FSB discussion paper

Federation of Small Businesses

Telephone: 020 7592 8100

Facsimile: 020 7233 7899

email: london.policy@fsb.org.uk

website: www.fsb.org.uk

ENTERPRISE 2050

Getting UK

enterprise policy right

February 2013

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Authors

Professor Francis Greene

Francis Greene is Professor of Small Business and Entrepreneurship at Birmingham Business School,

University of Birmingham. He previously taught at Warwick, Durham and Mannheim universities. He has

done work for the OECD on small business and entrepreneurship policy issues and has been a visiting

researcher with Barclays Bank and with the New Zealand government where he worked on their policies

for supporting fast growth firms. He is also a consulting editor of the International Small Business Journal.

Priyen Patel

Priyen Patel is a Policy Advisor at the Federation of Small Businesses looking at finance and banking policy.

He has written reports on non-bank channels and the FSB’s submission to the Independent Commission on

Banking. He has previously worked for a political party and a bank.

www.fsb.org.uk

Synopsis

This report looks at the evolution of UK enterprise policy, offering a critique of the current landscape.

The report questions whether the 891 different sources of support for small businesses and 18 access to

finance schemes are the best way to organise enterprise initiatives, arguing that there are more effective,

focused approaches that could be followed from elsewhere in the world. Of particular interest is the

Kreditanstalt fur Wiederaufbau bank in Germany (the KfW), in operation since 1948, and the US Small

Business Administration (SBA) that was created in 1953. Both have a clear focus, which is to help small

firms access finance and push firms to export. The paper argues the new Business Bank should look

to these institutions for lessons, take the opportunity to rationalise the unwieldy set of support on offer,

and be the basis for a more fully fledged institution based on the SBA that will act as the anchor

for enterprise policy.

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Chapter 2: Current provision of UK enterprise support . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Chapter 3: A brief history of UK enterprise policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Why do governments intervene? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

A brief history of enterprise policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

1930-1979: The era of managed enterprise policy. . . . . . . . . . . .9

1979-1988: Increasing the ‘quantity’ of small businesses . . . . . . . .9

1988-1997: The focus on ‘quality’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

1997-2010: The ‘balanced’ approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

The Small Business Service . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

How eective has intervention been? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Chapter 4: Creating an anchor for enterprise policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

The principles of good enterprise policy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

The importance of institutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

The US Small Business Administration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Chapter 5: Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

www.fsb.org.uk

1

Chapter 1: Introduction

This report is intended to stimulate a debate around enterprise policy. By looking over policy formulation

stretching back to the 1930s, and drawing on extensive academic research, our work underlines that for

too long UK enterprise support for small businesses has lacked focus with numerous small initiatives with

dubious effectiveness, and has been overly complex and too costly. To address these issues and to provide

an anchor to policymaking and delivery of small business policies, it advocates the creation of a UK Small

Business Administration (SBA) to provide that ‘anchor’. Such an institution has been in place in the US since

the 1950s, with considerable success. Other countries have elements of that model in place, Germany’s

state-owned bank Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) for instance.

The issues and evidence to support the creation of a UK SBA are set out in Chapters 2, 3 and 4. Chapter

2 gives a high level summary of current enterprise support. It shows that there are currently 891 different

sources of support available to small businesses (BIS, 2012a). One evident problem with there being so

many schemes is that support may be being duplicated. Another issue is that the enterprise support is so

complex that the entrepreneur finds it difficult to access what potentially may be valuable public support.

As Chapter 3 shows, these issues are not new. It examines the history of UK enterprise support, revealing that

the design of enterprise policy objectives has shifted from using enterprise support as a tool for addressing

equity (social inclusion) or efficiency (productivity) concerns. It presents evidence to show that UK enterprise

support has been costly, with the most recent estimate suggesting that total annual public sector expenditure

on small firms costing £12 billion (Richard Report, 2008).

In addition Chapter 3 considers the problems inherent in the way the UK has approached the delivery

of enterprise support. It identifies that the delivery of enterprise support has been marked by a series of

weaknesses including: a congested and confusing supply of such provision; high levels of policy initiative

‘churn’; duplication of provision; and a weak evaluation culture. It provides a brief critique of the creation of

the UK’s Small Business Service (SBS) intended to address these weaknesses, and why it failed. This institution

was set up in the early 2000s to act as the lead body in supporting small businesses but abandoned a few

years later for two central reasons:

• The SBS was given responsibility but had very limited ‘power’ across central government; and

• The SBS’s objectives were so broad that it was extremely difficult to correlate its activities with its

given targets.

Chapter 4 compares the UK experience with that of other countries, and especially the United States’ SBA.

Operating for nearly 60 years, the US SBA has consistently focused its efforts on three core activities:

• Access to finance solutions;

• Government procurement; and

• Business advice and assistance.

In conclusion, the report argues that policymakers can and should learn from both the SBA in the US and

from the UK’s failed experiment with the SBS as well as drawing on insights from other models operating

successfully in other countries, including the German KfW bank. It suggests that the UK should consider the

creation of a UK SBA with clear legislative powers so that its goals and targets are achievable. If the policy

is adopted, its ambition needs to be narrow too: a salient lesson from the prior contrasting experience of

both the SBS and the US SBA is the necessity to focus on a core set of enterprise activities. Certainly from

the outset, this report argues that the central focus of a UK SBA should be on improving access to finance for

small businesses and that opportunity may be emerging with the fledgling Business Bank.

2

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Chapter 2:

Current provision of

UK enterprise support

The UK economy, as with all other economies, currently faces significant challenges in dealing with the

‘great recession’ that has occurred since the onset of the financial crisis in 2008 (Fairlie, 2011). This

Government, as with the previous government, has sought to support the financial solvency of the banking

system and promote the vibrancy of its enterprise population (OECD, 2012).

To meet that aim, various mechanisms to support financially constrained small businesses have been

developed either by indirectly encouraging UK banks to lend more to small businesses (the Enterprise

Finance Guarantee, Project Merlin, Business Finance Partnership or the recently announced Funding for

Lending) or by direct attempts to provide access to finance solutions for small businesses either mediated

by the banks or through setting up a Government-backed Business Bank.

The Government has also sought to reconfigure existing support. Following on from the Richard Report

(2008), it has reduced - if only for the English regions - the scope and delivery ambitions of Business

Link down from a ‘cradle to grave’ advice and assistance program to an internet and telephone based

information and signposting service. In addition the Regional Development Agencies (RDAs) have been

replaced by Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) in the hope that these new business-led organisations will

provide better, more focused, regional provision of support.

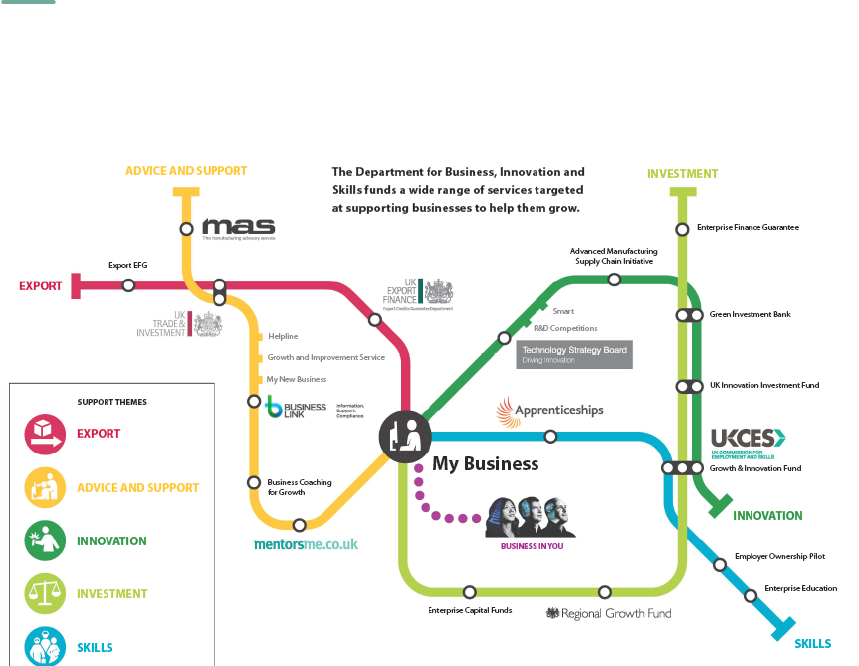

Figure 2.1 shows the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills’ (BIS) enterprise support ‘journey

planner’. This is designed to orientate a business (‘my business’) through its five most common support

needs (exporting, innovating, advice, investment and skills). It suggests that there are 18 main ‘stations’

of support (denoted by the circles) available from BIS. Taken at face value, Figure 2.1 would imply that

UK enterprise support is focused and simple.

www.fsb.org.uk

3

Figure 2.1: Business journey planner

Source: BIS, 2012a

This ‘journey planner’, however, masks the complexity of current government enterprise support. There are

three illustrations of this.

First, as Chapter 3 will highlight, central Government expenditure and activities to support enterprises are

not confined to BIS. In fact, the most recent official estimate of UK enterprise activity and cost (PACEC,

2005) suggests that BIS only accounts for about one-fifth of actual Government expenditure on smaller

businesses with the rest being spread across other Government departments. That would imply Figure 2.1

significantly under-estimates the cost and complexity of UK enterprise support.

Second, Table 2.1 shows central Government’s current access to finance initiatives. In total, it highlights

18 access to finance schemes rather than six sources of investment support (Figure 2.1). This brings to

light two other aspects to small business support:

• There is a great diversity of support available to small businesses. This may be judged important

because small businesses are heterogeneous; and

• It is answer to the perceived need, given the prevailing macro-economic climate and the

acknowledged difficulties that small businesses face in accessing finance, for the Government

to have a greater range of responses to the current barriers facing smaller businesses.

Set against this argument, one drawback with this range of activities is the potential for duplication

of support to small businesses with support providers coming from both the public and private sector

4

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

with attendant ‘crowding out’ effects. A further drawback to these different routes to support is that it

is potentially complex for ‘consumers’ of their services – small firms themselves as well as their various

supporting agents such as accountants and tax planners. Consequently, the support landscape can

become confusing to resource constrained small businesses and their stakeholders

1

.

Table 2.1 Current UK Government access to finance initiatives

Name of Scheme Target Groups Contact point

1 Funding for Lending Scheme (FLS) Businesses and consumers Banks and building societies.

2 Start Up Loans Young people between 18-30 www.startuploans.co.uk

3 Youth Contract Wage Incentives SMEs taking on apprentices Jobcentre Plus

4 AGE Employer Incentive

Small firms taking on their first

apprentice aged 16-24

National Apprenticeship

Service

5 Regional Growth Fund Varying organisations BIS

6 New Enterprise Allowance Unemployed people Jobcentre Plus

7

Technology based SME development

of new products/services

Innovative SMEs Technology Strategy Board

8 Business Finance Partnership

Organisations looking to lend to

businesses

HM Treasury

9

Community Development Finance

Initiatives (CDFI)

Unsuccessful loan applicants from

disadvantaged communities

Via CDFIs

10 Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme

Investors in SMEs with turnover

below £200K

Via HMRC

11 Enterprise Investment Scheme

Most unquoted trading companies

with <250 employees

Via HMRC

12 Venture Capital Trusts SMEs Via HMRC

13 Business Angel Co-Investment Fund

Investment/mentors in

angel syndicates

Via individual funds

14 Enterprise Capital Funds SMEs ECF fund managers

15 UK Innovation Investment Fund (UKIIF) Specialist technology funds Via Fund of Funds managers

16 UK Export Finance products Exporters, particularly SMEs Via UKEF

17 Enterprise Finance Guarantee SMEs with turnover below £41m Banks

18 Growth Accelerator SMEs with high growth potential www.growthaccelerator.com

1 See, for example, the ‘teething’ problems witnessed by the banks and their small business clients when the Enterprise Finance

Guarantee Scheme was expanded in 2010 (House of Commons Business, Innovation and Skills Committee, 2011).

www.fsb.org.uk

5

As the remainder of the paper aims to demonstrate, these initiatives are in stark contrast to enterprise

support in the US, which uses its SBA as the principal delivery mechanism for supporting small businesses.

Moreover, despite the heterogeneity of small businesses, the US SBA has just four main schemes to

support small businesses (see Chapter 4 for further details). Evidence also suggests that the US has been

able to lend more to small businesses in the current economic climate (FSB, 2012).

The third and final illustration is that although it is difficult to capture the full extent and cost of current

enterprise support across all areas of the public sector, the Government’s own ‘GRANTfinder’ service

identifies 891 support schemes available to small businesses (BIS, 2012b). Figure 2.2 shows the two

main features of this provision:

i. Business support is largely focused on businesses that either want to grow or survive (773

sources of support for ‘growth and sustain’) and start up activities (639) rather than pre-start up

(237) or exiting the business (37); and

ii. Support is most often in terms of expertise and advice (432) or grants (321) rather than loans

(122) or equity (31).

Figure 2.2 Target groups and types of BIS support available through

‘GRANTfinder’

Source: BIS, 2012b

6

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Source: BIS, 2012b

Again, the sheer number and diversity of schemes is likely to pose problems for time-poor small businesses.

The very nature of having many schemes often means decisions are delayed or not made at all. Much of

this is due to the overwhelming level of information and duplication which small firms will not have time

to consider. Such complexity in the support ecosystem is in contrast to the US SBA which offers a limited

menu of advice and assistance (principally through its network of Small Business Development Centers)

to existing entrepreneurs. As Chapter 4 will show, the focus of the US SBA is also on access to finance.

A final observation is the balance of such support may be inappropriate. Greene (2012) identifies

that there is no deficit of individuals coming forward wishing to set up a business in many developed

economies. Indeed, the UK enterprise population has grown more than a quarter in recent years, up

from 3.5 million in 2001 to 4.5 million in 2011 (BIS, 2011). Where the challenge lies is to ensure the

vibrancy and growth of the business population, particularly as businesses with growth ambitions are key

to the UK economy providing jobs and innovation (van Praag and Versloot, 2007).

www.fsb.org.uk

7

Chapter 3:

A brief history of

UK enterprise policy

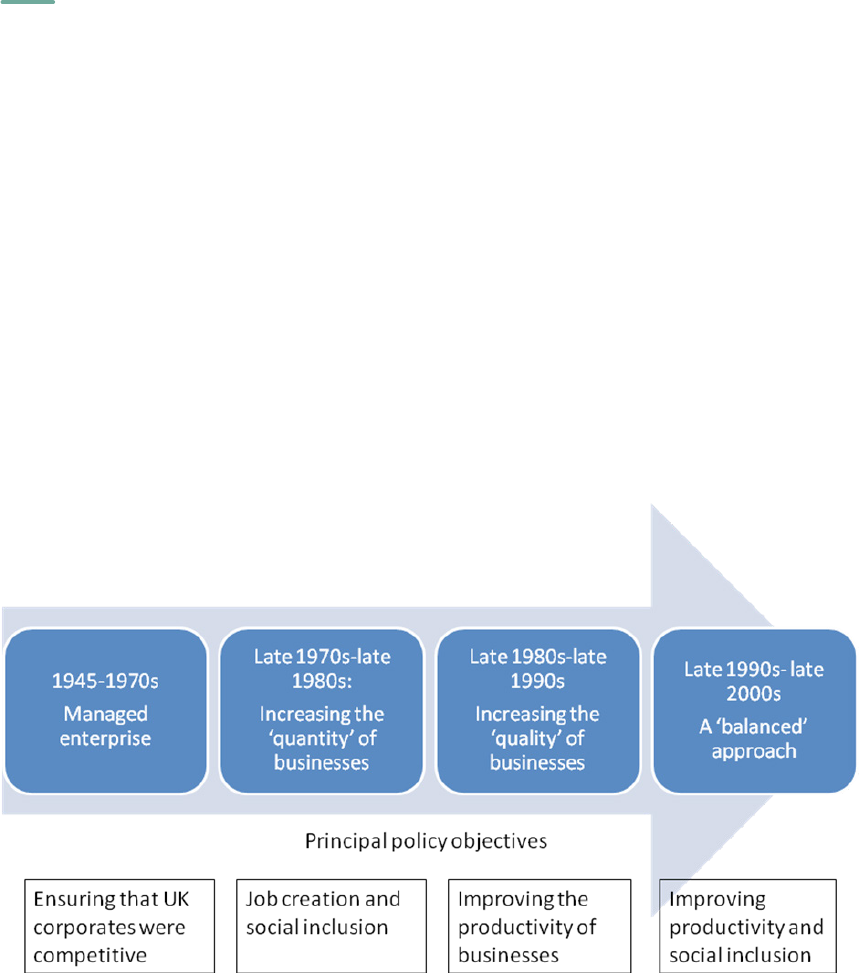

The previous chapter gave a summary of the current enterprise support environment. This chapter provides

a brief overview of how the UK has arrived at that point through a review of the evolution of UK enterprise

policy since the last century. Figure 3.1 summarises that evolution, showing that surprisingly, in light of

their current importance, small businesses were not a policy focus for much of the last century when

small businesses were seen as “inimical to progress and professionalism” (Boswell, 1973:19) or run by

individuals at the margins of society (Stanworth and Curran, 1973).

It was only in the 1980s when the development of a policy to increase the ‘quantity’ of new UK

businesses came to the fore, and small business came to be recognised for their potential to create jobs

(Birch, 1979) and be a source of productivity gains. Towards the end of the 1980s and into the 1990s,

the emphasis shifted to improving the ‘quality’ of the UK small business stock through targeted initiatives

such as Business Link. By the 2000s, the approach became more ‘balanced’ as policymakers sought to

use enterprise policy both as an instrument of social policy to improve opportunities for disadvantaged

individuals and communities and, at the same time, to improve the productivity of small businesses.

Figure 3.1 The evolution of UK enterprise policy

8

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Why do governments intervene?

Before looking at the history of enterprise policy, it is useful to set out the rationale for government

intervention. Generally, the central rationale for public sector interventions to support private sector

businesses is the presence of market failures – instances where the private sector fails to provide otherwise

desirable goods and services, meaning a role exists for the state to intervene to ensure these goods and

services are provided. Market failures exist in the small business domain for three main reasons:

1. When there is insufficient competition such as evidence of barriers to entry and exit, oligopoly

or monopoly in markets;

2. Where there are information asymmetries between consumers and suppliers, for example,

banks unable to assess the risks of investing in a new technology or business model; and

3. If unpriced positive externalities exist, it means the firm cannot extract all the rents it is due from

its activity. Such externalities take various forms but mean that others can take advantage of

the firm’s activity for free. For example, a new technology in the absence of patent protection.

In these cases, the supply of such goods is below the optimum.

Potential and actual entrepreneurs are likely to face persistent market failures. New entrepreneurs, for

example, may be ignorant of the benefits of starting and running a new business. Enterprise policy may

therefore advantage individuals and particular groups in society such as the young, ethnic minorities and

women by addressing such information asymmetries. Information imperfections may also be experienced

by existing businesses, which limit their potential to survive and prosper. Equally, dynamic businesses

with a growth orientation may experience particular barriers, for example accessing export markets and

training their staff, which may limit their ability to grow successfully.

However, it is not enough to demonstrate that market failures exist: these constitute a necessary but not

sufficient reason for intervention. What also needs to be demonstrated is that overall, the social benefits

of intervention outweigh its social costs. Interventions to meet this test can be grouped as:

• Support to improve access to finance - loan guarantees and venture capital funds for example

• Interventions to improve entrepreneurial awareness and propensity amongst the young -

enterprise in secondary schools, the expansion of tertiary enterprise education

• Interventions to improve social inclusion - supporting the unemployed into business ownership;

hard (financial) and soft (training, mentoring) support for disadvantaged groups and businesses

• Soft support to improve managerial capabilities and capacities in small firms

• Horizontal support (generic tax and infrastructure support to make it easier for businesses to do

business) and sector specific support (support designed to increase the quantity and quality of

businesses in a particular sector)

• Export support - financial support to access overseas markets and trade missions to new markets

• Innovation support - financial support for high-tech businesses whose lack of a track record

makes it difficult for them to access equity or mezzanine finance

www.fsb.org.uk

9

A brief history of enterprise policy

1930-1979: The era of managed enterprise policy

For most of the last century, small businesses were largely ignored by British policymakers with two

notable exceptions. First, following the Wall Street crash of 1929 and the ensuing global depression, the

Macmillan Committee (1931) identified that British small businesses were ill-served by the British banking

system – a situation current politicians will not be unfamiliar with. The Committee called for a rebalancing

of the relationship between banks and their small business customers. Out of this the Industrial and

Commercial Finance Corporation was formed. Second, following the post-war decline in Britain’s small

business population, the Bolton Report (1971) sought to identify why this occurred and was allowed to

happen and what could be done to support small businesses. This led to the creation of the Small Firms

Service in 1973.

There were few other policy initiatives over the period aimed at supporting small businesses (Beesley and

Wilson, 1984). Instead, policymakers were interested, particularly in the post war period, in an industrial

policy that sought to rationalise UK-plc into ever bigger and better corporate entities

2

. This policy of

‘picking winners’ failed. Rather than policymakers focusing on ‘sunrise’ industries, what happened in the

1960s and 1970s was that “it was losers like Rolls Royce, British Leyland and Alfred Herbert who picked

Ministers” (Morris and Stout, 1985: 873).

By the late 1970s, however, an increasing interest was taken in small businesses for a number of reasons.

One was that there was increasing recognition that Keynesian demand-side policies of the 1960s and

1970s had left Britain as the ‘sick man of Europe’. In its place, the rise of supply-side economic theory

and political shifts meant there was an increased belief that supply-side reforms to liberalise product

and factor markets would lead to economic growth (Joseph, 1976). Another factor was the emergence

of unprecedented high levels of unemployment in the 1970s. Policymakers began to realise that small

businesses were potentially central to the economic renewal of the UK, and they were also increasingly

seen as a means to reduce unemployment. Because small businesses then – as now – represented 99

per cent of the total UK enterprise population, the hope was that if small businesses could be persuaded

to employ just one extra worker, the unemployment problems of the 1970s would be eased (Appleyard,

1978).

1979-1988: Increasing the ‘quantity’ of small businesses

Two events in 1979 heralded the shift away from the managed (corporate) policies of the 1960s and

1970s and towards enterprise (small business) policies. The first was the publication of research that

found that small firms – rather than large firms – were net job generators (Birch, 1979). This provided a

rationale for government support of smaller businesses. The second event was the election of the Thatcher

administration that saw the need to rebalance the UK economy towards promoting competition and

enterprising behaviour.

While this administration introduced initiatives such as the ‘first generation’ of Enterprise Zones, the

Business Expansion Scheme (tax relief for investments in new companies) and the introduction of the Small

Firms Loan Guarantee scheme, its main policy aim throughout the 1980s was to increase the uptake of

enterprising activity. Attention therefore focused on lowering the barriers to business entry, promoting the

benefits of entrepreneurship (Fraser and Greene, 2006) and to respond to the persistent unemployment

of the 1980s, encouraging the unemployed to start up their own business.

2 This should not be seen as a particularly British concern. As Audretsch and Thurik (2004) suggest the main aim of European post-

war enterprise policy was to ensure that Europe had more ‘elephants’ (large firms) than the US. Klapper et al (2012) identify that

this led, in France, to policymakers largely ignoring smaller businesses.

10

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

This interest in small business and self-employment led to an increase in the number of policy initiatives:

there were 33 initiatives between 1971-1981 (Beesley and Wilson, 1984) compared to 103 over the

period 1982-1989 (Curran and Blackburn, 1990).

Overall, if judged simply in terms of the aim of increasing the number of UK small businesses, this policy

focus was a success. Programs such as the Enterprise Allowance Scheme (565,700 participants over its

lifetime, 1983-1991) helped lift the UK enterprise population from 2.4 million businesses in 1980 to 3.6

million in 1989 (Greene, 2002).

1988-1997: The focus on ‘quality’

Although new entrants bring productivity benefits (Disney et al, 2003), the UK has perennially suffered

from a ‘long tail’ of under-performing businesses. Since nearly all UK businesses are small businesses,

successive Conservative administrations during this period brought forward a series of policy innovations

to improve the ‘quality’ of the stock of small businesses. Initiatives included governance innovations (re-

aligning the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) as the ‘Department for Enterprise’; the replacement of

the centrally managed Manpower Services Commission with local Training and Enterprise Councils)

3

; and

initiatives to improve managerial practices in smaller businesses (the ‘Consultancy Initiative’; ‘Managing

into the 1990s’).

The principal enterprise policy innovation of this period was the creation of the Business Link network.

Piloted in 1993, the aim of Business Link was to rationalise business support by acting as a ‘one stop

shop’. Its other main role was to focus directly on helping small businesses grow and to support this effort,

a network of ‘personal business advisors’ was created. Its explicit remit was to concentrate on businesses

with between 10 and 200 employees with growth potential.

Overall, from a pure growth point of view it is not clear whether these policy innovations had their

desired goal (Curran, 1993). Barrell et al (2010) identify that GDP growth per annum over the period

1987-1997 was 2.3 per cent. This was higher than France but lower than Germany, Japan and the US.

Moreover, if the aim was to rationalise business support and focus on quality then that aspiration was not

met. The number of dedicated small business policies in fact increased markedly, up from 103 initiatives

over the period 1982-89 to more than 200 initiatives by 1996 (Gavron et al, 2000).

1997-2010: The ‘balanced’ approach

Small business policy continued to evolve under successive Labour administrations during this period.

Some policy innovations remained. For example, despite concerns about the quality of ‘personal business

advisors’ and the crowding out effects of subsidised public assistance to other private sector support

providers (Chambers of Commerce, accountants) (Bennett, 2010), Business Link stayed as a ‘cradle to

grave’ small business support service.

During this period there was a continued focus on encouraging enterprise activities amongst disadvantaged

groups. This included not only helping the unemployed into business through the New Deal initiative

but broadening support through initiatives such as the Phoenix Fund, the development of Community

Development Finance Institutions and the Community Development Venture Fund.

3 Although this review focuses on the broad patterns of UK enterprise policies, there have been differences within the UK. For

example, Brown and Mason (2012) show that there have been similar policy movements in Scotland, although the emphasis

and pace of these has differed from the wider UK changes in the policy environment. Hence, Brown and Mason suggest that the

emphasis of Scottish enterprise policy was on supporting Foreign Direct Investment (1945-1990) before this shifted to increasing

the ‘quantity’ (Scottish Birth Rate Strategy) of new businesses in the 1990s. Since the 2000s, the emphasis has shifted towards

supporting ‘quality’ (high growth starts in the 2000s; high growth firms in the 2010s) businesses.

www.fsb.org.uk

11

Initiatives also continued to focus on reducing the distance between education and enterprise (the Lambert

Report (2003); the Science Enterprise Challenge; and the Davies Report (2002)) as well as initiatives

designed to alleviate the equity gap preventing fast growth businesses accessing angel and venture

capital finance (the UK High Technology Fund; Regional Venture Capital Funds; the Early Growth Fund).

Following on from the evidence provided by endogenous growth theory, a distinct emphasis was placed

on the positive externalities of agglomeration. This was focused at the sub-regional level by the creation

of Regional Development Agencies that was, inter alia, designed to support the development of particular

‘clusters’ of innovative high tech small business activity (Porter and Ketels, 2003).

The Small Business Service

Another significant policy innovation of this period was the creation of the Small Business Service (SBS)

in 2000. As already suggested, insights from the UK’s experience with this failed model is informative to

how future enterprise policy should be built.

The SBS was a dedicated agency within the DTI whose role was “to build an enterprise society in

which businesses of all sizes thrive and achieve their full potential”, “which listens to their needs and

influences all of Government to ‘Think Small First’”, and to provide “more coherent delivery of services

from Government departments, by sharing objectives and working collaboratively at all levels: nationally,

regionally and locally”.

In effect, the SBS’s role was to act as an ‘innovator’, a ‘centre of expertise’ and an ‘engine for change’

between Whitehall policy communities and the delivery of small business support. To achieve this, there

was a focus on seven policy ‘pillars’ and a focus on targets that were evidence-based

4

.

Despite these lofty ambitions, the SBS was short lived. The executive agency status of the SBS ended in

April 2007 with critical reports by the National Audit Office (2006) and the House of Commons Public

Accounts Select Committee (2007). Two main failings were found:

1. It was difficult to correlate its performance against targets; and damningly

2. It was a poor champion of small business across Government.

These frailties, however, need to be contextualised against the increasingly complex and costly nature of

enterprise support. In the first estimates produced anywhere in the world of the cost of enterprise support,

in 2002 a joint DTI-HM Treasury report identified that in 2001, enterprise policy represented an annual

cost of £8 billion. Major costs were the Common Agriculture Policy subsidies (£2.8 billion) and tax

incentives of £2.75 billion (income foregone rather than direct expenditure). This meant direct expenditure

on enterprise support was £2.5 billion. As Bennett (2008) suggests, this equates to about £600 per UK

business or about £2,000 per business (at 2005 levels) for those businesses that employ staff.

A similar analysis by PACEC (2005) for 2003-04 revealed that the overall cost of enterprise support was

£10.3 billion, of which £2.4 billion was agricultural subsidies and £3.6 billion was tax incentives. This

implies that £4.3 billion was spent directly on enterprise policy, roughly equating (again using 2005

figures) to £1,000 per UK businesses or £3,500 per UK employer businesses.

An important feature emerges from this analysis, and why the SBS was doomed to fail: which is that direct

government enterprise spending is widely spread across central Government departments. Although the

DTI, along with the SBS, was the lead department, its actual direct spending on small businesses was

4 The seven policy pillars were: macroeconomic stability; investment; science and innovation; best practice; raising skills and

education levels; modern infrastructure; and creating the right market conditions.

12

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

£696 million (or about 18 per cent of direct enterprise spending). Other major departments were the

Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (£297 million), the Department for Culture, Media

and Sport (£336 million) and the Department of Work and Pensions/Jobcentre Plus (£331 million). So,

too, was the Learning and Skills Council (£1.7 billion). This wide web of spending departments meant the

SBS – like the DTI – did not have direct control over the majority of enterprise support: it was an exercise

in responsibility without power.

Another now familiar feature also emerges: that enterprise support had become increasing complex

(Curran and Blackburn, 2000) and that an ‘enterprise industry’ had come into being (Lovering, 1999).

While government accounting of the level of enterprise support had become clearer and more transparent

since Gavron et al (2000) estimated that there were over 200 small business support programs in

operation in 1996, this did not stop new schemes coming into being. By 2005 an estimated 267

central government enterprise support services and over 800 small business support schemes were in

operation in three English regions (PACEC, 2005) while a wider estimate suggested that there were

3,000 enterprise support programs available to small businesses in 2006 (NAO, 2006). Given this

complexity, it is difficult to see how the SBS could easily and readily correlate its performance with its

targets. Support had also become more costly. Official estimates suggested enterprise support increased

from £8 to £10 billion while unofficial estimates put the cost at £12 billion with 2,000 separate providers

of public support to smaller businesses (Richard Report, 2008).

www.fsb.org.uk

13

How eective has intervention been?

If market failures persist over time, it would be reasonable to assume a stable set of small business policies

would have been developed. But as this chapter has shown, the UK Government ‘strategy’ for supporting

small firms has shifted over time. These changes are evident in the way the UK Government has chosen

to deliver enterprise policy, and the effectiveness of those interventions. The following now looks in more

detail at those interventions.

Table 3.1 shows the ‘development’ of business advice and consultancy over a 40 year period (1973-

2011). Business support has fluctuated between different managerial points, different delivery managers,

different fee structures and variations in the intensity of advice and assistance.

Table 3.1 Advice and consultancy schemes in the UK, 1973-2011

Main Schemes Period

Point of

management

Administration Delivery Client fees

Intensity of

advice

Small Firms

Service (SFS)

and Business

Development

Service

1973-88

Central and

government

regional

offices

Civil servants

Referral

and market

consultants

Free advice,

subsidised

consultants

Mainly low,

a few high

SFS and

Enterprise

Initiative

1988-93

Central and

government

regional

offices

Civil servants

Referral

and market

consultants

Free advice,

subsidised

consultants

Mainly low,

more high

Business Link

1993-

2005

Local: County

and districts

level

Contracts to

government

agencies,

partner

bodies, and

franchisees

Internal,

Partnership

Brokers

Accreditation

Scheme

(PBAs), and

some referral

Complex mix

of with fee

targets

Targeting

high, also low

RDAs and

Business Link

2005-

2010

Regional and

county level

RDAs, partner

bodies, and

specialist

contractors

Internal, PBAs,

and some

referral

Complex mix

with some

fee targets

Targeting

high, also

low, varied

Local

Enterprise

Partnerships in

England

2010-

Local: City-

region and

county

Local strategy

boards

Partners and

private sector

Existing

supplier fees,

with some

subsidies

Mainly low, a

few high, very

varied

Source: Bennett (2012)

As well as an ever changing delivery models, enterprise support has also been historically overly complex.

This is evident in three main ways.

First, as noted earlier, there is the sheer number of schemes available. Greene et al (2008) charts the

steady accretion of enterprise support in just one area – Teesside – over a 30 year period. Figure 3.1

shows that the delivery of enterprise support in Teesside has varied between start-ups and established

businesses, soft and hard support and local, regional and national providers. More broadly, the Bank

of England identified that, just in terms of access to finance, there were 183 initiatives in 2003, leading

them to report that “it is hard for businesses (and their advisers) to review what is available and find the

best scheme”.

14

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Figure 3.1 Enterprise Support Providers and Initiatives in Teesside (1980-2006)

Source: Greene et al (2008)

A second issue is the sheer churn of initiatives. In general, what can be discerned is that the average

enterprise initiative faces the same fate that befell many Victorian children: some are stillborn, while the

vast majority of them die in infancy or early childhood (Hughes, 2009). Moreover, for those that do

survive through to their teenage years (Enterprise Zones, 1981-1996), they face the prospect of being

abandoned, re-named or ‘re-discovered’ (Enterprise Zones, 2011- onwards).

The third issue is the duplication of enterprise policy. Take, for example, the challenges faced by the

Prince’s Trust. For nearly three decades the Prince’s Trust has provided a package of both soft and hard

support to disadvantaged young people who want to set up their own business. Despite the Prince’s Trust

being seen as a policy ‘success’ (Lord Young, 2012), this has not prevented the current Government from

developing the ‘StartUp Loan’ programme for young people which also offers hard and soft support. This

is not the only competing government scheme. There is the New Enterprise Allowance introduced 2011

(a mix of hard and soft support for the unemployed aged 18 and over). This scheme is itself a successor

to previous iterations of attempts to support young unemployed individuals: the ‘six month offer’ (January

2009-March 2011); self-employment options under the ‘New Deal’ between 1998 and 2011 - New

Deal Young People, New Deal 25+, New Deal 50+; the Business Start up Scheme between1991 and

1995; or the Enterprise Allowance Scheme, which ran between1983 and 1991

5

.

5 There is a similar contrast with Shell LiveWIRE. Shell LiveWIRE was 30 years old in 2012. Since 1982, it has consistently

provided signposting services and awards to young people seeking to set up a new business (Greene and Storey, 2004).

Successive UK Governments have introduced similar services ranging from interventions in tertiary education (Graduate Enterprise

(1982-1996), Enterprise in Higher Education (1987-1996), Science Enterprise Challenge (1999-2004) and other more generic

young people focused services (Enterprise Insight (later rebanded as Enterprise UK) (2004-2011) and a whole host of government

backed specific schemes such as recent ones like ‘Make Your Mark’, ‘Flying Start’ ‘Make Your Mark with a Tenner’).

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

Soft Hard Soft Hard Local Regional National N.of

Providers

N. of

Schemes

Pre Start up Post Startup

Location

1980 1982/83 1988/89 1994/95 2006

www.fsb.org.uk

15

Given the degree of initiative churn, and the complexity and duplication of enterprise support, it is

difficult to evaluate the efficacy of enterprise policies. This is because there have been very few robust

evaluations of enterprise policies

6

. Nonetheless, the evidence base suggests that, at best, government

enterprise policy has a patchy record of successfully supporting small businesses. For example, historical

analysis of business advice and consultancy services shows that while usage levels of public enterprise

support increased over the period 1973-2010, satisfaction rates fell over the same period from 95 per

cent (1973-1988) to 79 per cent (2005-2010) (Bennett, 2012).

In addition, there is a dearth of evidence to suggest that supporting start-ups actually produce favourable

outcomes (Shane, 2009). There is, however, strong international evidence to suggest that governments

have proved more successful in supporting growing (Morris and Stevens, 2010) and innovative businesses

(Foreman-Peck, 2010; Lerner, 1999) and in the provision of hard support, particularly through well-

established loan guarantee schemes (Oh et al, 2009; Cowling et al, 2008; Cumming, 2007; Riding

and Haines, 2001).

Overall, what emerges from this review of both current and previous enterprise policies is a ‘patchwork

quilt’, ‘chaos’, ‘labyrinth of initiatives’ or ‘muddle’ (Audit Commission 1999, DTI/HM Treasury 2002,

DTI, 2007) of government initiatives to support small businesses. A major explanation why governments

often feel a need to intervene is when economic conditions or public voices raise areas of concern - the

laudable intention is to ‘do something’. However, policy and its behavioral intentions are not matched

by evidence and the time needed for initiatives to ‘bed in’. As this paper argues, a more vigorous, long

term approach is needed. The supply of such schemes still remains congested, potentially crowding out

private sector provision. Their sheer complexity and variety presents real problems for time constrained

small businesses, making it difficult for them to access and utilise a complex package of government

support, particularly when the ownership of these variety of schemes is spread across different government

departments.

6 In this context, a robust and reliable evaluation is one that either uses a randomised control trial approach or one that uses quasi-

experimental techniques to match treatment and control groups. The most famous example of an RCT approach in enterprise

support is that of Benus (1994) who showed that a Massachusetts programme to support the unemployed into self-employment

was beneficial. Bakhshi et al (2011) also use an RCT approach to evaluate innovation vouchers. Below the gold standard of

RCTs, quasi-experimental evaluation studies have also provided robust evidence (e.g. Meager et al, 2003; Gorg and Strobl

(2006); Mole et al (2008.

16

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Chapter 4:

Creating an anchor

for enterprise policy

To provide greater clarity and coherence to UK enterprise policy, this chapter considers institutional

frameworks and the case for a UK Small Business Administration (SBA) similar to the US model operating

since 1953. As this paper has already shown, UK enterprise support has been marked, not only by

fluctuations to the design of enterprise support, but also that the delivery of enterprise support has been

overly complex and costly. It argues that these frailties could be resolved through the establishment of a

UK SBA ‘anchor’ to bring strategic coherence to UK enterprise support.

If the approach is adopted, a UK SBA needs time to bring strategic coherence to enterprise policy

alongside the requirement for consensus about the long term strategy underlying the UK enterprise support

system. As this paper has suggested, enterprise support needs to be clear that the best way to aid small

businesses is by focusing on a narrow set of activities which has access to finance solutions at its heart.

It is far more than a rearranging of Whitehall ‘deckchairs’.

www.fsb.org.uk

17

The principles of good enterprise policy

Many reports and papers have suggested gold standards for policymakers to follow when designing

enterprise policy. To that extent there is now a refreshing alignment of theoretical thinking from many

governments which encompasses a hard-headed edge to policymaking and a ‘less is more’ approach,

with a maturing understanding of what types of policies are likely to provide greater benefits to both the

taxpayer and small businesses.

Where governments do intervene, experience shows that “structures for government provision, covering

a whole country, with simple and single branding, offer superior management of expectations, simpler

means of quality control and much lower costs of provision” (Bennett, 2012: 206). A further factor is

the greater recognition that enterprise policy is more likely to be effective when it follows a ‘less is more’

approach. One clear message from the UK experience is that “there are too many initiatives for SMEs

and entrepreneurship and what we need is fewer interventions but ones that have much higher impact”

(Blackburn and Shaper, 2012: 2). However, and as this paper has touched upon, there are still too many

examples today where we find political factors and ‘loud voices’ often pushing and pulling policies which

are not evidence based or in fact needed.

Policy intervention also needs to properly target end users. The FSB would urge policymakers to consider

the difference in business size and characteristics within the ‘SME’ sector. The needs for micro firms (those

with below nine staff) will be very different to medium sized firms (those with staff numbers between

50 and 249) in relation finance, advice and internal capability. Communicating with micro and small

businesses is notoriously difficult for government, which is just one reason why long-term policies are more

favourable.

Rather than these short term reactions, policy measures should be designed for the long term and aimed

at correcting market failures, institutional failures and reverse adverse policy settings. Three themes give

a view on how public policy should develop; a longer but practical guide for policymakers is found in

Box 4.1. These are:

1. Where the market does not allocate resources to produce the best overall economic outcome

in a liberal market economy. These can be categorised as anti-competitive behaviours,

missing markets or information problems

2. Through undertaking reforms of fundamental business institutions such as the labour market,

taxation, law and business regulations and regulators with a clear focus on the desired long

term outcomes. Governments often spend time and money continually reforming without

setting-out end objectives thus leading to constant uncertainty

3. Where economic agents – both consumers and producers – systematically make misjudgments,

often due to information asymmetries

These three areas cover the macro environment which all small businesses operate in and can have a

massive impact on the growth rate of the SME sector and the health of a modern economy. Economists

now suggest that the legal system in a modern economy can have a major role in the growth rate of

SMEs (OECD 1994). This can be linked to commercial and intellectual property rights and a redress

mechanism for those who operate outside of the law. All fundamental business institutions such as tax, law

and employment policy have a major impact on small firms and as such, governments have pushed and

pulled these levers all too often, and at times in opposite directions.

18

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Box 4.1 Check list for policymakers

For the purposes of this report, we use standard, internationallyrecognised labour

market definitions used by the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

The following provides a guide to policy design drawn from a range of

commentators. It is the ‘check list’ that policymakers should follow when drawing up

new initiatives to support small businesses. If not met, the implication is the proposal

should be dropped.

•Doestheprogramtargettheproblemeectively?

•Doesithaveacceptabletake-up?

•Isittimely?

•Doesitinducenewactivity?

•Arelargetransfersoverseasavoided?

•Doestheprogramhavetherightduration,scaleandtargetgroup?

•IsitadministrativelyecientforGovernment?

•Doesitimposebigcomplianceburdensonrms?

•Isittransparentandaccountable?

•Isitnancedintheleastcostlyway?

•Whataretherisksposedbytheprogramme:

-Strategicbehaviourbyrms?

-UnforeseenliabilitiesforGovernment?

-Adverseinteractionswithotherpolicies?

Source: BIE (1996b), Mortimer (1997), IC (1997e), IC (1997f) and Lattimore (1997)

www.fsb.org.uk

19

The importance of institutions

The UK’s experience with the failed SBS provides a useful counterfactual of where institutional arrangements

are not successful, and where the rhetoric (‘champion of the small business’, ‘thinking small first’) was

set against the cold reality of having an organisation that had responsibility without power. There are

however examples of successful state backed institutions that have operated successfully for many years

to promote small business policies and intervene to address the issues outlines above. Variations between

delivery mechanisms and political oversight are different but all G8 nations apart from the UK have a state

backed institution which supports the financing needs of small businesses. Specific examples include:

•Germany’sKfW, set up in 1948, which aims to provide long term affordable finance to the

Mittlestand. In the year ending 2011, KfW had over €9billion worth of exposure to micro and

start-up German firms. The two main loan products are the KfW Start-Up and KfW Entrepreneur

Loan Programme which together cover most lending requirements; and

•TheJapaneseFinanceCorporation’sSMEunit, which has been in operation since

1999 but existed prior to that through two separate state owned banks (Japan Export-Import

Bank and the Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund). For the year ending 2011, the SME Unit

has lent over ¥20 trillion to small businesses.

As well as these examples, the US SBA provides the best example from which to learn, both from the

scope of its activity, especially its unwavering focus especially on improving access to finance for small

businesses, and its longevity as an institution that has provided an anchor to the US enterprise policy

framework. This is now looked at in more detail, and the case made for a similar institution to be

implemented in the UK.

20

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

The US Small Business Administration

The SBA’s mission is to maintain and strengthen the nation’s economy by enabling the establishment and

vitality of small businesses and by assisting in the economic recovery of communities after disasters. Set up

in 1953, with the passing of the Small Business Act, the SBA’s aim then – as now – is to: “aid, counsel,

assist and protect, insofar as is possible, the interests of small business concerns’’. This highlights an

immediate difference between the SBA and the SBS, which is that the SBS had insufficient teeth to lead

on enterprise support. By comparison, the US SBA had legislative powers from its inception.

By 1954, the SBA was making direct business loans, guaranteeing bank loans to businesses, helping to get

Government procurement contracts for small businesses and helping business owners with management,

and technical assistance and business training.

The initial powers established in 1953 were then given extra scope in 1958 with the Investment Company

Act. This established the Small Business Investment Company Program (SBIC) whose role is to provide

long-term debt and equity investments to high-risk small businesses. Innovative activities were also given

added impetus with the Small Business Innovation Development Act (1982) which saw the creation of

the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program. The other main historical development was the

creation of a network of Small Business Development Centers across the 50 states of the US in 1977

7

.

Tackling excessive federal regulatory burdens and protecting small firms from excessive federal regulatory

enforcement are other important roles played by the SBA. The SBA fulfills these functions through the

offices of Advocacy and the National Ombudsman, again underpinned by legislative powers in the

Regulatory Reform Act 1977. The Office of Advocacy provides an independent voice for small businesses

to advance its views, concerns, and interests before Congress, the federal government, federal courts and

state policymakers. The National Ombudsman receives complaints and comments from small firms and

acts as a “trouble shooter” between small businesses and federal agencies.

The SBA’s portfolio of assistance to US small firms covers three main areas:

1. Access to finance programs:

• 7(a) Loan Program, Capital Access Programs (Surety Bond Program, International Trade

Program), 504 Loans, Microloans, and SBIC loans (see Box 4.2 for more details)

2. Accessing government procurement and contracts:

• The Government Contracting and Business Development (GCBD) program (7(j) Program,

8(a) Program, HUBZone Program, Prime Contract Program, Business Matchmaking,

Subcontracting Program)

3. Business assistance and advice:

• Small Business Development Centers, Women’s Business Ownership, Veteran’s

Business Development`

7 The SBA also plays a significant role in disaster relief. While supporting small businesses is important in the amelioration of

disaster effects, this role is not squarely focused on small businesses. As such, the role of the SBA in disaster relief is not considered

in this report.

www.fsb.org.uk

21

Of these three roles, its primary and consistent focus has been on access to finance issues – the most

important single factor for firms starting up and wanting to grow. This is in comparison to the UK experience

detailed earlier, which highlights the sheer churn of policy initiatives and unnecessary duplication.

Greene and Storey (2010) provide a detailed review of the balance of these activities. They found that

while the SBA did focus on ‘soft’ support (such as advice and assistance) principally through the Small

Business Development Centers, its main role was the provision of ‘hard’ support. Indeed, Craig et al

(2008) identified that in 2004 the SBA’s loan portfolio was worth $60 billion dollars, making “it the

largest single financial backer of small businesses in the United States” (p.118). Largely in response to

recent economic conditions and to support small businesses, this loan portfolio grew to $80 billion by

2011.

In 2010, the SBA spent around $532 million on these programs (Figure 4.1), comparing favourably in

value for money terms against the UK’s total expenditure of around £2.5 billion in 2003/04 noted in

Chapter 2. This funding is split largely between three activities:

• Hard support (financial support to small businesses) of around $204 million (38%);

• Soft support (business advice and assistance) of around $217 million (41%) which is mostly for

existing entrepreneurs through the Small Business Development Center network; and

• Contracting and procurement support of around $112 million (21%).

Indeed, Karen Mills, head of the US SBA, stated in February 2013 that “over the last four years SBA

supported more than $106 billion of lending to more than 193,000 small businesses and entrepreneurs.”

Figure 4.1 US SBA total cost by programme

Source: SBA, 2012: Table 9 – Total cost by program and activity

22

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Greene and Storey (2010) provide another comparison of value for money with the UK. They estimate

that US enterprise support was around $100 per capita less than that of the UK expenditure, suggesting

that part of the reason may be that sheer complexity of UK enterprise support drives up administration

costs. The Richard Report (2008) estimated that these administrative costs represented 34 per cent of

direct enterprise support spending in the UK.

Though the overall impression is favourable, the SBA is not immune from criticism. SBA schemes can be

open to fraud and abuse (DeHaven, 2012). There are also claims – particularly prior to 2008 – that its

loans are a “wasteful, politically-motivated subsidy” (de Rugy, 2006: 3), although these criticisms have

been more muted in the current economic climate.

Default rates on SBA loans have also gone up in the current economic climate, a shift from the historical

position that SBA loans were cost neutral to the taxpayer. US Congress (2011) also noted that there are

signs of a drift by the SBA away from access to finance issues and towards supporting social inclusion

initiatives (soft support). Finally, Greene and Storey (2010) identified a weak evaluation culture with little

robust evidence to indicate that the SBA’s suite of enterprise policies do provide economic returns to the

taxpayer

8

.

Nonetheless, and although these criticisms are important, the sheer longevity of the SBA does mean that

there is a greater likelihood that nascent and actual entrepreneurs will recognise the assistance available.

Equally, protected by legislative powers, the SBA has over a 60 year period followed what appears to

be a stable and coherent suite of enterprise policies, largely focused around the key access to finance

issue. It may be no coincidence that the US has made more finance available to smaller businesses since

2008 (FSB, 2012) and, more generally, outperformed the UK’s GDP growth rate over the last 30 years

(Barrell et al, 2010).

8 Gu et al (2008) outline that very few of the evaluations of US small business programmes actually evaluate these programmes

based on a RCT or a quasi-experimental basis. This means that “few studies are able to identify a causal relationship between

small business assistance programs and business creation and subsequent economic performance of assisted small firms.” (p. 4)

www.fsb.org.uk

23

Box 4.2 US Small Business Administration loan programmes

US Small Business Administration schemes

BanksandotherlendinginstitutionsoeranumberofSBAguaranteedloan

programmestoassistsmallbusinesses.WhileSBAitselfdoesnotmakeloans,it

does guarantee loans made to small businesses by private and other institutions.

How funds may be used

Funds may be used for the following purposes for long term fixed assets:

• Acquisition

• Construction

• Renovation

• Modernisation

• Improvement

• Expansion

7(a) Loan program:

This is the SBA’s primary and most flexible loan programme, with financing

guaranteed for a variety of general business purposes. It is designed for start-

up and existing small businesses, and is delivered through commercial lending

institutions. The major types of 7(a) loans are:

• Express Programs

• Export Loan Programs

• Rural Lender Advantage Program

• Special Purpose Loans Program

CDC/504 Loan program:

This programme provides long-term, fixed-rate financing to acquire fixed assets

(such as property or equipment) for expansion or modernisation. It is designed for

smallbusinessesrequiring“brickandmortar”nancing,andisdeliveredbyCDCs

(CertiedDevelopmentCompanies)—private,non-protcorporationssetupto

contribute to the economic development of their communities.

Microloan program:

This programme provides small (up to $35,000) short-term loans for working

capital or the purchase of inventory, supplies, furniture, fixtures, machinery and/or

equipment. It is designed for small businesses and not-for-profit child-care centres

needing small-scale financing and technical assistance for start-up or expansion,

and is delivered through specially designated intermediary lenders (non-profit

organisations with experience in lending and technical assistance).

International Trade Loan Program:

TheInternationalTradeLoanProgramoersloansforxedassetsandworking

capital to businesses that plan to start or continue exporting or those adversely

aectedbycompetitionfromimportswhichneedtore-tooltobecomemore

competitive. The proceeds of the loan must enable the borrower to be in a better

position to compete. The programme provides the lender with a 90 per cent

guarantee on loans up to $5 million.

Small Business Investment Companies Program (SBIC)

The structure of the programme is unique in that SBICs are privately owned and

managed investment funds, licensed and regulated by SBA, that use their own

capital plus funds borrowed with an SBA guarantee to make equity and debt

investments in qualifying small businesses.

24

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Chapter 5: Conclusion

The aim of this paper has been to provoke a long overdue debate over the direction of UK enterprise

policy. This is needed because for too long, UK enterprise support has been characterised by the

confused, complex and congested delivery of such support. What UK enterprise support requires, and

what international evidence suggests, is the development of a long term and coherent approach to how

it supports small businesses anchored by a single institution.

A UK SBA could bring much needed coherence to these problems and provide that anchor. Admittedly,

as the experience of both the Small Business Service and the US’s SBA shows, there are likely to be

challenges. However, if the UK can learn the lessons from both these experiences and learn by evolution

rather than revolution, the hope would be that past mistakes could be avoided and it would provide

over the longer term real direct benefits to UK small businesses. These lessons can be put to good use

straightaway in the design of the Business Bank.

The central objective for such an institution must be to support a varied access to finance market for

small businesses and tackle market failures under one umbrella body. A UK SBA should bring the good

teachings from the US and other nations such as Germany to promote better practice in the UK. Amongst

the key design principles the new institution should follow are:

• Like the US SBA, and crucially, a UK SBA would need legislative powers. One of the lessons

that can be drawn from the UK’s Small Business Service was that it was given responsibility but

not power to lead on enterprise support, making it very difficult for it to achieve its goals and

ultimately led to its closure. A UK SBA, therefore, would need to have a clear role in and across

government and have sufficient powers to execute this role

• It should focus on a narrow set of activities. This should be in helping small businesses access

finance and act as a promoter for new challenger banks and non-bank routes of finance, by

channeling funding through these groups. It should also look at linkages to exporting schemes

which comprise of both funding and advice natured products (both soft and hard support)

• Be target driven and operated by industry specialists at arm’s length from the Government,

thereby limiting political interference in its operation

• Use the existing retail financial system to offer guarantees and direct micro lending to UK

small businesses with a range of needs, but especially to increase the availability of long term

lending that is noticeable by its absence in the UK market. Pricing of such products should

be competitive but applications should be merit judged on longer term objectives such as

employment, innovation and national objectives (such as carbon reduction targets and increased

exporting activity)

www.fsb.org.uk

25

References

Appleyard, B. (1978) ‘Bringing small business to the Boil’, The Times, Monday, 2nd October, p. 16.

Audit Commission 1999. A Life’s Work: Local Authorities, Economic Development and Economic

Regeneration. London: Audit Commission.

Audretsch, D. and Thurik, R. (2004) ‘A Model of the Entrepreneurial Economy’, Discussion Papers on

Entrepreneurship, Growth and Public Policy, Max Planck Institute, 1204.

BCC (2012) The Case for a British Business Bank, London: BCC.

BIS (2011) Business population estimates for the UK and regions 2011, October.

BIS (2012a) Business Support Finder http://improve.businesslink.gov.uk/resources/business-support-

finder (accessed 2nd October, 2012).

BIS (2012b) Business Journey Planner, http://www.bis.gov.uk/assets/biscore/corporate/docs/b/

business-support-journey-planner.pdf (accessed 2nd October, 2012).

Bakhshi, H., Edwards, J., Roper, S., Scully, J. and Shaw, D. (2011) Creating Innovation in Small and

Medium-sized Enterprise: Evaluating the short term effects of the Creative Credits Pilot. London: NESTA.

Bank of England (2003) Finance for Small Firms – An Tenth Report, Bank of England: London.

Barrell, R., Holland, D. and Liadze, I. (2010) Accounting for UK economic performance 1973-2009,

NIESR Discussion Paper, http://www.niesr.ac.uk/pubs/searchdetail.php?PublicationID=2684.

Beesley, M.E. and Wilson, P.E.B. (1984) ‘Public Policy and Small Firms in Britain’, in Small Business:

Theory and Policy, Levicki, C. (ed.), London: Croom Helm, 111-126.

Bennett, R. J. (2008) Government SME policy since the 1990s: what have we learnt? Environment and

Planning C: Government and Policy, 26, 375-397.

Bennett, R. J. (2010) Using the Relation Between Business Associations and SMEs as a Policy Tool: From

History to LEPs, ISBE Conference, Sheffield.

Bennett, R. J. (2012) Government Advice Services in SMEs: Some Lessons from British Experience, in

Blackburn, R.A. and Schaper, M.T. (eds.) Government, SMEs and Entrepreneurship Development, 195-

210.

Benus, J. M. (1994) ‘Self-employment Programmes: A New Reemployment Tool’, Entrepreneurship Theory

and Practice, 19:2, 73-86.

Birch, D. (1979) The Job Generation Process, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Program on Neighborhood and

Regional Change.

Blackburn, R.A. (2012) Segmenting the SME Market and Implications for Service Provision: A Literature

Review, Research Paper, 09/12, London: ACAS.

Boswell, J. (1973) The Rise and Decline of Small Firms, London: George Allen and Urwin.

Cowling, P., Bates, P., Jagger, N. & Murray, G. (2008) Study of the impact of the Enterprise Investment

Scheme (EIS) and Venture Capital Trusts (VCTs) on company performance, HM Revenue & Customs

Research Report 44, London: HMRC.

Craig, B., Jackson, W., & Thomson, J. (2008). Credit market failure intervention: Do government

sponsored small business credit programs enrich poorer areas? Small Business Economics, 30(4), 345-

360.

Cumming, D. (2007) Government policy towards entrepreneurial finance: Innovation investment funds.

Journal of Business Venturing, 22(2), 193-235.

26

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Curran (1993) TECs and Small Firms: Can TECs Reach The Small Firms Other Strategies Have Failed To

Reach? Kingston University.

Curran, J. and Blackburn, R.A. (1990) ‘Youth and the enterprise culture’, British Journal of Education and

Work, 4:1, 31-45.

Curran, J. and Blackburn, R.A. (2000) ‘Panacea or White Elephant? A critical examination of the

proposed new small business service and response to the DTI consultancy service’, Regional Studies,

34(2): 181-206.

Brown, R and Mason, C. (2012) The Evolution of Enterprise Policy in Scotland, in Blackburn, R.A. and

Schaper, M.T. (eds.) Government, SMEs and Entrepreneurship Development, 17-32.

CBI (2010) SME Council paper Enterprise Policy Framework, London: CBI.

DeHaven, T. (2012) Waste, Fraud, and Abuse in Small Business Administration Programs, Cato

Institute, http://www.cato.org/publications/congressional-testimony/waste-fraud-abuse-small-business-

administration-programs.

de Rugy, V. (2006) Why the Small Business Administration’s Loan Programs Should Be Abolished,

Washington: American Enterprise Institute, WP #126.

Department of Trade and Industry/HM Treasury (2002) Cross Cutting Review of Government Services for

Small Business, London: Department of Trade and Industry/HM Treasury.

Department of Trade and Industry 2007. Simplifying Business Support: A Consultation. London:

Department of Trade and Industry.

Daly, M., Campbell, C., Robson, G., and Gallagher, C. (1991) ‘Job Creation 1987-89: The Contributions

of Small and Large Firms’, Employment Gazette, November, 589-596.

Davidsson, P., Lindmark, L. and Olofsson, C. (1998) The extent of overestimation of small firm job

creation - an empirical examination of the regression bias. Small Business Economics, 11(1), 87-100.

Disney, R. Haskel, J and Heden, Y. (2003) ‘Restructuring and Productivity Growth in UK Manufacturing’,

Economic Journal, 113, 666-694.

Doyle, J. and Gallagher, C. (1987) ‘Size Distribution, Growth Potential, and Job-Generation Contribution

of UK Firms’, International Small Business Journal, 6:1, 31-56.

FSB (2012) Alt+ Finance, London: FSB.

Fairlie, W.R. (2011) The Great Recession and Entrepreneurship, Kauffman/ Rand Institute for

Entrepreneurship Public Policy, January, WR-822-E.

Fraser, S. and Greene, F.J. (2006) ‘Are Entrepreneurs Eternal Optimists or do they ‘Get Real’’, Economica,

73: 290, 169-192.

Foreman-Peck, J. (2010) Effectiveness and Efficiency of SME Innovation Policy, ISBE Conference.

Freel, M.S. (2000) ‘Do small innovating firms outperform non-innovators?’, Small Business Economics,

14:3, 195-210.

Gavron, R., Cowling, M., Holtham, G. and Westall, A. (2000) The Entrepreneurial Society, IPPR:

London.

Gorg, H. & Strobl, E. (2007) ‘Do Government Subsidies Stimulate Training Expenditure? Microeconometric

Evidence from Plant-Level Data’, Southern Economic Journal, 72(4). 860-876.

Greene, F.J. (2002) ‘An Investigation into Enterprise Support For Younger People, 1975-2000,

International Small Business Journal, 20:3, 315-336.

www.fsb.org.uk

27

Greene, F.J. and Storey, D.J., (2004) ‘The Value of Outsider Assistance in Supporting New Venture

Creation by Young People’, Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 16:2, 145-159.

Greene, F.J., Mole, K.F. and Storey, D.J. (2008) Three Decades of Enterprise Culture: Entrepreneurship,

Economic Regeneration and Public Policy, London: Palgrave.

Greene, F.J. and Storey, D.J. (2010) ‘Entrepreneurship and Small Business Policy: Evaluating its Role

and Purpose’, in Coen, D., Grant, W. and Wilson, G. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook on Business and

Government, Oxford: OUP, 600-621.

Greene, F.J. (2012) ‘Should the focus of publicly provided business assistance be on start ups or growth

businesses?’, Ministry of Economic Development Occasional Paper, MED: Wellington: New Zealand.

http://www.med.govt.nz/about-us/publications/publications-by-topic/occasional-papers/2012-

occasional-papers/business-assistance.pdf

Gu, Q., Karoly, L.A. and Zissimopoulos, J. (2008) Small Business Assistance Programs in the United

States: An Analysis of What They Are, How Well They Perform, and How We Can Learn More about

Them, WR-603-EMKF.

House of Commons Business, Innovation and Skills Committee (2011) Government Assistance to Industry,

Third Report of Session 2010–11, HC 561.

House of Commons Public Accounts Select Committee (2007) Supporting Small Business, Eleventh Report

of Session 2006–07, HC 262.

Hughes, A. (2009) Hunting the Snark: Some reflections on the UK experience of support for the small

business sector, Innovation: management, policy & practice, 11: 114–126.

Joseph, K. (1976) Stranded on the Middle Ground?: Reflections on Circumstances and Policies, London:

Centre for Policy Studies.

Klapper, R., Biga-Diambeidou, M. And Lahti, A.H. (2012) ‘Small Business Support and Enterprise

Promotion: The Case of France’, in Blackburn, R.A. and Schaper, M.T. (eds.) Government, SMEs and En

trepreneurship Development, 131-148.

Lovering, J. (1999) ’Theory led by policy: the inadequacies of the `New Regionalism’ (illustrated from the

case of Wales)’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 23, 379-395.

Lattimore, Madge, Martin Mills (1998) Design principles for small business programs and regulations

Lerner, J. (1999) ‘The Government as Venture Capitalist: The Long Run Impact of the SBIR Programme’,

Journal of Business, 72:3, 285-318.

Meager, N., Bates, P. and Cowling, M. (2003) ‘An Evaluation of Business Start-Up Support for Young

People’, National Institute Economic Review, 186, October, 70-83.

Mole, K., Hart, M., Roper, S. and Saal, D. (2008) ‘Differential gains from business link support and

advice: A treatment effects approach’, Environment and Planning C-Government and Policy, 26(2), 315-

334.

Morris, M. and Stevens P. (2010) ‘Evaluation of a New Zealand business support programme using firm

performance micro-data’, Small Enterprise Research, 17:1, 30-42.

Morris, D. J. and Stout, D. (1985), “Industrial Policy”, in D. J. Morris (ed.), The Economic System in the

UK. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 851-894.

National Audit Office (NAO) (2006) Supporting Small Business, Report by the Comptroller and Auditor

General, HC 962 Session 2005-2006, 24 May.

28

ENTERPRISE 2050 / Getting UK enterprise policy right

Neumark. D., Wall, B. and Zhang, J. (2008) ‘Do Small Businesses Create More Jobs? New Evidence

for the United States from the National Establishment Time Series’, IZA DP 3888, Forschungsinstitut zur

Zukunft der Arbeit: Bonn.

OECD (2008) Entrepreneurship Review of Denmark, Paris: OECD.

OECD (2012) Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2012, Paris: OECD.

Oh, I., Lee, J. D., Heshmati, A. and Choi, G. G. (2009) ‘Evaluation of credit guarantee policy using

propensity score matching’, Small Business Economics, 33(3), 335-351.

PACEC (2005) Small Business Service Mapping of Government Services for Small Business Final Report,

Cambridge: PACEC.