NATHAN T. ARRINGTON

Classical Antiquity. Vol. 30, Issue 2, pp. 179–212. ISSN 0278-6656(p); 1067-8344 (e).

Copyright © 2011 by The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Please

direct all requests for permission to photocopy or reproduce article content through the University of

California Press’s Rights and Permissions website at http://www.ucpressjournals.com/reprintInfo.asp.

DOI:10.1525/CA.2011.30.2.179.

Inscribing Defeat:

The Commemorative Dynamics

of the Athenian Casualty Lists

Beginning ca. 500 bc, the Athenians annually buried their war dead in a public cemetery and

marked their graves with casualty lists. This article explores the formal and expressive content of

the lists, focusing in particular on their relationship to defeat. The lists created a monumental,

visual rhetoric of collective resilience and strength that capitalized on Athenian notions of

manhood and exploited conceptions of shame. For most of the fifth century, the cas ualty lists

were undecorated, austere monuments testifying to the endurance of the community. When

decoration began anew, the public reliefs, in contrast to private funerary reliefs, represented,

through imagery and setting, struggle rather than victory. The selective remembrance and,

paradoxically, frequent forgetting both enacted and enabled by the lists helped the Athenians

elide internal political strife and facilitated their repeated return to the fields of war.

Near the end of the mid-f ourth-cent ury Social War, Isokrates urged t he

Athenians to seek peace with her erstwhile allies and to embrace the principles of

Hellenic autonomy stipulated by the early fourth-century King’s Peace.

1

In his

text, Isokrates questions the profits of war and criticizes the aggression of the

fifth-century Athenian empire (arch

¯

e):

So far did [fifth-centu ry Athenians] surpass all men in foll y that whereas

defeats humble the rest of mankind and make them more sensible, they

did not teach those men a lesson. And yet they fell into more and greater

[defeats] during the period of their hegemony than occurred in the whole

This article is based in part on the third chapter of my dissertation, Arrington 2010a: 51–83. Earlier

versions were presented at Berkeley and Princeton, and I thank these audiences for their comments.

Michael Koortbojian, Julia Shear, and the journal’s two anonymous reviewers provided valuable

feedback on the article manuscript. A ll mistakes r emain my own.

1. See esp. Isok. 8.16.

classical antiquity Volume 30 /No. 2/October 2011

180

history of the city. . . . In the end they did not notice that they had filled the

public graves with their citizens.

2

In this passage, Isokrat es presents his read er or listener wi th two paradoxes. The

firstisthatthefifth-century Athenians, who envisaged themselves in art and t ext as

paradigms of s

¯

ophrosyn

¯

e (moderation), whose city Perikles described in a funeral

oration as the “school of Greece,” did not learn from defeat.

3

The second is that

the public graves, intended to preserve mn

¯

em

¯

e ( memory), were subject instead to a

collective l

¯

eth

¯

e.

4

Isokrates’ use of the word taphos rather than mn

¯

ema to describe

the tombs removes even the graves’ etymological relationship with memory.

5

The

orator also implies that there is a causal , or at the least a temp oral, relations hip

between the two paradoxes: the Athenians were so aggressive in their imperial

policy, so blind in their pursuit of power, that they failed to notice the human

cost of their undertaking. It is evident, though, that despite Isokrates’ qualifier “in

the end,” this act of forgetfulness could not have been performed only in the final

years of the fifth century. Rather, fighting, death, and l

¯

eth

¯

e went hand-in-hand.

Isokrates even leaves open the possibility of reconfiguring the causal relationship

between t he two paradoxes: the Atheni ans did not learn from their defeats because

they forgot thei r dead.

6

This rhetoric of forgetfulness should come as a surprise because, as Isokrates

well knew, in the fifth century the Athenians had a system for commemorating

military casualties. In each year of int erstate conflict the ashes of the war dead

were brought home, put on public display for three days, brought to the public

cemetery where a funeral o ration was delivered, buried in communal graves

marked by casualty lists, and given the tribute of funeral competitions.

7

These

practices were not common to all of Greece, since many ot her poleis buried their

2. Isok. 8.85–86, 88: τοσοτον δ δινεγκαν νοα πντων νθρπων στε τος μν λλους

α συμφορα συστ!λλουσι κα ποιοσιν "μφρονεστ!ρους, "κε#νοι δ$ ο%δ$ &π' το(των "παιδε(θησαν.

κατοι πλεοσιν κα μεζοσιν περι!πεσον "π τ+ς ρχ+ς τα(της τ.ν "ν /παντι τ.0 χρ1νω0 τ+2

π1λει γεγενημ!νων.... τελευτ.ντες δ$ 3λαθον σφ4ς α%τος τος μν τφους τος δημοσους

τ.ν πολιτ.ν "μπλσαντες.

3. Thuc. 2.41. 1.

4. Low 2010: 353–57 discusses this passage and the neglect of the public graves at Athens,

mostly drawing on the absence of references to the graves in literary texts. A treatment of forgetful-

ness already underlies the discussion of the war dead in Arrington 2010a. On collective memory,

most famously discussed by Maurice Halbwachs, see Coser 1992 and Cubitt 2007: 154–71.

5. Contrast, e.g., Dem. 18.208, where the public graves are mn

¯

emata. Since the dead lie

(κεμενοι) in these graves , it is clear that both a mn

¯

ema and a taphos could be filled. See also Pl.

Men. 242c, where the war dead are put (τιμηθ!ντες)inamn

¯

ema.

6. One might object that not noticing (3λαθον) is not the equivalent of forgetting, but that

objection does not account for the habitual act of forgetting required by the passage. By claiming

that the Athenians did no t notice that year after year they had filled their cemetery, Isokrates implies

that in any given year the Athenian s forgot the numbers and costs of the past years. Indeed, he does

not say that they did not notice that they were filling the cemetery (with a present pa rticiple), but that

they did not notice that they had already done so (w ith an aorist participle).

7. The most important treatments of various aspects of this nomos are Jacoby 1944, Stupperich

1977, Loraux 1981, Clairmont 1983.

arrington: Inscribing Defeat

181

dead on the battlefield.

8

In other words, the Athenians seem to have gone to

particular lengths to remember their dead. Is Isokrates, then, simply wrong?

The funeral orations delivered over the war dead suggest this may be the

case, for they repeat edly speak of the immortal glory—and hence memo ry—

of the deceased. Lysias says that their mn

¯

emai are ageless (ag

¯

eratoi).

9

He

praises the ancestors o f the dead for holding th at “a glor ious death leav es a

deathless account of brave men.”

10

Similarly, Perikles (via Thucydides) refers

to the undying (ag

¯

eron) praise the dead receiv e.

11

But the orators speaking

over the graves simultaneously throw the efficacy of memor y into question. All

funerary orations begin with a caveat on the limits of speech (logos) to recount the

memory of deeds (erga).

12

On the one hand, such comments serve to highlight

the magnitude of the erga, but they also reflect a real inability to fully render

an account in one speech of several events and many i ndividuals. And for the

most part the funeral orations do not attempt to render such accounts, instead

focalizing exploits from the (oftentimes distant) past.

13

Lysias fu rther makes th e

point that even eyewitnesses distort battlefield memories. When describing the

battle of Salamis, he claims: “Indeed because of t heir present fear they thought

that t hey saw many t hings they did not see, and that they heard many things they

did not hear.”

14

Coupled with these repeated warnings on the insuffici ency of

commemorative discourse and the frailty of personal recollection are injunctions

that survivors actually should forget the dead. Perikles urges the parents of the

dead to have children in order to forget their loved ones.

15

Lysias similarly pities

those who are too old to forget the dead, implying that forgetting the fallen was

the desired norm.

16

Isokrates’ statement, then, does not seem that far from the truth. Perikles

further undermines the view that the Athenian military ceremony successfully

preserved the memory of the dead when he questions the capacity of the public

graves an d their stelai adequately to record memory. In exp laining why the

memory of the war dead is undying, he shifts the locus of memory work from

the graves to individual minds and from written to unwritten testimony:

For the whole earth is the grave of famous men, and not only does the

inscription on stelai at home mark (s

¯

emainei) [them], but the unwritten

8. Com pare, for instance, the case of Sparta, where some war dead received graves in the city,

but most others were buried on or near the battle field: Low 2006.

9. Lys. 2.79.

10. Lys. 2.23: νομζοντες τ'ν ε%κλε4 θνατον θνατον περ τ.ν γαθ.ν καταλεπειν λ1γον.

11. Thuc. 2.43. 2.

12. Thuc. 2.35. 1–2, Lys. 2.1–2, Pl. Men. 237a, Dem. 60.1, Hyp. 6.2 (fragmentary).

13. For the “Tatenkatalog,” see Kierdorf 1966: 89–95.

14. Lys. 2.39: 5 που δι6 τ'ν παρ1ντα φ1βον πολλ6 μν 80θησαν 9δε#ν :ν ο%κ ε;δον, πολλ6

δ$ κοσαι :ν ο%κ <κουσαν.

15. Thuc. 2.43. 3.

16. Lys. 2.72.

classical antiquity Volume 30 /No. 2/October 2011

182

memory of their attitude rather than their deed dwells in each person’s

mind in foreign lands.

17

At first it may seem that the (imaginative) dynamics adumbrated in this passage

would increase th e memory of the dead. But when read more closely, the bravura

of the rhetoric exposes t he speaker’s awareness of the mnemonic limits of the

Athenian commemorative system. Since this passage is used to explain the reasons

the memory of the dead is immortal, the implication of the shift from monuments

to hearts is that the graves were not suffici ent in and of themselv es to preserve

that memory but necessitated a further unwritten memory. The importance of

the st elai recedes when they are juxtaposed with th e whole eart h and wi th every

mind in foreign lands. The commemorative capability of the stelai is thrown into

further doubt in the manner by which the verb s

¯

emain

¯

o is deployed in the passage.

The verb governs no direct object, leaving the reader or listener to wonder what

exactly these stones mark.

What, indeed, are the casualty lists, the constitutive elements of the Athenian

public burials, commemorating, and how are they commemorating it? This

immediately presents another question: what and how are t hey forgetting or

neglecting? Whether or not one accepts Isokrates’ v iews, the fact remains that

no monument or group of monuments ever can provide a comprehensive history

of past events. To the extent that the monuments emplot a particular narrative,

gaps inevitably will be present. As Marc Auge´ eloquently put it, “Memories are

crafted by oblivion as the outlines of the shore are created by the sea.”

18

But

the forgetting, the omitting, and the eliding involved in public commemoration

should not be envisaged as something as routine, predictable, and benign as a

wave lappin g a beach. As Isokrat es suggests, forgetfulness could be a strategy

with profound consequences. More importantly, commemoration does not entail a

simple give and take between forgetting or remembering, an either/or scenario.

Defeat an d loss could be reconfigured, transformed, and framed to be remembered

in a particular manner.

This article seeks to uncover the commemorative dynamics of the Athenian

casualty lists. More specifically, it investigates the collective Athenian response

to d efeat and death in the fifth century, the period to which most of the surviving

lists belong, by exploring the narrative the stelai emplotted at Athens. An analysis

of the content, form, and setting (socio-cultural, topographic, and political)

17. Thuc. 2.43.3: νδρ.ν γ6ρ "πιφαν.ν π4σα γ+ τφος, κα ο% στηλ.ν μ1νον "ν τ+2 ο9κεα

σημανει "πιγραφ, λλ6 κα "ν τ+2 μ= προσηκο(ση2 γραφος μνμη παρ$ >κστω0 τ+ς γνμης

μ4λλον ? το 3ργου "νδιαιτ4ται. For the translation of γνμη as “attitude,” see Rusten 1989: 148.

18. Auge´ 2004: 20. Cf. Ricoeur 2004: 85: “Memory can be ideologized through the resources of

the variations offered by the work of narrative configuration. . . It is, more precisely, the selective

function of the narrative that opens to manipulation the opportunity and the means of a clever strategy,

consisting from the outset in a strategy o f forgetting as much as in a strategy of rem embering.”

arrington: Inscribing Defeat

183

of the casualty lists shows how they commemorated collective courage and

sacrifice, alternately marking and eliding d efeat to create a v isual rhetoric of

collective resilience and continuous struggle (ag

¯

on). The expressive capaci ty

of the casualty lists reveals how the public commemoration of the war dead

was an active rather than a passive process. The ceremony, with its burial

and oration and games, was an active response to a situation that challenged

the integrity and confidence of the community and an active effort to creat e,

in monumental form, an aggressive, unifying narrative about Athens and the

Athenians.

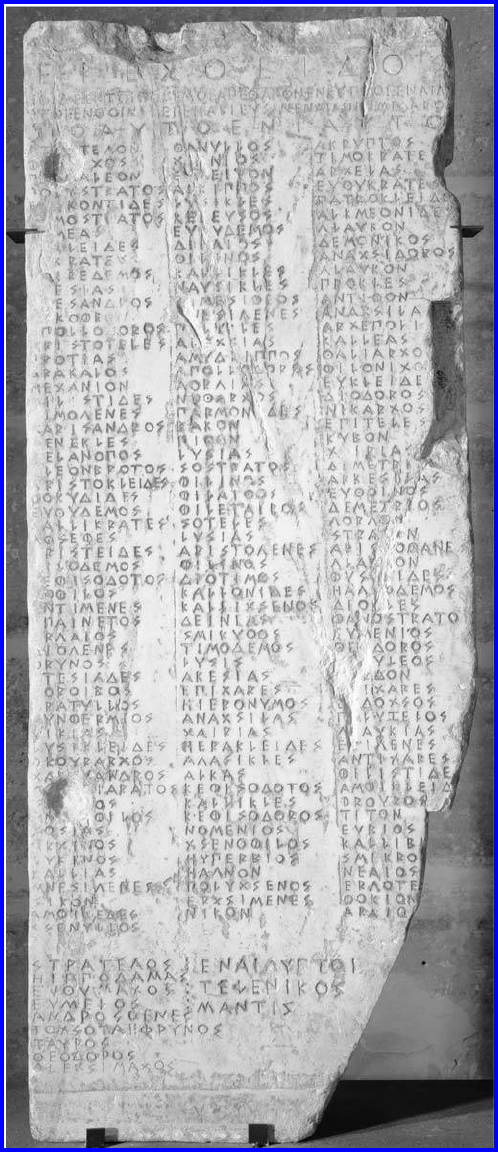

THE FORMAT OF THE ATHENIAN CASUALTY LISTS

The casualty lists were erected in the d

¯

emosion s

¯

ema, the public cemetery,

every year in which there were war dead (Figure 1).

19

The format of the lists varies

in details, but typically they begin with a heading, “These men died,”

20

sometimes

specifying “in the war,”

21

“of the Athenians” in the genitive,

22

or “Athenians” in

the nominative,

23

once adding “in the same year,”

24

and often incl uding in the

heading references to the location of the battles.

25

Geographical rubrics also can

appear as subheading s,

26

or the location of the battle may be enunciated in the

epigram on the base.

27

On one occasion a cat ch-all “These men died in the other

battles,” without geographical specifications, concludes a list.

28

There might be

an epigram on t he top of the stele,

29

on the bottom of the stele,

30

or (perhaps more

commonly) on the base into which the stele was set.

31

The names of the dead

were written without patronymics and organized according to th e t en Attic tribes

established by Kleisthenes. On eleven stones one or more names are preceded

19. On the d

¯

emosion s

¯

ema, see Arrington 2010a: 17–50; Arrington 2010b. On the Athenian

casualty lists, see esp. Bradeen 1969; Stupperich 1977: 4–22; Clairmont 1983: 46–54; Pritchett

1985: 139–40; Lewis 2000–2003; Low 2010; Low forthcoming.

20. IG I

3

1147, 1148, 1162, 1166, 1183, 1191, 1193 bis; IG II

2

5221 and 5222 (for cavalry). I do

not include SEG 48.83 in this description of content because the full publication of the stele has

not yet appeared.

21. IG I

3

1147, 1166, 1191.

22. IG I

3

1162, 1183, 1193 bis; IG II

2

5221.

23. IG I

3

1191.

24. IG I

3

1147.

25. IG I

3

1147, 1162, 1183; IG II

2

5221, 5222 (for cavalry).

26. IG I

3

1144, 1180, 1184; IG II

2

5222 (for cavalry).

27. IG I

3

503/4, 1179.

28. IG I

3

1162, ll. 41–42. Cf. SEG 52.60, l. 33.

29. IG I

3

1148; SEG 48.83, 49.370.

30. IG I

3

1162.

31. IG I

3

503/4, 1163d-f, 1179; so, too, on the public bases (not for casualties) 1154b and 1178.

IG I

3

1142, 1143, 1167, 1170, 1173, 1181 have epigrams and may be bases for casualty lists. IG

I

3

1148 bears an epigram but is too mutilated to identify as a base rather than a s tele.

classical antiquity Volume 30 /No. 2/October 2011

184

by an iden tifying l abel, such as “trierarch.”

32

Occasionally non-A thenians and

servants or slaves were included on the lists.

33

The lists were carved out of marble, usually identified as Pentelic. They

sometimes preserve flat undersides that were set upon a base or i nto long slots

cut into a base.

34

Vertical do wels could be used to secure them in place: IG I

3

1186 and SEG 52.60 preserve dowel holes on their undersides,

35

and on the l ong

base IG I

3

1163d-f there are four cuttings for vertical dowels (Figure 2 ).

36

A

stele with inscription and figural relief found east of the Larissa train station, near

Palaiologou Konstantinou street and herein referred to as the Palaiologou stele

and relief (SEG 48.83), is dated to the 420s bc and is the first list with a tenon. The

only other is IG I

3

1191, dated to the late fifth century.

The earliest example of crown ing decoration for a list (ap art from a mo lding)

is preserved only in the report of a lost drawing. A. Boeckh in CIG describes

having seen a drawing in U. Koehler’s papers made by L. F. S. Fauvel of a

frieze associ ated with the l ist for the dead from Poteidaia (IG I

3

1179, 432

bc).

37

According to Boeckh, the drawing depicted three warriors fighting on a

slab above the base for the casualty list of Poteidaia dead. Fauvel’s transcription

of the epigram has been found, but not the drawing, and it is quite possible that

the relief never belonged with the monument. The earliest surviving example of

crowning decoration is the Palaiologou relief (SEG 48.83), dating to the 420s and

described in detail below. The cuttings on the top of the lists also speak against

32. σ@τ[ρα]τεγAν (IG I

3

1147, l. 5), στρατεγ1ς (idem, l. 62), τοχσ1ται (idem, l. 67), μντις

(idem, l. 129); στρατεγ1ς (IG I

3

1162, l. 4); τρι!ραρχος (IG I

3

1166, l. 2); τοχσ1ται (IG I

3

1184, l.

79); [———τρι]!ραρχος (IG I

3

1186, l. 75), [——περι]π1λαρχος (idem, l. 77), ταχσαρχος (idem,

l. 79), τ1χσαρχος (idem, l. 80), τρι!ραρχος (idem, l. 108); τρι! (sic, IG I

3

1190, ll. 3, 42), φυσικ1ς

(idem, l. 152), φ(λαρχ (idem, l. 179); [τ ....αρ]χBος (IG I

3

1191, ll. 33, 200), [τ....]αρχος (idem,

l. 35), [τρι!ρ]αρχος (idem, ll. 37, 39, 41), [τρι!ρα]ρχος (idem, l. 43), τρι!ρ[αρχοι] (idem, l. 56),

hοπλ[#ται] (idem, l. 60), ρχAν

τA ναυτικA (idem, ll. 105–106, 108–109), ταχσαρχος (idem, ll.

111, 113), τρι!ραρχος (idem, ll. 115, 117, 119, 121), [τ....αρ]χος (idem, l. 198), [τρι!ραρ]χBος

(idem, l. 202); [τρι!ραρχ]ος (idem, l. 204); τρι!ραρχ (IG I

3

1192, l. 8), τρι!C[ρ]αρχ (idem, l. 34),

Dιππο[τοχσ1τες] (idem, l. 158); στρατηγ1ς (IG II

2

5221, col. VI (l. 2), [σ]τρατηγ1[ς] (idem col.

XI 1. 2); φ(λαρχος (IG II

2

5222); hippotoxot

¯

es (SEG 48.83, unpublished).

33. Foreigners (not including instances of non-Athenian nam es, e.g. IG I

3

1158, ll. 3, 5, 7):

[Μαδ](τιοι (IG I

3

1144, l. 34), [Βυζ]ντιο[ι] (idem, l. 118); ’Ελευθερ4θεν (IG I

3

1162, l. 96);

[τοχσ1ται βρβ]αροι (IG I

3

1172, l. 35); [χ]σ!Cνοι (IG I

3

1180, l. 5), [β]Hρβαροι [τ]οχσ1ται (idem,

ll. 26–27); 3νγBρIαH[φοι] (reading very disputed, IG I

3

1184, l. 76), χσ!νοι (idem, l. 89); χσ!νοι (IG

I

3

1190, l. 65), τJο[χσ]1ται [β]ρβJαροι (idem, ll. 136–37); τοχ[σ1ται] βρβα[ροι](IG I

3

1192, ll.

148–49). Servants or slaves: [θ]ερπονKτJες (IG I

3

1144, l. 139); Paus. 1.29.7. On the question of

the inclusion of rowers on the lists, see Strauss 2000.

34. Flat undersides: IG I

3

1147, 1150, 1156, 1184, 1186, 1190; SEG 52.60; bases with slot

cuttings: IG I

3

503/4, 1178; base without slot cuttings: IG I

3

1163d-f.

35. The dowel holes on the underside of IG I

3

1186 are not noted in IG I

3

but described in

Mastrokostas 1955; see esp. Mastrokostas 1955: 182–83, figs. 1–2.

36. On vertical fastening systems, see Orlandos 1959–1960: 189–202.

37. CIG I, p. 906 (supplement to no. 170); Ho¨lscher 1973: 104–105, 263n.540; Stupperich 1977:

16–17; Clairmont 1983: 174–75. Stupperich 1978: 92–93 speculates that it might be associated with

the relief in Oxford, on which see further 197–98, below.

arrington: Inscribing Defeat

185

crowning decoration on the lists for most of the fifth century. The only dowel

holes for vertical attachments on the lists are on the late fifth-century list IG I

3

1186 and the Palaiologou stele itself, where it probably secured an anthemion

above the figural relief.

38

Thus the practice of adorning the casualty lists with

sculpture cannot be shown to have existed before the last third of the fifth century,

around the same time as private funerary sculpture also began anew. For most

of this century, the lists were austere: either completely undecorated or crowned

only by a simple molding.

39

The absence of figural decoration carries importan t

implications for the semantics of the lists, including their relationship to private

art, that will be addressed in greater detail later in this article.

The tribal organization of the names indi cates that the practice of erecting

casualty lists must postdate Kleisthenes’ reforms of 508/7 bc.

40

A casualty list

in Attic script with a tribal heading found on Lemnos dates to the early fifth

century and probably commemorates the Athenians who died under Miltiades

in 498.

41

Fragments of the tribal casualty lists once decorating the soros for the

Marathonomachoi were found at the villa of Herodes Atticus at Eva Loukou.

42

At

Athens itself, in the area of the d

¯

emosion s

¯

ema, there was a base for the casualty

lists for the Marathonomachoi,

43

and Pausanias mentions graves from a conflict

with Aigi na that he specifies occurred before the Persian invasion.

44

Also from the

public cemetery is a possible tumulus for the war dead dating to the first quarter of

the fifth century.

45

We can conclude that the format of the lists was in place ca. 500

and t hat the habit of erecting casualty lists at Athens began ca. 500, although in

this early stage of the nomos not all the war dead were buried at Athens.

According to Pausani as’ descrip tion of the d

¯

emosion s

¯

ema, the lists were

set up t hroughout the fourth century. He even describes a grave for Athenians

who aided the Romans against the Carthaginians.

46

Few examples later than

38. IG I

3

1161 has a roundish hole in the center of the upper surface not noted in the IG I

3

publication, and it is probably modern. For vertical attachments to stelai, see IG I

3

35, 40; SEG

28.46; Lawton 1992; Hildebrandt 2006: 106–107, 355–56, 369–70, nos. 292 (IG II

2

6007), 328

(IG II

2

6609).

39. Several scholars have instead thought that friezes were a regular f eature of the casualty lists:

Brueckner 1910: 193 (but cf. his comments on the sober appearance of the graves on 211); Clairmont

1972: 54–55; Loraux 1981: 51; Pritchett 1985: 157; Rawlings 2007: 199. See also Stupperich 1994,

for a view of lavish artistic display in the d

¯

emosion s

¯

ema. Some might cite as an example of public ar t

earlier than the last third of the fifth century a relief for Melanopos and Makartatos, w hich Pausanias

describes in the d

¯

emosion s

¯

ema, but it is probably a private relief. It is discussed below.

40. See Arrington 2010b: 503–506 for a fuller discussion of the start date of public burial in

the d

¯

emosion s

¯

ema and the related practice of erecting casualty lists.

41. IG 12 Supp. 337.

42. SEG 49.370, 51. 425, 53.354, 55.413; Steinhauer 2004–2009; Steinhauer 2009: 122; Spy-

ropoulos 2009.

43. IG I

3

503/4; Matthaiou 2003: 197–200; Arrington 2010b: 505–506.

44. Paus. 1.29.7; it may have been in 491/0 or 487/6.

45. Stoupa 1997: 52.

46. Paus. 1.29.14. On the date of the event, probably ca. 200 bc, see Pritchett 1985: 148–

49n.164. Bradeen 1964: 58 doubts the veracity of the event.

classical antiquity Volume 30 /No. 2/October 2011

186

the fifth century, though, survive. D. W. Bradeen proposes that one inscription,

with a tribal heading and the r ubric for a general, belonged to the casualty list

for Chaironeia.

47

S. Dow has also suggested some candidates for fourth-century

lists.

48

Yet the latest securely dated casualty list is for the dead from battles in

Corinth and Boiotia in 394/ 3.

49

There are two possible explanations for the dearth of fourth-century lists,

which are not necessarily mutually exclusive. The firstisthatperhapssometimein

the fourth century the names began to be inscribed on the lists in a differen t manner

than before, which has made them more difficult to identify. For instance, the

demotic may have been included at this point,

50

which would explain Pausanias’

testimony that the casualty lists included the deme, which is at odds with our

fifth-century remains.

51

However the change in recording manifested itself, it

would have coincided with a change in conscription. In the fifth century, a general

or generals drew up katalogoi of eligible hoplites by tribe, based on lists provided

by demarchs, and with the help of each tribe’s t axiarch. Sometime between

386 and 366, the hoplites were conscripted instead by age classes from one

master list.

52

It is likely that the same lists were used both for organizing the

muster roll and for creating the casualty lists. Thus the chan ge in the epi graphical

record may reflect the change in the conscription process. The second explanation

for the absence of fourth-century lists may be the location of Athenian rescue

excavations, which have fallen mostly along the lines of the ancient roads. Less

work has been done in the space between th e roads.

53

Not only did the public

cemetery certainly extend into t his area, but this region may have been less

plundered.

54

The graves immediately alongside the road were a more convenient

source of raw material than those off the beaten track. If many fourth-century

state graves lay between the road that ran from the Dipylon Gate and the road

that went from a gate at modern Leokoriou and Dipylou streets, then there may

be some hope that future excavations will uncover more of the fourth-century

casualty lists.

47. Bradeen 1964: 55–58; SEG 21.825; Bradeen 1974: 33–34, no. 25. Bradeen 1974: 33, no. 24

also puts a base for casualty lists in th e fourth century.

48. Dow 1983: IG II

2

2364 (=I

3

1039), 2365 (=I

3

1045), 2368, 2376 (according to Dow, ca. 400);

2426 (=I

3

516, according to Dow, fourth century); 2399 (according to D ow, mid-fourth century);

2392 (=2404, according to Dow, after the m id-fourth century). Lewis 2000–2003: 15–17 discus ses

how I

3

516, 1039, and 1045 belong in the fifth century, and II

2

2392 in the first half of the second

century.

49. IG II

2

5221 and, for cavalry of the same year, IG II

2

5222.

50. Lewis 2000–2003: 17.

51. Paus. 1.29.4: στ+λαι τ6 Lν1ματα κα τ'ν δ+μον >κστου λ!γουσαι.

52. This reconstruction of the conscription process follows Christ 2001.

53. S ee the maps plotting the rescue excavation locations in Arr ington 2010a: 224–25.

54. Lewis 2000–2003: 17 suggests along slightly different lines that a section of th e cemetery

reserved for the fourth-century grav es was covered in antiquity. Th us the lists from that section were

not reused for construction material.

arrington: Inscribing Defeat

187

A ‘‘RHETORIC OF MANHOOD’’

55

The stones name and th ereby commemorate the dead. Yet they stress certain

aspects of their identity over others: the dead are Athenians,theyaremen,andthey

died fighting. Lacking demotics and patronymics, the names become a collective

unified under the heading, “These of the Athenians. . . .” The organization of

the lists by Kleisthenic tribes points to the democratic ordering of Attica and

suggests that the Athenians are categorized and conceived on the stones primarily

as democratic citizens.

56

The democratic ideology at work on the lists rarely

praises one type of Athenian over another, nor does it privilege a citizen over a

non-citizen who died for the city. A hoplite is listed above an archer; foreigners

are included, as are slaves.

57

The concept of “Athenian” at work here is broad.

The lists on the stones create a collective made possible by democratic ideals,

but it is a collective whose common denominator is not Athenian citizenship per

se but service with the Athenian army. Accordingly, as opposed to other city

lists that identify their dead with patronymics or even with a reference to their

victories in panhellenic competitions,

58

thereby using extra-polis competition to

denote vir tue, the few rubrics accompanying t he Athenian names refer to military

rank. The tie that binds is military service for the city.

It is a rhetoric of manhood, then, that we find on the Athenian casualty

lists. For not only do the lists present the casualties as a collective of men

who served in the military, but as men who proved their manliness by facing

danger and dying while fighting. The epigrams on the lists make this point. The

epigram heading the casualty list from the Marathon soros found in reuse at the

villa of Herodes Atticus at Eva Loukou claims that ph

¯

emis will tell “how they

died fighting with the Medes . . . the f ew against many.”

59

An epigram for the

dead perhaps from 447 begins, “These men by the Hellespont lost their brilliant

youth fighting.”

60

Similarly, an epigram for cavalry concludes by stating that

55. I take the phrase “rhetoric of manhood” from the title of Roism an 2005.

56. Loraux 1981 stresses the anonymity and collectivity of the dead on the lists. However, her

analysis primarily centers on the articulation of a uniform and ideal democratic ideology via the

funeral orations. See esp. Loraux 1981: 22–24.

57. Loraux 1981 discusses the democratic aspect of the lists, while Low 2010 argues that an

emphasis on the connection between democracy and the lists can oversimplify their purpose and

reception; similarly Low forthcoming.

58. Patronymics were included on a stele in the Samian agora for the dead from the battle at

Lade (Hdt. 6.14.3) and on the stele er ected at Sparta listing the casualties from Thermopylai (Paus.

3.14.1). They also occur on surviving lists from Megara, Mantineia, Thebes, and Corinth. A Thasian

decree stipulates that the war dead are to be listed with patronymics. The Thespian lists identify

panhellenic victors. See Pritchett 1985: 140–41 and Low 2003 for non-Athenian lists, and for the

Thasian decree see most recently Fournier and Hamon 2007.

59. [μ]αρνμενοι Μ!δοισι ...[π]αυρ1τεροι πολλAν δεχσμενοι π1λεμον (ll. 4–5). The complete

text is in Steinhauer 2004–2009: 680.

60. IG I

3

1162, ll. 45–46: hοδε παρ$ hελλ!σποντον π1λεσαν γλα'ν h!βεν βαρνμενοι.

classical antiquity Volume 30 /No. 2/October 2011

188

they lost their youth “fighting against hordes of Greeks.”

61

In each case the

present participle marnamenoi is coupled with a verb for dying in the aorist

to describ e how the men died: with cour age. The value p laced on fighting

until the very end of one’s life recalls the rhetoric of manhood evoked in epic

poetry, such as Kalli nos’ admonitio n, “Let each one, with his last b reath, hurl

his spear.”

62

A similar rhetoric of manhood permeates the funeral orations, which were

delivered in the presence of the casualty lists.

63

Repeatedly the speeches use the

phrase

νδρες δ$ γαθο γεν1μενοι to indicate that the men were courageous in

death.

64

Death was not a prerequisite for being agathos,

65

but in facing danger one

gave proof of one’s bravery and valor, one’s aret

¯

e. References to danger perv ade

the speeches. Lysias, for instance, deploys

κινδυν- 39 times. By heightening th e

risks the men of the recent and distant past faced, he underscores their courage. For

instance, when praising the men who fought at Plataia, he says they made Greece

free and “in all the dangers gave proof of their valor.”

66

This manly ch aracter

in face of danger, rather than the outcome of the battles, is what the orators stress.

It is the ethos of the fallen that the orators want the listener to remember.

67

To

put it differently: t he ethos that was r evealed in deeds, not the deeds themselves,

rendered the fallen memor able. Lysias near the end of hi s speech gen eralizes

that the war dead “leave behind an immortal memory because of their aret

¯

e.”

68

Similarly, Hyperides say s that they “have become memorable becau se of t heir

andragathia (bravery).”

69

Such an emphasis on characteristics of manl iness like

andragathia, tolm

¯

e (daring), and aret

¯

e may explain why Plato, in his spoof on

a funeral oration, describes fathers of the dead with virile hyperbole as “manly

fathers of men.”

70

If one purpose of the discourse on courage was to elicit admiration in the

mourners for the dead, another (closely related) purpose was t o exploit their sense

of shame.

71

Shame was what the dead had escaped.

72

As Perikles says, the dead fled

61. IG I

3

1181, l. 4; Anth. Pal. 7.254: πλεστοις hελλνον ντα μαρνμενοι.

62. K allin. fr. 1 (West), 5: κα τις ποθνσκων Mστατ$ κοντιστω.

63. On the importance of the orations being spoken in the presence of the lists, see below.

64. E.g., Lys. 2.25 and Pl. Men. 237a.

65. Contra Loraux 1981: 98–100. Lysias, for example, describes the enthusiasm of both old and

young for conflict during the First Peloponnesian War (Lys. 2.50–51). In both cases, he is describing

the attitude of living persons. The elder generation has courage (aret

¯

e) bred from experience; they

have proved themselves brave on many occasions (πολλαχο γαθο γεγενημ!νοι). They did not die

in the process of becoming agathoi.

66. Lys. 2.47: "ν /πασι δ το#ς κινδ(νοις δ1ντες 3λεγχον τ+ς >αυτ.ν ρετ+ς.

67. Loraux 1981; Roisman 2005: 70.

68. Lys. 2.81: θνατον μνμην δι6 τ=ν ρετ=ν α&τ.ν κατ!λιπον.

69. Hyp. 6.29: μνημονευτος δι6 νδραγαθαν γεγον!ναι.

70. Pl. Men. 247e: πατ!ρας Nντας νδρας νδρ.ν.

71. On shame, see Roisman 2005: 64–83, esp. 67–71, where he discuss es shame and military

defeat in the funeral orations.

72. Roisman 2005: 70.

arrington: Inscribing Defeat

189

dishonor.

73

Demosthenes, entrusted with the difficult task of praising the fallen

from the Athenian defeat at Chaironeia, is at pains to show how their conduct

rather than the outcome of the battle ensures their reputation: the fallen chose

a beautiful death (thanatos kalos) rather than a shameful life (bios aischros).

74

Shame was not just something to be escaped, then, but a force that motivated them.

The men at Chaironeia chose death “because they reasonably f eared the shame of

future reproach.”

75

When they perceived they were losing, they had to die fighting

the enemy so that they would not suffer shame.

76

And before the moment when

one’s honor compelled one to face death, shame could galvanize one to wage

war in the first place. In the Persian Wars, Lysias explains, the Athenians went to

battle because they were ashamed (aischynomenoi) that barbarians were on their

land.

77

This motivating or, at the least, didactic power of shame was articulated

to the living via the casualty lists.

78

Survivors who had not proved they could face

death would have been ashamed at t he sacrifice inventoried on the stones. Those

Athenians, for example, who ran away at the Battle of Mantineia in 418,

79

must

have been particularly abashed when they stood before that year’s stelai. In 330,

when Lykourgos charged Leokrates with treason for having fled Athens shortly

after her loss at Chaironeia, he expressed amazement that Leo krates did not feel

shame at the elegies on the casualty lists.

80

The rhetoric of the stones, though, was

not reserved for such cowards. Athenian men who had fought valiantly and those

who had not fought because of young age or because of where they were stationed

would have feared future shame: perhaps they might not hold the line and face

death when the moment came, but throw their shield and run. In Plato’s oration,

the dead themselves warn the living that nothing is worse than being honored

because of one’s ancestors’ glory.

81

COMMEMORATING EVENTS, COMMEMORATING DEFEATS

Not only did the names on the lists lack patronymics and demotics, but

on many lists the same name was repeated. For instance, on IG I

3

1147, for

the tribe Erechtheis, the name Glaukon appears three times. We know from

lekythoi images that women visited graves, but the widow looking to find the

73. Thuc. 2.42.4: τ' μν α9σχρ'ν το λ1γου 3φυγον. The scholiast glosses this phrase with

τ' Lνειδζεσθαι Oς δειλο.

74. Dem 60.26.

75. Dem. 60.26: ε9κ1τως τ+2 τ.ν μετ6 τατ$ Lνειδ.ν α9σχ(νη2.

76. Dem. 60.31: τ1τε τος "χθρος μυν1μενοι τεθνναι δε#ν P0οντο, στε μηδν νQιον

α&τ.ν παθε#ν.

77. Lys. 2.23.

78. Low 2010: 351–52 briefly discu sses how the lists could shame A thenians into military

service.

79. Thuc. 5.72. 4.

80. Lykourg. Leok . 142.

81. Pl. Men. 247b.

classical antiquity Volume 30 /No. 2/October 2011

190

name of her spouse on a public list would not have been able t o i dentify which

name belonged to him. While this anonymity of the individual dead was used to

subscribe him into a collective identity of military men, it also means that the

stelai commemorated simultaneously indi viduals and the events in which they

fell. In other words, as the personal identity of the dead faded, the specificity

of the event marked by the stone sharpened. The connection to the event on

the casualty lists was emphasized through the inclusion of geographical rubrics.

Unlike the listing of the names of the dead, the regions of conflict were clearly

identified in the heading proper, in subheadings, or i n an epigram. This is one of

the instances where the distinction between modern (i.e., post-World War I) war

memorials and the ancient lists is most distinct. While any war memorial must

commemorate both people and events, most modern war memorials throw their

commemorative effort into marking th e names of t he dead. Specific information

such as a date of birth or a date of deat h often is supplied, and a site index

routinely is available to help visitors locate loved ones. The Athenian casualty

lists, on the other hand, with t heir enumeration of anonymous dead coupled

with their specification of locale, mar k both indiv idual and event, and it is even

possible that they commemorated the event more than the individual. Unlike

modern memorials, the Athenian stones were erected shortly after the battles in

which the men had died: every winter following a season of military conflict. Thus

memories of the events were still fresh for mourners who gathered at the lists.

In this tempo ral cont ext, it is inconceivable that th e ancient monuments could

completely shift their commemorative duty from event to individuals.

Yet this relationship between monument and event presented a problem for

the Athenians, since many of the events commemorated by the lists were not

cause for celebrations.

82

Nearly every year, the stones marked defeats, some

of t hem minor setbacks, ot hers major disasters. The connection between defeat

and casualt y lists, in fact, ran deep, because in Greek hoplite warfare, casualties

indexed defeat. The winning side regularly had fewer casualties than the losing

side;

83

the more Athenian dead on the list, the more likely it was that they had lost

the engagement. A large monument in the cemetery suggested the absence of a

triumph. Moreover, the request to recover one’s dead constituted the (required)

official admission that one had lost the battlefield. The Athenian mind, then,

readily would have associated the dead with defeat. This thinking would have

been encouraged by the prevalent conception, colored by epic, of battle as a set

of confrontations between individual warriors.

84

Evidence for t his mindset can

be found in Athenian art contemporary with the lists, for it has often been noted

that, despite the fact that the Athenians fought in phalanx formation, this cohesive

unit is absent from Classical Athenian art. Instead, the Athenians dep icted war

82. Low 2010: 350, 356–57 also notes the relationship of the lists to defeat.

83. Krentz 1985.

84. For the impact of epic on ancient warfare, see Lendon 2005.

arrington: Inscribing Defeat

191

along epic lines, distilling group battles into individual combats in which one

figure won victory and glory from the other.

85

The close relationship between

athletics and war only deepened the cognitive fragmentation of phalanx warfare

into one-on-one encounters. This mindset carries significant ramifications for the

Greek view of the lists, for it implies that the individual dead have lost their

individual fights.

The casualty lists, then, because of the anonymity of the dead, the connection

to events, the nature of hoplite warfare, and the Greek conception of combat in

epic terms, could be seen as monuments of defeat. Indeed, to appreciate the impact

of military setbacks on the lists, one only need turn to Pausanias’ description of

the public cemetery. As he wandered through the d

¯

emosion s

¯

ema, he recorded

polyandria (graves with multiple war dead buried together) and casualty lists from

the following list of serious setbacks.

Drabeskos (464): as many as 10,000 Athenian and allied settlers were

slaughtered unexpectedly.

86

Tanagra (458/7): the Athenians lost to the Lakedaimonians and their

allies, with heavy casualties on both sides. In the course of the battle,

the Thessalian cavalry switched to the Spartan side.

87

Koroneia (447/6): the Boiotians and their allies defeated the Atheni-

ans. Following the loss, the Athenians evacuated Boiotia, whose cities

regained their independence.

88

Delion (424/3): after the Boiotians failed to betray cities to them, the

Athenians were defeated near the sanctuary of Apollo at Deli on, then

again at the sanctu ary itself. Some Athenian dead were gathered onl y

after 17 days. Almost 1000 Athenian hoplites fell including the general,

compared wit h 500 Boi otians.

89

Amphipolis (422): about 600 Athenians, including Kleon, fell and only

seven Lakedai monians.

90

Mantineia (418): 700 Argives and their allies, 200 Mantineans, and

200 Aiginetans and Athenians, including both generals, perished in a

loss where apparently no Spartan allies and perhaps 300 Spartans fell.

Following the defeat, the Argives concluded an alliance with Sparta, now

dominant in the Peloponnesos.

91

85. For the epic concept that victory and glory belong to one side or th e other, see, e.g., Hom. Il.

12.328, 13.303, 22.130.

86. Hdt. 9.75; Thuc. 1.100.3, 4.102. 2; Diod. 11.70.5; Paus. 1.29.4.

87. Thuc. 1.107; Diod. 11.80; Plut. Kim. 17. 3–6, Per. 10.1–2; Paus. 1.29.6.

88. Thuc. 1.113. 2–4; Diod. 12.6; Plut. Per. 18.2–3; Paus. 1.29.14.

89. Thuc. 4.89–101.2; Pl. Lach. 181b, Symp. 220e-221b; Diod. 12.69–70; Cic. Div. 1.54.123;

Str. 9.2.7; Plut. Alk.7.4,Mor. 581e; Paus. 1.29.13.

90. Thuc. 5.7–11, Diod. 12. 74, Paus. 1.29.13, Polyain. 1.38.3

91. Thuc. 5.65–74, 5.76; Diod. 12.78–79; Paus . 1.29.13.

classical antiquity Volume 30 /No. 2/October 2011

192

Sicily (413): t he Athenians lost a significant portion of their fighting

force in the night battle at Epipolai, in battle in the harbor at Syracuse, in

the subsequent retreat, and when imprisoned. Numbers are difficult to

come by, but the force sent i n 415 consisted of 100 Athenian ships, 1500

Athenian hoplites, and 700 Athenian thetes as marines. We later hear

of 250 Athenian cavalry. Reinforcements consisted of Eurymedon’s 10

Athenian ships and Demosthenes’ 60 Athenian ships and 1200 hoplites.

Thucydides bluntly sums up the disaster, “Few of many returned home.”

92

Corinth and Koroneia (394/3): the Athenians and their allies succumbed

to the Spartans at Corinth and fled the scene at Koron eia.

93

Olynthos (349): the city, despite Athenian support, fell to Philip II.

94

Chaironeia (338): Boiotians and Athenians (together with other allies)

lost the field to Philip II and his son, Alexander. According to Diodoros,

more than 1000 Athenians were killed and over 2000 were taken prisoner.

Pausanias states that “the disaster in Chaironeia was the beginning of

trouble for all Greeks.”

95

Pausanias also describes polyandria of men who were not attended by good

fortune (

ο%κ "πηκολο(θησε τ(χη χρηστ): those wh o attacked Lachares when

he was tyrant (before 295), and those who plotted to seize Piraeus from the

Macedonians but were betrayed before their attempt (probably between either

322 and 307 or 295 and 287/6).

96

Some notable Athenian disasters not mentioned

by Pausanias were the expedition to Egypt (454), when 200 Athenian and allied

ships were lost and most of the 50 ships of a relieving force,

97

and the battle at

Aigospotamoi (405), when only 9 ships out of 180 escaped, which precipitated

the Athenian surrender that concluded the Peloponnesian War.

98

By commemorating their war dead in a public space, the Athenians risked

celebrating their living, victorious opponents. This conceit—the triumph of living

victor over dead foe—can be traced back as far as the Iliad, when, to take only

one example, Hektor boasts that th e grave of t he Achaean h e kills will ensure

92. Thuc. 7.87.6: Lλγοι π' πολλ.ν "π$ οRκου πεν1στησαν. On the b attles and the polyan-

drion, Thuc. 7.21–25, 36–87; Diod. 13.9–33; P lut. Nik. 21–30; Paus. 1.29.11. The text of Pausanias,

which states that the same monument listed the dead from Euboia, Chios, Asia, and Sicily, has

generated some controversy. See the discus sion in Pritchett 1998: 44–53. For numbers of Athenians

involved, see Thuc. 6.43, 7.16.2, 7.20.

93. IG II

2

5221–22; Xen. Hell. 4.2.13–23, 4.3.15–23, Ages. 2.9–15; Plut. Ages. 18; Diod.

14.83.1–2, 84.1–2; Paus. 1.29.11, 3.9.13; Dem. 20.52–53; Frontin. Str. 2.6.6; Polyain. 2.1.3, 2.1.19.

94. FGrHist 328 FF 49–51; Paus. 1.29. 7. Lewis 2000–2003: 15 suggests the conflict referred to

was instead a fifth-century b attle at Spartolos.

95. Dem. 18–20; Diod. 16.86; Str. 9.2.37; Plut. Alex . 9.2, 12.3, Cam. 19.5, Mor. 259d-e; Paus.

1.25.3 (τ' γ6ρ τ(χημα τ' "ν Χαιρωνεα /πασι το#ς TΕλλησιν 5ρQε κακο), 1.29.13, 7.6.5, 9.10.1,

9.40.10; Polyain. 4.2.2, Just. Epit. 9.3.9–10. On the commemoration of this battle, see Ma 2008.

96. Paus. 1.29.10.

97. Thuc. 1.104. 2, 1.109–10; Diod. 11.77.

98. Xen. Hell. 2.1.20–29.

arrington: Inscribing Defeat

193

the memory of his (Hekto r’s)glory.

99

The grave—and grave marker—of one dead

soldier signals the victory of another. This is also how Lysias describes the tomb

of the Lakedaimonians, near the Dipylon Gate at Athens, working on the Athenian

landscape. He uses the tomb to extol the virtues of the Athenians who perished

fighting the Lakedaimonians in the Piraeus:

But nevertheless not having feared the throng of their opponents, but

having faced the danger with their own bodies, [the Athenians] raised

a trophy over their enemies, and they offer as wi tness of their aret

¯

e the

graves of the Lakedaimonians, near this tomb.

100

Yet if the polyandrion of the Lakedaimonians can testify to the virtue of their

Athenian opponents, acting as pendant to a trophy, then many of the Athenian

polyandria in turn could appear to testify to the skills of their enemies. The

d

¯

emosion s

¯

ema could be seen, through hostile eyes, as a showcase of Athenian

defeat an d a commemoration of foreign success. Isokrates t ells us that, in fact, this

did occur. When describing the fifth-centur y Athenian empire, he writes, “It was a

common occurrence to dig graves every year, which many of our neighbors and

other Greeks visited repeatedly, not to join us in mourning the dead, but to rejoice

at our disasters.”

101

The Athen ians, too, felt the sting of defeat. Po ignant traces

of mourning appear in the epigrams for the war dead, as when they lament the

young who “lost their glorious youth” or “withered away.”

102

Likealover,the

city “longs for ” her men.

103

Casualties could lead to policy changes. Following

defeats at Delion and Amphipolis, the Athenians were no longer so confident in

their streng th, and desi red peace.

104

The topography of military commemoration at Athens may have encouraged

such views, for victories were celebrated away from t he extra-urban cemetery,

within the city itself. Consider, for instance, the year 425 bc, when the Athenians

achieved a remarkable victory over the Spartans at Sphakteria. This event would

not hav e been t he center o f the commemo rative practices in t he d

¯

emosion s

¯

ema,

for Thucydides reports that the Athenian casualties were few in number.

105

The

city center, not the ext ra-urban cemetery, was the place to celebrat e this vi ctory.

99. Hom. Il. 7.89–91.

100. Lys. 2.63: λλ$ Uμως ο% τ' πλ+θος τ.ν "ναντων φοβηθ!ντες, λλ$ "ν το#ς σμασι το#ς

>αυτ.ν κινδυνε(σαντες, τρ1παιον μν τ.ν πολεμων 3στησαν, μρτυρας δ τ+ς α&τ.ν ρετ+ς

"γγς Nντας τοδε το μνματος τος Λακεδαιμονων τφους παρ!χονται. Cf. Lys. 2.2: “ev-

erywhere and among all men those lamenting their own misfortunes sing the praises of these men”

(πανταχ+2 δ κα παρ6 π4σιν νθρποις ο τ6 α&τ.ν πενθοντες κακ6 τ6ς το(των ρετ6ς &μνοσι).

101. Isok. 8.87: πλν Wν 5ν τοτο τ.ν "γκυκλων, ταφ6ς ποιε#ν καθ$ Xκαστον τ'ν "νιαυτ1ν,

ε9ς Yς πολλο κα τ.ν στυγειτ1νων κα τ.ν λλων ZΕλλνων "φοτων, ο% συμπενθσοντες τος

τεθνε.τας λλ6 συνησθησ1μενοι τα#ς \μετ!ραις συμφορα#ς.

102. IG I

3

1162, l. 45: π1λεσαν γλα'ν h!βεν; IG I

3

1179, l. 5: φθK[μενοι].

103. IG I

3

1179, l. 10: νδρας μμ π1λις h!δε ποθε#....

104. Thuc. 5.14. 1.

105. Thuc. 4.38. 5.

classical antiquity Volume 30 /No. 2/October 2011

194

As Aischines says, “The memorials for all our good deeds are set up in the

Agora.”

106

The cap tured Lakedaimonian shields were placed on the Sto a Poikile

and on the bastion of the Temple of Athena Nike.

107

Other dedications, private and

public, r elated to this success may w ell have been made in t he sanctuaries on the

Akropolis. The casualty list for this year, on the other hand, would have been

filled with the dead from a fai led engagement at Eion in Thrace, led by the general

Simonides, where many Athenian soldiers were lost.

108

Visitors to the cemetery

who gazed on these lists would have been r eminded of the defeats o f the years, not

the victories.

In what ways, then, did the lists respond to this ontological difficulty, to

the danger of being seen as signs of Athenian weakness? This questions leads

to an analysis of the how of commemoration: the form of the monuments and

their accompanying imagery; in short, their expressi ve content. And why did th e

Athenians adopt a commemorative system that opened up the possibility that the

lists could be viewed as markers of defeat? Did this connection to defeat serve

any purpose?

FROM DEFEAT, STRENGTH

By commemorating defeat, the casualty lists allowed the Athenians to display

their collective resilience. The repeated rite of commemoration—held every year

in which men died in battle—testified to the ability of the polis to survive and

continue despite setbacks. In formal terms, this sentiment was expressed through

the monumentality of the lists. Despite the fragmentary nature of most of the

lists, it is possible to recover the monumental size of some of them. The shortest

complete list is 1.54 m. high, while the tallest is 2.10 m. with a frieze or 1.68

m. without frieze.

109

Preservedwidthsvaryfromaminimumof0.45m. toa

maximum of 1. 034 m.

110

They are usually about 16–17 cm. thick.

111

The lists

were erected on bases, further increasing their overall size. The base IG I

3

503/4

was 21.5 cm. high, and IG I

3

1163d-f was 20.5 cm. high. If they were placed

on two other steps of similar dimensions, as seems quite likely, then the height

of the whole assemblage (base and list) frequently would have been around 2

m., or well ov er life- size. These impressive heights were matched by impressive

lengths. The base for the Marathon casualty lists at Athens, IG I

3

503/4, was ov er

106. Aisch. 3.187: ^πντων γ6ρ \μ#ν τ.ν καλ.ν 3ργων τ6 &πομνματα "ν τ+2 γορ4 νκειται.

107. Paus. 1.15.4; Lippman, Scahill, and Schultz 2006.

108. Thuc. 4.7.

109. SEG 52.60, SEG 48.83, and IG I

3

1162.

110. IG I

3

1162, 1186.

111. The maximum thickness is 25 cm ., on IG I

3

1168, while the list for the Argive dead from the

battle at Tanagra (IG I

3

1149) is an anomaly with a thickness of 29 cm., perhaps even more (IG

I

3

1149, fragment m: “a sinistra et, ut videtur, a tergo integrum”). On this list, see now Papazarkadas

and Sourlas forthcoming.

arrington: Inscribing Defeat

195

5 m. long. The size of this monument is particularly noteworthy since we know

that, because few died in conflicts that year, such length was unnecessary. Another

base, IG I

3

1163d-f, was a little over 6 m. long. Finally, a poros wall perhaps for

casualty lists, found in rescue excavations at 35 Salaminos Street, once may have

been 10.10 m. long.

112

These lists and groups of lists are not humble stones, but

defiant marks on the landscape that use defeat to signify strength and resilience by

commemorating the event in monumental terms. As A. C. Danto once succinctly

commented, “We erect monuments so that we shall always remember, and build

memorials so that we shall never forget.”

113

Monument suggests triumph, victory,

success; memorial implies loss. According to this semantic distinction, the lists

are more monument than memorial, more triumphant than nostalgic.

The austere casualty lists—carved of hard, glistening marble—stood out in

their sepulchral context. They rose not only above mourners, but above the

majority of the contemporary grave markers, for whet her because of legisl ation

or a change in taste, funerary art in the early fifth century became marked ly

restrained.

114

Grand statues in the r ound disappeared and the number and size

of tumuli dwindled. Private grave markers were often simple slabs of limestone

or slate.

115

In the period of the Peloponnesian War, private commemorations

restarted, and around the same time multiple casualty lists from the same year

physically were joined to one another and began to be decorated with friezes.

116

The new contiguous style of display created a single imposing structure of stone in

place of several smaller ones, thus increasing the sense of monumentality. Friezes

would have added to the stones’ height. Perhaps these changes in form and scale

were designed t o outdo the newly elaborate private monuments.

The stones qua inventories objectified and quantified t he dead, thereby enu-

merating the resources that the community had lost—but this also showcased the

rich resources that had been available for spending.

117

Moreover, such an inven-

112. Stoupa 1997: 53.

113. Danto 1985: 152.

114. On the legislation, s ee Cic. Leg. 2.26.64–65; Clairmont 1970: 11–12; Stupperich 1977:

71–86; Clairmont 1983: 249–50n.13; Humphreys 1993: 88–89; Morris 1992–1993: 35–38, 1994:

76, 89n.43; Stears 2000: 42–54; Hildebrandt 2006: 77–84.

115. Kurtz and Boardman 1971: 121–27. Some private stelai were as tall as the state stelai (see

idem, 124), but these must have been exceptions to the rule.

116. Anathyrosis, indicating contiguous stelai, is visible on IG I

3

1150, 1163, 1175, 1177, 1180,

1186, 1189–92; vertical lines or channels are visible on IG I

3

1147, 1147 bis, 1157, 1163, 1175,

1177, 1180, 1189, SEG 52.60.

117. I thank Athena Kirk for drawing my attention to the importance of comparing the lists as

records of resources with the Athenian practice of inscribing public inventories. Brooke Holmes

also has pointed out to me the frequent pairing of σματα (bodies) and χρματα (goods, money) in

Thucydides (e.g., 6.12.1). On the symbolic aspects of epigraphy, see Thomas 1989: 45–68; Thomas

1992: 84–88; Steiner 1994, 64–71; Sickinger 1999: 65; Bodel 2001: 19–30; and Davies 2003:

335–37. The latter discusses the casualty lists. Low 2010: 344 also draws attention to the casualty

lists qua lists, which she argues frequently had honorific functions. On the importance of the location

of inscriptions, see, e.g., Bresson 2005: 163–66 (on sanctuaries) and Shear 2007 (on the Agora).

classical antiquity Volume 30 /No. 2/October 2011

196

tory suggested to the viewer that more resources were available. This rhetoric

of power was heightened through the inclusion of geographical rubrics, which

expressed the extent of Athenian arch

¯

e. Consider, for instance, IG I

3

1147, a

nearly complete list for the tribe of Erechtheis, lacking only the base and molding

(Figure 1). The sides are smooth, so we must envision nine more free-standing

stelai, on e for each t ribe. Each stele, li ke IG I

3

1147, would have born a tribal

heading followed by the brief assertion, “These died in the war.” There follows

a list of the locations of action: Cyprus, Egypt, Phoenicia, Halieis, Aigina, and

Megara. Repeated on each stele, this h eading conveyed a sense of Athenian might.

The casualty lists were in some ways pendants to the Athenian Tribute Lists. The

latter recorded the (tithes from the) financial t ribute from foreign areas to Athens,

while the former recorded Athenian expenditures in foreign areas. Both were

products of empire.

The relationship between the lists and military calamities also could be

exploited to shame Athenians. While the sacrifice of the dead, as discussed

above, could shame individuals who had survived the conflict and could mak e

others, such as those too young to serve, aware of the potential for future

shame, a past military defeat could shame the community into action. This

is how Lysias describes the effect of the disaster at Aigospotamoi upon the

collective of democrats from Piraeus who faced the Lakedaimonians. These

Athenians were “no less ashamed by their disasters than enraged at their

enemy.”

118

Following defeats the military men—Athenians and metics—were

compelled to d isplay th eir valor and thereby pro ve that their earlier def eat was

not due to character but to fortu ne or (less frequently subject to b lame) poor

leadership.

119

By risking sacrifice—being willing to occupy a space on a list—

they erased the coll ective shame of past def eat. As we saw with the way the

lists commemor ated individual death, the way they marked col lective defeat

also created an ag gressive rhet oric that capitalized on the Athenian sense of

shame.

But defeat on the lists also could be el ided. This process is par ticularly

evident on the fri ezes that accompany the lists, which show neither the defeat nor

the victory of either side. Unfortunately the public reliefs are few in number. Only

three figured friezes have been identified securely,

120

accompanying: ( 1) the list of

118. Lys. 2.62: ο%χ _ττον τα#ς συμφορα#ς α9σχυν1μενοι ? το#ς "χθρο#ς Lργιζ1μενοι.

119. On the excuses made for defeat, see Roisman 2005: 68–70; Le´vy 1976; Wolpert 2002:

120–22. Lys. 2.74 also mentions that defeats could be consolations for the parents of the dead who

fell in earlier conflicts. The city, they must have reasoned, would not have lost had their sons been

alive to help.

120. I do not include in this discussion the anthemion relief on IG II

2

5222, for it is not figural.

There are two other candidates for public reliefs: one in New York (N ew York , Metropolitan Museum

of Ar t 29.47; Clairmont 1983: 214–15; Ho¨lscher 1973: 107–108, 263n.556; Stupperich 1977: 19;

Ridgway 1983: 201–202; Ridgway 1997: 199–200, 224–25nn.24–25; Scha¨fer 1997: 162, no. 2;

arrington: Inscribing Defeat

197

cavalry casualties found in rescue excavations near the Larissa train station, here

called the Palaiologou relief;

121

(2) a fragmentary inscription in Oxford (Figure

3);

122

and (3) a list with the dead from engagements at Corinth and Boiotia, in the

Corinthian War (Fi gure 4).

123

The latter is secur ely dated to 394/3 and preserves

the names of six Athenian tribes along with fragments of some names. The stone

is broken at the left, where the other four tribes would have been. There is no

doubt that this is a casualty list. Underneath the Oxford relief are the remains

of the nu and alpha probably of

ΑΘΕΝΑΙΟΝ, from a heading, ’Αθηναων οeδε

π!θανον "ν

....

124

Stupperich dates this relief stylistically to the second half

of the fifth century.

125

The Palaiologou stele i s more unconventional since it lists

cavalry and one mounted archer and was found near the Larissa train station, away

from the core of the d

¯

emosion s

¯

ema. This proximity to Hippios Kolonos is not

particularly surprising, though, when one considers the historic importance of this

place for cavalry.

126

Moreover, the organization of the list by tribes and the use of

epigrams and geographical rubrics echoes standard casualty lists and suggests that

the frieze also echoes the typology and iconography of public friezes, whether the

Palaiologou stele was erected at public expense or not. The stele has two lists

of dead. The top one, often interpreted as the later one, is in the Ionic alphabet and

lists the dead f rom an engagement which is assumed to have taken place at Megara

since th e accompanying epi gram mentions the walls of Alkat hoo¨s. Four of the

names on this top list were inscribed after the others. The bottom list is headed by

an epigram that mentions the dead from battles at Tanagra and Spartolos. Tanagra

could refer to engagements there in 426 or 424/3 (the Battle at Delion), Spartolos

Goette 2009: 190–91) and one recently found in secondary use at Aigina (Goette 2009: 202–204,

with fig. 5) . Neither has an accompanying inscription that can secure its identity. On the New York

relief, two non-Athenians—with long hair and piloi, one with an animal skin—are being killed or

fleeing. There is a third body on the ground, naked apart from a chlamys; might he be an Athenian?

In any event, the attempt through garb and landscape to represent a specific engagement suggests that

this may be a votive relief (cf. a votive relief for Pythodoros, Eleusis Museum 51; Ho¨lscher 1973:

99–100; Langenfaß-Vuduroglu 1974: 34, no. 57; Ridgway 1983: 201; Bugh 1988: 91–93; Goette

2009: 198–99; Lawton 2009: 70). The Aigina piece is a thin fragmentary relief of a foot soldier

in trousers moving toward the right and a horse to his left moving toward the left. The fragmentary

nature of the piece, lack of inscription, and unusual clothing make it impossible to identify whether

or not the relief once belonged with a casualty list.

121. Athens, Third Ephoreia M 4551; SEG 48.83; Parlama 1992–1998: 536; Touchais 1998: 726;

Parlama and Stampolidis 2000: 396–99, no. 452; Arrington 2010b: 521. Unfortunately permission to

reproduce the photograph that appears in Parlama and Stampolidis 2000 was not granted.

122. Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, Michaelis no. 85; Stupperich 1978; Clairmont 1983: 202–203;

Stupperich 1994: 94; Scha¨fer 1997: 162, no. 3; and Goette 2009: 189–90.

123. Athens, National Museum 2744; IG II

2

5221; Brueckner 1910: 219–34; Wenz 1913: 58–61;

Stupperich 1977: 17–18; Clairmont 1983: 209–12; Stupperich 1994: 94; Ho¨lscher 1973: 105–107,

263n.543; Langenfaß-Vuduroglu 1974: 11, no. 13; Scha¨fer 1997: 162–63, no. 4; Scha¨fer 2002: 268,

no. GR 8; Hurwit 2007: 36–37; Goette 2009: 191–92; Arrington 2010b: 521.

124. Stupperich 1978: 91.

125. Stupperich 1978: 90.

126. On the connection of this area with the elite, see A rrington 2010b: 529–32.

classical antiquity Volume 30 /No. 2/October 2011

198

to a battle in 429, or one or the other could be events that Thucydides does not

mention.

127

Megara was invaded twice a year between 431 and 424.

128

These public reliefs shun the language of victory and present undecided

contest. On the public Palaiologou relief, two Athenian horsemen, moving toward

the left, combat two foot soldiers. Though one non-Athenian has fallen, all is not

lost. From the left boldly strides his comrade, whose presence is highlighted by

his long, wide chlamys, which would have been brightly painted. With his front

foot braced on a rock, rear leg strai ght and strong, chlamys streaming behind

him, he lunges toward the Athenian horseman. Nothing about this non-Athenian

suggests weakness. Without the accompany ing inscription and without t he pilos

attribute, we may have surmised that the standing footman was the Athenian,

his nudity emphasizing his athletic prowess and assimilating him to an Athenian

ideal of manliness.

129

The cape anchors him to the ground and contributes to

his appearance of solidity, as his hand meets the horse’s hoof and checks its

advance. His weapon, and that of his comrade, were added in metal, whil e the

Athenian’s spear was only painted. Metal confronts pigment; odds favor the non-

Athenian. Moreover, the terrain is visibly rocky, which the non-Athenian uses to

his advantage to brace himself, but which rendered the footing difficu lt for the

Athenian horses.

The relief in Oxford is more fragmentary, but traces o f the u ndecided con test

are still visible (Fig. 3). An Athenian foot soldier lunges from the right toward

a naked soldier on the ground, but is countered by the shield of an opponent who

must have stood over the naked soldier, defending him.

130

More rich in narrative content, though still fragmentary, is the public relief

from the Corinthian war (Fig. 4). Two Athenians—one on horseback, one on

foot—surround a fallen opponent. The opponent is naked except for a round

shield. He is not a coward tossing his shield to hasten his retreat, but clings to

it tenaciously. The horse clubs the fallen soldier in the chin, while the Athenian at

the left savagely for ces h is knee into the enemy’s back. Several decades l ater

than the Palaiologou relief, this scene comes closer to expressing victory and is

notably vi olent. But commentators often miss one import ant detail: the Ath enian

horseman lowers his spear. The point does not drive into the enemy, but descends,

impotent, to the other side of the horse. The Athenian foot soldier at the left does

not dispatch the opponent, but takes him prisoner.

131

None of these public reliefs illustrates the defeat of the Athenians. This

absence, perhaps, is to be expected. But none portrays a clear Athenian victory.

Both poles of victory and defeat are elided in order instead t o thematize struggle

127. See the discussion in Badian apud Moreno 2007: 100–101n.114; Matthaiou 2009: 203–204;

Matthaiou 2010: 14–16; Papazarkadas 2009: 69–70.

128. Thuc. 2.31. 3, 4.66.1.

129. On athletic and military nudity, see Hallett 2005: 17.

130. Stupperich 1978: 89.

131. Ho¨lscher 1973: 105.

arrington: Inscribing Defeat

199

and undecided contest. The most appropriate label to apply to these scenes is

ag

¯

on, which is Thucydides’ word of choice for describing war and appears in

the epigram for the war dead IG I

3

1163d-f: “Wretched ones, when you saw

through such a contest (ag

¯

on) of unexpected battle/ you lost your lives in war

by divine agency.”

132

Just as Lysias emp hasized the word danger (kindynos)in

his funeral oration, the public reliefs vividl y portray the risks of war. They explain

and normalize the death of the Athenians—their individual defeats—for even the

most skilled may lose their lives in such confrontations, and in fact the bravest are

likeliest to die. Moreover, by depicting the dangers of war, the reliefs illustrate to

the onlooker the need for continued sacrifice. The ongoing nature of the struggle

on the reliefs matches the verbal aspect of the participle “fighting” (marnamenoi)

used on the epigrams to describe how the casualties died. The absence of an

outcome further underscores that the action takes pl ace in the present tense: risks

are real, enemies are present, sacrifice is (still) necessary. Perhaps it is not a

coincidence that figural decoration on the lists seems to have begun during the

Archidamian War, when battles increasingly were fought close to home. There

was a need for sacrifice not just from the hoplite, but from all the inhabitants of

Attica who had to stand by and watch as their lands were ravaged.

Although the epigrams on the stelai extol the virtue of the dead, like the

reliefs they avoid overt references to triumph or conquest.

133

On the Marat hon

casualty list from Eva Loukou, for i nstance—when we know the Athenians won

a resounding victory—the success of th e venture is only alluded to through the

words, “they crowned the Athenians.” Their victory is not so much eulogized as

transferred to the surviving polis. In the remainder of the epigram, the process

of defeating the enemy is not described; rather, the danger and t he risk of the

venture are presented: they were t he few facing the many.

134

The iconography of private reliefs reveals just how calculated and uni que the

visual discourse of the public reliefs was. Indeed, although scholars frequently

point to the similarity between public and private reliefs,

135

the differences bet ween

them are striking. While the public reliefs are short friezes that crown long lists

of text, the private reliefs often present large images with only some text. Even

more telling are the different modes of portraying conflict. The private grave

relief for the rider Dexileos, erected in 394/3, unlike the casualty list reliefs,

illustrates complete conquest (Figure 5).

136

The Athenian dead is portrayed in the

guise of a living, victorious, knight, at the moment when he destroys a helpless

132. τλ!μονες hο#ον γAνα μχες τελ!σαντες !λπ[το] φσυχ6ς δαιμονος Lλ!σατ$ "μ πολ!μοι.

(ll. 34–35).

133. The one possible exception is IG I

3

1179, l. 5: νκεν. The end of the preceding line is lost so

the significance of the word her e remains unclear.

134. [π]αυρ1τεροι πολλAν δεχσμενοι π1λεμον (l. 5).

135. E.g. Stupperich 1977: 20; Goette 2009: 196; Neer 2010: 183–97; Osborne 2010: 263.

136. Athens, Kerameikos P 1130; Wenz 1913: 78–81; Ho¨lscher 1973: 102, 262n.527; Langenfaß-

Vuduroglu 1974: 11–12, no. 14; Clairmont 1983: 68, 213; Clairmont 1993: 2.209; Ridgway 1997:

classical antiquity Volume 30 /No. 2/October 2011

200

opponent. Although the relief does not represent an exact historical moment, it

does correspond to a precise time in battle: the rout, when the cavalry chases

down the fleei ng fo e, disp atching t hem wit h spears.

137

In this relief, in contrast to

the schema on the Palaiologou relief, the Athenian horse’s hooves unnaturally

encompass the foe: right rear leg, at a sharp angle, over the foe’s slightly bent

right; right front leg concealing the foe’s elbow and compressing his head, visually

pulling it in—note the opponent’s straining neck muscles—and preventing any

defensive use of the sword (once added i n bronze). The front right hoof together

with the opponent’s shield create a constraining frame, making the opponent

appear trapped. The posture of the foe heightens this sense of constraint: his

left arm is cramped, an impression highlighted by the tightly bunched garment

on his left forearm. His left leg is foreshortened and the knee emerges from

the composition: this man has no control. Lines on the abdomen indicate that

he folds down to his left, forced to offer his right flank to Dexileos’ spear. His

hand slips out of the shield grip (note in particular the lifted left pinky), strength

ebbs out of his right leg which appears pressed down by Dexileos’ right foot,

and Dexileos’ scabbard runs behind, seemingly through, his opponent’s body, a

visual play emphasized by t he placement of the parallel lines defining the fallen’s

pectoral muscles and upper abdominal fol d. Some scholars have argued that here

we witness a beautiful death,

138

but this instead is the portrayal of a violent,