REPUBLIC OF RWANDA

MINISTRY OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY

Entrepreneurship Development Policy

Developing an effective entrepreneurship and MSME ecosystem in Rwanda

April 2020

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

iii

FOREWORD

In the last decade, entrepreneurship has become one of

key components of economic and business development

policies. Its relevance has increased as entrepreneurs

are associated with the ability to create new products,

new services and to innovate. There is a large growing

body of research that shows the interrelation

and interdependence between entrepreneurship,

innovation and economic development. Today, women

and men entrepreneurs have a prominent role in

driving innovation, economic growth, welfare, as well

as a notable impact on job creation. Entrepreneurs are

frequently thought of as national assets to be cultivated,

motivated, and remunerated to the greatest possible

extent. Great entrepreneurs have the ability to change

the way we live and work. If successful, their innovations

improve standards of living, create wealth and contribute

largely to a growing economy. In line with Rwanda’s

vision to become an upper middle-income country by

the year 2035 and to reach high-income status by 2050,

there is no doubt that entrepreneurship will be one

of the key drivers in reducing poverty, promoting social change, fostering innovation and economic

transformation.

Rwanda’s Entrepreneurship Development Policy (EDP) intends therefore to provide an overarching

ecosystem to support entrepreneurs with a conducive environment for private sector dynamism,

innovation and risk-taking required for a modern, sophisticated, and rapidly growing economy. It

builds on the existing policies and reforms undertaken by the Government and holistically seeks

to address the gaps within Rwanda’s entrepreneurship ecosystem. While important government

policies promote private sector development more broadly in various sectors, the EDP reinforces,

and complements the existing policies and strategies towards achieving increased entrepreneurship,

business growth, and job creation in Rwanda.

In designing this policy, extensive stakeholder consultations were conducted with central and local

governments in all provinces, entrepreneurs from start-ups and Micro, Small, Medium and Large

Enterprises, the Private Sector Federation (PSF), Financial Institutions, local and international investors,

business consultants, academia, incubators, accelerators, and Development Partners.

The Government of Rwanda, through the Ministry of Trade and Industry, wishes to commend the US

Government for the constant support in the development of the EDP, via its USAID Rwanda Nguriza

Nshore Project.

I thank all listed stakeholders for their valuable contribution, which led to the development of this

outstanding and timely policy document. I look forward to a continuous and efcient collaboration

and support to successfully implement the Entrepreneurship Development Policy.

Hon. Soraya M. HAKUZIYAREMYE

Minister of Trade and Industry

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

iv

CONTENTS

FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................................................III

TABLES AND FIGURES .....................................................................................................................................VI

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................VII

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................IX

1. GENERAL INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................1

1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................................................1

1.2 Rationale for Change from SME Development Policy to Entrepreneurship Development Policy 3

1.3 Relationship between EDP and Regional and Global Strategies and Goals ....................................4

EDP and SDGs .........................................................................................................................................4

EDP and AU Agenda 2063 .....................................................................................................................5

EDP and EAC Vision 2050 .....................................................................................................................5

1.4 Relationship between EDP and other existing national policies and strategies ............................. 6

2. EDP DEVELOPMENT PROCESS .................................................................................. 8

2.1 Definitions ......................................................................................................................................................8

Entrepreneurship .....................................................................................................................................8

Firm Size Definitions ..............................................................................................................................8

High-Growth Entrepreneurship ........................................................................................................... 9

2.2 International Benchmarks...........................................................................................................................9

Singapore ................................................................................................................................................... 9

Israel ...........................................................................................................................................................10

Chile ...........................................................................................................................................................11

2.3 Development Process and Stakeholder Consultations .......................................................................11

3. VISION AND OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................13

3.1 Vision ...............................................................................................................................................................13

3.2 Policy Framework ........................................................................................................................................13

3.3 Policy Objectives ..........................................................................................................................................14

4. ANALYSIS: CONSTRAINTS TO ENTREPRENEURSHIP ..........................................15

4.1 Pillar 1: Human Capital and Management ...............................................................................................15

4.2 Pillar 2: Business Support ............................................................................................................................16

4.3 Pillar 3: Financing ..........................................................................................................................................17

4.4 Pillar 4: Business Enabling Environment ...................................................................................................18

4.5 Pillar 5: Markets and Value Chains ............................................................................................................18

4.6 Pillar 6: Technology and Infrastructure.....................................................................................................19

4.7 Pillar 7: Entrepreneurial Culture ...............................................................................................................20

5. POLICY ACTIONS ..........................................................................................................21

5.1 Policy Design Process ..................................................................................................................................21

5.2 Key Crosscutting Instruments ................................................................................................................... 21

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

v

5.3 Feasibility and Impact of Policy Actions ...................................................................................................22

5.4 Pillar 1: Human Capital and Management ...............................................................................................23

5.5 Pillar 2: Business Support ............................................................................................................................25

5.6 Pillar 3: Financing ..........................................................................................................................................27

5.7 Pillar 4: Business Enabling Environment ...................................................................................................29

5.8 Pillar 5: Markets and Value Chains ............................................................................................................29

5.9 Pillar 6: Technology and Infrastructure ...................................................................................................31

5.10 Pillar 7: Entrepreneurial Culture .............................................................................................................31

6. IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ............................................................................................33

6.1 Current Institutional Framework .............................................................................................................33

6.2 EDP Implementation Framework .............................................................................................................33

6.3 EDP Institutional Framework ....................................................................................................................34

6.4 EDP Impact Monitoring and Evaluation ..................................................................................................35

6.5 Financial Implications ................................................................................................................................... 35

6.6 Legal and Regulatory Implications ............................................................................................................36

6.7 Implementation Matrix ...............................................................................................................................36

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

vi

TABLES AND FIGURES

Figure1: Existing Rwandan Entrepreneurship Ecosystem 1

Figure 2: Relationship between EDP and SME Development Policy 3

Figure 3: The EDP is Central to the National Policies and Strategies in Rwanda 6

Figure 4: The EDP Development Process 12

Figure 5: The Seven Pillars of the EDP 13

Figure 6: Policy Design Decision Tree 21

Figure 7: Feasibility and Impact of Policy Actions 23

Figure 8: EDP Institutional Framework 34

Table 1: Visions of the SME Development Policy and the New EDP ...................................................... 3

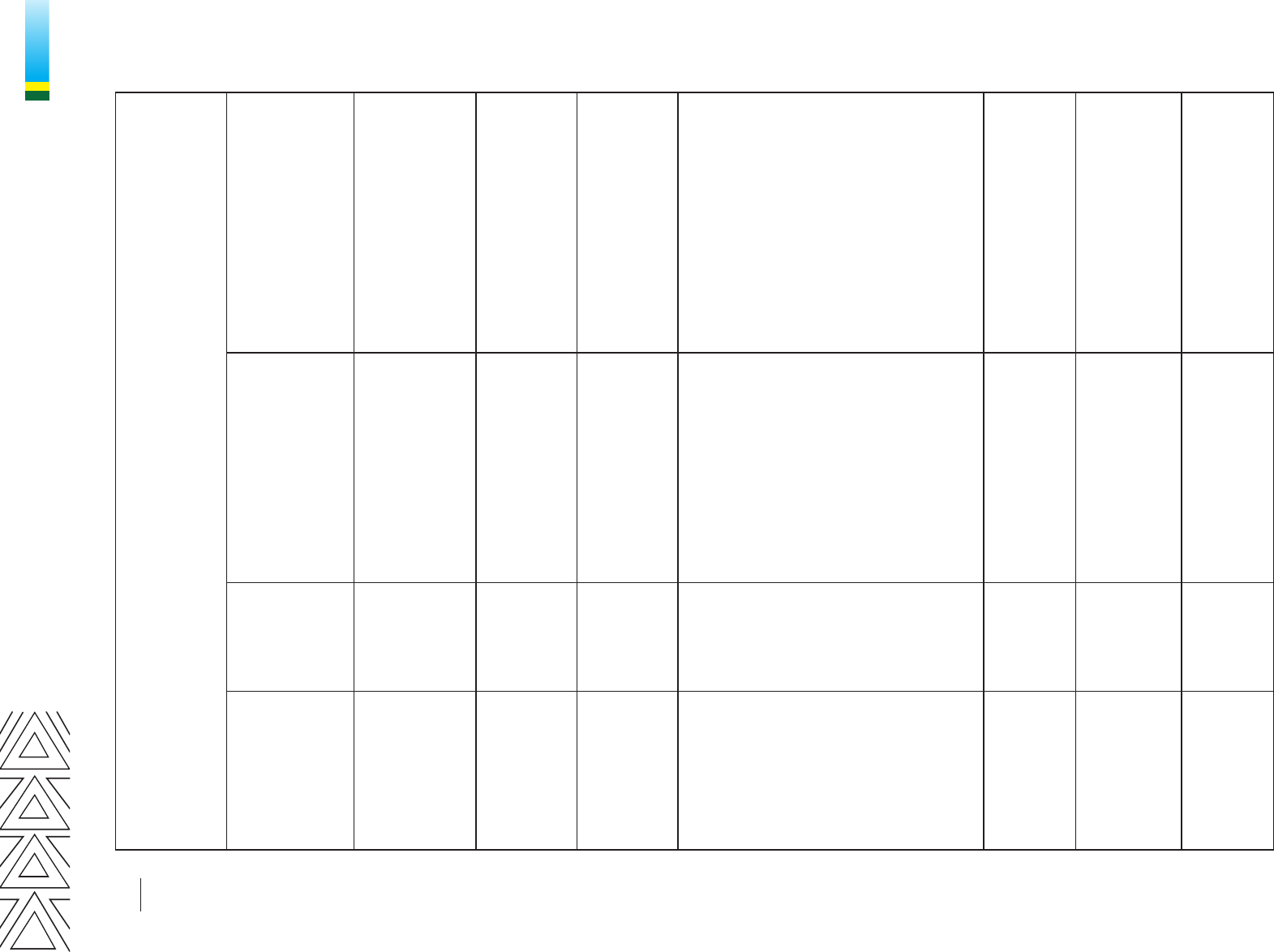

Table 2: Firm Size Denitions .......................................................................................................................... 9

Table 3: EDP Estimated Cost ........................................................................................................................... 36

Table 4: Summarized EDP Implementation Matrix ..................................................................................... 37

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF TABLES

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

vii

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

Agri-tech Agricultural Technology

AIMS African Institute for Mathematical Sciences

ALU African Leadership University

AU African Union Commission B2B business-to-business

BDA Business Development Advisor

BDF Business Development Fund

BDS Business Development Services

BNR National Bank of Rwanda

BRD Development Bank of Rwanda

COMESA Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa

CORFO Corporación de Fomento de la Producción de Chile

DGIE Directorate-General of Immigration and Emigration

EAC East African Community

EDP Entrepreneurship Development Policy

EICV5 Fifth Integrated Household Living Conditions Survey 2016–2017

fintech financial technology

GEDI Global Entrepreneurship Development Index

GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor

GOR Government of Rwanda

HEC Higher Education Council

HI/HF Higher Impact/Higher Feasibility

HI/LF Higher Impact/Lower Feasibility

HIL Higher Learning Institution

ICT Information and Communications Technology

IP Intellectual Property

KIC Kigali Innovation City

LI/HF Lower Impact/Higher Feasibility

LI/LF Lower Impact/Lower Feasibility

LODA Local Administrative Entities Development Agency

LT Long Term

M&E Monitoring and Evaluation

MIGEPROF Ministry of Gender and Family Promotion

MINAFFET Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation

MINAGRI Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources

MINALOC Ministry of Local Government

MINECOFIN Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning

MINEDUC Ministry of Education

MINICOM Ministry of Trade and Industry

MINICT Ministry of Technology and Innovation

MININFRA Ministry of Infrastructure

MINISPORTS Ministry of Sports

MYCULTURE Ministry of Youth and Culture

MOOC Massive Open Online Course

MSME Micro, Small, and Medium-sized Enterprise

MT Medium Term

NAEB National Agricultural Export Development Board

NCPD National Council of Persons with Disabilities

NIRDA National Industrial Research and Development Agency

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

viii

NISR National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda

NST1 National Strategy for Transformation

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

PSDYE Private Sector Development and Youth Employment Strategy

PSF Private Sector Federation

R&D Research and Development RAB Rwanda Agriculture Board

RBA Rwanda Bankers Association

RCA Rwanda Cooperative Agency

RDB Rwanda Development Board

REB Rwanda Education Board

REG Rwanda Energy Group

RGB Rwanda Governance Board

RISA Rwanda Information Society Authority

RP Rwanda Polytechnic

RPPA Rwanda Public Procurement Authority

RRA Rwanda Revenue Authority

RSB Rwanda Standards Board

RSE Rwanda Stock Exchange

RWF Rwandan Franc

SACCO Savings and Credit Cooperative Organization

SDG Sustainable Development Goal

SME Small and Medium-sized Enterprise

SPRING Standards, Productivity, and Innovation Board

ST Short Term

STEM science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

SUP Start-Up Chile

SWG Sector Working Group

SWOT Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats

USAID U.S. Agency for International Development

WDA Workforce Development Authority

YCA YouthConnekt Africa

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

ix

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Support to entrepreneurship—creating conditions for growth of vibrant and competitive

enterprises across all sectors of the economy—is a critical element in achieving the

Government of Rwanda’s (GOR) ambitious growth and competitiveness objectives as

laid out in the Vision 2050 document, which sets a target of achieving an upper-middle-income status

by 2035 and a high-income status by 2050. The National Strategy for Transformation (NST1), the

Government’s seven-year implementation program for 2017–2024, prioritizes inclusive economic

growth, job creation, and private sector-led development in a variety of growth sectors, including

diversified tourism, local manufacturing, productive agriculture and agro-processing, and knowledge-

based services and information and communications technology (ICT). Dynamic and competitive

private enterprises of all sizes and strong ecosystems for entrepreneurship are critical for private

sector-led development as a foundation of economic growth, job creation, poverty alleviation and

increased prosperity.

The Entrepreneurship Development Policy (EDP) supports private sector entrepreneurs

and provides the necessary environment for private sector dynamism, innovation,

and risk taking required for a modern, sophisticated, and rapidly growing economy.

The government has built a strong track record of reforms to support the development of viable

enterprises. The EDP builds on the existing policies and reforms undertaken by the government

and holistically seeks to address the gaps within Rwanda’s entrepreneurship ecosystem. While these

important GOR policies promote private sector development more broadly in each of their respective

domains, the EDP actions reinforce, support implementation, and complement the existing policies

and strategies toward achieving increased entrepreneurship, business growth, and job creation in

Rwanda.

The EDP is closely aligned with all key GOR policies and strategies across all line ministries

that promote private sector development and economic growth through social transformation—

the Vision 2050, NST1, Private Sector Development and Youth Employment Strategy

(PSDYE), and Made in Rwanda Policy. The EDP also underpins Rwanda’s goals and commitments

as part of key regional and international development agendas, including the Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs), African Union Commission (AU) Agenda 2063, and the

East African Community (EAC) Vision 2050.

The EDP replaces and builds on the achievements of the 2010 Small and Medium-

Sized Enterprise (SME) Development Policy, which focused only on SMEs. The EDP

supports entrepreneurship, innovation, and enterprise growth at all stages of the enterprise growth

lifecycle, from start-ups to existing micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) and large

enterprises. Although substantial successes have been registered by the SME Development Policy, it

fell short of creating an enabling environment necessary to support entrepreneurship and innovation

among MSMEs. Thus, the EDP’s focus is on strengthening the entrepreneurship ecosystem as an

enabler to enterprise creation and growth.

A focused, coherent entrepreneurship policy and an integrated approach are necessary

to create an enabling environment for the success of entrepreneurship and innovation

among start-ups, MSMEs, and large enterprises. This will require a concerted effort to

develop human capacity at the national and local levels, as well as provide adequate resources

to support implementation of the policy actions. This policy aims to address these macro-level

structural challenges, which have characterized government interventions thus far, while also taking

into account the development goals of the GOR, specifically to increase value-added processing to

reduce the trade deficit and rise out of poverty, and to address challenges articulated by enterprises

on the ground.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

x

The EDP’s vision is to develop an effective entrepreneurship support ecosystem that

creates the necessary conditions and enablers for Rwandan entrepreneurs to unleash

their entrepreneurial potential and to grow dynamic and competitive enterprises that will drive

economic growth and job creation. The EDP uses a seven-pillar framework that focuses on key

pillars of the entrepreneurship ecosystem: human capital and management, business support,

financing, business enabling environment, markets and value chains, technology and

infrastructure, and entrepreneurial culture.

The comprehensive objective of the EDP is to ensure that all seven pillars of the

entrepreneurship ecosystem function properly, allowing Rwandan start-ups, MSMEs,

and large enterprises to grow sustainably and profitably. EDP actions address constraints

identified under each of the seven pillars to achieve the following objectives:

1. Improve access to skills and know-how for existing and potential entrepreneurs to effectively

start and manage a business;

2. Improve business support system for entrepreneurs, including business consultants, mentors,

incubators, and accelerators;

3. Improve entrepreneurs’ ability to access the finance required for business growth from various

sources, including equity, debt, and grants from public, private, and peer-to-peer sources.;

4. Streamline tax regimes that are supportive to entrepreneurship development;

5. Expand access to domestic and export market opportunities for entrepreneurs;

6. Improve entrepreneurs’ access to technologies and innovations for business growth and

productivity;

7. Promote the culture of entrepreneurship and equitable access to business opportunities for all

entrepreneurs.

The EDP has been informed by best practices from leading countries in the developed

and developing world that have put in place targeted and effective entrepreneurship

development policies which have been evaluated and have contributed to their successful

economic transformation and created robust ecosystems for entrepreneurship support. Three

countries—Singapore, Israel and Chile—stand out for their path to entrepreneurship as models for

consideration for Rwanda.

To identify the key constraints to entrepreneurship in Rwanda and develop EDP actions, extensive

stakeholder interviews were conducted, including central and local governments in all provinces and

20 districts as a representative sample, entrepreneurs from start-ups and MSMEs, representatives

from the Private Sector Federation (PSF), banks, local and international investors, business consultants,

academia, incubators, accelerators, and donors. The EDP also draws extensively on the review of

prior research and assessment of Rwanda’s priorities under the NST1, PSDYE, and other relevant

GOR policies and strategies.

Proposed policy actions cover each of the EDP seven pillars. They first capitalize on

existing initiatives in place in Rwanda. When no ongoing initiative is in place, policy actions

draw on relevant international best practices and evidence adapted to the Rwandan

context. Finally, when best-fit solutions cannot be found domestically or internationally, the EDP

pilots innovative solutions, which will be tested at a small scale, refined based on lessons learned,

and launched at scale when and if ready.

• Pillar 1: Human capital and management focuses on improving access to skills and

know-how that are necessary to effectively start and run a business. Policy actions focus

on improving the marketability of tertiary academic programs, strengthening applied skills

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

xi

in secondary school entrepreneurship curriculum, improving the access to and quality of

English language instruction, improving availability of technical skills training outside of formal

education, improving business governance, and strengthening service delivery across all

sectors.

• Pillar 2: Business support focuses on improving business support system for entrepreneurs

through access to tailored business consulting services, improving the availability of high-

quality business consultants, supporting development of mentorship networks, piloting new

models of provincial business incubators, supporting development of the Kigali Innovation

City (KIC), and strengthening linkages with international business support institutions.

• Pillar 3: Financing improves entrepreneurs’ ability to access finance for business growth

from various sources, including equity, debt, and grants from public, private, and peer-to-

peer sources. Policy actions increase entrepreneurs’ awareness of information on financial

products, improve the effectiveness of the Business Development Fund (BDF), help financial

institutions develop industry-specific financial products, promote learning and exchange of

best practices in financing, build a private capital investor culture, create a start-up matching

fund and a fellowship fund for entrepreneurs, promote crowdfunding, and support the already

existing initiative to list MSMEs on the Rwanda Stock Exchange (RSE).

• Pillar 4: Business enabling environment aims to streamline tax requirements for new

firms to decrease business costs for new entrepreneurs. Proposed policy actions include

reviewing and modifying tax requirements for start-ups and MSMEs, increasing awareness

for entrepreneurs about the benefits of formality, and increasing the awareness of tax

requirements.

• Pillar 5: Markets and value chains focuses on expanding access to domestic and export

market opportunities for entrepreneurs via improving cross-border trade; improving

warehousing systems; making government procurement opportunities more accessible to

newer, smaller companies; improving access to market information; facilitating adoption of

standards; and updating the SME Cluster Strategy.

• Pillar 6: Technology and infrastructure improves entrepreneur access to technologies

and innovations required for business growth and productivity via promoting reliable power

solutions, increasing coordination between entrepreneurship clusters and government

infrastructure planning, promoting private sector-driven supply of improved agricultural

technologies, and improving digital literacy.

• Pillar 7: Entrepreneurial culture promotes the culture of entrepreneurship and access

to business opportunities for entrepreneurs, including youth, women, and people living with

disabilities via promoting exchanges to encourage entrepreneurial culture and ensuring equal

opportunities and support for all entrepreneurs.

The EDP will be implemented using existing institutional frameworks. The Ministry

of Trade and Industry (MINICOM), Rwanda Development Board (RDB), Ministry of

Education (MINEDUC), Ministry of Youth (MYCULTURE), Ministry of Finance and

Economic Planning (MINECOFIN), Ministry of Local Government (MINALOC), and

PSF are the key leading institutions implementing the seven pillars of the EDP. MINICOM,

as the overall policy lead, will play the role of coordinator and high-level policy supervisor. The

institutional framework that supports implementation of the policy and the monitoring and evaluation

(M&E) structure allow for a dynamic and responsive policy, which will enable its continuous updating

and upgrading to reflect changes in the operating environment and incorporate lessons learned

during implementation.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

1

1. GENERAL INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

The business environment reforms that propelled Rwanda in the World Bank’s Doing Business rankings

from 62

nd

in 2016 to 29

th

in the world in 2019, coupled with private sector development-focused

government policies and strategies, and financing instruments have helped foster entrepreneurial

activity. This can be observed in both traditional sectors, such as agriculture and tourism, and in new

technology-oriented sectors, such as ICT.

Figure1: Existing Rwandan Entrepreneurship Ecosystem

The state of entrepreneurship in Rwanda has been improving, most notably in recent years. Most

companies in Rwanda are young and micro. In 2014, 90 percent of operating firms were still young,

having been established after 2006.

1

In 2011, 73 percent of all firms were micro-enterprises; in 2014

this number decreased to 65 percent.

2

While the share of micro-enterprises is still high, this decline

reflects an important growth in the number of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as compared

to micro businesses. Moreover, between 2011 and 2017, the number of large firms with more than

100 employees more than quadrupled from 106 to 426, representing the maturing of the Rwandan

market and increased opportunities for value chain integration for MSMEs.

3

Rwandan companies are

concentrated in the non-tradable sector. According to the 2017 Establishment Census, wholesale

and retail trade, and accommodation and food services accounted for 77.8 percent of all firms. In

2018, the employment-to-population ratio was 46.0 percent; 2 percentage points higher than the one

in 2017, which stood at 44.2 percent.

4

1 World Bank. (2019). Future Drivers of Growth. Calculations are based on statistics from the Rwanda Census of Business Establishment (National

Institute of Statistics of Rwanda [NISR], 2011 and 2015).

2 Ibid.

3 Establishment Census 2011; Establishment Census 2017.

4 Labour Force Survey Report. (December 2018).

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

2

In 2018, agriculture accounted for 55 percent of employment.

1

Additionally, 71 percent of MSMEs are

rural (outside of Kigali). At the same time, informality remains a challenge; about 90 percent of firms

are estimated to be informal and more than 60 percent of employment occurs informally.

2

Rwanda has also witnessed the birth of several important entrepreneurship ecosystem enablers,

such as business incubators and accelerators, which provide valuable support to start-ups. These

incubators and accelerators are establishing themselves as platforms to help start-ups launch and

grow, hosting cohorts of entrepreneurs ready to start and scale their businesses. These incubators

and accelerators are becoming magnets for other key enablers such as business service providers

(e.g.: accountants and business consultants); mentors and coaches; and, to a lesser extent, early

stage investors, such as business angels. However, while small grants are often made available to

entrepreneurs in partnerships between incubators and international donors, equity funding remains

scarce and most start-ups cannot afford bank loans, making access to finance one of the key constraints

to entrepreneurship.

Another positive development is the growing number of high-level academic institutions entering

and expanding in Rwanda. The presence of universities, such as Carnegie Mellon University, African

Leadership University (ALU), and African Institute for Mathematical Sciences (AIMS), is increasing the

quality of tertiary education, especially in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM)

subjects and business management. This is contributing to the overall improvement in the quality of

human capital and workforce. In addition, the GOR’s investment in introducing new entrepreneurship

curricula in secondary schools is building a foundation for training future entrepreneurs. To fully

capitalize on this potential, there is an opportunity to better connect these educational institutions

to relevant industries and create mechanisms to stimulate students to become entrepreneurs.

Rwanda has been working on ambitious cluster-like initiatives, most notably the KIC, which aims

to become a hotbed for technology start-ups, MSMEs, and large enterprises in biomedical, financial

technology (fintech), smart energy, and cyber security. This initiative, which connects incubators,

academic institutions, funding (via the Innovation Fund), and a network of support, has the potential

to take high-tech entrepreneurship in Rwanda to the next level, similar to what initiatives such as

Start-Up Chile (SUP) have accomplished. Rwanda possesses an untapped potential for becoming

one of Africa’s research and development (R&D) and innovation hubs with developing infrastructure,

growing market, conducive business environment, stable political situation, fast-growing economy,

increasing number of prestigious academic institutions, and a central location within Africa.

Nevertheless, entrepreneurs still face several challenges to turn their ideas into sustainable high-

growth businesses that would propel Rwanda toward its vision for growth outlined in the NST1,

Vision 2020, and Vision 2050. Access to knowledge and latest technologies is still restricted. Sound

management practices and entrepreneurship training are not yet commonplace. Business support

services are often not specialized enough to help entrepreneurs get to the next level. Access to

finance, especially early equity investment, is highly limited. Cultural aspects, such as risk-aversion

and a preference for a steady job over an entrepreneurial “adventure,” keep some of the brightest

Rwandan minds from taking the start-up leap. In the Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018, Rwanda

scored the lowest in risk capital, risk acceptance, process innovation, start-up skills, human capital,

and technology absorption.

3

Business informality, estimated to be as high as 93 percent by the Fifth Integrated Household Living

Conditions Survey 2016–2017 (EICV5), is another challenge. Unregistered companies operate

illegally, representing a risk to themselves, suppliers, and clients, and do not contribute in taxes, while

being unable to enjoy government benefits. The major cause of informality is the perceived high cost

associated with formality by entrepreneurs. To increase business formalization, the EDP adopts an

organic approach, where companies are nudged to become formal as some of the main perceived

1 Ibid.

2 World Bank. (2019). Future Drivers of Growth. Calculations are based on statistics from the Rwanda Census of Business Establishment. (NISR, 2011

and 2015).

3 Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

3

costs associated with formality, such as taxes and compliance with standards, are eased and applied

in a gradual manner according to international best practices, minimizing burdens for both start-

ups and MSMEs. At the same time, the increased awareness of market opportunities and available

support programs for entrepreneurs as a result of EDP actions will motivate informal entrepreneurs

to formalize to be able to take advantage of existing business opportunities.

The EDP recognizes the achievements made so far and includes policy actions necessary to remove

the remaining obstacles to entrepreneurship and bolster Rwanda’s entrepreneurship ecosystem.

1.2 Rationale for Change from SME Development Policy to Entrepreneurship

Development Policy

To achieve Rwanda’s economic development objectives, both new and existing enterprises of all sizes

need to grow. The EDP replaces and builds on the achievements of the 2010 SME Development Policy,

which focused on only SMEs. Thus, the EDP supports entrepreneurship, innovation, and enterprise

growth and graduation at all stages of the enterprise growth lifecycle, from start-ups to existing

MSMEs and large enterprises.

Table 1: Visions of the SME Development Policy and the New EDP

Different

Policy

Visions

SME Development Policy Entrepreneurship Development Policy

“To create a critical mass of viable and

dynamic SMEs signicantly contributing to

the national economic transformation.”

“To develop an effective entrepreneurship support ecosystem that creates the

necessary conditions and enablers for Rwandan start-ups, MSMEs, and large

enterprises to unleash their entrepreneurial potential and grow dynamic and

competitive enterprises that will drive economic growth and job creation.”

The

focus

here is

on small enterprises and

their

contribution to economic transformation.

The focus here is more on strengthening the entrepreneurship ecosystem as an

enabler to enterprise creation and growth.

Figure 2 displays how the two policies are related, with the EDP’s vision covering the larger

entrepreneurship ecosystem, and with SMEs included in the umbrella of the EDP.

Figure 2: Relationship between EDP and SME Development Policy

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

4

Although substantial successes have been registered by the SME Development Policy, it fell short

of creating an enabling environment necessary to support entrepreneurship and innovation among

MSMEs. Key challenges still include:

1. Limited access to skills and know-how for existing and potential entrepreneurs that are necessary

to effectively start and run a business;

2. Limited business support system for entrepreneurs, including business consultants, mentors,

incubators, and accelerators;

3. Limited entrepreneurial ability to access the finance required for business growth from various

sources, including equity, debt, and grants from public, private, and peer-to-peer sources;

4. Non-streamlined tax requirements for newly established firms that increase business costs for

new entrepreneurs;

5. Limited access to domestic and export market opportunities for entrepreneurs;

6. Limited entrepreneurial access to technologies and innovations required for business growth and

productivity;

7. Negative culture of entrepreneurship and limited access to business opportunities for women

entrepreneurs.

From these challenges, it is clear that a focused, coherent entrepreneurship policy and an integrated

approach are necessary to create an enabling environment for the success of entrepreneurship

and innovation among start-ups, MSMEs, and large enterprises. This will require a concerted effort

to develop human capacity at the national and local levels, as well as provide adequate resources

to support implementation of the policy actions. This policy aims to address these macro-level

structural challenges, which have characterized government interventions thus far, while also taking

into account the development goals of the GOR, specifically to increase value-added processing to

reduce the trade deficit and rise out of poverty, and to address challenges articulated by enterprises

on the ground.

1.3 Relationship between EDP and Regional and Global Strategies and Goals

The EDP underpins Rwanda’s goals and commitments as part of key regional and international

development agendas, including the SDGs, the AU Agenda 2063, and the EAC Vision 2050. Creating

environment for growth of vibrant and competitive private enterprises, entrepreneurship, and

innovation is a critical element to achieving regional and global growth and development objectives.

EDP and SDGs

Dynamic and competitive private enterprises of all sizes and strong ecosystems for entrepreneurship

are critical for achievement of all SDGs since private sector-led development is a foundation of

economic growth, job creation, poverty alleviation, and increased prosperity. Entrepreneurs around

the world drive innovation and development of solutions to the most intractable development

problems and have a key role to play in advancing each of the 17 SDGs, with EDP contributing most

directly and immediately to the following SDGs:

• Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere.

• Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition and promote sustainable

agriculture.

• Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning

opportunities for all.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

5

• Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.

• Goal 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.

• Goal 7: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all.

• Goal 8: Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment,

and decent work for all.

• Goal 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and

foster innovation.

• Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries.

EDP and AU Agenda 2063

The AU Agenda 2063 sets out a framework for “an integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa, driven

by its own citizens and representing a dynamic force in the international arena.” The first 10-year

Implementation Plan of the Agenda (2014–2023) includes seven Priorities (“Aspirations”) and 20

Goals. Successful implementation of the EDP will directly contribute to the achievement of the

following goals:

• Goal 1: A high standard of living, qualify of life, and well-being for all citizens.

• Goal 2: Well-educated citizens and skills revolution underpinned by science, technology, and

innovation.

• Goal 4: Transformed economies.

• Goal 5: Modern agriculture for increased productivity and production.

• Goal 7: Environmentally sustainable and climate-resilient economies and communities.

• Goal 17: Full gender equality in all spheres of life.

• Goal 18: Engaged and powerful youth.

EDP and EAC Vision 2050

The EAC Vision 2050 sets out six shared development goals for the East Africa region. EDP directly

contributes to achievement of the following EAC goals:

• Goal 2: Enhanced agricultural productivity for food security and a transformed rural economy.

• Goal 3: Structural transformation of the industrial and manufacturing sector through value

addition and product diversification based on comparative advantage for regional competitive

advantage.

• Goal 4: Effective and sustainable use of natural resources with enhanced value addition and

management.

• Goal 5: Leverage on the tourism and services value chain and building on the homogeneity

of regional cultures and linkages.

• Goal 6: Well-educated and healthy human resources.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

6

1.4 Relationship between EDP and other existing national policies and strategies

The GOR has adopted an ambitious growth and competitiveness strategy. Vision 2050 sets a target

of achieving upper-middle-income status by 2035 and high-income status by 2050. The NST1, the

government’s seven-year implementation program for 2017–2024, prioritizes inclusive economic

growth, job creation, and private sector-led development in a variety of growth sectors, including

diversified tourism, local manufacturing, productive agriculture and agro-processing, and knowledge-

based services and ICT. Support to entrepreneurship — creating conditions for growth of vibrant

and competitive enterprises across all sectors of the economy — is a critical element to achieving

these growth objectives.

The EDP is closely aligned with all key GOR policies and strategies across all line ministries, and

is grounded in Rwanda’s strategic orientation articulated in NSTI. Particularly, it supports NST1

priorities of empowering youth and women entrepreneurship, improving access to finance for

entrepreneurs, developing skills, supporting innovation and technology firms, improving industry

networks and business support services, developing competitive value chains and services sectors,

reducing the cost of doing business and facilitating trade, increasing productivity in agriculture, and

increasing entrepreneurial motivation and risk taking, among others.

Figure 3: The EDP is Central to the National Policies and Strategies in Rwanda

As illustrated in Figure 3, EDP complements and is interconnected with other GOR policies,

strategies, and official documents that promote private sector development and economic growth

through social transformation. These policies and strategies include:

• Vision 2050: Rwanda aspires to increase the incomes and well-being of all Rwandan citizens,

because prosperity is a key element to quality life. Additionally, Rwanda’s aspirations are

translated in becoming an upper-middle-income country by 2035 and a high-income country

by 2050.

• NST1: The NST1 prioritizes inclusive economic growth and social development with the

private sector at the helm. The NST1 calls for strategic interventions for the development

of a specific policy on entrepreneurship development to create a conducive ecosystem for

growth of vibrant and competitive enterprises across all sectors of the economy.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

7

• PSDYE: The PSDYE strategy recognized that the existing ecosystem for entrepreneurship

development must be nurtured and encouraged to flourish.

• Made in Rwanda Policy: To increase the competitiveness of the Rwandan economy, the

Made in Rwanda Policy recognizes the need for a conducive business environment for

entrepreneurship development and realization of national employment programs in general.

The government has built a strong track record of reforms to support the development of viable

enterprises. EDP builds on the above mentioned policies and the already existing reforms undertaken

by the government. While these important GOR policies promote private sector development more

broadly in each of their respective domains, the EDP actions reinforce, support the implementation of,

and complement these existing policies and strategies toward achieving increased entrepreneurship,

business growth, and job creation in Rwanda.

This policy supports private sector entrepreneurs and provides the dynamism, innovation, and

risk taking required for a modern, sophisticated, and rapidly growing economy. The EDP holistically

seeks to address the existing gaps within Rwanda’s entrepreneurship ecosystem.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

8

2. EDP DEVELOPMENT PROCESS

2.1 Definitions

Entrepreneurship

EDP uses a broader definition of entrepreneurship than just start-ups, where the term

“entrepreneurship” also captures innovation on the part of established firms, in addition to similar

activities on the part of new businesses:

Entrepreneurship is “capacity and willingness to develop, organize, and manage a business venture

along with any of its risks in order to make a profit.”

1

An entrepreneur is an individual who,

rather than working as an employee, “organizes, manages, and assumes the risks of a business or

enterprise.”

2

The entrepreneur is commonly seen as an innovator, a source of new ideas, goods,

services, and businesses/or procedures.

Firm Size Definitions

There is no uniform international definition for MSMEs, large enterprises, and start-ups. Definitions

for enterprise size vary from country to country and context to context, both in terms of indicators

and benchmarks. In most instances, two indicators—revenue and number of employees—are used

to define enterprises. However, in certain cases, for example, if the goal is comparing firms in the

context of global trade and finance, companies may also be categorized according to exports or

investments. Even within the most commonly accepted indicators—sales and employment—what is

small in a large economy, like the United States or Germany, might be considered medium in a smaller

economy, like Jamaica or Uganda. The term “start-up,” however, has enjoyed more consensus and,

although no unique definition has been globally adopted, it is most used to refer to newly started

(usually less than three years in existence), innovative, high-growth potential ventures.

3

The choice of “number of employees” and “annual sales” as key references for company size is

particularly fitting for developing countries with a strong rural base, like Rwanda, since indicators such

as investments and exports often do not apply to micro and small rural businesses and, moreover,

data on investments and exports are more difficult to collect. EDP uses the following definitions

based on extensive conversations with stakeholders in Rwanda and research on definitions used

by global institutions such as the World Bank and Organization for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD),

4

private organizations such as the FSE Group,

5

national initiatives such as

Enterprise Ireland,

6

as well as previous definitions used in Rwanda, for example, in its 2010 SME

Development Policy.

1 Retrieved from http://www.businessdictionary.com/denition/entrepreneurshiphtml.

2 Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/entrepreneur.

3 See for example: https://www.startups.co/articles/what-is-a-startup-company.

4 Retrieved from https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=3123.

5 Retrieved from http://www.thefsegroup.com/denition-of-an-sme.

6 Retrieved from https://www.enterprise-ireland.com/en/about-us/our-clients/sme-denition.html.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

9

Table 2: Firm Size Definitions

Start-Up Micro Small Medium Large

Number of Employees An early stage company (less than three

years in existence) that is trying to solve

problems with scalable, often innovative and

technology-oriented business solutions.

1 to 2 3 to 20 21 to 100 >100

Annual Sales (Rwandan

Franc [RWF])

<1 million 1 to 20 million 20 to 500 million >500 million

High-Growth Entrepreneurship

The definition of a start-up used by EDP goes hand in hand with the concept of high-growth

entrepreneurship, which refers to endeavors with the potential for exponential growth, also known

as “hockey-stick growth.”

7

In its distinction between start-ups and MSMEs, the EDP recognizes that

not all entrepreneurs are equal and different groups have different challenges which require specific

policy actions and support. For example, a small garment business in Huye has different needs from

a fintech start-up operating out of the KIC. The former might need a small loan for equipment and

value chain support to better connect with suppliers and clients; the latter might need an equity

investment (“risk capital”) for software development and facilitation of a partnership with a Pan-

African technology company. Both types of endeavors are important and the EDP is committed to

supporting entrepreneurs across the entire spectrum.

Throughout the EDP, whenever challenges and policy actions involve start-ups, they are by definition

related to high-growth entrepreneurship. A start-up, therefore, is not any company in its early stage

of formation, as it is commonly misperceived, but rather an early stage company with the potential

for hockey-stick growth.

8

MSMEs, in turn, are companies that meet the employment and annual sales

requirements defined in Table 2 and are poised to remain roughly at the same size or enjoy steady

(not exponential) growth overtime. Whenever the EDP discusses newly established businesses and

challenges associated with starting a business, it refers to them as “new firms,” which can be both

start-ups and MSMEs.

2.2 International Benchmarks

Leading countries in the developed and developing world have put in place targeted and effective

entrepreneurship development policies that have been evaluated and have contributed to their

successful economic transformation by creating robust ecosystems for entrepreneurship support.

Three countries stand out for their path to entrepreneurship as models for consideration for Rwanda:

Singapore, Israel, and Chile. Best practices from these and other countries have informed EDP actions.

Singapore

A small country with few natural resources, Singapore took a deliberate approach to foster its

economic growth trajectory. Through government support to entrepreneurship, Singapore has

established itself as a world-class example and a destination for entrepreneurs from around the

world. In a span of just five years, from 2010 to 2015, Singapore’s entrepreneurial ecosystem has

flourished. Singapore’s success story in entrepreneurship began with strong government leadership

that has passed business-friendly reforms, streamlined the process of business creation, facilitated

access to overseas markets, improved the venture capital landscape, and modified the tax program

to benefit start-ups. Singapore’s entrepreneurship hub — Block 71— has even been dubbed “the

world’s most tightly packed entrepreneurial ecosystem” by The Economist.

7 Hockey-stick refers to the growth graphic representing a short fall (early losses, adjustments, investments) followed by aggressive rise over a

short period of time (i.e., exponential growth). Retrieved from https://searchcustomerexperience.techtarget.com/denition/hockey-stick-growth.

8 Several other denitions for high-growth entrepreneurs are also used within the global entrepreneurship community, including gazelles, small and

growing businesses (SGBs), high-impact rms, and unicorns.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

10

Singapore employed several policy instruments to boost entrepreneurship. The country has a skilled

workforce and the ability to harness international talent through permissive visa arrangements. For

example, Startup SG Talent offers EntrePass, a visa program that allows international entrepreneurs

a two-year visa in Singapore. Singapore has a strong venture capital scene; venture capital investment

in the technology sector grew from less than $30 million in 2011 to more than $1 billion in 2013,

with one exit valued at $200 million. Finally, the country makes it easy to start a business; it regularly

scores among the top contenders in the World Bank Doing Business Index and ranked 27 of 177

countries on the Global Entrepreneurship Index. In 2018, International Enterprise Singapore and the

Standards, Productivity and Innovation Board (SPRING) came together as a single agency to form

Enterprise Singapore, offering market readiness assistance grants and funding to defray the cost of

overseas expansion and for Singapore-based companies to participate in international trade fairs.

This, coupled with existing programs and policies to benefit entrepreneurs, ensures a bright future

for start-ups.

In this way, Rwanda will look to Singapore for examples of how the government can support

entrepreneurship at a national level. Strong government leadership and a similar governance structure

in Rwanda allow the GOR to incorporate Singaporean best practices in its EDP.

Israel

Israel’s history of immigration and rebuilding has fostered an innate entrepreneurial culture, where

starting a business is a respected endeavor and entrepreneurs enjoy the support of both the private

sector and the government. Until the 1980s, entrepreneurs were likely to rely on personal or family

funding for working capital and growth. However, that began to change with Israel’s entrepreneurial

boom funded by the venture capital industry in the mid-1980s. The first venture capital funds were

funded by private investors, including Israeli Diaspora and expatriates. These funds supported start-

up companies to flourish, with an early focus on agriculture and agricultural technology (agri-tech), as

well as a strong focus on knowledge and R&D. The developments in agri-tech helped Israel cultivate

dry desert soil, increasing harvest yields.

Israel’s government support to entrepreneurs ranges from tax benefits for small companies employing

fewer than 10 people to government-backed bank loans and government-funded incubators. The

history of Israel’s start-up success is tied to Yozma, a government incubator developed in the 1990s,

which offered tax incentives for international entrepreneurs establishing a business in Israel and

doubling funds from the government. Today, Israel’s Office of the Chief Scientist uses its annual budget

of $450 million to offer up to 85 percent of seed funding for close to 200 incubated companies per

year, as well as support large-scale R&D projects by larger companies.

9

The country also boasts the

largest share of early stage and seed venture capital funding in gross domestic product among OECD

countries.

10

A shared history of recovering and rebuilding after a tragic past, the importance of Diaspora

contribution to the economy, and its role as a knowledge hub for the region sets Israel apart as an

attractive model for Rwanda.

9 Retrieved from https://www.geektime.com/2015/04/19/in-israel-behind-every-successful-entrepreneur-stands-a-lot-of-government-support.

10 OECD. (2016). SME and Entrepreneurship Policy in Israel. Retrieved from https://mof.gov.il/chiefecon/internationalconnections/oecd/oecd%20enterp.

pdf.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

11

Chile

With a rank of 19 on the Global Entrepreneurship Index, Chile is recognized for its government

policies and programs stimulating entrepreneurial growth. Chile has liberal immigration policies for

international entrepreneurs, a generous taxation program, and among the best business incubators

in Latin America. The Chilean Economic Development Agency, Corporación de Fomento de la Producción

de Chile (CORFO), is tasked with promoting economic growth in the country. It is the main driver

of entrepreneurship policy, with more than 50 programs to support entrepreneurs, both domestic

and international.

Major government-sponsored programs such as Start-Up Chile (SUP) have allowed the country to

pull ahead in the growth of start-ups led by Chileans and by international entrepreneurs. SUP offers

a $40,000 equity-free grant, a one-year visa, and six months of mentoring. SUP makes a distinction

between a government policy and a state policy. Since its creation in 2010, SUP has endured as a

state policy rather than the work of any one administration. Although it is run by the government and

funded by taxpayers, SUP functions more like a start-up program and less like a government agency.

It measures its success by its ability to change public perception of entrepreneurship and promote

a cultural change that allows its citizens, particularly youth, to attempt to start a business without

penalizing failure.

Attitudes toward entrepreneurship in Rwanda are similar to those that Chile experienced before

SUP. Many Rwandans view starting a business as a second option after formal employment. The

country’s best and brightest graduates seek jobs with major companies or in the public sector before

considering entrepreneurship. Chile faced a similar situation before SUP. However, since its creation

in 2010, Chile has drawn international entrepreneurs and investors by offering business development

services (BDS) and venture capital through SUP and has become known as a model often replicated

by governments around the world.

2.3 Development Process and Stakeholder Consultations

To identify the key constraints to entrepreneurship in Rwanda and develop EDP actions, extensive

stakeholder interviews were conducted, including with central and local governments in all provinces

and 20 districts as a representative sample, entrepreneurs from start-ups and MSMEs, representatives

from the PSF, banks, local and international investors, business consultants, academia, incubators,

accelerators, and donors. The EDP also draws extensively on the review of prior research and

assessment of Rwanda’s priorities under the NST1, PSDYE, and other relevant GOR policies and

strategies.

The development process is detailed in Figure 4.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

12

Figure 4: The EDP Development Process

Cabinet Approval (April 2020)

The policy was approved by the cabinet meeting of 17

th

April 2020.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

13

3. VISION AND OBJECTIVES

3.1 Vision

The EDP’s vision is to develop an effective entrepreneurship support ecosystem that creates the

necessary conditions and enablers for Rwandan entrepreneurs to unleash their entrepreneurial

potential and grow dynamic and competitive enterprises that will drive economic growth and job

creation.

3.2 Policy Framework

EDP uses a framework (see Figure 5) that focuses on the seven pillars of the entrepreneurship

ecosystem: human capital and management, business support, access to finance, business

enabling environment, access to markets and value chains, technology and infrastructure,

and entrepreneurial culture. This framework has been informed by internationally recognized

entrepreneurship frameworks

11

and has been adapted to key entrepreneurship priorities and

challenges in Rwanda based on consultations with key stakeholders and review of GOR’s existing

policies and strategies.

Figure 5: The Seven Pillars of the EDP

• Pillar 1: Human capital and management refers to the factors that affect the quality of

management at the firm level and of the workforce, including academic education, technical

training, and people’s general abilities and qualifications to enter the job market and start

their own businesses.

• Pillar 2: Business support encompasses the array of private and public players dedicated

to providing entrepreneurs with training, consulting, mentorship, networking, and BDS, as well

as basic premises and infrastructure, such as business incubators and accelerators.

11 Frameworks reviewed include those developed by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, OECD, World Economic Forum,

Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs, as well as global indices, such as the Global Entrepreneurship Index (Global Entrepreneurship

and Development Institute), Global Innovation Index (INSEAD), and Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) (Babson College).

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

14

• Pillar 3: Financing refers to the ability of entrepreneurs to access capital in its various

forms (equity, debt, grants) from private, public, and peer-to-peer sources.

• Pillar 4: Business enabling environment encompasses the laws, regulations, procedures,

taxes, and other micro- and macro-level aspects that influence business activity, productivity,

and growth.

• Pillar 5: Markets and value chains includes the upstream and downstream connections

businesses rely upon to source inputs and sell their products and services, allowing them to

grow profitably and sustainably.

• Pillar 6: Technology and infrastructure are the backbone of a well-functioning economy

and key enablers of sustainable entrepreneurial activity (e.g., access to basic utilities, innovations

like 3D printers) and the broader capacity to innovate through R&D.

• Pillar 7: Entrepreneurial Culture refers to the societal rules, perceptions, traditions, and

even taboos that directly or indirectly influence people’s propensity and ability to become

entrepreneurs and succeed in their endeavors.

3.3 Policy Objectives

The overarching objective of the EDP is to ensure that all seven pillars of the entrepreneurship

ecosystem function properly, allowing Rwandan start-ups, MSMEs, and large enterprises to grow

sustainably and profitably. EDP actions address constraints identified under each of the seven pillars

to achieve the following objectives:

1. Improve access to skills and know-how for existing and potential entrepreneurs to effectively

start and manage a business.

2. Improve business support system for entrepreneurs, including business consultants, mentors,

incubators and accelerators.

3. Improve entrepreneurs’ ability to access finance required for business growth from various

sources, including equity, debt, and grants from public, private, and peer-to-peer sources.

4. Streamline tax programs that are supportive to entrepreneurship development.

5. Expand access to domestic and export market opportunities for entrepreneurs.

6. Improve entrepreneurs’ access to technologies and innovations for business growth and

productivity.

7. Promote the culture of entrepreneurship and equitable access to business opportunities for all

entrepreneurs.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

15

4. ANALYSIS: CONSTRAINTS TO ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Constraints to entrepreneurship have been identified primarily through extensive stakeholder

interviews and consultations. The EDP identifies key gaps under each of the seven pillars of the

entrepreneurship ecosystem and includes corrective measures to address them, based on international

best practices and evidence referenced further in Chapter 5. Constraints summarized below are not

exhaustive, but have emerged in a close-to-consensual fashion in stakeholder interviews, focus group

discussions, and document reviews. They are considered priorities by stakeholders in terms of their

direct impact on entrepreneurial activity and potential positive spill-over effects, such as inclusive

economic growth and job creation; and are deemed solvable and actionable in the short, medium, or

long term.

4.1 Pillar 1: Human Capital and Management

No entrepreneurial ecosystem can flourish if entrepreneurs do not have the adequate support to

build the skills and know-how required to start companies and run them effectively, as well as to

operate the key functions of the companies. In Rwanda, the human capital hurdles in the educational

system and applied management spheres include:

• Formal Education

- Tertiary education deficit — Graduates of tertiary education generally lack technical

skills that respond to market needs. The quality of most tertiary education courses is

often criticized for being “too theoretical” and less applicable to the job market. This

explains, in part, why in Rwanda 25.7 percent of tertiary graduates remain unemployed.

12

In addition, only 6 percent of university students are enrolled in technical disciplines

such as engineering and just 9 percent are studying sciences, which are considered

low numbers by international standards.

13

Finally, teachers themselves frequently lack

practical experience, which does not help to bridge the gap between academia and

the job market.

- Weak education-market link — Linkages between tertiary institutions with industry

for skills development and practical training are weak, deterring both sides from

benefiting from each other.

- Entrepreneurship curriculum deficit — Formal entrepreneurship curriculum has been

introduced in secondary schools, but content is too basic and targeted at more

subsistence entrepreneurship, rather than higher-value endeavors. More sophisticated

and practical entrepreneurial concepts, such as lean start-up, business canvas, and

strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analyses, are not adequately

covered in the curriculum in terms of depth of content and time to practice.

- English language skills

14

— English is the key language for accessing international

knowledge, and the spread of the English language has been correlated with broader

economic development.

15

Sometimes, limited English capacity prevents technology-

oriented entrepreneurs from accessing free technical and business content in

e-learning platforms, such as massive open online courses (MOOCs), online webinars,

and YouTube e-learning channels, as well as engaging in relationships with international

entrepreneurs and mentors.

12 Labor Force Survey. Annual Report. (December 2018).

13 Statistical Yearbook. (NISR, 2017).

14 In October 2008, the Rwandan Cabinet passed a resolution calling for the immediate implementation of English as the language of instruction in

all public schools.

15 Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2013/11/countries-with-better-english-have-better-economies.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

16

• Management

- Poor business-family governance—Separation between business and family matters in

firms is usually weak, resulting in poor governance, with mixed bank accounts and

transactions, joint liabilities, and conflicting management practices.

- Management skills deficit—General management skills across the start-up and MSME

spectrum are usually poor, with entrepreneurs lacking the basic knowledge of business

disciplines such as accounting, marketing, strategy, and finance.

- Limited tax education—Entrepreneurs are not educated about the tax system and

often do not pay taxes correctly, incurring additional costs and penalty fees.

- Poor bookkeeping—Most micro and small businesses do not maintain bookkeeping,

which limits their capacity to plan efficiently and raise financing.

• Service Delivery

- Low level of service delivery—General customer care and client relations are still low

across all sectors of the economy. A study published in 2017 on customer-oriented

service culture in Rwanda found that there was a deficiency across customer

orientation practices such as management of staff, designing service processes for

quality service delivery, and customer-oriented culture.

16

The study notes that for

sectors such as tourism to flourish, customer service needs to improve in consistency

and quality in comparison to neighboring countries like Kenya.

17

4.2 Pillar 2: Business Support

The management deficit identified in Pillar 1 can be addressed in part by an active and efficient business

support system, composed of business consultants, mentors and coaches, business incubators and

accelerators, cooperatives and industry associations, and virtual platforms. While business support

has been gradually improving in Rwanda, key challenges remain, including:

• Consultant deficit—There is an insufficient number of high-quality consultants with sector

and business stage expertise and solid business management skills in both the public and

private sectors. The BDF business advisors throughout the country need to be supported

in improving their advisory programs. Start-ups, MSMEs, cooperatives, and individuals (youth

and women) need assistance in financial management and business plan development to

ensure sustainability and business growth in the long run.

• Low demand for advisory services—Demand for advisory services from businesses of

all sizes is also low due to little perceived value of consulting.

• Mentor deficit—No mentorship culture or formal mentorship networks exist in Rwanda;

experienced entrepreneurs and business people do not make themselves available to coach

and mentor start-ups and MSMEs.

• Incubator/accelerator deficit—There are not enough business incubators and accelerators

available to provide overall infrastructure and business support based on international best

practices and benchmarks. Simultaneously, there is limited demand for these services due to

the low number of entrepreneurs and start-ups.

16 Retrieved from https://www.ajhtl.com/uploads/7/1/6/3/7163688/article_36_vol_6__4__2017.pdf.

17 Retrieved from https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/123456789/7155.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

17

4.3 Pillar 3: Financing

Difficulty in accessing capital is a recurring complaint among entrepreneurs. It must be noted, however,

that Rwandan financial institutions do benefit from relatively strong liquidity and sound management.

For example, in 2017, according to the National Bank of Rwanda (BNR), capital in the sector was

comfortably above regulatory requirements and liabilities denominated in foreign currency were

low. In addition, the GOR has developed several programs to help MSMEs access financing. The main

hurdles that businesses of all sizes face in raising capital stem from market inefficiencies that, once

fixed, should unleash financing, including:

• Debt

- High collateral requirements—Banks have high collateral requirements and are

therefore often inaccessible for start-ups and MSMEs. The collateral requirement in

Rwanda is 120 percent of the loan amount, as governed by the BNR.

- Underutilized collateral guarantee program—BDF works with banks, microfinance

institutions, and savings and credit cooperative organizations (SACCOs) to cover

between 50 and 75 percent of the required collateral. While the program still works

well for medium-sized companies, the BDF guarantee is hard to access for micro

and small businesses and start-ups, because many MSMEs do not meet the lender’s

collateral requirements and thus do not qualify for BDF services. It also remains

underutilized by banks.

18

- Limited alternatives for collateral—Trade/inventory, finance/factoring, and leasing

are options for MSMEs and large enterprises, allowing the use of an invoice, contract,

or leased asset in lieu of collateral. Currently, the use of these mechanisms in Rwanda

is limited. There is a need for greater recognition of these approaches and regulatory

clarity in their use.

- Limited loan products for early stage businesses—Banks are reluctant to lend

to start-ups and early stage MSMEs due to lack of history and revenues. There are

limited loan products that take into consideration business plans, cash projections, and

entrepreneurs’ track records, as opposed to only assets and collateral.

- Short tenors and grace periods—Debt financing is usually limited to five-year tenors

with short or non-existent grace periods, which is insufficient for many enterprises

to recoup.

- High interest rates—Interest rates charged by lenders are too high, due to the

high cost of capital coupled with limited competition in the banking sector, making

borrowing prohibitive for low-growth businesses.

• Equity

- Limited understanding of equity investment—MSMEs that are not familiar with

equity investment tend to have higher barriers to trust of external parties for fear

of losing control of their businesses. This results in MSMEs not considering equity

investment as an option for funding their businesses.

- Seed capital deficit—There are limited financial resources available from family

and friends and limited other early stage equity funding options for start-ups, such

as seed funds and angel investors. There is a misalignment of expectations between

angel investors and MSMEs with respect to control, risk, and realization of investment

returns. For example, angel investors ask for significant control in return for limited

financing, making the deal unviable and diminishing the chances of long-term success.

18 U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Nguriza Nshore. (2018). Rwanda Banking and Investment Analysis.

RWANDA ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT POLICY

18

- Private equity and venture capital deficit—There is limited private equity and

venture capital funding available for growth-stage companies. This is due, in part,

to limited exit options, which in most cases are restricted to founder’s buy-back

and acquisitions. The very few private equity and venture capital deals taking place,

usually come from international funds that are investing in foreign-owned companies

operating in Rwanda.

• Grants and Other Financing

- Isolated grant programs—Grant and prize programs are available through select

incubators and accelerators, donors, and events/competitions. However, they are not

tied to follow-up financing and business growth targets. These one-off grants have

limited success rates.

- Uncertainty of timing amounts and procedures of grants—Grant programs have extensive

application processes and complex eligibility criteria, and are therefore inaccessible

for many MSMEs.

- Crowdfunding deficit—Despite the presence of platforms such as Kiva, GlobalGiving,