Abilene Christian University Abilene Christian University

Digital Commons @ ACU Digital Commons @ ACU

Masters of Education in Teaching and Learning Masters Theses and Projects

Spring 5-6-2022

Getting it Write: The In9uence of Growth Mindset on Secondary Getting it Write: The In9uence of Growth Mindset on Secondary

Students' Perceptions of Their Writing Abilities Students' Perceptions of Their Writing Abilities

Megan Hertz

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/metl

Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Secondary Education and Teaching

Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Hertz, Megan, "Getting it Write: The In9uence of Growth Mindset on Secondary Students' Perceptions of

Their Writing Abilities" (2022).

Masters of Education in Teaching and Learning

. 52.

https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/metl/52

This Manuscript is brought to you for free and open access by the Masters Theses and Projects at Digital

Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters of Education in Teaching and Learning by an

authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU.

GETTING IT WRITE 1

Getting it Write: The Influence of Growth Mindset on Secondary Students’ Perceptions of

Their Writing Abilities

Megan Hertz

Abilene Christian University

GETTING IT WRITE 2

Abstract

This study investigated the ways in which growth mindset activities influenced secondary

students’ perceptions of their writing abilities and skills. The researcher introduced growth

mindset strategies, language, and instruction into two class periods of a 10th–grade English

classroom to improve students’ perceptions of their writing abilities and to develop students’

writing skills. Data were collected with pre– and post–intervention surveys, field notes, written

artifacts, and individual interviews. The constant comparative method was used to analyze

qualitative data to identify significant themes. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze

quantitative data. The researcher found the participants expressed improved resilience in

response to challenging tasks and a higher acceptance of making mistakes as a part of the

learning process. By the end of the intervention, the participants aligned with the principles of a

growth mindset, believed they had improved their writing skills, and more strongly identified

with the writer identity.

GETTING IT WRITE 3

Getting it Write: The Influence of Growth Mindset on Secondary Students’ Perceptions of

Their Writing Abilities

“Why do we have to do this?”

“Ugh, I hate writing.”

“This is so hard. I can’t do this.”

Such are the usual responses I got from students when they learned we were writing in

class, whether it was three sentences or a full essay. In my clinical teaching placement in a

sophomore English class, I heard students express that they hated writing, they were not good at

writing, and that they could not write time and time again. While I attempted to encourage my

students by telling them that challenges were good opportunities that could help us grow, my

students were often not receptive to such encouragement in the moment. With all of these

observations and experiences in mind, I wondered how I could reach my students to help them

see their success, particularly their perceptions of their writing abilities, as something that could

change and grow and as something that was within their control.

Purpose

Students who develop a growth mindset view failure as an inevitable and welcomed part

of the learning process (Dweck, 2015). In particular, students can develop a growth mindset

about their writing abilities to view them as skills that can be improved upon (Miller, 2020).

Furthermore, when educators instruct students and provide feedback aligned with growth

mindset attitudes, students experience increased motivation for writing (Jankay, 2020; Truax,

2018). I knew my students could benefit from developing a growth mindset particularly in

relation to their writing abilities and skills because they expressed an unwillingness to write

based on their lack of confidence in their writing abilities. If they could see their own potential to

GETTING IT WRITE 4

grow as writers, perhaps they would not be so resistant to writing in the classroom. I conducted

this action research study to find out how students’ perceptions of their writing abilities and

skills would change after receiving instruction about growth mindset. The study sought to answer

the following research questions:

Research Question 1: In what ways do growth mindset activities influence students’

perceptions about their writing abilities?

Research Question 2: In what ways do growth mindset activities influence students’ writing

skills?

This study took place during my yearlong clinical teaching placement as part of an M.Ed.

program in Teaching and Learning. I was placed in a high school in a West Texas city that had

an approximate population of 124,000. The high school had about 1,800 students enrolled and

was one of three high schools in the district. School records indicated the campus demographics

were the following: 15.4% of students were African American, 49.6% of students were Hispanic,

30.7% of students were White, 0.2% of students were American Indian, 1.2% of students were

Asian, and 2.9% of students were two or more races. Additionally, school records indicated 64%

of students enrolled on the campus were economically disadvantaged.

Literature Review

Students often begrudge or even despise the task of writing in the classroom, and many

resign themselves to failure even before trying. A growth mindset exists when a person sees

difficulties or challenges as a learning opportunity (Dweck, 2010). Students who develop a

growth mindset view challenges as beneficial, leading to an improved self–perception, increased

motivation, and greater achievement (Altaleb, 2021; Dweck, 2015; Jankay, 2020; Truax, 2018;

Yeager & Dweck, 2020). When students do not believe they have the capability to be a writer,

their motivation is nearly nonexistent (Barone et al., 2014), but when students believe their

GETTING IT WRITE 5

abilities can be improved upon, they face the writing process with greater resilience (Jankay,

2020; Miller, 2020; Seban & Tavsanli, 2015; Truax, 2018). Developing a growth mindset about

writing can help students learn to face this intimidating task with motivation and confidence,

resulting in greater achievement, authentic learning, and more positive perceptions of writing.

Creating a culture of growth mindset in the classroom begins with the educator. Teachers

must believe in their own abilities to develop their intellectual skills and in students’ potential for

progress and then use that foundation to form an atmosphere of growth in the classroom (Dweck,

2015). In addition to building a strong foundation, teachers must praise students for their process

rather than their intelligence, value depth of learning over speed, welcome mistakes and

encourage students to welcome struggles, and give students ownership over their choices to grow

their intelligence (Dweck, 2010). Although there have been challenges to the idea that a growth

mindset can reliably predict student outcomes, the existing literature on growth mindset has

found that there is justification for putting confidence in growth mindset research (Altaleb, 2021;

Dweck, 2010, 2015; Yeager & Dweck, 2020). While effects of growth mindset interventions

may differ from person to person, a growth mindset can still predict outcomes of student

achievement (Yeager & Dweck, 2020).

Growth mindset instruction helps students view failure as an inevitable part of learning.

Not only are students with a growth mindset more likely to overcome challenging experiences

(Altaleb, 2021; Yeager & Dweck, 2020), but they are also prepared to learn from mistakes they

do make in those situations (Jankay, 2020). Students can also experience an increase in

motivation when they learn to appreciate their own progress over time. Xu et al. (2021) found

that growth mindset instruction aided in students’ perceiving a lowered cognitive load during

GETTING IT WRITE 6

learning. Even a simple change in perception can help students feel greater confidence or self–

perception, and, therefore, a heightened sense of motivation.

When students feel motivated, they are willing to persevere in the face of difficult tasks,

leading to gains in student achievement. In addition to feeling more motivated, a growth mindset

helps students to shift their educational values from intelligence, performance, and success to

growth, progress, and deeper learning (Dweck, 2015). Specifically, when teachers implement

growth mindset strategies and provide students with feedback and language that reflects a growth

mindset perspective, student achievement is promoted; in fact, when teachers place too much

focus on proficiency, growth is discouraged (Altaleb, 2021). Growth mindset also teaches

specific skills to improve achievement. When facing challenges as opportunities to learn,

students can practice exercising problem-solving skills and build up their independence (Jankay,

2020). Honing skills that assist students in gradually taking more responsibility for their learning

results in students experiencing greater achievement.

In particular, growth mindset affects the ways in which students view writing tasks.

Miller (2020) conducted a study investigating a writing tutor’s role in changing university

students’ mindsets about their writing skills and found that a tutor could effectively change

students’ mindsets to view writing skills as something that could be improved. The students

learned to place more emphasis on improving general writing skills rather than performing well

on individual assignments. Additional studies using process–focused literacy and writing

interventions helped students (13 years old or younger) learn to appreciate the improvements

they made to their writing and grow more confident in their abilities and skills (Barone et al.,

2014; Seban & Tavsanli, 2015). When students are exposed to writing as a process throughout

GETTING IT WRITE 7

which they can grow in their abilities, skills, and identities as writers, they have more reason to

put faith in their own potential to improve their writing and grow as writers.

Instructors of writing are aware that mistakes and imperfection are a necessary part of the

writing process. On the other hand, students tend to have a negative view of academic writing

because assignments completed at school usually offer little to no student choice, causing

students to feel no connection to or ownership over their writing (Hales, 2017; Seban &

Tavsanli, 2015). Disconnected from their own voices when writing in the classroom, students

have limited opportunities to develop their identities as writers. Further, students tend to believe

that writing skills are natural gifts with which one is either endowed or not (Hales, 2017; Miller,

2020). Those for whom writing abilities appear to be absent based on academic performance

experience low self–perception and decreased motivation (Barone et al., 2014). However,

students’ understanding of writing and writers can improve over time with explicit instruction on

writing, abundant opportunities to write, and the development of a growth mindset, all of which

influence perceptions to become more positive (Barone et al., 2014).

Existing studies examined students’ perceptions of writing, the general effects of growth

mindset, and how growth mindset specifically affected students’ perceptions of writing.

However, the literature regarding growth mindset’s effects on high school students’ perceptions

of their writing abilities and its effects on their writing skills is limited. Secondary students

dislike writing and believe they are not good writers because they are trapped in the mindset that

writing skills are gifts they do not possess. This mentality blocks students from improving their

writing and makes teaching writing near impossible. With more research about the effects of

growth mindset on students’ perceptions of writing, their abilities, and their skills, writing

instruction could be improved to be made more effective and impactful for high school students.

GETTING IT WRITE 8

Methods

This action research study was conducted in two class periods of a sophomore English

classroom. Data were collected through pre– and post–intervention surveys (see Appendix A),

student written artifacts, individual interviews, and head notes. The constant comparative method

(Hubbard & Power, 2003) and leveled coding (Tracy, 2013) were used to analyze the qualitative

data. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the quantitative data (Hubbard & Power, 2003).

Participant Selection

The participants of this study were the students from the fourth period class and the

students in the sixth period class at my clinical teaching placement at Toney High School (all

names have been replaced with pseudonyms) who received parental consent and who assented to

participate in the study. These two class periods were selected based upon the students whom I

had heard be most vocal about their thoughts on writing in class. All of the students received

partial instruction through the intervention; however, I only collected data from students who

participated in the study. I sent home a parent information letter and permission form, and the

students were asked to sign an assent form. In these forms, it was made clear that participation

was entirely optional, participation would not affect the students’ grades in any way, and that

students could withdraw from the study at any point in time. Of the students in these two classes,

all who received parent consent and who gave their assent to the study participated. In the fourth

period class, one female student and three male students participated in the study. School records

indicated that the participant demographics for this class period were the following: one student

was Asian, and three students were White and Hispanic or Latino. Additionally, it was indicated

that of the participants in this class period, one student was classified as Gifted and Talented and

one student was classified as having 504 accommodations. In the sixth period class, three female

GETTING IT WRITE 9

students and two male students participated in the study. School records indicated that the

participant demographics for this class period were the following: two students were White, and

three students were White and Hispanic or Latino. Additionally, it was indicated that of the

participants in this class period, one student was classified as having 504 accommodations.

Data Collection

The intervention was the introduction and use of growth mindset activities and strategies,

which were created by the researcher and pulled from existing curriculum, in the classroom for

two to four weeks. The intervention included the daily, purposeful use of language and feedback

that reflected a growth mindset (for instance, “I haven’t mastered how to do this yet,” or “You’ve

been working on organizing your sentences to clearly convey your ideas, and that practice shows

in this essay!”), opportunities two to five times per week for students to reflect in writing and

aloud on what they had done well and with what they needed more practice, and explicit

instruction on what a growth mindset is and how to develop one. The explicit instruction was

done once at the beginning of the intervention period and was reinforced throughout the

intervention period through the growth mindset activities, strategies, and language used.

Data collection began with the students filling out a pre-intervention survey with a mix of

questions regarding their confidence in writing, their belief in their ability to grow as a writer,

what they believed they did well in their writing, what they believed they needed to improve

upon in their writing, and what, if anything, they believed would help them become a better

writer. This survey had a mixture of Likert scale questions (with the scale going from 1- strongly

disagree to 4-strongly agree) and open-ended questions.

As the intervention took place, I collected student artifacts, including but not limited to

reflections, essays, and other written responses, in order to collect samples of students’ writing.

GETTING IT WRITE 10

Based on the students’ responses to the pre-intervention survey, I pulled a purposive sample

(Patton, 1990) of three to six students with whom I conducted semi-structured interviews

(Hendricks, 2017). The purposive sample consisted of one student whose answers to the survey

questions showed a strong fixed mindset (i.e. their responses indicated they had low confidence

in their writing and/or believed they could not improve upon their writing), two students whose

answers to the survey question showed a mindset somewhere between fixed and growth (i.e.

their responses indicated they had neither significantly low nor significantly high confidence in

their writing and/or did not strongly believe or strongly disbelieve they could improve upon their

writing), and two students whose answers showed they had a strong growth mindset (i.e. their

responses indicated they had high confidence in their writing and/or strongly believed they could

improve upon their writing). The interviews were done with each student individually twice—

once early on in the intervention period and once near the end of the intervention period—and

were 10–15 minutes in length. The interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed. To

supplement and enhance student responses from their artifacts and interviews, I also kept head

notes in which I recorded my own observations and thoughts of students during the intervention

period. The head notes consisted of words and phrases regarding events that took place in class,

and they were then fleshed out after class (Hendricks, 2017).

At the conclusion of the intervention, students filled out a post–intervention survey. The

post–intervention survey had the same questions as the pre–intervention survey regarding their

confidence in writing, their belief in their ability to grow as a writer, what they believed they did

well in their writing, what they believed they needed to improve upon in their writing, and what,

if anything, they believed would help them become a better writer. The survey had a mix of

Likert scale questions and open–ended questions.

GETTING IT WRITE 11

Data Analysis

To analyze the qualitative data, I coded the data from the pre– and post–intervention

surveys, the student artifacts, the interview transcriptions, and the head notes using the constant

comparative method (Hubbard & Power, 2003). The process began with coding the first 20% of

the data to create 28 level 1 codes, which were short phrases that described the content of the

data (Tracy, 2013). The remaining 80% of the data was then coded using these level 1 codes.

From the level 1 codes, five level 2 codes were established based on the predominant themes of

the codes. For each level 2 code, I wrote memos explaining the meaning of the codes (Tracy,

2013) that were helpful in the indexing process. The indexing process involved organizing

hierarchies of categories and supporting codes with all of the data that had been coded (Hubbard

& Power, 2003). The codes from the data are provided in the codebook (see Appendix B), which

provides a list of the completed codes, their definitions, and examples from the data.

To analyze the quantitative data, I used descriptive statistics to evaluate the Likert scale

questions from the pre– and post–intervention surveys. I created a column chart for each Likert

scale question and recorded each participant’s responses to the question on the pre– and post–

intervention surveys (see Appendix C–G).

Findings

At the conclusion of my study, five themes seemed to encompass how my students felt

about writing and how I witnessed them change after learning about growth mindset and

intentionally reflecting on their writing abilities. First, they came to more strongly believe that

challenges could help them learn and increase their resilience. Second, they were able to see the

ways in which they could learn from their past experiences and mistakes. Third, they developed

an appreciation for the concept of a growth mindset and the belief that they could use it in their

GETTING IT WRITE 12

daily lives. Fourth, they were transparent about what they felt they were lacking with their

writing skills and abilities, but they acknowledged that they could and had improved their

writing skills. Fifth and finally, reflecting on their growth with writing helped them more

strongly identify with the writer identity.

Challenges Make Me Stronger in the End (Perspectives on Challenges)

As a large part of having a growth mindset is being willing to face challenges, I knew that

I needed to have an understanding of how my students felt and what they thought when tasked

with something intimidating or difficult. In my interviews with the participants, I asked them to

tell me if they would rather work on something easy or challenging. For the most part, the

participants expressed that they would prefer to work on something that is somewhat

challenging. When asked to expand on this line of thinking, Emmanuel said that a task balanced

between challenging and easy would give him more to think about. Likewise, Madilyn said that

she would rather do something challenging, but if it were to get too difficult then she would

rather do something easy. Jaxon, however, had a very different perspective from the other

participants I interviewed. His immediate response was to choose something easy, explaining

that the challenges he faces everyday make him feel too burned out to take on additional

challenges when given an option. His viewpoint was that if he could have the choice, he would

rather “go through something easy and then carry on with whatever [he is] doing.”

I also asked the participants to tell me how they felt when doing something challenging,

and overwhelmingly they expressed negative emotions. Each participant associated at least one

of the following feelings with completing challenging tasks: stress, frustration, anxiety,

annoyance, and/or laziness. Specifically, Madilyn, the participant whose pre–intervention survey

responses indicated a stronger fixed mindset, said that some challenges get so frustrating that she

GETTING IT WRITE 13

does not even feel like trying anymore. In spite of these negative feelings in response to

challenges, many of the participants also stated that they learned more from challenges and that

challenges made them stronger, especially after learning about a growth mindset. In her post–

intervention interview, Madilyn said she felt people do not learn anything from doing something

easy. Emmanuel conveyed a similar ideation, explaining that people learn through the process of

doing something challenging. The enhanced resilience in the face of challenges the participants

identified may be connected to the sense of accomplishment they felt after having successfully

completed a challenge. Emmanuel, Carly, and Madilyn specifically said they feel more

motivated, satisfied, and proud of what they have done after finishing something challenging. All

in all, the participants, with the exception of Jaxon, expressed they were initially frustrated by

challenges but found the outcome to be more rewarding and meaningful when they had to work

harder or make multiple attempts to accomplish a task.

I Might Not Accomplish Everything the First Time (Learning from Mistakes)

While being willing to face challenges is an essential component of developing a growth

mindset, reframing the way we think about mistakes is arguably even more important. When

asked how they felt when they make a mistake, the participants initially responded that they felt

negative emotions like shame, sadness, embarrassment, anger, frustration, disappointment, and

hurt. In my pre–intervention interview with Carly, she talked about how making mistakes

brought her confidence down. She felt that making mistakes indicated shortcomings or abilities

she was lacking. Esme explained that she felt angry with herself when she messed up because

she felt she was not meeting the expectations she and others had of her. I was particularly

interested in Madilyn’s response, though. She talked in–depth about how upset making mistakes

made her; she said she often got emotional to the point of breaking down because she felt like

GETTING IT WRITE 14

she was failing. When I asked her to reflect on why she reacts this way, she talked about a

particular experience at work in which she made a mistake while still learning how to fulfill the

duties of her job, and she got yelled at by her boss. At this point, we talked about how others’

responses to mistakes we make can intensify the initial emotions we feel when we mess up.

Though Madilyn would have felt upset by the mistake she had made anyway, her boss’s reaction

only made her feel worse about herself. These responses from the participants highlighted a

common thread between them—making mistakes tremendously affected their self–perception

and lowered their self–confidence.

Throughout the intervention period, the idea of learning from mistakes and framing

learning as a process came up again and again. By the end of the intervention, I had already seen

the participants grow by giving themselves more grace when they made mistakes and reacting

with resilience during the learning process. When it came time for the post–intervention

interviews, Esme discussed making mistakes in the classroom and how she had started to change

her view from being angry at herself to using her mistakes to show her areas in which she can

improve. She talked about going back through her work to find exactly where in the process she

made the mistake and how this perspective helped her easily fix her mistakes. Instead of feeling

angry, Esme said she realized it is okay to make mistakes and that now she will respond by

trying her best not to make the same mistake once she has learned from it. Carly also talked

about making mistakes at school, particularly with writing assignments. Her perspective was that

mistakes are inevitable but are opportunities to learn and try again. She reflected on her own

growth throughout her time in high school, saying it is okay to challenge yourself and fail as long

as you try again. Likewise, Madilyn showed growth in accepting mistakes and failure and

responding with resilience instead of breaking down like she used to. She even talked about an

GETTING IT WRITE 15

experience auditioning for something in one of her extracurriculars and how she used to be too

afraid of failing and embarrassing herself in front of others to even try but that she overcame

those feelings. She explained that her view had changed and that now she felt that if a person

makes one mistake and gives up, then they are not going to grow at all. Though the participants

still associated some negative feelings with making mistakes, they also expressed a higher degree

of acceptance in making mistakes and failing and stronger resilience in response to mistakes they

may make in the future.

I’m Getting There (Discussions on Growth Mindset)

When explicitly discussing mindset theory and what it means to develop a growth

mindset, I was surprised to find that many of the participants already aligned fairly well with a

growth mindset. While their degree of alignment differed, which can be seen in their survey

responses (see Appendix C–G), the participants all somewhat agreed with the basic ideas of

growth mindset; though they did not view themselves as writers or directly acknowledge that

their mistakes help them get better, every participant initially verbally agreed with the general

concept that people’s skills can grow during the direct instruction on mindset theory. In fact, they

believed this so innately that when I asked them why they thought that way, they struggled to

break it down and explain it. Abstractly, they accepted that improving skills was possible, stating

that growing is “what learning is at its core,” but they could not yet apply these ideas to their

own life experiences and mistakes.

By the end of the intervention period, the participants were developing a growth mindset

for themselves. All five of the participants whom I interviewed said they believed either that they

had a growth mindset or were coming to have a growth mindset. They expressed their beliefs

that a growth mindset could help them learn, challenge themselves, and ask for and accept help

GETTING IT WRITE 16

from others. Their ideas of how to use the principles of growth mindset in their daily lives and

how they would advise someone who was trying to develop a growth mindset showed their

ability to concretely understand growth mindset in a way they struggled to before the

intervention.

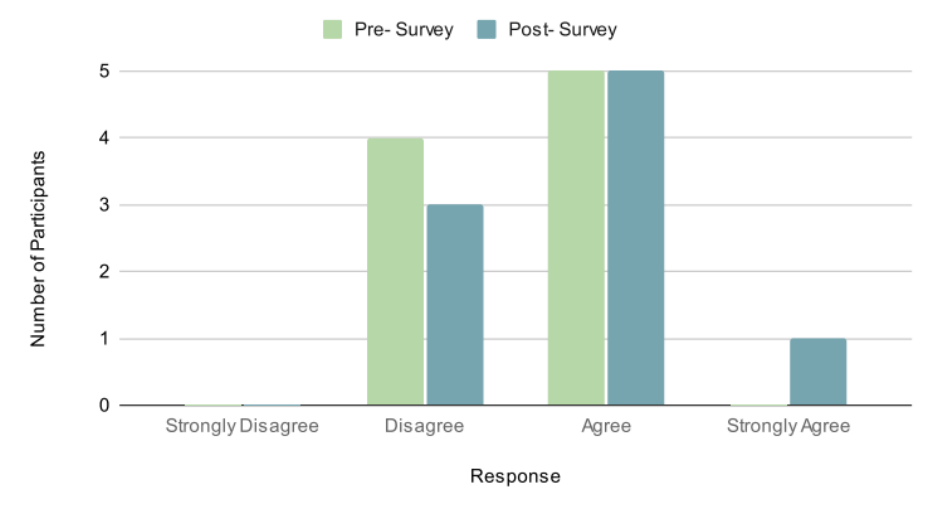

In applying the concepts of growth mindset to writing, by the end of the intervention

period, all of the participants agreed that they could improve their writing skills, which can be

seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

Responses to Question Four: I Have the Ability to Get Better at Writing

Note. This figure shows the difference between participants’ pre– and post–intervention survey

responses to question four: I have the ability to get better at writing.

Participants’ degree of alignment with growth mindset also changed when they

considered the flexibility of their writing skills specifically. At the beginning of the intervention

period, three students agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “My writing skills cannot

change,” whereas only one student agreed with that statement at the end of the intervention

GETTING IT WRITE 17

period (see Appendix G). Though the participants seemed to agree with the core idea of a growth

mindset initially, through explicit instruction and discussions about mindset theory, they were

able to practically apply it to their lives and begin developing a growth mindset for themselves.

I Can Always Get Better (Experiences of Writing at School)

Because the focus of my study was how a growth mindset might influence the students’

perceptions of their writing abilities, I honed in on how they felt about their writing and how they

believed their writing had changed over the course of the intervention period. The participants’

initial perceptions of writing were mostly negative, with each participant expressing at least once

during the intervention period that they did not like writing or that writing made them feel an

unpleasant emotion. Emmanuel explained that when he began working on writing assignments,

his initial thoughts were to worry about doing it wrong and messing something up. Esme simply

said she felt “horrible” when writing at school because she felt she did not know what to write,

which led her to lose her focus and her confidence in herself. Though the reasoning for their

distaste towards writing varied, largely the participants revealed that writing at school made them

feel worried and stressed and that they felt an inability to focus on the task at hand.

Many of the participants’ worries, anxieties, and frustrations with writing stemmed from

a lack of confidence in their abilities to meet the expectations they believed had been placed

upon them—expectations that only existed because of what they had been taught writing should

look like. Jaxon, who stated that he hated writing most often out of the five participants whom I

interviewed, explained he disliked having to write in a certain way. Jaxon told me, “I just hate

writing because it’s always like, … ‘you gotta give a spiritual reasoning for this.’” Jaxon also

expressed that he disliked writing in an academic setting because it did not seem applicable to

the real world. He described that “lazy” writing prompts encouraged him to give lazy reasoning

GETTING IT WRITE 18

in his writing because when he is working in the real world, he will not have to write “full essays

on why the Mona Lisa’s cool” or about “why cats have feelings.” Jaxon’s perspective was that if

the writing prompt could not benefit him in the real world, then it was not worth his time. In his

own words, “if you’re gonna put zero effort into a writing prompt, then don’t expect me to put

my full effort into [writing].” Jaxon was not the only participant frustrated with the reality of

writing at school, however. Three other students whom I interviewed also expressed that being

able to connect with what they were writing about helped them feel more motivated to write and

helped them feel more confident in their writing. Carly expressed that being able to relate to her

writing made it more enjoyable; similarly, Madilyn said that connecting writing with her

personal experiences helped it feel “more alive.” It seemed that when the writing assignment

allowed them to have more freedom to take ownership of their writing, the participants expressed

more positive feelings about writing and higher levels of confidence in their writing abilities. In

her post–intervention interview, Esme said she felt people should not worry about what others

think about their writing because “it’s your writing, no one else’s.”

In spite of much of the negativity surrounding writing, especially at school, the

participants also conveyed that writing was something people, including themselves, could get

better at, and the participants I interviewed revealed they believed they had seen their writing

improve throughout the research window. Overall, the participants also indicated on their post–

surveys that they were more confident in their writing abilities (see Appendix C). Though not

every participant identified themselves as a good writer or would have said that their writing

skills were necessarily “good,” they all acknowledged that they had grown in one area or another

and had ideas of what would help them get better at writing as they continued to learn. Carly and

Emmanuel both easily recognized they felt they had improved their writing. Even Jaxon, who

GETTING IT WRITE 19

still hated writing at the end of the intervention, admitted he did not feel he had seen “down–

provements” and had actually seen “up–provements” in his writing. Esme and Madilyn were

more hesitant to identify their growth. Esme confessed she was still slowly working on having

the confidence to be able to see herself as a good writer, but she eventually agreed that she had

seen her writing somewhat improve, too. Madilyn at first only focused on the areas she believed

she struggled, listing the reasons she did not see her writing as good just yet. She also revealed

she felt she was lacking the confidence that she believed good writers possessed. However, when

I asked if she had seen any improvements at all with her writing, she did admit she had seen

improvements with her understanding of writing and the methods of writing we had been using

in class. Finally, she allowed herself to recognize her own growth, stating, “I’m better than I was

last year.” Having reflected on their progress, I also asked the participants to consider what had

helped them grow and what could help them continue to make improvements. They listed the

following things that they believed would help them advance their writing: accepting feedback

and critiques, continuing to write and practice their skills, building their confidence with writing,

asking for help, and utilizing their teachers as resources.

I Don’t Have to Be the Best (The Writer Identity)

Much like the participants revealed their preconceived notions of what good writing

looks like, they also described assumptions of what a good writer is and does. Many participants

believed that a good writer should possess knowledge of their writing topic, control of writing

conventions, the ability to present their knowledge in an organized manner, the ability to express

their voice and personality in their writing, and confidence in their writing abilities. One other

common response from the participants was that neat handwriting made a person a good writer.

While that last attribute surprised me initially, I was able to identify the following connection

GETTING IT WRITE 20

between all of these responses: the participants listed abilities and characteristics they felt they

were lacking when describing what makes someone a good writer. Emmanuel and Jaxon both

listed neat handwriting as something good writers have and both expressed concern over whether

or not people could actually read their handwriting. Similarly, Madilyn talked about writing

conventions being important for writers while also lamenting her own struggles with

understanding punctuation. Esme and Carly both identified relevant knowledge as necessary for

being a good writer and explained that they lacked confidence in their writing the most when

they were unsure of what to write or when they did not understand the writing prompt or

assignment.

As the intervention period came to a close, the participants still felt that the previously

mentioned characteristics were what made people good writers, but they also showed stronger

identification with the identity of “writer.” Their responses indicated they were becoming more

confident in their abilities and thus more comfortable identifying with the term “writer.”

Emmanuel stated he believed he was a “decent writer” by the end of the intervention. Esme felt

she was “slowly becoming a good [writer].” Carly, though she felt she was not the best at

writing, said she felt she was capable of doing the same things she believed good writers can do.

Jaxon and Madilyn maintained that they felt they did not view themselves as good writers;

however, the participants overall came to more strongly identify with the writer identity, as

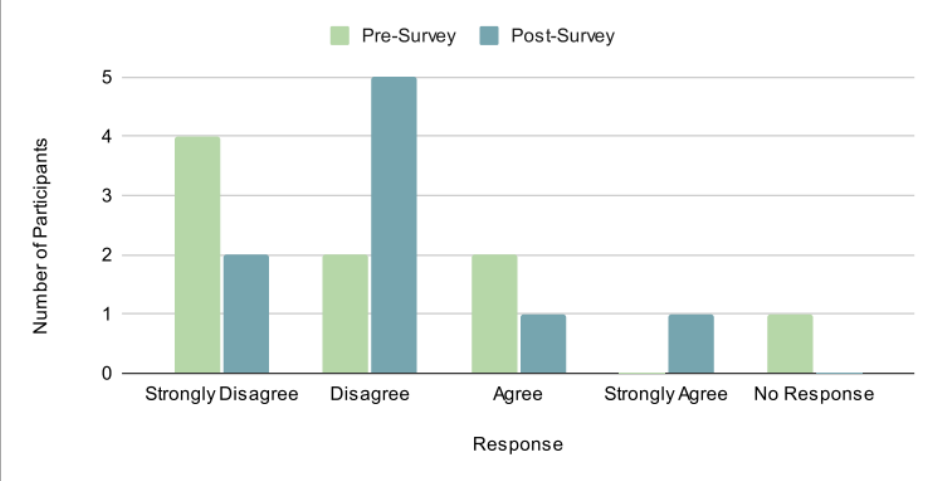

shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2

Responses to Question Two: I Am a Good Writer

GETTING IT WRITE 21

Note. This figure shows the difference between participants’ pre– and post–intervention survey

responses to question two: I am a good writer.

In comparing their pre– and post–survey responses, there were three participants whose

answers remained the same; one participant strongly agreed with the statement “I am a good

writer” before and after the intervention, and two participants (Jaxon and Madilyn) disagreed

with the statement before and after the intervention. However, the change indicated by the other

six participants was significant. One participant changed from strongly disagreeing to just

disagreeing, four participants changed from disagreeing to agreeing, and one participant changed

from disagreeing to strongly agreeing. Additionally, despite not explicitly identifying more

strongly with the identity of a good writer, Madilyn and Jaxon both acknowledged they had

improved their writing skills and believed they could and would continue to grow, which will

hopefully lead them to feeling more confident in using the label “writer” for themselves in the

future.

My hope for these specific participants and students everywhere is that they will come to

believe what Esme so wonderfully expressed in my first interview with her; to be a good writer,

GETTING IT WRITE 22

“you don’t have to be a good writer. You don’t have to be the best at it.” Once students accept

that being a good writer has very little to do with what they have been told a good writer should

be, they may feel liberated to express themselves in their writing and grow as writers in ways

they never allowed themselves to before.

Implications for Teachers

This study brought several things to my attention as an educator. First, students exhibit

incredible resilience and willingness to grow when provided the opportunity and support to do

so. Second, students have been taught, either explicitly or implicitly, that writing and writers fit

within certain confines that often do not match their writing or their own identities. Third,

students need educators to provide them opportunities to reflect on, recognize, and rejoice in

their progress.

For educators who want to help students develop a growth mindset in regards to their

writing abilities and skills, I recommend they begin with acquiring a deep understanding of their

students’ knowledge of writing, ideas about writers, and the students’ confidence in their own

writing. When I realized that my students were listing attributes and abilities that they believed

they did not possess when describing the qualities of a good writer, I knew I needed to bring that

fact to their attention. After pointing it out, a lot of them realized that what they were lacking was

confidence in themselves, and that that was truly the defining quality of a good writer.

Additionally, knowing which areas my students were struggling in allowed me to better

understand how I could support them in the classroom and help boost their confidence. Once

their confidence began to grow, their dislike for writing began to fade. To encourage students to

write, educators must first understand why they do not want to write in the first place.

GETTING IT WRITE 23

Once teachers have that understanding, they can begin to reframe what writing and

writers should look like, or rather they can begin dismantling students’ preconceived notions of

the limits to what writing and writers can be. Educators should be sure to emphasize that

academic writing is simply one genre of writing; not every writer writes the same way according

to the same styles, conventions, or rules. Students may need to follow academic writing

conventions for essays they will write in class, but they do not have to adhere to the same rules

when writing a creative story or a journal entry. Educators should highlight the ways in which

students can make writing their own. The earlier that educators can help students take ownership

of their writing, find their writing voice, and see themselves as writers, the better.

Finally, educators should teach students how to utilize a growth mindset with their

writing. Teachers should give students ample opportunities to reflect on their growth with

writing; everyday students can do something better than they did yesterday. Students should have

the chance to recognize their growth, too. Educators should ask them to talk or write about what

improvements they are seeing in their writing. Additionally, educators must show students how

to rejoice in their growth. From feedback as small as drawing a smiley face and writing specific

praise on an assignment to conferencing with a student about their areas of growth, students must

be constantly exposed to the idea that all progress is valuable and worth celebrating. Instead of

dreading all of the things they believe they cannot do in their writing, students will begin to see

writing tasks as challenges they are ready to face and their mistakes as learning opportunities that

will further their growth as they come to find who they are as writers.

Future studies should investigate how a growth mindset could influence students’

perceptions of their writing abilities and skills over a longer period of time and with more

reflection and progress–tracking opportunities. Because this study was limited to four weeks, I

GETTING IT WRITE 24

was restricted in how much time I could give the participants to reflect on and discuss their

growth in their writing abilities and skills. I was also limited as to how many activities I could

include and how much time I could use to provide instruction on mindset theory to the

participants. Further research should examine how students’ perceptions might change with

additional instruction over mindset theory and more opportunities to look over their progress.

Additionally, because I found that my students had preconceived notions of what writing is and

who writers are, it would also be worthwhile for future studies to more extensively examine

students’ perceptions of writing and writers. Moreover, additional research should investigate the

ways in which students’ perceptions of writing and writers may be influenced by instruction on

and exposure to various types of writing and writers. Teaching students about different styles of

writing and writers may help broaden their view and impact their perceptions of writing and

writers. With further research and educators who are intentional with their instruction, future

students may begin to more readily recognize their growth and develop their identities as writers.

GETTING IT WRITE 25

References

Altaleb, A. (2021). Using growth mindset strategies in the classroom. Taboo: The

Journal of Culture & Education, 20(2), 207–212.

Barone, T.-A., Sinatra, R., Eschenauer, R., & Brasco, R. (2014). Examining writing

performance and self-perception for low socioeconomic young adolescents. Journal of

Education and Learning, 3(3), 158–171.

https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v3n3p158https://www.iejee.com/index.php/IEJEE/article/view

/76/74

Dweck, C. S. (2010). Even geniuses work hard. Educational Leadership, 68(1), 16–20.

Dweck, C. S. (2015). Growth. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(2), 242–245.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12072

Hales, P. D. (2017). “Your writing, not my writing”: Discourse analysis of student talk about

writing. Cogent Education, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1416897

Hendricks, C. (2017). Improving schools through action research: A reflective practice

approach (4th ed.). Pearson.

Hubbard, R. S., & Power, B. M. (2003). The art of classroom inquiry: A handbook for teacher–

researchers (Rev. ed.). Heinemann.

Jankay, A. (2020). The impact of growth mindset on perseverance in writing. Journal of Teacher

Action Research, 7(1), 60–79.

Miller, L. K. (2020). Can we change their minds? Investigating an embedded tutor’s influence on

students’ mindsets and writing. The Writing Center Journal, 38(1/2), 103–130.

Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). SAGE.

GETTING IT WRITE 26

Seban, D., & Tavsanli, O. F. (2015). Children’s sense of being a writer: Identity construction in

second grade writers workshop. International Electronic Journal of Elementary

Education, 7(2), 217–234. https://www.iejee.com/index.php/IEJEE/article/view/76/74

Tracy, S. J. (2013). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis,

communicating impact. Wiley-Blackwell.

Truax, M. L. (2018). The impact of teacher language and growth mindset feedback on writing

motivation. Literacy Research and Instruction, 57(2), 135–157.

Xu, K. M., Koorn, P., de Koning, B., Skuballa, I. T., Lin, L., Henderikx, M., Marsh, H. W.,

Sweller, J., & Paas, F. (2021). A growth mindset lowers perceived cognitive load and

improves learning: Integrating motivation to cognitive load. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 113(6), 1177–1191. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000631

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2020). What can be learned from growth mindset controversies?

American Psychologist, 75(9), 1269–1284. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000794

GETTING IT WRITE 27

Appendix A

Survey

GETTING IT WRITE 28

Appendix B

Codebook

Level of

Code

Name of Code

Definition of Code

Example of Code

2

Perspectives on Challenges

What participants think, feel, or do

when they are faced with a

challenging task or situation

“once I get done with the

challenging thing I usually get

relieved or satisfied of what I’ve

done and feel good about it”

1

Challenges make you stronger

Participants expressed growing in

perseverance from challenging tasks

or situations

“any hard thing that you go through,

take that as an opportunity to get

better”

1

Challenges help you learn

Participants expressed that people

learn from challenging tasks or

situations or that people do not learn

from easy tasks or situations

“you might not accomplish it the first

time but there's always like you can

fail and try again that’s how you

learn and how you get better at it.”

1

Challenges stress you out

Participants expressed stress,

anxiety, or frustration in response to

a challenging or intimidating task or

situation

“I just like get so frustrated that I just

won’t, don’t wanna do it anymore”

1

You feel proud/accomplished

when you’ve done something

challenging

Participants expressed a sense of

satisfaction in response to

completing a challenging task

“once I get done with the

challenging thing I usually get

relieved or satisfied of what I’ve

done and feel good about it”

1

Response to challenges

Participants expressed a reaction to a

challenging task or situation

“why would I wanna do something

hard that challenges me when I could

just do it easily?”

2

Learning from Mistakes

Participants’ perceptions of

themselves and their abilities when

they mess up and their feelings and

self-perceptions when they struggle

with something

“you can fail and try again that’s how

you learn and how you get better at

it”

1

Learning from past

experiences

Participants expressed the belief that

a person can learn from the past or

discussed a time they learned from

the past

“the older like that I’ve gotten, the

high school experience that I’ve had,

it’s really just showed me that I do

have a growth mindset and it’s okay

to challenge yourself”

GETTING IT WRITE 29

1

Mistakes make you feel bad

Participants expressed a negative

emotion or thought in response to

their own mistakes

“it kinda hurt— like I get like really

frustrated and sometimes I might

break down”

1

Mistakes can be fixed

Participants expressed the belief that

they can resolve or overcome

mistakes they have made

“I realize it’s okay to make mistakes

in life ‘cause you always make

mistakes … I just work harder and

try not to make the same mistake

again”

2

Experiences of Writing at

School

Participants discussed their thoughts,

feelings, and perspectives of writing

and their writing skills

“I barely even still know what a

semicolon exactly is. Like I

understand kinda some of it, but like

I’m never gonna use it ‘cause I don’t

even know how to use it. I just know

basic writing”

1

Writing stresses you out

Participants expressed stress,

anxiety, or frustration in response to

a writing task

“I feel horrible. I, I feel like writing

for me at school goes bad ‘cause I

don’t know what to write”

1

Writing makes you feel free

Participants expressed a sense of

liberty or catharsis when writing

“you feel free ‘cause you can just

write and express like whether you

relate to that or not”

1

Connecting writing to

personal experiences

Participants discussed linking their

writing to their personal lives

“if I can connect with it then I would

say I can do pretty good at it but if I

can’t connect with it then probably

not”

1

Limits to writing at school

Participants described drawbacks to

writing tasks in an academic setting

“you can’t always put everything in

there so it’s a little, I guess, you

don’t get to say everything you

wanna say”

1

What helps a person get better

at writing

Participants discussed things that

have the potential to assist someone

in improving their writing skills

“you just gotta believe in yourself

that you can have the confidence and

be determined to do it”

1

Writing as an outlet/self-

expression

Participants expressed the belief that

writing can act as a release for one’s

thoughts or emotions

“you need to write and you let all of

your feelings out because sometimes

you can’t always talk”

1

Level of confidence in writing

skills

Participants discussed their own

perceptions of their abilities to write

“I’m better than what I was last year”

1

Your mind wanders when

asked to write

Participants expressed an inability to

focus when trying to write in an

“I could be talking to so much girls

right now”

GETTING IT WRITE 30

academic setting

1

Quality of writing prompts

influences writing

Participants expressed the belief that

writing topics or prompts affected

their motivation, desire, or ability to

write

“if you’re gonna put zero effort into a

writing prompt, then don’t expect me

to put my full effort into that”

1

Feelings about writing

Participants expressed their

emotions about writing in general or

their emotions when asked to write

“I just hate writing because it’s

always like, ‘Oh you gotta give like a

really spiritual reasoning for this.’

Like, just give like a basic one and

call it a day”

1

Teachers can ruin/affect

perspective of writing

Participants expressed the belief that

their teacher(s) could influence how

they feel about writing or English

class

“like a single bad coach could ruin

your entire perspective of a sport, so

a single bad teacher can just ruin

your whole perspective of English.

That’s why I don’t do AP classes.

It’s ‘cause sixth grade scarred me for

life”

1

Effects of burnout

Participants discussed the results of

feelings of being overwhelmed or

tired in response to their workload

“maybe if they, I don’t know, didn’t

give us like 54 questions to answer

right before we write like a one-page

essay about and it has to be like

perfect or something ‘cause you

know. Maybe I’d feel more

motivated”

2

The Writer Identity

Participants’ thoughts on what

writers are and do, what good

writing is and looks like, and their

perspectives on themselves as

writers

“you have to be, like, determined to

do it. Like you have, you have a clear

mind and a good mindset to be a

good writer”

1

What makes a good writer

Participants described characteristics

or skills that they believe good

writers must possess

“you have to be, like, determined to

do it. Like you have, you have a clear

mind and a good mindset to be a

good writer”

1

Handwriting influences your

writing

Participants expressed the belief that

what their handwriting looks like

influences the quality of their

writing

“I don’t know what the teacher’s

gonna think about my handwriting”

1

Some people are born with a

natural “gift” to write

Students discussed the idea that

people who are good at writing were

“some people are just naturally gifted

with that stuff”

GETTING IT WRITE 31

born with a heightened ability to

write well

1

Identity as a writer

Students discussed their level of

identification with the writer identity

“I think I’m a decent writer”

2

Discussions on Growth

Mindset

Participants explicitly discussed

growth mindset or mindset theory or

participants exhibited behavior that

aligned with growth mindset

“I’m more coming to have a growth

mindset”

1

Use of growth mindset aligned

feedback

I provided participants with

feedback that agreed with growth

mindset

“I talked with him about the

improvements he was making and

the fact that he had been facing the

challenge of improving his grade by

changing his behavior in class and

his attitude toward doing classwork”

1

Possible effects of growth

mindset

Participants exhibited behavior that

aligned with growth mindset

“I’ve been kind of scared to like

challenge myself with it, and so I,

like, I’m getting there to where I can

do it and I’m not scared to do it”

1

Thoughts on mindset theory

Participants discussed their

perspectives on mindset theory and

growth mindset

“the more like you have like the

growth mindset, the better you are in

life … because you’re open to

growing … you're open to doing

anything that’s challenging … it’ll

just keep you as a open, honest

person”

1

Ways to use growth mindset

in daily life

Participants discussed areas of their

daily lives to which they could apply

a growth mindset

“my math it’s always been hard at

first and now I, the more I do it the

more easier it gets”

GETTING IT WRITE 32

Appendix C

Responses to Question One: I Can Write Well

GETTING IT WRITE 33

Appendix D

Responses to Question Two: I Am a Good Writer

GETTING IT WRITE 34

Appendix E

Responses to Question Three: People are Born with the Ability to Write Well

GETTING IT WRITE 35

Appendix F

Responses to Question Four: I Have the Ability to Get Better at Writing

GETTING IT WRITE 36

Appendix G

Responses to Question Five: My Writing Skills Cannot Change