New denition

of default

What banks need to do by

the end of 2020

Minds made for transforming

nancial services

Contents

Executive summary

Regulatory overview

Key challenges and considerations

What banks should do now

Publications

New DoD on a page

Key contacts and

country representatives

02

03

10

13

14

16

21

Following the nancial crisis,

the European Banking Authority

(EBA) has established tighter

standards around the denition

of default (CRR Article 178)

to achieve greater alignment

across banks and jurisdictions.

These need to be implemented

by the end of 2020.

1New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020 |

Executive summary

European regulators have adopted new

detailed standards on how banks need to

recognize credit defaults for prudential

purposes to increase consistency across

countries and banks. The deadline for

compliance is the end of 2020.

Banks that have carried out a

quantitative impact analysis have found

that the new standards can materially

impact the number and timing of

defaults, calling into question the validity

of existing models and processes. The

impact varies signicantly across banks

(depending on approach for estimating

regulatory capital and pre-existing

default denition) as well as across

individual portfolios within the banks.

But where the impact is material it

needs to be reected in updated risk

management and supporting decisions

(e.g., pricing), accounting (e.g., IFRS9,

Effective Interest Rate) and capital

models (IRB and ICAAP).

The guidelines are extensive and

detailed, challenging legacy IT

infrastructure and processes that have

often evolved organically over the years.

For some banks this is an opportunity

to cleanse historical data, refresh and

modernize supporting infrastructure,

and establish the foundation of a more

sustainable data strategy to support

advanced analytics. New processes and

controls also need to be established.

But time is short and the changes,

considered material for all capital

models, require substantial efforts

from both banks and regulators alike.

IRB banks subject to ECB supervision

have already had to submit detailed

impact assessments and implementation

plans as part of the model re-approval

process. All IRB models also need to be

updated to reect additional changes

introduced by the EBA as part of the ‘IRB

repair work’, by the end of 2021. But

progress across the industry is far from

uniform and some national regulators

have been less engaged with the banks

they supervise.

Furthermore, these changes are only

a few among a series of ongoing

challenges, such as rening IFRS9

implementation, meeting ongoing

demands to improve stress testing

capability and implementing Basel III

reforms. This leaves banks, and

supervisors, with a lot to do and little

time to do it.

In this paper we provide a summary

of the new regulation, and highlight

points for consideration based on the

challenges banks have faced so far in

their implementation efforts. At the end

of this paper we also reference a list of

relevant publications and a “New DoD on

a page” summary of the new denition

of default (DoD) standards.

2

| New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020

Regulatory overview

What is the new DoD and what does

it mean?

• A new set of standards that are more detailed

and prescriptive, and will have signicant impact

on governance, data, processes, systems and

credit models.

• The impact on capital requirements depends

on several inuencing factors, including type of

approach for estimating capital requirements (IRB or

Standardised Approach), current implemented default

denition and portfolio specics.

• For approved IRB capital models, the new standards

are deemed to be a material change and hence

requiring formal re-approval of a Competent

Authority, irrespective of capital impact.

• All banks need to implement the new standard

by 31 December 2020 for reporting to start

1 January 2021.

What are other relevant publications

to consider?

• New requirements for internal models that must be

developed and implemented by the end of 2021, e.g.,

EBA guidelines for estimating Probability of Default

(PD) and Loss Given Default (LGD); ‘IRB Repair’.

• The broader regulatory reform agenda, specically

Basel III nalization and forthcoming regulation

(CRR2/CRR3), as it impacts the model landscape and

capital beyond 2021.

• Regulations on the denition and/or management

of forborne and non-performing exposures, notably

guidelines from the EBA and the Basel Committee on

Banking Supervision (BCBS).

• The EBA, ECB and NCAs have also published

additional guidance and impact assessments related

to the new DoD.

• See Publications at the end of this paper for an

extended list of references to relevant publications.

Who does it impact?

• All rms subject to the Capital Requirements

Regulation (CRR) and holding capital against

credit activities.

• IRB banks need to recalibrate their credit models but

banks under the Standardised Approach (SA) also

need to identify, use and report defaults according to

the new DoD.

What are the new guidelines?

• European Banking Authority (EBA) guidelines on the

application of the denition of default.

• European Commission (EC) regulation on the

materiality threshold for credit obligations past due.

• National Competent Authorities (NCAs) and ECB have

published their own consultation papers and policies

where the regulation provides national discretion

(materiality thresholds and 180 days past due).

3New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020 |

Summary of the new rules

Materiality thresholds

Introduction of new absolute and

relative materiality thresholds for the

purposes of DPD counting; when both

thresholds have been breached for

90 days, a default has occurred. ECB

and most NCAs have adopted the EBA

RTS thresholds:

• Retail: 1% relative and €100 absolute

• Non-retail: 1% relative and €500

absolute

The notable exception to this being the

PRA in the UK which has adopted a 0%

relative and a zero absolute threshold

for retail exposures to minimize the

operational impact that changing the

widespread practice of determining

90 DPD through a ‘months-in-arrears’

approach would imply. It should be

noted that NCAs outside the Eurozone

have adopted absolute thresholds in

local currency; these have so far been

specied in even amounts broadly

equivalent to €100 and €500. Where

banks apply default at obligor level, they

should ensure materiality thresholds

are also applied at obligor level. Banks

may opt to use lower thresholds

as an additional unlikeliness to pay

trigger (see below).

Past due amount and DPD

counting

The amount past due shall be the sum of

all amounts past due, including all fees,

interest and principal. For the relative

threshold, this amount should be divided

by the total on-balance exposure. In case

the principal is not repaid or renanced

when an interest-only loan expires, DPD

counting should start from that date even

if the obligor continues to pay interest.

There are also specic requirements

for when DPD counting may be

stopped — when the credit arrangement

specically allows the obligor to change

the schedule, when there are legal

grounds for suspended repayment, in

case of formal legal disputes over the

repayment or when the obligor changes

due to a merger or similar event.

Technical default

The standards specify a strict and

limited set of so called technical defaults,

i.e. false positives that are caused by

technical issues; generally data or

system errors, or failures or delays in

recognizing payment.

Removal of 180 DPD

Following the EBA recommendation

to remove the CRR option to use 180

DPD instead of 90 DPD (as applicable

under the rules for residential and SME

commercial real estate and/or exposures

to public sector entities), ECB has

removed this option for Systemically

Important Institutions (SIIs) in the Single

Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and all

NCAs that have previously exercised

the CRR option to allow 180 DPD have

followed suit.

Factoring and purchased

receivables

Specic requirements for factoring and

purchased receivables; where a factor

does not recognize the receivables on

its balance sheet, DPD counting should

start when the client account is in

debit, otherwise DPD counting should

start from when a single receivable

becomes due.

01

Days past

due (DPD)

4

| New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020

Non-accrued status

UTP will be triggered if the credit

obligation is put on non-accrued

status under the applicable accounting

framework.

Specic Credit Risk

Adjustment (SCRA)

Added guidelines on cases where SCRAs

trigger UTP.

Sale of the credit obligation

The sale of a credit obligation needs to

be assessed and classied as defaulted if

the economic loss exceeds 5%.

Distressed restructuring

Concessions extended to obligors with

current or expected difculties to meet

their nancial obligations should be

considered distressed restructurings.

These need to be assessed to establish

materiality; if the net present value

(NPV) of the obligation decreases by

more than 1% (or a lower threshold set

by the institution), the obligation should

be considered defaulted.

Bankruptcy

Clarication on arrangements to be

treated similar to bankruptcy, including

but not limited to all arrangements in

annex A of Regulation (EU) 2015/848

on insolvency proceedings. This includes

not only such arrangements directly

involving the institution but also such

arrangements the debtor has with

third parties.

Additional indications of

unlikeliness to pay

Banks must dene additional UTP

indicators.

The standards specify additional UTP

indications that must be included,

e.g., fraud. The standards also provide

guidance on optional UTP indications to

be considered, e.g., signicant increase

in obligor leverage, signicant delays in

payment to other creditors, etc.

Furthermore, they specify situations

when these and other UTP triggers

should be evaluated, e.g., in the

event the obligor changes the

repayment schedule within the rights

of the contract.

Probation periods

Minimum regulatory probation period

of 3 months for all defaults with the

exception of distressed restructuring,

where a 1 year minimum probation

period applies.

Banks have to monitor the behavior

and nancial situation of the obligor

in probation to support cure after the

probation period expires. There is an

option for banks to apply different

probation periods to different types of

exposures (as long as they meet the

minimum requirement). In case the

defaulted exposure is sold, the bank

needs to ensure the probation period

requirements are applied to any new

exposure to the same obligor.

Monitoring the effectiveness of

the policy

Banks are required to monitor the

appropriateness of their curing policy on

a regular basis, including impact on cure

rates and impact on multiple defaults.

02

03

Unlikeliness

to pay (UTP)

Return to

non-default

status

5New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020 |

External data

When external data is used for the

estimation of risk parameters, the

institution must document the DoD

used in these external data, identify

differences to the institution’s internal

denition, and perform required

adjustments in the external data for any

differences identied, or demonstrate

that such differences are immaterial.

Consistency in the application

of default

Banks must ensure that the default

of an obligor is identied consistently

across IT systems, legal entities within

the group, and geographical locations. If

this is prohibited due to legal limitations

on information sharing, competent

authorities must be notied. Additionally,

for banks using the IRB approach,

they need to assess the materiality

of impact on risk estimates. Where

the development of this capability is

burdensome, banks will be exempt if they

can demonstrate immateriality due to few

shared obligors with limited exposures.

Furthermore, the internal denition of

default must be applied consistently

across legal entities within the group and

across types of exposures, unless the

bank can justify differences on the basis

of different internal risk management

practices or different legal requirements.

Such differences must be clearly

specied and documented.

Level of DoD application and

contagion

The standards provide guidance on DoD

application at facility and/or obligor level

for retail exposures.

Generally, when a credit obligation

defaults which is related to an exposure

where default applies at obligor level, all

other exposures of the obligor should

also default, including those where the

institution applies default at facility level.

When a credit obligation defaults which

is related to an exposure where default

applies at facility level, the institution

should only consider other exposures of

the obligor in default for certain UTPs.

Timeliness of default

identication

Institutions should have automated

processes, where possible, that identify

defaults on a daily basis. Where this

is not possible, manual processes

must be performed frequently

enough to ensure timely identication

of defaults. Delays in recording

defaults must not lead to errors or

inconsistencies in risk management,

risk and capital calculations or internal/

external reporting.

Documentation

Banks must document all their internal

DoDs in use, including associated scope,

and triggers for default and cure. They

also need to keep an updated register

of all historic versions of DoDs used.

Furthermore, banks must document

how the default and cure logic is

operationalized in detail, including

governance, processes, and information

sources for each trigger.

Internal governance

requirements for IRB banks

Additional governance requirements

are introduced for banks using the IRB

approach, e.g., the requirement that

Internal Audit should regularly review

the robustness and effectiveness of the

process of identifying defaults.

04

Other key

changes

6

| New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020

7New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020 |

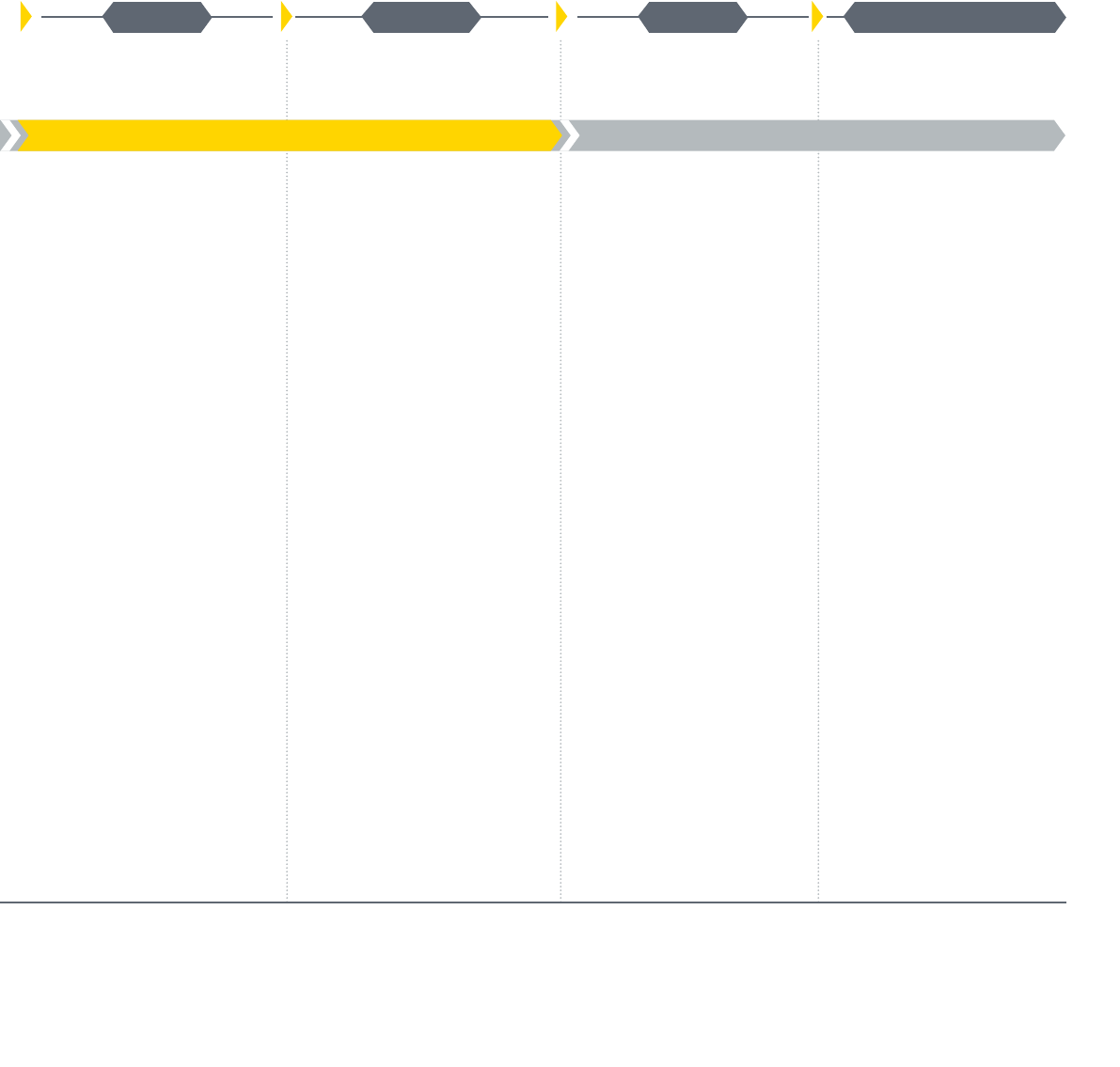

Timeline

EBA publishes

guidance on new DoD

• End of 2015, EBA starts

gathering data for a

quantitative impact study

(QIS) on the new DoD.

• In September 2016, EBA

publishes a report with the

QIS results.

• Together with the QIS

report, EBA publishes

the nalized GL on the

application of the denition

of default and nal draft

RTS on the materiality

threshold for credit

obligations past due.

Start of TRIM

• Beginning of 2017, ECB

starts on-site Targeted

Review of Internal Models

(TRIM) inspections, the

objective of which is to

reduce inconsistencies and

unwarranted RWA variability

between IRB banks.

• BCBS publishes Basel III: post-

crisis reform.

• In November 2017, the

European Commission adopts

regulation on RTS for the

materiality threshold for credit

obligations past due.

• End of 2017, EBA advises

the European Commission to

disallow the application of 180

day past due.

Application step 1 for

banks in the SSM

• In June 2018, ECB contacts

banks in the SSM with

guidance on the process for

implementing the new DoD,

proposing a two-step approach.

• SSM banks prepare their DoD

application package (including

an impact assessment) for step

1, which they have to deliver

by year end under the Two-

Step Approach.

• NCAs publish consultation

papers and policies relating

to EBA’s GL, RTS and Opinion

relating to the new DoD.

• End of 2018, ECB publishes

regulation on materiality

thresholds.

2016 2017 2018

EBA DoD

Publication

SSM 1st step

application deadline

8

| New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020

Feedback from ECB

• Early 2019, SSM banks

receive feedback from

ECB on their submitted

application package. A

number of SSM banks are

requested to modify parts

of their self assessment.

• Halfway through 2019,

ECB delivers feedback

on the permission to use

the Two-Step Approach

to SSM banks that have

applied for this. Negative

feedback may result

in exemption from the

Two-Step Approach.

• If SSM banks have received

permission, they will focus

on default denition go-live

(step 1), leaving enough

time to collect one year of

default data under the new

default regime.

New DoD standards

operationalized

• Adjustments to systems

and processes to take into

account the new DoD should

be implemented and taken

into production.

• Banks build up data

history based on the new

DoD to support model

redevelopment.

• Some national regulators

may propose different

timelines for model updates,

e.g., in the UK the PRA latest

consultation has proposed

that residential mortgage

models should be updated

and implemented by the

end of 2020, with other IRB

models due by end of 2021.

This is taking advantage of

the exibility afforded under

the IRB framework under

article 146.

Models updated for

new DoD and IRB

repair changes

• Material models updated

to reect new DoD and

‘IRB repair’ standards by

end of 2021, to go live

from 1 January 2022.

• Models that are no

longer eligible for IRB

under revised Basel III

framework can be

de-prioritized to end

of 2023, or banks can

apply for permanent

partial use.

• Where models have not

been redeveloped or

approved, scalars/capital

buffers may apply.

Basel III go-live

• The revised Standardised

Approach for credit risk

and revised IRB framework

should be implemented as

of 1 January 2022 (Basel

framework timelines).

• The output oor starts at

50% and will increase to

72.5% in 2027.

• Adjustments of business

models to the new

regulatory regime.

2022 and beyond

New DoD basis of reporting

from 1 January 2021

2019 2020 2021

Time until DoD go-live

9New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020 |

Key challenges and

considerations

Jurisdictional alignment

NCA discretions on materiality

thresholds could lead to complexities

for banking groups with cross border

entities in the EU. At this time, we

expect jurisdictional differences to be

limited — the main difference currently

arising in the UK, where PRA has set

zero thresholds for retail exposures to

accommodate the ‘months-in-arrears’

approach to determine 90 DPD defaults.

Similar challenges arise for global banks

that need to decide whether to extend

any changes to current practices in their

EU entities to entities outside of the EU

(including e.g., how to handle materiality

thresholds for portfolios denominated in

different currencies).

Impact assessment

A quantitative impact assessment is an

important step in understanding the

broad implications of the new standards

on the capital position, individual

businesses and associated models. As

such it also informs:

• Policy decisions where some

exibility and choices exist: this

includes adopting lower DPD

materiality thresholds, contagion of

facility level retail exposure defaults

(‘pulling effect’) and other additional

indications of UTP triggers as well as

different probation periods.

• Scalars to ensure capital estimates

reect the new standard for models

that are not redeveloped and

approved by 2021.

• Priorities for model updates.

Banks ideally have the historical data

to assess impacts on level, timing and

duration of defaults, with associated

impacts on cures. Where historical data

is not sufciently rich, banks have to

adopt a range of approaches to support

the analysis, ranging from historical data

cleansing and recasting, to simulation

based approaches or qualitative

assessments. Where the impact cannot

be estimated with a high level of

condence, focus is on accelerating

process updates to collect default data

on the new standards.

Where banks use external data, which is

common for wholesale models, they will

need to demonstrate its consistency with

updated internal standards.

Knock-on impact on the

broader model universe

In the run-up to 2022, a number of

additional regulatory changes (‘IRB

repair’) are being implemented to

capital models together with the new

denition of default standards. These

cover requirements around margins

of conservatism, realized losses, long

run average or hybrid calibration, and

downturn calibration for LGD and EAD.

Regulators are expecting all these

changes to be incorporated in banks’ IRB

remediation programs.

Changes to the denition of default

also impact the broader model stack

across risk, nance and treasury

analytics (e.g., IFRS9, Fund Transfer

Pricing, stress testing), raising important

planning and prioritization challenges

to banks. It also stretches resources

10

| New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020

that are already facing substantial

demands from increased model risk

management standards, IFRS9 day 2

activities, CECL implementation (for

some), while progressing with AI and

machine learning strategies, among

other changes. This is prompting some

banks to reconsider the broader model

universe and how it can be simplied,

componentized, and delivered through

more exible technology infrastructure.

Data

The typical approach banks adopt for

data is to recast historical data at least

for a few dates, and to implement the

new standards as quickly as possible

to support collection on the new basis

as a cross check. However, recasting

historical data requires it to be rich and

reliable — for instance on UTP triggers,

forbearance or technical defaults.

Procedural changes over the years can

also lead to signicant difculties in

evaluating historical data according to

the new criteria. While in some cases

reasonable assumptions can be made

to derive good enough proxies to

support the development of scalars or

recalibrated models, this is by no means

a given.

Banks supervised by ECB have typically

started or are about to start data

collection. Banks that have not yet

started might nd that their systems

require substantial updates before they

can collect data and that necessary

resources are already committed on

work that cannot be easily re-prioritized.

Operational changes

Operationalization of the new DoD

typically requires changes to existing

systems and processes.

Examples of typical areas of operational

challenge include:

• DPD counters are not systematically

automated and operate on different

denitions, and treatment of

technical defaults doesn’t have the

necessary rst line controls.

• UTP indicators can currently be

dened broadly and allow a large

degree of personal judgement. The

new standards introduce stricter

UTPs (e.g., specic denition of sale

at a material loss) and will require

stricter controls.

• Return to non-default status requires

the implementation of new cure logic

and controls against various tests for

return to performing.

Business processes typically need to be

changed to support better alignment

and ownership throughout the default

lifecycle, and associated data capture

and audit trail.

Depending on existing processes and

supporting technology, some banks

will nd that these changes can require

signicant time to implement and brand

new solutions to be established, e.g., the

introduction of new workows.

Governance and

documentation

The new standards, in line with trends

over the recent years, require a much

greater level of documentation of

processes and procedures. As well

as robust governance and audit trail,

including a register of all current and

historical default denitions used.

Many banks have found that this is

substantially more than had currently

been in place, and are considering the

adoption of an end-to-end workow

process to provide both robust controls

(including audit trail) and structured data

collection. So banks should consider

in their timeline the time it takes to

build a clear picture of the current

end-to-end process and associated

roles and responsibilities in managing

non-performing exposures throughout

the lifecycle, and technology options

to bring a common workow and data

capture around it.

Finally, the new standards add to

the already extensive expectations

regulators have of the audit function,

who are expected to carry out a regular

review of the bank’s approach to the

new standards.

Capital impact

From a capital planning standpoint,

banks need to consider the potential size

of impacts; these could be signicant for

specic portfolios, particularly for banks

on Foundation IRB, and for portfolios

that will move to F-IRB when the

nalised Basel III reforms go live, as well

as for banks with large gaps to the new

DoD, such as having to shift from a 180

days past due standard to 90 days.

Based on a sample of impact

assessments we have generally observed

11New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020 |

an increase in PDs, mainly due to new

materiality thresholds, which is offset

by a decrease in LGDs from higher

cure rates.

Impacts at individual portfolio level

can also be much more material — it

is not uncommon to observe RWA

impacts in the order of -25% to +25% on

individual portfolios.

The stricter requirements for returning

defaulted exposures to non-default

status is also likely to lead to an increase

in default stocks in the medium term,

with associated impacts on RWA and

impairments.

Business practices

Business stakeholders have a key

role in the program to review the

impact of the new requirements on

customers and/or nancial performance,

and make changes to business

practices accordingly.

From an economic standpoint, the

impacts on capital can vary greatly

from bank to bank and across different

portfolios. A material capital (and/

or IFRS9 impairment) change may

warrant a review of current processes

that are designed to prevent and

recover defaults, or pricing or lending

criteria. This can particularly be the

case in higher risk portfolios where cure

criteria may lead to punitive capital

charges having to be held longer than

is currently the case. Another example

would be the selling of credit obligations,

which, if they trigger default, will be

reected in higher risk estimates than

might currently be the case.

More generally, banks will need to

consider how the new standards

need to be reected in the end to end

‘customer journeys’.

Timeline and implementation

approach

The current end of 2020 timeline looks

challenging for many banks. Updating

internal systems and processes to be

able to collect data on the new DoD

basis and allow some parallel run prior

to reporting ‘go-live’ is a priority. For

banks that are looking to establish the

foundation of a more sustainable data

strategy (e.g., to support advanced

analytics), this might require a phased

implementation.

From a modelling standpoint, the

volume of work is potentially vast. So

close engagement with supervisors and

regulators, and a structured approach

based on a robust impact assessment

and prioritizing redevelopment

for most material and/or impacted

portfolios is key.

12

| New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020

Banks are at different stages in their programs — in our experience, SIIs are mostly ahead of the curve,

followed by IRB banks, ahead of SA banks. This follows naturally from the complexity of change and level

of necessary supervisory involvement, but the fact is that the timetable looks challenging for all banks and

the risk for technical debt and RWA inefciencies after 2020 is signicant.

Banks need to progress quickly with their DoD implementation efforts. Key steps include:

What banks should do now

Program

governance

Establish programme governance to provide coordination across policy

decisions, approaches, external communication, and timing of implementation

and reporting. Some banks may also require coordination across multiple

entities and jurisdictions where systems and processes are shared.

Impact

assessment

Assess impact on historical default data to inform policy decisions and

approach to models updates. Broader IT and process impacts also need to be

assessed in detail to allow sufcient lead time to make necessary changes and

to start collecting data on the new basis as early as possible.

Policy

decisions

Dene internal policy and standards, including with regards to available

discretions and jurisdictional discrepancies in the application of the new DoD.

This is ideally informed by the impact assessment, and provides sufcient

guidance for interpretation across models, business lines, and business

processes to be consistent.

IT and process

changes

Implement necessary changes to IT systems and processes, with a view to start

collecting data as early as possible to support the model updates.

Models

Estimate scalars and establish a prioritized plan for model updates, including

other regulatory changes happening ahead of 2021 (e.g., margin of

conservatism), and for changes related to the broader model universe (e.g.,

IFRS9, stress testing etc.).

Regulatory

applications

Banks will seek to prioritize model redevelopment and progressively move

away from the application of scalars and this needs to be managed closely with

the regulators and supervisors.

Parallel run

and reporting

Most banks will be seeking to have a parallel run period for all impacted

reporting, both internal and external.

13New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020 |

Publications

Denition of default

Mar-19

PRA policy statement on the denition of default (PS7/19)

Note: includes materiality thresholds that deviate from those proposed by

the EBA

Nov-18

ECB regulation on the materiality of credit obligations past due ((EU)

2018/1845)

Jun-18

ECB guidance on the process for implementing new denition of default

Note: this was not published but submitted directly to SIIs in the SSM

Dec-17

EBA opinion on the use of the 180 days past due criterion (EBA/

Op/2017/17 )

Oct-17

EC regulation on RTS for the materiality threshold for credit obligations

past due ((EU) 2018/171)

Sep-16

EBA nal draft RTS on the materiality threshold for credit obligations

past due (EBA/RTS/2016/06)

Sep-16

EBA guidelines on the application of the denition of default (EBA/

GL/2016/07)

Sep-16

EBA report on the results from DoD QIS

Mar-16

ECB regulation on the exercise of discretions ((EU) 2016/445)

Note: includes a requirement to use 90 DPD for all exposures, removing the

option for 180 DPD

Jun-15

EC regulation on insolvency proceedings ((EU) 2015/848)

Note: includes a set of arrangements to be considered similar to bankruptcy

under new DoD

Dec-13

EC regulation on RTS for calculating specic and general credit risk

adjustments ((EU) 183/2014)

Jul-13

EBA nal draft RTS on the calculation of specic and general credit risk

adjustments (EBA/RTS/2013/04)

Broader regulatory reform

Dec-17

BCBS publication Basel III: Finalising post-crisis reforms

Apr-16

BCBS report Regulatory consistency assessment programme (RCAP) —

Analysis of RWAs for credit risk in the banking book

14

| New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020

Internal models

Jul-19

EBA progress report on IRB roadmap

Jul-19

ECB guide to internal models — Risk-type-specic topics chapter

Mar-19

EBA guidelines for the estimation of downturn LGD (EBA/GL/2019/03)

Feb-19

EBA guidelines on Credit Risk Mitigation for institutions applying the

IRB approach with own estimates of LGDs (EBA/CP/2019/01)

Nov-18

EBA nal draft RTS on specication of the nature, severity and duration

of an economic downturn (EBA/RTS/2018/04)

Nov-18

ECB guide to internal models — General topics chapter

Mar-18

EBA report on CRM framework

Nov-17

EBA guidelines on PD estimation, LGD estimation and the treatment of

defaulted exposures (EBA/GL/2017/16)

Feb-17

ECB guide for the targeted review of internal models (TRIM)

Jul-16

EBA nal draft RTS on IRB and AMA assessment methodology (EBA/

RTS/2016/03)

Jun-16

EBA nal draft RTS on Risk Weights for specialised lending exposures

(EBA/RTS/2016/02)

May-14

EC regulation (RTS) for assessing material changes of IRB and AMA

approach ((EU) No 529/2014)

Non-performing and forborne exposures

Oct-18

EBA guidelines on management of non-performing and forborne

exposures (EBA/GL/2018/06 )

Apr-17

BCBS guidelines on the prudential treatment of problem assets —

denitions of non-performing exposures and forbearance

Feb-15

EC regulation on ITS with regard to supervisory reporting ((EU)

2015/227)

Jul-14

EBA nal draft ITS on supervisory reporting on forbearance and

non-performing exposures (EBA/ITS/2013/03/rev1)

15New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020 |

Default type Indicator Criteria Additional conditions Default level and contagion

Minimum conditions for return

to non-defaulted status

DPD

(Days past due)

90 DPD

The following conditions are met for an overdue credit obligation:

(1) Total amount overdue is > EUR Y

and

(2) Total amount overdue is > X% of total on-balance exposures

and

(3) Total amount overdue has met conditions (1) and (2) > for 90 consecutive days

and

(4) It is not a technical default

where:

Total amount overdue is the sum of all overdue principal, interest and fees related to the facility, the

obligor (excluding any joint obligations) or the unique set of joint obligors, depending on the level of

default application and credit arrangement

Total on-balance exposure is the total on-balance exposure related to the facility, the obligor (excluding

any joint obligations) or the unique set of joint obligors, depending on the level of default application

and credit arrangement

Y = 100 or different threshold

< 100 per Competent Authority decision for retail exposures

Y = 500 or different threshold

< 500 per Competent Authority decision for corporate exposures

X = 1 or different threshold

≤2.5 per Competent Authority decision

(1) DPD counting should be adjusted

to the new payment schedule (if

applicable) in any of these situations:

(1.1) Repayment is changed,

postponed or suspended by the

obligor in accordance with rights

granted in the contract

(1.2) The obligor has changed due

to merger or acquisition or similar

transaction

(2) DPD counting should be suspended if:

(2.1) Repayment is suspended due

law or legal restrictions

(3) DPD counting may be suspended if:

(3.1) Repayment is subject to

formal dispute

Default should be applied at obligor

level for all exposures except for

retail exposures where default may

be applied at facility level:

(1) For retail exposures where

default applies at obligor level:

(1.1) When a credit obligation

defaults, all other exposures of

the obligor should also default,

including those where the

institution applies default at

facility level

(1.2) When a joint credit

obligation defaults, all other

exposures of the same set of

obligors and of each individual

obligor should also default,

(exceptions apply — see EBA

guidelines)

(1.3) When a company defaults,

all individuals that are fully liable

for the company’s liabilities

should also default

(2) For retail exposures where

default applies at facility level:

(2.1) When a credit obligation

defaults other exposures of

the obligor should not default

unless:

(2.1.1) The institution has

adopted a UTP in line with the

‘pulling effect’

or

(2.1.2) The credit obligation

has defaulted due to a UTP

indicator that has been

classied as reective of the

overall situation of the obligor

3 consecutive months during which no default conditions

are met

This condition also applies to new exposures to the obligor,

in particular if the defaulted exposures have been sold or

written off

UTP

(Unlikeliness

to pay)

Non-accrued

status

The credit obligation is put on non-accrued status (interest stops being recognised in the income

statement due to decreased quality of the credit obligation)

(1) UTP indications should be evaluated

in the event of any of the following

situations (in addition to events

specied by the institution):

(1.1) Repayment has been changed,

postponed or suspended by the

obligor in accordance with rights

granted in the contract

(1.2) Repayment has been

suspended due to or legal

restrictions

(1.3) Concessions have been

extended that do not meet the

conditions of a material distressed

restructuring

(1.4) Purchase or origination of

nancial asset at a material discount

(1.5) One of the obligors of a joint

obligation individually defaults

(1.6) When a company defaults;

owners, partners and signicant

shareholders with limited liability

should be evaluated

(2) Institutions should specify which

UTP indicators reect the overall

situation of the obligor rather than that

of the exposure, and should include (but

is not limited to):

(2.1) Bankruptcy

Specic

Credit Risk

Adjustment

(SCRA)

(1) If the institution uses IFRS9:

(1.1) The credit obligation is classied as Stage 3

and

(1.2) The Stage 3 classication is not triggered by overdue repayment that does not meet the

criteria of a 90 DPD default

or

(2) If the institution uses another accounting framework:

(2.1) A SCRA has been made to the credit obligation

and

(2.2) The SCRA is not IBNR (incurred but not reported)

or

(3) If the institution uses IFRS9 and another accounting framework: it must then choose to consistently

use either (1) or (2)

Sale of the

credit obligation

(1) The credit obligation is sold at an economic loss

and

(2) The sale is credit risk related

and

(3) L > X%, where X is a threshold

≤5% per decision by the institution

where:

L =

E – P

E

L is the economic loss related with the sale of the credit obligation

E is the total outstanding amount of the credit obligation subject to the sale, including interest and fees

P is the price agreed for the sold credit obligation

Distressed

restructuring

(1) Concession have been extended to a debtor facing or about to face nancial difculties, resulting in

a diminished nancial obligation

and

(2) D0 > X%, where X is a threshold

≤1% per decision by the institution

where:

Financial difculties are specied in paragraphs 163-167 and 172-174 of Commission Implementing

Regulation (EU) 2015/227

D0 =

NPV

0 —

NPV

1

NPV

0

D0 is the diminished nancial obligation

NPV

0 is the net present value of the obligation before concessions, discounted using the customer’s

original effective

interest rate

NPV

1

is the net present value of the obligation after concessions, discounted using the customer’s

original effective

interest rate

(1) 12 consecutive months during which no default conditions

are met, counting from the latest of:

(1.1) When concessions where extended

(1.2) When the default was recorded

(1.3) When any grace period in the restructured payment

schedule ended

and

(2) During which a material payment (equivalent to what was

previously past due or written off) has been made by the obligor

and

(3) During which payments have been made regularly according

to the restructured payment schedule

and

(4) There are no past due credit obligations related to the

restructured payment schedule

These conditions also apply to new exposures to the obligor, in

particular if the defaulted exposures have been sold or written off

New DoD on a page

16

| New Denition of Default What needs to be done by 2020

Default type Indicator Criteria Additional conditions Default level and contagion

Minimum conditions for return

to non-defaulted status

DPD

(Days past due)

90 DPD

The following conditions are met for an overdue credit obligation:

(1) Total amount overdue is > EUR Y

and

(2) Total amount overdue is > X% of total on-balance exposures

and

(3) Total amount overdue has met conditions (1) and (2) > for 90 consecutive days

and

(4) It is not a technical default

where:

Total amount overdue is the sum of all overdue principal, interest and fees related to the facility, the

obligor (excluding any joint obligations) or the unique set of joint obligors, depending on the level of

default application and credit arrangement

Total on-balance exposure is the total on-balance exposure related to the facility, the obligor (excluding

any joint obligations) or the unique set of joint obligors, depending on the level of default application

and credit arrangement

Y = 100 or different threshold

< 100 per Competent Authority decision for retail exposures

Y = 500 or different threshold

< 500 per Competent Authority decision for corporate exposures

X = 1 or different threshold

≤2.5 per Competent Authority decision

(1) DPD counting should be adjusted

to the new payment schedule (if

applicable) in any of these situations:

(1.1) Repayment is changed,

postponed or suspended by the

obligor in accordance with rights

granted in the contract

(1.2) The obligor has changed due

to merger or acquisition or similar

transaction

(2) DPD counting should be suspended if:

(2.1) Repayment is suspended due

law or legal restrictions

(3) DPD counting may be suspended if:

(3.1) Repayment is subject to

formal dispute

Default should be applied at obligor

level for all exposures except for

retail exposures where default may

be applied at facility level:

(1) For retail exposures where

default applies at obligor level:

(1.1) When a credit obligation

defaults, all other exposures of

the obligor should also default,

including those where the

institution applies default at

facility level

(1.2) When a joint credit

obligation defaults, all other

exposures of the same set of

obligors and of each individual

obligor should also default,

(exceptions apply — see EBA

guidelines)

(1.3) When a company defaults,

all individuals that are fully liable

for the company’s liabilities

should also default

(2) For retail exposures where

default applies at facility level:

(2.1) When a credit obligation

defaults other exposures of

the obligor should not default

unless:

(2.1.1) The institution has

adopted a UTP in line with the

‘pulling effect’

or

(2.1.2) The credit obligation

has defaulted due to a UTP

indicator that has been

classied as reective of the

overall situation of the obligor

3 consecutive months during which no default conditions

are met

This condition also applies to new exposures to the obligor,

in particular if the defaulted exposures have been sold or

written off

UTP

(Unlikeliness

to pay)

Non-accrued

status

The credit obligation is put on non-accrued status (interest stops being recognised in the income

statement due to decreased quality of the credit obligation)

(1) UTP indications should be evaluated

in the event of any of the following

situations (in addition to events

specied by the institution):

(1.1) Repayment has been changed,

postponed or suspended by the

obligor in accordance with rights

granted in the contract

(1.2) Repayment has been

suspended due to or legal

restrictions

(1.3) Concessions have been

extended that do not meet the

conditions of a material distressed

restructuring

(1.4) Purchase or origination of

nancial asset at a material discount

(1.5) One of the obligors of a joint

obligation individually defaults

(1.6) When a company defaults;

owners, partners and signicant

shareholders with limited liability

should be evaluated

(2) Institutions should specify which

UTP indicators reect the overall

situation of the obligor rather than that

of the exposure, and should include (but

is not limited to):

(2.1) Bankruptcy

Specic

Credit Risk

Adjustment

(SCRA)

(1) If the institution uses IFRS9:

(1.1) The credit obligation is classied as Stage 3

and

(1.2) The Stage 3 classication is not triggered by overdue repayment that does not meet the

criteria of a 90 DPD default

or

(2) If the institution uses another accounting framework:

(2.1) A SCRA has been made to the credit obligation

and

(2.2) The SCRA is not IBNR (incurred but not reported)

or

(3) If the institution uses IFRS9 and another accounting framework: it must then choose to consistently

use either (1) or (2)

Sale of the

credit obligation

(1) The credit obligation is sold at an economic loss

and

(2) The sale is credit risk related

and

(3) L > X%, where X is a threshold

≤5% per decision by the institution

where:

L =

E – P

E

L is the economic loss related with the sale of the credit obligation

E is the total outstanding amount of the credit obligation subject to the sale, including interest and fees

P is the price agreed for the sold credit obligation

Distressed

restructuring

(1) Concession have been extended to a debtor facing or about to face nancial difculties, resulting in

a diminished nancial obligation

and

(2) D0 > X%, where X is a threshold

≤1% per decision by the institution

where:

Financial difculties are specied in paragraphs 163-167 and 172-174 of Commission Implementing

Regulation (EU) 2015/227

D0 =

NPV

0 —

NPV

1

NPV

0

D0 is the diminished nancial obligation

NPV

0 is the net present value of the obligation before concessions, discounted using the customer’s

original effective

interest rate

NPV

1

is the net present value of the obligation after concessions, discounted using the customer’s

original effective

interest rate

(1) 12 consecutive months during which no default conditions

are met, counting from the latest of:

(1.1) When concessions where extended

(1.2) When the default was recorded

(1.3) When any grace period in the restructured payment

schedule ended

and

(2) During which a material payment (equivalent to what was

previously past due or written off) has been made by the obligor

and

(3) During which payments have been made regularly according

to the restructured payment schedule

and

(4) There are no past due credit obligations related to the

restructured payment schedule

These conditions also apply to new exposures to the obligor, in

particular if the defaulted exposures have been sold or written off

17New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020 |

UTP

(Unlikeliness

to pay)

Bankruptcy

(1) The institution has led for

or

(2) The obligor has sought (where this would avoid or delay repayment of the credit obligation)

or

(3) The obligor has been placed in (where this would avoid or delay repayment of the credit obligation)

any of the following arrangements:

(.1) Bankruptcy as recognised in applicable law

or

(.2) Any other arrangement listed in Annex A to Regulation (EU) 2015/848

or

(.3) Any arrangement deemed similar to bankruptcy as specied by the institution based on applicable

law and EBA guidelines

(1) UTP indications should be evaluated

in the event of any of the following

situations (in addition to events

specied by the institution):

(1.1) Repayment has been changed,

postponed or suspended by the

obligor in accordance with rights

granted in the contract

(1.2) Repayment has been

suspended due to or legal

restrictions

(1.3) Concessions have been

extended that do not meet the

conditions of a material distressed

restructuring

(1.4) Purchase or origination of

nancial asset at a material discount

(1.5) One of the obligors of a joint

obligation individually defaults

(1.6) When a company defaults;

owners, partners and signicant

shareholders with limited liability

should be evaluated

(2) Institutions should specify which

UTP indicators reect the overall

situation of the obligor rather than that

of the exposure, and should include (but

is not limited to):

(2.1) Bankruptcy

Default should be applied at obligor

level for all exposures except for

retail exposures where default may

be applied at facility level:

(1) For retail exposures where

default applies at obligor level:

(1.1) When a credit obligation

defaults, all other exposures of

the obligor should also default,

including those where the

institution applies default at

facility level

(1.2) When a joint credit

obligation defaults, all other

exposures of the same set of

obligors and of each individual

obligor should also default,

(exceptions apply — see EBA

guidelines)

(1.3) When a company defaults,

all individuals that are fully liable

for the company’s liabilities

should also default

(2) For retail exposures where

default applies at facility level:

(2.1) When a credit obligation

defaults other exposures of

the obligor should not default

unless:

(2.1.1) The institution has

adopted a UTP in line with the

‘pulling effect’

or

(2.1.2) The credit obligation

has defaulted due to a UTP

indicator that has been

classied as reective of the

overall situation of the obligor

3 consecutive months during which no default conditions

are met

This condition also applies to new exposures to the obligor,

in particular if the defaulted exposures have been sold or

written off

Additional

indications

of unlikeliness

to pay

The credit obligation meets criteria that the institution has dened for additional indications of

unlikeliness to pay, which should or may directly trigger default, or trigger a case-by-case assessment

of default (depending on indicator):

(1) Such indicators should include:

(1.1) The institution uses an accounting framework under which:

(1.1.1) The credit obligation is recognised as impaired even if no SCRA has been assigned

and

(1.1.2) The impairment is not IBNR (incurred but not reported)

(1.2) Credit fraud

(1.3) Rules for contagion in the occurrence of default in a group of connected clients

(1.4) In case of purchase or origination of a nancial asset at a material discount:

(1.4.1) Rules for assessing any deteriorated credit quality of the obligor

(2) Such indicators may include (but are not limited to):

(2.1) Same criteria as DPD default category but with institution dened thresholds that are lower

than those dened by the CA

(2.2) The obligor’s source of income to repay loan is no longer available

(2.3) There are justied concerns about the obligor’s ability to generate stable and sufcient cash ows

(2.4) The obligor’s leverage has increased signicantly

(2.5) Breach of the covenants of a credit contract

(2.6) Collateral has been called by the institution

(2.7) Default of a company fully owned by the obligor, where the obligor has provided a personal

guarantee for that company’s obligations

(2.8) ‘Pulling effect’ in line with the ITS with regard to supervisory reporting ((EU) 2015/227)

with the same or different threshold

(2.9) The obligation is reported as non-performing under Commission Implementing Regulation

(EU) 680/2014

(2.10) Signicant delays in payments to other creditors

(2.11) A crisis in the sector of the obligor combined with a weak position of the obligor

(2.12) Disappearance of an active market for an asset because of the nancial difculties

of the obligor

(2.13) In case concessions have been extended that do not meet the conditions of a material

distressed restructuring:

(2.13.1) Large lumpsum payment at the end of the repayment schedule

(2.13.2) Signicantly lower payments at the beginning of repayment schedule

(2.13.3) Signicant grace period at the beginning of the repayment schedule

(2.13.4) The exposures to the obligor have been subject to distressed restructuring more than once

Notes:

1. New DoD on a page is intended as a quick reference guide for the basic logic of the new denition and does not cover the entire regulatory scope; in

particular, it does not cover requirements related to external data, default consistency and governance

2. All default indicators apply to all credit obligations toward the institution, the parent undertaking and its subsidiaries

For an A2–version of New DoD on a page please download it from our website at www.ey.com/NewDenitionOfDefault.

18

| New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020

UTP

(Unlikeliness

to pay)

Bankruptcy

(1) The institution has led for

or

(2) The obligor has sought (where this would avoid or delay repayment of the credit obligation)

or

(3) The obligor has been placed in (where this would avoid or delay repayment of the credit obligation)

any of the following arrangements:

(.1) Bankruptcy as recognised in applicable law

or

(.2) Any other arrangement listed in Annex A to Regulation (EU) 2015/848

or

(.3) Any arrangement deemed similar to bankruptcy as specied by the institution based on applicable

law and EBA guidelines

(1) UTP indications should be evaluated

in the event of any of the following

situations (in addition to events

specied by the institution):

(1.1) Repayment has been changed,

postponed or suspended by the

obligor in accordance with rights

granted in the contract

(1.2) Repayment has been

suspended due to or legal

restrictions

(1.3) Concessions have been

extended that do not meet the

conditions of a material distressed

restructuring

(1.4) Purchase or origination of

nancial asset at a material discount

(1.5) One of the obligors of a joint

obligation individually defaults

(1.6) When a company defaults;

owners, partners and signicant

shareholders with limited liability

should be evaluated

(2) Institutions should specify which

UTP indicators reect the overall

situation of the obligor rather than that

of the exposure, and should include (but

is not limited to):

(2.1) Bankruptcy

Default should be applied at obligor

level for all exposures except for

retail exposures where default may

be applied at facility level:

(1) For retail exposures where

default applies at obligor level:

(1.1) When a credit obligation

defaults, all other exposures of

the obligor should also default,

including those where the

institution applies default at

facility level

(1.2) When a joint credit

obligation defaults, all other

exposures of the same set of

obligors and of each individual

obligor should also default,

(exceptions apply — see EBA

guidelines)

(1.3) When a company defaults,

all individuals that are fully liable

for the company’s liabilities

should also default

(2) For retail exposures where

default applies at facility level:

(2.1) When a credit obligation

defaults other exposures of

the obligor should not default

unless:

(2.1.1) The institution has

adopted a UTP in line with the

‘pulling effect’

or

(2.1.2) The credit obligation

has defaulted due to a UTP

indicator that has been

classied as reective of the

overall situation of the obligor

3 consecutive months during which no default conditions

are met

This condition also applies to new exposures to the obligor,

in particular if the defaulted exposures have been sold or

written off

Additional

indications

of unlikeliness

to pay

The credit obligation meets criteria that the institution has dened for additional indications of

unlikeliness to pay, which should or may directly trigger default, or trigger a case-by-case assessment

of default (depending on indicator):

(1) Such indicators should include:

(1.1) The institution uses an accounting framework under which:

(1.1.1) The credit obligation is recognised as impaired even if no SCRA has been assigned

and

(1.1.2) The impairment is not IBNR (incurred but not reported)

(1.2) Credit fraud

(1.3) Rules for contagion in the occurrence of default in a group of connected clients

(1.4) In case of purchase or origination of a nancial asset at a material discount:

(1.4.1) Rules for assessing any deteriorated credit quality of the obligor

(2) Such indicators may include (but are not limited to):

(2.1) Same criteria as DPD default category but with institution dened thresholds that are lower

than those dened by the CA

(2.2) The obligor’s source of income to repay loan is no longer available

(2.3) There are justied concerns about the obligor’s ability to generate stable and sufcient cash ows

(2.4) The obligor’s leverage has increased signicantly

(2.5) Breach of the covenants of a credit contract

(2.6) Collateral has been called by the institution

(2.7) Default of a company fully owned by the obligor, where the obligor has provided a personal

guarantee for that company’s obligations

(2.8) ‘Pulling effect’ in line with the ITS with regard to supervisory reporting ((EU) 2015/227)

with the same or different threshold

(2.9) The obligation is reported as non-performing under Commission Implementing Regulation

(EU) 680/2014

(2.10) Signicant delays in payments to other creditors

(2.11) A crisis in the sector of the obligor combined with a weak position of the obligor

(2.12) Disappearance of an active market for an asset because of the nancial difculties

of the obligor

(2.13) In case concessions have been extended that do not meet the conditions of a material

distressed restructuring:

(2.13.1) Large lumpsum payment at the end of the repayment schedule

(2.13.2) Signicantly lower payments at the beginning of repayment schedule

(2.13.3) Signicant grace period at the beginning of the repayment schedule

(2.13.4) The exposures to the obligor have been subject to distressed restructuring more than once

3. Special conditions apply to factoring arrangements and purchased receivables

4. Conditions related to the 180 days option have been excluded given that this option is being disallowed

19New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020 |

20

| New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020

Key contacts and

country representatives

Country representatives

Key contacts

Lionel Stehlin

T: +44 20 7951 2432

E: lst[email protected]y.com

Nicolai Molund

T: +44 20 7197 7071

E: nicolai.molund@uk.ey.com

Thorsten Stetter

T: +49 711 9881 16374

E: thorsten.stetter@de.ey.com

21New denition of default What banks need to do by the end of 2020 |

United Kingdom

Richard Brown

T: +44 20 795 15564

E: rbrown2@uk.ey.com

Switzerland

André Dylan Kohler

T: +41 58 286 3378

E: andre-dylan.kohler@ch.ey.com

Nordics

Pehr Ambuhm

T: +46 8 52059682

E: pehr.ambuhm@se.ey.com

Italy

Giuseppe Quaglia

T: +39 2722 122 429

E: giuseppe[email protected]y.com

Ireland

Cormac Murphy

T: +353 1221 2750

E: cormac.murph[email protected]y.com

Belgium

Frank De Jonghe

T: +32 2 774 9956

E: frank.de.jonghe@be.ey.com

Poland

Pawel Preuss

T: +48 225577530

E: pawel.preuss@pl.ey.com

Austria

Heiner Klein

T: +43 1 21170 1443

E: heiner.klein@at.ey.com

Germany

Max Weber

T: +49 711 9881 15494

E: max.weber@de.ey.com

France

Jean-Michel Bouhours

T: +33 1 46 93 51 61

E: jean.michel.bouhours@fr.ey.com

Netherlands

Wimjan Bos

T: +31 88 40 71719

E: wimjan.bos@nl.ey.com

Luxembourg

Olivier Marechal

T: +352 42 124 8948

E: olivier.mar[email protected]y.com

Spain

Ignacio Medina

T: +34 915727579

E: ignacio.medina@es.ey.com

Portugal

Rita Costa

T: +35 1217912282

E: rita.costa@pt.ey.com

Central Eastern Europe

Tomáš Němeček

T: +420 731 627 149

E: tomas.nemecek@cz.ey.com

EY | Assurance | Tax | Transactions | Advisory

About EY

EY is a global leader in assurance, tax, transaction and advisory

services. The insights and quality services we deliver help build trust

and confidence in the capital markets and in economies the world

over. We develop outstanding leaders who team to deliver on our

promises to all of our stakeholders. In so doing, we play a critical role

in building a better working world for our people, for our clients and for

our communities.

EY refers to the global organization, and may refer to one or more, of

the member firms of Ernst & Young Global Limited, each of which is

a separate legal entity. Ernst & Young Global Limited, a UK company

limited by guarantee, does not provide services to clients. Information

about how EY collects and uses personal data and a description of the

rights individuals have under data protection legislation are available

via ey.com/privacy. For more information about our organization, please

visit ey.com.

© 2019 EYGM Limited.

All Rights Reserved.

EYG no. 004741-19Gbl

EY-0000100574.indd (UK) 11/19

Artwork by Creative Services Group London.

ED None

In line with EY’s commitment to minimize its impact on the environment, this document

has been printed on paper with a high recycled content.

This material has been prepared for general informational purposes only and is not intended to

be relied upon as accounting, tax or other professional advice. Please refer to your advisors for

specific advice.

ey.com