DOCUMENT RESUME

ED 415 993

PS 026 177

AUTHOR

Brown, Brett V.

TITLE

Family Functioning and Adolescent Behavior Problems: An

Analysis of the National Survey of Families and Households.

INSTITUTION

Child Trends, Inc., Washington, DC.

SPONS AGENCY

Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC.

PUB DATE

1993-07-00

NOTE

59p.

CONTRACT

DHHS-100-92-0015

PUB TYPE

Reports

Research (143)

EDRS PRICE

MF01/PC03 Plus Postage.

DESCRIPTORS

*Adolescents; *Behavior Problems; *Child Behavior;

Comparative Analysis; Definitions; Family Environment;

*Family Influence; Family Structure; Multivariate Analysis;

National Surveys; Nuclear Family; One Parent Family;

*Predictor Variables; Sex Differences; Stepfamily; Test

Reliability

IDENTIFIERS

Family Functioning; National Survey of Families and

Households

ABSTRACT

This study used data from the National Survey of Families

and Households (NSFH) to explore the relationship between family functioning

and adolescent behavior problems. The data covered five family types:

married, two-biological parent families (TP); stepfamilies;

divorced/separated female-headed families (DSF); never married female-headed

families (NM); and single male headed families. The total sample included

over 2,300 households with adolescents between 12 and 18 years. Data were

collected through in-person surveys and self-administered questionnaires

completed by respondent and spouse. Findings indicated that there was

significant variation across family types in the ways in which family

functioning measures related to adolescent behavior problems, with measures

operating poorly for NM families. The TP families generally scored higher

than other types on family strength measures. One-parent families attempted

to compensate by reaching out to extended kin, friends, and neighbors,

although these activities were not related to reduced adolescent behavior

problems. Internal measures of family functioning were more important than

external measures of family functioning in predicting adolescent problem

behaviors. Marital conflict and depression were very powerful predictors of

adolescent behavior problems in two-biological parent families, and marital

conflict was a powerful predictor in step-families. Family functioning

measures were about equal in predictive power to sociodemographic measures in

predicting two of the three behavior problem measures. There were clear

differences in the level of reporting by parent. (Seven tables detail

findings. An appendix provides definitions of measures. Contains 15

references.)

(KB)

********************************************************************************

*

Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made

*

*

from the original document.

*

********************************************************************************

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

Office of Educational Research and Improvement

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION

CENTER (ERIC)

This document has been reproduced as

received from the person or organization

originating it.

Minor changes have been made to

improve reproduction quality.

Points of view or opinions stated in this

document do not necessarily represent

official OERI position or policy.

FAMILY FUNCTIONING AND ADOLESCENT BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS: AN

ANALYSIS OF THE NATIONAL SURVEY OF FAMILIES AND HOUSEHOLDS

July 1993

by

Brett V. Brown, Ph.Z.

Research Associate

Child Trends, Inc.

2100 M. Street, N.W.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND

DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL

HAS BEEN GRANTED BY

CoorlA

A.

erm

s

Washington, D.C. 20037

TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)

Prepared under DHHS contract 100-92-0015,

Delivery Order 02

The author gratefully acknowledges the programming assistance

of Charles Halla and Thomas Stief, the typing assistance of

Fanette Jones, and the helpful comments of Drs. Donna Ruane

Morrison and Kristin Moore.

2

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

INTRODUCTION

A growing body of literature is exploring the ways in which both positive and negative

family functioning affect the health and well-being of family members, particularly children.

With rare exceptions, such research has been based on small, narrow and unrepresentative

samples of families (for exceptions, see Furstenburg et. al. 1983, Zill et al. 1991, Zill et. al.

1993. Buchannon, Maccoby and Dornbusch 1992).

In this paper. we use the National Survey of Families and Households, a recent large

random sample of U.S. families containing a wealth of family process and social support

measures, to go beyond economic and demographic measures and systematically explore the

relationship between family functioning and adolescent behavior problems.

QUESTIONS PURSUED IN THE ANALYSIS

The primary focus of the analysis will be on the relationship between family function

and family type. Within this area, we will focus on the following questions.

To what extent are family functioning measures equally appropriate for all family

types?

There has been a great deal of criticism within the child development

literature that existing measures of family process and child behaviors may suffer

from significant race/ethnicity and class biases. Groups may face distinct challenges

from the environment, and draw on distinct cultural traditions which call for different

family functioning strategies to maximize the well-being of children. This may result

in significant variations in both the reliability and validity of such measures across

groups. This critique is easily extended to the social dimension of family type. While

different family types may not possess distinct cultural traditions, they do face distinct

internal and external stressors which may produce differences in the reliability and

validity and impact of family functioning measures.

1

How do the levels and mix of positive and negative family functioning characteristics

differ by family type? Different types of families differ both in the stresses they

experience which can produce poor family functioning, and in the resources available

to them to build family strengths. Single parent families of all sorts have one less

parent to contribute to the raising of children and the financial support of the family.

Step-families may have to deal with a third parent, the ex-spouse, and face unique

challenges in defining the relationship between step-parents and children. These and

other factors may be expected to produce both different levels of functioning, and

different strategies to build family strength.

How might the effects of these family functioning characteristics on adolescent

behavior problems differ by family type?

The relationship between a family

functioning measure and an adolescent behavior measure may differ across family

types for two reasons. First, the particular family functioning measure may be

measuring different things for different family types (a validity issue). Second, it is

likely that the origins of adolescent behavior problems vary by family type. For

example, both a divorce and the introduction of a step-parent, defining characteristics

of two common family types, may themselves be unique sources of behavior

problems.

In addition to family type issues, we will explore the following broad issues:

How important are family functioning measures in explaining adolescent behavior

problems, relative to conventional economic and sociodemographic measures?

Presently, family functioning measures are relatively rare and not always of the best

quality in existing large scale surveys. If their inclusion adds substantially to our

understanding of the behavior of family members, they should be further developed

and included in more large federal surveys. The analyses for this project will not be

definitive regarding this question. but will add important new information.

What dimensions of family functioning are the most important in determining

adolescent behavior?

For the analysis, family functioning measures have been

divided into internal and external measures. Internal measures refer to the processes

and value orientations which operate within the immediate family. External measures

indicate the relationship of the family to the outside world including extended kin,

friends and neighbors, and organizations within the community. The ecological model

described by Bronfenbrenner suggests that both will have important impacts on child

development (Bronfenbrenner 1979). In the analysis, we will evaluate the relative

importance of these two types of measures and, within these types, the importance

of individual measures.

2

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

What is the relative importance of family dysfunction and positive family strengths

in determining adolescent behavior? The family strengths literature is founded on

the notion that it is just as important to identify positive family strengths as it is to

identify family dysfunction (Stinnett and DeFrian 1985).

Also, it is suggested that

distinct measures can and should be developed for each (Dunst and Trivette, 1992).

For the present analysis we examine two negative measures, family conflict and

parental depression. The remaining

family functioning

measures

are

operationalizations of constructs found in the family strengths literature (for a review

of this literature. see Krysan et. al., 1990).

Does it matter who you ask? In families with more than one parent, reports of

behavior problems and family strengths may vary by the gender of the parent, and

by whether the parent is the biological step-parent of the child. Both potential

sources of variation are explored in the analysis. These results may have important

implications for choice of respondent in future Federal surveys.

DATA

The data set for this analysis is the National Survey of Families and Households

(NSFH), a large representative sample of U.S. households taken in 1987. The total sample

size is 13.014, including over 2,300 households containing adolescents between the ages of

twelve and eighteen. In-person surveys were conducted with a randomly chosen adult within

the household (a parent in our sub-sample), and with self-administered questionnaires

completed by both respondent and spouse. The survey was designed to support a wide

variety of family-oriented research efforts. A five year follow-up survey has just been

completed, and will be available for analysis in January of 1994.

The NSFH has a number of characteristics which make it particularly valuable in

pursuing the research agenda outlined above. First, its large sample size allows us to

perform comparative analyses which include less common family types such as never

married female heads and single male heads. Second, it contains what is by large survey

3

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

standards a wealth of data from which a wide variety family functioning measures can be

produced.

The survey also has several limitations which should be noted. First, the data are

cross-sectional. which limits our ability to model the causal direction of the relationship

between family strength measures and adolescent behavior problems. This is an important

issue for analyses of adolescent behaviors, since adolescents are more likely than younger

children to have direct impacts on the functioning of the family (Hetherington, personal

communication).

Second. no information was gathered directly from the adolescent, a shortcoming that

has been corrected in the five year follow-up survey. A previous analysis has shown child

reports of some family functioning measures to be more closely related to adolescent

behavior than parent reports (Zill et. al.. 19911.

VARIABLES

Outcome Measures

We have constructed three outcome measures covering different aspects of

adolescent behavior problems. Taken together. they allow us to evaluate the impact of

family functioning measures across a broad spectrum of behaviors. The first measure,

Behavior Problems I.

is a seven-item scale composed of a subset of questions from the

Behavioral Problems Index (Zill. 1991). The

scale is comprised of everyday behaviors

associated with anti-social acting out. hyperactivity, and depression-withdrawal. The second

measure. Behavior Problems II. is a five-item scale composed of major events indicating

4

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

more serious problem behaviors and includes running away, school suspension, parent-

teacher conferences over behavioral problems in school, trouble with the police, and seeing

a psychologist or therapist. The third measure is a seven item scale that

reflects the degree

of conflict between parent and adolescent child in the following areas: dress, friends, staving

out late. helping around the house. money, school. and getting along with other family

members. For a detailed description of these and other measures used in the analysis, see

.- Appendix A.

Family Functioning Measures

As we noted above. measures of family functioning have been categorized as internal

or external for this analysis. Internal measures of family functioning include encouraging

independence. commitment to family, spending time together, marital conflict, and parental

depression. The first three constructs has been identified in the literature as measures of

positive family functioning, and the last two as dysfunctional for the developinent of

children.

The first two of these measures are abstract values measures reflecting degree of

commitment to marriage and children. and to encouraging independence in one's children.

The time together scale reflects the amount of time one spends with one's children eating

meals. playing, working on projects. having private talks. helping with reading or homework,

and engaging in leisur,.:- activities outside the home. The marital conflict scale is a seven item

cumuiative measure of the freauency of disagreement between spouses on the following

tonics: household tasks. money. spending time together. sex, the in-laws, the children, and

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

about having another child. The parental depression measure is a twelve item version of the

standard CES-D depression scale.

External measures of family functioning were chosen to reflect the availability of

social support networks (family, friends, and religious institutions), and parental involvement

with organizations which serve youth. We use five external measures of family functioning

in ail: two measures of relationships with extended kin (geographical and emotional

closeness), frequency of socializing with friends and neighbors, attending religious services,

and involvement in youth organizations (PTA. team sports, religious and community youth

2roucts). All are based on the activities of the parent(s), not the adolescent. Social support

measures were defined in terms of availability rather than actual support behaviors, since

actual support behaviors reflect need as well as actual available support.

It is hypothesized that all family functioning measures with the exception of marital

conflict and depression. will be negatively associated with adolescent behavior problems.

That is. higher scores on these measures should be associated with fewer behavioral

problems. We expect the opposite relation for the marital conflict and parental depression

measures.

Not all of the important constructs of family functioning could be operationalized

using this data set. Important constructs not operationaiized for this analysis include styles

of family communication and conflict resolution. adaptability, cohesion, and the expression

of appreciation among family members (see Krvsan et. ai. 1990 for a review of these and

other constructs). Consequently. the analysis is not a comprehensive examination of family

functioning measures in general. but oniy an exploration of representative constructs.

6

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

THE ANALYSIS PLAN

In our analyses, we begin by examining measurement reliability and raw correlations

between family functioning measures and outcome measures of adolescent behavior

problems. These are performed for the full sample, and separately by family type.

Comparisons are also made by sex of adult respondent and, in the case of step-families.

whether the parent was the biological or step parent. Next, we look at the mean values of

both functioning and outcome measures by family type, to see how the levels and mix of

family strengths and family difficulties differs across family types.

This is followed by a series of nested multivariate models for the entire sample which

allow us to explore important questions discussed above which are not directly related to

family type issues (e.g. the overall importance of family functioning measures, the relative

importance of internal versus external measures of functioning). Finally, we compare the

results of fully specified models (those with the full complement of measures explored in

these analyses) across family types.

The analyses focus on five family types:

married, two biological parent families:

step-families:

divorced/separated female headed families (DSF);

never married female headed families:

single male headed families.

BEST COPY

AVAILABLE

Due to small sample sizes, our analyses of the two least common family types, never

married female and single male headed families. must be limited to descriptive analysis.

Multivariate analyses are carried out for the remaining three family types.

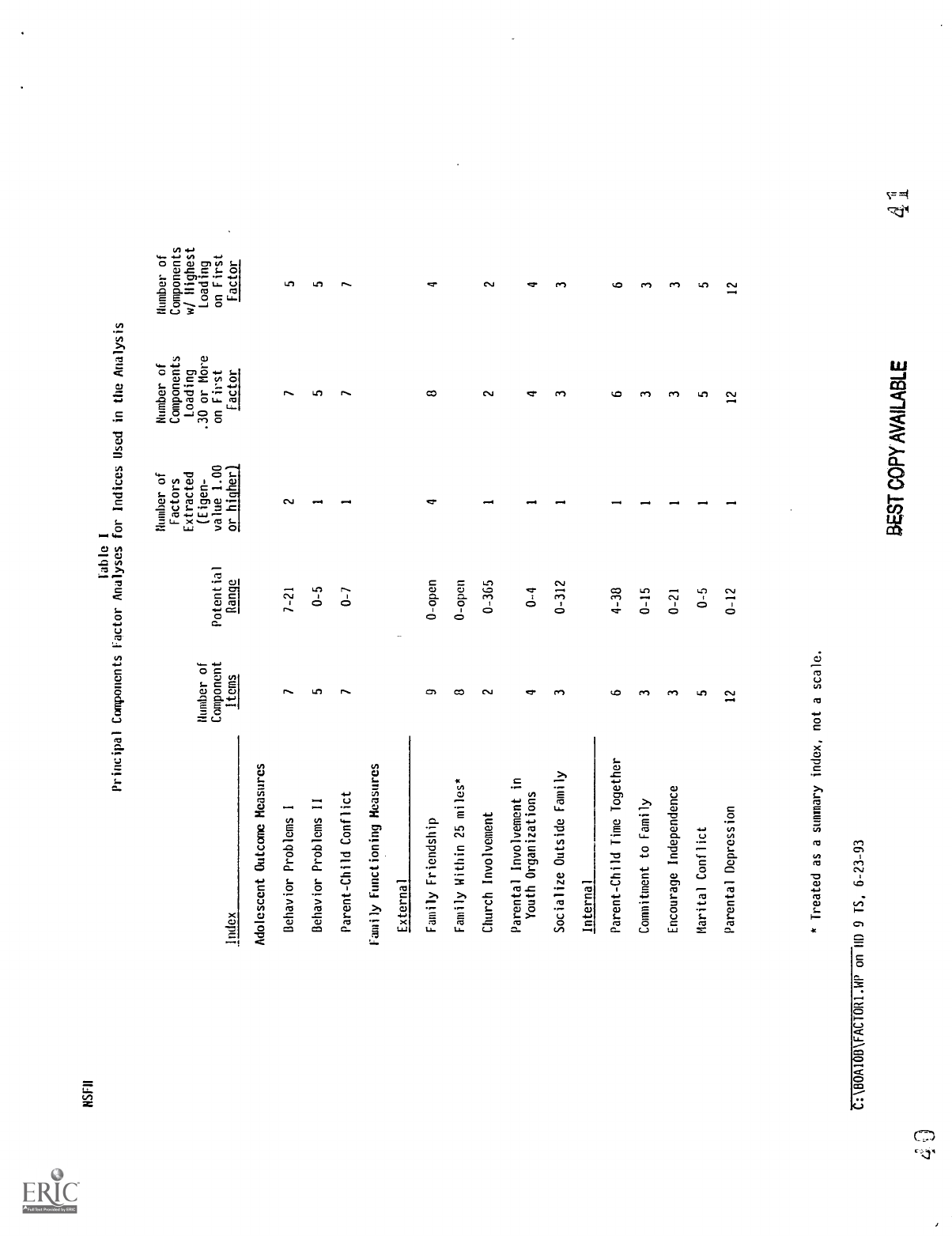

CREATING THE SCALES

All of the outcome and most of the family functioning measures that we are using

in the analyses are multi-item scales representing unitary constructs. In creating these scales,

factor analyses were performed to test whether the potential components of the scales all

loaded reasonably well on at least one factor. Through this method a final set of component

items were identified for each scale. The basic characteristics of each scale, including

number of items, value range, and results from the final set of factor analyses are displayed

in Table I.

SCALE RELIABILITY

One of the means of determining the quality of such scales is to assess their

reliability. Reliability measures the extent to which a scale can be expected to yield stable

results across repeated research trials or surveys. Measures with poor general reliability are

to be avoided or, if marginal, to be used with appropriate caution. When making statistical

comparisons across groups, it is important for purposes of interpretation that the level of

reliability be similar across those groups. For these analyses we are using Cronbach's alpha

as our reliability measure.

8

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

In assessing reliability we have concentrated on three issues:

What is the reliability of each measure within the general population?

To what extent does reliability differ by family type?

To what extent does reliability differ according to which parent is the respondent?

There are several reasons to expect that a measure's reliability may differ significantly

by family type. First. the scales may actually be measuring somewhat different things for

different types of families. For example, what it means to "encourage independence" among

one's children may be significantly different between single and two parent families. Where

a parent in the two-parent family may be thinking of independence in the abstract, a single

parent may be thinking more in terms of concrete activities which will help the family to

function on a day to day basis. Second, if the range of values of the measure is much

more

restricted for certain family types (for example if certain types of behavior are rare for

certain family types) it will tend to be a less reliable measure for that group even though

it is measuring the same construct.

An awareness of differences in the reliability of a measure across family types is very

important for proper interpretation of analysis results, since differences in the effects of the

measure may be due in part to differences in reliability rather than differences in the way

the construct actually operates within different types of families.

Measures may also differ in reliability according to the gender or the step versus

biological parent status of adult respondents within the same family types. Interactions

between parent and child differ significantly along both dimensions. Women and biological

9

BEST COPY

AVAILABLE

parents appear to have a greater awareness of what is going on in the lives of their

adolescent children. Such differences may result in lower measurement reliability from men

and step parents, whose lesser knowledge could introduce more error and less variation to

the measure.

Table II lists Cronbach's alpha scores of reliability for all of the scales used in our

analysis. Scores are shown for the full sample and for each of the five family types. Separate

scores are also shown for husbands and wives within two-biological parent families, and for

biological mothers and step-fathers within step families.

For the total sample, all of the adolescent outcome measures and all but two of the

family functioning measures have alphas in the .6 and .7 range or higher. This is a

satisfactory degree of reliability, particularly for survey data (see Nunnaly 1978). Many of

these measures are based on five or fewer items. The addition of appropriate additional

items could significantly enhance their reliability. Though such additional items do not exist

in this data base. the items in these scales could form the basis for even more reliable scales

in future surveys.

Two of the scales, "socializing outside of family" and "commitment to family", showed

marginal reliability scores of .44 and .54, respectively. While this suggests that they may not

adequately represent the constructs which they are meant to represent, we use them in

subsequent analyses given that we have no alternatives within the NSFH.

Across family types, there is surprisingly little variation in measurement reliability,

and generally favorable reliability levels were observed for each family type. For most

measures. variations in the alphas are no greater than .10. Several measures (parent-child

10

BEST COPY

AVAILABLE

212

conflict, parent-child time together, parental depression and marital conflict)

were

particularly consistent across family types. This indicates that it may not be necessary to

operationalize family functioning constructs differently for different family types, though of

course there are other reasons in addition to variation in reliability for doing so. In addition.

it means that the generally favorable reliability levels observed for the full sample also exist

for each family type.

There are, however, a few notable exceptions to this general pattern of consistency.

The reliability measure for "Behavior Problems II", the scale of

more serious

behavior problems, is considerably smaller for adolescents from two-biological parent

families than for teens from other family types (.48 versus .62 for the full sample).

It is not clear why this should be so. As we shall see in Table IV, such children show

a very low mean value for this measure compared to children from other family types

(.23 versus .54 or higher). The restricted range of values for children from

two-

biological parent families may account for its relatively poor performance.

The "family friendship" measure, a measure of emotional closeness of the parent with

adult extended kin, appears to be more reliable for two-biological parent families

than for other types of families (.66 versus .48-.56). Unlike most of the other family

types, most two-biological parent families have not had a major family disruption

which could alter relationships with extended family members and friends. In

addition. such families may be more traditional, placing greater emphasis

on family

relationships. Both factors may account in part for the greater reliability of the

measure for two-biological parent families.

The "socialize outside of family" measure, which showed the lowest overall reliability,

also showed great variation by family type (.32 to .51) with the highest reliability

again for two-biological parent families.

Within two-biological parent families, the reports of mothers and fathers have similar

reliability levels for both adolescent outcome and family functioning

measures across the

board. Within step-families, however, there are several large and puzzling differences in

reliability between step-fathers and biological mothers, all in favor of the step-father. For

11

BEST COPY AVAiLABLE

"Behavior Problems I", the outcome measure requiring the most knowledge of the daily life

of the child, step-fathers have alphas of .73 versus .58 for biological mothers. For

"family

friendship" and socialize outside of family", the spread is twice

as large. For all three

measures. step-fathers had the highest reliability score of the subgroups. While the

reason

for this is unclear, it may be that step-fathers more critically scrutinize the behavior

of their

non-biological offspring and develop more consistent and perhaps less flexible impressions.

CORRELATIONS BETWEEN MEASURES OF FAMILY FUNCTIONING

Some work within the family functioning literature

seems to suggest that family

functioning measures will be fairly highly correlated with

one another (Olson 1989, Stinnett

and DeFrain 1985). This also appeals to

common sense; families who operate well in one

dimension of family life will tend to operate well in other dimensions, while

the converse

might be true for dysfunctional families. On the other hand, within

the family therapy

literature there is a growing acknowledgement that

even troubled families often have

significant strengths to draw upon in addressing particular dysfunctions, indicating

a certain

independence across dimensions of family functioning. Some researchers

have gone so far

as to develop separate measures of strength and dysfunction for what

are usually treated

as single theoretical constructs (Dunst and Trivette, 1992).

An analysis of such correlations is. then, important in itself for the light it sheds

on

how dimensions of family functioning may affect each other. This

also has specific

implications for the analyses to follow. If the correlations

are low, or are high only for

selected pairs of measures, then it may be possible to

say something useful about the total

12

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

effect of a measure both directly, and indirectly through its relation with other dimensions

of family functioning.

If many of these measures are highly correlated, however, we are

limited to a discussion of direct effects. Alternatively, high correlation may indicate the

desirability of constructing and examining a single family strengths scale.

Table III shows a correlation matrix for all measures of family functioning used in

the analysis. All significant correlations are in the expected direction, with the exception of

the relationship between "family within 25 miles" and "marital conflict". This is nevertheless

an interesting exception, possibly indicating that family proximity can be something of a

mixed blessing.

The most notable finding in Table III is the surprisingly low correlation between

most measures. There is no correlation higher than .27, and most are in the single digits and

teens. Many of the measures are statistically independent from one another.

There are a number of interesting and noteworthy patterns of relationships. First,

there is the surprising lack of relationship between the negatively defined family functioning

measures (marital conflict and parental depression) and the remaining measures of family

strengths. They are reasonably well correlated with each other at .22.

But parental

depression is significantly correlated with only two of the remaining eight measures, and

those correlations are very modest (.05 or below). Marital conflict is correlated with more

measures, but again they are very modest, the highest being the correlation with

"commitment to family" at -.13. This seems to bear out the observation of those theorists

and family therapists who believe family dysfunctions and strengths often exist within the

13

BEST COPYAVAILASLE

same family. Moreover, they suggest that the several constructs are indeed tapping different

dimensions of family functioning.

Second, the 'family friendship" scale. representing the emotional closeness of the

parent to adult kin outside the household, is at least marginally significantly associated with

all of the other measures, though the level of correlation is often modest. It is, perhaps not

surprisingly, most strongly correlated with the measure for geographic proximity of extended

adult kin (the family within 25 miles measure) at .27, and the "commitment to family"

measure at .17.

This finding invites a number of possible interpretations. It may indicate

the central importance of the support (emotional, financial, and/or practical) offered by a

strong extended family system for the proper functioning within the immediate family.

Alternatively, it may reflect a learning effect. namely that adults who come from loving

families possess the skills and attitudes needed to create well-functioning families of their

own.

Third. there are many significant correlations between the more positively

constructed internal and the external measures of family functioning. External measures

particularly related to these internal measures include family friendship, involvement with

religious institutions, and parental involvement in youth organizations. These relations are

to some extent definitional. For example, the relatively high correlation between parent/child

time together and parental involvement in youth organizations is explained in part by the

fact that the former "internal" measure includes joint activities outside the home (though

the measures do not contain any overlapping items). Overall, however, this demonstrates

a clear relation between internal family functioning processes and persons and organizations

14

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

beyond the immediate family. What cannot be determined with this cross-sectional data is

causality, i.e.

whether well-functioning families are more integrated into the wider

community, or community involvement (including extended kin) promotes good family

functioning, or both. Further research using longitudinal data is needed to determine the

causal nature of this relationship.

LEVELS OF FAMILY FUNCTIONING AND ADOLESCENT BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS:

VARIATIONS BY FAMILY TYPE

In this section, we explore differences in the incidence of both behavior problems and

family functioning measures by family type. It has been amply demonstrated in previous

research that the incidence of child behavior problems differ by family type. Further, we are

interested to see how the availability and mix of family strengths, and the burden of family

dysfunctions (conflict, depression), differs by family type.

Adolescent Behavior Problems

Table IV contains the mean values for each adolescent outcome and family

functioning measure used in the analyses, for the full sample and separately by family type.

For all three measures of adolescent behavior problems there is clear variation by family

type. Children from two-biological parent families are reported to have the fewest problems

for all measures. The difference is particularly striking for "Behavior Problems II", where

the report of serious behavior problems is one half or less of what it is for other family

types. Across the remaining family types. it is important to note that children from step-

families are reported to exhibit problem behaviors at a rate closer to children from single

15

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

parent families than to those from two-biological parent families. In fact, when comparing

the reports of biological mothers from step-families with those from both types of female

headed families. levels of problem behavior are at least

as high for children from step-

families as for children from female-headed families.

It is interesting that step-fathers are considerably less likely than biological

mothers

in step-families to report serious adolescent behavior problems (Behavior

Problems II). This

may have to do with the fact that four of the five component measures for that scale require

knowledge of the child's actions since

age twelve (which a step-father may not possess),

whereas the other two scales are related to behaviors around the time of

the survey. Clearly,

within step-families it

is preferable to gather retrospective data of this

sort from the

biological parent.

It bears pointing out that the rate of behavior problems

vary within a very restricted

range across family types. Though the differences between some family types

may be large

proportionally, in absolute terms the differences

are surprisingly modest. For example,

though the ''Behavior Problems I" measure has

a range from seven to twenty-one, the largest

difference in mean scores across family types

was .83, less than a single point.

Family Functioning Measures

In examining the mean distribution of family functioning

measures (Table IV), we

are interested in differences across family types within measures, and differences in the mix

of family functioning resources that each family

type has to draw upon. First, as a general

observation, the two-biological parent family, which reports the fewest

adolescent behavioral

problems. also has the most family strengths to draw

upon and the fewest family

16

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

0

0

dysfunctions to deal with. Parents from such families are much less likely to be depressed,

even after controlling for the gender of the parent. Marital conflict is also much lower for

parents in two-biological parent families than those from step-families. Parents from two-

biological parent families also attend religious services and activities more often, have

more

close relationships with extended kin, and are much more likely to be involved in youth

organizations.

Second, we do observe what may be compensatory patterns of external support

seeking for single parents in general, and for never married female heads in particular. All

three single parent family types show much higher rates of socializing outside of the family,

indicating that they may have a larger support network of friends outside the kinship

system.

In addition. never-married female heads have considerably more adult kin living close by

than parents from other family types; almost one person

more than mothers within two-

biological parent families.

In part this may reflect a cultural

preference, since a

disproportionate number of these women are African-American (see Stack, 1974). It

may

also reflect a deliberate strategy to remain close to kin who

can provide support and

assistance, or may be associated with the lower ages at birth and

more limited resources

associated with out-of-wedlock childbearing.

Beyond these general patterns. there are notable differences (and lack of differences)

across family types in the mean levels of particular family functioning measures.

Though parents from two-biological parent families show the highest

score on the

family friendship measure, the differences between them and the never married

female and single male head families are surprisingly small given that single parents

do not have the spouse's family to draw upon.

17

BEST COPY

AVAILABLE

Involvement with organizations within the community (both religious and youth-

related) is much higher for two-biological parent families than for other family types.

The gap is particularly large between single parent and two-biological parent families

where involvement in youth organizations is concerned, perhaps reflecting the role

overload experienced by single parents. This may be cause for concern, since these

are precisely the types of organizations within the community (religious and youth

organizations) that could be most helpful in supporting single parents and involving

their children in constructive activities.

Across the internal measures of family functioning, there is a notable consistency

across family types in the values for "parent/child time together". This is both

surprising and encouraging, since it indicates that any increased time pressures

experienced by single parents do not seem to translate into less parent/child

involvement in the day-to-day activities covered by this measure. It bears mentioning

that this lack of variation across family types may not exist to the same extent for

very young children, since parents (usually mothers) from two parent families are

more likely to stay at home when there are young children in the house.

Parental depression is extremely high among never married female heads (1.46)

relative to other family types, particularly compared with parents in two-biological

parent families (.61). This gulf remains even when controlling for gender effects:

mothers in two-biological parent families still score very low (.68). The measures for

the remaining family types fall about half way in between these two extremes. There

may be several sources of this variation including selectivity into certain family types,

and differences in income by family type. It seems likely, however, that pressures

associated with parenting for single parent and step-families give rise to depression,

which may in turn have negative impacts on children.

18

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

CORRELATIONS BETWEEN FAMILY FUNCTIONING MEASURES AND ADOLESCENT

BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS

In this section of the analysis we look at the correlations between our ten family

functioning measures and the three outcome measures of adolescent behavior problems. We

look at these bivariate relations for the total sample, and separately for each family type.

These correlations should tell us whether the family functioning measures are behaving

roughly as anticipated in terms of impact and direction, and whether they operate similarly

across family types. Table V shows bivariate correlations for the full sample and separately

by family type. There is a separate page of the table for each of our three outcome

measures.

Results for the Total Sample.

Looking at the first column in each table containing correlations for the full sample,

each of the family functioning measures is significantly related (.05 level) to at least one of

the three behavior problem measures. There was a great deal of variation, however, in terms

of the strength of impact and the number of outcomes to which a measure was significantly

related.

Three of the five "internal" measures of family functioning, (commitment to family,

marital conflict. and parental depression) and one of the external measures (family

friendship) are significantly related to all three outcomes. Four of the measures (parental

involvement in youth organizations, socializing outside of the family, parent-child time

together, and encouraging independence among one's children) are significantly related to

two outcomes. Two of the measures (family within 25 miles, and involvement in religious

19

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

institutions) are significantly related to only one of the outcome measures, and when

significant the correlations were small (.04 and .09 respectively).

For two of the three behavior problem measures, marital conflict and adult

depression (the two negatively defined measures of family functioning), are the most

strongly correlated with the behavior problem measures. Correlations are particularly strong

for marital conflict, running from .28 to .35. For the scale representing more serious

behavior problems, "Behavior Problems II",

the correlations are much smaller both

absolutely (.06 and .08), and relative to other family functioning measures in the model.

One of the measures of family functioning behaved counter to what had been

expected. The bivariate correlations indicate that higher rates of parental socializing outside

family are associated with more adolescent behavior problems for two of the three

outcome measures (Behavior Problems II and parent/child conflict). This would indicate

that an active social life on the part of parents. whatever the benefits gained by him or her,

-may sometimes come at the expense of children. Alternatively, it may be that parents with

troubled children have greater need for social contact and support.

Results by Family Type.

In general, family functioning measures seem to operate rather consistently across

three of the five family types: two-biological parent. divorced/separated female (DSF), and

single male headed families (Table V). Few of the coefficients for single male heads are

significant. but they are similar in size and direction to those of the other two family types

leading one to conclude that the main difficulty here is sample size. Between the two-

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

20

biological parent and the divorced/separated female headed families, only two measures

seem to operate somewhat differently. The parental depression measure is always

significantly correlated with adolescent behavior problems for two-biological parent families.

The correlation is smaller and never significantly correlated for DSF families. In addition,

the family friendship measure is significantly related to one of the behavior problem

measures (Behavior Problems II) for DSF families, but is never significant for two-biological

parent families.

For step-families, several of the measures operate somewhat differently than they do

for other family types. The correlations for "family friendship" are small and insignificant

for all three outcomes in step-families, whereas they are often significant for two-biological

parent and DSF families. Conversely, the "encourage independence" scale, which measures

the importance the parent attaches to encouraging independence in his or her children, is

large and positively correlated with Behavior Problems I and II for step-families, but not

for two-biological parent or DSF families. It may be that this construct takes on a different

content in the case of step-families due to the often problematic relationship between step-

parents and their step-children (Hetherington et. al, 1981).

The family functioning measures performed poorly as predictors of adolescent

behavior problems for never married female headed families. For only one outcome,

"Behavior Problems I", were any correlations significant at the .05 level. Parental depression

and "socializing outside of the family" were both strongly and positively correlated with that

outcome. To some extent this lack of significance undoubtedly results from the small sample

sizes for this family type. But among the remaining correlations their size and direction are

21

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

LTh

j..,)

often at odds with those from other family types, leading to the conclusion that many of

these scales may not be particularly appropriate for families headed by never married

mothers.

The very high correlation between parental depression and adolescent "Behavior

Problems I" for never married female headed families bears particular mention. The

correlation is .43, nearly three times the size of the correlation for two-biological parent

families (the only other family type for which it was significant). Recall that these parents

had much higher depression levels than parents in other family types, which may explain the

higher correlation.

It may be that a much greater proportion of these mothers are

experiencing high levels of depression, and it is this high level of depression which is

associated with behavior problems in their adolescent children. This relation merits further

investigation using longitudinal data so that clear causal inferences can be made.

In sum, we have found that, with a few notable exceptions, family functioning

measures correlate similarly to adolescent behavior problems for three family types: two-

biological parent, divorced/separated female head, and single male headed families.

Measures operated somewhat differently for step-families,

but in ways which are

understandable given the unique stresses within such families. Finally, these family

functioning measures operated poorly for families of never-married mothers, indicating that

efforts should be made to produce alternative measures for such families.

BEST COPY

AVAILABLE

22

FULL SAMPLE MULTIVARIATE ANALYSES RELATING FAMILY FUNCTIONING TO

ADOLESCENT BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS.

Table VI displays the results of a sequence of five models for each of the three

outcomes. The models are nested, and have been designed to allow us to explore the

following questions:

To what extent are the associations between family type and adolescent behavior

problems attributable to differences in other sociodemographic characteristics?

Are there significant effects for individual measures of family functioning once

economic, sociodemographic, and other family functioning measures have been

controlled?

If so. how important are family functioning measures in explaining adolescent

behavior problems relative

to conventional economic and sociodemographic

variables?

What is the relative importance of internal versus external measures of family

functioning with regard to adolescent behavior problems?

To what extent are the effects of other family functioning measures attributable to

the effects of parental depression?

Model One is a simple regression which includes only family structure. Each

coefficient represents a comparison between the family type listed and a two-biological

parent family. As expected, the coefficients are large and positive for all family types. The

coefficients are not significant for never-married female and single male heads for two of

the three outcomes, probably a result of their small sample sizes. In terms of the predictive

power of family structure alone, variance explained is quite modest ranging from 1.6 percent

to 4.2 percent for parent/child conflict and Behavior Problems II, respectively.

In Model Two, we add the remaining economic and sociodemographic variables to

the regressions. These include many characteristics which we would expect to be related

23

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

both to family type and adolescent behaviors, thus potentially reducing the direct impact of

family structure. Such characteristics include family income, public assistance receipt, family

size, parental educational attainment, and race. The introduction of these variables does

increase the predictive power of the model for all three outcomes, but the reduction in the

size of the coefficient for family structure is quite small, being proportionately the largest

for the parent-child conflict outcome. Nor are their reductions for all family types.

Surprisingly, coefficient sizes actually increase for never married female and single male

heads in several cases in the presence of controls. For Behavior Problems I and parent-child

conflict, the inclusion of these control variables reduces the coefficient for single male

headship to marginal significance.

In Model Three, we expand the analysis by introducing all of the internal family

functioning measures except for parental depression. In order to include marital conflict in

this model. it was necessary to combine the marital status and conflict measures, creating

separate high and low conflict versions for two-biological parent and step families. The

omitted family type, that is, the one to which all other family types are compared, is the

two-biological parent low conflict family.

The purpose of this model is to gauge the importance of such measures relative to

the economic and sociodemographic measures included in the previous model. The results

show moderately large increases in the predictive power of Model Three over Model Two

for Behavior Problems I (.067 to .110) and parent/child conflict (.072 to .131), and a more

modest increase for Behavior Problems II (.077 to .091). For two of the three outcomes, the

24

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

predictive power of the model is nearly doubled when these internal family functioning

measures are introduced.

Overall, then, these analyses indicate that the inclusion of family functioning

measures, particularly those assessing internal family processes,

in future surveys may

significantly enhance our understanding of adolescent behavior problems. These models are

based on cross-sectional data and therefore we do not know the causal direction of the

effects running between family functioning and adolescent behavior problem

measures. Of

the three internal measures included in model three, only the "commitment to family"

variable is unlikely to be much affected by adolescent behavior problems. To solve this

problem satisfactorily requires the proper longitudinal data. Such analyses will be feasible

once data from the five year follow-up of the NSFH become available early next year.

Of the four family functioning variables included in model three (parent/child time

together, commitment to family, encouraging independence in one's children, and marital

conflict), three were significant for each outcome. All coefficients

are in the expected

direction. Interestingly, it was a different three in each case.

In Model Four, we add the external measures of family functioning to the model.

These measures add very little to the overall explanatory power of the model and

are

usually not significant. The coefficients for the internal measures were little affected by the

introduction of the external measures. In Table Five we saw that many of these external

measures were significantly correlated with the behavioral outcomes. This leaves open the

possibility that such external factors may be having an indirect effect through their impact

on internal family processes. For example religious involvement may be indirectly affecting

25

BEST COPY

AVAILABLE

parent/child conflict and the behaviors captured in the "Behavior Problems I" measure by

encouraging parent/child time together and an increased commitment to family on the part

of parents. Further research would be needed to clarify the relationship between these

internal and external factors.

In Model Five, we add the parental depression measure to the model. We are

interested in the extent to which the coefficients for other family functioning measures are

reduced by the introduction of this variable. Parent depression shows significant direct

effects on the Behavior Problems I and parent/child conflict outcome measures. The only

independent variables in the model affected by the introduction of this variable are the

family type/conflict measures. The coefficients for these variables are reduced across the

board. though the reduction is never more than 20 percent. Comparing the variance

explained between Model Five and Model Two (the economic and sociodemographic

model) we find a doubling of the R-square for the Behavior Problems I and parent-child

conflict outcomes. and a more modest increase of about 25 percent for Behavior Problems

II. Clearly, family functioning measures are. as a group, important for our understanding

of adolescent behavior problems.

Looking at the impact of individual measures in Model Five, we see that all of the

internal family functioning measures, including parental depression, showed significant

impacts for at least two of the three adolescent outcome measures: marital conflict was

significant for all three. Among the external measures, parental involvement in youth

organizations has a sizeable direct relation to the Behavior Problems I scale, and religious

involvement has a modest but significant relation to the Behavior Problems II scale. There

26 BEST COPY

AA/fix/as

were no other significant direct impacts of external measures. For the total sample, then,

internal measures of family functioning are more closely and systematically related to

adolescent behavior than external measures, at least in terms of their direct effects.

Of the three outcomes, family functioning measures appear to have the smallest impact on

the scale measuring serious behavioral problems. This is interesting since it implies that,

when it comes to the more serious "acting out" kinds of behaviors that most impact the

community, family functioning is a relatively less important factor than it is for the day-to-

day behavioral problems captured in the other two measures.

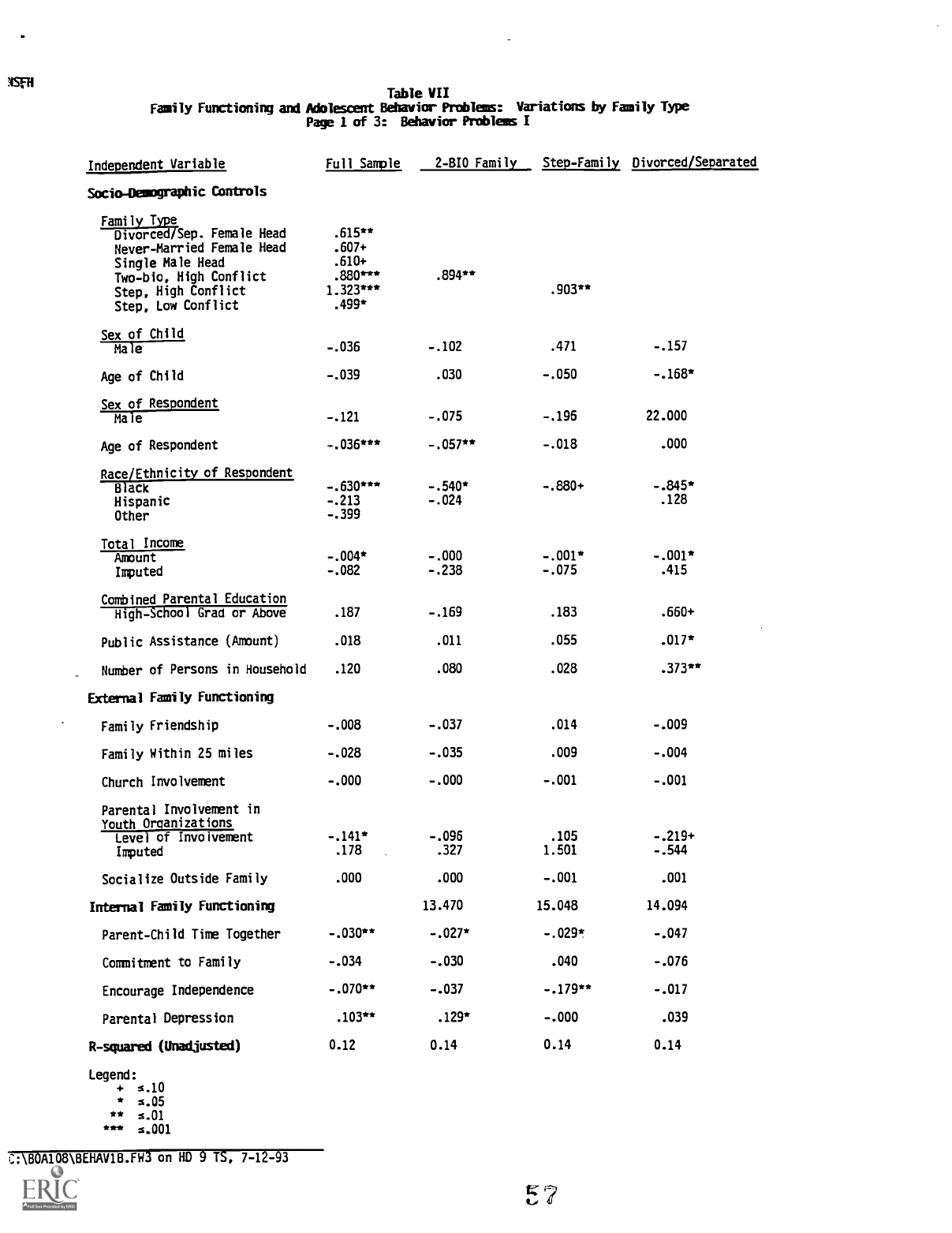

MULTIVARIATE MODELS RELATING FAMILY FUNCTIONING TO ADOLESCENT

BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS: VARIATIONS BY FAMILY TYPE.

For our final analyses we have run the full model from the previous table (minus the

family type indicators) separately by family type. These runs were performed for three

-

family types: two-biological parent. step-parent. and separated/divorced female headed

families. Small sample sizes for single male and never married female headed families

precluded us from estimating multivariate models for these groups. For the sake of

consistency with the full sample model, the marital conflict variable remains in the "family

type' section of the table. Again, separate analyses were performed for each of the family

types.

In analyzing the correlations in Table Five, we noted the different patterns of

relationships between family functioning and adolescent outcome measures which exist for

different family types. In this table we explore the same issues in a multivariate context. This

27

4.

(-)

.7)

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

will allow us to evaluate differences controlling for economic and sociodemographic

measures, and for other measures of family functioning.

Across the three outcomes, several distinct patterns of relationships appear by family

type. First, parental depression is a strong predictor of adolescent behavior problems for

two-biological parent families, but is small and insignificant for the other family types. It is

unclear why this should be so. It may be that the causes of adolescent behavior problems

differ across family types. Alternatively, and thinking in the other direction causally, it may

be that adolescent misbehavior is a relatively more important determinant of depression

among parents in two-biological parent families, since parents in other family types may face

additional many additional life stresses which affect their emotional health.

Second, encouraging independence in one's children is a significant predictor of

problems in several of the models for step-families (Behavior Problems I and II) and

families headed by divorced or separated mothers (Behavior Problems II), but has no

measurable impact among two-biological parent families. The effects seem particularly

strong for step-families. It is reasonable to posit an increased need on the part of step and

single parents for independence among their children. Single parents, lacking a spouse to

share the load, are under increased time pressures, and may have a greater need for their

children to be independent in their day-to-day activities. Parents in step-families may require

more time to build the spousal relationship than two- biological parent parents. In addition,

the special tensions which often exist between step-parents and their children, which can

themselves lead to behavioral difficulties, may be minimized if the adolescent can achieve

a degree of independence from parents. These unique needs may translate into differences

28

3D

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

in the meaning of the measure itself across family types, since parents in different family

types may have different notions of what constitutes "independence" given their distinct

needs in this area.

Third, parental conflict is a significant predictor of all three behavior outcomes for

both two-biological parent and step-families. For Behavior Problems II and parent/child

conflict, the effect is very large. This large impact of parental conflict indicates that high

conflict married households may be equally or more detrimental for children than single

parent households, a point which has been made in the literature for some time (Zill, 1983).

What is lacking from the present and previous analyses, and what is clearly needed, is

some

measure of adult domestic conflict within single parent households. It is likely that many

single parents have regular interactions with boyfriends and girlfriends, partners, and

extended kin who live in the household or are regular visitors. To do truly adequate

comparisons across these family types, such a measure, which is critical to understanding

the dynamics of married couple families, should be developed for single parent families

as

well.

Fourth, for the one outcome (Behavior Problems I) in which parental involvement

in youth organizations was a significant predictor for the total sample, significance is lost

for all but divorced/separated female headed households. Here the size of the effect is

substantial, though the significance is marginal at .10. It is difficult to say whether this is in

fact a true difference by family type, or is instead a matter of gender. It

may be that it is

the involvement of mothers in such organizations that is the critical factor; the gender

specific correlations in Table Five appear to bear this out. Regardless, it suggests that when

29

'17)

01-.0

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

single mothers are involved in community organizations, their children have fewer behavior

problems.

CONCLUSIONS

In this analysis we have explored a number of important issues related to family

functioning measures in general and, in particular, to the ways in which they operate across

distinct family types. The major findings of the paper are as follows:

There is a great deal of consistency in the reliability of the composite scales of family

functioning across family types.

Nevertheless, there is also significant variation across family types in the ways in

which these measures relate to adolescent behavior problems. :=Available measures

seemed to operate particularly poorly for never married female heads of household.

There are significant differences across family types in terms of access to positive

family strengths, and differences in levels of family dysfunction as well (particularly

depression), with two-biological parent families generally higher on the measures of

family strengths. Nevertheless, there was some evidence that single parent families

attempt to compensate by reaching out to extended kin and to friends and neighbors.

It is unclear whether such compensating strategies in fact operate to reduce the

behavior problems of their adolescent children, however, since the measures were

not positively related to reduced behavior problems for adolescents from such

families in the multivariate analyses.

With the few important exceptions noted above, the effects of external measures of

family functioning are indirect at best, through their impact on internal family

processes. Internal measures appear to be the most important, at least in terms of

direct impacts on adolescent behaviors.

The more negatively defined measures of family functioning (marital conflict,

depression) were very powerful predictors of adolescent behavior problems in two-

biological parent families both in themselves and relative to the impact of more

positively constructed measures. Marital conflict was a powerful predictor for step-

families as well.

30

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

Family functioning measures showed themselves to be about equal in predictive

power to sociodemographic measures in predicting two of the three behavior

problem measures. Clearly measures of this sort merit serious consideration for

inclusion in future federal surveys.

Which parent one interviews in a survey appears to be important for specific

measures in the analysis. There were clear differences in the level of reporting by

gender. In addition, some measures, such as that for involvement in youth

organizations, perform differently by gender in both correlational and multivariate

analyses. Among step-families, there appears to be less knowledge of a child's

behavioral history among step-parents.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the findings presented

in this

paper, we have the

following

recommendations:

The measures of family functioning constructed here indicate that such measures,

particularly those we have termed "internal" measures, predict to adolescent behavior

problems and thus merit inclusion in future large scale sample surveys. We

recommend that work be done to further develop these types of measures for use in

future large scale surveys.

New work should be done to develop measures for never-married female headed

households. Many of the measures explored here did not work as well for this group

as they did for other family types. This is of some importance to the Federal

government, particularly in light of plans to reorganize the welfare system. Such

plans can benefit from a knowledge of what constitutes strong never married female

headed families.

A new measure of domestic conflict should be developed for single parent

households. Conflict is a very important predictor of child well-being in married

couple households, and we hypothesize that conflict with partners and/or resident

adult kin may be similarly important for single parent families as well where

significant conflict exists.

When possible, surveys should interview both parents, and the child as well.

Differences in reporting by both gender and biological/nonbiological status of the

parent which were found in this analysis indicate that this would provide valuable

additional information. In addition, as was demonstrated in the analysis of the

31

4.0,

-7)

kir

,

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

National Survey of Children also conducted for this project, child reports are often

superior for topics such as adolescent behavior problems, child activities and the

parent/child relationship.

Further work should be done using longitudinal data for this sort of analyses (for

existing efforts see accompanying papers). Such work can be done using the NSFH

once data from the second wave of interviews becomes available in early 1994.

Analyses similar to these should be performed for younger age groups. It is very

likely that what constitutes a family strength differs according to the child's age and

stage of development.

32

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

REFERENCES

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979)

The ecology of human development.

Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Buchanan, Christy M., Maccoby, Eleanor E., and Dornbusch 1991. Caught Between Parents:

Adolescents' Experience in Divorced Homes. Child Development 62: 1008-1029.

Dunst, Carl J. and Carol M. Trivette 1992. Measuring Family Functioning as an Outcome

of Social Action Programs: A Framework and Relevant Indicators. A position paper

on family functioning outcomes prepared for the PEW Charitable Trusts, as part of

the Comprehensive Children's Services Initiative.

Furstenberg, F. F., Jr., Nord, C. W., Peterson, J. L., & Zill, N. (1983). The life course of

children of divorce: martial disruption and parental contact. American Sociological

Review, 48(10): 656-668

Hetherington, E.M., Cox, M. and Cox, R. Divorce and remarriage. Paper presented at the

meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Boston, April 1981.

Krysan, M., Moore, K. A., & Zill N. (1990, May).

Identifying successful families: An

overview of constructs and selected measures. Paper presented at conference of the

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services, Washington, DC.

Nunnaly, Jum C. 1978. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Olson. D. H., Russell, C. S., & Sprenkle. D. H. (eds.) (1989). Circumplex model: Systemic

assessment and treatment of families. New York: Haworth Press.

Stack. C. (1974).

All our kin:

Strategies for survival in a black community. New York:

Harper and Row.

Stinnett, N., De Frain, J. (1985). Secrets of strong families. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

Swihart. J. (1988). "Characteristics of strong families." Unpublished

paper, International

Family Center, Logos Research Institute.

Zill, N. (1983, 22 and 24 March). Divorce. marital conflict, and children's mental health:

Research findings and policy recommendations. Testimony before Broken Families:

Hearings before the Subcommittee on Family and Human Services. Senate Hearing,

98-105.

33

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

Zill. N. (1991). The behavior problems index:

Descriptive material.

Washington, DC:

Child Trends.

Zill, N., Morrison, D. R.. & Coiro, M. J. (in press). Long -term effects of parental divorce

on parent-child relationships, adjustment, and achievement in young adulthood.

Journal of Family Psychology, special issue on Families in Transition.

Zill, N., & Rhoads. A. (1991). Assessing family strengths in a national sample of families

with adolescent children. Washington, DC: Child Trends

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

34

APPENDIX A

DEFINITIONS OF FAMILY FUNCTIONING AND ADOLESCENT BEHAVIOR

PROBLEM MEASURES USED IN THE NSFH ANALYSES

ADOLESCENT BEHAVIOR PROBLEM MEASURES

1. Adolescent Behavior Problems I

A seven-item additive scale of responses to the following questions (with each

item on a scale of 1-3 ranging from "often true" to "not true"):

Child often:

1. is irritable or sad (reverse coded)

2. loses temper (reverse coded)

3. is cheerful

4. is fearful (reverse coded)

5. bullies other children (reverse coded)

6. does what you ask

7. gets along with other kids

2. Adolescent Behavior Problems II

A five-item scale with range of 0-5, with one point for an answer of "yes" to each

of the following questions:

1.

child ever suspended/expelled from school since age 12?

2.

child ever run away since age 12?

3. child ever in trouble with police since age 12?

4. child ever see a doctor for emotional problems since age 12?

5. met with teacher/principal concerning behavior problems of child in

last year?

3 Parent/child conflict.

A seven-item scale, with a range of 0-7, which reflects the degree of conflict

between parent and adolescent child in the following areas: dress, friends, staying

out late, helping around the house, money. school, and getting along with other

family members.

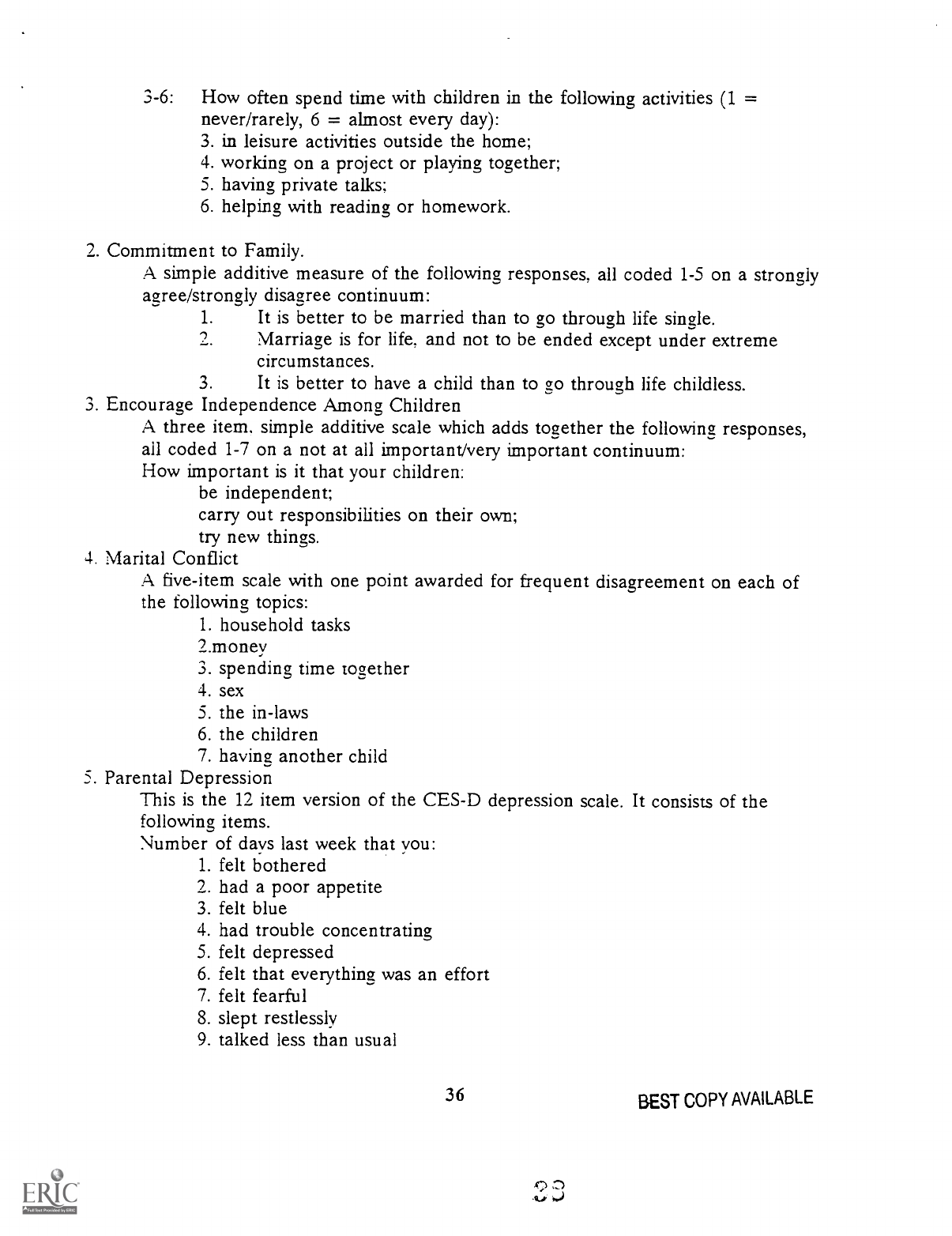

IN 1 ERNAL FAMILY FUNCTIONING MEASURES

1. Parent-Child Time Together

This is a simple additive scale of the following measures:

1. number of times last week ate breakfast with child.

2. number of times last week ate dinner with child.

35

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

3-6:

How often spend time with children in the following activities (1 =

never/rarely, 6 = almost every day):

3. in leisure activities outside the home;

4. working on a project or playing together;

5. having private talks;

6. helping with reading or homework.

2. Commitment to Family.

A simple additive measure of the following responses, all coded 1-5 on a strongly

agree/strongly disagree continuum:

1.

It is better to be married than to go through life single.

Marriage is for life, and not to be ended except under extreme

circumstances.

3.

It is better to have a child than to go through life childless.

3. Encourage Independence Among Children

A three item, simple additive scale which adds together the following responses,

all coded 1-7 on a not at all important/very important continuum:

How important is it that your children:

be independent;

carry out responsibilities on their own;

try new things.

4. Marital Conflict

A five-item scale with one point awarded for frequent disagreement on each of

the following topics:

1. household tasks

2.money

3. spending time together

4. sex

5. the in-laws

6. the children

7. having another child

5. Parental Depression

This is the 12 item version of the CES-D depression scale. It consists of the

following items.

Number of days last week that you:

1. felt bothered

2. had a poor appetite

3. felt blue

4. had trouble concentrating

5. felt depressed

6. felt that everything was an effort

7. felt fearful

8. slept restlessly

9. talked less than usual

36

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

10. felt lonely

11. felt sad

12. couldn't get along.

One point was given for each time the answer was four days or more.

EXTERNAL FAMILY FUNCTIONING MEASURES

1. Extended Family Friendship

An additive scale with one point for each adult extended family with whom

one is

very close emotionally. This includes parents. siblings, spouses of siblings, of both

the respondent and spouse.

2. Extended Family living within 25 miles

Number of adult extended family members living within 25 miles of respondent.

This includes parents, siblings, spouses of siblings, of both the respondent and

spouse.

3. Parental Church Involvement

Number of days per year that adult respondent attends services

or a social

function at a religious institution.

4. Parental Involvement in Youth Organizations

A four item measure reflecting regular involvement of respondent

or spouse in

the following types of organizations:

PTA or school activity;

Religious youth group;

Community youth group;

team sports/athletic clubs.

One point is given for involvement in each type of organization.

5.

Socialize Outside Family

Number of days per year that adult respondent socializes in the evening with

friends, neighbors, or co-workers.

37

BEST COPY AVAILABLE

MSFII

table

Principal Components Factor Analyses for Indices Used in the Analysis

Index

Number of

Component

Items

Potential

Range

Number of

Factors

Extracted

(Eigen-

value 1.00

or higher)

Number of

Components

Loading

.30 or More

on First

Factor

Number of

Components

w/ Highest

Loading

on First

Factor

Adolescent Outcome Measures

Behavior Problems I 7 7-21 2 7

5

Behavior Problems II 5

0-5

1 5

5

Parent-Child Conflict 7 0-7

1 7

7

Family Functioning Measures

External

Family Friendship

9

0-open 4

8

4

Family Within 25 miles*

8 0-open

Church Involvement

2

0-365

1

2

2

Parental Involvement in

Youth Organizations

4 0-4 1

4

4

Socialize Outside Family 3

0-312

1

3

3

Internal

Parent-Child Time Together

6

4-38 1

6

6

Cannitment to Family

3

0-15

1

3

3

Encourage Independence

3

0-21 1

3

3

Marital Conflict

5

0-5

1

5

5

Parental Depression

12

0-12 1

12

12

* Treated as a sumnary index, not a scale.

C:\BOA10B\FACTOR1.14V on HD 9 TS, 6-23-93

4 3

REST COPY AVAILABLE

NSFH

Table II

Measurement Reliability by Family Type: Cronbach's Alpha (Unstandardized)

Index

All

Family

Types

Major Family Type

Sex and Biological/Step Status

of Married Adult Respondent

Divorced/

Separated

Female

Head

Never-

Married

Female

Head

Single

Male

Head

Married,

Both Bio

Parents

Married,

Bio+Step

Parents

Married,

Married,

Married,

Married, Bio+Step

Bio+Step

Both Bio

Both Bio Bio-

Step-

Male R

Female R

Female R

Male R

Adolescent Outcome Measures

Behavior Problems 1

.66 .70

.67

.66

.61

.64

.57

.63

.58

.73

Behavior Problems II

.62

.63 .58

.65

.48

.64

.44

.50

.66

.68

Parent-Child Conflict

.72

.74

.74

.73

.69

.72 .73

.66 .69 .75

Family Functioning Measures

External

Family Friendship

.60

.52

.48 .56

.66 .51

.67

.64

.34

.69

Family Within 25 miles*

Church Involvement

.62 .66

.66

.48

.56

.68

.60

.54

.67

.72

Parental Involvement in

Youth Organizations .63

.68 .57 .60

.61

.62 .61

.61

.56

.67

Socialize Outside Family .44 .34

.32 .38

.51

.42 .57 .46 .34

.61

Internal

Parent-Child Time Together

.72

.73

.69

.72

.71 .77

.66

.71 .69

.80

Commitment to Family

.54 .47

.42

.44

.54

.54

.54

.51

.56

.49

Encourage Independence

.61 .60

.69

.70

.60

.60 .63

.57

.58

.67

Marital Conflict

.71

.70

.14 .66

.72 .77

.71

Parental Depression

.89

.89

.87 .89 .88 .87

.90

.87 .87

.82

Sample Size Range

Minimum

1,100

394

56 82 704

289