The African Journal of Information Systems The African Journal of Information Systems

Volume 9 Issue 4 Article 2

September 2017

An evaluation of educational values of YouTube videos for An evaluation of educational values of YouTube videos for

academic writing academic writing

Gbolahan Olasina

University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ajis

Part of the Digital Humanities Commons, Instructional Media Design Commons, Management

Information Systems Commons, Online and Distance Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral

Sciences Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

APA

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by

DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been

accepted for inclusion in The African Journal of

Information Systems by an authorized editor of

DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more

information, please contact

digitalcommons@kennesaw.edu.

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 232

An Evaluation of

Educational Values of

YouTube Videos for

Academic Writing

Research Paper

Volume 9, Issue 4, October 2017, ISSN 1936-0282

(Received February 2017, accepted August 2017)

Abstract

The aim is to assess the impact of YouTube videos about academic writing and its skills on the

writing performance of students. Theoretical perspectives from constructivism and associated

learning models are used to inform the purpose of the research. The contextual setting is

matriculation students awaiting admission to higher institutions. The population is 40 students

belonging to a class aimed at assisting disadvantaged students in their academic writing in

Scottsville, Province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The students are broken into two groups –

control/traditional teaching and the treatment/YouTube facilitated groups. Consequently, a

dominant qualitative approach is adopted using focus group discussion, interviews and tests to

identify underlying patterns, methods and approaches to best fit academic writing guides and

videos to improve user experiences of the media for academic writing. The fundamental results

show that positive characterisations of user experiences include innovation, surprise, playfulness

and stimulation whereas the narratives that are not satisfying are categorised as dissatisfaction,

frustration, dissolution, disappointment, anger, confusion and irritation. Ultimately, the major

findings of the research have the potential to improve user experiences on the platform by

highlighting how and when the positive and negative experiences of users occur and a mapping of

the differences in the academic writing performance between the two groups and best practices.

Finally, the results have implications for pedagogy - the fitting of YouTube videos to academic

writing instruction.

Keywords: YouTube; digital media; informal learning; academic writing; South Africa.

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 233

Introduction

Key features of the digital environment demand a set of appropriate skills, acceptability,

adaptability, usability, accessibility, and availability. For instance, for teachers, instructors,

mentors, tutors, and learners to best tap from the new media to impact knowledge creation,

discovery, and use require novel strategies and approaches. Moreover, learning in the digital age

is prompted by integration of digital forms into learning (Ifenthaler & Tracey, 2016). The

abundance of digital media has flooded classrooms with new tools such as Virtual Worlds (VWs),

gaming, social media, m-learning, Webcasts, podcasts and YouTube videos. Surprisingly, one of

the challenges is to train instructors and learners with skills to appropriate digital media across

multiple disciplines. For example, Bennett, Maton & Kervin (2008) analyze from a historic

standpoint the “immersion of young people in digital technologies such as computers, video

games, and the Internet.” The immersion landscape presupposes an in-depth and diverse role of

digital media in the lives of the youths. Davis (2013) provides evidence of a high rate of adoption

and use of digital media by young people. Conole (2015) reports the value of learning experiences

with MOOCs as disruptive tools and underlines a need for innovation and new trends to improve

learning experiences for users. Likewise, Lai & Hong (2015) state that new digital tools influence

the kinds and characteristics of experiences of users since they inform new ways of life,

communication, play and learning. The authors identify the themes of user experiences to include

loss of a sense of time, difficulties with self-awareness, consciousness and interactivity.

Fortunately, Oleson and Hora (2014) and Conole (2015) argue that little empirical work is

available in the way users gain knowledge and experience technological tools in the classroom.

Thus, the current research aims to improve the existing knowledge in this discipline. Whereas there

are reports that little is known in the literature about the experiences of users of new digital media

meanwhile, the popularity of the tools continues to explode. Also, Sharma, Lau, Doherty & Harbutt

(2015) and Guo, Philip & Rubin (2014) report there has been little evidence on the use of YouTube

videos and participatory culture for teaching and experiences of students. Nonetheless, the use of

online videos continues to soar. For instance, Oyedemi (2012) and Olasina (2016) illustrate a high

rate of use of digital media in Africa despite the challenges of the digital divide, social inequalities,

poverty, lack of access and poor digital infrastructure. Real as the claims may seem, there is little

evidence of the uptake of educational technologies such as YouTube for academic writing.

Meanwhile, current academic curricula pay a high premium for learning how to write, express,

communicate knowledge and to the early exposure of students to academic writing. In fact,

academic writing is at the foundation of higher education. The goal of academic writing goes

beyond the basic communication of information. Its aim is often to proffer an original thesis or

argument either in support or against a particular idea or position. Accordingly, academic writing

is demanding. After all, it requires that students understand proper formatting, language, style,

grammar, referencing, citations and methods to produce a paper. In other words, learning the skills

to writing can only be achieved by concise efforts, training, and experiences. It is assumed that

such capacities may develop through the internalization of videos on academic writing for further

stimulation of improved presentations.

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 234

Unfortunately, academic writing is challenged by myths in second language writing by students

often leading to underachievement (Kamhi & Catts, 2013). Writing errors are common in the

writing abilities of university students. It is reported that there is a wide gap between teaching and

learning often demonstrated in the lack of creativity in the writing of students. As an illustration,

Abdulkareem (2013) investigated academic writing in English by postgraduate native Arab

speakers from the Arabic world. The methodology involves an identification of language and

writing errors reviewed by experts of English. The results underlined endemic problems and poor

academic writing performance of the Arabic-speaking students in English. The author concludes

by calling for new ways to employ effective teaching approaches to academic writing in a language

other than the mother tongue of a student. The current study aims at using the context of non-

native English students in South Africa to evaluate the influence of YouTube videos on the

academic writing of students. Likewise, Spaull (2013) explains the challenges of good academic

writing performance in South Africa from a perspective of apartheid. For instance, disadvantaged

students perform woefully academically based on a long abolished racist structure that refuses to

come to an end. In fact, black students have dysfunctional literacy skills which present challenges

for higher education.

Bharuthram (2012) and Kreek (2015) explain the essentiality of reading and writing to the success

of degree program completion in South Africa. Surprisingly, academic writing is a challenge to

non-native English students who are from disadvantaged backgrounds and thus exhibit limited

skills in reading and academic writing. In fact, the authors provide evidence of higher education

institutions in South Africa experiencing students’ poor academic performance, flat rates of

attrition and throughput, and disastrous academic writing pieces. Fortunately, the managers of

primary and higher education and individual universities in South Africa attempt to fight the

scourge of unhealthy academic writing by students. For instance, the University of KwaZulu-Natal

and more recently, the Durban University of Technology established academic writing divisions

and centers to enhance the improvement of academic writing. The facilities have experienced

tutors, mentors, and instructors who assist students in their writing. The teachers offer support,

advice, companionship to nurture creative and improved writing. Unfortunately, despite the

support structures, mentorship and peer assessment aimed at helping students to write better,

evidence of positive impact on academic writing performance is not well reported in the literature.

Because of the compelling reasons above, the current research employed an approach using

relevant YouTube videos to evaluate their educational value on the academic writing of students.

Thus, the purpose of the study is to assess the educational value of YouTube videos for academic

writing. After all, new digital media and tools are often used for amplification purposes only

(Drijvers, 2015; Hughes, Thomas & Scharber, 2006). Consequently, the study addresses the

approaches to orthodox teaching and learning of academic writing and those facilitated by digital

media. The aim of the comparison is to highlight potentials of new media for student interactions

and learning. The next section presents the critical questions of the study.

Research questions

1. What kinds and characteristics of experiences are present in student interactions with

YouTube videos for academic writing?

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 235

2. Is there a difference in academic writing performance between the traditional teaching

group and the YouTube facilitated group?

3. To what extent can YouTube videos fit into improving academic writing performance?

The following section presents the literature review.

Literature review

The purpose of the section is to provide a context and give an evaluation of research on educational

technologies in developing countries in general and educational applications of YouTube videos

in particular. In other words, the review covers the description, clarification, summarization of

literature in the selected field of study and the choice of theoretical perspectives. Accordingly, the

analysis of literature identifies and articulates relationships across existing literature and the field

of research.

Challenges of educational technologies in developing countries

The issues of educational technology in developing countries are well reported in the literature.

For instance, Kremer, Brannen & Glennerster (2013) highlight the challenges of the adoption and

use of educational technologies in developing countries. Some of the identified issues include

diffusion of technology, supplies of computers and efficient use of ICT requiring the availability

of equipment and tools, pedagogy issues, accountability, access and quality. Likewise, Bhuasiri et

al., (2012) report the problems of innovative technologies in education in developing countries to

comprise software licenses, training, maintenance issues, hardware and software costs and learning

material development. Because of the broad scope of educational innovation and tools, several

studies focused on specific tools. For example, Liyanagunawardena, Williams & Adams (2013)

find that MOOCs in a developing country landscape are challenged by insufficient download

speeds of Internet connections, language, and computer literacy. The authors call for a better

understanding of MOOCs in developing countries. Hajli (2014), Pimmer et al. (2014), van Dijk &

van Deursen (2014) identify that little is known about the experiences of learners with new digital

media in the developing world. Meanwhile, Tarhini, Hone & Liu (2014) concentrate on the issues

of theory and practice regarding transformative pedagogical practices and need to develop and

execute sound technology educational practice for users in Lebanon. The essential conclusions

emphasize the social and individual factors as opposed to technological issues commonly reported

in the literature. Finally, educational technologies can be a very broad field covering a variety of

tools. Besides, a majority of the reviewed literature either use the lens of faculty or organizational

and formal contexts to view educational values of such practices, students’ views are not taken

into consideration. In other words, some of the essential problems of educational technology

include a lack of understanding of user experiences, limited empirical evidence of the effect of

new tools on student performance, and an absence of strategies and approaches to best fit digital

media to the learning processes of students (Saheb, 2014). Because of these compelling reasons,

the current study provides a clear and definite focus on the educational values of the YouTube site

in an informal learning context in South Africa.

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 236

YouTube videos

YouTube is based on a video sharing platform allowing a customized upload of content by users

(Pinto, Almeida & Gonçalves, 2013). Usually, the channel allows for users to keep track and

manage a record of users that view the videos. The host of the videos is created by professionals

and amateurs. Put simply, YouTube is a modern mass medium commonly used in a new digital

age landscape. Cheng, Liu & Dale (2013) give a historical account of the establishment of

YouTube in 2005 and the enormity of the bandwidth it consumes. Perhaps, the popularity is based

on its facilitation of user-created video content. In fact, more than sixty hours of videos are

uploaded by users per minute on the platform (Wang et al., 2013). Even though the channel is

limited to the length of videos that can be uploaded, YouTube has a high rate of adoption and use

compared to similar online video services such as Vimeo, Hulu host and a host of online video

streaming platforms.

Furthermore, little is known about general applications of YouTube videos (Thelwall, Sud & Vis,

2012). There is no clear understanding of the applicability of interactivity standards associated

with digital media in the series of steps involved in academic writing. Fortunately, there are calls

for new models and approaches to teaching and learning in a digital environment. As an

illustration, originators of various models of education have highlighted the importance of

collaborative learning tools, the reconstruction of ideas and the co-construction of knowledge.

Many of them (models) trace their beginnings to constructivism as a theoretical foundation. In

contrast, many theorists have condemned existing approaches to explain digital media facilitated

instruction based on theoretical foundations that were born before the digital revolution (Twining

et al., 2013; Conole, 2015). In the light of these, one of the goals of the current study is to evaluate

approaches to fit educational writing videos on YouTube to improve experiences and performance

of academic writing by students.

Whereas Cheng, Liu & Dale (2013) consider videos on the channel as entertainment-based, other

researchers categorize the platform as broadly based with potentials for education and life-long

learning. In fact, traditional media contents are not new to primary and higher education. However,

there is a need to improve knowledge by focusing on the effect of YouTube videos on users and

devise strategies to integrate them best to learning.

YouTube videos as educational innovations

Gabarron et al. (2013) state the potential of YouTube videos in the context of health promotion

and education. Nevertheless, the authors raise safety concerns about the environment of online

videos and the volatility of the video sharing service. Likewise, Kay (2012) gives a broad review

of research on video podcasts to provide a framework for an educational approach to the new

media. The review covered fifty-three articles highlighting the potentials and the problems and

methodological concerns related to the research area. The main conclusions of the research show

the possibilities of videos to include positive attitudes, learning control, enhanced reading and

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 237

study behavior, and the students’ improved performance. Unfortunately, the researcher explained

some downsides of the integration of videos in the learning process to include reduced class

participation, preference for orthodox teaching, and technical problems. Consequently, the author

raised methodological issues concerning research in the field. Some of these include limitations of

sampling, lack of rigor in the demonstration of statistical conclusions and data quality. In

conclusion, Kay (2012) calls for future research to focus on a provision of empirical evidence on

the impact of online video and new media, and the need to improve the understanding of user

experiences in learning contexts. Meanwhile, Michikyan, Subrahmanyam & Dennis (2015)

propose models for the best fitting of social media to academic performance. The authors tested

the nature of relations between the use of Facebook and improved academic performance of

students. Their results show overwhelming positive influence of the social medium on academic

performance suggesting that academic pursuits may determine students’ use of social media

beyond what is commonly reported. However, the report by Michikyan et al. (2015) is limited.

For instance, it is lacking in paradigmatic orientation and is the report is not informed by any

theoretical perspectives to drive data. Also, the report did not collect data to test the models

proposed. Accordingly, the aim of the current study is to add to the pool of knowledge and improve

the understanding of best fitting YouTube videos to academic writing performance. The approach

of the current study is based on the foundations of methodological and theoretical choices to add

breadth and scope to the research. In contrast, Al-Mukhaini, Al-Qayoudhi & Al-Badi (2014) and

Kim et al. (2014) provide evidence of existing difficulty in the process of fitting the use of

technology into the learning experiences of students resulting in a mismatch leading to poor

academic performance and additional frustrations for learners. In fact, Sadaf, Newby & Ertmer

(2016) and Hew & Brush (2007) shed some light on the fitting of a broad spectrum of Web 2.0

tools to teaching specific subjects in the contexts of teachers and pupils. The current research

explores the perspectives of students and further adds breadth by conducting the study using less

formal settings. In other words, there is not enough compelling empirical evidence of the effect of

new media on student performance. The current research uses the context of students in an informal

learning environment empirically to evaluate the effect of YouTube videos on academic writing

skills and performance. The choice of methodological framework is informed by the purpose of

the study and need to cover the critical questions of the research.

Duncan, Yarwood-Ross & Haigh (2013) explain the importance of video sharing sites and argue

that YouTube videos are valuable to practical, medical and clinical science education, and

research. The authors report that the videos on YouTube may be used in ways to stimulate student

participation to counteract the students’ lack of interest often reported in traditional learning.

Whereas many authors and the media are over-enthusiastic about the possibilities of new digital

media in primary, intermediate, higher education and life-long learning other researchers hint at

caution by highlighting the negative impact of YouTube videos and digital media on learning. For

example, Tess (2013) warns that social media may negatively affect a student’s performance. In

fact, the author used structural equation modelling and provides evidence of a significant negative

relationship between the use of new media and academic pursuits.

As a matter of fact, Wood et al. (2014a) argue that new media and technology including short

message service (SMS), instant messaging (IM) and texting, and the use of slangs do not seem to

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 238

affect the spelling performance of pupils negatively. However, the researchers report an

association between the impact of text messaging and an understanding of grammatical

procedures. Ultimately, it appears there are negative implications of the use of instant messaging

services on academic writing. After all, some social network platforms require the use of a

maximum of 140 characters requiring users apply a shorthand approach. In other words, Wood et

al. (2012b) emphasize the negative impact of multi-tasking on students who are studying and

texting at the same time. The researchers suggest that multi-tasking may be responsible for reduced

rates of academic performance. As an illustration, Cingel & Sundar (2012) state negative

associations of word adaptations based on text messages to grammar assessment in schools by

students. Nevertheless, some researchers argue that text messaging and social media do not hold

negative implications for users. Accordingly, arguments and counter-arguments remain over

individualistic and competitive learning, as well as orthodoxy thinking versus new digital media

in the classrooms (Kivunja, 2015). Consequently, the present research verifies the effects of a

YouTube facilitated approach to enhancing students’ academic performance. Perhaps, the

affordance of digital media such as YouTube videos for academic writing is worth a try.

Meanwhile, Guo, Kim & Rubin (2014) provide empirical evidence of student engagement with

video materials in informal settings over and above podcasts or pre-recorded classroom lecture.

The methodological approach using both quantitative and qualitative data measured the length of

time students used watching each video in correlation to the output of assessment. The conclusions

recommend a framework to support the appropriation of online video formats for instructors and

video producers. As a matter of fact, the current study contributes to a comprehensive framework

to include academic writing. After all, an evaluation of the impact of technology on learners and

academic performance often does not focus on academic writing per se. Also, previous studies’

respondents suffered memory and retrieval bias as they reported past experiences. However, the

current research addresses time-dependent concerns of user experiences of YouTube videos in real

time on a project.

In fact, many academic institutions use YouTube to record and disseminate course modules for

classes with the videos available via the e-learning systems and the Internet. For instance, Jafar

(2012) reports that 98% of students used YouTube videos as an online information resource with

86% of students confident that the platform helped their learning of anatomy. Because of the

significant findings, the authors conclude that the videos were a useful tool for instruction.

Meanwhile, there are reports of continued explosion in the number of users of social and new

digital media globally, including Africa because of improved Internet penetration and mobile

technology. Surprisingly, the use of new digital media by academics and students for educational

purposes remains limited (Lenhart, Madden, Macgill & Smith, 2010; Al-Aufi & Fulton, 2014).

Furthermore, Chapman (2015) raises concerns about the best fitting of YouTube videos to

academic teaching because of misinformation.

Thelwall, Sud & Vis (2012) report an analysis of large samples of text commentary on YouTube

videos. The results shed light on identity patterns of positive and negative comments and a density

of discussion in proportion to replies to user comments. This rare user study shows that the highest

rates of comments are triggered by themes such as religion and overviews of life, whereas videos

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 239

on subjects such as fashion, style, entertainment, and music attracted minimal comments posted.

In conclusion, the authors claim a categorization of YouTube users by themes of the videos.

Fortunately, Kousha, Thelwall & Abdoli (2012) prove that online videos are applied for teaching,

informal scholarly communication and citation in academic journals. The authors’ inquiry was to

determine the disciplinary scope of the citations of YouTube video. Based on content analysis of

a broad array of Scopus publications, the researchers state that the arts and human and social

sciences were the most common to have cited YouTube videos. In other words, the most mentioned

themes are culture, history, news, politics, and documentaries. The following section presents the

theoretical perspectives used to underpin the research.

Constructivist perspective

Several theoretical perspectives and models are applied to explain learning and its approaches.

Recently, the emergence of new digital media and technologies continue to stretch the fabrics of

theory to fit technologies appropriately to pedagogy. In many ways, most learning models and

approaches originate from constructivism. The theory holds that there is a real world that we

experience (Duffy & Jonassen, 1992). The interchange of ideas between constructivist learning

and the technology of instruction is essential. For instance, Duffy & Jonassen (1992) argue that

the value of learning theory rests in the ability to predict the impact of instructional practices on

what is learned. Thus, the current research is underpinned by the constructivist perspective to shed

new light on opportunities and challenges to the practice of designing instruction for academic

writing using YouTube videos. Put simply, the arguments and assumptions of the theory are that

meanings are imposed on the world by us and that there are many ways to structure the world.

Constructivism suggests there are many meanings and perspectives for events and concepts. In

summary, constructivists argue that there is no correct meaning. The theory emphasizes meaning

and experience-cognitive experiences in authentic activities. Speed (1991) and Winn (1993)

examine the implications of constructivist perspectives for instructional theory and learning

practice. The philosophical positions of the theorists provide a justification for the choice of

constructivist perspectives to inform the research questions of the current research.

In summary, faculty members need to evolve new approaches not only to engage and motivate

learners, but to enhance teaching by using media such as YouTube videos and exploit their viability

to supplement traditional learning spaces. Previous studies examined the general role of social

media in primary and higher education and the affordances of digital media for student

performance.b It is important to improve the understanding of how YouTube videos can best fit

academic writing training in informal learning contexts. It is also critical to employ theoretical

perspectives from constructivism and relevant learning models to inform the research and address

the research questions of the study. The approach may be vital as most of the previous studies are

not underpinned by theoretical frameworks. Ultimately, an understanding of user experiences of

YouTube videos for academic writing will be enhanced, and the context of South Africa is used to

improve the knowledge of educational values of digital media. Finally, the constructs such as

meaning and experience from constructivism are used to guide the design of instrumentation and

data based on the methodological choices of the study. The details of the latter are presented next.

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 240

Methodology

A pretest and post-test were conducted involving two groups of students. All lesson plans are

aligned to standards of core competencies in academic writing. Two experts of academic writing

offered critical feedback on the lesson plans, project activities, and blended approach to learning.

The two project groups completed the same tests. Because of the purpose and critical questions of

the study, a dominant interpretive paradigm is adopted. Accordingly, both qualitative and

quantitative approaches are employed to adequately address the purpose of the research. The

research design is semi-experimental to highlight the difference in the academic writing between

the control/traditional teaching and treatment/YouTube facilitated groups. In fact, a focus group,

in-depth interview and tests (quantitative strands) are the data collection methods used to identify

underlying experiences, relationships, patterns and explain context-specific issues that are critical

to the research. Consider that the students in the traditional teaching and YouTube facilitated

groups are both subjected to a focus group and interviews. Ultimately, the themes for the data

collection instruments are framed by the critical aspects of academic writing such as grammar,

vocabulary, organization, referencing, and group work. The adopted methodological choices are

not without criticisms. However, the justification for the use of focus group is based on Mao (2014)

providing evidence that it is valuable in studying the use of technology by learners. Furthermore,

the in-depth interviews and tests are used to address the context-specific issues raised by the

research questions of the study. After all, the individual interviews and focus group discussion

provide evidence of ambivalence, inconsistency and conformance (Fielding, 2012). Consequently,

the use of multiple methods of data collection particularly in a dominant qualitative study is to

complement, validate, draw on the strengths of each tool and add scope and breadth to the research

(Kidd & Parshall, 2000). Also, five raters are involved in the assessment design process to

underscore objectivity. Ultimately, inter-rater reliability was based on the framework by Miles &

Huberman (1994). Because of the growing call for a demonstration of academic rigor in qualitative

research, the current study pays attention to analytical precision, data, approaches and the use of

content and thematic analysis by Braun & Clarke (2006). The adopted framework for the

presentation of the reliability and validity of the data collection tools are guided by Anderson

(2010) and Creswell (2013). The guideline provides that procedures to establish the reliability and

validity of conclusions are presented alongside the presentation of the results and in-text where

relevant, as opposed to dedicating a stand-alone section for that purpose. This is expected to make

reading easier. Finally, the following section presents the details of the participants.

Participants

A total of forty participants were recruited from over a hundred matriculated students who recently

completed their high school education and are awaiting university admission. The implication is

that twenty respondents belong to each of the two teams of participants regarding the traditional

teaching and YouTube facilitated groups. The students belong to a community service initiative to

help train poor students. The aim of the cohort is to improve the academic writing of students in

Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg, Province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The facility is equipped

with trained tutors and instructors who are postgraduate students who assist students in improving

their writing skills, oral and slide presentations, reading, reporting, and review of the literature

capabilities. The participants are drawn from a larger pool of students who attend the free writing

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 241

classes holding in the form of workshops. The criteria for selection include regular attendance,

commitment, and basic proficiency in English. It was after the exploratory analysis that twenty

students each were retained respectively for the control and test group and for the YouTube groups.

Each team is made up of eleven females. The control and test groups are made up of nine males

each. All the students have no basic experience to moderate skills of ICT use and only five are

familiar with the use of Virtual Worlds (VWs) such as Second Life, Active Worlds, IMVU, World

of Warcraft, and multiplayer online games. Exploratory data collection shows that twenty-one of

the participants have accounts on social media and have viewed YouTube videos for

entertainment, social engagements and religion. They access the platform’s videos mostly on their

mobile devices, in public cafes, at school, and on friends’ devices and church devices. Four

respondents indicate using YouTube videos to learn how to keep the pacifier in a baby’s mouth

and learning how to drive a car. Finally, twenty-one students have used social and new digital

media in school related activities in their primary education. Ten participants share their

experiences of updating live videos of violent protests, events in the church, dance parties, and

rugby matches onto online platforms of news channels. Finally, the age range of all the participants

was 19-24 years, and seven of them work part- time. It is typical for a study that is predominantly

qualitative to have a sample size between 5 and 20 (Petty, Thomson & Stew, 2012). Whereas a

sample size of forty is considered large for qualitative research, a quantitative approach will find

forty as inadequate. Consequently, forty is retained to meet the requirements of the quantitative

strand; this is further justified by Antenos-Conforti (2009), Holotescu & Grosseck (2009) and

Ebner et al. (2010) who have used sample sizes ranging from 10-50 with success in a related IS

research. The control group was taught using conventional strategies such as marker boards,

program outline, guide, classroom teaching, handouts, and assignments. The framework that

guided both groups was based on the academic writing curriculum at the writing center of a South

African University. The framework emphasizes the following: grammar, vocabulary, organization,

referencing, pre-writing, drafting, revising, editing and proofreading and group assignment

writing. Meanwhile, the test or YouTube group’s education used strictly learning techniques

facilitated solely by selected YouTube videos including YouTube Edu for ten weeks. The

framework that guided the selection of YouTube videos is provided by Kousha, Thelwall & Abdoli

(2012) and Guo, Kim & Rubin (2014) and it met the requirements for the academic writing

curriculum stipulated by the academic writing center framing the instructions for the two groups.

After that, the selected videos are presented to two experts who are managers of academic writing

divisions at two South African universities. The selection criteria were to eliminate misinformation

and to establish accuracy. After all, Internet resources should be evaluated for their educational

values and authenticity. Meanwhile, class outline and activities for the control group included

instruction on grammar, vocabulary, organization, referencing, pre-writing, drafting, revising,

editing and proofreading. Also, tutors used lesson notes, textbook reading lists and handouts. The

class lessons span a period of ten weeks.

Results

The research procedures involved meetings and discussions with tutors and instructors engaged by

the researcher to serve as observers and moderators to enhance an understanding of the overriding

purpose of the study and to address the critical questions of the research. Meanwhile, the academic

writing tutors and mentors are PhD candidates and experienced moderators and observers.

Consider that the study is drawn from a larger project to employ the context of South Africa to

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 242

explore user behavior in virtual environments. After all, some of the wider objectives of the project

have been published in journals elsewhere. Accordingly, the 10- week time span guided the lesson

plans and class activities for the two groups. Each of the class sessions lasted an hour and held at

least twice in a week. In other words, the groups had the same instructional goals of improved

academic writing performance. Meanwhile, the non-formal learning space coupled with deliberate

efforts was a setting for exciting mood, risk-free domain, flexibility for students to choose their

writing topics compatible with participants’ interests and to self-regulate. From the get-go, the

test group was facilitated after traditional teaching by academic writing videos on YouTube in

week one onwards. Also, the two groups were subjected to pretest and post-test analysis. The

exploratory study informed the selection of forty students split into the groups based on

exploratory data and willingness to participate. The exploration was done through interviews to

examine student behavior in the world of social and digital media, and how and why the students

use the tools. The exploratory data collection helped to identify particular media used, frequency

and purpose of use. Also, the exploration contributed to determining the common barriers, past

experiences, and factors that discourage/encourage the use of digital media. Also, the two groups

were subjected to pretest and post-test analysis. The pretest involved two experts measuring and

evaluating the validity and effectiveness of the questions to guide the focus group and interview

sessions. The focus group discussion held once for the two groups while the in-depth interviews

lasted approximately 20 minutes each for participants. The fall outs from the focus group meeting

informed the questions for the interviews. In fact, based on the briefings and meetings held with

tutors, moderators and reviewers a sample size for the in-depth interviews for the two groups was

drawn. Finally, the post-interviews were held at the end of the ten weeks of classes. Quantitative

data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 24. The research questions guide the presentation of

the next section.

Experiences of YouTube videos for academic writing

Narrative analysis of experiences of the use of academic writing YouTube videos is conducted to

address the first research question.

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 243

Figure 1: Illustration of one of the videos used to facilitate academic writing group

The student sessions facilitated with YouTube videos involved asking participants to report their

experiences. The narratives extended beyond class sessions to cover self-use of the videos outside

of class. The Web link to relevant videos was made available to the students. Some of the

significant statements of the test group captured are presented below:

“I identify videos with relevant academic writing subjects from the recommended feature on the

YouTube home page.”

“Based on the links to academic writing videos provided by tutors, YouTube offers suggestions of

similar videos that I can view.”

“I use YouTube to view work and general study-related activities.”

“I find it difficult to download and save videos on the platform.”

“Acquiring South African content and information on academic writing videos is hard.”

“I like to explore the YouTube environment for academic writing videos.”

“I think YouTube is for socials, arts and entertainment.”

“I just play around and often see videos that are not academic writing based.”

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 244

“YouTube videos helped my understanding of formats of written assignments, structural and

technical formatting of my assignments.”

“The videos positively influenced my experiences.”

“The exposure to YouTube for teaching and understanding academic writing seem like an

unfamiliar terrain.”

“The YouTube video activities are critical for my academic writing.”

“The videos often offer me crucial information that helps me to write better.”

“I often suffer malfunction of video, missing a video or some other technical problem when I try

to access YouTube on my phone at home.”

“From watching the videos, the strategies of academic writing such as paraphrasing and mind

mapping are clear to me.”

Meanwhile, the research exploited group dynamics to highlight the differences between group and

individual interviews conducted, and how these impacts the analysis and guide the interpretation

of focus group data. Several critics of qualitative methods have demanded a demonstration of rigor

to ensure data quality and validity of conclusions (Toomela, 2011). As a result, practical steps are

taken such as conducting and analyzing the focus group, recruitment of participants, logistics and

making sense out of data. For instance, environmental conditions are made convenient for the test

group to find the YouTube videos for academic writing to be stimulating. Also, the discourse in

the session of the focus group and interviews depended on moderator/interviewer skills leading to

casual conversations. The researcher and assistants were at the focus group meeting and interviews

for the corresponding groups. The participants are well known to the researcher and associates

who are tutors and mentors of the academic writing cohort. In other words, the recruitment

procedure and familiarity with respondents’ characteristics and a high emotional stake on

academic writing skills were an advantage. For instance, during the focus group session, there

were agreements and disagreements on the satisfying and unsatisfying experiences using the

prescribed YouTube videos for academic writing. In fact, the mixed experiences are critical

moments that influence the nature and content of responses. Unfortunately, the experiences

involved negotiation, criticisms, commiseration and modification. Fortunately, the mixture of

experiences was subjected to group moderation, structuring and the design of interview guides to

ensure data analysis and conclusions are sound. Also, peer reviewer comments were solicited after

the briefings and meetings held by the researcher, assistants, and tutors. Specific analytical

approaches were used to increase confidence in focus group data and involve a theoretical

understanding of user behavior in the application of YouTube videos for academic writing.

As an illustration, the analysis of interaction in focus discussion shows some of the following:

shared language on the integration of YouTube videos to academic writing, emerging data on user

issues taken for granted with the use of new media and user myths and beliefs about YouTube

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 245

videos. The analysis reveals arguments and feedback from participants on the use of educational

videos and highlights their best practices. Finally, the observation of the voice tone, emotional

engagement, and body language of participants about the discussion around the adoption and the

use of YouTube videos for academic writing are included in the analysis. The coding procedure

involved the organization of data to enhance analysis and interpretation. In fact, data are fractured

by working on the transcript to identify the kinds and characteristics of user experiences with the

application of YouTube videos for academic writing. For instance, user experiences are tracked

from the start to the end through the transcript using marker pens. Accordingly, user experiences

are coded or labeled based on a spectrum of dimensions such as practices, learning activities,

characteristics of experiences and related YouTube videos for academic writing features, emotions

evoked, unsatisfying and satisfying experiences. The focus discussion and interviews were

conducted after the 10-week long exercises in academic writing. The following quotes are drawn

from the transcript of the discussion session for the YouTube group. The quotes are in the context

of the research question 1.

Moderator: (in response to a general discussion on what it is like to view academic writing videos

on YouTube)

Fantasy1: “I am fascinated by the fact that the videos are not only recreational and entertaining

to follow, but everything felt relaxed, informal and enjoyable.”

Moderator: (as the group proceeds with participant discussion on their experiences, other

responses include the following: -)

Day1: “I would describe my experience as interesting.”

Moderator: (specifically which aspects were interesting and which ones were not?)

Moderator: (experiences from other participants….)

Flower1: “Apart from the remarkable but reinforcing experience of learning academic writing

through the videos is the rather big surprise of a ‘subscribe’ feature on YouTube that enables

notifications of new videos from content creators. I think during one of our last classes the tutor

demonstrated in class how to get up to date using the subscriber notification alert by email and

mobile devices.”

Flower2: “It is satisfying to view the accredited videos as they help to resound the key topics

learned from the academic writing classes and guidelines from the tutors.”

Moonlighting1: “I find the selected videos introduced by the tutors very easy to understand and

interact with more so as we had received foundational classroom teaching on the basics of an

excellent essay and grammar.”

Moonlighting2: “I was able to understand better the information the tutor provided in class and

the feedback from a previous assignment only after replaying the YouTube videos over and over.”

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 246

Bunny1: “My experiences with the YouTube videos are meaningful as new ways to learning

academic writing skills and enhance improvements.”

Bunny2: “I was able to identify that viewing the videos before writing my draft assignments

improved my academic writing performance.”

Rainfall1: “Mine is a feeling of power over my writing as a result of the YouTube tool to access

educational information.”

Winter1: “My experience is shaped by the promise of availability of the YouTube videos 24/7, and

this is useful as I can learn even when I am mobile.”

Flower3:” I prefer to write the draft of my assignments, pause, view videos relevant to the lesson’s

topic, reflect on the videos and afterwards review, modify and refine my writing.”

Summer1:”I observe that the tutors emphasize that academic writing is a process involving pre-

writing, drafting, revising and a whole lot more. Surprisingly, the videos highlight a process as

fundamental to successful academic writing performance.”

Moderator: (in what specific tasks have you had the experiences that you share?)

Summer2: “My observation is that the YouTube videos help more with pre-writing activities,

specifically, influencing my thinking, brainstorming, and broad pre-writing strategies.”

Grassland1: “I eagerly long for the tutors to send links to YouTube videos.”

Moderator: (why so?)

Grassland2: “I guess I am fond of sharing my views of the videos with peers and tutors.”

Airforce1: “The videos are not easy to forget. Besides, I can always go back to see them online if

I did not download them.”

The analysis of the illustration and the review reports of meeting, briefings and observations by

the researcher and assistants show the characteristics of satisfying experiences and related

YouTube videos’ features. Indeed, the group discussion was critical to the bond and exchange of

stories of participant experiences. The interactions were coded for all the members to formulate

the following themes. For instance, the analysis of satisfying themes from the narratives above

mentioned demonstrates substantial and practical experiences. In fact, distinct experiences have

their characterizations as fascination, surprising and entertaining, as well as social. In other cases,

some of the narratives provide broad interest in new media, innovations, new ideas and approaches.

Fortunately, the features of some of the experiences show positive surprise, attitudes and

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 247

perceptions, playfulness and stimulation. The in-depth analysis of the interview and focus

discussion data above, shows users view the application of videos as efficient and empowering.

The significant statements show broad interests towards engaging YouTube videos in improving

their performance of academic writing. In other words, the efficiency spans from memory retention

and 24/7 availability of the videos. The key results suggest high perceptions of ease of use and

usefulness of the videos to improved academic writing performance. After all, the value of the

videos is narrow to specific content such as pre-writing procedures and features such as subscriber

notification and comments that users post. The narratives suggest that the YouTube videos

complement traditional teaching. The in-depth analysis shows that the satisfying experiences result

from positive emotions and high arousal associated with an urge to play, to explore and interact

with the selected YouTube videos. The significant excerpts support an argument that students

establish a view that the videos may be most useful after the foundations of academic writing are

traditionally taught by tutors in class and by reading handouts. Also, a few of the key narratives

highlight social contexts. For example, subscription to features and services, posting/reading

comments on the platform, online interaction with other users and evidence of collaboration.

New issues that emerge from the data reveal in few explicit statements on matters such as viewing

of the videos repeatedly and obsessive use even though the students still attended physical classes.

The element of surprise underlines that respondents find the videos relevant and useful for their

academic writing needs whereas many think the videos are purely for entertainment. The not so

satisfying experiences are presented next.

About experiences characterized as not so satisfying were some narratives in the analysis.

Narratives that were not satisfying experiences are categorized as the following: dissatisfaction,

frustration, dissolution, disappointment, anger, confusion, and irritation. These originated from

respondents not finding selected videos, missing videos, failure to meet expectations, technical

issues – video not playing well, limited access to the internet (data related), and reduced display

on mobile phones. Some significant narratives are given below:

Sunshine1: “Access to the videos outside of class is challenging as I do not have data to browse

on my phone.”

Moderator: (remember that internet access is provided in the classroom and tutors share the

information on how to save to your devices content that has a “download” or similar link displayed

by the platform)

Sunshine2: “In many cases half way through the download process, it stops and sometimes when

I am successful, I am unable to play the downloaded video as my device either does not have

enough memory space or app to play the files, disappointing.”

Moderator: (cuts in, YouTube has Terms of Service, remember, and such ethics should not be

broken)

Pond1:” Over 80% of attempts to view the videos outside of the class are usually problematic and

unsatisfactory due to network related problems either on my device or GSM service provider.”

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 248

Pond2: “The screen of my mobile device is smashed and terrible to view the diagrammatic

representations on the marker boards presented in the videos and many times the audio only does

not suffice when I see YouTube resources at home.”

Moderator: (do you have difficulty listening to the videos? Tell us more about your experiences)

Station2: “I know one or two videos presented at earlier classes were in the context of South

Africa and the rest of Africa but what I am saying is that why do we not have more content close

to our environment?

Station3: “I will relate more with contents of the videos if closer to the South African life.”

From the reports of the not so satisfying experiences, they seem to be very similar and demonstrate

grades of dissatisfaction. Many of the experiences are a result of technical factors and

shortcomings. The next section presents the analysis for research question 2.

Difference in academic writing performance between traditional and the YouTube

facilitated groups

The second research question aims to observe differences in the academic writing performance

between the control group that received regular training in academic writing and their counterparts

whose training included facilitation by selected YouTube videos. Also, qualitative and quantitative

analysis methods are used to address this research question. Consider that the traditional mode of

instruction classes involved lessons from tutors, paper-based assignments, handouts and a tutorial

discussion. On the other hand, the test group, also, was facilitated using selected YouTube videos

in and out of class. In other words, the latter group had to combine viewing of videos, post

comments online, complete video related assignments, focus group discussion and interviews.

A set of essay writing tests was developed by the researcher based on the project’s lesson plans

and reviewed by two experts in the academic writing division of a South African university.

Besides, an expert in evaluation and measurement examined the essay criteria checklist for

technical and content consistency and validity. In fact, the composition criteria list focused on

grammar, vocabulary, organization, referencing, and group writing based on the framework

provided by Dempsey, PytlikZillig & Bruning (2009) and Knoch (2009). The entire essay writing

tests are 100 marks. The two groups completed the same lesson plans, a period of classes and

assignments, and tests (see methodology section). For instance, the procedure for both groups at

the 10th week involved being asked to write 500 and 1000-word essays. Individually, the essays

are evaluated for correct expression, use of words, illustration and examples to support a position

or an argument, proper use of grammar, vocabulary, use of words, appropriate use of citation, and

referencing. Also, the students were expected to compare and contrast, synthesize, organize, and

present coherent essays.

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 249

The evaluation of the compositions was done by the tutors, rated and reviewed independently for

each group by two experts of academic writing using a structure criteria checklist. In fact,

measuring essay assessment involved rater reliability of the vital decisions made by the essay

writers. Thus, raters (n= 5) who evaluated the essays are experts of academic writing. The students

who wrote the essays in control (n= 20) and the test groups (n= 20) to test their writing skills were

compared. The measurement results show 1000 ((5 raters x 20 essay papers) x 10 independent

sessions) for each group. In other words, the ratio of agreement among raters had to be significant

to the number of raters who agree as per each criterion/total number of evaluators. Accordingly,

the evaluators are subjected to standardized open-ended interviews by the researcher. For instance,

some of the question stems are the following: What do you think of the assessments that you made

based on the essay criteria checklist? What are some of the recognized assumptions? What is your

evaluation of the arguments? The answers to these questions show the reflections and

interpretations of the evaluators based on the adopted rating process.

Meanwhile, the approved procedure involved each student’s essay to be assigned a random code

for each rating, based on the pseudo names of the respondents. Emphasis is placed on the

differences in the scores based on the traditional academic writing class and the group facilitated

by YouTube videos. Consequently, a process of person-to-rater-essay was conducted to minimize

the variation of marks scored due to potential effects of person and evaluator. Ultimately, the rating

process was deemed consistent and valid based on Miles & Huberman (1994).

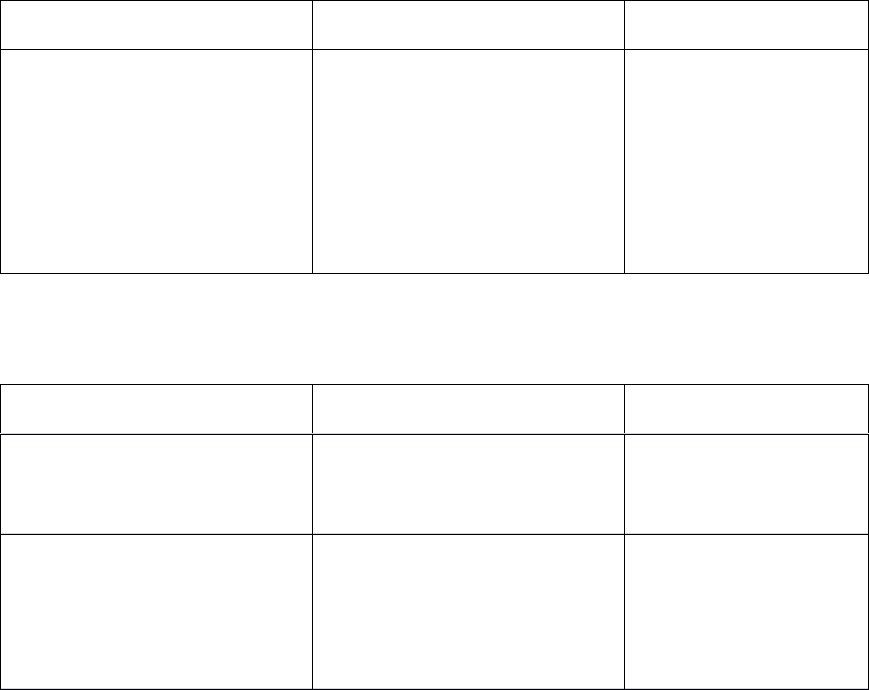

The summary statistics in Table 1 describe the means, standard deviation and adjusted means of

the three tests for the two groups. Both groups show improvement on the post-test when compared

with pre-test scores. The statistics in Table 1 suggest that the academic writing group that was

facilitated in class (and outside of class) by YouTube videos performed better (mean values of

57.14 and 73.56).

Olasina. Educational Value of YouTube Videos for Academic Writing

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 250

Table 1: Summary statistics of academic writing tests

Sub- total score (20) Traditional teaching group YouTube video facilitated group

Pre-test Post-test Pre-test Post-test

M SD M SD Adj.M M SD M SD Adj.M

Grammar 8.12 2.81 10.28 3.10 9.98 14.71 4.11 20.51 3.91 19.88

Vocabulary 9.92 3.09 10.55 5.02 12.01 14.10 6.23 16.51 3.12 14.77

Organization 12.37 4.91 9.88 4.07 11.38 12.56 6.01 16.10 5.92 16.17

Referencing 8.92 3.22 10.49 2.18 6.79 9.72 4.33 10.11 3.99 9.90

Writing 3.77 2.09 4.01 2.19 1.10 6.05 4.19 10.33 3.55 9.72

Total (%) 43.10 8.01 45.21 9.77 40.09 57.14 14.31 73.56 13.41 70.71

Oguntala et al. Employee Perception towards Cloud Computing in African States

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 251

The mean scores of the YouTube facilitated group are more than that of the traditional teaching.

The results suggest that the YouTube facilitated group outperformed the traditional class based

on the criteria for assessment. Next, Table 2 presents the results of the inferential statistics used

to identify the difference between the research groups in the test.

Table 2: Summary ANCOVA table for academic writing performance

SV SS’ Df MS’ F p

Pretest (writing) 775.91 1.00 775.91 58.1/0 .00*

Between (group) 858.48 1.00 858.48 18.31 .00*

Within (error) 2383.74 37.00 23.81

Total 68466.00 40.00

Corrected total 6751.60 39.00

*p<.05.

The analysis of covariance in Table 2 was conducted to compare the academic writing test

results between the YouTube facilitated and traditional teaching groups. Prior to this, the impact

of pretest differences on the results was eliminated. In-depth analysis reveals that the YouTube

group performed better on the average in the 20 marks awarded while learning the following

writing skills - grammar, vocabulary, organization, referencing, and overall writing (including

group assignment). The results from the ANCOVA show a significant difference in the total

scores for the academic writing tests between the two research groups. For instance, F (1, 40)

= 18.31, p = .00, partial = .11 (see Table 2 for details). The reasons for the improved

performance of the video group informed the choice of post-test interviews.

The purpose of the interviews was to understand the students’ point of views and unfold their

experiences of YouTube videos for academic writing. In fact, meanings are drawn from the

critical statements after which coding into categories to reflect an exhaustive description was

undertaken. The adopted procedure ensured the coding was submitted to a reviewer to compare

with the original to check data consistency and to validate the authenticity.

Some of the original statements from further qualitative analysis informed the formulation of

meanings which are below:

Table 3: Formulated meanings based on significant statements (YouTube facilitated

group)

Original statements

Formulated meanings

“My improved writing is helped by my initiating

an outline to guide how I organize and present

my essay. The tutors emphasized the role of an

outline in class teaching. Also, they provided

sample topics with similar shape themes.

However, the videos used in class elaborated

on sample sketches by providing links exclusive

to subjects earlier presented by the tutors.”

Participant appreciates and identifies

an attempt to select videos carefully to

correspond with class teaching for

seamless integration to take place

Oguntala et al. Employee Perception towards Cloud Computing in African States

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 252

“Even though the use of media seemed like an

additional burden initially, the time and effort

that I put in have been worth it. When I

received my marked essays and comments, I

was proud of my improvements and the entire

project was worth my while.”

Participant sees a correlation between

time spent on the videos and potential

to improve academic writing

performance

“The presentation style of the videos follows a

path or method and is done in a series that

highlight crucial steps in the writing process.

Remember that the length of the videos is short

hence only the key aspects are mentioned based

on the expert skills of the video presenters.

Similarly, my essay writing practice attempts to

follow a series of steps and organization.”

Participant identifies and evaluates a

learning approach based on a series

videos that highlight core steps of the

writing process that the respondent

translates into actual writing

“The videos create a platform for discussion of

examples, illustrations and other content with

tutors and fellow students on a scale that is

different from the regular class teaching.”

Recognition of enhanced student-tutor

and student-student interactions based

on the videos

“The videos even help improve my reading,

spelling and pronunciation of words that

hitherto I was unfamiliar with.”

Participant identifies the YouTube

video as reading and pronunciation

tools

“Regardless of what my overall scores are, the

various videos have increased my motivation

and interest to seek actively to improve my

understanding of grammar, vocabulary and

sentence structuring.”

Academic writing videos support

student’s motivation, interest, and

understanding of steps in writing

“The video sessions continue to attract my

regular attendance and participation in class

compared to the regular meetings without the

videos.”

The videos offer a platform for class

participation

Meanwhile, there is evidence of improved academic writing performance and a deeper

understanding of the writing process by the traditional teaching facilitated group. Whereas the

YouTube team used a focus group discussion and a limited number of interviews, the traditional

teaching led group was subjected to interviews only. Some of the critical statements from the

interview are below:

“This is my first experience with informal education, and it has opened me up to new writing

skills especially that I must organize my thoughts better before I start to write. The writing

sessions have improved my skills.”

“The weeks of lessons on brainstorming and outlining are applicable even in my social

conversation with peers and other contacts and the feedback is encouraging, to say the least.”

Oguntala et al. Employee Perception towards Cloud Computing in African States

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 253

“Academic writing is tight and has a set of rules and procedures but often I already know

what I want, and I can start writing.”

“I strongly agree that the academic writing classes helped me to write my essays better.”

“I am a lot more confident about my academic writing abilities and able to organize my

thoughts and writing for better reading by my graders.”

“The height of the classes for me was the last week of lessons where samples of essays were

presented, and we were able to read some of the review comments of the tutors and gain

feedback in a shared and relaxed learning space.”

“Academic writing is sophisticated, but I learned from the open consideration of sample essays

of peers and the class reviews tremendously improved my understanding of core principles and

my writing abilities.”

Although data collection focused on the students exclusively, for the purpose of equivalence to

manage better the flow of multiple tutors, moderators, observers and reviewers, these support

personnel appraised the contents and categorized codes. Thus, the support staff, based on their

review work, examination of records, observation of project participants and several meetings,

can validate several statements the respondents made. Some of the summaries of the support

staff are the following:

“Academic writing is an instructional strategy for helping the participants to organize their

thoughts and improve on writing. Even though this is an informal learning environment, it was

not easy for this team of young men and women, but week after week, they gave their best. The

progress is demonstrated in the essay scores. The two teams made a lot of achievement but the

YouTube group to a larger degree.”

“The post-test session held for the traditional teaching group provided a platform for

respondents to review and comment on another’s essays. Interestingly, respondents were able

to identify mistakes and underline perceived problems of non-native English speakers.”

“A pre-selection of YouTube videos on academic writing made content and connections

relevant to academic writing content areas for the test group, meeting students’ needs.”

The following section presents an analysis of the results regarding the research question 3.

Fitting YouTube videos into academic writing instruction

The aim of the research question 3 is to identify a framework to best support good practice of

YouTube videos to improve academic writing performance. The main findings support the

growing role of informal learning that offers a more balanced mix of learning content. The

following tables indicate the process of theme construction by an integration of multiple

formulated meanings and clusters of themes.

Oguntala et al. Employee Perception towards Cloud Computing in African States

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 254

Table 4: Theme one (Reactions)

Formulated meanings

Theme clusters

Emergent theme

Some participants fear the

YouTube videos are an added

burden

Initial fears about continued

access to the videos

Fear of additional stress

Anxiety over access to digital

media

Disruptive tendencies

Accessibility issues

Majority of participants in test

group feel motivated and

interested in exploring and

engaging digital media for

academic writing

Users access links to the

videos outside class hours on

their mobile devices

Motivation and interest

Continues engagement

24/7 access to videos

Table 5: Theme two (relevance)

Formulated meanings

Theme clusters

Emergent theme

Participants are familiar with

the viral nature of YouTube

video and digital media

culture for entertainment and

social purposes

Participants are aware that the

content of the selected videos

tallies with lesson outline

A good number of members

recognize that digital media

have educational value

Even though some

participants had used limited

media and e-learning

resources in their primary

education, use of YouTube

video resources was new

Popularity of YouTube videos

Awareness of efforts targeted

at complementing class

teaching with videos

Realization of media content

of YouTube videos for

academic writing

New experience

YouTube is a popular

culture

Relevance

Recognition

Oguntala et al. Employee Perception towards Cloud Computing in African States

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 255

Table 6: Theme three (Interactivity)

Formulated meanings

Theme clusters

Emergent theme

Even though participants use a

selected list of videos, they

often pay attention to features

such as “like”, “dislike”,

“number of viewers” and

read/post “comments” on

YouTube in addition to videos

Engagement and interaction

with other users

Interactivity and social

networking

Table 7: Theme 4 (Memory retention)

Formulated meanings

Theme clusters

Emergent theme

Participants repeatedly watch

selected videos in private

spaces

Affordances of YouTube

videos

Affordances – access

24/7, informal

Respondents preferred playing

back the videos when they got

stuck on their essay rather

than go through class notes

and handouts

Without reliance on natural

memory

Retention activities

Some of the significant observations and comments made by the support staff based on the

project are the following:

“Academic writing based YouTube videos relate students to learning content in a way that

they are used to inculcating instruction.”

“The video selection criteria included technical evaluation, recentness, content

categorization and classification and the video reduction procedure assisted the respondents

to see the connection between class lessons and those based on the new media.”

“A careful pre-selection of videos increased the focus on concepts that can be used in all

content areas of academic writing.”

“Based on the focus discussion, YouTube videos on academic writing may be an alternative

assessment technique with students.”

“Students view, comment and share videos on academic writing topics.”

Oguntala et al. Employee Perception towards Cloud Computing in African States

The African Journal of Information Systems, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article 2 256

“By drawing on videos that elaborate on skills and illustrations of academic writing,

organization of thoughts and methodical presentation of arguments and summaries, YouTube

can incorporate learning activity in schools.”

“Making YouTube video contents and connections relevant to academic writing activities,

learning objectives, class debates and discussions assist the learners by bringing purpose and

meanings to instruction.”

Discussion of results

The purpose of the section is to summarize the major findings and their implications.

Accordingly, the discussion is presented based on the research questions of the study.

The kinds and characteristics of experiences of student interactions with YouTube videos for

academic writing provide insights into differences of experiences regarding ways users engage

technology. Indeed, some of the accounts highlighted are strategic to the fitting of educational

videos on YouTube to learning and instruction. In other words, the assessment of the dynamics

of user experiences can inform the use of other digital formats and technologies for formal and

informal learning in multiple contexts. In short, the less satisfying encounters such as

disappointment or fear of additional burden leading to frustration can be associated with lack

of Internet access, bandwidth challenges, device issues, missing or unavailable files, poor

network services and copyright limitations on YouTube. Surprisingly, the results show limited

resistance to the exploration of YouTube site for academic writing education. Ultimately, the

reported contextual issues underline the need for improved understanding of terms, copyright

and fair use laws regarding the educational content of YouTube videos. In addition, others

reporting negative experiences offer a lever for a need to further understanding that should not

be ignored or overlooked. As expected, the scope of positive experience narratives includes

awareness, efficiency, team/collaborative learning. Also, anecdotes involved fun, exciting,

fascination, improved understanding of learning content, and appropriation of videos for pre-

writing activities. Therefore, YouTube videos as educational tools improve the experiences of

communication between teachers and students and among students. As a matter of fact, many

of the satisfying encounters are underlined by the affordances of the new media. Sundar &

Limperos (2013) propose a shaping of user needs based on affordances of media technology