Technical Report

NREL/TP-6A2-44930

July 2009

Renewable Energy Project

Financing: Impacts of

the Financial Crisis

and Federal Legislation

Paul Schwabe, Karlynn Cory, and

James Newcomb

National Renewable Energy Laboratory

1617 Cole Boulevard, Golden, Colorado 80401-3393

303-275-3000

•

www.nrel.gov

NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy

Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy

Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC

Contract No. DE-AC36-08-GO28308

Technical Report

NREL/TP-6A2-44930

July 2009

Renewable Energy Project

Financing: Impacts of

the Financial Crisis

and Federal Legislation

Paul Schwabe, Karlynn Cory, and

James Newcomb

Prepared under Task No. SAO7.9B30

NOTICE

This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government.

Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any

warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or

usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not

infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by

trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement,

recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and

opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States

government or any agency thereof.

Available electronically at

http://www.osti.gov/bridge

Available for a processing fee to U.S. Department of Energy

and its contractors, in paper, from:

U.S. Department of Energy

Office of Scientific and Technical Information

P.O. Box 62

Oak Ridge, TN 37831-0062

phone: 865.576.8401

fax: 865.576.5728

email:

mailto:reports@adonis.osti.gov

Available for sale to the public, in paper, from:

U.S. Department of Commerce

National Technical Information Service

5285 Port Royal Road

Springfield, VA 22161

phone: 800.553.6847

fax: 703.605.6900

email:

[email protected]world.gov

online ordering:

http://www.ntis.gov/ordering.htm

Printed on paper containing at least 50% wastepaper, including 20% postconsumer waste

iii

Acknowledgments

This work was funded, in part, by the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Energy Efficiency

and Renewable Energy Commercialization Program. The authors wish to thank participating

DOE staff—Wendolyn Holland and Carol Battershell—for providing useful insights and overall

direction in the early stages of this effort. The authors are also grateful for the guidance and

helpful input of the project managers, Gian Porro and Bill Babiuch, of the National Renewable

Energy Laboratory (NREL). We would also like to thank Rachel Gelman for her extensive

background research as well the individuals who reviewed various drafts of this report, including

Douglas Arent, Jason Coughlin, Ted James, David Kline, Jeffrey Logan, Margaret Mann, and

Michael Mendelsohn, all of NREL. The authors also thank Sean Coletta, MMA Renewable

Ventures; Laura Ellen Jones, Hunton & Williams LLP; Matthew Karcher, Deacon Harbor

Financial; Alex Kramarchuk, EyeOn Energy Ltd.; Daniel Sinaiko, Chadbourne & Parke LLP;

and Ethan Zindler, New Energy Finance.

The authors are also grateful to the interviewees for providing their insights into current

renewable energy market conditions and for providing additional clarifications. Thank you to

Richard Ashby, RES Americas; John Burges, Think Energy Partners LLP; Sean Coletta, MMA

Renewable Ventures; Kim Fiske, Iberdrola Renewables; Rob Glen, New Energy Finance;

Gaurab Hazarika, Duke Energy; Laura Ellen Jones, Hunton & Williams LLP; Matthew Karcher,

Deacon Harbor Financial; Alex Kramarchuk, EyeOn Energy Ltd.; Lance Markowitz, Union

Bank of California; Craig Mataczynski, RES Americas; John McKinsey, Stoel Rives LLP;

Stephen O’Rourke, Deutsche Bank Securities; Jerry Peters, TD Banknorth; Charles

Ricker, Bright Source Energy; Dale Rogers, eSolar; Partho Sanyal, Merrill Lynch; Daniel

Sinaiko, Chadbourne & Parke LLP; Parker Weil, Merrill Lynch; and Ethan Zindler, New Energy

Finance.

Finally, the authors also offer their gratitude to Michelle Kubik in NREL’s Technical

Communications Office for providing editorial support and to NREL’s Jim Leyshon for his

graphics support.

iv

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments.................................................................................................................................. iii

Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... iv

List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... iv

List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................... iv

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. v

1 The Renewable Energy Project Investment Context ............................................................................ 1

2 Financial Market Factors Affecting Renewable Energy Project Finance ............................................. 1

3 Traditional Tax Equity Investment Has Contracted ............................................................................. 2

3.1 Renewable Energy Project Investment Yields Significant Tax Benefits ....................................... 2

3.2 Historically, Renewables Attracted Fewer Than 20 Large Tax Equity Investors ......................... 2

3.3 Available Tax Equity Investment Will Be Insufficient to Support Near-Term Renewable Energy

Projects ................................................................................................................................................. 3

3.4 Upward Pressure on Tax Equity Investment Returns .................................................................... 5

4 Debt Financing for Renewable Projects ............................................................................................... 6

4.1 Illiquid Debt Market Results From the Financial Crisis ................................................................ 6

4.2 Interest Rates on Renewable Energy Debt Unclear; Expected Upward Trend ............................. 6

5 Federal Policy Solutions ....................................................................................................................... 7

5.1 Effectiveness of EESA Unclear ..................................................................................................... 7

5.2 Effectiveness of ARRA’s Renewable Energy Provisions Yet to Be Determined ......................... 8

5.3 Measures to Monitor the Impact of Federal Legislation on RE Project Development .................. 9

6 New Investor Opportunities ................................................................................................................ 10

6.1 New Tax Equity Investors Anticipated ........................................................................................ 10

6.2 Utilities Increasingly Interested in Project Ownership and Tax Equity Investments .................. 10

7 Factors Influencing Future RE Project Development and Financing ................................................. 11

8 Conclusions ......................................................................................................................................... 13

References .............................................................................................................................................. 14

Appendix. Select Federal Legislation in 2008 and 2009 ....................................................................... 17

Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 ............................................................................... 17

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 .......................................................................... 17

List of Figures

Figure ES1. Impacts of the financial crisis and federal legislation on renewable energy project

development ....................................................................................................................................... vi

Figure 1. Recent and expected tax equity investors ................................................................................. 4

Figure 2. Impacts of the financial crisis and federal legislation on renewable energy project

development ...................................................................................................................................... 12

List of Tables

Table ES1. Summary of Current Financial Issues for Renewable Energy Projects .............................. vii

Table A1. Select Tax Provisions Addressing EERE Sectors ................................................................. 18

v

Executive Summary

Extraordinary financial market conditions have disrupted the flows of equity and debt investment into

U.S. renewable energy (RE) projects since the fourth quarter of 2008. The pace and structure of

renewable energy project finance has been reshaped by a combination of forces, including the

financial crisis, global economic recession, and major changes in federal legislation affecting

renewable energy finance. This report explores the impacts of these key market events on renewable

energy project financing and development.

Tax credit incentives have been a principal driver of investment in renewable energy projects, but

have become largely ineffective in the current economic climate. Reduced corporate tax liabilities

have sharply diminished the amount of tax-related investment funneled to renewable energy projects

by traditional “tax equity” investors including large investment banks, commercial banks, and

insurance companies. The pool of large tax equity investors was small to begin with—including only

about 20 institutions in 2008—but has shrunk to approximately four to six active institutions in early

2009. The amount of tax equity investment available from traditional sources will be insufficient to

fully support near-term renewable energy project development. However, utilities and other new

investors may increasingly invest in renewable energy projects as new federal provisions become

available.

Meanwhile, availability of debt funding to finance renewable energy projects is also limited as a result

of global credit tightening. Lenders to renewable energy development are conserving capital and

limiting their lending activities. The difficulty in obtaining debt is expected to increase borrowing

costs for project developers; however, exact interest rates for debt on renewable energy projects are

difficult to discern because relatively few projects are being financed in the commercial market.

U.S. federal legislation passed in February 2009 in response to the economic downturn included two

key renewable energy provisions aimed at increasing the availability of financing for renewable

energy projects:

• temporary grants provided in lieu of tax credits, and

• loan guarantees for innovative and commercial projects.

At the time of this writing, it is too early to assess definitively the degree to which the enactment of

U.S. federal legislation may serve the renewable energy industry from today’s market conditions.

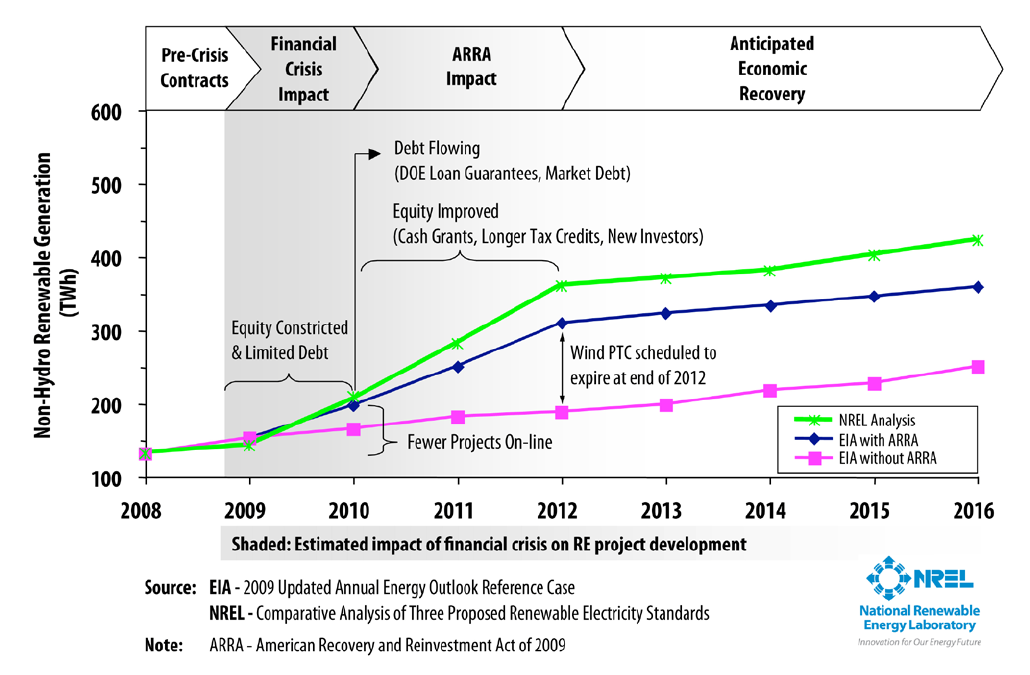

Figure ES1 depicts the potential implications of recent events for non-hydro renewable electricity

generation. In the wake of the financial crisis, some renewable energy project development has

continued. For instance, more than 2,800 MW of wind capacity was installed in the first quarter of

2009 (AWEA 2009b). However, much of the financing for these projects was secured prior to the

height of the financial crisis, and commitments were honored by project investors. Accordingly, the

most acute impact of the financial crisis on renewable energy project development could be

experienced in the second half of 2009. This is the period after the completion of pre-financial crisis

commitments, but before the impacts of U.S. federal legislation or broader economic recovery.

vi

Figure ES1. Impacts of the financial crisis and federal legislation on

renewable energy project development

As programs targeting renewable energy project financing and development are implemented,

administrative factors could influence their effectiveness. The cash grant and loan guarantee programs

included in the 2009 federal legislation will provide crucially needed stimulus to equity and debt

investments. Thus, the speed and effectiveness of program implementation and administration will

shape the outcomes.

Table ES1 provides a summary of current financial issues impacting renewable energy project

development and financing.

vii

Table ES1. Summary of Current Financial Issues for Renewable Energy Projects

Issue

Potential Impact

Current Status

Market

Challenges

The

financial

crisis

Marked slowdown in project

development in 2009, with possible

rebound in 2010.

1. Projects with financing prior to October 2008 have

continued to move forward.

2 Many projects envisioned for 2009 have been delayed.

3. Impact of new federal legislation will begin to be seen

in 2009-2010.

Tax Equity Financing Challenges

Tax

liability

appetite

New projects have difficulty finding

investors able to efficiently take the

tax credits.

Major investors are absorbing the losses of merged or

acquired companies; their tax appetite has decreased.

Investment tax credit (ITC) and production tax credit

(PTC) rule changes and DOE loan guarantees may help,

but implementation may take several months.

Investor

pool

In 2008, RE projects were financed

by less than 20 traditional RE tax

equity investors.

In early 2009, approx. four to six traditional investors

remain active. The new deals getting financed are the

best projects with solid management teams; an investor

“flight to quality.” New investors could emerge.

PTC

limitations

If investor pays alternative minimum

tax (AMT), PTC may be limited to four

years. Long-term uncertainty about

PTC remains.

Recovery legislation in 2009 extended PTC for additional

three years and made it possible to take ITC in lieu of

PTC through 2012.

Passive-

loss and

at-risk

rules

It is challenging for individuals to take

PTC and ITC directly, on their income

tax return, or by investing in a fund or

together in a partnership.

No changes expected.

Debt

Financing

Challenges

Credit

availability

Credit markets have tightened and

debt liquidity has dramatically

declined.

New federal legislation may help, but the impact on credit

availability remains uncertain.

Debt for

wind

Wind projects use debt (1) for

construction loans and (2) as down

payment to secure wind turbines

RE developers without proper credit may not be able to

use debt for construction costs. With increased risk,

manufacturers might require larger down payments.

1

1 The Renewable Energy Project Investment Context

The rapid expansion of renewable energy capacity in the United States in recent years has

generated an enormous need for project-capital investment. In 2007, solar photovoltaic (PV)

installations grew by 45% (Prometheus 2007), and wind capacity grew 46%, which resulted in an

estimated $9 billion in investments (DOE 2008). In 2008, PV installations grew by 81% (SEIA

2009), and the American Wind Energy Association reported that installed wind power capacity

grew by 50%, supported by $17 billion in investments (AWEA 2009a). In the past few years,

renewable energy development has flourished and, until recently, the availability of capital

investment had not been a constraint on developing new projects.

Beginning in 2008 and continuing to 2009, conditions shifted with the combined effects of two

main forces that influenced renewable energy project development. First, renewable energy tax

credits set to expire at the end of 2008 were not reauthorized by the federal government until the

fourth quarter of 2008, slowing the pace of investment while investors waited for a decision on

the extension of the credits. Second, the financial crisis and the downturn in the U.S. economy

slowed renewable energy investment.

The federal government’s response to the economic contraction has emphasized broad economic

stimulus, including sweeping revisions to renewable energy incentives. However, it remains

difficult to assess the degree to which these measures will offset the impact of the economic

downturn on the financing of renewable energy projects. This report explores the impacts of

market events and recently adopted federal policies that will affect new renewable energy project

development. Our analysis focuses primarily on the perspectives of traditional renewable energy

project investors as opposed to renewable energy technology advancement investors such as

venture capital firms.

To understand the direct impacts of the U.S. financial crisis on renewable project financing,

NREL reviewed recent publications and news articles, and conducted a series of interviews with

20 experts in renewable energy finance. Participating organizations included banks and financial

service companies, prominent renewable energy developers, law firms, utilities, consultants, and

think tanks. The interviews focused on availability and cost of renewable energy capital

(including debt and equity), implications on current and future projects, possible actions by the

U.S. Department of Energy and the federal government, as well as the impacts of new policies.

2 Financial Market Factors Affecting Renewable Energy Project

Finance

While renewable energy project installations have flourished in recent years, an extraordinary

combination of recent events has reshaped the pace and structure of renewable energy project

finance.

First, through much of 2008, investors expected that the production tax credit (PTC) would

expire at the end of the year and that the 30% investment tax credit (ITC) for solar would revert

2

back to 10%. This situation accelerated efforts to complete projects in the short term, but

undermined development of projects that would need financing in 2009 and beyond. Because the

economic benefits of the tax credits could not be relied on for projects financed in 2009 and

beyond, planning and development efforts for these longer-term projects slowed.

Second, renewable energy industries were exposed to the highly turbulent financial markets and

a contraction of economic activity. The result was a dramatic tightening of credit availability.

Several of the largest institutions investing in renewable energy either ceased to exist, skirted

solvency, or required government intervention.

In response to the economic crisis, the U.S. Congress passed two pieces of legislation that

contained provisions that it hopes will assist renewable energy industry growth. The Emergency

Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (EESA) was passed in October 2008 as an effort to restore

confidence and functionality of the financial markets. The American Recovery and Reinvestment

Act of 2009 (ARRA), signed in February 2009, offered nearly $800 billion in tax cuts and

spending to promote economic recovery (Weiss 2009). The extent to which these measures will

succeed in stimulating a resurgence remains unclear. However, the provisions encompassed in

these two pieces of legislation, taken together, bring far-reaching changes to the landscape of

renewable energy project finance.

3 Traditional Tax Equity Investment Has Contracted

The economic downturn has had a direct and severe impact on investment in renewable energy

projects, reducing the ability of project owners to take advantage of tax incentives.

3.1 Renewable Energy Project Investment Yields Significant Tax Benefits

The U.S. federal government has incentivized new renewable energy projects by offering

sizeable federal tax credits and deductions to companies and homeowners that invest in

renewable energy systems. In addition to the PTC and ITC, commercial and industrial owners of

renewable energy projects also are able to accelerate the depreciation of qualifying renewable

energy equipment through the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS). The

economic value of the combined tax benefits

1

is considerable—close to 50% of a solar

photovoltaic system’s installed cost can be recovered through the ITC and accelerated

depreciation (Cory et al. 2009). For a wind project using the PTC, the present value of the

combined tax benefits sometimes can exceed the system’s cash revenues from the sale of

electricity and renewable energy certificates

2

3.2 Historically, Renewables Attracted Fewer Than 20 Large Tax Equity Investors

(RECs) (Harper et al. 2007).

Renewable energy project developers typically do not have tax liabilities large enough to

efficiently capture the full amount of tax credits available for large projects. To overcome this,

1

The combined tax benefits are PTC and MACRS for wind, and ITC and MACRS for solar. Neither of the estimates

for solar or wind include the MACRS bonus depreciation schedule in place in 2008 and 2009 – 50% in the first year.

2

This will be dependent on a number of location-specific factors that are constantly changing, including amount of

wind generated, electric generation price, and local REC prices. For a while, this was true in Texas, until

transmission constraints led to wind generation curtailment.

3

developers partner with passive “tax equity investors” to efficiently use the federal tax benefits

generated by their projects. A tax equity investor typically invests in a renewable energy project

by contributing capital investment, which secures tax benefits and a return on investment from

the project.

Traditionally, tax equity investors have been very large, tax-paying corporations seeking to offset

some portion of their expected tax liability. In the past few years, fewer than 20 U.S. taxable

entities acted as tax equity investors, including large investment banks, commercial banks, or

insurance companies (Chadbourne & Parke 2009b). The pool of such investors was highly

concentrated in the financial industry and included AIG, CitiBank, Wachovia, Lehman Brothers,

Merrill Lynch, and Wells Fargo, among others.

The number of tax equity investors was small for several reasons. First, tax equity investors must

have prohibitively large tax liabilities to absorb the tax credits. In the case of the PTC, this tax

liability must remain for 10-11 years to efficiently use the tax credits. Second, prior to the

enactment of EESA, the alternative minimum tax (AMT)

3

nullified potential benefits of the

credits for some potential investors, primarily because corporations paying the AMT were not

allowed to take the ITC. Third, barriers to noninstitutional investors, known as “passive-loss and

at-risk rules,” made it challenging for individuals to take the PTC and ITC directly on their

personal income taxes. Thus, partnerships of high net-worth individuals with large tax appetites

were not significant investors in renewable energy tax equity investments. Together, these

factors prevented otherwise interested tax equity investors from investing in renewable energy

projects for tax-benefit purposes.

3.3 Available Tax Equity Investment Will Be Insufficient to Support Near-Term

Renewable Energy Projects

Profitable tax-paying entities are a fundamental driver of the U.S. renewable energy tax-benefit

model. Without adequate tax liability, traditional tax credits and deductions cannot be used

efficiently and, therefore, do not entice renewable energy investment. And while recent federal

legislation has attempted to address this need in the short term (discussed in Section 5), the

uncertainty surrounding the execution of those laws means that tax equity continues to be the

main source of RE project investment through the first half of 2009.

Interviewees observed that the market for traditional tax equity investment has declined

substantially both in the number of tax equity players and the actual funds available to invest.

The number of investors has fallen as a result of insolvencies, bankruptcies, and consolidation.

Frequently mentioned examples of such firms were AIG, Lehman Brothers, and Merrill Lynch.

Additionally, in a merger and acquisition arrangement, an acquiring corporation must absorb any

losses incurred by the acquired company (e.g., Wells Fargo absorbs Wachovia’s losses). This

further erodes the resulting entity’s remaining profitability base and likely tax liabilities, which

affects their probable amount of tax equity investment in the future. According to discussions

3

The alternative minimum tax is a secondary tax system with separate rules and rates; taxpayers must pay the

greater of either the AMT, or their regular taxes (including all tax credits and deductions). The AMT is designed to

prevent individuals and corporations from reducing their income tax liability below a certain level (hence, it is a

minimum tax level that must be paid).

4

during a webinar hosted by Chadbourne & Parke, only about four traditional tax equity investors

remain active in early 2009 (Chadbourne & Parke 2009b).

As shown in Figure 1, Hudson Clean Energy Partners foresees a sharp contraction in the pool of

active tax equity investors in 2009 (down to four to six), with possible recovery in future years.

4

Because today’s market is in flux, other tax equity investors may exist and circumstances may

change for current investors.

Source: Hudson 2009

Figure 1. Recent and expected tax equity investors

Under current circumstances, a syndicate of several investors may be required to support a

project because the funding pool of available tax equity investment is limited in the short term.

This increases transactions costs and slows project development. As a result, renewable energy

project development has slowed overall and only the best projects with solid management teams

4

For example, in December 2008, Darren Van’t Hof, a vice president with U.S. Bancorp Community Development

Corporation said “As far as the bank is concerned, we have a strong tax credit appetite. We have good cash and

liquidity positions. We are open for business. We are not actually doing any wind right now. We are not doing

geothermal or biomass. We looked at wind a year ago and it wasn’t that appealing. We might look at it again.”

(Chadbourne & Parke 2009b).

5

are likely to move forward in the short term. This was repeatedly described as a “flight to

quality” by investors.

Responses and highlights from expert interviews

Tax liabilities of remaining traditional tax equity investors

:

3.4 Upward Pressure on Tax Equity Investment Returns

Tax equity investors receive tax benefits equal to their initial capital contribution plus a return on

the investment known as the internal rate of return (IRR). As a result of the tax equity market

contraction, projects must compete for the limited sources of investment, and thus the rates of

return necessary to attract investment have increased.

In early to mid-2008, deals were completed with tax equity IRR being in the mid-7% range

(Chadbourne & Parke 2009b). However, renewable energy project IRRs must also compete with

other tax equity investment opportunities such as affordable housing that set an effective floor on

rates of return. Affordable housing is typically seen as a less-risky tax equity investment

opportunity because it poses no operational risk (i.e., tax credits are received at the time of

investment, not based on production, as with the PTC). Today, affordable housing yields are in

the mid-8% range and trending upward (Chadbourne & Parke 2009b). While no specific

consensus emerged, interviewees indicated that equity returns necessary to attract renewable

energy project investment may increase anywhere from mid-8% to as high as 15%.

Tax equity IRR

Responses and highlights from expert interviews:

• “This was not a large universe to begin with.”

• Tax equity investment has“completely and totally dried up.”

• This is “unlike anything we have ever seen.”

• Tax equity investors are “running for shelter.”

• “Only four tax equity investors remain active.”

• “We are open for business, but we are looking for high-quality off-takers, warranties,

and low operating risk.”

•

“Tax equity takers at any price.”

• “Projects are chasing capital.”

• “Before, a developer was able to get a commitment on tax equity yields for

several months that could be locked in...Now, the longer it takes to finance a

project, the more uncertain [are the] IRRs.”

• “An IRR of 7%-8% will not be high enough for renewable energy to compete

for equity; renewables compete with affordable housing, and their yields are in

the 8.X% range, and are trending upward. The advantage of affordable

housing is there is no performance risk.”

6

4 Debt Financing for Renewable Projects

Although not as common as the tax equity model of finance, some renewable energy projects

have used project- or corporate-level debt to fund development. Most renewable energy debt

lending has happened at the corporate level as a backstop to equity investment in one or more

projects. At the project level, debt is more commonly used—particularly for wind projects—

during project construction, although it is used on occasion to secure capital for the project itself.

4.1 Illiquid Debt Market Results From the Financial Crisis

As a result of the financial crisis and a tightening of credit worldwide, debt markets have seen a

dramatic reduction in liquidity. For project developers, the availability of debt financing

decreased significantly in 2008 and the first half of 2009 as the market shifted from borrower-

oriented to creditor-friendly. Debt lending for U.S. renewable energy projects has been

dominated by a small number of European banks, and key lenders such as Fortis and Dexia are

facing financial difficulties. As such, the pool of active debt lenders is limited in the short term.

The loan guarantees

5

However, it will take time for the Department of Energy to set up the loan guarantee system—

and as of June 2009, the market does not understand the process of application and approval. To

accelerate this process, Secretary of Energy Steven Chu has announced changes to the way that

grants and loans are offered from the department (DOE 2009). These changes are anticipated to

accelerate funding distribution and quickly establish support mechanisms for developers who

want to secure debt financing.

offered in ARRA and administered by the Department of Energy may

increase the availability of project-level debt to finance renewable energy projects.

Debt-lending availability

Responses and highlights from expert interviews:

4.2 Interest Rates on Renewable Energy Debt Unclear; Expected Upward Trend

Interest rates for debt on renewable energy projects are unclear because little, if any, debt is

being financed in the commercial market. Without transactions, there is little data to quantify

interest rates. Before the financial crisis, renewable energy project debt was reported to be at a

premium of approximately 200-300 basis points (Chadbourne & Parke 2009b) above a public

financial indicator, such as LIBOR.

6

5

For more details, see Section 5 or the Appendix.

This cost of debt financing is likely to increase as project

6

London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) is the rate at which banks will borrow from other banks. LIBOR is a

standard benchmark for short-term interest rates (Investopedia 2009).

• “Precipitous reduction in liquidity.”

• “Debt market was effectively closed for Q4 of 2008.”

• Debt markets are still closed in early 2009 – “we need to understand how the

DOE loan guarantees will work.”

• Banks are “retrenching”

• “Where on Earth is lending available?”

7

borrowers may pay a higher premium to secure the limited capital, despite reductions in general

interest rates by central banks (Doyle 2009).

There was a general consensus among interviewees that the risk from debt has been repriced to

higher levels because previous debt lenders may be conserving capital. Interviewees indicated

that it was difficult to tell where the exact interest rates for RE projects stand without execution

of landmark deals. There was no agreement where future debt interest rates for renewable energy

projects would settle.

In addition, analysts speculate that the maximum term of debt for a renewable project is likely to

top out at 15 years or less, but the term will depend on technology and other project-specific

factors such as the length of off-take contract (ACORE 2008).

Interest rates

Responses and highlights from expert interviews:

5 Federal Policy Solutions

In 2008 and 2009, the U.S. Congress enacted new legislation in an attempt to settle the U.S.

financial markets and stimulate economic recovery. The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act

of 2008 (EESA) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) both

contained sweeping measures aimed at stimulating many areas of the economy. The solutions

that focus on the financing and development of renewable energy projects are addressed below.

5.1 Effectiveness of EESA Unclear

EESA was designed to inject capital into banks, provide liquidity to the credit markets, and

restore confidence in the U.S. financial system. Several renewable energy-specific provisions

were included in the legislation: notably an eight-year solar ITC extension, a one-year wind PTC

extension,

7

and allowance of the ITC to count against a project owner’s alternative minimum tax.

A detailed description of the renewable energy provisions can be found in the Appendix.

Interviewees agreed that it is still too early to tell whether the measures in EESA will stimulate

the tax equity and debt markets, and encourage renewable energy investment again. The long-

term ITC extension is considered beneficial because it eventually will allow for long-term capital

planning once the debt and tax equity markets stabilize. Interviewees expressed concerns that, in

7

For non-wind technologies, the PTC was extended for two years.

• “LIBOR is broken, the new LIBOR is 150 basis points above LIBOR.”

• Before the financial crisis:

“Money was practically free…”

“It was the best time to be a borrower in the energy industry since the

independent power producer (IPP) boom of the early ’90s.”

• “Financing people have short memories…debt will flow again, eventually.”

8

the immediate future, effects of a potentially deep and far-reaching recession may temporarily

outweigh the benefits of the targeted renewable energy provisions included in EESA.

5.2 Effectiveness of ARRA’s Renewable Energy Provisions Yet to Be Determined

In February 2009, the U.S. federal government enacted ARRA, a nearly $800 billion economic

stimulus bill that was composed of spending and tax cuts. Under the act, the energy efficiency

and renewable energy sectors will receive more than $71 billion in newly appropriated funding,

plus another $20 billion in additional tax credit incentives (Weiss 2009). Selected renewable tax-

based provisions of the bill include:

• Extending the PTC expiration by an additional three years over the EESA extensions (to

2012 for wind and 2013 for other technologies).

• Allowing the PTC to be converted into a 30% ITC.

• Allowing federal cash grants to be taken in lieu of the ITC, administered by the Department

of the Treasury.

• Removing subsidized energy financing

8

• Extending the 50% first-year MACRS depreciation (“bonus accelerated depreciation”) to

year-end 2009.

restrictions of the ITC.

• Funding an additional $6 billion in loan guarantees for renewable energy technologies,

including commercially available technology projects (not previously eligible), emerging

technology projects, transmission (not previously eligible), and manufacturing. This

provision, administered by the Department of Energy, is expected to leverage $60 billion to

$100 billion in projects.

• Providing an additional $1.6 billion allocation for clean renewable energy bonds (CREBs) to

municipalities, municipal utilities, and rural cooperatives ($2.4 billion total, including EESA

2008).

ARRA attempts to addresses the shortage of tax equity investment by having the Department of

the Treasury provide cash-based grants for property placed in service in 2009-2010, instead of

tax credits (which do not function well if investors are not profitable). The cash-based grants

would be a stop-gap measure until tax equity investment returns to the market—most likely with

increased profitability and a healthier economy in a few years. Only tax-paying commercial

entities would be able to apply for this cash-based grant, which excludes government agencies

and certain other entities that do not pay taxes. And because the “passive-loss and at-risk rules”

persist, it is still challenging for high net-worth individuals with large tax appetites to take the

PTC and ITC directly on their personal income taxes.

While the cash grants should help with the ITC and PTC (by way of the option to elect the ITC),

traditional tax equity liability is still needed to benefit from MACRS accelerated depreciation.

The option of choosing the ITC instead of the PTC would shorten the length of time needed to

fully secure the benefits of either the tax credit or the grant from 10-11 years (PTC benefit) to six

years (MACRS). Conversely, other factors may favor the election of the PTC over the ITC, but

would need to be considered on an individual project basis (Bolinger et al. 2009).

8

Subsidized energy financing (SEF) refers to federal, state, or local governmental program assistance (e.g., zero-

interest loans). Previously, the portion of the project financed using SEF was not eligible to use the ITC.

9

ARRA’s three-year PTC extension provides longer-term certainty of the tax incentive than the

previous one- to two-year extensions allowed—a provision that should assist renewable project

capital planning. However, this PTC extension is shorter than the eight-year ITC extension

established in EESA. In addition, the loan guarantees and new allocations for clean renewable

energy bonds

9

as well as qualified energy conservation bonds should help funnel investment into

the industry, separate from the PTC and ITC mechanisms.

5.3 Measures to Monitor the Impact of Federal Legislation on RE Project

Development

It is too early to assess definitively the degree to which the enactment of EESA and ARRA may

serve the renewable energy industry from today’s market conditions. Given the amount of money

likely to flood the renewable energy markets, the impact is likely to be pronounced—the

question is when it will occur.

As the programs are implemented, a few indicators could help gauge the effectiveness of the

renewable energy provisions. One important factor is the timing of implementation of federal

legislation, or how long it takes to provide clarity to investors and the market. In most parts of

the United States, there is a clearly defined construction season—and if it is missed in 2009, then

projects cannot be completed until 2010. It will be important to see whether construction has

enough time for completion in 2009 after guidance and application documents are issued. If

some projects miss the construction window, effectiveness may depend on whether the market is

able to execute additional construction in 2010.

The cash grant and loan guarantee programs are expected to provide the most-needed benefit to

the market as other sources of equity and debt investment are constrained. Thus, expediency of

program implementation and administration are imperative to providing meaningful and timely

assistance. To be effective, program details and guidance must be understandably defined to

satisfy all contractual or interested parties. These federal incentives should also provide long-

term certainty to the market, specifically to facilitate capital planning and investment in future

development.

In tracking the legislation, it will also be useful to monitor early signs of economic recovery or a

stabilization of the financial markets. Such signals could precede a rebound and resurgence of

renewable energy project development and a stabilization of the industry. Lastly, the emergence

of new or returning investors through these programs is critical to expanding the limited

investment pool and is addressed in Section 6.

9

Clean renewable energy bonds, or CREBS, are used as an RE project financing source for municipalities, rural

electric cooperatives, and municipal utilities.

10

6 New Investor Opportunities

Traditionally, renewable energy projects have relied heavily on tax equity capital investment

from the financial sector, which limited investment. As a result of the financial crisis and

subsequent federal legislation, developers may need to expand their sources of capital

investment.

6.1 New Tax Equity Investors Anticipated

The contraction of traditional tax equity investors and expected increase in IRR could open the

door to new investors (outside of financial firms) for renewable energy projects. This is

especially true with broader eligibility of the ITC under EESA. New or reemerging tax equity

investors will be necessary for continued renewable energy project development; this may be

particularly true after the expiration of the ARRA cash grant. The sample of experts interviewed

expect that there will be an increased interest in projects being financed by untraditional, yet

profitable companies that can take direct advantage of the PTC and ITC and do not require a

third party. Possible new entrants as renewable energy tax equity investors could eventually

come from a wide range of sectors including oil and gas, high-tech, and industrial companies.

Interviewees also mentioned that more tax equity could enter into the market if unconventional

investors such as high net-worth individuals could take the tax credits (see Section 3.2)

(Chadbourne & Parke 2009a). Federal legislation has not addressed the barriers that currently

impede these investors.

6.2 Utilities Increasingly Interested in Project Ownership and Tax Equity

Investments

Utilities were also widely mentioned by interviewees as possible tax equity investors who would

have sufficient profitability levels to directly use tax credit investments (now and particularly in

the long term). Increased utility involvement could simplify financing arrangements, replacing

complex partnerships. Utilities can take the PTC for wind and other renewables (Cory et al.

2008, Mann 2008) so they may decide to own the renewable projects themselves. Also, utilities

can now take the ITC directly, so they might structure programs to own distributed solar systems

on their own land—or on their customer sites—particularly in load-constrained areas. Five

utilities have already announced such plans including Duke Energy in North Carolina; Public

Service Electric and Gas Co. in New Jersey; and three California utilities: Pacific Gas and

Electric, San Diego Gas and Electric, and Southern California Edison (Baker 2009).

11

Possibilities of new investors

Responses and highlights from expert interviews:

7 Factors Influencing Future RE Project Development and

Financing

Renewable energy generation in the United States will be influenced by a number of factors in

the near term. Among other considerations, the simultaneous impact of the financial crisis, U.S.

federal legislation, new or re-emerging investors, as well as anticipated economic recovery will

determine future renewable energy generation growth. Figure 2 depicts several projected growth

scenarios, an estimate of the impact of the financial crisis, and a sequence of key market events

for non-hydro renewable energy generation.

The low-growth scenario is the Energy Information Administration’s (EIA’s) projection of

renewable energy generation without the passage of ARRA (EIA 2009a). The next highest

growth scenario is EIA’s revised projection to account for renewable energy provisions

contained within ARRA (EIA 2009b). By 2012, the revised scenario projects nearly 150 TWh of

renewable energy generation in excess of the original projection. The high growth scenario is a

post-ARRA, NREL estimate of renewable energy generation, indicating the largest increase

among the three scenarios (Sullivan et al. 2009). Note that all scenarios indicate a drop in

generation growth in 2013. This slowdown reflects the scheduled expiration of the PTC for wind

at year-end 2012.

A sequence of market events influencing renewable energy development is also depicted

chronologically in Figure 2. Along the top of the figure is a timeline of market events. Each

section of the timeline is depicted by an arrow that is coincident to a particular time period in

which that event is expected to have its greatest impact on project development. Realistically,

however, the true impact of each market event is extended—thus commencing before and

continuing after the period in which it is sequentially aligned.

Lastly, an estimate of the duration of the financial crisis’s impact on renewable energy project

development is shown beginning at the height of the crisis in October 2008. In the wake of the

• “Utilities can’t afford not to participate.”

• “Technology and telecommunication companies are possible new

investors…Companies such as Samsung, LG Electronics, Toshiba, and Siemens may

step in through acquisitions”

• “Oil industry and railroad companies could become interested.”

• “The industry cannot quickly replace the likes of JP Morgan, Wells Fargo, and

CitiBank. Their experience investing in renewables will take time to redevelop.”

• “Large owners of real estate could deploy many relatively small systems across their

properties; they will likely enjoy economies of scale for pricing.”

• “Hotels, insurance companies, and banks could enter the RE investment space. If

returns go up enough, we could also see non-electric utilities, Microsoft, Google,

Nike, Northern Trust, etc.”

12

financial crisis, renewable energy project development has continued. For instance, more than

2,800 MW of wind capacity was installed in the first quarter of 2009 (AWEA 2009b). However,

much of the financing for these projects was secured prior to the height of the financial crisis,

and commitments were honored by project investors. Accordingly, it is possible that the most

acute impact of the financial crisis on renewable energy project development could be

experienced in the second half of 2009. This is the period after pre-financial crisis commitments

are completed, but before the impacts of the ARRA provisions or broader economic recovery

take place. In Figure 2 this is shown as the range from the height of the financial crisis to year-

end 2009.

Figure 2. Impacts of the financial crisis and federal legislation on

renewable energy project development

13

8 Conclusions

Renewable energy project financing is being reshaped by several extraordinary market

conditions. The two primary sources of project capital investment—tax equity investment and

debt—are currently limited and are, therefore, a constraint on new project development.

The market for tax equity investment is sizably smaller than recent boom years. As of the first

half of 2009, the amount of tax equity investment will be insufficient for near-term renewable

energy project development. Utilities and other new investors may increasingly invest in

renewable energy projects as equity returns are expected to increase. New investment is expected

to be supported by the broader eligibility for tax equity investment under the Emergency

Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, and the substitution of Department of Treasury cash grants

for tax credits under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

Meanwhile, little debt is currently available as a result of the financial crisis and the tightening of

credit worldwide. As renewable energy project lenders are conserving capital, borrowing costs

are expected to increase. However, as of this writing, interest rates for debt on renewable energy

projects are unclear because little, if any, debt is being financed in the commercial market. The

loan guarantees offered in ARRA and administered by the Department of Energy, may increase

the availability of debt to finance renewable energy projects.

Critically, these new programs are hoped to signal a long-term commitment by the U.S. federal

government in support of renewable energy. Long-term policy and program certainty is critical

to capital planning and investment in project development. This commitment will help achieve

consistent and sustained growth of renewable energy and assist in curbing the boom-and-bust

cycle of project development that has plagued the industry.

The crippling financial and economic circumstances will also likely lead to a renewable energy

industry shakeout. Industry consolidation is widely expected with the strongest capitalized firms

or new market entrants acquiring distressed or thinly capitalized competitors. If the economy

recovers in a timely fashion, best practices should prevail and the strongest firms will rise to the

top. It is hoped that the industry as a whole will emerge stronger with a better understanding of

the risks that it faces.

Overall, it appears that the financial crisis will impact U.S. renewable energy project

development most acutely in the near term; however, major changes introduced by federal

legislation are expected to stimulate growth in the months and years ahead. The nation is anxious

to see how recent federal policies will help the U.S. economy recover. As the financing

provisions from EESA and ARRA are fully implemented, experts are optimistic that the rate of

renewable energy project development will accelerate.

14

References

ACORE (2008). “Renewable Energy Finance - Hedging and Risk Management During Financial

Markets in Turmoil,” American Council On Renewable Energy (ACORE) webinar,

moderated by Roger Stark, K&L Gates; and John Lorentzen, Winston & Strawn,

November 19, 2008.

ARRA (2009). American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), H.R. 1105, 111

th

Congress, first session (2009), at

http://appropriations.house.gov/pdf/2009_Con_Bill_Introductory.pdf

AWEA (2009a). “WIND ENERGY GROWS BY RECORD 8,300 MW IN 2008,” American

Wind Energy Association (AWEA) news release, January 27, 2009, at

http://www.awea.org/newsroom/releases/wind_energy_growth2008_27Jan09.html

AWEA (2009b). “U.S. Wind Energy Industry Installs Over 2,800 MW In First Quarter,”

American Wind Energy Association news release, April 28, 2009, at

http://www.awea.org/newsroom/releases/AWEA_first_quarter_market_report_042809.

html

Baker, D. R. (2009). “PG&E bankrolling solar plants” San Francisco Chronicle, February 25,

2009, accessed at

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-

bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2009/02/24/MNB1164F0P.DTL

Bolinger, M.; Wiser, R.; Cory, K.; James, T. (2009). “PTC, ITC, or Cash Grant? An Analysis of

the Choice Facing Renewable Power Projects in the United States,” Lawrence Berkeley

National Laboratory and National Renewable Energy Laboratory technical report LBNL-

1642E and NREL/TP-6A2-45359, March 2009, at

http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy09osti/45359.pdf

Chadbourne & Parke (2009a). “A Look Forward Into 2009,” Project Finance NewsWire, a

discussion in mid-December with four Washington lobbyists, moderated by Keith Martin,

Chadbourne & Parke, p. 3, released in January 2009, at

http://www.chadbourne.com/files/Publication/810dde60-3c78-4a9a-9c5d-

a5fae8014b4f/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/51fc06c5-1407-48ac-9dff-

a605de0f58e1/pfn0109.pdf

Chadbourne & Parke (2009b). “Trends in Tax Equity for Renewable Energy,” Project Finance

NewsWire, Infocast webinar with two equity arrangers and four potential renewable

energy investors, moderated by Keith Martin, Chadbourne and Parke, pp. 27-34 on

December 16, released in January 2009, at

http://www.chadbourne.com/files/Publication/810dde60-3c78-4a9a-9c5d-

a5fae8014b4f/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/51fc06c5-1407-48ac-9dff-

a605de0f58e1/pfn0109.pdf

15

Cory, K.; Coggeshall, C.; Coughlin, J.; Kreycik, C. (2009). “Solar Photovoltaic Financing:

Deployment by Federal Government Agencies,” National Renewable Energy Laboratory

– forthcoming technical report that will be available in summer 2009, at

http://www.nrel.gov/publications/

Cory, K.; Coughlin, J.; Jenkin, T.; Pater, J.; Swezey, B. (2008). “Innovations in Wind and Solar

PV Financing,” National Renewable Energy Laboratory Technical Report NREL/TP-

670-42919, February 2008, at http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy08osti/42919.pdf

DOE (2009). “DOE Secretary Chu Announces Changes to Expedite Economic Recovery

Funding: Restructuring will lead to new investments in energy projects within months,”

U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) news release, February 19, 2009, accessed at

http://www.energy.gov/news2009/6934.htm

DOE (2008). “Annual Report on U.S. Wind Power Installation, Cost, and Performance Trends:

2007,” U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy

– Wind Energy Technology Program, May 2008, at

http://www1.eere.energy.gov/windandhydro/pdfs/43025.pdf

Doyle, J. (2009). “The Asset Finance Drought: Is There An Opening For Specialist Debt

Funds?” New Energy Finance, May 13, 2009

EIA (2009a). “Annual Energy Outlook 2009 with Projections to 2030, Updated Annual Energy

Outlook 2009 Reference Case without ARRA,” U.S. Department of Energy, Energy

Information Administration (EIA) Web site, accessed June 2009 at

http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/servicerpt/stimulus/excel/aeonostimtab_16.xls

EIA (2009b). “Annual Energy Outlook 2009 with Projections to 2030, Updated Annual Energy

Outlook 2009 Reference Case with ARRA,” U.S. Department of Energy, Energy

Information Administration website, accessed June 2009 at.

http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/servicerpt/stimulus/excel/aeostimtab_16.xls

EESA (2008). Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (EESA), H.R. 1424, 110

th

Congress, second session (2008), at

http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=h110-1424

Harper, J.; Karcher, M.; Bolinger, M. (2007). “Wind Project Financing Structures: A Review &

Comparative Analysis,” Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory technical report LBNL-

63434, September 2007, at http://eetd.lbl.gov/ea/ems/reports/63434.pdf

Hudson (2009). “Additional Observations About the Impact of Stimulus Action on Energy and

Environmental Policy” Hudson Clean Energy Partners, L.P, accessed June 2009 at

http://www.seia.org/galleries/pdf/Need_for_Refundability.pdf

16

Investopedia (2009). “London Interbank Offered Rate – LIBOR. Investopedia explains London

Interbank Offered Rate - LIBOR,” Investopedia: A Forbes Digital Company, accessed

February 2009, at http://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/libor.asp

Mann, L. (2008). “IRS Reinterpretation Will Benefit Utilities RE Investments,” North American

Windpower, September 2008, pp. 72-73.

Prometheus (2007). “U.S. Solar Industry: Year in Review 2007,” Prometheus Institute and the

Solar Energy Industries Association, accessed December 2008 at

http://www.seia.org/galleries/pdf/Year_in_Review_2007_sm.pdf

SEIA (2009). “US Solar Industry Year in Review 2008,” Solar Energy Industries Association

(SEIA), accessed June 2008 at

http://seia.org/galleries/pdf/2008_Year_in_Review-small.pdf

Sullivan, P.; Logan, J.; Bird, L.; Short, W. (2009). “Comparative Analysis of Three Proposed

Renewable Electricity Standards,” National Renewable Energy Laboratory technical

report NREL/TP-6A2-45877, May 2009, at http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy09osti/45877.pdf

Weiss, D.J.; Kougentakis, A. (2009). “Recovery Plan Captures the Energy Opportunity,” Center

for American Progress, February 13, 2009, at

http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2009/02/recovery_plan_captures.html

17

Appendix. Select Federal Legislation in 2008 and 2009

Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008

In an effort to restore confidence and functionality of the financial markets, the U.S. federal

government passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (EESA). While its main

goal was to try to support investors and lenders, EESA included several renewable energy

provisions that applied to a number of renewable energy technologies and varied in both scope

and length. The key provisions are identified below (EESA 2008).

• Extension of the production tax credit by one year to the placed-in-service date of

December 31, 2009, for wind; and December 31, 2010, for biomass, marine, and certain

other renewable sources.

• Extension of the investment tax credit at a rate of 30% by eight years for solar and

qualified fuel cells through 2016, and 10% for microturbines. The $2,000 ITC cap for

residential solar was lifted (so they can now take the full 30%). EESA also added two

new technologies to the eligibility list: small wind (<100 kW) and geothermal heat

pumps. EESA established a $4,000 cap for each small wind project. At the end of the

eight-year period, the 30% tax rate will revert back to 10% and the microturbines tax

credit will expire.

• Allowance of the investment tax credit to count against the alternative minimum tax,

which opens up the tax credit to many more investors.

• Allowance for utilities to take the investment tax credit.

• Authorization of $800 million to fund new clean renewable energy bonds for

municipalities, rural electric cooperatives, and municipal utilities, across various

technologies.

• Authorization of $800 million to fund qualified energy conservation bonds across various

technologies.

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

On February 17, 2009, President Obama signed into law the American Recovery and

Reinvestment Act of 2009, which included several renewables-specific provisions, shown in

Table A1 (ARRA 2009).

18

Table A1. Select Tax Provisions Addressing EERE Sectors

Provision

Details from The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

Extends the PTC

In-Service Deadline

Extends the PTC through 2012 for wind, and through 2013 for closed- and open-loop

biomass, geothermal, landfill gas, municipal solid waste, qualified hydroelectric, and marine

and hydrokinetic facilities. In 2008, the inflated PTC stood at $21/MWh for wind,

geothermal, and closed-loop biomass; and $10/MWh for other eligible technologies.

Provides Option to

Elect the ITC in

Lieu of the PTC

10

Allows PTC-qualified facilities installed in 2009-13 (2009-12 in the case of wind) to elect a

30% ITC in lieu of the PTC. If the ITC is chosen, the election is irrevocable and requires the

depreciable basis of the property to be reduced by one-half the amount of the ITC.

Provides Option to

Elect a Cash Grant

in Lieu of the ITC

Creates a new program (administered by the Treasury) to provide grants covering up to

30% of the cost basis of qualified renewable energy projects that are placed in service in

2009-10, or that commence construction during 2009-10 and are placed in service prior to

2013 for wind, 2017 for solar, and 2014 for other qualified technologies. Applications must

be submitted by October 1, 2011, and the Treasury is required to make payments within 60

days after an application is received or the project is placed in service, whichever is later.

The grant is excluded from gross income, and the depreciable basis of the property must be

reduced by one-half of the grant amount.

Removes ITC

Subsidized Energy

Financing Penalty

Allows projects that elect the ITC to also use “subsidized energy financing” (e.g., tax-exempt

bonds or low-interest loan programs) without suffering a corresponding tax credit basis

reduction. This provision also applies to the new grant option described above.

Extends 50%

Bonus Depreciation

Extends 50% bonus depreciation (i.e., the ability to write off 50% of the depreciable basis in

the first year, with the remaining basis depreciated as normal according to the applicable

schedules) to qualified renewable energy projects acquired and placed in service in 2009.

Extends Loss

Carryback Period

Extends the carryback of net operating losses from two to five years for all small businesses

(i.e., those with average annual gross receipts of $15 million or less over the most recent

three-year period). This carryback extension can only be applied to a single tax year, which

must either begin or end in 2008.

Removes ITC

Dollar Caps

Eliminates the maximum dollar caps on residential small wind, solar hot water, and

geothermal heat pump ITCs (so now at the full 30%). Also eliminates the dollar cap on the

commercial small wind 30% ITC. Credits may be claimed against the AMT.

Expands Loan

Guarantee Program

Expands existing loan guarantee program to cover commercial (rather than just “innovative

noncommercial”) projects. Appropriates $6 billion to reduce or eliminate the cost of providing

the guarantee; this amount could support $60-$120 billion in loans, depending on the risk

profiles of the underlying projects.

Clean Renewable

Energy Bonds

Adds $1.6 billion in new CREBs for eligible technologies owned by governmental or tribal

entities, as well as municipal utilities and cooperatives. With $800 million of new CREB

funding previously added in October 2008, combined new CREB funding totals $2.4 billion.

New ITC for

Manufacturers

Establishes a 30% ITC for the establishment, expansion, or retooling of manufacturing

facilities producing clean energy and related technologies. Projects must be certified by the

Treasury in consultation with DOE.

Energy

Conservation

Bonds

Adds $2.4 billion to state, local, and tribal programs to finance clean energy projects. This is

a four-fold increase from the previous maximum level of available funding.

Residential

Efficiency

Upgrades

Credits

Increases the credit to 30% (a three-fold increase) for 2009 and 2010 with a $1,500 cap,

and removes limits on certain properties and other subsidized energy financing.

PHEV Consumer

Tax Credit

Modifies the tax credit for consumers of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) to a

maximum of $7,500 and eliminates some previous restrictions to spur the development of

PHEV markets.

Alternative Fuel

Tax Credits for

Infrastructure

Increases refueling property tax credits for 2009 and 2010:

• Businesses – Increases from 30% (capped at $30,000) to 50% (capped at $50,000).

• Individuals – Increases from 30% (capped at $1,000) to 50% (capped at $2,000).

•

Hydrogen refueling pumps remain at 30% with a cap increase to $200,000.

Created by Ted James and Jeffrey Logan, NREL, in March 2009; includes input from Mark Bolinger and

Ryan Wiser, LBNL.

10

For analysis on this new option, see Bolinger et al. 2009.

F1147-E(09/2007)

REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE

Form Approved

OMB No. 0704-0188

The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources,

gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this bur

den estimate or any other aspect of this

collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Executive Services and Communications Directorate (0704-

0188). Respondents

should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it do

es not display a

currently valid OMB control number.

PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ORGANIZATION.

1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY)

July 2009

2. REPORT TYPE

Technical Report

3. DATES COVERED (From - To)

4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE

Renewable Energy Project Financing: Impacts of the Financial

Crisis and Federal Legislation

5a. CONTRACT NUMBER

DE-AC36-99-GO10337

5b. GRANT NUMBER

5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER

6. AUTHOR(S)

P. Schwabe, K. Cory, and J. Newcomb

5d. PROJECT NUMBER

NREL/TP-6A2-44930

5e. TASK NUMBER

SAO7.9B30

5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER

7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES)

National Renewable Energy Laboratory

1617 Cole Blvd.

Golden, CO 80401-3393

8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION

REPORT NUMBER

NREL/TP-6A2-44930

9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES)

10. SPONSOR/MONITOR'S ACRONYM(S)

NREL

11. SPONSORING/MONITORING

AGENCY REPORT NUMBER

12. DISTRIBUTION AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

National Technical Information Service

U.S. Department of Commerce

5285 Port Royal Road

Springfield, VA 22161

13. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES

14. ABSTRACT (Maximum 200 Words)

Extraordinary financial market conditions have disrupted the flows of equity and debt investment into U.S. renewable

energy (RE) projects since the fourth quarter of 2008. The pace and structure of renewable energy project finance has

been reshaped by a combination of forces, including the financial crisis, global economic recession, and major changes

in federal legislation affecting renewable energy finance. This report explores the impacts of these key market events on

renewable energy project financing and development.

15. SUBJECT TERMS

NREL; renewable energy; RE; financial crisis; production tax credit; PTC; American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

of 2009; ARRA; Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008; EESA; renewable portfolio standard; RPS;

renewable energy certificate; REC; renewable energy markets; Paul Schwabe; Karlynn Cory

16. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF:

17. LIMITATION

OF ABSTRACT

UL

18. NUMBER

OF PAGES

19a. NAME OF RESPONSIBLE PERSON

a. REPORT

Unclassified

b. ABSTRACT

Unclassified

c. THIS PAGE

Unclassified

19b. TELEPHONE NUMBER (

Include area code)

Standard Form 298 (Rev. 8/98)

Prescribed by ANSI Std. Z39.18