal degree may be

successful , however, a new breed of hospital CEO may be required to achieve better

patient centered outcomes (Schultz & Pal, 2004). Research suggests that, because clinical

19

CEOs spend many years in direct patient care, they may have an aptitude and desire to

communicate in ways that are more effective in promoting patient centered culture

(Mountford & Webb, 2009).

Clinical terminal degree CEOs may also cultivate more patient centered cultures

by acting as role models for their medical staff and may be more effective at attracting

gifted medical personnel (Goodall, 2011a, 2011b; Goodall, Lawrence, & Oswald, 2011;

Mäntynen et al., 2014). CEOs can also play a critical role in uniting the clinical staff and

overcoming potential resistance from physicians, patients, and other stakeholders in

implementing more patient centered delivery models (Colla, Lewis, Shortell, & Fisher,

2013).

Consistent with these arguments, a recent study by the UK National Health

Service (NHS) found that in 11 cases of attempted improvement in hospital quality

performance, organizations with stronger MD leadership were the most successful

(Fitzgerald, 2006). A 2011 study of 300 top rated hospitals found a strong positive

association between the clinical quality of a hospital and whether the CEO was an MD

(Goodall, 2011a). Another study by McKinsey and the London School of Economics

found that hospitals with the greatest MD participation in management roles scored 50%

higher on important drivers of hospital performance than those with low levels of MD

participation (Castro, Dorgan, & Richardson, 2008).

Collectively, these findings suggest that:

Hypothesis 2: Hospitals led by CEOs that hold clinical terminal degree will be

associated with higher patient experience scores compared to hospitals led by CEOs that

do not hold clinical terminal degree.

20

CEO Tenure

Empirical research suggests that longer CEO tenure is negatively associated with

organizational change, growth, and performance (Balkin & Gomez-Mejia, 1987; Bizjak,

Lemmon, & Naveen, 2009; D. Chen & Zheng, 2012; Finkelstein & Hambrick, 1990; Luo

et al., 2013b). In the general business literature, long tenure is considered 11 years or

longer (Henderson, Miller, & Hambrick, 2006; Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967). However, in

the hospital industry, the CEO turnover rate has increased and the average CEO tenure

has decreased dramatically (ACHE, March 2014, Report). In 2012, one study reported an

average hospital CEO tenure close to 5.5 years (Khaliq, Thompson, Walston, Saste, &

Kramer, 2012). According to Becker’s Hospital Review (2014), this number dropped

even further to 3.5 years in 2014.

Research has shown that shorter tenured and/or newly appointed CEOs are more

likely to collaborate with their teams, focus more on building trust, and are more

willing to pursue innovative strategies in comparison with longer tenured CEOs

(Finkelstein & Hambrick, 1990). CEOs learn critical knowledge early in their tenure,

which can taper off as years progress (Hambrick & Finkelstein, 1991). Shorter CEO

tenure is associated with greater adaptability, more risk taking, and readiness for

change, while longer tenure is associated with being more cautious and conservative

when making change related decisions (Gerowitz, 1998; Hitt & Tyler, 1991).

Longer tenured CEOs slowly lose their knowledge and skill development and

narrow information search, rely more on the application of previous experiences, and

knowledge to new circumstances instead of accruing new skills (Hambrick, Cheo, &

Chen, 1996; Hambrick & Finkelstein, 1991, 1996). Longer tenured CEOs become

more institutionalized, more risk averse to preserve previous gains, resistant to change,

21

and less aligned with customer demands and market expectations (Lewis et al., 2014;

Simsek, 2007). Similarly, longer tenure has been linked with an inability to keep up

with market expectations and be responsive to customer preferences (Henderson et al.,

2006; X. Luo, V. Kanuri, & M. Andrews, 2013a; D. Miller & Shamsie, 2001), which in

turn can negatively impact an organization’s financial performance (Luo et al., 2013b).

In summary, shorter tenure is associated with transformative behaviors that

promote change, innovation, alignment with patient needs, patient centered practices,

trust, increased employee morale, positive behaviors, collaboration, progress, risk taking,

teamwork, effective communications, and others that will potentially promote better

patient experience . Therefore, it was hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 3: Hospitals led by CEO with shorter tenure will be associated with

higher patient experience scores compared to hospitals led by longer tenured CEOs.

CEO Gender (Female vs. Male CEOs)

Women have been underrepresented in the highest levels of the healthcare

industry’s leadership. According to the American College of Healthcare Executives

(ACHE), most women are not reaching CEO positions because the healthcare industry

that has been traditionally shaped around male power and authority (Amanatullah &

Tinsley, 2013; Brescoll & Uhlmann, 2008; Engen & Willemsen, 2004; Isaac, 2011;

Lantz, 2008). Consequently, there is relatively limited literature regarding gender

attributes related to performance, with only a few studies looking at female CEO roles,

attitudes toward change, leadership styles, and other attributes (Anderson, Mclaughlin,

& Smith, 2007; Krishnan & Park, 2005; Musteen, Barker, & Baeten, 2006).

Furthermore, no research to date has examined the effects of CEO gender on patient

experience.

22

Women have been described as transformational leaders ( Eagly, Johannese, &

Engen, 2003), with some researchers arguing that females have better aptitude to

integrate and align organizational goals with the external environments (Prinsloo &

Barrett, 2013). Likewise, some researchers have suggested that female leaders approach

leadership differently than male CEOs and place greater emphasis on behaviors and

skills such as flexibility, intuition, and tactfulness when addressing challenging

circumstances, greater willingness to acknowledge mistakes, greater engagement in trust

building, problem solving, continuous quality improvement, collaboration, transparency,

compassion, innovation, and positive attitude toward change compared to their male

counterparts (Appelbaum, Audet, & Miller, 2003; Kark, Waismel-Manor, & Shamir,

2012; KLCM, 2014; Maniero, 1994; Paton & Dempster, 2002; Paustian-Underdahl,

Walker, & Woehr, 2014).

Females also exhibit greater levels of service orientation by placing greater

emphasis on perceptions of patient expectations for the service quality (O'Connor,

Trinh, & Shewchuk, 2000). The current researcher argued that these different emphases

would be associated with more patient centered cultures that support positive patient

experience. Thus, it was hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 4: Hospitals led by female CEOs are more likely to report higher

patient experience scores than hospitals led by male CEOs.

23

Chapter 3

Methodology

This chapter describes the research design, data sources, data collection, variable

operationalization, and analytic strategy.

Research Design

A cross-sectional, quantitative study was used to examine whether CEO

characteristics were associated with reported patient experience scores of CA hospitals.

Study Population

The hospital was the unit of analysis. The sample consisted of 294 California

(CA) hospitals. The decision to focus on CA hospitals was based on a combination of

pragmatic and research design considerations. The study’s use of primary data collection

for some variables, as well as limited data availability across states presented challenges

to including hospitals from multiple states. Therefore, CA hospitals were selected

because they operate across a diverse range of markets. Furthermore, the large number of

hospitals operating in CA provided a larger sample size, and thus greater power, to

examine the relationship between CEO characteristics and patient experience. The study

examined these relationships for calendar years 2013 and 2014.

Data Sources

Data for the analysis were aggregated from several sources: (1) The 2013 and

2014 American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Surveys; (2) The California Hospital

Association (CHA) 2013 and 2014 membership directories of hospital CEOs; (3)

24

Individual hospital websites; (4) LinkedIn; (5) Medicare Hospital Compare website; (6)

The census bureau market characteristics data; and (7) Becker’s Hospital Review.

Medicare Hospital Compare website is a public data source. The reported data are

updated each performance period (quarter) and each calendar year in January. This study

used 2013 and 2014 patient experience data available as of January 2015.

Select hospital characteristics from the AHA Annual Survey data can be accessed

via AHA Data Viewer at www.ahadataviewer.com. The most recent data were published

in November 2014 and reflect 2013 survey results regarding organizational structure,

system affiliation, facility and services lines, beds and utilization, staffing, and expenses

(www.ahadataviewer.com, 2014).

The CHA Membership Directory is updated and published in January of each year

to represent the most current CEO information. For example, the 2014 directory

represents CEO information as of December 2013.

Market characteristics were collected primarily from the Census Bureau

(www.census.gov), which reflects data from 2009 to 2013. Most studies dealing with

market characteristics have used the census.gov data because of its small margin of error

(Appendix G).

The study used January 2015 LinkedIn hospital CEO data. LinkedIn is a

professional networking website used by various professionals and executives. LinkedIn

uses the Advanced Intrusion Detection Environment (AIDE), a directory data integrity

checker, to accurately convert written records into usable data through data entry, data

conversion, information harvesting from the web, reporting, analysis, storage, and

database backup services (LinkedIn, 2015).

25

The 2015 Becker’s Hospital Review CEO data were also used in this study.

Becker's Hospital Review provides hospital and leadership information and is geared

toward high-level hospital leaders (CEOs, CFOs, COOs, CMOs, CIOs, etc.). Its data are

intended for approximately 18,500 healthcare executives and is published monthly.

The most recent information published on individual hospital websites was used

to gather CEO data. Most hospitals update their website’s content on a regular basis,

especially related to CEO changes and characteristics. Consequently, the 2015 January

data were used.

Measures

Dependent Variable

The patient experience score is a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 100 and

was obtained from the 2013 and 2014 Medicare hospital compare website. Patient

experience scores were calculated by CMS from Hospital Consumer Assessment of

Healthcare Provider and System (HCAHPS) surveys completed by hospitals (CMS,

March 2011). First, CMS calculates the unweighted patient experience of care domain

score for each hospital by summing the hospital’s HCAHPS base score (0-80) and

HCAHPS consistency score (0-20). Next, CMS calculates the weighted patient

experience of care domain score for each hospital by multiplying the unweighted patient

experience of care domain score by 0.30 (CMS, 2013). CMS publicly reports the

weighted scores from four consecutive quarters annually on the Medicare Hospital

Compare website (Medicare, 2014).

Data from the website include the following information: six digit numeric

hospital provider number, hospital name, hospital physical address, Zip Code, County,

unweighted and weighted patient experience score, ranging from 0 to 100, where ‘0’ is

26

the lowest score possible and ‘100’ is the highest score (Appendix B). The patient

experience data were then entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

Independent Variables

CEO characteristics were derived from primary and secondary data sources.

Secondary data sources were used to verify the accuracy of the primary sources.

The primary source was the 2013 and 2014 CHA Membership Directories. These

directories include the CEO name, contact information, education, and gender (Appendix

C). The secondary source was hospital websites, which have information regarding their

CEOs’ education/degree, tenure, and other information. Appendix D includes an example

of a hospital’s website of pertinent information. In situations where the CHA directory

and the hospital website provided inconsistent information, LinkedIn was used as a

tertiary source to adjudicate discrepancies. Appendix E includes a screenshot of a CEO’s

LinkedIn profile.

For example, if the CHA directory reported CEO gender but did not include

information regarding his/her education, the hospital’s website was consulted to confirm

the gender and determine education. Assuming the hospital website confirmed CEO

gender and provided an initial assessment of education, his/her LinkedIn profile (where

available) was consulted to confirm education. Finally, in the event these three sources

did not provide the necessary information or provided contradictory information

regarding CEO characteristics, Becker’s Hospital Review was consulted.

Gender. Each CEO has her/his name and his/her photo displayed next to the

hospital information in the CHA director. Gender was inferred based on the CEO’s name

and published photo. In situations where the name was ambiguous and the CEO photo

was missing in the directory, the hospital website was used as secondary resource.

27

LinkedIn CEO profiles were used as a cross-reference when the primary and secondary

sources were not clear and/or consistent. CEO gender was coded dichotomously as

female (1) and male (0).

Tenure. CEO tenure was a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 50 years,

representing time at his/her current position as the hospital’s CEO. Given the study’s

interest in CEO tenure, this variable was limited to years as CEO. For example, if he/she

worked for the hospital for 20 years, but only three years as its CEO, this study

considered tenure as three years. The primary source for CEO tenure was the hospital

website. Typically, each hospital website has a page devoted to its leadership team where

there is a short CEO biography, including how long the current CEO has been employed

as the CEO. Secondary sources for tenure were LinkedIn and Becker’s Review.

To calculate CEO 2014 tenure, the researcher accessed CHA membership

directory published in January 2015, which reflects CEO 2014 hospital employment data.

Then, CEO appointment year was subtracted from year 2014 to get the tenure data for the

study. For example, if the CEO was appointed in 2010, the tenure was subtracted from

year 2014 and was entered as four years (2014-2010).This calculation was repeated in the

same manner for 2013 CEO tenure data; the researcher accessed the membership

directory published in January 2014, which reflects CEO employment for year 2013. If

CEO was appointed in 2010, the tenure was subtracted from year 2013 and entered as

three years (2013-2010).

An identical method was used to calculate tenure by using LinkedIn data; the

researcher accessed each CEO’s LinkedIn biography published as of January 2015, and

looked for his/her hospital appointment history. To collect 2014 tenure data, the

researcher subtracted the CEO appointment year from 2014, and to get 2013 tenure data

28

subtracted the appointment year from 2013. The study set a threshold for tenure at six

months; therefore, tenure below six months was excluded from data analysis.

Education. The CHA directory page lists the hospital CEO’s name and

education/degree. Terminal degree education was coded as 1 for hospitals with a CEO

with a doctoral degree (Appendix H) and 0 for all other hospitals. CEOs with all other

degrees were coded under Non-Terminal degree as (0).

Clinical Terminal vs. Non-Clinical Terminal Degree was the second educational

variable that was used to assess the relationship between education and patient experience

scores. Clinical Terminal category meant a doctoral degree/education related to patient

care services. It was categorized as Clinical Terminal (1) and Non-Clinical Terminal as

(0), (Appendix I).

Control Variables

Research, in general, has found that hospitals’ response to regulatory changes

such as the ACA vary as a function of a number of organizational characteristics such as

ownership type, teaching affiliation, system affiliation, size, geographical location, payer

composition, and others (Cook, Shortell, Conrad, & Morrisey, 1983; Kaufman, 2013).

Therefore, the study controlled for several hospital and market level factors that could

have potentially impacted the patient experience reported score.

Hospital characteristics. Hospital characteristic variables were drawn from the

AHA Annual Survey data.

Location. Every 10 years, OMB reviews and revises the criteria to define

metropolitan areas (McDermott & Emery, 2015). For the 2010 Census, to qualify as an

urban area, the territory must encompass at least 2,500 people, 1,500 of whom reside

outside institutional group quarters. According to research, urban hospitals have better

29

access to human and financial resources, and can offer more comprehensive services

compared to rural hospitals (Yeager et al., 2014). However, other studies suggest that

rural hospitals, especially the smaller rural hospitals, demonstrate better patient

experiences (A. M. Epstein et al., 2005; Lehrman et al., 2010). Therefore, hospitals were

coded as a dummy variable (urban=1 and rural=0). In this case, a rural hospital was

defined as any hospital that was located in a county/area with less than 2,500 people

while an urban hospital was defined as any hospital located in a county/area with more

than 2,500 people.

Ownership type. Patient experience scores vary across different types of hospital

ownership. Specifically, patient experience scores are higher in for-profit hospitals and

lower in non-profit hospitals (Lehrman et al., 2010; Siddiqui, 2014). Public non-profit

hospitals, for example, exhibit poorer patient experience outcomes mainly due to their

weak pain management practice compared to other ownership types (Gupta, Lee, Mojica,

Nairizi, & George, 2014). The ownership type was a dummy variable with (0)

representing the non-profit hospitals and (1) representing for-profit hospitals.

Teaching affiliation: For the purpose of this study, teaching hospitals were those

closely associated with medical schools, served as a practical education site for medical

students, interns, residents, fellows and other allied health personnel. Findings regarding

the relationship between teaching status and patient experience are mixed. One study

suggested that teaching hospitals were more likely to display superior performance in

patient experience scores relative to non-teaching hospitals (Lehrman et al., 2010). A

more recent study, however, revealed that teaching hospitals demonstrated lower patient

experience scores due to their bigger size, more complex structures, shortage of nursing

and other clinical staff, poor patient access, and employee burnout (Carvajal, 2014).

30

Teaching affiliation was coded as a dummy variable with (1) for teaching and (0) for

non-teaching hospitals.

Size. Larger hospitals are typically busier places with higher error rates related to

longer work hours and staff burnout (Rogers, Hwang, Scott, Aiken, & Dinges, 2004).

Larger hospitals have a higher percentage of patients with poor experience because of the

longer laboratory/radiology turnaround times and provider delays (Handel, French,

Nichol, Momberger, & Fu, 2014; Samina, Qadri, Tabish, Samiya, & Riyaz, 2008).

Likewise, Lehrman et al. (2010) found that the top performers on patient experience were

smaller hospitals (100 beds or fewer). Hospital size was controlled for with a continuous

variable measured as the number of beds in the facility.

Market characteristics. Research suggests that market and patient characteristics

may also influence patient experience as it is based on each individual patient’s care

expectation, culture, age, health status, insurance type, income, family size, age,

education, language, race, length of stay, admission mode, and other characteristics

(Boscardin & Gonzales, 2013; Deshpande & Deshpande, 2014; Ruigrok, Greve, &

Nielsen, 2007; Sjetne, Veenstra, & Stavem, 2007). Market level control variables were

drawn from the AHA annual survey and CA Census Bureau data.

Competition. The Herfindahl Index was used to compute market level

concentration based on the sum of county beds. The Herfindahl index, as a measure of

competition, ranges from 0 to 1. Values close to 1 show highly monopolistic markets

with no competition while values close to 0 indicate highly competitive markets.

To calculate the Herfindahl Index, each hospital’s bed count was divided by the

total number of beds in a county, yielding the percentage of the beds in the market owned

by each hospital. This value was then squared for each hospital and summed across all

31

hospitals in a county. For example, assume a county has two hospitals (A and B) with 50

beds each. For hospitals A and B, their respective bed counts (50) were divided by the

total number of beds in the county (100), and then squared, yielding a value of 0.25 for

each hospital The sum of these two values is 0.50 (0.25 + 0.25), which is the Herfindahl

Index for that county.

Socio-demographic characteristics. Variables were constructed from CA census

data (www.census.gov) (Appendix F). First, the researcher used the AHA databases to

identify the county where the hospital was physically located. Then, the researcher

searched the census.gov webpage by entering the county in order to get the required

socio-demographic information.

All socio-demographic characteristics were calculated by first finding the number

of residents of the specific socio-demographic group within the county of interest, and

then dividing by the total population of the county, multiplied by 100. Thus, these

variables were continuous variables ranging from 0 to 100%.

Race. Race was measured as percent White and minority. Researchers typically

consider Blacks, Asians, and Hispanics as minority groups and Whites (non-Hispanic)

as the majority group. Percent White was constructed as the total number of White (non-

Hispanic) residents in a county divided by the total number of county residents,

multiplied by 100. Percent minority was calculated in a similar manner, as the sum of

Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians in a county, divided by the total number of county

residents, multiplied by 100.

Poverty level. Poverty level was defined as the percentage of persons below the

federal poverty level (Appendix G).

32

Age. Age was defined as the percentage of the population that is 65 years and

over. This age group was selected since patient experience was mainly reported for

Medicare patients.

Merging Data

Microsoft Excel was used to collect and merge data sets. Initially, the Hospital

Compare patient experience data were downloaded, which contained the hospital name,

address, and related patient experience score. Then, the CEO data were manually

collected and entered into Microsoft Excel. Hospital characteristic data from the AHA

Annual Survey were then merged with the rest of the data using the hospital name.

Finally, market characteristics were merged with these data using the county name. The

merged data set was finally transferred into SPSS to conduct the proposed data analysis.

33

Table 2

Study Variables, Measures, and Data Sources

Dep. Variable

Measure(s)

Data Source (s)

CA Hospitals’ 2013,

2014 Patient

Experience Scores

Scores ranging

from

0 -100. 0 is the

lowest score and

100 is the highest

score

Medicare Hospital Compare 2013, 2014

Data

(http://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare)

Ind. Variable

Measure(s)

Data Source (s)

CEO Gender

Female (1)/Male

(0)

Primary: CHA 2013, 2014 Member

Directories

Secondary: Hospital Website

Tertiary: LinkedIn

CEO Tenure

Years as CEO in

the current position

from 0 -50 years

Primary: Hospital Website

Secondary: LinkedIn

Tertiary: Becker's Hospital Review

CEO

Education/Degree

Clinical Terminal

Degree (1) /Non-

Clinical Terminal

Degree (0)

Terminal (1)/Non-

Terminal (0)

Primary: CHA 2013, 2014 Member

Directories

Secondary: Hospital Website

Tertiary: LinkedIn

Cont. Variable

Measure(s)

Data Source (s)

Hospital Ownership

Type

For-Profit (1)/Non-

Profit (0)

AHA 2013, 2014 Databases

Hospital Location

Urban (1)/Rural (0)

AHA 2013, 2014 Databases

Hospital Size

Number of Beds as

a continuous

measure

AHA 2013, 2014 Databases

Hospital Teaching

Affiliation

Teaching(1), Non-

Teaching (0)

AHA 2013, 2014 Databases

Market Competition

Herfindahl Index (0

to 1)

AHA 2013, 2014 Databases

Race/Ethnicity

Percent White and

Minorities, 0-100%

of the total

population

U.S. Census Bureau

www.census.gov

Poverty Level

Percent population,

0-100%

U.S. Census Bureau

Age as 65+

Percent population,

0-100%

U.S. Census Bureau

34

Statistical Analysis

Regression analysis was used to analyze the relationships between CEO

characteristics and patient experience. Two sets of ordinary least square regressions were

used, one for each of the educational variables chosen (i.e., one model with terminal

degree as a predictor, and another with Clinical/Non-Clinical terminal degree as a

predictor). The two sets of regression models were necessary to address likely

multicollinearity between the two education variables.

The analysis included the following steps:

a. Investigated the data set via descriptive statistics to identify missing values,

departures from normality, presence of outliers and/or influential

observations, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity among the predictors.

b. Residual analysis. Each model was rigorously tested for goodness of fit

against functional misspecifications, heteroscedasticity, and possible

multicollinearity issues using a combination of analytical tools based on the

residual terms of the regressions, including graphical methods and formal

statistical tests.

Graphical methods included:

Plot residuals vs. predicted patient experience scores. A random

scatter plot with no outliers or influential observations and with

constant variance indicated whether there was any departure from

the conditions under which a linear regression model is known to

work well. If that is not the case, scatter plots of residuals vs. each

of the other covariates were used to detect whether any of the

predictors were responsible.

35

Checked for normality using the Q-Q plot (after having solved the

other issues listed above).

Formal statistical tests included:

Breusch-Pagan test for homoscedasticity

Detected misspecifications and the need to transform variables by

regressing the estimated residuals against the predictors and their

squares to detect the need for more complex functional forms other

than the linear one. If all coefficients were not statistically

significant, then the model was to be correctly specified; add extra

predictor(s) or transformation of the dependent variable.

36

Chapter 4

Analysis and Presentation of Findings

This chapter presents the results of the data analysis used to investigate the

relationship between selected CEO characteristics and patient experience scores. The four

hypotheses tested in this study were:

Hypothesis 1: Hospitals led by CEOs that hold terminal degrees will be associated with

higher patient experience scores compared to those hospitals led by CEOs with non-

terminal degrees.

Hypothesis 2: Hospitals led by CEOs that hold a clinical terminal degree will be

associated with higher patient experience scores compared to hospitals led by CEOs that

do not hold a clinical terminal degree CEOs.

Hypothesis 3: Hospitals led by CEOs with shorter tenure will be associated with higher

patient experience scores compared to hospitals led by longer tenured CEOs.

Hypothesis 4: Hospitals led by female CEOs will be associated with higher patient