November 2015

By Caitlin omas-Henkel, Taylor Hendricks and Kelly Church, Center for Health Care Strategies

Opportunities to Improve Models

of Care for People with Complex

Needs: Literature Review

SUPPORTING A CULTURE OF HEALTH FOR HIGH-NEED, HIGH-COST POPULATIONS:

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction ................................................. 3

Methods ..................................................... 4

Literature Search ........................................ 4

Limitations ............................................... 4

Summary of Findings ...................................... 6

Care Model Enhancements ............................ 6

Opportunities for Further Exploration .............. 8

Financing and Accountability .......................... 8

Opportunities for Further Exploration .............. 9

Data and Analytics ...................................... 10

Opportunities for Further Exploration .............. 11

Workforce Development ................................ 12

Opportunities for Further Exploration .............. 13

Policy and Advocacy ................................... 13

Opportunities for Further Exploration .............. 14

Conclusion .................................................. 15

Appendices: Index of Literature ......................... 16

Appendix A: Care Model Enhancements ............. 16

Appendix B: Financing and Accountability ........... 22

Appendix C: Data and Analytics ....................... 26

Appendix D: Workforce Development ................. 32

Appendix E: Policy and Advocacy .................... 36

C. Thomas-Henkel, T. Hendricks, and K. Church. Opportunities to Improve Models of Care for People

with Complex Needs: Literature Review. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Center for

Health Care Strategies, November 2015.

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

3

INTRODUCTION

I

ndividuals with high rates of avoidable hospital admissions or emergency department (ED) visits—

sometimes called “high-need, high-cost patients” or “super-utilizers”—tend to have multiple medical,

behavioral health and social needs, resulting in high costs and, typically, poor outcomes. These

individuals often have an array of complex social challenges—potentially including unemployment,

homelessness, substance use disorders, and food insecurity—which must be addressed in order to

sustainably improve health outcomes and reduce their health care utilization.

With support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and in line with the Foundation’s vision for

building a Culture of Health for all Americans,

1

the Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) conducted

a literature review to explore the evidence base regarding effective approaches to care for high-need,

high-cost populations. CHCS organized its analysis of relevant materials around five key domains:

The literature review was designed to identify: (1) effective strategies for improving outcomes and lowering

costs for high-need, high-cost populations; and (2) critical gaps that must be addressed to better integrate

health and social services and produce desired outcomes for this population. This synthesis highlights

key findings and gaps in information gleaned from the literature review. See also a companion report that

synthesizes key findings from a related environmental scan and small group consultation.*

* The companion report, Opportunities to Improve Models of Care for High-Need, High-Cost Populations, includes a

sixth domain, governance and operations, that was identified subsequent to the completion of the literature review.

Care Model

Enhancements

Workforce

Development

Financing &

Accountability

Data &

Analytics

Policy &

Advocacy

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

4

METHODS

LITERATURE SEARCH

T

he review included studies conducted in the United States and published since 2005, as

identified through MEDLINE (using the PubMed interface), Cochrane Library, National Guideline

Clearinghouse, and Google Scholar. We included people with serious mental illness (SMI),

since this population often has a high rate of physical comorbidities, as well as high associated health

care costs.

2

The literature search also used Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms by the National

Library of Medicine, whenever a term was available.

3

For example, searches included keywords such

as comorbidity, severe mental illness, delivery of health care, integrated, cost savings, and/or patient

readmission. In addition to the primary search term, the literature review used secondary search terms

to filter findings that corresponded with the five domains and keyword terms such as: integrated +

care + management, financial + alignment + accountability, data + analytics, workforce + strategies,

and policy + advocacy.

Two reviewers scanned the abstracts of articles identified from the database searches to assess relevance

to the search criteria. Discrepancies in inclusion were resolved by discussion and re-review with additional

project team members. The search also included non-peer reviewed studies and relevant tools and

resources. To search for these secondary sources or “gray material” on the key topics, CHCS relied on

the same search terms employed in the peer reviewed material, including the following sources: California

HealthCare Foundation; Center for Health Care Strategies; The Commonwealth Fund; Health Affairs (for

non-peer-reviewed resources in addition to those found through the search described above); Institute for

Healthcare Improvement; National Governor’s Association; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; and other

reputable health care organizations.

LIMITATIONS

There is an expansive body of literature that arguably could have bearing on efforts to improve care

and outcomes for high-need, high-cost populations. For example, strategies to improve outcomes for

individuals with SMI are generally relevant to “super-utilizer” programs given the prevalence of SMI among

this population. However, a synthesis of the literature around behavioral health treatment modalities for

SMI would be a project unto itself. Thus, CHCS limited its review to studies with greatest direct relevance

to the goals of this analysis—namely, to inform further development and enhancement of complex care

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

5

management programs serving high-need, high-cost populations. In the case of the SMI literature, this

resulted in the exclusion of studies on modalities specific to treating psychiatric illness (such as cognitive

behavioral therapy).

Across a few domains, the literature review was constrained by the relative nascence of this field of

study. For example, many programs for super-utilizers are in the early stages of development and

implementation, and have not yet tackled issues related to financing and accountability. Many programs

lack robust data collection and analysis mechanisms, making evidence on best practices difficult to

discern. Further, few randomized trials on interventions for high-need, high-cost populations exist,

highlighting the need for more robust evaluations of these programs.

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

6

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

CARE MODEL ENHANCEMENTS

B

ecause traditional models of care delivery are typically not effective for individuals with complex

medical, behavioral health, and social needs, enhancements to these models attempt to improve

outcomes and decrease costs by increasing connectivity between providers, tailoring clinical

interventions, coordinating care, integrating disparate systems, and addressing the social determinants

of health.

As reflected in the literature, effective models of care for super-utilizers rely on an intensive care

management approach. For example, a randomized controlled trial of an intensive care management

program that coordinated medical and mental health services for high-risk Medicaid beneficiaries in

Washington State showed increased access to care, lower inpatient medical costs, fewer unplanned

inpatient admissions, lower likelihood of experiencing homelessness, and fewer deaths.

4

A more

recent analysis of a separate Washington State care management program serving high-risk Medicaid

beneficiaries with disabilities revealed significant decreases in inpatient hospital costs for individuals in

the program, as well as non-significant decreases in total medical costs.

5

Reduced ED use and hospital

charges were also observed in various models of intensive care management for frequent ED users.

6–7

Core components of intensive care management programs that demonstrate positive outcomes for

high-need, high-cost patients include: extensive outreach and engagement; initial assessment; goal-

setting and care plan development; health education/coaching; frequent care team contact; follow-up with

patients after discharge; and linkages to housing, substance use disorder services, and other community

resources.

8–11

Several programs incorporate home visiting and round-the clock telephonic access to care

managers.

12–13

Programs that provide face-to-face care management directly with patients have more

evidence of effectiveness than those that employ telephonic care management services.

14–17

Medication

management, pain management, and support for care transitions (e.g., from hospital to community

settings) are also highlighted as integral aspects of achieving positive outcomes in care management

programs for high-need, high-cost patients.

18–21

Another resource defined super-utilizer programs as “data-

driven, high-intensity, community-based, patient-centered models using interdisciplinary teams to deliver

high-quality, comprehensive care, while encouraging self-advocacy and personal accountability.”

22

Effective targeting of services to high-risk patients is critical. For example, the Medicare Chronic Care

Demonstrations revealed a higher likelihood of reducing hospitalizations among beneficiaries at high risk

of hospitalizations than among a general population with chronic conditions.

23

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

7

Care team composition varies among effective programs, but often includes a primary care provider,

nurse, social worker, behavioral health specialist, and community outreach staff (e.g., community health

workers).

24–26

Care managers may be located on site at a provider practice or hospital; at a centrally

located care management agency, providing care management to multiple practices; or at a clinic where

an “intensivist”—a physician specializing in the treatment of patients in intensive care—is assigned a

high-risk patient panel.

27

An abundance of research demonstrates the importance of physical and behavioral health integration in

providing comprehensive health care.

28

Coordination of physical and behavioral health services—through

information exchange, joint care planning, or integration into primary care—is often cited as a key aspect

of complex care management, especially for individuals with serious mental illness.

29–32

Pilot programs in

Pennsylvania that integrated physical and behavioral health services and provided care management

for high-need, high-cost Medicaid beneficiaries resulted in lower mental health-related hospitalizations,

lower all-cause readmission rates, and fewer ED visits.

33

However, not all approaches to integration are

equally effective for high-risk individuals. For example, fully integrated physical and behavioral health

care, coupled with care management for individuals with SMI and substance use disorder, has been

shown to improve physical and mental health symptoms, as well as overall quality of life.

34

However,

simply co-locating primary care providers in substance use disorder treatment facilities without providing

care coordination services does not necessarily improve health outcomes for these individuals.

35

Clinical interventions that incorporate trauma-informed approaches to care for high-need, high-cost

patients may improve patient engagement and enhance quality and cost outcomes for these populations.

36

Qualitative research with complex patients who have high levels of ED and hospital use highlight a

number of psychosocial factors and life experiences that impact their care needs, including: (1) early-life

instability and traumas; (2) a history of difficult interactions with health care providers during adulthood;

and (3) the importance of positive and “caring” relationships with primary health care providers and the

outreach team.

37

Patient activation—or having the knowledge, skills, and confidence to manage one’s health—is recognized

as an important factor in the effectiveness of interventions for individuals with complex needs, and also

as a potential benefit of these interventions. For instance, the use of peer support providers for individuals

with mental illness has shown evidence of increased patient activation.

38–39

Higher patient activation is

linked to better health outcomes in the short- and long-term.

40–41

Acknowledging the critical role of social determinants of health, some intensive care management

programs for high-utilizing populations use nontraditional health care workers (e.g., community health

workers, peers, etc.) to connect individuals to needed social services and supports.

42

As recognition

of the impact of social factors on health outcomes continues to grow, efforts to address housing

instability, in particular, have gained traction as a method for improving outcomes and reducing costs

for high-need individuals.

43–44

Housing First interventions—in which high-utilizing patients are provided

with stable housing without a medical care component

45

—have been linked to reduced ED visits; fewer

hospital admissions; fewer hospital and nursing home days; reduced inpatient costs; and reduced

Medicaid expenditures.

46–49

States and communities across the country are increasingly implementing

housing interventions for high-risk populations, as these programs prove less costly and more effective

than managing homelessness and health problems on the street or in a shelter.

50–53

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

8

Opportunities for Further Exploration

The evidence around effective care models for high-need, high-cost patients is still emerging, with

relatively few high-quality studies revealing significant impacts on costs and utilization. Whereas efforts

over the last decade have clarified some core program elements as described above, key gaps in

understanding remain. For example, given the variation in approach across published studies, there

is limited ability to assess the replicability or generalizability of specific findings. Similarly, the lack of

rigorously tested high-quality models likely creates a significant amount of undocumented variation

in approach across participating providers or care team members even within a given study. Future

studies should seek to standardize models of care—including clearly defined interventions, frequencies

and modes of contact, and follow-up periods—and test their effectiveness across multiple sites.

Outside of a general finding that programs are most effective when targeted to high-risk patients, the

literature is not yet convincing on the most effective way to identify or calculate high risk. For example,

some successful programs rely on predictive modeling, while others specifically target individuals with high

rates of recent ED visits or inpatient admissions.

54–55

This highlights the need for greater understanding

about how to best target care coordination interventions to individuals for maximum impact.

Effective engagement strategies are another opportunity for future exploration, particularly given the

low engagement rates observed across published studies.

56–57

As the transient and vulnerable nature of

this population presents challenges for engagement and follow-up, additional qualitative and quantitative

studies should be designed to understand why some individuals do not engage in care management when

offered as well as strategies for promoting higher engagement rates.

58–59

Finally, further research to distill the discrete impact of housing interventions may be needed. In one

instance, high-utilizing patients were provided with ongoing case management in addition to housing

support, and researchers were unable to distinguish the impact of the housing support from that of the

care management services provided.

60

FINANCING AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Given the evidence indicating that integration of medical and behavioral health care—and more recently,

social services—may improve care and cost outcomes for certain high-need populations, a number

of states and communities are testing financial alignment and accountability models that support this

integration. The literature revealed a number of promising approaches to the alignment of financial

incentives and outcomes that are emerging across the U.S.—particularly in the form of pooled or braided

health and social service funding; global and bundled payments; and shared-risk models like Accountable

Care Organizations (ACOs).

States are increasingly exploring administrative, purchasing, and regulatory strategies to better integrate

physical and behavioral health care for high-need, high-cost Medicaid populations.

61

Some states are:

(1) consolidating the agencies responsible for overseeing physical and mental health and substance use

disorder services; (2) combining responsibility for behavioral health purchasing, contracting, and rate-setting

in the Medicaid agency and maintaining licensing and clinical policy authority in the behavioral health agency;

or (3) establishing informal collaborations to rationalize strategies across agencies.

62

Purchasing strategies

used by states include policies that create linkages across providers and systems (especially in managed

care “carve-out” environments) and implementation of fully integrated managed care approaches (e.g., for

individuals with SMI).

63

State Medicaid contracts with managed care organizations are one mechanism for

aligning incentives across physical and behavioral health systems.

64

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

9

Though models for integrating health and social services are still in the fledgling stages, small-scale

efforts have shown promise in improving care and cost outcomes, and states are exploring financing options

to build on this success.

65–67

Medicaid ACOs across the country are taking preliminary steps to provide

non-clinical supports to high-need, high-cost patients, leveraging financial incentives for providers to use

social services to maximize the impact of care interventions.

68

Programs in Colorado, Minnesota, New York,

Washington, Vermont, and other states are at varying levels of laying the groundwork for social service

integration into their Medicaid ACOs.

69

Community-based ACOs—or “accountable health communities”—

represent another innovative model, serving a coordinating function and taking accountability for providing

and paying for an array of services outside of traditional medical care payments.

70

Shared savings or

capitated payment structures may encourage closer collaboration between the health care and social service

systems. Current state approaches include, at one end of the continuum, grants to support provider capacity

building, and at the other, integrated payment models connecting providers and social services.

71

Future

studies are needed to evaluate whether these financing approaches contribute to the end goals of better

health and lower costs.

Hennepin Health, an ACO in Minnesota, has developed a model that integrates physical, behavioral

health, and social services (e.g., housing) for high-need, high-cost Medicaid beneficiaries using aligned

financial incentives.

72

It operates under a braided financing strategy, receiving a fixed per member per

month (PMPM) payment for the total cost of Medicaid health services (excluding long-term care) and using

grants from the county to cover the cost of some program staff.

73

In the model, social services are paid

for with human service funds from pre-existing state and county sources, supplemented by the health

plan’s PMPM payments.

74

Hennepin Health’s preliminary results have shown a shift in care from the ED

and hospital to outpatient settings, and the percentage of patients receiving optimal diabetes, vascular,

and asthma care has increased. Hennepin Health has also achieved a high patient satisfaction rating, with

87 percent of members reporting that they are satisfied with their care.

75

A number of states including Ohio and Michigan have implemented the Pathways Community HUB

Model, which coordinates clinical and social services at the community level to reduce duplication

of services and create greater efficiency. The model has been shown to reduce costs and improve

outcomes in a high-risk pregnancy population.

76

Opportunities for Further Exploration

While promising approaches to financial alignment and accountability are emerging across the country, there

is a need for increased examination of their effectiveness in supporting programs for high-need, high-cost

populations. As many of these programs are in the early stages of development and implementation, they

do not yet have sustainable financing mechanisms, and so it is difficult to understand what components

of funding and payment structures are most feasible and effective. Additionally, the U.S. has been

cited as lacking in robust population health outcomes, which may be partially attributed to a lack of

comprehensive investment strategies to address non-clinical interventions.

77–78

There are varying levels of capacity among states, communities and providers to align physical,

behavioral health, and social services when dealing with a diverse set of systems and funders that work

primarily in isolation.

79–80

A complicating factor in developing comprehensive payment models is the

limited regulatory authority among state Medicaid agencies to pay for non-clinical services, especially in

fee-for-service (FFS) arrangements.

81

Despite increased flexibilities to reimburse for non-clinical services

under a value-based or PMPM reimbursement system, these services must often meet “medical

necessity” criteria under the state definition. In addition, alignment efforts must often show the capacity

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

10

to yield a return on investment to attract payer interest. This can create challenges as states look to

pursue more integrated care models that align multiple funding sources across payers and finance

alternative “non-clinical” services.

A previously published systematic review of interagency collaboration between local health and local

government agencies failed to produce any evidence that these partnerships, compared to standard care,

led to health improvements.

82

This highlights an opportunity to further explore how models that work

across public systems—such as Hennepin Health—can be most effective in serving high-need,

high-cost populations.

DATA AND ANALYTICS

High-quality data and analytics are highlighted in the literature as a critical component of effective

programs for high-need, high-cost populations.

83–88

Data are used to identify high-need, high-cost patients

for specific interventions and to predict which individuals could be prevented from becoming high-need,

high-cost users.

89–92

The literature also highlighted current efforts to use data to inform clinical and care

management approaches and identify ways to establish data linkages across providers in the health and

social service systems.

A number of articles and resources highlight the value of using predictive modeling and risk stratification

to identify patients at-risk for high ED use and target interventions appropriately.

93–98

One study found

that ‘no-show propensity’ is an independent predictor of poor primary care outcomes, and thus may help

health care systems identify patients at-risk for high utilization.

99

Another found that recent criminal justice

involvement was associated with higher hospital and ED utilization among individuals with substance

use disorder, with psychological disorders, or without insurance.

100

Older patients, Medicaid recipients,

individuals living further away from the point of care, and those with diabetes or depression were more

likely to be high-utilizers, according to a retrospective and longitudinal analysis of medical records from

an urban community health center.

101

In yet another analysis, individuals with substance use disorder who

had high-frequency ED, ambulatory, and inpatient medical care use were more likely to be female, African

American, homeless, or have a history of substance abuse treatment or ambulatory care visits.

102

An

algorithm developed at New York University to classify ED use into various categories—ranging from

non-emergent to unavoidable emergent—was used to analyze ED use in Rhode Island. It revealed that

over 20 percent of ED visits between 2008 and 2012 were non-emergent, and that non-emergent ED users

were more likely to be: between 20-39 years of age, Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, and female.

103–104

In addition to predicting risk, another aspect of patient identification highlighted in the literature

is predicting care sensitivity, or the likelihood that an individual will respond to a particular care

management intervention.

105

This may involve excluding patients whose needs are unlikely to be addressed

by available resources; identifying patients facing certain barriers or care gaps; identifying “windows of

opportunity,” such as care transitions; or identifying patients who have previously experienced difficulty

with care coordination.

106

As an example, care teams may exclude patients undergoing chemotherapy,

dialysis or radiation, because they feel that the care management services may be unlikely to yield positive

outcomes when compared to the specialty-based services already in place.

107

Much of the literature sought to identify characteristics and develop a profile of high-need, high-cost

populations. In 2009, five percent of Medicaid beneficiaries accounted for 54 percent of costs, and those

with disabilities accounted for 30 percent of Medicaid costs.

108

In one analysis, mental health and other

behavioral health conditions were the top diagnoses linked to hospital stays among super-utilizers, followed

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

11

by alcohol-related disorders.

109

Among high-expenditure Medicaid-only enrollees with both substance abuse

and a mental health condition in fiscal year 2011, nearly half had no physical health conditions

110

In another

analysis of inpatient high-utilizers, behavioral health conditions were disproportionate on their billing records

compared to inpatients who were not high utilizers of inpatient services (74.9% v. 32.3%).

111

An additional

study revealed heart failure, septicemia, and mental health disorders as the top three reasons for hospital

admission among super-utilizers.

112

A number of analyses of high-cost Medicaid beneficiaries revealed

patterns of multimorbidity related to higher utilization and expenditures.

113–116

Within the most expensive

one percent of beneficiaries in Medicaid acute care spending, nearly 83 percent had three or more chronic

conditions.

117

Mental illness is nearly universal among Medicaid’s highest-cost, most frequently hospitalized

beneficiaries, and the presence of mental illness or substance use disorder is associated with much higher

per capita costs and hospitalization rates.

118

An analysis of Pennsylvania’s super-utilizers—patients with five or more admissions to a general acute

care hospital in fiscal year 2014—revealed that this population accounted for 10 percent of Medicare

admissions, 18 percent of Medicaid admissions, 20 percent of Medicare-Medicaid admissions, and seven

percent of commercial payer hospital admissions. These statewide results highlight the importance and

collective responsibility for addressing the needs of this population across payers.

119

Opportunities for Further Exploration

Despite numerous efforts across the country to precisely predict who is likely to become a high-utilizer,

gaps remain in these methods—many of which rely heavily on past claims data to identify high-risk

patients.

120

In fact, many risk prediction models only account for a quarter to a third of the factors that lead

to individuals’ future expenditure, and typically do not perform well for high-need, high-cost patients.

121

Integration of data—particularly across health and social services systems—remains a challenge.

In order to gain an accurate understanding of which patients to target for which interventions, and to

comprehensively address their needs, it is important to see the full picture of health and social service

utilization. Some states and localities have started testing how to achieve cross-system data integration,

but these efforts are rare and in the infancy stages of development.

While the importance of data to identify and target interventions is not disputed, less clear is how data

can be used to measure quality among high-need, high-cost patient populations with multiple medical,

behavioral health, and social challenges.

Further, there is a paucity of rigorous evaluation (e.g., randomized controlled trials, longitudinal analyses)

among programs that target super-utilizers, which makes replication of effective programs problematic

and limits the policy argument for doing so. Several articles emphasized that it takes significant time to

demonstrate the impact of super-utilizer programs, as these individuals are difficult to engage; behaviors

are difficult to change and sustain; and often times, costs for utilization increase in the short term, as

traditionally disconnected individuals are finally linked with needed services.

122

Regression to the mean can

also create difficulties in demonstrating the effectiveness of interventions for high-need, high-cost patients,

due to their often erratic utilization patterns, incurring high costs one year and perhaps far lower costs the

next—even without intervention.

123

Evaluations of these programs should account for regression to the

mean and control for it when possible.

124

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

12

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

The review of literature related to workforce development primarily focused on using non-traditional

health workers—also referred to as lay health workers, community health workers, or peer support

providers—in care delivery for high-need, high-cost populations. Various articles and resources highlighted

programs using these non-traditional health workers, revealing a number of successes and challenges

related to these alternative workforce models. A few resources discussed how workforce training specific

to engaging with complex patients may improve patient/provider experience and patient outcomes, as

described further below.

While their non-traditional role in care delivery is sometimes criticized as ambiguous, the literature

described some common responsibilities for community health workers and peer support providers.

One article highlighted seven core roles for community health workers: providing cultural mediation;

delivering appropriate education; ensuring connections to needed services; offering informal counseling

and social support; advocating; providing direct services; and building capacity.

125

In a model developed

at the University of Pennsylvania, community health workers help patients create individualized action

plans around self-identified goals.

126

In addition, the literature underscored the unique role of community

health workers in addressing persistent health disparities and understanding and responding to the

many challenges faced by patients in navigating the health care system, obtaining necessary supportive

resources, and building self-efficacy and health literacy.

127

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) definition of a ‘peer’ is a

person who has lived experience of recovery from mental illness and/or addiction and who wishes to provide

peer support services to others who are living with these disorders.

128

Some of the literature described the

role of peer support providers on care teams as more ambiguous than that of community health workers.

129

The development of trusting relationships with patients, based on mutual experience, respect, and hope,

is highlighted as a key function of the peer support role.

130

Patient education; social and emotional support;

advocacy; assistance with daily tasks; and connection to medical, behavioral health, legal, and financial

services are also described as responsibilities of peer support providers.

131–133

Numerous studies show promising results based on lay health worker interventions. A randomized

clinical trial of a community health worker model in Philadelphia showed improvements in patient

experience and outcomes, and reductions in hospital readmissions.

134

In another randomized controlled

trial using lay health workers as care guides, patients were 31 percent more likely to meet evidence-

based goals and 21 percent more likely to quit tobacco use.

135

These patients had fewer hospitalizations

and ED visits and reported more positive perceptions of their care, including improved social support,

individualized care, and understanding of how to improve their health.

136

A program for Medicaid super-

utilizers in Oregon, led by a nurse and supported by two community health workers, decreased ED

utilization from 78 percent in 2011 to 59 percent in 2013.

137

Peer support services were broadly recognized in the literature as a promising approach. SAMHSA

suggests that recovery-oriented, peer-provided behavioral health services are supported by a growing

body of evidence showing improved outcomes—sometimes even superior to non-peer provided

services.

138

Similarly, several articles highlighted the potential for peer support services to improve care

and produce substantial cost savings.

139

An analysis of a peer-led program for individuals with serious

mental illness in New York showed promising results: at six-month follow-up, program participants had

a significantly greater improvement in patient activation and higher rates of primary care visits, as well

as improvements in quality of life, physical activity, and medication management.

140

Medically and socially

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

13

vulnerable members of the intervention population showed the greatest improvements in physical health

related quality of life.

141

One assessment of current research related to peer support services for individuals

with serious mental illness, found that when compared to professional staff, peers were better able to

reduce inpatient use and improve a range of recovery outcomes, but that the effectiveness of peers in

existing clinical roles was mixed.

142

The same assessment found a number of other promising outcomes

across several peer provider models, including, improved relationship with providers; better engagement

with care; higher levels of empowerment; and higher levels of hopefulness for recovery.

143

An examination

of peer specialist interventions for veterans with serious mental illness also showed positive outcomes

related to reduced inpatient use and increased patient engagement.

144

The review provided some insight into how workforce training can improve patient experience and

outcomes for complex patient populations. One article highlighted the importance of training providers

to understand and work within the context of complex patients’ lives—starting with conducting a

comprehensive assessment of their array of health and social needs.

145

Another resource, which described

techniques for providers to successfully engage with super-utilizers, centered around creating trusting

relationships. The methods ranged from physical mannerisms and behaviors—such as removing a doctor’s

coat and making eye contact, to engaging with the patient in a sensitive, respectful, and strengths-based

way—for instance, by requesting permission to ask questions or asking what the individual enjoys doing.

146

Opportunities for Further Exploration

The review revealed significant challenges related to workforce development. In addition to role ambiguity,

challenges cited around the use of peer providers included lack of clear expectations, training, and

skills.

147–149

Additionally, supervisors had difficulty providing supervision and evaluating peer provider

performance.

150–152

Low pay and lack of career advancement opportunities were also mentioned as

challenges in the development of a peer support workforce.

153–154

The literature called for more rigorous evaluation of programs that use non-traditional health workers,

in order to establish a more robust evidence base of their efficacy in producing improved care and

cost outcomes.

155–159

SAMHSA cited lack of an accepted typology as a key hindrance to research and

evaluation of peer support programs.

160

Further, programs that are targeted to high-cost or high-utilizing

populations are likely to experience regression to the mean (in which costs/utilization naturally normalize

toward the population average over time), which may call into question any evidence of savings.

161

While

some peer provider and community health worker interventions have shown promising outcomes, these

models are typically developed for specific chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes, serious mental illness),

leaving a gap in knowledge as to whether these programs work for individuals with more complex health

and social needs. And perhaps in part due to these gaps, sustainable funding for non-traditional workforce

models remains a challenge.

POLICY AND ADVOCACY

The literature on policy and advocacy related to high-need, high-cost populations provided a range of

recommendations to support improvements across the above-mentioned domains. Addressing health

system transformation more broadly, one resource suggested that super-utilizer programs—which are

rooted in data, clinical redesign, and stakeholder engagement—can serve as a model in transforming

the overall health care delivery system.

162

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

14

The need for payment reforms that account for the important role of care coordination and multidisciplinary

teams in caring for high-need, high-cost patients was widely cited as a critical policy reform.

163–164

Along

these lines, one article suggested that payment reform should move toward risk-adjusted per patient

payment, and include incentives for quality, services provided by non-clinicians on the care team,

and population-oriented panel management.

165

Other payment mechanisms highlighted include care

management fees, episodic payments, and shared savings contracts.

166

An informational bulletin from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) described several

Medicaid policy authorities for supporting super-utilizer programs, including: enhanced federal match

for the design, development, and implementation of Medicaid Management Information Systems;

enhanced federal match for health information exchanges; administrative contracts; Medicaid health

homes; integrated care models; targeted case management services; and Medicare data access

and assistance.

167

Policies that support improved access to high-quality, real-time, all-payer data were underscored

as crucial to the success of programs for high-need, high-cost populations.

168–169

Data can highlight the

discrepancy between health expenditures and outcomes, allowing for more precise resource allocation

and gradual movement toward a high-value health care system.

170

One article referenced the important role that public health strategies can play in mitigating risk factors

associated with chronic diseases, such as those that promote smoking cessation and consumption

of healthy foods.

171

The same article recommended developing policies to support expansion of an

interdisciplinary primary care workforce.

172

Opportunities for Further Exploration

Despite some clear policy opportunities related to financing and data, there remain gaps in understanding

which policies can best support improvements in care for individuals with complex medical, behavioral

health, and social needs. As states continue to test new delivery and payment models for high-need,

high-cost populations through health homes, ACOs, and other innovative approaches, policies that

support these efforts are likely to germinate.

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

15

CONCLUSION

T

his review of select literature related to high-need, high-cost populations illuminated key areas

of promise and remaining gaps in knowledge related to care model enhancements; financial

alignment and accountability; data and analytics; workforce development; and policy and

advocacy. Numerous opportunities exist to advance improvements care and cost outcomes by

addressing the gaps remaining in each of these domains.

Notably, there are a number of rigorous evaluations of intensive or complex care management programs

currently underway that promise to add to the collective understanding of what works to improve care

and reduce costs for high-need, high-cost patients. Many of these evaluations are related to programs

receiving funding through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s (CMMI) Health Care

Innovation Awards, with results expected to be published over the next several years. In addition

to site-specific evaluation efforts, a CMMI-funded evaluation further aims to synthesize key findings

across all of the award sites that share a common focus on high-need, high-cost patients.

While these efforts will undoubtedly improve the evidence base, additional multi-site studies—specifically,

ones that test the effectiveness of a clearly defined model of care across multiple study locations—will be

needed to advance the development of a high-fidelity approach that can be replicated broadly throughout

the U.S.

Finally, as the field of “complex care” continues to grow and expand, so will its corresponding evidence

base. Thus, a strategy of continuous quality improvement must be implemented to maintain a cutting-edge

understanding of this emerging field.

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

16

APPENDICES

INDEX OF LITERATURE

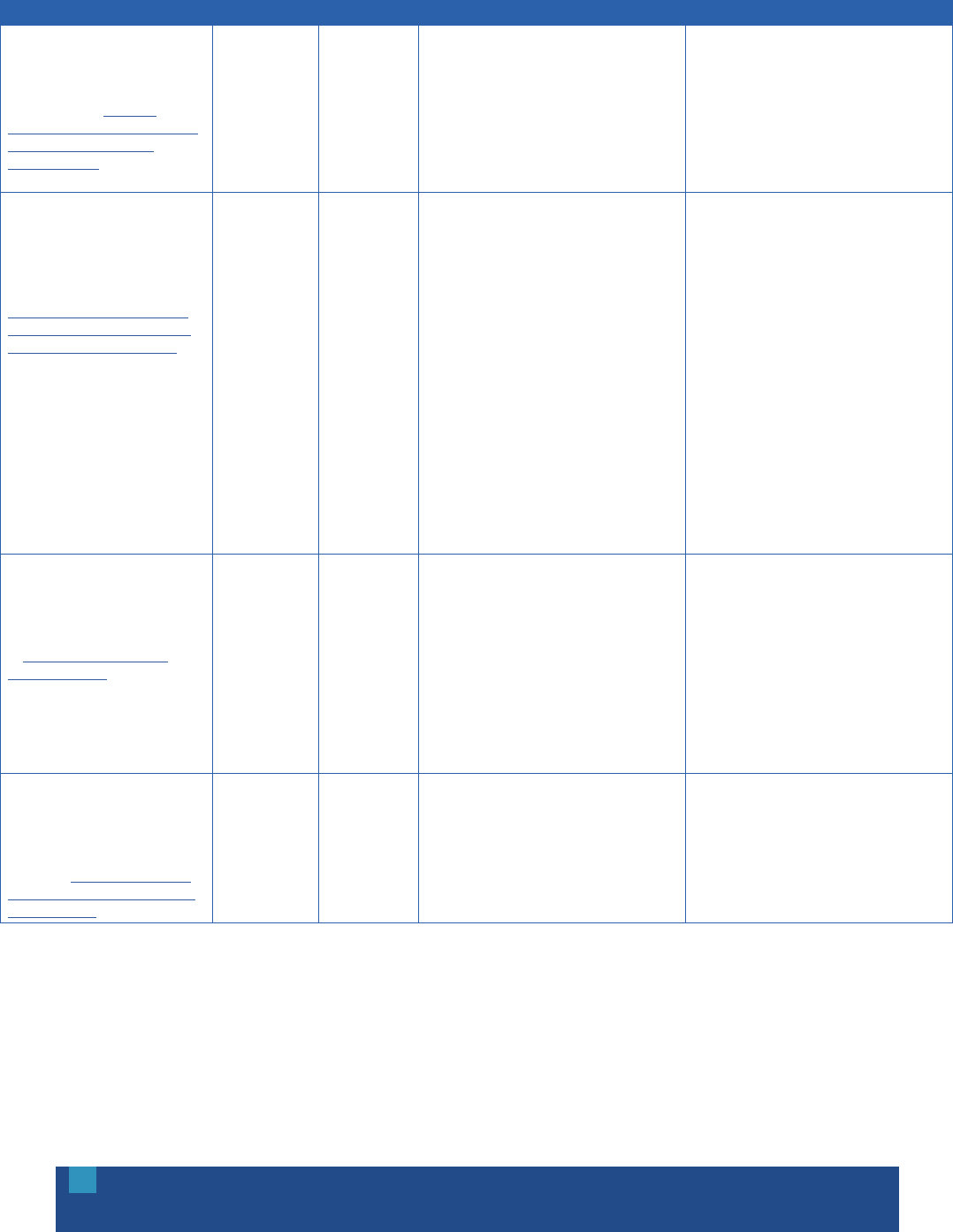

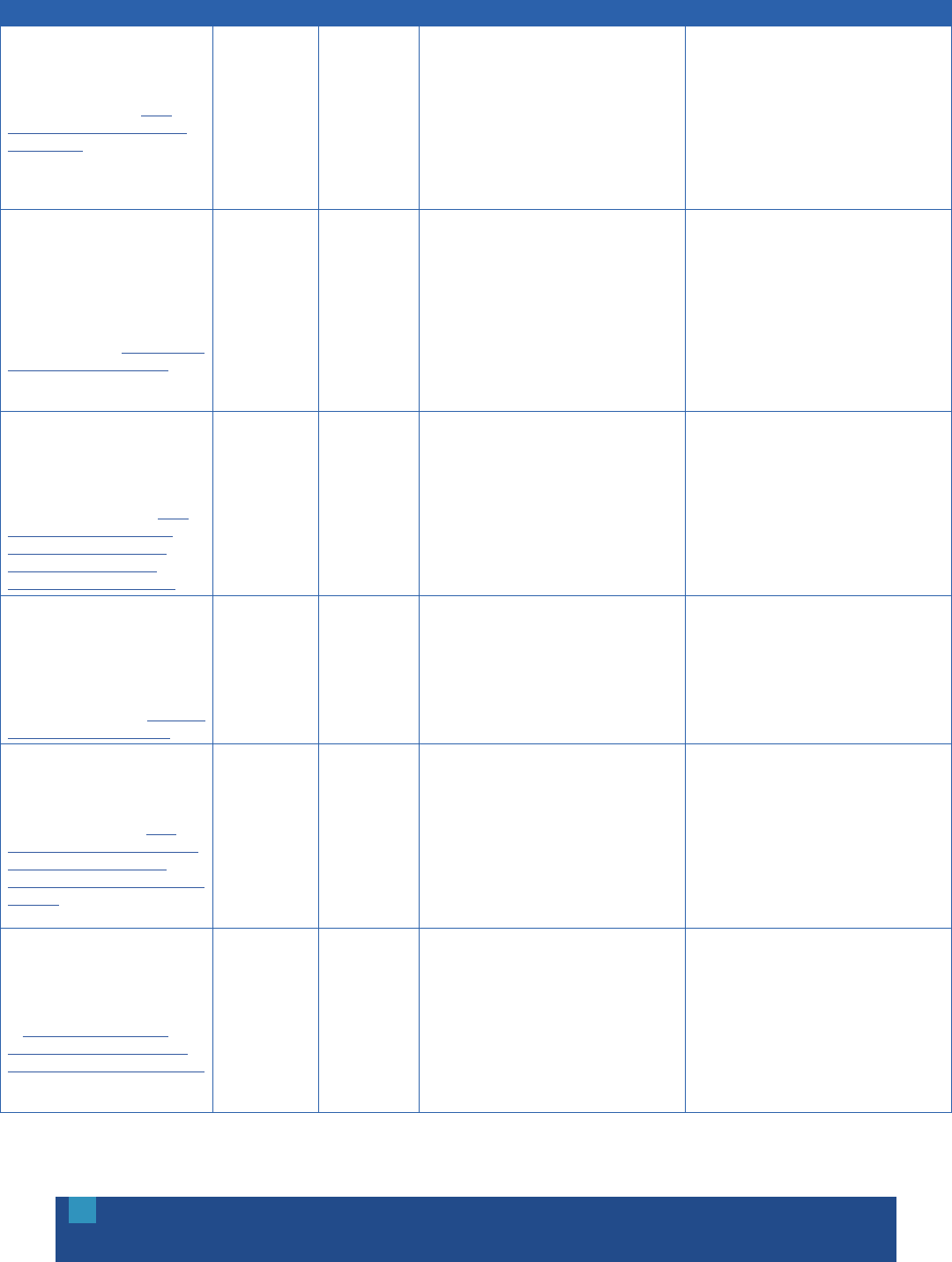

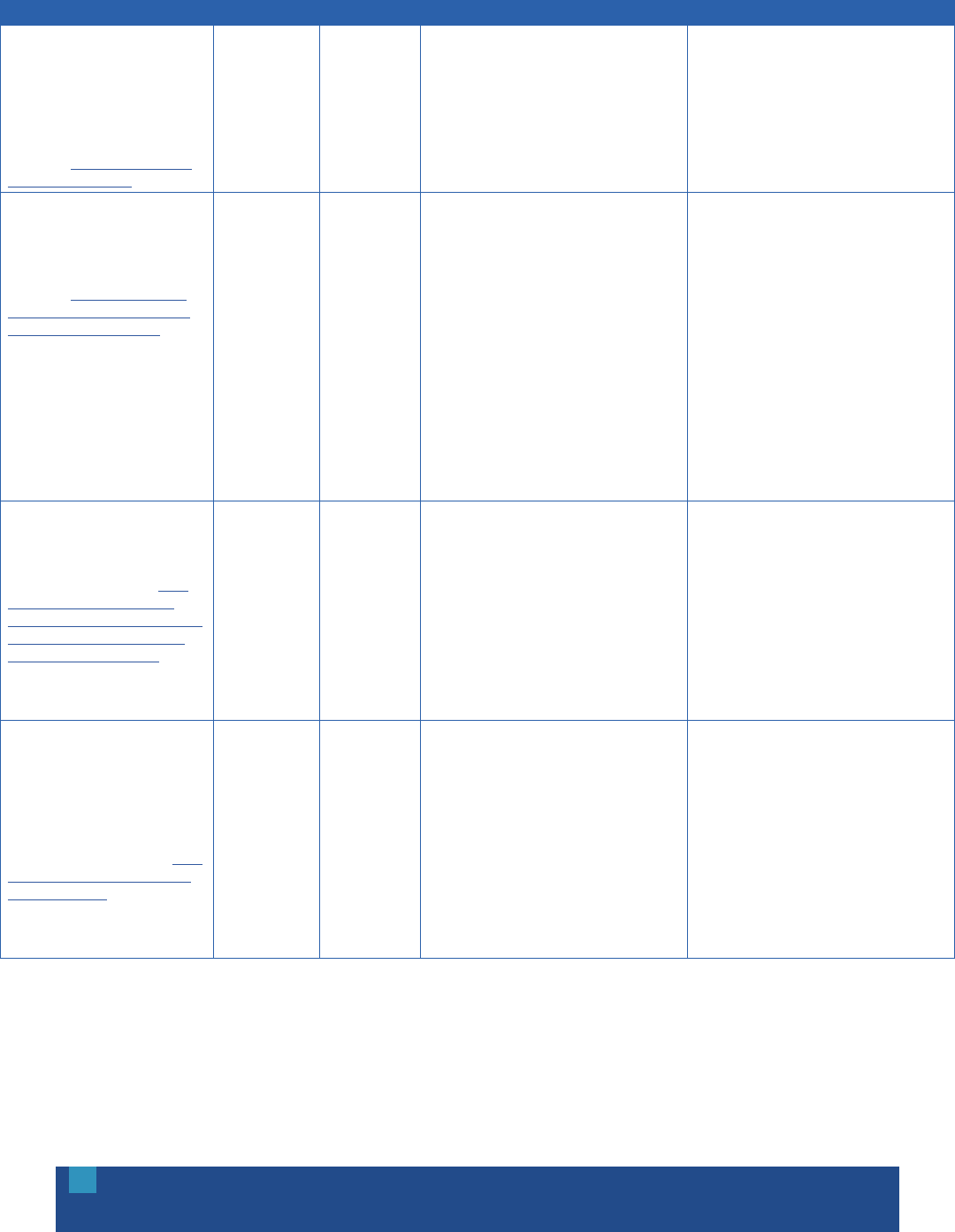

A

ll of the documents reviewed for this literature review are indexed in the following pages. The following

information is provided for each document analyzed in the literature review: (1) full citation and link as available;

(2) target population; (3) key focus; (4) summary of model/intervention; and (5) a summary of key findings. The

literature is organized under five core domains: (1) Care Model Enhancements; (2) Financing and Accountability; (3) Data

and Analytics; (4) Workforce Development; and (5) Policy and Advocacy.

APPENDIX A: CARE MODEL ENHANCEMENTS

Citation Target Population Key Focus Summary of Model/Intervention Key Findings/Outcomes

Aligning Forces for Quality. “Creating

Regional Partnerships to Improve Care

Transitions.” The Robert Wood Johnson

Foundation. June 2014. Available at:

http://forces4quality.org/node/7600.

Elderly or patients

with serious

or complex

conditions

Care transitions Basics of partnerships include: establishing a

cross-setting oversight team with the common

goal of reducing readmissions and improving

quality of life; providing care transition coaching

services to partner with hospitals with certain

conditions/diagnosis; sharing data and results

to assess progress toward goals; establishing

a subgroup to discuss operational issues,

coordinate scheduling of services, and improve

communication concerns.

Effective care transitions programs call for

building and sustaining strong partnerships

with health care providers in the community so

they can collaborate to achieve shared goals.

Accomplishing this is difficult in single-setting

work and becomes even more challenging and

complex when bringing providers from different

care settings together who do not typically

work with one another and approach their

work differently. Consider partnering with local

hospitals, home health agencies, area agency on

aging, and physicians.

L. Barlow. “Hospitals, Physicians

Embrace Strategies To Reduce Cost of

“Frequent Flyer” ER Visits.” Real World

Health Care. April 2013. Available

at: http://healthwellfoundation.org/

sites/default/files/4.9.13.Hospitals.

Physicians%20Embrace%20

Strategies%20to%20Reduce%20

FF%20Visits%20to%20ER.pdf.

High-frequency

emergency

department (ED)

utilizers

Intensive care

management

Two models in different states (North Carolina

and Washington). In NC, a free clinic integrates

medical checkups and group therapy, with doctors

providing treatment and patients offering each other

tips, ranging from how to obtain legal assistance

to saving money on food and shelter. In WA, a

community program was joined other hospitals and

a regional coalition of providers. It flags patients

with 2+ ED visits in a month or 4+ visits in 6

months for further examination and care planning.

The NC model reduced total ED expenses by

$405,000 over 12 months. Uninsured participants

reduced ED visits from an average of 7 to an

average of 3 per year. In WA, ED visits among

frequent flyers reduced by 50%, with a cost

savings of almost $10,000/patient. The program

saw a reduction of $2.2 million in ED and inpatient

expenses over two years.

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

17

Citation Target Population Key Focus Summary of Model/Intervention Key Findings/Outcomes

J. Bell, D. Mancuso, T. Krupski, J.M.

Joesch, D.C. Atkins, B. Court, et al. A

Randomized Controlled Trial of King

County Care Partners’ Rethinking

Care Intervention: Health and Social

Outcomes up to Two Years Post-

Randomization Technical Report.

Center for Health Care Strategies.

November 2012. Available at: http://

www.chcs.org/resource/randomized-

controlled-trial-of-king-county-care-

partners-rethinking-care-intervention-

health-and-social-outcomes-up-to-

two-years-post-randomization/.

Aged, Blind, and

Disabled Medicaid

beneficiaries

with evidence of

mental illness

and/or chemical

dependency,

identified as

being at risk of

having future high

medical expenses

Intensive care

coordination

Washington State’s Rethinking Care intervention

included intensive care management from

a clinical team of RNs and social workers.

Care management included an in-person

comprehensive assessment of medical and

social needs; collaborative setting of health-

related goals; chronic disease self-management

coaching; physician visits of clients accompanied

by their care managers; frequent in-person and

phone monitoring by care managers; connection

to community resources; and coordination of care

across the medical and mental health system.

Participants in the intervention were likelier to

have increased access to care, lower inpatient

medical costs, relatively fewer unplanned inpatient

admissions, and fewer deaths. In particular, those

in the intervention group: (1) had a lower increase

in inpatient medical admissions—8% versus a

20% increase in the comparison group; (2) had a

2% decrease in average PMPM cost for inpatient

medical admissions following an ED visit (e.g.,

unplanned admissions) compared to a 49% cost

increase for the comparison group; (3) had a 5%

increase in outpatient medical costs versus a

12% decrease in the comparison group; and (4)

were less likely to experience homelessness—

there was a 20% decrease in beneficiaries who

experienced at least one month of homelessness

following the intervention compared to an 18%

increase in the comparison group.

T. Bodenheimer and R. Berry-Millett.

“Care Management of Patients With

Complex Health Needs.” Robert Wood

Johnson Foundation. December

2009. Available at: http://www.rwjf.

org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_

briefs/2009/rwjf49853/subassets/

rwjf49853_1.

Individuals with

complex health

care needs

Complex care

management

Key components to care management: (1)

identify patients most likely to benefit from care

management; (2) assess the risks and needs of

each patient; (3) develop a care plan together

with the patient/family; (4) teach the patient/

family about the diseases and their management,

including medication management; (5) coach the

patient/family on how to respond to worsening

symptoms in order to avoid the need for hospital

admissions; (6) track how the patient is doing over

time; and (7) revise the care plan as needed.

Mixed results as to whether care management

reduces hospital use and health care costs.

Stresses on primary care make it difficult to

implement effective care management. The most

effective programs target complex patients being

discharged from the hospital. Home-based care

management has largely failed to demonstrate

significant cost/quality improvements. More

success is seen if the right patients are picked:

those that are complex, but not those whose

illness is so severe that palliative or hospice care

is more appropriate. Medicare demonstrations of

care management involving patients with complex

health care needs have failed to find consistent

cost reductions (with a few exceptions). Care

management requires personnel with particular

skills not generally taught in traditional health

professional educational institutions. Integrated

delivery systems have the most resources and

capacity to develop care management programs.

T. Bodenheimer. Strategies to Reduce

Costs and Improve Care for High-

Utilizing Medicaid Patients: Reflections

on Pioneering Programs. Center for

Health Care Strategies. October 2013.

Available at: http://www.chcs.org/

resource/strategies-to-reduce-costs-

and-improve-care-for-high-utilizing-

medicaid-patients-reflections-on-

pioneering-programs/.

Super-utilizers Complex care

management

Principal sites for complex care management

models: health plan, primary care, ambulatory

intensive care unit (aICU), hospital discharge,

emergency department-based, home-based,

housing first, and community-based.

High-utilizer programs can make substantial

reductions in hospital admissions, hospital days,

ED visits, and total costs of care. Providing

permanent housing with case management—

with no medical personnel—appears to be the

most powerful way to reduce costly health care

utilization. There is a big difference between the

aICU model and the primary care model. There

is no standard composition of care management

teams. Most programs perform an initial

assessment, develop a care plan, and incorporate

regular follow-up by the care management team.

Programs tend to have a coaching rather than a

rescuing philosophy. Many programs have a home

visit component; some allow patients to access

the care management team 24/7. Coaching

patients to understand their medications and to

become more medication adherent is an essential

feature of all programs. Caseloads vary with team

size, team composition, and patient complexity.

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

18

Citation Target Population Key Focus Summary of Model/Intervention Key Findings/Outcomes

R.S. Brown, D. Peikes, G. Peterson, J.

Schore, and C.M. Razafindrakoto. “Six

Features Of Medicare Coordinated

Care Demonstration Programs That

Cut Hospital Admissions Of High-Risk

Patients.” Health Affairs, 31, no. 6

(2012): 1156-66. Care Management

Toolkit.” Available at: http://content.

healthaffairs.org/content/31/6/1156.

abstract.

High-risk

Medicare

beneficiaries

Intensive care

management

The six approaches practiced by care coordinators

in the Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration

programs that were effective include: (1)

supplementing telephone calls to patients with

frequent in-person meetings; (2) occasionally

meeting in person with providers; (3) acting as a

communications hub for providers; (4) delivering

evidence-based education to patients; (5)

providing strong medication management; and (6)

providing timely and comprehensive transitional

care after hospitalizations.

Four of 11 Medicare Coordinated Care

Demonstration programs reduced hospitalizations

by 8-33 percent among enrollees who had a high

risk of near-term hospitalization. Results suggest

that incorporating these approaches into medical

homes, accountable care organizations, and other

policy initiatives could reduce hospitalizations and

improve patients’ lives. However, the approaches

would save money only if care coordination fees

were modest and organizations found cost-effective

ways to deliver the interventions. None of these

programs generated net savings to Medicare.

California Quality Collaborative

(2012). “Complex Care Management

Toolkit.” Available at: http://www.

calquality.org/storage/documents/

cqc_complexcaremanagement_toolkit_

final.pdf.

Individuals with

multiple chronic

conditions, limited

functional status,

and psychosocial

needs

Complex care

management

Typical complex care management models:

(1) embedded care manager model (care

manager located onsite); (2) centrally located

care management agency provides services to

multiple practice sites; or (3) “brick and mortar”

clinic where an “intensivist” is assigned a high-

risk patient panel. Care teams usually consist

of a nurse care manager, PCP, social worker,

behavioral health specialist, and other care

providers as necessary.

Key considerations for building a care model for

complex patient populations include: developing

levels within your complex care program that vary

based on severity of illness; taking a broad and

interdisciplinary approach to building your complex

care team—build on what you have and align

with the needs of the patients you are managing;

promoting face-to-face interaction between care

managers and patients; emphasizing patient self-

management techniques; making care transitions

support a priority; and using virtual or in-person

multi-disciplinary case conferences.

Corporation for Supportive Housing

(2009). “Summary of Studies:

Medicaid/Health Services Utilization

and Costs.” Available at: http://

pschousing.org/files/SH_cost-

effectiveness_table.pdf.

Criteria varies;

primarily

individuals who

are homeless or

unstably housed

with multiple

chronic conditions

Housing

intervention

Variety of housing programs implementing

“housing first” interventions for complex-needs

individuals. Evaluated for utilization of health and

other services.

Select Key Impacts

San Francisco: During the one year after entering

supportive housing, individuals had fewer ED visits

and fewer inpatient hospital admissions.

Chicago Housing for Health Partnership

Program: Fewer hospitalizations per person per

year; fewer ED visits per person per year (24%

reduction); 45% fewer days nursing home.

Massachusetts Statewide Pilot: Medicaid costs

after housing intervention significantly decreased.

Connecticut Partnership for Strong

Communities (2012). “Connecticut

Integrated Healthcare & Housing

Neighborhoods.” Available at: http://

pschousing.org/files/Connecticut%20

Integrated%20Healthcare%20and%20

Housing%20Neigborhoods%20

Summary%20%28March%20

2012%29.pdf.

Medicaid-

enrolled/ eligible

high-utilizers who

are homeless

or at-risk of

homelessness,

with chronic

conditions

Housing

intervention

Health home outreach model using assertive

outreach and care coordination to link high-cost,

high-need clients with primary care, behavioral

health care, and supportive/affordable housing.

Multidisciplinary health teams established in

multiple regions of the state through partnerships

between Federally Qualified Health Centers, Local

Mental Health Authorities, and supportive housing/

public housing providers, homeless service/

outreach programs, and the state’s Medicaid

Medical Administrative Services Organization

(ASO). High utilizers identified through local

hospitals to ensure effective transitions from care.

In Connecticut, an identified cohort of adult

Medicaid beneficiaries who are homeless,

high-cost utilizers of health services had average

annual Medicaid payments of $67,992 per

person. This is 9 times more expensive than the

average Medicaid beneficiary. In 2011, the state

budget dedicated $100 million to affordable

housing over two years and $30 million in capital

funding to develop 150 new units of additional

supportive housing. In February, Gov. Malloy

announced his housing proposal for the state

budget, which includes $300 million over 10 years

for public housing revitalization, an additional $20

million for affordable housing, and 150 new rental

assistance vouchers for scattered site supportive

housing.

R. Davis and A. Maul. Trauma-Informed

Care: Opportunities for High-Need,

High-Cost Medicaid Populations.

Center for Health Care Strategies.

March 2015. Available at: http://www.

chcs.org/resource/trauma-informed-

care-opportunities-high-need-high-

cost-medicaid-populations/.

High-need, high-

cost Medicaid

beneficiaries

Trauma-informed

care

Individuals who experience trauma, particularly

in childhood, have much higher incidences of

chronic disease and behavioral health issues.

Trauma-informed care seeks to change the

clinical perspective from asking, “What is wrong

with you?” to “What happened to you?”

Using trauma-informed care to better engage

with this difficult-to-reach population can help

providers and case managers build a trusting

relationship with individuals with a history of

trauma, and may help enhance quality and cost

outcomes for the Medicaid program overall.

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

19

Citation Target Population Key Focus Summary of Model/Intervention Key Findings/Outcomes

M. Gerrity, E. Zoller, N. Pinson, C.

Pettinari, and V. King. “Integrating

Primary Care into Behavioral Health

Settings: What Works for Individuals

with Serious Mental Illness.” Millbank

Memorial Fund. 2014. Available at:

http://www.milbank.org/uploads/

documents/papers/Integrating-Primary-

Care-Report.pdf.

Individuals with

serious mental

illness and

substance use

disorder

Behavioral health

integration

Behavioral health integration into primary care

for individuals with serious mental illness (SMI).

The continuum of models ranges from separate

systems and practices with little communication

among providers, to enhanced coordination and

collaboration among providers usually involving

care or case managers, to co-located care with

providers sharing the same office or clinic, to

fully integrated care where all providers function

as a team to provide joint treatment planning. In

a fully integrated system, patients and providers

experience the operation as a single system

treating the whole person.

Care management may improve mental health

symptoms and mental health related quality of life

for patients with bipolar disorder and SMI. Fully

integrated care and care management improves

use of preventive and medical services and may

improve physical health symptoms and quality

of life for patients with bipolar disorder and SMI.

Co-locating primary care in chemical dependency

treatment settings without enhanced coordination

and collaboration does not improve mental

or physical health outcomes. All interventions

required additional staff, training, and oversight

except when intervention staff was dually trained

in primary care and substance use treatment.

J. Greene, J.H. Hibbard, R. Sacks, V.

Overton, and C.D. Parrotta. “When

Patient Activation Levels Change,

Health Outcomes And Costs Change,

Too.” Health Affairs, 34, no. 3 (2015):

431-437. Available at: http://content.

healthaffairs.org/content/34/3/431.

abstract.

Adult primary care

patients

Patient activation Patient Activation Measure (PAM) scores collected

during primary care office visits at baseline (in

2010) and two years later (2012) were examined

against health outcomes related to cholesterol,

triglycerides, PHQ-9, smoking, and obesity.

Higher activation in 2010 was associated with

nine out of thirteen better health outcomes—

including better clinical indicators, more healthy

behaviors, and greater use of women’s preventive

screening tests—as well as with lower costs

two years later. More activated patients were

significantly more likely than less activated

patients to have HDL, serum triglycerides, and

PHQ-9 in the normal range; to be nonsmokers;

and not to be obese. Future research is needed

to establish whether or not the association

represents a causal relationship.

D. Hasselman. Super-Utilizer Summit:

Common Themes from Innovative

Complex Care Management Programs.

Center for Health Care Strategies.

October 2013. Available at: http://

www.chcs.org/resource/super-utilizer-

summit-common-themes-from-

innovative-complex-care-management-

programs/.

Super-utilizers Intensive care

management

Care teams typically include nursing, social work,

and community outreach expertise. Interventions

include extensive outreach and engagement;

24-hour on-call system; frequent contacts with

patients (face-to-face is priority); medication

reconciliation/management; patient-caregiver self-

management education; timely outpatient follow-

up post-discharge; linkage to a primary care

provider/medical home; goal setting and care plan

development; health education/coaching; pain

management; management of chronic conditions

(e.g., diabetes, asthma); preparation for provider

visits; and linkages to housing, substance abuse

treatment, and other community resources.

Individuals’ basic needs—housing, jobs, child

care, and food insecurity—must be addressed

before physical health can be impacted. Programs

“frontload social services” and typically use

non-clinicians and non-traditional providers such

as social workers and community health workers

to address gaps in and needs for social services.

Essential to figure out which patients need which

interventions in which setting by which provider—

this complex equation was noted as the “holy

grail.” Medication management is a critical task

that must be done in the patient’s home to be

most effective.

J. Hibbard, J. Greene, and M. Tusler.

“Improving The Outcomes of Disease

Management by Tailoring Care to the

Patient’s Level of Activation.” The

American Journal of Managed Care,

15, no. 6 (2009): 353-360. Available

at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

pubmed/19514801.

Individuals with

chronic conditions

Patient activation A quasi-experimental pre-post design was

utilized, with an intervention group, using a

tailored approach and a control group was

coached in the usual way. Intervention coaches

used baseline Patient Activation Measure (PAM)

scores to segment patients based on 4 levels of

activation. The coaches were then trained and

given guidelines to customize telephonic coaching

based on the activation level.

Findings suggest that using tailored coaching

models to the patients’ activation level with

alignment of metrics improves outcomes for

disease management.

J. Hibbard, J. Greene, Y. Shi, J. Mittler,

and D. Scanlon. “Taking the Long View:

How Well Do Patient Activation Scores

Predict Outcomes Four Years Later?”

Medical Care Research and Review,

Published online, February 24, 2015:

doi: 10.1177/1077558715573871.

Available at: http://mcr.sagepub.com/

content/early/2015/02/24/10775587

15573871.abstract.

Individuals with

chronic conditions

Patient activation Researchers examined the extent to which

characteristics such as medication adherence,

health behaviors, functional health, and costly

health care utilization were related to PAM scores

at baseline and 4 years later.

The benefits of patient activation are enduring,

and include: better self-management, improved

functioning, and lower use of costly health care

services over time. When activation levels change,

many outcomes change in the same direction.

Health care delivery systems can use this

information to personalize and improve care.

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

20

Citation Target Population Key Focus Summary of Model/Intervention Key Findings/Outcomes

J.Y. Kim, T.C. Higgins, D. Esposito,

A.M. Gerolamo, and M. Flick. SMI

Innovations Project in Pennsylvania:

Final Evaluation Report. Mathematica

Policy Research. October 2012.

Available at: http://www.chcs.org/

resource/smi-innovations-project-in-

pennsylvania-final-evaluation-report/.

Adult Medicaid

beneficiaries

with SMI and co-

occurring physical

health conditions

Complex care

management

The programs varied, but were based on five key

principles: (1) information exchange and joint

care planning across physical and behavioral

health; (2) engaging consumers in care; (3)

engaging providers to partner in care and become

designated care homes; (4) providing follow-

up after hospitalizations and ED visits; and (5)

improving medication management. Plans also

had performance bonuses.

Although outcomes varied across the two regions,

the evaluation identified that one or both pilots

were successful at reducing the rate of mental

health hospitalizations, all-cause readmissions,

and emergency department visits. Compared

with projected trends in these outcomes

without the interventions: (1) the rate of mental

health hospitalizations was an estimated 12

percent lower (Southwest); (2) the all-cause

readmission rate was an estimated 10 percent

lower (Southwest); and (3) the rate of emergency

department (ED) use was an estimated 9 percent

lower (Southeast).

K.W. Linkins, JJ. Brya, D.W. Chandler.

“Frequent Users of Health Services

Initiative: Final Evaluation Report.”

California HealthCare Foundation.

August 2008. Available at: http://

www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20

LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/F/PDF%20

FUHSIEvaluationReport.pdf.

Frequent

emergency

department (ED)

users

Intensive care

management

Six models ranged from various types of

intensive case management to less intensive

peer- and paraprofessional-driven interventions.

All interventions sought to redirect care from

the emergency department to lower-cost

community-based settings by: assisting frequent

users to access and navigate existing resources;

decreasing psychosocial problems such as

homelessness and substance use; and improving

care coordination.

The programs yielded statistically significant

reductions in ED use (30%) and hospital charges

(17%) in the first year of enrollment. ED utilization

and charges decreased by an even greater

magnitude in the second year after enrollment.

Those connected to housing showed significantly

greater reductions in the number of inpatient days

(a 27% decrease for those connected vs. a 26%

increase for those not connected) and inpatient

charges (a 27% decrease for those connected vs.

a 49% increase for those not connected).

D.B. Mautner, H. Pang, J.C. Brenner,

J.A. Shea, K.S. Gross, R. Frasso, et al.

“Generating Hypotheses About Care

Needs of High Utilizers: Lessons from

Patient Interviews.” Population Health

Management, 16, Suppl. (2013): S26-

33. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.

nih.gov/pubmed/24070247.

Complex, high-

utilizing patients

Social

determinants

of health

This qualitative study identifies psychosocial

factors and life experiences described by complex

patients with high levels of emergency and

hospital-based health care utilization that may be

important to their care needs. Semi-structured

interviews were conducted with 19 patients of the

Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers’ Care

Management Team.

Investigators identified three key themes: (1)

Early-life instability and traumas, including

parental loss, unstable or violent relationships, and

transiency, informed many participants’ health and

health care experiences; (2) many “high utilizers”

described a history of difficult interactions with

health care providers during adulthood; (3) over

half of the participants described the importance

to their well-being of positive and “caring”

relationships with primary health care providers

and the outreach team. Additionally, the transient

and vulnerable nature of this complex population

posed challenges to follow-up, both for research

and care delivery. Investigators should test new

modes of care delivery that attend to patients’

trauma histories.

C. Michalopoulos, M. Manno, S.E. Kim,

and A. Warren. “The Colorado Regional

Integrated Care Collaborative Managing

Health Care for Medicaid Recipients

with Disabilities: Final Report on the

Colorado Access Coordinated Care Pilot

Program.” MDRC, April 2013. Available

at: http://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/

files/Managing_Health_Care_FR.pdf.

Blind or disabled

Medicaid

recipients

(considered

high-risk for

hospitalization)

Intensive care

coordination

Colorado Access provided intensive coordinated

care services, with a focus on social and

nonclinical service delivery. Coordinated care was

provided primarily by telephone, care managers

sometimes met members in person (facilitated by

having care team members in Kaiser Permanente

Colorado’s clinics).

There is little evidence that the Colorado Access

program affected outpatient care. Of the six

outcomes examined, there were significant

estimated impacts only on the probability of

visiting a non-physician. The average number

of admissions per 1,000 client months during

the first year was 24.0 for the program group

compared with 20.0 for the control group.

C.J. Peek, M.A. Baird, and E. Coleman.

“Primary Care for Patient Complexity,

Not Only Disease.” Family, Systems

and Health, 27, no. 4 (2009): 287-302.

Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/pubmed/20047353.

Patients with

multiple chronic

conditions

Assessment Analysis of what is meant by “complexity” in

primary care setting and how to best tailor care

delivery to complex patients.

Patient complexity is defined as “interference with

standard care and decision-making by symptom

severity or impairments, diagnostic uncertainty,

difficulty engaging care, lack of social safety or

participation, disorganization of care, and difficult

patient-clinician relationships. Patient-centered

medical homes must address patient complexity

by promoting the interplay of usual care for

conditions and individualized attention to patient-

specific sources of complexity—across whatever

diseases and conditions the patient may have.

OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE MODELS OF CARE FOR PEOPLE WITH COMPLEX NEEDS: LITERATURE REVIEW

21