SUSTAINING COLOMBIANS

THROUGH THE ENTREPRENEURIAL

PIPELINE – A POLICY CHALLENGE

FOR COLOMBIA?

Lois Stevenson Rodrigo Varela Jhon Alexander Moreno

INTRODUCTION

The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) is the

largest global study of entrepreneurship. GEM

started in 1999 with 10 participating countries

and in 2013 covered 70 countries. Whereas most

small and medium enterprise (SME)-related

studies and data collection efforts focus on firms,

GEM focuses on the attitudes, activities and

characteristics of individuals who participate in

the various phases of entrepreneurship. The

objectives of the GEM research are to: (1)

measure differences in the level of

entrepreneurial activity between countries; (2)

uncover factors determining the level of

entrepreneurial activity; and (3) identify policies

that may enhance the level (and quality) of

entrepreneurial activity at the national level.

The “GEM Caribbean” initiative

(www.gemcaribbean.org) is a four-year project,

supported by Canada’s International

Development Research Centre (IDRC), to

establish, train and strengthen entrepreneurship

research teams in Barbados, Belize, Colombia,

Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad & Tobago. The

research by these teams applies the GEM

methodology to measure the levels, underlying

factors, and environmental constraints of

entrepreneurship within each national

environment, and comparatively within the region.

The project seeks to provide policymakers with a

stronger empirical foundation to inform actions

and monitor progress in the promotion of

entrepreneurship and job creation in the

Caribbean.

This policy brief is based on findings from the GEM

research studies in Colombia conducted by the

Colombian National Team represented in the GEM

Caribbean project by the Centro de Desarrollo del

Espíritu Empresarial of the Universidad ICESI. It is

further informed by an analysis of national level

policies, programmes and initiatives aimed at

supporting the development of entrepreneurship

and micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in

Colombia.

At a glance – Key findings:

-Colombia compares very favourably with other

efficiency-driven economies on positive attitudes of the

adult population towards entrepreneurship, the level of

confidence Colombians have in their abilities to start and

run a business, their perception of good opportunities to

start a business and their low fear of failure.

-It outperforms the average for efficiency-driven

economies on the rate of early-stage entrepreneurial

activity, but the lower ratio of new business owners to

established business owners is troublesome, since the rate

of established business ownership has been on the decline

for the past three years.

-Gender gaps in entrepreneurial activity exist throughout

the pipeline.

-Although early-stage enterprises are relatively innovative

in terms of their products and competitor markets, the vast

majority are employing old technologies. The level of

innovativeness is greater than in established businesses.

-There are several weaknesses in the framework conditions

for entrepreneurship, although some improvements in

experts’ assessment of these are noted over the past eight

years, possibly due to advancements in government policies

and programmes since 2006 and 2009

Major policy recommendations

•Accelerate the integration of entrepreneurship and new

enterprise creation skills as core curricula in all levels of the

educational system, including across university

programmes.

•Establish Centers for Entrepreneurship Development in all

regions of Colombia, especially to support potential,

nascent and new entrepreneurs.

•Ensure that start-ups and young businesses have access

to financing to properly capitalise their enterprises and fund

their activities, including technology acquisition.

•Encourage entrepreneurs to pursue higher value added

business opportunities.

•Include the targeting of women entrepreneurs in the

National Entrepreneurship Policy and articulate specific

programmes to ensure that they have equal access to

opportunities, financing, business support, mentoring and

networks..

2

Prepared by Lois Stevenson with input from Rodrigo

Varela, Leader of the GEM project at the Universidad

ICESI, and Jhon Alexander Moreno. This policy brief and

the full GEM reports can be found

at:www.gemcaribbean.org

The GEM Caribbean initiative is supported by the

International Development Research Centre (IDRC),

Canada.

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF

CONTEXT FOR

ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN

COLOMBIA

World Development Indicators database 2014, World Bank.

Workforce data is from the Economic Census of 2005, and export data for

2003, the latest available in Colombia.

“Comportamiento del Mercado Laboral por Sexo, Trimestre Abril-Junio de

2014, Boletin de prensa, Departamento Administrativo Nacional de

Estadística/DANE.

Informal MSMEs are constrained by lack of management capacity and access

to formal sources of financing and other governmental support mechanisms.

Colombia is an upper-middle income country of

48.3 million inhabitants with gross domestic

product (GDP) per capita of USD 11,890. It is

classified by the World Economic Forum as an

efficiency-driven economy. MSMEs are an

important segment of the economy, accounting

for 40% of GDP, over 80% of the workforce, and

13% of exports (OECD, 2014 ).

However, by OECD standards, Colombia has an

extremely high level of income inequality and

relative poverty (Joumard and Londoño Vélez,

2013). The unemployment rate in July 2014 was

9%, but higher for women than men (11.6% versus

7%). In fact, women accounted for 55% of the

unemployed, although they make up 43.2% of the

active labour force. A very large share of the

economy is informal, comprising 50-70% of

employment (Joumard and Londoño Vélez, 2013).

3

The MSME sector in Colombia exhibits a low level

of productivity and competitiveness. According to

the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Tourism

(MinCIT, 2009), there are several contributing

factors:business informality ; the high costs and

time required to deal with the red tape for doing

business; difficult access to financing; limitations

on market access; little access to new technology;

lower protection of property rights; low levels of

innovation; underdevelopment of entrepreneurial

skills; reluctance to share ownership of the

company; and limited interagency coordination.

The National Development Plan 2011-2014

recognises the importance of MSMEs and

entrepreneurship to the country’s

socio-economic development and stipulates

policies and actions to create “a competitive

environment that transforms ideas into

businesses, the businesses into jobs, jobs into

higher income, and, thus, less poverty and greater

wellness and social progress” and to support the

development of high value-added and innovative

products and services that can compete in

international markets (DNP, 2011).

The mandate for entrepreneurship and MSME

development rests with the Ministry of Trade,

Industry and Tourism (MinCIT) and is governed by

Law 590/2000 on promoting development of

MSMEs, amended by Law 905/2004, and Law

1014/2006 on promoting a culture of

entrepreneurship. The existence of these laws

indicates the level of importance placed by the

government on creating the conditions conducive

to MSME and entrepreneurship development and

addressing obstacles to enterprise creation and

growth. The National System for the Support and

Promotion of MSMEs, created in 2004, is

responsible for articulating public policy toward

MSMEs. It is comprised of a range of public and

private actors, financial and non-financial entities,

and various programmes, laws and procedures,

and is assisted in the design and formulation of

MSME promotion policies through the Council of

Microfirms and the Council of Small and Medium

Firms. These laws and policies have been

complemented by a number of other laws and

regulations to develop seed capital funds, the

National System of Creation and Business

Incubation, INNpulsa and other regional and

national entities.

The MinCIT also implements the National

Entrepreneurship Policy (see MinCIT, 2009). This

policy framework focuses on three pillars: (1)

facilitating the formal initiation of businesses, (2)

promoting access to funding for entrepreneurs

and start-ups, and (3) promoting interagency

coordination for the promotion of

entrepreneurship. The policy also seeks to

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF

Colombians hold very positive

perceptions and attitudes towards

entrepreneurship

4

address the promotion of "non-financial" support

to entrepreneurs from conceptualisation of their

business idea to its implementation and to

promote ventures that incorporate science,

technology and innovation.

One of the limitations in developing appropriate

policy for entrepreneurship development in

Colombia has been the lack of up-to-data on

MSMEs and on the sector’s performance trends.

Since 2006, a new source of credible data on

entrepreneurial activity and the nature and

characteristics of entrepreneurship for Colombia

has been available, the outcome of a decision of

the Consortium of four universities: Universidad

ICESI, Universidad del Norte, and Universidad de

los Andes, and Universidad Javeriana, to join the

GEM research project. The aim was to have

better information about the situation in

Colombia and to be able to compare Colombian

data with other countries, regions and types of

economies. The Consortium has produced eight

national reports, several regional reports and

some special topic reports. The findings of these

studies offer important policy implications for the

government of Colombia and other stakeholders

in the entrepreneurship eco-system and have

become an important evidence base for

entrepreneurial policies in Colombia. This policy

brief presents selected results and policy

implications from the GEM Colombia project.

The GEM Colombia findings reveal that social

perceptions towards entrepreneurship are very

high - close to 90% of Colombian adults hold the

view that entrepreneurship is a good career choice

- and these favourable perceptions have

sustained over time. They are also the highest of

any GEM country.

Globally, GEM research finds that, relative to the

general adult population, individuals who are

involved in early-stage or established businesses

tend to be more confident in their own skills to be

able to start and manage a business, are more

alert to the existence of unexploited opportunities,

and are less likely to allow the fear of failure to

prevent them from starting a new venture. These

are among the factors that contribute significantly

to shaping an individual’s entrepreneurial

“mindset” (Arenius and Minniti, 2005), and, thus,

indicators of the potential level of entrepreneurial

capacity in a country.

Almost 60% of Colombian adults believe that they

have the skills and abilities to start and run their

own business. Although down from 68% in 2006,

this skills indicator is very positive for Colombia

because, according to GEM global studies,

individuals who are confident in their skills to start

a business are four to six times more likely to be

involved in entrepreneurial activity.

Over two-thirds of the Colombian adult population

see good opportunities available to start a

business “in the next six months”, and report that

the fear of failure would not prevent them from

starting a business (although down from 75% in

2006). This suggests a large pool of potential

entrepreneurs (Varela et al., 2014a).

Copies of the national GEM reports for Colombia can be accessed online at:

http://www.gemconsortium.org/docs/cat/4/national-reports/;

http:www.gemcolombia.org /publicaciones/; and http:www.gemcaribbean.org

/publications/

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF

Entrepreneurial activity rates are

high, but vary from year to year

Fig. 1. Pipeline trends in entrepreneurial activity

levels, 2006-2013

5

These positive perceptions and attitudes towards

entrepreneurship are reflected in a comparatively

high expression, in 2013, of intent to start a

business within the next three years (54.5% of

adults in Colombia versus an average of 24.8% of

adults across efficiency-driven economies)

(Amorós and Bosma, 2014).

Colombian adults indicate a high level of

entrepreneurial orientation. In 2006 and 2008,

almost 100% of adults reported some level of

attachment to entrepreneurial activity, with 60%

or more of them intending to start a business

within the next three years, and up to 26%

already owning a young (less than 42 months old)

or an established business (more than 42 months

old). However, there are some interesting trends

in the entrepreneurial pipeline that are worthy of

attention.

2006

20% 40% 60% 80%

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

Intending to start a business in the next three years

Trying to get a new business started (nascents)

owns a ner/ young business (<42 months)

Owns an established business (>42 months)

Since 2010, the level of intention to start a

business (while still higher than in most GEM

countries) has been declining, although the

percentage of adults actively trying to get a new

business started (nascent entrepreneur) has

remained relatively stable at about 14%. In 2013,

there were 1.32 adults trying to start a business

for every adult who already owned a new

business that was less than 42 months old. This is

about average for efficiency-driven economies,

but lower than the average for Latin American

countries (1.68:1), suggesting a smaller pipeline of

nascent entrepreneurs relative to the stock of

new enterprises.

Of some concern is the declining percentage of

adults with an established (mature) business,

dropping to 6% in 2013, compared to a high of 14%

in 2008. In 2013, Colombia ranked 4th among 28

efficiency-driven economies on the rate of

early-stage entrepreneurial activity and well

above the average of 14.4%, but dropped to 15th

in the ranking on the established business

ownership rate, well below the average of 8.0%.

The declining established business ownership

rate could suggest that new business owners are

having increasing difficulty with survival rates, so

fewer of them are lasting in the market for more

than 42 months.

To address these declining trends, the

government would be well placed to focus on

stronger promotion to encourage more

Colombians to actively pursue entrepreneurship

(convert those with intent to the nascent stage)

while at the same time promoting stronger

start-ups by encouraging and facilitating

innovative enterprises that are able to compete

more effectively in the marketplace, and ensuring

that nascent and new entrepreneurs are able to

access the support they need to successfully

launch a sustainable enterprise.

Early-stage entrepreneurial activity is inclusive of adults trying to get a

business started (nascent entrepreneurs) and the owners of a new business

that is less than 42 months old.

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF

Age and education matter to the

level of entrepreneurial activity

Relatively large gender gap in

entrepreneurial activity rates...

Fig. 2. Entrepreneurial activity rates vary by age

group

6

GEM studies find that early-stage entrepreneurial

activity rates tend be highest among the younger

age groups (under 35 years of age). This is also

the case in Colombia, although the level of

entrepreneurial activity across age groups has

varied by year. An interesting development in

2013 is the shift to the highest entrepreneurial

activity rate among adults in the 35-44 age group

(31%), compared to a national average of 24%.

Also of note is the growing tendency, since 2009,

of 18-24 year olds to be engaged as early-stage

entrepreneurs (from 15% to 23%).

In general, entrepreneurial activity rates increase

with levels of education. For example, GEM

reports find that university graduates have a

much higher entrepreneurial activity prevalence

rate than adults with no formal education or only

a primary school level education. This is also true

for Colombia. In 2013, over 30% of the adult

population with a tertiary level of education was

engaged in early-stage entrepreneurial activity,

compared to 17-18% of those with a secondary or

primary level education (Varela et al., 2014).

Among adults with no formal education, only 5%

were involved.

Since more highly educated adults have a greater

probability of developing growth businesses, one

of the policy objectives in Colombia should seek to

integrate entrepreneurship in a cross-disciplinary

manner across the education system with a focus

on secondary, technical and university education

programmes. This is important given that

individuals who have been exposed to

entrepreneurship education and training tend to

have higher start-up and survival rates, as well as

growth ambitions.

10%

2006

20.0%

18-24

25-34

35-45

46-54

55-64

27.0%

26.0%

21.0%

11.0%

22.0%

26.0%

24.0%

22.0%

9.0%

18.0%

32.0%

29.0%

22.0%

12.0%

15.0%

27.0%

26.0%

22.0%

17.0%

16.7%

26.9%

23.2%

18.3%

12.0%

19.7%

26.9%

23.2%

20.1%

12.1%

21.0%

25.0%

23.0%

17.0%

8.0%

23.0%

26.0%

31.0%

21.0%

14.0%

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

Across GEM countries, the early-stage

entrepreneurial activity rates for adult women are

generally lower than for men, which is also the

case in Colombia. In 2013, 30% of adult males were

trying to start a business or owned a new/young

business compared to about 17% of adult females,

and only 4% of females owned an established

business, compared to 8% of males. The gender

gap of 13 percentage points in early-stage

entrepreneurial activity rates between males and

females is almost twice the average for Latin

American and Caribbean (LAC) countries. The

male-to-female ratio for Colombia has averaged

about 1.5:1 since 2006, but rose to 1.76:1 in 2013,

which was the second largest gender gap in the

LAC after Suriname.

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF

…plus qualitative differences in

female entrepreneurial activity

Graphic 1. Entrepreneurial pipeline Colombian

male 2013

Graphic 2. Entrepreneurial pipeline Colombian

female 2013

Table 1. Gender differences in entrepreneurial

activity levels

7

Over the past eight years, women have

accounted for an average of about 40% of the

Colombian adults trying to get a business started

or owning a new business (but dropped to 36% in

2013), which is lower than the female share of the

Colombian labour force.

However, the level of entrepreneurial orientation

of females starts from a smaller base (intention

rate) and progressively continues to diminish,

relative to males, throughout the entrepreneurial

pipeline.

75% 69% 61%

18%14%8%

Colombian male

2013

78% 60%

60%

10%7%4%

Colombian famale

2013

In 2013, males were 1.25 times more likely than

females to intend to start a business; 1.75 times

more likely to be a nascent entrepreneur; 1.82

times more likely to be a new business owner; and

2.1 times more likely to be an established business

owner (Varela et al., 2014b). The bottom line is

greater leakage of women than of men from

various phases of the entrepreneurial pipeline. For

example, while there is one male nascent

entrepreneur to every 3.5 males with the intent to

start a business, there are almost five adult

females with the intent to every one trying to start

a business. This phenomenon suggests that policy

initiatives are required to address the barriers

faced by women in moving through the

progressive stages of entrepreneurial activity.

Colombian policymakers should also consider

certain key qualitative differences in male and

female entrepreneurial activity. Across countries,

GEM data reveal that a lower percentage of adult

women than men have confidence in their skills

and ability to start and run a business and a

Women make up about 43% of the economically-active population in Colombia

(“Comportamiento del Mercado Laboral por Sexo, Trimestre Abril-Junio de

2014, Boletin de prensa, Departamento Administrativo Nacional de

Estadística/DANE, p. 2).

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF

61.1%

48.9%

1.25:1

17.5%

10.0%

1.75:1

0.28:1

0.20:1

1.4:1

13.5%

7.4%

1.82:1

0.77:1

0.74:1

1.04:1

7.9%

3.9%

2:1%

0.58:1

0.53:1

1.1:1

Adult males

(M)

Ratio

(M F)

Adult famales

(M)

Colombian early-stage ventures

outperform the LAC average on

indicators of “innovativeness”…

….but are weak on the use of new

technologies

Assessment of the Entrepreneurial

Environment

8

higher percentage indicate that fear of failure

would prevent them from starting a business

(Kelley et al., 2013). This is also the case in

Colombia where about half of adult women

consider that they have the knowledge and skills

required, compared to two-thirds of adult men.

For more than a third of women, fear of failure

would prevent them from starting a business,

compared to less than 30% of men.

Women are also more likely than men to be

motivated to start a business out of necessity

than to pursue a good business/market

opportunity (Kelley et al., 2013); in the case of

Colombia, twice as likely to be motivated out of

necessity (27% of women entrepreneurs versus

13% of male entrepreneurs). In addition, female

owners of both new and established businesses

are much less likely than men to have employees

and also report lower job growth aspirations for

their businesses. Most critically, Colombian women

with established business (more than 42 months

old) are much less likely than men to create jobs

for others – 53% versus 83%, the largest gender

gap in LAC countries and one of the highest across

all GEM countries (Kelley et al., 2013).

The National Entrepreneurship Policy (MinCIT,

2009) does not identify the development of

women entrepreneurs as a priority nor make any

provision for policies and programmes to improve

their level of participation in entrepreneurial

undertakings. Propositions for the Colombian

government suggested from the GEM data, and

supported by findings from Powers and Magnoni

(2013), are to direct assistance to help create

women-owned businesses and scale-up the

activities of women’s existing micro or small

enterprises, with a focus on training in

entrepreneurship and business management,

technical assistance, support for formalisation,

mentoring, exposure to successful role-models,

the creation of business networks, and access to

financing

In 2013, 80% of the early-stage entrepreneurs in

Colombia reported that their products/services

would be perceived as new by some or all of their

customers, compared to an average of about 40%

of the early-stage entrepreneurs across LAC

countries. In addition, 55% indicated that few or no

other businesses offered the same products,

compared to the LAC average of almost 45%. It is

also promising that early-stage ventures

consistently display higher levels of innovativeness

in their product/service offerings than established

businesses and are more likely to be operating in

markets with few or no competitors.

The one innovation-related area where

Colombians are very weak is in the use of the

latest technologies. Almost 90% of the early-stage

entrepreneurs are using old technology (more

than 5 years old) and only 1.3% are making use of

the latest technology (less than 1 year old). Either

they are unaware of the latest technologies or do

not have sufficient financing to acquire these. In

any case, this issue is one that may require policy

attention, as the level of technology used in an

enterprise can have a dramatic impact on its

productivity and competitiveness.

GEM also measures the strength of the

Entrepreneurial Framework Conditions (EFCs)

associated with influencing the environment for

entrepreneurial activity

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF

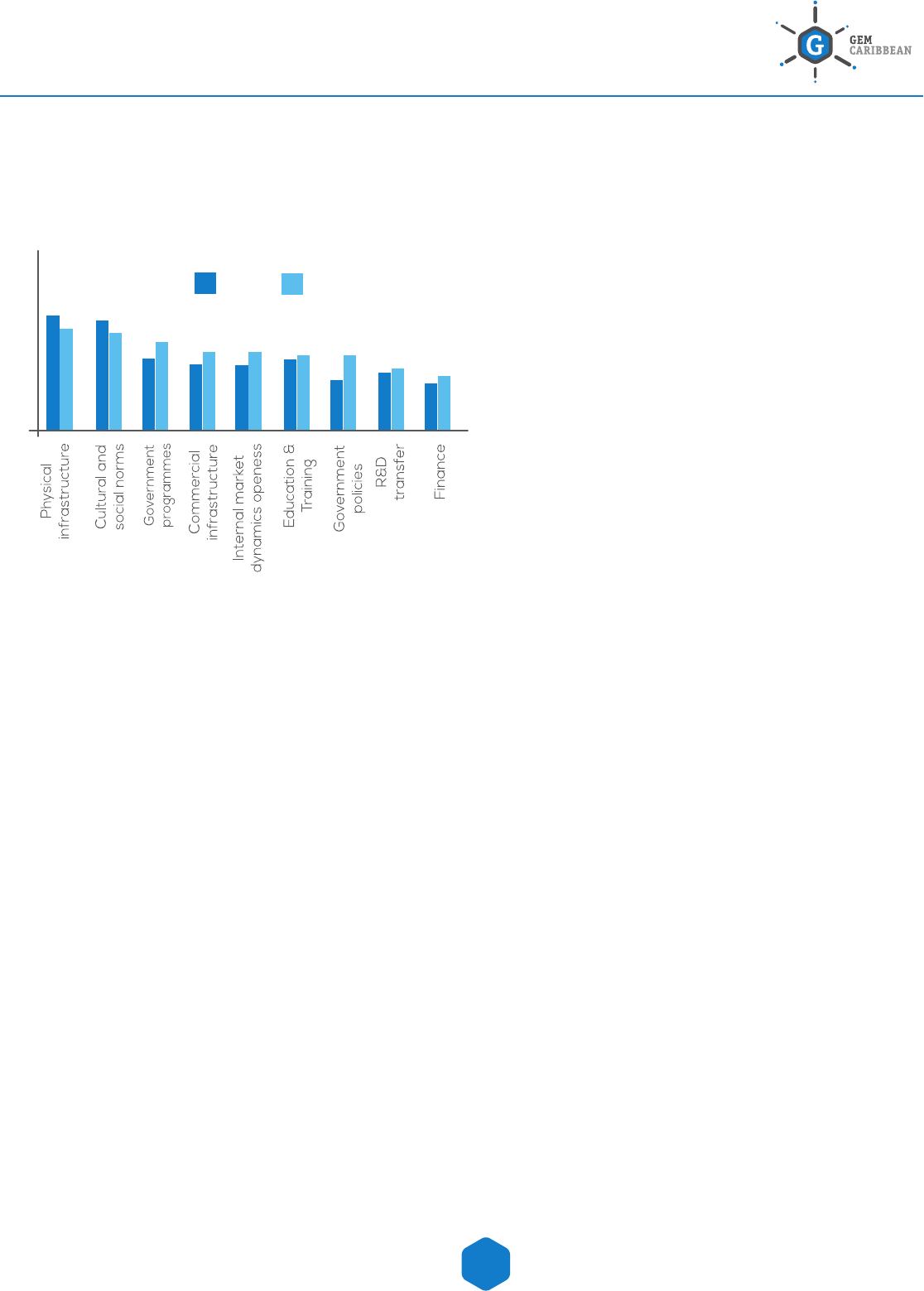

Fig 4. Assessment of the Entrepreneurial

Environment

In 2013, national experts in Colombia assessed the

physical infrastructure in the country as the

strongest EFC (3.3 out of 5), followed by cultural

and social norms (relative to fostering

entrepreneurial attributes and attitudes) (3.1), and

government programmes (3.0). The weakest

assessments were given to R&D transfer (2.4 out

of 5) and access to finance (2.3). Except for

finance, the national experts in Colombia viewed

the EFCs in a more favourable way than the

average for the LAC and efficiency-driven

economies. This was especially with respect to

government programmes, national policy support,

and the internal market dynamics/ openness.

However, only three of the nine EFCs achieved a

mean score of 3 or more out of 5, suggesting

general weaknesses in the environment for

entrepreneurship.

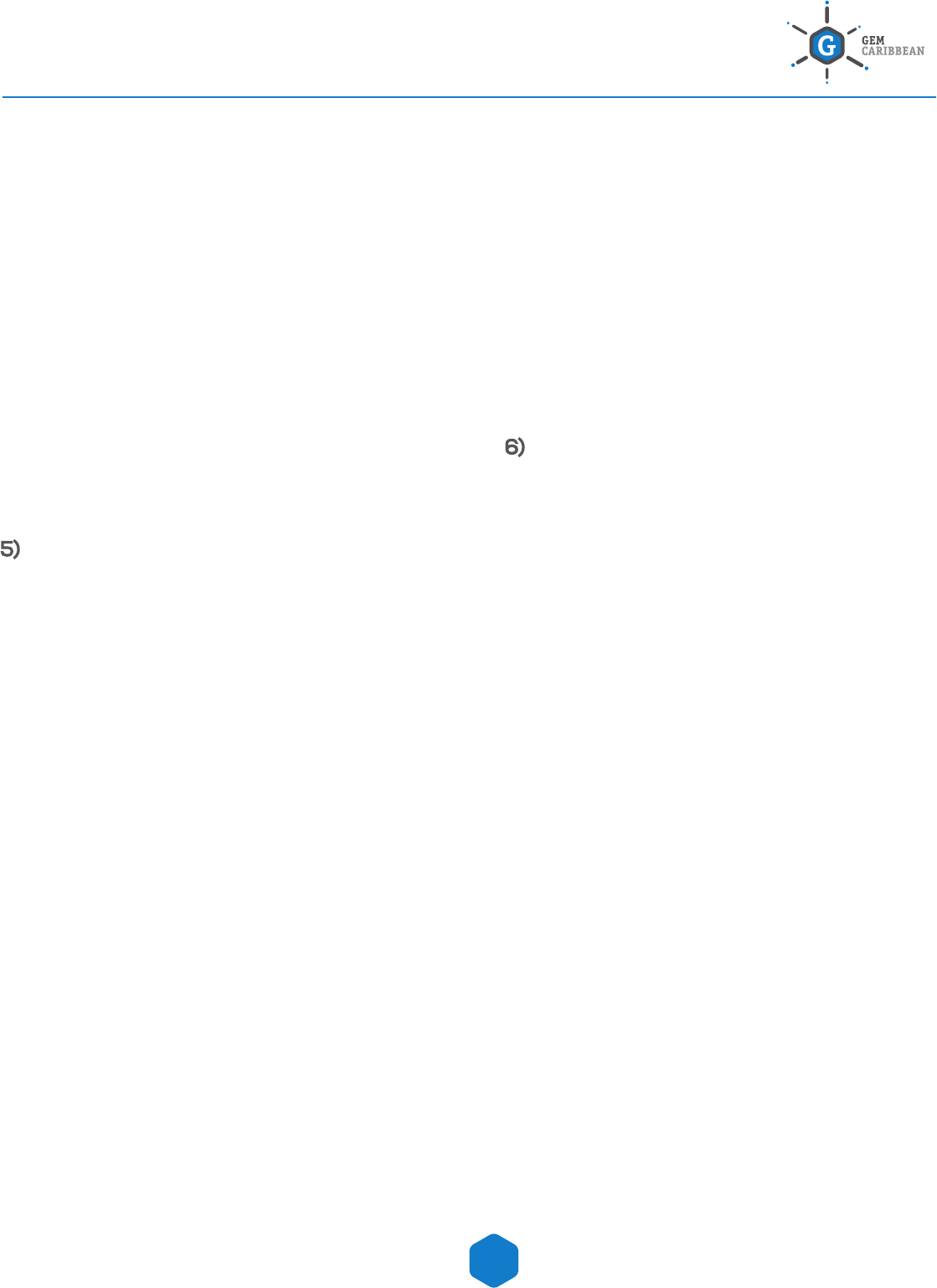

On the other hand, there has been an

improvement in national experts’ views on the

strengths of several of the EFCs in Colombia from

2006 to 2013. The largest gains are in

government policies and programmes favouring

entrepreneurship, with increases in the average

scores of 27% and 16% respectively.

Improvements in experts’ views on government

policies and programmes likely reflect increased

government efforts since 2006.

Experts’ views also reflected improvements in

their assessment of the financing EFC, but this is

still seen as the weakest EFC in terms of meeting

the needs of new and growing firms. The “Index of

Systemic Conditions for Dynamic

Entrepreneurship” also reinforces that the supply

of funds for entrepreneurs is inadequate,

particularly presenting an obstacle for start-ups

(Kantis et al.,2014). Although Colombia is believed

Colombia

LAC countries

Efficiency - driven economies

to have one of the most developed venture

capital ecosystems in the LAC, early-stage

venture capital, seed and angel investing is still

underdeveloped.

9

The presence and quality of government programs directly assisting MSMEs.

Market openness is defined as the extent to which new and growing firms are

free to enter and compete in existing markets.

Ease of access to utilities, communications, transportation, land or space at a

price that does not discriminate against MSMEs.

Note: Based on results of the National Experts Survey: 5=strong agreement with the

set of statements regarding the adequacy of the Entrepreneurial Framework

Condition; 1=strong disagreement with the statements.

Physical

infrastructure

R&D

transfer

National policy

supportive of

entreprenreurship

Commercial

infrastructure

Cultural and

social norms

Finance

Government

programmes

Internal market

dynamics

openess

Entrepreneurship

education

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

AND RECOMMENDA-

TIONS

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

20132006

Colombia compares well with LAC and

efficiency-driven economies on societal attitudes

towards entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial

capacity perceptions of the adult population,

intentions to become entrepreneurs, and

early-stage entrepreneurial rates, but there are

areas in need of policy attention.

One of the major entrepreneurship policy issues is

leakage in the entrepreneurial pipeline,

particularly the conversion of adults with the

intention to start a business to nascent

entrepreneurs and of nascent entrepreneurs to

new business owners. This issue may be

addressed by integrating entrepreneurship as a

component of all educational programmes, so as

to both strengthen the culture of

entrepreneurship and build the level of practical

knowledge and skills in becoming an entrepreneur,

and ensuring that potential and nascent

Fig. 5. Change in national experts' views on

strengths of Colombia's Entrepreneurial

Framework Conditions, 2006 versus 2013

entrepreneurs have access to a system of support

to help them overcome obstacles they might face

in developing their enterprises. The level of

entrepreneurial activity through the

entrepreneurial pipeline could also be enhanced by

addressing gender gaps between women and

men.

The diminishing ratio of established to new

business owners is also a key policy concern, which

may be remediated by providing post-creation

support to new enterprises with the aim of

increasing their sustainability rates.

Another policy issue is maintaining a high level of

innovation among early-stage ventures since

significant value is associated with new products

and new markets. Particularly crucial are actions to

improve the technological level and

competitiveness of Colombian enterprises. This

could be achieved by introducing creativity and

innovation as generic skills in all educational

processes, implementing entrepreneurship

education in all engineering, science and

technology studies, supporting research projects

that could lead to technological spin-off start-ups,

and providing financing to enable the integration of

new technologies and the commercialization of

innovative products.

In addition, several of the EFCs show weaknesses

that may prevent Colombia from realising the full

contribution of entrepreneurial activity to its

growth path. The weakest of these EFCs is in the

area of financing for new and growth ventures.

Colombia has a number of support programmes

and initiatives to promote and nurture new

entrepreneurs and improve their managerial

capacities through the National System for the

Support and Promotion of MSMEs and within the

framework of Law 1014 and the National

Entrepreneurship Policy. Clearly the policy

approach is to address the needs of new

entrepreneurs through the various phases of the

entrepreneurial process. However, the GEM

Colombia findings indicate some priority actions

10

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF

Specific recommendations

that need to be taken to address leakages in the

entrepreneurial pipeline. These could specifically

relate to increasing the percentage of the adult

population motivated to become entrepreneurs

and then helping to successfully transition more

of them through the entrepreneurial pipeline into

formal established ventures with higher

innovativeness and value-creation potential. This

may require better coordination among the

various existing organisations, programmes, and

initiatives offering pre- and post-creation

support to nascent and early-stage

entrepreneurs.

Given the current framework of MSME and

entrepreneurship support, the findings

1)

Accelerate the integration of entrepreneurship

as core curricula in all levels of the educational

system, including at the university level, with the

objective of exposing students in all disciplines to

the knowledge and skills to pursue new venture

opportunities across sectors. Law 1014 (2006)

has made it mandatory for primary and

secondary institutions to promote

entrepreneurial attitudes in the pedagogy, but

this development is recent and will require

significant investment to develop curriculum, train

teachers, and foster inter-institutional networks

of support to roll-out initiatives across the

educational system. The law, however, does not

apply to the tertiary level of education, where

there is also a need to expose all students to

entrepreneurship, including in engineering, science

and technology programmes.

2)

Establish Centers for Entrepreneurship

Development in all regions of Colombia to provide

support services to potential, nascent and new

entrepreneurs. The experience of the Centros

Alaya in Cali, the Cedezo in Medellin and other

similar institutions should be expanded to provide

wider coverage. The MinCIT initiative to adapt the

experience of the American Small Business

Development Centers (SBDC) model in Colombia

is a move in the right direction.

3)

Review all financing programmes to assess the

extent to which they are meeting the needs of

new entrepreneurs and growth firms, including the

number of entrepreneurs assisted relative to

those with demand for financing, and accessibility

by women entrepreneurs. These include activities

of the Fondo Emprender, the National Guarantee

Fund, the MSME INNpulsa Fund, the Opportunity

Bank, the angel investor networks, and venture

capital funds. The aim is to ensure that start-ups

and young businesses have access to financing to

properly capitalise their enterprises and fund

their activities, including technology acquisition

(grant funds, seed capital, credit lines with

suitable terms, micro-credit, government-backed

loan guarantee schemes focusing on

compensating for the collateral deficiency of new

entrepreneurs, angel and venture capital

programmes). This is particularly important for

new entrepreneurs with higher-risk innovative

enterprises and women and young people who

have more difficulty accessing commercial bank

financing because they lack collateral and track

records.

4)

Encourage entrepreneurs to pursue higher

value-added opportunities by:

• Generating and widely disseminating information

about new venture (and value chain)

opportunities in knowledge intensive, creative,

service and innovation-related activity that are in

line with the government’s goals of promoting the

development of innovative businesses.

• Offering workshops on business opportunity

recognition to develop the ability of potential and

nascent entrepreneurs to recognise higher

potential, innovative business opportunities, and

supporting activities such as Startup Weekends

and accelerators that encourage the

development of higher value-added business

11

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF

ideas.

• Fostering stronger linkages between public

research centres, universities and the private

sector to facilitate the transfer and

commercialisation of R&D, and increasing the level

of resources to support commercially promising

research projects.

• Expanding the number of business incubators

(and premises) to develop the capacity of new

entrepreneurs and their innovative start-ups. The

National System of Creation and Business

Incubation with its focus on pre-incubation,

comprehensive enterprise development services,

and access to seed capital has the makings of a

good practice in Colombia and should be

adequately funded to increase its scope and

impact.

5) Include the targeting of women entrepreneurs

in the government’s entrepreneurship policy and

articulate specific programmes to ensure that

they have equal access to opportunities,

financing, business support, mentoring and

networks. A model worthy of replication and

scaling-up in all parts of Colombia is the Mujeres

Emprendedoras Colombianas por la

Competitividad (ECCO) programme , which has

the objective of fostering the creation and

strengthening of sustainable and competitive

enterprises run by women, so women’s

entrepreneurship can contribute more to the

economies of Barrancabermeja, Bucaramanga,

Cartagena and Cucuta. The programme provides

business development services (support,

technical assistance, consulting, training, business

links, commercial promotion, information, and

mentoring) to help women with innovative

business ideas launch their projects or strengthen

an operating company.

6) Provide on-going funding support for the

annual production of GEM analysis and both

regional and national reports. This will enable

Colombia to continue to track trends in

entrepreneurial activity and provide an

evidence-based mechanism for setting

quantifiable policy targets and benchmarking its

entrepreneurial performance. Several

governments around the world depend on the

GEM data to help benchmark their progress in

reaching their policy goals to improve the level and

quality of entrepreneurial activity, which would

also be a beneficial strategy for the government

of Colombia.

12

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF

References

Arenius, P., and M. Minniti (2005), “Perceptual

variables and nascent entrepreneurship”, Small

Business Economics, 24: 233-247.

Amorós, J.E. and N. Bosma (2014), Global

Entrepreneurship Monitor 2013 Global Report,

Babson College, Universidad del Desarrollo and

Universiti Tun Abdul Razak.

DNP (Departamento Nacional de Planeación)

(2011), National Development Plan 2011-2014 –

Executive Summary”. República de Colombia.

Joumard, I., and J. Londoño Vélez (2013), “Income

Inequality and Poverty in Colombia, Part 1. The Role

of the Labour Market”, OECD Economic Department

Working Paper, No. 1036, OECD Publishing.

Kantis, H., J. Federico, and S.I. Garcia (2014), “Index

of Systemic Conditions for Dynamic

Entrepreneurship: A tool for action in Latin America”,

Asociación Civil Red Pymes Mercosur, Rafaela

Kelley, D.J., C.G. Brush, P.G. Greene, and Y. Litovsky

(2013), Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2012

Women’s Report, Center for Women’s Leadership,

Babson College.

MinCIT (Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo)

(2009), “Política Nacional de Emprendimiento”,

República de Colombia, Julio.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development) (2014), Financing SMEs and

Entrepreneurs 2014: An OECD Scoreboard, OECD

Publishing.

Powers, J., and B. Magnoni (2013),”Pure

Perseverance: A Study of Women’s Small

Businesses in Colombia”, Multilateral Investment

Fund (FOMIN), Washington, DC.

13

Varela, R., J.A. Moreno, and M. Bedoya (2014a),

“Colombian Entrepreneurial Dynamics”, Centro de

Desarrollo del Espíritu Empresarial, Universidad

ICESI.

Varela, R., J.A. Moreno, and M. Bedoya (2014b),

“Caribbean Regional Report 2013, Centro de

Desarrollo del Espíritu Empresarial, Universidad

ICESI

COLOMBIAN ENTREPRENEURIAL POLICY BRIEF